ABSTRACT

Many things play a role in the tendency to engage in cyberbullying. This study aimed to identify the determinant factors of the tendency to engage in cyberbullying by adolescents in Java. A sample of 1038 teenagers aged between 12 and 18 who used internet-connected electronic information and technology equipment. The measuring instruments used in this study included a cyberbullying tendency scale, an empathy scale, a self-esteem scale, a friendship quality scale, and an emotion regulation scale. Path analysis was used to process the data. The data showed that self-esteem served as a predictor of cyberbullying tendency whose relationship was negative only when it was mediated by emotion regulation. Friendship quality was a predictor of cyberbullying tendency both in a direct fashion and mediated by empathy.

Introduction

The internet has become a necessity among adolescents (Nixon, Citation2014; Quarshie, Citation2009). The existence of the internet has positive impacts including the ease of accessing information, the opportunity to interact with people who live far apart, the availability of various entertainment media, and the convenience of online shopping (Rahayu, Citation2012; Redekopp & Kalanda, Citation2014; Safaria, Citation2015). On the other hand, the internet also has negative impacts including the dissemination of irresponsible news, cybercrimes, and internet addiction leading to various issues including cyberbullying, just to name a few (Lazuras, Barkoukis, Ourda, & Tsorbatzoud, Citation2013).

Cyberbullying has been defined as any form of aggressive communication using information technology that is deliberately disseminated through cyberspace (William & Guerra, Citation2007). The content of the message conveyed is basically psychological violence (Ybarra & Mitchell, Citation2004). The cyberbullying perpetrator (the bully) targets an individual (Smith et al., Citation2008) who is weaker than him/her and cannot defend himself/herself with ease (Smith et al., Citation2008). The aim is to humiliate, harass, or intimidate the victim (Hinduja & Patchin, Citation2010). This action is carried out repeatedly (Smith et al., Citation2008; Ybarra & Mitchell, Citation2004). Cyberbullying can be done using a computer or a cell phone through electronic mail, text messages, websites, and chat rooms (Smith et al., Citation2008).

Cyberbullying is characterized by four aspects (Vandebosch & Cleemput, Citation2008), namely:

The perpetrator’s intentionality. The perpetrator has an intention to hurt the victim as shown in the actions that cause the victim to suffer (Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder, & Lattanner, Citation2014; Olweus, Citation2010). The action may be carried out repeatedly by a person or a group who do it for fun (Sticca & Perren, Citation2012).

Repetition. The repetition in cyberbullying is not only in the form of repetition of a behavior (or behaviors) that cause the victim to suffer but also when the mockery sent via the internet is seen by many people and then more widely spread to others (Menesini & Nocentini, Citation2009).

Power imbalance. A power imbalance occurs when the victim finds it difficult to defend oneself against the aggressive behavior addressed to him/her by the cyberbully (Smith et al., Citation2008). This suggests that the cyberbullying perpetrator(s) has greater power than the victim (Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2012).

Anonymity and publicity. Most teens do cyberbullying anonymously or use aliases (Vandebosch & Cleemput, Citation2008). The anonymity in cyberbullying has more negative consequences than those that are not anonymized (Sticca & Perren, Citation2012). What is meant by publicity in cyberbullying is that the negative information sent can be spread widely and be passed on to others quite easily (Kowalski & Limber, Citation2007; Menesini et al., Citation2012).

In various countries, the dominance of teenage boys in cyberbullying practices is a common phenomenon (Barlett & Coyne, Citation2014). Men are associated with masculine traits (Navarro, Yubero, & Larranaga, Citation2016), tend to be more advanced in terms of knowledge about technology, and tend to be more expressive, which makes them more likely to engage in cyberbullying than their female counterparts (Huffman, Whetten, & Huffman, Citation2013). Women are identified with feminine traits (Navarro et al., Citation2016) that are identical to tenderness. In Indonesia, cyberbullying is mostly done by men (Sartana & Afriyeni, Citation2017).

The results of Smith et al.’s (Citation2008) study showed that around 67% to 100% of American students were involved in cyberbullying. A similar finding has been found in Indonesia. For example, Safaria (Citation2015) found that 9% of students claimed to have engaged in cyberbullying several times, and 40% of students claimed to have been victims of bullying. In the subsequent study, it was found that 80% of junior high school students and 83% of high school students claimed to have been victims of cyberbullying (Safaria, Citation2016; Safaria, Tentama, & Suyono, Citation2016). This suggests that the prevalence of adolescents who become perpetrators and/or victims of cyberbullying in Indonesia is quite alarming.

