Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the association between extra-curricular activities and risky sexual and illicit drug use behaviours among youth (12–22 years old) in South Africa. The study uses nationally representative data. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression models are used. Results show that a high percentage of youth engage in at least one type of risky sexual behaviour (33.84%) and have used at least one type of illicit substance (7.79%). Sports (about 60%) and youth groups (about 15%) are the most popular forms extra-curricular activities. Further, the odds of risky sexual behaviour are higher for youth who participate in sports (OR = 1.29, p-value < .05) and youth groups (OR = 1.58, p-value < .05). While youth who engage in other, undefined extra-curricular activities (OR = 2.11, p-value < .05) and sports (OR = 1.03, p-value < .05) have higher odds of illicit drug use. There is need to monitor and evaluate local extra-curricular activities to prevent risky behaviours among youth.

Introduction

Risky behaviours among youth are a known problem with devastating consequences. Risky sexual behaviours such as lack of condom use, multiple concurrent sexual partners and transactional sex are known to result in HIV infection and unintended pregnancy. In South Africa, rates of these behaviours are high with one study of young males in Soweto reporting only 44% had used condoms at last sexual intercourse and another studying finding that 46.3% of youth in the country reported two or more concurrent sexual partners (Kamndaya, Thomas, Vearey, Sartorius, & Kazembe, Citation2014; Mhlongo et al., Citation2013). Another type of risky behaviour that has detrimental consequences is illicit drug use. These behaviours are known to result in dependency, physical health diseases including liver and kidney failure as well as social consequences such as the loss of employment, family separation and even incarceration (Bachman, Wadsworth, O’Malley, Johnston, & Schulenberg, Citation2013; Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, Citation2013; Pope et al., Citation2013; Riley et al., Citation2016). Among young adults in South Africa, the rates of illicit drug use are 8.9% for the use cannabis, .4% use opiates, .8% cocaine and .9% amphetamine-type stimulants (Liebenberg, du Toit-Prinsloo, Steenkamp, & Saayman, Citation2016).

Alternative behaviours, which are encouraged to reduce risky behaviours, include youth participation in extra-curricular activities. These are activities which take place outside of school, either in the afternoons, on weekends or during vacation periods, and do not contribute to grade progression and are not academic in focus. As such these activities include participation in various types of sports, youth groups, choirs and theatre groups to name a few. In South Africa, it is found that, only 51.7% of youth aged 16 to 20 years old participated in sports and recreational activities (Department of Sport & Recreation, Citation2005). And the benefits of these extra-curricular activities, especially sports, for the development of children and youth have been well-documented (Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2006; Merkel, Citation2013; Schumacher Dimech & Seiler, Citation2011). One of the most common health benefits of sports participation is the reduced risk of obesity and other diseases if done consistently and committedly (Mokabane, Mashao, Van Staden, Potgieter, & Potgieter, Citation2014). Emotional intelligence and improved goals-setting skills are also noted benefits that youth gain from participating in sports (Merkel, Citation2013).

However, sports and other social activities also provide enabling environments for youth to engage in various risky behaviours. An extensive amount of global literature has addressed the relationship between sports participation and alcohol and drug use among youth (Jernigan, Noel, Landon, Thornton, & Lobstein, Citation2017; Lisha & Sussman, Citation2010; Peretti-Watel et al., Citation2003; Sønderlund et al., Citation2014). In one systematic review on the topic a positive relationship was found between alcohol use and sports in 82% (n = 17) of the longitudinal studies included (Kwan, Bobko, Faulkner, Donnelly, & Cairney, Citation2014). Other studies of adolescents and university students also found a positive relationship between sports and illicit drug use, including the use of steroids and other performance enhancers (Laure, Lecerf, Friser, & Binsinger, Citation2004; Lisha & Sussman, Citation2010; Peretti-Watel et al., Citation2003). These activities take place outside of the parental home and while some adult supervision is apparent, parents are not convinced these are safe environments. The results of two studies found that parents prohibit their children from extra-curricular activities because parents protect children from the various forms of risky behaviours that are perceivably occurring within these environments (Kinsman et al., Citation2015; Kubayi, Toriola, & Monyeki, Citation2013). These qualitative studies examined the parent’s perceptions however, no research has looked quantitatively at the relationship between extra-curricular activities and risky behaviours among adolescents in South Africa, despite there being global research that was done (Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell, & Dintcheff, Citation2007; Han, Lee, & Park, Citation2017; Hoffmann, Citation2006; Rambaree, Mousavi, & Ahmadi, Citation2017).

