ABSTRACT

This study examines the influences of childhood experiences (childhood social-economic situation, childhood community and campus quality, childhood family climate) on early career choice. Using the data of a large-scale nationwide stratified random sampling survey of life history across 28 provinces and municipalities in China, empirical results show that the lower quality of childhood experiences would increase the likelihood that youths choose to work in the public sector after adulthood. Also, male youths are generally more sensitive to the childhood experiences than female ones. Youths with migration experiences are generally more sensitive to the childhood family climate (and less sensitive to the childhood community/campus quality) than those that never migrate. Moreover, such influence is distinctly reflected in the choice of the first job, and gradually recedes into insignificance for the choice of the second and third job.

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have attracted increasing attention of studies regarding youths and adolescents’ behavioural and psychosocial consequences (e.g. addictive behaviour, aggression and depression, Matsuura, Hashimoto, & Toichi, Citation2013; Ramiro, Madrid, & Brown, Citation2010). The ACEs include but not limited to stressful status or events such as household dysfunction, interpersonal violence, childhood neglect or abuse. While it is widely admitted that the ACEs have strong impact on youths and adolescents’ behaviour tendency, the impact on early career choice outcome remains largely unexamined. According to the perspective of social cognitive career theory (SCCT) (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, Citation1994), the dynamic social-contextual factors during the growth (e.g. family, community, and campus conditions) affect the learning experiences through which career-relevant self-efficacy and outcome expectations are forged. As such, the experiences in early life (e.g. emotional neglect and abuse, family violence, parental mental health and drug/alcohol abuse) can impose implicit effect on people’s career choice after adulthood.

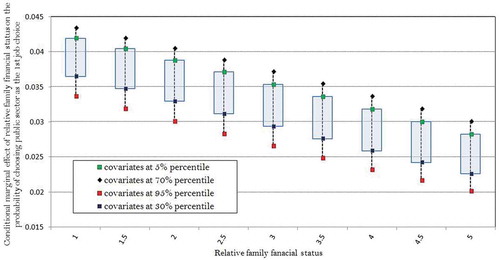

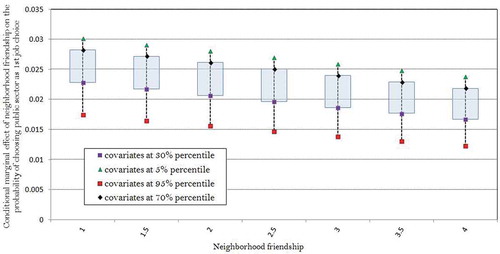

Figure 2. The conditional marginal effects of neighbourhood friendship on the probability of choosing public sector as the 1st job choice (according to logit model regression)

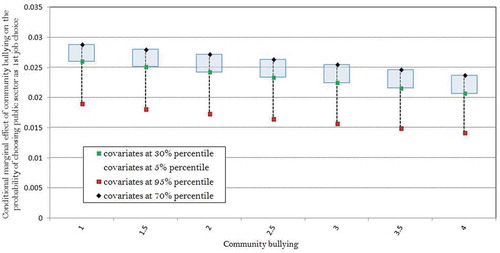

Figure 3. The conditional marginal effects of community bullying on the probability of choosing public sector as the 1st job choice (according to logit model regression)

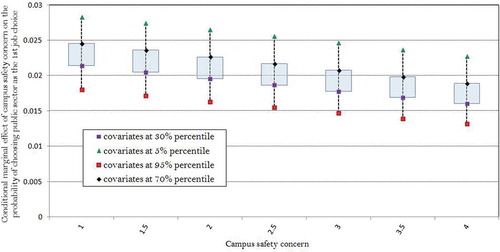

Figure 4. The conditional marginal effects of campus safety concern on the probability of choosing public sector as the 1st job choice (according to logit model regression)

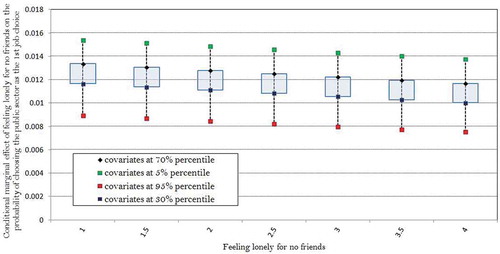

Figure 5. The conditional marginal effects of feeling lonely for no friends on the probability of choosing public sector as the 1st job choice (according to logit model regression)

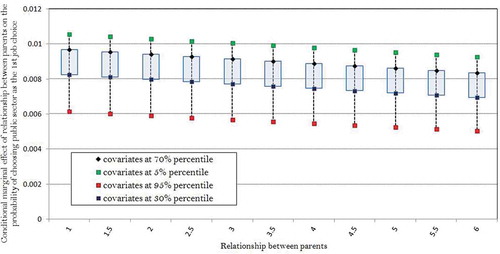

Figure 6. The conditional marginal effects of relationship between parents on the probability of choosing public sector as the 1st job choice (according to logit model regression)

