?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Work from home (WFH) received much public attention. Imposing such a measure was feasible in the context of labour markets’ flexibilisation, which has reshaped urban live-work relationships. However, the pandemic’s effects on those relationships have rarely been explored in housing and planning studies. This paper draws a research agenda based on a literature review of the changes in urban live-work relationships, which were accelerated and legitimised under COVID-19. The latter is considered an exogenous shock contingent upon several other shocks, embedded in structural crises and accelerating ongoing trends. The literature confirms the acceleration of hybrid work for those able to do so, which has fuelled debates on home usage and legitimated planning discourses based on urban proximity, densification and mixed use. Hence, we encourage critical research on (i) the conceptualisations of WFH and COVID-19, (ii) housing policy responses to accumulated uncertainties and regulations for quality and resilient housing, and (iii) the critical analysis of WFH-oriented planning.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and related stay-at-home measures have genuinely brought into question how and where we live and work in cities. Those able to work from home (WFH) were requested to do so during the pandemic. Homeworkers and their living and working conditions received much attention in academia, policy and the media, at the expense of more vulnerable groups. Nonetheless, these peoples’ intense practice of home-based telework and the public attention received are expected to have spatial, policy and institutional consequences in the fields of housing and planning. We consider COVID-19 a shock event that has fuelled structural crises—especially the housing crisis—and accelerated ongoing societal trends, among which the flexibilisation of work and its implications for housing and planning is one of the most apparent.

Imposing WFH to contribute to tackling the pandemic was feasible in the context of labour markets’ flexibilization, which began in the 1970s—under the development of information and communication technology (ICT) and the advent of the new economy (Hutton, Citation2009; van Meel & Vos, Citation2001)—and facilitated bringing work back into the home. The flexibilisation of work materialised in different ‘generations’ of telework (Messenger & Gschwind, Citation2016), referring to work performed outside of the employer’s premises by using technology (Aguilera et al., Citation2016). Although the concept of WFH could include any kind of ‘work’ performed at home, the way it was experienced during COVID-19 and understood in the literature may be assimilated with the first generation of home-based telework (or ‘remote work’ for full-time home-based work). Conversely, more recent forms of mobile telework (or multilocational work) and virtual telework can be performed anytime and anywhere. All of these flexible working arrangements can be summarised under the umbrella term ‘flexwork’ (Pajević, Citation2021).

Notably, the flexibilisation and dematerialisation of work have affected home meanings and practices (Bergan et al., Citation2020; Doling & Arundel, Citation2020; Tunstall, Citation2023) and impacted housing provision, especially in large cities. These cities have increasingly integrated live-work goals in their urban development and regeneration strategies, by fostering densification and mixed-use development to create attractive live-work environments in the context of accelerated globalisation, advanced capitalism and competitiveness, hence creating new urban live-work relationships (Uyttebrouck, De Decker, et al., Citation2021; Uyttebrouck, Remøy, et al., Citation2021).

The pandemic’s effects on these live-work relationships have rarely been explored from the perspective of housing or planning studies. Yet, changes in these relationships during and after COVID-19 raise multiple questions ranging from home meanings to the geography of work and residential preferences. The way these questions are addressed further relies on conceptualising COVID-19 as a study object and articulating it with contingent shocks, structural crises, long-term trends and local policies and institutions. Hence, COVID-19’s impact on live-work relationships not only handles spatial and policy challenges, but their exploration also requires adequate analytical frameworks. This paper aims to deliver a research agenda for housing and urban studies, starting from the following question: What changes in urban live-work relationships made apparent under COVID-19 require further research? To identify current academic discourses and relevant avenues for housing and urban research, we reviewed the most relevant sources resulting from a systematic mapping of the literature on urban living and working during the pandemic.

The next section clarifies our analytical approach to COVID-19 and its embeddedness in contingent shocks, crises and trends. It further provides a background on the impact of past major crises on labour markets’ flexibilisation, urban housing provision and the present structural global housing crisis. Section 3 presents the methodological aspects and first insights from the systematic literature mapping. The qualitative review of the retained sources (Section 4) then focuses on the accelerated shift to hybrid work, debates on post-pandemic housing during the crisis context and legitimated planning discourses. Finally, the research agenda (Section 5) builds upon three research axes: the conceptualisation of WFH and COVID-19, ‘post-pandemic’ housing provision and related planning issues.

2. COVID-19’s effects on urban living and working: analytical framework and theoretical background

2.1. COVID-19 as a shock event

Whether they are of a financial, institutional or health nature, crises rely on threat, urgency and uncertainty and can affect several systems simultaneously (Boin, Citation2009). Much more than a health crisis, COVID-19 has been a ‘syndemic’ with complex interactions involving multiple socio-economic and environmental factors, including socio-spatial inequalities (Ellis et al., Citation2021). Capano et al. (Citation2022) framed the COVID-19 crisis as an ‘exogenous shock’ and an ‘episode of collective stress’ leading to three overlapping reconfigurations of policy-making: normalisation (path disruption leading to a ‘new normal’), adaptation (path continuity with policy realignment) and acceleration (path clearing speeding up evolutionary policy dynamics). These concepts build upon historical institutionalism and policy change theory.

The pandemic was seen as a ‘critical juncture’ leading to path disruption in its initial stages (e.g. Dupont et al., Citation2020). In planning studies, critical junctures are moments of crisis that make it possible for new institutions to be established under ‘major changes [that] are triggered primarily by exogenous forces’ (Sorensen, Citation2015, p. 25). Although COVID-19 enabled temporary policy changes that had been locked until then (e.g. housing the homeless or suspending evictions; see Section 4), these radical policy decisions often did not ‘normalise’ and remained temporary. Therefore, both academia and public opinion have focused on the adaptation (e.g. reinforced planning paradigms; see Section 4) and acceleration consequences (e.g. accelerated digitalisation and WFH for white-collar workers Vyas, Citation2022) of the COVID-19 shock. Hogan et al. (Citation2022) embraced the latter approach by viewing COVID-19 as a ‘path-clearing’ event that has accelerated ongoing trends and facilitated change since policy responses to the pandemic drew on strong path dependencies and paradigms.

Beyond the health emergency context, the effects of the pandemic are difficult to isolate because of COVID-19’s contingency upon several shocks (e.g. the war in Ukraine) and embeddedness in structural crises and long-term changes (e.g. digitalisation, flexibilisation). In particular, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine and the related energy shock have worsened the global housing crisis (see next subsection), which is evident in large cities subject to market-driven housing provision and financialisation (Wijburg, Citation2021). Other structural effects may take longer to be revealed. For example, crisis periods generate economic and regulatory disruptions that influence local ‘investor landscapes’, allowing new actors to emerge (Taşan-kok et al., Citation2021).

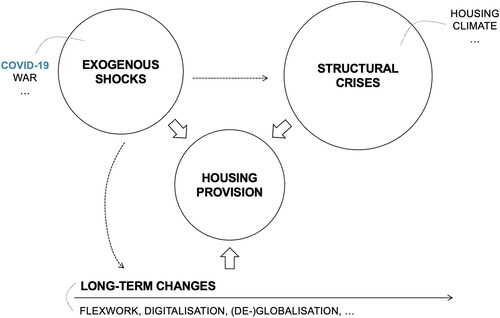

Hence, our analytical approach situates the pandemic as one event among many shocks that have fuelled a structural global housing crisis, accelerated the long process of the digitalization and flexibilisation of living and working places, and directly affected urban housing provision (). In what follows, we briefly introduce past crises’ impacts on housing provision as well as the effects of labour flexibilisation on urban living and working environments.

2.2. Crises, urban housing provision and the flexibilisation of living and working environments

Given their role in respiratory infections and mental health issues, housing conditions are a central determinant of health, (Krieger & Higgins, Citation2002). Historically, epidemic diseases have led to sanitary movements that translated into urban renewal operations, slum clearance and new housing regulations (Francke & Korevaar, Citation2021; Nayar, Citation1997). In the nineteenth century, governments addressed health crises through housing regulations requiring improved physical housing conditions and contributing to clearing ‘unsanitary areas’ (McKie, Citation1974). In the US, this facilitated the emergence of contemporary urban planning based on a ‘sanitary city’ discourse (Corburn, Citation2005, Citation2007). In Paris, successive cholera outbreaks paved the way for the Haussmannisation policies of the 1850s, which tackled ‘unhealthy’ medieval areas (Francke & Korevaar, Citation2021). Moreover, from an economic perspective, the Spanish flu, which remains the closest pandemic to COVID-19, led to increased housing prices in Spain and the reallocation of capital away from highly affected urban areas towards urbanised regions with less mortality, thereby contributing to their industrialisation (Basco et al., Citation2022).

