?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The impact of disasters on human well-being extends beyond loss of assets. Asset based compensation approach, usually in monetary form, that the governments adopt for reconstruction of losses of affected persons is marred by challenges in identification of compensable disasters; identification of eligible claimants; identification of compensable losses; and valuation of losses. The largest asset that a household possesses is their house, which suffers major damage. Loss to a house goes beyond the asset itself and affects many dimensions of human well-being. The question this paper examines is, what are the dimensions of well-being, that housing and its location, as resource, have been able to reconstruct for households who were resettled in resettlement colonies of Chennai (India)? Using the framework proposed by Martin Binder, this paper identifies the dimensions of housing well-being and the extent to which these are reconstructed through post-disaster relocation, using the case of households relocated in resettlement colonies in Chennai (India) after disasters since 2004. This paper reveals that housing, and its location contributes to well-being, which is much more than its asset characteristics. Post-disaster resonstruction through relocation and provision of housing must create those opportunities that contribute to well-being. Opportunities for higher income, neighbourhood security, social capital, safety level in the neighbourhood, access to informal/social system for childcare, social and economic associations are significant contributors to housing well-being.

1. Introduction

Disasters impose significant direct and indirect impacts on affected households. The major damage that occurs is to a house (Ahmed, Citation2011). Housing is not merely an asset in possession of a household but it is a resource that enables households to achieve various aspects of their well-being. Hence, the loss to a house goes beyond the asset itself and affects many dimensions of well-being. Emerging literature on the role of assets in building human capabilities argues that the effect of the loss of property due to a disaster extends beyond its asset value to include other dimensions of wellbeing (Rao, Citation2018). In her recent work, Rao (Citation2018) studies the role of property for those who lost their land due to the compulsory acquisition of land by public authorities and finds that functionings of land extend beyond its asset value to include (1) providing a secure means to basic ends; (2) building self-identity; (3) building social capital; (4) building social equity; (5) causing political empowerment; (6) granting power to the owner to take decisions on land matters; (7) contributing to familial wellbeing; (8) creating personal comfort and convenience; and (9) granting psychological wellbeing. Rao (Citation2018) examined landowners’ well-being in their study. Rights to property can be unbundled in many ways. For example, renters may only have the right to use the property and limited right to upgrade and maintain, these still sufficiently contribute to creating many of the functionings identified by Rao (Citation2018). Similarly those living in informal settlements who do not have ownership right to the land, but they do have claim to the space and place where they live (as Bhan, Citation2017a explains) and this creates functionings for households livings in these settlements. Loss of a house or land due to disasters is associated with loss of many of these functionings, including their access to another resource, finance.

Loss of a house also affects the financial position of affected persons. In a study comparing the financial outcomes of residents in areas hit by disasters with those in unaffected communities, (Ratcliffe et al., Citation2020) find that disasters lead to declines in credit scores and mortgage performance, increases in debt arrears, and adverse impact on access to credit card access and debt. They also find that these effects persist or even worsen over time.

Housing and livelihoods are two important resources that impact well-being and both these have location as the common factor. Based on a review of hazard literature that examines post-disaster recovery, Tafti & Tomlinson (Citation2015) argue that affected persons perceive that the housing and livelihood are critical for their recovery. However, most post-disaster recovery programs have focussed on house building though the reasons are often political (Tafti & Tomlinson, Citation2015). The narrow focus on house building ignores the larger role that housing has in contributing to individuals’ capabilities. Moreover, the focus on housing reconstruction in post-disaster recovery programs has mostly benefitted those who were homeowners prior to the disaster, which are the middle-income households. Tafti & Tomlinson (Citation2015) find that in Bam (Iran) and Bhuj (India), the World Bank led reconstruction programs targeted pre-disaster homeowners. In Bhuj, renters and squatters and in Bam, newly female-headed households without land rights were not included in the reconstruction policy (Tafti & Tomlinson, Citation2015). The other focus of disaster recovery programs is on livelihood. The livelihood recovery programs aim at improving resilience of household livelihoods so that food and other basic needs can be met on a sustainable basis. In practice, post-disaster recovery programs approach recovery as a sectoral framework with housing and livelihood as two sectors with minimal overlap, despite that the households plan cross-sectorally for their recovery (Tafti & Tomlinson, Citation2015).

Disasters affect poor people disproportionately as their exposure and vulnerability to these events is much larger while their ability to cope is lower than others (Hallegatte et al., Citation2020). Due to scarcity of land and resulting high land prices in formal markets of urban areas, and economic opportunities particularly in the informal sectors, poor people are pushed to live in riskier areas prone to disasters (Hallegatte et al., Citation2020). These areas take the form of informal settlements which are outside the legal planning regime (Bhan, Citation2017b). A general approach particularly in developing countries to mitigate further exposure to disasters during post-disaster reconstruction has been to relocate households living in informal settlements to purpose-built resettlement colonies usually through forced evictions (Tiwari et al., Citation2022). Examining evictions of informal settlement in Delhi, Bhan (Citation2014) argues that informal settlements are not merely the ‘materiality of housing’ or a ‘planning category’ but rather ‘territorialization of political engagement’ within which low-income households establish their presence in a city. Informal settlements are the attributions of an over-time, incremental, autoconstructed and negotiated existence of low-income households (Bhan, Citation2017a). Eviction from an existing settlement not only demolishes the informal settlement but also transforms the political engagement of its residents (Bhan, Citation2014). This is a significant loss of functioning that Rao (Citation2018) referred to in her paper. On one hand, as Bhan (Citation2013) argues, that the process of resettlement is exclusionary and arbitrary, particularly in determining eligibility, it is also inadequate in reconstructing functionings that households had prior to resettlement (Tiwari & Shukla, Citation2022). Resettlement by public agencies is justified on welfare grounds, as a mean to address poverty and inequality but the question of ‘equality of what’ remains unaddressed. The debate on welfare, as Bhan (Citation2017a) argues, can bestride both equality of outcomes as well as equality of capabilities or opportunity. Capabilities reflect the alternative combination of functionings that a person can achieve from which a person will choose one combination (Carvajal & Ricardo, Citation2016). A functioning is ‘state’ of a person, a set of things they manage to do or be in life (Carvajal & Ricardo, Citation2016). Well-being is the quality of person’s being, based on the functionings that they can choose from. On one hand, the extent to which equality of capabilities is achieved in resettlement colonies for evicted persons is debatable, on the other whether the capabilities achieved in the resettlement colonies equal their previous location is also a matter of investigation (Tiwari & Shukla, Citation2022).

Housing and its location are resources that contribute to a household’s capabilities and hence their well-being. The question that this paper examines is, what are the dimensions of well-being, that housing and its location, as resource, have been able to reconstruct for households who were resettled in resettlement colonies of Chennai (India)? To achieve this, the paper examines the valuable ‘functionings’ of housing (and location where a house is located) for households who were resettled post-disaster. Idenitifying determinants of capabilities associated with housing well-being results from the study emphasize the importance of non-asset dimensions of housing well-being in measuring well-being and disaster losses. Findings emphasize that relocation should be minimised and where necessary should not be detrimental to households’ livelihoods. Housing should respond to the requirements of households and provide an opportunity to ensure social equity and empowerment of women and marginalised.

The research is significant in the current context of newly launched Draft Resettlement and Redevelopment Policy by the state of Tamil Nadu government, which narrowly focusses on resettlement through relocation as one of the main measures. The paper also contributes to the larger objective of designing a resilient compensation and restitution mechanism that can satisfactorily reinstate or reconstruct the basic capabilities of affected households and consequentially facilitate the self-recovery process in a holistic manner.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical framework and methodology for analysing housing wellbeing. Section 3 provides a brief overview of Chennai as the context for this paper, the disasters that affected Chennai, consequent relocation of households to resettlement colonies and a brief literature examining households’ satisfaction with their housing and location. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 presents a discussion on the results and Section 6 concludes the discussion.

