Abstract

This research is the first to examine the consequences of international migration for housing tenure through comparisons between the ‘settler’ migrants who originated from Turkey and are now living in multiple European destinations and their ‘stayer’ and ‘returnee’ counterparts based in Turkey. The data is drawn from personal interviews performed as part of the pioneering 2000 Families Survey with 5980 individuals nested within 1770 families. The settlers differ considerably from their stayer and returnee counterparts in that they turn more towards tenancy than homeownership in their current country of residence in Europe. Strikingly, the results reveal that the least integrated reside in countries governed by liberal expansion regime (esp. Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands), promoting policy measures to ease transition of lower social classes into homeownership. The results also demonstrate an increased tendency for homeownership amongst the children of asset-rich parents across both Turkey and Europe, independently of migration status.

Introduction

There has been a long-standing research interest in understanding the key influences upon housing tenure patterns observed in Europe and beyond (Bayrakdar et al., Citation2019; Lennartz et al., Citation2016; Mulder & Wagner, Citation1998; Ronald, Citation2008). In the face of rising housing costs and people’s declining ability to afford decent housing for various reasons, including increased precarity and reduced social support, housing has become an important player in growing socio-economic inequalities (Arundel, Citation2017). Despite this, its outcomes for international migrants and their descendants have attracted little research attention. Of the few existing studies, some are destination-based, involving comparisons between migrants and the ‘natives’ (Constant et al., Citation2009; Sinning, Citation2010; Magnusson Turner & Hedman, Citation2014). Others are origin-based, descriptively comparing the homeownership status of return migrants with those who remained in the origin country (Zeyneloğlu & Sirkeci, Citation2014). None of these studies explicitly link migration origins to destinations.

The present study aims to close this research lacunae. It is the first to examine housing tenure patterns through multi-sited comparisons drawn between ‘settler’ migrants from three family generations who moved from Turkey to various destination countries in Europe and their ‘stayer’ and ‘returnee’ counterparts currently residing in Turkey. From this unique multi-site and intergenerational perspective, it specifically investigates the following questions:

To what extent do the housing tenure outcomes differ for the ‘settler’ and return migrants and their ‘stayer’ counterparts?

Do the outcomes vary amongst the ‘settlers’ who moved into different housing regimes in Europe?

How far and in what ways do parental assets contribute to the housing tenure status of their children?

Does the influence of parental assets differ between the ‘settler’ and return migrants and their ‘stayer’ counterparts?

Thereby, our research sheds rare light upon the role played by migration and intergenerational transfers in shaping housing tenure patterns in the origin and destination countries.

The article is organised as follows. The next section provides a broad-brush overview of the relevant empirical works. This is followed by a short description of the housing systems prevalent in Turkey and the European destinations. It then turns to present our theoretical perspective, along with the research hypotheses, methods and findings. This is followed by an interpretation of the results. The article concludes by addressing the research limitations and their implications for future research.

An overview of the relevant literature

The bulk of the existing literature on housing tenure focuses on understanding its determinants (see e.g., Coulter, Citation2023 for a more detailed review). Of particular relevance here is the work of Mulder & Wagner (Citation1998) who argue that the decision of homeownership is shaped by a) the perceived relative costs and benefits of homeownership and b) the individual’s resources and capacity to cover the costs attached to it. The literature draws attention to a range of factors from individual to local and national levels that enhance or restrain people’s capacity to navigate through these costs and benefits. At the individual level, socio-economic factors such as having a high income, secure employment and financial assets are shown to play an important role (Mulder & Wagner, Citation1998). Others emphasise the importance of family background in determining housing tenure patterns, particularly for young adults who are operating within an inflated housing market and insecure labour market conditions (Coulter, Citation2018; McKee, Citation2012). It is found that intra-generational inequalities remain strong, and people from financially more advantaged parental backgrounds achieve housing outcomes almost as good as previous generations whilst those from disadvantaged backgrounds often find themselves in less stable housing tenures and lower quality accommodation (Coulter et al., Citation2020).

Demographic factors such as age, marital status and household size are also shown to matter. The likelihood of homeownership is reported to increase with age, marriage and having children (Clark et al., Citation1997; Kulu & Steele, Citation2013). Such factors are argued to be linked to life course stage, or more specifically, major life-course events or the anticipation of such events (Bayrakdar et al., Citation2019; Mulder & Lauster, Citation2010). Further individual-level factors are linked to family values and socialisation. It is, for example, argued that individuals who come from homeowner families are socialised into a culture of homeownership and more likely to aspire to become a homeowner (Lersch & Luijkx, Citation2015; Nethercote, Citation2019).

At the more local and national levels, the quality and quantity of the housing stock are demonstrated to play a central role in shaping an individual’s ability to make housing decisions (Hochstenbach & Arundel, Citation2021; Lerbs & Oberst, Citation2014). The state of the housing markets, housing policies and cultural norms are also reported as key (Dewilde, Citation2017; Kemeny, Citation2006; McKee et al., Citation2017), along with the availability of state housing support (Doling & Ronald, Citation2010; McKee, Citation2012).

Studies that examine housing tenure patterns within the context of international migration are scarce. The existing literature lacks multi-sited comparisons between migrants and stayers; yet there are recent longitudinal studies tracking the housing trajectories of EU migrant workers who moved to another EU destination (Loomans, Citation2023; Manting et al., Citation2022), alongside others which compare one or more migrant groups with their ‘native’ counterparts (Constant et al., Citation2009; Haan, Citation2007; Kauppinen & Vilkama, Citation2016; Sinning, Citation2010; Zorlu et al., Citation2014). The emerging evidence indicates a propensity for migrants to have higher aspirations to become homeowners (Davidov & Weick, Citation2011). This tendency is attributed to the housing culture of the origin country (Özüekren & Van Kempen, Citation2002) and to the migrants’ desire to insure themselves against discrimination in the housing market (Van der Bracht et al., Citation2015) and seek acceptance from a mainstream society that perceive homeowners as successful and responsible beings (Constant et al., Citation2009).

Despite harbouring high aspirations, individuals with migrant origins are often documented to exhibit a reduced tendency to own a house with or without a mortgage. This contradiction is largely explained through their socio-economic disadvantages, as compared with the ‘natives’ (Alba & Logan, Citation1992; Constant et al., Citation2009; Haan, Citation2007; Kauppinen & Vilkama, Citation2016; Sinning, Citation2010). More recent studies also demonstrate the significance of such disadvantages, based on comparisons between various migrant groups (Manting et al., Citation2022; Loomans, Citation2023). They, for example, show that migrants on low income are more likely to remain in shared or informal rental housing accommodation for unusually long periods. Their precarious housing arrangements are reported to play a role in shaping their intentions to leave the destination country (Loomans et al., Citation2023).