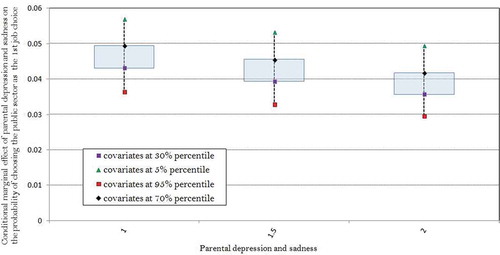

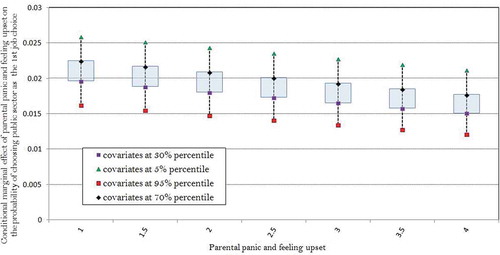

Figure 7. The conditional marginal effects of parental panic and feeing upset on the probability of choosing public sector as the 1st job choice (according to logit model regression)

As the most proximal social contextual factors that are ambient in one’s world during childhood come from his or her family of origin, community and campus, childhood family, community and campus experiences should be emphasized when we explore determinants driving youths and adolescents to make early career choice after adulthood. Despite having the theoretical importance, the influences of these contextual factors on youths and adolescents’ early career choice after adulthood have not been fully analysed (Hargrove, Creagh, & Burgess, Citation2002; Whiston & Keller, Citation2004). Some indirect signs show that people’s career choice can be associated with the childhood family climate and economic condition (Schröder, Schmitt-Rodermund, & Arnaud, Citation2011; Tang, Fouad, & Smith, Citation1999; Zellweger, Sieger, & Halter, Citation2011). People who have positive childhood experiences in such aspects can feel the confidence to cope with career challenges after their adulthood (Zellweger et al., Citation2011). They tend to have risk preference in their career pursuit (Whiston & Keller, Citation2004), and thus are less likely to put emphasis on job rewards of the public sector (e.g. job security, stable benefit, seniority-based promotion, appropriate workload and task significance; Chen & Bozeman, Citation2013; Chen & Hsieh, Citation2015; Lee & Choi, Citation2016). The risk preference, confidence to deal with challenges, and willingness to sacrifice job security for more career potentials would reduce the likelihood of choosing the career in the public sector. In contrast, those who are lack of the sense of security and are risk-averse are more likely to choose the public sector accordingly (Clark, Citation2016; Dong, Citation2015, Citation2017; Van de Walle, Steijn, & Jilke, Citation2015).

This study contributes to the existing literature in several aspects. First, this paper makes a preliminary exploration of the relationship between childhood experiences of youths and adolescents and their early career choice after adulthood, where empirical evidence is still absent for previous studies. Second, this paper, respectively, estimates and compares above impact by gender difference and migration experiences difference. Third, this paper evaluates the persistency of the influence of childhood experiences of youths and adolescents on career choice by estimating such impact from the 1st job to the 3rd. Fourth, the special focus on early career choice that is important for youths and adolescents’ future career trajectory is still rare in existing literature (Goldacre, Fazel, Smith, & Lambert, Citation2013). This study will fill this gap to some extent.

Literature review

The perspective of social cognitive career theory (SCCT)

SCCT describes the process through which people make choices in occupational pursuits (Lent et al., Citation1994). Anchored in general social cognitive theory developed by Bandura (Citation1986), SCCT makes efforts to help understand how external environment (e.g. social supports and barriers, like economic conditions, parental behaviours and peer influences) shapes one’s course of career development (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, Citation1996, Citation2000; Lent et al., Citation1999, Citation1998).

According to SCCT, career choice is influenced both by distal and proximal environmental factors. Based on the relative proximity to the career choice-making process, environmental influences are divided into these two basic categories. The first, distal category of environmental influences includes background contextual factors which can shape the development of career-relevant self-efficacy and outcome expectations (e.g. ‘if I choose this career field, what will happen?’) through affecting personal learning experiences. For example, the support or discouragement one obtains from engaging in particular activities outside of his or her career. The second, proximal, category refers to those contextual factors during active phases of career decision-making, such as career network contacts or exposure to discriminatory hiring practices. This standard of division also considers the temporal dimension. Contextual factors encountered in the past and those in the present correspond to these two categories, respectively, based on their relative proximity to the career choice-making process.

Childhood experiences including childhood social-economic situation, childhood community and campus quality, and childhood family climate can be viewed as a kind of choice-distal factors that precede and help shape personal interests, self-cognitions, or other influences on career choice through affecting personal learning experiences. People can take in values, attitudes or regulatory structure from the interaction process with their family, community, and campus during childhood (learning experiences), and internalize those as their own values, attitudes or regulatory structure (Gagné & Deci, Citation2005; Houston, Citation2011; Pedersen, Citation2015). ACEs (poorer social-economic situation, lower community and campus quality, and worse family climate during childhood) can diminish one’s coping efficacy and enhance the degree of the need for security, stability, or control (Coleman, Citation2003; Davies & Woitach, Citation2008; Gomez, Citation2014; Hackett & Betz, Citation1981; Pan, Sun, & Chow, Citation2011; Sabri, Coohey, & Campbell, Citation2012). In other words, the low level of coping efficacy and high degree of the need for security, stability, or control can gradually forge through learning from ACEs. Such cognition and needs may further have an implicit effect on the expectations for further career, such that those with low-level of risks and challenges are more likely to be the preferred career choices. In contrast, positive childhood experiences may promote the feelings of competence and risk tolerance (Whiston & Keller, Citation2004; Zellweger et al., Citation2011), whereby people may be more willing to pursue the career with relatively higher risks and challenges.

