Abstract

Housing scholars have demonstrated that intimate partner violence (IPV) is a key driver of housing instability. Contributing to existing housing literature that foregrounds the importance of material and psychological housing instability, our empirical research focuses on a novel programme providing supportive housing for women, the majority of whom are allocated housing to protect them from IPV. Our data includes in-depth interviews with the supportive housing tenants and practitioners, as well as administrative data. Our findings illuminate the close interrelation between material and psychological housing instability, and demonstrate how problems inherent in the private rental market interact with issues caused by perpetrators’ ongoing use of violence in ways that make it impossible for women to achieve either form of stability. The implication for housing scholars is to understand that although affordable housing is a protective measure, supportive housing models that rely on the private rental market, face profound limitations in achieving material and psychological housing stability for women who experience IPV.

Introduction

Housing scholars have clearly demonstrated the link between women’s experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) and housing instability. Indeed, women who experience IPV—defined as any form of violence perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner (Adams et al., Citation2021)—face a risk of housing instability that is four times greater than the risk faced by women who do not experience IPV (Pavao et al., Citation2007). Existing literature identifies two core forms of housing instability: material instability and psychological instability. Material housing instability relates to the material aspects of housing, such as the condition of the property, affordability, length of tenure, frequency of moves, overcrowded conditions, and risk of becoming homeless (Daoud et al., Citation2016; Rollins et al., Citation2012). Psychological housing instability, on the other hand, relates to factors such as safety, security, financial stress, and neighbourhood connection (Daoud et al., Citation2016; O’Campo et al., Citation2016). An established body of literature examines how experiences of IPV can significantly undermine a woman’s ability to achieve material housing stability (Adams et al., Citation2021; Baker et al., Citation2010; Blunden & Flanagan, Citation2022; Gilroy et al., Citation2016) and psychological housing stability (Daoud et al., Citation2016; O’Campo et al., Citation2016).

Informed by this evidence are growing calls for housing programmes to respond to the “co-occurring and contextual circumstances related to both housing and IPV” that impact on the material and, in particular, psychological housing instability of women who leave violent relationships (O’Campo et al., Citation2016, p. 3; see also Adams et al., Citation2021; Baker et al., Citation2010; Gezinski & Gonzalez-Pons, Citation2021). While many existing housing programmes for women with histories of IPV involve facilitating access to housing through the private rental market (Baker et al., Citation2010; Blunden & Flanagan, Citation2022), these programmes are rarely equipped with intensive multidisciplinary supports to respond to the complex contextual circumstances of participating women (Adams et al., Citation2021). As such, little is known about the extent to which comprehensive supportive housing programmes can successfully support women leaving IPV to achieve material and psychological housing stability through the private rental market. To address this gap, our study empirically examines a novel supportive housing programme that aims to address both forms of housing instability among this cohort.

Literature review

Conceptualising housing instability in IPV contexts

Conceptualisations of housing instability in the literature are multiple and varied. Some conceptualise housing instability in terms of the ‘multiple ongoing difficulties, both personal and economic’ that impact a person’s ability to maintain housing, including their ability to access housing, pay rent and other bills, avoid eviction, and remain in a single tenancy over time (Rollins et al., Citation2012, p. 625). Others take a slightly broader approach, including aspects such as the quality and appropriateness of the housing, housing condition, and control over living environment (Frederick et al., Citation2014). Despite their differences in scope, these definitions share the commonality of being focused on the material aspects of housing instability.

An established body of literature investigates the mechanisms underpinning the challenges women who experience IPV face in achieving material housing stability. Difficulties accessing employment (Adams et al., Citation2021; Baker et al., Citation2010; Daoud et al., Citation2016), along with the high costs of private rental and limited availability of affordable housing stock (Blunden & Flanagan, Citation2022) are commonly explored barriers preventing women from accessing and maintaining tenancies when leaving IPV. In Australia, recent evidence has shown that only 0.8% of rental properties were affordable for a single person on a minimum wage (Anglicare Australia, Citation2023). A similar lack of affordability has been documented in other Western nations, such as the United States (Airgood-Obrycki et al., Citation2022), and England and Wales (Office of National Statistics, Citation2023).

The unaffordable private rental market means that low-income women leaving violence are often unable to access housing at all and, when they are, must either accept sub-standard housing that does not meet their needs, or are forced into housing stress by paying more than 30% of their income on housing (Blunden & Flanagan, Citation2022). In many cases, when women leaving violence apply to access rental housing, their applications are rejected due to poor rental histories, being single mothers on welfare, appearing as unreliable tenants due to histories of transience, prior evictions due to violent (ex-)partners causing disturbances or damage to properties, and the high risks associated with IPV (Barata & Stewart, Citation2010; Bomsta & Sullivan, Citation2018; Gezinski & Gonzalez-Pons, Citation2021). This illustrates the strong links between men’s use of IPV and women’s experiences of material housing instability.

Less-often explored in the literature are women’s experiences of psychological housing instability due to IPV. Psychological housing instability moves beyond material considerations to include aspects such as safety, security, and independence; psychological stress as a result of material housing instability; financial stress; and neighbourhood cohesion and connection (Daoud et al., Citation2016; Hetling et al., Citation2020; O’Campo et al., Citation2016; Yuan et al., Citation2023). Woodhall-Melnik et al. (Citation2017) argued that psychological housing instability is important to consider alongside material housing instability, as women’s own understandings of housing stability are multifaceted, including both material aspects as well as psychological aspects. It is therefore critical to develop a deep understanding of women’s experiences of both material and psychological housing instability within IPV contexts, as well as how current housing initiatives are working to promote material and psychological housing stability for these women.

Experiences of housing instability in targeted housing programmes

A range of transitional and permanent housing programmes exist for women who have experienced IPV to help support them to access and sustain stable housing. Many such programmes in Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom involve government agencies providing rental subsidies to support women to access the private rental market (Baker et al., Citation2010; Blunden & Flanagan, Citation2022). An increasing body of research, particularly from the United States, investigates the successes of targeted housing programmes in promoting housing stability among women who have experienced IPV.

