Abstract

Low-income earners and others facing housing market barriers have long sought to save costs by sharing. Potentially a release valve in constrained markets, the share sector is poorly understood due to the difficulty of tracing informal negotiations between cohabiting households. However, the rise of online accommodation platforms opens new opportunities to view these hidden arrangements while also propelling new practices under the broader financialisation of housing and ‘platformisation’ of daily life. With reference to Sydney, Australia, one of the world’s most expensive housing markets, we use platform data to investigate the contemporary share housing sector, using listings placed by people both seeking and offering shared accommodation via Flatmates.com.au. Our study contributes to emerging literature at the intersection between informal housing markets and platformisation, revealing a complex rental sector where costs may be discounted but are not necessarily affordable for lower income earners unable to access more appropriate or secure alternatives.

Introduction

Living in a share house, ‘flatting’, or bunking with ‘roomies’, has long been regarded an important rite of passage for younger adults exiting the family home, particularly amongst the middle class (Jones, Citation1987; Kenyon & Heath Citation2001). Low-income earners needing to save money by ‘doubling up’ with others have also entered into various share or lodging arrangements, considered a form of precarious housing equivalent to homelessness (Leopold, Citation2016). Whether a lifestyle choice or economic necessity, these informal sharing arrangements have attracted limited research and policy attention in part because they are difficult to detect or monitor (Boeing & Waddell, Citation2017). Nonetheless, the rising barriers to home-ownership and a shortage of affordable rental supply under the broader financialisation of housing and reforms to the welfare state, mean that sharing is likely to play an increasingly important role (Ronald et al., Citation2023). Within these contexts, new sharing practices and informal markets for shared accommodation are also emerging, often facilitated by online platforms.

Such platforms – from general websites for goods, services and residential accommodation, such as Criagslist.com; to those dedicated to real estate (e.g. Zillow.com), or short-term rentals (Airbnb.com) – have had profound impacts across the housing sector and beyond (Ferreri and Sanyal Citation2022; Fields & Rogers, Citation2021). They also offer insights into aspects of the housing system that have traditionally been difficult to research or monitor (Maalsen & Gurran, Citation2022). This paper seeks to contribute to this evolving research at the intersection between informal shared housing markets and platformisation, using Sydney, Australia’s largest city, as a case study. Employing data extracted from the leading share housing platform ‘Flatmates.com.au’ (hereafter ‘Flatmates’), we examine advertisements placed by individuals seeking or offering share accommodation in Sydney during the month of August 2020 (a total of 6611 listings). This was an interesting time in Sydney’s rental housing market with a potential increase in demand for new rental tenancies triggered by the ending of general COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, although this was offset by a lack of international migration as the nation’s borders remained closed. We ask: a) who is seeking and offering share accommodation, and why; b) how the supply of share housing vacancies matches express demand; and c) what is the role of the (platform mediated) share housing sector within the wider private rental market? Our findings reveal a complex segment of the private rental sector, where costs may be discounted relative to the formal market but are not necessarily affordable for the lower-income earners unable to access more appropriate or secure alternatives.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, we situate our study at the nexus between research on informal housing in the so-called Global North and platformisation, as the starting point for understanding changing rental practices and the contemporary share housing sector. We then explain our research approach and introduce the case of Sydney. Third, we present our analysis of demand and supply of share housing advertised via the Flatmates platform, examining the quantum of demand as well as the characteristics and requirements of those seeking accommodation. Finally, we consider the role of platform enabled sharing in offering discounted accommodation for lower income earners within a wider rental market devoid of appropriate and affordable alternatives.

Housing informality

There is rising research interest in the role of informal housing practices and markets within high-cost cities and regions (Durst & Wegmann, Citation2017; Ferreri & Sanyal, Citation2022; Harris, Citation2018). No longer considered solely a so-called ‘Global South’ phenomenon; ‘informal’ housing includes dwellings or tenures which avoid or violate government regulations, typically meaning less amenity and or security for residents (Gurran et al., Citation2022). Rather than a binary separation, scholars have highlighted the complex mutual interdependencies and intersections between these ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ realms. First coined by economists to describe the range of enterprises, labor and transactions that exist within the ‘shadow’ of formal markets (Portes et al., Citation1989), informal housing includes unauthorised or illegal dwelling construction as well as unregulated or negotiated forms of tenure. From backyard ‘granny flats’ to share homes or rooms, these informal dwellings and tenures occur within and are produced by the broader ‘formal’ housing system in complex ways. For instance, states define ‘formal’ systems of housing production and property, prosecuting or selectively tolerating dwellings or tenures which deviate from established regulations (Durst & Wegmann, Citation2017). More fundamentally, states may contribute to the conditions which bring about informality, where regulations are overly restrictive or where there is inadequate assistance for the poor (Harris, Citation2018).

Within such settings, informal housing practices become an economic necessity for some and an opportunity for others. As research on illegal construction in Europe (Chiodelli, Citation2019) and informal rental practices in the UK reveals (Ferreri & Sanyal, Citation2022), informality is not confined to the very poor. Rather, wealthy elites may have greater capacity to bypass established rules. The global proliferation of unauthorised short-term rental properties enabled by platforms such as Airbnb highlights how informal rental practices may increase financial returns to landlords, driving higher rents across the wider market (Ferreri & Sanyal, Citation2018; Wachsmuth & Weisler, Citation2018). Within this context of unmet housing need, people are more ready to accept poorer quality housing and or more precarious forms of rental tenure (Parkinson et al., Citation2022). Even so, informal housing is not necessarily ‘affordable’ or appropriate for those on low-incomes (Harris, Citation2018). Savings gained by offering lower standards of amenity or security are not always passed on by landlords who will generally seek to maximise rental returns in high demand markets, for instance, by renting properties by the room rather than as a whole dwelling (Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2019).

Sharing as informal housing practice

Sharing residential accommodation with others – either as part of a group household or as an individual sharing some communal facilities – has become an increasingly important housing practice in many parts of the world (Bricocoli & Sabatinelli, Citation2016; Bobek et al., 2020; Uyttebrouck et al., Citation2020). To date understudied by researchers and policy makers, perhaps due to a lack of ready data (Ronald et al., Citation2023), new studies examine share housing practices in the UK and Europe (Maslova Citation2022), Australia (Maalsen, Citation2019), China (Harten, Citation2021), Japan (Druta & Ronald, Citation2021), and South Korea (Kim et al., Citation2020).