Indirect evidence about the relation of childhood experiences and career choice

The career choice of working in the public or private sector brings people distinct life in China. Higher job security (Hui, Lee, & Rousseau, Citation2004; Walsh & Zhu, Citation2007), lower work-life conflict and stable payment (Blecher, Citation2002), seniority-based career promotion (Cooke, Citation2000; Lewis, Citation2003), are all among the job rewards attracting talents to the public sector (Perry & Hondeghem, Citation2008). In contrast, the private sector is featured with performance-orientated career promotion and wage policy (Wei & Rowley, Citation2009), and known to have more unstable and differentiated payment, and higher risk of layoff.

The degree to which people put emphasis on the above job rewards of working in the public sector is subject to social contextual factors in their childhood. Indirect evidence presented by recent research suggests that childhood family climate can affect individual career choice as it shapes one’s capability to cope with adverse life experiences (Davies, Forman, Rasi, & Stevens, Citation2002; Kouros, Merrilees, & Cummings, Citation2008; Schudlich & Cummings, Citation2007). Individuals who experience poor family climate in childhood are found to be associated with the lack of career efficacy (Coleman, Citation2003; Davies & Woitach, Citation2008; Hackett & Betz, Citation1981; Pan et al., Citation2011). They may perceive it hard to work under pressure (Mann & Gilliom, Citation2004), and incline to avoid risks (Dulebohn, Citation2002). They are more willing to choose positions with the fixed payment and stable career development path (Turban, Lau, Ngo, Chow, & Si, Citation2001).

Not limited within the household, the influences of childhood experiences are also extended to the community and campus. The intra-community discord and interpersonal violence reduce the quality of individual perception of safety and security (Cummings et al., Citation2011; Lovell & Cummings, Citation2001). The exposure to the community discord and violence can frustrate individual risk-taking intention and behaviour in adulthood (Margolin & Gordis, Citation2000). The adverse community and campus experiences would impair individual confidence in pursuit of the venturous career, and increase individual emphasis on stable career development (Sabri et al., Citation2012). As such, the adverse community and campus situation can make people care more about the job rewards of working in the public sector.

More recently, the effect of childhood economic situation on individual career efficacy has been examined. The economic disadvantage hinders people’s access to resources that are helpful for early career exploration and constrains their perceived confidence in career development in adulthood (Gomez, Citation2014). Former adverse experiences of financial stress would also curtail people’s belief in their ability to perform tasks in career pursuit (Vannatter, Citation2012). Family economic distress in childhood can make people more easily suffer from poor emotional health (Menasco, Citation2012; Toomey & Christie, Citation1990), and more incline to avoid risks or unstable choices (Maner et al., Citation2007; Raghunathan & Pham, Citation1999; Wray & Stone, Citation2005), and thus they may put more emphasis on job security. Based on the indirect evidence above, it seems to be suggested that ACEs may have a higher likelihood of driving people to choose their career in the public sector given their tendency to make a risk-averse career choice.

Method and materials

Data source

The data come from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study – The life history survey (CHARLS-2014), which is collected by stratified random sampling. This widely used survey collects a high quality nationally representative sample of Chinese residents over the age of 45, and aims to serve the needs of scientific research relevant to health for the mid-aged and elderly (Zhao, Hu, Smith, Strauss, & Yang, Citation2012). Respondents of this survey are followed up every two years and the collected data are made public one year after the data collection has been completed. Hence, this survey is available to the public since 2016. This life history survey is implemented across 28 provinces and municipalities in China. It covers 150 counties including 450 communities and villages among which about 52.6% are rural areas and 47.4% are urban areas.

Measurement

Dependent variable

shows the details about measurements of variables. The binary dependent variable of this study is the type of job. Respondents that work in governments, public institutions, NGOs or rural collective economic organizations are public sector employees, while those that work in firms, individual or self-employed firms, or as farmers, individual households (i.e. self-employed small business) or others are private sector employees (more details about dependent variables have been shown in ).

Table 1. The overview of variables (measurement)

Table 2. The overview of dependent variables (frequency and percentage)

About the 1st job choice (Job 1), there are 14,887 answers in total, 12,101 (81.29%) are ‘public sector’, 2786 (18.71%) are ‘private sector’. There are 6406 answers in total reporting the 2nd job choice (Job 2), 2742 (42.80%) are ‘public sector’, 3664 (57.20%) are ‘private sector’. Besides, there are 4561 answers in total reporting the 3rd job choice (Job 3), 1289 (28.26%) are ‘public sector’, 3272 (71.74%) are ‘private sector’.