Wood et al. (Citation2023), for example, examined rapid rehousing services for women experiencing IPV in the United States. Rapid rehousing programmes support people to access rental accommodation through housing vouchers, with the idea that once housed, tenants will improve their economic stability and take over the lease independently at the end of their time in the programme. The programme in question provided assistance for an average of 12 months. The study found that the programme enabled the women to overcome barriers to accessing housing, although the housing they were ultimately able to access did not fully meet their material or psychological housing needs. For example, many women were only able to access housing that was run down, infested, or lacked basic working appliances. Others were unable to find affordable housing in their preferred communities, and therefore had to accept housing that was away from their support networks or in areas with high rates of violence. For many women in the programme, safety remained an ongoing issue.

Indeed, the ability of housing programmes to provide for the safety and other intensive needs of women who experience IPV remains a challenge. In a review of policies and practices of housing programmes that provide subsidies for properties on the private rental market, Baker et al. (Citation2010) found that such programmes often failed to incorporate the necessary supports for women who had experienced IPV, including safety planning, advocacy, and referring women to external support services. More recently, Adams et al. (Citation2021, p. 3473) foregrounded ‘the necessity of comprehensive rapid rehousing programmes that provide women who have experienced IPV with long-term flexible financial support, housing assistance, and advocacy.’ Indeed, scholars have increasingly called for housing programmes to be better equipped with integrated supports to address the unique and interrelated needs of women who experience IPV to support them to achieve long-term housing stability (Adams et al., Citation2021; Gezinski & Gonzalez-Pons, Citation2021; Jeffrey & Barata, Citation2017; O’Campo et al., Citation2016).

To date, few such integrated programmes have been implemented and reported on in the literature, specifically in terms of the extent to which these programmes are able to address the material and psychological housing instability these women experience. Thus, although there are increasing calls for housing programmes to integrate multidisciplinary supports as a means of supporting women to achieve housing stability on the private rental market, there is currently limited empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness of such programmes. It is therefore crucial to improve our understanding of the extent to which dedicated housing programmes, in conjunction with a range of multi-disciplinary wraparound supports, are able to support women who experience IPV to achieve housing stability through the private rental market.

To address this gap, this paper empirically examines a novel integrated supportive housing programme that aims to address housing instability and compounded disadvantage as they relate to IPV. As with many current housing models that target women leaving IPV, the programme we examine provides subsidised housing head-leased through the private rental market and integrates housing with a suite of interdisciplinary supports. The programme thus specifically aims to address women’s multiplicity of needs, including both material and psychological forms of housing instability. We aim to contribute to the housing literature with our empirical investigation that seeks to understand women’s experiences of material and psychological housing (in)stability during their time in the programme, as well as the factors that facilitated or undermined their ability to achieve housing stability.

Programme context

In 2020, the state government of Queensland, Australia, funded a supportive housing programme (SHP) for low-income families at risk of experiencing homelessness and at risk of engaging with the statutory child protection system. The SHP houses 20 families at any one time through the private rental market. Consistent with the supportive housing literature (Rog et al., Citation2014), the SHP consists of tenancy management and support provision. Tenancy management and support provision are provided by separate organisations, which are funded to collaborate in the delivery of an integrated supportive housing model. Through a government-funded housing subsidy, housing is head-leased by the tenancy manager, who pays market rent for the properties. The properties are then subleased to participants, who pay rent to the tenancy manager at a subsidised rate of 25% of their income. Participants sub-lease from the tenancy manager, which acts as their landlord, responsible for collecting rent, routinely inspecting the properties alongside real estate agents, and responding to maintenance issues. SHP is currently funded for a 5-year period, within which participants may remain in the programme for as long as they continue to experience extremely low income.

Although having experience of IPV is not a criterion for participating in the SHP, the programme is designed to account for the high risks of IPV often faced by such a cohort. Indeed, 72% of participating women reported experiencing IPV upon programme entry—although this is likely underreported and does not capture lifetime experiences—and IPV was identified as the leading risk factor for child protection intervention. Similarly, although being a single woman with children was not a criterion for participation in the programme, the majority of the SHP families were headed by mothers who, at the time of programme entry, were single. However, women’s relationship statuses were fluid and often changed throughout their time in the programme.

In recognition of the high risk of IPV for women in SHP, a range of mechanisms are built into the programme to address these risks. For example, where possible, properties are sourced specifically to meet the needs of each family. Safety needs in particular are taken into account including, where possible, by choosing suburbs that are away from perpetrators, sourcing properties inside secure complexes, locating women close to their families and, in collaboration with landlords and real estate agents, installing fences and security cameras.

In addition to these housing-related mechanisms, there are also a range of wraparound supports available to help women to stabilise and move forward with their lives. These included a diverse and flexible range of services, provided by the support provider and through referrals. The services delivered by the support provider include developing a plan to help women maintain their tenancies, supporting women to access protection orders and legal support, responding to child safety risks, identifying and addressing child wellbeing needs, and providing practical assistance to improve the quality of their lives. The support provider also offers parenting education and family support to help promote positive parent-child interactions, while also supporting the women to access employment and training opportunities. It also includes flexible brokerage funds to support family wellbeing and ongoing access to affordable housing, such as paying for removal costs. Reflecting the ideal approach outlined in the literature (Adams et al., Citation2021; Gezinski & Gonzalez-Pons, Citation2021; O’Campo et al., Citation2016), the programme thus specifically aims to address women’s multiplicity of needs, including both material and psychological forms of housing instability.

Methods

Using a mixed-methods approach, this study empirically examines women’s experiences of housing during their time in the SHP, with a particular focus on the factors that facilitated or undermined their ability to achieve housing stability. The study seeks to address the following research questions: (1) What were women’s experiences of material and psychological housing (in)stability within supportive housing on the private rental market? (2) How do women and tenancy and support practitioners perceive and make sense of housing (in)stability in the context of IPV and the private rental market?

