Abstract

Against the background of price increases on the one hand and strong tenement regulations in Vienna’s historic housing stock on the other, this article analyses the actors and strategies of commodification. Following a mixed-methods approach, this case study analyses 90 historic tenement buildings in nine neighbourhoods. Our analysis reveals the increasing relevance of institutional actors as (co-)owners, which goes hand in hand with declining holding periods. As local actors are highly diverse, we have identified five types of actors and four commodification strategies, pointing towards a spatially differentiated division of labour. This actor constellation, dominated by micro actors, suggests that the specific situation and regulation of a market brings different types of actors to the fore. Most of the identified actors, and particularly the funding of their projects, have no relation to financial markets and sources; from this perspective, the concept of commodification provides greater insight into the dynamic of this specific housing market segment than the lens of financialisation does.

1. Introduction

Due to low interest rates and increasing uncertainty regarding financial market stability, investment in rental housing has been identified as a lucrative asset and means of value storage (Aalbers, Citation2019; Fields & Uffer, Citation2016; Rogers & Koh, Citation2017). Against this background, institutional investors as well as households apply various exploitation strategies, turning housing into a profitable commodity, which further speeds up urban housing price dynamics. For this transformation of housing, the concept of financialisation has become the most relevant explanatory frame, implying an increasing dominance of financial actors, markets, practices, measurements, and narratives (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2016; Theurillat et al., Citation2016). Considering existing criticism of this approach (Poovey, Citation2015), we adopted the idea of Jacobs & Manzi (Citation2020), who suggest dividing financialisation into various pre- and sub-processes. Accordingly, we focus on commodification as a process that is principally related to the physical structure of the built environment and that functions as a prerequisite for financialisation. We define this as a process that turns a housing market segment into a commodity. Thus, the social function of a house as a dwelling becomes overlapped with its function as a tradable good or as a safe deposit.

In our empirical analysis, we follow the path of commodification within the historic housing stock of Vienna and enquire after those actors and landlords as well as their strategies that turn a highly regulated tenement market, and (similar to Brousseau, Citation2015 or Teresa, Citation2019) as such an incompletely commodified housing sector, into a fully commodified one. Vienna presents an interesting case for several reasons: Firstly, besides containing a huge social housing stock (42 percent of apartments; Matznetter, Citation2019), Vienna is also famous for its historic housing stock, which provides affordable rents due to a strict tenement regulation. This regulation, in combination with a weak demand, caused this market segment to remain non-commodified for decades after World War II, and as such to have been unattractive for developers (Lichtenberger, Citation1993; Matznetter, Citation2019). Secondly, alongside the take-off in prices since the early 2000s and further in the aftermath of the subsequent financial crisis (OeNB, Citation2021), the highly regulated historic housing stock came in the focus of developers. This implied the commodification and the erosion of this housing market segment. Finally, focussing on commodification as a preliminary process of financialisation makes sense for Vienna, as Austria is dominated by a traditional banking system, in which the financial market (Lunde & Whitehead, Citation2016) only plays a small role.

The main aim of this paper is twofold: firstly, we intend to analyze the actors and their strategies that drive the commodification of a rent-regulated historic housing stock, which sheds light on a process that has not been considered until now. Secondly, beyond the case of Vienna, this paper discusses the analytical value of the concept of commodification, regardless of whether the relevant actors are financialized.

The paper is structured as follows: first, we provide an overview of actors and their commodification practices in the context of the financialisation of housing (Section 2). Secondly, we discuss the structure and relevance of Vienna’s historic housing market (Section 3). After describing our methods and the identification of our selected neighbourhoods (Section 4), we provide an overview (Section 5) and a discussion of the implications (Section 6) of our results.

2. Financialisation and commodification of housing

2.1. Concepts and delimitations

Regarding the shift of housing towards a value-storage and asset class, the concept of financialisation has become the most relevant explanatory frame in urban research (Aalbers, Citation2019). According to this model, the financialisation of housing involves the increasing relevance of financialized actors as well as the transfer of the logic and strategies of financial investors to urban housing markets (Theurillat et al., Citation2016). It furthermore implies an increasing dominance of financial measurements and narratives (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2016). However, the concept of financialisation regarding housing markets has evoked criticism, which is aimed at two aspects: Firstly, at the conceptual scale, its numerous and vague definitions keep the concept unclear (French et al., Citation2011; Poovey, Citation2015). Christophers (Citation2015) criticizes ‘financialisation-as-concept’, pointing out that using it as the basis of conceptual generalizations is no novelty. Some studies even rely on theoretical concepts that have been developed decades before, e.g. Arrighi’s or Braudel’s theoretical analyses of finance capital (Arrighi, Citation1994). Secondly, related to this conceptual fuzziness, there is a lack particularly of quantitative empirical analysis (see the critique in Romainville, Citation2017). Due to these conceptual limitations, the narrative of financialisation seems well established, while the methodology of this phenomenon appears less clearly developed.

To overcome these limitations and to ease empirical approaches in this field, several authors suggest a more distinct identification of processes and actors of the financialisation of housing (Christophers, Citation2015; Romainville, Citation2017; Smet et al., Citation2015). To raise the utility of the financialisation concept for housing research, Jacobs & Manzi (Citation2020) distinguish three types of processes and practices that are brought together under the ‘umbrella’ of financialisation: firstly, they mention globalization processes, focussing on the economic and political frame within which financialisation processes take place. Secondly, there is neoliberalism as the ideological narrative that justifies and explains the expansion of a financial logic to housing, and finally, commodification and marketization must be mentioned as the concrete practices and strategies through which the logic of financial capital paves its way onto housing markets. In the following, we discuss the concept of commodification as a preliminary process that is more closely related to the built environment and the housing stock than the other two processes of financialisation are.

In general, the term commodification describes the process in which the economic value of a commodity increasingly begins to dominate its other uses. In the context of housing, this concept can be traced back to the classic school of Marxist urbanism (Forrest & Williams, Citation1984; Harvey, Citation1982). Thus, for the question of land usage as well as housing, the conflict between utility value and exchange value has been under discussion since the 19th century (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016). In this context, it ‘means that a structure’s function as real estate takes precedence over its usefulness as a place to live’ (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016, p. 14). Expanding this process, the ‘hyper-commodification of housing’ describes the commodification of the housing system beyond the dwelling, including, for instance, legal functions and changes (e.g. deregulation policies) as well as housing provision (labour and machines; Gillon, Citation2018). This often goes hand in hand with an internationalization of real-estate markets. Further characteristics of the commodification of housing include the fact that residential buildings are considered a fungible, tradable asset (Heeg, Citation2013). Additionally, changes in the ownership structure, coupled with a decrease in holding time, point to commodification. If these new owners were financial actors, this would imply financialisation (Wijburg et al., Citation2018).