Independent variable

Independent variables in this study involve three categories of childhood experiences, (1) childhood social-economic situation, (2) childhood community/campus quality, (3) childhood family climate. More details have been shown in .

Table 3. The overview of independent and control variables (frequency and percentage)

The independent variable ‘relative family financial status’ belongs to ‘childhood social-economic situation’. The financial status of majority respondents (50.89%) is near the average level of the community or village. About 9.85% and 39.25% are, respectively, above and below the average level.

The independent variables ‘neighbourhood friendship’, ‘community bullying’, ‘campus safety concern’ and ‘feeling lonely for no friends’ belong to ‘childhood community/campus quality’. For ‘neighbourhood friendship’, majority answers (50.87%) are somewhat close-knit. For ‘community bullying’, about 72.82% respondents never suffer from community bullying. For ‘campus safety concern’, the majority of respondents (89.33%) never have such concern. For ‘feeling lonely for no friends’, about 79.19% respondents never have such feeling.

The independent variables ‘relationship between parents’, ‘parental panic and feeling upset’, ‘parental depression and sadness’ and ‘parental anxiety and nervousness’ belong to ‘childhood family climate’. For ‘relationship between parents’, about 73.89% answers are good and above, and the remaining 26.11% are fair and below. For ‘parental panic and feeling upset’, 70.72% (3.27%) respondents score the scale at the lowest (highest) level. For ‘parental depression and sadness’, 79.99% (9.36%) respondents score the scale at the lowest (highest) level. Finally, for ‘parental anxiety and nervousness’, 63.26% (4.72%) respondents score the scale at the lowest (highest) level.

Control variable

Following previous literature, we also control the effects of a series of control variables. More details have been shown in .

Gender difference is controlled in this study. Previous studies show that males display higher career aspiration, more entrepreneurship orientation and risk preference compared with females, and such gender differences affect career choice (Wigfield, Battle, Keller, & Eccles, Citation2002; Wilson, Kickul, & Marlino, Citation2007). In this study, 9706 (47.46%) respondents are males and 10,743 (52.54%) respondents are females.

Education is controlled as previous studies show that lower education is associated with a greater preference for public sector employment which is viewed as a safe career option (Block, Fisch, Lau, Obschonka, & Presse, Citation2016; Van de Walle et al., Citation2015). In this study, 2.90% respondents are college educated and above, 2.93% respondents are vocational school level educated, 33.81% respondents are middle school level educated, 60.36% respondents are primary school level educated and below.

Membership of CPC is controlled as previous studies show that the membership of Chinese Communist Party (CPC) is viewed as a kind of political social capital bringing wage and other rewards and thus serves as an incentive for CPC members to enter the public sector (Appleton, Knight, Song, & Xia, Citation2009). In this study, 18.27% respondents have CPC membership and 81.73% respondents do not.

Ethnic minority is controlled as previous studies show that ethnic minority group are more prejudiced and restricted in the private sector employment, and they are found more attracted by the public sector work (Battu & Zenou, Citation2010; Doverspike, Qin, Magee, Snell, & Vaiana, Citation2011). In this study, 9.86% respondents are ethnic minority and 90.14% respondents are not.

Religious belief is controlled as previous studies show that people with religious belief are more likely to choose public sector career and more dedicated to the public interest for their conception to take the public work as a kind of divine ‘calling’ (Hirsbrunner, Loeffler, & Rompf, Citation2012; Teresa Flanigan, Citation2010). In this study, 13.18% respondents have religious belief and 86.82% respondents do not.

Grouping difference

We match the data and construct the dataset that contains variables above without missing observations. The estimated sample thus includes 9293 non-missing observations. The overview of variables predicting the 1st job choice is displayed in .

Table 4. The overview of variables (grouping by the 1st job choice)

The results of Independent Sample T-test indicate that the mean values of independent variables significantly differ between respondents choosing the public sector and the private sector (Relative family financial status, t = −13.972; Neighbourhood friendship, t = −6.7140; Campus safety concern, t = −5.3549; Feeling lonely for no friends, t = −7.3616; Relationship between parents, t = −5.2791; Parental panic and feeling upset, t = −9.8287; Parental depression and sadness, t = −8.9655; Parental anxiety and nervousness, t = −7.2759; all above with p-value<0.01; Community bullying, t = −6.7140; with p-value<0.05).

Statistical analysis

Binary choice models

The statistical software Stata 13.1 is used in this study. Three types of binary choice models (i.e. the probit model, logit model and linear probability model) are used in the present study. The regression equations are displayed as follows:

Probability (Career choice = 1 | x1, x2, …, xn) = G (β0+ x1β1+…+xnβn)

Where, xi are independent variables, and βi are estimated parameters. The function G(·) is the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution/logistic distribution for the probit/logit model, while G(·) is linear when the linear probability model is used as the regression model.

The estimation of conditional marginal effect

Although the above estimation can provide the rough capturing of the effect of independent variables on dependent variable, the results of estimated nonlinear models (probit/logit model) reporting the mean marginal effect can cover the slight discrepancy of the marginal effect at different sample points. Therefore, for providing more detailed results, it becomes worthwhile to estimate the conditional marginal effect (CME) of independent variable when covariates are at different percentile.

