Abstract

Drawing on new infrastructural scholarship, this paper conceptualises housing as infrastructure, outlining a way forward for housing researchers to draw the concept into their empirical practises. We demonstrate how and why we should research housing as infrastructure, using co-living housing as our empirical touchpoint to develop a framework for infrastructural housing studies. This paper has two parts. First, we identify what it means to conceptualise housing as infrastructure. Infrastructure is: a socio-material system or pattern, relational and generative. Second, we outline some useful vantage points for thinking infrastructurally about housing. We consider affordances, politics and inhabitation as three useful locations to understand the infrastructural work that housing does to order and organise the social world. We suggest thinking infrastructurally about housing can be done by interrogating how the dimensions of infrastructure work to order and organise affordances, politics and inhabitation.

Introduction

This paper advances burgeoning interest towards infrastructural thinking in housing research (Flanagan et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2022; Power et al., Citation2022; Power & Mee, Citation2020). We synthesise interdisciplinary research on infrastructure to develop a framework for infrastructural housing studies, bringing into focus what it means to think infrastructurally and developing a framework to enable researchers to explore the infrastructural work housing performs. Our empirical touchpoint as we develop these ideas is co-living, a new type of housing that offers flexible subscription-style housing and services to hyper-mobile millennial professionals. We do not aim to provide a comprehensive infrastructural analysis of co-living housing. Rather, we use our research into the sector to begin illustrating how infrastructural thinking might be applied in housing studies, including identifying future directions for research on the sector.

In recent years housing and policy research have begun to mobilise the idea of housing as infrastructure, with burgeoning research positioning housing as an infrastructure of care (Power et al., Citation2022; Power & Mee, Citation2020), and social housing as infrastructure for health, wellbeing and economic security (Flanagan et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2022). Our work dovetails with these analyses, pointing to an array of social, economic and political processes that we suggest are infrastructurally supported through co-living housing (Bergan et al., Citation2021; Bergan et al., Citation2023). There appears to be a growing appetite for infrastructural analyses of housing. At the time of writing, Power & Mee’s (Citation2020) paper appeared in the “most cited articles of all time” list on the webpage of this journalFootnote1, sitting alongside papers published as far back as 2006. These collective works on housing and infrastructure sit alongside a flourishing of interdisciplinary infrastructural analyses, including in urban studies and geography, disciplines that are closely allied with housing studies (Amin, Citation2014; Latham & Wood, Citation2015; Rodgers & O’Neill, Citation2012). But while the notion of infrastructure and what it means to think infrastructurally has been unpacked in these other disciplines (Appel et al., Citation2018), the concept is relatively new within housing studies. The purpose of this paper is to engage with this growing field, considering the value of infrastructural thinking within housing studies and conceptualising what it means to engage with housing as infrastructure. We develop a framework for infrastructural housing studies, bringing focus to what it means to think infrastructurally and identifying three epistemological vantage points to see the infrastructural work that housing does. As part of this, we identify the worldbuilding nature of housing infrastructures, arguing that infrastructural approaches allow housing researchers to shine a light on how housing contingently holds up social life. We also identify methodological strategies that might be mobilised by housing researchers seeking to think infrastructurally about housing. We develop this approach by bringing new infrastructural scholarship together with housing research, including examples from our own work on co-living housing.

What is infrastructure and why should housing researchers care about the concept?

In an Editorial for the Special Issue ‘Thinking relationally about housing and home’ in this journal, Easthope and colleagues point to growing interest in relational theory and methods in the discipline. They point to the value of these approaches in ‘opening the black-boxes of housing’ (Easthope, Citation2004, p. 1494), including ‘open[ing] up the house as a site that mediates between the particular and the systemic.’ (Cook et al., Citation2016, p. 1, cited in Easthope et al., Citation2020, p. 1494). Infrastructural research is emerging as part of this thrust, offering a conceptualisation that recognises the productive work of housing: what housing does within social, economic and political practices. In this section, we review research from new infrastructural studies to identify key dimensions of infrastructural thinking. We build from this ontological grounding to set out a framework for thinking infrastructurally in housing research, foregrounding infrastructural affordances, politics and practices of inhabitation.

In new infrastructural studies, infrastructures are recognised as socio-material systems that order and organise social actions and practises. They are dynamic patterns that sit underneath social life, mediating how it unfolds and providing the foundations of social organisation (Star, Citation1999). Infrastructures ‘hold the world up’ by supporting social structures, actions and practises (Berlant, Citation2016, p. 394). Infrastructures influence

…where and how we go to the bathroom; when we have access to electricity or the Internet; where we can travel, how long it takes, and how much it costs to get there; and how our production and consumption are provisioned with fuel, raw materials and transport. It is important to underline what may seem self-evident: infrastructures shape the daily rhythms and striations of social life (Appel et al., Citation2018, p. 6).

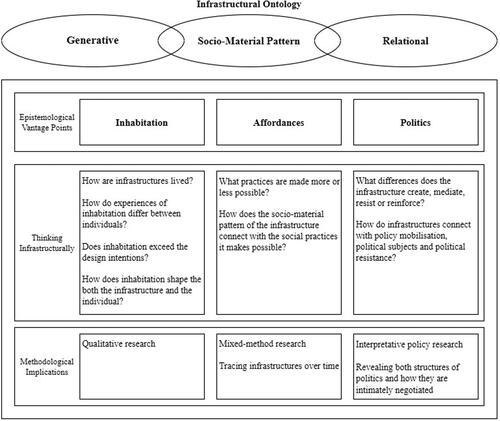

There are three key conceptual foundations shared across new infrastructural approaches (see infrastructural ontology in ) and that underpin the framework we set out in this paper.

First, new infrastructural analyses recognise infrastructures are dynamic socio-material patterns. Infrastructures are recognisable social and material ‘grounds’ that give form and order to social practises. However, while infrastructures are recognisable systems or patterns, new infrastructural scholarship avoids focusing on them as self-contained objects. This is because infrastructures only exist in a deictic relationship to something else. Part of the ‘peculiar ontology’ of infrastructures lies in them being ‘things and also the relation between things’ (Larkin, Citation2013, p. 329). One key way to understand this dimension of infrastructure is to think of it as modal rather than nominal (Boyer, Citation2018). This means that things become infrastructural when ‘doing’ something in the social world.

Second, new infrastructural scholarship recognises that infrastructures are relational, appearing:

… only as a relational property, not as a thing stripped of use’ (Star & Ruhleder, Citation1996, p. 113).

Third, infrastructures are generative and worldbuilding – they actively hold up, order and organise the social world. New infrastructural scholarship has unsettled the idea that infrastructure is ‘simply the backdrop or context to where the real action is’ (Latham & Wood, Citation2015, p. 303), instead recognising how infrastructures shape social action in their own right. New infrastructural analyses foreground that work, they:

question how infrastructures co-constitute urban social life, making it clear that sociality is ‘never reducible to the purely human alone’ (Power & Mee, Citation2020, p. 138).

