Abstract

People spend a substantial amount of time at home, so it is important that homes are safe, healthy environments. Damp and mould represent common housing problems but little is known about their potential psychological effects. This scoping review explores existing literature on the relationship between household damp/mould and psychological wellbeing. Systematic searches of six databases were conducted, supplemented by hand-searches. Thirty studies were included; 21/24 (87.5%) found significant univariate associations between damp/mould and psychological outcomes and 13/17 (76.5%) found that damp/mould remained significant independent predictors in multivariate analyses. Qualitative data from six studies revealed that participants feared potential physical health consequences of damp/mould and felt self-conscious about clothes/homes smelling damp. Our findings suggest that exposure to damp and mould accounts for a significant amount of variance in psychological outcomes. Improving housing quality, ensuring healthcare professionals are aware of the psychological health effects of damp/mould and campaigns to educate the public about how to remove damp and mould may be useful.

Keywords:

Introduction

Globally, people spend much of their time at home. In the early 2000s, studies from Germany, Canada and the United States estimated that the average person spent around 65% of their time at home (Brasche & Bischof, Citation2005; Leech et al., Citation2002). This proportion is likely to have substantially increased since the COVID-19 outbreak in December 2019 with stay-at-home orders across the world (Mathieu et al., Citation2020) effectively forcing people to spend much of their time in their homes. Despite mobility restrictions being eased, many people are still spending much of their time at home - for example, in the United Kingdom, over 80% of workers report planning to continue working from home at least some of the time (Office for National Statistics, Citation2022). Therefore given the current circumstances following the COVID-19 pandemic, with individuals spending more time at home than ever before, it becomes increasingly crucial for homes to be safe and healthy environments.

The interconnection between health and the built environment (encompassing the physical structures and surroundings in which individuals live) within communities is well-established, with housing impacting not only physical wellbeing but also overall quality of life (Bonnefoy, Citation2007; Shaw, Citation2004) and shaping individuals’ behaviour, relationships, and experiences (Patel, Citation2022; Rashidfarokhi & Danivska, Citation2023). As an essential component of the built environment, housing serves as more than just a shelter, providing individuals with safety, privacy, security, and comfort. People develop emotional and meaningful relationships with their homes (Kearns et al., Citation2000; Shaw, Citation2004) which contribute to social resilience (Patel, Citation2022).

Housing is widely recognised as a social determinant of health; it has even been argued that housing is the most powerful determinant of health (Leifheit et al., Citation2022). There are a number of ways in which the quality and conditions of housing (or lack of housing) can substantially impact both physical and mental health (Rolfe et al., Citation2020). Emotional aspects of the home, physical housing conditions, and the social environment of the neighbourhood where the house is located all affect health and wellbeing (Novoa et al., Citation2014). For example, good housing conditions - including clean air, access to clean water, and protection from environmental hazards - are essential for preventing communicable diseases and respiratory problems, while poor housing conditions can exacerbate physical health problems (Krieger & Higgins, Citation2002). Insecure housing, living in unsafe neighbourhoods and unhealthy housing conditions also contribute to stress and mental health problems, and neighbourhood quality (including the quality of social relationships with others in the local area) is also an important determinant of wellbeing (Rolfe et al., Citation2020).

The impact of housing on health is particularly prominent at intersections of socioeconomic status, race, gender, sexual orientation and immigration status (Dewilde, Citation2022; Leifheit et al., Citation2022; Vásquez-Vera et al., Citation2022). The structural oppression of certain groups and unequal distribution of power and resources means that communities who are marginalised at any of these intersections are disproportionately affected by limited or uncertain access to adequate housing and consequently poorer health (Leifheit et al., Citation2022). For example, research suggests that the health of cisgender women, transgender individuals and non-binary individuals is more severely affected by housing problems than that of cisgender men, potentially due to the patriarchal systems operating in society which make these groups more susceptible to living in precarious housing conditions (Vásquez-Vera et al., Citation2022). It has also been suggested that Black communities experience greater barriers to housing security (Leifheit et al., Citation2022), in part due to historical injustices such as the denial of mortgages for majority-Black neighbourhoods in the United States (Leifheit et al., Citation2022) and the institutional discrimination in the United Kingdom which historically saw Black and other minority ethnic households being more likely to be offered poor quality homes (King, Citation2021).

There are a number of housing-related problems that people may experience, such as overcrowding, cold, damp and mould, infestation, noise from neighbours, insufficient light, and inadequate heating (Pevalin et al., Citation2008). Household damp and mould have attracted particular attention from the media in the United Kingdom since 2022 due to the ‘cost-of-living’ crisis (e.g. Anderson, Citation2022; Phillips, Citation2022), in which increased energy prices have led many households to avoid switching the heating on to keep energy bills affordable. While avoiding heating a home may reduce bills, inhabitants are subsequently less likely to open windows (in order to conserve heat), which increases the risk of mould and damp developing (Sharpe et al., Citation2015). Socioeconomic status and behaviours to mitigate the effects of fuel poverty are of course not the only causes of household damp and mould; poor construction, severe weather events such as flooding, and inadequate maintenance of the home are also causal factors (Coulburn & Miller, Citation2022). Concerns about climate change have also brought attention to the risks of damp and mould, as changes in temperature and humidity may result in conditions favourable for mould growth (Hayles et al., Citation2022) and climate change mitigation policies which focus on energy efficiency in indoor dwellings could reduce ventilation rates and promote mould growth (Vardoulakis et al., Citation2015).

The prevalence of damp and mould in homes varies from country to country depending on climate and housing stock. In the two years to 2019, around 3% of households in England were reported to have damp in at least one room (UK Government, Citation2020); until more recent statistics are published, it is unclear how much impact the cost-of-living crisis may have on the prevalence of damp, mouldy homes in the United Kingdom. In a 2007 study of eight European cities, the World Health Organization (Citation2007) found visible mould growth in approximately 25% of the homes surveyed. Prevalence of mould in homes in the United States varies from study to study, averaging out to an estimate of around 50% of homes affected (Indoor Air Quality Scientific Findings Resource Bank: Berkeley Lab, Citation2023). It is also important to note the intersections of race and socioeconomic status with household damp and mould: unhealthy housing has been found to disproportionately affect ethnic and racial minorities, and those with low income (Tilburg, Citation2017). In the United Kingdom, whilst 3% of White British households were reported to have damp problems, this rose to 8% of Pakistani households, 9% of Black African households, 10% of Bangladeshi households and 13% of Mixed White and Black Caribbean households (UK Government, Citation2020). Additionally, people in rented homes – who tend to have lower incomes than those who own their homes – are significantly more likely to experience damp (Ellaway & Macintyre, Citation1998).

