Abstract

Following housing protests in 2011, Israeli politicians advanced a program to create a massive supply of rental housing and enact new rental regulations. A few years later, the focus shifted to a program that encouraged homeownership. We analyze newspapers’ coverage of this process, and the representation of actors, location and of social, spatial, and physical themes. We investigate whether, and how, the discourse reflected or challenged the prevalence of property interests and the neoliberal ideology. Our findings show that despite early tensions and debates, throughout the process, renters and their issues received limited representation, while the discourse highlighted market means and images, and the population that could buy and invest. Eventually, the media interest in the program was replaced by fascination with homeownership and investments. In this vein, rentiership – the option to become owner-investors – was highlighted as the state’s popular solution for the housing crisis. We conclude that in this context, rental reforms are unlikely to garner significant social support.

Introduction

In many countries, homeownership has become increasingly less affordable, and a growing and age-diverse sector is now renting housing in the free market (Kemp, Citation2015; Powell, Citation2015) for extended periods (Bierre & Howden-Chapman, Citation2020; Crook & Kemp, Citation2014; McKee et al., Citation2017). Scholars argue that as result, in homeowner societies, it is now challenged as the prevailing social norm and the natural ‘tenure of choice’ (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017; Hulse et al., Citation2019; Kohl, Citation2018; McKee et al., Citation2017). Scholars also show that several governments have responded to this challenge with programs to expand and regulate the rental market (Hulse et al., Citation2019; Kemp, Citation2015; Martin et al., Citation2018; Nethercote, Citation2020).

We analyze media discourse surrounding such a state program in Israel, and address its chances to gain wide social legitimacy. In that, we contribute to contemporary studies that show renters’ weak position in Anglophone homeowner societies (Bierre & Howden-Chapman, Citation2020; Brill & Durrant, Citation2021; Hulse et al, Citation2019; McKee et al., Citation2017). We also follow current understandings of mass media as a key advocacy arena (Bierre & Howden-Chapman, Citation2020; Hastings, Citation2000; Jacobs et al., Citation2003; Jacobs & Manzi, Citation2014), where social values are reflected and shaped and policy is legitimized or side-stepped (Fairclough, Citation2003; Jacobs & Manzi, Citation2000; Murphy, Citation2016). We focus on the discursive tensions created between the policymakers’ intention to help renters and the voices wishing to maintain neoliberal property-related preferences in housing. To do this, we analyze the discourse surrounding the program and related rental issues in the principal Israeli newspapers (online and offline), and ask, how they represented actors, locations and themes, and whether they challenged or maintained neoliberal or other ideas and interests.

Ronald (Citation2004, Citation2008) outlined the relationships between housing tenure, ideology, and state concerns by stressing the significance attached to homeownership, particularly since the 1980s, as a means to maintain social stability and political legitimacy. In Israel and many other countries, these decades have been marked by the prominence of neoliberal ideology, which replaced the earlier Keynesian-welfarist paradigm. Neoliberalism stemmed from the ‘free market’ doctrine associated with the writings of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman (Brenner et al., Citation2010). It emphasizes individual freedom, economic efficiency, as well as privatization, reduced state involvement, and thin bureaucracy (Charney, Citation2017; Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Peck et al., Citation2013; Sager, Citation2013).

Governments that adapted this ideology promoted the commodification of many fields (Brenner et al. Citation2010), and simultaneously advanced a new social ‘contract’ that transferred numerous duties of the welfare state to individual citizens (Dodson, Citation2007; Harvey, Citation2013). Thus, while Keynesian welfare states invested in housing creation and accessibility, in the supply of homes to wide sectors, and in the encouragement of homeownership to provided social stability (Adkins et al., Citation2021), neoliberal governments reduced their direct investments in housing supply and accessibility and encouraged people to acquire homes and take responsibility ‘for their own living conditions’ (Sager, Citation2013, p. xxvii). This also meant the incentivizing of entrepreneurs to take dominant part in housing building for sell (Marcuse & Madden, Citation2016), interpreting dwellings as assets (Sager, Citation2013) and the marking of homeownership as fulfilling the new social contract, by leading to individual freedom, strength, and success (Kern, Citation2010).

Scholars showed that this agenda played a major role in the formulation of housing policies and discourses (Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2009; Munro, Citation2018; Murphy, Citation2020). It was complemented by additional factors. First, reduction in the supply of affordable and public housing and in the regulations protecting residents (Crook & Kemp Citation2014; Whitehead et al., Citation2012). Second, further encouraging of homeownership and individual housing acquisitions with subsidies, tax deductions, and attractive mortgages (Halbert & Attuyer, Citation2016). Lastly, support of financialization, namely the dominance of financial actors, institutions, and their market narratives, practices, and measurements (Aalbers, Citation2016; Nethercote, Citation2020).

Recently, scholars have pointed out a fourth factor: support of rentiership, defined as ‘the extraction of economic rents from the ownership and/or control of assets and resources’ (Birch & Ward, Citation2023, p. 1; Adkins et al., Citation2021). After the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, governments encouraged such popular real-estate investments, especially in residences (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017; Jacobs et al., Citation2022); for example, through tax deductions in Australia (Adkins et al., Citation2021), or the regulation of specific mortgages for ‘buy to let’ acquisitions in Australia, the UK, and the US (Crook & Kemp, Citation2014; Whitehead et al., Citation2012).

Combined, the planning, allocation and realization factors were articulated by policymakers in a preference for public-private projects (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2013; Fainstein, Citation2008; Tasan- Kok, Citation2008), high-standard dwellings (Marcuse & Madden, Citation2016; Sager, Citation2013) and expensive towers (Fainstein, Citation2008; Margalit & Alfasi, Citation2016), and fashionable housing blocs and/or neighborhoods (Boland et al., Citation2017; Hubbard, Citation2004). This also entailed targeting affluent social groups and central locations (Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Sager, Citation2013), while ignoring people who could not buy or invest (Marcuse & Madden, Citation2016).

These factors and preferences were supported in media discourses that presented them and the neoliberal order more generally as ‘default assumptions’ (Fuchs, Citation2009, p. 17). The deepening shortage in public and affordable rental housing, together with the encouragement of homeownership and expensive projects, pushed housing demand and prices (Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Marcuse & Madden, Citation2016; McKee et al., Citation2017). For many lower- and middle-class families, private renting became the only option (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017; Bone, Citation2014; Winke, Citation2021). With financialization and rentiership, ‘widespread homeownership has in fact arrested and reversed the growth of homeownership’, (Adkins et al., Citation2021, p. 560), as both property prices and rents rose (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017; Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015; McKee et al., Citation2017). This was especially evident in Anglophone homeowner societies – Australia, Ireland, the UK, the US, and New Zealand (Bierre & Howden-Chapman, Citation2020; Hulse & Yates, Citation2017; Kemp, Citation2015).Footnote1

Similar process was evidenced in Israel, also a homeowner society. There are no national statistics on the rental units, but reports have shown that since the early 2000s, fewer households could buy a unit. As result, the share of private renting expanded to 23% of households, and even higher in central cities.Footnote2 At the same time, a sharp rise of 300% in the number of households owning two or more units indicates that rentiership is on the rise. This evolution deepens socio-spatial stratification and divides Israeli society along the lines of ownership, with less affluent households spending 30% to 62% of their net income on rent, and 70% of these payments going to more affluent owner-investors (Swirski & Dishon, Citation2016).