Industrialisation profoundly marked these periods and led to the spatial segregation of living and working activities in reaction to concerns regarding the high-density juxtaposition of homes and industries, resulting in a Fordist city model (Doling & Arundel, Citation2020). This modernist effort continued after the Second World War through massive housing programmes delivering affordable housing segregated from noxious industries (Corburn, Citation2007) and slum clearance operations. From the 1970s onwards, the development of ICT, the shift towards the ‘new economy’ and knowledge-intensive services (Hutton, Citation2009), and the later digitisation of these services (Pajević, Citation2021) enabled flexible—and increasingly mobile—work arrangements for highly-educated workers (Felstead et al., Citation2002). These changes have transformed the labour market and impacted both housing provision and urban development at various levels.

At the housing level, the development of flexwork among precarious workers and ‘young professionals’—who are expected to be mobile (Bergan et al., Citation2020)—has contributed to enhancing flexible housing markets (Hochstenbach & Ronald, Citation2020), be it with regard to tenure or housing forms (typically shared housing with short-term rent). Since the global financial crisis (GFC)—which first led to a steep decline in housing prices where they had grown the most rapidly (Aalbers, Citation2015)—increasing market pressure and housing costs (Tromp, Citation2020) have encouraged a reduction in housing standards, including domestic space shrinking (Harris & Nowicki, Citation2020). In response to the GFC’s burden on housing provision, several Western European governments have attempted to stabilise housing markets (Boelhouwer, Citation2017) and stimulate affordable housing production (Wijburg, Citation2021). However, these measures did not prevent housing commodification and financialisation through different channels (e.g. rental properties; Aalbers, Citation2017) in certain countries. The ‘housing crisis’ concept has been used to describe housing shortages and low levels of affordability and accessibility, particularly in urban contexts. Since the GFC, the crisis has been considered ‘global’ because it has touched many national housing markets concomitantly (Aalbers, Citation2015). Nevertheless, this narrative must be used carefully because it tends to indicate structurally unsustainable housing provision (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016) and legitimate neoliberal policies leading to further deregulation and financialisation (Heslop & Ormerod, Citation2020).

At the urban level, the emergence of WFH and new workplaces (e.g. co-working spaces) has contributed to transforming residential areas into live-work neighbourhoods (Reuschke & Ekinsmyth, Citation2021). Such transformations were involved in planning movements (e.g. New Urbanism in North America) drawing on compacity and proximity—notably through density and mixed use—to stem urban sprawl and address environmental issues (e.g. Meijer & Jonkman, Citation2020). Strategic spatial planning has integrated the creation of such environments, particularly in office or industrial areas subject to urban regeneration (Ferm & Jones, Citation2016).

At the regional scale, the flexibilisation of work has impacted the geography of work and residential locations. Services and knowledge-based economic activities have been concentrated in ‘global cities’ (Sassen, Citation1991) and polycentric regions (Rader Olsson & Cars, Citation2011). However, flexible work arrangements tend to relax home-work constraints (Doling & Arundel, Citation2020) and encourage longer commuting distances (Uyttebrouck et al., Citation2022). Hence, in certain countries, people are more ready to accept a job further away if they can WFH (e.g. in the Netherlands: de Vos et al., Citation2018) and thus have more flexibility in residential choices (Bontje et al., Citation2017). Section 4 returns to these trends by identifying current discourses—particularly the assumed shift towards ‘hybrid work’—and providing evidence on COVID-19 and urban live-work relationships.

3. Systematic literature mapping

We conducted systematic literature mapping (SLM) to delineate the themes and disciplines underpinning COVID-19’s impacts on urban living and workingFootnote1 before the qualitative review of its most relevant sources to provide evidence and narratives on this topic. The analysis followed an abductive approach and drove us to revise our pre-analytical framework and the positioning of COVID-19 as a vector of change.

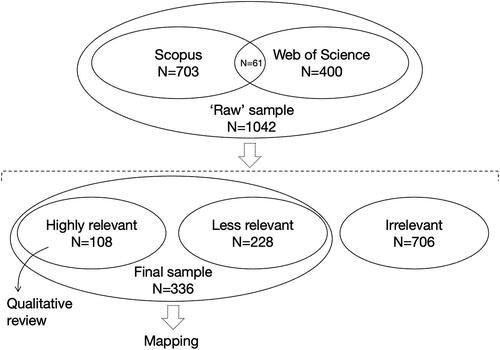

SLM facilitates the review of broad thematic literature before focusing on specific questions (Soaita et al., Citation2020), thus making it appropriate for examining COVID-19-related issues (e.g. social harm; Gurney, Citation2021) given the extensive volume of research published on this topic. However, biases related to the chosen database, the publication language and the authors’ own experience of WFH must be considered. Searches of two online scientific databases (Scopus and Web of Science; performed on 16 February 2023) associated the four areas underpinning living and working in a city during the pandemic (). The Scopus searchFootnote2 prioritised the housing-pandemic relationship over other connections and excluded irrelevant fields (703 references collected). The second search in Web of Science excluded similar fields (e.g. medicine, engineering, biotechnologies)Footnote3 and identified 400 references, including 61 duplicates with the Scopus search.

Table 1. Study dimensions and corresponding keywords used in the requests.

We screened the references of our ‘raw’ sample (n = 1042 with duplicates removed) to classify them according to their relevance. Rejected references covered a theme (e.g. air quality) or discipline (e.g. environmental studies) that was too weakly related to the research question. Within the final sample (n = 336; ), we distinguished highly relevant (e.g. theme related to home meanings or the post-pandemic city) and less relevant (e.g. sociology of work or mobility approaches) sources. The qualitative literature review (Section 4) used ‘highly relevant’ sources only (n = 108, as well as a few additional sources collected ‘manually’). Although the searches did not exclude any geographical area, the final sample overrepresents evidence from Western countries.

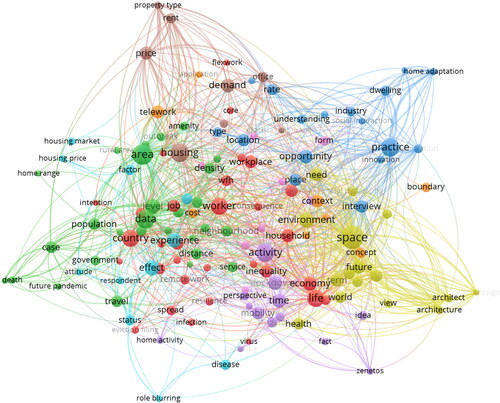

To provide general insights from the SLM, we generated maps of word occurrences (n 10, after excluding irrelevant words, such as period, author or variable) using the abstracts of highly relevant and less relevant references using VOSviewer. The network visualisation () shows the weightiest words and their relatedness. Although a small city-housing cluster is apparent, the largest clusters relate to mobility (e.g. ‘travel’, ‘trip’), working conditions (‘employee’ cluster, including, e.g. ‘productivity’, which hides the ‘space’ cluster) and labour-market research (e.g. ‘company’, ‘strategy’).

Figure 3. Network visualisation map generated with Vosviewer on word occurrences (n ≥ 10) in abstracts of the sample (n = 336).

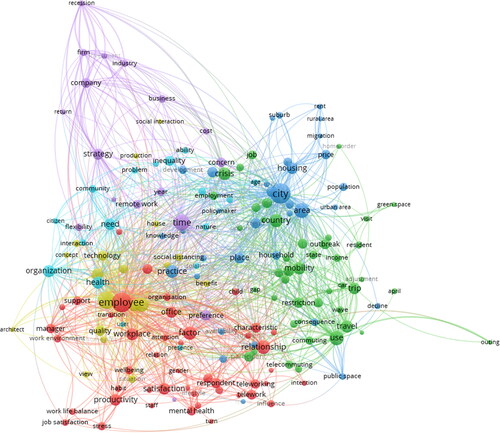

A second request () was performed on ‘highly relevant’ sources (occurrences 5 after excluding irrelevant words such as ‘paper’ and ‘researcher’). Although the clusters appear more intertwined, the spatial (e.g. ‘architecture’, ‘environment’) and housing-market (e.g. ‘demand’, ‘price’) dimensions are more prominent. Other clusters relate to urban aspects (‘area’ cluster, including ‘amenity’ and ‘density’) as well as living and working conditions (practice and activity clusters). These visualisations demonstrate that there is a gap to fill in design-oriented and policy- or governance-oriented housing and urban research on the studied topic. We have also created our map () of the themes and concepts used in the sample of highly relevant sources to provide the reader with an overview of the qualitative review.