New infrastructural scholarship recasts housing infrastructures as lively protagonists in social life, rather than limiting portrayals as the bricks and mortar containers that sit in wait for humans to inscribe social practice upon. This is particularly important for researchers seeking to shine a light on the multitude of ways that housing runs underneath social life, by ordering and organising social, political and economic practices. Importantly, conceptualising housing as infrastructure helps explain the relationality of housing. The generative nature of infrastructure is only able to be revealed in relation to the social world and the particular sets of practises that infrastructures enable and coordinate. Uncovering both the generative power and the relationality of infrastructure requires bringing infrastructures from the background to the foreground of analysis. This is the focus of this paper: offering a framework that can guide thinking infrastructurally about housing.

Thinking infrastructurally

In this section, our focus is on identifying three key epistemological vantage points that can direct and structure research. We connect these vantage points to some methodological implications (see . for a diagram of how these fit together).

To think infrastructurally is to engage with the world-making work of infrastructure – identifying infrastructures that support and organise social practice, recognising what it is about infrastructures that enable this work, and tracing the consequences of these relations across time and space. For housing researchers, this means revealing the work of housing, of how housing and the many systems and objects that constitute it, organise and support the reproduction of social life. This brings an epistemological challenge to the social sciences, requiring:

… a focus on world making, on what infrastructural forms do in context and relation to specific sets of actors and practices (Power & Mee, Citation2020, p. 488)

Co-living housing: case study & methodology

In the spring of 2016, WeLive, a subsidiary of the then Silicon Valley success story WeWork, declared its intent to go beyond its usual remit of transforming the way millennial professionals worked, to transform the way they lived. WeLive flipped a vacant 27-story office building on Wall Street into what was labelled ‘a residential utopia’ for millennial professionals. A reporter from GQ trialled the co-living space, finding it a techno-utopia, something like a scene out of HBO’s show ‘Silicon Valley’ (Hansen-Bundy, Citation2018). Hansen-Bundy (Citation2018) said WeLive offered ceaseless networking opportunities with fellow tech-passionate entrepreneurs and ‘sweet’ amenities (including but not limited to a full keg of beer, a barista making complimentary cortados and Ben & Jerry’s ice-cream). WeLive attempted to market an alternate value proposition for housing based on experience and connection rather than physical space or tenure security. Traditionally housing is advertised through reference to its square footage or fixtures, or the security and privacy it affords. Co-living focused its marketing pitch on how it supported work, mobility and social connection (Bergan et al., Citation2021). Co-living was pitched as actively ‘doing’ something beyond providing somewhere to sleep at night. Co-living instead sold an idea or an experience: it marketed how co-living made certain social and economic practises possible (cf. Bergan et al., Citation2021). These representations piqued our interest in what we started to conceptualise as the infrastructural work of co-living.

Co-living providers represented themselves as actively smoothing frictions navigated by millennials in a context where housing is unaffordable, work is insecure, and norms around sharing have changed (Jankel, Citation2017). Co-living providers tried to juxtapose their product with the unattainable or unsuitable urban housing available in global cities. Serious voids for affordable and short-term housing were left by the ‘decline of boarding houses, turn-of-the-century single-sex residency hotels, and [Single Room Occupancy’s]’ (Maalsen et al., Citation2022, p. 7). Co-living providers emphasised flexibility, productivity, freedom and social connection with friends as core domestic experiences afforded through their offering – portraying long-term leases, homeownership and single-family dwellings as antithetical or ill-equipped to provide these experiences. Developers (particularly institutional investors) flocked to a housing type that was bold and self-confident in its marketing and value pitch. Early founders in the industry attracted media attention for playing into and playing up millennial stereotypes. WeLive’s co-founder Miguel McKelvey infamously tried to connect co-living as filling the void left by the decline of religion (Hansen-Bundy, Citation2018). Founder claims that co-living would be both the solution to a purported ‘loneliness epidemic’ and the burning desire of entrepreneurially spirited millennials to found the next start-up unicorn were picked up by media outlets who saw the peculiarity of the rhetoric. The media coverage described a contradiction - co-living offered craft beer on tap, yoga classes on rooftops, and start-up bootcamps in the living room, but offered little personal space, no housing security and was charging a premium fee (Hester, Citation2016; Howe, Citation2018). These ‘dorms for adults’ were priced above market rent in some of the most expensive cities in the world - yet marketed as the solution to the chronic housing crises plaguing cities like New York and San Francisco (Rosenberg, Citation2015). Media representations of the sector oscillated between depicting a millennial ‘utopia’ (Hansen-Bundy, Citation2018), or an example of predatory corporations profiting off a lack of housing for young, precariously employed gig economy workers (Coldwell, Citation2019). Our research responded to the lack of clear evidence around this nascent housing type.

Conducted between 2016-2022, our research has traced the emergence, maturation and transformation of the co-living industry in New York City (NYC), San Francisco and Australia. When we commenced this study in 2016 there was no published peer-reviewed research on co-living. The sector has only operated at a scale large enough to be recognised as a distinct housing type since 2016, and was still in its infancy in 2018 when our first research method was completed. The evidence basis for understanding co-living was initially constrained to media articles, Blogs and Reddit threads. The first method (thematic content analysis of advertising and website materials) was designed to capture a baseline for how the sector was marketing itself and crafting its identity and value proposition. We found co-living was affording new meanings and cultures of home, promoting the ideal home as a place that supported labour mobility, productivity and new forms domestic sociality between non-kin (Bergan et al., Citation2021). The second method was in-depth interviews, conducted in mid-2018 to early 2019. Fieldwork was completed when the industry was relatively nascent with a small but growing number of operators (there were approximately 20 co-living dwellings operating in total across all case study cities)Footnote2. The number of interviews unintendedly represented a large proportion of the co-living businesses operating at the time.

Our intent was to interview both residents and providers. Before heading into the field, 20 individuals working, investing, managing or establishing co-living organisations (identified through Google and the directory website co-living.com) agreed to participate in the study and some agreed to facilitate contact with their tenants. While in the field the organisations began rescinding their willingness to partake in the study due to some negative media coverage and media intrusions on participants’ privacy (cf. Bergan & Power, Under Review). Providers were working to repair the public relations impact of negative articles, and assuring residents their privacy was not at risk. Providers started refusing or rescinding access to tenants and the study necessarily pivoted to recruiting people working in the spaces. Most of our participants did actually live in the spaces themselves, but we identify them primarily as staff because their primary relationship to co-living was arguably a professional one. To build trust with the sector Tegan spent a few months in the field - attending industry events to build rapport. By the time interviews were conducted Tegan and the participants were largely familiar with one another. The semi-structured interviews were relaxed and conversational, with questions designed to scope the nature of the sector, what was included in the service, whom they were targeting as tenants and observations of how tenants used and experienced the service. Qualitative interviews provided an opportunity to invite industry stakeholders to ‘step beyond seamless narratives of intention…and presuppositions of their field’ (Baker & McGuirk, Citation2017:434), and explore what practices sat underneath the highly curated narrative marketed to potential members.

