Abstract

Estate renewal has come to be touted as a means of improving social housing supply both qualitatively and quantitatively, replacing ageing and under-maintained dwellings and increasing the total stock of social housing. In this paper, we examine the latter claim. We develop novel measures and methods for calculating the social housing supply impacts of estate renewal, taking account of the reduction in supply caused by tenant relocations and dwelling demolitions prior to the delivery of new social housing. Using administrative data on tenant relocations and dwelling completions for three projects in Sydney, we calculate the social housing accommodation deficit caused by the renewal process, subsequently, the time required for each project to deliver more nights of accommodation than this deficit. These measures illuminate the significant impacts of estate renewal on the social housing system and problematize its justification based on gross or net social housing supply. They constitute a valuable method for examining estate renewal, wherever it may occur.

1. Introduction

In June 2023, activists from Action for Public Housing – a grassroots, pro-public housingFootnote1 organization – occupied vacant properties in a seventeen-unit public housing complex in the inner-Sydney neighbourhood of Glebe. The complex at 82 Wentworth Park Road was earmarked for redevelopment and only five households remained awaiting relocation; eleven had already moved to public housing elsewhere and three units were left vacant following two deaths and one eviction. The occupiers drew attention to what they saw as a waste of decent public homes – then 35 years old – at a time when there were more than 54,000 households on the state’s social housing waiting list (NSW Department of Communities & Justice, Citation2024) and dozens of people sleeping rough under the viaducts in the neighbouring park (Sydney Local Health District, n.d.). While the occupation led to a commitment from the Minister for Housing and Homelessness, Rose Jackson, that the seventeen units would be replaced by 43 publicly-owned and managed homes (via X, formerly TwitterFootnote2) activists continued to challenge the demolition of public housing when there was immense and urgent need, arguing that ‘120,000 people are homeless every night yet the MinnsFootnote3 Government plans to demolish 82 Wentworth Park Rd and leave these beautiful homes empty while people sleep rough across the road’ (Wang, Citation2023, n.p.). On the second day of the occupation, they unfurled a banner that read ‘Fill These Homes Now’ ().

The occupation of 82 Wentworth Park Road questioned a model of social housing development that requires existing social housing to be left vacant for long periods, and then lost to lengthy demolition and redevelopment processes, before any more social housing is added to the system. It is an issue of widespread concern, with estate renewal emerging as core to social housing policy throughout the Global North in the 1990s as governments grappled with generally under-maintained twentieth century stock and growing housing need (Watt & Smets, Citation2017). The New South Wales (NSW) government’s approach is emblematic: it has become increasingly reliant on estate renewal in attempting to improve and expand social housing in the twenty first century (Wynne et al., Citation2022), shifting from early projects that reduced on-site social housing and introduced private tenures in response to purported social and environmental dysfunction (Judd & Randolph, Citation2006), to those which ‘renew and grow supply’ of both social and market-rate housing (NSW Government, Citation2016, p. 9). Following the election of a new Labor government in NSW in March 2023, Minister Jackson described the Waterloo estate renewal as ‘a great opportunity to deliver a substantial uplift’ in social housing (Beazley & Rose, Citation2023, n.p.) and criticized the Bayside Council for preventing the delivery of more social housing by delaying another estate renewal in Mascot (Koziol, Citation2023). In short, estate renewal now aims to improve social housing supply both qualitatively – by replacing older housing stock with newer – and quantitatively – by increasing the total social housing stock. However, as Action for Public Housing highlighted, and as we outline in this paper, any measure of the quantitative improvement in social housing supply via estate renewal must account for the significant medium-term social housing stock deficits caused by tenant relocation programs (which absorb many of the limited vacancies within the remaining social housing stock and thus further delay allocations from the waiting list) as well as the demolition and redevelopment process (Porter et al., Citation2023; Watt, Citation2023).

In this paper we develop and test novel measures of social housing supply in the context of estate renewal. Research on estate renewal (and, indeed, its policy justification) has hitherto focused on the gross and net social housing delivered through a given project or program; that is, it has focused on the total social housing dwellings built and the additional social housing dwellings delivered over and above those which were demolished. As measures of estate renewal, gross and net social housing focus on the number of dwellings delivered. We develop three further measures that, we argue, better account for the social housing supply impacts over the entire estate renewal process by measuring the number of nights of social housing accommodation lost and, later, added through estate renewal. These measures are the social housing accommodation deficit, net social housing accommodation delay and net social housing interval. We define these measures and test them using tenant relocation and dwelling completions data relating to three estate renewal projects in Sydney: Ivanhoe, Arncliffe, and Glebe. Our novel measures and methods problematize conventional measures of gross and net social housing supply, and their use as justification for estate renewal, by accounting for the social housing loss that precedes social housing gain. These measures will enrich wider analysis of estate renewal projects and programs wherever they may occur.

In the next section, we provide a short history of estate renewal in NSW. We then outline our cases, data, and methods, including our novel measures of social housing supply. Next, we present and discuss our results, before concluding the paper with implications for housing policy and research. Our findings illustrate significant limitations of prevailing estate renewal models and destabilize claims about the timing and scale of new social housing supply, thereby highlighting the need for new approaches to social housing estate renewal and development.

2. Estate renewal in New South Wales

Public housing provision in Australia began in earnest during the period of post-war reconstruction in the late 1940s and early 1950s, with a series of agreements between the Commonwealth Government and State Governments setting the terms on which the former would make funds available to the latter – termed Commonwealth States Housing Agreements until the 2009 agreement. Public housing in Australia peaked at around eight percent of the nation’s total housing stock in 1966 (Hayward, Citation1996). At roughly one in four rental homes, it did for a short time present a realistic alternative rental tenure for low- to moderate-income households. Until the 1970s, public housing was targeted at households with at least one breadwinner and offered a pathway to homeownership for those who could afford the favourable terms of purchase offered to sitting tenants (Troy, Citation2012). A series of reforms, beginning in the 1970s, commenced a process of ‘residualization’: the introduction of market rents, the targeting of assistance to very low-income households (who qualified for income-based rents) and declining Commonwealth Government funding (in favour of a supplementary payment for private rental households receiving government income support) combined to prevent the entry and encourage the exit of moderate-income households, shrink State Housing Authorities’ (SHAs) rental revenues, and diminish their capacity to adequately maintain and build new stock (Sisson, Citation2024). By the 2001 Census, public housing made up 4.5% of all dwellings; by the 2021 Census, it made up 2.5%, with another 0.7% being community housing run by non-government Community Housing Providers (CHPs). With the growth of the latter, the term ‘social housing’ has become widely used to describe both community and public housing.

The renewal of public housing became a central element of Australian social housing policy in the twenty first century, particularly in NSW. As in other regions of the Global North (Goetz, Citation2013; Watt & Smets, Citation2017) renewal first emerged in the 1980s as a policy response to concentrated socio-economic disadvantage (Hughes, Citation2004). Early estate renewal projects in NSW tended to be property-led (Judd & Randolph, Citation2006) insofar as they addressed housing stock and built environment challenges. Residents remained in their homes, with interventions funded and managed by SHAs. By the 1990s, estate renewal was entrenched in social housing policy across Australian states (Pawson & Pinnegar, Citation2018; Arthurson, Citation1998). The rationale for these initiatives evolved beyond initial concerns about the physical quality of housing stock (although this remained a central consideration) to actively considering ‘potential for private sale’ (Arthurson, Citation1998, p. 35), that both reduced government expenditure (through generating revenue) and promoted tenure mix (Eastgate, Citation2016). The Neighborhood Improvement Program, implemented by the NSW Department of Housing from 1995, is an example of this type of intervention, as it focused on ‘de-Radburnising’ 1970s estates, rectifying built environments seen as dysfunctional (Judd & Randolph, Citation2006; Woodward, Citation1997; Collins, Citation2006).