The literature draws attention to further barriers migrants are likely to encounter in access to credit and housing markets. Their exposure to lower earnings and less stable employment along with less established migration status in the destination country, potentially shorter credit histories and discrimination in the mortgage markets are shown to prevent them from obtaining the credit required for homeownership (Mistrulli et al., Citation2023). Studies targeted at specific ethnic groups demonstrate how they are discriminated against in their mortgage applications (Aalbers, Citation2007; Hanson et al., Citation2016).

In line with the assimilation theory (Alba & Nee, Citation1997; Todaro, Citation1969), migrants are shown to overcome some of these challenges as they spent more time in the destination country (Davidov & Weick, Citation2011; Zuccotti et al., Citation2017). Increased duration of stay is considered to help migrants attain better jobs, learn more about the society and its rules, accumulate stronger social and cultural capital and secure a more stable legal status in the destination country. This is in turn suggested to enhance their ability to navigate through the credit and housing markets and related institutions such as the estate agents.

Housing systems in Turkey and Europe

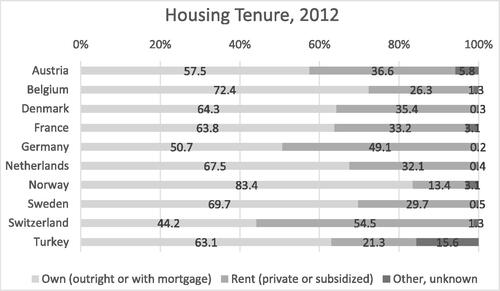

As reviewed earlier, the local and national contextual factors play a key role in decisions about housing. Due to the multi-sited nature of the present study, it is important to briefly describe the housing systems prevalent within the countries involved. presents the housing tenure patterns observed across Turkey and the European countries studied for 2012.Footnote1

Figure 1. Housing tenure patterns in Turkey and Europe. Source: OECD (Citation2012)

Previous studies have classified European countries into housing regime types, taking into account their housing policies and markets, welfare systems, cultural features and levels of economic development. This study amalgamates two housing regime typologies advanced by Dewilde (Citation2017) and Wind et al. (Citation2017). Dewilde (Citation2017) examines the extent of affordable housing for low-to-moderate-income owners and renters across fifteen European countries. She identifies four clusters characterised by the level of state intervention, the function and the size of social housing sector and the welfare system. Wind & colleagues (Citation2017) come up with a similar typology based on homeownership levels, rental sector regulations and housing finance systems. Synthesising the two frameworks, we group the countries into the following regime types: a) regulated rental (Austria, Germany and Switzerland), b) regulated expansion (Belgium and France) and c) liberal expansion (Denmark, Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands).

Regulated rental regime is characterized by low homeownership levels and strict housing finance (mortgage) systems for the German-speaking countries, along with good quality, affordable and regulated rental sector. Regulated expansion regime promotes or at least facilitates homeownership. While these systems are more regulated, access to homeownership is more likely to be stratified according to labour market outcomes such as income levels. Liberal expansion regime, on the other hand, eases the transition to homeownership across different social classes by providing easy access to mortgages for both lower and middle classes (Wind et al., Citation2017).

The Turkish housing system remains rather distinct from the aforementioned regimes in several respects. It operates within a highly inflationary environment which encourages investment in housing whilst making it difficult to establish a functioning mortgage system. As can be seen from , homeownership constitutes the dominant pattern in TurkeyFootnote2 (Sarıoğlu et al., Citation2007), and in the absence of a social housing stock targeted at disadvantaged population groups, private rental emerges as the second most common tenure. That said, in (semi-)rural parts of the country from where the migrants originate and our survey is conducted, outright ownership is likely to prevail due to small-scale family farming being the main economic activity and the opportunity for land-owning farmers to build a house on a section of their land. The co-residence of young people with their parents is also common in Turkey until they marry or save enough money to purchase a house. Given these considerations, the Turkish housing system can be said to resemble the Southern European family ownership regime the most (Filandri & Bertolini, Citation2016).Footnote3

Theoretical perspective: assimilation versus dissimilation

Assimilation and integration theories have provided valuable insight into migrant adaptation to the culture, structure and processes of the destination countries (Van Tubergen, Citation2005). The new generation of assimilation theorists place the emphasis more upon the role of the context in shaping migrant trajectories (Crul & Schneider, Citation2010; Portes et al., Citation2005). However, much of the existing research on migrant trajectories remains focussed on destination country comparisons (Amelina & Faist, Citation2012); largely driven by their policy concerns about migrant assimilation (Waldinger, Citation2017; Wimmer & Schiller, Citation2002). The same applies to studies that specifically examine migrant housing outcomes (Constant et al., Citation2009; Kauppinen & Vilkama, Citation2016; Sinning, Citation2010).

The destination-based research mostly involves comparisons between migrants and the so-called natives. However, to uncover the consequences of migration, migrants also need to be compared to those who stayed in the origin countries as they comprise one of the comparator groups migrants use to make migration decisions and evaluate their outcomes (Güveli et al., Citation2015; FitzGerald, Citation2012; Waldinger, Citation2017). As well as helping to approximate the counterfactual scenario, migrant-stayer comparisons enable an investigation of the degree to which migrants dissimilate from those who stayed in the origin societies. Thereby, the dissimilation from origins perspective offers unique insight into the changes, continuities, gains and losses after migration (Güveli et al., Citation2015; FitzGerald, Citation2012; Waldinger, Citation2017).

In this study, we do not examine assimilation (or integration) outcomes through a comparison of migrants and ‘natives’ over time or across generations, but draw tentative conclusions from the variations observed in housing tenure patterns across different housing regimes governing migrant destinations. In exploring the nature and degree of dissimilation from origins, we extend the migrant-stayer comparisons to include return migrants, and thereby, shed unique light upon the consequences of (re-) migration decisions for housing tenure.

Research hypotheses

The housing tenure patterns for international migrants are anticipated to differ for two fundamental reasons: a) the factors that shape housing outcomes may affect migrants and non-migrants differently, and b) the relative costs and benefits of homeownership may vary across the three groups – i.e. the ‘settlers’, ‘returnees’ and ‘stayers’.