As discussed more fully above, the SHP began in mid-2020 and is funded to house 20 families at any one time. Since its inception, 33 women and their children have been housed through the programme. The invitation to participate was open to all women who had ever participated in the programme.

Quantitative data and analyses

The quantitative component of the study involved conducting descriptive analyses of administrative data. Administrative data is a form of data that is collected by organisations or governmental departments as part of their daily operational practices, including service delivery and record keeping (Connelly et al., Citation2016). That is, administrative data is not collected for the purpose of conducting research, and researchers have no input into what data is collected or how it is collected. This makes it an important form of real-world data that provides critical insight into the delivery of programmes such as SHP in practice. It also means we faced unique limitations related to the depth of the data, which we explain in detail in our limitations section.

Two forms of administrative data were used in our study, provided to us by the tenancy manager and support provider respectively. We explain each form of administrative data in detail below. Upon entering the programme, all participants signed consent forms allowing the data collected throughout their time in the programme to be used in de-identified from for advocacy and reporting purposes, including reporting on the successes and challenges of the programme. We received approval for receiving and analysing these data in deidentified form from our institution’s Human Research Ethics Committee (number: [removed for peer review]).

First, we drew on data collected by the tenancy manager regarding women’s tenancies. Each woman’s tenancy-related data was recorded by tenancy practitioners in real time, including the date women entered the SHP, the date they moved into and out of each tenancy, the reasons for changing tenancies, and the date of programme exit. Given that the tenancy practitioners were responsible for identifying and head-leasing properties, supporting women to move in and out, and dealing directly with the real estate agents for the duration of women’s tenancies, this data was recorded by the practitioners themselves. The tenancy records of 32 women were provided to us by the tenancy manager, and included data from when they first entered the programme up to September 2023. We drew on these data to understand if and how the women in the SHP experienced housing instability throughout their time in the programme, as well as the factors that underpinned this instability.

Second, we drew on assessment data collected by the support provider. Upon programme entry and again at quarterly intervals, support practitioners worked with programme participants to complete the assessments as a way of identifying fluctuations in support needs. These assessments took the form of questionnaires, which collected demographic information and asked participants to indicate their level of agreement, ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘an extreme amount’, with questions related to their connection to community, family support, and feelings of safety within their families and from (ex-)partners. To prepare this data for descriptive analyses, we collapsed these categories into two groups: ‘not at all’, representing 0, and all other values ranging from ‘a little’ to ‘an extreme amount’, taking the value 1. In other words, we recoded ordinal variables from assessment data as dummy or binary variables where needed. While this may lead to a loss of nuance, it helps improve the reliability of our analysis as certain categories of the ordinal variables have very small sample sizes.

The assessment data for 32 women were provided to us, and included data from when they first entered the programme up to September 2023. We drew on these data to examine aspects of psychological housing instability, including changes in women’s feelings of safety and community connection across their time being housed through the programme.

Qualitative data and analyses

The qualitative component of the study involved in-depth, semi-structured interviews with women in the programme, as well as with the tenancy and support practitioners delivering the programme. Qualitative interviews were conducted at two time points. The first time point was approximately six to twelve months after the commencement of the programme. All women enrolled in the programme at the time, and all practitioners delivering the programme at the time, were invited to participate. A total of 17 women and 10 practitioners participated in an interview at this time. The second time point was approximately 36 months after the commencement of the programme. All women enrolled in the programme at the time, and all practitioners delivering the programme at the time, were once again invited to participate (noting that there had been some turnover among participants in both cohorts). A total of 19 women and 8 practitioners participated at the second time point. Across the two time points combined, 28 women participated − 20 participated at only one time point and 8 participated at both time points. On the other hand, a combined total of 16 practitioners participated − 14 participated at only one time point and 2 participated at both time points.

Interviews were conducted by the researchers and aimed to elicit the experiences of the participants. Topics explored in the interviews sought to examine these experiences through four broad lines of questioning: (1) What does the programme look like to you? (2) What does the programme mean for participating families? (3) What aspects of the programme do you think work well? (4) What aspects of the programme do not work well? Critically, these broad lines of questioning did not explicitly focus on IPV or housing instability. Rather, IPV and housing instability were topics that were raised organically by participants during the interviews, and as noted, resulted in findings that were substantiated through both qualitative interviews and administrative data.

With participants’ prior consent, the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Following Padgett (Citation2017), we conducted a thematic analysis, which embedded strategies to promote rigour. To begin the analysis, we familiarised ourselves with the transcripts by reading over them several times. Then, utilising NVivo software to help manage the data, the authors collaboratively developed an initial descriptive coding frame informed both by these readings of the data and by the overarching aims of the study. After initial coding, and drawing on existing knowledge reported in previous literature, the codes were then arranged and grouped under broader analytic themes. The most prominent of these themes were selected and presented in the below analysis.

Following Fetters et al. (Citation2013), our integration of the qualitative and quantitative data sources occurred at the interpretation and reporting level. Adopting an ‘integrating through narrative’ approach, the findings presented below weave the qualitative and quantitative findings together according to themes. Significantly, our concurrent use of interviews with the women in the programme and the practitioners delivering the programme, alongside the use of administrative data, enabled us to triangulate different perspectives. This was not in an attempt to identify a single objective ‘truth’; rather, following Padgett (Citation2017), we aimed to bring together different experiences, perspectives, and data sources to provide and breadth and depth of understanding of participants’ lived experiences. Indeed, taking seriously people’s experiences, our epistemological position recognised that support and housing interventions can only be made sense of through people’s experiences of them. In conducting and presenting our analyses, we therefore privileged the perspectives and realities of the participants.

Prior to commencement, our collection and analyses of the qualitative data was approved by our institution’s Human Research Ethics Committee (number: [removed for peer review]). All participants were fully informed of the nature of the research and gave their informed consent prior to participating in an interview. Women in the programme were reassured that their participation in the research was entirely voluntary and had no bearing on their relationship with or access to housing and services. In appreciation of their contribution to the research, participating women received an AUD40 gift voucher at the first time point, and an AUD50 gift voucher at the second time point. Of utmost importance to our study is ensuring that participants’ identities and personal information remain confidential. For this reason, we have made the conscious decision to refrain from labelling interview excerpts with participant numbers, or any other potentially identifying information. Excerpts are thus simply labelled either ‘Tenant’ or ‘Practitioner’. Given the very small pool of potential participants within the SHP, as well as the high risk to the women should they be identified, we see this as a necessary step in maintaining participant confidentiality.