This present study was done with Javanese-Indonesian adolescents. Some of Javanese adolescents’ characteristics are thought to be related to personal and situational factors as mentioned above. Javanese people in general still hold some life values and attitudes, one of which is respect. That respect is a value held by Javanese people was observed several decades ago by Geertz (Citation1983) andt is still valid to date (Lestari, Citation2012). This was evident in a study by Lestari, Faturochman, Adiyanti, and Walgito (Citation2013); the findings showed that respect and honesty were still firmly held values. The value of respect can be represented in the everyday life in the manners or social rules that require individuals to be able to take the appropriate positions in the social order (Suseno, Citation1997). Another principle that is still taught by parents to their children is harmony (Lestari, Citation2012; Suseno, Citation1997). Harmony is a central element in Javanese values (Geertz, Citation1983). Harmony serves to maintain peace so as to prevent conflicts from arising (Suseno, Citation1997). In relation to cyberbullying, the principles of harmony and respect are assumed to underlie the behaviors of these teenagers.

The principle of respect requires an individual to be able to control himself/herself to enable him/her to display manners (Geertz, Citation1983) that require him/her to control himself/herself, including his/her emotions. It takes proper regulation to enable him/her to display behaviors that are in accordance with the prevailing norms in his/her environment. The formation of self-esteem is influenced by an individual’s participation in his/her social environment. Success in dealing with interpersonal conflict can give rise to a sense of self-worth in him/her (Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2010). Self-esteem is a personality variable associated with cyberbullying (Ryckman, Citation2008); in either a high or low levels, it can be a direct cause of violence (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, Citation2003). Studies found different results. Some studies found that self-esteem is a negative predictor of both cyberbullying (Brewer & Kerslake, Citation2015; Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2010) and bullying behaviors (Uba, Yaacoob, Juhari, & Talib, Citation2010). However, a study by Reginasari (Citation2017) with high school adolescent groups found that the majority (82.6%) of high self-esteem participants tend to engage in high-level cyberbullying. The suspected cause was a low emotion regulation capacity during adolescence, the developmental period during which young people’s emotional state is fluctuating (Santrock, Citation2012). Other research found that self-esteem contributes positively to emotion regulation (Gomez, Quiñones-Camacho, & Davis, Citation2018), whereas emotion regulation contributes negatively to cyberbullying tendency (Chen, Ho, & Lwin, Citation2016; Pelegrini in Perren & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, Citation2012). Research with 90 children aged between 12 and 14 years who had been using information technology (IT) for at least 2 years showed that there was a negative relationship between emotion regulation and the adolescents’ tendency to engage in cyberbullying (Mawardah & Adiyanti, Citation2014).

Gross and Thompson (Citation2007) define emotion regulation as a series of processes in which emotions are regulated according to individual goals either automatically or under control, consciously or unconsciously, and involve various components that continuously work. The aspects of emotion regulation reflect an individual’s cognitive processes starting from situation selection to situation modification, to attention deployment, to cognitive change, to response modulation.

The principle of harmony has implications on the quality of friendships the adolescents formed. That the quality of friendship is crucial is a characterizing feature of teenagers. The quality of adolescent friendship includes the following six aspects (Parker & Asher, Citation1993): (a) validation and caring: the extent to which friendships are characterized by support and care; (b) companionship and recreation: the condition when someone spends time with his/her friends; (c) help and guidance: the extent to which friends can help each other; (d) intimate exchange: a relationship characterized by disclosure of personal information; (e) conflict and betrayal: a relationship characterized by arguments, disputes, and distrust; and (f) conflict resolution: the method used to resolve disputes in friendship relationships.

With the increasing use of IT and social media, many friendships between teenagers are also carried out through social media (Ang & Goh, Citation2010; Baym, Citation2010), either in positive or negative forms. Negative relationships with friends can be a trigger for the emergence of mutual humiliation, hostility, unfair competition, and disharmony (Hinduja & Patchin, Citation2008). One form of disharmony between friends that is expressed through social media is bullying. On the side of the perpetrator, cyberbullying can reduce tension so as to alleviate negative emotions (Agnew, Citation1992; Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2011), whereas on the victim’s side, it can have adverse impacts. The results of Healy’s (Citation2013) study showed that cyberbullies have a low quality friendship. In the group of Javanese adolescents, a low quality friendship indicates a lack of harmony.