International migrants, especially the ‘settlers’ in Europe are expected to adopt less stable tenure types (e.g. tenancy) for various reasons that are partly intrinsic to the migration process itself (Hypothesis 1). For example, by altering the local and national contexts in which one lives, international migration leads migrants to operate within an unfamiliar environment where they have little or no knowledge about the workings of the housing and credit markets. Within this new environment, they may have no or limited access to social capital resources that are beneficial in terms of house hunting and credit applications. They may also have to move multiple times e.g. to chase job opportunities. Moreover, their plans for the future and return may be uncertain and this may prevent them from committing themselves to house buying in the destination, or delay the process. Besides, migration to another country is likely to disrupt intergenerational transmission of resources required to facilitate transition to homeownership. There is indeed evidence from the wider literature to suggest the effect of parental background to be rather weak in ensuring social mobility and asset accumulation (Bayrakdar & Güveli, Citation2021; Eroğlu, Citation2021).

As reviewed earlier, migrant housing outcomes are also likely to be shaped by structural factors linked with the state of the labour, housing and credit markets. Whilst some of these factors also affect the wider populations to varying degrees, others specifically concern migrants and ethnic minorities. Of particular importance is systemic racism and resulting discrimination that not only has adverse implications for their labour market outcomes (e.g. Di Stasio et al., Citation2021) but also for their access to housing and credit markets (e.g. Mistrulli et al., Citation2023). Such structural barriers are likely to hamper migrants’ integration to the housing regimes of the destination countries.

A different scenario is, however, likely for the returnees to the origin country. As shown in , people in Turkey are inclined towards homeownership. Benefiting from the power of migrant savings, the returnees are anticipated to turn to (outright) homeownership to an equal, if not greater, extent as the stayers in Turkey (Hypothesis 2). These considerations lead us to the overall expectation for the settlers: Their housing tenure outcomes are likely to dissimilate from the origins, but without necessarily becoming similar to the patterns prevailing within their destination countries (Hypothesis 3). In regulated rental markets where access to mortgages is limited and less stigma is attached to private renting, homeownership may become a less attractive option and entry to homeownership may be more equitable than it is in other regimes (Bayrakdar et al., Citation2019). In regulated expansion markets with restricted financial products, housing inequalities tend to be greater than they are in liberal expansion markets where access is relatively decoupled from occupational status and income (Dewilde, Citation2017). Hence, the settlers living in countries governed by the regulated expansion regime are expected to be least well integrated into the destination country housing markets (Hypothesis 4).

Structural reasons, such as the worsening conditions of pay, rising housing prices and difficulty in obtaining or servicing a mortgage/loan, are also likely to restrict the chances of all groups to become homeowners. People’s ability to overcome such structural constraints is likely to vary, depending on the asset status of their parents. Asset-rich, or homeowner, parents would be able to pass on their values about homeownership as well as making direct or indirect transfers to enable their children to become homeowners. However, migration is expected to weaken or interrupt such intergenerational transmissions primarily for reasons mentioned above. The transfers from the stayer and returnee parents onto the settler children are also likely to be hampered by unfavourable currency rates, tax concerns, etc. Coupled with the previously observed tendency for the settlers to own fewer assets than the other two groups (Eroğlu, Citation2021), the settler children are expected to form the least protected group (Hypothesis 5).

Research design and methods

The research base for this study is the pioneering 2000 Families Survey,Footnote4 which located male ancestors who migrated from Turkey to Europe over the guest worker years of 1960s and 1970s and their counterparts who stayed behind (Güveli et al., Citation2016). It follows up their family members up to the fourth generation. Eighty percent of these individuals come from migrant families and the remaining from ‘non-migrant’ families. Members of these families can be men or women and hold a different migration status than their male ancestors.

Sampling and data collection

In sampling ‘migrant’ and ‘non-migrant’ families, the Survey devised and applied an innovative technique of screening in five high migrant-sending regions from rural and semi-urban parts of Turkey: Acıpayam, Akçaabat, Emirdağ, Kulu and Şarkışla.

Eligibility criteria for migrant families were to have a male ancestor who a) might be alive or no longer alive, b) was or would have been between the ages of 65 and 90, c) grew up in one of the aforementioned regions, d) moved to Europe between 1960 and 1974, and e) stayed in Europe for at least five years. The same criteria were applied to non-migrant families, the only difference being that their male ancestors had to have stayed in Turkey rather than migrate to Europe. In every region, a respective quota of 80:20 was imposed for sampling migrant and non-migrant families.

A clustered probability sampling technique was used to screen the regions. One-hundred primary sampling units (PSU) with random starting points were drawn from the Turkish Statistical Institute’s (TURKSTAT) address register, ensuring that each PSU’s size was proportional to the estimated population size of the randomly chosen locality. PSUs were screened based on a random walk strategy, which required starting from a random point and knocking on every door in localities inhabiting less than 1000 households and on every other door if the number of inhabitants was 1000 or above. Four migrant families were sampled for every non-migrant. The random walk ended when 60 households were screened or eight families were recruited.

The screenings were performed in two stages. The pilot study was carried out in Şarkışla in Summer 2010. The main-stage fieldwork was conducted in Summer 2011 to screen the remaining four regions. Approximately 21,000 addresses were visited to hit the target of 400 families per region. The strike rate (i.e. the proportion of eligible families) was around one in every 12 households, yielding 1992 participant families.

The Survey generated data using multiple instruments and two distinct modes of interviewing. Those present in the field were interviewed in person while phone interviews were conducted with those living elsewhere in Turkey or Europe. The data employed in this study are drawn from the personal interviews performed with male ancestors and their randomly selected male and female descendants aged 18 or above. Those eligible for personal interviews included all living male ancestors, their two adult children, two adult children of these two children (i.e., male ancestors’ grandchildren), and these grandchildren’s adult children if any (i.e., male ancestors’ great grandchildren). The family trees constructed for all participating families were used as a sample frame to select the siblings with initials closest to A and Z. The overall response rate was high at 61%, amounting to a total of 5980 personal interviews with individuals nested within 1770 families, and of these, 18% belonged to the first; 46% to the second and 37% to the third generation.

The non-response rate due to reasons other than non-contact (e.g., refusal) was similarly low across eligible family members based in Turkey and Europe, at about 6-8%. However, by the end of the main-stage fieldwork, it became apparent that non-contact rate was higher by approximately 18% for the latter group. This imbalance was redressed through additional three-month tracing performed in 2012 to make contact and interview hard-to-reach family members in Europe. The tracing process yielded 515 interviews, increasing the response rate for this group of respondents by about 20%.

