ABSTRACT

The Shujaaz media seek to improve the lives of Kenyan youth by norming and stimulating positive health behaviours, and incentivizing income generation activities. This study evaluates the impact of Shujaaz using data collected over a 2-year period from a cohort of 700 youth aged 15–24 years. Multivariate correlated random-effects regression models were used to estimate the impact of exposure to analogue (comic and radio) and digital Shujaaz media (social media and SMS) on attitudes, norms and behaviours around family planning and income generation. Shujaaz analogue media were associated with intermediate outcomes; digital media were associated with a 18.1 percentage point increase in ever using condoms and a 19.0 percentage point increase in recommending the use of condoms to friends and partners. Additionally, both analogue and digital media were associated with improved income-generating outcomes. Importantly, exposure to digital media was associated with a KSH 2,096 (US$20.9) increase in monthly income.

Background

Youth are critical for East African development, especially in light of the fast-approaching demographic window (Bloom, Kuhn, & Prettner, Citation2017; Gichuhi & Nasiyo, Citation2016; Kinaru-Mbae & Chatterjee, Citation2017). In Kenya, with almost 39% percent of the reproductive age population being 24 years old or younger (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, & ICF Macro, Citation2015), youth need opportunities to build human capital through developing marketable skills that enable them to generate income, and through controlling their fertility (AFIDEP, Citation2017; Facilitating Fertility Decline to Maximise on the Window of Opportunity, Citation2015). The present study examines how the Shujaaz multimedia platform aids Kenyan youth in achieving those goals.

Shujaaz as an omni-channel behaviour change strategy

Shujaaz is a public-interest media platform established in 2010 in Kenya. The overall focus of the Shujaaz strategy is to serve as a platform for young people to form a community, where they can discuss pressing issues, especially sensitive or taboo topics, such as money, sex, relationships, and contraception. Shujaaz uses an integrated omni-channel design that includes a free-of-charge nationally distributed comic (705,000 copies a month), a weekly syndicated radio show, and digital media (Facebook, SMS, Twitter, WhatsApp) to tell stories of fictional characters and real people representative of youth from different parts of the country as they encounter and resolve challenging life and health issues. Improving sexual and reproductive health outcomes and providing income-generation skills to youth in Kenya are at the centre of the Shujaaz strategy. At a glance, these two goals might seem independent, yet youth with greater level of financial realization have demonstrated higher intentions to use family planning (FP) methods as well (Nunes Hildebrand & Rodriguez Veloso, Citation2012).

The transtheoretical model of health behaviour change

Based on the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of health behaviour, the Shujaaz strategy recognizes that behaviour change is a process by stages, rather than a single event (Prochaska & DiClemente, Citation1982). The TTM model posits that change unfolds over time, progressing through a series of stages, including: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation and action. The Shujaaz strategy targets individuals situated at each of these stages of change, offering a mix of information and practical tools to help them achieve sexual and reproductive health and to improve income-generation skills.

During the pre-contemplation stage, it is hypothesized that individuals do not intend to take action in the near future, either because they are uninformed, under-informed, or misinformed about the pros and cons of specific behaviours (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, Citation2008). For those situated at this stage, Shujaaz exposes participants to stories highlighting the relevance of proper planning on health-related issues in order to achieve their income and development goals; this is the stage of ‘norming’ contraception use as an element of ‘smart planning’. During the contemplation stage, it is hypothesized that youth intend to change their behaviour but get stuck evaluating the pros and cons of their actions. At this stage, Shujaaz comic and radio stories dispel myths and misconceptions, while digital media conversations enable youth to discuss specific information about available contraceptive methods and available financial options to engage in financial transactions. In the preparation stage, individuals are ready to take action and are already willing to hold conversations with health providers, peers, parents, counsellors or other actors who could help them achieve the change (Glanz et al., Citation2008). Such conversations can happen on the Shujaaz social media platforms, on other platforms, or offline. Finally, individuals at the action stage are already making specific modifications towards the desired behaviour change, including contraceptive use and post-action behaviours such as recommending the use of modern contraceptive methods.

Analogue versus digital media channels

Different media channels are postulated to play distinct roles in guiding youth through the stages of change, with analogue and digital media characterized by distinct strengths. On the one hand, most analogue media (especially print) allow only uni-directional communication, in which the media professional presents media consumers with one message at a time. The ‘one-professional-voice’ is often viewed as more trustworthy than the multiple voices of digital media, while the consistency of the ‘voice’ also contributes to establishing a sense of belonging with analogue-media professionals (Deliso, Citation2006). In contrast, digital media enables multi-directional communication and expanded conversations, in which media consumers also serve as media producers by providing feedback on stories; sharing, modifying and adapting messages; and conducting conversations among peers (Stephen & Galak, Citation2010).