In 2011, a sharp rise of 47% in the cost of housing within two years (Raz-Dror, Citation2019), and weak rental regulations, led young people from Tel Aviv-Jaffa to initiate massive social protests (Alfasi & Fenster, Citation2014). They were soon followed by millions across Israel. The events led national politicians to initiate a housing reform, including an ambitious rental program that centered on the establishment of a state company named ‘Apartment for Rent’ (APRent)Footnote3 by then Minister of the Finance, Yair Lapid. While the Israeli rental market is largely controlled by private landlords, APRent was instructed to collaborate with institutional investors (e.g. pension and insurance companies) and promote mass construction of rental housing within a decade. Studies showed that a similar approach was undertaken, for example, in the UK, where the state encouraged the involvement of large companies in the rental market with state funds (Kemp, Citation2015), or in USA, Spain and Germany, where incentives included special loans, guarantees, tax deductions and state funds (Martin et al., Citation2018).

While these studies have focused on policy mechanisms, our focus is on the popular discourses legitimating or opposing the rental programs. In analyzing their media coverage, we identify two meaningful tensions, and argue that both stem from the dominancy of the neoliberal free market doctrine. First, a tension between welfarist statements supporting the need to supply housing to young people and statements criticizing the programs’ as incompatible with the overarching preference for homeownership. Second, a tension between the expectation that the government solve the housing problem, and objection to its intervention in the free market.

To reveal these discursive tensions and how they evolved in the years after the initiation of the rental program, we analyzed the coverage of this program and related rental issues. We used the critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, Citation2003, Citation2013), and analyzed the media representation of actors, locations, and social, spatial and physical themes. We found that the said tensions mainly existed in early media debates, and disappeared later. Moreover, we found that even in the early stages, actors largely supported the neoliberal ideas and preferences. Eventually, market logic prevailed, and the focus moved to a flagship homeownership program named ‘Buyer’s Price’, that was advanced by a new minister, Moshe Kahlon. Journalists and the actors they cited not only sidestepped the rental program, but encouraged popular rentiership as the states’ best solution for renters.

Housing discourse, housing tenure and neoliberal ideology

Housing scholars have drawn on Foucault (Foucault, Citation1972; Gordon, Citation1980) to investigate discourse. They emphasize the relationships between discourse and power in the construction of residential reality and explain the different political ways in which discourse shapes the way society understands, controls, and organizes housing (Gurney, Citation1999; Hastings, Citation2000; Jacobs, Citation2006; Jacobs & Manzi, Citation1996, Citation2000; Jacobs et al., Citation2003).

These scholars have mostly analyzed policy papers and interviews. They identify power relations and underlying ideological frames by tracing discursive practices, dominances, gaps, side-stepping, inconsistencies, and the relationships to processes of societal change (Farhat, Citation2014; Harrison et al., Citation2004; Jacobs et al., Citation2022; Walker et al., Citation2020). Gurney (Citation1999), for example, studied how homeownership was constructed by powerful actors in Britain, who used discursive techniques to normalize homeownership and encourage individuals to pursue it through self-regulation and self-disciplining. He found that in policy papers, such actors connected the terms ‘homeownership’, ‘home’, ‘our future homes’, and ‘fair price’, while not connecting these terms to ‘housing’. In interviews, lay homeowners connected home and ownership, and identified homeownership with good citizenship, and as a ‘natural’ condition.

Other studies of housing discourse showed connections to the neoliberal ideology and the entailed policy preferences by tracing strategic uses of linguistic techniques and narratives, and the way actors advanced perceptions of the main housing problem, how to solve it, and whom it should benefit (Hastings, Citation2000; Jacobs et al., Citation2003; Jacobs & Manzi, Citation2014). The discursive connection between homeownership and neoliberal ideology was elaborated by Jacobs & Manzi (Citation2000; Jacobs, Citation2006; Jacobs et al., Citation2003), by revealing how actors in policy debates advanced a selective interpretation of a ‘housing problem’, with a preference for ownership.

Scholars also showed the formation of neoliberal discourse coalitions of government and market actors, that highlighted primarily cost, and the number or price of housing units, rather than peoples’ needs, experience and expectations (Williams et al., Citation2018). Jacobs et al. (Citation2022) also noted that actors rarely referred to the neoliberal ideology explicitly, and instead framed property interests as ‘shared values’, for example, while ignoring structural issues and the effect of the policies on less powerful people.

Discourse analysis has also been used to probe current rental issues and relationships, showing that neoliberal policy discourse often stigmatizes renters as irresponsible (Owen, 2016). Discourses even present renters as threatening the neighborhood’s safety and the physical state of the buildings and outdoor spaces (Jacobs et al., Citation2022; Watt, Citation2008). Scholars also show that contrary to this bias against renters, to support and promote of rentiership, discourses often portray owner-investors as savvy entrepreneurs (Brill & Durrant, Citation2021; Crook & Kemp, Citation2014; Verdouw, Citation2017).

Other recent studies interviewed young renters in the private market and showed that the dominance of neoliberal perspectives led them to feel insecure and have low self-esteem (McKee et al., Citation2017). Several studies analyzed media discourse and focused on renters and current programs aiming to aid them. They argued that although newspapers tended to legitimize state policies (Lux & Mikeszova, Citation2012; Vincze, Citation2019), they opposed social rental housing (Chang & Lee, Citation2020; Mee, Citation2017; Vincze, Citation2019). Finally, Bierre & Howden-Chapman (Citation2020) focused on the private rental market by analyzing renters’ narratives in New Zealand, and showed how renters’ limited power had negative impact on support for current policy efforts to aid them.

To these contemporary studies of rental discourses we contribute a focus on rental programs and processes that legitimate or delegitimate them in media discourses. In addition, these studies have failed to address ideological aspects. To narrow this gap, we ask how current Israeli media discourses reflect the conflict between the ideas of the rental programs and the neoliberal logic, and whether the actors challenge or maintain neoliberal ideas, policy factors and preferences. We follow Fairclough’s (Citation2003, Citation2013) methods of critical discourse analysis to study the news media.

Methodology

Fairclough (Citation2003, Citation2013) and other housing scholars (Jutel, Citation2011; Lavy et al., Citation2016; Rogers, Citation2014) analyzed how discourse connected actions, actors, groups, institutions and ideology. Fairclough’s ideas about critical discourse analysis continued Foucault’s approach but suggested more operative methods for investigating power and ideology in social or institutional settings (Elden & Crampton, Citation2016; Rogers, Citation2014). We used this method, and asked how various actors maintained or challenged the neoliberal ideology when discussing the rental program and related subjects. In line with the literature on neoliberal policies and policy discourses, we analyze how journalists and the actors they represented compared the program to owner-occupancy programs, their proposals for solving the housing problem and whom they should benefit. We also asked whether and how the discourses highlighted neoliberal preferences by analyzing the representation of the actors involved, including renters, and of the new rental projects, locations, institutions, policy ends, and target groups.

To contextualize the discourse and examine the rental program and the post-2011 housing reform in Israel, we collected and analyzed policy papers, political statements and relevant reports. Our data included all articles published by the leading Israeli print and online newspapersFootnote4 in the years between 2013 and 2018, when the government initiated new housing programs.Footnote5 We employed the main Israeli media-mining company (https://ifat.co.il) to digitally categorize publications according to dates and to program names. We found that the five leading Israeli print and online newspapers and two economic sections published 4,056 articles on housing programs in the said years, but only 5% (225) of these articles focused specifically on the rental program.