Different types of share accommodation

The existing research highlights the many forms of share accommodation beyond that typically associated with group households formed by young adults leaving the family home for study or career (Kenyon and Heath Citation2001). In countries like the US, Canada, Australia, and the UK, single room occupancy ‘boarding’ or ‘rooming’ houses have long catered to lower income adults, and particularly single men (Freeman, Citation2017; Goodman et al., Citation2013; Sullivan & Burke, Citation2013). Called ‘houses in multiple occupation’ in the UK, these premises were often larger homes specially converted to provide individual room rentals, typically with shared bathroom and kitchen facilities (Pader, 2002). Subject to defined regulatory requirements around occupancy, overcrowding and fire risk; over time, gentrification pressures have seen the loss of many of these distinctive accommodation types, which continue to occupy uncertain legal status in many jurisdictions (Thorpe, Citation2021). More recently, studies have shown emerging forms of institutionally provided share housing such as special purpose student accommodation and types of ‘co-living’ developments for working professionals (Hilder et al., Citation2018; Ronald et al., Citation2023).

A different form of sharing within residential accommodation includes two or more households opting to ‘double up’ within a single dwelling to save on their housing costs (Ahrentzen, Citation2003; Vacha & Marin, Citation1993). Driven by income constraints and necessity, involuntary doubling up is considered a precursor to homelessness (Wright et al., Citation1998). When a household rents a room within their own home to an individual or couple, this is more commonly described as a ‘lodging’ arrangement (Alam et al., Citation2022). These various types of share accommodation are associated with different dynamics of power and autonomy within share households and between residents and landlords.

We summarise these different types of share accommodation in with particular reference to Australia; distinguishing between boarding or rooming houses managed by an absent landlord or agent who rents rooms or share rooms to individual tenants (with or without a formal residential lease); lodging arrangements where the property owner rents space in their own home to a tenant/s (Alam et al., Citation2022); a subletting/head tenant arrangement, where one tenant’s name is on the lease and rent collected from other members of the dwelling (Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2019); as well as the conventionally understood share household with all members sharing the rent, whether or not they are named on the residential lease (). Overall, these different forms of sharing are associated with a range of formal and informal arrangements within the private rental sector (Parkinson et al., Citation2022); targeting different demographic cohorts and offered at different price points.

Table 1. Forms of share housing in Australia.

The experiences of share housing occupants

Previous research on home-sharing has focused on anthropological accounts of the social relationships and notions of home amongst sharers (Kenyon & Heath, Citation2001; Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2021), often concentrating on young adults as the primary group engaged in share household formation (McNamara & Connell, Citation2007). The ways in which sharing experiences are mediated and impacted by digital platforms has also been examined by more recent research (Maalsen, Citation2020; Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2022). Experiences are likely to depend on who is sharing and why – those who share by choice are likely to have a better experience and report higher satisfaction than those who have no other options in the housing market (Kendig, Citation1984).

Another stream of research looks at reasons for sharing. Demographic change, such as declining rates of marriage or partnership and nuclear families mean that more people will share in the future (Maalsen, Citation2019). Similarly, barriers to entering the formal rental market – such as high rental costs, the need for a bond payment or a proven rental history, may force low-income tenants and newly arrived migrants to seek accommodation in the share sector (Maslova Citation2022; Usman et al., Citation2021).

Social dynamics and relationships underpin share households (Health et al., Citation2018). These relationships are required to navigate difficult terrain, such as the financial management of rent, food and utility payments, arrangements for chores and furniture, and the balance between privacy and socialising with housemates and their wider circles. Unsurprisingly, tenants often seek housemates who have similar lifestyles, age, life stages, values, and expectations (Clark et al., Citation2018; Maalsen & Gurran, Citation2022). Yet tensions can arise even when sharers are of the same ethnic and cultural milieu. As reflected by the ambivalence towards live-in lodgers described by owner occupiers who rent rooms in their own home, there is an added complexity to these hybrid social and economic relationships within a domestic setting (Alam et al., Citation2022). The relational nature of share housing may be particularly problematic during times of crisis. A survey of share housing residents in Melbourne found their experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic was made complex by the lack of privacy and space during extended lockdown periods; social conflicts and fears about housemates’ behaviour and safety (Raynor & Panza, Citation2021).

Online platforms and the demand and supply of share housing

Social networks played a large part in the formation of traditional share households (McNamara & Connell, Citation2007). Prior to the arrival of platforms such as ‘Craigslist’ – one of the first platforms to digitise classified advertisements; share accommodation vacancies were primarily advertised in weekly newspapers, local noticeboards, or via word of mouth. The search ‘costs’ for individuals seeking appropriate accommodation – accessing a finite number of weekly advertisements, telephone calling prospective flatmates or landlords, traveling to inspect the accommodation; knowledge of the locality and its facilities – represented a natural limit on the geographic search area (Maalsen & Gurran, Citation2022).

Digital platforms have almost eliminated such constraints. Part of the broader rise of ‘PropTech’ (Shaw, Citation2020), such platforms mobilise powerful digital algorithms to match the specific demands of users – rental price range; location; accommodation features – with available supply. Expanding through a self-reinforcing network of users (those offering and seeking residential accommodation), platforms are able to expose and release spare capacity across the housing system, opening new financial opportunities for owners or renters seeking additional income towards their own housing costs (Sarkar & Gurran, 2017). Given the inherent ‘stickiness’ of new housing supply, in these ways platforms may represent a welcome technological innovation serving lower income renters and aspiring home-owners, while supporting more efficient use of the housing system and opening new research opportunities.

Unfortunately, emerging research evidence suggests that platformisation actually tends to reinforce biases in the housing market due to algorithmic processing of search results; and the automation of functions such as tenant screening or management (Porter et al., Citation2019). Online data often perpetuates information asymmetries and data gaps as well, because of the quality and nature of information uploaded by users (Boeing et al., Citation2021). Close analysis of online housing data in the US found differences in the length and nature of free text listings descriptions corresponded with spatial markets, with more amenities described in higher value areas while lower value markets included punitive references to the characteristics of potential tenants (Boeing et al., Citation2021). An attempt to ‘ground-truth’ online listings for Shanghai’s informal rental market (beds in group rental houses), found that advertisements were likely to exaggerate property amenities, underquote rental costs, and disguise geographic locations by offering proximate rather than actual addresses, leading the authors to conclude that the rental advertisements functioned more as a means of identifying potential tenants than as a vehicle for communicating accurate information about the accommodation (Harten et al., Citation2021). For researchers, however, online data sources can offer a more holistic understanding of the housing market, particularly informally organised sectors such as share accommodation (Boeing & Waddell, Citation2017).