More specifically, the marginal effect of independent variable xi to the response probability P (y = 1 | x1, x2, …, xn) can be derived as

Δ P (y = 1 | x1, x2, …, xn)/Δ xi ≈ g (β0+ x1β1+…+xnβn)βi

where g(·) is the probability density function of the normal/logistic distribution for the probit/logit model. Since g(·) is a nonlinear function rather than a constant, the above CME Δ P (y = 1 | x1, x2, …, xn)/Δ xi varies for different value combination of (x1, x2, …, xn). In practice, the common regression reports the mean marginal effect. If the independent variable xi is continuous, the consistent estimator can be expressed as E[g(x1,…xn; β1,…βn)]βi = [n−1Σ1≤i≤n g (x1,…xn; β1,…βn)]βi. If the independent variable xi is discrete, the consistent estimator can be expressed as E[ΔG(x1,…xn; β1,…βn)] = n−1[Σ1≤i≤n G (β0+ x1β1+…+xi-1βi-1+ βi.)- G(β0+ x1β1+…+xi-1βi-1)].

In this study, instead of just reporting the mean marginal effect, we estimate and illustrate the CMEs of independent variables when covariates are at the 5, 30, 70, 95 percentile, respectively (logit model), which can provide more details.

Empirical results

The effect of childhood experiences on the 1st job choice

reports the main results of this study. We estimate the impacts of childhood social-economic situation/childhood community and campus situation/childhood family climate on the 1st job choice. Results confirm that the 1st job choice is significantly associated with above aspects of childhood experiences. In detail, the deterioration of relative family financial status, poor neighbourhood friendship, community bullying, campus safety concern, feeling lonely for no friends, poor relationship between parents, parental panic and feeling upset, parental depression and sadness are shown to significantly increase the likelihood of choosing the public sector in the 1st job choice.

Table 5. The effects of childhood experiences on the 1st job choice

The conditional marginal effect (CME) of childhood experiences on the 1st job choice

To provide more detailed estimated results of nonlinear models, we also compute the CMEs of above independent variables on the 1st job choice at 5, 30, 70, 95 percentile of covariates, respectively (although we choose the logit model here, probit model results do not show differences in significance level). Results of – show that there have the nonlinear CMEs of above independent variables on the probability to choose the public sector as the 1st job choice. More specifically, for a given level of relative family financial status, the CME is ranked from high to low when covariates are at 70, 5, 30, 95 percentile, and for other independent variables, the CME is ranked from high to low when covariates are at 5, 70, 30, 95 percentile. Besides, for covariates are at given percentile, the CMEs are higher when the independent variables are lower, and thus all the – show a decreasing tendency (a down-stairs shape).

The effect of childhood experiences on the 1st job choice (by gender and migration grouping)

reports the respective regression results by gender (male and female) and migration experiences (migrants and people that never migrate). Results show males are generally more sensitive to the childhood experiences for the 1st job choice compared with females, and this is more specifically reflected in some aspects of childhood experiences (community bullying, feeling lonely for no friends, parental panic and feeling upset, parental depression and sadness). Besides, migrants are generally more sensitive to the childhood family climate compared with people that never migrate for the 1st job choice. People that never migrate are generally more sensitive to the childhood community/campus quality compared with migrants for the 1st job choice.

Table 6. The effects of childhood experiences on the 1st job choice (sub-groups)

The effect of childhood experiences on the 2nd and 3rd job choice

Another important issue raising our concern is whether childhood experiences would have long and lasting effect on the career choice. In order to respond to this concern, we examine the effects of childhood experiences on the 2nd and 3rd job choice. Among observations, we have 4365 non-missing ones reporting the 2nd job and 3294 non-missing ones reporting the 3rd job. reports the results of the effects of childhood experiences on the career choice for the 2nd and 3rd job. The 2nd job choice is found to still be significantly affected by community bullying, and parental panic and feeling upset, but to no longer be significantly affected by other determinants mentioned above. While for the 3rd job choice, the influences of all the determinants above recede into insignificance.

Table 7. The effects of childhood experiences on the 2nd and 3rd job choice

Discussion

The special attention of this study to the early career choice can be particularly worthwhile. Previous studies show that the prestige and quality of the 1st job can lay the foundation for the future career development, and the early career can significantly affect people’s entire career path (Judge, Kammeyer-Mueller, & Bretz, Citation2004). Also, the significant associations between the 1st job and subsequent jobs in many aspects, such as the job type, earnings loss, temporality, have been identified by previous studies (Gebel, Citation2010; Hamaaki, Hori, Maeda, & Murata, Citation2013; Wright & Christensen, Citation2010). As such, the early career choice has great implications for people life.

Also, the exploration of childhood experiences as determinants of the early career choice has special importance. Different from the present study that focuses on the experiences during a comparatively long period of early life, the existing literature that addresses the early career decision-making mainly investigates the traits of college students (e.g. career aspiration, entrepreneurship intention; Farmer, Wardrop, Anderson, & Risinger, Citation1995; Pihie & Akmaliah, Citation2009; Rothstein & Rouse, Citation2011). This treatment considers the traits of college students to be given and stable, and thus can inevitably omit that the traits are gradually formed in the long period of childhood. In this case, the investigation of childhood experiences in the present study can be more robust in tracing the origins.