The presence of mould in the home has been associated with lower self-reported health (Adamkiewicz et al., Citation2014); neurological, skin and allergic symptoms and mucosal irritation (Tuuminen & Rinne, Citation2017); respiratory complaints, eye symptoms, and mucous membrane irritation (Portnoy et al., Citation2005); asthma (Moses et al., Citation2019); headaches, memory problems, nosebleeds, and body aches (Žuškin et al., Citation2009). Early-life exposure to mould has been associated with poorer cognitive function (Jedrychowski et al., Citation2011) and asthma, wheeze, allergic rhinitis and eczema (Du et al., Citation2022) in children. Household damp and mould can even be fatal: in the United Kingdom, an inquest into the tragic death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak concluded that the toddler died from a respiratory condition caused by exposure to mould in the home (BBC News, Citation2023). Overall, damp and mould impose a large disease burden in terms of hospitalisations and deaths – greater than other household factors such as crowding and cold housing (Riggs et al., Citation2021).

However, while the physical health effects of mould in the home have been well-documented, less is known about the psychological health effects. Housing improvement interventions (including central heating installation, reroofing, replacement windows, thermal insulation, draught-proofing and re-wiring) have been shown to have moderately strong positive effects on adult mental health (Liddell & Guiney, Citation2015). Receipt of fabric works in particular (i.e. structural repair which would affect damp and mould) is associated with higher likelihood of recovery from mental health problems (Curl & Kearns, Citation2015). It seems intuitive to hypothesise that if interventions improving housing problems such as damp and mould positively affect mental health, then the presence of damp and mould may have negative mental health effects. While many studies have examined the mental health effects of ‘housing problems’ – including damp and mould along with other problems such as noise, cold, and poor state of repair as one combined variable (e.g. Macintyre et al., Citation2003) – less is known about household damp/mould as independent predictors of mental health and wellbeing. Anecdotal reports suggest that having mould at home can cause feelings of shame (Webster, Citation2015) and it is possible that the sight or smell of mould in a place where people are supposed to feel particularly safe and secure might lead to feelings of anxiety, disgust, or lack of control. This review therefore aimed to explore the psychological impact of living in a home with damp and/or mould. The review was designed to be a scoping review, broad in nature to identify a wide range of literature and examine a) the extent of literature exploring direct and indirect psychological effects of damp/mould exposure and b) gaps in current research.

Method

This scoping review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) review framework, consisting of five stages: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data and collating, summarising and reporting results. Within this framework we also incorporated the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Identifying the research question

Given that this research was designed to be a scoping review, exploring potential wellbeing effects of household damp and mould which have not yet been systematically reviewed, our research question was broad: What might be the psychological effects of living in a home with damp and/or mould? To answer this question, we were interested in:

Studies reporting on the prevalence of mental health problems, psychological problems and poor wellbeing in individuals exposed to damp/mould in the home (ideally with a comparison group of non-exposed individuals, but studies without comparison groups were also considered to be relevant)

Studies with multivariate analyses, considering whether damp and mould were independently associated with psychological outcomes

Qualitative research where participants might discuss their own perceptions of how damp/mould exposure affected their lives and wellbeing.

It is important to note here that the exposure we were interested in was the presence of either damp, visible mould, odour of mould, mildew, or condensation in the household. Outcomes we were interested in were mental health disorders (such as depression) as well as psychological outcomes such as impacts on mood, emotions, distress and wellbeing. Although it is possible that mould toxins could affect mental health through altering biochemical brain pathways (Shenassa et al., Citation2007) it is important to emphasise that in this review we were interested in only the psychological aspects of mental health.

Identifying relevant studies

To identify studies relevant to the research question, we developed three search strategies. Search 1 included terms relating to psychological outcomes (e.g. “mental health”, wellbeing, depression) which were all combined using the Boolean operator “OR”. Search 2 included terms relating to mould or damp (e.g. mould, mold, damp) which were combined using the “OR” operator. Search 3 included terms relating to the home (e.g. housing, home) which again were combined using “OR”. The three searches were then combined using the Boolean operator “AND”. Although the British English spelling “mould” has been used throughout the manuscript we acknowledge the American English spelling “mold”, and both were accounted for in the search strategy. The full list of search terms is presented in Appendix 1.

The following databases were searched on December 2nd 2022: Embase, PsycInfo, Medline, Web of Science, Global Health, and Health Management Information Consortium. Google Scholar and the preprint server medRxiv were hand-searched, assessing the relevance of (up to) the first 50 results for a number of different keyword searches (see Appendix 2). The reference lists of all included papers were also hand-searched for citations which may not have been picked up by our searches.

Study selection

We developed the following inclusion criteria for study selection:

Written in English (the language spoken by the authors)

Must contain primary data (i.e., not literature reviews)

Journal articles, letters, government reports, preprints, and conference abstracts were all acceptable formats (providing other criteria were met)

Must explore, either quantitatively or qualitatively, the psychological effects of damp/mould exposure

Participants needed to have been exposed to mould in the home (not in the workplace or elsewhere)

If not all participants had experienced damp/mould, then data on mould/damp-exposed participants needed to be clearly separate from data on non-mould exposed participants

Damp/mould needed to be a separate variable rather than combined with other housing problems

Population of the study needed to be larger than one (i.e., no case studies)

Damp/mould should not be the result of flooding; studies examining the psychological impact of having damp/mould in the home as a result of being flooded were excluded as it would be difficult to disentangle the psychological effects of mould and the psychological effects of experiencing a disaster.

There were no limits relating to publication year, study location, or demographic characteristics of participants.

Initial screening was carried out independently by the first author. The second author double-screened approximately 10% of citations and there was 100% agreement between the authors as to which of these citations should be included.

Charting the data

Key data from each included paper were extracted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet with the following headings: authors, year of publication, country, design of study, number of participants, socio-demographic characteristics of participants, how the presence of damp/mould was assessed, wellbeing outcomes assessed, measures used to assess outcomes, conclusions, and limitations. Data were extracted from a subset of approximately 10% of papers by the second author and were found to be in agreement with the first author’s extraction.

Collating, summarising and reporting results

First, in order to establish the frequency and nature of relationships between damp/mould and psychological outcomes, all quantitative studies containing data on the prevalence of psychological problems were grouped together. For each study, we noted whether the data indicated no psychological impact of damp/mould or whether there was significant evidence of psychological impact in univariate analysis, and additionally whether this remained significant in multivariate analysis. Given that the studies were disparate in terms of the outcomes assessed and the measures used, it was difficult to directly compare them; no meta-analysis could be performed and so the results are presented narratively, listing the studies which found significant negative psychological impact. Extracted qualitative data were synthesised using insights from thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), with data coded and grouped together by code – for example, all data relating to negative emotions caused by damp/mould were grouped together and coded as ‘impact’, and all data relating to reasons why damp/mould caused negative emotions were grouped together and coded as ‘explanations for impact’. These are discussed narratively within the sub-section ‘qualitative findings’.