Variable selection

The dependent and independent variables included within the quantitative analyses are presented in the . These variables were selected to capture: a) migration-related influences and b) family endowments in order to throw some light upon questions surrounding migrant dissimilation and the role of parental asset transfers in shaping housing tenure patterns. To this end, the models were specified in the most parsimonious manner to exclude predictors such as ‘highest educational qualification’ that are most likely to absorb some of the migration-related effects.

Table 1. Dependent, independent and control variables.

The dependent variable is obtained from the question of “for the [house] [flat] you are living in, [do you] [are you]: 1. Own it outright; 2. Own it with the help of a mortgage or loan; 3. Tenant; 4. Live there rent free; 5. Other”.

Turning to the independent variables, the ‘family migration background’ has two categories: a) migrant families identified by respondents’ male ancestor who moved to Europe during the guest workers period and non-migrant families identified by respondents’ male ancestor who remained in Turkey. Of particular interest to this study is the ‘individual migration status’ divided into three groups. The first is the ‘settlers’ who had resided in Europe for more than a year and this group includes the native-born. The second is composed of the ‘returnees’ who moved (back) to Turkey after spending a year or more in Europe. The use of the label ‘settlers’ should not be taken to mean that all members of this migrant group plan to indefinitely remain in Europe but were likely to do so, considering that the majority of them are made up of male guest workers and their descendants. The third contains the ‘stayers’, who had not left their origin country for more than a year.

The individual migration status is further differentiated along the major housing regime types synthesised from the works of Dewilde (Citation2017) and Wind et al. (Citation2017). According to this, the settler migrants are divided into three groups living under regulated rental (Austria, Germany, Switzerland) regulated expansion (Belgium and France) and liberal expansion (Denmark, Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands) regimes.

Regarding ‘parental asset status’, this variable is a scale that estimates the overall non-financial assets kept by the respondents’ parents in the parent’s country of residence. It is derived from six questions concerning business, land and house ownership in Turkey and Europe with response categories of 1 “yes, full ownership”, 2 “yes, shared ownership” and 3 “no ownership”. First, these items were recoded to ensure that higher scores indicate greater accumulation [range 0-2], and then added up to create a six-point scale. Finally, the first- and second-generation parents’ asset information was distributed to their respective children from the second and third generations. In other words, dyads were established between parents and their own children to arrive at the parental asset status variable, which is, however, not without its limitations. The main ones are four-fold.

First, for reasons to do with data unavailability, the variable had to exclude financial assets (e.g. savings) to focus solely on non-financial assets that come in the form of a house, land or business space. Second, since the market prices of the parental assets are unknown, the scale would remain insensitive to possible within- and across-country variation in their exchange values. Hence, it cannot be used to estimate wealth per se yet remains a useful indicator of one’s overall stock of non-financial assets. Third, since personal data contain no information about the male ancestor’s parental investments, a dyad could not be established between him and his parents. Last but not least, due to lack of data to determine the value of the assets inherited by the children and/or direct payments they received from their parents toward their education, business, or asset purchases, the variable does not allow family transfers to be measured directly but to be inferred from parental assets. Such an inference is considered reasonable, given a) the potential of such assets to generate cash (e.g., rent) that can then be deployed by parents in building their own children’s asset portfolios and b) the cultural expectations from parents about providing financial support for their children (Eroğlu, Citation2021).

Finally, the control variables of age, sex, marital status and household size are included to represent the key socio-demographic features of the target population. Additionally, the ‘regional origins of migration’ variable is employed to control for the conditions of local labour markets in Turkey.

Methods of analysis

Given the level of measurement for the dependent variable, multinomial probit regression technique was employed in multi-variable estimations of housing tenure. Aimed at addressing RQ.1, Model 1 explores group differences between the settler and returnee migrants and their stayer counterparts primarily to investigate the extent and nature of dissimilation from origins in terms of housing tenure in the current country of residence. Model 2 further differentiates individual migration status by housing regime type to answer RQ.2; in other words, to investigate the degree of destination-country variation in the tenure outcomes for the settlers, as compared with the returnees and stayers who are both exposed to the Turkish housing system. Model 3, which employs the parental asset status variable to examine the role of intergenerational transmissions (or parental asset transfers), is designed to tackle RQ.3. Due to a lack of information about male ancestors’ parental assets, this model had to be confined to the second and third generations. Model 4 specifically investigates the interactions between migration and parental asset status to address RQ.4. All models are checked for multi-collinearity and cluster-corrected to take account of within-family association.

Results

This section will summarise the results obtained from descriptive and multinomial regression analyses. presents the summary statistics for the dependent and independent variables, differentiated along individual migration status. Fifty-six per cent of the stayers, 79% of the returnees and 50% of the settlers own a house (with or without a mortgage) in the country where they currently live. Mortgage holders represent respectively 2% and 3% of the returnees and the stayers while the figure increases to 8% for the settlers in Europe. The tendency for rent-free living appears to be the highest for the stayers in Turkey (16%) and lowest for the settlers (6%). From , which disaggregates the settlers according to the type of housing regime prevalent within their destination country, it can be seen that with 62%, those who migrated to countries governed by regulated expansion regimes display a greater propensity for outright ownership than their counterparts living under regulated rental or liberal expansion regimes.

Table 2. Cross-tabulations with individual migration status.

Table 3. Housing tenure by migration status and country housing regime.

As for the stayers, not all of them remained in the (semi-)rural region of migrant origin. As a matter of fact, 25% (664 out of 2674) moved to other parts of Turkey. shows that amongst internal migrantsFootnote5, tenancy appears as the predominant tenure type with 44%, followed by outright ownership at 34%. However, with 59%, outright ownership emerges as the most common tenure type for the stayers who did not leave the region and this might be one of the reasons as to why they stayed on. Tenancy, constituting the second most common tenure pattern for this group, is closely followed by rent-free living at 17%. Such living arrangement also seems open to the stayers who moved internally but to a lesser extent (i.e. 13%).

Table 4. Housing tenure by internal migration status of stayers in Turkey.

Moving onto the non-dyadic multinomial regression results, these are presented in and . These tables respectively display the estimates obtained from Model 1 that employs the individual migration status variable where the sample is broadly divided into the stayers in Turkey, returnees to Turkey and settlers in Europe. Model 2 further differentiates the settlers in Europe according to the housing regime type prevalent in their destination country. Model 1 shows that, as compared with the stayers in Turkey, the settlers in Europe are significantly more likely to be holders of a mortgage/loan, or tenants than outright homeowners whilst the returnees are less likely to be tenants or make rent-free living arrangements. A similar picture emerges when the model is re-run with a dependent variable that combines outright and mortgage-based ownership categories within a single homeownership category.Footnote6 The model also shows that sex bears no significant relationship with housing tenure. However, as age increases, people appear less likely to remain as tenants, mortgage owners or live rent free. Married people, on the other hand, display a greater propensity than their unmarried counterparts to hold a mortgage or become tenants. The inverse correlation observed between household size and tenancy indicates a significant tendency for larger households to make other housing arrangements than renting.