The purpose of this study therefore is to determine if a relationship between extra-curricular activities and risky behaviours (sexual and illicit drug use) among adolescents in South Africa exists, thus addressing the tension between the existing literatures suggesting extracurricular involvement is protective and parent’s perceptions that it is a risk factor.

The need for this research lies in our need to curtail risky behaviours among youth and encourage healthy and safe transitions to adulthood. Youth who engage in risky behaviours face poor health and development outcomes which will impact the individual and the country’s economic and social development. And while efforts to curtail these behaviours have been put in place, such as the implementation of Life Orientation as a mandatory part of school curricula in the country, its effectiveness has not resulted in drastic reductions of these behaviours.

Methods

Study design

The study uses the South African Youth Lifestyle Survey 2009 (SAYLS) from the Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention (CJCP). The data is a nationally representative; cross sectional survey sampling young people aged 12–22 years old. All geographic areas and race or population groups are represented.

Sample

The sample for this study are youth between the ages of 12 and 22 years old who have ever engaged in a risky sexual behaviour or have ever used an illicit substance. Both males and females are analysed and all population groups are included. The total number of youth in the sample with completed information is (N) 10,502,705 of which (N) 3,554,390 reported engaging in at least one type of risky sexual behaviour and (N) 818,036 reported ever trying at least one illicit substance. The survey shows a weighted per cent of 36.62% of females and 27.60% of males had not used condoms at last sexual intercourse and 6.42% of females and 33.22% of males had more than one concurrent sexual partner. Further 4.78% of females and 10.78% of males reported ever using an illicit substance, which does not include alcohol consumption or cigarette smoking. The latter behaviours were excluded from the study because extensive research has been done on adolescents and the alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking. This literature confirms that these behaviours predominantly start during adolescence and as such would cause confounding in the study (Field et al., Citation2014; Parrinello et al., Citation2015). Further to this, South African law regulations allow for the consumption of alcohol and purchasing cigarettes from the age of 18 years old, whereas illicit drugs are strictly prohibited at all ages (Groenewald et al., Citation2007; Parry, Citation2010). For this reason, the study is focussing on behaviours which are completely prohibited throughout the age-group.

Study variables and descriptions

The outcomes in this analysis are risky sexual behaviours and illicit substance use. To measure risky sexual behaviour ‘condom use at last sex’ (condom use) and ‘number of sexual partners respondent had at the time of the interview’ (multiple sexual partners) are used. For condom use, the variable is dichotomous with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses. For multiple sexual partners the survey collects up to five concurrent partners and in this study is dichotomised into ‘one’ or ‘two or more’ partners.

To measure illicit substance use, respondents who answered positively (‘yes’) to having ever used any of the following types of drugs are coded as ‘yes’: marijuana, cocaine, sniffed or inhaled glue, mandrax, heroin, amphetamines and tik (a colloquial name for crystal methamphetamine).

The main predictor variable in the study is extra-curricular activities. The survey asks respondents if they participate in any (or all) of the following: youth groups, sports, choir groups, drama or theatre groups, and/or other. Each of these types of activities have ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses. All five activities are used in the analyses. A composite measure which shows ‘none’, ‘one’ or ‘two or more’ activities is created and tabulated against risky sexual and illicit substance abuse behaviours to test for an association.

The control variables in the study are the demographic characteristics of the respondents. These include age- groups, sex, population group, type of place of residence and current school attendance. The study also includes two measures of socioeconomic status which are the ‘number of household income earners’ and ‘household has enough to eat’ (yes/no) In addition, a measure of self- esteem has been added and this is the question in the survey which asks if the respondent has ‘clear goals for the future’. The four-point Likert scale of responses from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ have been grouped into two categories ‘disagree’ (for ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’) and ‘agree’ (for ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and analytical techniques are used. Under the descriptive statistics, the study population are described using frequency distributions and chi- square cross- tabulations. The data were weighted to account for the sample design and the response rate in the survey so as to provide a nationally representative estimate for the study. Rates of risky behaviour are also calculated per 1000 weighted youth in the country.

Adjusted logistic regression models were used to investigate the association between the risky sexual and illicit drug use behaviours and the respondent’s participation in extra-curricular activities while controlling for their demographic characteristics. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each risky behaviour was calculated.