In market studies, empirical evidence reveals that media strategies relying on analogue channels have stronger impacts on brand awareness and trust, while strategies delivered through digital channels are more likely to have positive impacts on brand image (Bruhn, Schoenmueller, & Schäfer, Citation2012; Stephen & Galak, Citation2010). In this case, the Shujaaz strategy is designed so that stories appear first in the nationally distributed print comic to promote awareness and trust and are then expanded and reflected upon using the other media channels: the weekly radio show, monthly events, and a range of digital platforms. Because of the wider distribution of and access to analogue media in Kenya (and the lesser availability of digital and social media), we hypothesize that:

H1: Awareness of Shujaaz will be built primarily by initial exposure to Shujaaz interventions through analogue media, followed by exposure to digital media.

While it is anticipated that the combination of analogue and digital media unlocks the greatest benefits for the audience in terms of attitudinal, normative or behavioural outcomes (Deliso, Citation2006; Freeman, Potente, Rock, & McIver, Citation2015), currently however, the evidence base for such an approach is lacking, and there is still the need for rigorous explorations of the impact of a combination of analogue and digital media in a single Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) strategy. To date, most reported interventions have focused on using and assessing the impact of only one type of media – either analogue or digital – but not both in one coherent strategy (Hamm et al., 2014; Moorhead et al., Citation2013; Adewuyi & Adefemi, Citation2016; Freeman et al., Citation2015). By examining the Shujaaz media experience, this paper aims to fill the evidence gap on the effectiveness of a joint analogue/digital media platform by examining how Shujaaz users progress from first exposure to analogue media, followed by deeper engagement with Shujaaz digital platforms, and ultimately to changes in normative and behavioural outcomes. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2: Exposure to both analogue and digital media will be positively associated with normative and behavioural outcomes throughout the stages of change.

H3: The longitudinal effects of exposure to Shujaaz media on intermediate and final outcomes will vary significantly by channel of exposure (analogue vs. digital).

Finally, economic models suggest that labour market conditions can play a role in influencing marriage, childbearing, and the use of contraception. Considering that childbearing is traditionally more intensive in women’s time, the opportunity cost of having children is higher for women with greater income earning opportunities, leading to postponements in marriage and childbearing (Jensen, Citation2012). On the other hand, for both genders, when youth struggle to make a living, they are less able to prioritize the avoidance of pregnancy over immediate financial needs (Jennings et al., Citation2017). While Shujaaz targets the improvement of sexual and reproductive health among youth directly, it can also affect these outcomes indirectly through the promotion of income-generating skills and the subsequent increase in income. Therefore, our final hypothesis can be defined as:

H4: Shujaaz operates to improve family planning outcomes by increasing income.

Methods

Sample design

This study was originally intended as a nationally-representative cross-sectional survey that then became the baseline sample for a panel study. Data for the panel were collected through face-to-face interviews. The target random sample of youth was achieved using a multi-stage sampling procedure. Districts in the country were clustered into urban and rural strata and then selected within each stratum using a probability proportional to population size (PPPS) approach. To select households within clusters, interviewers established a minimum of four landmarks in each PSU and then randomly (using a Kish Grid) selected two landmarks as the starting points of the random walk. A Kish Grid was used to randomly select among eligible household members (adults, 15–24 years old). Only one respondent was selected in each household. If a desired respondent was not at home, an interviewer made up to three call-backs before a replacement household was selected.

For the second round of the interviews in January-February 2017, all 2,011 respondents from the 2016 survey were contacted by phone to confirm their location and availability. The respondents immediately available were re-interviewed within 1–2 weeks of the call, depending on their location. The respondents who moved but disclosed their new location and confirmed availability for the survey were also interviewed within 1–2 weeks of the call. Respondents who moved and changed their phone number required additional effort to track. The team contacted their families and neighbours by secondary contact phone or in person to find the new address and phone number for the respondents and tried to locate them, using updated contact information. In total, 700 participants completed the second round of interviews that formed the panel. No differences in area of residence, education, age, marital status, and access to internet were found between those who completed the second round of interviews and those who did not. However, in regression models that estimated the likelihood of being in the panel sample, males were more likely to participate in the second round of the survey (by 7% points). Similarly, those participating in the second round of the survey were more likely (by 6% points) to report no independent income.

Interviewers

Interviewers for this study were selected from the age group close to that of the Shujaaz audience, i.e. mostly younger than 25 years of age with the exception of the supervisory staff. Interviewers were recruited from all regions in Kenya and were fluent in several local dialects. Training of interviewers was done centrally in Nairobi and took three days for each data collection year plus an additional day for practice. Training was conducted in English as all interviewers had post-secondary education and were fluent in English; however, each received a translated KiSwahili questionnaire for guidance, and each had opportunities to practice interviewing in local dialects.