2. A theoretical framework and methodology

2.1. Theory

Amartya Sen’s (Citation1987) capability theory has created a (relatively) new debate on the definition of ‘wellbeing’ and on how to measure ‘wellbeing’ using the ‘capability theory’ (Kuklys, Citation2005). Capabilities are personal, and individually formed by converting means and resources that a person have, which include social and cultural characteristics, public/private endowments, commodities, services and norms etc. The capability approach emphasizes that, it is important for people to have choices to enhance their wellbeing aspirations, ‘abilities’ to facilitate realisation of wellbeing and ‘opportunities’ to allow access to and use of abilities and choices (Acharya, Citation2018). A person’s capability is the freedom to choose from the set of feasible functionings. Functioning is what an individual chooses to do or to be, in contrast to a ‘commodity’, which is an instrument enabling her to achieve different functionings (Basu & Lopez-Calva, Citation2011). The transformation of resources into achieved functionings takes place within the capability space comprising individual, local (community, traditions, and environment etc) and structural (laws and regulations) determinants; risks and vulnerabilities that shape people’s choices, abilities, and opportunities that facilitates real capabilities (Frediani, Citation2010).

Most discussions in this section use the same notations as Binder (Citation2014) and Sen (Citation1987).

The well-being framework straddles between two most prominent measures of well-being that come from subjective well-being (SWB) approach and Sen’s capability approach. Measures of SWB directly ask individuals for assessment of their situation. A criticism, however, is that it neglects a person’s opportunities and is also prone to understate individual’s degree of deprivation due to hedonic adaptation (Binder, Citation2014).

The individual’s reported SWB ‘r’ is defined as a function of individual’s true wellbeing u(.).

where

are a range of factors that determine the well-being,

, and

are personal and demographic factors.

is error term that subsumes measurement error and bias. The range of factors that influence SWB,

, range from individual determinants to socio-demographic, economic and institutional.

The criticism with SWB measurement arises from value judgement about which measure to use in welfare assessment, neglect of a person’s opportunities, hedonic adaptation of an individual, and issues of agency (see Binder (Citation2014) for further discussion).

In Sen’s capability approach, individual’s welfare is measured in terms of what they can actually do or be, their capabilities. The capabilities of a person are their state of being or doing, described by a vector of functionings (Kuklys, Citation2005).

where

is a feasible functioning,

is a vector of commodities (resources) out of a set of all possible commodities

.

is mapped into the space of characteristics using function

.

Capabilities are described as:

in the equation above represents ‘capabilities’ or the freedom that a person ‘i’ has in terms of various alternative bundles of feasible functionings,

, given their personal features

(the conversion function of characteristics into functionings) and their command over commodity

(entitlements). In the above equation,

Then, the set gives the overall well-being that a person

can achieve, given their set of achievable beings

and the valuation function

(.).

While the capabilities approach addresses the main cricisms of SWB approach by conceiving welfare as a set of fuunctionings that are objective and independent of individual evaluations (Sen, Citation1987), it has few challenges. These relate to the problem of trading off one functioning with another or understanding their relative importance through allocation of weights has thus far been ignored in the literature (Binder, Citation2014). Also, even though the concept of conversion of resources to functionings is theoretically appealing, measuring conversion factors has been challenging (Brandolini & D’Alessio, Citation2009).

Binder (Citation2014) emphasizes possible amalgamation of the subjective well-being (SWB) approach with the capability approach to partially overcome these problems. They argue that it’s the individual’s evaluation of functionings vector through happiness function that is more relevant for individual’s well-being,

In the context of the present paper, housing as a resource can contribute to capabilities. Fennell et al. (Citation2020) distinguish housing from habitation and argue that housing is a mean (resource) that contributes to habitation, which is ‘the agency to live and fashion one’s life in a suitable abode’. In words of Fennell et al. (Citation2020) “housing is an important dimension that determines an individual’s well-being and it should not be limited to material inputs, but recognised as an important resource that can, through an individual’s agency, deploy ‘conversion factors’ to gain new capabilities”.

Following Binder (Citation2014), this paper identifies determinants of household subjective housing well-being, as a function of a household’s characteristics and other determinants.

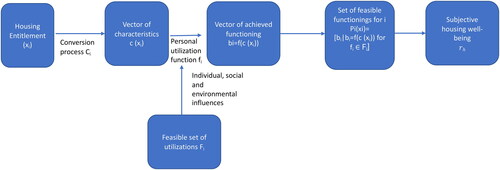

The conceptual framework discussed above is summarised in . Estimated coefficients of the determinants of SWB associated with housing in empirical regressions inform how strongly each satisfaction relevant functioning influences well-being. Based on fieldwork and literature review, Frediani (Citation2019) identify five housing functionings: (1) freedom to expand and individualize; (2) freedom to afford living costs; (3) freedom for a healthy environment; (4) freedom to participate in decision-making; and (5) freedom to maintain social networks. They have also identified indicators for these functionings. The list is a subset of Rao (Citation2018). For list of functionings, in this paper, we expand the work of Rao (Citation2018) by applying it to individuals who previously lived in informal settlements and have been resettled in purpose-built colonies where they have legal right to apartment units. While the legal right to ownership of a house is important, there are other considerations such as neighbourhood, location, which are crucial for achievement of various functionings that an individual has a reason to value.

2.2. Econometric method

To empirically analyse household housing well-being, an econometric estimation of subjective housing well-being function is conducted using a multinomical logit estimator. In literature, multinomial logit estimation have typically been used in models of housing choices (see for example Tu & Goldfinch, Citation1996; Cho, Citation1997; Gluszak, Citation2015; Börsch-supan & Pitkin, Citation1988; Tiwari & Hasegawa, Citation2004). The multinomial logit model has a limitation in that it assumes independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA), which is a strong assumption (see Tu & Goldfinch, Citation1996 for discussion). However, given that the purpose of the paper is to examine satisfaction of households with their houses in resettlement colonies, a multinomial logit model is adopted. Households express their satisfaction on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 as ‘very dissatisfied’ and 5 as ‘very satisfied’.

Household satisfaction with housing is a function of housing characteristics, personal, demographic and social factors.

where

is a vector of housing characteristics,

is a vector of economic, personal and demographic factors.

is the parameter vector that needs to be estimated. The function can be rewritten as:

For j alternatives, the probability function yields a multinomial logit model:

In estimating the multinomial logit model, any choice alternative j can be considered as baseline for comparison with other alternatives. In this article, ‘option 1 and 2—’very dissatisfied’ and ‘moderately dissatisfied’ with house is considered as the baseline as only 10 respondents chose option 1. Estimated multinomial logit model produces J-1 coefficients for each independent variable. The Jth alternative is the reference with which estimated coefficients are compared.