Harmony manifested in a high quality friendship can make a teenager easily understand the condition his/her friend is dealing with as reflected in his/her empathic attitudes. Empathy as a part of personal factors (Kowalski et al., Citation2014) has a negative correlation with adolescents’ involvement in cyberbullying (Ang & Goh, Citation2010; Pornari & Wood, Citation2010; Sticca & Perren, Citation2013; Walrave & Heirman, Citation2012). Cyberbullies have low scores on both cognitive and affective empathies. Adolescents with good quality friendships are more likely to have high empathic qualities (Ang & Goh, Citation2010). This explains the role of empathy in enabling the inhibition of cyberbullying, especially when the quality of friendship is experiencing tension.

Davis (Citation1996) divides empathy into two basic aspects: cognitive and affective. The cognitive aspect of empathy is the intellectual capacity that an individual has to identify, understand, and deduce the perspectives of others, while the affective aspect of empathy is an individual’s capacity to feel the situation and the emotions experienced by others and give a response that is almost the same as what that person would give in that situation.

Ang and Goh (Citation2010) found that adolescents with lower empathy scores have higher scores on cyberbullying. Compared to adolescents who are not involved in cyberbullying, adolescents involved in cyberbullying have lower scores on empathy scales (Steffgen, König, Pfetsch, & Melzer, Citation2011). In another study, it was demonstrated that the victims of cyberbullying have lower levels of empathy when compared to individuals who are not involved in cyberbullying (Krumbholz-Schultze & Scheithauer, Citation2009). The link between empathy and cyberbullying is enabled by the effect of online inhibition, which causes a reduction in empathy and in turn leads to cyberbullying. Anonymity provides a great opportunity for internet users to act without considering the moral aspects (Ramdhani, Citation2016). The results of these studies confirm that empathy has a negative role in determining cyberbullying in adolescents.

The implication of these values is the emerging mutual respect and friendliness in the adolescents’ friendships, which results in a low level of cyberbullying. However, it turns out that cyberbullying is also common among teenagers in Java (Kristinawati, Citation2016). In Kristinawati’s study, 66% of junior high school teenagers and 77% of high school teenagers engaged in bullying. The question that results is as follows: what are the determining factors that give rise to the cyberbullying tendency?

A variable that is associated with respect is self-esteem, and that is likely to be moderated by emotion regulation that can hinder the cyberbullying tendency. A variable that is associated with harmony is friendship, a quality that is likely to be moderated by empathy, which can hinder the cyberbullying tendency.

Based on the description above, the research question of this present study was as follows: Can emotion regulation and empathy be the mediators of the influence of self-esteem and friendship quality on the cyberbullying tendency in Javanese adolescents?

Hypothesis

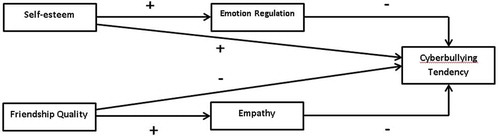

Based on the above literature review, this present study formulated two hypotheses that (1) there is a role of self-esteem in cyberbullying tendency with the mediation of emotion regulation, and (2) there is a role of friendship quality in cyberbullying tendency with the mediation of empathy. See .

Methods

Participants

The sample in this study were 1038 junior and senior high school students. The selection of participants was based on the following criteria: (1) adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years who (2) use or have electronic information and communication technology equipment, and (3) have access to an internet network and use electronic devices for ± 6 hours a week. According to Patchin and Hinduja (Citation2010), adolescents who are often connected to the internet (more than six hours a week) tend to be more susceptible to cyberbullying. The participants came from six schools located in large and small cities in Yogyakarta, Java, Indonesia. All participants expressed their consents to participate in the study.

Research instruments

This study used five research scales developed by the authors based on the theoretical concepts of each variable. The cyberbullying tendency scale was developed based on the aspects of cyberbullying behavior that included: (1) intention, (2) repetition, (3) power imbalance, and (4) publicity-anonymity. A sample item on this scale was: ‘I feel compelled to share images (memes) shared through private chats to me by others to Line/WhatsApps/BBM groups.’ Each item had five alternative responses scored one to five, respectively; the alternative responses were almost always, often, rarely, occasionally, and never. The reliability coefficient of this scale was 0.88.