Results

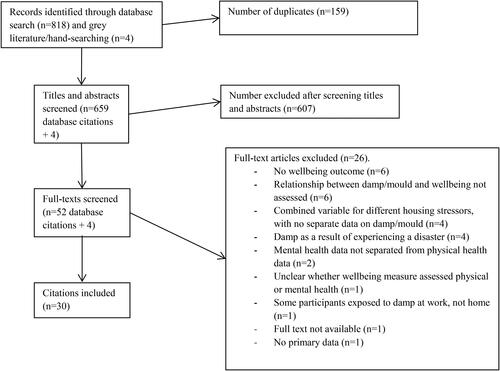

Database searches yielded 818 citations. These were imported into EndNote reference management software, where 159 duplicate citations were removed. Titles and abstracts of the remaining 659 citations were screened, with 531 being excluded based on title and 76 excluded based on abstract. We then searched for full texts of the remaining 52 studies. One full-text was not available and 25 were excluded after reading the full paper. This left 26 studies for inclusion in the review. One report was added after searching grey literature and three studies added after hand-searching. Overall, 30 studies were included. A flow diagram of the screening process can be seen in .

The included studies were based in a number of countries: United Kingdom (n = 14), United States of America (n = 4), New Zealand (n = 3), Australia (n = 2), and Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Guyana and Sweden (n = 1 each). A further two studies included multiple countries in Europe. Study populations ranged from 6 – 42,723.

Supplementary File 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of each of the included studies. shows whether significant associations were found between mould/damp and psychological outcomes, in both univariate analyses and multivariate analyses.

Table 1. Univariate and multivariate associations between damp/mould and psychological outcomes.

Univariate associations between household mould/damp and psychological wellbeing

Significant findings

Twenty-four of the included studies carried out statistical tests assessing the relationship between damp/mould and psychological outcomes and 21 of these (87.5%) found significant associations. Univariate analyses found significant associations between mould/damp in the home and stress (Packer et al., Citation1994); psychological distress (Hopton & Hunt, Citation1996; Paterson et al., Citation2018); anxiety (Packer et al., Citation1994); depression (Bower et al., Citation2021; Hyndman, Citation1990; Packer et al., Citation1994; Shenassa et al., Citation2007; World Health Organization, Citation2007); postnatal depression (Butler et al., Citation2003); affective disorders (Groot et al., Citation2022); dissatisfaction with life (Boomsma et al., Citation2017); loneliness (Bower et al., Citation2021); low vitality (Guite et al., Citation2006); reduced vigour (Kilburn, Citation2003); poor sleep (Karunanayake et al., Citation2021); ‘nerves’ (Platt et al., Citation1989); poor wellbeing (Boomsma et al., Citation2017; World Health Organization, Citation2007); and poor general mental health (Guite et al., Citation2006; Kilburn, Citation2003; Wen & Balluz, Citation2011).

Univariate analyses focusing on children found significant associations between household mould/damp and conduct problems (Baird et al., Citation2022; Midouhas et al., Citation2019); emotional symptoms (Casas et al., Citation2013; Martin et al., Citation1987; Midouhas et al., Citation2019); ‘nerves’ (Martin et al., Citation1987); irritability (Platt et al., Citation1989); feeling depressed/unhappy (Platt et al., Citation1989); mental health (Nasim, Citation2022); and ‘total difficulties’ (combination of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention and peer relationship problems) (Casas et al., Citation2013).

Non-significant findings

In a minority of studies (n = 3), univariate analyses revealed no significant associations between household mould/damp and any of the psychological outcomes examined, including psychological distress (Blackman et al., Citation2001); stress (Kang et al., Citation2022; Oudin et al., Citation2016); fatigue (Oudin et al., Citation2016); concentration difficulties (Oudin et al., Citation2016); sleep problems (Oudin et al., Citation2016); and overall mental health (Kang et al., Citation2022).

A further three studies which found univariate associations between household damp/mould and some psychological outcomes also found non-significant results for other outcomes. A study which had found a significant association between damp/mould and ‘nerves’ (Platt et al., Citation1989) found no significant association between damp/mould and feeling depressed/down-hearted. Bower et al. (Citation2021) found no significant association between damp/mould and anxiety, although they did find that damp/mould were significantly associated with both depression and loneliness. Additionally, Casas et al. (Citation2013) found no significant relationship between household damp/mould and conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention or peer relationship problems, although they did find significant relationships with emotional symptoms and total difficulties.

Multivariate associations between household mould/damp and psychological wellbeing

Significant findings

In 13/17 (76.5%) studies, associations between household mould/damp and psychological outcomes remained significant after adjusting for confounding variables (see ). Mould and damp remained associated with anxiety (World Health Organization, Citation2007); depression (Hyndman, Citation1990; Shenassa et al., Citation2007; World Health Organization, Citation2007); postnatal depression (Butler et al., Citation2003); loneliness (Bower et al., Citation2021); sleep problems (Karunanayake et al., Citation2021); ‘bad nerves’ (Platt et al., Citation1989); overall mental health or wellbeing (Wen & Balluz, Citation2011; World Health Organization, Citation2007); psychological distress (Hopton & Hunt, Citation1996); and children’s conduct problems (Baird et al., Citation2022), emotional problems (Casas et al., Citation2013), mental health (Nasim, Citation2022) and ‘bad nerves’ (Martin et al., Citation1987). Covariates included in the multivariate regressions can be seen in .

Shenassa et al. (Citation2007) found that perception of control over one’s home attenuated the association between mould and depression, and inclusion of physical health problems in the regression model (particularly chronic respiratory problems) also attenuated the association. However, these two mediators still did not account for the entire association between mould and depression, which remained significant.

Loss of significance

In six studies which found significant associations between household mould/damp and psychological outcomes, significance of at least one of these relationships was lost after adjusting for confounding variables. These studies showed a loss of association between mould/damp and depression (Bower et al., Citation2021; Packer et al., Citation1994); anxiety/stress (Packer et al., Citation1994); distress (Paterson et al., Citation2018); overall wellbeing (Boomsma et al., Citation2017); general mental health (Guite et al., Citation2006); and irritability and feelings of depression/unhappiness in children (Platt et al., Citation1989).

Confounding variables included in regression models which no longer showed mould/damp as significant predictors included demographics such as age, gender, ethnicity, and social class (Bower et al., Citation2021; Guite et al., Citation2006; Packer et al., Citation1994; Paterson et al., Citation2018); marital status (Paterson et al., Citation2018); education (Paterson et al., Citation2018); employment status (Paterson et al., Citation2018); having nobody in the household employed (Platt et al., Citation1989); overcrowding (Platt et al., Citation1989); housing affordability concerns (Boomsma et al., Citation2017); perceived neighbourhood belonging (Bower et al., Citation2021); and living with smokers (Platt et al., Citation1989).