In the early 2000s, community renewal became a more central objective of intervention in public housing estates (Judd & Randolph, Citation2006). While this incorporated many of the built form interventions and sale of dwellings to the private market, it also incorporated programs to address socio-economic disadvantage, such as education, employment, and community development initiatives. An example of this form of renewal was the Community Renewal Strategy implemented in 1999 in Waterloo, Airds, and Macquarie Fields (Collins, Citation2006; Wood et al., Citation2002). These initiatives were funded and managed by the SHA; however, partnerships with non-profit social service providers and other government agencies became the dominant delivery configuration. The SHA worked to coordinate government and non-government interventions and, importantly, most residents remained in their homes.

By the mid-2000s, in response to diminishing Commonwealth and State funding (Groenhart & Burke, Citation2014) and increasing land values, SHAs began to partner with the private sector to fund and deliver the redevelopment of estates. The first of these public-private partnership (PPP) projects in NSW involved the redevelopment of suburban estates in western and south-west Sydney: Minto, Airds-Bradbury, Claymore, Rosemeadow-Ambarvale and Bonnyrigg (). These projects were delivered by complex partnership arrangements which included developers, construction firms, CHPs, financial institutions, and social services providers, requiring ‘intricately interwoven legal frameworks between the constituent agencies, arms of government and the myriad other stakeholders to be involved in the renewal process’ (Pawson & Pinnegar, Citation2018, p. 324). Core to the financial viability of redevelopment (to both public and private sector actors) is the capacity to increase dwelling density: these projects delivered more dwellings on site, often made possible through rezoning. However, while the total number of dwellings increased on these sites, the number of social housing dwellings on-site decreased, with net increases in housing stock being in private tenures ().

Table 1. Estate renewal projects in Greater Sydney, 2000–2023.

While the shift towards the PPP model rests on the appeal of private finance and development, it is equally a product of the retreat of the state from the management of social housing tenancies and the promotion of CHPs as supposedly more efficient tenancy managers (Wynne et al., Citation2022). With the new National Affordable Housing Agreement in 2009, the Commonwealth and State Governments agreed to a target for CHPs to manage up to 35% of all social housing by 2014 (Yates, Citation2013; Jacobs & Travers, Citation2015). By 2022, CHPs were managing 34% of the social housing stock in NSW, having managed just six per cent in 2002 (Productivity Commission, Citation2005, 2023), most of this being stock transferred from SHAs rather than coming from new construction (Darcy, Citation2020). The appeal of CHPs as social housing managers and members of partnerships responsible for delivering estate regeneration rests on the belief that they will provide management efficiencies compared to SHAs, whilst also raise private debt, attract tax benefits, charge higher rents, cross-subsidize, undertake commercial activities and access tenants’ Commonwealth Rent Assistance paymentsFootnote4 (Yates, Citation2014; Pawson & Gilmour, Citation2010; Milligan et al., Citation2009). Under the PPP renewal models, CHPs become the tenancy managers as tenants transition out of public housing and into community housing.

Estate renewal has been in large part justified through its role in creating ‘mixed communities’—a new policy paradigm which gained traction as the rationale for redeveloping social housing across the UK, Europe, and the US (Galster, Citation2007; Joseph, Citation2006; Lees et al., Citation2012; Popkin et al., Citation2009; Atkinson & Kintrea, Citation2000). Across most estate renewal projects in NSW, the goal has been to achieve a 70:30 private-social tenure mix. Mixed tenure or ‘social mix’ is presented as a mechanism for households living in private housing to act as role models for social housing tenants, who are positioned by the state as deviant citizens failing to adhere to the neoliberal ideal of the individualistic, self-supporting citizen. The conceptual and empirical underpinnings of this policy have been critiqued (e.g. Lees et al., Citation2012; Morris et al., Citation2012; Ruming et al., Citation2004). As Darcy and Rogers (Citation2016) argue, the 70:30 social to private ratio also represents a financial condition underpinning estate renewal: it is the ability to fund upgrades and additions to the social housing stock through the construction and sale of private housing that is arguably the model’s more powerful driver. Indeed, the NSW Land and Housing Corporation (LAHC) – responsible for the management of public housing assets, as distinct from the tenancy management responsibilities performed by the Department of Communities and Justice – is a self-funded Public Trading Enterprise that, in the absence of adequate State or Commonwealth Government funding, must generate revenue to fund its operations through estate redevelopment or otherwise privatizing existing assets.Footnote5

With the continuation of these funding arrangements into the 2010s, the focus of estate renewal in NSW swung from low-density suburban estates in western and south-west Sydney to estates in locations where land values and site characteristics enabled more significant uplift in dwelling density (Wynne et al., Citation2022). This roughly aligns with a change in government. Whereas the Labor Governments of Premiers Carr, Iemma, Reece and Kenneally (1995–2011) undertook renewal projects that were ostensibly aimed at fixing estates seen as dysfunctional, and reduced both the number and proportion of social housing dwellings in each site, the Liberal-National Coalition Governments of Premiers O’Farrell, Baird, Berejiklian and Perrottet (2011–2023) saw estate renewal as an opportunity to maximize the delivery of new social and (primarily) market-rate housing, aligned with their broader ‘asset recycling’ agenda of selling public assets to fund new infrastructure. Put differently, whereas the Labor Governments of the 2000s appeared to target estates deemed to have the most problematic social and environmental characteristics, the Coalition Governments of the 2010s targeted those where there was the greatest capacity for the private sector to deliver more housing. The Communities Plus program, launched in 2015, held to the mixed tenure model and repeated many of its social arguments: according to then-Social Housing Minister, Brad Hazzard, the program was ‘encouraging people in social housing to be aspirational, not generational’ (NSW Government, Citation2016, p. 9). It also explicitly targeted sites that had good transport connections, were located near education and employment opportunities, and had few impediments to higher density redevelopment. Many projects were aligned with wider urban renewal projects led by the former state development corporation Urban Growth NSW (NSW Government, Citation2016). Among them were the ‘Major Sites’ in Macquarie Park (i.e. Ivanhoe estate), Waterloo, Riverwood, Arncliffe and Telopea, as well as vacant sites in Redfern and VillawoodFootnote6 (). Each project involved rezoning to significantly higher density, with a target of 30% social housing and no net loss. This target resulted in marginal growth in some cases and significant growth in others ().Footnote7 The model has involved a tender process for development consortia comprised of property developers, financiers and CHPs. While the ‘Communities Plus’ name has been abandoned and NSW Labor returned to government following the March 2023 election, several projects have progressed through these tender, planning, and development processes.

This model of estate renewal requires the relocation of existing tenants so that dwellings can be demolished and new homes built in their place. For some tenants, this has involved temporary relocation to another social housing dwelling (described elsewhere as ‘decanting’) and return to the redeveloped estate. In other cases, tenants have moved directly into a newly built home on the (former) estate. Others have permanently moved into social housing or alternative accommodation elsewhere. The relocation process has varied between projects and, in some cases, within them (Porter et al., Citation2023). Some suburban estates (e.g. Bonnyrigg), with detached dwellings covering large areas, have been redeveloped to allow relocations to occur in stages rather than en masse, and have minimized the need for temporary relocations by building new dwellings for sitting tenants to move into directly (although given many of these projects have reduced the total number of social housing dwellings, they may have necessitated some permanent relocations into existing social housing elsewhere). In higher-density estates, the large number of attached dwellings on a relatively smaller site makes staged relocations more challenging. Moreover, development feasibility models for some Communities Plus projects (e.g. Ivanhoe) have been based on wholesale demolition at the state’s expense. Thus, all tenants have been relocated before any demolitions have occurred, though all tenants have a ‘right of return’Footnote8 (Porter et al., Citation2023). While staging is occurring with the renewal of the Riverwood, Telopea and Waterloo estates, some stages could encompass several hundred tenants.

