Abstract

Shared housing in the private rental sector (PRS) is becoming a globally significant household arrangement. However, research indicates that shared housing is associated with problems including financial and housing insecurity. Given the growth of shared housing in the PRS, it is necessary for policy solutions to appropriately address the needs of shared housing renters. This paper aims to investigate the relationship between housing policy and non-commercial shared housing in the PRS – that is, autonomous households in self-contained dwellings – and how this has been conceptualised and examined in academic scholarship thus far. To achieve these aims, we conduct a scoping review on non-commercial shared housing in the PRS. Research illustrates that the reality of shared housing is not accommodated well in existing housing policy systems. We analyse reasons that housing policy may not adapt easily to non-commercial shared housing, and outline the need for further research on policy implications and recommendations about shared housing in the PRS.

Introduction

Shared housing in the private rental sector (PRS) is becoming a significant household arrangement due to unaffordable housing and changing life trajectories. Shared housing is defined here as a household of people who are not all connected through family or romantic relationships; similar definitions are employed by McNamara & Connell (Citation2007, p. 78) and Heath et al. (Citation2018, p. 8). Shared housing has evolved from a burgeoning alternative household arrangement (Baum, Citation1984; Usher & McConnell, Citation1980) to one that is normalised, albeit mostly for adults aged 35 or under (Clark et al., Citation2018a; Heath et al., Citation2018). Shared housing has increased in countries including Australia (McNamara & Connell, Citation2007), China (Wang & Otsuki, Citation2016), Japan (Druta & Ronald, Citation2021), Korea (Cho et al., Citation2019), the UK (Heath et al., Citation2018) and Italy (Bricocoli & Sabatinelli, Citation2016). Generally, sharers’ motivations for entering and staying in shared housing are a combination of saving money and living with others rather than alone (Kenyon & Heath, Citation2001; Maalsen, Citation2019; Wang & Otsuki, Citation2016). Shared dwellings can range from high-quality and spacious to uncomfortably overcrowded, depending on sharers’ incomes and the local availability of housing. However, problems have been identified with shared housing in the PRS.

While it has been well-documented that financial stress and housing insecurity are problems for renters in a variety of household arrangements (McKee et al., Citation2020; Morris et al., Citation2017), broader housing datasets that compare problems across different household types can provide insights into the problems experienced by those in shared housing. For example, in Australia, a 2019 report into the supply of affordable rental housing found that people renting shared housing constituted a significant proportion of the lowest-income households paying severely unaffordable rent (Hulse et al. Citation2019, pp. 55–56). Another 2019 Australian report, on young adults’ housing aspirations, found that 51 per cent of 18–24-year-olds living in shared housing did not have enough money left over for savings or investment after paying housing costs, compared to 35 per cent of those in the same age group living as a family/couple and 40 per cent living as a single person (Parkinson et al., Citation2019, p. 28). These financial pressures are particularly striking given that people often share with the intent of reducing their housing costs (Heath et al., Citation2018; Maalsen, Citation2019; Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2021a). Additionally, shared housing of low cost in desirable locations can be overcrowded, shaped by informal lease conditions that provide limited legal protection or security, and provide tenants little control over who they live with (see e.g. Liang, Citation2018; Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2021a; Ortega-Alcázar & Wilkinson, Citation2021).

While shared housing should not be seen as a problematic arrangement by default, the various problems associated with living in shared housing suggest a need for policy solutions that attend specifically to renters in shared housing, as well as measures that improve conditions for all private renters. The aim of this project is to investigate the relationship between housing policy and shared housing in the PRS, and how this relationship has been conceptualised and examined in academic scholarship thus far. While shared housing in the PRS has attracted more research attention recently, it is unknown how much of this research is focused on policy. In a recent article, Maalsen (Citation2020, p. 109) calls for researchers to start taking shared housing seriously because it has become ‘a long-term housing solution for a wide range of demographics’. More recently, Druta et al. (Citation2021, p. 1199) stated, ‘The absence of literature tackling the socio-cultural context and political economy of shared housing has become conspicuous considering the prevalence of the tenure in urban contexts.’

Shared housing – that is, non-familial housing – exists in many forms and economic arrangements. Shared housing is not homogenous across the world, and in this paper, we are examining a particular ‘type’ of shared housing. The type we focus on involves two or more people sharing a self-contained dwelling and living autonomously, where one or more residents are renting from a private landlord or real estate agent. Kitchen, living, and bathroom spaces may be shared, as well as bedrooms in some overcrowded arrangements. This type of shared housing has been researched in Australia, the UK, the US, parts of Europe and China (see e.g. Heath et al. Citation2018; McNamara & Connell, Citation2007; Bricocoli & Sabatinelli, Citation2016; Wang & Otsuki, Citation2016). We call this ‘non-commercial shared housing’, to differentiate it from commercial shared housing that is created and/or managed by developers and institutions (Ronald et al., Citation2023). Our focus on non-commercial shared housing stems from our concern with the conditions and affordability of the PRS in advanced economies, including how renters use and share existing housing stock that is not designed for non-familial living. Through our definitional distinction, and by limiting the scope of our review, we have excluded arrangements including co-living, purpose-built student accommodation, assisted accommodation, and aged care. Commercial forms of shared housing have recently received increased academic attention (e.g. Bergan et al., Citation2021; Cho et al.,Citation2019; Ronald et al., Citation2023). There are certainly important policy questions surrounding commercial shared housing; as Ronald et al. (Citation2023, p. 20) contend, ‘Shared living has become an increasingly hybrid market-sector shaped by different, and sometimes contradictory regulatory needs and policy objectives.’ However, commercial shared housing arguably differs substantially from the non-commercial type we are focused on. Commercial shared housing can be ‘more akin to a commercial lease and contrasts sharply with the traditional rental lease involving rights and recognition of the rental object as a ‘home’’ (Ronald et al., Citation2023, pp. 4–5).

Therefore, the policy issues facing commercial shared housing are likely different from non-commercial shared housing. Commercial shared housing is often more visible than non-commercial shared housing that occurs within dwellings designed for families. The visibility, along with its newness as a housing form, means that commercial shared housing may receive more focus from regulators. Conversely, non-commercial shared housing may exist more ‘under the radar’ as it sits within the established PRS. Given the complexity and diversity of the shared housing landscape, our process of refining the precise ‘type’ of shared housing under examination is discussed in more detail in the methods section.