To fully examine the representation of rent themes, we also programed a specific computer script and used it combined with human tracing to scan the full data for the keyword ‘rent’ and its derivatives: ‘rental’, ‘renting’, ‘renters’, ‘lease’ and the ‘APRent’ company. Altogether, we found 715 articles that mentioned these keywords, including articles that focused on the rental programs and ones that focused on owner-occupancy housing schemes, specifically the flagship ‘Buyer’s Price’ program.

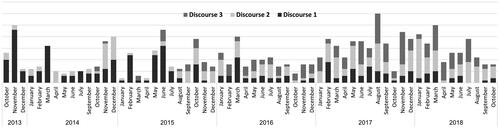

At this stage, we examined the main topics in the articles, asking about the context in which rental themes were discussed. We determined that there were three distinct discursive corpuses. Discourse 1: 257 articles discussed rental housing as a solution for a social problem, and focused on debates concerning rent policy as a viable state solution to the housing crisis. This discourse began in the first days of APRent, in 2013, and became less apparent after 2015, when Lapid was replaced as Finance Minister.

Discourse 2: 259 articles discussed realization of the rental housing policy and focused on the activity of APRent and the planning of new neighborhoods. This discourse began in 2013 and remained rather stable throughout the period. Discourse 3: 199 articles concerned owner-occupation housing programs, mainly ‘Buyer’s Price’, and related to rental issues in this context. This discourse appeared when the newly appointed Finance Minister Kahlon initiated the program in 2015, and became dominant in the following years (see ).

Following Fairclough (Citation2003), analysis of the three discourses used quantitative and qualitative methods to identify and rank the practices of representation for the actors. Fairclough suggested degrees of representation. The highest level is actual participation in a discourse, e.g. when certain actor (not a journalist) wrote an article. The second level of representation is giving voice to people through interviews or quotations. We identified this material quantitatively by tracing keywords such as ‘minister’, ‘official’, ‘renter’, ‘homeowner’, ‘developer’, ‘investor’, and measuring the relative share of a particular category out of all interviews or quotes. We then analyzed the actors’ rhetoric and statements qualitatively.

The final level is reference to specific actors. We traced references with the same keywords, used a similar quantitative method to evaluate dominant references, and analyzed this data qualitatively, asking how these actors were presented. For example, did a discourse portray certain actors as having an active or passive role? Were they referred to by name, with a picture, as a social category, or with a stigma? Lastly, we connected between the terms of representation and the neoliberal ideas and preferences. For example, we evaluated whether the discourse maintained the preference for homeownership and rentiership (French et al., Citation2011; Halbert & Attuyer, Citation2016) by comparing the representations of renters, homeowners or investors (Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Sager, Citation2013). Similarly, we analyzed the representation of non-human components such as policy topics, physical features, locations, institutions, arrangements, etc. To analyze whether and how actors maintained the neoliberal ideology in housing or challenged it, we traced their usages of a wide spectrum of keywords, including ‘dwellings’, ‘apartments’, ‘prices’, ‘contracts’, ‘standard’, and also names of specific areas and locations. We then probed quantitatively how these keywords were used in relation to certain actors, goals, market issues, policy issues, social issues, and procedures, and whether the discourse highlighted neoliberal ideas, factors and preferences, for example, by references to high-standard dwellings (Marcuse & Madden, Citation2016; Sager, Citation2013) or to market measurements (Aalbers, Citation2016; Nethercote, Citation2020).

Based on the literature on neoliberal policies and discourses above, shows our categories and keywords for the quantitative and qualitative analyses.

Table 1. Categories and key words for the analysis.

Context: israeli rental situation and reform

In Israel, about half of the residential buildings are condominiums, or apartment buildings, and the rest are detached houses and townhouses (Lotan & Soler, Citation2015).Footnote6 Older apartment buildings usually include 10-15 units on 3-8 stories, and many new towers have dozens of units (Margalit, Citation2021). Traditionally, providing housing was regarded as the state’s task (Alterman, Citation2005), and most of the programs included housing for sale (Schipper, Citation2015). Successive governments advanced wide homeownership, using centralized planning and land management. Early welfare-socialist governments constructed a large number of apartment buildings with subsidized units for sale, and with public units for impoverished immigrants, who rented on a long-term basis (Carmon, Citation1999). More recently, these mechanisms were again used on occasion to supply housing for immigrants or deal with housing crises.

Centralized land management continued throughout the neoliberal era, but the provision of housing and subsidies was privatized, and the construction of public units was minimized (Carmon, Citation1999). At the same time, many public units were sold to the renters, and the remaining units now account for only 2.5% of all the housing stock (Israeli State Comptroller, Citation2020). As the number of people living in poverty rose, the state aided those waiting for a public unit by paying part of their rent in the private market, according to criteria set by the Ministry of HousingFootnote7 (Hananel, Citation2017; Margalit, Citation2021).

Private rental is thus the main housing option open to these people, as well as to the growing number of poor people who are ineligible for public support, and middle-class people who cannot afford to buy. At the same time, this market is generally unregulated and functions in a uniquely strict laissez-faire manner (Schipper, Citation2015). For the most part, homeowners are private individuals who rent out their unit in shared ownership buildings. They can rent out for short or long periods, increase the price with no limitations, or demand additional and unlimited safety deposits. Demand is greater than supply, and renters have little protection against poor maintenance or eviction.

Following the 2011 housing protests, Lapid, who led a new centrist political party, made rental housing the focal point of his campaign. Similarly to other recent state interventions (Kemp, Citation2015; Martin et al., Citation2018), he aimed to incentivize institutional investors (e.g. pension and insurance companies) to participate in this effort. Lapid stated that his goal was to change the contract between the state and its citizens. First, by adding thousands of rental apartments, thereby changing the balance of power between renters and landlords. Second, by regulating long-term leases that would give stability to renters, including 20% of the units with reduced price (Margalit, Citation2021).Footnote8

When appointed Minister of Finance in March 2013, Lapid created APRent, a state body assigned to promote the rental program by ‘identifying land areas for development, promoting statutory planning, execution of property arrangements, management of development, managing the marketing to companies, monitoring and controlling of marketing tenders for rental housing complexes’ (Ministry of Finance, Israel, Citation2018). To achieve this, APRent was to create public-private ventures, in cooperation with institutional agencies, and then build 150,000 long-term rental apartments across the country. The incentive for the companies was a subsided lease of state land, allowing them to rent most (80%) of the units at market prices, and then to sell the apartments after fifteen years. The target group was middle-class households who did not own housing.

This initiative was followed by more rental reforms. A new national planning committee, VATMAL, was created to authorize the building of large housing projects quickly (Mualam, Citation2018), and include 30% long-term rental apartments in each project. Amendment 101 to the Planning and Building Law defined long-term rentals as a public need. The state set annual targets and incentivized Real Estate Investment Trust funds with tax deductions and additional building rights (Swirski & Dishon, Citation2016). Last, two young members of parliament (one, a former protest leader), promoted the Fair Rent Act aimed at limiting landlords’ ability to raise prices.

However, Lapid stayed in office less than two years, and after 2015, his successor, Moshe Kahlon, supported homeownership and sidelined the rental reform. His flagship program, ‘Buyer’s Price’, encouraged families to buy apartments at prices 20% lower than the market price nationwide (Friedman & Rosen, Citation2020). This program was also open to those who did not own housing, with no income test. Massive realization was mainly in peripheral cities. Although this was not the stated goal of the program, it encouraged rentiership by allowing people to purchase apartments and rent them out to others.Footnote9 This led people to become owner-investors – to invest in cheap apartments in peripheral cities, while continuing to live as renters in the center.