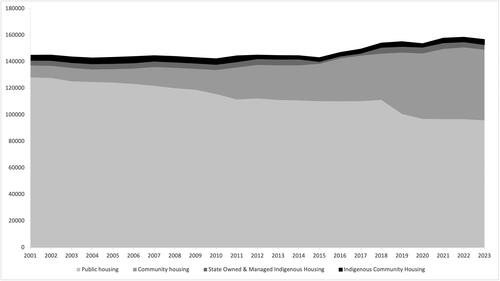

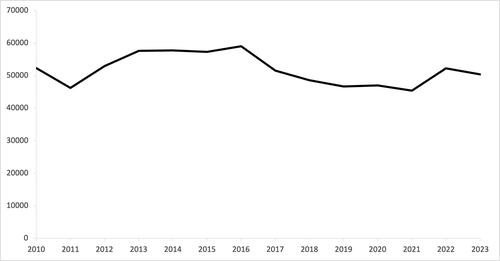

Relocations are a long and complex process, requiring an assessment of tenants’ needs and identification of a suitable dwelling (Porter et al., Citation2023; Ruming & Melo Zurita, Citation2020, Citation2024). The negative health and wellbeing impacts of this process are well documented, both within Australia and elsewhere (e.g. August, Citation2015; Goetz, Citation2013; Watt, Citation2021; Lees & Hubbard, Citation2022). In the Australian context, such impacts have included loss of social and community networks and sense of place, as well as anxiety, stress, and other forms of psychological distress (e.g. Arthurson Citation2002; Crawford & Sainsbury, Citation2017; Porter et al., Citation2023; Stubbs et al., Citation2005; Pinnegar et al., Citation2013), sometimes precipitating deteriorating physical health (Morris, Citation2018). The chronic shortage of social housing adds further complications. As illustrates, social housing in NSW has grown by only 13,688 dwellings between 2001 and 2022 – a 9% increase compared to 26% growth in the state’s population.Footnote9 The waiting list in NSW has remained stubbornly high at around 50,000 households since 2010Footnote10 (). In this context, the impacts of relocations are also felt by households on the social housing waiting list: these households must wait longer for an offer when sitting tenants are moved into available vacancies and the total stock of social housing diminished. As Morris et al. (Citation2023) find, such impacts similarly span physical and mental health and wellbeing due to prolonged homelessness, higher housing costs, energy poverty, and foregone necessities such as food and healthcare.

Figure 3. Total social housing stock in NSW, 2001–2023 (Source: Productivity Commission Citation2005, Citation2009, Citation2013, Citation2018, Citation2024).

Figure 4. NSW social housing waiting list, 2010–2023 (Source: Productivity Commission, Citation2013, Citation2018, Citation2024).

There is a need, then, to account for the system-wide impacts of relocations and renewal as well as their impacts on tenants who are directly affected. Existing scholarship has recognized such systemic impacts of estate renewal where it results in a net reduction in social housing. Goetz (Citation2013), for instance, documented the dramatic reduction in social housing through the HOPE VI program, which demolished some 250,000 social housing units and (particularly following the abolition of the 1:1 replacement requirement between 1995 and 2010) rebuilt significantly fewer (c.f. Vale, Citation2018). Similarly, Watt’s (Citation2021) research in London – where estate renewal caused an on-site reduction in social housing units of approximately one-quarter between 2005 and 2015 (London Assembly Housing Committee, Citation2015) – criticizes the shift in emphasis from replacement of social housing (albeit with some loss) to later projects dominated by market-rate housing provision, including the extreme case of the Heygate estate renewal reducing social housing by 92%. In wider contexts of stagnant social housing production and privatization of existing stock, such estate projects have been characterized as state-led gentrification (Lees, Citation2014; Lees & Ferreri, Citation2016; Watt, Citation2021). Indeed, Goetz (Citation2013) argues that, in the US, patterns of public housing demolitions have increasingly followed patterns of gentrification pressures.

The experience in NSW has been less extreme, being more limited in scope and less deleterious to the social housing stock. Nevertheless, in the context of a social housing stock that is stagnant and declining in real terms, estate renewal has a significant impact, even if it eventually increases social housing supply. These impacts have been alluded to in the work of Gillespie et al. (Citation2018), Watt (Citation2016, Citation2021), and Norris & Hearne (Citation2016) but there has been no attempt to measure them quantitatively. As Watt (Citation2023) notes, the focus of research and policy tends to be on the periods immediately prior to and following renewal (for exceptions see, Kabisch et al., Citation2022; Romyn, Citation2020; Johnson & Johnson, Citation2020), through measures like gross and net social housing. In contrast, our analysis quantifies the impacts of the entire renewal process on the social housing stock, from the commencement of relocations up to and beyond the completion of new social housing dwellings. This enables a more comprehensive understanding of the social housing supply impacts of estate renewal, beyond simple claims based on gross or net social housing units.

3. Cases, data, and methods

The social housing supply outcomes of estate renewal are typically measured by counting the number of dwellings delivered: either gross social housing – the total number of dwellings built – or net social housing – the additional number of dwellings built. In this section we develop three additional measures of the social housing supply outcomes of estate renewal and outline the case studies, data, and methods used to calculate these outcomes. The key measures, including our three novel measures, are:

Baseline social housing: the total number of habitable dwellings on an estate prior to commencement of relocations;

Gross social housing: the total number of social housing dwellings delivered by an estate renewal project;

Net social housing: gross social housing less baseline social housing;

New social housing proportion: gross social housing as a percentage of the total number of dwellings across all tenures delivered through the renewal process;

Proportional social housing uplift: percentage increase in social housing delivered by an estate renewal project; that is, net social housing as percentage of baseline social housing;

Social housing accommodation deficit: the total nights of social housing accommodation that are lost as dwellings are made vacant (following tenant relocation) and demolished. This is calculated as the sum total of the time between each unit being made vacant and its replacement by new social housing dwelling;

Net social housing accommodation delay: the time required for net social housing to deliver more nights of accommodation than the social housing accommodation deficit; and,

Net social housing accommodation interval: net social housing accommodation delay plus the time elapsed between commencement of relocations and delivery of net social housing.

3.1. Case studies

The three case study projects represent contrasting outcomes from estate renewal as well as differences in project size and timeframe. The Ivanhoe estate is located 15 km northwest of the Sydney CBD in the Macquarie Park corridor. Built between 1986 and 1990, it was the last large-scale public estate development in NSW. Built around a cul-de-sac street with a single road entrance, Ivanhoe had 259 dwellings – a mixture of apartments and townhouses – and was home to 452 residents when relocations commenced. The Ivanhoe estate sits within a larger centre which has been the subject of wider strategic planning efforts from state and local government (NSW Department of Planning & Environment, Citation2015). As a result, the site was rezoned to allow a significant increase in the permissible density, making it an appealing location for redevelopment. Ivanhoe was the first major project of the Communities Plus program, being put out to tender in 2016 and awarded to the successful development consortium in 2017. Demolition began in early 2018, with all tenants to be relocated by this date (although some remained on the estate until 2019). The staged redevelopment of the Ivanhoe estate – renamed ‘Midtown Mac Park’ – will deliver 945 social homes alongside 2,304 private and 130 affordable dwellings,Footnote11 with the first stage of construction expected to end in 2024 and the final stage in 2032.

