Abstract

Despite significant policy developments addressing youth housing insecurity in Australia, youth remain subject to multiple housing arrangements that can lead to homelessness more than any other cohort. We focus on the housing sequences of youths, and we seek information in the order and duration of accommodation types used. We employ Journeys Home – a unique longitudinal dataset specifically designed to examine issues relating to homelessness or housing instability in Australia. We combine accommodation calendars with data-driven sequence analysis techniques that holistically consider the information in the accommodation sequence. Specifically, we identify a set of distinct accommodation typologies and find that those who experience the greatest housing insecurity are comparatively less likely to be educated or employed and more likely to have dependent children who are not living with them. Importantly, we find that not all housing insecurity is necessarily associated with primary homelessness.

1. Introduction

Youth homelessness is a problem in many developed countries and is of concern as it has lasting (scaring) impacts throughout the life course and intergenerational effects. Young people experiencing housing insecurity have often suffered intergenerational issues of disadvantage and trauma (Flatau et al., Citation2013, Citation2020). Further, Scutella et al. (Citation2013) find those who experience homelessness at a young age are more likely to experience persistent homelessness into adulthood. Structural factors such as inequalities in access to housing, appropriate housing stock and wealth can also drive homelessness (see, e.g. Early, Citation2004; Johnson et al., Citation2019). It is, therefore, of societal importance to be able to understand the youth accommodation typologies to implement targeted and effective policies.

Research into the residential accommodation patterns of youth who experience housing insecurity has focused on the types of accommodation used to explain longitudinal patterns (Chamberlain & Johnson, Citation2013; Clapham, Citation2005; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2013). In this article, we focus on identifying accommodation typologies associated with youth housing insecurity. However, the types of accommodation utilized by young people can be highly varied as young people experiencing housing insecurity often have disrupted personal and family backgrounds and multiple forms of inequity and disadvantage. Youth typically have indirect routes to housing insecurity and/or actual homelessness, such as staying with relatives and friends or other unstable accommodation forms. Moreover, the homeless literature provides a limited understanding of patterns in accommodation types utilized and variations in the lengths of stay across accommodation types that can be complex and nuanced (Fitzpatrick, Citation2000).

Here we offer a social sequence approach to profiling youth housing insecurity by identifying distinct accommodation types (such as staying with friends (couch surfing) and hostels) and length of stay (durations/spells) over time, referring to each pattern as an accommodation sequence. It is important to look at the accommodations utilized and lengths of stay jointly, as different accommodations may be associated with different lengths of stay. We investigate whether there is information in the holistic sequence instead of analysing experiences separately for each accommodation type, revealing if certain accommodation sequences are more likely to result in homelessness. The identification of commonalities across sequences allows us to define accommodation typologies. The power of analysing the entire accommodation sequence is that information on path dependence does not get lost, as it might when using a partial step-by-step approach that analyses each accommodation change in isolation (Pollock et al., Citation2002). Techniques focusing on a single accommodation cannot account for the information in entire sequences (Fuller, Citation2011). Thus, the true value of the social sequence approach is the multidimensionality of the accommodation sequence across accommodation types and durations compared to existing unidimensional studies on either accommodation types or durations.

Considering the socio-demographics of youth who are characterized by different accommodation typologies allows for early intervention to prevent homelessness and its subsequent scaring effects. Additionally, identification of similar patterns in accommodation sequences allows for a more accurate understanding of housing needs over time, including the extent of repeat demand or entrenched needs of the same individuals. Moreover, individual youth accommodation sequences and the socio-demographic characteristics of those experiencing them are more easily observable from a public policy perspective than complex family backgrounds or (often) hidden behaviours such as alcoholism, also known to be associated with housing insecurity and homelessness.

This article addresses three research questions. Research question one (RQ1) asks how many distinct youth accommodation typologies can we identify among youth identified as housing insecure? Research question two (RQ2) asks what are the distinct accommodation sequences that describe these typologies? Research question three (RQ3) asks what are the key socio-demographic profiles of youths defined by each accommodation typology?

Analysing accommodation sequences is a multidimensional task that requires high-quality data. Our study uses the unique Australian dataset Journeys Home which follows 479 youths aged 15 to 24 years who faced housing insecurity over two- and a half years. The dataset is a six-wave panel study of housing instability and homelessness among disadvantaged Australians. Specifically, Journeys Home contains a sample of welfare recipients identified as homeless or at risk of homelessness (Melbourne Institute, Citation2012). This definition is reflective of the United Nations definition of homelessness, which identifies two categorizations: the primary homeless being those who are roofless and the secondary homeless being those who have no fixed dwelling or frequently move between accommodation types (United Nations, Citation2009). The richness of Journeys Home data for our research questions is in the precision of the individual accommodation histories in a notoriously itinerant and challenging-to-trace population.

This is the first article to our knowledge to apply sequence analysis to youth accommodation sequences to decode information contained within accommodation sequences. We find that youth homelessness is not homogeneous and can be summarized by four distinct accommodation typologies. Secondly, by profiling these accommodation typologies, we find that those within our sample who experience high levels of housing insecurity are comparatively less likely to be educated and more likely to have dependents who are not living with them relative to others in our sample. Given the age of the cohort, insecure accommodation environments also put the children of these youth at risk of future housing insecurity, potentially leading to intergenerational housing insecurity. Moreover, in many cases, the children do not reside with their parents, which also has welfare implications.

2. Literature: causes and typologies of youth homelessness

Housing insecurity relates to an individual living without an adequate or regular dwelling/residence. As well as meeting obvious physical needs, a home enhances an individual’s mental health by providing a sense of belonging and promoting wellbeing; therefore, having a secure, regular dwelling is an essential, basic need. Unfortunately, there is no internationally accepted definition of homelessness, and homelessness figures vary greatly according to the definitions employed. A wealth of literature considers and proposes different definitions (see, e.g. Amore et al., Citation2011; Springer, Citation2000;). Typically, Governments tend to employ narrow definitions focusing on primary homelessness (rooflessness), while other agencies employ broader definitions capturing housing insecurity by including those at risk of homelessness. It is also recognized in the literature that definitions of homelessness are a relative measure of the cultural housing norms of a country (Chamberlain & Mackenzie, Citation2008). Our study is based in Australia, where the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) utilizes a definition emphasizing the ‘home’ in homelessness (ABS, Citation2012). The ABS definition recognizes the primary (i.e. without conventional accommodation), secondary (i.e. temporary insecure accommodation) and tertiary (i.e. boarding houses without tenure) levels of homelessness. Additionally, in the case of youth homelessness, there is no standard age-defined definition (Abdul Rahman, Citation2015). While we will not be contributing to this literature (as our definition of homelessness is determined by the sampling frame of our dataset), it is important to note this literature as it impacts the direct comparability of the papers discussed in this review.

The literature on homelessness is vast and across several disciplines. Here we provide only a brief survey of the literature focused on the causes of youth homelessness and the typologies that have been identified.