Sydney’s share rental market

Sydney is Australia’s largest city, with over five million residents (ABS, Citation2021). Population growth has been buoyant at almost 2% over the past decade, driven mainly by international migration, until the national border closures in response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. A chronic shortage of affordable rental units, has meant that almost half of Sydney’s low-income earners experience rental stress (Parkinson et al., Citation2018), leading to an increase in the number of people sharing in group households as well as rising rates of overcrowding, particularly in inner ring suburbs (Nasreen and Ruming Citation2019). Around 4% of Sydney’s households are classified as ‘group’ (unrelated adults living together); rising to 10.8% in inner Sydney (ABS, Citation2021).

Methods and data

The data sources for this study were scraped from flatmates.com.auFootnote1 advertised in August 2020. Extending previous analyses (Nasreen & Ruming Citation2019; Zhang & Gurran Citation2021), we developed a new data set of those seeking accommodation in addition to advertisements of accommodation vacancies. We compiled two new data sets: housing advertised by landlords/flatmates seeking people to move into established share accommodation (n = 3570), and advertisements placed by people seeking share accommodation (n = 3041). Listings placed by people seeking share accommodation include user supplied information on gender, age and employment status, as well as their preferred locations, rental budget, and required length of stay. By contrast, advertisements offering accommodation identify the location, characteristics of the shared dwelling, duration of the vacancy, and the rental cost. In addition to these data categories, listings contain free text descriptions about the person seeking accommodation or the household offering a vacancy. In some cases, these descriptions offer insights into the reasons for seeking or offering accommodation, or other personal characteristics of individuals or their households.

Flatmates listings were extracted from the online sites and geocoded at the suburban scale using official suburb boundaries defined by the Australian Statistical Geography Standards (ABS, Citation2016). Shared housing supply was calculated by counting accommodation listings in each suburb where landlords or existing tenants were seeking new tenants. The total supply of share accommodation may be higher than the total number of listings, since some listings offer more than one room, or offer a shared room to more than one tenant. We then mapped this supply at the suburbs level. To understand the spatial geography of shared housing demand, we analysed the suburbFootnote2 preferences nominated by those seeking accommodation in Sydney. Many people nominated several preferred suburbs (mostly within the same sub region), so we used the first preference to avoid double counting. We then compared the spatial distribution of listings with the first preferences of those seeking accommodation.

Census data on group households and rental dwellings was used to understand and compare shared housing supply with the wider private rental sector. We also compared our data sets with established indicators of ‘formal’ housing market activity (NSW Fair Trading, Citation2020), extracted from new rental tenancy leases and associated ‘bond’ payments lodged with the NSW state government and ‘formal’ vacancy rates for the same period (SQM Research 2020). This provided a way of comparing share rents with rents in the ‘formal’ rental market. It also provided a way of estimating the contribution of platform enabled share housing supply to overall rental vacancies in Sydney.

Our data has inevitable limitations in that we focus on a single share housing platform, not capturing advertisements for shared housing listed on other sites such as Facebook or equivalent. We also recognise the potential for inaccuracies about accommodation quality, location, and costs, associated with user supplied data as outlined above. Overall, however, these inaccuracies are not of a nature or scale as to significantly distort the findings.

Who is seeking and offering share accommodation?

To answer our first research question, we examined listings placed by people seeking share accommodation. Since these listings advertised people themselves, we were able to extract and quantify to establish base data on gender, age, and employment status. We then analysed the advertisements offering vacancies in existing homes. These listings focused on property characteristics, but we were able to ascertain some information about existing household residents, their own preferences for flatmates of particular demographic criteria, and or the nature of the rental arrangement being offered. To ascertain why accommodation was being sought or offered, we were limited to qualitative analysis of listings, across both data sets.

Those seeking share accommodation

Consistent with existing research on share households, those advertising for share accommodation via the Flatmates platform were more likely to be younger adults, aged up to 30 years (). However, around 130 advertisements were placed by people over the age of 50, indicating that demand for share accommodation stretches across the age cohorts.

Table 2. Characteristics of people seeking share accommodation via Flatmates, August 2020.

The gender of those seeking share accommodation was fairly even, with slightly more women identified. Most people seeking accommodation were single but 187 advertisements were placed by couples or ‘groups’. Thus, the total number of people seeking share accommodation via these listings (3233) exceeded the total number of advertisements (3041). Again, the presence of couples and groups in our sample highlights the diversity of people seeking share accommodation and implies a severe shortage of accommodation that is affordable or available even for dual-income households. Similarly, more than 60% of those seeking accommodation indicated that they were in full-time employment, again challenging traditional notions of share households as young adults and tertiary students ().

There are likely to be added challenges faced by specific cohort groups seeking share accommodation, as with the rental housing market more widely (MacDonald et al., Citation2016). For instance, people of minority ethnic groups, those who identify as LGBTQI, or parents with children may all face additional challenges in accessing accommodation in the share housing sector, as may people on low incomes and or in receipt of government benefits. People with pets are also likely to face additional barriers in finding rental accommodation overall and share housing in particular. Smokers may also experience additional barriers in securing place in a share home. Often these characteristics intersect to compound the challenges faced by people seeking share housing.

Parents with children accounted for 35 listings. Poignantly, they expressed awareness of the added difficulties they faced in accessing shared accommodation, as evidenced by this advertisement appealing for potential ‘roomies’ to accept their child.

‘I have devoted my last 2 years of my life to raise my beautiful son and I know some roomies don’t like living with children but he is my responsibility and I will care for him and somehow provide him a safe place and home if you allow me to.’

Indeed, some advertisements expressed direct unwillingness to live with couples or families with children:

‘Not looking for: … couples or families with children’

‘My partner and I have a puppy now 8 months so looking for a place with a backyard and that allows pets …. Puppy is toilet trained and friendly with people and other dogs.’

Smokers identified themselves in 8% of listings.

Overall, the difficulties faced by people with children, pets, or smokers in being accepted into share households may explain why these individuals have placed advertisements directly appealing for accommodation, perhaps having already applied unsuccessfully for posted vacancies.

Suppliers of share accommodation

Data on those placing advertisements for share accommodation via the platform is more limited, confined to information voluntarily supplied in the free text of listings. However, many advertisements expressed preferences for new flatmates of a particular gender or other criteria. In this way, share accommodation vacancies differ to the ‘formal’ rental market, where nominating gender or ethnicity criteria is illegal (Martin, Citation2012; NSW Fair Trading, Citation2012). Given the intimate social relations associated with sharing domestic space, expressing a preference for flatmates of a particular gender may be justified (Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2022). In this dataset, almost half of the listings (50%) showed a preference for particular groups, such as females only (17%) or singles (28%).

