?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper presents the first study to investigate ethnic differential treatment in public housing through a correspondence test field experiment. The experiment involved sending inquiries from fictitious couples with Swedish or Arabic names to all public housing companies in Sweden. Four outcomes were examined: whether the public housing companies responded to the inquiries, whether they initiated their response with a greeting, whether they had a priority system in place, and whether they provided information about problematic neighborhoods. The findings revealed disparities in the treatment of the couples. The Swedish couple received greetings and information about problematic neighborhoods at a greater rate than the Arab couple. This study contributes to existing literature on ethnic differences in the housing market by providing evidence of differential treatment within the public housing sector. Additionally, it explores the content and quality of public housing companies’ responses, offering valuable insights for policymakers and housing professionals in designing interventions to promote equality and counteract differential treatment.

Introduction

The evolution towards a more multicultural world has recently intensified the focus on societal differences and biases (Dovidio et al., Citation2010; Solomos, Citation2020). Housing, a fundamental human right and a basic need, is one area where such disparities can have far-reaching consequences. Differential treatment in housing can significantly impact individuals and communities, leading to socioeconomic and spatial segregation, perpetuating inequality, and undermining social cohesion (Galster, Citation1992). Despite considerable developments made in legislation to ensure equality in the Western world (European Commission, Citation2013; Schwartz, Citation2021; Silver & Danielowski, Citation2019), recent syntheses of field experiments on ethnic differences in the housing market persistently underscore a pressing problem with the differential treatment of ethnic minorities, worthy of further and deeper examination (Auspurg et al., Citation2019; Bertrand & Duflo, Citation2017; Flage, Citation2018; Quillian et al., Citation2020).

The meta-analysis conducted by Flage (Citation2018) examined 25 field experiments spanning from 2006 to 2017 in OECD countries, revealing evidence of differential treatment of ethnic minorities in the rental housing market. Notably, individuals with Arabic-sounding names experienced particularly widespread and deeply ingrained differential treatment. This study indicates that applicants with Arabic-sounding names must submit approximately twice as many apartment applications as their counterparts from the majority population to receive similar responses from the landlords. Another meta-analysis by Auspurg et al. (Citation2019) examined 71 field experiments conducted between 1973 and 2015 in ten countries in the Western world. Their findings demonstrate consistent differential treatment of ethnic minority groups, who receive fewer responses or viewing invitations when applying for available rental apartments compared to the majority group. Their research also highlights that individuals with Arabic-sounding names face slightly higher levels of differential treatment than other minority groups. These meta-analyses collectively emphasize the pervasiveness of differential treatment in housing and the urgent need for policy interventions to address these deeply rooted biases around the globe.

This paper directs attention toward the public housing sector as the primary subject of investigation. To the best of our knowledge, no prior research has investigated the potential existence of ethnic differences in treatment within the public housing sector. Studying ethnic differences in treatment by public housing companies is critically important due to these organizations’ unique role in society. If ethnic minorities encounter differential treatment while seeking accommodation in the private housing market, they are often compelled to resort solely to the public housing sector. As a key component of the welfare state, public housing is designed to provide affordable, safe, and decent living conditions for all citizens, regardless of socioeconomic status or ethnic background. In many societies like Sweden, it is the primary housing option for marginalized or low-income populations. Consequently, if differential treatment is present in this sector, it can exacerbate existing social inequalities, impeding marginalized ethnic groups’ access to one of life’s necessities; a home. Furthermore, differential treatment in public housing can contribute to residential segregation, a divisive phenomenon associated with myriad social problems, such as deprived neighborhoods and reduced access to quality education, job opportunities, and essential services. Studying ethnic differences in treatment in this sector is therefore crucial for ensuring equity in housing and promoting broader societal integration and cohesion.

We conducted a correspondence test field experiment to explore potential ethnic differences in treatment by public housing companies in Sweden. Posing as fictitious couples with Arabic- and Swedish-sounding names, we emailed all Swedish public housing companies carefully matched inquiries. As the standard application process for public housing in Sweden requires providing detailed personal information like social security numbers, which are impossible to falsify, we deviated from the conventional direct application approach typical in correspondence test experiments. This may also explain the lack of prior evaluations of public housing companies. Our inquiries instead posed two questions: whether the company had a priority system for newcomers to the area and whether they could offer insights about ‘bad’ neighborhoods to avoid. We then analyzed four binary outcomes: if the public housing companies responded to the inquiries, if they initiated their response with a greeting, if they had a priority system in place, and if they offered information about problematic neighborhoods. All inquiries were identical apart from the couples’ names, enabling us to isolate the influence of perceived ethnicity on the companies’ responses and the content therein.

The correspondence test field experiment is a widely used method in social sciences for detecting differential treatment, facilitating direct comparison of responses based on manipulated characteristics (Gaddis, Citation2018). Our decision to employ Arabic- and Swedish-sounding names in our study was influenced by prior research on ethnic differences in treatment in the Swedish housing market (but also in other European countries). These past studies have consistently demonstrated that applicants with Arabic-sounding names must apply to at least twice as many vacant apartments compared to their counterparts with Swedish-sounding names to receive a similar number of invitations to view available units (Ahmed et al., Citation2010; Ahmed & Hammarstedt, Citation2008; Bengtsson et al., Citation2012; Carlsson & Eriksson, Citation2014; Molla et al., Citation2022).

The contributions of this study are noteworthy for several reasons. First, it provides empirical evidence of the extent and nature of ethnic differential treatment in the public housing sector, essential to social welfare and integration. It is the first to specifically investigate ethnic differential treatment by public housing companies using a field experiment, adding a fresh perspective to the literature on differential treatment in housing. Second, this study expands our understanding of differential treatment in housing, not merely limited to whether an inquiry receives a response but delving into the content and quality of the response, such as a personal greeting and sharing critical information about the housing market. This nuanced approach paints a more comprehensive picture of differential treatment in the housing sector, leading to valuable insights. Finally, it provides valuable insights for policymakers and housing professionals to design effective interventions that promote equality and counteract unfair differential treatment practices.