Questionnaire

In the survey, interviewers collected information from respondents on basic socio-demographic characteristics, general media use (e.g., radio, TV, newspapers and other printed media, internet and social media), family planning attitudes and behaviours, attitudes towards agriculture as an income-generating activity, and money and finance. Questions were designed to measure the norms, attitudes conversations, knowledge and other components within the Transtheoretical Model of Change, following global practices in media audience and behaviour outcomes assessment (Abreu-Lopez, Gersen, & Mirzoyants-McKnight, Citation2016; Bicchieri, Citation2014; Kang, Citation2010; Morhart, Malar, Guevremont, Girardin,F., & Grohmann, Citation2015; Speizer, Calhoun, & Guilkey, Citation2018; World Health Organization and Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2011).

Prior to the study launch, the questionnaire went through a round of internal and external reviews. The internal review was done by the Shujaaz Production and Social Media teams; the external interview was done by the Research Directors of Research Plus Africa, the company responsible for the data collection for this study. Small adaptations were made to the questionnaire based on the review process to ensure that the questions were sensitive to the cultural context of youth in Kenya and were clear to all respondents regardless of their age and educational attainment.

Ethical considerations

Participation in the survey was inclusive of respondents of both genders, socio-economic strata and ethnic backgrounds within the target age range of 15 to 24 years. Respondent participation was voluntary; each participant provided oral consent prior to the interview, and the consent was recorded in the computer assisted telephone interviewing system. For respondents aged 15–17 years old, interviewers obtained written guardian consent in line with the Child Protection Act of Kenya, in addition to the assent of the young person him/herself. All participants had the right to withdraw from the interview at any point. All data were kept confidential; individual questionnaires were identified by a numeric code only. Respondents’ names and contact information were secured in a separate dataset.

On behalf of Well Told Story, Research Plus Africa, the subcontractor in this study, obtained all required study permits from the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), which is the Kenyan equivalent to the human subject research approval by an Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Sexual and reproductive health outcomes

Eight different indicators were used to assess the process of adopting family planning, each one fitting within one of the stages of change (). At the pre-contemplation/contemplation stage, three indicators were used. First, family planning importance was assessed from two questions, including ‘How important is managing when you have children for you and for your future plans?’ defined as a binary variable, and agreement with the statement that ‘“smart hustlers” protect themselves from unwanted pregnancies,’ also defined as a binary variable. Family planning knowledge was defined as the number of contraceptive methods a respondent could spontaneously list as methods to prevent pregnancy. At the preparation stage, ‘conducting family planning conversations’ was defined as a set of binary variables informing any conversations with peers and any conversations with adults (including health providers and shopkeepers) about the use of contraceptives. At the action stage, three indicators were used. Ever use of condoms and ever use of modern contraception were defined as binary variables describing prevalence of ever use of the methods. In addition, recommending a condoms was also included in the analysis and assessed based on the question ‘Have you ever told your friends or partners they should use a condom?’

Table 1. The FP and Money Journeys by Stages of Change.

Income-generating skills

Similarly, multiple indicators were used to measure progress towards the generation of skills to increase income, largely focused on the ability of mobile money to facilitate savings, borrowing and purchasing. Corresponding to the pre-contemplation/contemplation stage, respondents were asked about the number of types of financial activities with which they were familiar, including such activities as budgeting, saving, borrowing, lending and investing. At the preparation stage, respondents were asked about conversations they may have had regarding income-generating activities or the use of mobile money (i.e., digital financial services) for multiple purposes. At the action stage, numerous indicators were used, including whether or not a person had ever used mobile money; whether or not a person had ever engaged in different types of financial activities; whether or not anyone had adopted mobile money as a consequence of conversing with the respondent; and monthly income (both as a categorical and as a continuous variable).

Exposure to Shujaaz

Study participants reported information about exposure to any Shujaaz media and the timing of first exposure to any analogue media (e.g., comic and radio) and to any digital media (e.g., Facebook, SMS, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, WhatsApp). For the analysis, exposure was determined by the timing of exposure to digital and analogue media, defined as nominal variables, with possible categories being: ‘Never exposed,’ ‘exposed for the first time in the last year,’ and ‘exposed for the first time more than a year ago.’

Analytical methods

Univariate statistics were calculated to describe the sample in 2016 and 2017. Bivariate statistics were calculated for associations between exposure to Shujaaz media and each of the principal outcomes. In addition, multivariate linear and logit regression were utilized with each sexual and reproductive health and money management indicator regressed on the variables for exposure to Shujaaz analogue and digital media and a set of socio-demographic control variables. Exposure to Shujaaz was self-reported. As such, it was non-randomly distributed, and therefore the estimation strategy attempted to control for both observable characteristics of respondents and unobservable innate differences. Control variables included: age (continuous), gender, relationship status (single no partner, single with partner, married or living with someone), and education level (none/some primary, primary, secondary, post-secondary). A separate set of regressions included monthly income in place of self-assessed financial status.