In these studies, housing factors which did emerge as predictors of psychological outcomes in multivariate analyses included poor condition of the home (Paterson et al., Citation2018) and presence of pests in the home (Paterson et al., Citation2018).

One study (Karunanayake et al., Citation2021) found that while exposure to visible mould remained a significant predictor of poor sleep after adjusting for confounding variables, dampness alone and a mouldy smell alone lost significance.

Other quantitative findings

One study compared mental health outcomes in mould-exposed populations compared to populations with other conditions: Kilburn (Citation2009) found that mood states (a variable consisting of the sum of five adverse moods) for a mould exposure group were slightly lower than for a chemical exposure group, but nearly twice the group exposed to neither.

One study did not statistically assess the relationship between damp/mould exposure and psychological outcomes, but instead asked participants whether they believed that exposure had affected the mental health of people in their household. Shortt & Rugkåsa (Citation2007) asked participants their perceptions on whether condensation, damp or mould had any impact on the mental health of people in their household and found that very few respondents felt that they had any impact. It is unclear from this study whether this was indeed the case or whether there were, in fact, any impacts and these were simply not recognised.

Qualitative findings

Six studies included qualitative data relating to participants’ experiences of damp/mould in their homes, all of which focused on tenants and those in social housing provided by housing associations or councils, rather than owner-occupiers. Participants described a number of negative wellbeing effects of having household damp/mould, including fear of the potential health hazards (Blay et al., Citation2019; Boomsma et al., Citation2017; Butler & Sherriff, Citation2017); unhappiness (Blay et al., Citation2019; Ziersch et al., Citation2017); depressive symptoms (Ziersch et al., Citation2017); anger (Blay et al., Citation2019; Ziersch et al., Citation2017); distress (Butler & Sherriff, Citation2017); discomfort (Blay et al., Citation2019); frustration (Boomsma et al., Citation2017; Butler & Sherriff, Citation2017); and feeling ‘on edge’ (Blay et al., Citation2019), all of which participants attributed to the sight, smell and knowledge of health implications of mould and damp. Sadness, anger and depressive symptoms appeared to be particularly pronounced for asylum seekers who felt a greater lack of control than those with permanent resident status over housing issues (Ziersch et al., Citation2017).

Damp and mould were described as ‘a nuisance’ (Blay et al., Citation2019) and ‘depressing’ (Boomsma et al., Citation2017), with participants fed up with having to frequently paint over mould and damp (Boomsma et al., Citation2017), living with an unpleasant smell (Butler & Sherriff, Citation2017; Serjeant et al., Citation2022) and having clothes ruined by mildew and mould (Serjeant et al., Citation2022). Participants reported feeling self-conscious that the smell of mould would linger and others would smell damp on their clothes when out in public or welcoming visitors to their homes (Butler & Sherriff, Citation2017); the smell was seen as not only a threat to home comfort but to participants’ identities as capable and independent adults. Participants in three studies reported having had their physical health or that of their families negatively affected by damp and mould (Boomsma et al., Citation2017; Butler & Sherriff, Citation2017; Ziersch et al., Citation2017). Some reported increased arguments with other occupants in their homes due to others’ lack of understanding of the negative impact of dampness and tensions around the increase in energy bills as a result of opening windows and using heating (Blay et al., Citation2019).

Participants in all qualitative studies wanted to reduce damp and mould in their homes, wanting a more ‘healthy’ living environment (Blay et al., Citation2019), and although most understood how they could reduce damp and mould (e.g. through aeration or dehumidifiers) many avoided or limited the duration of these behaviours due to consciousness of energy bills and fear of cold (Blay et al., Citation2019; Serjeant et al., Citation2022).

Tenant-landlord relationships could be strained, which meant that attempts to resolve issues relating to damp and mould tended to be unsuccessful (Butler & Sherriff, Citation2017); participants with landlords responsive to damp issues reported feeling lucky (Serjeant et al., Citation2022). Others were less lucky, describing how landlords made unrealistic and unhelpful suggestions such as keeping the heating on low all the time, which they could not afford to do (Butler & Sherriff, Citation2017).

Finally, Seppala et al. (Citation2022)’s participants described how their experiences with poor indoor air quality were ‘delegitimised’, reporting how doctors would not testify that their illnesses were caused by mould and that authorities claimed that there was nothing wrong with their apartments despite evidence of mould, so they could not be given new accommodation. These experiences were perceived to be unfair and associated with anger and bitterness.

Discussion

This scoping review of 30 studies found that the majority of quantitative studies (87.5%) showed a univariate association between household damp/mould and a range of psychological outcomes, including stress, depression, anxiety, and poor overall mental health and wellbeing. Of the studies which carried out multivariate analyses, 76.5% found that household damp/mould remained a significant independent predictor of mental health outcomes even when controlling for multiple other variables including socioeconomic status, house ownership status, employment and chronic illness. Additionally, qualitative data from six studies revealed that participants believed household damp and mould affected their wellbeing, citing negative feelings elicited by the sight and smell of mould; fear of potential physical health consequences; and embarrassment about clothes and homes smelling damp. While the relationships between household damp/mould and mental health and wellbeing are not universal, and there are caveats – which we discuss below – this review provides the first evidence of a substantial association between damp/mould and mental health/wellbeing.

People exposed to damp/mould may be more prone to physical health issues, which can further impact mental health: the link between physical health and mental health is well-established (Ohrnberger et al., Citation2017). Also, it may be the physical health effects – or fear of physical health effects – associated with damp and mould which impact on psychological wellbeing. Indeed, the qualitative data we reviewed found that fear of physical health consequences was a prominent theme in 3/6 studies. It would be worthwhile to investigate the extent to which this fear may be fuelled by media coverage. Some participants in the qualitative data felt that healthcare staff had not supported the idea that their physical health had been damaged; while we cannot ascertain the extent to which damp and mould may truly have affected physical health, it is possible that fear-inducing messages in the media may influence participants (Maran & Begotti, Citation2021).

We also highlight Shenassa et al.’s (Citation2007) important finding that perception of control over one’s home attenuated the association between mould and depression. Notably, in this study approximately one-quarter of participants rented properties and the rest owned their homes. It is likely that renting is associated with perceived lack of control due to the precarity of living in rented accommodation, which has been exacerbated after the COVID-19 pandemic (Newton et al., Citation2022; Waldron, Citation2023). Only one other study in this review (Guite et al., Citation2006) included home ownership status in a regression model, finding that the relationship between damp/mould and psychological wellbeing lost significance in a multivariate model which included home ownership status.

