Abstract

A systematic review was conducted to investigate the literature on effectiveness of life skills programs. The aim of this review was to gain a comprehensive understanding on the effectiveness of life skills education globally, and to identify research gaps and priorities. Findings revealed differences in life skills education within developing countries and developed countries. In general, developed countries conduct more systematic life skills education programs promoting positive behavior, with research articulating outcomes on individual youth. In contrast, the majority of developing countries’ life skills programs lack systematic implementation, evaluation and monitoring. Programs are often conducted to yield short term results only. This review will be useful to administrators, policy makers, researchers and teachers to implement effective life skills programs. The findings can be used as inputs for developing sustainable life skills programs to ensure transfer of knowledge and skills.

Introduction

Adolescents who face personal, cognitive and social skills deficits are prone to drug use, bullying, violence, STIs, HIV, AIDS, malnutrition and other socio- economic and environmental challenges. Specific emotional, cognitive, behavioural and resilience skills play a vital part in ensuring an adolescent’s personal and social success (Langford & Badeau, Citation2015; McWhirter, McWhirter, McWhirter, & McWhirter, Citation2007; WHO, Citation1993). Likewise, psychosocial skills allows individuals to recognize, interact, influence and relate to others in different environments. Children and adolescents with psychosocial skills have positive mental health and wellbeing (Savoji & Ganji, Citation2013; WHO, Citation1993). Additional skills, such as emotional, cognitive, behavioral and resilience development in adolescents will help them navigate their psychological push backs for high risk behaviour and negative mental wellbeing (WHO, Citation2016). Life skills has been identified as an essential resource for developing psychosocial, emotional, cognitive, behavioral and resilience skills to negotiate every day challenges and productive involvement in the community (Desai, Citation2010; Galagali, Citation2011). These skills are known to be key contributors to negotiating and mediating challenges that young people face in becoming productive citizens (Prajapati, Sharma, & Sharma, Citation2017; Savoji & Ganji, Citation2013; WHO, Citation1993).

There is a growing demand to educate adolescents with life skills to help them deal with their day to day life challenges and transition into adulthood with informed healthy choices. Demonstrating its effectiveness, significance and value, life skills has become a major part of many intervention programs around the globe, particularly those aimed at the prevention of alcohol abuse, drugs and smoking (Botvin & Kantor, Citation2000; Huang, Chien, Cheng, & Guo, Citation2012; Mandel, Bialous, & Glantz, Citation2006). Additionally, life skills programs have been implemented in the context of multiple programmatic settings such as sports, at-risk behaviour, and sexual and reproductive health programs (Jones & Lavallee, Citation2009).

Although life skills programs have proliferated around the world little is known about the efficacy and effectiveness of these programs on individual behaviour and attitude. The skills developed through life skills are micro behaviours and their acquisition is rarely assessed (UNICEF, Citation2012). Most research (Botvin & Kantor, Citation2000; Huang et al., Citation2012; Mandel et al., Citation2006) on life skills focuses on program effectiveness rather than the learners’ experiences both in and following their time with the program. Therefore, determining acquisition of knowledge, skill and attitude change as a result of life skills program is essential to identify how life skills programs are designed to ensure attainment of program content and knowledge. While there are a number of studies (Giannotta & Weichold, Citation2016; Weichold & Blumenthal, Citation2016; Weichold, Tomasik, Silbereisen, & Spaeth, Citation2016; Wenzel, Weichold, & Silbereisen, Citation2009) identifying the effectiveness of life skills programs, further research is required to identify what and how life skills effectiveness is determined. As such there is a need to review the literature systematically, in order to synthesize the available research on the effectiveness of life skills education with an eye toward advancing our understanding of what and how life skills effectiveness is determined and to identify research gaps and priorities for moving forward. Therefore, this paper examines the published literature on the effectiveness of life skills programs conducted with adolescents 10 to 19 years old.

What is life skills education?

The goal of life skills education is to equip individuals with appropriate knowledge on risk taking behaviours and develop skills such as communication, assertiveness, self-awareness, decision-making, problem solving, critical and creative thinking to protect them from abuse and exploitation (UNICEF, Citation2015; WHO, Citation1993). Life skills programs are conducted with a focus on specific life skills, depending on the setting. For example, in countries like the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Greece, and Mexico special life skills education programs are designed to promote positive refusal skills and effective decision-making around smoking, alcohol, drug abuse, HIV, AIDS, contraception, perception about sexual activities and condom use (Botvin, Griffin, Diaz, & Ifill-Williams, Citation2001; Campbell-Heider, Tuttle, & Knapp, Citation2009; Givaudan, Leenen, Van De Vijver, Poortinga, & Pick, Citation2008; MacKillop, Ryabchenko, & Lisman, Citation2006; Martin, Nelson, & Lynch, Citation2013; Menrath et al., Citation2012).

In contrast, developing countries such as India, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Bangladesh, Thailand, Mynamar and Nepal incorporate life skills concepts into their curriculum at different grade levels (WHO, Citation2001). These life skills programs are designed and conducted in sequential order by component, with an emphasis on everyday skills such as communication, which is a basic level skill. Application of skills related to health and social issues such as gender roles are considered as intermediate level skills. Further, the advanced level application of life skills such as those in relation to risk behaviours (e.g. drugs and smoking) are taught last (WHO, Citation1993). Likewise, countries in the Asia and Pacific Regions, for instance, combine life skills into comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) programs to reduce risk behaviour and improve the health and well-being of young people (UNFPA, Citation2015).

