Abstract

Veterans in the UK seek help from numerous, diverse organisations to navigate the housing system, in contrast to countries such as the US and Australia, which operate dedicated Veterans Administrations. Collaboration between organisations to support veterans is non-mandatory, yet influential on housing outcomes. This study utilised network governance theory to examine how local partnerships affect veterans’ housing pathways. The research approach involved five in-depth, area-based case studies across different housing contexts. The research contributes new findings on the positive impact of local partnerships and develops a conceptual model of veterans’ housing pathways, focused on collaboration. The study revealed a step change in partnership-working since the introduction of the UK Armed Forces Covenant in 2011, with the absence of mandatory collaboration requirements having nurtured trust-based network governance. The findings suggest this has been effective for veterans in housing need, but there are potential risks in terms of sustainability of voluntary partnerships and the temptation for central government of more hierarchical approaches.

Introduction

Homelessness amongst military veteransFootnote1 has been a subject of considerable political attention and policy development over the past decade in a number of countries, particularly those involved in long-standing operations in Afghanistan and Iraq (Cobseo, Citation2020; Cusack et al., Citation2020; Hilferty et al., Citation2021). In the UK, since the publication of the Armed Forces Covenant (MOD, Citation2011a), a range of legislative and regulatory changes have been made by the UK Government and devolved administrationsFootnote2 in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. These have aimed to ensure that those who have served in the Armed Forces are not disadvantaged as a result, including a focus on housing, since some veterans face particular challenges in dealing with the complexities of the civilian housing system, having lived in Armed Forces accommodation whilst serving. Perhaps more than in any other area, collaboration has been seen as central to resolving such housing issues, aiming to bring organisations together to enable veterans to access and sustain appropriate housing. Hence there has been substantial encouragement to develop partnership working at a local level, to meet the needs of veterans and their families (MOD, Citation2011b, Citation2017; UK Government, Citation2018).

This emphasis on collaboration is unsurprising within the broader context of the shift from government to governance (Kooiman, Citation2003; Rhodes, Citation1997; Stoker, Citation2018), and the retrenchment of public services over a decade of austerity policies (Hastings et al., Citation2017; Lowndes & Gardner, Citation2016). However, since collaboration has not been mandated by central government in this context, there are questions regarding the extent, form and impact of local partnership working. In the absence of regulatory requirements, empirical investigation is needed to understand how such partnerships may operate and the implications of voluntary collaboration for the veterans they are intended to support. This paper reports the findings of research into veterans’ housing outcomes across England, Scotland and Wales, exploring the role of inter-organisational collaboration in delivering those outcomes. We examine the role of networks in local partnerships, highlighting the implications for governance theory and for practice relating to veterans’ housing pathways.

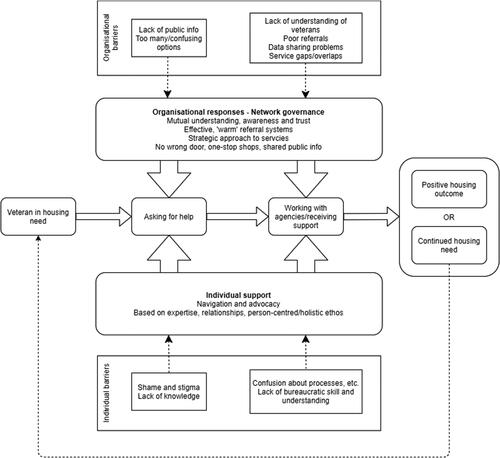

In contrast to the US, where the Veterans Administration provides dedicated services, how organisations work together is central to the ability of UK veterans to navigate the housing system. Hence, we develop a conceptual model focused on collaboration, to complement the ‘Journey to Home’ for veteran’s housing pathways in the US (Cusack et al., Citation2020). Notably, beyond the literature regarding the US Veterans Administration (cf. for example: Mares & Rosenheck, Citation2004; Metraux et al., Citation2017; Tsai & Rosenheck, Citation2015) and some emerging evidence from Australia (Hilferty et al., Citation2021; Wood et al., Citation2022), there is very little international research regarding veterans’ homelessness and housing issues. We argue, therefore, that our study provides a valuable contribution to the international literature, going some way to address the gap in empirical research. Moreover, we suggest that our model is likely to be applicable across a range of national contexts, particularly in those countries where veterans’ needs are met through mainstreamFootnote3 public services and/or voluntary sector organisations, rather than a separate veterans administration.

Veterans’ housing – the changing landscape

The transition from a top-down, command and control style of government to a more collaborative, multi-sector form of governance has been well documented (Kooiman, Citation2003; Newman et al., Citation2004; Pollitt & Hupe, Citation2011). Although the high water mark of partnership-focused policy was arguably passed during the New Labour years (1997-2010), there is a strong argument that partnership has become the norm in public services (Dickinson & Glasby, Citation2010; Hunter & Perkins, Citation2014; Muir & Mullins, Citation2015), reinforced over the past decade by the impacts on local government budgets of austerity policies (Hastings et al., Citation2017) underpinned by a broader neoliberal agenda (Peck, Citation2012). Within the UK housing system, changes such as the fragmentation and diversification of social housing in recent decades (Hickman & Robinson, Citation2006) have reinforced the need for collaborationFootnote4.

In relation to veterans, the organisational picture is especially complex, due to the large number of Armed Forces charities. Although the sector has shrunk slightly in recent years, there remain nearly 2000 Armed Forces charities in the UK, with a considerable degree of organisational turnover in some sectors (Doherty et al., Citation2019). Around 80 of these provide housing-related services, ranging from accommodation provision to homelessness services, advice and support (Doherty et al., Citation2018). Hence, whilst veterans facing housing difficulties may have significant support available, the plethora of organisations can add to their confusion in attempting to understand the civilian housing system. Unsurprisingly, therefore, there have been repeated calls for improved collaboration to ensure that veterans do not fall through the cracks (Ashcroft, Citation2014; Forces in Mind Trust, Citation2013; Robinson, Citation2016), which have been answered by changes in policy and practice at national and local levels.