To investigate the relationship between non-commercial shared housing in the PRS and housing policy, and the extent to which this has been explored in research, this paper conducts a scoping review of international literature. By comprehensively mapping the field of research, we hope to assist researchers who are also concerned with structural responses to people sharing self-contained dwellings and living autonomously.

Defining ‘housing policy’ is surprisingly not straightforward. Clapham (Citation2018, p. 164) offers a simple definition of ‘any action taken by any government or government agency to influence the processes or outcomes of housing’ and lists seven mechanisms: regulation, direct provision, subsidy, information or guidance, accountability, defining issues and problems, and non-intervention (pp. 165–166). Bengtsson (Citation2018, p. 206) disagrees with this definition, arguing that housing policy includes action by ‘non-state agents that are acting on explicit or implicit delegation from the state.’ Furthermore, should ‘housing policy’ include policy which influences housing regardless of intent, or only policy explicitly designed to influence housing? Burke et al. (Citation2020, p. 28), discussing Australia, argue that the country has ‘very little formal housing policy’, because rental subsidies to welfare recipients are an income support program rather than being grounded in housing, and ‘other measures such as capital gains tax exceptions, negative gearing and planning controls are indirect policies with few specific housing outcomes built into their design.’ These policies certainly ‘influence the processes or outcomes of housing’, as per Clapham’s (Citation2018, p. 164) definition, but they are not ‘formal’ housing policy. More radically, Madden & Marcuse (Citation2016, p. 119) argue that housing policy is ‘an ideological artefact, not a real category’, because the term falsely suggests ‘consistent governmental efforts to solve the housing problem.’

In this paper, for our specific purpose, we adopt Clapham’s (Citation2018, p. 164) definition and apply his seven mechanisms of housing policy to the results of our scoping review. Bearing in mind the contradictory and critical interpretations of ‘housing policy’ by others, we discuss policies that impact housing even if they are not directly designed to do so. This is because, in the case of non-normative housing arrangements – such as shared housing – residents can be affected strongly by a lack of targeted policy (e.g. lack of regulation), or by policy that implicates them through inadvertence rather than design. Additionally, Clapham’s seven mechanisms provide a useful mode of categorisation and help us to see the similarities and differences in policy mechanisms between contexts.

In the remainder of this paper, we outline our methodology, following the five-step process of Arksey & O’Malley (2005). We then present the results of our data charting, and collate, summarise and report the results by drawing on Clapham’s (Citation2018) list of housing policy mechanisms. We conclude with implications and recommendations for research on shared housing in the PRS, as well as implications for housing policy systems more broadly.

Method

While there have previously been narrative literature reviews published on shared housing (Ahrentzen, Citation2003; Clark et al., Citation2018a), there has not yet been a scoping review that methodically surveys the field. Scoping reviews have previously been undertaken in housing-related research to comprehensively explore existing literature (e.g. Anderson & Collins, Citation2014; Franco et al., Citation2021; Humphries & Canham, Citation2021). Such reviews are particularly useful where the extent of research on a topic is initially uncertain (Anderson & Collins, Citation2014, p. 960), as is the case for shared housing and housing policy. Following each of the aforementioned scoping reviews, we based our scoping review on Arksey & O’Malley’s (2005, p. 22) five-step methodology that includes: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. We also drew from the newer scoping review methodology of Levac et al. (Citation2010), and consulted Tricco et al. (Citation2018) and Page et al. (Citation2021) for how to optimise our method and ensure a high level of replicability using the PRISMA framework.

Identifying the research question

We sought to examine the relationship between shared housing and housing policy, and its articulation in the literature, and our research question was therefore, to what extent is policy a key focus of research on shared housing?

Due to the iterative nature of a scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005, p. 22), the research question was then amended after the study selection step (described in more detail, below) to: to what extent is policy a key focus of research on shared housing, where the shared housing constitutes independent accommodation where some or all household members are renters who occupy the dwelling as their principal residence?

Identifying relevant studies

Based on initial reading, we knew that the practice we termed ‘shared housing’ or ‘share housing’ (as it is known in Australia) was called by many different names. We identified search terms that would provide results including the following terms: share-housing; share-house; share housing; share house; sharehousing; sharehouse; shared housing; shared house; share household; shared household; sharing house; sharing housing; sharing household; shared renting; share renting; sharing renting; co-renting; co-renter; co-rental; share accommodation; shared accommodation; sharing accommodation; shared tenancy; sharing tenancy; sharing tenant; co-tenancy; co-tenant; joint tenancy; joint tenant; shared occupancy; sharing occupancy; house sharer; house share; house sharing; housemate; roommate; flatmate.

The search terms were chosen based on the language used in book-length studies of shared living arrangements (e.g. Heath et al., Citation2018; Hemmens et al., Citation1996) and in articles published in housing studies journals. Housing shared by non-relatives has tended to come under the label ‘shared housing’ in the UK (e.g. Heath and Cleaver, Citation2003; Carlsson and Eriksson, Citation2015), while Australians often drop the ‘d’ to write of ‘share housing’ (e.g. McNamara & Connell, Citation2007; Zhang & Gurran, Citation2021). English-language research from countries including Italy, the Netherlands, and Korea also uses the term ‘shared housing’ (e.g. Bricocoli & Sabatinelli, Citation2016; Uyttebrouck et al., Citation2020; Cho et al., Citation2019). The terms ‘shared accommodation’ or ‘shared living’ are often used interchangeably with ‘shared housing’. For our search, it was hoped that further documents that did not use these terms would be found by including terms like ‘joint tenancy’, ‘shared occupancy’, ‘house share’, etc. However, we acknowledge that this list is not comprehensive of all keywords that relate to shared housing; it is biased towards keywords used in English-language housing studies journals.

