Abstract

The supply of social housing has been marked by erosion and decline in most Western Europe countries since the 1990s, albeit with considerable variation in timing, speed and degree. Recently, it has been suggested that the sector has kept a more prominent position at the local level, at least in some cities. This paper scrutinizes this claim by comparing the development of social housing in two cities in two distinct national housing systems that have traditionally had a strong commitment to social housing: Vienna and Helsinki. To do so, we build a multi-dimensional framework that encompasses sector size, stock privatization, new housing production, and residualization. We empirically demonstrate a remarkable stability along these dimensions in both cases, albeit with some differences in degree. A number of factors need to be considered to explain this stability. They relate to aspects of institutional design of the social housing systems, as well as to continuity in policies at national and local levels.

Introduction

The declining relevance of social housing has been a key feature in Western housing systems in the last half century. Whereas in the post-war context the sector developed into a sizable part of the tenure structure in many countries, particularly in Western Europe, since the 1980s, it has been marked by erosion and decline. Alongside shifting policy priorities and economic circumstances, the sector has lost relevance vis-à-vis homeownership, and more lately, specifically in liberal market contexts, private renting. Such a development, with considerable variation in timing, speed and degree, has been observed in a wide variety of housing systems, including the UK, the US, Australia, the Netherlands, Sweden, Ireland, and Germany (Aalbers, Citation2012; Byrne & Norris, Citation2022; Christophers, Citation2013; Forrest & Murie, Citation1988; Harloe, Citation1995; Hochstenbach, Citation2017; Poggio & Whitehead, Citation2017).

To what extent social housing is really ‘a thing of the past’, remains vividly debated, however. Several authors have questioned such a conclusion, based on different grounds. Some agree that the sector has been ‘pushed further to the margins of the welfare state’ (Blackwell & Bengtsson, Citation2021, p. 1), but argue that the changes have not been as marked as foreseen by some observers (e.g. Harloe, Citation1995). Some emphasize recent changes that might require revisiting earlier conclusions (e.g. Kadi et al., Citation2021; Tunstall, Citation2021). Again others (e.g. Mundt & Amann, Citation2010) contend that the argument is based on a narrow geographical scope. This latter literature essentially concludes that social housing has survived to a much larger degree in some countries than in others and broad generalizations should consequently be made with caution. Kemeny (Citation1995) argued some time ago that the sector would specifically retain a more important role in so-called unitary housing systems where it has traditionally held a more prominent position. Stephens (Citation2020), in a recent review of Kemeny’s work, however, concludes that unitary systems are ‘breaking down’ (p. 521) and that the theory was ‘mis-specified’. This paper mobilizes a comparative case study of two traditional social housing cities in two distinct national housing systems to contribute to the literature in two ways: first, it goes beyond the dominant focus on the national level in assessing the development of the sector. Second, it introduces a multi-dimensional framework for such an analysis that draws together different dimensions from the literature to assess social housing stability/decline.

In doing so, we take up recent arguments from the literature. Matznetter (Citation2020), glossing over some of the apparent differences in national developments, argues that non-market rental housing seems to have indeed largely disappeared at the national level across different housing systems. He asserts, however, that such sectors have survived in the urban context in many cases and argues for more research attention to this level. We are sympathetic to this ‘city level’ argument. Yet, we see two omissions. First, empirical evidence on the development trajectory of social housing at the city level remains very limited. In fact, analyses of this sort have largely focused on national housing systems, with most generalizations also deriving from this level. Studies that have looked at the urban scale are much less common, particularly of comparative sort (but see Aalbers & Holm, Citation2008; Blackwell & Kohl, Citation2018; Kadi & Ronald, Citation2014; Lawson, Citation2010). Second, greater conceptual clarity is needed. Authors refer to a number of different processes under the umbrella of ‘social housing decline’. Some stress the shrinking sector size (Byrne & Norris, Citation2022); some point to stock privatization and shifts in ownership patterns (Wimark et al., Citation2020); others emphasize shifts in housing production alongside changing subsidy schemes (Blackwell & Bengtsson, Citation2021; Ruonavaara, Citation2017); again others are concerned with residualization (Musterd, Citation2014). These are all relevant dimensions of the transformation of social housing that have to be considered for a comprehensive assessment of stability and decline. Yet clear distinctions are necessary.

We address these omissions in two ways: First, we provide a comparative case study of Vienna and Helsinki. Both cities have a long tradition of providing social housing, although the specificities of social housing provision differ considerably. Meanwhile, the cities are embedded in two radically different national housing systems, namely Austria, a corporatist-conservative system with a large rental housing stock, and Finland, a traditional homeownership system.Footnote1 If the type of national housing system matters for the development trajectory of social housing, as some authors have suggested (see e.g. Kohl & Sørvoll, Citation2021), we would expect diverging developments in the two cities. Second, we analyze our cases through a multi-dimensional framework of social housing decline/stability that we present below. In it, we draw together the above-discussed dimensions of sector size, stock privatization, new housing production, and residualization. Put together, this allows us to draw conclusions on the trajectory of social housing at the local level that are both broader (including two cases in different housing system contexts) and more nuanced (based on a multi-dimensional framework).

Our time frame ranges from around 2000 towards the year 2020 (we do not include the Covid-19 period as it would require a separate analysis). We choose this starting point as it was a time when in some iconic European cases, particularly the Netherlands and Sweden, the decline of social housing became especially salient, following policies of marketization as well as an EU Competition Law decision and related changes in the social housing supply (Christophers, Citation2013; Czischke, Citation2014; Musterd, Citation2014).

The paper starts with a brief clarification of our conceptualization of social housing before setting up our analytical framework through a literature review on dimensions of social housing decline. We then provide contextual details about social housing in the two cities, followed by a presentation of our results. We find a remarkable stability of social housing in the two cities along the four analysed dimensions, albeit with some difference in degree between the cases. We argue that a number of factors need to be considered to explain this stability. They relate to aspects of institutional design of the social housing systems (poly-centric governance, multi-layered financing and legal setup that has so far proven immune to EU influence), as well as national and local policy stability.

Social housing as a contested concept

Any cross-country analysis of social housing faces the challenge that there is no generally accepted definition of the object under scrutiny. As a tenure, it is a legally-defined term and thus context-dependent. In some places, it is not even legally specified and just a vernacular term. Hansson & Lundgren (Citation2019, p. 204) suggest that it has therefore become ‘a “floating signifier,” i.e. a term with no agreed-upon meaning’. Comparative studies have, however, highlighted a number of criteria that are used in different contexts to define the tenure. Scanlon & Whitehead (Citation2014), for example, point to rent levels (below market), provider type (e.g. government, non-profits or other providers without profit motive), the relevance of subsidies for provision, or the existence of allocation criteria. Depending on the context one or more of these dimensions are typically used for definition.

Certainly, one might argue that this context-specificity calls into question any cross-country comparison of the tenure. We would not go so far, however. In fact, this would call into question most cross-country comparisons in housing systems (cf. Ruonavaara, Citation1993). Rather, we follow Aalbers (Citation2012), Ruonavaara (Citation2017, p. 9) and Blackwell & Bengtsson (Citation2021), among others, that a more abstract cross-country definition is possible and useful, which needs to be amended with the specifics of the tenure in different contexts. Blackwell & Bengtsson (Citation2021, p. 2) provide a straightforward definition that allows for doing so, with social housing constituting ‘rental housing that is operated on the basis of meeting housing need and not primarily in order to make profit for the landlord’. This is general enough to apply to social housing in several contexts and also fits with the broader notion of social housing in our two cases studies. We will use it and clarify further specifics for both cities prior to the empirical analysis.

Unpacking social housing decline

While social housing has grown and expanded across most Western European countries in the post-war period, there was considerable variety in the mechanisms of, and rationale for, the provision of the sector. In some countries, such as Sweden, the Netherlands and Austria, it was designed as a comprehensive part of the housing market, provided by non-profit and/or public authorities and targeted to a wide range of income groups. In others, such as the UK or Finland, it traditionally was more closely focused on working-class households and had a smaller target group (Ronald, Citation2013, p. 3). Form, finance, providers and management of the sector also differed considerably between contexts (Scanlon & Whitehead, Citation2014).