2.1. Causes of youth homelessness: behavioural and relational factors

Several common factors are associated with youth who experience homelessness. Interestingly, the literature suggests both behavioural and relational factors are drivers of youth homelessness. MacKenzie et al. (Citation2016) show that youth often experience homelessness and disadvantage when family support is weak or non-existent. Furthermore, Cobb-Clark & Zhu (Citation2017) identify associations between homelessness and family violence, lack of security, exposure to drugs and alcohol, mental health issues, and exposure to the criminal justice system. Regarding youth homelessness, pathways through alcohol and drugs have been extensively studied (see, e.g. Johnson & Chamberlain, Citation2008; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2013). Adverse childhood experiences are also important factors. Many individuals have experienced state care and/or family trauma, where state care includes residential care and foster care. Childhood trauma before 14 years of age is a common factor associated with homelessness (Keane et al., Citation2016). Among homeless youth, foster care is also a strong determinant of homelessness and housing insecurity. Youth who have experienced foster care are more likely to be homeless for longer durations than those who have not been in the foster care system (Bender et al., Citation2015; Chamberlain & Johnson, Citation2013). Single parenting in youth has also been identified as a pathway to homelessness. Morton et al. (Citation2018) find those most at risk of homelessness are unmarried with their own children. All this literature suggests early life relationships within the family are critical, and adverse early life events can lead to housing insecurity in youth. These adverse events might be due to dysfunctional familial relationships or harmful behaviours in childhood.

This literature identifies pathways into homelessness through the identification of a set of personal risk factors. However, many of the factors identified are not easily observable. This is an obvious problem with the risk factors approach that impedes targeted early interventions and policy recommendations.

2.2. Causes of youth homelessness: accommodation types

An alternative strand of literature investigates the significance of different accommodation experiences on homelessness. Housing mobility studies utilizing longitudinal data find a close relationship between housing profiles, income, and jobs (Clark et al., Citation2003; Pollock, Citation2007). Others note intergenerational poverty and neighbourhood effects (Lee et al., Citation2017). Scutella et al. (Citation2013) document the regularity of couch surfing among youth with housing insecurity, which is often a precursor to sleeping rough (McLoughlin, Citation2013). However, many youth experience fluidities of housing arrangements that do not neatly fit into a single experience (Curry et al., Citation2017; Morton et al., Citation2018). Earlier studies demonstrated that individuals might intermittently find accommodation but returning to homelessness depends on these intermittent dwellings’ quality, stability, and adequacy. This is important as reducing so-called ‘churning’ through homelessness services may result in homeless people finding longer-term stable accommodation (Flatau, Citation2009). Often, episodic homelessness is more common than continuous homelessness (May, Citation2000; Sosin et al., Citation1990). Housing mobility studies note disadvantaged youth are often prevented from exercising effective housing choices (Coulter & Van Ham, Citation2013; Pollock, Citation2007). Other studies have used trajectories from youth to examine the life course of disadvantage (Elzinga & Liefbroer, Citation2007; Piccarreta & Billari, Citation2007; Pollock, Citation2007) to understand long-term impacts.

While the literature above considers accommodation types and is informative of accommodation use and demands, it only looks at accommodation types in isolation from the sequences in which youths experience them. But it is also important to understand if couch surfing always leads to primary homelessness or if primary homelessness is more likely if couch surfing follows foster care. A related strand of literature employs accommodation sequences to analyse individual and family mobility in housing careers. This literature is predominantly US based and looks at housing quality and local neighbourhood characteristics. Clark et al. (Citation2003) show a relationship between housing consumption and quality and a household’s income and income growth. Coulter & Van Ham (Citation2013) highlight the importance of financial resources in determining accommodation outcomes and limiting choices. Pollock (Citation2007) shows low income (often resulting from income shocks such as after divorce) is a significant factor in unsatisfactory accommodations. Van Ham et al. (Citation2014) focus on relational factors in terms of the housing and neighbourhood quality of a person’s parents and how this affects housing outcomes as adults. They conclude that housing disadvantages can be inherited and long-lasting. Lee et al. (Citation2017) indicate the importance of starting positions. Where a household initially forms in public housing, the duration of time spent in this type of housing is longer, highlighting the importance of the order of accommodations experienced in the subsequent duration of time spent in a different type of accommodation. These studies focus on housing careers across this life course is important as they highlight that information is contained within accommodation sequences.

2.3. Causes of youth homelessness: structural factors

The literature noted so far points to individualistic drivers of homelessness and suggests that personal factors are causes of homelessness. This literature is often criticized, as there can be a tendency to assume that the drivers of homelessness are a result of poor choices when in reality, many of the risk factors are beyond the individual’s control. For example, Somerville (Citation2013) critiques the risk factor approach and calls for studies to go beyond focusing on episodes of rooflessness to consider the lives of homeless people. As a result of this criticism, there is also a strand of literature that speaks to the influence of structural factors and societal inequalities (beyond the individual’s control and their personal circumstances), to broader (often macroeconomic) factors like unemployment, housing markets, and poverty (see, e.g. Early, Citation2004; Johnson et al., Citation2019). Moreover, there is an argument that these structural factors expose vulnerable groups to homelessness more than others (Bramley & Fitzpatrick, Citation2018). O’Flaherty (Citation2004) argues that it is not just the wrong place but also being the wrong person in the wrong place that matters. This argument leans to the hybrid approach, allowing for individual and structural factors in explaining homelessness (Benjaminsen & Andrade, Citation2015). This hybrid approach has also been adopted by Batterham (Citation2019) to develop a definition of ‘at risk of homelessness’.

2.4. Homeless typologies

The final area of the literature that we will review is the literature on homeless typologies. This literature is closely aligned to our study. Identifying homeless typologies is important for allowing targeted interventions to prevent and support the homeless and those at risk of homelessness. The typical approach here is to use cluster analysis to define groups according to common usage of particular types of accommodations. The seminal paper employing this methodology is Kuhn & Culhane (Citation1998), who identify three typologies of sheltered accommodation users: chronic, episodic, and transitional. They then considered the common characteristics of the individuals within each typology. The findings of this study were later replicated by Aubry et al. (Citation2013) and Rabinovitch et al. (Citation2016), who identified three typologies: long-stay, episodic and temporary. McAllister et al. (Citation2011) showed that it is not just the frequency of use that matters for defining typologies but also the duration of use. They identified ten different typologies of shelter users from this time-patterned approach.

Moving beyond sheltered accommodation, Farrow et al. (Citation1992) define four homeless youth typologies using cluster analysis: (1) throwaway youth (who are forced to leave their homes; (2) street youth (who live on the streets); (3) runaway youth (who have run away from homes, and (4) system youth (who exit the juvenile justice system or foster care). In another cluster analysis, Milburn et al. (Citation2009) defined typologies based on risk factors (i.e. substance abuse) and protective moderators (i.e. attending school). However, this approach is problematic from as policy perspective, as already noted, because many risk factors are not readily observable. For a review of homeless typologies across multiple methodologies, see Toro et al. (Citation2011).

Our paper branches across and brings together the housing careers literature and the homeless typology literature. We will employ youth accommodation sequences (utilized in the housing careers literature) to identify housing typologies through a full sequence analysis methodology (a technique that to our knowledge, has not been applied in the youth homeless typologies literature). Importantly, typologies are helpful to policymakers when they are identified from observable accommodation sequences, whereas ‘risk factor’ approaches can be problematic as many of these factors are not easily observable.