2.3. Data

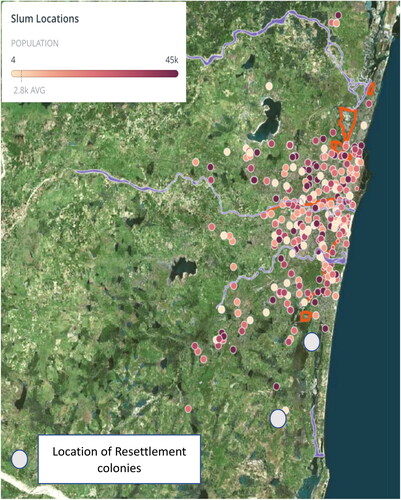

A primary survey with sample size of 458 respondents from Kannagi Nagar, Ezhil Nagar and Perumbakkam was conducted during July–August 2021 (). These are three major resettlement colonies in Chennai. Others being, Semmenchery, Gudapakkam, Navalur, and AIR site (Thiruvottriyur) but not included in this research. The random sampling method was used to identify and interview respondents. The sample selection also ensured that residents relocated from various areas of Chennai, at different periods of time, were included to provide comprehensive understanding of how their satisfaction with their homes have evolved. The survey instrument was developed by the authors in consultation with technical experts from the World Vision India. Thirty enumerators were recruited to conduct the survey. These were Master of Social Welfare students from Petrician College of Arts and Science, Chennai. These students are trained in survey methods and have experience of working in marginalised communities. The survey was conducted under the supervision of technical experts and field staff from World Vision India, academics from Patrician College and the authors. Prior to the survey a training workshop was conducted. A trial survey preceeded before the actual survey to ensure that the survey instrument was fit for purpose and enumerators fully understood the approach. Each survey was conducted by a pair of enumerators (one male and one female) to elimitate any bias. The collected data was transferred daily to a central server and was checked for accuracy and completeness.

Table 1. Details of sample.

2.4. Variables

presents mapping of survey questions to functionings. The mean and standard deviation of variables are also reported.

Table 2. Indicators and descriptive statistics.

The capability approach emphasizes the importance of individual differences in determining well-being. While it is possible to address person specific heterogeneity in panel data, it may not be easy to do so if the data is cross-sectional. (Anand et al., Citation2009) suggest that to allow for this source of heterogeneity in a cross-section data, personality variables may help to make up for the absence of person specific controls. Five variables have been included to account for person specific heterogeneity.

3. Chennai: brief contexual overview

Chennai is a metropolitan city in the state of Tamil Nadu (India) with a population of 8.9 million in 2011 located on the coast of the Bay of Bengal. Spread on a surface of more than 426 Km2, the city is crossed by two main rivers, the Cooum and Adyar. A 4 km long, Buckingham Canal, which runs parallel to the coast connects these two rivers (Hochart, Citation2014).

At least 26% of Chennai’s population lives in slums (Harriss-White et al., Citation2013). presents the map of Chennai with approximate location of slums. Most slums are located between the two rivers. In comparison to non-slum areas, slums have higher concentration of people who are constrained by deprivations such as low caste, low education, informal work, irregular income, limited economic resources, unenforceable rights, and poor health (Harriss-White et al., Citation2013).

Harriss-White et al. (Citation2013) identify certain characteristics of slum households in Chennai. They find that while majority of households worked in informal sector, the diverse livelihood combinations were not common. Eighty percent of households had no asset, and three quarter of households had no savings. Self-employed households had higher income than wage workers. Older workers’ incomes were lower than younger workers. Small households tended to be the poorest than larger households as a large household provided opportunity for income from multiple workers in the household. This highlights that different households will be impacted differently due to disasters.

3.1. History of disasters and losses

Several disasters have affected Chennai affecting people, causing loss of life and assets. In 2004, a tsunami that hit the coastal areas of Tamil Nadu areas including Chennai. In 2015, Chennai was among the most affected regions by the heavy rains that led to severe floods across Tamil Nadu. The city has also been affected by several cyclonic storms, such as Cyclone Vardha in 2016 and Cyclone Gaja in 2018, that have left its people and infrastructure systems stranded (Jain et al., Citation2021).

Patankar (Citation2019) conducted a survey to understand the extent of losses to assets suffered by affected families after 2015 floods. They recorded five types of damage (1) house structure; (2) household assets; (3) appliances; (4) vehicles and (5) work tools. In their study on the extent of damage and recovery process after the floods in 2015, Joerin et al. (Citation2018) find that while physical assets (housing and infrastructure) took too long to be recovered in most affected areas, socio-economic losses (such as income, employment, physical and mental health, nutrition, education, and culture) took even longer to be restored. The impact on the consumption expenditure after floods varied among households depending on their financial constraints. Patnaik et al. (Citation2019) argue that after the flood the consumption expenditure of households in Chennai increased by 32% (largest percentage increase was on health, power, and fuel) but for households who were low income, financially constrained, their consumption expenditure increased marginally. Much of this surge in consumption expenditure was financed through drawing of savings and postponement of purchase of durable goods. Low-income households had less of savings to draw on and their consumption comprised essential commodities whose prices soared. Patankar (Citation2019) find that the compensation paid by public agencies to cover the losses due to flood in Mumbai, Chennai and Puri were inadequate.

3.2. The resettlement to city’s peripheries

Examining land rights and evictions in post-tsunami Sri Lanka, Klein (Citation2007) notes that with increasing land values along the coastline, where private sector seems to be keen for capital investment, tsunami was used as a trigger to evict fishing communities. State of Tamil Nadu and local government agencies in Chennai have used disaster as an extenuating circumstance to displace people from urban settlements and relocate them to city’s peripheries (Mariaselvan & Samuel, Citation2017). The process of peripheral resettlement of inner slums started in 1990s with number of development projects that were undertaken for city improvement (Venkat et al., Citation2015). Implementation of Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS) and integrated storm water drainage project required large tract of land along Buckingham canal resulting in large scale eviction of slums between 2009 and 2015 (CAG, Citation2016). Large scale evictions were also initiated against encroachment of lakes, ponds and other water bodies facilitated by a High Court order and a legislation to protect water bodies in 2007 (Venkat et al., Citation2015).

Natural disasters also provided opportunities for resettling people to peripheral locations. For example, in Chennai, post-2004 Tsunami, coastal communities residing within 200 m of high tide for many years were deemed to be relocated in guise of safety. Households reluctantly consented to these plans as after Tsunami they were struggling to regain their foothold (Mariaselvan & Samuel, Citation2017). In a study of affected persons who were still living in temporary accommodation after 4 years of the Tsunami awaiting relocation, (Raju, Citation2013) finds that majority of fisher-folk were unhappy with the proposed site of relocation as they felt loss of ‘belongingness to the sea’ and distance of relocation site from current location as well as sea. Affected persons had feared that their occupation would be adversely affected due to relocation as the micro-environment of resettlement sites was not conducive as fishing related workplace (Raju, Citation2013). The other dissatisfaction was due to resettlement agencies’ lack of consultation with the affected people, who as fisher-folk are used to taking decisions as community, in the type or design of housing and its environment (Raju, Citation2013). A study examining the post-Tsunami reconstruction in Nagapattinam district in the state of Kerala confirms that the income of fishing community declined after relocation, while the income of non-fishing households had returned to pre-disaster levels even after relocation (Jordan et al., Citation2015). The effect of resettlement on affected persons differed.

A similar pattern of relocation after disaster was repeated in Chennai after 2015 floods. As the 2004 tsunami had enabled the removal of coastal fishing villages to build a coastal highway and resettlement of affected person to purpose-built resettlement colonies in Kannagi Nagar and Semmencherry, the floods were leveraged to evict informal settlements along the Adyar and Cooum rivers to pre-existing and vacant housing units in resettlement colony of Perumbakkam (Jain et al., Citation2021).

Around 25,000 families living in 93 settlements on the banks of Cooum and Adyar rivers who lost their homes were resettled in alternative housing units in the resettlement sites of Kannagi Nagar and Perumbakkam (Peter, Citation2017). Coelho & Raman (Citation2010) demonstrate that another reason for slum clearance and relocation in Chennai is the so called drive for “beautification, restoration and development”.