Results

Sample characteristics

shows the characteristics of the adolescents in the sample. About 46% of the sample is 15–19 years old and 50.14% are male. The African population group make up 83.75% of all respondents. Approximately 46% of the adolescents reside in rural areas and about 71% are still in school. Finally, almost 99% of all adolescents have clear goals for the future.

Table 1. Characteristics of the respondents in the study.

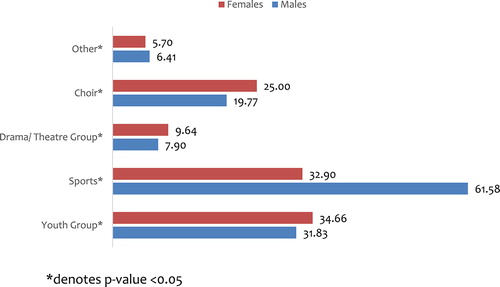

Males participate in sports more than any other activity and more than females at over 60% (). Females participate in youth groups (34.66%), Drama or Theatre groups (9.64%), and choir (25%) more than males.

Prevalence of risky behaviours

shows the percentage distribution and rates (per 1000 youth) of risky behaviours by the type of behaviours among youth in the study. Overall, about 120 youth per 1000 (32.06%) did not use condoms at last sexual intercourse. Among females the rate is higher at 136.16 per 1000 (36.62%) and for males it is 104.43 per 1000 (27.60%). In the entire sample the rate of multiple concurrent sexual partnerships is 64 youth per 1000 (20.44%), with females having a much lower rate at 20 per 1000 (6.42%) and males have a much higher rate at about 109 per 1000 youth males (33.22%). The rate for illicit drug use is 78 per 1000 youth (7.79%) with males again having a much higher rate (108 per 1000 and 10.78%) than females (48 per 1000 and 4.78%).

Table 2. Percentage distribution and rates of risky behaviours by type and sex of youth.

Determinants of risky behaviours

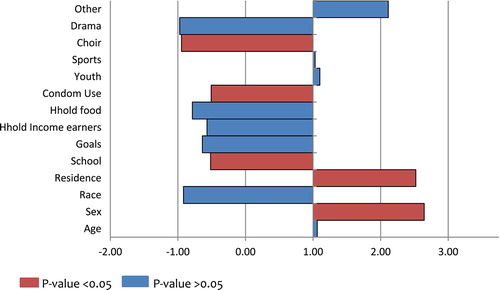

shows the adjusted odds ratios of risky sexual behaviour (at least one type) by the characteristics of adolescents in South Africa. Age shows that older youth have higher odds of risky sexual behaviour (OR = 2.07) and is statistically significant (p-value < .05). Also other racial groups, which include Coloured, White and Indian or Asian have lower odds (OR = .18) of risky sexual behaviour compared to the Reference Group of African youth. The more household income earners there are the less likely it is youth will engage in risky sexual behaviours (OR = .56). Participation in youth groups (OR = 1.58) and sports (OR = 1.29) also shows an increase likelihood in risky sexual behaviour (p-values < .05). While not attending school (OR = 1.81) and not have goals for the future (OR = 1.24) produce a higher likelihood of risky sexual behaviours (p-values < .05).

Figure 2. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) of risky sexual behaviour by characteristics of adolescents in South Africa.

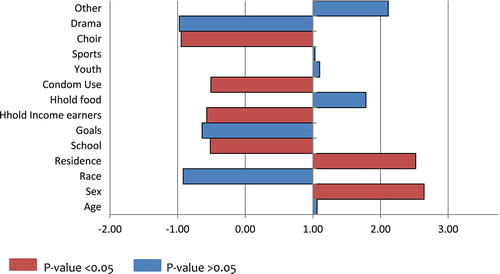

shows the odds of illicit drug use by the characteristics of the respondents. The graph shows that sex (females, OR = 2.64), place of residence (rural, OR = 2.52), participation in sports (OR = 1.03) and other (OR = 2.11) extra-curricular activities are associated with increased likelihood of illicit drug use, with ORs greater than 1.00, and these variables are statistically significant (p-value < .05). While not attending school (OR = .51) and using a condom at last sex (OR = .51) are associated with lower odds of illicit drug use also with statistically significant p-values.