Theoretical framework

Understanding the root causes and manifestations of differential treatment against ethnic minorities in the housing market is essential for effectively designing, implementing, and interpreting empirical studies. This discussion briefly outlines some prevalent theoretical frameworks in the literature on ethnic differential treatment in the housing market. Before delving into these frameworks, it is important to clarify our use of terminology. This paper consistently refers to ‘differential treatment’, which captures a wider spectrum of behaviors than ‘discrimination’. For simplicity, we do this even in cases where the term ‘discrimination’ would have been appropriate. This approach is taken to prevent any misunderstanding between legal terminology and the theoretical and empirical aspects under study, following the discussion by Banton (Citation2011). Here, ethnic differential treatment refers to the unfair or unfavorable treatment of housing applicants from ethnic minorities despite having qualifications identical to those of applicants from the ethnic majority.

The notion of differential treatment based on tastes traces back to Becker’s (Citation1957) seminal work, highlighting personal preferences in social interactions. This theory suggests that individuals derive satisfaction from associating with preferred groups and discomfort from those they dislike. Even slight preferences can significantly lead to taste-based differential treatment (Lang & Lehmann, Citation2012). When based on observable characteristics like skin color, ethnicity, or religion, such preferences can lead to differential treatment practices in housing. Housing companies displaying animosity towards ethnic minorities may favor applicants from the ethnic majority, resulting in less favorable housing possibilities for the disadvantaged ethnic group. This form of differential treatment can be direct, stemming from the housing companies’ biases, or indirect, where housing companies act on the biases of current tenants.

Another key theoretical approach suggests that differential treatment is based on statistical inferences, as rooted in the works of Phelps (Citation1972) and Arrow (Citation1973). This theory posits that without complete information about individual applicants, housing companies may rely on group-level stereotypes, such as employment status or income, to make decisions. This leads to a preference for applicants from the ethnic majority based on perceived risks, regardless of the accuracy of these stereotypes. The persistence of stereotypes can result in long-term and self-reinforcing adverse differential treatment (Coate & Loury, Citation1993).

Theories also distinguish between explicit bias, implicit bias, and institutional structures as sources of differential treatment practices (Tileagă et al., Citation2022). Explicit bias involves conscious prejudices leading to unequal treatment (Clarke, Citation2018), while implicit bias is unconscious prejudices subtly influencing decisions (Berndt Rasmussen, Citation2020). Institutional structures, meanwhile, perpetuate disparities through established practices or norms that inadvertently favor the ethnic majority (McCrudden, Citation1982). In public housing, these biases could manifest in various ways, including differential responses to inquiries, biased interactions, or unequal access to important housing information based on the perceived ethnicity of prospective tenants. This comprehensive approach underscores the complexity of addressing differential treatment in the housing market.

Prior literature

Much of the research on ethnic differential treatment in the housing market has primarily concentrated on two minority groups: differential treatment against Black individuals in the USA and people with Arabic-(Muslim)-sounding names in European countries. Sweden has indeed witnessed an increased focus on the differential treatment of Arabs and the issue of Islamophobia related to housing in recent years. This enhanced attention is not only evident in academic circles, where researchers employ a variety of perspectives and methodologies to shed light on these issues (Ahmed, Citation2015; Malmö mot Diskriminering, Citation2022; Oxford Research, Citation2013), but also in the media landscape, which has amplified discussions surrounding harmful and unfair differential treatment (Wirtén, Citation2022; Ziegerer et al., Citation2022).

The field of experimental research into the differential treatment of Arabs in the housing market originated with the work of Ahmed & Hammarstedt (Citation2008) in Sweden. Since then, the scope of research has expanded across European countries, offering diverse insights into ethnic differential treatment within the housing sector. This discussion will primarily focus on studies conducted in Sweden.

Ahmed & Hammarstedt’s (Citation2008) initial study set the groundwork by illustrating the differential treatment towards applicants with Arabic-sounding names compared to those with Swedish-sounding names, revealing a stark disparity in the positive response rates from landlords. This disparity was further explored in a subsequent study by Ahmed et al. (Citation2010), which introduced variations in the information provided in the rental inquiries. Their findings suggested that even when additional background information was provided, the gap in positive responses between applicants with Arabic-sounding and Swedish-sounding names persisted, indicating a deeply ingrained bias.

Further contributions to this body of research were made by Bengtsson et al. (Citation2012), who extended the investigation to include gender dimensions of differential treatment, and Carlsson & Eriksson (Citation2014), whose comprehensive study across Sweden further solidified evidence of widespread differential treatment against both men and women with Arabic-sounding names. Most recently, Molla et al. (Citation2022) revisited the issue, affirming the persistence of differential treatment practices over a decade after the first study of Ahmed & Hammarstedt (Citation2008).

Ahmed and Nsabimana (forthcoming) pursued an exciting avenue of exploration by differentiating between the effects of being Arab and Muslim. This distinction is significant, as previous studies used names that sounded both Arabic and Muslim, not just Arabic, in their experiments. Their work provides nuanced insights into the specificities of differential treatment in the housing market, presenting clear evidence of intersectionality in the Swedish housing market.

The Swedish findings are not isolated. Flage (Citation2018) and Auspurg et al. (Citation2019) provided meta-analyses of field experiments globally, indicating a widespread phenomenon of unfair and harmful differential treatment of people with Arabic-sounding names in the housing market. Studies conducted in Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Norway, Spain, and the USA have mirrored the Swedish results, highlighting a universal challenge. These international studies collectively highlight the disadvantages faced by individuals with Arabic-sounding names, especially men, as well as by other ethnic groups, in securing housing.

In conclusion, the existing research on differential treatment against individuals with Arabic-sounding names and other ethnic minorities in the housing market has significantly enhanced our understanding of this complex issue. These studies have collectively highlighted the persistent and pervasive nature of unfair and harmful ethnic differential treatment in the housing market. However, a notable gap in Swedish and international research is the need for more focus on public housing. Most studies, including those conducted in Sweden, have primarily focused on private landlords, leaving the practices of municipal and state-owned housing companies less explored. This oversight highlights a critical area for further research, given the significant portion of rental apartments managed by these entities in Sweden and potentially also in other countries. Addressing this gap is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of differential treatment in the housing market and for developing targeted interventions in the public housing sector.

Institutional context

Unlike social housing, which is mainly reserved for households with limited resources or targeted groups such as youths, seniors, disabled persons, etc., public housing is a tenure form available to all citizens. However, many countries have various housing policies closely associated with social housing, even if they are not officially defined as such (Pittini & Laino, Citation2011). These policies aim to provide special support to low-income and disadvantaged households. Sweden stands out among the few countries with a housing policy designed to be inclusive without targeting specific groups. The Swedish public housing system aims to elevate housing to a social right rather than a purely private matter (Borelius & Wennerström, Citation2009). This intention is reflected in its Swedish name, ‘allmännytta’, which translates to ‘for the benefit of everybody’ (Pittini & Laino, Citation2011).