Since the 1980s, however, policies towards the sector have tended to converge across housing systems (Harloe, Citation1995; Jacobs, Citation2019; Scanlon & Whitehead, Citation2014). Alongside a broader restructuring of the welfare state, housing policy more broadly, and social housing policies specifically, have come under pressure. Following Whitehead (Citation2003, p. 60f), this has included 1) reduced subsidies for the sector, 2) a shift from tenure neutrality in subsidies towards targeted demand-side assistance, 3) a move towards market rents, 4) a targeting of social housing to poorer households, 5) greater emphasis on private ownership, finance and management and 6) the promotion of home sales to tenants. Research has disentangled how these changes have led to a declining relevance of social housing in different Western European contexts. Doing so, authors have highlighted particularly the following four dimensions:

Declining sector size: a relative decline in social housing vis-à-vis other tenures, particularly home ownership, and an absolute decline of the stock due to privatization or demolition

Stock privatization: a transfer of units to private owners, either through selling directly to tenants through a Right-To-Buy or en bloc sales to investors, or through a conversion of owners from former public or non-profit entities into private companies

Shifting housing production: a decline in new social housing production, commonly promoted through a shift in subsidies from object-side to demand-side

Residualization: a shift in the socio-economic profile of the tenure towards poorer households, either as a result of intentional policy (such as the tenure reform in the Netherlands following from an EU ruling), or as an unintended side effect of other policy decisions.

Different authors have drawn on different dimensions (e.g. Byrne & Norris, Citation2022; Musterd, Citation2014; Wimark et al., Citation2020). There is, however, surprisingly little work that combines them in a more holistic framework. We will do so to test for social housing stability in our two cases. Following our four dimensions, stability means that 1) the share of the sector in the tenure structure remains stable or grows, 2) there is no significant stock privatization, 3) social housing is newly produced to a significant extent and 4) there is no pronounced residualization.

One might argue that putting these dimensions together in such a way conflates causes and effects. An example is residualization and size. In many cases, residualization has simply resulted from a shrinking stock. As fewer units have become available, the remaining stock has been targeted more closely to lower-income households. As Tunstall (Citation2021) has shown, however, residualization and reduced sector size are not necessarily related. The decline of social housing in the UK since the 1990s, for example, has in fact been paralleled by a process of deresidualization. Therefore, it makes sense to consider both dimensions separately. Another critique might be that the gist of stability or decline may also be captured more easily, by solely looking at sector size. We would argue, on the contrary, that this would be too simplistic. As the literature shows, the process of social housing dismantling has been more multifaceted and goes beyond sector size alone, requiring to consider different dimensions for a nuanced assessment.

With this brief conceptual framework, we now turn to our analysis. Before that, we provide more context for our cases. We discuss the definitional specifics of social housing in the two cities, amending our general definition of the tenure above, and highlight the distinct national housing systems they are embedded in.

Two social housing cities in two distinct housing systems

Both Vienna and Helsinki have a long tradition of social housing provision. The beginnings in Vienna go back to the time of ‘Red Vienna’ in the 1920s, whereas Helsinki developed its first municipally owned rental apartments already at the beginning of the 20th century. Both cities have since upheld a strong commitment to the provision of non-market housing.

In terms of definitional characteristics, there is no official, legal definition of social housing in either city. In Vienna, it is typically used as an umbrella term for two housing sectors: the council housing stock, which is owned and administered by the City of ViennaFootnote2, and the limited-profit housing stock, which is administered and owned by limited-profit housing associations. Both sectors fulfil the criteria of social housing set out by Ruonavaara (Citation2017, p. 9) in that they are not priced by the market and primarily targeted at low and middle-income households. As regards pricing, the mechanisms in the two sectors differ. Rents in limited-profit housing are cost-based and reflect the overall costs of a development project (including financing, land and construction costs). In council housing, rents are set by the City in line with federal rent regulation laws. Average rents in council housing is at around 3.97€/m2 (net rent, excluding utilities and tax) and 4.84€/m2 in limited-profit housing. By contrast, in private rental housing, the average net rent excluding utilities and tax is 6.34€/m2, i.e. 31% higher than in limited-profit housing and 60% higher than in council housing (all numbers for 2016; Tockner, Citation2017). As regards the targeting to low and middle-income households, in both sectors there are maximum income limits for new tenants. They are set at a rather high level, though, to ensure a socially-mixed sector that is not reserved for low-income households. In practice, however, the income profile is typically higher in limited profit housing. A key reason is that tenants, for most units, have to provide a downpayment to enter the sector (comprising a share of the costs for land, financing and construction)Footnote3. Such a downpayment requirement does not exist in council housing. This has traditionally made limited profit housing less accessible for people on lower incomes (Kadi, Citation2015). If the downpayment exceeds a certain amount, tenants can purchase the unit after 5 years through a Right-to-BuyFootnote4. In both the council housing and the limited-profit housing sector, tenants can in principle only be allocated a unit that fits with the current household size (one room per person), although exceptions exist. In council housing, prospective tenants also need to prove a need for housing (e.g. overcrowding in current dwelling, single parent without an own dwelling, elderly or disabled people in need of a different flat). There is also a separate share of the council housing stock reserved for former homeless people.

In contrast to Vienna, social housing in Helsinki (as in Finland) is officially called ‘government-subsidised rental dwellings’, which in everyday language transforms to ‘subsidized housing’. It is an umbrella term that includes student housing, housing for residents with special needs, such as the elderly or physically disabled, as well as right to occupancy-housingFootnote5. Another term used in Finnish for government-subsidised rental dwellings (excluding student housing) is ARA-housing, which refers to the governmental agency called ARA (The Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland). ARA implements social housing policy, and in particular guarantees bank loans for government-subsidised rental dwellings, and pays an interest subsidy if interest rates succeed a specific limit (currently 1,7%). In this paper, we focus specifically on the segment of social housing called ARA-rental housing (excluding student housing), which is social housing directed to middle- and low-income households and with this target group shares similarities with council and limited-profit housing in Vienna. Local authorities (municipalities), as in Vienna, and other public corporations are the largest owners of social housing in Finland. However, in contrast to Vienna, corporations that fulfil certain preconditions and limited liability companies of various types (but in which local or public authorities or corporations under certain preconditions have direct dominant authority) can also develop social housing (ARA, Citation2013/2015). There are specific rules for rent setting, set and monitored by ARA. These include capital expenditure (such as interests and amortization as well as rent of the plot) and maintenance costs (janitorial services and maintenance, water heat, cleaning of stair cases, and common spaces, waste management and property management). Part of the capital expenditure is shared among all tenants of the social housing provider – not, as is the case in Vienna’s limited-profit housing stock, shared among tenants of one housing estate. Small renovations, maintenance costs, and some specific features of the building such as location are taken into account when setting the rent for one housing estate. Social housing in Helsinki cost between 10€ to 15€ per square meter (gross rent, average 12,75 €/m2) (Vuokranmääritys Hekassa, Citation2017), while the average market rent (gross rent) in 2017 was 19,58 €/m2 (i.e. around 53% lower). It is developed on land owned by the city, and the city subsidizes social housing by giving a reduction of the plot lease. In contrast to Vienna, there are currently no income limits for applicants or residents in social housing in Finland, but there are specific criteria for tenant selection set by ARA. Today the criteria include housing need (for example risk of becoming homeless, having limited dwelling space and living in expensive housing relative to income), wealth and income (low- and middle income applicants being understood as having a more urgent need for social housing than higher income applicants) (ARA, Citation2021). Social housing can be sold off, or converted into private rentals after a period of 20–45 years, which is typically the amortization period of the state subsidized loans ().

Table 1. Some key differences between social housing in Vienna and Helsinki.