3.3. Resettlement colonies

Evicted households have been resettled in purpose-built resettlement colonies. Perumbakkam, Kannagi Nagar, and Ezhil Nagar are three major resettlement colonies. shows the location of these resettlement colonies. Kannagi and Ezhil Nagar are close to each other. It is important to note that these resettlement colonies are far from locations of slums which are generally between the two rivers.

3.3.1. Perumbakkam

The relocation site of Perumbakkam consists of 188 high-rise blocks of apartments (Ground + 7) constructed by Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board (TNSCB). The site has 23,864 tenements of which 14,388 were occupied by June 2016 (Peter, Citation2017).

3.3.2. Kannagi Nagar

The housing settlement in Kannagi Nagar, located in Thoraipakkam along Old Mahabalipuram Road, was built by TNSCB since 2000. The site houses 15,656 families on a 40-hectare land parcel. The first relocation to Kannagi Nagar was in 2000 when 3000 houses were constructed under flood alleviation program. An additional 6500 houses were added under the Tenth Finance Commission grant from the central government to state of Tamil Nadu. Between 2002 and 2003, 1620 tenements were constructed through special problem grant from Eleventh Finance Commission of central government. To house relocations due to infrastructure development plan of Chennai Metropolitan Area, 3618 tenements were added in 2004–2005. In 2005 an additional 1271 tenements were built to accommodate fishermen and slum dwellers affected by Tsunami (Hochart, Citation2014).

Typical structure of buildings in Kannagi Nagar are Ground + 1 floor built in 2000 with shared toilets, Ground + 2 floors built in 2004, and Ground + 3 floors built in 2005 with separate room, kitchen, and bathroom. The size of tenements ranges from 195 square feet to 310 square feet (Diwakar & Peter, Citation2016).

3.3.3. Ezhil Nagar

Ezhil Nagar is an annexe of Kannagi Nagar, with 8,048 tenements in 43 building blocks (Diwakar & Peter, Citation2016). Buildings are designed as four storey structures, each comprising 96 to 176 tenements per block (Chitra et al., Citation2015). The size of each tenement is about 390 square feet with a hall, bedroom, kitchen, and attached bathroom with toilet (Chitra et al., Citation2015).

The tenements in resettled colonies have been allocated based on ‘Hire Purchase Scheme’ of TNSCB, which requires residents in Kannagi Nagar to pay a monthly rent of Rs. 150 to Rs. 250 for a period of 20 years before they attain full ownership (Diwakar & Peter, Citation2016). The monthly payment in Ezhil Nagar is Rs. 300. In Perumbakkam, families resettled after 2015 floods pay Rs. 750 per month for their tenement (Peter, Citation2017).

3.4. Household satisfaction with resettlement colonies

Studies that have examined household satisfaction with their houses and neighbourhood in resettlement colonies have found that households resettled in purpose-built resettlement colonies in Kannagi Nagar, Perumbakkam, and Ezhil Nagar are dissatisfied on many counts.

Buildings and tenements suffer from poor design and high density. Perumbakkam has two types of design. Type A design covers 32 blocks each containing 192 tenements. Type B design covers 156 blocks with 96 dwellings in each block. Access to upper floors in Type A buildings is through two staircases and two elevators and Type B buildings through one elevator and two staircases, which are inadequate and in violation of National Building Code (Peter, Citation2017). Layout and design of buildings and tenements lack consideration of livelihood activities of households (Peter, Citation2017).

Jain et al. (Citation2021) argue that Kannagi Nagar and Perumbakkam sites have been developed on wetland which has exacerbated exposure of resettled households to hazards such as seasonal flooding and increased socio- economic and environmental risks.

Social and economic conditions such as job opportunities, access to amenities and impact on household expenditure in Kannagi Nagar have been poor (Hochart, Citation2014). Studies on Kannagi Nagar resettled households suggest that the resettlement has led to job losses and due to lack of employment opportunity many have continued to work in previous locations which is almost 25 Km away (Coelho et al., Citation2012). According to a later report by HLRN (Citation2018), all households in resettlement colonies have experienced loss of livelihood because of the remoteness of location and lack of opportunities for employment nearby. Stigma of living in these locations have negatively affected employment opportunities (HLRN, Citation2018). The loss of employment due to relocation was anticipated but it neither stopped relocation nor led to better connection with resettlement sites. A court case was filed in the Madras High Court on behalf of affected households where a local women’s organization had petitioned for in-situ rehabilitation of Otteri, Chennai citing that relocation to Perumbakkam would affect livelihood of families and disrupt their children’s education but the plea was rejected (ToI, Citation2018). Experiences of residents differ depending on where they have been relocated from. Residents of Ezhil Nagar, who relocated within 2KM, are better off than Kannagi Nagar residents whose previous location was 20-25 KM away (Venkat et al., Citation2015).

The resettled colony is becoming a ghetto of households from marginalised social classes such as scheduled caste (SC), scheduled tribe (ST) and most backward classes (MBC) (Coelho et al., Citation2012). Safety for women and children is a concern that has resulted in many women not going out for work by leaving children at home and many children have dropped out of schools (Jayaseelan & Premraj, Citation2014).

Oft-cited reasons of dissatisfaction in resettlement colonies are poor connectivity to the city, lack of adequate housing, lack of privacy due to the high density, ‘high rise’ typology of buildings, no access infrastructure for people with disabilities, poor access to healthcare facilities, education and inadequate basic services such as water, sanitation, streetlights, transport and burial/cremation ground (HLRN, Citation2018).

Prima facie ‘ownership’ of a durable house in resettlement colonies looks attractive when compared with insecure tenure in slums. However, households had lived in slums for more than 50 years before they were resettled, without requirement of any payment towards their housing. The payment required under ‘Hire and purchase’ scheme, in resettled colonies are high and pose additional burden (Peter, Citation2017). Failure to payment can result in losing tenure and this has forced many households to take high interest loans (Peter, Citation2017).

An unintended consequence of the resettlement has been the disruption of social ties. Concerns of safety, regular incidents of conflict, increased alcoholism and drug use (Jain et al., Citation2021). The repercussions of such marginalisations are very direct and long term (Jain et al., Citation2021).

This provides the context for examining housing well-being of households living in resettlement colonies.

4. Results: estimated housing wellbeing function

A multinomial logistic (MNL) regression is used to predict categorical placement in or the probability of category membership of a housing well-being variable based on multiple independent variables. These independent variables are indicators for functionings

that contribute to housing well-being. The independent variables can be either categorical or continuous. As discussed earlier, respondents report housing satisfaction on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = least satisfied and 5 = fully satisfied). There were only 10 respondents who reported ‘1’ as their housing satisfaction choice. In MNL regression, we have combined responses 1 and 2. Hence four categories have been used in MNL regression. The results are presented in . The following discussion is presented by functionings that contribute to subjective housing well-being. The grouping of functionings is based on Rao (Citation2018)’s functionings for land. It must be highlighted here that some indicators can represent more than one functioning. also presents a ordinary least square estimate with dependent variable as the reported satisfaction and various indicators of functionings as explanatory variables. The intension for presenting OLS estimate is to check the robustness of our estimated model.

Table 3. Multinomial logistic estimate of housing wellbeing function (base Category =2).

4.1. Control over one’s environment: be able to improve the physical attributes of the house as per one’s likings and needs

The indicator that has been used to measure the functioning ‘control over one’s environment’ associated with housing is the percentage share of savings in income. Households who have higher savings have the means to improve their existing housing and living environment. For example, savings allow households to build a roof over open spaces or improve internal attributes of the house to suit their changing needs. The coefficient of share of savings in income in MNL is positive for option 5 implying that households with higher savings have higher probability of being satisfied with their housing. With higher savings households, as expected, would be able to exercise control over their living environment, which enhances their housing wellbeing. Another indicator, total household income, has also been included but this is insignificant.