4. Changes in urban live-work relationships under COVID-19

4.1. COVID-19 has accelerated the shift to hybrid work for those able to engage in it

The COVID-19 crisis has normalised WFH in advanced services and sectors of the knowledge and tech economies (Chapple & Schmahmann, Citation2023; Conway et al., Citation2020; Reuschke & Ekinsmyth, Citation2021). However, this trend has been more moderate than expected (e.g. in Montreal; Shearmur et al., Citation2021). Notably, fewer people are able—and allowed—to WFH than admitted in public opinion. The journalistic discourse during the pandemic has largely focused on homeworkers’ practices, yet an investigation of US newspapers found that their reporting of essential workers’ experiences helped contextualise the middle-class bias related to this discourse (Creech & Maddox, Citation2022). Blue-collar workers were either directly exposed to health risks or stayed home, unable to work; however, their work practices were affected one way or another (Vyas, Citation2022). WFH concerns predominantly highly-educated and higher-income workers with office-based employment in densely-populated areas—particularly urban areas with technology infrastructure and available jobs that can be performed virtually (Ceinar & Mariotti, Citation2021; Crowley & Doran, Citation2020; Dingel & Neiman, Citation2020; Doling & Arundel, Citation2020; Paul, Citation2022; Salon et al., Citation2021; Shearmur et al., Citation2021). During the pandemic, intensified WFH magnified socio-economic inequalities (e.g. according to race or gender; Gallent et al., Citation2022) and unequal access to digital services (Reddick et al., Citation2020).

Although increased virtual collaboration might stimulate ‘remote-by-design’ labour markets (Bonacini et al., Citation2021; Stephany et al., Citation2020), full-time telework has been strongly questioned given its issues in terms of boundaries, life satisfaction, productivity and creativity (Cho, Citation2020; Schieman & Badawy, Citation2020; Shearmur et al., Citation2021). Conversely, a shift to hybrid work for those able to is expected, with implications for workplaces and office markets. Despite high levels of office vacancy during the lockdowns and an increase in office conversions to housing or mixed-use buildings, COVID-19 appears to have reinforced the attractiveness of central business districts (Machline et al., Citation2022). Gibson et al. (Citation2022) even expected an affordability crisis for offices offering innovative community-building concepts. Some economists did foresee the relative return to a similar level of pre-pandemic use of office space by around 2023 (e.g. Paul Krugman; Kahn, Citation2022); however, workplaces’ roles (e.g. innovation, collaboration, creativity) and spatial distribution in cities should change (Kulik, Citation2021; Painter et al., Citation2021; Reuschke et al., Citation2021; Reuschke & Felstead, Citation2020). Although co-working spaces suffered from lockdowns in peripheral neighbourhoods, (Ceinar & Mariotti, Citation2021), they could improve remote workers’ quality of life (Mariotti, Giavarini, et al., Citation2022) by fulfilling new roles as symbols of labour markets’ flexibilisation and creative-city narratives (Pajević, Citation2021).

4.2. Attention to homeworkers’ living and working conditions has fuelled debates on home usage and post-pandemic housing design and policy

Successive lockdowns have accelerated changes in home usage, following the intense use of homes for various functions at the exclusion of any other location or possible coping strategy (De Decker, Citation2021; Gallent & Madeddu, Citation2021; Madeddu & Clifford, Citation2021; Preece, McKee, Flint, et al., 2021). Embedding work into the home has triggered ‘ambiguous meanings of home’ (Tunstall, Citation2023, p. 78) and requires negotiations of domestic boundaries (Gurney, Citation2020; Larrea-Araujo et al., Citation2021) and home orderings following specific social norms (Azevedo et al., Citation2022). Altering home-making and work-home boundaries can be done either through segmentation or integration, depending on factors such as tenure, wealth, household composition and—more broadly—(in)equitable housing systems (Goodwin et al., Citation2021).

Small housing units were not designed to accommodate multiple functions, including work (Blanc & Scanlon, Citation2022; Horne et al., Citation2020). Similarly, tenants who worked from home in shared housing arrangements faced privacy and noise issues and had to adapt physical spaces and reframe relationships with the other residents (Blanc & Scanlon, Citation2022). Such observations question the large-scale production of co-living and micro-apartments in cities over the last decade (Hubbard et al., Citation2021). WFH also placed pressure on the homes of growing families (e.g. in the UK; Hipwood, Citation2022). These difficulties caused psychological issues, especially for people with insecure tenure and little resources (Amerio et al., Citation2020; Bower et al., Citation2021). For instance, vulnerable renters in the private sector faced mental health issues related to the uncertainty and precarity inherent in their tenure and lower-quality living environment (Oswald et al., Citation2022; Waldron, Citation2022). More generally, the pandemic has worsened the affordability issues of financialised, market-driven housing provision (Üçoğlu et al., Citation2021). Inadequate workspace and small housing arrangements often concern young tenants (Luppi et al., Citation2021), whereas good-quality workspace is more common for male homeowners aged 55+ with socio-economic stability (Arroyo et al., Citation2021; Cuerdo-Vilches et al., Citation2021; Doling & Arundel, Citation2020). Therefore, the disruption to daily life caused by COVID-19 may reshape small housing arrangements for younger and lower-income groups (Preece, McKee, Robinson, et al., 2021).

The expansion of WFH has led to demand for more private residential space (Boesel et al., Citation2021) and affected residential location choices (Schwartz & Wachter, Citation2022; see next subsection). However, the need for more space conflicts with property price increases in large cities (Barinova et al., Citation2021; Buitelaar, Pen, et al., Citation2021; Xu, Citation2021) and their suburbs (Dolls et al., Citation2022) despite the uncertainty related to the combination of the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, inflation peaks and growing interest rates (Van Nieuwerburgh, Citation2023). In the UK, increased housing prices in suburban and rural areas are primarily driven by investment in second homes; however, other long-term effects are expected since housing is a preferred asset class in times of crisis (Gallent et al., Citation2022).

The above observations have fuelled discussions about what ‘post-pandemic housing’ should be as well as opportunities for policy changes that were previously deemed impossible (Baxter et al., Citation2021; Rogers & Power, Citation2020). During the pandemic, emergency measures were taken, such as housing the homeless (e.g. in Australia; Parsell et al., Citation2022), restricting the possibility of eviction (e.g. in the US; Benfer et al., Citation2022) and supporting mortgage holders (e.g. in the UK, Belgium and France; Tunstall, Citation2023). For the future, academics advocate for transition and adaptive spaces (Keenan, Citation2020; Valizadeh & Iranmanesh, Citation2021) and the integration of WFH in the ‘post-pandemic housing discourse’ through policy, normative and spatial adaptations (e.g. utility minimum regulation) to improve flexibility and resilience (Blanc & Scanlon, Citation2022; Cuerdo-Vilches et al., Citation2021; Horne et al., Citation2020). Following this discourse, housing regulations and standards should be reassessed to suit future lifestyles and needs (Blanc & Scanlon, Citation2022), such as by integrating appropriate workspaces—including in social housing—to contribute to a fairer economy (Holliss, Citation2021). Furthermore, Elrayies (Citation2022) pleaded for ‘pandemic-resilient’ housing that can accommodate several functions through adequate size and comfort, resilience to future shocks, adaptability and flexibility. Housing affordability, quality and tenure security should also be placed at the top of the policy agenda (Baxter et al., Citation2021; Bower et al., Citation2021; Buitelaar, Pen, et al., Citation2021; Callison et al., Citation2021; Gallent & Madeddu, Citation2021; Hof, Citation2021; Rosenberg et al., Citation2020; Waldron, Citation2022).