While both Vienna and Helsinki have a long tradition of social housing provision, they are embedded in distinct housing systems. Austria is an example of a conservative-corporatist housing system with a large rental sector (Matznetter & Mundt, Citation2012). With a home ownership rate of some 48.8% in 2020, the country has one of the fewest home owners in Europe. Meanwhile, with some 23.5%, it has one of the highest social housing rates (Statistik Austria, Citation2021, p. 110). Austria has been identified as an example of a unitary or even an integrated rental market (Mundt & Amann, Citation2010), although the liberalization of rent regulation in the 1990s has triggered a dualization between private and social rents and thus challenged this categorization to some extent (Kadi, Citation2015). In contrast to Austria, Finland has been characterized as a homeowner society, with 62% of all households living in owner occupation in 2020 (Statistics Finland, Citation2021). Until the 1990s, both owner occupation and social housing construction were supported through state subsidized loans. Today homeownership is supported through tax reliefs for households with housing loans (this will end in 2023 however). Rent regulation was at work until the 1990s, when housing policies retrenched (Juntto, Citation1990; Ruonavaara, Citation2017). The rental market today is in Kemeny’s classification dualist (Bengtsson et al., Citation2017), with unregulated private rents and cost-based, regulated rents in social housing. Out of all apartments in Finland 7,7% are ARA social rentals, 4,9% other ARA housing, 24,7% private rentals, 11,6% other unregulated housing and 51,1% owner occupation (ARA, Citation2019). The private rental sector has grown substantially in all larger cities, especially in the last 15 years, and the number of renters has also risen. The change in policies has also resulted in social housing being converted into private rentals or owner occupation (Lilius & Hirvonen, Citation2021; see also below).

The recent development of social housing in Vienna and Helsinki

Sector size

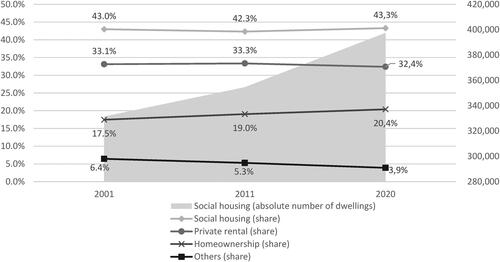

Social housing is the largest sector in Vienna to date. In 2020, it accounted for some 43.3% of all units, with council housing and limited profit housing each making up about half of the stock (21.9% and 21.4%). The second largest sector are private rental units, with about 32.4%. Homeownership, predominantly in the form of flats, rather than single-family homes, accounts for some 20.4%. If we look at the size of the social housing sector over time, we can see that it decreased to some extent between 2001 and 2011 and has increased slightly in the last decade, so that it remained overall stable when 2001 and 2020 are compared (). The private rental market has slightly shrunk since 2001 whereas the home ownership sector has seen the starkest growth, from 17.5% to 20.4%.Footnote6,Footnote7

The relative development conceals the stark absolute growth of social housing in the city, however. Whereas in 2001, some 302,000 units belonged to either council housing or limited-profit housing, in 2020, this had grown to around 397,000 units – an increase by 23.9% within the sector over 20 years alone. The great majority of new units came from the limited-profit housing associations. This sector grew by some 75%, from 112,000 units in 2001 to 196,000 units in 2020 (see section ‘New production’ below).

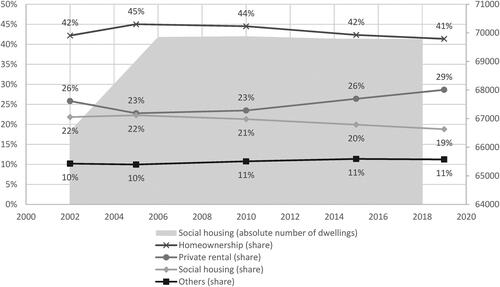

The homeownership rate in Helsinki is 41 percent, while some percent account for right of occupancy flats (Helsingin seudun aluesarjat, Citation2021). Social housing accounts for 19 percent of all housing (Asumisen ja siihen liittyvän maankäytön toteutusohjelma, Citation2020, pp. 22–23). The proportion of the different tenures have remained fairly stable throughout the last two decades (). The private rental sector has grown the most after a slight decline. Homeownership has also declined by 4 percentage points after initial growth. Social housing, meanwhile, has declined by some 3 percentage points between 2002 and 2019.Footnote8 This contrasts to Vienna, where the sector has by and large remained stable since 2001 in relative terms. Differences in the absolute development of the social housing stock are starker: whereas in Vienna, the social housing stock grew moderately in the 2000s and more quickly since then, in Helsinki, it was the other way around. A comparably pronounced growth in the first half of the 2000s and a stable number of units since then. Overall, however, the scale of change was much bigger in Vienna: here, the stock grew by more than 60.000 units between 2001 and 2020, whereas in Helsinki, it grew by some 3.200 units.

Stock privatization

Privatization has been a rather marginal phenomenon in Vienna’s social housing stock, compared to other European cities such as Berlin, London or Amsterdam, where the sector has been reduced significantly in that way. In Vienna, three types of privatization are relevant. First, so-called a-typical council housing units were sold. These were former privately owned estates that the city had acquired through endowment or bequest. Some 500 units in 39 estates were sold through these means (Kontrollamt, Citation2002). Second, limited-profit housing associations that used to be owned by the federal government were sold under a right-wing federal government in the early 2000s and thus some 60.000 units in Austria were privatized. The most prominent case is the housing association BUWOG, which by now is owned by the largest German real estate company Vonovia. Third, there is an ongoing privatization in the limited profit housing stock through a right-to-buy. Tenants are offered their unit after 10 years – recently changed to 5 years. Up until 20 years after they have moved in, they can purchase the unit. There are regulations regarding the future sale and use of the unit as a private rental unit after purchase. These rules have recently been tightened (Arbeiterkammer Wien, Citation2022). Annually, some 800 units are sold in Vienna in this way (Österreichischer Verband gemeinnütziger Bauträger (GBV), Citation2016). While the social housing stock has been reduced through these three means of privatization, in comparison to the overall stock, they have remained limited and in combination with continued production of new units, the social housing stock has, as shown, remained stable in relative terms and grew absolutely.

Compared to Vienna, privatization has been a rather prominent phenomenon in Helsinki. The City of Helsinki currently owns 17 of the 19 percent that account for social housing in the overall housing stock. The remaining 2 percent are owned by A-Kruunu, a state owned company (founded in 2015) assigned to construct social housing, and Y-säätiö, a foundation addressing homelessness by constructing homes for homeless people (Asumisen ja siihen liittyvän maankäytön toteutusohjelma, Citation2020, pp. 22–23). Nevertheless, the ownership structure of social housing has changed dramatically. In 2004 more than a third of the government subsidised rental flats (24 000) were still owned by two non-profit companies and the rest (45 000) by the City of Helsinki (Vihavainen & Kuparinen, Citation2006, p 17). The two largest non-profit social housing providers, Sato and VVO transformed their business strategy when rent regulation was abolished in the 1990s and become real estate investors.Footnote9 They have since converted and sold off most of their social housing stock. Whereas SATO still owns some social housing, VVO sold its last social housing flats in 2016 (webpage of Kojamo, Citation2021; webpage of Sato, Citation2021). As showed, the share of social housing has remained at a high level despite conversions. This is mainly because the City of Helsinki has actively produced new social housing.Footnote10

Figure 2. Tenure structure Helsinki 2002–2019 and absolute number of social housing units.

Source: Helsingin seudun aluesarjat (Citation2021).

New production

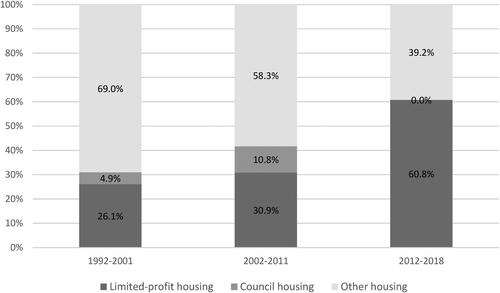

Social housing accounts for a substantial share of new housing production in Vienna. Between 2012 and 2018, more than 60% of the units were constructed in the limited-profit housing sector (see ).Footnote11 This amounts to a substantial increase compared to the last two decades, when the share of social housing stood at around 40% (in the 2000s) and 30% (1990s). Rather than a decline in new production, as was the norm in many other European cities, social housing has thus actually increased its significance. Noteworthy, the share of council housing has increased from the 1990s to the 2000s, but has since then vanished. This is related to a decision by the City of Vienna to terminate new construction in the sector as of 2004 (except attic conversions and amendments of existing estates). New social housing production has subsequently been taken over by limited-profit housing associations (Kadi, Citation2015). This also explains the stark growth of the limited-profit housing sector compared to the council housing sector discussed above. In 2015, the City announced that it will restart the council housing program and build 4,000 new units until 2025 (Wiener Wohnen, Citation2019). The impact of this will be limited, however, as the 4.000 units will not even be able to keep the relative share of the council housing sector in the overall tenure structure stable, given the current scope of housing construction in the city (Kadi et al. Citation2021).