3. The Journeys Home dataset

To date, very few longitudinal datasets have been produced that focus on housing insecurity and homelessness, in part due to the difficulties of tracking those facing housing insecurity over time. Journeys Home is an exception as it provides six waves of data at 6-month intervals from 2011 to 2014. Although the final wave was in 2014, the dataset remains unique in terms of its sampling framework and continues to be an influential dataset for evidenced-based policy. The survey is a national sample of individuals the Australian Government identified as at immediate risk of housing insecurity, clustered around 36 distinct geographical areas across Australia. These individuals are vulnerable to homelessness due to the precarious nature of their accommodation. In the full sample (aged 15 years or over), the 62% response rate in wave 1 resulted in 1682 individuals. Despite high mobility of the target population, the attrition rate in Journeys Home is low, at just 16% by wave 6. This final wave of data contains 1406 individuals aged 15 years or over, and 479 individuals in our target sample are aged between 15 and 24 in wave 1. While the data is collected over a fixed window of time, 2.5 years is nevertheless a reasonable length of time given the cohort is aged 15 to 24 years and youth is a transitory period in the life course. Wooden et al. (Citation2012) detail the survey methodology.

The dataset represents a rich data source for studying housing insecurity and homelessness. It links survey information with the Australian Government’s social security/welfare payments administrative database. Indicators flag individuals who are homeless or at immediate risk of homelessness. In this regard, it is essential to note the sampling methodology – the sample contains individuals who present to the government agency responsible for social security/welfare payments and services and are known to be homeless or at risk of housing insecurity. Including those at risk of housing insecurity is important for our study as it allows us to see the accommodation sequences leading to homelessness. Wave 1 respondents were homeless (35%), at risk of homelessness (37%), or vulnerable to homelessness – defined as ‘statistically similar to those at risk of homelessness (28%)’ (Bevitt et al., Citation2014).

The survey’s accommodation calendar tracks each respondent’s housing arrangements between interviews and ideally suits our analytical purpose. Calendar information is recorded back to the previous interview for individuals who miss responding to a wave. Adopting this ‘extended reference period’ minimizes gaps in accommodation histories but increases the possibility of recall bias. The combination of survey and administrative information to measure demand for different types of accommodation is somewhat less problematic than relying on administrative data alone, as the survey data includes individuals who require assistance but do not present for services. For individuals experiencing housing insecurity, a great deal may change in a short time, while for others, periods of relative stability may be observed. To capture frequent changes and observe trends, it is essential to track respondents often and over an extended period. Therefore, Journeys Home provides a unique opportunity to consider housing patterns for this group of vulnerable people over a 2.5-year period. Specifically, the accommodation calendar allows individuals to record their accommodation under several types (see ).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of accommodation sequences.

Fieldwork for each wave spanned some 2.5 months, with wave 1 carried out between September 2 2011 and November 23 2011 and wave 6 between March 1 2014 and May 12 2014. Staggered fieldwork means the timing of initial and final calendar entries varies among individuals. Rather than restrict the sequences to a shorter period common to all individuals (i.e. trimming the ends), we created a 15th category of accommodation (missing) to extend later beginnings and earlier endings to a common period. For each change in accommodation type that occurred between surveys, individuals reported the year and month when they moved and whether they left at the beginning (days 1–10), middle (days 11–20), or end (days 21–31) of the month. Multiple movements within a month-third are not captured – only the main form of accommodation is recorded. These data are then aggregated over all waves and provided in consecutive spell format as a calendar of spells in up to 14 types of accommodation over 98 time periods. Each spell has a corresponding start date and duration. We then transform the accommodation data into person-period format (individuals by month-thirds) and select a balanced panel of individuals with usable data in at least waves 1 and 6 for analysis. The resulting sample size is 479 individuals aged 15 to 24 years from the original wave 1 respondents. Males represent 45.72%, and females 54.28% of this sample. To preserve individual confidentiality in compliance with the Journeys Home restrictions, a single figure showing individual sequences for the group as a whole is included. With so many individuals, unique details are not visible.

This high-frequency longitudinal data means that Journeys Home is preferable to traditional household survey-based datasets that typically underreport on youth and those who are housing insecure due to their sampling frames. Moreover, household surveys suffer from recall issues when attempting to build accommodation diaries as they are typically only collected annually.

For our analytical sample, shows frequencies with which individuals are resident in different types of accommodation over time. For ease of exposition, results are presented in months rather than month-thirds. On average, individuals use 2.39 types of accommodation and spend an average of just 15.76 months across all spells living in their own home. There is an average of two spells spent squatting, with each spell averaging 6.67 months. The youth participants have an average frequency of 1.46 spells sleeping at friends’ homes but for relatively short durations – just 4.72 months on average. The variation in accommodation use across multiple arrangements highlighted in our analytical sample is consistent with the findings of the extant literature (Curry et al., Citation2017; Flatau, Citation2009; Morton et al., Citation2018).

4. Methodology

This article uses a social sequence technique, a subfield of sequence analysis that originated in bioinformatics. The technique has been applied in a variety of contexts, such as employment careers (Anyadike-Danes & McVicar, Citation2005, Citation2010; Brzinsky-Fay, Citation2007); partnership histories and patterns in birdsong (Martin & Wiggins, Citation2011); transitions from school to work (McVicar & Anyadike-Danes, Citation2002); geographical residential mobility (Stovel & Bolan, Citation2004) and transitions to retirement (Fasang, Citation2010; Han & Moen, Citation1999). The aim is to examine temporally ordered social sequences, in our case, accommodation sequences (see Elkins et al., Citation2020). This approach allows us to:

Compare individual housing sequences in our sample to find similar typologies in terms of types of accommodation and length of stay (RQ1).

Identify the intrinsic features of these typologies, such as the types of accommodation that are typically used and the duration of stay (RQ2).

Identify the average characteristics of individuals within a typology (RQ3).

We begin by detecting accommodation typologies among the individual accommodation sequences (RQ1). Optimal Matching is used to determine the similarity of patterns. The Optimal Matching process is an iterative minimization procedure that measures the numeric distances between every pair of sequences. This generates a distance matrix comparing every sequence to every other sequence, ranking sequences according to their similarity. The distance matrix is obtained by considering the lowest total ‘cost’ by which each sequence pair can be made to look identical, with lower costs indicating more similar pairs of sequences. In calculating costs, the sequences are made identical by various operations: insertion, deletion, or substitution of accommodation elements at points along with the two sequences.

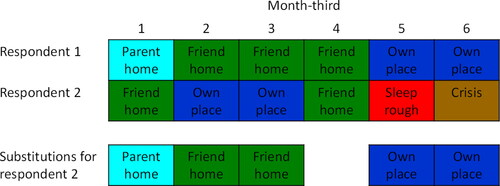

For example, consider two hypothetical accommodation sequences for two respondents over 6 month-thirds (). In month-third, number 4, the ‘elements’ in each sequence are the same as the two respondents used identical accommodation types (friend home). For the remaining five month-thirds, the two sequences differed in accommodation types used at the same time. These sequences can be made identical by substituting accommodation types to make the patterns for respondents 1 and 2 match. This type of matching for these two sequences would involve five substitution operations and after assigning costs to each operation, the total cost measures the similarity for these two sequences. In this example, we have considered only substitutions. However, these two sequences can also be made to match using combinations of substitutions, insertions, and deletions.