Consequently, life skills takes on a contemporary approach to teach health and other social issues (WHO, Citation2001), which are delivered in multiple ways. For instance, Life Skills Education (LSE) as proposed by the World Health organization, is an educational intervention that is designed to address life skills focus areas with needs- and outcome-based participatory learning (UNICEF, Citation2003, 2015). The main goal of LSE is to develop positive and adaptive behaviour by supporting individuals to practice and cultivate psychosocial skills that can reduce risk and capitalize on constructive behaviour (Munsi, Guha, Bengal, & Bengal, Citation2014; Prajina, Citation2014). The life skills education approach contours on how young people learn from their own experiences and from the people around them (WHO, Citation1993). Drawing on Bandura’s social learning theory, skills are learnt through interaction, processing and structuring of experiences (Aparna & Raakhee, Citation2011; Prajapati et al., Citation2017). Therefore, life skills is designed to be taught through experiential learning such as role play, modelling and practice.

Life Skills Based Education (LSBE) is an approach used to address specific content to achieve a certain goal (UNICEF, Citation2003). For example, life skills-based HIV/AIDS education aims to impart knowledge about HIV and AIDS through holistic learning experiences aimed at developing not only knowledge and attitudes but also the skills needed for an individual to make informed decisions for positive behaviour change (UNICEF, Citation2012). LSBE is interchangeably used with skill-based health education and is often used to address a wide range of topics significant to children, adolescents, youth and adult development.

The main difference between LSE and LSBE is the approach. In LSBE, teaching methods and activities are used to help learners develop the necessary psychosocial skills to acquire knowledge and develop the right attitude for positive behaviour change. Additionally, LSBE enhances the value and importance of traditional subjects such as literacy and numeracy along with social issues such as HIV/AIDS, gender, peace and environment, equality and sustainable development. LSBE focuses on the development of critical thinking, analytical thinking and negotiation skills in managing information, knowledge and experiences in various areas of life (UNESCO, Citation2008).

One of the more recent approaches to teaching life skills is through infusion. Infusion integrates preventive objectives and activities into academic activities in such a way that the content and skills that the learners acquire are spread across different teachers (Smith et al., Citation2004). The fundamental objective of the infusion approach is to teach learners how to translate information and concepts they learn in school into their daily life. Thus, life skills contents are infused into the basic subjects of the school curriculum with an innovative delivery method (Smith et al., Citation2004). Unlike the LSE where content is delivered in number of sessions, the life skills infusion approach does not limit the content into number of sessions but rather assures that all components are distributed across subjects through diversification in delivery methods. Infusion has been shown to be effective in reducing smoking, binge drinking, and use of marijuana (Botvin & Kantor, Citation2000; Smith et al., Citation2004; Vicary et al., Citation2004) and as a result 145 countries have integrated life skills into their primary and secondary curricula (UNICEF, Citation2012). However, for an infusion approach to be effective it needs to be designed well and delivered age appropriately (Konkel, Citation2016). Further, the infusion approach to teaching life skills is limited to the school setting as findings cannot yet be generalized to other settings (Bwayo, Citation2014; Konkel, Citation2016).

Examples of life skills programs

Life skills programs have been implemented via multiple focal areas such as sports settings, risky behaviours, and sexual and reproductive health (Jones & Lavallee, Citation2009). Nevertheless, all life skills programs aim to serve the same purpose, which is to help individuals overcome challenges and grow into healthy human beings. For example, the Positive Adolescents Life Skills (PALS) program is based on a cognitive-behaviour skill building intervention that sets out to change behavior by improving social skills (Tuttle, Campbell-Heider, & David, Citation2006). The program consists of 25 cognitive behavioral skill building sessions that are divided into five units comprised of basic communication, network skills, cognitive skills, problem solving skills and assertiveness (Campbell-Heider et al., Citation2009). The PALS program has been found to be effective with teens in their everyday lives (Campbell-Heider et al., Citation2009; Tuttle et al., Citation2006).

IPSY (Information + Psychosocial Competence = Protection) is a universal school-based life skills program that aims to delay the onset and reduce consumption of alcohol and tobacco during adolescence (Weichold, Citation2014; Wenzel et al., Citation2009). IPSY is a combination of intra- and interpersonal life skills, and substance reduction skills such as resistance skills, school bonding, knowledge and prevention of substance abuse (Weichold, Citation2014). Further, IPSY is considered an effective intervention against the use of tobacco and drugs among adolescents (Giannotta & Weichold, Citation2016; Weichold & Blumenthal, Citation2016; Weichold et al., Citation2016; Wenzel et al., Citation2009).