The adolescents’ self-esteem scale used in this present study was a modified form of Coopersmith’s (Citation1967) Self-Esteem Inventory scale, which was compiled based on the aspects of self-esteem that include success, values, aspiration, and defense. The modification of the Self-Esteem Inventory Scale was done by editing the sentences and increasing the number of alternative responses. This adolescents’ self-esteem scale had 34 items, each of which had 4 alternative responses ranging from absolutely appropriate (1) to absolutely inappropriate (4). A sample item on this scale was ‘I am sure I can change myself to be better than now.’ The reliability coefficient of this scale was 0.896.

The emotion regulation scale was based on five emotion regulation strategies proposed by Gross and Thompson (Citation2007), namely: (1) situation selection, (2) situation modification, (3) attention deployment, (4) cognitive change, and (5) respond modulation. A sample item on this scale was ‘When there is a problem, I intend to shut myself in a room all the time.’ The emotion regulation scale consisted of 18 items, each of which had 4 alternative responses ranging from absolutely inappropriate (1) to absolutely appropriate (4). Its Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient was 0.802.

Friendship quality in this study was measured using a friendship quality scale that was a modification of Parker and Asher (Citation1993) friendship quality scale that measured six aspects of friendship quality, namely: support and attention, conflict and betrayal, togetherness and pleasure, help and guidance, openness, and conflict resolution. Sample items on this particular scale included ‘Me and my friends live very close to each other’ and ‘Our friendship makes us feel important and special to each other.’ The friendship quality scale had 35 items with a reliability coefficient of 0.952.

The empathy scale consisted of 23 items. The empathy scale was based on aspects of the capacity for empathy from Davis (Citation1996), which consist of cognitive aspects including the ability to put oneself in other people’s perspective (perspective taking) and fantasy, as well as affective aspects including the ability to focus on empathy (emphatic concern) and personal anxiety when establishing interpersonal relationships with others (personal distress). The sample items on this scale included ‘I often have a gentle feeling, worried about people who are less fortunate than me.’ Each item of this scale had four alternative responses including absolutely inappropriate (1), inappropriate (2), appropriate (3), and absolutely appropriate (4). This scale reliability coefficient is 0.886.

Research data analysis

The collected data were analyzed with Path Analysis.

Results

This study provided an opportunity for 1129 people to participate. Based on the initial screening, 1038 (91%) participants reported having had repeated negative communications with their friends such as sending offensive, defamatory, angry, or obscene messages. The age of participants ranged from 12 to 18 years (M = 16.21; SD = 1.60).

shows between-variable correlations. There were several differences observed between male and female participants. For example, regarding the correlation between empathy and cyberbullying variables, there was a significant relationship between these two variables among female participants (r = −.09; p < .05), while there was no significant relationship among male participants (r = −.08; p > .05). As for the correlation between friendship quality and self-esteem, there was a significant relationship between these two variables among male participants (r = .17; p < .01), while there was no significant relationship among their female counterparts (r = .07; p > .05).

Table 1. Correlation matrix of male and female participants

Based on the cyberbullying tendency scores, female participants seemed to have lower scores than their male counterparts. The mean scores of female and male participants were 45.23 and 49.53, respectively. Both male and female participants had the same minimum score of 28. Even though the cyberbullying tendency among male participants was higher, high scores were also found among female participants. The standard deviations of both male and female participants’ scores were equal. This means that both data of male and female participants’ cyberbullying tendencies were homogeneous in nature. Data can be seen in more detail in .

Table 2. The descriptive statistics of cyberbullying tendency scores by gender (N = 1038)

Table 3. Between-variable correlations

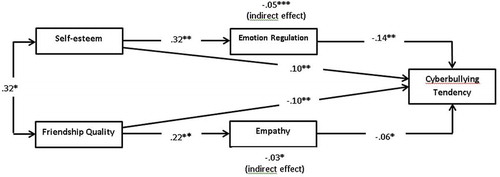

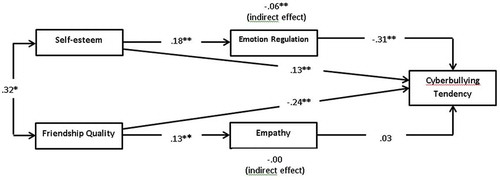

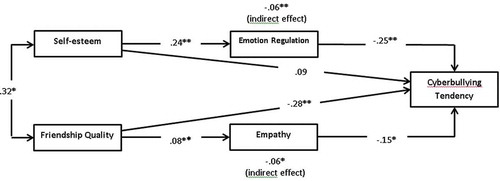

The above results were in line with that of research by Sartana and Afriyeni (Citation2017) in that men engage in cyberbullying more frequently than women. Since cyberbullying tendencies between men and women were found to be different, separate path analyses for both genders were done in this present study ().