Because of the panel nature of the data (i.e., repeated observations for the same individuals) and the need to control for both observable and unobservable differences between those who self-reported exposure to Shujaaz and those who did not, correlated random effects regression models were used to estimate the impact of exposure to analogue and digital Shujaaz media. Repeated observations for individuals introduces serial correlation for each individual attributable to the time invariant unobservables (Wooldridge, Citation2013). While fixed-effects models are often used to address time invariant unobserved heterogeneity in panel data models, the correlated random-effects model relaxes the assumption of zero correlation between the individual-level time-invariant unobservable and the individual-level explanatory variables. Estimation involves decomposing the time-invariant unobservable into a fixed unobservable within individuals and a set of means of time-varying observable variables. Using this approach, we are able to estimate the effects of individual-level variables unbiased by correlation with the unobservable term at the individual-level, estimate random effects coefficients for the time invariant variables (e.g., gender), and generate an augmented Hausman specification test of the equivalence of fixed and random effects estimates (Allison, Citation2009; Schunck, 2013; Wooldridge, 2010). In nearly all causes, the robust version of the Hausman test strongly rejected the nulll of exogeneity of exposure, indicating that the use of the correlated random effects model was justified. For the income estimations in which the outcome involved left censoring at zero, we used the same strategy and estimated a correlated random effects tobit model.

Results

Descriptive results

Descriptive statistics of the sample at baseline and endline () largely reflect the natural maturation of the sample as they aged. In the 2016 wave, the average age was 18.4 years, increasing to 19.9 in the 2017 wave; more than half the sample was older than 19 years by 2017. The highest level of education attained varied across the sample, with the 59% having primary and 22% having secondary education respectively in 2016. By 2017, over a third of the sample had a secondary level of education. The percentage of the sample reporting that they were single, and dating increased from 34.1% to 46.6% from 2016 to 2017, while sexual activity increased from 57.3% to 62.1%. Mean income increased from KSH 2,399 in 2016 to KSH 3,934 in 2017. Finally, related to exposure to the intervention, the percentage of the sample who had ever heard of Shujaaz increased from 61.6% in 2016 to 89.1% in 2017.

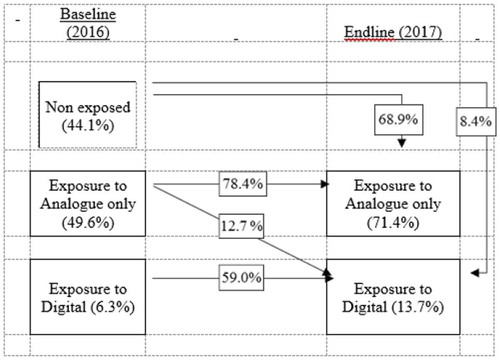

H1: Awareness of Shujaaz will be built primarily by initial exposure to Shujaaz interventions through analogue media, followed by exposure to digital media.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics at baseline and endline.

From , it is clear that the Shujaaz comic serves as the key portal by which youth become familiar with Shujaaz, thereby supporting H1. In 2016, youth were more than eight times as likely to be exposed to analogue alone as they were to be exposed to analogue plus digital (49.6% versus 6.3%), while 44% of the sample had not been exposed to any Shujaaz media. By 2017, 68.9% of the unexposed sample had transitioned to being exposed to analogue, bringing to 71.4% the percentage who had been exposed to Shujaaz by analogue media alone. An additional 8.4% had transitioned to being exposed to analogue plus digital. Among those exposed to analogue alone in 2016, 12.7% transitioned to being exposed to digital as well by 2017. Almost no one was exposed to digital alone.

Bivariate and multivariate results

H2: Exposure to both digital and analogue media will be positively associated with normative and behavioural outcomes throughout the stages of change.

H3: The longitudinal effects of exposure to Shujaaz media on intermediate and final outcomes will vary significantly by channel of exposure (analogue vs. digital).

In support of H2 and H3, bivariate modelling indicated that longer exposure (i.e., more than a year prior to the survey) to any Shujaaz digital media channel was associated with better sexual and reproductive health and income-generating outcomes in 12 out of 19 measured outcomes (). For example, relative to those not exposed to Shujaaz digital media, those exposed to the Shujaaz digital platform for more than one year prior to the survey were 23.9 percentage points more likely to declare having had any conversation related to contraception (82.2% versus 58.3%), 22.8 percentage points more likely to report ever use of a condom (73.3% versus 50.5%), and 25.9 percentage points more likely to ever use modern contraception (80.0% versus 54.1%). For analogue media, longer exposure to Shujaaz was associated with better SRH and income-generating outcomes for 9 out of 17 indicators, although the magnitude of effects tended to be smaller than for digital media.