Besides, the empirical finding suggests that male adolescences’ career decision-making is more susceptible to ACEs than females’. This finding is in line with previous empirical evidence that the career decision-making of males and females are dichotomous (Larson, Butler, Wilson, Medora, & Allgood, Citation1994). Males are socialized primarily to be the family financial providers, a role expressed through career endeavours (Larson et al., Citation1994). Consequently, males take their career decision-making extremely seriously and become more susceptible to their past experiences. In addition, empirical finding suggests that migrants are more sensitive to childhood family climate (less sensitive to childhood community/campus quality) compared with people that never migrate. This finding is consistent with the perception that people that never migrate can have more frequent interaction within the community and thus become more susceptible to the community influence than migrants. Also, migrants who experience residence place change can more heavily rely on their within-family support compared with people that never migrate, and thus more susceptible to the childhood family climate.

However, the determinants of career choice are complex, and it is very likely that the childhood experiences are not the only perspective of exploring the antecedents of young adolescents’ early career choice. In contrast with the focus on the childhood experiences in our study, many studies concentrate on the linkages between the career choice and internal traits, such as public service motivation (Carpenter, Doverspike, & Miguel, Citation2012; Clerkin & Coggburn, Citation2012; Gabris & Simo, Citation1995; Pedersen, Citation2013), altruism (Jirwe & Rudman, Citation2012), and personality (Antony, Citation1998; Garcia-Sedeñto, Navarro, & Menacho, Citation2009). Although far beyond the scope of this study, these perspectives have shown that the motivations of early career decision-making are dynamic and the precise prediction of young adolescents’ early career choice can be difficult. As such, the findings of this study may roughly shed some light on how childhood experiences can affect young adolescents’ early career choice, rather than provides a solution to accurately predict their career decisions merely according to their childhood experiences.

Conclusion

This study empirically investigates the associate between childhood experiences and the early career choice of young adolescents. Empirical results show that the ACEs can significantly increase the likelihood of choosing a career in the public sector for the 1st job, but such impact turns less significant for the 2nd job and insignificant for the 3rd job. Also, males are generally more sensitive to the childhood experiences for the 1st job choice compared with females. Migrants are generally more sensitive to the childhood family climate (less sensitive to the childhood community/campus quality) for the 1st job choice compared with people that never migrate. These findings are consistent with the cognition that individual career development is dynamic with the growth of experiences, expansion of vision, and accumulation of social connections and resources. Thus childhood experiences can be of most importance for the early career choice, and such impact is just distinctly reflected in the choice of the 1st job.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bocong Yuan

Bocong Yuan is a research associate professor of School of Tourism Management, Sun Yat-sen University. His current research focuses on development economics and public policy (industrial, environment and public health).

Jiannan Li

Jiannan Li is a research associate professor of International School of Business & Finance, Sun Yat-sen University. Her main research focuses on organizational behavior and occupational health.

References

- Antony, J. S. (1998). Personality-career fit and freshman medical career aspirations: A test of Holland‘s theory. Research in Higher Education, 39(6), 679–698.

- Appleton, S., Knight, J., Song, L., & Xia, Q. (2009). The economics of communist party membership: The curious case of rising numbers and wage premium during China‘s transition. The Journal of Development Studies, 45(2), 256–275.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Battu, H., & Zenou, Y. (2010). Oppositional identities and employment for ethnic minorities: Evidence from England. The Economic Journal, 120(542), F52–F71.

- Blecher, M. J. (2002). Hegemony and workers‘ politics in China. The China Quarterly, 170, 283–303.

- Block, J. H., Fisch, C. O., Lau, J., Obschonka, M., & Presse, A. (2016). Who prefers working in family firms? An exploratory study of individuals’ organizational preferences across 40 countries. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(2), 65–74.

- Carpenter, J., Doverspike, D., & Miguel, R. F. (2012). Public service motivation as a predictor of attraction to the public sector. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 509–523.

- Chen, C. A., & Bozeman, B. (2013). Understanding public and nonprofit managers‘ motivation through the lens of self-determination theory. Public Management Review, 15(4), 584–607.

- Chen, C. A., & Hsieh, C. W. (2015). Does pursuing external incentives compromise public service motivation? Comparing the effects of job security and high pay. Public Management Review, 17(8), 1190–1213.

- Clark, A. F. (2016). Toward an entrepreneurial public sector: Using social exchange theory to predict public employee risk perceptions. Public Personnel Management, 45(4), 335–359.

- Clerkin, R. M., & Coggburn, J. D. (2012). The dimensions of public service motivation and sector work preferences. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 32(3), 209–235.

- Coleman, P. K. (2003). Perceptions of parent - child attachment, social self-efficacy, and peer relationships in middle childhood. Infant and Child Development, 12(4), 351–368.

- Cooke, F. L. (2000). Manpower restructuring in the state-owned railway industry of China: The role of the state in human resource strategy. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(5), 904–924.