To understand the development of collaboration and assess impacts on veterans’ housing outcomes, this section provides three elements of context – an explanation of the distinctive housing challenges faced by (some) veterans, an overview of the policy changes made in the past decade, and some key elements of theory regarding collaboration which we use to frame our analysis.

Veterans’ housing challenges

Despite the common perception in the UK that veterans are disproportionately likely to be homeless, repeatedly reinforced by newspaper campaigns (Lebedev, Citation2015; Willetts, Citation2019), research suggests this is not the case (Bevan et al., Citation2018; Quilgars et al., Citation2018). Although there is some evidence of higher levels of veterans’ homelessness in earlier decades, this is no longer true and the proportion of veterans amongst the homeless population may be falling further, making up just 2-3% of the homeless population (CHAIN, Citation2019). A similar trend of reducing veterans’ homelessness exists in the US (Cusack et al., Citation2020), but it should be noted the causes for these changes are difficult to interpret. In the UK, data on homeless veterans remains incomplete for a variety of reasons (Wilding, Citation2020), and trend data needs to be understood within the context of a changing veterans’ population as the Armed Forces reduce in size and older, larger cohorts die off. However, there is also evidence that veterans are more likely to experience complex difficulties than other homeless individuals (Johnsen & Fitzpatrick, Citation2012; Johnsen et al., Citation2008), reflecting a similar picture in Australia (Wood et al., Citation2022). Moreover, the data suggests that there may be issues regarding transition from the military, since around 5% of Service leavers report experiencing homelessness within the first two years (National Audit Office, Citation2007).

Aside from the ubiquitous factors which underpin homelessness, such as unemployment, relationship breakdowns and broader structural issues around cost and supply, veterans face some distinctive housing challenges, especially around transition. Unlike most jobs, a career in the military often involves living in tied accommodation, meaning Service leavers need to find a new home alongside a new job, as well as managing the cultural and psychological challenges of transition to civilian life. Those who entered the Forces at a young age may lack experience of the civilian housing system, a problem exacerbated by the extent to which Armed Forces accommodation is subsidised and managed for serving personnel (Forces in Mind Trust, Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2014). Whilst the proportion of home-owners amongst serving personnel has increased in recent years (MOD, Citation2020), requirements for mobility and overseas deployments still make it difficult to buy a house or even decide where to settle.

Some veterans are more likely than others to experience housing difficulties. In particular, there is strong evidence that Early Service Leavers, who have served less than four years and therefore receive restricted resettlement support, tend to have poorer outcomes in a number of areas including housing (Ashcroft, Citation2014; Godier et al., Citation2018; Quilgars et al., Citation2018). Similarly, those who experience an unplanned end to their career due to medical or compulsory discharge are more likely to have problems (Clifford, Citation2017; Metraux et al., Citation2017). Other vulnerabilities such as disability, mental health or substance misuse can also play a significant role, although the extent to which such issues arise from service, or experiences before or after service is debated (Johnsen et al., Citation2008; Mares & Rosenheck, Citation2004; Tsai & Rosenheck, Citation2015).

Homelessness and veterans policy

In response to these challenges, the UK Government and the devolved administrationsFootnote5 have introduced a range of policy changes in the past decade, aiming to deliver the Covenant pledge that veterans should not be disadvantaged as a result of their service. Although there are minor differences between the devolved administrations, the overall direction of travel and many of the specific policies are common across the UK. These changes have focused on recognising the potential vulnerability of veterans, giving them a degree of greater priority within the homelessness system and requiring local authorities to collaborate with Service establishments and Armed Forces charities in their area, to coordinate support and information. Similar changes have also been made to social housing legislation and guidance, to give veterans increased opportunities to obtain social housing tenancies.

The overall picture, therefore, is one of incremental change across the UK, focused on addressing the housing challenges experienced by Service leavers and other veterans, including requirements for local authorities to drive collaboration with relevant organisations. This latter point reflects a wider move across UK policy towards partnership working as a core part of effective prevention and resolution of homelessness (DLUHC, Citation2021; Scottish Goverment, Citation2020; Welsh Government, Citation2019).

These changes need to be understood in relation to policy relating to veterans since the publication of the Armed Forces Covenant in 2011. Crucially, there has been an evolving emphasis on developing local partnerships, usually with local authority leadership, bringing together public sector organisations, Armed Forces charities and mainstream voluntary sector organisations such as Housing Associations. Whilst such partnerships have never been legally mandated, they have effectively become standard across the UK, with a model of the necessary ‘core infrastructure’ emerging from reviews of local practice (Forces in Mind Trust, Citation2017) which has since been incorporated into guidance (MOD, Citation2017). This includes an expectation that local authorities will appoint an elected member ‘Armed Forces Champion’, establish a Covenant Forum to bring organisations together, improve communication with veterans and develop an action plan to address issues facing veterans locally.

Collaboration theory

Our focus in this research was on the impacts of collaboration, in terms of veterans’ housing outcomes. This, however, raises two inter-related areas of complexity. Firstly, since partnerships involve multiple organisations working together over time (Sullivan & Skelcher, Citation2002), they are inherently complex, producing emergent structures and patterns of behaviour which cannot be easily predicted or causally understood (Glouberman & Zimmerman, Citation2002). This is reflected in the plethora of theoretical perspectives developed across disciplines which attempt to capture and analyse the key elements of collaboration (Huxham, Citation2003). Secondly, this complexity is further exaggerated in attributing outcomes to partnership, since the causal links are always ambiguous (Dickinson & Glasby, Citation2010).