A common finding across the research methods was that co-living was carefully curated to provide specific affordances, though these were not always achieved in practice. Providers described ongoing efforts to rearrange or recalibrate advertised spaces and services to make different social practices more possible; these efforts were identified by tracing the sector over time. The second thematic content analyses and interpretative policy analyses were not planned at the commencement of the study. During the COVID-19 pandemic the sector started to rapidly reframe its core business offerings and spaces in response to government lockdowns and public health policies. The final study captured how the sector rearranged the socio-material layouts within their co-living residences to target travelling healthcare workers and to support specific practices that were encouraged (or mandated) during the pandemic (cf. Bergan & Dufty-Jones, Citation2023). It was this liveliness of co-living –its ongoing morphing and evolution in close relation to people, things, and wider social processes – that drew us to consider the infrastructural work of co-living, and to question what an infrastructural approach to housing might entail.

Like all research, however, there are specificities and limits in our methodological approach that shape our approach and ambitions in this paper. Key amongst these was the challenge of recruiting tenant residents not also employed within the sector. Our focus has therefore been on industry sources. The examples in this paper are framed through this focus, speaking to the ambitions of the sector (how industry players frame and understand their work, both in public promotional documents and anonymous interviews) and observations (by staff living and working in the sector) of tenant experiences and practices in co-living, including efforts to change the sector to alter or redirect tenant practices. From this starting point our intention is not to provide a holistic infrastructural analysis of co-living. Rather, we draw our empirical reflections together with other examples from housing studies and infrastructural research from other disciplines to synthesise and illustrate an approach to infrastructural thinking in housing studies. As we reflect at the end, this is an initial step in research that we hope will be taken up more widely through empirical research across the housing system, particularly with residents. In the next section we demonstrate the epistemological vantage points that were revealed through the empirical research underpinning this project.

Infrastructural affordances

To understand the potential ways infrastructure runs underneath social life is to ask what affordances it provides. Affordances are the specific offerings of infrastructures – the elements of an infrastructure that provide, offer or furnish possibilities for action. In his early development of the concept, Gibson (Citation1979, p. 127) makes the point that affordances are relational – an object affords the possibility of action only in relation to other particular actors. From the standpoint of his ecological research, for instance:

If a terrestrial surface is nearly horizontal (instead of slanted), nearly flat (instead of convex or concave), and sufficiently extended (relative to the size of the animal) and if its substance is rigid (relative to the weight of the animal), then the surface affords support. It is a surface of support, and we call it a substratum, ground, or floor. It is stand-on-able, permitting an upright posture for quadrupeds and bipeds. It is therefore walk-on-able and run-over-able. It is not sink-into-able like a surface of water or a swamp, that is, not for heavy terrestrial animals. Support for water bugs is different.

… enable and constrain trajectories and intensities of flow. Simply put, they are grounds against which specific flows come to figure. And yet, the nature of infrastructural formations is only indexically revealed or apperceived through recourse to such flows.

Affordances is a useful concept for foregrounding how infrastructures make certain actions possible, offering grounds for the reproduction of social practices over space and time. Affordances, as an analytical vantage point, prompts researchers to identify the attributes of infrastructures that support action, as well as the range of possible actions sustained through infrastructural forms. This requires recognition that affordances are not necessarily linear, bounded or intentional. Sometimes infrastructures provide affordances that are purposively designed into them. But they can also furnish affordances that exceed or counter the intentions of those who designed them. Latham & Wood (Citation2015, p. 315) for instance, explore how London’s road infrastructures ‘are simultaneously obdurate whilst also presenting all sorts of opportunities for reinterpretation and reuse.’ Their work unpacks the different ways that cyclists mobilise road infrastructures with bikes, the relational coincidence of roads and bicycles creating new possibilities that enable cyclists to create shortcuts and ‘avoid tricky situations’, ‘filter through gaps and jump traffic queues’, amongst other practices (Latham & Wood, Citation2015, p. 315). Roads facilitate these alternative movements, despite the growing material and governance emphasis on roads as infrastructures of automobility. Infrastructures can also limit and prevent action, or cause harm to some while enabling others. Gibson (Citation1979), for instance, points to how fire affords both warming and burning or how some substances afford nutrition to a certain animal while poisoning another, while Star (Citation1999; 380) comes closer to our concerns in this paper observing how ‘For the person in a wheelchair the stairs and door jamb in front of a building are not subtenders of use, but barriers. One person’s infrastructure is another’s topic or difficulty.’ Importantly, affordances do not dictate action – rather than should be understood in terms of the opportunities for action that an object makes available to a particular body, but which that body may or may not perceive and may or may not take up.

As a vantage point for thinking infrastructurally about housing, affordances is a lens that drives analysis of how housing organises, or patterns, possibilities for social practice, making certain practises more or less possible. This requires identification of the assembled components that constitute housing, including the material dimensions of housing (the housing unit itself), as well as housing policies, technologies and instruments that organise housing markets, and so on. For housing researchers, the starting point might be a particular form of housing, or a set of practises that take place around housing. For example, in our research it was the growing public conversation around co-living housing and its purported benefits that piqued attention. Our research sought to identify what co-living is, what it does and how it does it within social and economic worlds. What we found was an infrastructural form emerging in conjunction with changing labour practices, offering new affordances for sociality and work that complemented and in turn made these labour practices more viable (cf. Watson & Shove, Citation2022 on the co-production of practice and infrastructure). We started by tracing the components of co-living, identifying the common characteristics and inclusions, from the way it is designed and built, through to practices of governance. The next step was identifying practises connected with this housing form and the attributes that make these practises more or less possible. What we identified, as we began to scope in the introductory vignette, was a sector that identifies itself through the provision of integrated domestic and workspaces, with services, subscription-style membership access, and move-in ready furnished housing. In turn these are connected in the sectors’ idealised marketing visions with a series of activities and practices, such as social connections with ‘like-minded people’. Indeed, friends, professional networks or cool roommates are frequently promoted as being included in the subscription fee (Bergan et al., Citation2023; Bergan & Power, Under Review). The promise of these connections is traced in promotional materials to the socio-material layout of co-living residences, which are typically arranged to increase the frequency of social contact between residents. Our analysis of co-living offerings found buildings organised around large communal areas, with reduced individual domestic space (Bergan et al., Citation2023), spatial arrangements designed to push residents out of their private spaces and into shared spaces. In theory, social connection is made more possible through this socio-material configuration – large, shared access spaces offering the affordance (or possibility) of communal gathering. It was also common for spaces to be designed for multiple uses, combining domestic needs with social opportunity. For example, WeLive (cited in Bergan et al., Citation2021) states “from mailrooms and laundry rooms that double as bars and event spaces to communal kitchens, roof decks, and hot tubs, WeLive challenges traditional apartment living through physical spaces…”