The Arncliffe estate is located approximately 10 km south of the Sydney CBD, along the Princes Highway, and a few hundred metres from Arncliffe railway station. The estate fell within the Arncliffe Planned Precinct, which was in 2014 nominated by the former Rockdale City Council (now Bayside Council) for rezoning and urban renewal, including revitalization and activation of the Princes Highway Corridor (NSW Department of Planning & Environment, Citation2018). It’s our oldest case study estate, having comprised multiple three-storey brick walk-up apartment buildings constructed in the 1950s. At the time of writing, demolition is underway; the redevelopment will transform the 142-dwelling estate, which was home to 177 people, into 180 social and 564 market-rate dwellings, renamed Arncliffe Central. All social housing will be completed in the first stage in 2026 and housed in one of three towers. While relocations began in 2018 and concluded in 2021, the estate was later used as emergency accommodation for 30 households from 2020 to 2023, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The final case study comprised two small adjoining complexes a few kilometers west of the Sydney CBD, 17–31 Cowper St and 2A–2D Wentworth Park Rd Glebe. The former was a 15-unit building of one-bedroom apartments and the latter a four-unit complex of three-bedroom terraces. Both were built during the 1980s as part of the NSW Housing Commission’s celebrated infill development program across inner-city Sydney (Zanardo & Boyd, Citation2019). It is the most advanced of the three case studies, demolished in 2022 and with construction of 75 social dwellings expected to be completed in 2025. This project is unique in that community opposition to the initial proposal prompted the NSW Government to revise its plans to make the project 100% social housing rather than mixed tenure. This opposition involved anti-gentrification group Hands Off Glebe, preservationist group the Glebe Society, and then-local Member of Parliament, Jamie Parker, in what was a more antagonistic and organized campaign against estate renewal than had been present in either Arncliffe or Ivanhoe (the latter prompting a degree of opposition, albeit less concerted and organized). These groups had previously mobilized against the renewal of public housing on the opposite side of Cowper St (where 134 public homes were replaced with 153 social housing, 250 market-rate and 90 affordable dwellings) and subsequently against the redevelopment of 82 Wentworth Park Rd mentioned at the start of this paper. They have also campaigned against the sale of social housing in Glebe – which amounted to 26 properties between 2011 and 2023 for a total of $106 m (McGowan, Citation2023).

3.2. Data

To examine our case studies using the measures outlined above, we required information about the number of households relocated off each estate, the date each household was relocated, and anticipated completion date for each new social housing unit. These data are not publicly available. We therefore accessed tenant relocation data and project development timelines through freedom of information requests under the NSW Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009. Firstly, relocations data were requested from the Department of Communities and Justice (GIPA23/1495 and GIPA 23/3034), responsible for public housing tenancy management and relocations. This also included data regarding whether tenants moved into (i) another social housing dwelling, (ii) private accommodation, (iii) ‘headleased’ accommodation (i.e. private rental procured by LAHC and leased to the tenant at social housing rents), or (iv) other (including living with family or deceased). For Arncliffe specifically, we requested tenancy commencement and end dates for each household who accessed housing on the estate through the emergency housing program, though only end dates were provided. As a result, the Arncliffe analysis assumes that emergency housing tenancies commenced March 19th, 2020 – the day following the Australian Government’s declaration of a Human Biosecurity Emergency – although this is almost certainly earlier than the dates these leases commenced. Secondly, completions data were requested from the Department of Planning and Environment (GIPA24/3072 and GIPA24/3048), which oversees LAHC and the estate renewal process. This included dates of completion for social, affordable, and private dwellings in each project. Rough estimates were provided, rather than precise dates, reflecting the best estimates of LAHC at the time of our requests.

3.3. Methods

Calculating the social housing accommodation deficit of each case involved calculating, for each relocation (and thus vacancy created), the number of days until a replacement social housing dwelling is expected to be completed, and summing the result. While straightforward, this calculation required some key assumptions and inferences. For dwelling completions expected early in calendar year X (e.g. ‘Early 2024’), we infer a date of the mid-point of the first quarter of year X (e.g. 15th February 2024). For dwelling completions expected late in year X (e.g. ‘Late 2024’), we infer a date of the mid-point of the fourth quarter of year X (e.g. 15th November 2024). For dwelling completions expected in the middle of year X (e.g. ‘mid-2024’) or simply in year X (e.g. ‘2024’), we infer a date of the middle of year X (e.g. 30th June 2024). To account for households that were not relocated into existing social housing but into head-leased or other properties (and thus did not impact the social housing stock) our final result is reduced by an amount equivalent to the product of the number of such relocations and the average social housing accommodation deficit per relocation. To account for the Arncliffe estate’s use as emergency housing, we subtract the sum of the total length of each emergency housing tenancy. The results for each project are shown in .

Table 2. Summary of Ivanhoe, Arncliffe & Glebe projects and results.

We then calculate the net social housing accommodation delay. For Glebe and Arncliffe, this step simply involves dividing the social housing accommodation deficit by net social housing. As noted, this is a measure of the amount of time that net social housing delivered through estate renewal will take to make up for the deficit caused by relocations, demolition, and redevelopment. Net social housing is calculated as gross social housing minus baseline social housing, which, for the purposes of our analysis, we assume is equal to the total number of households relocated. Our rationale for this is based on the conservative assumption that unoccupied homes were uninhabitable. For Ivanhoe, staged redevelopment makes the process more complicated. We first calculate the number of relocations, completions, and net social dwellings for each quarter, beginning with the quarter in which the first relocation occurred. For each quarter, we calculate a ‘running deficit’ by subtracting the number of nights of social housing accommodation lost due to relocations up to that point in time (reduced by a factor of 47/258, or 18%, to account for households relocated into non-social housing) from the net social housing that was present in that quarter. This means that the project accumulates a deficit until the completion of Stage 1, after which the solitary net social housing dwelling begins to slowly recover the social housing accommodation deficit until subsequent stages speed up this recovery. The quarter in which the running deficit exceeds zero is equivalent to the net social housing accommodation delay calculated for Glebe and Arncliffe. (We repeated this method to visualise the results for Arncliffe and Glebe). Finally, calculating the net social housing accommodation interval of each project simply involves adding the net social housing accommodation delay calculated in the previous step to the length of time between the first relocation and delivery of net social housing.

4. Results

The results of our analysis are summarized in and through . While there are notable differences in outcomes across the three estate renewal projects, owing to their varied size, tenure mix, net social housing and proportional social housing uplift, the relocation of tenants and demolition of existing social housing for all three projects has been a significant imposition on the social housing system.