The concepts of financialisation and commodification are interwoven, which renders a clear distinction rather challenging. The main difference lies in the fact that the designation ‘commodification’ can be used without any reference to the financial market or financial capital. Further, the concept of commodified housing focuses on the built environment of the housing stock as well as on the social implication of its transformation towards a commodity. In contrast, the financialisation of housing emphasizes the actors and organizations such as financial institutions, which are only indirectly related to the physical housing stock, as Rogers et al. (Citation2018) state: ‘Indeed, key financialisation actors may never see the physical dwellings that underwrite their profits, although […] their actions can have dire consequence for those who occupy these dwellings’ (Rogers et al. (Citation2018), p. 435). As such, the financialisation of housing appears as a superordinate and downstream process, regarding the formation of financial products or services that enable actors to direct financial capital into a housing stock in innovative ways (Byrne & Norris, Citation2022; Waldron, Citation2018). In contrast, commodification also comprises the other steps of the value chain and the related regulative frame beyond the issue of financing, and functions as a preliminary process that turns housing into a marketable commodity, potentially paving the way for financial actors.

2.2. Actors and strategies of the commodification of housing

Commodification of housing is driven by various institutions, actors and strategies. Here, we distinguish between two scales: firstly, macroeconomic transformation on the regulative or political scale, and secondly, strategies of housing companies and of households on the individual scale.

On the regulative or political scale, the transformation of former communist countries and the privatization of the large socialist housing stock since the early 1990s represent an outstanding form of commodification. This turned millions of apartments in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe into a commodity, causing urban development conflicts and social distortions (cf., e.g. Csizmady, Citation2020; Musil, Citation1995; Sykora, Citation1995; Vilenica et al., Citation2021). More recently, housing reforms carried out in China represent a radical form of commodification, involving the housing allocation by state-owned enterprises and market-oriented reforms, which triggered the enormous expansion of a commodified housing stock (Chiu, Citation2001; Wu, Citation2015). To a comparably lesser extent, privatization policies regarding public housing as well as the promotion of ownership in Western countries turned housing into a commodity. Examples are the ‘help-to-buy’-policy in the UK (Fenton et al., Citation2013; Hamnett & Randolph, Citation1984), the privatization of communal social housing in Germany (Kaufmann, Citation2013), or the deregulation of regulated housing market segments in US-cities (e.g. Brousseau, Citation2015). Despite all differences, these policies are driven by the idea that marketization improves the allocation of housing, promotes home-ownership, and turns housing into a mobile, tradable commodity.

On the scale of actors, the supply side of housing markets shows a broad variety of actors, the appearance of whom transforms a non-commodified market segment into a commodified one; for instance, commercial mediator agencies that provide commercial temporary housing (Debrunner & Gerber, Citation2021), short-term rentals via Airbnb (Gutiérrez & Domènech, Citation2020; Segú, Citation2018), or providers of exclusive student housing (Kinton et al., Citation2018; Smith & Hubbard, Citation2014). However, real-estate developers are seen in the first place as drivers of commodification, regardless of whether they are financialized and as such related to financial markets and resources, or not (Fields & Uffer, Citation2016; Wijburg et al., Citation2018). Several typologies have been established to deal with this broad variety. Ruming (Citation2010) for instance differentiated developers by their size, whereby the huge number of small and medium developers rely on other methods (mobilising informal networks) compared to large firms (economic power in formalized processes). Romainville (Citation2017) distinguishes between developers according to their link towards financial markets. She demonstrates in her quantitative analysis that financialized developers are larger and more internationalized than non-financialized developers. They also vary regarding the size and location of projects in urban space. Additionally, McGaffin et al. (Citation2019) distinguish small-scale developers and their strategies with respect to the ownership of the property. Altogether, the size of developers, their link to financial sources, and their integration in (in)formal networks have an impact on their strategies and output. These factors also determine whether the commodification of housing turns into financialisation.

Beyond developers, the strategies of land and property owners are also relevant for the commodification of housing. Here, Haila (Citation1991) provides a conceptual typology in which land/property owners are distinguished according to the time horizon of investment (short/long term) and by the aim of investment (exchange/use). In her taxonomy, the agent ‘dealer’ (short term, exchange) seems to represent the strategy of commodification, whereas the agent ‘speculator’ (long term, exchange) represents financialisation. More recently, Paccoud et al. (Citation2022) provide a new perspective, highlighting that interconnected developers and property or landowners drive a specific accumulation strategy and ‘… point to the need to combine the study of landowner and developer strategies in order to better grasp the mechanisms through which housing is produced’ (Paccoud et al., Citation2022, p. 7). As such, property ownership and its changes seem a relevant driver for turning housing into a commodity. More generally, the structure of ownership and changes in ownership, including the rise of institutional investors or changes to private homeownership for private rental (Aalbers et al., Citation2021) further contribute to commodification.

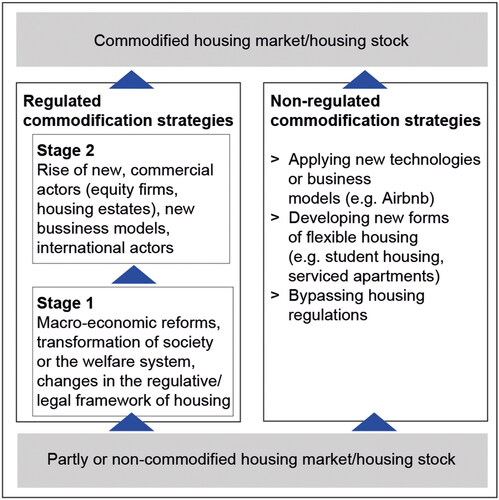

The strategies of commodification can be differentiated according to whether they rely on a change of the regulative frame or whether they take place within an existing regulative frame (). In the first case, political or regulative changes are a prerequisite for turning housing into a commodity. This of course is the case in situations of macroeconomic changes, such as those in post-socialist European countries or in China, as well as during the transformation of welfare regimes (Matznetter, Citation2020). Furthermore, the regulative frame changes along with changes in housing policy, as was the case with the privatization of social housing in Germany and the UK, or when blurring of housing regulations takes place. As such, Debrunner & Gerber (Citation2021) demonstrate that commodification must be divided in two stages: firstly, a transformation of the regulative framework takes place, upon which, secondly, the application of a business model that raises profits and commodifies an existing market segment (in the case of temporary housing) or the total market (in the case of post-socialist housing transformation) follows. This is the case for various forms of commodification, but not for all. The second case comprises commodification strategies of actors that do not require regulative changes. Here, commodification takes place within the existing regulation or through bypassing such regulations. Examples of such cases include short-term rentals via Airbnb (Gutiérrez & Domènech, Citation2020; Segú, Citation2018), the marketization of the student housing market (Smith & Hubbard, Citation2014), or strategies towards bypassing existing regulations on the rental housing market to develop these ‘undervalued assets’, in particular in a context of increasing housing prices (Teresa, Citation2019).