Co-living also offers affordances that, in theory at least, encourage productive labour. Co-living as an infrastructure of work and productivity is core to its value proposition. The particular form and affordances of co-living have emerged in conjunction with changing social and economic practices as we began to scope in our earlier vignette (cf. Bergan et al., Citation2021; Bergan et al., Citation2023). For example, housing is accessed through a flexible membership-based subscription model. Rather than a lease, members book the space through an app that offers flexible subscriptions. In a context where mobile work is becoming more common, this enables young professionals to move frequently and quickly between dwellings for work, or to correspond to seasonal flows in work (such as intern season in NYC) (Bergan & Power, Under Review). As one stakeholder commented, this aimed to make moving between Tokyo and NYC as easy as ‘booking an uber’ (Bergan & Power, Under Review). In an economy increasingly organised through gig work, this model offers to enable moving almost instantly for work opportunities, unencumbered by the need to secure and maintain a lease – an infrastructural alignment that supports people to stay in place for longer periods. Co-living is also organised to support productive work through provision of work technologies such as Wi-Fi, coworking spaces or sometimes podcast studios. The services layered onto these spaces include high-end business concierge services typically seen in serviced offices, and domestic services commonly seen in hotels. The socio-material pattern of co-living is intentionally curated to support young professionals in the knowledge economy, catering the needs of staff and industry.

However, affordances are different to guarantees and do not necessarily script practice. The spatial form of co-living cannot, for instance, guarantee that an individual will make friends or build effective work collaborations. This is a point that social practice theorists make clear in their parallel work (cf. Shove et al., Citation2012; Watson & Shove, Citation2022). Rather, it furnishes or encourages social practises supportive or aligned with building social connections or with productive creativity between roommates. An example of this complexity was provided by one participant, who managed a co-living dwelling in NYC. This co-living residence was split across three levels. It was an early building requisition for the company, with a kitchen, bathrooms and shared living/workspace on each separate floor. Despite the business offering building social connections as a central element of its value pitch to tenants, the participant observed that, tenants tended to stick to the floor that their bedroom was on: the layout of the building meant they could meet their essential needs (food, hygiene and work) on that level. This produced limited interaction between residents, who only socialised with the few others also living on their floor. One day, however, the microwave on one of the floors broke, prompting the tenants to go to a different floor to find a working microwave. The housing manager observed how new friendships and connections were supported by this change: tenants were provoked to go to another floor and congregated together while they waited to use the microwave at mealtimes. The informal social contact facilitated by the microwave saw an increase in sociality across the building: the microwave performed as an infrastructural device, creating new affordances for sociality. Learning from this experience, the co-living business reworked its layout, only ever providing one microwave within a building, and in all new buildings providing one large, shared kitchen. This spatial congregation of frequently used shared objects was observed to increase social connections across the building, aiding the promise made within promotional materials. The breakdown of an appliance, and the shared location of another, speak to how the socio-material patterns of infrastructures offer affordances, opening possibilities for some practices while resisting others, in this case increasing incidental contact between residents who require this device (the microwave), through creating new opportunity for social connection.

Infrastructures offer affordances, supporting some sets of practices while making others less likely or more difficult to achieve. For housing researchers, applying the concept of infrastructural affordances involves critical reflection on the practices that are afforded – made possible – by the socio-material organisation of individual houses and the broader housing system. In our work on co-living, we have been interested in how the micro-organisation of housing spaces is connected with the industries’ understanding of the domestic and employment needs of its target audience. However, the offer of affordances is different to their take up: affordances may or may not be taken up, and may attract some individuals while deterring others. More research from the tenant perspective is needed to investigate these factors – as we identify in our later discussion, ‘inhabiting infrastructures’.

Methodologically, appreciating what infrastructure makes possible (the affordances) requires a commitment to tracing. Infrastructural affordances change as infrastructures are repurposed and reorganised for different reasons and in different ways over time. This repurposing only becomes apparent over time. The reuse changes something of what the infrastructure ‘is’. Institutional pressures ensure that not all research can be conducted over long periods of time. However, taking a ‘long-view’ does not necessarily require extended time in the field or historical research (Flanagan & Jacobs, Citation2019). Instead, it can involve approaching contemporary housing infrastructures with a historical sensibility, recognising that infrastructures are a specific articulation at a certain point in time. Infrastructures are temporally fragile, thinking infrastructurally can never make dogmatic claims about what infrastructure is as some form of forever object. Our research material, for instance, provides a snapshot of co-living infrastructure during its emergence, maturation and transformation, recognising that the sector changed between 2016–2022 (most markedly during the pandemic) and may change again in the future. The strategy of tracing avoids what Furlong (2011) critiques as a tendency to foreclose and black-box infrastructures, helping render them more transparent and responsive to interactions with other social and material actors – including the opportunities that they present for ‘reinterpretation and reuse’ (Latham & Wood, Citation2015, p. 315).

Infrastructural politics

The second vantage point we offer to reveal the worldbuilding work of infrastructure is to pay attention to their politics. We define politics as the shifting pole of power that exists between social actors, wider structures and institutions (Dean, Citation2013). Politics is the point of contact between people, power and social structures. Although politics is typically conflated with policy, politics is more-than policy (Bengtsson, Citation2015). Infrastructures are ideal sites for witnessing how broad and abstract social orderings of power play out at the level of everyday social practices and actions (Rodgers & O’Neill, Citation2012). Central to seeing infrastructural politics, is to pay attention to the differences that infrastructures create. Infrastructural politics are revealed in the difference that infrastructures create as they order and organise power. If power is a shifting pole (Dean, Citation2013), revealing infrastructural politics is to look at the ways and directions that infrastructures shift the pole, supporting certain alignments of power while disadvantaging others. In this section, we consider how infrastructural politics can be revealed by looking at how infrastructures organise policy mobilisation, political subjects and political resistance. We trace how housing infrastructures run underneath the mobilisation of certain policies, mediate political subjects through the visions and subjectivities they inspired, and how they are reclaimed and recalibrated to resist wider political regimes.

Thinking infrastructurally shows how housing infrastructures hold up politics by making the mobilisation of certain policies possible. For example, the privatization of public housing stock in the United Kingdom under Margaret Thatcher has been identified as central to advancing a wider neoliberal agenda driven by a particular class project (Hodkinson et al., Citation2013). Changing the terms of housing provision, along with other wider shifts in social welfare and labour markets, ran underneath political institutions shifting towards neoliberal governing logics. Housing runs underneath politics, holding them up, by making the rollout or rollback of certain policies possible. Housing infrastructures allow state power through policies to take a physical form. Infrastructures are sites in which political rationalities are translated into action (Appel et al., Citation2018). Power & Mee (Citation2020), for instance, argue that the caring role of housing has become critical to sustaining the absences of care that have emerged in western liberal states such as Australia, the US and the UK. In western liberal states where care has been privatised, housing systems organise possibilities of caregiving and receiving at a household scale (Power & Mee, Citation2020). Where the policy is to roll back state-sponsored care, housing systems are often recalibrated to support the privatisation of care (though as noted earlier, infrastructures can also be used in ways that exceed design intentions). Importantly, these infrastructural politics become visible through the difference they create. Looking at the infrastructural politics of housing, it is clear that the mobilisation of certain policies creates differences according to social location and power. For example, policies in western liberal states privileging private homeownership, and the privatisation of care, have not affected the population evenly. Citizens who are able-bodied, in secure and well-paid work, are more able to afford and access the necessary goods and services, including housing, to care for themselves (Power & Gillon, Citation2022; Power & Mee, Citation2020). The institutional politics of housing is revealed in the differences it creates for care practices, opportunities and strategies according to an individuals’ tenure form (Power & Gillon, Citation2019).