4.2. Living comfortably in a home

‘Being’ comfortable in house is associated with higher housing wellbeing. Three indicators have been used to measure comfort–floor space, distance of current location of residence from previous location, and number of married couples in house.

A house with larger floor area increases comfort and privacy for its residents. The estimated coefficient for area of house is positive and significant. With base as ‘1 and 2- not satisfied’, increase in area increases housing well-being. Distance of current location from previous location from which a household has been resettled reduces housing well-being due to disruption to the employment and social connections. Poor connectivity of resettled colonies, lack of local job opportunities and increased expenditure on transportation to locations of employment, negatively affect satisfaction with housing. Since the area of units in resettlement colonies are small and can’t be altered, increase in number of married couples per household decreases housing well-being due to reduced privacy that the limited space causes.

4.3. Affiliation: being able to live with others

Being able to live in a house as a large household, could bring positive housing well-being consequential to familial support, particularly for lower income households (Gupta, Citation1999; Jatrana, Citation2007). Alongside offering support for childcare and aged care, large households benefit from diversification of sources of income (Harriss-White et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, living in a large household can negatively impacts housing well-being as it reduces personal space per person (Rehdanz et al., Citation2013). Which of these effects will dominate would depend on the income opportunities for members of the households. In the absence of income opportunities, as in resettlement colonies, the burden on earning members increases with increase in household size. Regarding congestion, the situation is acute in resettlement colonies while housing unit size is small, ranging between 100 and 350 m2. Therefore, an increase in household size reduces the satisfaction with housing as demonstrated by negative and significant coefficient of this variable in .

4.4. Affiliation: being able to live towards others

A house provides space for care and living towards other members of family. Two sets of indicators have been used as measures of being able to live towards others (1) being able to care for other members of family and (2) being able to support them financially. Both are found to enhance satisfaction of living in a house. Three indicators based on survey questions that pertain to ‘satisfaction with current situation on the presence of informal/social support system for children’, ‘overall physical safety of women inside the house’, and ‘physical safety of everyone in the current neighbourhood’, are significant in housing wellbeing function estimate. Satisfaction with support system for children leads to higher satisfaction with house and its microenvironment. Safety for women in the house and safety for everyone in the neighbourhood lead to higher housing wellbeing.

The second group of indicators measure whether households can support family members financially. Two indicators have been used. The first indicator is household savings as a percent of total household income—a higher saving rate is associated with higher satisfaction with housing. As estimated function in indicates, household with higher saving rate have higher probability of being satisfied with their housing. The second indicator is satisfaction with income of other household members. Many households, before relocation, had two or more members of family in the labour force. Often the male household head was the main earning member, while the female adult had supplementary employment. Relocation has reduced work opportunities for female adults (Peter, Citation2017) with significant adverse impact on supplementary income for the family. The indicator ‘satisfaction with income of other household members’ captures household’s functioning, ‘being able to financially support members of household’. Households who are satisfied with income of other members of households, are satisfied with their housing and location, as suggested by the positive and significant coefficient for this variable.

4.5. Familial wellbeing: building interpersonal relationships

Two indicators reflect familial wellbeing associated with housing, ‘household size’ and ‘ability to visit family and friend in the city’. The indicator, ‘household size’ is a proxy for familial well-being derived from living in a family as opposed to living alone (Snell, Citation2017). However, the coefficient of household size is negative and significant, implying that the negative effect of congestion outweighs any positive impact of interpersonal relationship building.

The second indicator is a binary response to the question whether, post-relocation to the resettlement colony, the household has been visiting family and friends in the city. The coefficient is negative for all well-being choices except 5, and insignificant in all cases. A positive coefficient suggests that their current location facilitates social interaction and provides higher wellbeing. A negative coefficient hints at increased travel time and cost of social visits due to long travel distance to and from the main city. In summary, this indicator has not had a significant impact on housing wellbeing.

4.6. Security of physical place: disaster resilience and preparedness

Two indicators have been used to proxy households’ resilience and preparedness to disasters—whether households’ have experience damage to house or contents and self-reported satisfaction with physical protection from disaster in the current house. Households associate greater wellbeing in their current house in the resettlement colony if they have suffered full or partial damage to their homes and contents before being relocated. This is reflected in the positive coefficient of ‘damage to previous house,’ for housing wellbeing choice ‘5’ relative to the base. Also, the coefficient for ‘protection from disaster’ is positive and significant suggesting that households who have a higher perception of protection from disaster arising due to durable nature of their housing unit, report higher housing wellbeing.

4.7. Self-identity in familial identity and status

Literature identifies positive impact of homeownership on the social status and sense of self-identity of the individual and their family (Rao, Citation2018). Housing in resettlement colonies opens the opportunity for households to own their house in the long-runFootnote1. While ownership is important, the issue of identity for resettled households is associated with the location. The negative perception associated with resettlement colonies, however, has resulted in negative identity for households. The location variable is used as an indicator of identity and status associated with housing. With Perumbakkam as base, Ezhil Nagar, and Kannagi Nagar residents are less likely to report higher housing wellbeing, as indicated by negative coefficients of location dummy variables.

4.8. Social equity and empowerment for female

Ownership of house may create economic empowerment and autonomy which may further improve a female’s satisfaction with life in general and their housing. Women in households who have been living in slums prior to relocation face duress and discrimination within an outside home (Azcona et al., Citation2019). If the condition of women improves in resettled colonies, their satisfaction with the housing will be higher. Two indicators have been used to proxy the functioning of social equity and empowerment for female associated with housing. A house with tenure security could empower women, which applies to all households in resettlement colonies. Hence, a dummy variable for response to a question on ‘physical safety of women in house’ is used to proxy social equity and empowerment for female. Households where women have felt physically safe in their homes have reported higher housing wellbeing. A safe neighbourhood for females also enhances satisfaction with housing. Response to the question ‘satisfaction with physical safety for women on roads, bus stops and public transport’ is a proxy for safety in the neighbourhood. The coefficient for this variable in housing wellbeing function is positive and significant. Households who have experienced safe neighbourhood environment for women, have reported higher housing wellbeing.

4.9. Health and psychological wellbeing

Security of a house and neighbourhood contributes positively to the psychological wellbeing of its resident as it ensures safety of life and goods owned by resident. Fears and anxieties associated with housing have negative consequences for health and psychology. A secure house can provide the functioning of psychological wellbeing. Stroebe (Citation2011) find that exposure to induced earthquakes in Netherlands has had negative health consequences especially for those whose homes were damaged repeatedly. This resulted in stress-related health symptoms for affected persons.

Three indicators have been used to measure the functioning of health and psychological wellbeing with a house. The first is the self-reported health statuses. Since there is strong correlation between homeownership and health (Aizawa & Helble, Citation2015), ceteris paribus, respondents who report good health are likely be satisfied with their housing. The positive and significant coefficient confirms the positive relation between health and housing wellbeing.

Respondents who have experienced evacuation due to natural disasters and those who experienced loss of house/assets before being relocated to resettlement colonies, are likely to be more satisfied by their housing in resettlement colonies as the security of tenure and durable structure of house provide psychological comfort against fear of disasters and associated loss of assets. Two variables that capture this aspect are ‘fear of disaster including flood/tsunami’ and ‘fear of loss of house/asset’. The coefficients for these variables are positive and significant for housing wellbeing choices that represent satisfaction.