Along with the promotion of these property-led solution, years of political negotiation concluded with a thin version of the Fair Rent Act in 2017.Footnote10 APRent was implemented slowly. By July 2023, instead of the promised 150,000 apartments, the company reported that they had planned and sold land to developers for 16,000 apartments, of which only 2,562 were already occupied.Footnote11 The next sections review how newspapers covered the rental program’s intentions and their realization.

Newspaper coverage 2013-2018

Discourse 1. Rental reform and the israeli housing question

This discourse considered rental housing a solution for the housing crisis, mainly through the coverage of early policy decisions, minutes of government meetings and plans, and debates over the viability and legitimacy of promoting rental housing as part of the state’s actions to meet housing needs and demands.

The main actors represented in the articles were state politicians and officials (67% of all quotes). In particular, journalists quoted the successive Ministers of Finance, Yair Lapid and Moshe Kahlon. Both claimed that they were changing the existing social ‘contract’, but adopted a mixed approach that reflected welfarist as well as neoliberal ‘free-market’ ideas. Lapid attacked previous neoliberal governments for ‘betraying’ the citizens, announcing that ‘the depth of the crisis requires a profound change’, and promised that from now on, ‘middle-class young people will see that the state cares for them’ (Globes, Citation2014, media article). Kahlon blamed earlier governments for ‘enriching oligarchs’ (Dvir, Citation2015, media article). At the same time, both expressed neoliberal preferences: Lapid described the rental dwellings as luxurious units (see Fainstein, Citation2008; Margalit & Alfasi, Citation2016) ‘in high-standard high rises’ (Paz-Frenkel, Citation2013, media article), and urged large development companies to profit from APRent’s public-private projects (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2013; Tasan-Kok, Citation2008). Kahlon highlighted competition and thin bureaucracy (Charney, Citation2017; Harvey, Citation2013; Peck et al., Citation2013), claiming that the government should ‘let the market work’ (Milman, Citation2014, media article).

Journalists conducted the largest number of interviews (36%) with market actors (financiers, developers and real estate experts). Interestingly, such actors usually opposed the politicians’ market-led approach. In fact, some were clearly in favor of a more welfarist method and argued that the government should fund rental housing. A leading real-estate expert warned that by relying on private developers and financialization, the state ‘will soon have to subsidize rent for thousands of families’ (Tzion, Citation2013, media article).

Another debate between officials and other actors measured the rental program against the strong preference for homeownership in Israeli society. For example, the head of APRent objected to the idea that ‘renting is not part of Israeli mentality’ (Alfi, Citation2017, media article); a company lawyer added that ownership was not the most important aspect in housing; and the State Attorney stated, ‘with prices soaring, young couples can rent for long periods instead of taking out large mortgages’ (Tzion, Citation2016, media article). Against this, market and planning experts criticized the rental program for ignoring the prevailing preference for homeownership, and framed property interests as shared values (Jacobs et al., Citation2022). A major real-estate dealer stated that ‘the Israeli dream is to own an apartment’ (Castel, Citation2013, media article). Another stated that the rental program should not replace owner-occupancy housing schemes, which could ‘give the young generation some hope’ (Bousso, Citation2014, media article), and that the government should ‘stop abusing citizens with rent initiatives’, and not allow people to ‘spend all their money on rent’ (Tzion, Citation2014, media article). A leading planning expert explained that with APRent, some Israelis would not be able to ‘bequeath a house to their offspring’ (Tzuriel-Harari, Citation2017, media article).

While these debates exposed ideological tensions between the support of rental program and the preference for property ownership, the minor representation of renters clearly reflected the neoliberal avoidance of people who could not buy or invest (Marcuse & Madden, Citation2016). Journalists gave renters representation in only two interviews, one of which was with a couple who praised the program as ‘a dream come true’ (Damari, Citation2017, media article).

Moreover, renters were usually referred to as a general group, with no distinctions between their issues, and without addressing of their personal, local, socioeconomic or ethnic situations. In fact, renters were rarely mentioned as a distinct group (in only 8% of the references to actors), and were usually mentioned as part of broader sector, such as ‘young couples’, ‘citizens’, ‘students’ and ‘residents’ (together, 44%), or as members of official policy categories such as ‘eligible households’, ‘home-improvers’ and ‘non-owners’ (together, 26%). We also found stigmatic references. A municipal official, for example, used a familiar neoliberal stereotype against renters and rental housing environments (Jacobs et al., Citation2022; Owen, 2016; Watt, Citation2008), stating that ‘around the world, neighborhoods that were built entirely for rent deteriorated fast’ (Chudi, Citation2013, media article).

To summarize, this discourse conveyed a mixed message, both challenging and maintaining the neoliberal ideas and preferences. None of the actors took a coherent ideological stance. However, the weak representation of renters fully accorded with neoliberal discourses. Journalists gave them little voice. If they were represented at all, it was as part of larger social groups, without attention to their specific needs and condition.

Discourse 2. Realization and normalization

The 259 articles in this discourse focused on the realization of the rental reform, mainly through the establishment of APRent company, land bids, and plans for rental buildings in existing or new neighborhoods. This discourse also normalized rental living with visual and textual portraying of the target residents, locations and planned urban landscapes. Simultaneously, this discourse supported neoliberal ideas, free-market images and elitist preferences, and highlighted the state’s role in stabilizing and shaping the housing market.

With this state-market duality, references to ideology and the social contract were implicit in the manner of representation (Jacobs et al., Citation2022). First, renters were not represented at all. Second, journalists, and state politicians and market actors, who received the highest representation, only mentioned renters as part of broader social groups. The officials’ perspective was also traced in numerous articles that cited press releases announcing the initiation of a projects, with details on the bids, developers and state agencies involved, and the target group of residents. Third, in a manner typical of neoliberal discourses, these articles focused on efficiency (Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Peck et al., Citation2013; Sager, Citation2013), and highlighted numbers: prices, discounts, and land values, residential units, apartment sizes, height and number of buildings, etc. (see Williams et al., Citation2018). With this rhetoric, articles portrayed rental housing as an ongoing activity. Journalists often closed articles with a reassuring citing of a government figure, such as ‘we intend to reach our goal and build thousands of long-term rental units’ (Chudi, Citation2016, media article), or ‘we are confident that the best developers are interested in the projects’ (Bousso, Citation2016, media article).

These and other articles normalized rental living with clear neoliberal preferences for high-standard properties (Marcuse & Madden, Citation2016; Sager, Citation2013), fashionable housing blocs and neighborhoods (Boland et al., Citation2017; Hubbard, Citation2004), and prime locations (Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Sager, Citation2013). In this manner, they solidified a message of future environments that were the complete opposite of stigmatized urban rental pockets (Jacobs et al., Citation2022; Watt, Citation2008). The attractiveness of the program was also highlighted with verbal descriptions and architectural visualization of planned high-rises, with large terraces and expensive roof apartments (Fainstein, Citation2008; Margalit & Alfasi, Citation2016). Other texts and images presented new neighborhoods with trendy urbanity, large recreation areas, bicycle lanes, shops, and public buildings. Texts included quotations of officials describing how these images accorded with contemporary architectural and planning fashions. For example, the head of APRent stated, ‘we follow advanced urban planning and insist on mixed-use areas’ (Bousso, Citation2017, media article), or ‘we promote high standard buildings’ (Gazit, Citation2017, media article).