Findings

Setting them up to fail: housing instability driven by the private rental market

Drawing on both the qualitative interview and quantitative administrative data, here we analyse the inherent limitations of the private rental market, and illustrate how, in concert with IPV, they contribute to housing instability.

The SHP’s funding arrangements allowed properties to be subsidised at 25% of women’s income for the duration of their time in the programme. This subsidy meant that women’s housing costs were below the Australian threshold of housing financial stress (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, Citation2023). However, women experienced significant challenges because of the unpredictable duration of tenancy within the housing they were allocated. Although women were able to stay in the programme for its entire 5-year duration, interviews with tenancy practitioners indicated that the standard lease for women in the programme was generally only 12-months (sometimes shorter), which reflects the norm in the private rental market. Together, the qualitative and quantitative data indicated how frequently women were required to move tenancies during their time in the programme. The administrative tenancy data showed that the number of moves women made across the life of the programme ranged from a minimum of 0 (when the participant did not move) to 4 (when they moved 4 times). Drawing on the administrative tenancy data, 53% of women in the programme were required to move at least once after being housed through SHP. Of these women, 47% moved once, 29% moved twice, and 24% moved three or more times.

Although the quantitative administrative data is neither precise nor comprehensive, it does provide a reasonable indication of the range of reasons underpinning women’s moves between properties. The majority of these moves (47%) were made due to leases not being renewed after the initial 12 months (due to, for example, houses being sold or taken off the rental market). Other reasons for moving properties related to unresolved breaches of the tenancy agreement (20%), women leaving the programme (11%), and women changing tenancies due to IPV safety concerns (8%). As the women explain:

[The first house] there was threats made to me and the two children from [ex-partner’s] family. And then we had the move to [the second house]. Then [the second house] … the property’s getting sold by the real estate, we had to move it into [the third house] … When I got told I’m only going to be here for six months I’m like, ‘What? I thought this was going to be a family home for 12 months.’ (Tenant)

This is my third place … [The first one] was getting bought … [I was there] maybe two years. [The next one] five months max … Oh no, there was another place. I’ve had four sorry … the bathroom had started rotting, so I couldn’t stay there anymore. (Tenant)

[State housing authority] outsourcing of their houses, giving subsidy in this crazy rental market is not sustainable. And it sets families to fail. And then even if they don’t fail, like one family, tenancy wasn’t renewed, and then we keep moving and we keep moving families. (Practitioner)

During the interviews, women in the programme spoke at length about the importance of stability and being able to settle in one house for an extended period of time. For these women, continuity of tenure was seen as critical to enable them to plan ahead and ensure stability and continuity for their children.

This is the third place we’ve lived in now … the last place I was in, it was only for an 11-month lease … with kids in school and that, I don’t want to have to chop and change schools. (Tenant)

I really want to just get a, what is it, long-term house … That way I can get a swing set and everything, get all that … but now that I’m moving, I don’t know how big the other backyard will be. (Tenant)

Practitioners similarly spoke about the importance of women and their children being able to settle in one property, and the significant disruptions moving caused. In particular, practitioners explained how each time a woman moved house, her connections to family, community, support services, and children’s schools were broken. In these cases, women required significant support to rebuild these connections. For example:

Moving, moving, moving … that adds an extra layer to stability … a lot of the time they’re not moving just within the same suburb, they’re moving to new areas. So that’s resetting up community, resetting up schools, all of the connections, which are so important, which take time. (Practitioner)

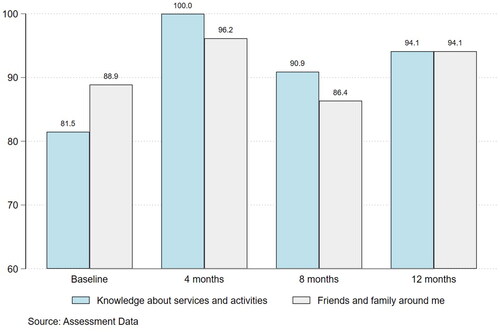

Drawing on the administrative assessment data, we observed improvements in community connections, such as knowledge about services and activities in the community for children and families, and having friends and family around, in the initial months of the programme. However, the follow up periods show fluctuations in reported community connection. shows an increase in knowledge about services and activities from 81.5% at baseline to 100% at the 4-month mark, which then drops to 90.9% at the next follow-up. Similarly, connections (i.e. having friends and family around) improved to 96.2% at the first follow-up but declined thereafter.

The interview data helps to contextualise this inconsistency in progression, and suggests that the loss of community connections resulting from moving houses may play a significant role. For example, one woman spoke explicitly about how she was able to build connections to the community in her first property, but struggled to do so after having to move to a new neighbourhood. Losing the relationships she had formed was difficult for her, and something she felt unable to rebuild:

I had a lovely neighbour … I sort of bonded to her. And she’d offer to pick the kids up if it was raining and whatnot, so that was good. There doesn’t feel like there’s that community in the street here. (Tenant)

Throughout the interviews, practitioners unanimously agreed that the continued instability experienced by women in the programme stemmed from the need to head-lease housing through the private rental market. The private rental market has many limitations in meeting the needs of women who experience IPV. These limitations are exacerbated by the current state of the private rental market, characterised by high demand, rising rents, low vacancy rates, and rapid value increases, which in turn increase the turnover of properties. As some practitioners explained, high demand for properties meant landlords had their pick of tenants, and viewed the women in the programme as too great a risk:

There’s definitely prejudice there with, I’d say, some of the real estate agents and property owners … the property owner has said, ‘Oh, they’re single with kids. Sorry, doesn’t that raise some red flags for you?’ (Practitioner)