4.3. Hybrid work legitimates planning discourses and regulatory changes based on urban proximity, densification and mixed-use

Much like past health crises, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that urban density and proximity may become harmful in the case of poor design and inadequate services (Ceinar & Mariotti, Citation2021; Ellis et al., Citation2021). Density apprehension and the flexibility in residential choices for hybrid workers have fuelled concerns regarding decreased urban attractiveness (Balemi et al., Citation2021; Barinova et al., Citation2021; Dolls et al., Citation2022; Kahn, Citation2022; S. Liu & Su, Citation2021). The deconcentration of skilled jobs in urban areas might lead to residential relocations within commuting distance (Balemi et al., Citation2021; Denham, Citation2021; Doling & Arundel, Citation2020). Such an increased urban exodus would revive urban-rural dichotomies (Freudendal-Pedersen & Kesselring, Citation2021), challenge sustainable policy goals (Habib & Anik, Citation2021) and enhance ‘rural gentrification’ and ‘inefficient polycentrism’ (Delventhal et al., Citation2021; Denham, Citation2021).

Initial studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted low rates of relocations and smooth workplace shifts in the continuity of pre-pandemic trends (Buitelaar, Bastiaanssen, et al., Citation2021; Shearmur et al., Citation2021). However, in the US, real estate economists observed relocations from metropolitan areas towards their suburbs, with increased house and rent prices in these zones (Gupta et al., Citation2022; Van Nieuwerburgh, Citation2023). In Europe, academics have presented evidence of short-term relocations (i.e. demand for short-term rentals and second homes) in smaller cities and rural areas, especially for privileged classes working in the cultural and knowledge industries (Colomb & Gallent, Citation2022). However, such movements seem to have returned to pre-pandemic trends (Rowe et al., Citation2023). Lockdowns have also inclined digital nomads to temporarily relocate to places with easy access to welfare and health services (Holleran, Citation2022). Within metropolitan regions, the secondary cities with advanced broadband infrastructure and a high share of knowledge workers are more suitable to host remote workers (e.g. in the metropolitan region of Milan; Mariotti, Di Matteo, et al., Citation2022; Moser et al., Citation2022).

Nevertheless, the pandemic’s effects have been nuanced since the war in Ukraine—coupled with rising inflation and energy costs—is more likely to be a turning point (Colomb & Gallent, Citation2022). To date, suburban relocations have been more common in the US than in Europe (Mariotti, Di Matteo, et al., Citation2022), whilst the migration towards rural areas has been lower than media predictions (González-Leonardo et al., Citation2022). Moreover, people who are able to WFH (in a hybrid work mode) tend to maintain similar residential preferences, which have always included suburban locations (de Abreu e Silva, Citation2022; Jeong & Lim, Citation2023). Overall, metropolitan areas are better adapted to telework development (Irlacher & Koch, Citation2021; Reuschke & Felstead, Citation2020) and stimulate the mobility of highly skilled workers. Despite this, accelerated digitalisation and its effects on labour markets may reduce interregional migration (Barinova et al., Citation2021) and affect metropolitan dynamics in the long term.

Still, in response to the temporary disruptions of the pandemic, planning discourses based on new understandings of pre-pandemic principles—such as densification (coupled with more room for open space) and mixed-use development—have been conveyed, primarily in discourses situating COVID-19 within concerns about climate change (e.g. Grant, Citation2020). Despite the pandemic’s variegated territorial impact (de Rosa & Mannarini, Citation2021), the literature emphasises global principles such as ‘gentle density’ (Grant, Citation2020). Under WFH expansion, New Urbanism—which is based on mixed-use, compact, walkable and live-work neighbourhoods (see Section 2)—was both legitimated and criticised for creating attractive environments for affluent homeworkers and worsening socio-spatial inequality in lower-income neighbourhoods (Daniels, Citation2021; Zenkteler, Hearn, et al., Citation2022). Instead, planning policy should also focus on neighbourhoods where WFH is less likely (Zenkteler, Hearn, et al., Citation2022).

Similarly, public opinion has widely framed the pandemic as a catalyser of short live-work distances and the so-called ‘15-minute city’. This controversial concept and other proximity-based approaches to planning engage in the ‘chrono urbanism’ of the 1990s, which aimed to ensure access to essential services, including workplaces, local economic activities and green space (Abdelfattah et al., Citation2022; Di Marino et al., Citation2022). Some scholars have supported variations of this concept (e.g. ‘walkable’ and ‘20-minute neighbourhoods’) for large European cities to mitigate inequalities in urban services (Boussauw & De Boeck, Citation2022; Horne et al., Citation2020; Kato et al., Citation2021), whilst others have criticised it for exacerbating such inequalities (Oosterlynck & Beeckmans, Citation2021).

Moreover, academics defend a ‘post-pandemic’ city that is resilient to shocks and adaptive (Abd Elrahman, Citation2021; J. Liu et al., Citation2021; Pirlone & Spadaro, Citation2020; Vicino et al., Citation2022), favouring ‘deceleration’ and ‘degrowth’ (Freudendal-Pedersen & Kesselring, Citation2021). This pandemic-resilient city offers improved economic, social and physical conditions and policies for public health and housing provision (Nathan, Citation2021). Such discourses also apply to second-tier cities (Song et al., Citation2021) and value nature (Elrayies, Citation2022), social justice (Gallent & Madeddu, Citation2021; Oswald et al., Citation2022) and care (Angel & Blei, Citation2020; Ellis et al., Citation2021; Morrow & Parker, Citation2020). Conversely, the smart city discourse remains more timid (Kunzmann, Citation2020), drawing on older conceptions of ‘electronic urbanism’ (Charitonidou, Citation2021).

These discourses have consequences for planning policy and regulations. For some, urban regeneration strategies and planning regulations should integrate flexible uses and third places for remote workers in suburban environments (Glackin et al., Citation2022; Zenkteler, Foth, et al., Citation2022); however, this, once again, raises questions of inequality. More broadly, scholars advocate for planning systems that embrace complexity, uncertainty and adaptability (Muldoon‐Smith & Moreton, Citation2022), support live-work housing suitable for different kinds of work (Holliss, Citation2021) and envision broader scales (Vicino et al., Citation2022).

5. Research agenda

This paper identified current evidence and academic discourses regarding the effects of COVID-19 on urban live-work relationships to draw a research agenda for housing and urban studies. We considered the COVID-19 pandemic to be an exogenous shock contingent upon other shocks, embedded in a structural global housing crisis and accelerating the digitalisation and flexibilisation of living and working places. Past health and economic crises have all affected urban housing provision in one way or another and this one is no different; however, its embeddedness may complexify the identification of its effects between normalisation, adaptation and acceleration.

Our literature review of living and working in cities during the COVID-19 pandemic confirms that this crisis has firstly accelerated the shift towards hybrid work in urbanised areas with technology infrastructure, for those able to do so. This has enhanced the mutation of workplaces and resulted in spatial consequences. Secondly, increased attention to the living and working conditions of homeworkers has highlighted changes in home usage, the unsuitability of small and shared housing arrangements to such changes and the inequalities of WFH across tenure, gender and lifetime among other factors. Under rising property prices, post-pandemic housing discourses have supported normalisation through quality housing design and recalled the need for housing policies that address structural affordability and tenure security issues. Thirdly, hybrid work has legitimated planning discourses (adaptation) based on density, mixed use and short live-work distances, which are partly driven by environmental concerns. However, such models may exacerbate socio-spatial inequalities. Both housing and planning discourses draw on resilience as a central concept that is translated into flexibility and adaptability at different scales.

Based on these observations, we suggest a research agenda structured in three axes. The first axis concerns the conceptualisation of WFH and COVID-19 as a study object. First, although WFH has been studied across disciplines, ambiguity between WFH and home-based telework remains. The literature written since the beginning of the pandemic tends to assimilate the former into the latter. However, telework relies on the use of technology, whereas WFH could embrace any kind of work conducted at home, including unpaid work often carried out by women, as widely discussed in gender studies (e.g. Burchi, Citation2018). Such a broader, intersectional definition would help move beyond the inequalities inherent to telework and more inclusively reintegrate different types of work (e.g. productive activities) into different types of housing (e.g. social housing). Also, the way that WFH was experienced during the pandemic paradoxically corresponds to older forms of home-based telework; however, its expansion in the lockdown context required digital innovations (e.g. online meetings and seminar tools). The upscaling role of COVID-19 could be further analysed using innovation cycles, for example. Second, given the complex articulation between COVID-19 and other accumulated shocks and crises, we encourage prospective interdisciplinary research to discuss the pandemic’s long-term structural effects on living and working in cities. Although we know that the pandemic has reinforced existing live-work paradigms to date, we still have few indications of how they may evolve. What has been unanimously recognised as a short-term catalyser may appear more disruptive—or remain incremental—in the future. Efforts should be continued to understand COVID-19-related changes, their institutionalisation (e.g. through new actors or instruments) across different local institutional frameworks and their relationships with other disruptive events.