Figure 3. Share of social housing (limited-profit housing and council housing) on new housing production in Vienna 1992–2018.

*Source: Own calculation based on Statistik Austria, several years.

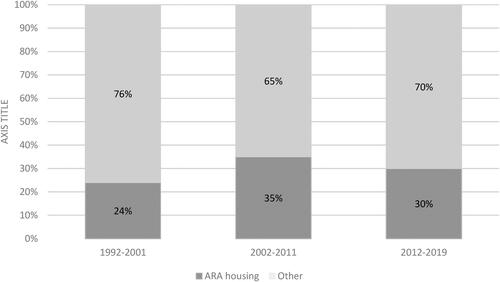

According to the current Housing Programme in Helsinki, 30 percent of all new apartments should be government subsidized rental flats. Around 8 percent of these flats should be student housing or housing for young people, and the remaining 22 percent realized as social housing or housing for special groups. Half of the new stock should be owner occupation and private rental units, predominantly flats but also single-family houses, row houses or town houses, and the rest should belong to the so-called intermediate forms such as price regulated owner occupation housing (Asumisen ja siihen liittyvän maankäytön toteutusohjelma, Citation2020). The City allocates plots for new social housing according to the Housing Program. The relatively high landownership of the City (64,2% in total), ensures the availability of plots. As shows, there has been a steady development of social housing, although the numbers fluctuate. Yet the new production has substantially helped to level out the amount of lost converted social rental flats discussed above.

Figure 4. Share of social housing (ARA housing) on new housing production 1992–2019 (Helsingin kaupunginkanslia, Citation2021)*.

*ARA housing here includes also right of occupancy and social housing for special groups.

Residualization

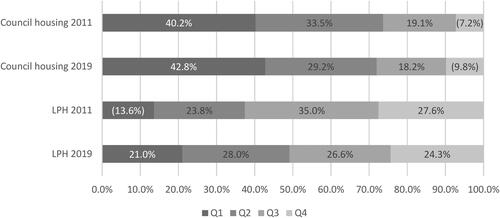

Residualization of social housing in Vienna has to some extent taken place, but on a rather moderate scale. One thing to consider is that both council housing and limited profit housing are traditionally very mixed socio-economically. This does not only result from the fairly large size of both sectors, but also from the rather high income limits. In 2015, the income limits were even raised to make the social housing more accessible for middle-income households (while new rules were introduced to privilege residents that have lived in the city for longer). Council housing has traditionally housed more lower-income households compared to limited-profit housing. In both sectors, however, households from all income groups are typically present. This is also visible from that plots the profile of the two sectors by city-wide income quartile. In 2011, some 40.2% of the tenants in council housing came from the first income quartile. In limited-profit housing, this was clearly less, with some 14%. In both sectors, however, the majority of tenants came from higher income quintiles – in council housing some 60% and in limited profit housing even more than 85%. In both sectors, a sizable share of the tenants also comes from the upper two income quartiles, although they hold a more important share in the limited-profit housing stock.

Figure 5. Population profile by income quartile of council housing and limited profit housing in Vienna, 2011 and 2019*. *Numbers in brackets are based on small sample and should be interpreted with caution.

Source: EU-SILC, Citation2011; Citation2019.

furthermore shows how the income profile in the two sectors has changed. In both sectors, the share of residents from the first income quartile has increased, indicating a certain residualization. The dynamic is somewhat different in the two sectors however. In council housing, the first income quartile gains ground vis-a-vis the second and third income quartile, i.e. the lower and upper income middle-class. In limited-profit housing, meanwhile, all other income quartiles lose importance vis-a-vis the first quartile. What is more striking, however, is the different degree of change. In council housing, the residualization trend is much more moderate than in limited-profit housing, signalling that the process has been more important in the latter sector in the last ten years. It is questionable, however, whether residualization is really the right term to describe these shifts in limited-profit housing. The sector has further expanded in size and, even if the tenant profile has become somewhat lower-income, still some 50% of the tenants come from the two highest income quartiles. Nonetheless, if we look at the trends in the income profile of both sectors, the changes indicate a certain harmonization, with the limited-profit housing profile resembling the council housing profile somewhat more than ten years ago. Both sectors, however, remain quite mixed socio-economically.

As in Vienna, there have also been attempts in Finland and Helsinki to direct social housing towards middle-income households. To have a better social mix in social housing and avoid residualization, income limits for applicants were abolished in 2008 (Hirvonen, Citation2010, p. 14). A follow up study in 2010 however revealed that income levels of neither residents nor applicants had increased since the implementation (Hirvonen, Citation2010, p. 75). Nevertheless, in 2017 the national government re-introduced income-limits, with the aim to direct social housing towards low-income households (Strategic Program of Prime Minister Juha Sipilä’s Government, Citation2015). A study by the City of Helsinki (Vuori & Rauniomaa, Citation2018) in 2018 showed that out of all tenants, only five percent, mostly single households, had incomes above the implemented income limits. The gross-income of the residents was almost 40 percent lower than that of the average income resident in Helsinki. Considering the results of the study (among other issues), the City of Helsinki and other social housing providers found the income limits unnecessary, and they were abolished in 2018 by the same government that implemented them. Today more than half of the residents in social housing owned by the City of Helsinki belong to the three lowest income groups (1., 2. and 3. decile). Two percent of the residents belong to the second highest income group (9. decile), and zero to the highest (10. decile). In the social housing stock owned by other providers 44 percent belong to the third lowest income groups. Homeowners in Helsinki, and those who rent on the private market (excluding students) correspondingly belong to higher income groups (Hirvonen, Citation2021). In conclusion, social housing has remained housing for low-income residents. Nevertheless, to avoid stigmatization and a concentration of deprivation in social housing, the city has designated civil servants who take care of the tenant selection. They monitor each staircase to reach a balanced social structure of tenants (in accordance with national regulations for tenant selection). In practice this means that staircases with only one ethnic group, or only unemployed tenants are, for example, avoided.

Discussion: Accounting for stability

Considering the two cases comparatively, we see some differences along the four dimensions (see ): a stable sector size in Vienna and a slight decline in Helsinki alongside a much more pronounced absolute unit increase in Vienna; stock privatization has been a rather marginal phenomenon in Vienna, while in Helsinki, the privatization of two social housing providers and their stocks made it a more significant process; the share of social housing in new housing production has been around 30% in Vienna in the 1990s and 2000s, whereas it has increased to more than 60% over the last ten years. Meanwhile, in Helsinki, the sector has made up around 30% of new construction over the last three decades, with no comparable recent increase. Nonetheless, these differences largely constitute differences in degree, rather than in kind. The common trajectory that becomes evident from both cases is that the social housing sector remained by and large stable in both cases, privatization took place to some extent but was made up through new construction, the sector plays a significant role in housing production and residualization plays a rather marginal role. All in all, there is thus a remarkable stability in the sector in the two cases that runs counter to dominant narratives about the current development of social housing in the European context.

Table 2. Comparative overview of analyzed dimensions.

How to explain this stability? We have highlighted how the decline in social housing across several West European housing systems has been driven by a set of intertwined policy shifts since the 1980s, including, inter alia, reduced subsidies for the sector, a shift to demand-side assistance, an introduction of market rents, a targeting of the sector to lower-income households, greater emphasis on private ownership, finance and management, as well as the promotion of home sales to tenants (Whitehead, Citation2003, p. 60). In Vienna and Helsinki, by contrast, we see remarkable stability along different of these dimensions. Why is this the case?

Blackwell & Bengtsson (Citation2021) explain the stability of social housing in Denmark vis-à-vis the cases of the UK and Sweden with two features of the Danish system: first, a ‘polycentric governance system’, in which authorities at different scalar levels exercise certain degrees of control. Changes, such as decisions to privatize, can thus not easily be pushed through (Blackwell & Bengtsson, Citation2021: 16). Second, a multi-layered financing system that is less reliable on central government contributions and thus also less vulnerable to cuts on this level (Blackwell & Bengtsson, Citation2021: 14). Both arguments are important for our cases.