Study selection

We undertook an advanced search in Scopus and Web of Science core, using the following search terms, looking in the title, abstract or keywords: ‘shar* hous*’, ‘shar* renting’, ‘co-rent*’, ‘shar* accommodation’, ‘shar* tenan*’, ‘co-tenan*’, ‘joint tenan*’, ‘shar* occupancy’, ‘house shar*’, ‘housemate’, ‘roommate’, ‘flatmate’. The date limit was 20 May 2021 and the two databases combined yielded 3,131 results. Non-English-language records and records that were not journal articles and book chapters were eliminated, and then the records were exported into Endnote, where duplicates were removed.

The 1,723 remaining records were then screened for relevance by the first author. Records were removed if irrelevance was clear from the title or abstract (or introductory paragraph where there was no abstract). For example, research primarily concerning couples’ cohabitation and family cohabitation was removed, as well as research from unrelated fields, such as agriculture and computer science. The authorship team discussed and clarified exclusion/inclusion criteria. As discussed in the introduction, we intended to study a particular ‘type’ of shared housing, whereby two or more people share a self-contained dwelling and live autonomously. The exact inclusion and exclusion criteria for this ‘type’ was refined throughout the research process. Through our discussions, a consensus was reached on the following inclusion criteria:

Studies had to be primarily about shared housing (i.e. excluding studies about other issues, such as health outcomes, where shared accommodation was mentioned as a factor).

Studies had to be about shared housing forms that were autonomous and independent (i.e. excluding housing supported and overseen by people with responsibility for the residents – for example college dormitories, aged care, and assisted shared living run by support services).

Studies had to be about shared housing where some or all of the residents were renters (i.e. excluding shared ownership schemes like cooperative housing).

Studies had to be about shared housing that was lived in as a principal residence (i.e. excluding research on shared housing as a crisis response (e.g. couch-surfing) or holiday accommodation (e.g. short-term letting through Airbnb and similar platforms). This category is not clear-cut, as shared housing that is severely overcrowded may be defined as homelessness in some contexts (Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2019, p. 153). However, by ‘principal residence’ we mean that the residents live there on a regular basis.

After the first author continued deleting clearly irrelevant records in line with our criteria, 128 records remained. For these articles, we sourced the full version to validate if they were eligible.Footnote1 Our specific question to determine eligibility was: is this document primarily concerned with shared housing that constitutes independent accommodation where some or all household members are renters who occupy the dwelling as their principal residence? All authors then independently assessed the documents for eligibility. The first author examined all titles, and the other authors examined roughly half the titles each, coding articles as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘maybe’ for inclusion. During the coding process, the authors agreed on more eligibility criteria:

The document must detail empirical research (i.e. excluding non-systematic literature reviews, commentaries, introduction/conclusion chapters and appendices of books, and doctrinal research).

Studies could relate to any aspect of shared housing, including resident experiences, household formation (e.g. choosing housemates), policy, planning, and housing preferences, as long as shared housing that constitutes independent accommodation where some or all household members are renters who occupy the dwelling as their principal residence was a primary or significant focus of the research.

The authors also had a lengthy discussion on whether to include literature on commercial shared housing, like coliving (e.g. Bergan et al., Citation2021). On the one hand, this is privately rented shared housing, and the main form of shared housing that exists in Japan and Korea (Druta & Ronald, Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, the formation and management of the housing is more akin to university campus accommodation than an autonomous household. Eventually, the authors agreed that research on coliving should be excluded because of its commercial nature, and because it does not constitute ‘independent accommodation’ if we define independent as synonymous with autonomous.

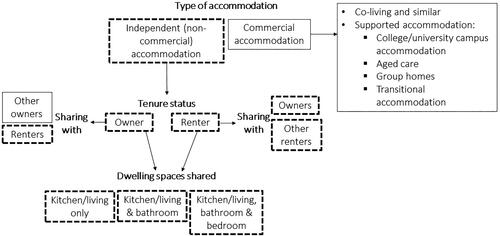

In the course of the discussion process, we designed a ‘typology’ of shared housing experiences (see ), which helped us clarify our focus and which reflects our process of choosing which ‘type’ of shared housing we wanted to examine. This typology was inspired by the previous typology of shared housing constructed by Hemmens et al. (Citation1996). Our typology was refined throughout the research process to eventually reflect our demarcation between commercial and independent (or non-commercial) shared housing.

Figure 1. A typology of shared housing for the scoping review (areas of focus highlighted).

Source: Authors.

With this typology, the bold and dashed outlines indicate our precise area of investigation within shared housing research: independent accommodation where some or all household members are renters who occupy the dwelling as their principal residence. This includes shared housing where residents share kitchen/living spaces and bathrooms, as well as sharing bedrooms, as in overcrowded arrangements.

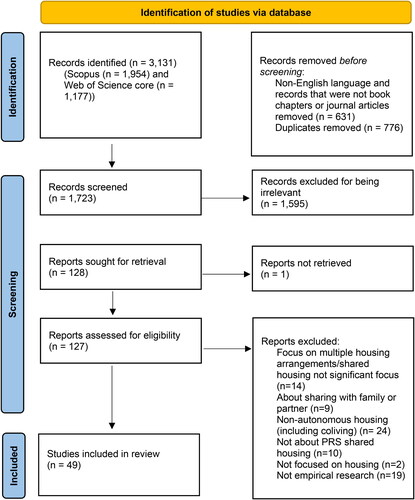

After the first round of coding, there was some disagreement between authors and some records coded as ‘maybe’, and so a second round was conducted following author discussions. After agreement was reached, 78 documents were eliminated on the grounds detailed in the PRISMA diagram (). The remaining 49 documents were included in the data charting phase.

Figure 2. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

Source: Authors, adapted from Page et al. (Citation2021).

Charting the data

The selection of documents was examined to see if policy was a key focus of the research. We defined key focus as being present in the article’s aim and/or results/discussion. The results of this charting process, and the final step of collating, summarising and reporting the results, are captured in the next sections.

Results

The table below lists the final selection of documents, categorised by which featured policy as a key focus and which did not ().

Table 1. Results of scoping review: Final selection of documents, categorised by whether policy is a key focus.