The public housing system in Sweden is unique in that it aims to provide affordable housing accessible to vulnerable groups while maintaining high standards that are suitable for everyone. Its design ensures that individuals and families of all income levels, ethnicities, ages, and household types can access public housing without any associated stigma (Malmberg et al., Citation2004). Public housing offers several advantages, including manageable housing costs and comfortable living conditions without the responsibility for maintenance or capital risk. Additionally, it allows households to easily relocate within municipalities in response to changes in their life cycle or employment opportunities.

The responsibility for producing and providing rental dwellings that are accessible to all is delegated to the municipalities in the Swedish public housing system. As a result, nearly all 290 municipalities have at least one municipal housing company. These companies operate as non-profit limited companies with a mandate to actively fulfill social responsibilities while competing with private housing providers on an equal footing. Consequently, these public housing companies are expected to maintain a diverse tenant mix, offer rental dwellings in various districts within the municipality, and have a similar social composition as the private rental sector (Turner, Citation2006; Turner & Whitehead, Citation2002). By establishing their own housing companies, municipalities can foster new housing development while enhancing their competitiveness in attracting job opportunities and a skilled labor force.

The public housing system in Sweden is regulated by law (Swedish Code of Statutes, Citation2010:879). According to the act, the municipal housing companies should manage properties with rental apartments for ‘public utility’, promote housing supply in their respective municipalities, and offer tenants the opportunity for influence both in their housing and in the company itself. The public utility purpose involves a societal responsibility, while the companies’ operations should be conducted in a commercially viable manner.

The allocation of public housing in Sweden is generally governed by each company’s queue system, where individuals sign up and accrue waiting time to rent available apartments. This system is primarily managed by municipal entities or public housing authorities, emphasizing a first-come, first-served principle. Applicants increase their chances by accumulating queue time, which is crucial in high-demand areas where the wait for an apartment can be extensive. While some municipalities offer free registration, others may require an annual fee to maintain one’s place in line. This structured approach aims to distribute affordable housing options transparently and equitably across the population.

According to Public Housing Sweden (Sveriges Allmännytta), an industry and interest organization for public housing companies, Sweden presently has over 300 municipal housing companies with more than 850,000 apartments, representing almost 50% of the rental sector in Sweden (Public Housing Sweden, Citation2019). Hence, almost 700,000 households (or roughly 1.5 million people), accounting for approximately 15% of the households (or the population) in Sweden, reside in public housing units (Statistics Sweden, Citation2023).

Drawing on the insights provided by Grander (Citation2023), it becomes evident that ethnic minorities in Sweden are disproportionately represented in public housing. According to one standard, though contentious, definition of foreign background—comprising individuals born abroad or born in Sweden to parents who were born abroad—half of the inhabitants in public housing fall under this category. This starkly contrasts with the national average, where approximately 25% of the population shares a similar background. Such figures not only underscore the overrepresentation of ethnic minorities in public housing but also illuminate the pivotal role public housing plays in the lives of these communities. Given this context, public housing emerges not merely as a matter of accommodation but as a critical foundation for supporting the integration, stability, and well-being of ethnic minorities. Therefore, it is imperative that public housing remains free from differential treatment based on ethnicity, ensuring that all individuals have equal opportunities and access to this crucial support system.

Over the years, however, Sweden’s public housing sector has undergone significant changes (Christophers, Citation2013; Grander, Citation2023). Historically, public housing in Sweden was a cornerstone of the country’s commitment to universal housing policies. This approach ensured access to housing for all, based on principles that extended beyond financial means, thus benefiting the entire population, not just the economically disadvantaged. However, recent shifts have moved from this regulated framework to a more neoliberal model (Christophers, Citation2013). This shift is marked by deregulations and policy adjustments that undermine the sector’s universal character, making it increasingly difficult for municipal housing companies to assist households in financial difficulty. These modifications have led to more pronounced housing shortages in cities, exacerbated affordability problems, and raised concerns about growing segregation (Grander, Citation2023).

Sweden upholds a legal framework that prohibits discrimination in the housing market based on ethnicity, underscoring the country’s commitment to equality and justice (Swedish Code of Statutes, Citation2008:567). This legislation encompasses direct and indirect forms of discrimination, ensuring comprehensive individual protection. Direct discrimination might manifest when a housing provider denies someone an apartment due to the ethnic composition of a neighborhood, explicitly sidelining applicants based on ethnicity. Meanwhile, indirect discrimination occurs through subtler means, such as withholding information or creating uneven playing fields that inadvertently disadvantage certain ethnic groups. Furthermore, the Equality Ombudsman in Sweden ensures compliance with anti-discrimination laws and safeguards fair treatment in the housing market.

Method

Sample

We collected a list of all public housing companies in Sweden from the website of the national organization of public housing companies in Sweden – Public Housing Sweden – on January 17, 2022 (https://www.sverigesallmannytta.se/). The list consisted of 309 companies that provided public housing in Sweden. We excluded public housing companies that did not provide a contact email address or were specialized in housing for students, seniors, and disabled people. After these selections, we ended up with 287 companies. Another 16 companies were removed during the field experiment, for the most part, because of email delivery failures. Hence, the field experiment was based on a final sample of 271 public housing companies.

Materials

We constructed a letter of inquiry that we could send to public housing companies through email from fictitious heterosexual couples interested in the availability of rental housing and residential safety in the municipality. We opted to use fictitious couples rather than individuals in our correspondence tests. This choice was motivated by a desire to avoid the potential confounding effects of gender on the outcomes of our study. Considering the relatively small population of public housing companies in Sweden, minimizing variables that could introduce additional complexity to the analysis was crucial. By utilizing couples, we aimed to isolate ethnicity as the primary variable of interest, thereby reducing the potential for gender-based variability to influence the results. This methodological decision enhanced the interpretability of our findings, allowing for a more straightforward examination of ethnic differential treatment within the Swedish public housing sector.

The fictitious couples that made the inquiries to the public housing companies were randomly assigned either typical Swedish- or Arabic-sounding names. The couple with typical Swedish-sounding names consisted of Andreas and Karina Pålsson, and the couple with typical Arabic-sounding names consisted of Mohamed and Fatima Hassan. The names for the fictitious couples were chosen somewhat intuitively but with insights drawn from name statistics at Statistics Sweden to ensure they occur regularly in the Swedish population and earlier field experiments on differential treatment against people with Arabic-sounding names in various contexts (Ahmed et al., Citation2010; Ahmed & Hammarstedt, Citation2008; Carlsson & Eriksson, Citation2014).