Table 3. Bivariate analysis of timing of exposure to analogue and digital media, year 2017.

The multivariate regression modelling (), further supported hypothesis H2 that exposure to both digital and analogue media are positively associated with normative and behavioural outcomes related to contraception and income generation skills. With a respect to family planning, exposure to analogue media tended to affect the contemplative variables but not variables further along the Transtheoretical Model. For example, exposure to analogue media was associated with a 12.4 percentage point increase in agreement with the statement that smart hustlers use family planning.’ Digital media, however, tended to influence actions further along the model, such as a 18.0 percentage point increase in ever use of a condom and a 19.0 percentage point increase in recommending a condoms.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis.

For the models examining the steps to developing income generating skills, both analogue and digital media were associated with outcomes at different stages of the Transtheoretical Model. For example, exposure to analogue media was associated with discussions with adults about mobile money (preparation) and whether or not a respondent had ever engaged in financial transactions (action). Similarly, exposure to digital media was associated with an increase in income —both as a categorical variable and as a continuous variable (action).

H3: The longitudinal effects of exposure to Shujaaz media on intermediate and final outcomes will vary significantly by channel of exposure (analogue vs. digital).

For nearly all outcomes related to income generating skills, longer term exposure (> 1 year prior to the survey) had stronger effects than more recent exposure (< 1 year prior to the survey), with the exception being for awareness of the uses of money. For outcomes related to family planning, the effects of exposure to analogue media were statistically significant only for longer term exposure. In no cases did Shujaaz analogue exposure in the year preceding the survey influence outcomes. For digital media, effects were seen in the FP journey for both recent and longer term first exposure.

H4: Shujaaz operates to improve family planning outcomes by increasing income. The results from the multivariate modelling also support H4 that Shujaaz operates to improve family planning outcomes by increasing income. Notably, exposure to digital media at least one year prior to the survey was associated with a KSH 2,096 (US$20.9) increase in monthly income. In turn, being in the highest income tercile, as shown in the right-most panel of , was associated with a 8.9 percentage point increase in the ever use of modern contraceptives. In short, by influencing income, Shujaaz also works to improve family planning outcomes.

Discussion

This study has sought to evaluate a comprehensive youth-targeted, health and income skills behaviour change strategy involving a combination of a monthly comic, a syndicated radio program and multiple forms of digital media, including social media and SMS. The strategy is not the first to employ comics as a vehicle for social change and health promotion. Comics have been used to address issues related to nutrition and physical activity (Baranowski et al., Citation2002; Branscum, Sharma et al. 2013), sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS (Gillmore et al., Citation1997; Phrasayamongkhounh, Citation2015; Willis, Kachur et al. 2018), lymphatic filariasis (el-Setouhy & Rio, Citation2003), kidney transplants and cancer risk (Boynton, Citation2018), and even human trafficking (Benton & Daniela, Citation2012). Despite the wide appeal of comics, rigorous evaluations that document the impacts of comics on behaviour change have been relatively rare. The majority of evaluations have either been process evaluations (Branscum, Sharma et al. 2013) or descriptive in nature (Benton & Daniela, Citation2012; Boynton, Citation2018). In one of the few cases with rigorous study designs, Branscum et al (Branscum, Sharma et al. 2013) found that a theory-based nutrition and physical activity comic for children was associated with increased fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, and water and sugar-free beverage consumption.

The evidence that digital media, particularly social networking sites and SMS texting, can lead to behaviour change is still emerging. Authors (Hamm, Shulhan et al. 2014) have noted the potential for social network sites to provide a forum for adolescent peer communication but have also lamented the evidence base demonstrating effects on behaviour change. A few studies have used randomized control trials to examine the effects of social media on diet and exercise (DeBar et al., Citation2009; Lao, Citation2011; Rydell et al., Citation2005) and sexual health (Cox, Scharer, & Clark, Citation2009). However, while some of these were effective at increasing knowledge (Cox et al., Citation2009), only one was able to affect behaviour change.

Because few studies have examined the effectiveness of a combination of comic-based messaging with social networking, this study, therefore, represents an important contribution to this literature. Using a robust evaluation design that controls for non-random exposure to Shujaaz, this study demonstrates that a combined approach can work at multiple stages along the behaviour change framework. In the area of family planning, exposure to both analogue (e.g. the comic) and digital media affected key outcomes, including knowledge indicators (e.g. number of family planning methods known), valuation indicators (e.g. the importance of family planning), interpersonal communication about family planning, and ultimately use of family planning and recommending family planning to others. In a similar vein regarding the adoption of income-generating skills accumulation, exposure to digital and analogue media were associated with greater likelihood of discussions about money, and greater engagement in financial activities.