I guess [landlords] know they’ve got their choice of tenants. So, obviously our tenants are not the top of anyone’s list, predominantly women with children. (Practitioner)

Along with the increased rents have come increased expectations from agents and/or owners about property condition. (Practitioner)

We need the property to be maintained to a certain level in order to keep the real estate happy in inspections. (Practitioner)

Part of the [SHP] role to support families to maintain their properties by building their capacity … But that’s pretty low down on the list in terms of things that the [SHP] team are working with families around. (Practitioner)

I think even the pressure of moving, the pressure of constantly having neighbour complaints or having conversations around property … they really do care and it’s a lot of pressure and they feel like they’re constantly failing. (Practitioner)

Sabotage and setbacks: housing instability driven by men’s behaviour

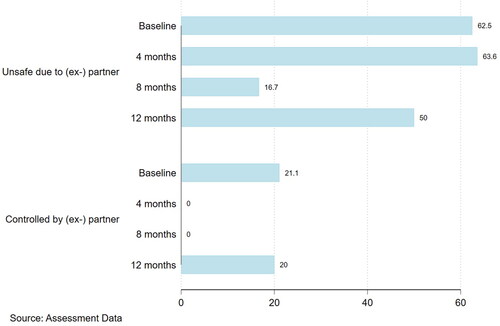

As well as the housing instability women experienced as a consequence of being housed through the private rental market, many women in the programme experienced both psychological and material housing instability that was driven directly by their (ex-)partner’s violent behaviour. For some women, psychological housing instability was experienced in the form of feeling unsafe in their homes. Drawing on the administrative assessment data, we analysed women’s feelings of safety during their time in the programme across two domains: feeling unsafe due to an (ex-)partner and feeling controlled by an (ex-)partner. As shown in , between baseline and the 8-month follow-up, the percentage of women feeling unsafe due to an (ex-)partner decreased from 62.5% to 16.7%. Similarly, the percentage of women feeling controlled by an (ex-)partner decreased from 21.1% to 0%. However, these percentages rose again considerably at the 12-month follow-up.

Our interviews with women in the programme provide some insight into why feelings of safety were short-lived. For example, some women spoke about anxiety around their ex-partners being due for release from prison after being incarcerated for IPV, while others spoke about their ex-partners locating them after a period of time:

[He’s been in prison for] a year now, yep. Due to get out again … with time served. (Tenant)

[Ex-partner] does know where I live now. He spotted me in [local shopping centre] and he shoved letters in my mailbox. (Tenant)

He actually went to prison because of everything … he’s out now … he actually breached his [protection] order already. (Tenant)

But it was continuous [IPV]. It was continuously happening. He breached his [protection] order many a times … He strangled me in front of the kids. (Tenant)

Now on a [protection order] … He told me he was in my house while I slept. I had a friend stay over and he’s like, “I can see him by the way. I’m standing over him.” (Tenant)

As well as—or, indeed, because of—this psychological housing instability some women also faced material housing instability within the programme by moving house when the risks to their safety became too high. As the women explained:

[I left my first unit] due to domestic violence. And I got another unit … that was great. And then had to leave that one again for domestic violence. (Tenant)

I was located again [by ex-partner] … I had my door kicked in twice and got to the point we had to pack up and move. We went to stay with my sister for a couple of weeks while the programme helped find another house for us. We just got into this one now. (Tenant)

In the interviews, the women spoke at length about the fear they were experiencing within their current tenancies and their strong desire to relocate for their and their children’s safety:

I’ve just gone through domestic violence and I rang [practitioner] to have a chat to her about what can I do, can I move into another property, and that’s out of the question … So I’ve got to stay put here now, where he knows where I live. (Tenant)

[My ex-partner is] due to get out [of prison] again … I’ve asked [SHP] to move me, but [practitioner’s] response is, it’s too hard. It’s too much. Too hard for her to get another place. (Tenant)

However, along with the multiple moves women made between properties within the programme, came mounting debt, often a result of the damage that (ex-)partners caused to properties during violent episodes. When damage was caused to a property, the tenancy manager paid for the damage to be fixed to the satisfaction of the real estate agent, and the costs of these repairs were then passed onto the women as debts to be repaid to the tenancy manager. It should be recognised that, in line with Queensland’s tenancy laws (Residential Tenancies Authority, n.d.), the tenancy manager did not pass on debts to women for property damage that was caused by IPV when this IPV was formally reported. For debts to be waived, however, women were required to disclose the IPV, which then triggered a formal reporting procedure through the Residential Tenancies Authority. The research literature strongly indicates that there are a range of reasons why women do not formally disclose IPV to authorities. Particularly pertinent for our sample include a fear of having their children removed by statutory child protection services, fear of retaliatory violence, and a lack of material resources (Rhodes et al., Citation2010; Robinson et al., Citation2021; Rose et al., Citation2011). Therefore, although formal procedures were in place to ensure that women were not required to pay for the damage caused by a perpetrator, there were significant barriers to achieving this in practice.

Also important to note is that although the costs were passed onto the women as debts, practitioners explained how the tenancy manager had low expectations for collecting the entirety of these debts, and outstanding debts were absorbed by the tenancy manager when women exited the programme. As one practitioner explained:

Some of our families are carrying a significant debt from property damage across multiple properties. We know they’re never going to be able to pay off the debt that they’re carrying with us, but it kind of hangs over their head. (Practitioner)

We’ve been found [by ex-partner] twice. So, I’m still paying off debts from both times where I’ve had to pay for the whole door to be replaced … When [ex-partner] kicked the door in, I had to replace it … I’m still paying that off. I just finished paying the last one off and then he did it again. (Tenant)

[Ex-partner] put holes through the place, like put me through the wall, everything. I paid for a guy to come out and fix it, it wasn’t good enough. It was a professional, wasn’t good enough. Then I got a debt because it wasn’t up to standard [and the tenancy manager paid to repair it again] … the total damages there was $1,800 I believe, plus whatever I paid to get it fixed anyway. (Tenant)

I’m worried about this and I’m worried about that. If I don’t do this right, if I don’t do what she says, am I going to get evicted? Do you know what I mean? Then what happens to me if I’m evicted? Am I on the street again with my kids and will Child Safety step in and take my children? (Tenant)

These findings demonstrate that by virtue of the programme’s eligibility criteria and reliance on the private rental market, the women accepted into SHP have high levels of vulnerability and are exposed to considerable challenges that are often outside of their control, including IPV. For women to be put into debt for the very reasons they require support is both unjust and unconducive to improving women’s housing stability outcomes. The findings also illustrate how men’s behaviour and the limitations of the private rental market interact to compound women’s experiences of housing instability, both material and—perhaps more importantly—psychological.