Of the 49 included documents, 17 engaged with policy as a key focus, and of those, the majority (eight) were Australian research. A further four were from the UK. Thirteen of the 17 policy-related studies were published after 2014. The overall results of the scoping review were also mostly recent – pointing to the significant interest in non-commercial shared housing research in recent years. In our next section, we discuss which mechanisms of housing policy were discussed in these 17 documents.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

The 17 documents that featured policy as a key focus discussed different problems and different policy mechanisms in relation to shared housing. These documents were analysed and iteratively grouped, with categories eventually consolidated around the perceived problem articulated by the study authors, and whether authors recommended policy interventions be enacted or existing policy be altered. The groups are not mutually exclusive as some studies identify concurrent problems. The housing policy mechanisms we pinpoint in these documents are drawn from the framework set out by Clapham (Citation2018, pp. 165–166): regulation; direct provision; subsidy; information/guidance; accountability; defining issues and problems; and non-intervention. The following sections set out the problems articulated by study authors, including a discussion of the implicated policy mechanisms, in order to address the paper’s first aim of investigating the relationship between housing policy and non-commercial shared housing in the PRS. We then analyse how study authors have conceptualised this relationship, to address the paper’s second aim.

Problem: Existing policies do not adequately acknowledge shared housing. These documents problematise housing policies that do not sufficiently acknowledge that people live in shared housing. Baum (Citation1984, Citation1986) in Australia, and Schreter & Turner (Citation1986) in the US, call attention to zoning and planning practices that discourage sharing, such as designing houses only for nuclear families and only allowing single-family households to reside in an area. These authors are concerned with changing regulation. Additionally, Verhetsel et al. (Citation2017) call for more development of communal housing for higher education students in Belgium, and Zhang & Gurran (Citation2021), Thorne et al. (Citation1983) and Nasreen & Ruming (Citation2019) in Australia, as well as Bricocoli & Sabatinelli (Citation2016) in Italy, recommend that new housing designs be more adaptable to shared households of adults. These authors therefore recommend direct provision policy interventions through the development of specific housing types. Schreter & Turner (Citation1986, pp. 186–186) additionally recommend subsidy in the form of subsiding homeowners converting their homes and funding shared housing ‘matchmaking’ programs. Bricocoli & Sabatinelli (Citation2016, p. 197) and Nasreen & Ruming (Citation2019, p. 166) also recommend regulation through tenancy contractual tools and services that better suit shared housing, and the former also recommend information of regulation translated into multiple languages. Another author advocating for information is Baum (Citation1986, p. 209), who recommends that shared housing be encouraged and understood through ‘publicity/education programs’, including for young people and for urban planners. Zhang & Gurran (Citation2021, pp. 29–30) differentiate between people sharing due to choice or constraint, and while they recommend direct provision to benefit the former group, they argue that simply producing more housing stock will not assist very low-income people, who need subsidy in the form of social housing or affordable housing with eligibility criteria.

Problem: Policies are needed to fix issues within shared housing. A second group of documents brings to light problems occurring in shared housing arrangements and suggests policy interventions to alleviate them. Nasreen & Ruming (Citation2019, Citation2021a) and Harten (Citation2021) uncover overcrowded shared-room housing inhabited by very low-income tenants in Sydney and Shanghai, respectively, with Harten (Citation2021) additionally identifying a gendered dimension wherein women have more problems finding accommodation. Alam et al. (Citation2022) identify owner-occupiers informally sharing with renters in Australia in ways that create risks for both parties, while Gaddis & Ghoshal (Citation2015) uncover discrimination against Arab-Americans applying to live with roommates. Nasreen & Ruming (Citation2021a) and Harten (Citation2021) recommend direct provision and subsidy, in the form of affordable housing that meets tenants’ needs, and Harten (Citation2021, p. 86) additionally recommends accountability through a ‘gender-conscious planning approach to shared housing’. Nasreen & Ruming (Citation2019) and Gaddis & Ghoshal (Citation2015) recommend regulation, but while the former recommend regulation of tenancies through more flexible leases and complaint resolution services (Nasreen & Ruming Citation2019, p. 166), the latter recommend regulation of online roommate-searching services (e.g. Craigslist) so that users can less easily discriminate on the basis of race (Gaddis & Ghoshal Citation2015, p. 296). Alam et al. (Citation2022) recommend information provision on shared housing and tenancy and building regulations for owner-occupiers, in different languages.

Problem: Current policy responses to shared housing exacerbate problems. A third group of documents criticises the way that existing policies respond to or engage with shared housing. These documents are less about making concrete recommendations and more about raising problems with current policy approaches, specifically the way that governments define issues and problems. Kinton et al. (Citation2018) analyse the process of ‘studentification’ through tenurial transformation and development in a university-adjacent English neighbourhood and argue that current conceptions of studentification in national policy are narrow, not taking into account the diversity of housing that students live in and prefer. Gurran et al. (Citation2021, p. 1729) examine how existing policy and regulations relate to informal dwellings in Australia, and find that policies encouraging lower-cost informal housing to increase affordability may be creating worse living conditions. Finally, Wilkinson & Ortega-Alcázar (Citation2017, Citation2019) and Ortega-Alcázar & Wilkinson (Citation2021) criticise one of the few national policies which explicitly acknowledges shared housing: The UK’s Shared Accommodation Rate (SAR) of Housing Benefit, which limits housing welfare benefits to the cost of a room in a shared house for people under 35 without dependents. The flipside of policies which do not acknowledge that young people live in shared housing (e.g. as in Bricocoli & Sabatinelli, Citation2016; Zhang & Gurran, Citation2021, etc.), the SAR is based on government insistence that it is normal for young people to share, and therefore welfare recipients cannot expect to live in a house of their own (Ortega-Alcázar & Wilkinson, Citation2021). In this way, the UK Government enacts defining issues and problems through the process of subsidy.