The path analyses showed that the mechanism that worked was partial mediation, because the direct effect in the regression was still significant (). It is possible that there are still other variables that serve as mediators between friendship quality and self-esteem and cyberbullying.

The role of self-esteem in cyberbullying tendency with the mediation of emotion regulation

When gender was not taken into account, self-esteem contributed directly and positively to cyberbullying tendency (b = .10; p < .01). That is, when an individual’s self-esteem is high, his/her cyberbullying tendency is high as well. However, when emotion regulation was included as a mediator, then the contribution of self-esteem to cyberbullying as mediated by emotion regulation became negative and significant (b = −.05; p < .01). This means that an individual with higher self-esteem is more likely to have higher emotion regulation capacity as well so that his/her cyberbullying tendency would be lower, and vice versa: someone with lower self-esteem is more likely to have lower emotion regulation capacity so that his/her cyberbullying tendency would be high.

A similar tendency was found when gender was taken into account (). Self-esteem played a direct role in the cyberbullying tendency in both male (b = .13; p < .01) and female participants (b = .09; p < .01). When the emotion regulation factor was included, it did serve as a mediator between self-esteem and cyberbullying tendency in both male and female participants with the same regression coefficient (b = −.06; p < .01).

The role of friendship quality in cyberbullying tendency with the mediation of empathy

shows that friendship quality directly and negatively contributed to cyberbullying tendency (b = −.49; p < .01). This means that if the quality of friendship is good, then the cyberbullying tendency would be low. When empathy was included as mediator, the contribution of friendship quality to cyberbullying tendency was negative and significant (b = −.03; p < .05). This suggests that an individual with a higher quality of friendship is more likely to have higher empathy as well. In other words, a higher level of empathy makes the cyberbullying tendency lower. Conversely, an individual with a lower quality of friendship is likely to have lower empathy too, so that his/her cyberbullying tendency would be higher.

When gender was taken into account, friendship quality contributed negatively to cyberbullying in both male (b = −024; p < .01) and female participants (b = .28; p < .01).

However, there were differences between male and female participants in terms of indirect effects. In male participants (), empathy could not mediate the relationship between friendship quality and cyberbullying tendency (b = −.00; p > .05). Unlike their male counterparts, female participants’ (), empathy could mediate the relationship between friendship quality and cyberbullying tendency (b = −.01; p < .05). Nevertheless, the contribution of empathy as a mediator was neither great nor strong enough.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the factors that contribute to cyberbullying tendency in adolescents living in Java, which is part of Indonesia. In this study, two hypotheses were proposed, namely that self-esteem, which is mediated by emotional regulation, and friendship quality, which is mediated by empathy, are able to reduce the tendency to cyberbully.

Emotion regulation played a significant role in mediating self-esteem in reducing the cyberbullying tendency. This confirmed the first hypothesis that a high self-esteem plays a role in increasing emotion regulation capacity, so that it will reduce an individual’s cyberbullying tendency. Conversely, low self-esteem reduces the emotional regulation capacity, so that it will increase an individual’s cyberbullying tendency.

Self-esteem was found to be a personal factor that influences cyberbullying tendency (Kowalski et al., Citation2014). This finding supports Brewer and Kerslake (Citation2015) study that found that, together, self-esteem and empathy predict cyberbullying both on the perpetrators and the victims. Brewer and Kerslake (Citation2015) explained that a decreased level of self-esteem increases the tendency to become a cyberbully in adolescents. In line with this, Brighi et al. (Citation2012) suggest that cyberbullying relates to self-esteem and a feeling of loneliness due to friendship difficulties (in male adolescents) and feelings of being neglected or excluded by others (in female adolescents). The transition from childhood to adolescence is characterized by the need to build an identity in which young people put a great emphasis on autonomy and independence from parents (Santrock, Citation2012). The transition may also lead to rapid changes in the structure and the organization of their peer groups.

Research found that adolescents involved in cyberbullying, either as perpetrators or victims, showed significantly lower levels of self-esteem than those adolescents who were not (Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, Citation2012; Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2010). In contrast to these findings, Reginasari (Citation2017) found that the majority (82.6%) of a group of high self-esteem participants tended to engage in high levels of cyberbullying. Brighi et al. (Citation2012) found that the adolescent participants of their research who had moderate self-esteem were found to have an increased risk of becoming a cyberbully because they expected to get peer recognition from engaging in such behavior.