Discussion

Risky behaviours among youth have dire short and long term consequences. Risky sexual behaviours are associated with STI contraction including HIV/AIDS, and illicit drug use is associated with long-term addiction and liver disease, among others. This study was done to address the association between types of risky behaviours among youth because (1) extra-curricular activities are being perceived by parents as enabling environments and (2) the slow reduction of risky behaviours among youth in the country.

An association was found between extra-curricular activities and risky behaviours among youth. These activities take place around other youth, in an environment where peer pressure is rife. In addition, research shows that some extra-curricular activities are not adequately supervised by adults, while other research has shown that quality of supervision is low and youth are often left unattended (Eccles & Templeton, Citation2002; Marsh & Kleitman, Citation2002; Zarrett & Eccles, Citation2009). In environments where this is true, the possibility that youth engage in illicit drug use and risky sexual behaviours is high. However, extra-curricular activities are found to be beneficial to youth self-esteem and discipline, and are a popular means of out-of-school care for parents who have work commitments in the afternoons but want to keep their children away from negative peer influences (Mahoney, Citation2000; Mahoney & Stattin, Citation2000; Shannon, Citation2006). The results of this study show that this is not always the case and there is a need to reconsider and monitor the types of extra-curricular activities of adolescents.

Rates of risky sexual behaviours are high with about one-third of youth reporting either lack of condom use, multiple sexual partners or both. This is consistent with a host of literature on South Africa and further illustrates the dire need for preventative measures in the country (Gouws, Citation2015; Harling et al., Citation2014; Zuma et al., Citation2016). And while programmes are in place, such as LoveLife, research shows that less than a third (26.8%) of adolescents and youth are aware of the dangers of risky sexual behaviours (Zuma et al., Citation2016). Among youth, who are not yet employed, the economically-driven motivations for multiple sexual partners and the transactional nature of these relationships including the lack of condom use have been documented (Deane & Wamoyi, Citation2015; Dunkle et al., Citation2007; Leclerc-Madlala, Citation2003). Other research has pointed to male adolescents not enjoying the feel of condoms and persuading young partners not use them (Crosby et al., Citation2013). These explanations, along with the susceptibility of adolescents to peer-pressure could explain the high rates of risky sexual behaviours in the country.

Illicit drug use reporting is not as high as risky sexual behaviours. This could be related to the legal environment surrounding the use of illicit substances which does not exist for risky sexual behaviours. This is in accordance with other nationally representative studies, that found that 58.4% of youth aged 15–24 years old use condoms at last sexual intercourse and used illicit drug use reporting was low at 6% for heroin and 12% for marijuana (Reddy et al., Citation2010; Zuma et al., Citation2016). However, literature has also found that, illicit drug use among adolescents and youth are largely under-reported (Nichols et al., Citation2014; Weybright, Caldwell, Wegner, Smith, & Jacobs, Citation2016). This is confirmed in research done by South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU) which reports that 8% (10–14 years old) and 20% (15–19 years old) of all patients who reported for treatments were adolescents. In South Africa, along with a majority of countries globally, the use of many illicit substances, including those which can be accessed without a prescription, is illegal (Republic of South Africa, Citation1992). Therefore, there would be underreporting of the use of such substances, not only by youth but by adults too and research has shown that this is fairly common (Degenhardt, Hall, & Gartner, Citation2015). Further, while social stigmas around lack of condom use and multiple sexual partners are lower, as seen by the recent popularity of ‘sugar daddies’, now referred to as ‘blessers’ on social media (Dube, Citation2016), the practice of illicit drug use remains highly stigmatised, which could also account for the lower reporting of these behaviours.

There are several strengths of this study. First, the study uses nationally representative cross- sectional data to provide empirical evidence of the relationship between behaviours. Given the qualitative studies of parents presented above, this study adds as the next pragmatic step which is to determine a statistical relationship. Second, the survey used has a large of sample of youth who answered questions relating to their participation in extra-curricular activities as well as risky behaviours such as illicit drug use and lack of condom use, among others. This large sample has allowed for more robust measurement the relationship between extra-curricular activities and risky behaviours. Finally, the study fills a gap in the literature which has largely been ignored. To the knowledge of the authors, no study like this has been done in South Africa. And this will inform policies and programmes in the country including the National Youth Policy 2015- 2020, which endeavours to address issues prohibiting youth development and the LoveLife campaign which works with youth in local communities to reduce risky and illegal behaviours.