4.10. Financial security

A house and its location can also be financially advantageous and may result in positive housing wellbeing particularly when the location is convenient for employment purposes. One indicator used to proxy this functioning is the ‘satisfaction from employment’. Households who are satisfied with their employment report higher housing wellbeing. The positive coefficient for housing wellbeing choices that depict satisfaction confirm this. Other variables such as housing debt were not significant in the estimated function. This is because, households have been provided housing through allocation by the public agencies rather than through market mechanism and hence they don’t have loan burden.

4.11. Person specific heterogeneity

Housing wellbeing function include three personality variables that reflects difference in attitude and optimism of respondents.

The first variable is a response to question ‘In taking actions, I put priority on others rather than myself’ (empathetic 1). The second variable is response to question ‘In taking action, I put priority on my family, friends and acquaintances, rather than on my job’ (empathetic 2). These questions relate to personal attitude of a person. Optimism is measured through a response to a question asked to respondents to solicit their views on ‘suffering can lead to personal growth’. All three variables require responses on a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 = almost never true; 2 = rarely true; 3 = occasionally true; 4 = usually true; 5 = almost always true). Three dummy variables are constructed with those reporting positive attitude and optimism (reporting 4 and 5) as 1 and 0, otherwise. Optimists are likely to report higher satisfaction from housing compared to pessimists. While those with empathy towards their family, friends, acquaintances, and others are likely to report lower satisfaction from housing compared to others, if they perceive that housing and neighbourhood environment is not as per their ideals. In addition, two other variables that account for experiences have also been included. Those who have experienced natural or man-made disasters, in general, report lower housing wellbeing than those who have not. The negative effect is stronger for those who experienced natural disasters than those who were relocated due to other reasons.

4.12. Robustness

The OLS estimates also confirm that the variables related to fear of disaster, protection from disaster, satisfaction with informal/social support system for child-care, safety in the neighbourhood and satisfaction with protection from disasters and area of the house are important for satisfaction with housing.

5. Discussion

Disasters affect poor households living in informal settlements disproportionately. Current practices towards designing welfare programmes in India are to provide basic resources to people who are severely deprived so that they have opportunity to live a full life (Acharya, Citation2018). These programmes result in top-down planning, which disregards people’s values, their choices, the process through which they make choices and the extent to which these choices are participatory (Acharya, Citation2018). A mechanism to address disaster vulnerability of households living in informal settlements in Chennai has been to relocate them to purpose-built resettlement colonies. Bhan (Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2017a, Citation2017b) have argued that relocation, as a static event, ignores the immense social and political capital that housheolds have invested in their houses over time and overlooks the failure of legal and formal planning regime. Further, Fennell et al. (Citation2020) argues that habitats that are created through a mass-production template, as in case of resettlement colonies, are rarely inclusive in incorporating features that are socially meaningful to its residents. This comes in stark contrast to the informal settlements from where households have been relocated. Houses, in informal settlements, are not identical because they are outcomes of negotiations of factors of the everyday life. These allow for homeowners’ effective enactment of capabilities out of the scarce resources at hand. An important implication of capabilities perspective is that it favours capitalisation of pre-existing housing structures that intimately and meaningfully relate to the lives of inhabitants over new buildings (Fennell et al., Citation2020).

These results presented provide insights in affected households’ valuation of post disaster reconstruction, which comprised relocation and allocation of durable housing units and associated services and confirm Fennell et al. (Citation2020) arguments. Smith & Frankenberger (Citation2018) argue that besides disaster preparedness and mitigation, factors such as ‘social capital, human capital, exposure to information, asset holdings, livelihood diversity, safety nets, access to markets, and services, women’s empowerment, governance’, and psycho-social capabilities such as ‘aspirations and confidence to adapt’, improve resilience (p. 366). Many of these factors are built over time in settlements from which households are uprooted (Bhan Citation2013).

While relocation in some instances (such as locations of high vulnerability to disasters) is inevitable, it becomes crucial to examine how and what capabilities of households are reconstructed. Sen in his capability approach argues that resources are imperfect indicator of human wellbeing. For an effective post disaster reconstruction approach, an understanding of what people value and what they can attain about the level of reconstruction is necessary. A concept of ‘reasonable value’—much wider and more consultatively developed than simple asset value—is critically important. Whether to generate that value through individual capabilities like Sen’s approach or to consider much broader social economics approaches to housing theorising seems to be an open question at this stage (Obeng-Odoom, Citation2018, Citation2022).

For the present paper, the key concern is to go beyond asset value. In this sense, the functionings achieved through housing and the neighbourhood of resettlement colonies result in housing well-being. Lack of attention to families’ socio-economic conditions, and demographic changes by resettlement agencies in adoption of housing reconstruction policies has benefited some groups of households, while having the opposite effect on others. Fayazi & Lizarralde (Citation2019) argue that resettlement policies that do not account for social structure, do not result in betterment of affected persons. Households, who before the disaster relied on a complex social fabric based on proximity—were adversely affected by policies that allocated them a unit in a residential complex located on city’s fringes.

Post-disaster reconstruction programs need to incorporate characteristics of well-being that must be reconstructed. As identified in this paper, these characteristics go beyond brick and mortar. Housing is merely a resource that provide opportunities for households to be and to do. Housing and its location can provide many functionings for households, subject to personal and social characteristics of households, and this needs to be leveraged in reconstruction programs. Housing and its location are important resources for functionings financial security and control over one’s environment. Households who have been able to secure higher household income are able to improve/modify their living environment. Opportunities for higher household income are not equally distributed for all those who have been resettled. For some households finding suitable employment in the vicinity has been challenging and they have continued to work in older location or in some cases, not work at all. Households who were engaged as fisher-folks or older workers were particularly disadvantaged. Sustenance of income opportunity for other members of households plays an important role in satisfaction with housing and neighbourhood as it allows members to live towards each other and financially support where needed.

A larger household size allows for diversity of employment within household and hence security of income in the event of disaster for low-income households. Household size is also associated with the functionings of being able to live with others, live comfortably and take care of others (affiliation). However, housing type, design and size in resettled colonies pose constraints due to the size of units and ‘high rise’ typology of buildings. Besides the size of house, distance of resettlement colonies from original location is important for comfortable living and maintaining inter-personal relationships as social and economic ties of many households remain associated with original locations. Raju (Citation2013) argue that the built environment must be closely linked to the social aspects of a community. While physical reconstruction is an important component of the post disaster reconstruction process, it is not the only one as recovery is also a social process (Raju, Citation2013). Relocations which weaken social and economic associations, negatively affect housing wellbeing as has been the case for many in resettlement colonies. The cultural inappropriateness of housing constructed for post-disaster resettlement is an issue that has persisted for a long time, and housing reconstruction continues to fail in this respect widely (Ahmed, Citation2011). Beneficiaries react by refusing to inhabit the housing or attempt to adapt in various ways, from modifying the house to dismantling it and selling its components (Ahmed, Citation2011). Lack of opportunities for incrementally adjust housing in resettlement colonies due to design and typology also constrains household agency to achieve valuable functioinings.

Although the importance of beneficiary consultation and participation is widely recognised, it is often done inadequately, which results in cultural misfit of reconstructed housing. Davidson et al. (Citation2007) shows that the participation of beneficiaries in up-front decision-making has positive outcomes in terms of housing decisions and take up. In Indonesia, Ophiyandri et al. (Citation2010) found that a community-based approach could create better housing construction compared to contractor-based approach in terms of quality, accountability, and beneficiaries’ satisfaction. Moreover, as Mukherji (Citation2014) argue, social capital is a useful tool to conceptualize community initiatives in post-disaster situations and dictate collective action. The amount of bonding social capital available within communities, and new resources that the emergence of linking capital networks can bring to communities, can be successfully utilised in port-disaster reconstruction or temporary and permanent housing needs (Mukherji, Citation2014). These aspects were missing from the post-disaster reconstruction process in Chennai.