Despite the finding that household damp/mould remained an independent predictor of mental health in 76.5% of studies with multivariate analyses, it remains difficult to fully disentangle the effects of damp and mould. Many of the studies reviewed are cross-sectional, making it difficult to clearly understand the directionality of relationships – we can only note associations, rather than causation. Researchers have urged caution when interpreting findings showing a link between mould and depression (Potera, Citation2007), suggesting it is not possible to infer a causal relationship between the two and proposing that income may be an important confounding variable. Those with damp/mould might also be more likely to have difficulty paying fuel bills – financial difficulties are associated with poor mental health (Knifton & Inglis, Citation2020) and it is difficult to disentangle how much wellbeing is affected specifically by damp/mould in the home and how much it is affected by the myriad other problems that might be caused by poverty. Our review found that the relationship between damp/mould and psychological wellbeing persisted after adjusting for socioeconomic status in four studies (Baird et al., Citation2022; Hopton & Hunt, Citation1996; Platt et al., Citation1989; WHO, Citation2007) whereas the relationship lost significance after adjusting for socioeconomic status in three studies (Boomsma et al., Citation2017; Bower et al., Citation2021; Packer et al., Citation1994). There could be other confounders such as education: higher education equips individuals with good communication skills (Iksan et al., Citation2012), therefore individuals with higher levels of education might find it easier to address problems of damp/mould through legal means or discussions with housing associations or landlords. Our review provided mixed findings on this: the relationship between damp/mould and psychological wellbeing persisted after adjusting for education in two studies (Butler et al., Citation2003; Wen & Balluz, Citation2011) and after adjusting for parental education in one study of children (Casas et al., Citation2013). However, in two studies (Bower et al., Citation2021; Paterson et al., Citation2018) the relationship lost significance after including education in the model. Within the literature, insufficient attention has been given to the conditions underlying inequities in the distribution of toxic exposures in the home; toxic exposures do not occur in isolation and the unfavourable social conditions associated with damp and mould are also likely to generate other environmental hazards which accumulate over time (Rauh et al., Citation2008). However, our review found that in a number of studies (Baird et al., Citation2022; Butler et al., Citation2003; Shenassa et al., Citation2007; WHO, Citation2007), the relationship between damp/mould and psychological wellbeing persisted after including other housing quality issues (including high spatial density, cold, crowding, access to green areas, dust, and lighting) in regression models. It also cannot be discounted that mould and other toxins may impact mental health directly through potential effects of toxic exposure on brain chemistry.

Given the methodological limitations of the reported papers, and some inconsistencies in their findings, it is not possible to draw a firm conclusion concerning the link between household damp/mould and mental health/wellbeing based on these findings. Although the lack of prospective research and potential confounding variables make it difficult to establish causation, this review is a useful first step in ascertaining whether damp/mould might play a role in psychological wellbeing, and the studies reviewed suggest that this is indeed the case. The effect persisting in many studies even when covariates are controlled for strengthens the argument for the role of damp/mould in wellbeing.

Overall, while this review could not provide clear evidence of a causal relationship between damp/mould and psychological wellbeing – because the reliance on cross-sectional research does not allow for this – we did find relatively consistent evidence suggesting an association between damp/mould and psychological health. This suggests that the topic is worthy of further investigation and that whatever the cause, it appears that people living in mouldy homes are at increased risk of reporting mental health problems. More carefully constructed studies are needed to be able to properly answer the question of how much direct impact exposure to household damp and mould may have on psychological wellbeing.

The topic is of clear public health importance and may be a proxy for poor housing issues as well as important in itself. If indeed mental health is negatively affected by poor housing such as damp and mould, it may be the case that the costs of treating poor mental health (as well as loss of tax revenue from people with poor mental health who are unable to work, and potentially intergenerational costs from children suffering the effects of poor housing) could be offset by investing in better housing options in the built environment. This review also highlights the importance of making healthcare professionals aware of damp and mould as potential risk factors for poor psychological wellbeing. Finally, our findings also contribute to the broader argument for improving standards of living in general. Instead of taking a laissez-faire approach to mould in homes, treatment of damp and mould should be prioritised as treatment is a relatively low-cost intervention and could improve wellbeing and mental health if implemented. Better guidance or support on removing household mould could be a relatively quick and easy intervention to implement – for example, national campaigns offering practical advice on reducing damp, condensation and mould as well as health information (Boomsma et al., Citation2017).

It is important that housing is recognised as a social determinant of health and that housing disparities are considered in future research. We suggest that an intersectional perspective is essential for understanding how oppression or privilege of certain groups can impact on housing and health (Vásquez-Vera et al., Citation2022). Research focusing on marginalised populations, health researchers joining housing justice movements to prioritise intersectionality, and involving people with lived experience of housing disparities in the design of research studies would all help to ensure an intersectional perspective is achieved (Leifheit et al., Citation2022).

Limitations of the current review include the decision to limit the review only to articles published in English and the fact that no systematic appraisal of the quality of included studies was performed. While quality appraisal is not a compulsory aspect of a scoping review, we acknowledge that using a standardised quality appraisal or risk of bias tool to evaluate each study would have been beneficial in order to assess the trustworthiness and value of the included studies. We also acknowledge that, while there was agreement regarding the data extraction of the 10% of studies the second author independently carried out, our review would have been more robust had the second author independently extracted data from all studies. Nevertheless, the findings offer valuable evidence of a potential relationship between mental health/psychological wellbeing and household damp and mould, linking to growing interest in the relationships between social (psychological) resilience, the built environment and urban health. This evidence provides a foundation for future research to build upon.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this scoping review reveals consistent evidence of an association between household dampness/mould and various psychological outcomes. The majority of quantitative studies support this link, with more than three quarters of the studies showing a significant association. However, determining the direct impact of dampness/mould on psychological wellbeing is challenging due to confounding factors and the inability to establish causality. Considering the broader context of social resilience, urban health, and the built environment literature, the role of mould in understanding mental health and wellbeing should not be overlooked. The potential accumulation of environmental hazards in homes with dampness and mould, in addition to the interplay with other housing quality issues, further complicates the assessment of the specific impact of dampness/mould alone. Furthermore, the fear of physical health consequences associated with mould, and media coverage on this topic, may influence individuals’ perceptions and mental health outcomes. Further research is needed to disentangle the specific effects of dampness/mould from other interconnected factors and to inform interventions and policies aimed at improving housing standards and addressing potential public health implications. In particular, more prospective/longitudinal research is needed to explicitly try to establish a causal relationship between damp/mould and wellbeing. Despite limitations such as language restrictions and the absence of systematic quality appraisal, this review provides a valuable foundation for future research. It underscores the significance of considering household dampness/mould in the context of social resilience, urban health, and the built environment. This topic warrants further investigation to better understand the relationship, develop effective interventions, and inform housing and public health policies.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (100.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (4.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Samantha K. Brooks

Samantha K. Brooks is a research fellow at King’s College London and has a PhD in Social Psychology. Her research focuses on mental health and psychological wellbeing in those affected by extreme events, disasters, emergencies and public health crises. In particular, her research explores psychological resilience and how best to support those affected by potentially traumatic events. During the COVID-19 pandemic she published a number of papers on the psychological impact of quarantine and lockdown; how to support various potentially vulnerable groups during a public health crisis; and how organisations can support staff working from home during a crisis.