To manage these complexities, we draw on Powell and Exworthy’s (Citation2001) notion of three ‘resource streams’ necessary for successful partnerships – policy, process and resource. Thus, research on partnerships needs to examine the clarity of policy goals, the mechanisms introduced and the resources available to achieve them. This chimes with most models of successful partnerships, emphasising the development of a shared purpose or vision, the role of processes, structures and communication, and the necessity for appropriate resources, including intangible elements such as trust (Hardy et al., Citation2003; Hunter & Perkins, Citation2014; Wildridge et al., Citation2004). In the context of our study, this leads us to focus on the extent to which the Covenant principle of ‘no disadvantage’ translates into a shared goal at a local level, the ways in which local collaboration and consequent changes to services have been delivered, and the roles of different types of resource.

In addition to examining the resource streams within local partnerships, we also consider their governance, since the non-mandatory nature of Covenant-related collaboration provides an unusual case study. Local Armed Forces Covenant partnerships need to be understood in the context of the wider, long-term shift from government to governance, driven by a neoliberal agenda to roll back the state and underpinned by new public management approaches based on private sector models (Diefenbach, Citation2009; Feigenbaum et al., Citation1999; Hood, Citation1991; Peck, Citation2012). However, these veteran-focused partnerships are unusual in two important ways. Firstly, unlike many areas of partnership built on central government funding (e.g. New Deal for Communities, City Deals), or required by legislation (e.g. Health and Social Care Integration in Scotland, Community Safety Partnerships), Covenant Forums and related elements of collaboration are unfunded recommendations. Secondly, whereas most 21st century partnerships can be viewed at least in part as an attempt to draw in private and voluntary sector resources to fill gaps left by the shrinking state, Covenant partnerships arguably form a new area of state activity. Historically, much of the support for veterans in the UK has been provided by the large Armed Forces charity sector (Pozo & Walker, Citation2014), whilst the public sector largely treated veterans as an undifferentiated part of the wider population. Hence the development of local partnerships led by local government since 2011 represents a new focus for the public sector, which has also drawn in significant parts of the mainstream voluntary sector.

The implications of this basis for local partnership can be usefully examined through the lens of ‘modes of governance’. Lowndes and Skelcher (Citation1998), amongst others, propose three main modes of governance: market governance, where collaboration operates through contractual relationships; hierarchical governance, where collaboration is delivered through an integrated, authority-based structure with bureaucratic routines; and network governance, where collaboration is based upon trust, reciprocity and voluntary cooperation. Arguably, the absence of substantial dedicated funding or legislative mandate suggests that collaboration in this area should lean heavily towards the last of these. Studying how local partnerships operate should provide a valuable insight into whether and how network governance can operate in practice, as well as its impacts and limitations. Although network governance may suggest mutually beneficial partnerships of equals, there are significant critiques regarding the implications for democratic accountability (Swyngedouw, Citation2005), as well as concerns that the limitations of trust-based relationships and the pressures of austerity tend to drive such partnerships towards hierarchy and coercion (Davies, Citation2012; Penny, Citation2017). Our study therefore aimed to examine the extent to which network governance arrangements related to veterans might be changing over time, or concealing a less collaborative approach.

Importantly, our analysis does not end with understanding local partnership processes, since we also aim to examine the extent to which developments in collaborative practice feed through into outcomes for veterans. The housing issues faced by some veterans, outlined above, often relate to difficulties with negotiating the bureaucracy and organisational boundaries of the housing system. Although a qualitative study such as this can provide only limited evidence regarding the ultimate outcomes in terms of veterans’ housing situations, it is important to explore the impacts of partnership on the more immediate outcomes relating to veterans’ experiences of services, as regards accessibility, equity and efficiency (Dowling et al., Citation2004).

Drawing these elements together, our study aimed to address three research questions:

How has the policy focus over the past decade translated into collaboration at a local level?

How have changes in collaboration affected housing outcomes and experiences of services for veterans?

What does the experience of collaboration in this field tell us about the practical application of partnership and governance theory?

Methodology

Area-based case studies

To examine collaboration and impacts for veterans in different contexts, we undertook five in-depth, area-based case studies. This approach was designed to facilitate detailed understanding of the processes, structures and relationships that shaped collaboration, triangulating across different organisations and individuals to ensure a robust analysis. Areas were selected to include England, Scotland and Wales, with different levels of local military presence across the three Services, and diverse housing markets in terms of cost and supply of social and private rented properties ().

Table 1. Case study areas.

Within each area, semi-structured interviews were conducted with key staff from local authorities, housing organisations, Armed Forces charities and other third sector bodies involved in meeting veterans’ housing needs (). These interviews focused on each organisation’s experience of veterans’ housing need, typical housing pathways, and aspects of collaboration.

Table 2. Organisational interviewees by type of organization.

Alongside the organisational interviews, a sample of veterans was interviewed in each area. Participants were identified through organisations and snowball sampling, focusing on individuals willing to share their experience of housing issues who had left the Forces within the last 10 years (). Although not perfectly representative the sample broadly reflects the population of Service leavers encountering housing problems, with a predominance of Other Ranks (i.e. non-Officer) Army veterans who joined at a relatively young age. The interviews focused on housing journeys since transition and pre-discharge preparation.

Table 3. Characteristics of veteran interviewees.