These results are consistent with previous evaluations of the Shujaaz media platform. Between 2010 and 2014, the Carolina Population Center conducted an evaluation of the Tupange Reproductive Health Program in Kenya, a multifaceted approach including the Shujaaz comic. Findings revealed that 15–19-year-old girls exposed to the Shujaaz comic were 1.8 times more likely to have never had sex and 2.5 times more likely not to have been pregnant than girls unexposed to Shujaaz (Speizer et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, results from Well Told Story’s 2015/2016 Cross-Sectional Surveys evidenced auspicious relationships between exposure to Shujaaz media and assorted contraception outcomes, as well as a negative relationship between exposure to Shujaaz and perceptions of smoking as being cool (Beaudoin, Citation2016). In addition, and related to income generation activities, survey participants reporting ever use of one or two Shujaaz platforms had higher levels of hustler attitudes, aided money activity recall, and money activity behavior. Ever users of two Shujaaz platforms exhibited higher levels of perceived current money situation (Beaudoin, Citation2016).

While this work used a rigorous panel design, future work might explore the possibility of using an experimental design, perhaps at the community level. For analogue media, different comics could be distributed in different parts of the country to test the effects of different messaging. Similarly, using geocoding, different messages and content could be shared on Facebook in certain areas of the country, again allowing for different combinations of digital and analogue media to be explored.

Strengths and Limitations

As main strength of our analytical approach, the strategy that was used to address self-determined exposure to Shujaaz was a multivariate control strategy with measurable control variables (e.g. age, education, gender, income, urban/rural) included in the multivariate models. In addition, correlated random-effects regression models were used that compared individuals to their earlier selves. These models looked at changes in variables as they related to changes in outcomes across time. Importantly, the random-effects approach tested and controlled for potential endogeneity of exposure to Shujaaz activities, thereby allowing for unbiased estimates of the effects of Shujaaz that simpler models would not achieve. The study faced several limitations. First, data collection was originally intended as a one-time cross-sectional survey and not a panel. For the cross-sectional survey, Research Plus Africa (the subcontractor in this study) randomly selected and interviewed N = 2,011 youth aged 15–24. While routine contact data were collected, participants were not originally advised of the panel-nature of the study, as that decision was made subsequent to the first round of data collection. Re-contact with participants, who represent a socially and geographically mobile population, was therefore not attempted until the second round of interviews (Shujaaz 360 Kenya, year-end report, Citation2017, full report).

As discussed in the section on the sample design, the panel study team made a plan for reaching as many youths as possible from the original sample. This involved (1) making phone calls to primary contacts to confirm the respondents’ location and schedule an interview, (2) making phone calls to secondary and tertiary phone contacts to inquire from families and neighbours the location of the respondent, and (3) making physical visits to the respondents’ original locations to find new locations and/or obtain new phone contacts. Successful contacts resulted in immediate interviews; the calls and visits started 2 weeks before the launch of the fieldwork and continued for the duration of the fieldwork (i.e. approximately six weeks). In spite of these attempts, only 700 youth in total could be re-contacted and re-interviewed.

A second key limitation of the study was the absence of an experimental design, which inhibits inferences about causal relationships. By choice or by nature, some people were exposed to Shujaaz materials while others were not, thereby increasing the risk of selection bias; the sample of people who were exposed to Shujaaz may have been different from the sample of people who were not in ways that may confound estimates of the impact of Shujaaz. These differences may be measurable – age, education, gender, socio-economic status – or unmeasurable – how people value the present versus the future, their willingness to take risks, and their access to social support systems. Not controlling for these differences can lead to over-estimates or under-estimates of program effects. This eventuality was addressed in part by the multivariate correlated random-effects models that relaxed the assumption of correlation between control variables, including exposure to Shujaaz, and time invariant unobservables. To the extent that the relationship between exposure to Shujaaz and outcomes is confounded by time varying unobservables, some bias in estimates of the effects of Shujaaz may remain.

A final limitation was that the first cross-sectional survey was not a true baseline. Shujaaz had already been in operation for several years. As a result, some of the effects of exposure to Shujaaz may have already been experienced prior to the evaluation. This could have resulted in a situation in which the full effects of Shujaaz might be underestimated.

Program implications

This study reviews Shujaaz media’s unique BCC approach to engaging diverse groups of youth, initially through analogue channels and subsequently through social platforms, where they join peer networks to benefit from giving and receiving social support, sharing ideas, and shifting norms. As the study results indicate, this sequential engagement, rooted in the Transtheoretical Model of Change, stimulates behaviour change in the areas of health and financial security/independence.