In Vienna, decision-making is divided between national and provincial level, with some additional room for manoeuvre for housing associations (regarding tenant selection, decision on new construction and asset management). The federal government is in charge of important legal acts (e.g. the limited-profit housing act and the Tenancy Act). Until 2018, it also collected and redistributed housing taxes to lower governmental levels (since then this is done by the provinces). At the provincial level, Vienna, decides about the specific use of housing subsidies (since 1989), is responsible for zoning and planning decisions and the management of publicly owned land. Moreover, Vienna, like other provinces, is an important owner of social housing. There was a short moment in the early 2000s where it became clear how this governance structure curtailed federal privatization plans. Back then, a right-wing federal government planned to privatize housing by limited-profit associations owned by public authorities. The initial plans included a sale of a substantial amount of no less than 22% of the then 480.000 limited-profit housing units (Mundt, Citation2008). Several provinces and municipalities, who in many cases owned the associations, however, vetoed against this. Eventually, some 60.000 units of associations owned by the federal government were sold (Mundt, Citation2008), with the remaining associations and units staying in public ownership.

In Finland too, the central government is in charge of the legal acts concerning social rental housing. The Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland (ARA) steers and monitors social rental housing by, for example, granting the guarantees for loans and monitoring that the rents are cost-based. The interest subsidies, when granted, are also paid by the Housing Foundation of the State (VAR), and the government decides the threshold for when these subsides are paid (currently if interest rates rise above 1,7%). It is however the owners of social rental housing who are in charge of steering tenant selection and setting rents (according to the law). As in Austria, it is at this level of ownership where the polycentricity argument became visibly relevant. When the government in power between 2015 and 2019 suggested temporal contracts in social rental housing in cities, the City of Helsinki, the largest owner of social housing in the country, prepared plans to buy out the entire stock from the centralized system (in other words convert it to social rental housing under rules set by the City). Helsinki did not want to take on the administrative burden of checking residents’ incomes every five years, nor commit to a system where residents would be thrown out of their homes if their incomes grew.Footnote12 The government later withdrew from its plan. As in Austria, polycentricity curtailed significant changes to the sector.

The financing argument by Blackwell & Bengtsson (Citation2021) is of relevance for both cases as well. In Vienna (as in Austria), the reliance of limited-profit housing associations, which are the key provider of social housing nowadays, on regular government contributions is limited. The associations get a considerable part of financing for new projects, typically around 1/3, from capital loans from special purpose housing construction banks. Other parts come from the associations’ own equity (around 10–20%) as well as from tenant downpayments. While around 1/3 typically comes from low-interest public loans, most of the funds for that (∼60%) are from loan repayments by associations to governments, minimizing the need for additional funds (Pittini et al. Citation2021, p. 11). Meanwhile, the credit conditions of the associations improve over time. They use their housing as collateral to guarantee the loans. Over time, their housing stock becomes bigger, providing them with better credit conditions, lower financing costs and thus make them less dependent on state support (Matznetter, Citation2020). In Finland, even more, all loans to develop social rental housing are today taken from private banks. Due to the large housing stock of Helsinki, it is likely that the City could acquire a loan also without a guarantee from the central government which would give the City the possibility to develop their own social rental housing system, if necessary.

While certain independence from national government in both decision making and financing is thus important, it is in fact also stability in national policy that is relevant to understand the continuities in social housing development. In Austria, the post-war consensus between Social Democrats and Conservatives over the usefulness of housing market intervention has been upheld to considerable degree also under different coalition constellations in recent decades. The high relevance of object-side subsidies in funding for housing is a striking indicator of the continued commitment to social housing in particular. In 2011, some 62.9% of housing subsidies in Austria were granted through object-side subsidies. By comparison, in Great Britain, it was 11.1% (Wieser & Mundt, Citation2014, p. 254). A recent pan-European study found that EU member states only spend an average of 26.1% of their housing budgets on object-side subsidies (Housing Europe, Citation2019, p. 28).

This is not to say that policy retrenchment played no role. Federal funding for housing subsidies declined in Austria in real terms since the mid-1990s, the earmarking of housing subsidies was abolished (Streimelweger, Citation2014) and a right to buy was introduced in parts of the limited-profit housing stock (Mundt, Citation2018). In the longer view, the relevance of subsidized housing in new construction in Austria has also declined. Whereas in the period 1992–2002, 80% of new construction received subsidies, this has declined to 49% for the period 2007–2017 (Kadi et al., Citation2020, p. 3). Still, by and large, the national level has shown fairly strong continuity in supporting social housing. Resultantly, in stark contrast to other European countries, the sector increased rather than shrunk, from 19.5% in 1991 to 23.5% in 2019 (Statistik Austria, Citation2013, Citation2021).

In contrast to Austria, in Finland, broad support along the political lines (also social democrats) in terms of housing tenure has traditionally been for homeownership. The development of housing subsidies after WW II was linked to communists and left-wing parties gaining more power (Ruonavaara, Citation2006). However, today, there is a consensus on the need for social housing in city regions. The commitment of national government to the sector is highlighted in the so-called MAL-agreements (land use, housing, traffic) between the municipalities in the Helsinki Region and the government. The government pays a start-up grant (€10 000/social housing unit) and the current government program has the goal to increase the proportion of ARA housing in new production to at least 35 percent – substantially higher than the goal of the previous government, which stood at 25 percent. If the municipalities reach this goal, they get state support for larger infrastructure developments (Ministry of Environment, Citation2021b).

Certainly, retrenchment has occurred in Finland too. Subsidies to develop social housing have declined substantially since the 1990s, and target mainly special groups. Hyötylainen (Citation2020) calls this the ‘specialization’ of social housing in Finland, referring to the decline of support for social housing directed to low and middle-income households. The subject side subsidies on the other hand have grown exponentially in the 2000s, with housing allowance being the most important one. In 2019, subject side subsidies accounted for more than 90 percent of housing subsides (90.8% being paid as housing allowances and 2.5% as tax relief for homeowners). In 2019, 6% of the subsidies were directed to the object side (out of which nearly half addressed housing for special groups) (Hurmeranta, Citation2020). Resultantly, from 2000 to 2017 the number of social housing flats decreased by 16% in the whole country, while private rental grew by 50% (ARA, Citation2019). Despite this, with the above-discussed instruments, the national government still plays a key role in supporting municipalities in social housing development and has shown a considerable degree of policy stability.

Austria’s policy stability has been related to the continued cross-party acceptance of the benefits of social housing (Lawson, Citation2010), the political power of the well-organized limited-profit housing sector (Matznetter, Citation2020), and the slow, incremental change of conservative-corporatist welfare regimes that has left the post-war model more intact that in other contexts (Matznetter, Citation2020). Importantly, as WIFO (Citation2012) argues, a key driver of this model were economic policy rather than social policy concerns (see also Matznetter, Citation2020). Housing decommodification, alongside its social and welfare benefits, was seen as an effective instrument to promote stable employment, keep wage claims of workers at a moderate level and foster international competition of the economy. In Finland, between the 1970s and 1990s, the provision of social housing was, to considerable extent, linked to promoting the construction industry, which traditionally has close ties to both the social democratic and conservative party (Hankonen, Citation1994; Juntto, Citation1990; Ruonavaara, Citation2006). Today’s consensus on the need for social housing in cities mainly comes out of urban labour market concerns. It is seen as a means to ease mobility from declining places to growing regions, and considered crucial in order for key workers in low paid jobs to find housing in growing cities (Programme of Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government, Citation2019). As in Austria, economic policy concerns thus play important parts, although in different variants.