Sonny S. Patel

Sonny S. Patel is an award-winning researcher and former National Institutes of Health Fogarty Global Health Scholar. He is a Presidential Fellow in Transcultural Conflict and Violence Initiative at Georgia State University and a Visiting Scientist at Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. He has developed protocols, programs, and training to build capacity and knowledge in communities worldwide from subject matters in Public Health, Community Health, and Mental Health. Patel was named a top 40 under 40 Public Health Catalyst by the Boston Congress of Public Health, and he was picked by LinkedIn as 1 of 120 experts in 2022 for U.S. program on Technology and Innovation. He was also bestowed as Top Voice on LinkedIn and won the Emerald Publishing Literati Award in 2021 for Outstanding Research Paper by the Journal of Disaster Prevention and Management. He is the author of the book, Community Resilience When Disaster Strikes: Security and Community Health in UK Flood Zones, published by Springer Nature, and contributed to the Emerald Publishing book, COVID-19, Frontline Responders and Mental Health: A Playbook for Delivering Resilient Public Health Systems Post-Pandemic, and the Routledge published textbook, Service-Learning for Disaster Resilience: Partnerships for Social Good.

Dale Weston

Dale Weston is a Principal Behavioural Scientist in the UKHSA Behavioural Science and Insights Unit. He is co-lead of research themes within the Health Protection Research Units for Emergency Preparedness and Response (at Kings’ College London), and Modelling and Health Economics (at Imperial College London). Dale has led extensive research, both national and international, in the fields of social and health psychology as applied to health protection, health security, and public health emergency preparedness and response.

Neil Greenberg

Neil Greenberg is a consultant academic, occupational and forensic psychiatrist based at King’s College London. Neil served in the United Kingdom Armed Forces for more than 23 years and has deployed, as a psychiatrist and researcher, to a number of hostile environments including Afghanistan and Iraq. At King’s Neil leads on a number of military mental health projects and is a principal investigator within a nationally funded Health Protection Research unit. He is a past chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP) Special Interest Group in Occupational Psychiatry and led the World Psychiatric Association position statement on mental health in the workplace. Neil has published more than 350 scientific papers and book chapters and has been the Secretary of the European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, the President of the UK Psychological Trauma Society and Specialist Advisor to the House of Commons Defence Select Committee. During the COVID19 pandemic, Neil worked closely with various government organisations and published widely on psychological support for healthcare, and other key workers. As well as running March on Stress Ltd, a psychological health consultancy, Neil is a trustee with the Society and Faculty of Occupational Medicine.

References

- Adamkiewicz, G., Spengler, J. D., Harley, A. E., Stoddard, A., Yang, M., Alvarez-Reeves, M. & Sorensen, G. (2014) Environmental conditions in low-income urban housing: Clustering and associations with self-reported health, American Journal of Public Health, 104, pp. 1650–1656.

- Anderson, N. (2022) Britain’s ‘mould epidemic’ made worse by cost-of-living crisis: How 4.7million private renters have battled fungus in their homes over the past year as hard-pressed tenants cut back on heating. Available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11456351/Britains-mould-epidemic-worse-cost-living-crisis.html (accessed 4 June 2023).

- Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, pp. 19–32.

- Baird, A., Papachristou, E., Hassiotis, A. & Flouri, E. (2022) The role of physical environmental characteristics and intellectual disability in conduct problem trajectories across childhood: a population-based cohort study, Environmental Research, 209, pp. 112837.

- BBC News (2023) Awaab Ishak: Guidance on mould to be reviewed after toddler’s death. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-64273057 (accessed 30 October 2023).

- Blackman, T., Harvey, J., Lawrence, M. & Simon, A. (2001) Neighbourhood renewal and health: evidence from a local case study, Health & Place, 7, pp. 93–103.

- Blay, K., Agyekum, K. & Opoku, A. (2019) Actions, attitudes and beliefs of occupants in managing dampness in buildings, International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 37, pp. 42–53.

- Bonnefoy, X. (2007) Inadequate housing and health: an overview, International Journal of Environment and Pollution, 30, pp. 411–429.

- Boomsma, C., Pahl, S., Jones, R. V. & Fuertes, A. (2017) Damp in bathroom. Damp in back room. It’s very depressing!" exploring the relationship between perceived housing problems, energy affordability concerns, and health and well-being in UK social housing, Energy Policy, 106, pp. 382–393.

- Bower, M., Buckle, C., Rugel, E., Donohoe-Bales, A., McGrath, L., Gournay, K., Barrett, E., Phibbs, P. & Teesson, M. (2021) ‘Trapped’, ‘anxious’ and ‘traumatised’: COVID-19 intensified the impact of housing inequality on australians’ mental health, International Journal of Housing Policy, 23, pp. 260–291.

- Brasche, S. & Bischof, W. (2005) Daily time spent indoors in german homes – baseline data for the assessment of indoor exposure of german occupants, International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 208, pp. 247–253.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, pp. 77–101.

- Butler, D. & Sherriff, G. (2017) It’s normal to have damp’: Using a qualitative psychological approach to analyse the lived experience of energy vulnerability among young adult households, Indoor and Built Environment, 26, pp. 964–979.

- Butler, S., Williams, M., Tukuitonga, C. & Paterson, J. (2003) Problems with damp and cold housing among pacific families in New Zealand, The New Zealand Medical Journal, 116, pp. U494.

- Casas, L., Tiesler, C., Thiering, E., Brüske, I., Koletzko, S., Bauer, C.-P., Wichmann, H.-E., von Berg, A., Berdel, D., Krämer, U., Schaaf, B., Lehmann, I., Herbarth, O., Sunyer, J., Heinrich, J. & GINIplus and LISAplus Study Group (2013) Indoor factors and behavioural problems in children: the GINIplus and LISAplus birth cohort studies, International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 216, pp. 146–154.

- Coulburn, L. & Miller, W. (2022) Prevalence, risk factors and impacts related to mould-affected housing: an Australian integrative review, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, pp. 1854.