It is not possible to objectively identify distances between each of the various accommodation types. Even though we know some forms of accommodation, perhaps living with parents, on one’s own, or with friends, are more similar than others, such as living with parents versus crisis accommodation or squatting. Therefore, we attach the same costs to each form of accommodation. Among the many possible transformations, the optimal solution is chosen using the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm based on dynamic programming (for further details, see Pearson & Miller, Citation1992). Once all sequences are compared to all other sequences, a distance matrix is constructed from the total minimum costs.

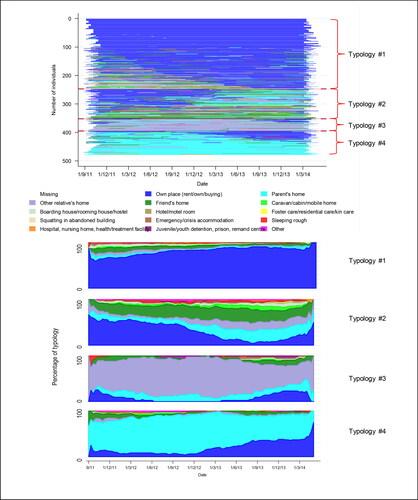

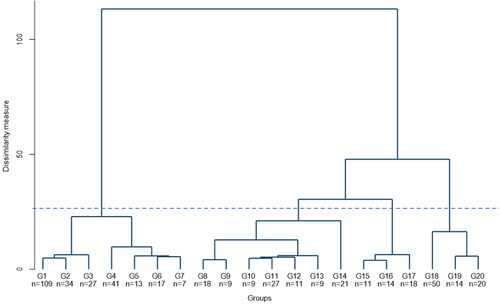

Next, Cluster Analysis is used to identify groups based on the distance matrix. This technique maximizes within-cluster similarity and minimizes between-cluster similarity. Optimal Matching and Cluster Analysis (OMCA) is specifically designed to analyse the information contained in ‘calendar-style’ data sequences, as Cornwell (Citation2015) explained. There is no requirement for OMCA to yield groups of the same or similar size; the pattern’s similarity rather than ‘commonality’ matters. These statistically identified clusters represent the accommodation typologies. We examine a dendrogram to determine the number of distinct clusters that maximize within cluster similarity and between cluster differences (). For ease of interpretation, the dendrogram shows only the final stages of the clustering process, with horizontal lines indicating the joining of clusters and distances between clusters shown on the vertical axis. In our case, we have selected four clusters as indicated by the horizontal line intersections. That is, we combine groups 1–7 (248 individuals), groups 8–14 (104 individuals), groups 15–17 (43 individuals), and groups 18–20 (84 individuals). Increasing the number of clusters would necessitate first separating group 14 into its own cluster, resulting in only 21 members in that typology. We then use sequence index plots of individual accommodation sequences to visualize the individual trajectories and a chronograph to view the prevalence of different accommodation types used by individuals over time (RQ2). The identified typologies can then be described by the characteristics of the distinct sequence patterns they represent. To profile the typologies by the mean characteristics of the groups, it is important that n ≥ 30 for the Central Limit Theorem to apply so that the profiling is statistically robust. Hence the four typologies identified in this analysis. We produce tables for the typologies presenting the initial characteristics of the individuals, such as age, gender, education, and labour force status, and changes over time (RQ3).

Figure 2. Dendrogram.

Dendrogram using Ward’s distance to cluster individuals. Only final stages of agglomerative clustering shown.

Stata 14 and its sequence analysis routines (Brzinsky-Fay et al., Citation2006) are used for sequence analysis.

5. Results

Given that the sampling frame consists of a sample of homeless and at risk of homelessness individuals, it is important to note that while a random sample of this population is contained in our data, the generalization of our results outside of this group is not straightforward due to the selection effects that result in housing insecurity. However, we can reliably compare within sample differences between typologies, and this is our principal aim.

We begin by presenting the sequence index plot and chronographs for each typology () (addressing RQ1) and the description of these typologies in terms of the accommodation sequences they represent (addressing RQ2). We then characterize the individuals within each typology (addressing RQ3).

5.1. Identification of accommodation typologies (RQ1)

The first panel in shows the actual accommodation sequences in the sequence index plot, where each colour represents an accommodation type. Four distinct typologies are identified. This is the maximum number of typologies that can be identified, such that the sample size within each typology is at least 30.

Typology 1: Own home

This typology is represented by relatively stable accommodation, with individuals predominantly housed in their own home, whether renting, owned or buying, with long durations of stay. The number of observations (n) is 248.

Typology 2: Churning

This typology is characterized by highly volatile accommodation sequences, with many transitions between different accommodation types and multiple and/or repeat transitions with short durations. Here n = 104.

Typology 3: Relatives

This typology shows relatively stable accommodation with other relatives (non-parents). However, it also represents a form of homelessness characterized by being in a juvenile or youth detention centre, an adult prison, or a remand centre. Here the average durations are relatively long. Here n = 43.

Typology 4: Parents

This typology represents individuals who mostly live with their parents, with some short spells of alternative accommodation. Here n = 84.

The names given to the typologies reflect the nature of the principle accommodation experienced, and the choice of ‘churning’ for typology 2 reflects existing terminology in the literature. Identification of these typologies supports our approach to treating the accommodation calendars as sequences and highlights important information in both the order and durations in which youth experience different accommodations. The intrinsic features associated with the typologies reflect the accommodation sequences’ overall level of housing insecurity.

Next, we consider the chronographs; while the sequence index plot is designed to be read horizontally, the chronographs (the lower panel in ) are better considered vertical representations of the demand for different accommodation types at a given point in time. These provide a visualization of accommodations utilized. We can see that individuals predominantly use one form of accommodation for typologies 1, 3, and 4. However, for typology 2, there is a demand for several different accommodation types at any point in time across the sample, and the type of accommodation needed by any individual varies over time.

5.2. Description of the typologies (RQ2)

Next, we take a detailed look at the mean characteristics of the accommodation sequences in each typology ().

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of accommodation sequences, typology 1.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of accommodation sequences, typology 2.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of accommodation sequences, typology 3.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of accommodation sequences, typology 4.

Typology 1 (own home) represents the largest typology (51.77% of the cohort). Most individuals are in their own place (), and over 99% of individuals in this typology spend some time in their own place (). However, some individuals in this group face some insecure housing situations outside of a private home environment, with 7.26% who spend an average of 7.16 months in a spell in boarding/rooming houses or hostels. There are also 10.48% who spend 4.48 months in a spell in emergency/crisis accommodation. Additionally, 6.85% of individuals in this typology spend time sleeping rough, although the experience is short-lived and infrequent (1.29 spells averaging 1.98 months).