- Cummings, E. M., Merrilees, C. E., Schermerhorn, A. C., Goeke-Morey, M. C., Shirlow, P., & Cairns, E. (2011). Longitudinal pathways between political violence and child adjustment: The role of emotional security about the community in Northern Ireland. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(2), 213–224.

- Davies, P. T., Forman, E. M., Rasi, J. A., & Stevens, K. I. (2002). Assessing children’s emotional security in the interparental relationship: The security in the interparental subsystem scales. Child Development, 73(2), 544–562.

- Davies, P. T., & Woitach, M. J. (2008). Children‘s emotional security in the interparental relationship. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(4), 269–274.

- Dong, H. K. D. (2015). The effects of individual risk propensity on volunteering. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(1), 5–18.

- Dong, H. K. D. (2017). Individual risk preference and sector choice: Are risk-averse individuals more likely to choose careers in the public sector? Administration & Society, 49(8), 1121–1142.

- Doverspike, D., Qin, L., Magee, M. P., Snell, A. F., & Vaiana, L. P. (2011). The public sector as a career choice: Antecedents of an expressed interest in working for the federal government. Public Personnel Management, 40(2), 119–132.

- Dulebohn, J. H. (2002). An investigation of the determinants of investment risk behavior in employer-sponsored retirement plans. Journal of Management, 28(1), 3–26.

- Farmer, H. S., Wardrop, J. L., Anderson, M. Z., & Risinger, R. (1995). Women‘s career choices: Focus on science, math, and technology careers. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(2), 155.

- Gabris, G. T., & Simo, G. (1995). Public sector motivation as an independent variable affecting career decisions. Public Personnel Management, 24(1), 33–51.

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362.

- Garcia-Sedeñto, M., Navarro, J. I., & Menacho, I. (2009). Relationship between personality traits and vocational choice. Psychological Reports, 105(2), 633–642.

- Gebel, M. (2010). Early career consequences of temporary employment in Germany and the UK. Work, Employment and Society, 24(4), 641–660.

- Goldacre, M. J., Fazel, S., Smith, F., & Lambert, T. (2013). Choice and rejection of psychiatry as a career: Surveys of UK medical graduates from 1974 to 2009. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(3), 228–234.

- Gomez, K. (2014). Career aspirations and perceptions of self-efficacy of fourth- and fifth-grade students of economic disadvantage (Doctoral dissertation). Pennsylvania: Lehigh University.

- Hackett, G., & Betz, N. E. (1981). A self-efficacy approach to the career development of women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 18(3), 326–339.

- Hamaaki, J., Hori, M., Maeda, S., & Murata, K. (2013). How does the first job matter for an individual’s career life in Japan? Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 29, 154–169.

- Hargrove, B. K., Creagh, M. G., & Burgess, B. L. (2002). Family interaction patterns as predictors of vocational identity and career decision-making self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(2), 185–201.

- Hirsbrunner, L. E., Loeffler, D. N., & Rompf, E. L. (2012). Spirituality and religiosity: Their effects on undergraduate social work career choice. Journal of Social Service Research, 38(2), 199–211.

- Houston, D. J. (2011). Implications of occupational locus and focus for public service motivation: Attitudes toward work motives across nations. Public Administration Review, 71(5), 761–771.

- Hui, C., Lee, C., & Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Employment relationships in China: Do workers relate to the organization or to people? Organization Science, 15(2), 232–240.

- Jirwe, M., & Rudman, A. (2012). Why choose a career in nursing? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(7), 1615–1623.

- Judge, T. A., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. O. H. N., & Bretz, R. D. (2004). A longitudinal model of sponsorship and career success: A study of industrial-organizational psychologists. Personnel Psychology, 57(2), 271–303.

- Kouros, C. D., Merrilees, C. E., & Cummings, E. M. (2008). Marital conflict and children’s emotional security in the context of parental depression. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(3), 684–697.

- Larson, J. H., Butler, M., Wilson, S., Medora, N., & Allgood, S. (1994). The effects of gender on career decision problems in young adults. Journal of Counseling & Development, 73(1), 79–84.

- Lee, G., & Choi, D. L. (2016). Does public service motivation influence the college students’ intention to work in the public sector? Evidence from Korea. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(2), 145–163.

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 79–122.

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1996). Career development from a social cognitive perspective. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development (pp. 373–421). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 36.

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Suthakaran, V., Talleyrand, R., Davis, T., Chopra, S. B., & Brenner, B. (1999, August). Contextual supports and barriers to math-related choice behavior. Paper presented at the 107th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Boston.

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Veerasamy, S., Talleyrand, R., Chai, C.-M., Davis, T., … McPartland, E. B. (1998, July). Perceived supports and barriers to career choice. Paper presented at the meeting of the National Career Development Association, Chicago.

- Lewis, P. (2003). New China - old ways? A case study of the prospects for implementing human resource management practices in a Chinese state-owned enterprise. Employee Relations, 25(1), 42–60.

- Lovell, E. L., & Cummings, E. M. (2001). Conflict, conflict resolution and the children of Northern Ireland: Towards understanding the impact on children and families. South Bend, IN: Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame.