Conceptualising the relationship between housing policy and non-commercial shared housing in the PRS

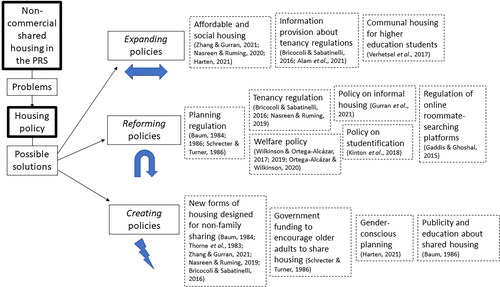

The second aim of this paper was to examine how the relationship between housing policy and non-commercial shared housing in the PRS has been conceptualised within academic scholarship. Building on the previous section’s categorisation, we synthesise the documents’ approaches to housing policy in relation to shared housing. The study authors conceptualise housing policy as comprising tools that could alleviate the problems related to shared housing. However, there is variation in the authors’ approach to current policy, as authors variously suggest: expanding policies that already exist; reforming or overhauling current policies; or creating new policies. , below, illustrates how the collection of documents conceptualise housing policy in relation to shared housing as something to be expanded, reformed, or created to address problems. The policies that were discussed in the previous section and categorised by Clapham’s (Citation2018) framework are clustered by commonality in the figure.

Figure 3. Conceptual relationship between non-commercial shared housing in the PRS and housing policy.

As demonstrates, a wide variety of policy mechanisms and fields are implicated in the document authors’ concerns regarding shared housing in the private rental sector. This variety of policies also affects multiple populations, including higher education students, young welfare recipients, women, and older adults. Far from being a niche topic with a single policy implication, this analysis shows that non-commercial shared housing in the private rental sector has broad-ranging practical implications across multiple geographic contexts.

Discussion

Implications for further research and policymaking

Non-commercial shared housing may be formal or informal, and it can be ignored, tolerated, or regulated against by the state. Within our document selection, we found multiple concerns raised in relation to affordable housing, housing conditions, and improving tenancy regulation. Overall, the results suggest that existing policy does not often ‘fit’ with the reality of living in shared housing, and that new policy solutions are needed. Why existing policy is often inadequate for addressing or improving shared housing in the PRS may be explained by several factors. First, it is important to note that shared housing remains a small proportion of households, compared to couple and family households, in most countries. Where shared housing is ignored, it may be because it is viewed by policymakers as simply too small to be of concern. Secondly, and related to this, is the notion that shared housing is ‘only temporary’ for sharers. Within many housing regimes, homeownership is the cultural ideal, an endpoint that signifies attaining adulthood and respect (Arundel & Ronald, Citation2021; Konings et al., Citation2021; Bobek et al., Citation2021). Shared housing in the PRS may be considered as reserved for young people and/or experienced for a short period, and therefore not in need of policy attention. However, people may live in shared housing for longer, or (re)enter it later in life in response to financial or social needs (Maalsen, Citation2020; Schreter and Turner, Citation1986). Of the policies discussed in our collection of documents, some ignore shared housing and some push shared housing on certain groups; however, both these policy types embody the logic that shared housing is a temporary detour on the road to ‘proper’ housing. The UK’s Shared Accommodation Rate policymakers, by decreeing that welfare recipients under 35 can only rent a room in a shared household, cast shared housing as a normal part of young adults’ housing pathways, and disputed that welfare recipients could expect to live alone (Wilkinson & Ortega-Alcázar, Citation2017). When shared housing in the PRS is positioned as short-term and unimportant compared to the ideal of homeownership, opportunities to improve it are closed off. As Nasreen & Ruming (Citation2019, p. 166) note, ‘while the individual might move on, shared accommodation is likely to remain, creating ongoing challenges for local housing and planning policy.’ Therefore, policies should not just ensure that people who live in shared housing move on to other household forms, but address the housing system itself and the place of shared housing within.

The analysis of the policy-focused documents also demonstrated that informal shared housing is more likely to receive policy attention than formalised (non-commercial) shared housing, due to the contravening of occupancy laws or building and planning regulations. The documents that discuss informal shared housing and policy (Alam et al., Citation2022; Gurran et al., Citation2021; Harten, Citation2021; Nasreen & Ruming Citation2019, Citation2021a) explore how these housing forms exist alongside legal regulations regarding overcrowding, space usage, and leases. Informal shared housing may require special attention where tenants experience health and safety risks from sharing rooms or even beds (Harten, Citation2021; Gurran et al., Citation2021; Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2021a). However, enforcement action may negatively impact tenants, even though the landlord would likely be held legally responsible. This is acknowledged by Gurran et al. (Citation2021), who note that uncovering illegal housing may mean relocating vulnerable tenants who lack other options. Policy interventions therefore need to focus on providing safe housing for tenants and addressing the underlying reasons why people live in risky shared housing (Zhang & Gurran, Citation2021; Gurran et al., Citation2021; Harten, Citation2021).

Our results suggest that within housing regimes, shared housing in the PRS should not be treated with a blanket approach, due its diversity of conditions. Zhang & Gurran (Citation2021, p. 29) advocate for two sets of policy interventions: one for people sharing housing by choice, and one for those sharing out of necessity. However, other research has suggested that it is not always easy to differentiate sharing by choice and by constraint (Ahrentzen, Citation2003; Bricocoli & Sabatinelli, Citation2016; Kenyon & Heath, Citation2001). Therefore, another option is that policy interventions make a distinction between shared housing that presents health and safety risks to tenants, and shared housing which does not. This does not necessarily match with a formal/informal binary. While informal forms of shared housing can be risky and harmful, shared housing encouraged by the state is also not guaranteed to be good-quality, as Ortega-Alcázar & Wilkinson’s (Citation2021) work explores. Shared housing in the PRS is entangled with policy interventions relating to housing supply, welfare receipt, planning, zoning, and policy for the aged and the young. If policymakers do not adequately understand shared housing – why it is necessary for some and preferred by others, who uses it, and how – then policies will continue to fall short, or worse, exacerbate people’s vulnerabilities (Wilkinson & Ortega-Alcázar, Citation2019). There is a clear need for shared housing researchers to continue examining the ‘socio-cultural context and political economy of shared housing’ (Druta et al. Citation2021, p. 1199), given the increase in shared housing and the problems already illustrated by researchers across countries. In the context of ‘Generation Rent’ (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017), and the financialisation of housing creating sweeping crises in housing accessibility, shared housing is arguably growing in importance. But shared housing needs careful treatment as a subject of policy, and so more researchers must listen to tenants and bring their experiences to light, and critically evaluate current and potential policy measures for their impact on tenants.