The following limitations for the study can be noted. First, since the data are cross-sectional, it could not be determined if extra-curricular activities are causal environments for risky behaviours. Second, as noted above the study is subject to social desirability bias with youth not only underreporting illicit drug use but also engagement in risky sexual behaviours. Third, the study does not control for youth susceptibility to peer-pressure which would help explain this relationship further. Finally, the data used for the study are not recent. However, the source is extensive in its collection of data on risky behaviours and extracurricular activities. Also, the results remain relevant as both risky behaviours and involvement in extracurricular activities have not substantially declined in the period since the survey was conducted and the present date.

Conclusion

There is need to revisit the so-called ‘protective environments’ which are designed to discourage risky behaviours among youth. While it is agreed that youth need guidance, as well as healthy and safe activities to ensure their successful development, the fact that risky behaviours persist despite the involvement of youth in extra-curricular activities cannot be ignored. For this reason, more research into the social environments that are perceived as safe need to be addressed and possibly re-designed. This result adds a novel contribution to the field of youth health-behaviour research because it suggests examining protective environments as risk-enabling environments.

Related to this, policies and programmes in the country that encourage positive and safe adolescent development such as the National Youth Policy 2015–2020 (Citation2008) and the LoveLife campaign, among others, need to re-assess what is viewed as risky undertakings. That is not to say that extra-curricular activities should be discredited and youth should be kept away from participating in sports and youth groups. After all, these activities do add benefit to physical and mental development. Instead, programmes should place more emphasis on monitoring and evaluating existing extra-curricular activities and addressing the quality of supervision at these various forms of activities to avoid situations where harmful behaviours can occur.

Future research that would assist in a better understanding of this relationship should take a qualitative approach whereby youth are questioned regarding the aspects of these settings that enable risky behaviours. Qualitative research on the parents, sports coaches and other supervisors of adolescents in extra-curricular activities should be conducted to better understand the challenges they face in providing proactive and protective environments for their children. In addition, longitudinal studies in the South African context should be conducted to determine if extra-curricular environments are the cause of risky behaviours. Such research would better inform ways to prevent risky behaviours and suggestions made by youth themselves, would help in strengthening controls within these environments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by South African National Research Foundation [grant number TTK14050967041].

Notes on contributors

Nicole De Wet is a Senior Lecturer in Demography and Population Studies, Schools of Social Sciences and Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Her research interests are in adolescent health and health-related behaviours in sub-Saharan Africa.

Takalani Muloiwa is a institutional researcher and BI analyst at University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Her research interests are in adolescent and youth development in South Africa.

Clifford Odimegwu is a professor of Demography and Population Studies, Schools of Social Sciences and Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. His research interests are in family demography, and sexual and reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa.

References

- Bachman, J. G., Wadsworth, K. N., O’Malley, P. M., Johnston, L. D., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2013). Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. New Jersey: Psychology Press.

- Barnes, G. M., Hoffman, J. H., Welte, J. W., Farrell, M. P., & Dintcheff, B. A. (2007). Adolescents’ time use: Effects on substance use, delinquency and sexual activity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(5), 697–710.10.1007/s10964-006-9075-0

- Boden, J. M., Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2013). Alcohol misuse and relationship breakdown: Findings from a longitudinal birth cohort. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 133(1), 115–120.10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.023

- Crosby, R. A., Milhausen, R. R., Mark, K. P., Yarber, W. L., Sanders, S. A., & Graham, C. A. (2013). Understanding problems with condom fit and feel: An important opportunity for improving clinic-based safer sex programs. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(1–2), 109–115.10.1007/s10935-013-0294-3

- Deane, K., & Wamoyi, J. (2015). Revisiting the economics of transactional sex: Evidence from Tanzania. Review of African Political Economy, 42(145), 437–454.10.1080/03056244.2015.1064816

- Degenhardt, L., Hall, W. D. U., & Gartner, C. E. (2015). The epidemiology of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use and their contribution to the burden of disease. Addiction Medicine: Principles and Practice, 61(279,000), 8–21.

- Department of Sport and Recreation. (2005). Participation patterns in sport and recreation activities in South Africa: 2005 survey. Pretoria: Formeset Printers Cape (Pty) Ltd.