Both first names and surnames had the same number of syllables: three for first names and two for surnames. The aim was to standardize the ease of pronunciation and the initial perception of the names used in our study. Research indicates that the ease with which a name can be pronounced can significantly influence judgments and evaluations of individuals (Laham et al., Citation2012). By ensuring that the names for both couples were similar in length and syllable count, we aimed to minimize any biases that might arise from the complexity or familiarity of the names. This approach helped to isolate the effect of perceived ethnicity from other potential influences related to name characteristics, ensuring that any differential treatment observed is more directly attributable to the ethnic implications of the names rather than their pronounceability or length.

It is essential to acknowledge that the recognition and associations triggered by these names may not be strictly confined to ethnic origins. This is due to the multifaceted nature of names, which can also convey signals of age, socio-economic status, religiosity, and immigrant status. While we posited that the chosen names are emblematic of their respective ethnic groups and unlikely to be significantly associated with specific socio-economic variables or age brackets due to their prevalence, we recognize that this approach does not encapsulate the full spectrum of variables that names might signal to respondents. Furthermore, the decision to employ a singular pair of names to represent each ethnic group was driven by the constraints of a small sample size rather than an assertion that these names comprehensively represent the entirety of their respective populations. This choice, we acknowledge, introduces a limitation to the external validity of our findings, as it cannot be presumed that the observed responses to these names can be generalized across all possible names within each ethnic category. Such an approach might not capture the nuanced perceptions and biases toward the diversity of names within each ethnic group, potentially leading to a conflated or oversimplified interpretation of ethnic biases. Our findings, therefore, should be interpreted with an understanding of these limitations as we contribute to the ongoing discourse on the measurement of ethnic bias and the challenges inherent in capturing its complexities within the constraints of experimental research design.

The framing of the letter of inquiry from the fictitious couple was as follows: The couple stated that they were moving into the municipality where the public housing company operated. The letter consisted of two specific questions. First, the couple asked whether the public housing company had a priority system for newcomers in the municipality. Second, they asked the public housing company whether there were any insecure residential areas in the municipality that the couple should avoid.

Our field experiment did not directly apply to any apartments as is usually done when studying differential treatment against vulnerable people in the private rental housing market. This would not have been possible in our experiment since public housing companies require applicants to register before applying to any apartments. This registration entails identifying yourself through your name, social security number, address, phone number, and, in most cases, via eID, which is difficult to fake in a field experiment. Refining our methodological approach, we consider our study an extension of previous field experiments. Unlike the traditional method, which involves directly applying for housing, our approach not only overcomes the practical limitations inherent in accessing the public housing sector but also enriches the research landscape. It provides a unique lens for examining ethnic differential treatment. Our study adds to the body of knowledge by uncovering subtle forms of differential treatment that might be less readily apparent through more conventional methods. This innovative adaptation highlights the added value of our research and underscores the potential for future studies to build on this methodology.

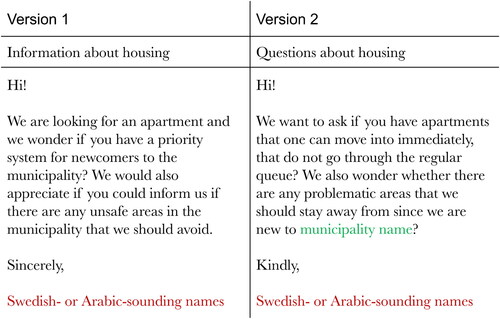

Since we used a within-subject (matched) design (i.e. two inquiries, one from the Swedish couple and one from the Arab couple, were sent to each public housing company), we constructed two versions of the inquiry letter by varying the wording and the construction of the sentences. illustrates the English translation of the two versions of the inquiry letters used in the field experiment. An email account was created for each couple through which the public housing companies’ inquiries and responses could be sent and received.

Figure 1. Letter of inquiry.

Note: English translation of the two original letters of inquiry in Swedish sent from the fictitious couples to the public housing companies. The first version of the letter was used for all inquiries on January 18, 2022, and the second version was used for all inquiries on April 2, 2022. The names of the couples (marked red in the figure) were randomly assigned in the first stage of mailing and alternated in the second stage. In the second version of the letter, the actual name of a municipality (marked green in the figure) was given.

Procedure

We used a within-subject (matched) design, where two inquiries, one from the Swedish couple and one from the Arab couple, were sent to each public housing company. In order to avoid detection, we sent one inquiry to all public housing companies on January 18, 2022. In this stage, the couple’s ethnicity was randomly assigned to each inquiry, and the first version of the inquiry in was used for all correspondence. A second batch of inquiries was sent two months later, on April 2, 2022. The assigned ethnicity of the couples was reversed in the second stage of mailing from the one randomly set in the first stage so that each public housing company received an email inquiry from an Arab and a Swedish couple during the entire field experiment. The second version of the letter of inquiry in was used in all correspondence in the second stage.

Responses from the public housing companies were then recorded as dichotomous outcome variables. We defined four outcome variables. The first outcome, Email reply, indicated whether a public housing company responded to a fictitious couple with a nonautomated letter, regardless of the letter’s content. The second outcome, Greeting, indicated whether a public housing company initiated its response to the couple with a personal salutation, for example, ‘Hi Mohamed and Fatima’ or ‘Dear Andreas and Karina’. The last two outcome variables constituted public housing companies’ answers to the two questions in the email inquiry, respectively. Hence, the third outcome, Cut in line, reflected whether a public housing company answered that they had some priority system for newcomers in the municipality. Finally, the fourth outcome, Bad zones, reflected whether the public housing company informed the couple about areas to avoid in the municipality. The explanatory variable was the couple’s ethnicity, randomly assigned in the field experiment, i.e. whether the couple had Swedish- or Arabic-sounding names. The definitions of all variables are provided in .

Table 1. Definitions of variables.

The experiment was preregistered at AsPredicted (https://aspredicted.org/yf5rk.pdf), and the data supporting this paper’s findings are openly available in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10968064). Data were analyzed using non-parametric tests for paired data and regression analysis, with the alpha level set at 0.10. Ethics approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority was not required by §§3–4 of the Ethical Review Act in Sweden (Swedish Code of Statutes, Citation2003:460), as no personally identifiable information about any physical individual was collected during the experiment.