Study limitations

One of the challenges we encountered during our study selection was the multiplicity of terms and definitions for shared housing. Some records, which seemed promising from the abstract, used ‘shared housing’ to mean housing shared between non-married romantic partners, for example. A limitation of this research is that we could only capture documents that used the terms we put in our query string. For example, through our search process we did not find any documents about sub-divided units/flats, which may be considered a type of shared housing common in Hong Kong (see e.g. Huang, Citation2017). Additionally, we only used English-language search terms and eliminated results not in English, meaning our scoping review does not cover shared housing research in other languages. Future research would benefit from cross-country and cross-discipline collaboration so that authors can compile the diverse terms used in their locations/disciplines to obtain a comprehensive collection.

Another limitation is that we decided to only include journal articles and book chapters. Grey literature such as reports for government may provide more detailed policy discussions. This is a fruitful avenue for subsequent research to explore.

As demonstrated by the rapid increase in relevant literature since 2014, shared housing has fast become a hot topic of housing, urban, and sociological research. In the time since our scoping search was conducted, several notable new works on shared housing have been published, including a special issue of Social & Cultural Geography on ‘urban singles and shared housing’. While shared housing research is constantly evolving, the foundational arguments and findings presented here, that non-commercial shared housing needs greater attention in relation to housing policy, will likely remain relevant over the long-term.

Conclusion

This scoping review investigated the relationship between non-commercial shared housing in the PRS and housing policy, and how this relationship has been the focus of academic scholarship thus far. We found that a limited number of our final document selection (17 out 49) were policy-related research, although the proportion greatly increased in the last several years. This selection of literature demonstrates that non-commercial shared housing is not accommodated well in existing housing policy systems. The lack of integration between housing policy and shared housing may be because housing regimes that valorise homeownership position shared housing in the PRS as a temporary domain of young people, and therefore unimportant or not worth intervening in. However, there is more frequent policy attention on informal shared housing that breaches occupancy or building regulations. It is not only informal shared housing that can be problematic, however, as more formalised non-commercial shared housing can also be a source of problems for tenants. We therefore recommend further research on non-commercial shared housing in the PRS deeply investigate policy mechanisms – whether researchers advocate for expanding, reforming, or creating housing policy to address problems.

Noting that some researchers’ policy recommendations from the 1980s are echoed nearly 40 years later – for example, Baum (Citation1984) and Nasreen & Ruming (Citation2019) both recommend that dwelling designs in Australia should consider shared households – it is clear that researchers can only do so much if governments do not listen or will not act. For this reason, we strongly encourage a systematic review of the grey literature on non-commercial shared housing in the PRS, to draw out the problems and recommendations being conveyed to policymakers. Policymakers must pay attention to changes in household forms and arrangements, and their implications for policy and regulation, rather than persist in path-dependent policymaking (see Bengtsson & Ruonavaara, Citation2010). Shared households are less common than family households, but their unique characteristics may mean they need particular attention, in order to create better outcomes for a growing number of people.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zoë Goodall

Zoë Goodall is a Research Associate and PhD candidate in the Centre for Urban Transitions at Swinburne University of Technology. Zoë’s research interests include shared housing in the private rental sector, tenancy law, housing justice for renters, and gendered housing issues.

Wendy Stone

Professor Wendy Stone is Academic Leader of the Housing Futures Research Program within the Centre for Urban Transitions and was Director of the AHURI Swinburne Research Centre (2013 - 2020). Wendy holds numerous Category 1 competitive ARC and AHURI research grants and industry awards. She is leader of the annual national housing scholars’ symposium, publishes for academic and community audiences, is engaged in policy development and debate in housing issues, is a regular media contributor and supervises higher degree research students.

Kay Cook

Professor Kay Cook is a Professor in Sociology and the Associate Dean of Research for the School of Social Sciences, Media, Film and Education at Swinburne University of Technology. Her work explores how new and developing social policies such as welfare-to-work, society security, child support and childcare policies, transform relationships between individuals, families and the state.

Notes

1 One record could not be retrieved, but we were able to access issues from subsequent years to ascertain it was a trade magazine and therefore would not contain empirical research.

References

- Aeby, G. & Heath, S. (2020) Post break-up housing pathways of young adults in England in light of family and friendship-based support, Journal of Youth Studies, 23, pp. 1381–1395.

- Ahrentzen, S. (2003) Double indemnity or double delight? The health consequences of shared housing and “doubling up”, Journal of Social Issues, 59, pp. 547–568.

- Alam, A., Minca, C. & Farid Uddin, K. (2022) Risks and informality in owner-occupied shared housing: to let, or not to let?, International Journal of Housing Policy, 22, pp. 59–82.

- Anderson, J. T. & Collins, D. (2014) Prevalence and causes of urban homelessness among indigenous peoples: a three-country scoping review, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 959–976.

- Arksey, H. & ‘O’Malley, L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, pp. 19–32.

- Arundel, R. & Ronald, R. (2021) The false promise of homeownership: Homeowner societies in an era of declining access and rising inequality, Urban Studies, 58, pp. 1120–1140.

- Baum, F. E. (1984) Shared housing: Cheap, sometimes enjoyable, but contrary to norms, Australian Planner, 22, pp. 13–15.

- Baum, F. (1986) Shared housing - Making alternative life-styles work, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 21, pp. 197–212.

- Bengtsson, B. & Ruonavaara, H. (2010) Introduction to the special issue: Path dependence in housing, Housing, Theory, and Society, 27, pp. 193–203.

- Bengtsson, B. (2018) Theoretical perspectives vs. realities of policy-making, Housing, Theory and Society, 35, pp. 205–210.

- Bergan, T. L., Gorman-Murray, A. & Power, E. R. (2021) Coliving housing: Home cultures of precarity for the new creative class, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1204–1222.

- Bobek, A., Pembroke, S. & Wickham, J. (2021) Living in precarious housing: non-standard employment and housing careers of young professionals in Ireland, Housing Studies, 36, pp. 1364–1387.