The discourse also expressed the neoliberal preference for affluent social groups and central locations (Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Sager, Citation2013). For example, a mayor was quoted as saying that rental housing would help brand their cities with ‘especially high urban qualities’ (Chudi, Citation2018, media article). The discourses also conflated renters and people who could purchase housing. Actors referred to the target group of renters as ‘young couples’ from the middle class, and the head of APRent went further and described the renters as dynamic and cosmopolitan professionals who moved easily between world cities: ‘today, I am here; tomorrow, I’m in New York’ (Darel, Citation2015, media article).

Other actors focused on prime locations, or ‘demand areas’. Although many of the projects were built outside Israel’s geographic center,Footnote12 centrality was highlighted by politicians and bureaucrats, mayors, and city council members. Kahlon linked between such locations, renting and individual choice (Kern, Citation2010), by stating that ‘long- term renting will be the answer for people who cannot, or do not want to buy apartment, but still wish to live in areas of demand’ (Gazit, Citation2017, media article).

Unlike Discourse 1, in Discourse 2 financiers and developers mostly endorsed the officials’ statements. They praised the projects and related to dwellings as assets (Sager, Citation2013), by promising ‘to plan, construct, finance and manage the assets’ (Chudi, Citation2017, media article). One developer stated that ‘the project provides a real solution for anyone looking for quality housing… in a central location, close to employment areas and at affordable prices’ (Tzion, Citation2017, media article).

To summarize, in this discourse there were no meaningful debates, and while renters were not given voice at all, all the other actors promoted a similar vision, which clearly reflected known neoliberal policy preferences. The realization and normalization of the rental program were not presented as alternatives to the prevailing housing order, but rather in line with market-led images. The articles highlighted market prospects and efficiency, and painted a picture of rental housing that was completely opposed to the stigma against them. The target group of renters was portrayed not only as identical to homeowners, but as a globalized elite free to choose whether to buy or rent.

Discourse 3: from renting to rentiership

This discourse consists of 199 articles that clearly supported the neoliberal view of housing as asset. The articles dealt with rental issues in relation to the ‘Buyer’s Price’ program that advanced ownership and rentiership. This discourse constituted a small fraction of the full media coverage of ‘Buyer’s Price’ (2,385 articles). Nevertheless, in 2017-18, it became dominant and overshadowed Discourses 1 and 2. It largely highlighted property interests as shared values (Jacobs et al., Citation2022), and a new image of renters as savvy entrepreneurs (Crook & Kemp, Citation2014).

‘Buyer’s Price’ was unprecedent in both scope and scale. The risk in the program’s encouragement of popular rentiership was explained in the media with a report by the Israeli Central Bank (Citation2017), which argued that the allowing buyers to rent out their properties will lead many to take advantage of the subsidized prices, invest and become owner-investors in peripheral locations. This conduct, the report stated, would ‘flood’ the rental housing stock in these locations, prices would fall, and the actual rent payments will dash ‘the investors’ plans and calculations’ (Meirovsky, Citation2018, media article).

Some developers and financiers expressed other concerns, stating for example that ‘people invest because they wish to get out of the rental cycle, but as they cannot buy where they want to live, they will be forced to continue renting for many years’ (Lan, Citation2016, media article). One developer accused the Ministry of Finance of not caring whether these people ‘understand the risk’ (Snir, Citation2016, media article). Yet mostly, such actors (35% of citations and 31% of interviews), expressed a preference for homeownership and investment and praised the governments’ goal of helping people break free of the ‘rental cycle’.

State officials and politicians (49% of the citations) responded to the critiques by reiterating the neoliberal objective to ‘accentuate individuals’ responsibility for their own living conditions’ (Sager, Citation2013, xxvii). For example, Kahlon stated: ‘I support social mobility and do not check what specific buyers do with their apartments’ (Rabd & Tzion, Citation2016, media article). His consultant highlighted the opportunity given ‘to obtain real estate at a below market price. You may buy an apartment, rent it out and use the money to rent elsewhere’ (Tzion, Citation2016, media article). Another official added, ‘we do not aim to educate people… people are smart and can make their own choices. In a free market anyone can decide to buy apartment and rent it out’ (Chudi, Citation2017, media article).

For the first time, the representation of renters became prominent, but it highlighted the ones who decided to take advantage of the plan and become owner-investors. Journalists described these people as active, entrepreneurial individuals (Brill & Durrant, Citation2021; Crook & Kemp, Citation2014; Verdouw, Citation2017), and mentioned them much more frequently than they did ‘regular’ renters (25% vs. 3% of references to actors). These representations were positive and often personal, including the new investors’ names and pictures. Indeed, 39% of all interviews with actors were with such investors, and they described their plan ‘to rent out the apartment ‘(Levi, Citation2016, media article). Most of these people also described their own hardships as renters; for example, ‘the high rent left us with no money’ (Rimerman, Citation2018, media article), or ‘we work hard and spend most of our earnings on rent… all we ever wanted is to own an apartment’ (Melinizky, Citation2018, media article).

Some also maintained the neoliberal preference for central locations (Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Sager, Citation2013). They explained that the location offered by the program was relevant only because it enabled them to buy an apartment: ‘I didn’t see the neighborhood, I wouldn’t live in it anyway’ (Melinizky, Citation2018a, media article); ‘I didn’t even visit there, as I don’t mean to live there,’ or ‘I never meant to live in the apartment… Yet we believe that by renting out and then selling the flat we will justify the investment’ (media article 30).

The high representation of owner-investors highlighted the neoliberal logic of housing as an asset and portrayed rentiership as the optimal fulfillment of the state’s responsibility for young citizens. With this shift this discourse aimed to reconcile the tensions between renting and neoliberal ideology by highlighting rentiership as the ‘new way to go’. As our analyses showed, this development settled the conflicts between welfarist and neoliberal ideas found in Discourse 1, and departed from the more implicit attachment to the later ideology found in Discourses 2.

Conclusion

In this paper, we focused on a legitimation process of a current Israeli program designed to assist renters, and asked how this process was affected by the prevailing neoliberal ideology. In line with perspectives viewing mass media as a key arena for policy legitimation or evasion (Fairclough, Citation2003; Jacobs & Manzi, Citation2000; Murphy, Citation2016), we analyzed how major Israeli newspapers covered the program and other rental-related issues. Drawing on the literature on neoliberal housing policies and discourses, we identified the main policy ideas, factors and preferences, and the main ideological tensions regarding the state’s rental programs. Applying the methodological ideas of critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, Citation2003, Citation2013), we looked for signs of these tensions in the discourses, and examined whether the representation of actors and locations and of social, spatial and physical themes maintained or challenged prevailing neoliberal housing ideas, policy factors and preferences.

We identified three corpuses of articles that covered the policy process. The first, which emerged early in 2013, focused on debates around the viability of rent policy as a state solution mediating between state, market, and professional actors. The second corpus centered on the implementation of the program. The third addressed rental issues in owner-occupation housing programs. This discourse emerged in response to the initiation of the flagship program ‘Buyer’s Price’ in 2015, and remained dominant in subsequent years.

In our analysis of the debates in the first discourse, we observed a tension between voices supporting a welfarist promotion of the rental programs and others presenting strong preferences for homeownership, as well as a conflict between support of state involvement and free-market priorities. We also found that despite these differences, actors largely followed neoliberal preferences. In the second discourse, market-led preferences were evident in the actors’ vision of the planned rental housing. Such preferences were boldly advanced in the third, later discourse, which not only sidestepped the rental program, but encouraged popular rentiership, and described it as the state’s best solution for young people.