Typology 2 (churning) represents 21.71% of the cohort. shows that about half of these individuals live in their own place in the early to mid-stages of the observation window but later move out, typically to reside with friends or family. This typology shows the largest average number of accommodation types used (3.35). On average, 9.19 months of the window is spent living in their own place, 7.41 months with friends, 5.09 months with parents, and 3.34 months with other relatives. Of the individuals in this typology, 85.58% spend time in their own place.

For this typology, 11.54% use crisis accommodation and 12.50% sleep rough. In this typology, individuals will likely experience these types of housing more than once: on average, for crisis accommodation, the mean is 1.17 spells, and for rough sleepers, it is 1.46 spells. Of note in this group is the use of services: youth using emergency or crisis accommodation are doing so for an average of 3.71 months per spell. However, the number of individuals using these services is relatively small (11.54%). A small proportion (4.81%) of individuals in this typology spend time in a hospital or a treatment facility, tending to have a relatively high frequency (1.8 spells) of relatively short stays (2.85 months). Interestingly, 0.96% spend time in foster care only stay for four months on average in this arrangement. However, there is no repeated accommodation pattern for foster care, with young people in this typology only having one spell on average.

Typology 3 (relatives) is the smallest group, representing only 8.98% of the cohort. The accommodation sequences are relatively stable, with individuals averaging 2.6 types of accommodation over the sample. Everyone in this typology spends time with relatives other than their parents, averaging 21.06 months over the sample period. For some, the period spent with relatives is broken into more than one spell of 14.15 months on average. Nearly half of the individuals also spend time living with their parents (1.62 spells of 4.69 months each), in their own place (1.21 spells of 4.13 months each), and/or living with friends (1.61 spells of 2.39 months each).

A smaller group in typology 3 experiences insecure accommodation and more precarious living circumstances. There are 4.65% who spend time in emergency accommodation (averaging 1 spell of 7 months) and/or sleeping rough (averaging one spell of 1.67 months). Within this group, 9.3% of individuals spend time in youth detention, prison, or on remand, averaging 1.5 spells of 4.33 months per spell.

Typology 4 (parents) represents 17.54% of the cohort. It is characterized by living with parents for an average of 21.04 months in total. However, this time is not necessarily contiguous as there is an average of 2.39 types of accommodation used. Time living with parents comprises 1.4 spells of 14.98 months on average. For many, intervening periods are spent in other forms of accommodation, such as living with friends (32.14%) and with other relatives (22.62%). About half of the group move out of their parent’s home and into their own place; this is typically by the end of the observation period as the cohort ages, with an average of 1.41 spells of 7.18 months each.

Even in a supported sequence such as that evidenced in typology 4, some individuals still use crisis accommodation (2.38%) or sleep rough (4.76%). However, these spells are few and relatively short.

5.3. Characteristics of the individuals within each typology (RQ3)

We now turn our attention to the characteristics of the individuals within each typology. It is important to note that the data are longitudinal; some of these characteristics may change over time. For this reason, we report the average initial attributes for individuals in each typology. For any time-varying characteristics, we report the averages at wave 1 and wave 6 (see ). We focus on the standard socio-demographics of age, gender, marital status, dependants, education, and employment status. These variables are known to be associated with inequality and disadvantage. A common theme in the literature review is the link between inequity, disadvantage and housing insecurity (Elzinga & Liefbroer, Citation2007; Piccarreta & Billari, Citation2007; Pollock, Citation2007). Importantly, we select easily observable variables which are useful from a policy perspective. Finally, we consider the experience of homelessness before our observation window as the literature (May, Citation2000; Sosin et al., Citation1990) notes the importance of housing careers and episodic homelessness. For comparative purposes, column 7 in shows the averages across all typologies and column 8 presents a p value for an ANOVA F-test. This tests if all the coefficients in the row (columns 3–6) are equal. If the p value is significant (p ≤ .05), we can conclude that at least one of the typologies is statistically different from the others in terms of that characteristic. This section will therefore highlight the individual characteristics that statistically differentiate the typologies.

Table 6. Individual characteristics by typology.

Typologies differ in terms of age and gender composition. The average age is 19 (rounded to the nearest whole number) for all typologies except typology 3 (relatives), where it is 18 years old. The share of females in each typology differs, with the lowest share in typology 3 (relatives) and the highest in typology 1 (own home).

Youth with a history of homelessness were most likely to be grouped in typology 2 (churning) and least likely to be found in typology 3 (relatives).

Considering wave 1 characteristics, we see that the youth characteristics across typologies differ according to current partnership status and dependant status (having children under 18 and the presence of these children living in the household). shows that youths in typology 1 (own home) are most likely to have current partners, while those in typology 3 (relatives) are most likely to be single. In terms of dependants, youths in typology 1 (own home) are most likely to have children under the age of 18 who reside within them. Youths in typology 4 (parents) are least likely to have children, and in typology 3 (relatives) youths are least likely to have resident children. We find no statistically significant difference across the typologies in educational or labour force characteristics.

By wave 6 (the end of our observation period), youth characteristics in each typology are mostly unchanged. Typology 1 (own home) are still most likely to be partnered, and typology 3 (relatives) is the least likely, although there is a larger share of youths with partners across all typologies. We also see an increase in the number of youths with children residing and not residing with them. The distribution of those with non-resident children across the typologies does not change however the distribution of resident children does. Youths in typology 1 (own home) remain the most likely to have resident children, but by wave 6 the least likely to have children resident has changed to youths in typology 2 (churning) from typology 3 (relatives).

Given that youth is when individuals finish formal schooling, undertake further, and higher education and have early labour market experiences, it is not surprising that by wave 6 we see changes in education and labour force factors. Youths in typology 3 (relatives) are most likely to have achieved higher levels of education than the other typologies. The lowest incidence of ‘high’ education (Certificate III/IV or above) is observed in typology 2 (churning) youths. We see those most likely to be unemployed are youths in typology 3 (relatives), and the least likely to be unemployed are typology 1 (own home) individuals. For those not in the labour force (NILF), the incidence is highest for youths in typology 1 (own home) and lowest for typology 3 (relatives).

6. Discussion and policy recommendations

The results suggest some important differences across the identified typologies according to the types and durations of accommodations experienced and the socio-economic characteristics of the youths categorized by the typologies. This section provides a descriptive summary of the findings and offers some related policy insights to support housing insecure youths. We highlight where our findings are supported by the literature presented in section 2 and introduce the broader policy-related literature where relevant. It is important to note that we report associations as the methodology does not permit causal inference. Moreover, the sample has significant selection effects that cannot be controlled for. Nevertheless, it is possible to compare and contrast within the sample across the typologies for this group of housing-insecure youths.

6.1. Typology 1: own home

The first typology (own home) is characterized by individuals experiencing the least housing insecurity of all the groups. It is reassuringly the largest in terms of the number of our observations it represents. In regards to the accommodation profile, the majority in this group are seen to be housed in their own place for most of the sample period. Despite evidence of insecure housing circumstances for some individuals, this typology generally represents relatively stable accommodations. This typology highlights the importance of housing affordability. For youth to be able to secure their own homes (either privately owned or renting), there needs to be an affordable housing market with a supply of appropriate housing. As house prices in Australia (and many developed countries) rise, there is a risk of young people who select to live in their own home being unable to achieve this (Johnson et al., Citation2015; Loftus-Farren, Citation2011; McDonald, Citation2014; McChesney, Citation1990). This connects to the literature on structural factors that can drive housing insecurity and homelessness (Early, Citation2004; Johnson et al., Citation2019).