Moving to the second axis, we recommend housing studies to further compare actors’ policy responses to accumulated uncertainties in terms of housing provision in various housing systems. In the context of an enduring housing crisis, the pandemic offers opportunities to establish relevant policies and reduce implementation gaps—beyond emergency measures—that should not be missed. Another key aspect of the review is the need to explore how the pandemic may enable design principles and regulations that foster housing quality and resilience. In particular, the effects of WFH on housing provision in the context of ‘shrinking domesticities’ (Harris et al., Citation2023) deserve in-depth investigation. More broadly, the conceptualisation of housing as a ‘capital good’ (Doling & Arundel, Citation2020) requires experimenting with urban housing typologies that address the complex combination of issues relating to health, space needs, flexibility and shared amenities, beyond market and economic constraints. The same is true for ‘flexible’ workplaces—although those are not the focus of this paper. Moreover, qualitative indicators should be found to assess such typologies alongside the usual quantitative indicators.

Finally, the third research axis relates to planning issues, with an initial need for critical investigations of the opportunities and risks of WFH-oriented planning and urban regeneration strategies centred on remote workers, in terms of inequalities and urban commodification. Such planning principles and strategies should be challenged by exploring alternative ways of planning post-pandemic or pandemic-resilient cities and translating them into design tools and planning principles adapted to different planning regimes. Although many studies have analysed residential relocations during the pandemic at the metropolitan and regional scales, similar investigations should be continued in the future to challenge the ‘back to status quo’ assumption and improve knowledge of the post-pandemic geography of metropolitan living and working. Moreover, identifying possible reallocations of capital in second-tier cities and regions—as observed during the Spanish flu—would help in discussing opportunities for reducing inequalities at broader scales.

Overall, this article helps apprehend the state of the art and current academic discourses on the future of urban living and working by originally situating the discussion at the intersection of work, housing and planning whilst providing research perspectives that strengthen these links. Although our sampling choices have certain limitations and biases (e.g. the overrepresentation of Anglo-Saxon literature and occidental geographical areas) and our focus remains relatively broad, through a threefold research agenda, these choices allowed us to raise relevant questions for housing and urban studies following WFH expansion during the COVID-19 pandemic and stress the need for new conceptualisations and analytical frameworks to address these questions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Constance Uyttebrouck

Constance Uyttebrouck is a Research Associate at the Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research. She previously worked as a postdoctoral researcher at the KU Leuven on post-Covid housing supply in Brussels. She holds a Master’s in Architectural engineering (ULiège, 2011) and a PhD in Architecture and Urban Planning (ULiège, 2020). Her PhD involved studying the ontologies and governance of the ‘live-work mix’ in Amsterdam, Brussels and Stockholm. Her research interests lie in the governance of urban housing provision.

Pascal De Decker

Pascal De Decker is a Professor Emeritus in the Master’s Programme in Urbanism and Spatial Planning at the Department of Architecture, KU Leuven. He studied sociology (UGent, 1981) and urban and regional planning (UGent, 1985) and holds a PhD in Political and Social Sciences (UAntwerp, 2004). Beyond academic research, he also has long-standing experience in policy-making. His research interests concern the sociological and spatial dimensions of housing, urban planning and demographic developments.

Caroline Newton

Caroline Newton is an architect, urban planner and political scientist. She holds a PhD in Geography (KU Leuven). She is an Associate Professor at TU Delft, where she received the Van Eesteren Fellowship in 2019. Her research focuses on the socio-spatial dimensions of design and critical spatial practices in Europe and the Global South. Her research interests are centred on the interrelationship between social processes and the built environment.

Notes

1 The design of the SLM was built upon a preliminary media framing of COVID-19’s effects on urban live-work relationships.

2 (TITLE-ABS-KEY (("Housing" OR "Home" OR "House" OR "Dwelling") AND ("COVID-19" OR "Pandemic" OR "Coronavirus" OR "COVID")) AND ALL (("Telework" OR "Home office" OR "Remote work" OR "Home working" OR "Working from home") AND ("Urban" OR "City" OR "Cities" OR "Built environment" OR "Living environment" OR "Planning")))

AND (EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA," MEDI") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "COMP") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "MATH") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "BIOC") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "NURS") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "HEAL") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "AGRI") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "EART") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "NEUR") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "PHYS") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "PHAR") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "VETE") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "MATE") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "CENG") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "CHEM") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "IMMU") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "ENER")).

3 TS=((Housing OR Home OR House OR Dwelling) AND (COVID-19 OR Pandemic OR Coronavirus OR COVID) AND (Telework OR Home office OR Remote work OR Home working OR Working from home) AND (Urban OR City OR Cities OR Built environment OR Living environment OR Planning)).

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2015) The great moderation, the great excess and the global housing crisis, International Journal of Housing Policy, 15, pp. 43–60.

- Aalbers, M. B. (2017) The variegated financialization of housing, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, pp. 542–554.

- Abdelfattah, L., Deponte, D. & Fossa, G. (2022) The 15-minute city as a hybrid model for milan, TeMA Journal of Land Use Mobility and Environment, 1, pp. 71–86. https://www.progettaferrara.eu/it/b/2284/slides.

- Abd Elrahman, A. S. (2021) The fifth-place metamorphosis: The impact of the outbreak of COVID-19 on typologies of places in post-pandemic cairo, Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 15, pp. 113–130.

- Aguilera, A., Lethiais, V., Rallet, A. & Proulhac, L. (2016) Home-based telework in France: Characteristics, barriers and perspectives, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 92, pp. 1–11.

- Amerio, A., Brambilla, A., Morganti, A., Aguglia, A., Bianchi, D., Santi, F., Costantini, L., Odone, A., Costanza, A., Signorelli, C., Serafini, G., Amore, M. & Capolongo, S. (2020) COVID-19 lockdown : Housing built environment’s effects on mental health, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, pp. 5973–5910.

- Angel, S. & Blei, A. (2020) Why pandemics, such as covid‐19, require a metropolitan response, Sustainability, 13, pp. 79.

- Arroyo, R., Mars, L. & Ruiz, T. (2021) Activity participation and wellbeing during the covid-19 lockdown in Spain, International Journal of Urban Sciences, 25, pp. 386–415.

- Azevedo, S., Kohout, R., Rogojanu, A. & Wolfmayr, G. (2022) Homely orderings in times of stay-at-home measures: Pandemic practices of the home, Home Cultures, 19, pp. 193–218.

- Balemi, N., Füss, R. & Weigand, A. (2021) COVID-19’s impact on real estate markets: Review and outlook, Financial Markets and Portfolio Management, 35, pp. 495–513.

- Barinova, V., Rochhia, S. & Zemtsov, S. (2021) Attracting highly skilled migrants to the Russian regions, Regional Science Policy & Practice, 14, November 2020,pp. 147–173.

- Basco, S., Domènech, J. & Rosés, J. R. (2022) Pandemics, Economics and Inequality: Lessons from the Spanish Flu (Deng Kent, Ed.) (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Studies in Economic History).

- Baxter, J., Cobb-Clark, D., Cornish, A., Ho, T., Kalb, G., Mazerolle, L., Parsell, C., Pawson, H., Thorpe, K., De Silva, L. & Zubrick, S. R. (2021) Never let a crisis go to waste: Opportunities to reduce social disadvantage from COVID-19, Australian Economic Review, 54, pp. 343–358.

- Benfer, E. A., Koehler, R., Mark, A., Nazzaro, V., Alexander, A. K., Hepburn, P., Keene, D. E. & Desmond, M. (2022) COVID-19 housing policy: State and federal eviction moratoria and supportive measures in the United States during the pandemic, Housing Policy Debate, 33, pp. 1390–1414.

- Bergan, T. L., Gorman-Murray, A. & Power, E. R. (2020) Coliving housing: Home cultures of precarity for the new creative class, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1204–1222.

- Blanc, F. & Scanlon, K. (2022) Sharing a home under lockdown in London, Buildings and Cities, 3, pp. 118–133.

- Boelhouwer, P. (2017) The role of government and financial institutions during a housing market crisis: A case study of The Netherlands, International Journal of Housing Policy, 17, pp. 591–602.