- Dube, Y. (2016). Social media fuels transactional sex. Chronicle. Online: http://www.chronicle.co.zw/social-media-fuels-transactional-sex/

- Dunkle, K. L., Jewkes, R., Nduna, M., Jama, N., Levin, J., Sikweyiya, Y., & Koss, M. P. (2007). Transactional sex with casual and main partners among young South African men in the rural Eastern Cape: Prevalence, predictors, and associations with gender-based violence. Social Science & Medicine, 65(6), 1235–1248.10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.029

- Eccles, J. S., & Templeton, J. (2002). Extracurricular and other after-school activities for youth. Review of Research in Education, 26, 113–180.10.3102/0091732X026001113

- Field, A. E., Sonneville, K. R., Crosby, R. D., Swanson, S. A., Eddy, K. T., Camargo, C. A., … Micali, N. (2014). Prospective associations of concerns about physique and the development of obesity, binge drinking, and drug use among adolescent boys and young adult men. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(1), 34–39.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2915

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 698–713.

- Gouws, E. (2015). Trends in HIV prevalence and sexual behaviour among young people aged 15–24 years in countries most affected by HIV. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 86(Suppl 2), ii72–ii83.

- Groenewald, P., Vos, T., Norman, R., Laubscher, R., Van Walbeek, C., Saloojee, Y., … Bradshaw, D. (2007). Estimating the burden of disease attributable to smoking in South Africa in 2000. South African Medical Journal, 97(8), 674–681.

- Han, S., Lee, J., & Park, K.-G. (2017). The impact of extracurricular activities participation on youth delinquent behaviors: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Adolescence, 58, 84–95.10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.05.006

- Harling, G., Newell, M.-L., Tanser, F., Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S., & Bärnighausen, T. (2014). Do age-disparate relationships drive HIV incidence in young women? Evidence from a population cohort in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 66(4), 443–451. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000198

- Hoffmann, J. P. (2006). Extracurricular activities, athletic participation, and adolescent alcohol use: Gender-differentiated and school-contextual effects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(3), 275–290.10.1177/002214650604700306

- Jernigan, D., Noel, J., Landon, J., Thornton, N., & Lobstein, T. (2017). Alcohol marketing and youth alcohol consumption: A systematic review of longitudinal studies published since 2008. Addiction, 112(S1), 7–20.10.1111/add.13591

- Kamndaya, M., Thomas, L., Vearey, J., Sartorius, B., & Kazembe, L. (2014). Material deprivation affects high sexual risk behavior among young people in urban slums, South Africa. Journal of Urban Health, 91(3), 581–591.10.1007/s11524-013-9856-1

- Kinsman, J., Norris, S. A., Kahn, K., Twine, R., Riggle, K., Edin, K., … Micklesfield, L. K. (2015). A model for promoting physical activity among rural South African adolescent girls. Global Health Action, 8.

- Kubayi, N., Toriola, A., & Monyeki, M. (2013). Barriers to school sport participation: A survey among secondary school students in Pretoria, South Africa. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 19(2), 336–344.

- Kwan, M., Bobko, S., Faulkner, G., Donnelly, P., & Cairney, J. (2014). Sport participation and alcohol and illicit drug use in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Addictive Behaviors, 39(3), 497–506.10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.006

- Laure, P., Lecerf, T., Friser, A., & Binsinger, C. (2004). Drugs, recreational drug use and attitudes towards doping of high school athletes. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 25(2), 133–138.

- Leclerc-Madlala, S. (2003). Transactional sex and the pursuit of modernity. Social Dynamics, 29(2), 213–233.10.1080/02533950308628681

- Liebenberg, J., du Toit-Prinsloo, L., Steenkamp, V., & Saayman, G. (2016). Fatalities involving illicit drug use in Pretoria, South Africa, for the period 2003–2012. South African Medical Journal, 106(10), 1051–1055.10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i10.11105

- Lisha, N. E., & Sussman, S. (2010). Relationship of high school and college sports participation with alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use: A review. Addictive Behaviors, 35(5), 399–407.10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.032

- Mahoney, J. L. (2000). School extracurricular activity participation as a moderator in the development of antisocial patterns. Child Development, 71(2), 502–516.10.1111/cdev.2000.71.issue-2

- Mahoney, J. L., & Stattin, H. (2000). Leisure activities and adolescent antisocial behavior: The role of structure and social context. Journal of Adolescence, 23(2), 113–127.10.1006/jado.2000.0302

- Marsh, H., & Kleitman, S. (2002). Extracurricular school activities: The good, the bad, and the nonlinear. Harvard Educational Review, 72(4), 464–515.10.17763/haer.72.4.051388703v7v7736