Below, we discuss four strategies of developers that are related to the latter case: the physical or legal conversion of a rent-regulated housing stock, motivated by the wish to circumvent existing regulations. To gain greater insight into the commodification of the rent-regulated historic housing market of Vienna, we analyze those actors that drive this process. Furthermore, we enquire after their strategies and finally, we enquire whether they are connected to the financial market. As such, we intend to discuss the following research questions: (1) Do the ownership structure and its change over time point to a commodification of housing? (2) Who are the actors who bring about this commodification, and (3) which strategies do they employ?

3. The Gründerzeitstadt – the rent-regulated historic housing stock in Vienna

Vienna’s historic housing stock is the outcome of the rapid urbanization and industrialization that have taken place between 1848 and 1918, a historic period described as the Gründerzeit. In this period, Vienna’s population grew from about 0.5 million to more than 2.2 million (Weigl, Citation2003). This period of urbanization was shaped by an enormous degree of construction activity, whereby the state provided technical and social infrastructures (water supplies, public spaces, transport, schools, …), while housing provision was determined by the free market, only regulated by building legislation (Bobek & Lichtenberger, Citation1966). At the time, legislation stipulated a strict block-grid as well as a construction height that allowed for five floors in the inner city and three floors in the peripheral city districts. In the era of industrialization, the housing situation was characterized by enormous social contrasts: one could find bourgeois tenement houses with large apartments close to the city centre on the one hand, opposed to working-class houses on the other, dominated by two- or three-roomed apartments, with ablutions provided only on the corridors. Hidden behind representative facades, overcrowded apartments producing poor living standards were the housing situation for the working class in Vienna’s Gründerzeit, due to high housing costs.

3.1. Urbanistic qualities and tenement regulations

Seen from a present-day perspective, the outcome of the Gründerzeit is a compact urban zone, which encloses the historic city centre in a radius of 3 to 5 kilometres, which is described as the Gründerzeit city. This area comprises various qualities, which are the outcome of an economic, technical, and planning framework that does not exist anymore. From the perspective of architecture, brick is a ‘soft’ building material that displays a high adaptability to changing social and technical requirements (City of Vienna/MA21, Citation2018). Furthermore, rooms generally are between 3.2 and 4 metres high and even beyond, which is today considered as representative of an especial quality of living (room height in newly constructed buildings varies between 2.4 and 2.6 meters). Beyond the single building, the Gründerzeit city displays high functional diversity, which represents the vital urbanity of the European city (Siebel, Citation2004) and correlates with modern concepts of urban development, such as the ‘compact city’ or the ‘city of short distances’ (Glaser et al., Citation2013). Even if the potentials of the Gründerzeitstadt are very uneven, its qualities are in high demand – for households and developers alike.

Beyond these architectural and urbanistic qualities, the housing-policy implications of this historic housing stock are even more relevant, as the rents are highly regulated by a specific law (Mietrechtsgesetz, MRG), in contrast to the non-regulated tenement housing stock, which comprises buildings constructed after 1945 (Matznetter, Citation2019). The MRG regulates the level of rents, the current basic value of which is about 6.15 €/m2 in Vienna, to which surcharges for the location and quality features might be added. In total, MRG rents average at around 9.0 €/m2, compared to 12.5 €/m2 on the non-regulated rental market (Statistik Austria, Citation2021). Furthermore, the increase of MRG rents are regulated likewise and only coupled to the inflation rate, so that tenants are strongly protected.Footnote1 This MRG-regulated market segment covers about 220.000 apartments, which in turn comprises about 22% of the total housing stock in Vienna, but 65% percent of Vienna’s private rental housing stock (Statistik Austria, Citation2021). Due to the combination of regulated and therefore affordable rent prices and a private, low-threshold access to housing, the historic housing stock often provides the first access to the housing market in Vienna for migrants – e.g. for students from Austrian regions, guest workers from former Yugoslavia, or EU-migrants today (Kohlbacher & Reeger, Citation2006). As such, the Gründerzeit city is characterized by a high degree of social diversity and represents Vienna’s role as an arrival city.

3.2. Bypassing existing tenement regulations

These historic tenement buildings – also called Zinshäuser in Vienna – displayed a very low profitability for decades, and public subsidies were necessary to avoid urban decline in this non-commodified housing market segment. However, during the 2000s, the market situation changed fundamentally. Between 2007 and 2019, alongside the increasing housing prices in Vienna, a gap rose between regulated rent prices and purchase prices. While the MRG-regulated basic rental prices only experienced an index adjustment (+20.5%), the general property price index for resales more than doubled in the same period (+111%, OeNB, Citation2021). The concept ‘rent gap’ describes a gap between realized and optimal rents (after renovation), which explains the where and when of gentrification (Porter, Citation2010; Smith, Citation1987). In the context of Vienna’s historic housing stock, the ‘value gap’ (defined as a gap between rental and ownership price dynamics; see Clark, Citation1992), describes the mechanism of commodification more adequately: the gap between MRG-regulated rents and apartment selling prices triggers the circumvention of MRG-rents, which has become a highly profitable business.

This circumvention could take place in two ways (Musil et al., Citation2022, ): Firstly, by the demolition of existing objects and the construction of new residential buildings that are not MRG-regulated and furthermore contain more apartments due to lower room heights and higher building heights (physical conversion). Secondly, by the legal (or tenure) conversion of existing objects into condominium houses, in which all apartments can be sold individually on the ownership market. Additionally, the roof trusses of the converted houses have often been converted into high-priced penthouses. These two forms of conversions as means of bypassing regulations (whereby the second accounts for about four fifths of cases) turned a regulated, non-commodified into a non-regulated, commodified housing stock. The Zinshäuser in Vienna have become a highly profitable ‘money machine’ and as such a strongly desired object for developers. In the following, we enquire after these actors and their commodification strategies.

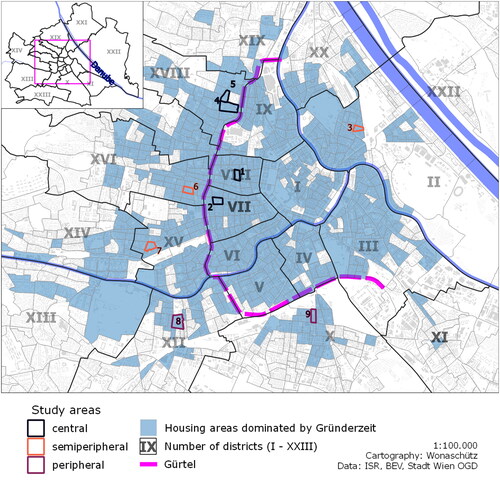

4. Methods: a case study on housing commodification in selected neighbourhoods in Vienna

In this case study, we have analyzed the actors of commodification and their strategies in selected neighbourhoods. To identify relevant case studies, we first have analyzed the recent conversion of Zinshäuser throughout the city quantitatively. This analysis comprises the conversions between 2007 (first year of digital accessibility of the land register) and 2019, which covers the recent house-price boom in Vienna, in the aftermath of the euro crisis (Musil et al., Citation2022; OeNB, Citation2021). Based on this quantitative database, we have identified hotspots of Zinshaus conversion in Vienna. The neighbourhoods were selected on the scale of census tracts [Zählsprengel], according to two criteria. Firstly, by their location within a significant cluster of transformed Zinshäuser (based on a DBSCAN algorithm, answering to two criteria: maximum distance of 300 m between transformed Zinshäuser, minimum of ten transformed buildings; Ester et al., Citation1996; Musil et al., Citation2022). Secondly, they display an above-average dynamic, measured by the lot size of converted Zinshäuser within each census tract. The pattern of selected case areas is visualized in . The distribution of these nine census tracts represents a broad range within Vienna’s Gründerzeitstadt. Two districts are inside the Gürtel, in upper-middleclass neighbourhoods (1 and 2), one in the second district (3), and a further six are situated outside the Gürtel: two in the upper-middleclass area around Kutschkermarkt (4 and 5), and four in traditional working-class areas (Neulerchenfeld: 6; Wieningerplatz: 7; Meidlinger Haupstraße: 8; Laxenburger Straße: 9).