Infrastructures are also political in the ways that they inspire discourses and subjectivities of political subjects. The politics of infrastructure is not constrained to their technical ability, but their potentiality to create difference through the visions they inspire. Infrastructures ‘express forms of rule and help constitute subjects in relation to that rule’ (Larkin, Citation2018, p. 176). Infrastructures are material and aspirational terrains for ‘negotiating the promises and ethics of political authority, and the making and unmaking of political subjects’ (Appel et al., Citation2018, p. 20). Infrastructures are embodiments of particular intentions or information that govern the spaces of everyday life – and thus govern everyday life (Easterling, Citation2014). Politics – in the form of intentions, information and ideas – are coded into infrastructure and reproduced through use. Despite the hidden ‘background’ role of infrastructures, they are the powerful ‘content manager dictating the rules of the game in the urban milieu (Easterling, Citation2014, p. 14). They dictate the rules of the game through the powerful visions and subjectivities they support.

The importance of housing in supporting the subjectivities of ‘good’ citizens was apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic. In places where lockdowns were instituted, secure housing was a critical infrastructure supporting ‘responsible’ citizens to stay-at-home. Many without secure housing, or in housing that did not meet their needs, experienced stress and a crisis of care (Bowlby & Jupp, Citation2021). In our research, we observed how co-living providers reoriented to support subjectivities of moral responsible citizenship during the pandemic. In NYC providers flipped their core business offerings so that they could continue operating. When the government mandated ‘Stay-at-Home’ orders to try to reduce viral transmission by encouraging individuals to socially isolate inside their homes except for absolute necessities (i.e. purchasing food), the sector advertised the importance of ‘tribe survival’, inspiring visions of collective responsibility and caring for fellow mankind. The sector suggested that by staying in co-living dwellings, individuals could collectively care for each other, and access centralised services such as food deliveries that fed the entire household. For instance, several co-living providers introduced new protocols and policed who could enter the dwellings; limiting access to only the residents or workers (Common and Outside, cited in Bergan et al., Citation2021). Similarly, many operators increased deliveries of groceries and cleaning products to minimise the need for residents to leave their accommodation. Cohabs (Citation2020, cited in Bergan et al., Citation2021) even provided quarantine packs for those needing to self-isolate. Responsible citizen subjectivities were also advertised to surge healthcare workers, reserving entire dwellings for workers who were being mobilised to support the city’s struggling healthcare system. Co-living providers actively positioned their dwellings as infrastructures that would enable this group to protect their families, roommates and fellow citizens. New services were included in the offer, including Uber vouchers to purportedly reduce the risk of transmitting the virus on public transport. While research with tenants is required to confirm the degree to which tenants accepted and adopted these infrastructural offerings, this imagery speaks to the sector’s imagined role as an infrastructure supporting individual civic responsibility, enabling residents to take care of themselves and society in a public health crisis. Viewed from a critical perspective, the sector emerges in this public positioning as an infrastructure that fills gaps in a public care system that has experienced underfunding and privatisation in line with neoliberally informed systemic change, alongside its support for practises of reduced labour security that are grounded in similar ideological shifts.

The infrastructural politics that emerge within the public positioning of co-living has largely affirmed neoliberal governments, prioritising home and work practices in ways that ameliorate the frictions of care deficits and labour market precarity. However, infrastructural politics can also operate in ways that counter dominant political logics. Applying infrastructural politics to housing is a lens that can reveal where housing infrastructures are co-opted to resist wider political logics, including where affordances of infrastructures are used in ways that are counter their intended use - unpacking this work in co-living will require future research with tenants. Housing infrastructures do not simply enable or limit politics, they can also ‘become sites for political contest and change’ (Power & Mee, Citation2020, p. 489). Housing policy is not impermeable, for example, previous work has shown how environmental rationalities have reshaped traditional housing policies (Murdoch, Citation2000). Murdoch (Citation2000) identifies that pressure from local homeowners in the United Kingdom (UK) led to changes in national housing policy. Thinking infrastructurally involves seeing the politics embedded and embodied in infrastructure as a shifting pole. The politics and the infrastructure can transform each other. Housing infrastructures are not passive outcomes of housing governance and policy settings, they are linked to the processes of resisting, entrenching and transforming wider politics. More than just uncovering how an infrastructure reflects dominant political logics, revealing infrastructural politics must also include focusing on how meaningful attachments to infrastructures can exceed the political rationalities coded into them, allowing them to be sites for contest and change. Infrastructures can be reclaimed or recalibrated so that they push back against broader structural systems. Returning to the work of Power & Mee (Citation2020), social difference and social actors can repurpose and resist the usual infrastructural orderings by inhabiting the infrastructure in unexpected ways. The UK 1970s ‘hippie communes’ were collectively owned ‘commons’ (Arbell et al., Citation2020), fostering political subjectivities and ‘non-capitalist’ identities in resistance to Thatcher’s neoliberal policies. Communes were a counter-cultural strategy of asserting difference from capitalist ideals of individualism (Arbell et al., Citation2020). Infrastructures can become symbols for the political rationalities coded into them (Larkin, Citation2018). Infrastructures – both new or existing ones that are deployed in ways counter to their intended use - can be enrolled to resist the translation of housing policy and other political rationalities. Future research into co-living must engage with the experiences and practices of tenants, identifying the extent to which they take up the affordances that are the public face of the sector, or the small and large ways that they re-write what it is that the sector can do.