‘I’m looking to live with other female flatmates who share the same values as I; clean, respectful and quiet.’

Although not common, some listings mentioned preference for flatmates of a particular ethnicity.

‘I am a 31yr old Irish girl living in Sydney for 6 years … Preferably looking to share with another Irish/English girl with similar interests.’

Nine listings indicated that the household was LGBTQI friendly. Overall, the preferences to live with people of a similar age cohort, particular gender or ethnicity, reflect the added complexities of the share rental market where social characteristics of the household must be factored into the search process along with more standard property criteria for location and price.

Qualitative analysis of listings data across both data sets implies that many advertisements are placed by individuals or existing groups conforming with, or seeking traditional models of cooperatively managed share accommodation in which residents jointly manage chores and share access to common living spaces (as outlined in ). It was not uncommon to find listings placed by head-tenants having lease agreements of their rental properties to spare a room for renting to additional tenants.

‘We are Mery and Kawani, looking for 1 or 2 more flatmates, to fill the second room of the apartment that we are already renting.’

Some advertisements sought other people to form a (new) share household. The platform actively facilitates such opportunities through a tenant matchmaking function known as ‘Teamups’.

Details about household arrangements or the nature of the landlord relationship were not generally disclosed in advertisements offering accommodation. However, in analysing our data set we looked for indicators associated with boarding or lodging arrangements, such as whether rooms are furnished and or whether rents are inclusive of utilities.

‘The room is currently furnished with a queen sized bed and mattress, study desk, and bedside. These are all optional and no extra charge. Room includes a good sized built in wardrobe and a privacy lock. Bills (water, electricity, gas, internet) included.’

Of our advertisements, 59% indicated that shared properties were already furnished and that the costs of electricity, water supply, gas and internet were included in the weekly rents. This implies a relatively high proportion of share rental vacancies are being provided on a commercial basis rather than organised by collectively managed group households.

Further evidence for this finding is in the concern expressed by those seeking accommodation about potentially exploitative arrangements, landlord harassment, and arrangements they wished to avoid.

‘No Boarding house please.’

Some sought to mitigate risks of insecure tenure by seeking a written tenancy agreement or formal lease.

Why are people seeking share accommodation?

Many advertisements placed by those seeking accommodation disclose personal circumstances which help explain why share accommodation may be sought. Consistent with prior research on share households (Heath et al., Citation2018), these reasons included young adults leaving the family home; people already living in share accommodation but needing alternative arrangements because of their lease ending or the household disbanding; people relocating to Sydney; or the need for a more affordable housing option.

Affordability

As highlighted in the literature, sharing can be a strategy for reducing or recouping housing costs (Kendig, Citation1984; Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2019; Parkinson et al., Citation2022). Research on Sydney’s share housing market has suggested that rental costs to share are measurably lower than rents in the formal market at between half to two thirds of the medians (Zhang & Gurran, Citation2021). Similarly, the data set examined in this study indicates a preferred rental budget volunteered by those seeking share accommodation that is much less than equivalent median rents in the formal sector. About a quarter of those seeking share accommodation indicated a rental budget of up to $200 per week, and over half indicated they could pay between $201 to $300 (). This implies that those seeking share accommodation via the Flatmates platform do have quite constrained rental budgets, although it is unclear whether these budgets reflect what those seeking accommodation can afford to pay or rather their understanding of the market rents associated with the accommodation they sought. Text analysis revealed some references to saving money by sharing:

Table 3. Tenancy duration and weekly rent.

‘Looking to save money and maybe have a cool housemate to share a drink with.’

However, affordability considerations were generally downplayed in advertisements placed by those seeking accommodation, with people more likely to mention their stable employment and income as credentials for making weekly rent.

Flexibility and tenancy periods

Our dataset indicated that demand for flexible lease periods may motivate some people to seek share accommodation, consistent with recent research (Boccagni & Miranda Nieto, Citation2022). Nearly a fifth of our data set were seeking accommodation for less than six months. Analysis of listings text revealed that shorter rental tenure may offer a way of testing the arrangement, before committing to a housing situation which might not be suitable.

‘Shorter lease works initially. say one month with ongoing longer potential.’

However, most people advertising for accommodation sought longer tenure (), implying no greater need for flexibility than those seeking a standard residential lease in the formal sector. This finding may provide further evidence that people seeking share accommodation have been priced out of the ‘formal’ rental sector; and may have to trade tenure security against lower cost.

The impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The data for this study was collected during a period of rolling government restrictions associated with the early stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. References to the Pandemic were made in 117 advertisements placed by people seeking accommodation, offering insights into its impact on the demand for and supply of share accommodation, which included people losing employment due to the Pandemic, as well as household circumstances changing more generally.

‘Have been living in Enmore for yonks but COVID-19 threw a couple of my housemates a curveball and we’re unfortunately having to call it a wrap.’

Notably, although the state government imposed a general moratorium on rental evictions during the early period of the Pandemic, this was not easily extended to those living in informal and negotiated share arrangements. A number of advertisements disclosed that they had lost accommodation due to the Pandemic which reportedly prompted their landlord to sell.

‘Looking for a new home as my current landlords are having to sell their house from Covid related financial issues.’

Some advertisements disclosed concerns about physical distancing and the health risks of sharing during the Pandemic period. Others anticipated needing to spend longer time at home due to COVID-19 work from home requirements or a COVID-19 related job loss.

‘26 year old female working in medical law. Currently working from home due to covid, going into the office once a week.’

In summary, the Pandemic raised additional complexities for people living in the share housing sector, reflecting their reduced security of tenure and the difficulties of cohabiting with others in the midst of a public health crisis. Sustained demand for share housing despite these difficulties and the generally lower levels of population pressure in the major cities due to border closers is a reflection of the critical role sharing now plays in Australia’s constrained private rental sector (Raynor & Panza, Citation2021).

How does the supply of share accommodation match express demand?