Figure 3. Selected case areas, hotspots of Zinshaus conversion within the historic housing stock (source: own data, own compiliation).

Within these nine neighbourhoods, ten Zinshäuser have been selected in each case by random principle, so that 90 buildings constituted the sample of our analysis. From this sample, 56 buildings have been transformed by legal conversion, four by physical conversion (demolition/new construction), and 30 buildings had not been converted within the timespan of our interest (2007 to 2019). As demolitions are more sparsely distributed than legal conversions, they are underrepresented in our sample. For each building, we have conducted a qualitative analysis of the historic ownership structure, an analysis of the actors of commodification (which may or may not lead to legal/physical conversion), and an analysis of the structural condition of the dwelling.

Among our various data sources, the first and most relevant is the Austrian land register, which provides data regarding the changes of the ownership structure during the last century, since the 1920s (BEV, n.d.). This data source allowed us to obtain historic information for our sample of 90 selected Zinshäuser, regarding the number and the forms of ownership transfer, the holding time, and the changes in ownership types (private households or companies) until the conversion of the building or, if no conversion took place, until the present time. Within this sample, we identified 44 firms as property owners who had precipitated the legal conversion of the building. Based on the company register and via desk research, we analyzed these companies regarding their size, shares in other companies, legal form, business areas, and activities on the Viennese housing market. To evaluate the structural condition of the 86 buildings (new constructions were not considered) and the extent and quality of reconstruction work, we conducted on-site visits. Finally, we conducted ten expert interviews with developers from the 44 identified firms. These structured interviews were conducted between March and July 2021, all except one (which was done through Skype) face-to-face in the offices of the developers. All interviews were transcribed and evaluated through content analysis. By using company data combined with the interviews, we developed a typology of the actors and we further differentiated strategies of commodification.

5. Results: shift in ownership, actors and strategies of commodification

In this section, we present the results of our qualitative analysis in three steps, based on the sample of 90 Zinshäuser. Firstly, we analyze the changing ownership structures, in particular, distinguishing between personal and institutional owners, and their implication for the holding time of the properties; secondly, we differentiate the actors of commodification, and finally we investigate their strategies towards circumvention of the regulation of this housing stock.

5.1. Shift in ownership: rise of legal persons

Changes within the ownership of properties are a core characteristic of the commodification of housing (Aalbers et al., Citation2021; Haila, Citation1991; Heeg, Citation2013; Wijburg et al., Citation2018). Within the sample of 90 Zinshäuser, we identified a clear, elementary shift within the ownership structure. During the period of analysis (2007 to 2019), the share of private persons as property-owners had declined, whereby legal persons (companies) dominated at around 90% on the buyers’ side. This is an extremely high value, particularly in a historical comparison: in the decades before 1982, the share of non-private buyers of Zinshäuser lay at only about 12% (Kaufmann & Hartmann, Citation1984). The recent, massive changes in the ownership structure had implications for the role of housing as a commodity, which becomes apparent in two aspects.

Firstly, this shift was accompanied by a noticeable decline of the share of property owners that lived on the premises of their own property: in 2007, 18 of the 90 properties of our sample – about one fifth – also held the dwelling of at least one owner. This number had declined to three of the 90 properties in 2019. In contrast, during the 1980s and the decade before, the share of owner-used properties was about 50% (Kaufmann & Hartmann, Citation1984).

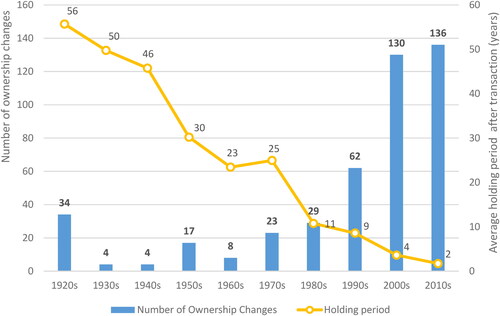

Secondly, the rapid shift in ownership structures goes along with a declining holding duration, which likewise emphasizes the transformation of housing into a tradable commodity (Heeg, Citation2013). For our sample, the analysis of the historic land register (since the 1920s) confirms a clear trend towards Zinshäuser increasingly becoming a commodity. Between 1920s and 1970s, the number of transactions per decade displays a very low dynamic, which has been described accurately by Lichtenberger (Citation1995) as having been ‘a frozen housing market’ for decades. Since the 1990s, the transaction dynamics have accelerated, reaching a peak in the 2010s (136 transactions, ). In contrast, the holding period displays a continuous decline: before World War II, the owners had held their properties for 50 years or more. Even in the 1970s, the holding period of owners was about 25 years on average. This however was the decade in which the average holding period started to drop significantly. In the 2010s, the average holding period was only about two years: the Zinshaus had turned into a tradable commodity that is used for speculation. Within the sample, 42 of 90 Zinshäuser have experienced four or more ownership changes (47%) since 1920s. In the subgroup of converted Zinshäuser, the statistic rises to 59% (33 of 56). In contrast, in the analysis of Kaufmann & Hartmann (Citation1984), only 5% of tenement houses had experienced four or more changes between the 1920s and 1982. Despite the fact that Kaufmann and Hartmann’s analysis is based on a shorter time period in different Viennese case-study areas, the acceleration of property changes remains quite obvious. This points to the increasing role of speculative traders – or dealers, in Haila’s terminology – who buy and resell a property for a higher price within a short period.

Figure 4. Ownership changes and holding periods in the Zinshaus sample (source: own data, own calculation).

Within our sample, the shift of ownership structure points to a clear commodification of housing. Former, private individual owners who had held the properties over decades, have been replaced by new, institutional property owners. The former group tended to invest cautiously due to the low, regulated rents that were often supported by public subsidies (e.g. the programme ‘soft urban renewal’, Fassmann & Hatz, Citation2006). The latter group seeks to circumvent these regulations. However, the picture is not that clear: in our analysis we have found institutional owners with a very short holding time (‘dealers’) as well as institutions with a long holding time (e.g. banks, insurance companies, …). Interestingly, these two opposite trends are both dominated by legal persons, which reflects the different approaches (short-term vs. long-term) that are present on the housing market (Wijburg et al., Citation2018).