Fit and Strong for Life, developed by Ahrens-Eipper et al. in 2002, is a well-established modular life skills program conducted for primary and secondary schools in Germany (Cina et al., Citation2011). Lions Quest, developed by Wilms and Wilms in 2004, aims to foster life skills and self-efficacy and include the prevention of substance abuse such as cigarettes, alcohol, and drug consumption as their primary objective (as cited in Menrath et al., Citation2012). Fit and Strong for Life covers topics such as communications skills, coping with stress and emotions, self-esteem, empathy, resistance skills, decision-making, critical thinking skills, and health education (Cina et al., Citation2011). This program is targeted to primary and secondary school children whereas Lions Quest is delivered to secondary school students with topics such as self-esteem, self-efficacy, coping with emotions, decision-making, and inter and intra relationships. Both programs have been found to be effective in reducing tobacco use but no effects have been found on the development of health-related behaviours, social competencies, self-efficacy or overall behavioural improvement (Cina et al., Citation2011; Eisen, Zellman, & Murray, Citation2003; Menrath et al., Citation2012).

Life Skills Training (LST), developed by Botvin, focuses on adolescent substance abuse behaviours. The main aim of the program is to provide alternatives to risky behaviours rather than just providing information about alcohol, drugs and smoking. Botvin’s Life Skills Training program is designed to teach adolescents the necessary skills needed to resist peer influences on the use of smoking, drinking and using drugs. Through skill building activities, adolescents develop self-esteem and self-confidence to effectively cope with stress and anxiety (Botvin, Dusenbury, Baker, James-Ortiz, & Kerner, Citation1990; Botvin & Griffin, Citation2004; Epstein, Griffin, & Botvin, Citation2000; Griffin & Botvin, Citation2014; Griffin, Botvin, Scheier, Epstein, & Doyle, Citation2002). Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) aims to reduce risky behaviour and improve health and wellbeing of young people (UNFPA, Citation2015). The contents of the CSE program include reproductive health and puberty with opportunities to develop positive attitudes, values and build life skills such as inter and intrapersonal communication, decision-making, and assertive skills (UNFPA, Citation2015; UNICEF, Citation2010).

Review methodology

In order to address the review purpose, the following steps were taken: (1) identify inclusion and exclusion criteria for article selection, (2) identify the relevant work (search strategy), (3) data extraction and quality appraisal of the selected studies, and (3) summary, synthesis and interpretation of the findings (Khan, Kunz, Kleijnen, & Antes, Citation2003; Ryan, Citation2010; Siddaway, Citation2014; Strech & Sofaer, Citation2012). For the purpose of the review, the target adolescent population was defined as 10–19 year olds.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In selecting studies suitable for the review, the following selection inclusion and exclusion criteria were considered. illustrates the criteria in detail.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategy

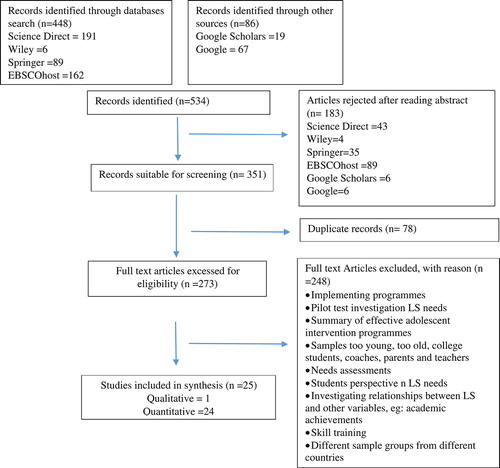

A search for published and unpublished literature on life skills was conducted on four databases. Databases that were included in the search were Science Direct, Wiley, Springer and EBSCOhost. Furthermore, articles were searched on Google Scholar and Google. All available articles up to 2016 were considered. However, filters were used for language (e.g.: English). For the search, key words such as life skills AND prevention AND adolescents or ‘life skills in high school AND prevention AND adolescents’ or ‘coping skills AND prevention AND adolescents’ or ‘life skills AND behavior AND adolescents’ or ‘social skills AND behavior AND adolescents’ or ‘adolescents AND community development’ were used. Search details of the databases are reported in . The search was conducted on 4000 articles on the Science Direct database, which resulted in 191 identifying with key terms. An examination of 120 articles on Wiley resulted in an identification of 6 articles. Among the 1520 articles searched on the Springer database, 89 articles were identified. Out of 1281 articles searched in EBSCOhost, 162 articles were found satisfactory. Additionally, Google Scholar and Google were also searched in case articles might have been missed from the other databases. Thus, having searched over 600 articles between Google Scholar and Google, 86 articles were identified to be screened.

Table 2. Applied search details.

All studies identified were further examined by a step-by-step screening process. depicts the flow chart of the different stages of the literature search adopted from the PRISMA flow diagram (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, Citation2009). The initial step was evaluating the relevance of the identified articles based on the titles and abstracts. A total of 534 articles were screened for relevance, out of which 183 abstracts were excluded based on the relevance to review objectives. Among the remaining 351 records, 78 records were duplicates and omitted from the review, leaving 273 articles eligible for full text screening. The second step consisted of retrieving the full text articles and screening them for eligibility in the review. Of these, 248 articles were excluded based on the inclusion criteria. Among the excluded articles, most were omitted due to: (a) different sample population, (b) report of pilot test or investigation of life skills needs, (c) implementation of evaluation of a life skills program, (d) establishing relationship between life skills and adolescent issues such as academic achievement, and (e) summary of adolescent intervention programs. Based on the inclusion criteria, 25 articles – one qualitative study and 24 quantitative studies – were selected for the data synthesis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Having identified the potential articles for the review, the next step was data extraction. According to Popay et al. (Citation2006), the type of data to be extracted should be based on the review questions. If the review is addressing a question about ‘effectiveness’ of a particular intervention, then relevant information to extract would include the sample population, the study design, where the study took place, the interventions and the outcomes.