Table 5. Model 1: Multinomial estimations of housing tenure (N = 5688).

Table 6. Model 2: Multinomial estimations of housing tenure (N = 5695).

As well as verifying the aforementioned findings, Model 2 reveals that across all housing regimes types, the settlers are significantly more likely than their stayer counterparts to hold a mortgage/loan or become tenants. At 0.32, the association size for tenancy is relatively smaller for the settlers living under regulated expansion regimes yet it remains positive and significant at 0.001 level. Having said this, the auxiliary analyses performed with a dependent variable that combines mortgage and outright ownership into homeownership, the observed relationship becomes statistically insignificant.Footnote7 The settlers exposed to such regimes are also significantly less inclined to live rent-free, like the returnees. This tendency is supported by the auxiliary analysis.

Model 3, which uses dyadic data to examine the role of parental asset transfers, confirms the above findings with two exceptions. One concerns the subsequent generations of settlers living under regulated expansion regimes. As can be seen from , they are neither inclined significantly towards tenancy nor outright ownership. The other exception concerns their counterparts exposed to liberal expansion regimes, who are found to make rent-free living arrangements to a considerably lesser extent than the subsequent generations of stayers. More fundamentally, however, Model 3 points to the significance of parental asset status for housing tenure by indicating that independently of the regime type or migration status, the children of asset-rich parents are significantly less likely to become tenants or live rent free but to own a house either outright or with the help of a mortgage/loan. As shown in , Model 4 estimated to explore the interactions between parental asset and individual migration status yields no significant results; suggesting no difference in the effect of parental background across the three groups.

Table 7. Model 3: Dyadic multinomial estimations of housing tenure (N = 3295).

Table 8. Model 4: Dyadic multinomial estimations of housing tenure with interaction term (N = 3295).

An interpretation of the results

In light of the emerging evidence, this section will reflect upon the consequences of migration for housing tenure.

The unique comparisons drawn between the settler and return migrants and their stayer counterparts reveal that migration leads to increased tenancy in the destination country, return migration encourages outright homeownership in the origin country. The return migrants studied here mostly consist of the guestworkers who migrated to Europe before mid-1970s; however, a similar tendency for homeownership is also evident amongst other migrants to EU who returned or intend to return to their origins, including the post-1990 migrants from Eastern European countries (Bertelli et al., Citation2022; Jancewicz, Citation2023). The guestworkers from Turkey were initially sojourners who had no intention to stay in Europe (Akgündüz, Citation2008). It is anecdotally known that the guestworkers who moved from the screened regions were intending to return after having made enough money to buy a house, land and/or agricultural equipment. The returnees seem to have succeeded in realising their initial plans (see also Eroğlu, Citation2021). They may have also benefited from migrating (back) to an economy with cheaper asset prices and favourable currency rates.

By contrast, migration processes have substantially reduced the settlers’ ability to become homeowners in the destination country. By turning more towards tenancy in Europe, the settlers can be said to have dissimilated from their origins in terms of their housing tenure status in the current country of residence. However, the picture changes when the settlers’ housing investments in the origin country are taken into account. Further analyses performed using personal data from the Survey show that 51% of the settlers possess a house in Turkey jointly or individually. At 92%, this tendency appears particularly strong amongst the first-generation settlers (male ancestors). The analyses also reveal that 64% of the settlers who own a house in Europe, and 42% of the settlers currently renting there have part or full ownership of a house in Turkey (as well). We do not exactly know their whereabouts, but the settlers, especially the male ancestors, display a tendency to purchase or build houses in the (semi-)rural regions of migration origins.

Given the aforementioned tendency for homeownership in the origin country, the settlers’ tenure outcomes can be said to resemble those of the stayers who did not leave the regions. This particular group of stayers are more inclined to live as extended families in relatively cheaper houses attached to land that is possibly passed on through generations. That might be part of the reason why rent-free living is more common amongst the stayers who did not move internally. Having said this, such living arrangements occur to a greater extent amongst the stayers who moved internally than their settler and returnee counterparts. In the absence of a social housing stock in Turkey, this is most likely to happen through familial support – which is a cultural expectation. The relatively low uptake of rent-free living by the returnees do not necessarily mean that they have abandoned their cultural norms, however. Previous research shows that they constitute the richest group in terms of their non-financial asset accumulations (see Eroğlu, Citation2021). Thus, it is unlikely that they would need to resort to this particular option. The settlers, especially those exposed to regulated expansion regimes, also appear considerably less inclined towards rent-free living.

Although the housing status of the respondents prior to the start of the guestworker movement remains unknown, the current tenure outcomes for the settlers and the returnees can be said to be more indicative of a migration effect than a selection bias. Migrants can, indeed, form a distinct group with some observed or unobserved characteristics, e.g. in terms of values, skills and motivation, that systematically distinguishes them from non-migrants as well as the returnees. Chiswick (1986), for example, attributes positive qualities (hence outcomes) to migrants who settle in the destination country whilst categorising return migrants as a negatively selected group who lacks the skills and resources required to succeed in a new context. Similarly, Manting et al. (Citation2022) link return migration (intentions) to low income and prolonged, precarious housing arrangements in the destination country. Indeed, a mismatch between expectations and reality in terms of housing and other life outcomes may have played a role in their decision to return; however, the sampled returnees can still be deemed successful given their homeownership outcomes. It remains highly likely that migration to Europe helped them make savings they then converted into housing assets. The settlers were not as successful as the returnees in becoming homeowners in their current country of residence. However, their housing investments in the origin country suggest that the settlers, especially those from the first generation, may have made some economic gains from their decision to migrate. This is supported by previous analysis of the 2000 Families Survey data, which suggests that the settlers, due to their being a negatively selected group in terms of their occupational status, are unlikely to be richer in assets than the stayers prior to their migration to Europe (Güveli et al., Citation2015).