Results

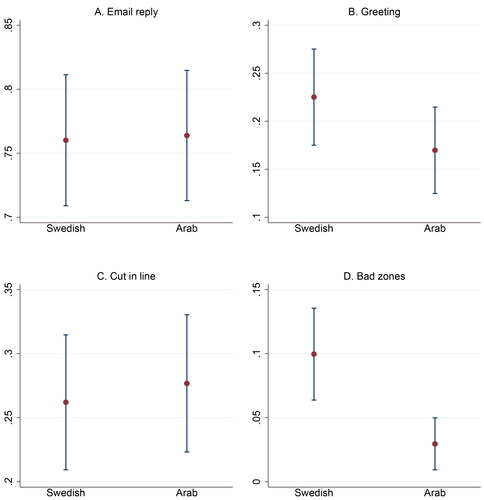

In line with our preregistered hypotheses, we examined whether there were any differences between the couple with the Swedish-sounding names and the couple with the Arabic-sounding names in the probability of receiving a positive outcome for each of our four outcome variables (Email reply, Greeting, Cut in line, and Bad zones) from public housing companies in response to the couples’ inquiries. depicts the overall frequencies of positive outcomes. Panel A shows that both couples received an email reply from the public housing companies about 76% of the time to their inquiries. Similarly, in Panel C, we can see that the probability of receiving information about apartments that one can move into immediately without putting oneself in a formal queue was also similar for both couples: 26 and 28% for the couple with the Swedish- and Arabic-sounding names, respectively. We can observe some differences in positive outcomes between the couples in Panels B and D. The couple with the Swedish-sounding names received a personal greeting in 23% of the cases. In comparison, the couple with the Arabic-sounding names did so in 17% of the cases. In Panel D, we can observe that the couple with the Swedish-sounding names was informed about problematic residential areas in 10% of the cases. In comparison, the couple with the Arabic-sounding names received such information in only 3% of the cases. shows similarities and disparities between the couples in the content of the public housing companies’ responses to the couples’ inquiries.

Figure 2. Fraction of inquiries that led to a positive outcome for each couple.

Note: Blue lines are 95% CI. № of firms = 271. Each firm received two inquiries, one from each couple. Red dots represent the probability of receiving an email reply (A), personal greeting (B), information about priority system for newcomers (C), and information about bad neighborhoods (D). Definitions of all variables are provided in .

In , we arranged our data to show the distribution of public housing companies’ responses and perform formal hypothesis tests. What is of interest is the differences in the number of cases where only the couple with the Swedish-sounding names achieved a positive outcome and the number of cases where only the couple with the Arabic-sounding names achieved a positive outcome, and not the mean differences in outcomes that were depicted in . charts the number of public housing companies that responded affirmatively to neither the Swedish couple’s nor the Arab couple’s inquiry (Neither), public housing companies that responded affirmatively to both couples’ inquiries (Both), public housing companies that only responded affirmatively to the Swedish couple’s inquiry (Swedish), and public housing companies that only responded affirmatively to the Arab couple’s inquiry (Arab). The distribution of public housing companies’ responses is tabulated for each outcome variable. The last column in provides the net differential treatment, simply the number of cases in which only the Arab couple received an affirmative response minus the number of cases in which only the Swedish couple received an affirmative response.

Table 2. Distribution of public housing companies’ responses to housing inquirers.

We tested the following null hypothesis of symmetry:

where σS is the probability that only the Swedish couple received an affirmative response, and σA is the probability that only the Arab couple received an affirmative response from the public housing companies to the couples’ inquiries. We tested the null hypothesis of symmetry (or equal treatment) for each outcome variable using McNemar’s test. Identical conclusions can be drawn by calculating two-sided exact p-values based on the binomial probability distribution.

shows that we can reject the null hypothesis of symmetry defined above for two of our four outcome variables. First, public housing companies were significantly more prone to initiate their response to a couple with a personal salutation (Greeting) when the couple had Swedish-sounding names than when the couple had Arabic-sounding names (McNemar’s test: p = 0.055; Binomial test: p = 0.072). Second, Public housing companies were significantly more likely to inform about problematic or unsafe residential areas that a couple should avoid (Bad zones) when the couple had Swedish-sounding names than when the couple had Arabic-sounding names (McNemar’s test: p < 0.001; Binomial test: p < 0.001). The Swedish couple was three times more likely than the Arab couple to receive information about problematic neighborhoods to keep away from (27/8 = 3.38).

Next, we conducted regression analyses and included a control dummy for order and seasonal effects in the experiment since there were more than two months between the first and second mailing batches. We also include a control dummy for geographical (county) effects (i.e. for large and small counties). presents four models, where we regress each of our four outcome variables on whether a couple had Swedish- or Arabic-sounding names, whether an inquiry from a fictitious couple was sent in the first (January 18, 2022) or second (April 2, 2022) stage of mailing, and whether or not an inquiry from a fictitious couple was sent to a public housing company in one of three largest counties in Sweden using linear probability models. Reported standard errors were corrected for clustering since each public housing company received two inquiries (one from the Swedish couple and one from the Arab couple) in the experiment.

Table 3. Positive outcome probabilities, adjusted for county and order effects.

shows that our initial findings are robust to our controls. Model 2 shows that the Arab couple was 6 percentage points less likely than the Swedish couple to be personally greeted in the public housing companies’ response. Moreover, Model 4 shows that the Arab couple was 7 percentage points less likely than the Swedish couple to receive information about problematic neighborhoods to avoid by public housing companies.

The coefficients of the control variables indicate a significant order effect. Specifically, the probability of receiving a reply to the first batch of emails was 11 percentage points higher than that for the second batch. We attribute this disparity possibly to a seasonal influence: the first batch was dispatched in January, a period when individuals are returning to work post-Christmas holidays, in contrast to the second batch sent in April, a time when businesses are fully functional and approaching the Easter holidays. Additionally, the impact of COVID-19 cannot be overlooked. The transition from having coronavirus restrictions in place in January to their removal by April may have necessitated an adjustment period in operations, subsequently reducing response rates.

Furthermore, the likelihood that a public housing company had a priority system for newcomers within the municipality was 17 percentage points lower if the company was located in one of Sweden’s three largest counties. This finding is logical, given the heightened competitiveness of the housing market in these areas, which coincide with Sweden’s three largest cities.