Having abstracted data independently for each study, an assessment of the reviewed articles was carried out to determine the methodological quality of each article. To evaluate the quality of the selected studies, a checklist for assessing quality of qualitative studies (Kmet, Lee, & Cook, Citation2004) and the quality assessment tool for quantitative studies (National Collaborating Centre for Methods & Tools, Citation2010) were used. The review had to address: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals and drop outs. Based on these component ratings seven articles were rated strong, eight articles were found to be of moderate quality and nine articles were found to be weak. illustrates the data extraction and study quality of each article.

Table 3. Selected study details and quality assessment.

Results

The reviewed articles suggest that life skills education has been implemented in multiple settings such as sports, at-risk behaviors, and sexual and reproductive health programs (Jones & Lavallee, Citation2009). The main expected outcome from life skills education is to equip participants with appropriate knowledge and skills to protect them from abuse, exploitation and to help them refrain from risky and risk-taking behaviours (UNICEF, Citation2015). It is implicit that life skills have several common key components, which include behavioral, cognitive, psychosocial and interpersonal competencies that aid individuals to cope with challenges, and develop and succeed in various settings. However, several studies report deficiencies in the transfer of skills as little emphasis was placed on acquiring skills through various approaches such as modelling, imitation and reinforcement (Botvin, Citation1998; Botvin & Kantor, Citation2000; James, Reddy, Ruiter, McCauley, & van den Borne, Citation2006; Kazemi, Momeni, & Abolghasemi, Citation2014; Maryam, Davoud, Zahra, & Somayeh, Citation2011).

Looking at the outcome measures, it was observed that the selected articles focus on a number of adolescent-related issues such as alcohol, tobacco, drug use, HIV/AIDS, exposure to sex, decision-making, communication, assertiveness, aggression, self-efficacy, self-esteem, self-understanding, self-image, goal attainment and goal setting. The studies revealed that life skills tend to be effective in bringing about individual changes relevant to knowledge, skills and attitudes in risk areas as well as psychosocial skills (Botvin et al., Citation2001; Lillehoj, Trudeau, Spoth, & Wickrama, Citation2004; Menrath et al., Citation2012). Although these studies show promise, they were limited in their scope to a particular research design such as experimental, quasi-experimental or randomized control groups.

Subgroup analysis indicated that life skills education activities conducted around the world reflect the priorities and areas of concern of the respective countries. For example, the USA, Canada, UK, Germany and Greece have many well-planned, tailor-made life skills education programmes that aim to promote positive behaviours around smoking, alcohol, drug abuse, HIV, AIDS, contraception, perception about sexual activities and condom use through refusal skills, attitude change and personal goal setting (Botvin et al., Citation2001; Goudas, Dermitzaki, Leondari, & Danish, Citation2006; Goudas & Giannoudis, Citation2008; Holt, Tink, Mandigo, & Fox, Citation2008; Lillehoj et al., Citation2004; Menrath et al., Citation2012; O’Hearn & Gatz, Citation1999; Smith et al., Citation2004; Teyhan et al., Citation2016; Thompson, Auslander, & Alonzo, Citation2012; Tuttle et al., Citation2006; Vicary et al., Citation2004; Weichold & Blumenthal, Citation2016; Wenzel et al., Citation2009). These programs address cognitive, affective, and behavioral competencies to develop self-efficacy, for positive social and personal behavior.

Similarly, life skills education programs are popular in developing countries such as India, South Africa, Cambodia, Iran and Mexico. However, programs conducted in these countries often emphasize the development of communication skills, assertive skills, decision-making, building self-esteem, self-efficacy, reducing learning difficulties, decrease aggressive behavior, anger control, and changing attitudes towards engaging in sexual behavior (James et al., Citation2006; Jegannathan, Dahlblom, & Kullgren, Citation2014; Maryam et al., Citation2011; Naseri & Babakhani, Citation2014; Parvathy & Pillai, Citation2015; Pick, Givaudan, Sirkin, & Ortega, Citation2007; Vatankhah, Daryabari, Ghadami, & KhanjanShoeibi, Citation2014; Yadav & Iqbal, Citation2009). Studies are limited to reporting on short term results through experimental methods with small samples sizes without any follow-up to fully ascertain the effectiveness of the respective programs (Jegannathan et al., Citation2014; Maryam et al., Citation2011). These findings signal a need for further research to further explore the effectiveness of the programs.