Through comprehensive quantitative and qualitative discourse analysis, our research reveals a noteworthy pattern across all discourses. As in other neoliberal discourses (Brill & Durrant, Citation2021; Crook & Kemp, Citation2014; Verdouw, Citation2017), renters’ voices were seldom heard, while a significant focus was placed on strong state and market actors. Our research contributes to understanding how renters’ perspectives are inadequately represented in current dominant discourses, while homeownership is often portrayed more favorably as a desirable aspiration. These findings underscore the need to address the imbalances in representation and discourse surrounding housing policies and to consider the implications for renters in contemporary homeowner societies.

Mirroring the criteria outlined in studies of neoliberal housing policies, we found more lines of affinity with this ideology, and with the factors and preferences it entailed. News articles ignored structural issues and constraints (Marcuse & Madden, Citation2016; Sager, Citation2013), and depicted renting as a free choice for young people. The portrayal of rental housing solidified an image of future environments that strongly contradicted the stigmatized image of urban rental pockets (Jacobs et al., Citation2022; Watt, Citation2008). Articles described fashionable housing estates (Boland et al., Citation2017; Fainstein, Citation2008; Hubbard, Citation2004; Margalit & Alfasi, Citation2016), in prime locations, with affluent, ‘free’, and ‘responsible’ residents (Harvey, Citation2005, Citation2013; Sager, Citation2013). In keeping with neoliberal and financialization narratives, actors mainly spoke of dwellings as assets (Sager, Citation2013), and prioritized public-private projects (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2013; Tasan-Kok, Citation2008), market competition and thin bureaucracy (Charney, Citation2017; Harvey, Citation2013; Peck et al., Citation2013).

We wish to argue that the apparent ideological tension, or conflict, between the aims of advancing rental reform and neoliberal ideology, was merely superficial. The tension resolved itself quickly, as the media continued to report on homeownership and rentiership as the best solution. Based on these findings, we contend that ideology and its deep influences are a crucial aspect for understanding current legitimation processes of rental housing, and that the expansion in renting calls for a profound examination of the ideological beliefs underlying current discourses and activities.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Israeli Science Foundation for the generous support, and the editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Talia Margalit

Talia Margalit, B. Arch, PhD, Associate Professor and the head of the David Azrieli School of Architecture in Tel Aviv University. Her research focuses on equality and democracy in housing and urban planning. She completed wide angle funded researches on Planning objections and justifications and on Media coverage of Israeli planning and housing, and now leading a cutting edge research on Knowledge in Israeli Planning. She authored several book chapters and published in the journals Urban Studies, Environment and Planning A, Cities, Planning Theory and Practice, Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Land Use Policy, Geoforum, Sustainabilty, among others. She and her students founded ‘Me’irim’- an Israeli on-line NGO for planning democracy and communication.

Dikla Yizhar

Dikla Yizhar, B. Arch, M.sc, PhD, Architect and researcher. Her research focuses on the socio-cultural aspects of housing policies and residential architecture. Dikla is a lecturer in the Azrieli School of Architecture, Tel Aviv University, and in the Faculty of Architecture in the Tecnion (IIT), where she teaches courses in the fields of housing, design thinking, and planning.

Notes

1 Moderate expansion was evidenced in South European countries (Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal), and minimal expansion in Norway, Belgium and France (Crook and Kemp, Citation2014; Whitehead et al., Citation2012; Hochstenbach and Ronald, Citation2020).

2 The share of private renters is highest, 53%, in Tel Aviv-Jaffa (Tel-Aviv-Jaffa Municipality, Citation2021).

3 https://www.aprent.co.il/(last entered 31.7.2023).

4 The sources we used were two daily newspapers, Haaretz (including the economics section, The Marker) and Yedioth Ahronoth (including the economics section, Calcalist) and one daily newspaper devoted to economics, Globes. All are published online and in print. We also used two popular Internet portals, YNET/XNET and WALLA.

5 Policy papers, political statements, and the relevant reports, as well as the media data were all published in Hebrew. We conducted the analysis in the same language. We translated to English for the purpose of this article.

6 The State of Israel does not collect data regarding housing typologies.

7 The criteria for receiving the payments are maximizing earning capacity, receiving welfare payments, and according to sources of income, family size, disability, age, new immigrants, victims of violence, Holocaust survivors and released prisoners. https://www.gov.il/he/departments/guides/rental_assistance_step_by_step.

8 Prime Minister’s office, Decision 547 DR\13, 14/07/2013 https://www.gov.il/he/departments/policies/2013_govdes547,

The Israel Land Authority’s decisions: https://www.gov.il/he/departments/policies/rami_decisions.

9 The Ministry of Housing- rental apartments https://www.gov.il/he/departments/general/housing_for_rent_rules.

12 https://www.aprent.co.il/(20.7.2023).

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2016) The Financialization of Housing: A Political Economy Approach (New York: Routledge).

- Adkins, L., Cooper, M. & Konings, M. (2021) Class in the 21st century: Asset inflation and the new logic of inequality, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53, pp. 548–572.

- Allmendinger, P. & Haughton, G. (2013) “The evolution and trajectories of english spatial governance: ‘neoliberal’ episodes in planning”, Planning Practice and Research, 28, pp. 6–26.

- Alfasi, N. & Fenster, T. (2014) Between socio-spatial and urban justice: Rawls’ principles of justice in the 2011 israeli protest movement, Planning Theory, 13, pp. 407–427.

- Alterman, R. (2005) Planning in the face of crisis: Land use, housing, and mass immigration in Israel (New York: Routledge).

- Arundel, R. & Doling, J. (2017) The end of mass homeownership? Changes in labour markets and housing tenure opportunities across Europe, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment: HBE, 32, pp. 649–672.

- Bierre, S. & Howden-Chapman, P. (2020) Telling stories: the role of narratives in rental housing policy change in New Zealand, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 29–49.

- Birch, K. & Ward, C. (2023) Introduction: Critical approaches to rentiership, EPA: Economy and Space, pp. 1–9.

- Boland, P., Bronte, J. & Muir, J. (2017) On the waterfront: Neoliberal urbanism and the politics of public benefit, Cities, 61, pp. 117–127.

- Bone, J. (2014) Neoliberal nomads: Housing insecurity and the revival of private renting in the UK, Sociological Research Online, 19, pp. 1–14.

- Brenner, N., Peck, J. & Theodore, N. (2010) Variegated neoliberalization: Geographies, modalities, pathways, Global Networks, 10, pp. 182–222.

- Brill, F. & Durrant, D. (2021) The emergence of a build to rent model: the role of narratives and discourses, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53, pp. 1140–1157.

- Carmon, N. (1999) Housing policy in Israel: The first 50 years. Public Policy in Israel (Tel-Aviv: Am Oved). (Hebrew)

- Chang, K. K. & Lee, T. T. (2020) The frame of the house: How elite news sources framed taiwan’s housing policy, Newspaper Research Journal, 41, pp. 88–116.

- Charney, I. (2017) A “supertanker” against bureaucracy in the wake of a housing crisis: neoliberalizing planning in netanyahu’s Israel, Antipode, 49, pp. 1223–1243.

- Crook, T., & Kemp, P. A. (Eds) (2014) Private rental housing: Comparative perspectives. (Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing).