- Boesel, M., Chen, S. & Nothaft, F. E. (2021) Housing preferences during the pandemic: Effect on home price, rent, and inflation measurement, Business Economics (Cleveland, Ohio), 56, pp. 200–211.

- Boin, A. (2009) The new world of crises and crisis management: Implications for policymaking and research, Review of Policy Research, 26, pp. 367–377.

- Bonacini, L., Gallo, G. & Scicchitano, S. (2021) Working from home and income inequality: Risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19, Journal of Population Economics, 34, pp. 303–360.

- Bontje, M., Musterd, S. & Sleutjes, B. (2017) Skills and cities: Knowledge workers in Northwest-European cities, International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development, 8, pp. 135–153.

- Boussauw, K. & De Boeck, S. (2022) De 15 minutenstad als ruimtelijke kapstok voor de ‘essentiële economie.’ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358003274_De_15_minutenstad_als_ruimtelijke_kapstok_voor_de_%27essentiele_economie%27

- Bower, M., Buckle, C., Rugel, E., Donohoe-Bales, A., McGrath, L., Gournay, K., Barrett, E., Phibbs, P. & Teesson, M. (2021) ‘Trapped’, ‘anxious’ and ‘traumatised’: COVID-19 intensified the impact of housing inequality on Australians’ mental health, International Journal of Housing Policy, 23, pp. 260–291.

- Buitelaar, E., Bastiaanssen, J., Hilbers, H., Hoen, M. ‘., Husby, T., Lennartz, C., Slijkerman, N., van der Staak, M., Snelle, D. & Weterings, A. (2021) Thuiswerken en de gevolgen voor wonen, werken en mobiliteit. https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/pbl-2021-thuiswerken-en-de-gevolgen-voor-wonen-werken-en-mobiliteit-4686.pdf

- Buitelaar, E., Pen, C. & van den Hurk, M. (2021) Ruimtelijke dynamiek in wonen en werken. Een synthese van onderzoek naar continuïteit en verandering. https://www.verdus.nl/ruimtelijke-dynamiek-in-wonen-en-werken-een-synthese-van-onderzoek-naar-continuiteit-en-verandering/

- Burchi, S. (2018) Economias domésticas. Trabalhar em casa em tempos de precariedade. Novas profissões e espaços de vida, Laplage EM Revista, 4, pp. 21–35.

- Callison, K., Finger, D. & Smith, I. M. (2021) COVID-19 eviction moratoriums and eviction filings: Evidence from New Orleans, Housing and Society, 49, pp. 1–9.

- Capano, G., Howlett, M., Jarvis, D. S. L. & Ramesh, M. (2022) Long-term policy impacts of the coronavirus: Normalization, adaptation, and acceleration in the post-COVID state, Policy and Society, 41, pp. 1–12.

- Ceinar, I. M. & Mariotti, I. (2021) The effects of covid-19 on coworking spaces: Patterns and future trends, in: I. Mariotti, S. Di Vita, & M. Akhavan (Eds) New Workplaces—Location Patterns, Urban Effects and Development Trajectories. A worldwide investigation, p. 112 (Switzerland: Springer Cham).

- Chapple, K. & Schmahmann, L. (2023) Can we “claim” the workforce? A Labor-Focused agenda for economic development in the face of an uncertain future, Economic Development Quarterly, 37, pp. 14–19.

- Charitonidou, M. (2021) Takis zenetos’s electronic urbanism and tele-activities: Minimizing transportation as social aspiration, Urban Science, 5, pp. 31.

- Cho, E. (2020) Examining boundaries to understand the impact of COVID-19 on vocational behaviors, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, pp. 103437.

- Colomb, C. & Gallent, N. (2022) Post-COVID-19 mobilities and the housing crisis in European urban and rural destinations. Policy challenges and research agenda, Planning Practice & Research, 37, pp. 624–641.

- Conway, M. W., Salon, D., da Silva, D. C. & Mirtich, L. (2020) How will the COVID-19 pandemic affect the future of urban life? Early evidence from highly-educated respondents in the United States, Urban Science, 4, pp. 50.

- Corburn, J. (2005) Urban planning and health disparities: Implications for research and practice, Planning Practice and Research, 20, pp. 111–126.

- Corburn, J. (2007) Reconnecting with our roots. Amercian urban planning and public health in the twenty-first century, Urban Affairs Review, 42, pp. 688–713.

- Creech, B. & Maddox, J. (2022) Of essential workers and working from home: Journalistic discourses and the precarities of a pandemic economy, Journalism, 23, pp. 2533–2551.

- Crowley, F. & Doran, J. (2020) Covid‐19, occupational social distancing and remote working potential: An occupation, sector and regional perspective, Regional Science Policy & Practice, 12, pp. 1211–1234.

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T., Navas-Martín, M. Á., March, S. & Oteiza, I. (2021) Adequacy of telework spaces in homes during the lockdown in Madrid, according to socioeconomic factors and home features, Sustainable Cities and Society, 75, pp. 103262.

- Daniels, T. L. (2021) Re-designing America’s suburbs for the age of climate change and pandemics, Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 3, pp. 225–236.

- de Abreu e Silva, J. (2022) Residential preferences, telework perceptions, and the intention to telework: Insights from the Lisbon metropolitan area during the COVID-19 pandemic, Regional Science Policy & Practice, 14, pp. 142–161.

- De Decker, P. (2021) Wonen in tijden van pandemie, in: L. Beeckmans, S. Oosterlynck, & E. Corijn (Eds) De stad beter na corona? reflecties over een gezondere en meer rechtvaardige stad, pp. 99–106 (Brussels, BE: VUB Press).

- Delventhal, M. J., Kwon, E. & Parkhomenko, A. (2021) How do cities change when we work from home?, Journal of Urban Economics, 127, June 2020, pp. 103331.

- Denham, T. (2021) The limits of telecommuting: Policy challenges of counterurbanisation as a pandemic response, Geographical Research, 59, April, pp. 514–521.

- de Rosa, A. S. & Mannarini, T. (2021) Covid-19 as an “invisible other” and socio-spatial distancing within a one-metre individual bubble, URBAN DESIGN International, 26, pp. 370–390.

- de Vos, D., Meijers, E. & van Ham, M. (2018) Working from home and the willingness to accept a longer commute, The Annals of Regional Science, 61, pp. 375–398.

- Di Marino, M., Tomaz, E., Henriques, C. & Chavoshi, S. H. (2022) The 15-minute city concept and new working spaces: A planning perspective from Oslo and Lisbon, European Planning Studies, 31, pp. 598–620.

- Dingel, J. I. & Neiman, B. (2020) How many jobs can be done at home?, Journal of Public Economics, 189, pp. 104235.

- Doling, J. & Arundel, R. (2020) The home as workplace: A challenge for housing research, Housing, Theory and Society, 39, pp. 1–20.

- Dolls, M., Gstrein, D., Krolage, C. & Neumeier, F. (2022) How do taxation and regulation affect the real estate market?, Big-Data-Based Economic Insights, 23, pp. 65–69.

- Dupont, C., Oberthür, S. & von Homeyer, I. (2020) The covid-19 crisis: A critical juncture for EU climate policy development?, Journal of European Integration, 42, pp. 1095–1110.

- Ellis, G., Grant, M., Brown, C., Teixeira Caiaffa, W., Shenton, F. C., Lindsay, S. W., Dora, C., Nguendo-Yongsi, H. B. & Morgan, S. (2021) The urban syndemic of COVID-19: Insights, reflections and implications, Cities & Health, 5, pp. S1–S11.

- Elrayies, G. M. (2022) Prophylactic architecture: Formulating the concept of pandemic‐resilient homes, Buildings, 12, pp. 927.

- Felstead, A., Jewson, N., Phizacklea, A. & Walters, S. (2002) The option to work at home: Another privilege for the favoured few?, New Technology, Work and Employment, 17, pp. 204–223.

- Ferm, J. & Jones, E. (2016) Mixed-use ‘regeneration’ of employment land in the post-industrial city: Challenges and realities in London, European Planning Studies, 24, pp. 1913–1936.

- Francke, M. & Korevaar, M. (2021) Housing markets in a pandemic: Evidence from historical outbreaks, Journal of Urban Economics, 123, pp. 103333.

- Freudendal-Pedersen, M. & Kesselring, S. (2021) What is the urban without physical mobilities? COVID-19-induced immobility in the mobile risk society, Mobilities, 16, pp. 81–95.