The Shujaaz experience can be used as a case study for BCC programs that aim to shift norms, attitudes and behaviours among youth through a purposeful integration of analogue and digital media, and through addressing topics related to sexual and reproductive health and financial security. This integrated approach reflects the holistic, multi-faceted way that a typical modern adolescent gathers information for decision-making. By closely identifying with youth and utilizing youth experiences as story narratives, Shujaaz creates an authentic, recognizable and audience-friendly community, which stimulates normative and behavioural change. The journey of a Shujaaz user detailed by this study can serve (1) as a blueprint for the design of BCC interventions, and (2) as a guide for linking evaluation activities to capture, correct and reinforce shifts in sexual and financial behaviours. Future data collection will help to determine if the impact can be replicated in other socio-cultural contexts, with other types of audiences, or in other developmental sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abreu-Lopez, C., Gersen, J., & Mirzoyants-McKnight, A. (2016). Shujaaz theory of change: Interdisciplinary action research at scale. African Centre for Applied Research (ACAR) (2014) Shujaaz establishment survey 2013.

- Adewuyi, E. O., & Adefemi, K. (2016). Behavior change communication using social media: A review. Int J Comm Health, 9, 109–116.

- African Institute for Development Policy, AFIDEP (May 5, 2017) Role of media critical in making demographic dividend a reality in Kenya. Retrieved from: https://www.afidep.org/role-media-critical-making-demographic-dividend-reality-kenya/

- Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models (Vol. 160). SAGE publications.

- Baranowski, T., Baranowski, J., Cullen, K. W., deMoor, C., Rittenberry, L., Hebert, D., & Jones, L. (2002). 5 a day achievement badge for African-American boy scouts: Pilot outcome results. Preventive Medicine, 34(3), 353–363.

- Beaudoin, E. C. (2016). Final report: Shujaaz media and outcome analysis. Unpublished manuscript.

- Benton, -B. A. P.-B., & Daniela. (2012). When the abyss looks back: Treatments of human trafficking in superhero comic books. Northeast popular culture association. Rochester, NY: S. Fredonia. St. John Fisher College.

- Bicchieri, C. (2014) Norms, conventions and the power of expectations. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/belab/1.

- Binagwaho, A., Lynch, C. A., Radovich, E., Cavallaro, F. L., Wong, K. L., Benova, L., … Waiswa, P. (2017). Pathways to increased coverage: An analysis of time trends in contraceptive need and use among adolescents and young women in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 130.

- Bloom, D. E., Kuhn, M., & Prettner, K. (2017). Africa’s prospects for enjoying a demographic dividend. Journal of Demographic Economics, 83(1), 63–76.

- Boynton, P. (2018). “Using Comics to Save Lives,” the Lancet, 390, 19–20.

- Branscum, P., Sharma, M., Wang, L. L., Wilson, B., & Rojas-Guyler, L. (2013a). A process evaluation of a social cognitive theory-based childhood obesity prevention intervention: The comics for health program. Health Promotion Practice, 14(2), 189–198.

- Branscum, P., Sharma, M., Wang, L. L., Wilson, B. R., & Rojas-Guyler, L. (2013b). A true challenge for any superhero: An evaluation of a comic book obesity prevention program. Family & Community Health, 36(1), 63–76.

- Brooks, & Sutton, M. Y. (2018). Developing a motion comic for HIV/STD prevention for young people ages 15-24, part 1: Listening to your target audience. Health Communication, 33(2), 212–221.

- Bruhn, M., Schoenmueller, V., & Schäfer, D. B. (2012). Are Social Media Replacing Traditional Media in Terms of Brand Equity Creation? Management Research Review, 35(9), 770–790.

- Cox, M. F., Scharer, K., & Clark, A. J. (2009). Development of a web-based program to improve communication about sex. Computers, Informatics, Nursing : CIN, 27(1), 18–25.

- DeBar, L. L., Dickerson, J., Clarke, G., Stevens, V. J., Ritenbaugh, C., & Aickin, M. (2009). Using a website to build community and enhance outcomes in a group, multi-component intervention promoting healthy diet and exercise in adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(5), 539–550.

- Deliso, M. (2006, October 02). “Traditional media more trustworthy than emerging. Ad age: Media news.” Retrieved from http://adage.com/article/media/traditional-media-trustworthy-emerging/112254

- el-Setouhy, M. A., & Rio, F. (2003). Stigma reduction and improved knowledge and attitudes towards filariasis using a comic book for children. Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology, 33(1), 55–65.

- “Facilitating Fertility Decline to Maximise on the Window of Opportunity.” (2015, June). NCPD and AFIDEP, policy brief no. 48. Retrieved from: https://www.afidep.org/?page_id=3521

- FHI 360/PROGRESS, & Kenya Ministry of Health. (2011). Adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health: Takingstock in Kenya. Retrieved from

- Freeman, B., Potente, S., Rock, V., & McIver, J. (2015). Social media campaigns that make a difference: What can public health learn from the corporate sector and other social change marketers. Public Health Researcher Practical, 25(2), e2521517.