While continued national influence is relevant in both cases, it is also the lack of influence of a scalar level – particularly the supra-national level – that requires consideration. The Netherlands as well as Sweden, two countries with comprehensive social housing supplies, have restructured their sectors following measures at the EU level in response to complaints by private landlords about unfair competition through housing subsidies in the early 2000s. The Netherlands introduced stricter income limits and targeted the social housing sector more closely to lower-income households. In Sweden, the parliament ruled that Municipal Housing Companies needed to operate in more business-like ways, aiming to create a more level playing field with commercial housing providers (Czischke, Citation2014; Elsinga & Lind, Citation2013). In Vienna, this issue has so far played no role. The Austrian system of social housing has at least so far proven resilient in legal terms (Streimelweger, Citation2014). This also holds for Finland and Helsinki. There are eligibility criteria for tenant selection, meaning that the subsidies of the state are directed to a specified target group already. On the other hand, in Finland, the interests of private landlords have been put forward in other ways. As a consequence of the abolishment of rent regulation in the 1990s, the biggest providers of social housing in Finland became housing investors. The conversion of their stock resulted in a decrease in the availability of social housing. The private rental stock during the same time has grown remarkably and become increasingly profitable.

Finally, and further amending the account put forth by Blackwell & Bengtsson (Citation2021), local policy stability is an important factor. Both cities hold considerable power in housing policy making and have shown continued commitment to social housing. In Vienna this is reflected, not least, in the high share of social housing in new production, the decision not to sell council housing (apart from a few estates), or the provision of additional funding for subsidized housing on top of the funds received from federal government (before the decentralization of tax collection). While in Vienna, the Social Democrats have been in power for most of the last 100 years and housing market intervention is tightly linked to this political stability, in Helsinki, political majorities have varied over time. Still, targeted goals for the production of housing have been prepared by the city administration since the 1940s. Today these housing programs typically last for the legislative period of the city council. The programmes set goals for the production of new housing, and project land owned by the City for this purpose. The City’s own housing production company ATT (City of Helsinki housing production), founded in 1948, is still responsible for realizing much of the housing production in accordance with the City’s housing policy goals. ATT in other words works as a developer and contractor, although this may vary depending on the project.

The local commitment to social housing in Vienna has been interpreted as an expression of a more ‘social’ urban politics and the result of less competition oriented forms of governance, set within the long-term power stability and reign of the Social-Democrats (cf. Hatz et al. Citation2016). Path dependence is likely to play important parts, too. With the long history of intervention, a retreat from social housing may result in quick political losses at the next election – a risk the party does not want to take. Initially more social forms of governance are thus becoming locked-in, made possible by the fairly stable national and institutional circumstances. At the same time, the policy model has also become more heavily contested, with the real estate lobby pushing the City more directly than in the past to adopt a more market-friendly approach (Kadi, Citation2015; Novy et al. Citation2001). Rather than political stability, in Helsinki, pragmatic economic policy plays important parts in explaining policy continuity. The high demand for ‘key workers’ is seen as a justification for policy intervention, also at the local level, stabilizing commitment amidst changing governing majorities. Meanwhile, there is considerable pressure to change the system for some time already. Local income taxes are a main source for local revenues in Finland. This makes cities compete for wealthy residents and puts pressure on local social housing policies (Haila & Le Galès, Citation2004).

Concluding remarks

While the social housing sector has been marked by erosion and decline in most Western European countries in recent decades, in this paper we have demonstrated a remarkable stability in the supply of social housing in two cities. By doing so, we have advanced on the research gap identified by Matznetter (Citation2020) according to which the local level is often overlooked in debates about the decline in social housing in the current context. Comparative accounts are particularly rare in this regard. We have, however, not only considered two local cases in two radically different housing systems comparatively, but also did so through a multi-dimensional framework that allows for a more nuanced assessment of the development of social housing than most other recent accounts on that issue. Thus, the paper adds a novel level of understanding through a rarely considered scalar level, a comparative rather than a single case study, and a more differentiated analytical framework than most existing studies.

The two cases provide a remarkable counterpoint to dominant narratives about the development of social housing in the European context along multiple dimensions commonly used to characterize the decline of the sector: it did not lose its strong position in the tenure structure, privatization did not play a major role, it still features prominently in new construction, and it has not been residualized to a significant extent. We have argued that a number of factors need to be considered to explain this stability: aspects of institutional design (poly-centric governance, multi-layered financing, and legal setup that has so far proven immune to EU influence), national policy stability rooted, to considerable degree, in economic policy concerns, as well as local policy stability, resulting from different political and economic considerations in the two cities.

Our evidence supports arguments that notions of social housing decline are often based on a narrow geographical scope (e.g. Mundt & Amann, Citation2010). The case for this is usually made with regard to the national level. Here, we argue, in line with Matznetter (Citation2020), that it is the local level that runs counter to dominant accounts how the sector has developed. Strikingly, the analysis also does not confirm that the national housing system type matters for the development of social housing at the local level. A potential explanation may lie in the historically grown discretionary power at the local level, embedded within a multi-scalar policy system.

Although the analysis solely touches on a selected number of dimensions of social housing in the two cases, it nonetheless provides a noticeable correction to dominant narratives about the development of the sector in the current context. There is so far, however, still limited systematic evidence on social housing development on the local level beyond the cases studied here and the issue should thus be explored further. Meanwhile, recent evidence suggests that some cities have started to re-invest into social housing in the context of rising housing problems and protests in recent years and there are thus new developments to consider (Kadi et al., Citation2021).

Despite the stability in the supply of social housing, in both our cases, housing problems exist and have become more pressing recently. The City of Helsinki, for example, had almost 23 000 applicants for social housing in 2020, but were able to convey only a little above 3000 flats during the year (City of Helsinki, Citation2021). Also in Vienna, waiting times for social housing are often significant and the explosive increase in private rents in recent years has reshaped housing conditions (Kadi, Citation2015). Social housing contributes markedly to the supply of inexpensive housing in both cities, but interacts with demand-side developments as well as dynamics in other tenures in shaping housing outcomes. Our paper has highlighted the complexity and context specificity in the provision of social housing. Future studies are needed to understand the interplay of the sector with further relevant housing market dynamics in determining housing conditions in both cities and other cases where social housing continues to play a key role in the urban housing system.

Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous reviewers and the editor for useful feeback and suggestions. The paper draws on data from the Eurostat, EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions. The responsibility for all conclusions drawn from the data lies entirely with the authors. We acknowledge funding from the TU Wien Bibliothek Open Access Funding Programme. The research was supported by the The Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland (Foundation´s Post Doc Pool).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Despite this difference, it is noteworthy that the two countries have both been classified as conservative welfare states, e.g. by Esping-Andersen (Citation1990).

2 Strictly speaking, the sector is administered by Wiener Wohnen, a city-owned company.

3 Downpayment requirements vary considerably between projects. Korab et al. (Citation2010) found an average of 500€/m2. The City provides low-interest loans to support tenants in affording downpayments. (Eigenmittelersatzdarlehen). Downpayments are paid back to tenants once they move out, deducted by a 1% annual administrative fee. The City has implemented a new subsidy program, Smart Housing, with below-average downpayment requirements (Stadt Wien, Citation2019).

4 This does not apply to units that are built on leased land.

5 The tenure is a mix between rental and owner-occupied housing, where residents pay a right-of-occupancy fee when they move in (10–15% of the original cost of the flat, which is returned when moving out) as well as a monthly management fee to the owner of the building. The apartments are typically financed with state-subsidised housing loans or interest subsidy loans. (Ministry of Environment, Citation2021a). Currently 3% of the housing stock in Helsinki consists of right-to-occupancy housing.

6 Overall, the share of social housing has also remained fairly stable in most other large Austrian cities, with Vienna thus not being an exception. As a rough indicator, between 2013 and 2020 the share of social housing in all cities >100.000 people except Vienna changed from 33.3% to 31.5% (Statistik Austria, Citation2013, Citation2021).

7 In absolute terms, Vienna also has by far the largest social housing stock of all Austrian municipalities. In relative terms, it is not Vienna but the city of Linz, provincial capital of Upper Austria, which has a larger stock, with some 54% (2019; Housing Europe, Citation2019)

8 In that, Helsinki has maintained its social housing to a much greater extent than other large cities in Finland. In the second largest city, Tampere, for example, it declined by 17 percent (ARA, Citation2019, p. 7).