Research gaps and research priorities

Taken together, the identified articles deliver encouraging prospects for improving life skills education programs as several gaps such as how to transfer life skills into everyday life and priorities for reducing risk behaviors were identified (Jegannathan et al., Citation2014). Qualitative studies on life skills education were limited; only one qualitative study met the inclusion criteria of effectiveness of life skills experiences focusing on young people’s learning experiences (Holt et al., Citation2008). Many of the identified studies were based on assessment of life skills components rather than understanding what knowledge, skills and attitudes adolescents require in order for positive behavior change to occur. Hence, future research should be directed toward investigating how life skills program knowledge is translated into behavior and attitude change (O’Hearn & Gatz, Citation1999; Parvathy & Pillai, Citation2015; Pierce, Gould, & Camiré, Citation2017).

Second, fewer studies have been conducted in developing country contexts in comparison to those carried out in developed countries (Givaudan, Van de Vijver, Poortinga, Leenen, & Pick, Citation2007; Maryam et al., Citation2011). Successful life skills programs such as the Botvin Life Skills Training Programme have implemented cognitive, affective and behavioral platforms for intervention with the goal of influencing individual learning with ongoing support from the community (Botvin & Griffin, Citation2004). These programs were highly structured with concise modules specifically prepared for addressing at-risk behaviors. In contrast, programs conducted in countries like India and Iran, such as the Life Skills Education Program, comprised a series of developmental sessions consisting of communication skills, assertiveness, anger management, decision-making, creative and critical thinking skills (Naseri & Babakhani, Citation2014; Parvathy & Pillai, Citation2015; Yadav & Iqbal, Citation2009). Many of these programs however, lacked rigorous planning, and were thus not implemented effectively (Holt et al., Citation2008; James et al., Citation2006; Jegannathan et al., Citation2014). For instance, researchers have suggested that life skills programs aimed at improving attitudes and knowledge on HIV/AIDS and condom use need to improve the time spent on the lessons, in addition to increasing the number of lessons carried out to address specific issues (James et al., Citation2006; Thompson et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, some content needs to be taught with more skill-based activities to ensure that skills are developed (James et al., Citation2006; Maryam et al., Citation2011; Thompson et al., Citation2012).

A variety of teaching methods need to be used to ensure participant involvement and internalization of information. These contents in the life skills education programs need to be delivered with an emphasis on development of skills rather than delivering specific knowledge about safe sex and protection against HIV/AIDS alone. For example, James et al. (Citation2006) stated that if the goal of life skills is to promote safer sex, then efficacy beliefs and skills related to condom use as well as proper communication skills on how to communicate with one’s partner on adopting safer sex should be included.

Studies reported that many life skills programs in developing countries focusing on promoting adaptive behaviors are structured as one-shot or short-term interventions rather than ongoing activities, and they lack emphasis on individual learning (Parvathy & Pillai, Citation2015; Teyhan et al., Citation2016; Tuttle et al., Citation2006). Scholars, however, have emphasized the need to implement sustainable life skills programs as a top priority (James et al., Citation2006; Jegannathan et al., Citation2014). Therefore, more attention is required in these contexts to develop programs that are ongoing and sustainable through systematic planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation in order to learn skills and attitude change (UNICEF, Citation2012).

While there is consensus that life skills education acts as a buffer for prevention of at-risk behaviors, the sustainability of effective life skills programs has been called into question (James et al., Citation2006; Lillehoj et al., Citation2004; Yadav & Iqbal, Citation2009). According to James et al. (Citation2006) this could be due to a lack of programmatic structure, which tends to be common in developing country settings. Kazemi et al. (Citation2014), Maryam et al. (Citation2011), and Teyhan et al. (Citation2016), suggest that program evaluation and follow up are equally important in sustainability. Therefore, systematic planning and implementation is critical for effective and sustainable programming (Holt et al., Citation2008). Gatekeepers, policy makers, administrators and teachers of life skills need to believe in the potential and value of the life skills programs and receive appropriate training (James et al., Citation2006; Jegannathan et al., Citation2014). Further, long term monitoring and evaluation reviews are required to gather empirical evidence on the effectiveness of programs (Tuttle et al., Citation2006). This includes participant feedback and discussion on each life skills topic in order to improve application of the skills taught (WHO, Citation2001).

Given the role of life skills as a strong catalyst for the development of positive behaviour, building life skills in the early years of life will help children navigate their social and emotional challenges such as coping with emotional pain, conflict, peer pressure and relationship issues. How life skill programs are structured and delivered can significantly impact long-term program quality, therefore, it is important to deliver programs systematically in order to have a lasting impact on the health and wellbeing of participants (Holt et al., Citation2008).

Conclusion and future directions

This review examined published literature on the effectiveness of life skills education programs for adolescents in developed and developing countries. Findings reveal great promise for life skills education as a way to promote positive behaviour and to act as a buffer against risk-taking behaviors for adolescents in both developed and developing countries. The review revealed a number of quantitative studies examining life skills as an intervention program to effectively deal with adolescent issues such as self-esteem, decision-making, problem solving (Parvathy & Pillai, Citation2015), coping with stress, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, violence, HIV and AIDS (Botvin et al., Citation2001; Thompson et al., Citation2012) in controlled environments. Qualitative studies on life skills education were limited. Minimal research attention has been directed towards adolescents’ transfer of life skills knowledge into their daily lives.