This present study was the first study done in Indonesia that revealed that emotion regulation is able to mediate the relationship between self-esteem and cyberbullying. The results of previous studies revealed that emotion regulation, as a personal factor of individual personality, has a negative relationship with adolescents’ tendencies to engage in bullying and cyberbullying behaviors (Mawardah & Adiyanti, Citation2014). It was also found in these studies that adolescents’ ability to determine the necessary steps to deal with all kinds of emotions and thoughts most greatly influenced, and could be a protective factor against, the cyberbullying tendency. This proved that the ability to manage emotions appropriately can help an individual to control himself/herself to prevent him/her from engaging in negative behaviors, especially in situations that are problematic and stressful (Mawardah & Adiyanti, Citation2014). The aspects of emotion regulation in this present study were seen from individual cognitive processes, starting with choosing an emotional situation, modifying the emotional situation, focusing attention on a particular object, and changing cognition to changing emotional responses that arise in behavior (Gross & Thompson, Citation2007).

The data showed that 91% of participants reported to have had engaged in cyberbullying. This is a quite disturbing fact since Javanese parents generally emphasize respect and harmony with elders, relatives (Geertz, Citation1983; Lestari, Citation2012), and society (Lestari, Citation2012) while being aware of individual positions and existence in the community (Suseno, Citation1997). Respect means being able to respect others, be polite, and wise. With such attitudes, adolescents are expectedly able to regulate themselves so as not to interfere with the balance of their relationships with others (Geertz, Citation1983). The results of this present study, which showed that emotion regulation played a role in mediating self-esteem in the tendency to engage in cyberbullying, indicate that there needs to be a more serious effort on the part of parents to transmit the values of respect to their children.

The next finding of this present study was that friendship quality was proven to play a role in cyberbullying through the mediation of empathy. This confirmed the second hypothesis: a higher quality of friendship plays a role in increasing empathy which in turn will reduce one’s tendency to engage in cyberbullying. Conversely, a lower friendship quality plays a role in decreasing empathy which in turn increases one’s tendency to engage in cyberbullying. This finding was in line with that of previous research that the lack of high quality friendships in adolescents gives rise to cyberbullying behavior (Healy, Citation2013; O’Moore & Minton, Citation2009). The results of this present study also support Ang and Goh (Citation2010) research that male adolescents with lower levels of empathy have higher scores on cyberbullying scales. Ang and Goh (Citation2010) said that adolescent cyberbullies are characterized with low empathic capacities.

The findings of this present study were also in accordance with Hill’s view (in Steinberg, Citation2011) about adolescent developmental processes. Hill describes adolescents’ social-cognitive development with perspective taking abilities, which include the ability to understand the feelings and behaviors of other people, which will influence their relationships later in their lives. In this present study, the ability to take the perspectives and the feelings of others was measured using the variable empathy. High levels of empathy in adolescents promote the development of responsible behavior, enhance morale, and enhance prosocial behaviors, which in turn reduce behavioral aggressiveness (Jollife & Farrington, Citation2006).

Hill (in Steinberg, 2011) also stated that adolescent development has to do with the peer relation context. Within the boundaries of this present study, context was defined as the relationship between an adolescent and his/her peers at school, especially in relation to friendship quality. The results of this present study were in line with Hill’s concept that conflict, as a perpetrator’s motive to engage in cyberbullying, is a characteristic of a low quality of friendship. The results of this present study confirmed the findings of Chow, Ruhl, and Buhrmester (Citation2013) that empathy positively related to intimacy of friendship and conflict management competencies in adolescents. Teenagers with higher levels of friendship intimacy and better conflict management competencies are more likely to have a greater number of friends, the friendship qualities of which are characterized as close relationships. Having a high quality of friendship that is mediated with empathy proved to be able to reduce one’s tendency to engage in cyberbullying.

Friendship quality in the Javanese way of life is based on harmony, which is believed as an effort to avoid conflict (Suseno, Citation1997). This attitude closely relates to empathy. Maintaining a good relationship with other people means working together, receiving and understanding each other, keeping calm, and emphasizing unity. A harmonious attitude means avoiding conflict in maintaining relationships with other people, which enables the maintenance of quality friendships and the rise of empathy (Suseno, Citation1997).