Overall, when their housing investments in Turkey are considered, the settlers in Europe may resemble the stayers. However, they differ considerably from their stayer and returnee counterparts in that they are less likely to become homeowners in the country where they currently live and work. So, whilst dissimilating from their origins, are the settlers becoming better integrated to the destination country housing markets? And if so, is there a more favourable destination housing regime for migrants? Equating favourability with homeownership, housing regimes can be said to make little difference to the settlers’ chances of becoming homeowners. Across all regimes, the settlers display a reduced propensity to become outright homeowners and an increased propensity to hold a mortgage than the stayers. Regime type seems to matter more to the settlers’ tenancy status, however. Those settled into regulated rental and liberal expansion regimes appear to turn more towards renting than outright homeownership. The same tendency does not apply to those living under regulated expansion regime. Therefore, the regulated expansion regime can be deemed slightly more favourable in terms of improving their homeownership status.

Combined with the above, the destination country homeownership rates presented in would allow us to shed some light upon the assimilation/integration question. Given the combined homeownership rates (i.e. outright plus mortgage-based) for the settlers in Belgium (77%) and in France (60%), those exposed to the regulated expansion regime can be considered to be fairly well integrated into the destination country housing systems.

The high tenancy levels for the settlers living under regulated rental regimes in Germany, Austria and Switzerland may lead one to draw a similar conclusion. These countries display the lowest three homeownership rates in Europe. However, except for Switzerland, homeownership continues to represent the dominant tenure in 2012 for the countries governed by this particular regime type. Yet, the combined homeownership rates for the settlers in Germany (42%) and Austria (27%) both remain considerably below the national population figures.

For those living under liberal expansion regimes (i.e., Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands), the overall tendency remains towards increased tenancy although this regime type actively promotes homeownership. Indeed, the tenancy rates for the settlers in Denmark (63%) and Sweden (51%) remain higher than the combined homeownership levels – which stand at 30% and 49%, respectively. The reverse is, however, true for Norway and the Netherlands given the respective rates of tenancy and combined homeownership, which stand at 16% and 58% for NorwayFootnote8 and 44% and 49% for the Netherlands. Having said this, in all four countries, the combined homeownership rates for the settlers remain considerably below the 2012 general population rates.

Hence, it proves rather difficult to conclude that the settlers, especially those living under the liberal expansion regime, are well-integrated into the housing markets of their destination countries. A firmer conclusion would, however, require taking into account migration intentions (e.g. return plans), which may well be equally, if not more, important than the time spent in Europe. Indeed, considering the settlers’ average duration of stay in Europe [mean = 28 years, std = 10] and its fairly even distribution across the three regime typesFootnote9, it is unlikely that the duration of stay would make a significant difference in their particular case. It may well be that the route to successful integration to the destination country housing systems is being blocked for some settlers for structural reasons to do with the state of the European labour, housing and credit markets.

Similar factors may be influential in reducing younger people’s chances of becoming homeowners. However, intergenerational family (or parental asset) transfers appear to enhance their chances independently of their migration status or country context. Such transfers can come in different shapes and forms, including making a down payment towards children’s mortgage, gifting a parental property and purchasing a new house. Until recently, house prices in Turkey had been cheaper both in relative and absolute terms. When considered in conjunction with the lower mortgage take up amongst the stayers in Turkey, gift giving and purchasing a new house become more of an option for the children residing in the origin country.

Conclusion

The results obtained from the comparisons drawn between the settlers, stayers and the returnees lend some support to all but two of the hypotheses (i.e. 4 & 5) set out earlier. They confirm that it is the settlers in Europe who turn more towards tenancy whilst the returnees become (outright) homeowners to a greater extent than the stayers in Turkey. The settlers end up dissimilating from their origins in terms of their housing tenure status in the country of residence, but without becoming well integrated to the destination country housing systems. This is most evident from the case of the settlers living in some of the countries governed by liberal expansion regimes, namely Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands. Their case runs counter to our expectations about migrant integration as well as the past research findings, which document the best housing outcomes for younger people in Scandinavian countries (Lennartz et al., Citation2016). The emergence of worst integration outcomes in a housing regime that is meant to ease the transition of lower classes to homeownership does imply that discriminatory forces may be at play.

In line with previous research (Clark et al., Citation1997; Kulu & Steele, Citation2013), younger people are found to become tenants to a considerable extent whilst the children of asset-rich parents turn to homeownership. Contrary to our expectations, migration processes turned out not to significantly weaken the parental resource transfers facilitating homeownership. It is rather shown that asset-rich parents are able to purchase houses for their children or enable their purchase wherever they are based.

Like all research, this study is fraught with certain limitations. First of all, due to the focus of the Survey on the guest-worker movement from Turkey to Europe, the personal interview data only partially capture migrants who moved after the mid-1970s. Hence, conclusions drawn here cannot be extrapolated to the entire Turkish Diaspora in Europe. Secondly, the aim of this study was not to decipher the key determinants of housing tenure outcomes for migrants and their descendants but rather to understand the consequences of international migration. Further analyses can, however, be performed with the sub-group of ‘settlers’ to examine the role of certain factors such as social class, time spent in Europe and migration intentions (i.e. return plans). Thirdly, migration-related effects are inferred here from the three-way comparisons drawn between the settlers, returnees and stayers. Multi-site comparisons of migrants and stayers represent the best option for understanding such effects in a fluid social world, which rarely presents an opportunity to design an experimental or longitudinal study. To be able to fully disentangle migration-related effects from self-selection bias, it would be ideal to trace the housing status of migrants before and after migration. This would, for example, allow us to better disentangle the chances of settlers in Europe to become homeowners in Turkey had they not migrated to Europe. Therefore, researchers may want to explore ways to reach this ideal. Finally, tentative conclusions about migrant integration have been made here, based on comparisons across housing regimes and destination country’s overall populations but without necessarily comparing like with like. Future research is, therefore, needed to extend migrant-stayer comparisons to include the ‘natives’ living in the destination country/countries.

Overall, our research closes a substantial gap in our understanding about the consequences of migration on housing tenure status of migrants who settled in Europe and who returned to Turkey and their counterparts who stayed in Turkey. We showed that migration benefited returnees in acquiring homeownership. However, the pioneer migrants from Turkey and their descendants who made Europe their homes are more likely to reside in rental housing, as compared with their peers in Turkey. Remarkably, those living in countries under liberal expansion regimes with policies to protect lower classes (esp. Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands) are less likely to own a house than their peers exposed to other regimes. The chances of becoming a homeowner are, however, increased for children from asset-rich parental backgrounds, independently of their migration status.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Şebnem Eroğlu

Şebnem Eroğlu is an Associate Professor in Social Policy at the School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol. Her research interests lie in the areas of poverty, migration and household livelihoods.

Sait Bayrakdar

Sait Bayrakdar is a Research Associate at the School of Education, Communication and Society at King’s College London. He is one of the co-investigators of the ESRC-funded project, ‘Opportunity, Equality and Agency in England’s New VET Landscape: A Longitudinal Study of Post-16 Transitions’. His research interests include social inequalities, education, migration and youth transitions.