There is a need to understand adolescents’ learning experiences within life skills education and to identify which skills are most effective at times of difficulty. Hence, inquiry into how adolescents acquire knowledge and skills through life skills programs and subsequently adopt positive attitudes and behaviours as a result is not well documented. This should be considered as an essential research priority. More work is needed to ensure proper transfer of life skills to attain long term results.

Understanding how knowledge, skills and values learnt from life skills education facilitates healthy transition to adulthood will add merit to life skills education programs in diverse contexts. Examining adolescent experiences within the embedded culture of the individual is important to understand how individuals from different backgrounds construct life skill knowledge into reality. Therefore, more studies are needed that embed life skills education within specific social and cultural settings. Studies can be framed within the view of experiences, such as narratives from adolescents’ lives, analysis of multiple perspectives and specific social contexts that shape their life skills experiences. Such approaches can provide a more nuanced perspective on the reality of program effectiveness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Aishath Nasheeda is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Human Ecology, University Putra Malaysia. Her field of study is Social Psychology. Her research interests include bullies, victims and mental health among adolescents. She is currently researching on life skills experiences of adolescents in the Maldives.

Haslinda Binti Abdullah is an associate professor and the deputy dean for Research and Innovation in the Faculty of Human Ecology, University Putra Malaysia. Her teaching and research concentrates on Applied and Developmental Psychology.

Steven Eric Krauss is an associate professor in the Faculty of Educational Studies, University Putra Malaysia. His teaching and research focuses on positive youth development in diverse cultural settings with a particular interest in intergenerational partnership as a support for youth thriving and well-being.

Nobaya Binti Ahmad is an associate professor, in the Faculty of Human Ecology, University Putra Malaysia. She currently heads the Department of Social and Developmental Sciences. Her research focuses on social issues in urban areas including housing, wellbeing of urban residents and marginalized groups in urban areas.

References

- Aparna, N., & Raakhee, A. S. (2011). Life skills education for adolescents : Its revelance and importance. GESJ: Education Science and Psychology, 2(19), 3–7.

- Botvin, G. J. (1998). Preventing adolescent drug abuse through life skills training: Theory, evidence of effectiveness and implementation issues. In J. Crane (Ed.), Social programs that work (pp. 225–257). New York, NY: Russel Sage Foundation.

- Botvin, G. J., Dusenbury, L., Baker, E., James-Ortiz, S., & Kerner, J. (1990). A skills training approach to smoking prevention among hispanic youth. American Journal of Health Promotion, 5(1), 70–71. doi:10.1007/BF00844872

- Botvin, G. J., & Griffin, K. W. (2004). Life skills training: Empirical findings and future directions. Journal of Primary Prevention, 71(5), 405–414. doi:10.1023/B:JOPP.0000042391.58573.5b

- Botvin, G. J., Griffin, K. W., Diaz, T., & Ifill-Williams, M. (2001). Drug abuse prevention among minority adolescents: Posttest and one-year follow-up of a school-based preventive intervention. Prevention Science, 2(1), 1–13. doi:10.1023/a:1010025311161

- Botvin, G. J., & Kantor, L. W. (2000). Preventing alcohol and tobacco use through life skills training. Alcohol Research & Health, 24(4), 250–257.

- Bwayo, J. K. W. (2014). Primary school pupils’ life skills development: The case for primary school pupils development in Uganda. Limerick: Mary Immaculate College.

- Campbell-Heider, N., Tuttle, J., & Knapp, T. R. (2009). The effect of positive adolescent life skills training on long term outcomes for high-risk teens. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 20(1), 6–15. doi:10.1080/10884600802693165

- Chaudhary, S., & Mehta, B. (2008). Life skills intervention at high school: A needed pedagogic shift.

- Cina, A., Röösli, M., Schmid, H., Lattmann, U. P., Fäh, B., Schönenberger, M., … Bodenmann, G. (2011). Enhancing positive development of children: Effects of a multilevel randomized controlled intervention on parenting and child problem behavior. Family Science, 2(1), 43–57. doi:10.1080/19424620.2011.601903

- Desai, M. (2010). A rights-based preventive approach for psychosocial well-being in childhood. Mumbai: Spinger.10.1007/978-90-481-9066-9

- Eisen, M., Zellman, G. L., & Murray, D. M. (2003). Evaluating the “lions-quest” “skills for adolescence” drug education program. Second-year behavior outcomes. Addictive Behaviors, 28(5), 883–97.10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00292-1

- Epstein, J. A., Griffin, K. W. & Botvin, G. J. (2000). Role of general and specific competence skills in protecting inner-city adolescents from alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61(3), 379–386.10.15288/jsa.2000.61.379

- Galagali, P. M. (2011). Adolescence and life skills. In R. Olyai & D. K. Dutta (Eds.), Recent advances in adolescent health (pp. 209–218). New Delhi: JAYPEE Brothers Medical Publishers (P) LTD.