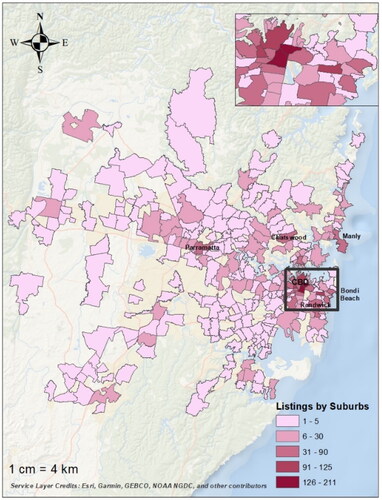

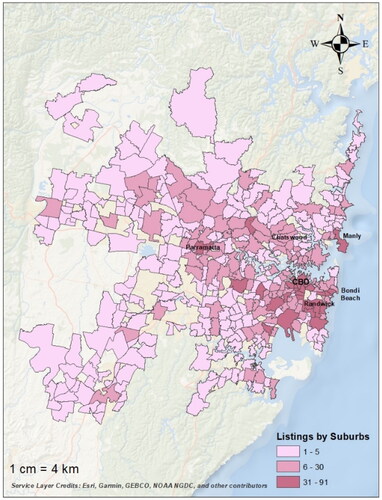

We now turn to our supply/demand analysis. Maps one and two compare the geography of demand for share housing in Sydney, with listed vacancies. Notably, consistent with earlier research (Zhang & Gurran, Citation2021), spatial demand for share housing (measured by peoples’ first listed preference) tends to follow the contours of Sydney’s overall housing market, gravitating to accessible locations near central employment areas, universities, train lines, or beachfront areas of high amenity (). Our data suggests that this demand for central locations persisted despite the general softening of Sydney’s inner ring housing market over the first two years of the global Pandemic during which time international migration was suspended and universities and offices shifted to remote modes of operation (Buckle et al., Citation2023).

By contrast, the spatial distribution of share housing supply is somewhat more dispersed across the Sydney metropolitan area (). Sub-regional analysis reveals that shared housing supply was higher in the City and Inner South, and Eastern Suburbs sub-regions, gradually decreasing towards the outer regions (). The majority of these listings were private rooms (3029 listings, 85%), with 7% shared rooms (267 listings). Most accommodation required residents to share bathrooms (66%).

Table 4. Balance of share housing demand and supply in Sydney subregions.

Despite the higher overall volume of share vacancies relative to advertisements placed by people seeking accommodation, there were demonstrably fewer share housing vacancies relative to express demand in the City and Inner South sub-region (). There was also pronounced differences between the demand for, and supply of share housing vacancies across Sydney’s northern suburbs ( and ). These deficits may reflect a combination of high rental costs and a lack of suitably sized accommodation available for new share households to form. The supply shortage relative to express demand is of particular note given the generally lower levels of demand that might be expected during the COVID-19 period, as outlined above. These data suggest that share rental shortages are likely to increase when Sydney’s housing market faces demand pressures.

Table 5. Share housing relative to formal housing stock (top suburbs of shared housing demand vs supply Aug 2020).

As outlined above, the majority of those seeking share accommodation via the Flatmates platform indicated a preference for longer leases. However, the supply of share accommodation is typically of a shorter lease period, with 38% of vacancies available for less than six months (the majority 1-3 months only), although 20% of listings indicated a flexible duration (). Less than a quarter of rooms or shared rooms were available for more than six months. This discrepancy between express demand for secure rental accommodation and the supply of longer-term share leases underscores the increased precarity associated with the share housing sector.

What is the role of the platform mediated share housing sector within the wider private rental market?

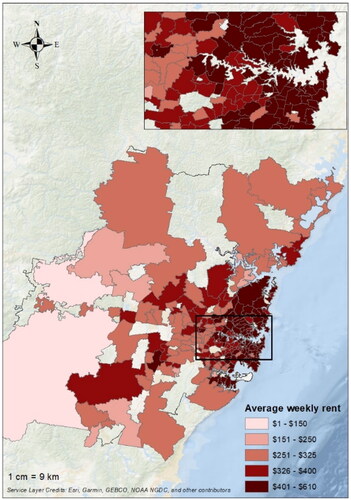

Our data indicates that the quantum of share accommodation offered via the Flatmates extends the existing rental housing supply by a significant factor; overall adding an additional 14% to Sydney’s rental vacancy rate in August 2020 (). The impact of additional supply from shared housing vacancies was even more pronounced in particular suburbs, such as Manly. Our data also indicates that share housing vacancies advertised via the platform are likely to form an important, if largely informal, contribution to Sydney’s lower cost rental supply.

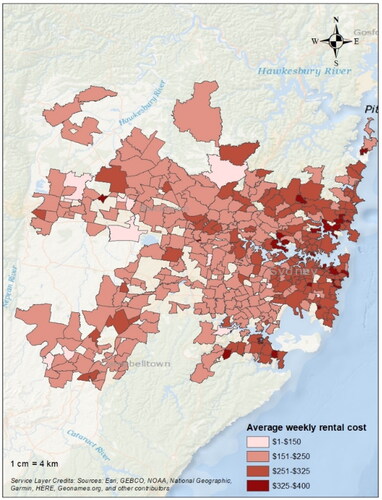

To understand the costs and affordability of the share housing sector relative to the wider market, we compared the median asking rent sought by those advertising share accommodation with the median market rents for zero- and one-bedroom properties in the broader rental market. As expected, this analysis found that the median weekly rent sought for advertised share vacancies was lower than that for one-bedroom/self-contained units (; ). For example, the median asking rent for shared accommodation in the localities of Surry Hills and Bronte was between 59% and 64% for the median rent for one-bedroom properties in the formal private rental market.

Map 4. Formal housing rental cost.

Source: Rental bonds data (up to one bedroom properties) Aug 2020.

This does not mean that rents in the share accommodation sector are necessarily affordable relative to incomes, given overall high rents in Sydney. Almost three quarter of share vacancies (71%) listed rents of up to $300 per week. This was considered technically affordable for individuals in second lowest income quantileFootnote3 in August 2020, at the 30% housing cost thresholdFootnote4. However, less than 5% of share vacancies were affordable for individuals/households in the lowest income quintile with rental benchmark of $150 per week (). This finding highlights the fact that although sharing may be lower cost than other private rental accommodation, it is not necessarily affordable for the very low-income earners who are increasingly dependent on this sector.

Overall, these data suggest a tight market for share housing vacancies, mirroring the formal sector. The data may also suggest commercial practices within the share housing sector. Those seeking share accommodation likely anticipate dividing total rental costs equally with other household members (or on the basis of room size and facilities) as is traditional in share households. However, landlords providing share accommodation are more likely to set rents to maximise profit, including by renting shared rooms to individuals if rental returns are higher. The platform technology facilitates this practice, making it easier for landlords to advertise rooms to individuals directly, rather than whole dwellings to a single household, potentially achieving a higher rental yield.