- Bricocoli, M. & Sabatinelli, S. (2016) House sharing amongst young adults in the context of mediterranean welfare: the case of milan, International Journal of Housing Policy, 16, pp. 184–200.

- Burke, T., Nygaard, C. & Ralston, L. (2020) Australian home ownership: past reflections, future directions, AHURI Final Report, 328, pp. 1–84.

- Carlsson, M. & Eriksson, S. (2015) Ethnic discrimination in the london market for shared housing, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41, pp. 1276–1301.

- Cho, G. H., Woo, A. & Kim, J. (2019) Shared housing as a potential resource for community building, Cities, 87, pp. 30–38.

- Clapham, D. (2018) Housing theory, housing research and housing policy, Housing, Theory and Society, 35, pp. 163–177.

- Clark, V. & Tuffin, K. (2015) Choosing housemates and justifying age, gender, and ethnic discrimination, Australian Journal of Psychology, 67, pp. 20–28.

- Clark, V., Tuffin, K. & Bowker, N. (2020) Managing conflict in shared housing for young adults, New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 49, pp. 4–13.

- Clark, V., Tuffin, K., Bowker, N. & Frewin, K. (2019) Rosters: Freedom, responsibility, and co-operation in young adult shared households, Australian Journal of Psychology, 71, pp. 232–240.

- Clark, V., Tuffin, K., Frewin, K. & Bowker, N. (2017) Shared housing among young adults: Avoiding complications in domestic relationships, Journal of Youth Studies, 20, pp. 1191–1207.

- Clark, V., Tuffin, K., Bowker, N. & Frewin, K. (2018a) A fine balance: a review of shared housing among young adults, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12, pp. e12415.

- Clark, V., Tuffin, K., Frewin, K. & Bowker, N. (2018b) Housemate desirability and understanding the social dynamics of shared living, Qualitative Psychology, 5, pp. 26–40.

- Diehl, C., Andorfer, V. A., Khoudja, Y. & Krause, K. (2013) Not in my kitchen? Ethnic discrimination and discrimination intentions in shared housing among university students in Germany, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39, pp. 1679–1697.

- Druta, O., Ronald, R. & Heath, S. (2021) Urban singles and shared housing, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1195–1203.

- Druta, O. & Ronald, R. (2021) Living alone together in Tokyo share houses, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1223–1240.

- Edwards, P. K., Jones, J. A. & Edwards, J. N. (1986) The social demography of shared housing, Journal of the Australian Population Association, 3, pp. 130–143.

- Franco, B. B., Randle, J., Crutchlow, L., Heng, J., Afzal, A., Heckman, G. A. & Boscart, V. (2021) Push and pull factors surrounding older adults’ relocation to supportive housing: a scoping review, Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 40, pp. 263–281.

- Gaddis, S. M. & Ghoshal, R. (2015) Arab American housing discrimination, ethnic competition, and the contact hypothesis, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 660, pp. 282–299.

- Gaddis, S. M. & Ghoshal, R. (2020) Searching for a roommate: a correspondence audit examining racial/ethnic and immigrant discrimination among millennials, Socius, 6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120972287

- Gorman-Murray, A. (2015) Twentysomethings and twentagers: Subjectivities, spaces and young men at home, Gender, Place and Culture, 22, pp. 422–439.

- Gurran, N., Pill, M. & Maalsen, S. (2021) Hidden homes? Uncovering sydney’s informal housing market, Urban Studies, 58, pp. 1712–1731.

- Harten, J. G. (2021) Housing single women: Gender in china’s shared rental housing market, Journal of the American Planning Association, 87, pp. 85–100.

- Heath, S. (2004) Peer-shared households, quasi-communes and neo-tribes, Current Sociology, 52, pp. 161–179.

- Heath, S. & Cleaver, E. (2003) Shared housing, grown-up style. In Young, Free and Single? Twenty-somethings and Household Change, pp. 89–108 (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Heath, S. & Cleaver, E. (2004) Mapping the spatial in shared household life: A missed opportunity? in: C. Knowles & P. Sweetman (Eds) Picturing the Social Landscape: Visual Methods and the Sociological Imagination, pp. 65–78 (New York: Routledge).

- Heath, S., Davies, K., Edwards, G. & Scicluna, R. (2018) Shared Housing, Shared Lives: Everyday Experiences Across the Lifecourse (London: Routledge).

- Heath, S. & Kenyon, L. (2018) Young adults and shared household living: Achieving independence through the (re)negotiation of peer relationships, in: H. Helve & C. Wallace (Eds) Youth, Citizenship and Empowerment, pp. 110–126 (London: Routledge).

- Heath, S. & Scicluna, R. (2020) Putting up (with) the paying guest: Negotiating hospitality and the boundaries of the commercial home in private lodging arrangements, Families, Relationships and Societies, 9, pp. 399–415.

- Hemmens, G. C., Hoch, C. & Carp, J. (1996) Introduction, in: G. C. Hemmens, C. Hoch, & J. Carp (Eds) Under One Roof: Issues and Innovations in Shared Housing, pp. 1–16 (Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press).

- Hoolachan, J., McKee, K., Moore, T. & Soaita, A. M. (2017) ‘Generation rent’ and the ability to ‘settle down’: Economic and geographical variation in young people’s housing transitions, Journal of Youth Studies, 20, pp. 63–78.

- Huang, Y. (2017) A study of Sub-divided units (SDUs) in Hong Kong rental market, Habitat International, 62, pp. 43–50.

- Hulse, K., Reynolds, M., Nygaard, C., Parkinson, S. & Yates, J. (2019) The supply of affordable private rental housing in Australian cities: Short-term and longer-term changes, AHURI Final Report, 323, pp. 1–122.

- Humphries, J. & Canham, S. L. (2021) Conceptualizing the shelter and housing needs and solutions of homeless older adults, Housing Studies, 36, pp. 157–179.

- Kenyon, E. & Heath, S. (2001) Choosing this life: Narratives of choice amongst house sharers, Housing Studies, 16, pp. 619–635.

- Kim, J., Woo, A. & Cho, G. H. (2020) Is shared housing a viable economic and social housing option for young adults?: willingness to pay for shared housing in Seoul, Cities, 102, pp. 102732.