An important functioning of housing is ‘affiliation—being able to live towards others’. Support system for care of children is important for households as this ensures safety of children and unties adults to be able to take gainful employment. Deep rooted social system where trust among neighbours and support of older members of households persists, care of children is ensured. This, however, becomes challenging when households from diverse background are resettled at one location. Availability of support system for care of children contributes to the functioning of being able to live towards others.

Social equity and empowerment of female is a functioning associated with housing that ensures wellbeing. The resettlement colonies have faced serious concerns regarding safety of women within and in the neighbourhood. Part of the reason has been distrust among households due to the disruption of old social ties as households from various locations and different social backgrounds were relocated. The other reason is the isolation of resettlement colonies which are stigmatised as concentration of poverty.

Poor health and psychological status of individuals who have faced disaster could negatively affect their satisfaction from housing and its neighbourhood in resettlement colonies. The detrimental effect on psychological health, which could arise from fear of disasters or loss of assets could be reduced by not only assisting in rebuilding of assets of those who lost them but also by ensuring that these are protected from future damages. Insurance is one possible way. In Chennai in the aftermath of 2015 floods, households who could afford insurance indicated their willingness to take insurance or invest in disaster protection measures (Patankar, Citation2019). However, for low-income households this may not be the case.

Location is also important as it relates to self-identity. Housing and its location contribute significantly to the functioning associated with self-identity. One of the key problems with the relocation-based post disaster reconstruction in Chennai has been that it led to social stratification which disadvantaged poor and resettlement colonies became ghettos of poor and marginalised (Peter, Citation2017). This not only affected self-identity of households but also reduced their opportunities for employment. Kannagi Nagar and Ezhil Nagar are disadvantaged compared to Perumbakkam, which is located near IT corridor.

6. Conclusion

This research takes motivation from longstanding problems of inadequacy and bias in contemporary post-disaster compensation and restitution mechanisms, which are guided by the asset-based approach to measuring disaster losses and argues that a comprehensive measure of well-being using the ‘capability approach’, provides a better lens to determine what needs to be compensated and restituted. Housing and its location as a resource contributes to a number of capabilities necessary for good quality of life for an individual. Referrring to the well-being that capabilities associated with housing create as housing well-being, the research aims to identify the key determinants of households’ housing well-being that should be the focus of post-disaster compensation/recovery mechanisms. The approach used in this paper follows Binder (Citation2014) who proposes a subjective well-being framework that incorprates Sen’s capability approach. A subjective housing well-being function is empirically estimated to determine indicators of functionings that contribute to households’ well-being.

Asset-based approaches, which focus on measuring and compensating for the loss of assets such as a house using monetary value as a metric, to measuring disaster intensity and losses have long been criticized for the exclusion of nonasset losses such as psychological well-being and social capital, which otherwise are crucial contributors to people’s well-being and thus require satisfactory reconstruction post-disaster. Further criticism of asset-based models is for directing recovery investments toward richer households and regions, and the implicit bias against poor households that otherwise experience larger well-being losses.

This research identifies key determinants of capabilities (such as resources, personal characteristics, and household and societal characteristics) associated with housing well-being in Chennai (India) for target households.

The findings emphasize the importance of non-asset dimensions of housing well-being and challenge the traditional asset-based approaches faces in measuring well-being and disaster losses. Results add to the discussions on building resilient communities and contribute to the bigger objective of designing a resilient compensation or restitution mechanism that can satisfactorily reinstall or reconstruct the basic capabilities of affected households and consequentially facilitate the self-recovery process in a holistic manner.

The results from this paper provide evidence that housing plays a much wider role in household well-being and economic development (Harris & Arku, Citation2006). Where inevitable, the relocation should not be detrimental for households in securing income opportunities. Housing should respond to the requirements of households. It is important to involve community in the process of designing their living environment (Frediani, Citation2010). Results emphasize that during post disaster reconstruction the social systems which are based on trust and care for each other and particularly for children, must not be disrupted. Housing and its location provide an opportunity to ensure social equity and empowerment of women, which not only will have positive impact on the health of women but would also help the overall wellbeing of household. During post disaster reconstruction, if resettlements is necessary, it should not disadvantage households through social stratification or affect their self-identity. This implicitly implies that as far as possible reconstruction should be in-situ or if relocation is necessary, it should not be at a distant location.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Tenements in resettlement colonies are under ‘hire and purchase’ scheme which requires households to pay a rent for 20 years after which the house will be transferred to them as ownership.

References

- Acharya, P. (2018) Building regulations through the capability lens: a safer and inclusive built environment? New Frontiers of the Capability Approach, pp. 505–518 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Ahmed, I. (2011) An overview of post-disaster permanent housing reconstruction in developing countries, International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 2, pp. 148–164.

- Aizawa, T. & Helble, M. (2015) Health and Home Ownership: Findings for the Case of Japan, Tokyo: ADBI Working Paper 525, Asian Development Bank Institute.

- Anand, P., Hunter, G., Carter, I., Dowding, K., Guala, F. & Van Hees, M. (2009) The development of capability indicators, Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 10, pp. 125–152.

- Azcona, G., Bhatt, A. & Valero, S. (2019) Harsh Realities: Marginali ed Women in Cities of the Developing World (New York: Unhabitat).

- Börsch-Supan, A. & Pitkin, J. (1988) On discrete choice models of housing demand, Journal of Urban Economics, 24, pp. 153–172.

- Basu, K. & Lopez-Calva, L. (2011) Functionings and capabilities. Handbook of Social Choice and Welfare: Vol 2, pp. 153–187 (Amsterdam: Elsevier).

- Bhan, G. (2013) Planned illegalities: housing and the ‘failure’ of planning in Delhi: 1947-2010, Economic and Political Weekly, 48, pp. 58–70.

- Bhan, G. (2014) The impoverishment of poverty: reflections on urban citizenship and inequality in contemporary Delhi, Environment and Urbanization, 26, pp. 547–560. volume

- Bhan, G. (2017a) Where is citizenship? Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 37, pp. 463–469. volume

- Bhan, G. (2017b) From the basti to the ‘house’: socio-spatial readings of housing policy in India, Current Sociology, 65, pp. 587–602. volume

- Binder, M. (2014) Subjective well-being capabilities: bridging the gap between the capability approach and subjective well-being research, Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, pp. 1197–1217. volume

- Brandolini, A. & D’Alessio, G. (2009) Measuring well-being in the functioning space. In: E. Chiappero-Martinetti, ed. Debating Global Society—Reach and limits of the capability approach, pp. 91–156 (Milan: Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli).

- CAG. (2016) Resettled life, unsettled state of education! (Chennai: Citizen Consumer and Civic Action Group).

- Carvajal, N. & Ricardo, C. (2016) Capabilities, opportunities and public policies: analysis through simultaneous equation models with latent variables. Thèse de doctorat: Univ. Genève, no. GSEM 36

- Chitra, J., Ravi, P. & Kumar, V. (2015) From Konnur High Road to Ezhil Nagar Part 1 (Chennai: Transparent Cities Network, and Citizen Consumer and Civic Action Group).

- Cho, C. (1997) Joint choice of tenure and dwelling type: a multinomial logit analysis for the city of Chonju, Urban Studies, 34, pp. 1459–1473.

- Coelho, K. & Raman, N. (2010) Salvaging and scapegoating: slum evictions on Chennai’s waterways, Economic and Political Weekly, pp. 19–23.