Data analysis

Data from the organisational interviews was analysed in Nvivo, employing a pragmatic, three stage coding process. Each transcript was first coded using descriptive characteristics of the interviewee and case study area, then a provisional framework based on a priori codes relating to housing pathways and approaches to collaboration, and finally a more detailed evaluative coding to identify barriers, facilitators and links to outcomes (Miles et al., Citation2018). The veteran interviews were then coded using the same framework, with a focus on triangulation to test the picture of local collaboration presented by the organisations (Thurmond, Citation2001).

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University of Stirling’s General University Ethics Panel (Ref GUEP640). To maintain confidentiality, case study areas and participants are not named in this paper and only basic personal characteristics are provided to contextualise direct quotes.

Limitations

There are two main methodological limitations. Firstly, there are potential issues with selection bias, since the requirement for local authority involvement may have excluded areas with poor records of collaboration. However, this is somewhat balanced by the opposite bias in veteran participants, who largely self-selected on the basis of difficult housing journeys. Secondly, the relatively recent introduction of veteran homelessness reporting requirements means that it was not possible to further triangulate the findings by examining housing outcome data over the past decade. Future studies could usefully address this latter point.

Findings

We set out our findings in two sections. Firstly, we look at the changes in collaborative practice within the case study areas. And secondly, we explore the impacts of these changes, focusing primarily on the interim outcomes of veterans’ experiences within the civilian homelessness and housing system, since our qualitative data cannot provide a robust assessment of impacts on concrete housing outcomes. Although the case study areas were selected deliberately to provide contextual diversity, the approaches to partnership were remarkably similar, with only relatively minor differences related to issues such as local housing markets. Hence, we have focused our analysis on the commonalities to highlight the effects of the general shift towards collaboration and avoid an excessively detailed discussion of local issues.

Changes in collaborative practice

Whilst collaboration related to Armed Forces Community issues has a longer history, particularly in areas with a large military presence, the case study areas suggest there has been a step change since the publication of the Covenant and subsequent guidance. This section explores these changes to examine their internal effectiveness, before moving on to their impact on veterans’ housing outcomes in the subsequent section.

Every local authority had taken significant steps towards building the ‘core infrastructure’ to deliver the Covenant (Forces in Mind Trust, Citation2017; MOD, Citation2017), including the appointment of an Armed Forces Champion and lead officer, as well as establishing a Covenant Forum to bring organisations together. This combination of leadership and partnership structures had generated a range of collaborative initiatives addressing the needs of veterans in each area, including dedicated posts, one-stop shops, housing pathway protocols and the development of dedicated housing provision (summarised in ).

Table 4. Collaboration structures and initiatives.

Whilst the specific initiatives and collaborative structures vary, reflecting differences between the areas, the overall picture shows significant commonality in key developments and direction of travel. Data from interviewees suggests that this increase in collaborative activity has been underpinned by two factors.

Firstly, multiple participants from each case study area highlighted a clear sense of a shared goal, focused on meeting the needs of veterans. Often this was emphasised during partnership meetings to reinforce collaboration:

The first thing I always do… when I’m trying to work in partnership, is just anchor everything in everyone’s values and principles cause ultimately we all want the same outcome, especially in veterans delivery, and then from that place do the work together. (Staff member, Armed Forces charity)

It’s a group that works really well together, surprisingly so because, you know, my background is homelessness and substance misuse services so having worked across a range of these partnerships I would say the armed forces one is the most effective, and everyone’s very respectful, no one has any agenda other than trying to help the client group and there’s nothing competitive about it, probably because there’s no funding! (Local authority officer, Housing role)

The council has an armed forces champion and that’s helpful, from the point of view of the armed forces applicant, I think that does kinda ratchet up the level of urgency and intervention that is required of us… and there’s more of an argument that all agencies should… be part of the process of identifying what the solutions might be and what extra things they might need to bring to the table in order to make that solution work. (Local authority officer, Housing role)

The second, closely-related issue was that participants across the case studies noted difficulties in sustaining commitment to, and effectiveness of, Covenant Forums over time:

I think with groups like this they tend to burn out after a couple of years, either the group grows beyond all reasonable proportion and you can’t manage anything and it’s never going to achieve anything cause it’s a competition of who can say the most, or people stop coming. (Local authority officer, Housing role)

Now there’s… local authority champions who are doing it because they’ve got an interest, not people who are… the last one to look away from the person in the meeting and therefore they got the role! That’s not helpful…If you get a really interested local authority champion that makes a huge amount of difference. (Staff member, Armed Forces charity)

The impacts of improved collaboration were evident in terms of improved procedures and organisational relationships, which in turn fed through to better outcomes for some veterans. Organisational respondents highlighted the value of increased mutual understanding and trust generated through Covenant Forum networks. This was generally a two-way process, overcoming a lack of understanding of veterans’ issues within the public and mainstream third sector, as well as gaps in understanding about housing legislation and procedures amongst Armed Forces charities:

I think for me working with [Armed Forces charity] is, you know, a better understanding of the issues that veterans face and I think equally from their point of view it’s a better understanding of how we work in housing, cause the key for us really is as soon as we know somebody needs accommodation you need to tell us, not wait till crisis point. (Local authority officer, Housing role)

In practical terms, these increases in understanding and trust translated into improved referral processes, often using an approach which participants described as ‘warm referrals’, involving informal follow-up with both target organisation and client:

If we’re referring to [organisations] there’s a form as such but that’s the formal part, it’s always backed up with an email or a phone call… We like to be a bit of a hub, so I always say to people ‘okay we’re referring you to…’ and in a week’s time you might phone up and say ‘how did you get on?’ ‘well actually they said they’d do this but it’s not happened’ so we might liaise with that organisation and just kinda oil the wheels. (Staff member, Armed Forces charity)

People just signposting the client, the vulnerable clients maybe wandering between agencies without understanding why they’ve been referred from one place to another… And they’re having to tell their story twice/three times. (Staff member, Mainstream third sector organisation)