Both mediating variables in this present study proved to have a role in the tendency to engage in cyberbullying behavior. In Javanese ethics, individuals always try to maintain a balance in dealing with others (Geertz, Citation1973, Citation1983; Suseno, Citation1997). In the present study, emotion regulation and empathy as the manifestations of harmony and respect, respectively, still seem to have roles in maintaining such a balance. Therefore, if these two mediators are improved by transmitting the values of harmony and respect from parents to their adolescents, for instance, it is expected that the adolescents’ tendency to engage in cyberbullying will decrease.

In developmental psychology discussions, age has a role in determining emotional maturity. In normal conditions, the higher the adolescents’ chronological age, the more capable they should be in managing emotions (Sabatier, Carvantes, Torres, Rios, & Sanudo, Citation2017). Data from the participants of this present study showed that there were differences in the adolescents’ cyberbullying tendencies due to age (F = −.84; p < .001). There is a significant difference in the tendency to engage in cyberbullying among adolescents aged 12 to 18 years: The older their age, the lower their tendency to engage in cyberbullying (Slonje & Smith, Citation2008).

Differences in cyberbullying tendencies due to school locations

Based on the data analysis results, the difference coefficient of cyberbullying tendency in different school locations was significant (F = 4.98; p < .001). The school locations in this present study were divided into two: big cities and small cities. It can be concluded from the above figure that there was a significant difference in the tendency to engage in cyberbullying between those who attend schools in big cities and small cities, with teenagers from schools in big cities more likely to engage in cyberbullying. This was possibly due to the higher accessibility of the internet in big cities than in small cities. Another possibility was that the principles of harmony and respect are still more strongly followed by people living in communal communities and are more common in small cities than in big cities.

Conclusions

Self-esteem can predict the likeliness to engage in cyberbullying only when it was mediated by emotion regulation. Friendship quality was a predictor of cyberbullying tendency both in a direct fashion and mediated by empathy. Empathy partially served as a mediator, i.e. in female adolescents group only, and the function of empathy as a mediator was also neither great nor strong enough.

The older the adolescents’ age, the more likely they were to engage in cyberbullying. Teenagers who went to school in big cities showed a higher tendency to engage in cyberbullying.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria Goretti Adiyanti

Maria Goretti Adiyanti: a lecturer in Developmental Psychology and Child Clinical Psychology at the Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Gadjah Mada. The focus of her research is on social development; child and adolescent problems.

Antonita Ardian Nugraheni

Antonita Ardian Nugraheni: has a master degree in psychology and is interested in adolescent problems. She is currently a guidance and counseling teacher at SMA Kolese de Britto in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Redita Yuliawanti

Redita Yuliawanti: has a master degree in psychology and focuses on adolescent problems. She is currently a guidance and counseling teacher at SMA 6 Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Laras Bethari Ragasukmasuci

Laras Bethari Ragasukmasuci: has a master degree in psychology and focuses on adolescent problems. She was a guidance and counseling teacher at a high school in Bandung, Indonesia.

Meyrantika Maharani

Meyrantika Maharani: a graduate of the undergraduate program of the Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Gadjah Mada. She has been involved in many studies in Developmental Psychology with senior researchers.

References

- Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30(1), 47–87.

- Ang, R., & Goh, D. H. (2010). Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 41, 387–397.

- Barlett, C., & Coyne, S. M. (2014). A meta-analysis of sex differences in cyber-bullying behavior: The moderating role of age. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 5.

- Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1.

- Baym, N. K. (2010). Personal connections in the digital age. Malden USA: Polity Press.

- Brewer, G., & Kerslake, J. (2015). Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy, and loneliness. Journal of Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 255–260.

- Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Melotti, G., Galli, S., Maria, M., & Genta, L. (2012). Predictors of victimisation across direct bullying, indirect bullying and cyberbullying. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17(3–4), 375–388.

- Chen, L., Ho, S. S., & Lwin, M. O. (2016). A meta-analysis of factors predicting cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: From the social cognitive and media effects approach. New Media and Society, 1–20. doi:10.1177/1461444816634037

- Chow, C. M., Ruhl, H., & Buhrmester, D. (2013). The mediating role of interpersonal competence between adolescents’ empathy and friendship quality: A dyadic approach. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 191–200.

- Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem. San Fransisco: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Davis, M. H. (1996). Empathy: A social psychological approach. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York: Basic Books.

- Geertz, H. (1983). Keluarga Jawa. Jakarta: Grafiti Press.