5.2. Actors of commodification

The analysis of ownership changes point to a degree of heterogeneity within the group of ‘legal persons’. As various case studies (e.g. Romainville, Citation2017; Ruming, Citation2010) suggest, a stronger differentiation of these ‘actors of commodification’ appears to be necessary. Within the areas under investigation, we have identified 44 firms as relevant drivers of commodification for the 56 selected Zinshäuser. We labelled them as relevant if they have been listed in the land register as property owners before the conversion of the buildings. To deal with the considerable variety of actors, we classified them according to five possible types of actors who differ, e.g. in firm size, activity on the housing market, and their strategies along the housing provision chain ([HPC]; Ambrose, Citation1991; Musil, Citation2019). Below, we provide a brief description of these types, which we have also discussed and evaluated in the expert interviews.

Type 1: Micro actors. This is the most frequent type in our sample (15 firms). The micro actor is highly specialized in physical transformation and reconstruction on the Zinshaus market. The entrepreneurial owners of these small firms are often craftsmen with an immigration background. As is typical for small-scale firms (e.g. McGaffin et al., Citation2019), they rely on informal networks, which may also include their home country. These limited companies are usually founded just for one specific project. Cooperating firms, often owned by relatives, cover the other stages along the housing provision chain (e.g. structural planning and allocation). Most interview partners that were no micro actors had a critical view on this group of actors: … this small-scale Zinshaus loft conversion is solidly in Yugoslavian hands. Nobody gets registered and if something happens, the workers are sent home. The building materials also come from over there. […] After the project has been completed, the company goes bankrupt, to preclude any liability. […] We also sometimes sell to them. They pay an extremely high price, for which they compensate through the building costs (Interview 5, intermediary).

Familiar or informal networks are not only a strategy to compensate the high prices, but it is also the source of knowledge and expertise regarding the commodification of Zinshäuser. One micro actor stated: I used to scout for apartments for my ex-husband. Later on, I started doing it for myself (Interview 2, micro actor).

Type 2: Builders. This actor type (5 firms) also focusses on project development and construction but can be characterized as a medium-sized enterprise, run by architects and real-estate developers. Builders are either real-estate developers themselves who buy, develop, as well as physically and legally convert Zinshäuser, or they act as general contractors for other developers. Interview partners described their double role as developers and general contractors: And so we buy skeleton roof decks, undeveloped ones, or whole Zinshaus buildings, and go through the same process of planning, developing, building, and marketing. But we resell almost always. […] [As general contractors, add.] [we] build for externals, yes (Interview 9, builder).

Often having specialized in the construction of top storeys, builders acquire highly specific technical and legal know-how regarding the (re-)construction and renovation of historic buildings. To cover the HPC, builders collaborate with a fixed pool of stable partners. Due to their specialized knowledge, these actors enjoy a very good reputation, as other interview partners confirm: Yes, we work with them, too. They’re good, with them we’re doing two rooftop developments. The boys know their job. They do only the roof deck, they’ve specialised in that (Interview 6, big player).

Type 3: Big players. These actors (5 firms) focus their activities on large development projects in the sector of new construction. For them, the Zinshaus market merely constitutes a smaller business area (up to one third of their projects). Furthermore, these big (listed) companies do not limit their activities to the Viennese housing market only. Due to the size of the companies, all steps of the HPC can be covered internally. On the Zinshaus market, they can also hold functions that are typical for other parts of our typology: The big players can be traders, too, though. They simply cover different areas: trade, the residential market. They can also be asset managers, but they are more profit oriented. The big players have their own asset management (Interview 8, intermediary).

Big players are the only type of actor who can be labelled ‘financialized actors’ since they also finance their real-estate projects involving new construction via equity markets. However, projects on the Zinshaus market usually are financed by local banks.

Type 4: Intermediaries. These actors (12 firms), which are quite similar to the ‘dealers’ in Haila’s typology, focus on purchasing and reselling a building profitably without any or with only minimal additional investment. This is also a frequent actor type, and the firms display a considerable variation in size. The knowledge of traders about the steps of the HPC is superficial; if required, external partners cover individual steps of the HPC beyond buying and reselling. Interview partners had a quite critical view on this actor type, which seems to act in a kind of labour division with micro actors: …the traders buy, keep, and build very little. The Yugoslavian colleagues [micro actors; author’s note] do all of that. That is a kind of labour division, that is the reality (Interview 5, intermediary).

Type 5: Asset managers. These companies (7 firms) manage the property assets of a family or a foundation. Usually, these companies are small, and they operate in the background; most of them do not even maintain a website. The focus is on the preservation of existing real-estate assets. While intermediaries are visible via their web presence and advertising measures, establishing contact with (ideally private individual) owners of a Zinshaus by analyzing the land register, asset managers act restrainedly and almost invisibly.

The spatial distribution of those Zinshäuser that had undergone legal conversion with or without alterations of the physical structure points to a specific spatial pattern of the actors of commodification. If we allocate our 9 case areas to the centre-periphery gradient (), we can see that all five types of actors can be found in central locations (study areas 1, 2, 4, 5). In contrast, we can predominantly find projects related to micro-actors, intermediaries, and builders (four each) in the semi-peripheral locations (study areas 3, 6, 7), and only one each for the asset-manager type and for the big players. Further, in the peripheral locations (study areas 8, 9), micro actors and intermediaries are dominant drivers of commodification. The division of labour between these two types of actors, as mentioned above, seems to be relevant especially in peripheral locations. Builders and big players do not drive any projects in the periphery. Similar to the observation of Romainville (Citation2017) regarding large, financialized actors in Brussels, big players in Vienna also seem to focus only on well-established locations, where high prices imply low, but safeguarded profits. Apart from these central locations, big players are practically absent – at least in our sample – on the Zinshaus-market.

5.3. Commodification strategies along the housing provision chain

In the following, we discuss the strategies of commodification that are applied by the different types of actors we have identified. In general, most of our interview partners confirmed that the purchase of and investment in a Zinshaus is only profitable when it is converted into a condominium block: Parification [legal conversion] costs almost nothing. It’s very easy […]. It’s worth it for […] investors to throw some money at it, considering that one can then truly resell and doesn’t need to rent out any more and be stuck in the MRG […] And then, when you parify, then you get 7 000 Euro per square metre. Then you can more or less ignore the MRG […] (Interview 9, builder). Beyond legal conversion, demolition is the second means of circumvention of existing regulations: Purchase prices are currently high. I parify, and I sell off. That’s variant no. 1. Variant no. 2 – even worse, at least for you as observer. For the owner it’s simply an economic consequence, he would say o.k., I demolish. I’ll put up another shack, and then I’m in the free rental rate structure (Interview 3, micro actor).