Partly to manage issues around data sharing, and more importantly to improve accessibility of services, local partnerships developed one-stop shops (areas A, B and C) and/or dedicated posts focused on veterans’ issues (areas B, D and E), drawing on the UK Government’s Covenant Fund to support these initiatives. Whilst the exact form varied, all these initiatives aimed to create a single point of entry for veterans to housing and other welfare systems, which also made things simpler for other services aiming to support clients who identified as veterans:

I think what works well is that there’s somebody there that you can refer to… Also if they need anything at that stage, whether it might be clothes or money, you know, they can help with all the welfare stuff as well, rather than putting them through to another agency to look for support; so they only have to say their story once… If I didn’t do it that way then I would be going from housing to welfare right through the local authority, but they would certainly have to have several appointments. (Local authority officer, Housing role)

Impacts of changes in collaborative practice on veterans’ housing experiences and outcomes

In line with previous research, veteran participants described challenges arising from their lack of experience and knowledge of the civilian housing system, particularly for those Service leavers who had joined the military at a young age:

So I joined when I was 18, left the family home… and then joined the Army, so although I’d had a few jobs before, you don’t know about things like organisations, even just like council tax, you know, all that sort of… cause in the Army you are sort of like just looked after in a way. (Ex-Army, more than 10 years’ service)

It can be confusing… you’ve only just become a veteran so all these things are new to you and people are signposting you – ‘you need this, you need that’, it can be really confusing and there’s a lot of people out there wanting to offer which is great but… there’s almost too many organisations. (Staff member, Mainstream third sector organisation)

I was explaining myself constantly. It seemed like every time I called a number, even if I’d called the same number a few days later, I’d be talking to a different person who I’ve never spoken to before and they have no history or anything noted down, so I’d have to reintroduce myself sort of thing… I’d wait for about two/three weeks and still wouldn’t hear nothing, so I’d ring them back and again it’d be the whole thing again, like, ‘oh we haven’t got nothing down for you’, I was like ‘oh you’re taking the p**s now!’ [laugh]. (Ex-Army, 7–10 years’ service)

Firstly, contrasting with the previous example, some interviewees pointed to strong communication between agencies which prevented them having to retell their story multiple times:

It wasn’t like I always spoke to [person A] and only [he] knew, like when we spoke to [person B] a few days later [he] knew about that… [Person C] was…trying to get our council tax and water rates reduced because there was some special rate for veterans, but they were doing that away from us so we didn’t really have to get involved in it. [Person C] and I think his name was [Person D]… he looked after us as a couple, and he was always in contact with us saying ‘oh I’ve just spoke to them now and they’re going to get back to me’, so people were doing things before we even knew what was going on. (Ex-Navy, 7-10 years’ service)

Secondly, in some areas (especially B, C and E) one of the outcomes of increased mutual understanding across organisations was a recognition that improvements to entry points and smoother referral processes would never completely resolve the difficulties faced by some veterans in finding their way through an unfamiliar and complex housing system. Hence, in these areas the Covenant Forum responded by creating navigator posts:

Veterans were struggling to find what services they need… not knowing where to go and the idea was that they provided these navigators that would help people find the right path… and build a closer knit referral network among people working with the armed forces community. (Staff member, Armed Forces charity)

It’s very helpful knowing that you’ve got someone… that’s obviously fighting your corner so you don’t feel like no one cares and you’re on your own, there’s someone… keeping in contact with you so you know what’s going off… it’s the first time I’ve had a call back and someone’s like ‘yeah we’ll try and help you out’ and not ‘we can’t do this, we can’t do that’. (Ex-Army, 7-10 years’ service)

It’s all a perfect storm because local authorities have had their staffing levels cut, they’re under extreme pressure… So I think some of the ex-services community might get lost in that grouping of people that don’t know how to advocate for themselves, wouldn’t perhaps talk about how well they feel mentally, their notes might be lost because of where they come from and therefore it’s very confusing for them, very difficult to navigate through that difficult process. (Staff member, Mainstream third sector organisation)

Sometimes I’ve found support workers can over advocate and… I think sometimes people [assume] because they’re armed forces leavers they deserve a council house or they deserve a supported accommodation place and actually we deal with a lot of very vulnerable people from all walks of life who are all equally as deserving, and whereas your priority is this armed forces leaver, for us it’s everyone. (Local authority officer, Housing role)

Discussion

Given the paucity of international research, this study provides valuable evidence of the ways in which veterans’ housing needs can be addressed outside the atypical context of the US Veterans Administration. In countries without a large, dedicated public sector body focused on veterans’ needs, the role of collaboration between public and third sector organisations is central to the prevention and resolution of veterans’ homelessness.

The evidence from across the case study areas suggests that there has been a significant step change in collaborative practice regarding veterans, including partnership working to address homelessness and other housing challenges. The creation and evolution of new collaborative mechanisms in the form of Covenant Groups, as well as changes to referral practices and the development of projects such as one-stop shops for veterans represent a substantial growth in the process stream (Powell & Exworthy, Citation2001) underpinning local partnerships. These developments have been driven and supported by central government initiatives in the policy stream, in the form of the Armed Forces Covenant itself (MOD, Citation2011a) and subsequent amendments to homelessness and housing regulations by each of the devolved administrations, alongside investment in the resource stream through the creation of the Armed Forces Covenant Fund.