Ayse Guveli

Ayse Guveli works in the Department of Sociology at the University of Warwick, researching inequalities, migration, religion, gender and family. She led international research projects, such as the 2000 Families, among others. She has recently received the ERC Consolidator grant, funded by the UKRI (€2.75million) to investigate the grandchildren of the pioneer labour migrants in Europe. Ayse is an expert for the European Commission’s gender equality unit.

Notes

1 2012 is chosen to capture the time span of the 2000 Families Survey (2010-2012), which forms the research base for this article.

2 Homeownership rates in Turkey have been historically high; there has however been a recent decline. The most recent figures show that 60.7% of households are owner-occupied (TÜİK, Citation2021).

3 With increased financialization of the Turkish housing market (Yeşilbağ, Citation2020), Turkey has in recent years moved more towards the unregulated expansion regime where homeownership is facilitated by the state and an ever-growing mortgage market. Given the time span of the 2000 Families Survey (2010-2012), a detailed depiction of the latest developments in the Turkish housing market remains beyond the scope of this article.

4 The authors have used parts of the Survey data in previous publications to explore various other migrant outcomes (see e.g., Bayrakdar & Guveli, Citation2021; Eroğlu, Citation2022; Guveli et al., Citation2015; Guveli & Spierings, Citation2022).

5 Total number of internal migrants in Turkey amount to 644 as opposed to 664 in Table 4 due to missing housing tenure info.

6 mprobit (se) for tenant settlers = 0.79 (0.81), p < 0.001; mprobit (se) for tenant returnees = - 0.33 (0.10), p < 0.01.

7 mprobit (se) for settler tenants in regulated expansion regimes = 018 (0.14), p = 0.208.

8 Note the low sample size for Norway [N = 19].

9 Average duration is 27 [std =10] for the settlers into regulated rental regimes; 30 [std = 10] for the settlers into regulated expansion regimes and 27.6 [std. = 11] for the settlers into liberal expansion regimes.

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2007) Place-based and race-based exclusion from mortgage loans: Evidence from three cities in The Netherlands, Journal of Urban Affairs, 29, pp. 1–29.

- Akgündüz, A. (2008) Labour migration from Turkey to Western Europe, 1960-1974: A multidisciplinary analysis (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing).

- Alba, R. D. & Logan, J. R. (1992) Assimilation and stratification in the homeownership patterns of racial and ethnic groups, International Migration Review, 26, pp. 1314–1341.

- Alba, R. & Nee, V. (1997) Rethinking assimilation theory for a new era of immigration, International Migration Review, 31, pp. 826–874.

- Amelina, A. & Faist, T. (2012) De-naturalizing the national in research methodologies: Key concepts of transnational studies in migration, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35, pp. 1707–1724.

- Arundel, R. (2017) Equity inequity: Housing wealth inequality, inter and intra-generational divergences, and the rise of private landlordism, Housing, Theory and Society, 34, pp. 176–200.

- Bayrakdar, S. & Guveli, A. (2021) Understanding the benefits of migration: multigenerational transmission, gender and educational outcomes of Turks in Europe, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47, pp. 3037–3058.

- Bayrakdar, S., Coulter, R., Lersch, P. & Vidal, S. (2019) Family formation, parental background and young adults’ first entry into homeownership in Britain and Germany, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 974–996.

- Bertelli, D., Erdal, M. B., Coşciug, A., Kussy, A., Mikiewicz, G., Szulecki, K. & Tulbure, C. (2022) Living here, owning there? Transnational property ownership and migrants’(Im) mobility considerations beyond return, Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 11, pp. 53–67.

- Clark, W. A., Deurloo, M. C. & Dieleman, F. M. (1997) Entry to home-ownership in Germany: Some comparisons with the United States, Urban Studies, 34, pp. 7–19.

- Constant, A. F., Roberts, R. & Zimmermann, K. F. (2009) Ethnic identity and immigrant homeownership, Urban Studies, 46, pp. 1879–1898.

- Coulter, R. (2018) Parental background and housing outcomes in young adulthood, Housing Studies, 33, pp. 201–223.

- Coulter, R. (2023) Housing and life course dynamics: Changing lives, places and inequalities (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Coulter, R., Bayrakdar, S. & Berrington, A. (2020) Longitudinal life course perspectives on housing inequality in young adulthood’, Geography Compass, 14, pp. e12488.

- Crul, M. & Schneider, J. (2010) Comparative integration context theory: Participation and belonging in new diverse european cities, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33, pp. 1249–1268.

- Davidov, E. & Weick, S. (2011) Transition to homeownership among immigrant groups and natives in west Germany, 1984–2008, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 9, pp. 393–415.

- Dewilde, C. (2017) Do housing regimes matter? Assessing the concept of housing regimes through configurations of housing outcomes, International Journal of Social Welfare, 26, pp. 384–404.

- Di Stasio, V., Lancee, B., Veit, S. & Yemane, R. (2021) Muslim by default or religious discrimination? Results from a cross-national field experiment on hiring discrimination, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47, pp. 1305–1326.

- Doling, J. & Ronald, R. (2010) Home ownership and asset-based welfare, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25, pp. 165–173.

- Eroğlu, Ş. (2021) Understanding the consequences of migration for asset accumulation: A multi-site and intergenerational perspective, International Migration Review, 55, pp. 785–811.

- Eroğlu. (2022) Poverty and international migration: A multi-site and intergenerational perspective (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Filandri, M. & Bertolini, S. (2016) Young people and home ownership in Europe, International Journal of Housing Policy, 16, pp. 144–164.

- FitzGerald, D. (2012) A comparativist manifesto for international migration studies, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35, pp. 1725–1740.

- Guveli, A. & Spierings, N. (2022) Migrant women’s employment: international Turkish migrants in Europe, their descendants, and their non-migrant counterparts in Turkey, European Sociological Review, 38, pp. 725–738.

- Güveli, A., Ganzeboom, H., Platt, L., Bernard, N., Baykara, H., Eroğlu, Bayrakdar, S., Sozeri, E. K. & Spierings, N. (2015) Intergenerational Consequences of Migration: Socio-Economic, Family and Cultural Patterns of Change in Turkey and Europe (Basingstoke: Palgrave).

- Güveli, A., Ganzeboom, H., Baykara-Krumme, H., Bayrakdar, S., Eroğlu, Hamutçi, B., Nauck, B., Platt, L. & Sözeri, K. E. (2016) 2000 Families: Migration histories of Turks in Europe, GESIS Archive: Leibnitz Institute for the Social Sciences, ZA5957 Data file version 2.0.0.