- Giannotta, F., & Weichold, K. (2016). Evaluation of a life skills program to prevent adolescent alcohol use in two european countries: One-year follow-up. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(4), 607–624.10.1007/s10566-016-9349-y

- Givaudan, M., Leenen, I., Van De Vijver, F. J. R., Poortinga, Y. H., & Pick, S. (2008). Longitudinal study of a school based HIV/AIDS early prevention program for Mexican Adolescents. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13(1), 98–110. doi:10.1080/13548500701295256

- Givaudan, M., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., Poortinga, Y. H., Leenen, I., & Pick, S. (2007). Effects of a school-based life skills and HIV-prevention program for adolescents in mexican high schools. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(6), 1141–1162. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00206.x

- Goudas, M., Dermitzaki, I., Leondari, A., & Danish, S. (2006). The effectiveness of teaching a life skills program in a physical education context. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21(4), 429–438.10.1007/BF03173512

- Goudas, M., & Giannoudis, G. (2008). A team-sports-based life-skills program in a physical education context. Learning and Instruction, 18(6), 528–536. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.11.002

- Griffin, K. W., & Botvin, G. J. (2014). Alcohol misuse prevention in adolescents. Encyclopedia of Primary Prevention and Health Promotion. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5999-6

- Griffin, K. W., Botvin, G. J., Scheier, L. M., Epstein, J. A., & Doyle, M. M. (2002). Personal competence skills, distress, and well-being as determinants of substance use in a predominantly minority urban adolescent sample. Prevention Science, 3(1), 23–33. doi:10.1023/A:1014667209130

- Holt, N. L., Tink, L. N., Mandigo, J. L., & Fox, K. R. (2008). Do youth learn life skills through their involvement in high school sport? A case study. Canadian Journal of Education, 31(2), 281–304. doi:10.2307/20466702

- Huang, C.-M., Chien, L.-Y., Cheng, C.-F., & Guo, J.-L. (2012). Integrating life skills into a theory-based drug-use prevention program: Effectiveness among junior high students in Taiwan. Journal of School Health, 82(7), 328–335. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00706.x

- James, S., Reddy, P., Ruiter, R. A. C., McCauley, A., & van den Borne, B. (2006). The impact of an HIV and AIDS life skills program on secondary school students in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(4), 281–294. doi:10.1521/aeap.2006.18.4.281

- Jegannathan, B., Dahlblom, K., & Kullgren, G. (2014). Outcome of a school-based intervention to promote life-skills among young people in Cambodia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 9, 78–84. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2014.01.011

- Jones, M. I., & Lavallee, D. (2009). Exploring the life skills needs of British adolescent athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(1), 159–167.10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.06.005

- Kazemi, R., Momeni, S., & Abolghasemi, A. (2014). The effectiveness of life skill training on self-esteem and communication skills of students with dyscalculia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 863–866. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.798

- Khan, K. S., Kunz, R., Kleijnen, J., & Antes, G. (2003). Five steps to conducting a systematic review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96(3), 118–121.10.1177/014107680309600304

- Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

- Konkel, K. E. (2016). Is a life skills training infusion an effective strategy to reduce substance use aming at-risk teens in a mentoring program?. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University.

- Langford, B. H., Badeau , S. H., & Legters, L. (2015). Investing to improve the well-being of vulnerable youth and young adults: Recommendations for policy and practice. Retrieved from http://www.ytfg.org/2015/12/wellbeing/.

- Lillehoj, C. J., Trudeau, L., Spoth, R., & Wickrama, K. A. S. (2004). Internalizing, social competence, and substance initiation: Influence of gender moderation and a preventive intervention. Substance Use & Misuse, 39(6), 963–991. doi:10.1081/JA-120030895

- MacKillop, J., Ryabchenko, K. A., & Lisman, S. A. (2006). Life skills training outcomes and potential mechanisms in a community implementation: A preliminary investigation. Substance Use & Misuse, 41(14), 1921–1935. doi:10.1080/10826080601025862

- Mandel, L. L., Bialous, S. A., & Glantz, S. A. (2006). Avoiding “Truth”: Tobacco industry promotion of life skills training. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(6), 868–879. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.010

- Martin, K., Nelson, J., & Lynch, S. (2013). Effectiveness of school- based life-skills and alcohol education programmes: A review of the literature.

- Maryam, E., Davoud, M. M., Zahra, G., & Somayeh, B. (2011). Effectiveness of life skills training on increasing self-esteem of high school students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1043–1047. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.203

- McWhirter, J. J., McWhirter, B. T., McWhirter, E. H., & McWhirter, R. J. (2007). At risk youth: A Comprehensive response for counsellors, teachers, psychologists, and human service professionals (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Menrath, I., Mueller-Godeffroy, E., Pruessmann, C., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Ottova, V., Pruessmann, M., … Thyen, U. (2012). Evaluation of school-based life skills programmes in a high-risk sample: A controlled longitudinal multi-centre study. Journal of Public Health, 20(2), 159–170. doi:10.1007/s10389-011-0468-5

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, T. P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Munsi, K., Guha, D., Bengal, W., & Bengal, W. (2014). Status of life skill education in teacher education curriculum of saarc countries : A comparative evaluation. Journal of Education and Social Policy, 1(1), 93–99.

- Naseri, A., & Babakhani, N. (2014). The effect of life skills training on physical and verbal aggression male delinquent adolescents marginalized in karaj. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 4875–4879. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1041

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. (2010). Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Retrieved February 8, 2017, from http://www.ephpp.ca/index.html%5Cnhttp://www.ephpp.ca/PDF/Quality Assessment Tool_2010_2.pdf

- O’Hearn, T. C., & Gatz, M. (1999). Evaluating a psychosocial competence program for urban adolescents. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 20(2), 119–144. doi:10.1023/A:1021489932127

- Parvathy, V., & Pillai, R. R. (2015). Impact of life skills education on adolescents in rural school. International Journal of Advanced Research, 3(2), 788–794.