- Gallent, N. & Madeddu, M. (2021) Covid-19 and london’s decentralising housing market–what are the planning implications?, Planning Practice & Research, 36, pp. 567–577.

- Gallent, N., Stirling, P. & Hamiduddin, I. (2022) Pandemic mobility, second homes and housing market change in a rural amenity area during COVID-19 – The Brecon Beacons National Park, Wales, Progress in Planning, 172, pp. 100731.

- Gibson, C., Brennan-Horley, C., Cook, N., McGuirk, P., Warren, A. & Wolifson, P. (2022) The post-pandemic Central business district (CBD): Re-Imagining the creative city?, Urban Policy and Research, 41, pp. 210–223.

- Glackin, S., Moglia, M. & Newton, P. (2022) Working from home as a catalyst for urban regeneration, Sustainability, 14, pp. 12584.

- González-Leonardo, M., Rowe, F. & Fresolone-Caparrós, A. (2022) Rural revival? The rise in internal migration to rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Who moved and where?, Journal of Rural Studies, 96, pp. 332–342.

- Goodwin, B., Webber, N., Baker, T. & Bartos, A. E. (2021) Working from home: Negotiations of domestic functionality and aesthetics, International Journal of Housing Policy, 23, pp. 47–69.

- Grant, J. L. (2020) Pandemic challenges to planning prescriptions: How covid-19 is changing the ways we think about planning, Planning Theory & Practice, 21, pp. 659–667.

- Gupta, A., Mittal, V., Peeters, J. & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2022) Flattening the curve: Pandemic-Induced revaluation of urban real estate, Journal of Financial Economics, 146, pp. 594–636.

- Gurney, C. (2020) Out of harm’s way ? Critical remarks on harm and the meaning of home during the 2020 COvid-19 social distancing measures (UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence, Issue April). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340635002%0AOut

- Gurney, C. (2021) Dangerous liaisons? Applying the social harm perspective to the social inequality, housing and health trifecta during the covid-19 pandemic, International Journal of Housing Policy, 23, pp. 232–259.

- Habib, M. A. & Anik, M. A. H. (2021) Examining the long term impacts of COVID-19 using an integrated transport and land-use modelling system, International Journal of Urban Sciences, 25, pp. 323–346.

- Harris, E. & Nowicki, M. (2020) “GET SMALLER”? Emerging geographies of micro-living, Area, 52, pp. 591–599.

- Harris, E., Nowicki, M., & White, T. (Eds) (2023) The Growing Trend of Living Small. A Critical Approach to Shrinking Domesticities (Oxon and New York: Routledge).

- Heslop, J. & Ormerod, E. (2020) The politics of crisis: Deconstructing the dominant narratives of the housing crisis, Antipode, 52, pp. 145–163.

- Hipwood, T. (2022) Adapting owner-occupied dwellings in the UK: Lessons for the future, Buildings and Cities, 3, pp. 297–315.

- Hochstenbach, C. & Ronald, R. (2020) The unlikely revival of private renting in Amsterdam: Re-regulating a regulated housing market, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52, pp. 1622–1642.

- Hof, D. (2021) Home dispossession and commercial real estate dispossession in tourist conurbations. Analyzing the reconfiguration of displacement dynamics in los cristianos/las américas (tenerife), Urban Science, 5, pp. 30.

- Hogan, J., Howlett, M. & Murphy, M. (2022) Re-thinking the coronavirus pandemic as a policy punctuation: COVID-19 as a path-clearing policy accelerator, Policy and Society, 41, pp. 40–52.

- Holleran, M. (2022) Pandemics and geoarbitrage: Digital nomadism before and after COVID-19, City, 26, pp. 831–847.

- Holliss, F. (2021) Working from home, Built Environment, 47, pp. 367–379.

- Horne, R., Willand, N., Dorignon, L. & Middha, B. (2020) The lived experience of COVID-19: Housing and household resilience, AHURI Final Report.

- Hubbard, P., Reades, J. & Walter, H. (2021) Housing: Shrinking homes, COVID-19 and the challenge of homeworking, Town Planning Review, 92, pp. 3–10.

- Hutton, T. A. (2009) Trajectories of the new economy: Regeneration and dislocation in the inner city, Urban Studies, 46, pp. 987–1001.

- Irlacher, M. & Koch, M. (2021) Working from home, wages, and regional inequality in the light of COVID-19, Jahrbücher Für Nationalökonomie Und Statistik, 241, pp. 373–404.

- Jeong, K. & Lim, J. (2023) Would people prefer city-center living in the post-COVID era?: Experience, status, and attitudes to social disasters, Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 50, pp. 1932–1946.

- Kahn, M. (2022) Introduction. No going back, in: Going Remote : How the Flexible Work Economy Can Improve Our Lives and Our Cities (Oakland, CA: University of California Press).

- Kato, H., Takizawa, A. & Matsushita, D. (2021) Impact of covid-19 pandemic on home range in a suburban city in the Osaka metropolitan area, Sustainability (Switzerland), 13, pp. 8974.

- Keenan, J. M. (2020) COVID, resilience, and the built environment, Environment Systems & Decisions, 40, pp. 216–221.

- Krieger, J. & Higgins, D. L. (2002) Housing and health: Time again for public health action, American Journal of Public Health, 92, pp. 758–768.

- Kulik, C. T. (2021) We need a hero: HR and the ‘next normal’ workplace, Human Resource Management Journal, 32, August 2020,pp. 216–231.

- Kunzmann, K. R. (2020) Smart cities after covid-19: Ten narratives, disP - the Planning Review, 56, pp. 20–31.

- Larrea-Araujo, C., Ayala-Granja, J., Vinueza-Cabezas, A. & Acosta-Vargas, P. (2021) Ergonomic risk factors of teleworking in Ecuador during the covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, pp. 5063.

- Liu, J., Gross, J. & Ha, J. (2021) Is travel behaviour an equity issue? Using GPS location data to assess the effects of income and supermarket availability on travel reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic, International Journal of Urban Sciences, 25, pp. 366–385.

- Liu, S. & Su, Y. (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the demand for density: Evidence from the U.S. housing market, Economics Letters, 207, pp. 110010.

- Luppi, F., Rosina, A. & Sironi, E. (2021) On the changes of the intention to leave the parental home during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison among five European countries, Genus, 77, pp. 1–23.

- Machline, E., Pearlmutter, D., Cohen, C. & Schwartz, M. (2022) COVID-19: A catalyst for revitalizing mixed-use urban centers? The case of Paris, Building Research & Information, 51, pp. 39–55.

- Madden, D. & Marcuse, P. (2016) In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis (1st ed.) (London and Brooklyn: Verso).

- Madeddu, M. & Clifford, B. (2021) Housing quality, permitted development and the role of regulation after COVID-19, Town Planning Review, 92, pp. 41–48.

- Mariotti, I., Di Matteo, D. & Rossi, F. (2022) Who were the losers and winners during the covid-19 pandemic? The rise of remote working in suburban areas, Regional Studies, Regional Science, 9, pp. 685–708.

- Mariotti, I., Giavarini, V., Rossi, F. & Akhavan, M. (2022) Exploring the “15-minute city” and near working in Milan using mobile phone data, TeMA Journal of Land Use Mobility and Environment, 2, pp. 39–56. www.tema.unina.it

- McKie, R. (1974) Cellular renewal : A policy for the older housing areas, Town Planning Review, 45, pp. 274–290.

- Meijer, R. & Jonkman, A. (2020) Land-policy instruments for densification: The Dutch quest for control, Town Planning Review, 91, pp. 239–258.

- Messenger, J. C. & Gschwind, L. (2016) Three generations of telework: New ICTs and the (R)evolution from home office to virtual office, New Technology, Work and Employment, 31, pp. 195–208.

- Morrow, O. & Parker, B. (2020) Care, commoning and collectivity: From grand domestic revolution to urban transformation, Urban Geography, 41, pp. 607–624.

- Moser, J., Wenner, F. & Thierstein, A. (2022) Working from home and covid‐19: Where could residents move to?, Urban Planning, 7, pp. 15–34.

- Muldoon‐Smith, K. & Moreton, L. (2022) Planning adaptation: Accommodating complexity in the built environment, Urban Planning, 7, pp. 44–55.

- Nathan, M. (2021) The city and the virus, Urban Studies, 60, pp. 1346–1364.