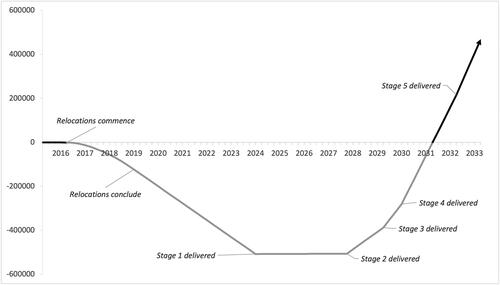

4.1. Ivanhoe

Given the size of the original estate and of the proposed renewal, the Ivanhoe case is characterized by both a long period of tenant relocations (three years and five months between first to final relocations) and a long period between the commencement of relocations and the delivery of net social housing (nine years). When the first stage of 259 social housing dwellings is due for completion (expected in early 2024), more than four and a half years will have passed since the final relocation. We estimate that the total social housing accommodation deficit to be 527,793 nights, with each relocation having, on average, a social housing accommodation deficit of 2,501 nights of accommodation. The staging of redevelopment, and delivery of market-rate housing alongside each stage of social housing, means that the net social housing will be just one dwelling upon the completion of Stage 1. As such, it is only with the delivery of Stages 2, 3, and 4 that the project begins to recover the social housing accommodation deficit in a significant way (). The net social housing accommodation delay is, therefore, six to seven years following the completion of Stage 1 and net social housing interval approximately 16 years. If an alternative model was adopted and Stage 1 was developed as 100% social housing – all 765 dwelling rather than 259 – the results would be different. Bringing forward the construction of this additional 506 social housing dwellings into Stage 1 (from Stages 3, 4 and 5) would shorten the net social housing accommodation delay and therefore net social housing accommodation interval by five years.

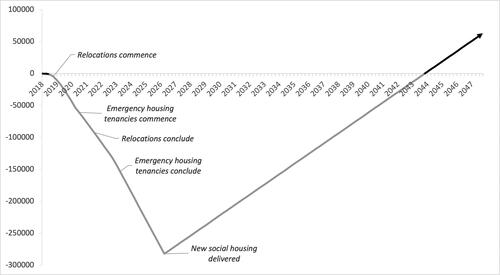

4.2. Arncliffe

While smaller in scale than Ivanhoe, the Arncliffe project is also characterized by a long tenant relocation process (three years and nine months between the first and last relocation) and lengthy gap between the commencement of relocations and the delivery of new social housing (nine years). LAHC expects the 180 new social housing dwellings to be completed in 2026, four to five years are after the final relocation. Our calculations reveal the total social housing accommodation deficit to be 288,830 nights, with each relocation having, on average, social housing accommodation deficit of 2,675 nights of accommodation. Of our three case studies, the Arncliffe case presents the most severe impact on social housing supply, recording the longest net social housing accommodation delay. The modest net social housing (44 dwellings) leads to a net social housing accommodation delay of 18 years. With social housing expected to become available in 2026, the net social housing interval is 26 years (). One caveat here is that the project demolished and replaced homes that were significantly older than those in Ivanhoe and Glebe, and thus may be assumed to have been lower quality.

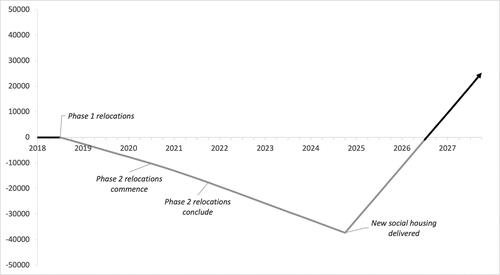

4.3. Glebe

The Glebe project will result in a positive impact on social housing supply more rapidly. Relocations from 17 to 31 Cowper St were completed in July-August of 2018 and from 2A to 2D Wentworth Park Rd between July 2020 and November 2021. The smaller number of relocations presumably made the process much quicker. Furthermore, the first phase of relocations was likely aided by the completion of the new social housing complex on the opposite side of Cowper St (as noted above), which provided new dwellings in the immediate vicinity for residents to move into. However, despite the smaller scale of this project (75 gross social housing and 57 net social housing), the construction time is comparable to the first stage of the Ivanhoe and Arncliffe projects. This may be due to more complex site characteristics – being smaller and located in a denser neighborhood – though on this we can only speculate. The Glebe project is calculated to have a total social housing accommodation deficit of 39,256 nights, with each relocation having, on average, a social housing accommodation deficit of 2,181 nights of accommodation. With a smaller deficit and substantial uplift in social housing we calculate a net social housing accommodation delay of 1.9 years and net social housing accommodation interval of nine years ().

5. Discussion and conclusion

A growing number of estate renewal projects are justified on grounds that they will improve social housing supply quantitatively (via gross and net social housing supply) as well as qualitatively (dwelling quality). Yet when the system-wide impacts of tenant relocation and dwelling demolition are included in understandings of the impact of estate renewal – what we have termed the social housing accommodation deficit – then claims around improved supply are more problematic. A positive quantitative impact on social housing supply does not occur with the completion of the project and delivery of net social housing but only after this social housing accommodation deficit has been made up – what we have termed the net social housing accommodation delay. To understand the impact of estate renewal on social housing supply, we must therefore measure the net social housing accommodation interval – the period between the first relocation (and thus commencement of a social housing accommodation deficit) and the end of the net social housing accommodation delay.

Our analysis has several further implications, the first of which is straightforward: estate renewal projects that deliver a larger proportional social housing uplift yield better social housing supply outcomes (i.e. shorter net social housing accommodation interval) than those which produce a smaller proportional social housing uplift. This is illustrated by comparing Glebe (317% uplift and 9 year net social housing accommodation interval) with Arncliffe (32% uplift and 26 year net social housing accommodation interval). These cases resulted in comparable net social housing, but fewer relocations in Glebe meant that the project produced a much smaller social housing accommodation deficit.

A second implication is that the extent of the impact of estate renewal on the social housing system is influenced by the delivery model adopted. While the redevelopment of the Ivanhoe estate will also produce a significant proportional social housing uplift (270%), it will have a much longer net social housing accommodation interval (16 years). Here, the combination of social mix ambitions and a finance and delivery model requiring cross-subsidization of new social housing with market-rate development at each stage will delay almost all net social housing until the second and later project stages. As we discussed in the previous section, an alternative delivery model that brought forward social housing into Stage 1 would shorten the project’s net social housing accommodation interval by five years, while delivering the same tenure mix upon project completion.

The Arncliffe estate was deemed to have a lower capacity for densification than Ivanhoe. As a result, the mixed-tenure delivery model resulted in significantly greater negative impact on social housing supply – a net social housing accommodation interval of 26 years compared to Ivanhoe’s 16 years. Notably, neither the Arncliffe nor Ivanhoe projects achieved the former government’s target mix of 30% social housing – the new social housing proportion will be 24% in the former and 28% in the latter – yet the net social housing and proportional social housing uplift in Ivanhoe is far greater. As such, a further implication is that tenure mix targets must take into account both net social housing and proportional social housing uplift. The latter was large in Glebe because all dwellings in the new scheme will be social housing, following community opposition to the original mixed-tenure proposal. Had the new social housing proportion been approximately 30%, then the results would have been drastically different.

A fourth implication relates to the benefits of staging renewal projects, where relocation and redevelopment occur concurrently. This would differ from the renewal model adopted at both Arncliffe and Ivanhoe, where all relocations were completed before any redevelopment activity commenced. As we have discussed, this staging model is not uncommon and has been recognized as ‘best practice’ (e.g. Shelter NSW et al., Citation2017), but it does have consequences for private sector development feasibility. While we have not investigated an estate renewal project that stages relocation alongside redevelopment (due to lack of available data), our analysis suggests that staged projects that deliver a significant proportional social housing uplift in the early stages of development, and where existing tenants are moved into these new social housing dwellings directly from homes that are to be demolished, has the potential to limit the system-wide impacts of estate renewal as few residents move into other social housing off the estate. This approach also has the potential to mitigate social impacts of tenant relocation.