Discussion

We conducted a mixed-methods study that identified women’s experiences of housing instability in supportive housing within IPV contexts. We found that throughout their time in supportive housing, women continued to experience multiple forms of material and psychological housing instability. In terms of material housing instability, the most prevalent form of instability was transience due to frequent property moves, with some women only living in a property for several months before moving again. This transience was due to a range of factors, many of which related to the limitations of the private rental market in servicing the needs of a highly vulnerable group of women. The high demand—and cost—of the private rental market, along with a general disinclination to rent to low-income women with children, meant that the SHP faced significant difficulty sourcing properties for the women. When they were able to source properties, real estate agents had such high expectations for property maintenance that many practitioners felt the women were set up to fail. As a result, leases were often not renewed, and women were required to relocate at the end of each lease.

This material instability was closely linked with the psychological instability of frequently losing community connections and having to rebuild these connections and support networks after each move. Women also faced significant psychological housing instability through the lack of safety they felt within their own homes. This lack of safety was driven by their ex-partners, some of whom breached their protection orders by contacting or stalking the women. Even when ex-partners had not breached their orders, the possibility that they might was a constant concern for the women. Several women expressed a desire to move house because they felt unsafe, suggesting that for these women, the psychological stability that came with feeling safe was more important than the material stability of long-term tenancies. Numerous women spoke of the IPV that their (ex-)partners had committed against them in these homes, as well as the damage the men had caused to the properties. Because of the damage, the women were left with large debts to pay off, which contributed towards their financial stress and put their tenancies at risk. Our study thus demonstrates the importance of considering a range of rental market factors and how they interact with men’s use of intimate partner violence to influence women’s experiences of housing instability.

Implications for housing as a resource to keep women safe from IPV

Our research highlights two important implications for the limitations of housing and support models to keep women safe from IPV. First, the limitations identified in this research about the private rental market underscore the problems with the commodification of housing and how this commodity is ill equipped to support very low-income women to experience housing stability. As private landlords primarily use housing to generate wealth, in Australia’s extremely tight rental market women seeking access to supportive housing were routinely not viewed as ideal tenants. Even when subsidies enabled women to access the private rental market, the commodification of housing meant that property owners were frequently selling their assets to achieve significant capital gains in Australia’s expensive housing markets (Ryan-Collins & Murray, Citation2023). An asset that is used to speculate and leverage wealth is incongruent with a stable and affordable home.

The second implication is how supportive housing programmes are extremely limited in their ability to keep women safe from IPV – or stable in life – when IPV is ongoing. O’Campo and colleagues’ (2016) conceptual framework posited that over the longer term—that is, many months to a few years—psychological stability is improved as women experience less transience and a greater sense of safety in the home. It similarly posited that material stability increases as women experience greater access to good quality affordable housing. Our findings show that even after several years receiving dedicated housing and interdisciplinary support through supportive housing, women were still unable to achieve either form of housing stability on the private rental market. O’Campo et al. (Citation2016, p. 15) further argued that ‘mitigating psychological instability—issues of safety, promoting feelings of home, ensuring that new housing is a refuge—is often not considered when designing services for victims of violence.’ Our findings suggest that even a supportive housing programme with comprehensive inbuilt mechanisms for promoting the safety and psychological housing stability of women—such as by moving women to different properties, ensuring houses are secure, and supporting women to have protection orders put in place—faced considerable difficulty in keeping the women safe from the threat of men’s violence. This left the women with having to make trade-offs between psychological and material housing stability.

Implications for supportive housing programmes

Despite the myriad successes of supportive housing programmes for women experiencing IPV (Kuskoff et al., Citation2022; Sullivan et al., Citation2023; Wood et al., Citation2023), our findings clearly indicate that in the context of continued violence, women struggled to achieve material and psychological housing stability in the private rental market, even with ongoing housing and multidisciplinary supports. Drawing on our findings, we identify three key considerations for existing supportive housing programmes to help mitigate the barriers they face to supporting women to achieve housing stability in the context of IPV.

First, it is important for tenancy managers to engage deeply with the support providers they partner with to understand the individual circumstances and needs of women experiencing IPV, and to embed within their practices the understanding that IPV does not necessarily end once women are housed. As demonstrated in this study, many problems that are manifest as ‘tenancy problems’ are attributed to tenants’ experiences of IPV. It is not only property damage, but the fear and trauma associated with IPV that challenge one’s capacity to comply with tenancy requirements. Ongoing work is required on behalf of the tenancy manager to understand women’s changing safety and housing needs, as is the flexibility to respond to these needs.

Second, there is great potential to build protective mechanisms into supportive housing models to recognise and counter the limitations of the private rental market. For example, allocating funding specifically to cover the costs of damage caused by perpetrators—without the requirement that women formally report the violence to state-based tenancy authorities—could do much to relieve the stress and entrenchment of poverty that women experience in the context of mounting debts owed to the tenancy manager. Further, incentives to encourage landlords and real estate agents to lease their properties to women participating in such programmes could prove valuable for facilitating tenancy managers’ access to properties, and in turn their flexibility to respond to women’s psychological housing stability needs.