Discussion

In this study we have examined demand and supply for share accommodation in Sydney, drawing on online data from the Flatmates platform. The share housing market is only a small component of the housing system, however results of this study support the emerging body of research pointing to its important role in supplying accommodation to those with limited budgets and options (Maslova, Citation2022; Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2022; Ronald et al., Citation2023). Enabled by new platform technology able to eliminate the traditional search and transaction costs associated with informal practices, share housing seems poised to transition from an informally organised social practice to a more complex segment of the private rental market. Evidence for this transition is provided by our data suggesting that a majority of accommodation vacancies (59%) were furnished and featured all-inclusive rents, associated with a commercially organised arrangement rather than collectively organised group household.

What makes our dataset and findings distinctive is that these share housing listings are advertised via a home sharing website targeting ‘flatmates’ rather than a real estate platform dominated by conventional landlords and their agents. Further, rather than a typically commercial form of shared accommodation, such as a boarding house or purpose built ‘co-living’ property, the accommodation listed on Flatmates is situated within a standard apartment or dwelling. Of the accommodation listings in our data set, two thirds required residents to share bathrooms – evidencing that the share housing market facilitated by Flatmates platform is primarily occurring within Sydney’s conventional housing stock rather than purpose-built accommodation. With such vacancies now able to be created within the existing housing stock often as a subset of existing tenure arrangements, the supply of share accommodation is likely to increase with higher housing costs, affordability burdens, and reduced vacancies across the formal rental market. In this way, platform enabled sharing might be regarded as an informal and rapidly responsive ‘release valve’ for the overall housing system during periods of high demand. Indeed, given that our study was conducted during an atypical period of muted demand in the wake of international border closures and the Covid-19 Pandemic, it is likely that the role of platform enabled sharing may become even more important when population growth resumes. However, our data set highlights broader concerns about the appropriateness, affordability, and security of the sector for low-income renters and those with special housing needs.

Social relations

As recounted in the emerging literature on share households, living in share accommodation implies constraints on privacy and a need to conform to household norms or expectations (Clark et al., Citation2019; Heath et al., Citation2018). Many of these norms are established through verbal and or written rules for household members either at the time of tenancy or negotiated while living together (Nasreen and Ruming Citation2022).

Navigating these social relations will be especially challenging for people with particular housing needs or at different stages of their life. People with a disability, older women, or parents with children, will face additional barriers to accessing a share household while likely finding shared accommodation unsuitable to their needs.

Yet accepting these arrangements is critical to ongoing tenure security in the share housing sector, as highlighted in the wider literature (Heath et al., Citation2018; Clark et al., Citation2019). As revealed by our data, these social relations become even more complex when renting from an onsite landlord as a boarder or a lodger within their own home or a property which they manage.

Share accommodation and housing design

It is possible that concerns about social conflicts in share accommodation can be addressed by design solutions embedded in purpose-built share accommodation, such as ‘co-living’ developments, or new generation boarding houses; which feature small self-contained rooms for singles or couples, as well as generous communal kitchens, recreational facilities, and landscaping (Druta et al., Citation2021; Ronald et al., Citation2023). Such special purpose developments, particularly if enhanced by inherent design features, such as robust noise insulation, visual screening of windows or balconies, sufficient storage in kitchens and utility rooms, may help residents enjoy the social benefits of sharing while still exercising privacy and autonomy in their daily lives. As highlighted by our study carried out during the COVID-19 Pandemic, sharers may also increasingly be working from home, a further factor to consider in residential design. Even so, such accommodation is unlikely to be appropriate for people across the life course; nor is it generally affordable for those on very low incomes, unless regulated for rent control.

Discounted but not affordable

Our data points to a marketisation of share housing, facilitated by platforms such as Flatmates. This is a market for people and households, as much as it is for residential accommodation. But in addition to the markets created by households seeking new members, or people seeking households; new commercial operators offering all-inclusive rooms to rent appear to be using the platform technology to recruit new tenants. Under such arrangements, rental costs for rooms may be lower than for whole dwellings, but savings are not necessarily passed on to tenants. This is because landlords opting to rent a property by the room rather than as a whole dwelling, will still seek to maximise rental return. In fact, our data indicated that less than 5% of share vacancies were affordable for individuals/households in the lowest income quintile. This raises questions about the need to monitor and or regulate this informal sector of the housing market.

The utility of platform data and technology

Finally, our study adds to the growing literature on the potential for using platform data to inform regulation and housing policy (Boeing et al., Citation2021). In particular, the capacity to utilise real time rental advertisements as a window into segments of the market at particular points in the market cycle and at fine grained geographical scale suggests that more targeted interventions and types of housing assistance may now be possible. Not only does such data offer an ‘early warning’ insight into rising housing demand and unmet need (Rae, Citation2015); it may also shed light on substandard rental units or unauthorised short-term accommodation (Boeing et al., Citation2021). Periodic review of accommodation listings over time will enrich research and policy understandings of this segment of the housing system and how market practices may co-evolve with increased use and technical sophistication of online platforms.

Many of the concerns raised in our study arise from the operation of an unregulated private rental market in share accommodation, enabled by an arm’s length profit seeking platform. However, there is rising interest in non-marketized, communally focused forms of housing development and tenure, which offer alternative forms of shared accommodation and management (Crabtree et al., Citation2021). The powerful search and matching functions of online platforms could facilitate such arrangements – for instance, by enabling groups with particular interests or requirements, such as older women, or single parents – to connect and form new types of housing cooperative. Such platform enabled cooperatives would pool resources to repurpose housing within the existing stock; or organise to attract support and subsidies for new and appropriate shared housing typologies.

Conclusion

Our study shows that a variety of people across their life course are now seeking share accommodation via online platforms in the absence of sufficient government responses to unmet housing need. In fact, demand for share accommodation on the primary platform ‘Flatmates.com.au’ exceeded advertised supply in key locations of Sydney during a period of low population growth over the COVID-19 Pandemic, and despite hygiene concerns, government requirements to ‘stay at home’, and wider opportunities to relocate to potentially lower cost housing markets while working remotely. This sustained demand for share housing implies that in expensive cities such as Sydney, affordability pressures are sufficient to outweigh preferences for privacy, autonomy, or housing amenity.

While the longer-term implications of this study add to the extensive volume of research demonstrating that policy intervention is needed to support and subsidise affordable rental housing in high demand locations, it is likely that future sharers will be more demographically diverse than in the past. Therefore, it is also important to ensure that future residential developments are able to accommodate different household types and housing preferences, including preferences for larger households or sharing by non-related adults.

Catering to many of the most vulnerable people in the housing system – income constrained renters with few alternatives, and traditional cohorts of younger people at transitional points in their lives, as well as full-time working professionals looking for accommodation close to their job locations; the share housing sector is increasingly critical as a default market response to unmet housing need. Yet under the broader conditions of financialisation and platformisation within which this market response has emerged, our study shows that share housing is not necessarily discounted by landlords, let alone affordable or appropriate for lower-income earners.