In this section, we have looked at how infrastructural politics run underneath broader systems of power. In the next section, we consider how infrastructures are inhabited. However, before we begin, we acknowledge that power in mediating and creating differences cuts across both inhabitation and politics as vantage points. The political work of infrastructure threads through infrastructures in the ways they are mobilised underneath wider political structures but also in how they are inhabited and experienced. For the purposes of developing an infrastructural framework for housing studies, we differentiate infrastructural politics as a vantage point that considers how infrastructures run underneath the construction and operation of broader arrangements of power. In contrast, the second vantage point of inhabitation focuses on how individuals experience broader arrangements of power within infrastructural spaces. While these are not neatly delineated categories, we think it is productive to understand the different ways that infrastructures run underneath multiple scales of social life – from the construction of broader structures of power as well as how those structures are intimately experienced. Infrastructures work across scales, organising the way that power and politics produce both the intimate experiences of everyday life and global power structures. Indeed, Appel et al. (Citation2018, p. 20) see this as ‘a sign of infrastructures capaciousness…that we can use it to think across radically different scales – from planetary epochs to the most intimate acts of individuals’ families and communities. The capaciousness of infrastructure in working across scales is a familiar epistemology in housing research, with domestic spaces long mobilised as a site to understand both the production of global systems of power and personal experiences of powerful systems (cf. Power et al., Citation2022). Methodologically, this means to reveal how the infrastructure translates political rationalities into social practices. This means researching both the structural settings governing infrastructure, and the experiences of inhabiting or dwelling within them. For our research, we focused on revealing not just what the housing and public policy settings were that governed co-living during the pandemic, but how they were interpreted and translated into co-living residences by providers (Bergan & Dufty-Jones, Citation2023). We conducted an interpretive policy review of health and housing policies in effect as a first step. An interpretative policy analysis takes a qualitative approach to policies, looking to the meanings of a policy rather than the quantitative costs of enforcing a policy. We then reviewed how these policies were deployed within the sector in NYC. We found that the broad institutionally precarious governance settings were being practised in diffuse and contingent ways. Related to politics and the differences they create is the work that infrastructures do to shape experiences of inhabitation.

Inhabiting infrastructures

Thinking infrastructurally entails shining a light on the multiple and often divergent experiences of living in infrastructural space. The final vantage point we identify for drawing infrastructural thinking into housing studies involves looking at how infrastructures are inhabited. Infrastructures ‘press into the flesh’ (Fennell, Citation2015, p. 32), they are an intimate point of contact between wider social processes, structures and daily life. The experiences of inhabiting an infrastructure can be mundane or unremarkable, like catching a train, flushing a toilet or turning on a light. But these experiences profoundly shape how people move, feel and connect in the social world - they also shape the infrastructure. Some early infrastructural scholarship tended ‘…to interpret the impact, function and use of [infrastructural] technologies as given’ (Furlong, 2011, p. 461). As Latham & Wood (Citation2015, p. 303) caution, this risks overlooking the ‘often small-scale, localised or incremental processes through which infrastructural systems might be subtly altered or transformed over time’. Inhabitation is a vantage point that draws attention to the often-mundane ways that infrastructures and their inhabitants transform one another. Witnessing how infrastructures are inhabited offers a vantage point for how material, political, and affective dimensions of social life are negotiated individually and intimately as well as revealing intersectional experiences of infrastructures.

The experiences of dwelling in housing can be radically different from one person to the next. Infrastructural configurations are typically ‘built around certain taken-for-granted notions of how an infrastructure will be used and who will be using it, but this does not necessarily reflect its relationship to the practices of inhabitation’ (Latham & Wood, Citation2015, p. 301). The ways housing infrastructures are inhabited can exceed or counter design intentions. For example, experiences of the social affordances of the microwave in our earlier example varied vastly between residents. Although the provider proudly stated how locating the microwave in a communal space structured opportunities for social connection, he also disclosed that residents often moved on from the dwelling after a few months, using co-living as a ‘waypoint’, rather than a destination. He identified social fatigue as a significant driver of transience, explaining that after a while, people would get sick and tired of constantly socialising with strangers – like needing to introduce themselves to people when doing simple things like heating up food. What this provider describes is a housing infrastructure structuring mobility in intended and unintended ways: organised to support residents to move for short-term employment contracts, but also driving mobility amongst residents who experience social fatigue living in a dwelling that is organised to foster sociality. Another example is the organisation of co-living dwellings to support productive work. While some residents use the workspaces in anticipated ways, this is far from uniform. One provider in San Francisco, for instance, explained that no current housemate used the makerlab, despite it being popular with previous tenants. Similarly, a provider in NYC discussed how certain cohorts of roommates were more productive than others: sometimes coworking spaces would be filled with interns working away on various projects, while at other times they would sit empty, with housemates more interested in engaging with the social opportunities of the house such as daytrips or house dinners. Although the houses did not necessarily change, they were inhabited and experienced differently depending on the individual needs, priorities and interests of residents and the ways that these collectively combined at different times. These examples point to the divergent affects of infrastructural affordances, which generate diverse experiences and responses from residents, and who sometimes mobilise them in ways that exceed design intentions.

Infrastructures are also inhabited in ways that are profoundly intersectional, reflecting differences in identity and social position. Intersectionality describes how social categorisations, such as gender, class, or race, overlap to create unique geometries of advantage or disadvantage. Thinking infrastructurally about the inhabitation of infrastructures responds to the call for intersectional analysis to:

…consider the spatial inclusions and exclusions created by the material forms and social practices within domestic dwellings and the ways in which the environment of the dwelling becomes bound up with and modified by social practices… (Bowlby, Citation2019, p. 45)

Inclusion and exclusion can occur through the inhabitation of infrastructure. Interrogating everyday practices of inhabiting draws feminist and decolonial epistemologies into infrastructural research (Boano & Astolfo, Citation2020; Lancione, Citation2020). Housing has a rich history of ordering and organising gender through the intersectional experiences of domestic spaces (Gorman-Murray, Citation2012). Feminist research on housing from the 1970s, for instance, recognised how dominant forms of housing design and development worked to reinforce gendered divisions of domestic labour and sociality. Although not using the language of infrastructure, this work makes clear how the intended design of housing as privatised dwellings for individual family groupings, as well as the separation of spaces of work and home through the suburbanisation of housing from the mid-twentieth Century, worked in conjunction with gendered cultures of home to increase women’s domestic labour while making participation in paid work less viable.

Infrastructural inhabitation can reproduce intersectional differences. For example, Dowling & Power (Citation2012) research the cultural underpinning and social practices driving large housing in Australia. Their work shows that large suburban detached dwellings afford powerful visions of home and family. However, this spatial expansiveness, in conjunction with gendered norms of home and domesticity, worked to reinforce and expand women’s domestic labour responsibilities. When looking at how individuals use and experience large housing, Dowling & Power (Citation2012, p. 617) noted ‘it was women who did the work of managing mess, of cleaning the houses and of overseeing the complex family routines’. The affordances of expansive family living, freedom and privacy were negotiated differently according to individuals’ social locations. In this case, the gendered burden of domestic labour, children and respectability thread through large houses as infrastructures, creating intersectional differences in inhabitation. Gendered experiences of inhabitation were apparent in co-living residences. For example, when we asked a housing manager in San Francisco about their ‘typical’ member, they responded ‘mainly it is of course men’. When we asked if this was because there was not much privacy, she sighed and responded:

Maybe. Also shared spaces like shared bathroom, it’s more - women are more sensitive for that, you know? So guys are going better with that. But anyway, it’s all right. Sometimes we’ll have like only two girls in the house. Sometimes it’s more. For the time being, I can tell you in percentage, but maybe 30 per cent of the guests are all women now. But mainly, it’s guys.