Third, there is potential for supportive housing programmes to consider alternative housing options, such as the use of social housing. While utilising social housing for supportive housing programmes will undoubtedly have its own limitations, it also has the potential to avoid some of the limitations we identify within the private rental market. For example, although some Australian social housing authorities have introduced leases for duration of need, in practice the majority of tenants have ongoing leases and security of tenure (Fitzpatrick & Pawson, Citation2014), thus minimising the disruption caused by tenants having to move at the end of each 1-year lease. Social housing is also targeted specifically towards the most vulnerable tenants, and does not rely on private landlords taking what they perceive as a risk by leasing their assets to low-income women experiencing IPV.

Limitations

It is important to consider these findings within the context of the study’s limitations, particularly as they pertain to diversity of experiences. Existing research shows that housing stability outcomes for victims of IPV can differ significantly between different racial groups (Engleton et al., Citation2022; Kulkarni & Notario, Citation2023). Approximately 50% of tenants in the study identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander—a significant racial minority in Australia. While our study captures the experiences of these women, given our small sample and our lack of engagement with racial background in the interviews, we were unable to explore how experiences differed according to racial background, and what impact this might have on housing stability. Future research would benefit from exploring how racial background interacts with and compounds issues of housing instability for women who experience IPV.

It is also important to consider our findings within the contexts and constraints of administrative data. Consistent with existing literature, the data we have access to does not have the depth to speak to specific—and indeed important—issues related to participants’ housing and IPV, such as breaches of tenancy agreements or participants’ reasons for exiting the programme. In terms of the latter, housing scholars have identified both the conceptual and data limitations to identifying tenancy exits and tenancy sustainment as indicators of either positive or negative outcomes (Taylor & Johnson, Citation2022). A comprehensive understanding of positive tenancy exits relies upon longitudinal data about housing pathways that is rarely available. Furthermore, the reasons for exits often available in housing administrative data, such as entering or ending a relationship, or unresolved breaches, conceals a range of complexities that are required to meaningfully determine whether an exit is positive or negative, including whether the positive or negative determination is arrived at by the tenancy manager or the tenant.

Conclusion

While supportive housing programmes can be experienced as highly valuable for enabling women to access housing on the private rental market, our research demonstrates that we must be cautious of what we can expect such programmes to achieve when it comes to IPV and housing stability. Although embedding protective mechanisms into the design of permanent supporting housing programmes may mitigate some of the issues arising from the private rental market, men’s ongoing use of violence is a complex factor that requires further investigation and an effective social and justice response. For as long as men continue to perpetrate violence, women will continue to feel unsafe in their homes and both material and psychological housing stability will remain out of reach.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the generosity of the Douglas Family Foundation in their financial contribution to enable this research. We also acknowledge the financial and in-kind contributions of Micah Projects, and the in-kind contributions of Common Ground Queensland.

Disclosure statement

The research on which this article is based was conducted as part of a commissioned study on the supportive housing program in question. Data collection and an independent report were funded in part by the not-for-profit organisations delivering the program, as well as philanthropic donations. No additional form of support was provided from these organisations, and the lines of inquiry pursued in our analyses here were undertaken independently of the original study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ella Kuskoff

Ella Kuskoff is a Research Fellow at The University of Queensland. Her research focuses on social and policy responses to inequality and disadvantage, and how these responses may be changed to more effectively address social issues. Her particular areas of interest include domestic violence, gender, and homelessness.

Nikita Sharma

Nikita Sharma is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at The University of Queensland. Her research focuses on inequality-related topics that are highly relevant to policy, government and industry. Specifically, she works on migration, gender, public service delivery, inclusion in the labour market and wellbeing.

Rose-Marie Stambe

Rose-Marie Stambe is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at The University of Queensland. Her area of expertise lies in qualitative research methods, particularly ethnography. She has dedicated her research efforts to investigating how policy, institutional practices, and systems impact the lives of individuals who face social and economic marginalisation. Rose’s primary focus is to understand the intricate dynamics between policy, institutional practices, and the lived realities of marginalised individuals.

Stefanie Plage

Stefanie Plage is a Research Fellow at The University of Queensland. Her expertise is in qualitative research methods, including longitudinal and visual methods. Her research interests span the sociology of emotions, disadvantage and health and illness. Currently, her research seeks to understand and improve the interactions of families experiencing social disadvantage with the social and health care systems.

Cameron Parsell

Cameron Parsell is a Professor at The University of Queensland. His work examines multiple forms of exclusion and social harms. His research focuses on the nature and experience of poverty, homelessness, and domestic and family violence. He is interested in understanding what societies do to respond to these problems, and what societies ought to do differently to address them.

References

- Adams, E., Clark, H., Galano, M., Stein, S., Grogan-Kaylor, A. & Graham-Bermann, S. (2021) Predictors of housing instability in women who have experienced intimate partner violence, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, pp. 3459–3481.

- Airgood-Obrycki, W., Hermann, A. & Wedeen, S. (2022) “The rent eats first”: Rental housing unaffordability in the United States, Housing Policy Debate, 33, pp. 1272–1292.

- Anglicare Australia (2023) Rental Affordability Snapshot – National Report 2023 (Ainslie, Australian Capital Territory: Anglicare Australia).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Housing Affordability. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/housing-affordability (accessed 16 April 2024)

- Baker, C., Billhardt, K., Warren, J., Rollins, C. & Glass, N. E. (2010) Domestic violence, housing instability, and homelessness: A review of housing policies and program practices for meeting the needs of survivors, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, pp. 430–439.

- Barata, P. & Stewart, D. (2010) Searching for housing as a battered woman: Does discrimination affect reported availability of a rental unit?, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, pp. 43–55.

- Blunden, H. & Flanagan, K. (2022) Housing options for women leaving domestic violence: The limitations of rental subsidy models, Housing Studies, 37, pp. 1896–1915.

- Bomsta, H. & Sullivan, C. (2018) IPV survivors’ perceptions of how a flexible funding housing intervention impacted their children, Journal of Family Violence, 33, pp. 371–380.

- Connelly, R., Playford, C. J., Gayle, V. & Dibben, C. (2016) The role of administrative data in the big data revolution in social science research, Social Science Research, 59, pp. 1–12.