More widely, the findings of this study contribute to the emerging literature on the rise of informality in housing systems across the global north and particularly the role of online platforms in both enabling and exposing a complex and segmented share housing market. By opening new vacancies within existing dwellings or households, platform technology may increase the flexibility and responsiveness of the housing market. But with this flexibility comes new risks for vulnerable renters which demand scrutiny and policy intervention. The policy opportunity is to repurpose platform technology for social good – connecting the diverse cohorts of people now unable to access affordable rental housing in the private market – with appropriate and secure alternatives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 a platform specialised in share housing listings

2 Suburbs are the geographical term used to describe residential localities in Australian cities and regions. They typically include multiple neighbourhoods, one or two small business districts, educational and civic buildings.

3 In NSW, households earning weekly income up to $460 are placed in lowest income quintile and households earning weekly income up to $1050 are placed in second lowest quintile ABS. (Citation2019). "Household Income and Wealth, Australia." Retrieved 15 Jan 2021, from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/finance/household-income-and-wealth-australia/latest-release#data-download.

4 Households in the lowest income distribution, who spend more than 30% of their gross income on rents are considered in ‘rental stress’ Nepal, B., R. Tanton and A. Harding (2010). "Measuring housing stress: how much do definitions matter?" Urban Policy and Research 28(2): 211-224.

References

- ABS (2021) Greater Sydney, 2021 Census Community Profiles. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/community-profiles/2021/1GSYD (accessed 18 July 2022).

- ABS (2016) Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 3 – Non ABS Structures, July 2016. Available at http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/1270.0.55.003July%202016?OpenDocument (accessed 02 May 2017).

- ABS (2019) Household Income and Wealth, Australia. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/finance/household-income-and-wealth-australia/latest-release#data-download (accessed 15 January 2017).

- ABS (2020) ABS TableBuilder Dataset: 2016 Census - Counting Persons, Place of Enumeration (MB). Available at https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/1GSYD?opendocument (accessed 5 November 2021).

- Ahrentzen, S. (2003) Double indemnity or double delight? the health consequences of shared housing and “doubling up”, Journal of Social Issues, 59, pp. 547–568. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00077

- Alam, A., Minca, C. & Uddin, K. F. (2022) Risks and informality in owner-occupied shared housing: To let, or not to let?, International Journal of Housing Policy, 22, pp. 59–82.

- Boccagni, P. & Miranda Nieto, A. (2022) Home in question: Uncovering meanings, desires and dilemmas of non-home, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 25, pp. 515–532. doi: 10.1177/13675494211037683

- Boeing, G., Besbris, M., Schachter, A. & Kuk, J. (2021) Housing search in the age of big data: Smarter cities or the same old blind spots?, Housing Policy Debate, 31, pp. 112–126.

- Boeing, G. & Waddell, P. (2017) New insights into rental housing markets across the United States: Web scraping and analyzing craigslist rental listings, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 37, pp. 457–476.

- Bricocoli, M. & Sabatinelli, S. (2016) House sharing amongst young adults in the context of mediterranean welfare: The case of milan, International Journal of Housing Policy, 16, pp. 184–200. doi: 10.1080/14616718.2016.1160670

- Buckle, C., Gurran, N., Harris, P., Lea, T. & Shrivastava, R. (2023) Intersections between housing and health vulnerabilities: Share housing in sydney and the health risks of COVID-19, Urban Policy and Research, 41, pp. 22–37. doi: 10.1080/08111146.2022.2076214

- Chiodelli, F. (2019) The dark side of urban informality in the global North: Housing illegality and organized crime in Northern Italy, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43, pp. 497–516.

- Clark, V., Tuffin, K., Bowker, N. & Frewin, K. (2019) Rosters: Freedom, responsibility, and co‐operation in young adult shared households, Australian Journal of Psychology, 71, pp. 232–240. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12238

- Clark, V., Tuffin, K., Frewin, K. & Bowker, N. (2018) Housemate desirability and understanding the social dynamics of shared living, Qualitative Psychology, 5, pp. 26–40. doi: 10.1037/qup0000091

- Crabtree, L., Perry, N., Grimstad, S. & McNeill, J. (2021) Impediments and opportunities for growing the cooperative housing sector: An australian case study, International Journal of Housing Policy, 21, pp. 138–152. doi: 10.1080/19491247.2019.1658916

- Druta, O., Ronald, R. & Heath, S. (2021) Urban singles and shared housing, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1195–1203. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2021.1987507

- Druta, O. & Ronald, R. (2021) Living alone together in Tokyo share houses, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1223–1240. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2020.1744704

- Durst, N. J. & Wegmann, J. (2017) Informal housing in the United States, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, pp. 282–297.

- Ferreri, M. & Sanyal, R. (2018) Platform economies and urban planning: Airbnb and regulated deregulation in London, Urban Studies, 55, pp. 3353–3368.

- Ferreri, M. & Sanyal, R. (2022) Digital informalisation: Rental housing, platforms, and the management of risk, Housing Studies, 37, pp. 1035–1053.

- Fields, D. & Rogers, D. (2021) Towards a critical housing studies research agenda on platform real estate, Housing, Theory and Society, 38, pp. 72–94.

- Freeman, L. (2017) Governed through ghost jurisdictions: Municipal law, inner suburbs and rooming houses, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, pp. 298–317.

- Goodman, R., Nelson, A., Dalton, T., Cigdem, M., Gabriel, M. & Jacobs, K. (2013) The experience of marginal rental housing in Australia, AHURI Final Report No. 210, pp. 1–150.

- Gurran, N., Maalsen, S. & Shrestha, P. (2022) Is ‘informal’ housing an affordability solution for expensive cities? Evidence from Sydney, Australia, International Journal of Housing Policy, 22, pp. 10–33.

- Harris, R. (2018) Modes of informal urban development: A global phenomenon, Journal of Planning Literature, 33, pp. 267–286.

- Harten, J. G., Kim, A. M. & Brazier, J. C. (2021) Real and fake data in Shanghai’s informal rental housing market: Groundtruthing data scraped from the internet, Urban Studies, 58, pp. 1831–1845.

- Heath, S., Davies, K., Edwards, G. & Scicluna, M. R. (2018) Shared housing, shared lives: Everyday experiences across the lifecourse, (New York: Routledge).

- Hilder, J., Charles-Edwards, E., Sigler, T. & Metcalf, B. (2018) Housemates, inmates and living mates: Communal living in Australia, Australian Planner, 55, pp. 12–27.