- Coelho, K., Venkat, T. & Chandrika, R. (2012) The spatial reproduction of urban poverty: labour and livelihoods in a slum resettlement colony, Economic and Political Weekly, pp. 53–63.

- Davidson, C. H., Johnson, C., Lizarralde, G., Dikmen, N. & Sliwinski, A. (2007) Truths and myths about community participation in post-disaster housing projects, Habitat International, 31, pp. 100–115. volume

- Diwakar, G. D. & Peter, V. (2016) Resettlement of urban poor in Chennai, Tamil Nadu: concerns in R, & R Policy and Urban Housing Programme. Journal of Land and Rural Studies, 4, pp. 97–110.

- Fayazi, M. & Lizarralde, G. (2019) The impact of post-disaster housing reconstruction policies on different beneficiary groups: the case of Bam, Iran, in: A. Sagary (Eds) Resettlement Challenges for Displaced Populations and Refugees, pp. 123–140 (Springer International Publishing AG).

- Fennell, S., Royo-Olid, J. & Barac, M. (2020) Tracking the transition from ‘basic needs’ to ‘capabilities’ for human-centred development. in: F. Comim, S. Fennell, & P. A. Anand (Eds) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Frediani, A. (2010) Sen’s capability approach as a framework to the practice of development, Development in Practice, 20, pp. 173–187.

- Frediani, A. (2019) Participatory research methods and the capability approach researching the housing dimensions of squatter upgrading initiatives in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, in: D.A. Clark, M. Biggeri, & A. A. Frediani (Eds) The Capability Approach, Empowerment and Participation (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Gluszak, M. (2015) Multinomial logit model of housing demand in Poland, Real Estate Management and Valuation, pp. 84–89.

- Gupta, R. (1999) The revised caregiver burden scale: a preliminary evaluation, Research on Social Work Practice, 9, pp. 508–520.

- Hallegatte, S., Vogt-Schilb, A., Rozenberg, J., Bangalore, M. & Beaudet, C. (2020) From poverty to disaster and back: a review of the literature, Economics of Disasters and Climate Change, 4, pp. 223–247.

- Harris, R. & Arku, G. (2006) Housing and economic development: the evolution of an idea since 1945, Habitat International, 30, pp. 1007–1017.

- Harriss-White, B., Olsen, W., Vera-Sanso, P. & Suresh, V. (2013) Multiple shocks and slum hosuehold economies in South India, Economy and Society, 42, pp. 398–429.

- HLRN. (2018) Forced evictions in India (New Delhi: Housing and Land Rights Network).

- Hochart, K. (2014) Perspective on slums and resettlement policies in India: the case of Kannagi Nagar resettlement colony (Ecole Dingenieurs Polytechnique).

- Jain, G., Singh, C. & Malladi, T. (2021) (Re)creating disasters: a case of post-disaster resettlements in Chennai, in: Rethinking urban risk and resettlement in the Global South, pp. 269–289 (London: UCL Press).

- Jatrana, S. (2007) Who is minding the kids? Preferences, choices and childcare arrangements of working mothers in India, Social Change, 37, pp. 110–130.

- Jayaseelan, N. & Premraj, F. (2014) The sad story of slum people in resettlement colonies documentations from focus group discussion, Social Science, pp. 20–21.

- Joerin, J., Steinberger, F., Krishnamurthy, R. & Scolobig, A. (2018) Disaster recovery processes: analysing the interplay between communities and authorities in Chennai, India. s.l, Procedia Engineering, 212, pp. 643–650.

- Jordan, E., Javernic-Will, A. & Amadei, B. (2015) Post-disaster reconstruction: lessons from Nagapattinam district, India, Development in Practice, 25, pp. 518–534.

- Klein, N. (2007) The shock doctrine: the rise of disaster capitalism (New York: Metropolitan Books).

- Kuklys, W. (2005) Amartya Sen’s capability approach: Theoretical insights and empirical applications (Berlin: Springer).

- Mariaselvan, E. & Samuel, S. (2017) Urbanisation and settlements: the scope for an inclusive city, Journal of the Madras School of Social Work, pp. 13–22.

- Mukherji, A. (2014) Post-disaster housing recovery: the promise and peril of social capital (Greenville: East Carolina University).

- Ophiyandri, T., Amaratunga, D. & Pathirage, C. (2010) Community based post disaster housing reconstruction: Indonesian perspective (Manchester: University of Salford).

- Obeng-Odoom, F. (2018) Valuing unregistered urban land in ‘Indonesia, Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review, 15, pp. 315–340. no

- Obeng-Odoom, F. (2022) Urban housing analysis and theories of ‘value, Cities, 126, pp. 103714. no

- Patankar, A. (2019) Impacts of natural disasters on households and small businesses in India (Manila: ADB Econiomics Working Paper Series, Asian Development Bank).

- Patnaik, I., Sane, R. & Shah, A. (2019) Chennai 2015: A novel approach to measuring the impact of a natural disaster, New Delhi: National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

- Peter, V. (2017) From deluge to displacement: the impact of post-flood evictions and resettlement in Chennai, New Delhi: Information and Resource Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities, and Housing and Land Rights Network.

- Raju, E. (2013) Housing reconstruction in disaster recovery: a study of fishing communities post-tsunami in Chennai, India, PLoS Currents,

- Rehdanz, K., Welsch, H., Narita, D. & Okubo, T. (2013). Well-being effects of a major negative externality: The case of Fukushima. Working Paper 1855, Keil Institute for the World Economy, Kiel, Germany.

- Rao, J. (2018) Fundamental functionings of landowners: Understanding the relationship between land ownership and wellbeing through the lens of ‘capability’, Land Use Policy, 72, pp. 74–84.

- Ratcliffe, C., Congdon, W., Teles, D., Stanczyk, A. & Martín, C. (2020) From bad to worse: natural disasters and financial health, Journal of Housing Research, 29, pp. S25–S53.

- Sen, A. (1987) Commodities and capabilities (New Delhi: Oxford University Press).

- Smith, L. C. & Frankenberger, T. R. (2018) Does resilience capacity reduce the negative impact of shocks on household food security? Evidence from the 2014 floods in Northern Bangladesh, World Development, 102, pp. 358–376.

- Snell, K. D. M. (2017) The rise of living alone and loneliness in history, Social History, 42, pp. 2–28.

- Stroebe, K. (2011) Chronic disaster impact: the long-term psychological and physical health consequences of housing damage due to induced earthquakes, BMJ Open, pp. 1–9.

- Tafti, M. & Tomlinson, R. (2015) Best practice post-disaster housing and livelihood recovery interventions: winners and losers, International Development Planning Review, 37, pp. 165–185.

- Tiwari, P. & Hasegawa, H. (2004) Demand for housing in Tokyo: a discrete choice analysis, Regional Studies, pp. 27–42.

- Tiwari, P., Shukla, J., Yukutake, N. & Purkayastha, A. (2022) Measuring housing well-being of disaster victims in Japan and India: A capability approach (Property Research Trust).

- Tiwari, P. & Shukla, J. (2022) Post-disaster reconstruction, well-being and sustainable development goals: a conceptual framework, Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 13, pp. 323–332.

- ToI. (2018) Corporation evicts 315 families from Otteri slum. [Online] Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/corporation-evicts-315-families-from-otteri-slum/articleshow/64347933.cms

- Tu, Y. & Goldfinch, J. (1996) A two stage housing choice forecasting model, Urban Studies, 33, pp. 517–537.

- Venkat, T., Subadevan, M. & Kamath, L. (2015) Implementation of JNNURM-BSUP: a case study of the housing sector in Chennai (Mumbai: Centre for Urban Policy and Governance, Tata Institute of Social Sciences).