- Daoud, N., Matheson, F. I., Pedersen, C., Hamilton-Wright, S., Minh, A., Zhang, J. & O’Campo, P. (2016) Pathways and trajectories linking housing instability and poor health among low-income women experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV), Women & Health, 56, pp. 208–225.

- Engleton, J., Sullivan, C. M. & Hamdan, N. (2022) Exploratory examination of how race and criminal record relate to housing instability among domestic violence survivors, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37, pp. NP21400–NP21410.

- Fetters, M., Curry, L. & Creswell, J. (2013) Achieving integration in mixed methods designs: Principles and practices, Health Services Research, 48, pp. 2134–2156.

- Fitzpatrick, S. & Pawson, H. (2014) Ending security of tenure for social renters: Transitioning to ‘ambulance service’ social housing?, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 597–615.

- Frederick, T. J., Chwalek, M., Hughes, J., Karabanow, J. & Kidd, S. (2014) How stable is stable? Defining and measuring housing stability, Journal of Community Psychology, 42, pp. 964–979.

- Gezinski, L. & Gonzalez-Pons, K. (2021) Unlocking the door to safety and stability: Housing barriers for survivors of intimate partner violence, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, pp. 8338–8357.

- Gilroy, H., McFarlane, J., Maddoux, J. & Sullivan, C. (2016) Homelessness, housing instability, intimate partner violence, mental health, and functioning: A multi-year cohort study of IPV survivors and their children, Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 25, pp. 86–94.

- Hetling, A., Dunford, A. & Botein, H. (2020) Community in the permanent supportive housing model: Applications to survivors of intimate partner violence, Housing, Theory and Society, 37, pp. 400–416.

- Kulkarni, S. J. & Notario, H. (2023) Trapped in housing insecurity: Socioecological barriers to housing access experienced by intimate partner violence survivors from marginalized communities, Journal of Community Psychology, 52, pp. 439–458.

- Kuskoff, E., Parsell, C., Plage, S., Ablaza, C. & Perales, F. (2022) Willing but unable: How resources help low-income mothers care for their children and minimise child protection intervention, The British Journal of Social Work, 52(7), pp. 3982–3998.

- Kuskoff, E., Parsell, C., Plage, S., Perales, F. & Ablaza, C. (2023) Of good mothers and violent fathers: Negotiating child protection interventions in abusive relationships, Violence Against Women. doi: 10.1177/10778012231158107

- Jeffrey, N. & Barata, P. (2017) When social assistance reproduces social inequality: Intimate partner violence survivors’ adverse experiences with subsidized housing, Housing Studies, 32, pp. 912–930.

- O’Campo, P., Daoud, N., Hamilton-Wright, S. & Dunn, J. (2016) Conceptualizing housing instability: Experiences with material and psychological instability among women living with partner violence, Housing Studies, 31, pp. 1–19.

- Office of National Statistics (2023) Housing affordability in England and Wales: 2022. Office of national statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationand community/housing/bulletins/housingaffordabilityinenglandandwales/2022 (Accessed November 2023)

- Padgett, D. (2017) Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research, 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks: Sage).

- Pavao, J., Alvarez, J., Baumrind, N., Induni, M. & Kimerling, R. (2007) Intimate partner violence and housing instability, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32, pp. 143–146.

- Residential Tenancies Authority (n.d) Domestic violence in a rental property. Available at: https://www.rta.qld.gov.au/domestic-violence-in-a-rental-property (accessed 9 April 2024)

- Rhodes, K., Cerulli, C., Dichter, M., Kothari, C. & Barg, F. (2010) “I didn’t want to put them through that”: The influence of children on victim decision-making in intimate partner violence cases, Journal of Family Violence, 25, pp. 485–493.

- Robinson, S., Ravi, K. & Voth Schrag, R. (2021) A systematic review of barriers to formal help seeking for adult survivors of IPV in the United States, 2005–2019, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22, pp. 1279–1295.

- Rog, D., Marshall, T., Dougherty, R., George, P., Daniels, A., Ghose, S. & Delphin-Rittmon, M. (2014) Permanent supportive housing: Assessing the evidence, Psychiatric Services, 65, pp. 287–294.

- Rollins, C., Glass, N., Perrin, N. A., Billhardt, K., Clough, A., Barnes, J., Hanson, G. & Bloom, T. (2012) Housing instability is as strong a predictor of poor health outcomes as level of danger in an abusive relationship: Findings from the SHARE study, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, pp. 623–643.

- Rose, D., Trevillion, K., Woodall, A., Morgan, C., Feder, G. & Howard, L. (2011) Barriers and facilitators of disclosures of domestic violence by mental health service users: Qualitative study, British Journal of Psychiatry, 198, pp. 189–194.

- Ryan-Collins, J. & Murray, C. (2023) When homes earn more than jobs: the rentierization of the Australian housing market, Housing Studies, 38, pp. 1888–1917.

- Sullivan, C. M., Guerrero, M., Simmons, C., López-Zerón, G., Ayeni, O. O., Farero, A., Chiaramonte, D. & Sprecher, M. (2023) Impact of the domestic violence housing first model on survivors’ safety and housing stability: 12-month findings, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38, pp. 4790–4813.

- Taylor, S. & Johnson, G. (2022) Sustaining Tenancies: Issue and Challenges for Social Housing Providers (Melbourne: Unison Housing).

- Wood, L., Schrag, R. V., McGiffert, M., Brown, J. & Backes, B. (2023) “I felt better when I moved into My own place”: Needs and experiences of intimate partner violence survivors in rapid rehousing, Violence against Women, 29, pp. 1441–1466.

- Woodhall-Melnik, J., Hamilton-Wright, S., Daoud, N., Matheson, F. I., Dunn, J. R. & O’Campo, P. (2017) Establishing stability: Exploring the meaning of ‘home’ for women who have experienced intimate partner violence, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32, pp. 253–268.

- Yuan, Y., Padgett, D., Thorning, H. & Manuel, J. (2023) “It’s stable but not stable”: A conceptual framework of subjective housing stability definition among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders, Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 19, pp. 111–123.