- Kinton, C., Smith, D. P., Harrison, J. & Culora, A. (2018) New frontiers of studentification: the commodification of student housing as a driver of urban change, The Geographical Journal, 184, pp. 242–254.

- Konings, M., Adkins, L., Bryant, G., Maalsen, S. & Troy, L. (2021) Lock-in and lock-out: COVID-19 and the dynamics of the asset economy, Journal of Australian Political Economy, 87, pp. 20–47.

- Lepore, S. J., Evans, G. W. & Schneider, M. L. (1992) Role of control and social support in explaining the stress of hassles and crowding, Environment and Behavior, 24, pp. 795–811.

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H. & O’Brien, K. K. (2010) Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology, Implementation Science : IS, 5, pp. 69.

- Liang, L. (2018) No room for respectability: Boundary work in interaction at a shanghai rental, Symbolic Interaction, 41, pp. 185–209.

- Maalsen, S. (2019) I cannot afford to live alone in this city and I enjoy the company of others: Why people are share housing in sydney, Australian Geographer, 50, pp. 315–332.

- Maalsen, S. (2020) Generation share’: Digitalized geographies of shared housing, Social & Cultural Geography, 21, pp. 105–113.

- Madden, D. & Marcuse, P. (2016) In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis (London & New York: Verso).

- McKee, K., Soaita, A. M. & Hoolachan, J. (2020) ‘Generation rent’ and the emotions of private renting: Self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1468–1487.

- McNamara, S. & Connell, J. (2007) Homeward bound? Searching for home in inner sydney’s share houses, Australian Geographer, 38, pp. 71–91.

- Morris, A., Hulse, K. & Pawson, H. (2017) Long-term private renters: Perceptions of security and insecurity, Journal of Sociology, 53, pp. 653–669.

- Nasreen, Z. & Ruming, K. (2019) Room sharing in sydney: a complex mix of affordability, overcrowding and profit maximisation, Urban Policy and Research, 37, pp. 151–169.

- Nasreen, Z. & Ruming, K. J. (2021a) Informality, the marginalised and regulatory inadequacies: a case study of tenants’ experiences of shared room housing in sydney, Australia, International Journal of Housing Policy, 21, pp. 220–246.

- Nasreen, Z. & Ruming, K. J. (2021b) Shared room housing and home: Unpacking the home-making practices of shared room tenants in sydney, Australia, Housing, Theory and Society, 38, pp. 152–172.

- Natalier, K. (2003) I’m not his wife’: Doing gender and doing housework in the absence of women, Journal of Sociology, 39, pp. 253–269.

- Ortega-Alcázar, I. & Wilkinson, E. (2021) ‘I felt trapped’: Young women’s experiences of shared housing in austerity britain, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1291–1306.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … Moher, D. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. British Medical Journal (International ed.), 372.

- Parkinson, S., James, A. & Liu, E. (2021) Luck and leaps of faith: How the digital informal economy transforms the geographies of shared renting in Australia, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1274–1290.

- Parkinson, S., Rowley, S., Stone, W., James, A., Spinney, A. & Reynolds, M. (2019) Young australians and the housing aspirations gap, AHURI Final Report, 318, pp. 1–125.

- Pritchard, D. C. (1983) The art of matchmaking: a case study in shared housing, The Gerontologist, 23, pp. 174–179.

- Pynoos, J., Hamburger, L. & June, A. (1990) Supportive relationships in shared housing, Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 6, pp. 1–24.

- Ronald, R., Schijf, P. & Donovan, K. (2023) The institutionalization of shared rental housing and commercial co-living, Housing Studies, pp. 1–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2023.2176830

- Sawert, T. (2020) Understanding the mechanisms of ethnic discrimination: a field experiment on discrimination against turks, syrians and americans in the Berlin shared housing market, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46, pp. 3937–3954.

- Schreter, C. (1984) Residents of shared housing, Social Thought, 10, pp. 30–38.

- Schreter, C. A. & Turner, L. A. (1986) Sharing and subdividing private market housing, The Gerontologist, 26, pp. 181–186.

- Thorne, R., Munro-Clark, M. & Ferguson, R. (1983) The not-so-small household minorities: Singles and sharers in sydney, Architectural Science Review, 26, pp. 71–75.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., Godfrey, C. M., Macdonald, M. T., Langlois, E. V., Soares-Weiser, K., Moriarty, J., Clifford, T., Tunçalp, Ö. & Straus, S. E. (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation, Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, pp. 467–473.

- Tuffin, K. & Clark, V. (2016) Discrimination and potential housemates with mental or substance abuse problems, Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 35, pp. 98–118.

- Usher, C. E. & McConnell, S. R. (1980) House-sharing - A way to intimacy?, Alternative Lifestyles, 3, pp. 149–166.

- Uyttebrouck, C., Van Bueren, E. & Teller, J. (2020) Shared housing for students and young professionals: Evolution of a market in need of regulation, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 35, pp. 1017–1035. doi: 10.1007/s10901-020-09778-w

- Verhetsel, A., Kessels, R., Zijlstra, T. & Van Bavel, M. (2017) Housing preferences among students: Collective housing versus individual accommodations? A stated preference study in antwerp (Belgium), Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32, pp. 449–470.

- Wang, Y. & Otsuki, T. (2016) A study on house sharing in China’s young generation-based on a questionnaire survey and case studies in beijing, Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 15, pp. 17–24.

- Wilkinson, E. & Ortega-Alcázar, I. (2019) Stranger danger? The intersectional impacts of shared housing on young people’s health & wellbeing, Health & Place, 60, pp. 102191.

- Wilkinson, E. & Ortega-AlcÁzar, I. (2017) A home of one’s own? Housing welfare for ‘young adults’ in times of austerity, Critical Social Policy, 37, pp. 329–347.

- Yu, X. & Zhang, X. (2021) The impact of trust on the willingness of co-tenancy behavior: Evidence from China, Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, pp. 365–383.

- Zhang, Y. & Gurran, N. (2021) Understanding the share housing sector: a geography of group housing supply in metropolitan sydney, Urban Policy and Research, 39, pp. 16–32.