- Curl, A. & Kearns, A. (2015) Can housing improvements cure or prevent the onset of health conditions over time in deprived areas?, BMC Public Health, 15, pp. 1191.

- Dewilde, C. (2022) How housing affects the association between low income and living conditions – deprivation across Europe, Socio-Economic Review, 20, pp. 373–400.

- Du, C., Li, B., Yu, W., Yao, R., Cai, J., Li, B., Yao, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, M. & Essah, E. (2022) Characteristics of annual mold variations and association with childhood allergic symptoms/diseases via combining surveys and home visit measurements, Indoor Air, 32, pp. e13113.

- Ellaway, A. & Macintyre, S. (1998) Does housing tenure predict health in the UK because it exposes people to different levels of housing related hazards in the home or its surroundings?, Health & Place, 4, pp. 141–150.

- Groot, J., Keller, A., Pedersen, M., Sigsgaard, T., Loft, S. & Nybo Andersen, A. M. (2022) Indoor home environments of danish children and the socioeconomic position and health of their parents: a descriptive study, Environment International, 160, pp. 107059.

- Guite, H. F., Clark, C. & Ackrill, G. (2006) The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being, Public Health, 120, pp. 1117–1126.

- Hayles, C. S., Huddleston, M., Chinowsky, P. & Helman, J. (2022) Summertime impacts of climate change on dwellings in Wales, UK, Building and Environment, 219, pp. 109185.

- Hopton, J. L. & Hunt, S. M. (1996) Housing conditions and mental health in a disadvantaged area in Scotland, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 50, pp. 56–61.

- Hyndman, S. J. (1990) Housing dampness and health amongst british bengalis in east london, Social Science & Medicine (1982), 30, pp. 131–141.

- Iksan, Z. H., Zakaria, E., Meerah, T. S. M., Osman, K., Lian, D. K. C., Mahmud, S. N. D. & Krish, P. (2012) Communication skills among university students, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 59, pp. 71–76.

- Indoor Air Quality Scientific Findings Resource Bank: Berkeley Lab (2023) Prevalence of building dampness. Available at. https://iaqscience.lbl.gov/prevalence-building-dampness [accessed 22 May 2023]

- Jedrychowski, W., Maugeri, U., Perera, F., Stigter, L., Jankowski, J., Butscher, M., Mroz, E., Flak, E., Skarupa, A. & Sowa, A. (2011) Cognitive function of 6-year old children exposed to mold-contaminated homes in early postnatal period. Prospective birth cohort study in Poland, Physiology & Behavior, 104, pp. 989–995.

- Kang, I., McCreery, A., Azimi, P., Gramigna, A., Baca, G., Hayes, W., Crowder, T., Scheu, R., Evens, A. & Stephens, B. (2022) Impacts of residential indoor air quality and environmental risk factors on adult asthma-related health outcomes in chicago, IL, Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 33, pp. 358–367.

- Karunanayake, C. P., Fenton, M., Skomro, R., Ramsden, V. R., Kirychuk, S., Rennie, D. C., Seeseequasis, J., Bird, C., McMullin, K., Russell, B. P., Koehncke, N., Smith-Windsor, T., King, M., Abonyi, S., Pahwa, P. & Dosman, J. A. (2021) Sleep deprivation in two Saskatchewan first nation communities: a public health consideration, Sleep Medicine: X, 3, pp. 100037.

- Kearns, A., Hiscock, R., Ellaway, A. & Macintyre, S. (2000) ‘Beyond four walls’. The psycho-social benefits of home: Evidence from west Central Scotland, Housing Studies, 15, pp. 387–410.

- Kilburn, K. H. (2003) Indoor mold exposure associated with neurobehavioral and pulmonary impairment: a preliminary report, Archives of Environmental Health, 58, pp. 390–398.

- Kilburn, K. H. (2009) Neurobehavioral and pulmonary impairment in 105 adults with indoor exposure to molds compared to 100 exposed to chemicals, Toxicology and Industrial Health, 25, pp. 681–692.

- King, S. (2021) Why are people of colour disproportionately impacted by the housing crisis? Available at https://blog.shelter.org.uk/2021/02/why-are-people-of-colour-disproportionately-impacted-by-the-housing-crisis/ (accessed 30 October 2023)

- Knifton, L. & Inglis, G. (2020) Poverty and mental health: policy, practice and research implications, BJPsych Bulletin, 44, pp. 193–196.

- Krieger, J. & Higgins, D. K. (2002) Housing and health: Time again for public health action, American Journal of Public Health, 92, pp. 758–768.

- Leech, J. A., Nelson, W. C., Burnett, R. T., Aaron, S. & Raizenne, M. E. (2002) It’s about time: a comparison of Canadian and American time-activity patterns, Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology, 12, pp. 427–432.

- Leifheit, K. M., Schwartz, G. L., Pollack, C. E. & Linton, S. L. (2022) Building health equity through housing policies: critical reflections and future directions for research, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 76, pp. 759–763.

- Liddell, C. & Guiney, C. (2015) Living in a cold and damp home: frameworks for understanding impacts on mental well-being, Public Health, 129, pp. 191–199.

- Macintyre, S., Ellaway, A., Hiscock, R., Kearns, A., Der, G. & McKay, L. (2003) What features of the home and the area might help to explain observed relationships between housing tenure and health? Evidence from the west of Scotland, Health & Place, 9, pp. 207–218.

- Maran, D. A. & Begotti, T. (2021) Media exposure to climate change, anxiety, and efficacy beliefs in a sample of italian university students, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, pp. 9358.

- Martin, C. J., Platt, S. D. & Hunt, S. M. (1987) Housing conditions and ill health, British Medical Journal (Clinical Research ed.), 294, pp. 1125–1127.

- Mathieu, E., Ritchie, H., Rodés-Guirao, L., Appel, C., Gavrilov, D., Giattino, C., (…) Roser, M. (2020) COVID-19: Stay-at-home restrictions. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Available at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-stay-home-restrictions [accessed 21 May 2023]

- Midouhas, E., Kokosi, T. & Flouri, E. (2019) The quality of air outside and inside the home: associations with emotional and behavioural problem scores in early childhood, BMC Public Health, 19, pp. 406.

- Moses, L., Morrissey, K., Sharpe, R. A. & Taylor, T. (2019) Exposure to indoor mouldy odour increases the risk of asthma in older adults living in social housing, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, pp. 2600.

- Nasim, B. (2022) Does poor quality housing impact on child health? Evidence from the social housing sector in avon, UK, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 82, pp. 101811.

- Newton, D., Lucock, M., Armitage, R., Monchuk, L. & Brown, P. (2022) Understanding the mental health impacts of poor quality private-rented housing during the UK’s first COVID-19 lockdown, Health & Place, 78, pp. 102898.