- Dodson, J. (2007) Government discourse and housing (Hampshire and Burlington: Ashgate Publishing).

- Elden, S. & Crampton, J. (2016) Introduction, in: J. Crampton & S. Elden (Eds) Space, knowledge and power: Foucault and geography, pp. 1–16 (New York: Routledge).

- Fainstein, S. (2008) Mega-projects in New York, london and ‘amsterdam, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, pp. 768–785.

- Fairclough, N. (2003) Analysing Discourse, Textual analysis for social research (London and NY: Routledge).

- Fairclough, N. (2013) Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language (London and NY: Routledge).

- Farhat, R. (2014) Progressive planning, biased discourse, and critique: an agentic perspective, Planning Theory, 13, pp. 82–98.

- Forrest, R. & Hirayama, Y. (2009) The uneven impact of neoliberalism on housing opportunities, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33, pp. 998–1013.

- Forrest, R. & Hirayama, Y. (2015) The financialisation of the social project: Embedded liberalism, neoliberalism and home ownership, Urban Studies, 52, pp. 233–244.

- Foucault, M. (1972) The archaeology of knowledge & the discourse on language (New York: Pantheon Books).

- French, S., Leyshon, A. & Wainwright, T. (2011) Financializing space, spacing financialization, Progress in Human Geography, 35, pp. 798–819.

- Friedman, R. & Rosen, G. (2020) The face of affordable housing in a neoliberal paradigm, Urban Studies, 57, pp. 959–975.

- Fuchs, C. (2009) Grounding critical communication studies: an enquiry into the communication theory of karl marx, Journal of Communication Inquiry, 34, pp. 15–41.

- Gordon, C. (1980) Michelle Foucault, Power/Knowledge: selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977, in: C. Gordon (Ed) (New York: Pantheon Books).

- Gurney, C. M. (1999) Pride and prejudice: Discourses of normalisation in public and private accounts of home ownership, Housing Studies, 14, pp. 163–183.

- Halbert, L. & Attuyer, K. (2016) Introduction: the financialisation of urban production: Conditions, mediations and transformations, Urban Studies, 53, pp. 1347–1361.

- Hananel, R. (2017) From Central to marginal: the trajectory of israel’s public-housing policy, Urban Studies, 54, pp. 2432–2447.

- Harrison, C. M., Munton, R. J. & Collins, K. (2004) Experimental discursive spaces: policy processes, public participation and the greater London authority, Urban Studies, 41, pp. 903–917.

- Harvey, D. (2005) A brief history of neoliberalism (Oxford: University Press).

- Harvey, D. (2013) Rebel cities: From the right to the city to the urban revolution (London and NY: Verso).

- Hastings, A. (2000) Discourse analysis: what does it offer housing studies?, Housing, Theory and Society, 17, pp. 131–139.

- Hochstenbach, C. & Ronald, R. (2020) The unlikely revival of private renting in amsterdam: Re-regulating a regulated housing market, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52, pp. 1622–1642.

- Hubbard, P. (2004) Revenge and injustice in the neoliberal city: Uncovering masculinist agendas, Antipode, 36, pp. 665–686.

- Hulse, K., & Yates, J. (2017) A private rental sector paradox: Unpacking the effects of urban restructuring on housing market dynamics, Housing Studies, 32(3), pp. 253–270.

- Hulse, K., Morris, A. & Pawson, H. (2019) Private renting in a home-owning society: Disaster, diversity or deviance?, Housing, Theory and Society, 36, pp. 167–188.

- Israeli Central Bank (2017) Yearly Report 2016. https://www.boi.org.il/he/NewsAndPublications/RegularPublications/DocLib3/BankIsraelAnnualReport/%D7%93%D7%95%D7%97%20%D7%91%D7%A0%D7%A7%20%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%A8%D7%90%D7%9C%202016/full2016.pdf (Hebrew)

- Israeli State Comptroller (2020) Report on the Ministry of Housing - Government program ‘Buyer’s Price’. http://www.mevaker.gov.il/sites/DigitalLibrary/Documents/2020/70a/204-mehir-lamishtaken-Full.docx (Hebrew)

- Jacobs, K. (2006) Discourse analysis and its utility for urban policy research, Urban Policy and Research, 24, pp. 39–52.

- Jacobs, K., Atkinson, R. & Warr, D. (2022) Political economy perspectives and their relevance for contemporary housing studies, Housing Studies, 39, pp. 962–979.

- Jacobs, K. & Manzi, T. (1996) Discourse and policy change: the significance of language for housing research, Housing Studies, 11, pp. 543–560.

- Jacobs, K. & Manzi, T. (2000) Evaluating the social constructionist paradigm in housing research, Housing, Theory and Society, 17, pp. 35–42.

- Jacobs, K., Kemeny, J. & Manzi, T. (2003) Power, discursive space and institutional practices in the construction of housing problems, Housing Studies, 18, pp. 429–446.

- Jacobs, K. & Manzi, T. (2014) Investigating the new landscapes of welfare: Housing policy, politics and the emerging research agenda, Housing, Theory and Society, 31, pp. 213–227.

- Jutel, O. (2011) ‘The way of the world’, Neo-Liberal discourse, the media and fisher & paykel’s offshore relocation. Communication, Politics & Culture, 44, pp. 78–91.

- Kemp, P. A. (2015) Private renting after the global financial crisis, Housing Studies, 30, pp. 601–620.

- Kern, L. (2010) Gendering reurbanisation: Women and new‐build gentrification in toronto, Population, Space and Place, 16, pp. 363–379.

- Kohl, S. (2018) More mortgages, more homes? The effect of housing financialization on homeownership in historical perspective, Politics & Society, 46, pp. 177–203.

- Lavy, B. L., Dascher, E. D. & Hagelman, R. R.III, (2016) Media portrayal of gentrification and redevelopment on rainey street in austin, Texas (USA), 2000–2014, City, Culture and Society, 7, pp. 197–207.

- Lotan, N. & Soler, S. (2015) Residential building patterns in Israel. (Jerusalem: Ministry of the Environment). (Hebrew)

- Lux, M. & Mikeszova, M. (2012) Property restitution and private rental housing in transition: the case of the Czech Republic, Housing Studies, 27, pp. 77–96.

- Marcuse, P. & Madden, D. (2016) In defense of housing: The politics of crisis (London, NY: Verso).

- Margalit, T. & Alfasi, N. (2016) The undercurrents of entrepreneurial development: Impressions from a globalizing city, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48, pp. 1967–1987.

- Margalit, T. (2021) A significant silence: Single mothers and the current israeli housing discourse, Geoforum, 122, pp. 129–139.

- Martin, C., Hulse, K. & Pawson, H. (2018) The changing institutions of private rental housing: an international review, AHURI Final Report No. 292 Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

- McKee, K., Moore, T., Soaita, A. & Crawford, J. (2017) Generation rent and the fallacy of choice, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, pp. 318–333.

- Mee, K. J. (2017) Necessary welfare measure or policy failure: media reports of public housing in Sydney in the 1990s, in: K. Jacobs, J. Kemeny & T. Manzi (Eds) Social constructionism in housing research, pp. 117–141 (New York: Routledge).

- Ministry of Finance, Israel (2018) About the National Housing Headquarters. https://www.gov.il/he/departments/general/rent_apartment (Hebrew)

- Mualam, N. (2018) Playing with supertankers: Centralization in land use planning in Israel—a national experiment underway, Land Use Policy, 75, pp. 269–283.