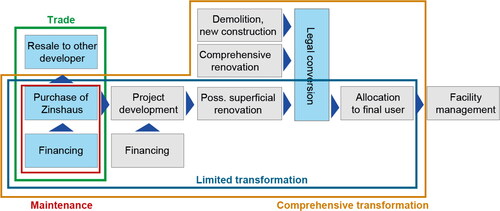

To capture the strategies of commodification on Vienna’s Zinshaus market, we suggest a modification of the housing provision chain (Ambrose, Citation1991), which is our analytical frame. shows the initial stages of the HPC in grey, with our additions in blue.

Figure 5. Commodification strategies alongside the housing provision chain on Vienna’s Zinshaus market (source: Ambrose, Citation1991, own compilation).

As all actors in our sample have been identified as owners of the property, the purchase is the starting point of the process of commodification. Hence, we suggest that the issue of financing is both related to the initial purchase and to the phase of project development if the actor is aiming at physical transformation. Regardless of the type of actor, all interviewed developers stated that their projects were funded solely through bank loans. Interestingly, these loans were all provided by small, regional banks from other parts of Austria (e.g. Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Burgenland, Styria, Vorarlberg): Our banks are out there, in [Town A] and [Town B]. There, I only need 10% equity capital, and it’s easier to speak. If you go to the bank in [Town C, provincial capital], you are welcomed (Interview 7, micro actor).

According to our interview partners, these banks offer unbureaucratic and fast-track decision procedures, since the branch director is the only decision-maker involved. This is not the case for large banks in Vienna, where applicants must go through multistage evaluation processes to screen the entire company structure. In order to participate in a highly competitive market such as the Zinshaus market in Vienna, actors need to act quickly: … the decision-making pathways are much shorter there. We’re on a bull market right now – one has to be quick. Smaller, regional banks have much shorter pathways. […] Larger banks are cheaper, but uncomplicatedness carries more weight. And I appreciate being able to talk face to face. At a large bank you never get to know the decision-maker (Interview 3, micro actor). This aspect is relevant insofar as it clearly shows that financialized actors and sources of funding do not play a role in this housing market segment. Due to its fast-moving dynamic and small-scaled structure, participation in this segment appears to be out of scope for them.

Based on our expert interviews, we identified four different strategies of commodification that might aim at bypassing the strict tenement law of the MRG, namely driving commodification via legal conversion and/or demolition. Firstly, there is the strategy of limited transformation, during which merely superficial renovations and partial alterations – such as the painting of façades or staircases – are undertaken (if any changes are made at all). The development of the rooftop is planned but not conducted. The sell-off of the (often non-renovated) owner-occupied flats is in focus here, whereas the non-developed rooftop will be sold to a developer (micro actor or builder) or to a private household. This limited transformation is described as follows: [Firm X] had nevertheless been very active. They tend to hold and then resell. These are the superficial renovators. They renovate the facade, the stairwell, but that is not worth much – in the end it is… as with [Firm X], they just brush over. Outwardly, it looks great, they get a building permit, and then they sell again, because to a degree, they don’t have any building expertise whatsoever. So they cannot build these objects, because they don’t have the team and the know-how they need (Interview 5, intermediary).

In contrast, secondly, comprehensive transformation involves rooftop extension, the installation of a lift, the renovation of all apartments, replacement of windows and reconstruction of the façade, and the modification of general areas such as bicycle rooms or inner courtyards. Finally, demolition and new construction, too, can be subsumed under this strategy of commodification.

The trade of a Zinshaus thirdly functions as a preliminary strategy leading to limited or comprehensive transformation. It applies the logic of reselling the property quickly, for the highest possible price. This speculative strategy is based on the assumption of steadily increasing prices as well as on the displacement of tenants. Here, the dwelling is nothing more than a tradable commodity: … the Zinshaus market is a very dynamic market. Individual properties are turned around [resold, comm.] very frequently. There is a clear tendency: trade has priority over building projects. Before a Zinshaus ends up with a building contractor, it often gets resold five times in a very short time span … (Interview 1, micro actor). It may also become an object of speculation, where there is the expectation of increasing prices: Yes, meanwhile it has become common that investors make their investments in these houses without expecting any return from current rents. They simply say o.k., I’m parking my money there. I might speculate and say, in five years I will sell it again at a higher price of, say, 5%, 10%, 15%, and in the meantime I do not care about the rents. In the past, this was the other way around … (Interview 3, micro actor). Since a Zinshaus without tenants has the highest value for a developer, firms offer a ‘de-tenement service’ (Kadi, Citation2017). In our interviews, developers were critical of this strategy, because it only leads to further price buoyancy, which impedes a reliable physical transformation.

Finally, the strategy of maintenance represents a special case. Asset management is a clear point of focus here. To ensure the preservation of the building structure, minor restoration work can be necessary. Owners might even carry out legal conversion, which would allow the selling of individual apartments: It is either kept, mostly by family businesses or private individuals, they also keep them. Or it is traded, sold. At some point, the building is then parified [legally converted]. And that would be the end of the Zinshaus… (Interview 3, micro actor).

provides an overview of actors and their strategies. However, developers engaging in the Zinshaus market as described here are not static, as firms can change their strategies due to growth or learning effects, or on account of changes in the market situation. In other words: A company that has been identified as one specific type of actor at one point in time can act as a different type of actor some years later. Over time, successful real-estate developers on the Zinshaus market might be able to gain specific knowledge, enlarge their networks of cooperation partners, and expand their businesses. As an example, formerly active intermediaries can develop into builders or big players: So [Firm X] had previously traded only, now they develop too (Interview 4, intermediary).

Table 1. Actors and commodification strategies on the Zinshaus market (source: own compilation).

Different types of actors that apply the same strategy do not only differ regarding their location and commodification strategies. They also produce different outputs: Micro actors as well as builders are specialized in the actual physical transformation of the Zinshaus. Although they apply the same strategy (comprehensive transformation), the physical transformation results can differ significantly. Compared with micro actors, builders are more likely to use high-quality materials, they usually have a background in architecture, and they usually aim for detailed restoration. also highlights the special role of big players, as they cover all strategies and decide on a case-to-case basis which strategy to employ.

6. Conclusions

This paper has analyzed the commodification of Vienna’s rent-regulated historic housing stock. Whereas this market was ‘frozen’ for decades, the combination of regulated rents and a sharp increase of prices on the property market have opened a ‘value gap’. This gap has prompted developers to circumvent existing regulations, which turned these historic tenement houses – Zinshäuser – into a profitable commodity. Our analysis of nine Viennese neighbourhoods shed light on the actors and their strategies of commodification. The results are based on a qualitative analysis of 90 Zinshäuser and 44 companies. Although these results must be interpreted cautiously, the in-depth analysis provides valuable insights that could not be provided by quantitative analysis.