In terms of the individual profiles, there is evidence of ‘upskilling’ in terms of the share of individuals qualified at or above (post-school) Certificate III/IV by the end of the observation period. Further, we can see the rate of unemployment declines for this typology across the observation period. Some of this increased employment may be attributed to individuals leaving school and securing their first job. This typology speaks to the importance of education in securing employment and the need for a healthy labour market to allow youth the security of employment, needed to facilitate secure housing (Clark et al., Citation2003; Pollock, Citation2007).

6.2. Typology 2: churning

The accommodation sequence characteristics for typology 2 are a pattern referred to here as churning. Although only a small proportion of youth in this typology are classified as sleeping rough, many experiences transitory accommodation, such as living with friends and relatives. Housing insecurity of typology 2 is persistent across the window of observation. This is consistent with the characterization of churning through accommodations and has policy significance, implying youth in this group may benefit from support services and interventions.

Beyond accommodation insecurity, we also observe difficulties in relationship formation and relationship stability. Unsurprisingly, relationship formations and breakdowns appear to be associated with changes in housing arrangements (Morton et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the prevalence of youth living with their young children declines across the observation window. Youths with children of their own are a concern due to the possible transmission of intergenerational disadvantage and the increased likelihood of future spells in foster homes and institutions for the children of these youth. Therefore, services must coordinate to design interventions specific to the needs of young parents with a focus on their children. This typology highlights the need for suitable housing for young people with dependents and how disadvantage prevents effective housing choices (Coulter & Van Ham, Citation2013). Further churning is associated with lower levels of education and labour force participation for this typology, suggesting accommodation churning may hinder both educational and economic outcomes (Clark et al., Citation2003). This suggests that improved welfare payment systems may be needed to better support youths who are moving quickly between accommodation types (Stephens et al., Citation2010).

6.3. Typology 3: relatives

This typology is best described as prolonged time with other relatives (non-parents). These are typically the youngest male and single members of the youth cohort. Given the time spent with other relatives, this typology could be characterized as extended family support, although these arrangements remain precarious for some individuals. The family has been recognized as an important buffer against rooflessness in the literature (Johnson et al., Citation2015; CitationTabner, 2010). This typology has the lowest rate of homelessness before the study across our typologies. Long-term spells of accommodation with family can mask underlying precariousness and highlight the hidden housing insecurity that official figures on homelessness do not necessarily record. This is the invisible part of the unmet demand for accommodation. So-called ‘turn away’ figures recorded by private and public housing providers only capture the ‘visible’ part of unmet demand and do not include individuals who need but are not presenting for housing support (Thompson, Citation2007). Many individuals, such as those homeless due to domestic instability or addiction problems, may not present for support services due to stigma. Some may not present as they know that a particular service is already over-utilized and rather not face the disappointment of being turned away, while others may be unable to present as they are suffering from physical and mental ill-health. This typology highlights the importance of social capital and inclusion in preventing rooflessness for these young people (CitationTabner, 2010).

In terms of personal profiles, for youths in this typology, the rate of studying declines, although some of this could be due to schooling completions as the proportion with higher levels of education increases over time. These individuals are also securing employment across the sample period. So despite being housing insecure, these individuals appear to be doing well, and from a policy perspective, this suggests a role for broad familial support services that extend beyond a focus on immediate family (Barker, Citation2012; Pinkerton & Dolan, Citation2007).

6.4. Typology 4: parents

Living with parents might afford some security for individuals in this typology but may depend on the relative stability of their parents’ accommodation arrangements. Indeed, some individuals may not even consider themselves as housing insecure due to having a roof over their heads regardless of the potential precarity of their accommodation and so could be missing from our data. Interestingly, while living with parents during youth is highly prevalent in Australia, it is not amongst our sub-sample of housing insecure and homeless youth. Only 84 individuals sit within this typology. This connects to the literature that includes family issues as a risk factor in youth homelessness and housing insecurity (MacKenzie et al., Citation2016).

Compared to the other typologies, individuals in typology 4 have relatively low partnering and family formation rates. Still, if these individuals have children, they are more likely to reside with them. This suggests that a stable family home for young parents also benefits their children (SmithBattle, Citation2019). Individuals in this typology are the best educated on average across our sample at wave 1 and continue to attain education over time. There are also improvements in the labour market dimension across the observation window as these youths age and enter the labour market. This again speaks to the importance of the association between stable accommodation and positive educational and labour market outcomes.

Summarizing across the typologies, our analysis and discussion have shown that youth experiencing homelessness and housing instability can be categorized into four distinct accommodation profiles. These findings are important for policymakers and social support services. They highlight the importance of relational factors in terms of access to family and relatives to support youth at who are experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity and the dramatic effects of these options not being available or utilized by young people. Investigating the characteristics of youth in the most housing insecure typology (typology 2), we discover that early adulthood partnered relationships and youth parenthood are more common characteristics than they are for youth in the other typologies. There are clear welfare implications for these young people and their children, which warrant further investigation and have policy implications, both now and in the future for these individuals. Consistent with the literature on adult housing careers, we find that the types and durations of accommodation experiences that build a youth’s housing career are correlated with their risk of primary homelessness.

7. Concluding remarks

Using sequence analysis as a tool for understanding patterns in data, we investigate the accommodation sequences of a sample of Australian youth aged 15–24 years who have been identified as homeless or at risk of homelessness. We identify four distinct typologies highlighting the heterogeneity within this group of vulnerable youths. Of note is that not all typologies are necessarily associated with primary homelessness (rooflessness). Although our analysis investigates all four typologies, typology 2 (churning) presents the greatest degree of housing instability and is, therefore, of greatest concern from a societal and policy perspective, especially as this is the second-largest typology in this sample of housing-insecure youth.

The standard policy approach focuses on the pathways into homelessness, such as domestic violence or addiction. However, identifying youth on these pathways is often difficult, given the need for personal information. The fact that individuals may experience multiple pathways at any point in time implies such profiling for service and housing needs may be less than optimal. Therefore, analysing the detailed accommodation sequences of this vulnerable youth group is of critical importance to various stakeholders, including academics, policymakers, town planners, and support agencies.

Overall, our identified typologies suggest that intervention takes different forms for each typology, from affordable and appropriate housing needs to equitable welfare payments and family harmony support. For typology 1 interventions related to housing (appropriate and affordable housing) and labour markets (employment opportunities) need to be top of mind; these structural factors require extensive intervention from governments. For typology 2 the most important aspect is around both building relationships with support services and housing first policies. Here there is a focus on dependent children, so appropriate housing as well as parental and child support is needed. To make housing solutions stick, support/community services and effective welfare payment systems must be used. For typology 3 an integrated approach with social support services from social workers is important to help with extended family relationships. This typology highlights the need for personal connectivity and social inclusion policies. For typology 4, individuals transitioning into independence is most important here, with a focus on the nuclear family through family support services from social workers and community agencies.