- Novoa, A. M., Bosch, J., Diaz, F., Malmusi, D., Darnell, M. & Trilla, C. (2014) Impact of the crisis on the relationship between housing and health. Policies for good practice to reduce inequalities in health related to housing conditions, Gaceta Sanitaria, 28 Suppl 1, pp. 44–50.

- Office for National Statistics (2022) Is hybrid working here to stay? Available at. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/ishybridworkingheretostay/2022-05-23 (accessed 5 July 2023)

- Ohrnberger, J., Fichera, E. & Sutton, M. (2017) The relationship between physical and mental health: a mediation analysis, Social Science & Medicine (1982), 195, pp. 42–49.

- Oudin, A., Richter, J. C., Taj, T., Al-Nahar, L. & Jakobsson, K. (2016) Poor housing conditions in association with child health in a disadvantaged immigrant population: a cross-sectional study in rosengard, malmo, Sweden, BMJ Open, 6, pp. e007979.

- Packer, C. N., Stewart-Brown, S. & Fowle, S. E. (1994) Damp housing and adult health: results from a lifestyle study in worcester, England, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 48, pp. 555–559.

- Patel, S. S. (2022) Community resilience when disaster strikes: Security and community health in UK flood zones. Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Paterson, J., Iusitini, L., Tautolo, E. S., Taylor, S. & Clougherty, J. (2018) Pacific islands families (PIF) study: housing and psychological distress among pacific mothers, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42, pp. 140–144.

- Pevalin, D. J., Taylor, M. P. & Todd, J. (2008) The dynamics of unhealthy housing in the UK: a panel data analysis, Housing Studies, 23, pp. 679–695.

- Phillips, A. (2022) Homes under threat from mould outbreaks as heating crisis to create ‘perfect storm’. Express. Available at https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/1680925/property-news-homes-under-threat-mould-outbreaks-cost-of-living-energy-heating [accessed 19 May 2023]

- Platt, S. D., Martin, C. J., Hunt, S. M. & Lewis, C. W. (1989) Damp housing, mold growth, and symptomatic health state, BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 298, pp. 1673–1678.

- Portnoy, J. M., Kwak, K., Dowling, P., VanOsdol, T. & Barnes, C. (2005) Health effects of indoor fungi, Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology: official Publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology, 94, pp. 313–320.

- Potera, C. (2007) Mental health: Molding a link to depression, Environmental Health Perspectives, 115, pp. A536.

- Rashidfarokhi, A. & Danivska, V. (2023) Managing crises ‘together’: how can the built environment contribute to social resilience?, Building Research & Information, 51, pp. 747–763.

- Rauh, V. A., Landrigan, P. J. & Claudio, L. (2008) Housing and health: Intersection of poverty and environmental exposures, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136, pp. 276–288.

- Riggs, L., Keall, M., Howden-Chapman, P. & Baker, M. G. (2021) Environmental burden of disease from unsafe and substandard housing, New Zealand, 2010-2017, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99, pp. 259–270.

- Rolfe, S., Garnham, L., Godwin, J., Anderson, I., Seaman, P. & Donaldson, C. (2020) Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework, BMC Public Health, 20, pp. 1138.

- Seppala, T., Finell, E. & Kaikkonen, S. (2022) Making sense of the delegitimation experiences of people suffering from indoor air problems in their homes, International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 17, pp. 2075533.

- Serjeant, E., Coleman, T. & Kearns, R. (2022) How tenants in New Zealand respond to winter weather indoors: a qualitative investigation, Health & Place, 75, pp. 102810.

- Sharpe, R. A., Thornton, C. R., Nikolaou, V. & Osborne, N. J. (2015) Fuel poverty increases risk of mould contamination, regardless of adult risk perception & ventilation in social housing properties, Environment International, 79, pp. 115–129.

- Shaw, M. (2004) Housing and public health, Annual Review of Public Health, 25, pp. 397–418.

- Shenassa, E. D., Daskalakis, C., Liebhaber, A., Braubach, M. & Brown, M. (2007) Dampness and mold in the home and depression: an examination of mold-related illness and perceived control of one’s home as possible depression pathways, American Journal of Public Health, 97, pp. 1893–1899.

- Shortt, N. & Rugkåsa, J. (2007) The walls were so damp and cold" fuel poverty and ill health in Northern Ireland: Results from a housing intervention, Health & Place, 13, pp. 99–110.

- Tilburg, W. C. (2017) Policy approaches to improving housing and health, The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics: a Journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 45, pp. 90–93.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., Godfrey, C. M., Macdonald, M. T., Langlois, E. V., Soares-Weiser, K., Moriarty, J., Clifford, T., Tunçalp, Ö. & Straus, S. E. (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation, Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, pp. 467–473.

- Tuuminen, T. & Rinne, K. S. (2017) Severe sequelae to Mold-Related illness as demonstrated in two finnish cohorts, Frontiers in Immunology, 8, pp. 382.

- UK Government (2020) Housing with damp problems. Available at https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/housing/housing-conditions/housing-with-damp-problems/latest [accessed 19 May 2023]

- Vardoulakis, S., Dimitroulopoulou, C., Thornes, J., Lai, K.-M., Taylor, J., Myers, I., Heaviside, C., Mavrogianni, A., Shrubsole, C., Chalabi, Z., Davies, M. & Wilkinson, P. (2015) Impact of climate change on the domestic indoor environment and associated health risks in the UK, Environment International, 85, pp. 299–313.

- Vásquez-Vera, C., Fernández, A. & Borrell, C. (2022) Gender-based inequalities in the effects of housing on health: a critical review, SSM - Population Health, 17, pp. 101068.

- Waldron, R. (2023) Experiencing housing precarity in the private rental sector during the covid-19 pandemic: the case of Ireland, Housing Studies, 38, pp. 84–106.

- Webster, P. C. (2015) Housing triggers health problems for canada’s first nations, Lancet (London, England), 385, pp. 495–496.

- Wen, X. J. & Balluz, L. (2011) Association between presence of visible in-house mold and health-related quality of life in adults residing in four U.S. states, Journal of Environmental Health, 73, pp. 8–14.

- World Health Organization (2007). Large analysis and review of European housing and health status (LARES): Preliminary overview. Available at https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/107476/lares_result.pdf [accessed 3 May 2023]

- Ziersch, A., Walsh, M., Due, C. & Duivesteyn, E. (2017) Exploring the relationship between housing and health for refugees and asylum seekers in South Australia: a qualitative study., International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14, pp. 1036.

- Žuškin, E., Schachter, E. N., Mustajbegović, J., Pucarin-Cvetković, J., Doko-Jelinić, J. & Mučić-Pucić, B. (2009) Indoor air pollution and effects on human health, Periodicum Biologorum, 111, pp. 37–40. s.