The reader may have observed that our regression models exhibit low R-squared values. However, this is common in the social sciences, particularly in randomized experiments and instances involving dependent dummy variables (De Brauw, Citation2015; Wooldridge, Citation2013). A low R-squared value does not necessarily indicate that the model provides a poor estimate or is useless (Wooldridge, Citation2013). For further discussion on this topic, see, for example, Bellemare (Citation2015), De Brauw (Citation2015), and Wooldridge (Citation2013).

Discussion

The primary aim of our study was to investigate the presence of any differential treatment practices by public housing companies in Sweden based on the ethnic backgrounds inferred from the names of couples inquiring about housing. The differences in responses received by a couple with Swedish-sounding names versus a couple with Arabic-sounding names on four outcome variables – Email reply, Greeting, Cut in line, and Bad zones – were of central interest. Our analysis suggests that differential treatment against the couple with the Arabic-sounding names did exist, albeit not across all four outcome variables. Notably, we observed no significant difference between the two couples in terms of email responses received or information about available apartments bypassing the usual queue. However, our findings showed a different trend for the variables Greeting and Bad zones.

The couple with the Swedish-sounding names received a personal greeting in their responses at a significantly higher rate than the couple with the Arabic-sounding names. This suggests an ethnic bias in communication, with the Swedish couple experiencing more personal engagement. Further, when it came to sharing information about problematic residential areas, the Swedish couple was informed at a rate more than triple that of the Arab couple. While we cannot definitively claim a pervasive and generalized differential treatment practice, our findings indicate the presence of subtle and significant disparities in communication, especially in information sharing by public housing companies in Sweden. These observations warrant further exploration and possible policy interventions to ensure equitable treatment for all prospective tenants, irrespective of their perceived ethnicity.

At this juncture, it is crucial to emphasize that the rate of personal greetings was generally low for both couples and even more so for sharing information about problematic residential areas by both couples. This trend may stem from the public housing company’s desire to maintain efficient communication. Consequently, they may bypass greetings to remain concise and avoid addressing sensitive issues concerning troubled neighborhoods.

Understanding why the Arab couple received fewer greetings may require delving into social psychology, theories of unconscious bias, and stereotypes. While our study cannot definitively provide explanations, there are plausible theories that might shed some light on this issue. First, housing professionals may be unwittingly influenced by their implicit biases (Banaji & Greenwald, Citation2016; Greenwald & Krieger, Citation2006). This form of bias occurs unconsciously and automatically as the brain makes quick judgments based on past experiences and cultural stereotypes. In this case, it is possible that the public housing professionals had unconscious biases towards individuals with Arabic-sounding names, leading them to provide less personal engagement. Second, stereotypes about ethnic groups can subtly influence behavior (Devine, Citation1989; Fiske et al., Citation2002). If negative stereotypes exist about people with Arabic-sounding names, housing professionals may react less warmly to them, resulting in fewer personal greetings. Last, professionals may feel less comfortable or less adept at communicating with people they perceive to be from a different cultural background (Neuliep, Citation2011; Stephan & Stephan, Citation1985), resulting in fewer greetings to the Arab couple.

However, one may ask, what is the concern if the Arab couple receives fewer greetings? There are a multitude of reasons why this might be an issue. First, fewer greetings to the Arab couple could indicate a more deeply rooted bias. While greetings may seem superficial, they are a form of acknowledgment and respect. Receiving fewer greetings can send a negative message to recipients, constituting a form of subtle adverse differential treatment. Second, it could influence the decision-making process. For instance, if a couple feels less welcome or is treated differently due to their ethnicity, they may want to avoid engaging further with that housing company, which can limit their housing options. Finally, on a societal level, such behavior can contribute to a lack of social cohesion and increased marginalization of certain groups. It is crucial for societal harmony that all ethnicities are treated equally and respectfully.

The scarcity of information offered about challenging areas to the Arab couple, compared to their Swedish counterparts, can potentially also be attributed to a multitude of factors. First, housing providers might stereotype and make assumptions based on the names of the inquirers (Carpusor & Loges, Citation2006; Charles, Citation2003). They might assume that those with Arabic-sounding names are more familiar with, or tolerant of, lower-quality neighborhoods due to biases about socioeconomic status or adaptability. Second, housing companies might exhibit a form of paternalism (Jackman, Citation1994; Rosen & Garboden, Citation2022), believing that they are protecting the Arab couple from potential adverse treatment or hardship they might face in specific neighborhoods. Third, they might make cultural assumptions that people with Arabic-sounding names would prefer or feel more comfortable in certain areas based on the ethnic makeup of those neighborhoods (Massey & Denton, Citation1993; Schelling, Citation1971) and so refrain from describing them as ‘bad’. Finally, underlying institutional practices may result in differential treatment between applicants based on perceived ethnicity (Pager & Shepherd, Citation2008; Rothstein, Citation2018).

Selectively concealing details about less desirable neighborhoods also presents various problems. Equal access to critical information is crucial when seeking housing. It is unjust for the Arabic-named couple to receive less information about the quality of neighborhoods, as it could lead them to select housing in less desirable or potentially unsafe areas unknowingly. Also, without information about problematic areas, individuals might unknowingly move into neighborhoods with high crime rates, poor public services, or other factors that can negatively impact quality of life.

The findings from our study spotlight distinctive patterns of differential treatment in the public housing sector, which raises intriguing questions about how these patterns compare to those observed in the private sector. Specifically, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of replies received by fictitious couples with Swedish-sounding versus Arabic-sounding names from public housing companies. This finding markedly contrasts with the extensive literature documenting lower response rates for ethnic minorities in the private sector, especially for individuals with Arabic-sounding names (Ahmed et al., Citation2010; Ahmed & Hammarstedt, Citation2008; Bengtsson et al., Citation2012; Carlsson & Eriksson, Citation2014; Molla et al., Citation2022). This absence of disparity in initial contact suggests that the public sector’s regulatory framework and commitment to social objectives may play a critical role in mitigating overt differential treatment of ethnic minorities. However, our study also uncovers subtler forms of differential treatment, such as variations in the personalization of greetings and the provision of information about problematic neighborhoods. These nuances indicate that while public housing policies may effectively reduce explicit biases at the point of initial contact, implicit biases persist, possibly manifesting in the quality of communication. This complex scenario underscores a distinct operational dynamic in the public housing sector, emphasizing the need to explore further public housing policies’ implementation and efficacy in comprehensively addressing overt and subtle adverse differential treatment. Our findings prompt a reevaluation of theoretical models on differential treatment in housing, highlighting the necessity for nuanced approaches that consider the sector-specific mechanisms through which differential treatment manifests and is addressed. The presence of any differential treatment in public housing is concerning, given its role as a last resort for marginalized individuals facing adverse differential treatment in the private market. This comparison not only highlights the need for ongoing vigilance and intervention in both sectors but also suggests that the mechanisms underlying the differential treatment of ethnic minorities may vary across different housing contexts.