Our analysis firstly reveals a rapid change of ownership structures, which points to the commodification of housing (Heeg, Citation2013, Wijburg et al., Citation2018). This is characterized by the dominance of institutional actors, declining holding times, and the almost complete disappearance of owner-used properties. Secondly, we identified great actor heterogeneity within the small sample of 44 companies. We have aggregated this into a typology of five actor types. These types differ in terms of their knowledge and activity along the HPC, as well as in the role that formal/informal networks play. The analyzed actors also point to different spatial strategies within the urban space. Even if these results must be interpreted cautiously, they confirm the outcome of other empirical studies (e.g. Romainville, Citation2017). In our case there also seems to be a degree of labour division between some of the identified actors, e.g. traders and micro actors.

Our typology of actors – which is also a typology of property owners – partly confirms certain existing typologies. Our typology might be seen as a differentiation of Haila’s typology (1991), where the exchange value of a property comes to the fore in the designations of ‘dealer’ and ‘speculator’. Whereas firm size is a main feature of differentiation in Ruming’s analysis (2010), this does not seem the case in our study. We find that small (micro actors), medium (builders), and large firms (big players) apply the same strategy of commodification (comprehensive transformation), albeit in different parts of the city and in different degrees of construction quality. Similar to McGaffin (Citation2019), we find that the role of informal networks seems to be a more relevant indicator, particularly for the large group of micro actors and traders.

On the whole, we propose that the highly specific regulation of Vienna’s historic housing stock has led to the rise of these types of actors and their strategies of commodification. Large, international, financialized actors do not exist here, as they do not possess the appropriate knowledge and cannot react quickly enough on this market. Thus, we suppose that different systems of regulation produce different constellations of actors. In these constellations, financialisation may or may not play a role. As such, our results correlate with the suggestion of Jacobs & Manzi (Citation2020) that the focus should rather be on preliminary processes of financialisation. Hence, the perspective of commodification provided additional insights into actors and strategies that would have been ‘invisible’ if we had looked at them through the conceptual lens of financialisation only.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments that helped us to improve our paper. Further we want to thank Dr. Hanneke Friedl for her precise editing of our manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Richtwertgesetz 2019 (Federal Law II, No. 70/2019).

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2019) Financial geography II: Financial geographies of housing and real estate, Progress in Human Geography, 43, pp. 376–387.

- Aalbers, M. B., Hochstenbach, C., Bosma, J. & Fernandez, R. (2021) The death and life of private landlordism: How financialized homeownership gave birth to the buy-to-let market, Housing, Theory Society, 38, pp. 541–563.

- Ambrose, P. J. (1991) The housing provision chain as a comparative analytical framework, Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 8, pp. 91–104.

- Arrighi, G. (1994) The Long Twentieth Century. Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times (London, New York: Verso).

- BEV (n.d.) Cadastre. Available at https://www.bev.gv.at/portal/page?_pageid=713,3175363&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL (accessed 18 January 2022).

- Bobek, H. & Lichtenberger, E. (1966) Wien: Bauliche Gestalt und Entwicklung seit der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts (Wien: Böhlau).

- Brousseau, F. (2015) Displacement in the Mission District (San Francisco: City and County of San Francisco Board of Supervisors).

- Byrne, M. & Norris, M. (2022) Housing market financialization, neoliberalism and everyday retrenchment of social housing, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 54, pp. 182–198.

- Chiu, R. L. (2001) Commodification of housing provision in urban China, in: P. Nan-Shong Lee & C. Wing-Hung Lo (Eds) Remaking China’s Public Management, pp. 97–113 (Westport, CT: Quorum Books).

- Christophers, B. (2015) The limits to financialisation, Dialouges in Human Geography, 5, pp. 183–200.

- City of Vienna/MA21 (2018) Masterplan Gründerzeit. Handlungsempfehlungen zur qualitätsorientierten Weiterentwicklung der gründerzeitlichen Bestandsstadt, Werkstattbericht, Vol. 42 (Wien: City of Vienna/MA21).

- Clark, E. (1992) On gaps in gentrification theory, Housing Studies, 7, pp. 16–26.

- Csizmady, A. (2020) Gentrification and functional change in Budapest–‘ruin bars’ and the commodification of housing in a post-socialist context, Urban Development Issues, 65, pp. 17–26.

- Debrunner, G. & Gerber, J.-D. (2021) The commodification of temporary housing, Cities, 108, pp. 102998.

- Ester, M., Kriegel, H.-P., Sander, J. & Xu, X. (1996) A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise, in: E. Simoudis, J. Han & U. Fayyad (Eds) Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pp. 226–231 (Portland: AAAI Press).

- Fassmann, H. & Hatz, G. (2006) Urban renewal in Vienna, in: E. György & Z. Kovacs (Eds) Social Changes and Social Sustainability in Historical Urban Centres. The Case of Central Europe, pp. 218–236 (Pecs: Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Centre for Regional Studies).

- Fenton, A., Lupton, R., Arrundale, R. & Tunstall, R. (2013) Public housing, commodification, and rights to the city: The US and England compared, Cities, 35, pp. 373–378.

- Fernandez, R. & Aalbers, M. B. (2016) Financialization and housing: Between globalization and varieties of capitalism, Competition and Change, 20, pp. 71–88.

- Fields, D. & Uffer, S. (2016) The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin, Urban Studies, 53, pp. 1486–1502.

- Forrest, R. & Williams, P. (1984) Commodification and housing: Emerging issues and contradictions, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 16, pp. 1163–1180.

- French, S., Leyshon, A. & Wainwright, T. (2011) Financializing space, spacing financialization, Progress in Human Geography, 35, pp. 798–819.

- Gillon, C. (2018) Under construction: How home-making and underlying purchase motivations surface in a housing building site, Housing, Theory and Society, 35, pp. 455–473.

- Glaser, D., Mörkl, V., Smetana, K. & Brand, F. (2013) Wien wächst auch nach innen. Wachstumspotentiale gründerzeitlicher Stadtquartiere, Stadt Wien, MA50 (Wien: ARGE Atelier).

- Gutiérrez, A. & Domènech, A. (2020) Understanding the spatiality of short-term rentals in Spain: Airbnb and the intensification of the commodification of housing, Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography, 120, pp. 98–113.

- Haila, A. (1991) Four types of investment in land and property, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 15, pp. 343–365.

- Hamnett, C. & Randolph, W. (1984) The role of landlord disinvestment in housing market transformation: An analysis of the flat break-up market in Central London, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 9, pp. 259–279.

- Harvey, D. (1982) Limits to Capital (Oxford: Blackwell).

- Heeg, S. (2013) Wohnen als Anlageform: Vom Gebrauchsgut zur Ware, Emanzipation, 3, pp. 5–20.

- Jacobs, K. & Manzi, T. (2020) Conceptualising ‘financialisation’: Governance, organisational behaviour and social interaction in UK housing, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 184–202.

- Kadi, J. (2017) Der Wiener Zinshausmarkt boomt – und was das für die MieterInnen bedeutet, urbaniZm, Available at https://urbanizm.net/4890592/der-wiener-zinshausmarktboomt-und-das-fur-die-mieterinnen-bedeutet/ (accessed 1 October 2021).