If infrastructures are the systems that run underneath practices, inhabitation is a lens that calls for researchers to look at the experiences of dwelling within these dynamic systems. Methodologically research can seek to make the practices of inhabitation visible - the embodied, situated and sensory experiences of dwelling in the infrastructure. Qualitative inquiry lends itself to uncovering the multiple, contingent and relational experiences of inhabitation, with methods like in-depth interviews a mainstay in research on housing and home (e.g. Arbell et al, Citation2020; Dowling & Power, Citation2012; Power & Gillon, Citation2022). Inhabitation practices are deeply personal, intimate and often mundane. They reveal both the affordances and the politics coded into infrastructures. To animate infrastructural inhabitation, a focus must be placed on the lived experiences, individual practises and intimate entanglements between people and infrastructural forms. This means appreciating how individual people engage with the infrastructure in different ways. This means to see the infrastructure and the individual as being in conversation with one another – speaking back and forth, reciprocal. To pay attention to the conversation between infrastructures and individuals is to observe how the infrastructure ‘presses into the flesh’ but also how the flesh presses back into the infrastructure. Our co-living research has been limited by the methodological reliance on observational accounts of staff living and working within the co-living sector. Future research in this sector will benefit from engagement with non-employee residents, a practice that will likely become more possible as media interrogation of the sector reduces over time.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have set out a framework for thinking infrastructurally about housing. Our work is motivated by the infrastructural turn in the social sciences and recent contributions that have begun to explore the work of housing as an infrastructure of care, health, wellbeing and economic security. Inspired by these accounts and synthesising interdisciplinary infrastructural scholarship, we have conceptualised what it means to think about housing infrastructurally, arguing that housing is a powerful infrastructure – relational, generative and dynamic socio-material pattern – that furnishes possibilities for social life. This conceptual work is our primary contribution in this paper, and one that we have augmented via our own work and analysis of co-living housing.

Our central contribution is identifying infrastructural affordances, politics and inhabitation as three epistemological vantage points for housing researchers to conceptualise the infrastructural work of housing. First, identifying infrastructural affordances involves looking at the social, political, economic and cultural practices and actions that are made more or less possible by the infrastructure. It also involves unpacking infrastructural forms to identify the elements that contribute to and organise these practices. For example, co-living infrastructures furnish possibilities for productive work, mobility and domestic sociality with non-kin. They do this through the material forms, contractual relationships and service inclusions of co-living housing, amongst other attributes. Second, revealing infrastructural politics requires paying attention to the differences that infrastructures create. For example, we explored how co-living housing intersects with institutionally precarious housing governance and policy – emerging to fill a gap in ways that both address and consolidate the precarity of digital nomads whose needs remain unmet in the mainstream housing system. Third, we have identified that understanding the inhabitation of infrastructures involves seeing the ways that infrastructures are intimately and intersectionally inhabited. We pointed to how co-living infrastructures are experienced differently according to an individual’s social location.

In addition to setting out a conceptual approach for thinking infrastructurally about housing, this paper has also identified a series of methodological approaches for this work. We identified how tracing affordances over time helps reveal the dynamic and relational nature of infrastructure. Second, we pointed to the importance of identifying the disruptions or troubled transmissions (Berlant, Citation2016) between the politics coded into infrastructures and the politics reproduced through infrastructures. Analysing how infrastructures interpret and translate political rationalities is key to understanding how they mediate relationships between people, other infrastructures, and wider structures of power. Finally, we recommended enriching infrastructural analysis with qualitative insights to help unpack intersectional differences in how infrastructures are inhabited.

Infrastructural thinking has much to offer housing studies, foregrounding the worldbuilding work of housing and the ways that housing makes certain social practices more or less possible. Yet we conclude by cautioning against suggesting that an infrastructural agenda sits in opposition to current research agendas in housing studies. As Gabriel & Jacobs (Citation2008, p. 538) state in their work setting out post-social thinking in housing studies, our message is

not one of theoretical salvation nor should it be seen as encouraging housing researchers away from the empirical projects at hand, but it does require researchers to look more closely at their practice and to ask what is missing or silenced within their present accounts.

Infrastructural thinking offers affordances for housing researchers, making research that accounts for the generative nature of housing in holding up social life more possible. We hope that infrastructural approaches will be translated into housing policy and practice in ways that affirm that housing matters to social life. Housing infrastructures are more than containers for social life, rather housing iteratively underwrites social life. For housing researchers, thinking infrastructurally about the work that housing does in running underneath critical social practices such as work, care, mobility and health might be a pathway to highlight the risks engendered through some forms of housing, while also advocating for greater institutional support of appropriate and safe housing infrastructure for everyone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tegan L. Bergan

Tegan L. Bergan is a housing researcher. Her PhD research examined co-living housing in New York, San Francisco and Australia. Her research has investigated how co-living housing operates as an infrastructure of markets, work and everyday life.

Emma R. Power

Emma R. Power is an urban geographer thinking about housing, home and the caring city. She is an Associate Professor in the School of Social Sciences and Institute Fellow in the Institutefor Culture and Society at Western Sydney University.

Notes

1 Page viewed 12/10/2022.

2 The small size of the sector is why no descriptive identifiers are provided for the interview participants in the data analysis. It is also why cities are specified in the USA (where more organisations were operating) as opposed to in Australia.

References

- Amin, A. (2014) Lively infrastructure, Theory, Culture & Society, 31, pp. 137–161.

- Appel, H., Anand, N. & Gupta, A. (2018) Temporality, politics and the promise of infrastructure, in The Promise of Infrastructure (pp.1–38). Durham; London: Duke University Press.

- Arbell, Y., Middlemiss, L. & Chatterton, P. (2020) Contested subjectivities in a UK housing cooperative: Old hippies and thatcher’s children negotiating the commons, Geoforum, 110, pp. 58–66.

- Baker, T. & McGuirk, P. (2017) Assemblage thinking as methodology: Commitments and practices for critical policy research, Territory, Politics, Governance, 5, pp. 425–442.

- Bengtsson, B. (2015) Between structure and thatcher. Towards a research agenda for theory-Informed Actor-Related analysis of housing politics, Housing Studies, 30, pp. 677–693.

- Bergan, T. L. & Dufty-Jones, R. (2023) Co-living housing-as-a-service and COVID-19: Micro-housing and institutional precarity, in: E. Harris, M. Nowicki, & T. White (Eds) The Growing Trend of Living Small: A Critical Approach to Shrinking Domesticities (Boca Raton, FL: Routledge). https://www.routledge.com/The-Growing-Trend-of-Living-Small-A-Critical-Approach-to-Shrinking-Domesticities/Harris-Nowicki-White/p/book/9780367764463

- Bergan, T. L., Gorman-Murray, A. & Power, E. R. (2021) Coliving housing: home cultures of precarity for the new creative class, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1204–1222.

- Bergan, T. L., Gorman-Murray, A. & Power, E. R. (2023) Co-living Housing-as-a-Service and COVID-19: Micro-housing and Institutional Precarity, in: E. Harris, M. Nowicki, & T. White (Eds.), The Growing Trend of Living Small (pp. 13–27). London: Routledge.