Be it subtle or blatant forms of differential treatment, continued policies that bolster equity and foster inclusion are crucial within the housing sector. This sector must be an environment where all individuals are treated equitably. Implementing equality, diversity, and inclusion training for all staff members could serve as a powerful tool in this regard. Such training can illuminate overt and covert biases that might influence decision-making processes, enabling staff to adopt and maintain impartial practices. This would foster an environment where everyone, regardless of their ethnic background, is treated with the same level of respect and given equal opportunities. One example of such work is the commendable efforts by the organization Malmö Against Discrimination (Malmö mot Diskriminering). This organization has proactively developed a program to educate landlords on the risks and consequences of differential practices based on ethnicity. They aim to foster a more inclusive and equitable housing market by providing resources and training. Such initiatives exemplify practical steps toward addressing the educational needs we discuss, serving as valuable models for similar endeavors.

From a global perspective, this study offers valuable insights for countries with similar public housing systems facing similar challenges. Analyzing disparities in responses based on perceived ethnicity illuminates the subtle mechanisms of differential treatment affecting public housing practices. This nuanced understanding of how differential treatment manifests offers valuable lessons for countries aiming to evaluate and comprehend the dynamics of their public housing systems. Combining correspondence testing with a detailed analysis of response content, the methodology presents a solid model for researchers and policymakers in other countries dedicated to identifying and quantifying harmful and unfair differential treatment of ethnic minorities.

Ultimately, some introspective critique is in order. While our study identified instances of differential treatment in the practices of public housing companies, it is essential to note that not all metrics showed evidence of such treatment. In particular, no significant disparities were found concerning email responses and bypassing the usual queue for available apartments. These findings caution us against making broad generalizations about systematic differential treatment practices. Additionally, the inability to scrutinize real apartment applications directly, for reasons we have already detailed, limited our study’s breadth. Future research should strive to incorporate this crucial aspect. Real-world applications would offer a more accurate assessment of potentially harmful and unfair differential treatment, furthering our understanding of ethnic bias in public housing companies. In order to accomplish this, we need to ascertain a method to circumvent the established formal application process in public housing. This nuanced interpretation of the situation implies that any biases could be episodic or understated, highlighting the urgent need for more exhaustive research to fully expose and mitigate potential unfair differential treatment practices in public housing.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

While preparing this article, the authors used ChatGPT powered by GPT-4 to enhance grammar, clarity, and prose. After using this technology, the authors reviewed and revised the content as necessary. The authors assume full responsibility for the article’s content.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Rebecca Bandick and Umba Nsabimana for their assistance with data collection and coding. We appreciate the input from the editor, the three reviewers, and the seminar participants at Linköping University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ali Ahmed

Ali Ahmed is a professor of economics at Linköping University. His research primarily focuses on the unequal treatment and discrimination faced by vulnerable groups, such as ethnic minorities, within various markets and society at large.

Roger Bandick

Roger Bandick is an associate professor of economics at Linköping University. His research mainly explores foreign acquisitions, employment effects, and plant survival.

References

- Ahmed, A. (2015) Etnisk diskriminering – vad vet vi, vad behöver vi veta och vad kan vi göra?, Ekonomisk Debatt, 43, pp. 18–28.

- Ahmed, A., Andersson, L. & Hammarstedt, M. (2010) Can discrimination in the housing market be reduced by increasing the information about the applicants?, Land Economics, 86, pp. 79–90.

- Ahmed, A. & Hammarstedt, M. (2008) Discrimination in the rental housing market: A field experiment on the internet, Journal of Urban Economics, 64, pp. 362–372.

- Ahmed, A. & Nsabimana, U. (forthcoming) Brick by brick bias: Arab muslim experience of intersectionality in housing, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2024.2366319

- Arrow, K. J. (1973) The theory of discrimination, in: O. A. Ashenfelter & A. Rees (Eds) Discrimination in Labor Markets, pp. 3–33 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

- Auspurg, K., Schneck, A. & Hinz, T. (2019) Closed doors everywhere? A meta-analysis of field experiments on ethnic discrimination in rental housing markets, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45, pp. 95–114.

- Banaji, M. R. & Greenwald, A. G. (2016) Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People (New York, NY: Bantam Books).

- Banton, M. (2011) A theory of social categories, Sociology, 45, pp. 187–201.

- Becker, G. S. (1957) The Economics of Discrimination (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press).

- Bellemare, M. F. (2015) The Use and Misuse of R-Squared. Available at https://marcfbellemare.com/wordpress/10793 (accessed 1 July 2024).

- Bengtsson, R., Iverman, E. & Hinnerich, B. T. (2012) Gender and ethnic discrimination in the rental housing market, Applied Economics Letters, 19, pp. 1–5.

- Berndt Rasmussen, K. (2020) Implicit bias and discrimination, Theoria, 86, pp. 727–748.

- Bertrand, M. & Duflo, E. (2017) Field experiments on discrimination, in: E. Duflo & A. Banerjee (Eds) Handbook of Field Experiments, Volume 1, pp. 309–393 (Amsterdam: North-Holland).

- Borelius, U. & Wennerström, U. B. (2009) A new Gårdsten: A case study of a Swedish municipal housing company, European Journal of Housing Policy, 9, pp. 223–239.

- Carlsson, M. & Eriksson, S. (2014) Discrimination in the rental market for apartments, Journal of Housing Economics, 23, pp. 41–54.

- Carpusor, A. G. & Loges, W. E. (2006) Rental discrimination and ethnicity in names, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, pp. 934–952.

- Charles, C. Z. (2003) The dynamics of racial residential segregation, Annual Review of Sociology, 29, pp. 167–207.

- Christophers, B. (2013) A monstrous hybrid: The political economy of housing in early twenty-first century Sweden, New Political Economy, 18, pp. 885–911.

- Clarke, J. A. (2018) Explicit bias, Northwestern University Law Review, 113, pp. 505–586.