- Gichuhi, W., & Nasiyo, A. M. (2016). The prospects of enhancing food security in Kenya through the demographic dividend. African Population Studies, 30(2).

- Gillmore, M. R., Morrison, D. M., Richey, C. A., Balassone, M. L., Gutierrez, L., & Farris, M. (1997). Effects of a skill-based intervention to encourage condom use among high risk heterosexually active adolescents. AIDS Education and Prevention : Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 9(1 Suppl), 22–43.

- Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. (2008). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hamm, M. P., Shulhan, J., Williams, G., Milne, A., Scott, S. D., & Hartling, L. (2014a). A systematic review of the use and effectiveness of social media in child health. BMC Pediatrics, 14, 138.

- Hamm, M. P., Shulhan, J., Williams, G., Milne, A., Scott, S. D., & Hartling, L. (2014b). A systematic review of the use and effectiveness of social media in child health. BMC Pediatrics, 14, 138.

- Jennings, L., Mathai, M., Linnemayr, S., Trujillo, A., Mak’anyengo, M., Montgomery, B. E., & Kerrigan, D. L. (2017). Economic context and HIV vulnerability in adolescents and young adults living in urban slums in Kenya: A qualitative analysis based on scarcity theory. AIDS and Behavior, 1–15.

- Jensen, R. (2012). Do labor market opportunities affect young women’s work and family decisions? Experimental evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(2), 753–792.

- Kang, M. (2010) Measuring social media credibility: A study on a measure of blog credibility. Retrieved from http://www.instituteforpr.org/wp-content/uploads/BlogCredibility_101210.pdf

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, & ICF Macro. (2015). Kenya demographic and health survey 2014.

- Kinaru-Mbae, J., & Chatterjee, R. (accessed on November 6, 2017) With Kenya’s youth, the future is here: Invest to reap demographic benefits. Retrieved from: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/siddharth-chatterjee/with-kenyas-youth-the-future-is-here_b_8013228.html.

- Lao, L. (2011). Evaluation of a social networking based SNAP-Ed nutrition curriculum on behavior change, PhD Thesis, University of Rhode Island.

- Moorhead, S. A., Hazlett, D. E., Harrison, L., Carroll, J. K., Irwin, A., & Hoving, C. (2013). A new dimension of health care: Systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(4), e85.

- Morhart, F., Malar, L., Guevremont, A., Girardin,F., & Grohmann, B. (2015). Brand authenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(2), 200–218.

- Nunes Hildebrand, D. F., & Rodriguez Veloso, A. (2012). Factors that influence the use of birth control by Brazilian adolescents. BBR-Brazilian business review(1).

- Phrasayamongkhounh, S. (2015). Assessing the engagemen of young people with the comic book ‘condoms: A decision for life’ as an edutainment apporach to HIV/AIDS prevention programme. Unitec Institute of Technology.

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 19(3), 276–288.

- Rydell, S. A., French, S. A., Fulkerson, J. A., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Gerlach, A. F., Story, M., & Christopherson, K. K. (2005). Use of a web-based component of a nutrition and physical activity behavioral intervention with girl scouts. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105(9), 1447–1450.

- Shujaaz 360 Kenya, year-end report (2017) #Shujaaz360: It’s all about the money. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/15acEqbjBc-jI50GCdBIaZm7wGpaXD1xZ/view.

- Shujaaz Measurement, E. A. L. F. (2015). Concept note: Qualitative study 1 for MEL framework. Kenya: Retrieved from Nairobi.

- Shujaaz Measurement, E. A. L. F. (2016). Cross-sectional survey of youth aged 15-24 in Kenya, December 2015-January 2016 (N=2,011), dataset. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved from.

- Shujaaz Measurement, E. A. L. F. (2017). Cross-sectional survey of youth aged 15-24 in Kenya, January-May 2017 (N=2,923), dataset. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved from.

- Speizer, I. S., Calhoun, L. M., & Guilkey, D. K. (2018). Reaching urban female adolescents at key points of sexual and reproductive health transitions: Evidence from a longitudinal study from Kenya. African journal of reproductive health, 22(1), 47-59.

- Stephen, A. T., & Galak, J. (2010). The complementary roles of traditional and social media publicity in driving marketing performance. Fontainebleau: INSEAD working paper collection.

- Willis, L. A. R., Kachur, T. J., Castellanos, P., Spikes, Z. J., Gaul, A. C., Gamayo, M., … Staatz, M. Hogben, S. Robinson, J. T.

- Wooldridge, J. T. (2013). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (5th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

- World Health Organization and Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Tobacco questions for surveys: A subset of key questions from the global adult tobacco survey (GATS) (2nd edition ed.). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/en_tfi_tqs.pdf