Our analysis problematizes claims regarding increasing social housing supply through estate renewal. Our findings caution against projects that deliver a small proportional social housing uplift, given potentially significant long-term impacts of the wider social housing system. There are many large estate renewal projects in the pipeline in Australia, and our measures provide important insights into their long-term impacts. The largest project on the horizon is the renewal of the Waterloo estate, in inner-south Sydney. Redevelopment of this 2,012 dwelling estate is proceeding in three stages (Waterloo South, Central and North), with the first stage increasing social housing from 749 units to approximately 900 (net social housing of 151 dwellings and proportional social housing uplift of 20%) out of approximately 3,000 total dwellings. While staging relocations within Waterloo South may mitigate some of the impact on social housing supply, the proportional social housing uplift is below that recorded for our case studies. Furthermore, indicative plans for subsequent stages would produce far worse outcomes. Waterloo Central and North currently comprise 1,263 public housing dwellings and, under the plans of the previous NSW Government, would be redeveloped into approximately 4,200 dwellings, 30% of which would be social housing. This would deliver approximately 1,260 gross social housing and a net social housing loss of three dwellings. The renewal of the entire Waterloo estate would thus deliver only 148 net social housing and proportional social housing uplift of just 7%. While it is impossible to calculate a social housing accommodation deficit without tenant relocation and dwelling completion dates, these figures suggest the current renewal plans for Waterloo will result significant and long-term negative impacts on the wider social housing system in NSW. Likewise, the current Victorian Government’s plan to renew the 44 remaining public housing towers in Melbourne will require around 10,000 relocations and has a proportional social housing uplift target of just 10% (Premier of Victoria, Citation2023). The scale of this renewal program together with the low target raises serious questions about its benefits, given it is likely to generate a very large social housing accommodation deficit and have a net social housing accommodation interval of many decades.

More fundamentally, our findings problematize the reliance on estate renewal for increasing social housing supply. If housing authorities were to significantly expand social housing supply through other means, then the quantitative impacts of estate renewal on social housing supply may not need to be examined. Housing authorities might then select the lowest quality housing stock for renewal rather than estates with greater capacity for intensified development led by the private sector. Given the significant carbon footprint of the construction industry, environmental impacts of building waste, and substantial embodied carbon within estates, this would be a model better suited to the climate crisis.Footnote12 However, such a change in direction will require significant reinvestment (Lawson et al., Citation2018).

In this paper we have presented a set of new measures and methods for examining the complexities of the renewal process and accounting for its systemic impacts. These measures and methods are internationally relevant, and increasingly so, as governments and communities throughout the Global North grapple with the challenges of ageing social housing and growing need. Others may wish to adopt them in either retrospective or prospective calculations for projects elsewhere, though we note there may be limitations vis-à-vis data availability. Indeed, there were several projects that we were unable to analyze as government agencies held no information about relocations. In one case, this was because relocations were managed by a CHP under the terms of the PPP, raising issues regarding the transparency and accountability of these organizations who are responsible for a growing share of the social housing stock. In other cases, there had been a lack of record-keeping – also highly problematic in that it prevents the examination of such projects in the way we have demonstrated. Better data collection would allow SHAs to adopt our measures to understand and compare the temporal and system-wide impacts of different projects. They may present an unwelcome challenge to the simple ‘more social housing’ arguments (i.e. net social housing) made by governments when justifying estate renewal, but nevertheless, these wider impacts must be incorporated in project design and planning. The impact of estate renewal beyond the estate much be acknowledged.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the generous and insightful comments of the three anonymous reviewers and guidance of editor Ed Ferrari. An earlier version of this paper also benefitted from the comments of participants at the 2023 Institute of Australian Geographers conference session, ‘Urban Geographies of Coexistence, Collaboration, and Complicity’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alistair Sisson

Alistair Sisson is a Macquarie University Research Fellow in the Discipline of Geography and Planning, Macquarie School of Social Sciences. He is an early career researcher whose work focuses on housing, gentrification, and urban development and planning.

Kristian Ruming

Kristian Ruming is a Professor and ARC Future Fellow in the Discipline of Geography and Planning, Macquarie School of Social Sciences. He is an urban and economic geographer with research interests centring on issues of urban governance, housing and planning.

Notes

1 We use the terms public, community and social housing throughout. In Australian housing policy, social housing refers to both state-managed public housing and non-profit managed community housing. While there are important differences between them, allocations are administered through a shared waiting list and rents set at a fixed proportion of gross household income in both.

2 Minister for Housing and Homelessness Rose Jackson stated via X (formerly Twitter) that the 82 Wentworth Park Road project would be ‘100% owned and managed public housing’ (See https://twitter.com/RoseBJackson/status/1666746159585525760).

3 NSW Labor leader Chris Minns became NSW Premier following the March 2023 election.

4 The Villawood and Redfern sites were both previously occupied by public housing but, following demolitions, were vacant lots for more than a decade when the Communities Plus projects were announced.

5 Between 2011 and 2023, under the Liberal-National Coalition Government, LAHC sold 7,628 properties for more than AU$3.5 billion total (McGowan, Citation2023). In 2024, the new Labor Government established Homes NSW, re-combining public housing asset and tenancy management functions; however, at the time of writing there has been no explicit change to this funding model.

6 In some parts of regional NSW, projects that led to a net reduction in social housing have continued, including 15–19 Crown St Wollongong and the Tolland Estate in Wagga Wagga (J. Dominguez, LAHC, personal communication, 27 September 2023).

7 Commonwealth Rent Assistance is a supplementary payment for individuals in receipt of income support who live in private rental housing. It is intended for individuals who lease a property in the private rental market but community housing tenants are also eligible. As a result, CHPs receive more revenue per tenant than SHAs, claiming their tenants’ supplementary payment in full on top of a fixed proportion of household income.

8 Several factors can impinge upon a tenant’s ‘right of return’. For instance, marketing material for new homes in the Arncliffe estate states that social housing tenants will be subject to a rigorous ‘fitness criterion’. Similarly, the Waterloo estate is subject to the Inner City Allocation Policy, which bars tenants with a drug manufacture or drug supply conviction from public housing in four inner-Sydney neighbourhoods. At the time of writing, it has not been clarified whether this policy will be applied to relocated tenants. Furthermore, estate renewal often reduces the number of larger dwellings, such that a household requiring three or four bedrooms may not be able to return due to the lack of suitable dwellings. This is especially problematic for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander households given larger average household sizes, partly due to social and kinship obligations to house extended family members and disproportionate rates of evictions and child removals making this necessary (see Milligan et al., Citation2011).

9 These numbers may overestimate the growth in social housing due to the NSW Government’s inclusion of CHP-run affordable housing in their figures in 2016 (Pawson, Citation2023; see Note 11).

10 Prior to 2010, waiting list data from Productivity Commission’s Reports on Government Services included transfer applications, so cannot be reliably compared to subsequent data.

11 ‘Affordable housing’ in NSW includes rental properties leased to a low- to moderate-income households for no more than 80% of market rate or for no more than 30% of gross household income. It is available to higher-income households than those eligible for social housing and it is not allocated through a waiting list. Properties are managed by non-government organizations, often but not exclusively CHPs.

12 In some cases, estate renewal might involve renovation, refurbishment and infill rather than demolition and redevelopment. Several such projects have been undertaken in the United Kingdom and Europe, most famously by French architects Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, and proposed in the Australian context by non-profit architecture practice OFFICE (OFFICE & McGarry, Citation2022a, Citation2022b).

References

- Architectus Group. (2020) 600–660 Elizabeth St, Redfern: Planning Proposal. Prepared for NSW Land and Housing Corporation.

- Arthurson, K. (1998) Redevelopment of public housing estates: The Australian experience, Urban Policy and Research, 16, pp. 35–46.