While it is known that a multifaceted policy approach is needed to tackle the complexity of youth homelessness, this paper highlights the benefits of identifying typologies that can allow for a targeted policy response. This targeted response can match the right policies to the youths in the typologies that can most benefit them.

Acknowledgements

This paper uses unit record data from Journeys Home: Longitudinal Study of Factors Affecting Housing Stability (Journeys Home). The study was initiated and funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS). The Department of Employment has provided information for use in Journeys Home, managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). However, the findings and views reported in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to DSS, or the Department of Employment, or the Melbourne Institute.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

The Stata code is available for inclusion as supplemental material. The data can be accessed by authorized users following application to the National Centre for Longitudinal Data Dataverse at https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/dataverse/ncld.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Meg Elkins

Meg Elkins is a Senior Lecturer at RMIT University. She is a behavioural and applied economist with research interests in societal and cultural economics. Meg is particularly interested in those on society’s fringes, community wellbeing, and our behavioural information biases. She has published in high-quality economic journals such as Development Studies, Journal of Cultural Economics, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly.

Lisa Farrell

Lisa Farrell is a Professor of Economics at RMIT University. Her research interests lie in the area of Economic Psychology: specifically, in consumer expenditure in relation to risky health behaviours (gambling, smoking, and drinking) and behavioural economics (the effects of psychology on economic outcomes). Lisa has published in high-quality journals which include the American Economic Review (the most prestigious journal in her discipline).

Jane M. Fry

Jane M. Fry is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne. She has over 30 years of experience in the private sector, public sector and academia. She has conducted applied research in various areas of economics, econometrics and marketing, writing reports and publishing in several high-ranking academic journals. Her research interests lie broadly in health, econometrics, and data analysis.

References

- Abdul Rahman, M., Fidel Turner, J. & Elbedour, S. (2015) The US homeless student population: Homeless youth education, review of research classifications and typologies, and the US federal legislative response, Child & Youth Care Forum, 44, pp. 687–709.

- Amore, K., Baker, M. & Howden-Chapman, P. (2011) The ETHOS definition and classification of homelessness: An analysis, European Journal of Homelessness, 5, pp. 19–37.

- Anyadike-Danes, M. & McVicar, D. (2005) You’ll never walk alone: Childhood influences and male career path clusters, Labour Economics, 12, pp. 511–530.

- Anyadike-Danes, M. & McVicar, D. (2010) My brilliant career: Characterising the early labour market trajectories of british women from generation X, Sociological Methods & Research, 38, pp. 482–512.

- Aubry, T., Farrell, S., Hwang, S. W. & Calhoun, M. (2013) Identifying the patterns of emergency shelter stays of single individuals in Canadian cities of different sizes, Housing Studies, 28, pp. 910–927.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2012) 2011 Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness. Cat. no. 2049.0 (Canberra: ABS).

- Barker, J. D. (2012) Social capital, homeless young people and the family, Journal of Youth Studies, 15, pp. 730–743.

- Batterham, D. (2019) Defining “at-risk of homelessness”: Re-connecting causes, mechanisms and risk, Housing, Theory and Society, 36, pp. 1–24.

- Bender, K., Yang, J., Ferguson, K. & Thompson, S. (2015) Experiences and needs of homeless youth with a history of foster care, Children and Youth Services Review, 55, pp. 222–231.

- Benjaminsen, L. & Andrade, S. B. (2015) Testing a typology of homelessness across welfare regimes: Shelter use in Denmark and the USA, Housing Studies, 30, pp. 858–876.

- Bevitt, A., Chigavazira, A., Scutella, R., Tseng, Y. & Watson, N. (2014) Journeys Home User Manual (Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research).

- Bramley, G. & Fitzpatrick, S. (2018) Homelessness in the UK: who is most at risk? Housing Studies, 33, pp. 96–116.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C. (2007) Lost in transition? Labour marketsequences of school-leavers in Europe, European Sociological Review, 23, pp. 409–422.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C., Kohler, U. & Luniak, M. (2006) Sequence analysis with stata, The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 6, pp. 435–460.

- Chamberlain, C. & Johnson, G. (2013) Pathways into adult homelessness, Journal of Sociology, 49, pp. 60–77.

- Chamberlain, C. & MacKenzie, D. (2008) Counting the Homeless 2006 (Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics).

- Clapham, D. (2005) The Meaning of Housing: A Pathways Approach (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Clark, W. A. V., Deurloo, M. C. & Dieleman, F. M. (2003) Housing careers in the United States, 1968–93: Modelling the sequencing of housing states, Urban Studies, 40, pp. 143–160.

- Cobb-Clark, D. & Zhu, A. (2017) Childhood homelessness and adult employment: The role of education, incarceration and welfare receipt, Journal of Population Economics, 30, pp. 893–924.

- Cornwell, B. (2015) Social Sequence Analysis: Methods and Applications (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Coulter, R. & Van Ham, M. (2013) Following people through time: An analysis of individual residential mobility biographies, Housing Studies, 28, pp. 1037–1055.

- Curry, S. R., Morton, M., Matjasko, J. L., Dworsky, A., Samuels, G. M. & Schlueter, D. (2017) Youth homelessness and vulnerability: how does couch surfing fit? American Journal of Community Psychology, 60, pp. 17–24.

- Early, D. (2004) The determinants of homelessness and the targeting of housing assistance, Journal of Urban Economics, 55, pp. 195–214.

- Elkins, M., Farrell, L. & Fry, J. M. (2020) Investigating the relationship between housing insecurity and wellbeing, in: Measuring, Understanding and Improving Wellbeing Among Older People, pp. 41–73 (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Elzinga, C. & Liefbroer, A. (2007) De-standardisation of family-life trajectories of young adults: A cross-national comparison using sequence analysis, European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie, 23, pp. 225–250.

- Farrow, J. A., Deisher, R. W., Brown, R., Kulig, J. W. & Kipke, M. D. (1992) Health and health needs of homeless and runaway youth: a position paper of the society for adolescent medicine, The Journal of Adolescent Health, 13, pp. 717–726.

- Fasang, A. (2010) Retirement: Institutional pathways and individual trajectories in Britain and Germany, Sociological Research Online, 15, pp. 1–16. http://www.socresonline.org.uk/15/2/1.html.

- Fitzpatrick, S. (2000) Young Homeless People (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Fitzpatrick, S., Bramley, G. & Johnsen, S. (2013) Pathways into multiple exclusion homelessness in seven UK cities, Urban Studies, 50, pp. 148–168.

- Flatau, P. (2009) Goals and targets and the national framework on homelessness, Parity, 22, pp. 8–10.

- Flatau, P., Conroy, E., Spooner, C., Edwards, R., Eardley, T. & Forbes, C. (2013) Lifetime and Intergenerational Experiences of Homelessness in Australia, AHURI Final Report No. 200 (Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited). https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/200.

- Flatau, P., Zaretzky, K., Crane, E., Carson, G., Steen, A., Thielking, M. & MacKenzie, D. (2020) The drivers of high health and justice costs among a cohort young homeless people in Australia, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 648–678.

- Fuller, S. (2011). Immigrant Employment Trajectories and Outcomes in the First Settlement Years: A Sequence-Oriented Approach. Working Paper no. 11–07 (Canada: Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Diversity, Metropolis British Columbia).