- Nayar, K. R. (1997) Housing amenities and health improvement: Some findings, Economic and Political Weekly, 32, pp. 1275–1279. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4405459

- Oosterlynck, S. & Beeckmans, L. (2021) De sociale bijziendheid van de 15 minutenstad, Ruimte & Maatschappij, 13, pp. 63–74.

- Oswald, D., Moore, T. & Baker, E. (2022) Exploring the well-being of renters during the COVID-19 pandemic, International Journal of Housing Policy, 23, pp. 292–312.

- Painter, D. T., Shutters, S. T. & Wentz, E. (2021) Innovations and economic output scale with social interactions in the workforce, Urban Science, 5, pp. 21.

- Pajević, F. (2021) The tetris office: Flexwork, real estate and city planning in silicon valley North, Canada, Cities, 110, pp. 103060.

- Parsell, C., Clarke, A. & Kuskoff, E. (2022) Understanding responses to homelessness during COVID-19: An examination of Australia, Housing Studies, 38, pp. 8–21.

- Paul, J. (2022) Work from home behaviors among U.S. urban and rural residents, Journal of Rural Studies, 96, pp. 101–111.

- Pirlone, F. & Spadaro, I. (2020) COVID-19 vs CITY-20. Scenarios, insights, reasoning and research. The resilient city and adapting to the health emergency, Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, TeMA Special Issue, pp. 305–314.

- Preece, J., McKee, K., Flint, J. & Robinson, D. (2021) Living in a small home: Expectations, impression management, and compensatory practices, Housing Studies, 38, pp. 1824–1844.

- Preece, J., McKee, K., Robinson, D. & Flint, J. (2021) Urban rhythms in a small home: COVID-19 as a mechanism of exception, Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 60, pp. 1650–1667. 004209802110181.

- Rader Olsson, A. & Cars, G. (2011) Polycentric spatial development: Institutional challenges to intermunicipal cooperation, Jahrbuch Für Regionalwissenschaft, 31, pp. 155–171.

- Reddick, C. G., Enriquez, R., Harris, R. J. & Sharma, B. (2020) Determinants of broadband access and affordability: An analysis of a community survey on the digital divide, Cities (London, England), 106, pp. 102904.

- Reuschke, D. & Ekinsmyth, C. (2021) New spatialities of work in the city, Urban Studies, 58, pp. 2177–2187. March, 004209802110091.

- Reuschke, D. & Felstead, A. (2020) Changing workplace geographies in the COVID-19 crisis, Dialogues in Human Geography, 10, pp. 208–212.

- Reuschke, D., Long, J. & Bennett, N. (2021) Locating creativity in the city using twitter data, Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 48, pp. 2607–2622.

- Rogers, D. & Power, E. (2020) Housing policy and the COVID-19 pandemic: The importance of housing research during this health emergency, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 177–183.

- Rosenberg, A., Keene, D. E., Schlesinger, P., Groves, A. K. & Blankenship, K. M. (2020) COVID-19 and hidden housing vulnerabilities: Implications for health equity, new haven, Connecticut, AIDS and Behavior, 24, pp. 2007–2008.

- Rowe, F., Calafiore, A., Arribas-Bel, D., Samardzhiev, K. & Fleischmann, M. (2023) Urban exodus? Understanding human mobility in Britain during the COVID-19 pandemic using Meta-Facebook data, Population, Space and Place, 29, pp. e2637.

- Salon, D., Conway, M. W., da Silva, D. C., Chauhan, R. S., Derrible, S., Mohammadian, A., Khoeini, S., Parker, N., Mirtich, L., Shamshiripour, A., Rahimi, E. & Pendyala, R. M. (2021) The potential stickiness of pandemic-induced behavior changes in the United States, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118, pp. 1–3.

- Sassen, S. (1991) The Global City. New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton University Press.

- Schieman, S. & Badawy, P. J. (2020) The status dynamics of role blurring in the time of COVID-19, Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 6, pp. 2378023120944358.

- Schwartz, A. E. & Wachter, S. (2022) COVID-19’s impacts on housing markets: Introduction, Journal of Housing Economics, 59, pp. 101911.

- Shearmur, R., Ananian, P., Lachapelle, U., Parra-Lokhorst, M., Paulhiac, F., Tremblay, D.-G. & Wycliffe-Jones, A. (2021) Towards a post-COVID geography of economic activity: Using probability spaces to decipher Montreal’s changing workscapes, Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 59, 004209802110228. pp. 2053–2075.

- Soaita, A. M., Serin, B. & Preece, J. (2020) A methodological quest for systematic literature mapping, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 320–343.

- Song, X., Cao, M., Zhai, K., Gao, X., Wu, M. & Yang, T. (2021) The effects of spatial planning, well-Being, and behavioural changes during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 3, pp. 1–15.

- Sorensen, A. (2015) Taking path dependence seriously: An historical institutionalist research agenda in planning history, Planning Perspectives, 30, pp. 17–38.

- Stephany, F., Dunn, M., Sawyer, S. & Lehdonvirta, V. (2020) Distancing bonus or downscaling loss? The changing livelihood of Us online workers in times of COVID-19, Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 111, pp. 561–573.

- Taşan-Kok, T., Özogul, S. & Legarza, A. (2021) After the crisis is before the crisis : Reading property market shifts through Amsterdam’s changing landscape of property investors, European Urban and Regional Studies, 28, pp. 375–394.

- Tromp, F. (2020) Co-living beperkt zich niet meer alleen tot starters. [Co-living does not only limit itself to starters anymore]. Vastgoed Journaal. https://vastgoedjournaal.nl/news/44204/co-living-beperkt-zich-niet-meer-alleen-tot-starters

- Tunstall, B. (2023) Stay Home. Housing and Home in the UK during the COVID-19 Pandemic (Bristol, UK: Bristol University Press).

- Üçoğlu, M., Keil, R. & Tomar, S. (2021) Contagion in the markets? Covid-19 and housing in the greater Toronto area, Built Environment, 47, pp. 355–366.

- Uyttebrouck, C., De Decker, P. & Teller, J. (2021) Ontologies of live-work mix in Amsterdam, Brussels and Stockholm: An institutionalist approach drawing on path dependency, European Planning Studies, 30, pp. 705–724.

- Uyttebrouck, C., Remøy, H. & Teller, J. (2021) The governance of live-work mix : Actors and instruments in Amsterdam and Brussels development projects, Cities, 113, pp. 103161.

- Uyttebrouck, C., Wilmotte, P.-F. & Teller, J. (2022) Le télétravail à bruxelles avant la crise de la covid-19, Revue D’Économie Régionale & Urbaine, Février, pp. 115–142.

- Valizadeh, P. & Iranmanesh, A. (2021) Inside out, exploring residential spaces during COVID-19 lockdown from the perspective of architecture students, European Planning Studies, 30, pp. 211–226.

- van Meel, J. & Vos, P. (2001) Funky offices: Reflections on office design in the ‘new economy, Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 3, pp. 322–334.

- Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2023) The remote work revolution: Impact on real estate values and the urban environment, Real Estate Economics, 51, pp. 7–48.

- Vicino, T. J., Voigt, R. H., Kabir, M. & Michanie, J. (2022) Urban crises and the covid‐19 pandemic: An analytical framework for metropolitan resiliency, Urban Planning, 7, pp. 4–14.

- Vyas, L. (2022) “New normal” at work in a post-COVID world: Work–life balance and labor markets, Policy and Society, 41, pp. 155–167.

- Waldron, R. (2022) Experiencing housing precarity in the private rental sector during the covid-19 pandemic: The case of Ireland, Housing Studies, 38, pp. 84–106.

- Wijburg, G. (2021) The governance of affordable housing in post-crisis Amsterdam and Miami, Geoforum, 119, pp. 30–42.

- Xu, J. (2021) Analysis on the Effect of COVID-19 on Metro Seattle Residential Property Value. Proceedings - 2021 2nd International Conference on Urban Engineering and Management Science, ICUEMS 2021, 96–102.

- Zenkteler, M., Foth, M. & Hearn, G. (2022) Lifestyle cities, remote work and implications for urban planning, Australian Planner, 58, pp. 25–35.

- Zenkteler, M., Hearn, G., Foth, M. & McCutcheon, M. (2022) Distribution of home-based work in cities: Implications for planning and policy in the pandemic era, Journal of Urban and Regional Analysis, 14, pp. 187–210.