- Arthurson, K. (2002) Creating inclusive communities through balancing social mix: A critical relationship or tenuous link?, Urban Policy and Research, 20, pp. 245–261.

- Atkinson, R. & Kintrea, K. (2000) Owner-occupation, social mix and neighbourhood impacts, Policy & Politics, 28, pp. 93–108.

- August, M. (2015) Revitalization gone wrong: Mixed-income public housing redevelopment in toronto’s don mount court, Urban Studies, 53, pp. 3405–3422.

- Barnes, E., Writer, T. & Hartley, C. (2021) Social Housing in New South Wales – Report 1: Contemporary Analysis (Sydney: Centre for Social Impact, UNSW).

- Beazley, J. & Rose, T. (2023) Waterloo public housing tenants will be rehoused nearby after sale, NSW government pledges. The Guardian, May 17. Available from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/may/17/sale-of-waterloo-south-public-housing-will-see-residents-rehoused-nearby-nsw-government-pledges.

- Bridge Housing (n.d.) Redfern Place. Available from https://www.bridgehousing.org.au/properties/housing-development/redfern-place.

- Collins, N. (2006) An analysis of Minto Renewal Project. Undergraduate Thesis submitted as a partial fulfilment of the Bachelor of Planning Degree, Faculty of the Built Environment, University of New South Wales, November 2006.

- Crawford, B. & Sainsbury, P. (2017) Opportunity or loss? Health impacts of estate renewal and the relocation of public housing residents, Urban Policy and Research, 35, pp. 137–149.

- Darcy, M. (2020) Change Management: Social Housing Management Transfers Program Best Practice Report—Tenants’ Experience (Sydney: Tenants Union of NSW & Law and Justice Foundation of NSW).

- Darcy, M. & Rogers, D. (2016) Place, political culture and post–green ban resistance: Public housing in millers point, sydney, Cities, 57, pp. 47–54.

- NSW Department of Communities & Justice. (2024) Social housing waiting list data. Available from https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/housing/help/applying-assistance/social-housing-waiting-list-data.

- Eastgate, J. (2016) Issues for Tenants in Public Housing Renewal Projects: Literature Search Findings (2016 update) (Sydney: Shelter NSW).

- FPD Planning. (2023) Statement of environmental effects: 82 Wentworth Park Road, Glebe. Prepared on behalf of NSW Land and Housing Corporation.

- Galster, G. (2007) Should policy makers strive for neighborhood social mix? An analysis of the Western european evidence base, Housing Studies, 22, pp. 523–545.

- Gillespie, T., Hardy, K. & Watt, P. (2018) Austerity urbanism and olympic counter-legacies: Gendering, defending and expanding the urban commons in East London, Environment and Planning D, 36, pp. 812–830.

- Goetz, E. G. (2013) New Deal Ruins: Race, Economic Justice, and Public Housing Policy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

- Groenhart, L. & Burke, T. (2014) Thirty Years of Public Housing Supply and Consumption: 1981–2011, AHURI Final Report No. 231, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Gorrey, M. (2023) Waterloo estate plan rejigged to accommodate more social housing. Sydney Morning Herald, August 21. Available from https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/waterloo-estate-plan-rejigged-to-accommodate-more-social-housing-20230818-p5dxm9.html.

- Hayward, D. (1996) The reluctant landlords? A history of public housing in Australia, Urban Policy and Research, 14, pp. 5–35.

- Hughes, M. (2004) Community Economic Development and Public Housing Estates (Sydney: Shelter NSW).

- Jacobs, K. & Travers, M. (2015) Governmentality as critique: The diversification and regulation of the Australian housing sector, International Journal of Housing Policy, 15, pp. 304–322.

- Johnson, L. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2020) Regent Park redux: Reinventing public housing in Canada (Abingdon: Routledge).

- Joseph, M. L. (2006) Is mixed income development an antidote to urban poverty? Housing Policy Debate, 17, pp. 209–234.

- Judd, B. & Randolph, B. (2006) Qualitative methods and the evaluation of community renewal programs in Australia, Urban Policy and Research, 24, pp. 97–114.

- Kabisch, S., Poessneck, J., Soeding, M. & Schlink, U. (2022) Measuring residential satisfaction over time: Results from a unique long-term study of a large housing estate, Housing Studies, 37(10), pp. 1858–1876.

- Koziol, M. (2023) ‘Five years to get nowhere’: Minister slams Sydney council over housing impasse. Sydney Morning Herald, June 26. Available from https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/five-years-to-get-nowhere-minister-slams-sydney-council-over-housing-impasse-20230606-p5dea2.html.

- Koziol, M. (2024) How plans to build 3900 homes shrank to just 414 houses. Sydney Morning Herald, March 25. Available from https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/how-plans-to-build-3900-homes-shrank-to-just-414-houses-20240322-p5fegm.html.

- LAHC. (2023a) Airds-Bradbury Fact Sheet (Sydney: NSW Government).

- LAHC. (2023b) Claymore Fact Sheet (Sydney: NSW Government).

- LAHC. (n.d.a). Wollongong. NSW Department of Planning and Environment. Available from https://www.dpie.nsw.gov.au/land-and-housing-corporation/regional/crown-st,-wollongong.

- LAHC. (n.d.b). Villawood. NSW Department of Planning and Environment. Available from https://www.dpie.nsw.gov.au/land-and-housing-corporation/greater-sydney/villawood.

- LAHC. (n.d.c). West Ryde. NSW Department of Planning and Environment. Available from https://www.dpie.nsw.gov.au/land-and-housing-corporation/greater-sydney/west-ryde.

- Lawson, J., Pawson, H., Troy, L., van den Nouwelant, R. & Hamilton, C. (2018) Social Housing as Infrastructure: An Investment Pathway, AHURI Final Report No. 306, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Lees, L. (2014) The urban injustices of new labour’s “new urban renewal”: The case of the aylesbury estate in london, Antipode, 46, pp. 921–947.

- Lees, L., Butler, T., & Bridge, G. (Eds.) (2012) Mixed Communities: Gentrification by Stealth? (Bristol: Bristol University Press).

- Lees, L. & Ferreri, M. (2016) Resisting gentrification on its final frontiers: Learning from the heygate estate in london (1974–2013), Cities, 57, pp. 14–24.

- Lees, L. & Hubbard, P. (2022) “So, don’t you want Us here no more?” slow violence, frustrated hope, and racialized struggle on london’s council estates, Housing, Theory and Society, 39, pp. 341–358.

- London Assembly Housing Committee. (2015) Knock it Down or Do it Up? The challenge of estate regeneration (London: Greater London Authority).

- McGowan, M. (2023) Revealed: Sydney suburbs where billions of dollars worth of public housing was sold. Sydney Morning Herald, May 15. Available from https://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/revealed-sydney-suburbs-where-billions-of-dollars-worth-of-public-housing-stock-was-sold-20230510-p5d79k.html.

- Milligan, V., Gurran, N., Lawson, J., Phibbs, P. & Phillips, R. (2009) Innovation in Affordable Housing in Australia: Bringing Policy and Practice for Not-For-Profit Housing Organizations Together, AHURI Final Report No. 134, Melbourne, Australia: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Milligan, V., Phillips, R., Easthope, H., Liu, E. & Memmott, P. (2011) Urban Social Housing for Aboriginal People and Torres Strait Islanders: Respecting Culture and Adapting Services. AHURI Final Report No. 172 (Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute).

- Morris, A. (2018) Gentrification and Displacement: The Forced Relocation of Public Housing Tenants in Inner-Sydney (New York: Springer).