- Coate, S. & Loury, G. C. (1993) Will affirmative-action policies eliminate negative stereotypes?, American Economic Review, 83, pp. 1220–1240.

- De Brauw, A. (2015) R-squared doesn’t matter—At least not in randomized control trials. International Food Policy Research Institute. Available at https://www.ifpri.org/blog/r-squared-doesnt-matter%E2%88%92-least-not-randomized-control-trials (accessed 1 July 2024).

- Devine, P. G. (1989) Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, pp. 5–18.

- Dovidio, J. F., Hewstone, M., Glick, P., & Esses, V. M. (Eds) (2010) The SAGE Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination (London: Sage Publications).

- European Commission (2013) Discrimination in Housing (Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Union).

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P. & Xu, J. (2002) A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, pp. 878–902.

- Flage, A. (2018) Ethnic and gender discrimination in the rental housing market: Evidence from a meta-analysis of correspondence tests, 2006–2017, Journal of Housing Economics, 41, pp. 251–273.

- Gaddis, S. M. (ed.) (2018) Audit Studies: Behind the Scenes with Theory, Method, and Nuance (Cham: Springer).

- Galster, G. C. (1992) Research on discrimination in housing and mortgage markets: Assessment and future directions, Housing Policy Debate, 3, pp. 637–683.

- Grander, M. (2023) Den kommunala allmännyttan – Fyra motsägelser och vägval för framtidens bostadsförsörjning (Stockholm: Bostad2030).

- Greenwald, A. G. & Krieger, L. H. (2006) Implicit bias: Scientific foundations, California Law Review, 94, pp. 945–967.

- Jackman, M. R. (1994) The Velvet Glove: Paternalism and Conflict in Gender, Class, and Race Relations (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

- Laham, S. M., Koval, P. & Alter, A. L. (2012) The name-pronunciation effect: Why people like Mr. Smith more than Mr. Colquhoun, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, pp. 752–756.

- Lang, K. & Lehmann, J. Y. K. (2012) Racial discrimination in the labor market: Theory and empirics, Journal of Economic Literature, 50, pp. 959–1006.

- Malmberg, B., Abramsson, M., Magnusson, L. & Berg, T. (2004) Från eget småhus till allmännyttan (Stockholm: Institutet för framtidsstudier).

- Malmö mot Diskriminering (2022) Jag tror vi diskriminerar utan att vi ens tänker på det (Malmö: Malmö mot Diskriminering).

- Massey, D. S. & Denton, N. A. (1993) American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

- McCrudden, C. (1982) Institutional discrimination, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 2, pp. 303–367.

- Molla, H., Rhawi, C. & Lampi, E. (2022) Name matters! The cost of having a foreign-sounding name in the swedish private housing market, PloS One, 17, pp. 1–14.

- Neuliep, J. W. (2011) Intercultural Communication: A Contextual Approach (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications).

- Oxford Research (2013) Forskning om diskriminering av muslimer i Sverige (Stockholm: Oxford Research).

- Pager, D. & Shepherd, H. (2008) The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets, Annual Review of Sociology, 34, pp. 181–209.

- Phelps, E. S. (1972) The statistical theory of racism and sexism, American Economic Review, 62, pp. 659–661.

- Pittini, A. & Laino, E. (2011) The Nuts and Bolts of European Social Housing Systems (Brussels: CECODHAS Housing Europe’s Observatory).

- Public Housing Sweden (2019) Vi är Sveriges Almännytta (Stockholm: Sveriges Allmännytta).

- Quillian, L., Lee, J. J. & Honoré, B. (2020) Racial discrimination in the US housing and mortgage lending markets: a quantitative review of trends, 1976–2016, Race and Social Problems, 12, pp. 13–28.

- Rosen, E. & Garboden, P. M. (2022) Landlord paternalism: Housing the poor with a velvet glove, Social Problems, 69, pp. 470–491.

- Rothstein, R. (2018) The Color of Law (New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation).

- Silver, H. & Danielowski, L. (2019) Fighting housing discrimination in Europe, Housing Policy Debate, 29, pp. 714–735.

- Schelling, T. C. (1971) Dynamic models of segregation, Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 1, pp. 143–186.

- Schwartz, A. F. (2021) Housing Policy in the United States (New York: NY: Routledge).

- Solomos, J. (ed.) (2020) Routledge International Handbook of Contemporary Racisms (New York, NY: Routledge).

- Statistics Sweden (2023). Boende i Sverige. Statistikmyndigheten. Available at https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/boende-i-sverige/ (accessed 31 May 2023).

- Stephan, W. G. & Stephan, C. W. (1985) Intergroup anxiety, Journal of Social Issues, 41, pp. 157–175.

- Swedish Code of Statutes (2003). Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor. 2003:460. Available at https://lagen.nu/2003:460 (accessed 1 July 2024).

- Swedish Code of Statutes (2008). Diskrimineringslag. 2008:567. Available at https://lagen.nu/2008:567 (accessed 1 July 2024).

- Swedish Code of Statutes (2010). Lag om allmännyttiga kommunala bostadsaktiebolag. 2010:879. Available at https://lagen.nu/2010:879 (accessed 1 July 2024).

- Tileagă, C., Augoustinos, M., & Durrheim, K. (Eds) (2022) The Routledge International Handbook of Discrimination, Prejudice and Stereotyping (New York, NY: Routledge).

- Turner, B. (2006) Wealth effects and price volatility – How vulnerable are the households?, Public Finance and Management, 6, pp. 41–64.

- Turner, B. & Whitehead, C. M. (2002) Reducing housing subsidy: Swedish housing policy in an international context, Urban Studies, 39, pp. 201–217.

- Wirtén, G. (2022) Lyssna: Vår reporter söker lägenhet med svenskt vs. utländskt namn. Sydsvenskan, October 4. Available at https://www.sydsvenskan.se/2022-10-04/lyssna-var-reporter-soker-lagenhet-med-svenskt-vs-utlandskt-namn/ (accessed 1 July 2024).

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2013) Econometrics: A Modern Approach (Mason, OH: South-Western).

- Ziegerer, J., Abbas, H., Hamadan, I. & Karlsson, J. M. (2022) Hyresvärd på Rosengård vill inte ha araber i sin ahus. Sydsvenskan, October 6. Available at https://www.sydsvenskan.se/2022-10-06/hyresvard-pa-rosengard-vill-inte-ha-araber-i-sina-hus (accessed 1 July 2024).