- Kaufmann, A. & Hartmann, B. (1984) Wiener Altmiethäuser und ihre Besitzer, Vol. 70 (Wien: Institut für Stadtforschung).

- Kaufmann, K. K. (2013) Verkauf kommunaler Wohnungsunternehmen an internationale Investoren, Auswirkungen auf lokale Stadtentwicklungs- und Wohnungsmarktprozesse, Geographische Revue, 14, pp. 38–66.

- Kinton, C., Smith, D. P., Harrison, J. & Culora, A. (2018) New frontiers of studentification: The commodification of student housing as a driver of urban change, The Geographical Journal, 184, pp. 242–254.

- Kohlbacher, J. & Reeger, U. (2006) Die Dynamik ethnischer Wohnviertel in Wien. Eine sozialräumliche Longitudinalanalyse 1981 und 2005. ISR-Forschungsbericht, Vol. 33 (Vienna: Institut für Stadt- und Regionalforschung).

- Lichtenberger, E. (1993) Vienna: Bridge between Cultures (London: Belhaven Press).

- Lichtenberger, E. (1995) Der Immobilienmarkt im politischen Systemvergleich, in: Faßmann, H. & Lichtenberger, E. (Eds) Märkte in Bewegung. Metropolen und Regionen in Ostmitteleuropa, pp. 47–57 (Vienna: Böhlau).

- Lunde, J. & Whitehead, C. (2016) European housing finance models in 1989 and 2014, in: Lunde, J. & Whitehead, C. (Eds) Milestones in European housing finance, pp. 15–35 (Sussex: Wiley Blackwell).

- Madden, D. & Marcuse, P. (2016) In Defense of Housing. The Politics of Crisis (London: Verso).

- Matznetter, W. (2019) 100 Jahre Mieterschutz: Ein Instrument zur Steuerung von Gentrifizierung, in: J. Kadi & M. Verlic (Eds) Gentrifizierung in Wien. Perspektiven aus Wissenschaft, Politik und Praxis?, pp. 13–24 (Vienna: Arbeiterkammer Wien).

- Matznetter, W. (2020) Integrating varieties of capitalism, welfare regimes, and housing at multiple levels and in the long run, Critical Housing Analysis, 7, pp. 63–73.

- McGaffin, R., Spiropoulous, J. & Boyle, L. (2019) Micro-developers in South Africa: A case study of micro-property developers in Delft South and Ilitha Park, Cape Town, Urban Forum 30, pp. 153–169.

- Musil, J. (1995) The Czech housing system in the Middle of transition, Urban Studies, 32, pp. 1679–1684.

- Musil, R. (2019) Immobiliengeographie. Märkte. Akteure. Politik. (Braunschweig: Westermann Verlag).

- Musil, R., Brand, F., Huemer, H. & Wonaschütz, M. (2022) The Zinshaus market and gentrification dynamics: The transformation of the historic housing stock in Vienna, 2007–2019, Urban Studies, 59, pp. 974–994.

- OeNB (2021) Immobilien aktuell - Österreich. Die Immobilienmarktanalyse der OeNB Q2/21 (Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbank).

- Paccoud, A., Hesse, M., Becker, T. & Górczyńska, M. (2022) Land and the housing affordability crisis: Landowner and developer strategies in Luxembourg’s facilitative planning context, Housing Studies, 37, pp. 1782–1799.

- Poovey, M. (2015) On ‘the limits to financialization’, Dialogues in Human Geography, 5, pp. 220–224.

- Porter, M. (2010) The rent gap at the metropolitan scale: New York City’s land-value valleys, 1990–2006, Urban Geography, 31, pp. 385–405.

- Rogers, D. & Koh, S. Y. (2017) The globalisation of real estate: The politics and practice of foreign real estate investment, International Journal of Housing Policy, 17, pp. 1–14.

- Rogers, D., Nelson, J. & Wong, A. (2018) Geographies of hyper‐commodified housing: Foreign capital, market activity, and housing stress, Geographical Research, 56, pp. 434–446.

- Romainville, A. (2017) The financialization of housing production in Brussels, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, pp. 623–641.

- Ruming, K. (2010) Developer typologies in urban renewal in Sydney: Recognising the role of informal associations between developers and local government, Urban Policy and Research, 28, pp. 65–83.

- Segú, M. (2018) Do short-term rent platforms affect rents? Evidence from Airbnb in Barcelona MPRA Paper No. 84369, Munich.

- Siebel, W. (2004) Die europäische Stadt (Frankfurt am Main: edition suhrkamp).

- Smet, K., Nagl, E., Rätzer, F., Scherer, T., Schuster, J. & Steiner, C. (2015) From Land to Housing. A GPN Approach of Salzburg. Geographies of Uneven Development. Salzburg, Vol. 7 (Salzburg: University of Salzburg).

- Smith, N. (1987) Gentrification and the rent gap, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 77, pp. 462–465.

- Smith, D. P. & Hubbard, P. (2014) The segregation of educated youth and dynamic geographies of studentification, Area, 46, pp. 92–100.

- Statistik Austria (2021) Housing database 2021, Available at https://www.statistik.at/web_en/statistics/PeopleSociety/housing/housing_costs/index.html (accessed 1 February 2022).

- Sykora, L. (1995) Wohnungspolitik in der Tschechischen Republik, in: H. Faßmann (Ed) Immobilien-, Wohnungs- und Kapitalmärkte in Ostmitteleuropa, pp. 49–68 (Wien: Institut für Stadt- und Regionalforschung).

- Teresa, B. (2019) New dynamics of rent gap formation in New York City rent-regulated housing: Privatization, financialization, and uneven development, Urban Geography, 40, pp. 1399–1421.

- Theurillat, T., Vera-Büchel, N. & Crevoisier, O. (2016) Commentary: From capital landing to urban anchoring: The negotiated city, Urban Studies, 53, pp. 1509–1518.

- Vilenica, A., Katerini, T. & Hrast, M. F. (2021) Housing commodification in the Balkans: Serbia, Slovenia and Greece, Κοινωνική Πολιτική, 14, pp. 81–98.

- Waldron, R. (2018) Capitalizing on the state: The political economy of real estate investment trusts and the ‘resolution’of the crisis, Geoforum, 90, pp. 206–218.

- Weigl, A. (2003) "Unbegrenzte Großstadt" oder "Stadt ohne Nachwuchs"? Zur demographischen Entwicklung Wiens im 20. Jahrhundert, in: F. X. Eder, P. Eigner, A. Resch & A. Weigl (Eds) Wien im 20. Jahrhundert. Wirtschaft, Bevölkerung, Konsum, Querschnitte, Vol. 12, pp. 141–200 (Vienna: Studienverlag).

- Wijburg, G., Aalbers, M. B. & Heeg, S. (2018) The financialisation of rental housing 2.0: Releasing housing into the privatised mainstream of capital accumulation, Antipode, 50, pp. 1098–1119.

- Wu, F. (2015) Commodification and housing market cycles in Chinese cities, International Journal of Housing Policy, 15, pp. 6–26.