- Morris, A., Idle, J., Moore, J. & Robinson, C. (2023) Waithood: The Experiences of Applying for and Waiting for Social Housing (Sydney: Institute for Public Policy and Governance, University of Technology Sydney).

- Morris, A., Jamieson, M. & Patulny, R. (2012) Is social mixing of tenures a solution for public housing estates?, Evidence Base, 2012, pp. 1–21.

- Munro, K. (2011) Anger at Glebe housing proposal. Sydney Morning Herald, May 14. Available from https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/anger-at-glebe-housing-proposal-20110513-1emc2.html.

- Norris, M. & Hearne, R. (2016) Privatizing public housing redevelopment: Grassroots resistance, co-operation and devastation in three Dublin neighbourhoods, Cities, 57, pp. 40–46.

- NSW Department of Planning & Environment. (n.d.). Explorer Street, Eveleigh. Available from https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/plans-for-your-area/priority-growth-areas-and-precincts/explorer-street-eveleigh.

- NSW Department of Planning & Environment (2015) Herring Road, Macquarie Park finalization report (Sydney: NSW Government).

- NSW Department of Planning & Environment. (2018) Bayside Wests Precincts 2036: Arnliffe, Banksia and Cooks Cove (Sydney: NSW Government).

- NSW Government (2016) Future Directions for Social Housing in NSW. (Sydney: NSW Government).

- OFFICE & McGarry, M (2022a) Retain, Repair, Reinvest – Barak Beacon Estate: Feasibility Study and Alternative Design Proposal. (Melbourne: OFFICE).

- OFFICE & McGarry, M (2022b) Retain, Repair, Reinvest – Ascot Vale Estate Feasibility Study and Alternative Design Proposal. (Melbourne: OFFICE).

- Pawson, H. (2023) The housing and homelessness crisis explained in 9 charts. The Conversation. Available from https://theconversation.com/the-housing-and-homelessness-crisis-in-nsw-explained-in-9-charts-200523.

- Pawson, H. & Gilmour, T. (2010) Transforming australia’s social housing: Pointers from the British stock transfer experience, Urban Policy and Research, 28, pp. 241–260.

- Pawson, H. & Pinnegar, S. (2018) Regenerating Australia’s public housing estates, in: K. Ruming (Ed) Urban regeneration in Australia: Policies, processes and projects of contemporary urban change, pp. 311–223 (London: Routledge).

- Pinnegar, S., Liu, E. & Randolph, B. (2013) Bonnyrigg Longitudinal Panel Study First Wave: 2012 (Sydney: UNSW City Futures Research Centre).

- Popkin, S., Levy, D. & Buron, L. (2009) Has hope VI transformed residents’ lives? New evidence from the hope VI panel study, Housing Studies, 24, pp. 477–502.

- Porter, L., Davies, L., Ruming, K., Kelly, D., Rogers, D. & Flanagan, K. (2023) Drivers and Outcomes of Public Housing Tenant Relocation. AHURI Final Report No. 413 (Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute).

- Premier of Victoria (2023) Australia’s Biggest Ever Urban Renewal Project. September 24. Available from https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/australias-biggest-ever-urban-renewal-project?fbclid=IwAR3nexXWmTUpni0STmAkoEGHAqmDQWXoE1Puhm1G2WL-sFWhOkahxTw2eXQ.

- Productivity Commission (2005) Report on Government Services 2005 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia).

- Productivity Commission (2009) Report on Government Services 2009 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia).

- Productivity Commission (2013) Report on Government Services 2013 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia).

- Productivity Commission (2018) Report on Government Services 2018 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia).

- Productivity Commission (2024) Report on Government Services 2024 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia).

- Romyn, M. (2020) London’s Aylesbury Estate: An oral history of the “concrete jungle” (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Ruming, K. J., Mee, K. J. & MGuirk, P. M. (2004) Questioning the rhetoric of social mix: courteous community or hidden hostility?, Australian Geographical Studies, 42, pp. 234–248.

- Ruming, K. & Melo Zurita, M. D L. (2020) Care and dispossession: Contradictory practices and outcomes of care in forced public housing relocations, Cities, 98, pp. 102572.

- Ruming, K. & Melo Zurita, M. D L. (2024) Care, urban regeneration and forced tenant relocation: the case of Ivanhoe social housing estate, Sydney, Housing Studies, 39, pp. 812–830.

- Shelter NSW, Tenants’ Union of NSW, & UNSW City Futures Reserc Centre (2017) A Compact for Renewal: What tenants want from renewal (Sydney: Shelter NSW, Tenants’ Union of NSW & UNSW City Futures Research Centre).

- Sisson, A. (2024) Public housing and territorial stigma: towards a symbolic and political economy, Housing Studies, 39, pp. 1199–1218.

- SGCH. (n.d.). Riverwood North Urban Renewal Project. St George Community Housing. Available from https://www.sgch.com.au/projects/washington-park-riverwood/.

- Stubbs, J., Foreman, J., Goodwin, A., Storer, T. & Smith, T (2005) Leaving Minto: A Study of the Social and Economic Impacts of Public Housing Estate Redevelopment (Sydney: Minto Resident Action Group, Social Justice & Social Change Research Centre UWS, St Vincent de Paul Society, UnitingCare Burnside & Other Services).

- Sydney Local Health District (n.d.). Homelessness and rough sleeping. Available from https://slhd.health.nsw.gov.au/homelessness/about.

- Troy, P. N. (2012) Accommodating Australians: Commonwealth Government Involvement in Housing (Canberra: Federation Press).

- Vale, L. J. (2018) After the Projects: Public Housing Redevelopment and the Governance of the Poorest Americans (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Wang, J. (2023) Protestors storm Sydney public housing unit in fight against redevelopment. News.com.au, June 7. Available from https://www.news.com.au/finance/real-estate/sydney-nsw/protesters-storm-sydney-public-housing-unit-in-fight-against-redevelopment/news-story/f1f878eb2477c51a3bffb215b0e35ce9.

- Watt, P. (2016) A nomadic war machine in the metropolis, City, 20, pp. 297–320.

- Watt, P. (2021) Estate Regeneration and Its Discontents: Public Housing, Place and Inequality in London (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Watt, P. (2023) Taking a long view perspective on estate regeneration: Before, during and after the new deal for communities in london, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 38, pp. 141–170.

- Watt, P., & Smets, P. (Eds.) (2017) Social Housing and Urban Renewal: A Cross-National Perspective (Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited).

- Wood, M., Randolph, B. & Judd, B. (2002) Resident participation, social cohesion and sustainability in neighbourhood renewal: Developing best practice models (Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute).

- Woodward, R. (1997) Paradise lost: Reflections on some failings of Radburn, Australian Planner, 34, pp. 25–29.

- Wynne, L., Ruming, K., Shrestha, P. & Rogers, D. (2022) The marketization of social housing in New South Wales, in: G. Meagher, A. Stebbing, & D. Perche, (Eds) Designing Social Service Markets: Risk, Regulation and Rent-Seeking, pp. 269–300 (Canberra: ANU Press).

- Yates, J. (2013) Evaluating social and affordable housing reform in Australia: Lessons to be learned from history, International Journal of Housing Policy, 13, pp. 111–133.

- Yates, J. (2014) Protecting housing and mortgage markets in times of crisis: A view from Australia, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 29, pp. 361–382.

- Zanardo, M. & Boyd, N. (2019) Affordable Housing in Sydney: Architecture Guide Map (Sydney: Studio Zanardo).