The increase in local collaboration has, in turn, generated improvements in housing experiences for veterans in housing need, albeit that it is difficult to be certain of the impact on ultimate housing outcomes. In particular, the development of trust and working relationships between organisations in the public and Armed Forces charity sectors have improved mutual understanding and thereby smoothed the housing pathways of veterans. Notably, however, one of the outcomes of partnership working evidenced across the case studies in this research was a collective recognition that collaboration cannot perfectly fill the gaps between organisations or entirely remove bureaucratic barriers. Hence, navigator posts were created to guide veterans through the complexities of the housing system.

sets out these developments in a conceptual model, illustrating the central role of collaboration in meeting the housing needs of UK veterans. This focus on collaboration and the related aspect of navigation is crucial to understanding UK veterans’ housing pathways, contrasting with the situation in the US where the Veterans Administration (VA) provides a unified national service (Cusack et al., Citation2020). Despite the lack of published evidence from other countries, our model may offer more international applicability, given that the VA is somewhat unique in scale and coverage.

Crucially, the policy approach in terms of collaboration in the UK has been relatively light-touch, consisting of encouragement to sign up to the Covenant and a limited amount of dedicated funding resource targeted at building local partnerships to deliver on the Covenant principles (Armed Forces Covenant Fund Trust, Citation2020). From a governance perspective, this absence of mandatory requirements to collaborate in particular ways seems to have supported trust-based network governance, contrasting with more heavily regulated areas of partnership working (Muir & Mullins, Citation2015). The evidence from this study suggests that this form of collaborative network governance has been particularly effective in delivering for veterans in housing need.

Arguably, these partnerships focused on veterans’ housing (and other) needs provide an example of emerging governance frameworks which sit outside the dominant process of top-down partnerships driven by a neoliberal agenda of austerity and a reduced role for the state. In contrast to areas of policy which have shifted responsibility and risk onto communities and the voluntary sector (Rolfe, Citation2018), Covenant partnerships have created a new area of focus for local government, potentially reducing demands on the Armed Forces charity sector.

However, this does not mean that collaboration in this field is unaffected by the wider structural and cultural changes within the public sector. Whilst the partnerships examined in this study were not primarily market-oriented or focused on cost reduction, they did illustrate other facets of new public management in the form of decentralised collaboration and an increased focus on data collection and performance management (Diefenbach, Citation2009). Notably, this move towards towards better recording of veterans within the housing system was not merely being driven by national policy, but also demanded by Armed Forces charities, partly due to a need to compete for funding, but perhaps also due to a longer history of performance management in the military sector (Knafo, Citation2020).

More significantly, recent changes in context and policy approach suggest potential challenges ahead (Future Agenda, Citation2021), not least as a result of austerity. Although the Armed Forces Covenant Fund continues to provide £10 m in grants each year, this represents a significant reduction from the early phases of funding from 2012 to 2018 (National Audit Office, Citation2017), whilst the Armed Forces charity sector is also facing substantial funding challenges. Moreover, since UK Armed Forces are no longer involved in major conflicts, the shift in the public and political spotlight onto pandemic-related concerns may create a significant challenge to the maintenance of local Covenant Groups and related partnership working. This may at least partly explain why the UK Government has opted to place the Armed Forces Covenant on a legislative footing, after a decade of a more voluntary approach (MOD, Citation2021). This shift towards a more hierarchical mode of governance arguably highlights general weaknesses in collaboration based so heavily on shared voluntary commitment, reflecting similar reversions to hierarchy seen elsewhere, especially in a context of austerity (Davies, Citation2012; Penny, Citation2017). Where the policy and resource streams are at risk of running dry, the process stream may in turn slow to a far less effective trickle of activity at the local level, with the potential that veterans will once more fall through the cracks between less joined up services.

Conclusion

The past decade of public and political focus on veterans has generated significant improvements in collaboration across the public and third sectors in the UK, which has in turn delivered better outcomes for those experiencing housing problems. While some individual veterans still experience housing crises, representation of veterans as a group within the homeless population appears to have decreased. The evolution of effective network-based voluntary partnerships is arguably particularly impressive in the context of austerity politics and may hold valuable lessons for partnership working to meet the needs of other groups still at high risk of homelessness, in the UK and other jurisdictions without a dedicated veterans’ administration. The conceptual model developed through this study lays out the key elements of these changes as they relate to veterans’ housing journeys, but also highlights some of the challenges involved.

The development of network governance around veterans’ needs provides a counterpoint to the dominant narrative of 21st century partnership being driven primarily by austerity and new public management principles, ideologically grounded in neoliberalism. And yet, the evidence suggests that the picture is far from straightforward, as changes to the size of the Armed Forces and the nature of operations (Future Agenda, Citation2021) seem likely to combine with ongoing austerity, reinforced by the implications of the pandemic. These changes may create substantial challenges for future collaboration, which may in turn necessitate renewed efforts if the gains of the last ten years are not to be eroded. Understanding the evolution of collaboration to meet the housing needs of veterans in this context involves an awareness of sometimes antagonistic relationships and processes (Newman, Citation2014) between local government, the voluntary sector and national policy. Further research over the coming years will be invaluable to examine changes in the collaborative structures and approaches, and to assess any impacts on the issue of housing need amongst veterans across the UK.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the participants who gave their time to be interviewed for this project.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest arising from this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Steve Rolfe

Steve Rolfe is a Lecturer in Social Policy at the University of Stirling. His work focuses on housing outcomes for vulnerable households and the role of different organisations in supporting tenants. He also has a strong research interest in community activism and empowerment, building on his previous professional experience in local government.

Isobel Anderson

Isobel Anderson is Chair in Housing Studies at the University of Stirling. Her research interests are in homelessness and access to housing; sustainable housing and communities; inequality and social exclusion; housing and health/well-being; participation and empowerment; international comparative housing studies; use of evidence for policy and practice.

Notes

1 The term ‘veteran’ is not unproblematic – in a UK context, many of those who have served in the military prefer terms such as ex-Service or ex-Forces personnel, since ‘veteran’ is often associated in the public mind with those who served in the World Wars (Latter et al., Citation2018). However, this paper uses ‘veteran’ because the term is more widely recognised internationally.