- Han, S.-K. & Moen, P. (1999) Clocking out: Temporal patterning of retirement, American Journal of Sociology, 105, pp. 191–236.

- Johnson, G. & Chamberlain, C. (2008) From youth to adult homelessness, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 43, pp. 563–582.

- Johnson, G., Scutella, R., Tseng, Y.-P. & Wood, G. (2015) Entries and Exits from Homelessness: A Dynamic Analysis of the Relationship Between Structural Conditions and Individual Characteristics. AHURI Final Report No. 248 (Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited). https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/248.

- Johnson, G., Scutella, R., Tseng, Y.-P. & Wood, G. (2019) How do housing and labour markets affect individual homelessness? Housing Studies, 34, pp. 1089–1116.

- Keane, C. A., Magee, C. A. & Kelly, P. J. (2016) Is there a complex trauma experience typology for australians experiencing extreme social disadvantage and low housing stability? Child Abuse & Neglect, 61, pp. 43–54.

- Kuhn, R. & Culhane, D. P. (1998) Applying cluster analysis to test a typology of homelessness by pattern of shelter utilisation: Results from the analysis of administrative data, American Journal of Community Psychology, 26, pp. 207–232.

- Lee, K. O., Smith, R. & Galster, G. (2017) Subsidised housing and residential trajectories: an application of matched sequence analysis, Housing Policy Debate, 27, pp. 843–874.

- Loftus-Farren, Z. (2011) Tent cities: An interim solution to homelessness and affordable housing shortages in the United States, California Law Review, 99, pp. 1037–1081.

- MacKenzie, D., Flatau, P., Steen, A. & Thielking, M. (2016) The Cost of Youth Homelessness in Australia. Research Briefing 28 April, 2016 (Melbourne: Swinburne University).

- McAllister, W., Lennon, M. C. & Kuang, L. (2011) Rethinking research on forming typologies of homelessness, American Journal of Public Health, 101, pp. 596–601.

- McChesney, K. Y. (1990) Family homelessness: A systemic problem, Journal of Social Issues, 46, pp. 191–205.

- McDonald, S. (2014) Social partnerships addressing affordable housing and homelessness in Australia, International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 7, pp. 218–232.

- McLoughlin, P. J. (2013) Couch surfing on the margins: The reliance on temporary living arrangements as a form of homelessness amongst school-aged home leavers, Journal of Youth Studies, 16, pp. 521–545.

- McVicar, D. & Anyadike-Danes, M. (2002) Predicting successful and unsuccessful transitions from school to work using sequence methods, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society, 165, pp. 317–334.

- Martin, P. & Wiggins, R. (2011) Optimal matching analysis, in: W. P. Vogt & M. Williams (Eds) The SAGE Handbook of Innovation in Social Research Methods, pp. 385–408 (London: SAGE Publications).

- May, J. (2000) Housing histories and homeless careers: A biographical approach, Housing Studies, 15, pp. 613–638.

- Melbourne Institute (2012) Journeys Home Wave 1 Technical Report – Sample, Fieldwork, Response and Weighting, Report prepared for the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (Melbourne: Melbourne Institute).

- Milburn, N. G., Rice, E., Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Mallett, S., Rosenthal, D., Batterham, P., May, S. J., Witkin, A. & Duan, N. (2009) Adolescents exiting homelessness over two years: the risk amplification and abatement model, Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 19, pp. 762–785.

- Morton, M., Dworsky, A., Matjasko, J., Curry, S., Schlueter, D., Chávez, R. & Farrell, A. (2018) Prevalence and correlates of youth homelessness in the United States, The Journal of Adolescent Health, 62, pp. 14–21.

- O’Flaherty, B. (2004) Wrong person and wrong place: For homelessness, the conjunction is what matters, Journal of Housing Economics, 13, pp. 1–15.

- Pearson, W. R. & Miller, W. (1992) Dynamic programming algorithms for biological sequence comparison, Methods in Enzymology, 210, pp. 575–601.

- Piccarreta, R. & Billari, F. C. (2007) Clustering work and family trajectories by using a divisive algorithm, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society, 170, pp. 1061–1078.

- Pinkerton, J. & Dolan, P. (2007) Family support, social capital, resilience and adolescent coping, Child & Family Social Work, 12, pp. 219–228.

- Pollock, G. (2007) Holistic trajectories: A study of combined employment, housing and family careers by using multiple‐sequence analysis, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society, 170, pp. 167–183.

- Pollock, G., Antcliff, V. & Ralphs, R. (2002) Work orders: Analysing employment histories using sequence data, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 5, pp. 91–105.

- Rabinovitch, H., Pauly, B. & Zhao, J. (2016) Assessing emergency shelter patterns to inform community solutions to homelessness, Housing Studies, 31, pp. 984–997.

- Scutella, R., Johnson, G., Moschion, J., Tseng, Y.-P. & Wooden, M. (2013) Understanding lifetime homeless duration: investigating wave 1 findings from the journeys home project, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 48, pp. 83–110.

- SmithBattle, L. (2019) Housing trajectories of teen mothers and their families over 28 years, The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89, pp. 258–267.

- Somerville, P. (2013) Understanding homelessness, Housing, Theory and Society, 30, pp. 384–415.

- Sosin, M., Piliavin, I. & Westerfelt, H. (1990) Toward a longitudinal analysis of homelessness, Journal of Social Issues, 46, pp. 157–174.

- Springer, S. (2000) Homelessness: a proposal for a global definition and classification, Habitat International, 24, pp. 475–484.

- Stephens, M., Fitzpatrick, S., Elsinga, M., Van Steen, G. & Chzhen, Y. (2010) Study on housing exclusion: Welfare policies, housing provision and labour markets. York: European Commission/University of York.

- Stovel, K. & Bolan, M. (2004) Residential trajectories – using optimal alignment to reveal the structure of residential mobility, Sociological Methods & Research, 32, pp. 559–598.

- Tabner, K. (2010) Beyond Homelessness: Developing Positive Social Networks (Edinburgh: Rock Trust).

- Thompson, D. (2007) What do the published figures tell us about homelessness in Australia? Australian Journal of Social Issues, 42, pp. 351–367.

- Toro, P. A., Lesperance, T. M. & Braciszewski, J. M. (2011) The Heterogeneity of Homeless Youth in America: Examining Typologies (Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness).

- United Nations (2009), “Enumeration of Homeless People”, United Nations Economic and Social Council, 18 August 2009; Economic Commission for Europe Conference of European Statisticians, Group of Experts on Population and Housing Censuses, Twelfth Meeting, Geneva, 28–30 October 2009.

- Van Ham, M., Hedman, L., Manley, D., Coulter, R. & Östh, J. (2014) Intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood poverty: An analysis of neighbourhood histories of individuals, Transactions (Institute of British Geographers: 1965), 39, pp. 402–417.

- Wooden, M., Bevitt, A., Chigavazira, A., Greer, N., Johnson, G., Killackey, E., Moschion, J., Scutella, R., Tseng, Y. & Watson, N. (2012) Introducing ‘Journeys Home’, Australian Economic Review, 45, pp. 368–378.