- Merkel, D. L. (2013). Youth sport: Positive and negative impact on young athletes. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 4, 151–160.10.2147/OAJSM

- Mhlongo, S., Dietrich, J., Otwombe, K. N., Robertson, G., Coates, T. J., & Gray, G. (2013). Factors associated with not testing for HIV and consistent condom use among men in Soweto, South Africa. PLoS ONE, 8(5), e62637.10.1371/journal.pone.0062637

- Mokabane, M., Mashao, M. M., Van Staden, M., Potgieter, M., & Potgieter, A. (2014). Low levels of physical activity in female adolescents cause overweight and obesity: Are our schools failing our children? South African Medical Journal, 104(10), 665–667.10.7196/SAMJ.8577

- National Youth Development Agency. (2015). National Youth Policy 2015 – 2020. April, 2015. Pretoria: NYDA.

- Nichols, S. L., Lowe, A., Zhang, X., Garvie, P. A., Thornton, S., Goldberger, B. A., … Sleasman, J. W. (2014). Concordance between self-reported substance use and toxicology among HIV-infected and uninfected at risk youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 134, 376–382.10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.11.010

- Parrinello, C. M., Isasi, C. R., Xue, X., Bandiera, F. C., Cai, J., Lee, D. J., … Kaplan, R. C. (2015). Risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence among US-born and non-US-born Hispanics/Latinos: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. American Journal of Public Health, 105(6), 1230–1236.10.2105/AJPH.2014.302155

- Parry, C. D. (2010). Alcohol policy in South Africa: A review of policy development processes between 1994 and 2009. Addiction, 105(8), 1340–1345.10.1111/add.2010.105.issue-8

- Peretti-Watel, P., Guagliardo, V., Verger, P., Pruvost, J., Mignon, P., & Obadia, Y. (2003). Sporting activity and drug use: Alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use among elite student athletes. Addiction, 98(9), 1249–1256.10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00490.x

- Pope, H. G., Jr., Wood, R. I., Rogol, A., Nyberg, F., Bowers, L., & Bhasin, S. (2013). Adverse health consequences of performance-enhancing drugs: An Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine reviews, 35(3), 341–375.

- Rambaree, K., Mousavi, F., & Ahmadi, F. (2017). Sports participation and drug use among young people in Mauritius. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 5, 1–10.10.1080/02673843.2017.1325756

- Reddy, S., James, S., Sewpaul, R., Koopman, F., Funani, N., Sifunda, S., … Omardien, R. (2010). Umthente uhlaba usamila-the 2nd South African national youth risk behaviour survey 2008. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council.

- Republic of South Africa. (1992). Drugs and Drug Trafficking Act No. 140 of 1992.

- Riley, E. D., Evans, J. L., Hahn, J. A., Briceno, A., Davidson, P. J., Lum, P. J., & Page, K. (2016). A longitudinal study of multiple drug use and overdose among young people who inject drugs. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), 915–917.10.2105/AJPH.2016.303084

- Schumacher Dimech, A. S., & Seiler, R. (2011). Extra-curricular sport participation: A potential buffer against social anxiety symptoms in primary school children. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(4), 347–354.10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.03.007

- Shannon, C. S. (2006). Parents’ messages about the role of extracurricular and unstructured leisure activities: Adolescents’ perceptions. Journal of Leisure Research, 38(3), 398.

- Sønderlund, A. L., O’Brien, K., Kremer, P., Rowland, B., De Groot, F., Staiger, P., … Miller, P. G. (2014). The association between sports participation, alcohol use and aggression and violence: A systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(1), 2–7.10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.011

- Weybright, E. H., Caldwell, L. L., Wegner, L., Smith, E., & Jacobs, J. (2016). The state of methamphetamine (‘tik’) use among youth in the Western Cape, South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 106(11), 1125–1128.10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i11.10814

- Zarrett, N., & Eccles, J. (2009). The role of family and community in extracurricular activity participation. In AERA Monograph series: promising practices for family and community involvement during high school 4: 27–51.

- Zuma, K., Shisana, O., Rehle, T. M., Simbayi, L. C., Jooste, S., Zungu, N., … Moyo, S. (2016). New insights into HIV epidemic in South Africa: Key findings from the National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. African Journal of AIDS Research, 15(1), 67–75.10.2989/16085906.2016.1153491