- Haan, M. (2007) The homeownership hierarchies of Canada and the United States: The housing patterns of white and non-white immigrants of the past thirty years, International Migration Review, 41, pp. 433–465.

- Hanson, A., Hawley, Z., Martin, H. & Liu, B. (2016) Discrimination in mortgage lending: Evidence from a correspondence experiment, Journal of Urban Economics, 92, pp. 48–65.

- Hochstenbach, C. & Arundel, R. (2021) The unequal geography of declining young adult homeownership: Divides across age, class, and space, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 46, pp. 973–994.

- Jancewicz, B. (2023) Real estate in the home country: Why polish migrants keep properties in Poland, International Migration, 61, pp. 289–302.

- Kauppinen, T. M. & Vilkama, K. (2016) Entry to homeownership among immigrants: A decomposition of factors contributing to the gap with native-born residents, Housing Studies, 31, pp. 463–488.

- Kemeny, J. (2006) Corporatism and housing regimes, Housing, Theory and Society, 23, pp. 1–18.

- Kulu, H. & Steele, F. (2013) Interrelationships between childbearing and housing transitions in the family life course, Demography, 50, pp. 1687–1714.

- Lennartz, C., Arundel, R. & Ronald, R. (2016) Younger adults and homeownership in Europe through the global financial crisis, Population, Space and Place, 22, pp. 823–835.

- Lerbs, O. W. & Oberst, C. A. (2014) Explaining the spatial variation in homeownership rates: Results for german regions, Regional Studies, 48, pp. 844–865.

- Lersch, P. M. & Luijkx, R. (2015) Intergenerational transmission of homeownership in Europe: Revisiting the socialisation hypothesis, Social Science Research, 49, pp. 327–342.

- Loomans, D. (2023) Long-term housing challenges: The tenure trajectories of EU migrant workers in The Netherlands, Housing Studies, pp. 1–28.

- Loomans, D., Lennartz, C. & Manting, D. (2023) A longitudinal analysis of arrival infrastructures: The geographic pathways of EU labour migrants in The Netherlands, Population, Space and Place, 30, e2747.

- Magnusson Turner, L. & Hedman, L. (2014) Linking integration and housing career: A longitudinal analysis of immigrant groups in Sweden, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 270–290.

- Manting, D., Kleinepier, T. & Lennartz, C. (2022) Housing trajectories of EU migrants: Between quick emigration and shared housing as temporary and long-term solutions, Housing Studies, 39, pp. 1027–1048.

- McKee, K. (2012) Young people, homeownership and future welfare, Housing Studies, 27, pp. 853–862.

- McKee, K., Muir, J. & Moore, T. (2017) Housing policy in the UK: The importance of spatial nuance, Housing Studies, 32, pp. 60–72.

- Mulder, C. H. & Lauster, N. T. (2010) Housing and family: An introduction, Housing Studies, 25, pp. 433–440.

- Mulder, C. H. & Wagner, M. (1998) First-time home-ownership in the family life course: A west German-Dutch comparison, Urban Studies, 35, pp. 687–713.

- Mistrulli, P. E., Uddin, M. T. & Zazzaro, A. (2023) Discrimination of Immigrants in Mortgage Pricing and Approval: Evidence from Italy (No. 180) Money and Finance Research group (Mo. Fi. R.)-Univ. Politecnica Marche-Dept. Economic and Social Sciences.

- Nethercote, M. (2019) Immaterial inheritance: The socialization of cultures of housing consumption, Housing, Theory and Society, 36, pp. 359–375.

- OECD (2012) Housing, Database, Available at https://www.oecd.org/housing/data/affordable-housing-database/housing-market.htm (accessed 28 April 2023).

- Özüekren, A. S. & Van Kempen, R. (2002) Housing careers of minority ethnic groups: Experiences, explanations and prospects, Housing Studies, 17, pp. 365–379.

- Portes, A., Fernández-Kelly, P. & Haller, W. (2005) Segmented assimilation on the ground: The new second generation in early adulthood, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28, pp. 1000–1040.

- Ronald, R. (2008) The ideology of home ownership: Homeowner societies and the role of housing (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Sarıoğlu, G. P., Balamir, M., Pellenbarg, P. H. & Terpstra, P. R. A. (2007) Rented and owner-occupied housing: A descriptive study for two countries-Turkey and the Netherlands. In: ENHR 2007 International Conference W (Vol. 12).

- Sinning, M. (2010) Homeownership and economic performance of immigrants in Germany, Urban Studies, 47, pp. 387–409.

- Todaro, M. P. (1969) A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries, The American Economic Review, 59, pp. 138–148.

- TÜİK (2021) Survey on Building and Dwelling Characteristics Bulletin, Bulletin, Available at: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Survey-on-Building-and-Dwelling-Characteristics-2021-45870 (accessed 19 February 2023).

- Van der Bracht, K., Coenen, A. & Van de Putte, B. (2015) The not-in-my-property syndrome: The occurrence of ethnic discrimination in the rental housing market in Belgium, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41, pp. 158–175.

- Van Tubergen, F. (2005) ‘The integration of immigrants in cross-national perspective: Origin, destination and community effects’, PhD Dissertation, University of Utrecht.

- Waldinger, R. (2017) A cross-border perspective on migration: Beyond the assimilation/transnationalism debate, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43, pp. 3–17.

- Wind, B., Lersch, P. & Dewilde, C. (2017) The distribution of housing wealth in 16 European countries: Accounting for institutional differences, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32, pp. 625–647.

- Wimmer, A. & Schiller, N. G. (2002) Methodological nationalism and the study of migration, European Journal of Sociology, 43, pp. 217–240.

- Yeşilbağ, M. (2020) The state-orchestrated financialization of housing in Turkey, Housing Policy Debate, 30, pp. 533–558.

- Zeyneloğlu, S. & Sirkeci, İ. (2014) Türkiye’de Almanlar ve Almancılar, Göç Dergisi, 1, pp. 77–118.

- Zorlu, A., Mulder, C. H. & Van Gaalen, R. (2014) Ethnic disparities in the transition to home ownership, Journal of Housing Economics, 26, pp. 151–163.

- Zuccotti, C. V., Ganzeboom, H. B. G. & Guveli, A. (2017) Has migration been beneficial for migrants and their children? Comparing social mobility of Turks in Western Europe, Turks in Turkey, and Western European natives, International Migration Review, 51, pp. 97–126.