9 SATO (Sosiaalinen Asuntotuotanto, social housing production) was founded in the 1940 by companies in the building materials sector, construction companies and certain insurance companies to develop housing in the reconstruction phase after the war. SATO was also actively involved in developing housing estate neighbourhoods in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. Since 2015, the largest shareholder of SATO is Fastighets AB Balder, a Swedish housing investment company (webpage of Sato, Citation2021). VVO (Valtakunnallinen vuokratalo-osuuskunta, the national rental housing cooperative) was founded in 1969 to provide housing for people moving to cities in search of work. The main owner at the time was a development company called Haka Oy. Haka Oy on the other hand was owned by different unions, particularly that of the building sector, and by pension funds. VVO was listed on the stockmarket of Helsinki in 2018, under the new name Kojamo (webpage of Kojamo, Citation2021).

10 Including right of occupancy flats.

11 Social housing in is defined as subsidized housing produced by limited-profit housing associations or council housing. Limited-profit housing associations also construct new units without subsidies. These are included in “other housing”, as price levels usually correspond more closely to private market housing.

12 Personal correspondence with the Head of Housing Policy at the City of Helsinki, 17.3.2017.

13 GBV (Citation2016: 8) estimates that between 24% and 33% of all limited-profit housing units in Vienna that are currently owned by limited-profit housing associations are equipped with a (current or upcoming) right to buy and may be bought by the tenants at some point.

References

- Aalbers, M. (2012) Privatisation of social housing, in, Encyclopedia of Housing and Home, pp. 433–438. (Amsterdam: Elsevier).

- Aalbers, M. B. & Holm, A. (2008) Privatising social housing in Europe: the cases of Amsterdam and Berlin, in: K. Adelhof, B. Glock, J. Lossau, & M. Schulz (Eds.) Urban trends in Berlin and Amsterdam, pp. 12–23. (Berliner geographische Arbeiten; No. 110). Geographisches Institut der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

- ARA. (2013/2015) Housing finance loans. Available at https://www.ara.fi/en-US/Housing_finance/Loans. (accessed 3 March 2021).

- ARA. (2019) ARA-asuntokannan kehitys 2000-luvulla. Selvitys 1/2019. Available at https://www.ara.fi/Tietopankki. (accessed 3 March 2021).

- ARA. (2021) Asukasvalinta. Available at https://www.ara.fi/Asukasvalinta (accessed 3 March 2021).

- Arbeiterkammer Wien. (2022) Genossenschaftswohnungen mit Kaufoption. Available at https://wien.arbeiterkammer.at/beratung/Wohnen/Wohnen_im_Eigentum/Genossenschaftswohnungen_mit_Kaufoption.html (accessed 1 March 2022)

- Asumisen ja siihen liittyvän maankäytön toteutusohjelma. (2020) City of Helsinki. Available at https://dev.hel.fi/paatokset/media/att/57/575b338de14f698c1228a244265057ed428f7ed4.pdf. (accessed 3. March 2021).

- Bengtsson, B., Ruonavaara, H. & Sørvoll, J. (2017) Home ownership, housing policy and path dependence in Finland, Norway and Sweden, in: Dewilde C, Ronald R (Eds.) Housing Wealth and Welfare, pp. 60–84. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Blackwell, T. & Bengtsson, B. (2021) The resilience of social housing in the United Kingdom, Sweden and Denmark. How institutions matter, Housing Studies, online first, pp. 1–21.

- Blackwell, T. & Kohl, S. (2018) Urban heritages: How history and housing finance matter to housing form and homeownership rates, Urban Studies, 55, pp. 3669–3688.

- Byrne, M. & Norris, M. (2022) Housing market financialization, neoliberalism and everyday retrenchment of social housing, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 54, pp. 182–198.

- Christophers, B. (2013) A monstrous hybrid: the political economy of housing in early twenty-first century Sweden, New Political Economy, 18, pp. 885–911.

- City of Helsinki. (2021). Hakijat ja valitut. Available at https://asuminenhelsingissa.fi/fi/content/hakijat-ja-valitut (accessed 13 December 2021).

- Czischke, D. (2014) Social housing and european community competition law, in: Kathleen Scanlon, Christine Whitehead und Melissa Fernández Arrigoitia (Eds) Social Housing in Europe, pp. 333–346 (Hoboken: Wiley (Real Estate Issues)).

- Elsinga, M. & Lind, H. (2013) The effect of EU-Legislation on rental systems in Sweden and The Netherlands, Housing Studies, 28, pp. 960–970.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (London: Polity).

- EU-SILC (2011) Eurostat, EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditionson income and living conditions 2011.

- EU-SILC (2019) Eurostat, EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditionson income and living conditions 2019.

- Forrest, R. & Murie, A. (1988) Selling the Welfare State: The Privatisation of Public Housing (London: Routledge).

- Hankonen, J. (1994). Lähiöt ja tehokkuuden yhteiskunta Tampere: Otatieto Oy, Gaudeamus & TTKK Arkkitehtuurin osasto.

- Österreichischer Verband gemeinnütziger Bauträger (GBV). (2016) Jahresstatistik (Wien: Eigenverlag).

- Haila, A. & Le Galès, P. (2004) The coming of age of metropolitan governance in Helsinki? In: Heinelt, H., Kübler, D. (Eds.), Metropolitan Governance in the 21st Century, pp. 117–132 (London: Routledge).

- Hansson, A. & Lundgren, B. (2019) Defining social housing: a discussion on the suitable criteria, Housing, Theory and Society, 36, pp. 149–166.

- Harloe, M. (1995) The People’s Home?: Social Rented Housing in Europe and America (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons).

- Hatz, G., Kohlbacher, J. & Reeger, U. (2016) Socio-economic segregation in Vienna: A social-oriented approach to urban planning and housing. In Tiit Tammaru, Szymon Marcińczak ,Maarten van Ham, & Sako Musterd (Eds.), Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West, pp. 80–109. (London/New York, NY: Routledge).

- Helsingin kaupunginkanslia. (2021) Asuminen Helsingissä. Available at https://asuminenhelsingissa.fi/fi/content/asuntotuotanto (accessed 3 March 2021).

- Helsingin seudun aluesarjat. (2021) Hallintaperusteeet. Available at http://www.aluesarjat.fi (accessed 3 March 2021).

- Hirvonen, J. (2010) Tulorajat poistuivat – muuttuiko mikään? Tilastoselvitys ARA-vuokra-asuntojen hakijoista ja asukasvalinnoista (Income limits removed – did anything change? Statistical report on ARA rental housing applicants and resident choices). Suomen Ympäristö 13/10.

- Hirvonen, J. (2021) Tulotaso Helsingin asuntokannan eri osissa. Kvartti. Available at https://www.kvartti.fi/fi/artikkelit/tulotaso-helsingin-asuntokannan-eri-osissa. (accessed 6 September 2021).

- Hochstenbach, C. (2017) Stete-led gentrification and the changing geography of market-oriented housing policies, Housing Theory and Society, 34, pp. 399–419.

- Housing Europe. (2019) The state of housing in the EU 2019.

- Jacobs, K. (2019) Neo-Liberal Housing Policy. An International Perspective, 1st ed. (New York, Routledge).

- Hurmeranta, R. (2020) Kelan asumistukitilasto 2019. Official Statistics of Finland. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/319888/Kelan_asumistukitilasto_2019.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y (accessed 15 Jube 2022).

- Hyötylainen, M. (2020) “Not for normal people”: the specialization of social rental housing in Finland, ACME, 19, pp. 545–566.

- Juntto, A. (1990) Asuntokysymys Suomessa. Topeliuksesta tulopolitiikkaan, p. 412 (Helsingfors: Asuntohallitus).

- Kadi, J. & Ronald, R. (2014) Market-based housing reforms and the ‘right to the city’: the variegated experiences of New York, amsterdam and Tokyo, International Journal of Housing Policy, 14, pp. 268–292.

- Kadi, J. (2015) Recommodifying housing in formerly “red” Vienna, Housing, Theory and Society, 32, pp. 247–265.

- Kadi, J., Banabak, S. & Plank, L. (2020) Die Rückkehr der Wohnungsfrage. Beigewum. http://www.beigewum.at/wp-content/uploads/Factsheet-Wohnen.pdf

- Kadi, J., Vollmer, L. & Stein, S. (2021) Post-neoliberal housing policy? Disentangling recent reforms in New York, Berlin, And Vienna, European Urban and Regional Studies, 28, pp. 353–374.