- Maner, J. K., Richey, J. A., Cromer, K., Mallott, M., Lejuez, C. W., Joiner, T. E., & Schmidt, N. B. (2007). Dispositional anxiety and risk-avoidant decision-making. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(4), 665–675.

- Mann, B. J., & Gilliom, L. A. (2004). Emotional security and cognitive appraisals mediate the relationship between parents‘ marital conflict and adjustment in older adolescents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 165(3), 250–271.

- Margolin, G., & Gordis, E. B. (2000). The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 445–479.

- Matsuura, N., Hashimoto, T., & Toichi, M. (2013). Associations among adverse childhood experiences, aggression, depression, and self-esteem in serious female juvenile offenders in Japan. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 24(1), 111–127.

- Menasco, M. A. (2012). Family financial stress and adolescent substance use: An examination of structural and psychosocial factors. In L. B. Sampson (Ed.), Economic stress and the family (pp. 285–315). UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

- Pan, W., Sun, L. Y., & Chow, I. H. S. (2011). The impact of supervisory mentoring on personal learning and career outcomes: The dual moderating effect of self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 78(2), 264–273.

- Pedersen, M. J. (2013). Public service motivation and attraction to public versus private sector employment: Academic field of study as moderator? International Public Management Journal, 16(3), 357–385.

- Pedersen, M. J. (2015). Activating the forces of public service motivation: Evidence from a low-lntensity randomized survey experiment. Public Administration Review, 75(5), 734–746.

- Perry, J. L., & Hondeghem, A. (2008). Motivation in public management: The call of public service. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Pihie, Z. A. L., & Akmaliah, Z. (2009). Entrepreneurship as a career choice: An analysis of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention of university students. European Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2), 338–349.

- Raghunathan, R., & Pham, M. T. (1999). All negative moods are not equal: Motivational influences of anxiety and sadness on decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 79(1), 56–77.

- Ramiro, L. S., Madrid, B. J., & Brown, D. W. (2010). Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and health-risk behaviors among adults in a developing country setting. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(11), 842–855.

- Rothstein, J., & Rouse, C. E. (2011). Constrained after college: Student loans and early-career occupational choices. Journal of Public Economics, 95(1–2), 149–163.

- Sabri, B., Coohey, C., & Campbell, J. (2012). Multiple victimization experiences, resources, and co-occurring mental health problems among substance-using adolescents. Violence and Victims, 27(5), 744–763.

- Schröder, E., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., & Arnaud, N. (2011). Career choice intentions of adolescents with a family business background. Family Business Review, 24(4), 305–321.

- Schudlich, T. D. D. R., & Cummings, E. M. (2007). Parental dysphoria and children’s adjustment: Marital conflict styles, children’s emotional security, and parenting as mediators of risk. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(4), 627–639.

- Tang, M., Fouad, N. A., & Smith, P. L. (1999). Asian Americans‘ career choices: A path model to examine factors influencing their career choices. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(1), 142–157.

- Teresa Flanigan, S. (2010). Factors influencing nonprofit career choice in faith-based and secular NGOs in three developing countries. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 21(1), 59–75.

- Toomey, B. G., & Christie, D. J. (1990). Social stressors in childhood: Poverty, discrimination, and catastrophic events. In A. Eugene (Ed.), Childhood stress (pp. 423–456). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Turban, D. B., Lau, C. M., Ngo, H. Y., Chow, I. H., & Si, S. X. (2001). Organizational attractiveness of firms in the People‘s Republic of China: A person-organization fit perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 194–206.

- Van de Walle, S., Steijn, B., & Jilke, S. (2015). Extrinsic motivation, PSM and labour market characteristics: A multilevel model of public sector employment preference in 26 countries. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 81(4), 833–855.

- Vannatter, A. (2012). Influence of generational status and financial stress on academic and career self-efficacy (Doctoral dissertation). Indiana: Ball State University.

- Walsh, J., & Zhu, Y. (2007). Local complexities and global uncertainties: A study of foreign ownership and human resource management in China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(2), 249–267.

- Wei, Q., & Rowley, C. (2009). Pay for performance in China‘s non-public sector enterprises. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 1(2), 119–143.

- Whiston, S. C., & Keller, B. K. (2004). The influences of the family of origin on career development: A review and analysis. The Counseling Psychologist, 32(4), 493–568.

- Wigfield, A., Battle, A., Keller, L. B., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Sex differences in motivation, self-concept, career aspiration, and career choice: Implications for cognitive development. In A. McGillicuddy-De Lisi & R. De Lisi (Eds.), Biology, society, and behavior: The development of sex differences in cognition (pp. 93–124). Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing.

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406.

- Wray, L. D., & Stone, E. R. (2005). The role of self‐esteem and anxiety in decision making for self versus others in relationships. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 18(2), 125–144.

- Wright, B. E., & Christensen, R. K. (2010). Public service motivation: A test of the job attraction–Selection–Attrition model. International Public Management Journal, 13(2), 155–176.

- Zellweger, T., Sieger, P., & Halter, F. (2011). Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(5), 521–536.

- Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J., & Yang, G. (2012). Cohort profile: The China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(1), 61–68.