2 Devolution within the UK was introduced in 1999, with significant policy areas being devolved to the newly created Scottish and Welsh Governments, and the Northern Ireland Executive. Defence policy is reserved to the UK Government, but issues related to veterans are largely devolved. Housing policy is entirely devolved (Birrell, Citation2009).

3 We use ‘mainstream’ to make a double distinction in this paper, referring to public and voluntary sector services which are not dedicated solely to veterans – contrasted with the Veterans Administration in the US and with Armed Forces charities in the UK.

4 In the UK, local government has responsibility for preventing and addressing homelessness, but social housing is delivered by a mix of local government (in some areas) and voluntary sector Housing Associations. Homelessness support is also provided through a mix of public and third sector organisations.

5 Note that this study focuses on England, Scotland and Wales. Northern Ireland was excluded because expert advice indicated that security sensitivities would make it difficult to undertake fieldwork with ex-Service personnel there.

6 PRS cost data taken from ONS, Scottish Government and Welsh Government sources.

7 Case study D covered two adjacent local authorities who were working jointly on veterans’ issues.

References

- Armed Forces Covenant Fund Trust. (2020) Five Years of the Armed Forces Covenant Fund: Supporting the Armed Forces Covenant Through Funding Real Change (London: Armed Forces Covenant Fund Trust).

- Ashcroft, M. (2014) The veterans’ transition review. Available at http://www.veteranstransition.co.uk/vtrreport.pdf (Accessed 01 June 2021).

- Bevan, M., O’Malley, L. & Quilgars, D. (2018) Snapshot: Housing (Chelmsford: Forces in Mind Trust Research Centre).

- Birrell, D. (2009) The Impact of Devolution on Social Policy (Bristol: Policy Press).

- CHAIN. (2019) CHAIN Annual Report April 2018 – March 2019 (London: Greater London Assembly).

- Clifford, A. (2017) Evaluation of the West Midlands Housing Scheme for Armed Forces Veterans – Wolverhampton (Wolverhampton: University of Wolverhampton).

- Cobseo. (2020). No homeless veterans. Stoll. Available at https://www.stoll.org.uk/no-homeless-veterans/ (accessed 07 July 2020).

- Cusack, M., Montgomery, A.E., Sorrentino, A.E., Dichter, M.E., Chhabra, M. & True, G. (2020) Journey to home: Development of a conceptual model to describe veterans’ experiences with resolving housing instability, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 310–332.

- Davies, J.S. (2012) Network governance theory: A gramscian critique, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44, pp. 2687–2704.

- Dickinson, H. & Glasby, J. (2010) Why partnership working doesn’t work’, Public Management Review, 12, pp. 811–828.

- Diefenbach, T. (2009) New public management in public sector organizations: The dark sides of managerialistic ‘enlightenment’, Public Administration, 87, pp. 892–909.

- DLUHC. (2021). Homelessness Code of Guidance for Local Authorities (London: Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities).

- Doherty, R., Cole, S. & Robson, A. (2018) Armed Forces Charities’ Housing Provision (London: Directory of Social Change).

- Doherty, R., Robson, A. & Cole, S. (2019) Armed Forces Charities – Sector Trends (London: Directory of Social Change).

- Dowling, B., Powell, M. & Glendinning, C. (2004) Conceptualising successful partnerships, Health & Social Care in the Community, 12, pp. 309–317.

- Feigenbaum, H., Henig, J. & Hamnett, C. (1999) Shrinking the State: The Political Underpinnings of Privatisation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Forces in Mind Trust. (2013). The Transition Mapping Study (London: Forces in Mind Trust).

- Forces in Mind Trust. (2017). Our Community – Our Covenant: Improving the Delivery of Local Covenant Pledges (London: Forces in Mind Trust).

- Future Agenda. (2021). Lifting our Sights Beyond 2030: The Impact of Future Trends on the Transition of our Armed Forces Community from Military to Civilian Life (London: Future Agenda).

- Glouberman, S. & Zimmerman, B. (2002) Complicated and Complex Systems: What Would Successful Reform of Medicare Look Like? (Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada).

- Godier, L.R., Caddick, N., Kiernan, M.D. & Fossey, M. (2018) Transition support for vulnerable service leavers in the U.K.: Providing care for early service leavers, Military Behavioral Health, 6, pp. 13–21.

- Hardy, B., Hudson, B. & Waddington, E. (2003) Assessing Strategic Partnership: The Partnership Assessment Tool (London: ODPM).

- Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Bramley, G. & Gannon, M. (2017) Austerity urbanism in England: The ‘regressive redistribution’ of local government services and the impact on the poor and marginalised, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49, pp. 2007–2024.

- Hickman, P. & Robinson, D. (2006) Transforming social housing: Taking stock of new complexities, Housing Studies, 21, pp. 157–170.

- Hilferty, F., Katz, I., Hooff, M. & Lawrence‐Wood, E. (2021) How many Australian veterans are homeless? Reporting prevalence findings and method from a national study, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56, pp. 114–127.

- Hood, C. (1991) A public management for all seasons?, Public Administration, 69, pp. 3–19.

- Hunter, D. & Perkins, N. (2014) Theories and concepts of partnerships. In D. Hunter & N. Perkins (Eds.), Partnership Working in Public Health (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Huxham, C. (2003) Theorizing Collaboration Practice, Public Management Review, 5, pp. 401–423.

- Johnsen, S. & Fitzpatrick, S. (2012) Multiple Exclusion Homelessness in the UK: Ex-Service Personnel: Briefing Paper no. 3. (Edinburgh: Heriot-Watt University).