- Munro, M. (2018) House price inflation in the news: a critical discourse analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK, Housing Studies, 33, pp. 1085–1105.

- Murphy, L. (2016) The politics of land supply and affordable housing: Auckland’s housing accord and special housing areas, Urban Studies, 53, pp. 2530–2547.

- Murphy, L. (2020) Neoliberal social housing policies, market logics and social rented housing reforms in New Zealand, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 229–251.

- Nethercote, M. (2020) Build-to-rent and the financialization of rental housing: future research directions, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 839–874.

- Owen, D. (2016) “Hillbillies”, “Welfare Queens”, and “Teen Moms”: American Media’s Class Distinctions. In S. Lemke, W. Schniedermann (Eds) Class divisions in serial television, pp. 47–63 (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Peck, J., Theodore, N. & Brenner, N. (2013) Neoliberal urbanism redux?, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37, pp. 1091–1099.

- Powell, R. (2015) Housing benefit reform and the private rented sector in the UK: on the deleterious effects of short-term, ideological “knowledge”, Housing, Theory and Society, 32, pp. 320–345.

- Raz-Dror, O. (2019) Shift in rent prices during israeli housing crises 2008–2015, Israeli State Bank Survey, 90, pp. 39–84. (Hebrew).

- Rogers, D. (2014) The sydney metropolitan strategy as a zoning technology: analyzing the spatial and temporal dimensions of obsolescence, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32, pp. 108–127.

- Ronald, R. (2004) Home ownership, ideology and diversity: Re‐evaluating concepts of housing ideology in the case of Japan, Housing, Theory and Society, 21, pp. 49–64.

- Ronald, R. (2008) The ideology of home ownership: Homeowner societies and the role of housing (New York: Springer).

- Sager, T. (2013) Reviving critical planning theory: Dealing with pressure, neo-liberalism, and responsibility in communicative planning (London: Routledge).

- Schipper, S. (2015) Towards a ‘post‐neoliberal’ mode of housing regulation? The israeli social protest of summer 2011, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39, pp. 1137–1154.

- Swirski, S. & Dishon, Y. (2016) The Split Housing Market: Market Forces, the Housing Crisis, and the Forgotten Vision (Jerusalem: Adva Center).

- Tasan-Kok, T. (2008) Changing interpretations of ‘flexibility’ in the planning literature: from opportunism to creativity?, International Planning Studies, 13, pp. 183–195.

- Tel-Aviv-Jaffa Municipality (2021) Statistical Yearbook. https://www.tel-aviv.gov.il/Transparency/Pages/Year.aspx. (Hebrew)

- Verdouw, J. J. (2017) The subject who thinks economically? Comparative money subjectivities in neoliberal context, Journal of Sociology, 53, pp. 523–540.

- Vincze, H. O. (2019) Segregated housing areas and the discursive construction of segregation in the news, in: Racialized Labour in Romania: Spaces of Marginality at the Periphery of Global Capitalism, pp. 145–178 (Springer).

- Walker, H. M., Reed, M. G. & Fletcher, A. J. (2020) Wildfire in the news media: an intersectional critical frame analysis, Geoforum, 114, pp. 128–137.

- Watt, P. (2008) ‘Underclass’ and ‘ordinary people’ discourses: Representing/re-presenting council tenants in a housing campaign, Critical Discourse Studies, 5, pp. 345–357.

- Whitehead, C., Monk, S., Scanlon, K., Markkanen, S. & Tang, C. (2012) The private rented sector in the new century: a comparative approach (Copenhagen: Boligokonimisk Videncenter).

- Williams, G., Omankuttan, U. Devika, J. & Aasen, B. (2018) Enacting participatory, gender-sensitive slum redevelopment? Urban governance, power and participation in Trivandrum, Kerala, Geoforum, 96, pp. 150–159.

- Winke, T. (2021) Housing affordability sets us apart: the effect of rising housing prices on relocation behavior, Urban Studies, 58, pp. 2389–2404.

Media articles

- Alfi, S. (2017) Long term rental? Expectations should be lowered, Globes May 5.

- Bousso, N. (2014) New goal for APRent: construction of 2,000 apartments with an investment of 2 billion NIS, TheMarker November 3.

- Bousso, N. (2016) ‘Azorim’ will build a project of 180 apartments for long-term rental, TheMarker December 25.

- Bousso, N. (2017) Residential towers for rent? The municipality prefers businesses, TheMarker August 22.

- Castel, G. (2013) Lapid’s housing plan will not work, Walla October 10.

- Chudi, U. (2013) Head of Lapid authorities: “90-day delay of the recommendations”, Globes November 13.

- Chudi, U. (2016) Progress in projects for long-term rental in Tel Aviv, Globes July 6.

- Chudi, U. (2017) ‘Ashstrom’ won the ‘apartment for rent’ bid in Tel Aviv”, Globes May 14.

- Chudi, U. (2017) The bid of ‘Apartment for rent’ and the Israeli Land Authority in Jerusalem was concluded, Globes August 8.

- Chudi, U. (2018) Reverse effect: buyers became investors, Globes March 19.

- Damari, H. (2017) Apartment for Rent, Ynet March 17.

- Darel, Y. (2015) “I am responsible for the action, not for the promises”, Calcalist May 7.

- Dvir, N. (2015) Kahlons’ Housing Program: All responsibilities in one office, Ynet, February 11.

- Gazit, A. (2017) Apartment for Rent and the Israeli Land Authority published bids for 561 apartments, Calcalist August 31.

- Globes (2014) Lapid: “My goal is that young couple will be able to afford an apartment”, Globes October 24.

- Lan, S. (2016) “They push people to become investors and stay in the rental market”, Calcalist November 5.

- Levi, H. (2016) Many of the winners of Buyer’s Price’ bids do not intend to live in the apartments at all? TheMarker July 15.

- Meirovsky, A. (2018) Kahlon’s logic: no reduce in housing prices? We will replace the head of the Bank, TheMarker, March 29.

- Melinizky, G. (2018) There is no need and demand for rental projects outside Tel Aviv area, TheMarker March 30.

- Melinizky, G. (2018a) “I haven’t seen the neighborhood - I won’t live there anyway”: stories of the Buyer’s Price winners, TheMarker August 5.

- Milman, O. (2014) Kahlon: “Lapid’s program will widen social gaps”, Calcalist June 9.

- Paz-Frenkel, E. (2013) Lapid to developers: “to solve the housing crisis - we are ready to lose money in land marketing,” Calcalist 16 December.

- Rabd, A. & Tzion, H. (2016) “A bid for 460 affordable flats near Haifa, Ynet, November 1

- Rimerman, R. (2018) Stay or give up? Buyer’s Price and household’s dilemma, Ynet January 16.

- Snir, A. (2016) The ministry of finance creates new real-estate investors, TheMarker October 28.

- Tzion, H. (2013) The 90-day team can be the 90-minute team, Ynet November 18.

- Tzion, H. (2014) “2,000 apartments for rent in two years? Not practical”, Ynet November 19.

- Tzion, H. (2016) “All over the world couples can rent a long-term apartment”, Ynet January 18.

- Tzion, H. (2016) The ministry of finance wants you to hurry and register to Buyer’s Price, Ynet August 18.

- Tzion, H. (2017) The bid for affordable long-term rentals was concluded: how many households won? Walla May 5.

- Tzuriel-Harari, K. (2017) Prof. Rachel Alterman: “The worst residential neighborhoods that the state planned look like ectopic pregnancy”, Calcalist October 4.