- Bergan, T. L., Gorman-Murray, A. & Power, E. R. (2023) Co-living, gentlemen’s clubs, and residential hotels: a long view of shared housing infrastructures for single young professionals, Housing, Theory and Society, 40, pp. 679–694.

- Berlant, L. (2016) The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times*, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34, pp. 393–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989

- Boano, C. & Astolfo, G. (2020) Inhabitation as more-than-dwelling. Notes for a renewed grammar, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 555–577.

- Bowlby, S. & Jupp, E. (2021) Home, inequalities and care: perspectives from within a pandemic, International Journal of Housing Policy, 21, pp. 423–432.

- Bowlby, S. (2019) Caring in domestic spaces: Inequalities and housing, in: E. Jupp & S. Bowlby (Eds.), The New Politics of Home: Housing, Gender and Care in Times of Crisis (pp. 39–62). Bristol: Policy Press. Available at http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uwsau/detail.action?docID=5789783

- Boyer, D. (2018) Infrastructure, potential energy, revolution, in: N. Anand, A. Gupta, & H. Appel (Eds.), The promise of infrastructure (pp. 223–244). Durham: Duke University Press.

- Carruthers, A. M. (2020) Intensity, infrastructure, aquatectonics, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38, pp. 820–825.

- Cohabs (2020) COVID-19: Your safety is our priority. Available at https://www.cohabs.com/covid-19-coliving (accessed 10 July 2020).

- Coldwell, W. (2019) “Co-living”: The end of urban loneliness – or cynical corporate dormitories? The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/sep/03/co-living-the-end-of-urban-loneliness-or-cynical-corporate-dormitories

- Cook, N., Davison, A. & Crabtree, L. (2016) The politics of housing/home. In Housing and home unbound (pp.1–16). New York: Routledge.

- Dean, M. (2013) The Signature of Power: Sovereignty, Governmentality and Biopolitics. New York: Sage.

- Dowling, R. & Power, E. (2012) Sizing home, doing family in sydney, Australia, Housing Studies, 27, pp. 605–619.

- Easterling, K. (2014) Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. New York: Verso Books.

- Easthope, H. (2004) A place called home, Housing, Theory and Society, 21, pp. 128–138.

- Easthope, H., Power, E., Rogers, D. & Dufty-Jones, R. (2020) Thinking relationally about housing and home, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1493–1500.

- Fennell, C. (2015) Last Project Standing: Civics and Sympathy in Post-Welfare Chicago. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. Available at https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/last-project-standing

- Flanagan, K. & Jacobs, K. (2019) ‘The long view’: Introduction for special edition of housing studies, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 195–200.

- Flanagan, K., Martin, C., Jacobs, K. & Lawson, J. (2019) A conceptual analysis of social housing as infrastructure, AHURI Final Report No. 309, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne. Available at http://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/309. doi: 10.18408/ahuri-4114101

- Gabriel, M. & Jacobs, K. (2008) The post-social turn: Challenges for housing research, Housing Studies, 23, pp. 527–540.

- Gibson, J. J. (Ed.) (1979) The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Taylor & Francis. Available at 10.4324/9781315740218

- Gorman-Murray, A. (2012) Meanings of home: Gender dimensions, in S. Smith (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home (vol. 4, pp. 251–256). London: Elsevier.

- Hansen-Bundy, B. (2018) A week inside WeLive, the utopian apartment complex that wants to disrupt city living. GQ. Available at https://www.gq.com/story/inside-welive

- Hester, J. (2016) A Brief History of Co-Living Spaces. Bloomberg. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-22/a-brief-history-of-co-living-spaces-from-19th-century-boarding-houses-to-millennial-compounds

- Hodkinson, S., Watt, P. & Mooney, G. (2013) Introduction: Neoliberal housing policy – time for a critical re-appraisal, Critical Social Policy, 33, pp. 3–16.

- Howe, N. (2018) Millennials and the loneliness epidemic. Forbes. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/neilhowe/2019/05/03/millennials-and-the-loneliness-epidemic/

- Jankel, N. (2017) “Bright Flight” & The Co-Living Revolution: Disrupting The Future of Cities. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-co-living-revolution-disrupting-the-never-disrupted_b_5935647de4b00573ab57a54a

- Jones, C. & Slater, J. (2020) The toilet debate: Stalling trans possibilities and defending ‘women’s protected spaces, The Sociological Review, 68, pp. 834–851.

- Lancione, M. (2020) Radical housing: on the politics of dwelling as difference, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 273–289.

- Larkin, B. (2013) The politics and poetics of infrastructure, Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, pp. 327–343.

- Larkin, B. (2018) Promising forms: The political aesthetics of infrastructure, in N. Anand, A. Gupta, & H. Appel (Eds.), The Promise of Infrastructure (pp.175–202). Durham: Duke University Press.

- Latham, A. & Wood, P. R. H. (2015) Inhabiting infrastructure: Exploring the interactional spaces of urban cycling, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47(2), pp. 300–319.

- Lawson, J., Troy, L. & van den Nouwelant, R. (2022) Social housing as infrastructure and the role of mission driven financing, Housing Studies, 39, pp. 398–418.

- Maalsen, S., Shrestha, P. & Gurran, N. (2022) Hacking housing: Theorising housing from the minor, International Journal of Housing Policy, 22, pp. 1–9.

- Murdoch, J. (2000) Space against time: Competing rationalities in planning for housing, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 25, pp. 503–519.

- Power, E. R. & Gillon, C. (2019) How housing tenure drives household care strategies and practices, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 897–916.

- Power, E. R. & Gillon, C. (2022) Performing the ‘good tenant, Housing Studies, 37, pp. 459–482.

- Power, E. R. & Mee, K. J. (2020) Housing: an infrastructure of care, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 484–505.

- Power, E. R., Wiesel, I., Mitchell, E. & Mee, K. J. (2022) Shadow care infrastructures: Sustaining life in post-welfare cities, Progress in Human Geography, 46, pp. 1165–1184.

- Rodgers, D. & O’Neill, B. (2012) Infrastructural violence: Introduction to the special issue, Ethnography, 13, pp. 401–412.

- Rosenberg, Z. (2015) Dorms for grown-ups have descended on New York city. Curbed NY. Available at https://ny.curbed.com/2015/4/21/9968360/dorms-for-grown-ups-have-descended-on-new-york-city

- Shove, E., Pantzar, M. & Watson, M. (2012) The Dynamics of Social Practice. London: SAGE.

- Star, S. L. & Ruhleder, K. (1996) Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: Design and access for large information spaces, Information Systems Research, 7, pp. 111–134.

- Star, S. L. (1999) The ethnography of infrastructure, American Behavioral Scientist, 43, pp. 377–391.

- Watson, M. & Shove, E. (2022) How infrastructures and practices shape each other: Aggregation, integration and the introduction of gas Central heating, Sociological Research Online, 28, pp. 373–388.