- Jones, G. (1987) Leaving the parental home: An analysis of early housing careers, Journal of Social Policy, 16, pp. 49–74.

- Kendig, H. L. (1984) Housing careers, life cycle and residential mobility: Implications for the housing market, Urban Studies, 21, pp. 271–283. doi: 10.1080/00420988420080541

- Kenyon, E. & Heath, S. (2001) Choosing this life: Narratives of choice amongst house sharers, Housing Studies, 16, pp. 619–635.

- Kim, J., Woo, A. & Cho, G.-H. (2020) Is shared housing a viable economic and social housing option for young adults?: Willingness to pay for shared housing in Seoul, Cities, 102, p. 102732. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102732

- Leopold, J. (2016) Improving measures of housing insecurity: A path forward (Washington: The Urban Institute).

- Maalsen, S. (2019) I cannot afford to live alone in this city and I enjoy the company of others: why people are share housing in sydney, Australian Geographer, 50, pp. 315–332. doi: 10.1080/00049182.2019.1613026

- Maalsen, S. (2020) Generation share’: Digitalized geographies of shared housing, Social & Cultural Geography, 21, pp. 105–113.

- Maalsen, S. & Gurran, N. (2022) Finding home online? The digitalization of share housing and the making of home through absence, Housing, Theory and Society, 39, pp. 401–419.

- MacDonald, H., Nelson, J., Galster, G., Paradies, Y., Dunn, K. & Dufty-Jones, R. (2016) Rental discrimination in the multi-ethnic metropolis: Evidence from sydney, Urban Policy and Research, 34, pp. 373–385. doi: 10.1080/08111146.2015.1118376

- Martin, C. (2012) Tenants’ Rights Manual: A Practical Guide to Renting in NSW, 4th ed. (Annandale, NSW: The Federation Press).

- Maslova, S. (2022) Housing for highly mobile transnational professionals: Evolving forms of housing practices in Moscow and London, Mobilities, 17, pp. 415–431.

- McNamara, S. & Connell, J. (2007) Homeward bound? searching for home in inner sydney’s share houses, Australian Geographer, 38, pp. 71–91. doi: 10.1080/00049180601175873

- Nasreen, Z. & Ruming, K. J. (2021) Shared room housing and home: Unpacking the home-making practices of shared room tenants in sydney, Australia, Housing, Theory and Society, 38, pp. 152–172. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2020.1717597

- Nasreen, Z. & Ruming, K. (2019) Room sharing in Sydney: A complex mix of affordability, overcrowding and profit maximisation, Urban Policy and Research, 37, pp. 151–169.

- Nasreen, Z. & Ruming, K. (2022) Struggles and opportunities at the platform interface: Tenants’ experiences of navigating shared room housing using digital platforms in Sydney, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 37, pp. 1537–1554.

- NSW Fair Trading (2012) Fact Sheet: Discrimination in the rental market, NSW Government. Available at http://www.fairtrading.nsw.gov.au/ftw/Tenants_and_home_owners/Being_a_landlord/Starting_a_tenancy/Discrimination_in_the_rental_market.page (accessed 16 May 2017).

- NSW Fair Trading (2020) Rental Bonds Data, 2020, NSW Government. Available at https://www.fairtrading.nsw.gov.au/about-fair-trading/rental-bond-data (accessed 20 Sep 2020).

- Parkinson, S., Hulse, K., Rowley, S., James, A. & Stone, W. (2022) Diffuse informality: Uncovering renting within family households as a form of private rental, Housing Studies, pp. 1–20. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2022.2101623

- Parkinson, S., James, A. & Liu, E. (2018) Navigating a changing private rental sector: Opportunities and challenges for low-income renters AHURI Report No. 302, Melbourne.

- Porter, L., Fields, D., Landau-Ward, A., Rogers, D., Sadowski, J., Maalsen, S., Kitchin, R., Dawkins, O., Young, G. & Bates, L. K. (2019) Planning, land and housing in the digital data revolution/the politics of digital transformations of housing/digital innovations, PropTech and housing–the view from Melbourne/digital housing and renters: Disrupting the Australian rental bond system and tenant advocacy/prospects for an intelligent planning system/what are the prospects for a politically intelligent planning system?, Planning Theory & Practice, 20, pp. 575–603.

- Portes, A., Castells, M. & Benton, L. A. (1989) The informal economy: Studies in advanced and less developed countries (Baltimore, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press).

- Rae, A. (2015) Online housing search and the geography of submarkets, Housing Studies, 30, pp. 453–472.

- Raynor, K. & Panza, L. (2021) Tracking the impact of COVID-19 in Victoria, Australia: Shocks, vulnerability and insurances among residents of share houses, Cities (London, England), 117, pp. 103332.

- Ronald, R., Schijf, P. & Donovan, K. (2023) The institutionalization of shared rental housing and commercial co-living, Housing Studies, pp. 1–25. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2023.2176830

- Sarkar, S. & Gurran, N. (2017). Shared urbanism: Big data on accommodation sharing in urban Australia. 15th International Conference on Computers in Urban Planning and Urban Management, Adelaide, Australia, July 11–14.

- Shaw, J. (2020) Platform real estate: Theory and practice of new urban real estate markets, Urban Geography, 41, pp. 1037–1064. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2018.1524653

- Sullivan, B. J. & Burke, J. (2013) Single-room occupancy housing in New York City: The origins and dimensions of a crisis.", CUNY Law Review, 17, pp. 113.

- Thorpe, A. (2021) Regulatory gentrification: Documents, displacement and the loss of low-income housing, Urban Studies, 58, pp. 2623–2639.

- Usman, M., Maslova, S. & Burgess, G. (2021) Urban informality in the global North: (Il)legal status and housing strategies of Ghanaian migrants in New York City, International Journal of Housing Policy, 21, pp. 247–267.

- Uyttebrouck, C., Van Bueren, E. & Teller, J. (2020) Shared housing for students and young professionals: Evolution of a market in need of regulation, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 35, pp. 1017–1035. doi: 10.1007/s10901-020-09778-w

- Vacha, E. F. & Marin, M. V. (1993) Doubling up: Low income households sheltering the hidden homeless, Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 20, pp. 25.

- Wachsmuth, D. & Weisler, A. (2018) Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50, pp. 1147–1170.

- Wright, B. R. E., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E. & Silva, P. A. (1998) Factors associated with doubled-up housing—a common precursor to homelessness, Social Service Review, 72, pp. 92–111.

- Zhang, Y. & Gurran, N. (2021) Understanding the share housing sector: A geography of group housing supply in metropolitan Sydney, Urban Policy and Research, 39, pp. 16–32.