- Pick, S., Givaudan, M., Sirkin, J., & Ortega, I. (2007). Communication as a protective factor: Evaluation of a life skills HIV/AIDS prevention program for mexican elementary-school students. AIDS Education and Prevention, 19(5), 408–421. doi:10.1521/aeap.2007.19.5.408

- Pierce, S., Gould, D., & Camiré, M. (2017). Definition and model of life skills transfer. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 186–211. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2016.1199727

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., … Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC Methods Programme, 2006(April), 211–219. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536x.1995tb00261.x

- Prajapati, R., Sharma, B., & Sharma, D. (2017). Significance of life skills education. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 10(1), 1–6.

- Prajina, P. V. (2014). Impact of life skills among adolescents : A review, (2277), 3–4.

- Ryan, G. (2010). Guidance notes on planning a systematic review. Galway: James Hardiman Library.

- Savoji, A. P., & Ganji, K. (2013). Increasing mental health of university students through life skills training (LST). Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 1255–1259. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.739

- Siddaway, A. (2014). What is a systematic literature review and how do I do one?.

- Smith, E. A., Swisher, J. D., Vicary, J. R., Bechtel, L. J., Minner, D., Henry, K. L., & Palmer, R. (2004). Evaluation of life skills training and infused-life skills training in a rural setting: Outcomes at two years. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 48(1), 51–70.

- Strech, D., & Sofaer, N. (2012, February). How to write a systematic review of reasons. Journal of Medical Ethics. Institute of Medical Ethics. doi:10.1136/medethics-2011-100096

- Teyhan, A., Cornish, R., Macleod, J., Boyd, A., Doerner, R., & Sissons Joshi, M. (2016). An evaluation of the impact of “lifeskills” training on road safety, substance use and hospital attendance in adolescence. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 86, 108–113. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2015.10.017

- Thompson, R. G., Auslander, W. F., & Alonzo, D. (2012). Individual-level predictors of nonparticipation and dropout in a life-skills hiv prevention program for adolescents in foster care. AIDS Education and Prevention, 24(3), 257–269. doi:10.1521/aeap.2012.24.3.257

- Tuttle, J., Campbell-Heider, N., & David, T. M. (2006). Positive adolescent life skills training for high-risk teens: Results of a group intervention study. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 20(3), 184–191. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.10.011

- UNESCO. (2008). Gender-responsive life skills-based education advocacy brief gender-responsive life skills-based education.

- UNFPA. (2015). Sexual and reporoductive health of young people in asia and the pacific: A review of issues, policies and programmers (Vol. 1). Bangkok: Author. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- UNICEF. (2003). Definition of terms | life skills | UNICEF. Retrieved March 8, 2017, from https://www.unicef.org/lifeskills/index_7308.html

- UNICEF. (2010). Life skills-based curriculum project evaluation.

- UNICEF. (2012). Global evaluation of life skills education programmes.

- UNICEF. (2015). Review of the life programme: Maldives skills education.

- Vatankhah, H., Daryabari, D., Ghadami, V., & KhanjanShoeibi, E. (2014). Teaching how life skills (anger control) affect the happiness and self-esteem of tonekabon female students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 123–126. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.178

- Vicary, J. R., Henry, K. L., Bechtel, L. J., Swisher, J. D., Smith, E. A., Wylie, R., & Hopkins, A. M. (2004). Life skills training effects for high and low risk rural junior high school females. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 25(4), 399–416. doi:10.1023/B:JOPP.0000048109.40577.bd

- Weichold, K. (2014). Translation of etiology into evidence-based prevention: The life skills program IPSY. New Directions for Youth Development, 2014(141), 83–94, 12. doi:10.1002/yd.20088

- Weichold, K., & Blumenthal, A. (2016). Long-term effects of the life skills program IPSY on substance use: Results of a 4.5-year longitudinal study. Prevention Science, 17(1), 13–23.10.1007/s11121-015-0576-5

- Weichold, K., Tomasik, M. J., Silbereisen, R. K., & Spaeth, M. (2016). The effectiveness of the life skills program ipsy for the prevention of adolescent tobacco use : The mediating role of yielding to peer pressure. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 36(7), 881–908.10.1177/0272431615589349

- Wenzel, V., Weichold, K., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2009). The life skills program ipsy: Positive influences on school bonding and prevention of substance misuse. Journal of Adolescence, 32(6), 1391–1401. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.008

- WHO. (1993). Life skills education in schools. WHO/MNH/PSF/93.7A.Rev.2.

- WHO. (2001). Regional framework for introducing lifeskills education to promote the health of adolescents. World Health Project: ICP HSD 002/II.

- WHO. (2016). Adolescents: Helath risks and solutions. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs345/en/

- Yadav, P., & Iqbal, N. (2009). Impact of life skill training on self-esteem, adjustment and empathy among adolescents. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 35, 61–70.