- Kemeny, J. (1995) From Public Housing to the Social Market. Rental Policy Strategies in Comparative Perspective (London/New York: Routledge).

- Kohl, S. & Sørvoll, J. (2021) Varieties of social democracy and cooperativism: Explaining the historical divergence between housing regimes in nordic and German-Speaking countries, Social Science History, 45, pp. 561–587.

- Kontrollamt, S. W. (2002) Stadt Wien-Wiener Wohnen. Verkauf von städtischen Wohnhäusern. (Wien: Kontrollamt der Stadt Wien).

- Korab, R., Romm, T. & Schönfeld, A. (2010) Einfach Sozialer Wohnbau. Aktuelle Herausforderungen an den geförderten Wiener Wohnbau und Eckpfeiler eines Programms ‘einfach sozialer Wohnbau’. http://www.wohnbauforschung.at/Downloads/ESW_Endbericht_100903_ver6_1MB.pdf (accessed 4 September 2021).

- Lawson, J. (2010) Path dependency and emergent relations: Explaining the different role of limited profit housing in the dynamic urban regimes of vienna and Zurich, Housing, Theory and Society, 27, pp. 204–220.

- Lilius, J. & Hirvonen, J. (2021) The changing position of housing estate neighbourhoods in the helsinki metropolitan area, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment.

- Matznetter, W. & Mundt, A. (2012) Housing and welfare regimes, in: David Clapham (Eds) The SAGE Handbook of Housing Studies, pp. 274–294 (Los Angeles, SAGE).

- Matznetter, W. (2020) How and where non-profit rental markets survive – a reply to stephens, Housing, Theory and Society, 37, pp. 562–566.

- Ministry of Environment. (2021a) Right of occupancy, 2. Available at https://ym.fi/en/right-of-occupancy-housing (accessed 3 July 2021).

- Ministry of Environment. (2021b) Land use, housing and transport agreements, 2. Available at https://ym.fi/en/agreements-on-land-use-housing-and-transport (accessed 3 March 2021).

- Mundt, A. (2008) Privatisierung von gebundenem sozialem Wohnraum. In: Lugger, K. & Holoubek, M. (Eds) Die österreichische Wohnungsgemeinnützigkeit – ein europäisches Erfolgsmodell (Wien: Manzsche Verlags- und Universitätsbuchhandlung).

- Mundt, A. & Amann, W. (2010) Idicators of an Integrated Rental Market in Austria. Available at http://iibw.at/documents/2010%20(Art.)%20Amann_Mundt.%20Integrated%20Rental%20Market%20Austria%20(HFI).pdf (accessed 16 February 2022).

- Mundt, A. (2018) Privileged but challenged: the state of social housing in Austria in 2018, Critical Housing Analysis, 5, pp. 12–25.

- Musterd, S. (2014) Public housing for whom? Experiences in an era of mature Neo-Liberalism: The Netherlands and amsterdam, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 467–484.

- Novy, A., Redak, V., Jäger, J. & Hamedinger, A. (2001) The end of red vienna: Recent ruptures and continuities in urban governance, European Urban and Regional Studies, 8, pp. 131–144.

- Pittini, A., Turnbull, D. & Yordanova, D. (2021) Cost-based social rental housing in Europe, Technical report, Available at: https://www.housingeurope.eu/resource-1651/cost-based-social-rental-housing-in-europe (accessed 16 July 2022).

- Poggio, T. & Whitehead, C. (2017) Social housing in Europe: legacies, new trends and the crisis, Critical Housing Analysis, 4, pp. 1–10.

- Programme of Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government. (2019) Available at https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/marin/government-programme (accessed 5 May 2021).

- Ronald, R. (2013) Housing and welfare in Western Europe: Transformations and challenges for the social rented sector, LHI Journal of Land, Housing, and Urban Affairs, 4, pp. 1–13.

- Ruonavaara, H. (1993) Types and forms of housing tenure: towards solving the comparison/translation problem, Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 10, pp. 3–20.

- Ruonavaara, H. (2006) Finland – Den dualistiska bostadsregimen och jakten på det sociala. In Bengtson, B. (Ed). Varför så olika? Nordisk bostadspolitik i jämförande ljus, pp. 219–278 (Malmö: Ègalite).

- Ruonavaara, H. (2017) Retrenchment and social housing: the case of Finland, Critical Housing Analysis, 4, pp. 8–18.

- Scanlon, K. & Whitehead, C. (2014) Social Housing in Europe. Fernández Arrigoitia, M. (Eds) (Hoboken: Wiley (Real Estate Issues).

- Wien, S. t. (2019) Jede zweite geförderte Wohnung künftig SMART [Every second subsidized housing to be a SMART unit]. Available at: https://www.wien.gv.at/bauen-wohnen/smart.html (accessed 4 September 2021).

- Statistik Austria. (2013) Wohnen 2020, Zahlen, Daten Und Indikatoren Der Wohnstatistik.

- Statistik Austria. (2021) Wohnen 2020, Zahlen, Daten Und Indikatoren Der Wohnstatistik.

- Statistics Finland. (2021) Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Dwellings and housing conditions [e-publication]. ISSN=1798-6761. Overview 2020, 2. Household-dwelling units and housing conditions 2020. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 14.1.2022].

- Stephens, M. (2020) How housing systems are changing and why: a critique of kemeny’s, Theory of Housing Regimes, 37, pp. 521–547.

- Strategic Program of Prime Minister Juha Sipilä’s Government. (2015) Available at https://valtioneuvosto.fi/documents/10184/1427398/Ratkaisujen+Suomi_EN_YHDISTETTY_netti.pdf/8d2e1a66-e24a-4073-8303-ee3127fbfcac/Ratkaisujen+Suomi_EN_YHDISTETTY_netti.pdf (accessed 3 March 2021)

- Streimelweger, A. (2014) Die europäische union und der soziale wohnbau – ein spannungsverhältnis, in: Kurswechsel, 3, pp. 29–39.

- Tockner, L. (2017) Mieten in österreich und wien, 2008 bis 2016.

- Tunstall, B. (2021) The deresidualisation of social housing in England: change in the relative income, employment status and social class of social housing tenants since the 1990s, Housing Studies, pp. 1–21.

- Vihavainen, M. & Kuparinen, V. (2006) Asuminen Helsingissä 1950–2004. HELSINGIN KAUPUNGIN TIETOKESKUKSEN verkkojulkaisuja. Available at https://www.hel.fi/hel2/tietokeskus/julkaisut/pdf/06_11_27_vihavainen_vj34.pdf (accessed 3 March 2021).

- Vuokranmääritys Hekassa. (2017) Available at https://www.hekaoy.fi/sites/default/files/inline-files/Hekan_vuokrantasausmalli.pdf (acessed 22 August 2019).

- Vuori, P. & Rauniomaa, I. (2018) Helsingin kaupungin vuokra-asunnoissa asuvien tulotaso. Available at https://www.kvartti.fi/fi/artikkelit/helsingin-kaupungin-vuokra-asunnoissa-asuvien-tulotaso. (accessed 5 February 2021).

- Whitehead, C. M. (2003) Restructuring social housing systems, in: Housing and social change. pp. 58–80. Routledge: London/New York.

- WIFO. (2012) Instrumente und Wirkungen der österreichischen Wohnungspolitik [Instruments and Impacts of Austrian Housing Policies]. (Wien: WIFO Wien).

- Wimark, T., Andersson, E. & Malmberg, B. (2020) Tenure type landscapes and housing market change: a geographical perspective on neo-liberalization in Sweden, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 214–237.

- Wohnen, W. (2019) Gemeindebau Neu. Available at: https://www.wienerwohnen.at/gemeindebauneu.html (accessed 4 September 2021).

- Wieser, R. & Mundt, A. (2014) Housing subsidies and taxation in six EU countries, Journal of European Real Estate Research, 7, pp. 248–269.

- Webpage of Kojamo. (2021) Available at https://www.kojamo.fi (accessed 5 February 2021).

- Webpage of Sato. (2021) Available at https://www.sato.fi/fi (accessed 5 February 2021).