- Johnsen, S., Jones, A. & Rugg, J. (2008) The Experience of Homeless Ex-Service Personnel in London (York: University of York).

- Jones, A., Quilgars, D., O., L., Rhodes, D., Bevan, M. & Pleace, N. (2014) Meeting the Housing and Support Needs of Single Veterans in Great Britain (York: Centre for Housing Policy)

- Knafo, S. (2020) Neoliberalism and the origins of public management, Review of International Political Economy, 27, pp. 780–801.

- Kooiman, J. (2003) Governing as Governance (London: Sage).

- Latter, J., Powell, T. & Ward, N. (2018) Public Perceptions of Veterans and The Armed Forces (London: YouGov).

- Lebedev, E. (2015) Homeless veterans campaign: Now we can change more lives for the better – thank you, everyone. The Independent. March 5.

- Lowndes, V. & Gardner, A. (2016) Local governance under the conservatives: super-austerity, devolution and the ‘smarter state’, Local Government Studies, 42, pp. 357–375.

- Lowndes, V. & Skelcher, C. (1998) The dynamics of multi-organizational partnerships: An analysis of changing modes of governance, Public Administration, 76, pp. 313–333.

- Mares, A.S. & Rosenheck, R.A. (2004) Perceived relationship between military service and homelessness among homeless veterans with mental illness, The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192, pp. 715–719.

- Metraux, S., Cusack, M., Byrne, T.H., Hunt-Johnson, N. & True, G. (2017) Pathways into homelessness among Post-9/11-era veterans, Psychological Services, 14, pp. 229–237.

- Miles, M., Huberman, A. & Saldana, J. (2018) Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. (London: Sage).

- MOD. (2011a). The Armed Forces Covenant (London: MOD).

- MOD. (2011b) The Armed Forces Covenant: Today and Tomorrow (London: MOD).

- MOD. (2017) A Guide for Local Authorities: How to Deliver the Covenant in Your Area (London: MOD).

- MOD. (2020) UK Regular Armed Forces Continuous Attitude Survey Results 2020 (London: MOD).

- MOD. (2021). Armed forces bill 2021. Ministry of Defence. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/armed-forces-bill-2021 (accessed 12 April 2021).

- Muir, J. & Mullins, D. (2015) The governance of mandated partnerships: The case of social housing procurement, Housing Studies, 30, pp. 967–986.

- National Audit Office. (2007). Leaving the Services (London: NAO).

- National Audit Office. (2017) Investigation Into the Management of the Libor Fund (London: NAO).

- Newman, J. (2014) Landscapes of antagonism: Local governance, neoliberalism and austerity, Urban Studies, 51, pp. 3290–3305.

- Newman, J., Barnes, M., Sullivan, H. & Knops, A. (2004) Public participation and collaborative governance, Journal of Social Policy, 33, pp. 203–223.

- Peck, J. (2012) Austerity urbanism, City, 16, pp. 626–655.

- Penny, J. (2017) Between coercion and consent: The politics of “cooperative governance” at a time of “austerity localism” in London, Urban Geography, 38, pp. 1352–1373.

- Pollitt, C. & Hupe, P. (2011) Talking about government, Public Management Review, 13, pp. 641–658.

- Powell, M. & Exworthy, M. (2001) Joined-up solutions to address health inequalities: Analysing policy, process and resource streams, Public Money and Management, 21, pp. 21–26.

- Pozo, A. & Walker, C. (2014) UK Armed Forces Charities: An Overview and Analysis (London: Directory of Social Change).

- Quilgars, D., Bevan, M., Bretherton, J., O’Malley, L. & Pleace, N. (2018) Accommodation for Single Veterans: Developing Housing and Support Pathways (York: University of York).

- Rhodes, R. (1997) Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability. (Milton Keynes: Open University Press).

- Robinson, C. (2016) Collaboration on the Front-Line: To What Extent Do Organisations Work Together to Provide Housing Services for Military Veterans in Scotland? (Stirling: University of Stirling).

- Rolfe, S. (2018) Governance and governmentality in community participation: The shifting sands of power, responsibility and risk, Social Policy and Society, 17, pp. 579–598.

- Scottish Goverment (2020). Ending Homelessness Together: Updated Action Plan, October 2020 (Edinburgh: Scottish Government).

- Stoker, G. (2018) Governance as theory: Five propositions, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 15–24.

- Sullivan, H. & Skelcher, C. (2002) Working Across Boundaries: Collaboration in Public Services. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Swyngedouw, E. (2005) Governance Innovation and the Citizen: The Janus Face of Governance-beyond-the-State, Urban Studies, 42, pp. 1991–2006.

- Thurmond, V.A. (2001) The point of triangulation, Journal of Nursing Scholarship: An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 33, pp. 253–258.

- Tsai, J. & Rosenheck, R.A. (2015) Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans, Epidemiologic Reviews, 37, pp. 177–195.

- UK Government. (2018) The Strategy for our Veterans (London: UK Government).

- Welsh Government. (2019) Strategy for preventing and ending homelessness (Cardiff: Welsh Government).

- Wilding, M. (2020) The challenges of measuring homelessness among armed forces veterans: Service provider experiences in England, European Journal of Homelessness, 14, pp. 107–122.

- Wildridge, V., Childs, S., Cawthra, L. & Madge, B. (2004) How to create successful partnerships—a review of the literature, Health Information & Libraries Journal, 21, pp. 3–19.

- Willetts, D. (2019) No more homeless heroes: Our mission to get veterans off the streets and into safety. The Sun. September 29.

- Wood, L., Flatau, P., Seivwright, A. & Wood, N. (2022) Out of the trenches; prevalence of Australian veterans among the homeless population and the implications for public health, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, Online. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13175