- Gomez, T., Quiñones-Camacho, L., & Davis, E. L. (2018). Building a sense of self: The link between emotion regulation and self-esteem in young adults. Undergraduate Research Journal, 12(1), 37–49.

- Gross, J. J., & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3–24). New York: Guilford Press.

- Healy, F. (2013). Cyberbullying and its relationship with self esteem and quality of friendship amongst adolescent females in Ireland (Master’s Thesis). Dubli n Business School, Dublin, Irlandia. Retrieved from https://www.google.co.id/?gws_rd=cr,ssl&ei=edr6WN7SIcn9vASms7xY#

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2008). Cyberbullying: An explanatory analysis of factor related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behavior, 29(2), 129–156.

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2010). Cyberbullying and self-esteem. Journal of School Health, 80(12), 614–621.

- Huffman, A. H., Whetten, J., & Huffman, W. H. (2013). Using technology in higher education: The influence of gender roles on technology self-efficacy. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1779–1786.

- Jollife, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Examining the relationship between low empathy and bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 6.

- Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 1–65. doi:10.1037/a.0035618

- Kowalski, R. M., & Limber, S. P. (2007). Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 22–30.

- Kowalski, R. M., Limber, S. P., & Agatston, P. W. (2012). Cyber bullying, bullying in the digital age (2nd ed.). USA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Kristinawati, P. (2016). Gambaran Kejadian Bullying di Siswa dan Siswi Sekolah Menengah Pertama di Jawa Tengah Tahun 2016. Ejournal, 1(1), 121–136.

- Krumbholz-Schultze, A., & Scheithauer, H. (2009). Social-behavioral correlates of cyberbullying in a German student sample. Journal of Psychology, 217(4), 224–226.

- Lazuras, L., Barkoukis, V., Ourda, D., & Tsorbatzoud, H. (2013). A process model of cyberbullying in adolescence. Computer in Human Behavior, 29, 881–887.

- Lestari, S. (2012). Psikologi keluarga: penanaman nilai dan penanganan konflik keluarga. Jakarta: Kencana Prenada Media Group.

- Lestari, S., Faturochman, Adiyanti, M. G., & Walgito, B. (2013). The concept of harmony in Javanese society. Anima, Indonesian Psychology Journal, 29(1), 24–37.

- Mawardah, M., & Adiyanti, M. G. (2014). Regulasi emosi dan kelompok teman sebaya pelaku cyberbullying. Jurnal Psikologi, 41(1), 60–73.

- Menesini, E., & Nocentini, A. (2009). Cyberbullying definition and measurement: Some critical considerations. Journal of Psychology, 217(4), 230–232.

- Menesini, E., Nocentini, A., Palladino, B. E., Frisén, A., Berne, S., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Smith, P. K. (2012). Cyberbullying definition among adolescents: A comparison across six European countries. Cyber Psychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 15(9), 455–463.

- Navarro, R., Yubero, S., & Larranaga, E. (2016). Cyberbullying across the Globe. Gender, family and mental health. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN: 978-3-319-25550-7.

- Nixon, C. L. (2014). Current perspectives: The impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 5, 143–158.

- O’Moore, M., & Minton, S. J. (2009). Cyber-bullying: The Irish experience. In C. Q. S. Tawse (Ed.), Handbook of aggressive behaviour research (pp. 269–292). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- Olweus, D. (2010). Understanding and researching bullying: Some critical issues. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. Espelage (Eds.), The handbook of school bullying: An international perspective (pp. 9–33). New York: Routledge.

- Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 611–621.

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2012). Cyberbullying: An update and synthesis. In J. W. Patchin & S. Hinduja (Eds.), Cyberbullying prevention and response (pp. 12–35). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2010). Cyberbullying and self esteem. Journal of School Health, 80, 614–621.

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2011). Traditional and nontraditional bullying among youth: A test of general strain theory. Journal of Youth and Society, 43(2), 727–751.

- Perren, S., & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2012). Cyberbullying and traditional bullying in adolescence: Differential roles of moral disengagement, moral emotions, and moral values. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(2), 195–209.

- Pornari, C. D., & Wood, J. (2010). Peer and cyber aggression in secondary school students: The role of moral disengagement, hostile attribution bias, and outcome expectancies. Aggressive Behaviour, 36, 81–94.

- Quarshie, O. H. (2009). The impact of computer technology on the development of children in Ghana. Journal of Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Sciences, 3(5), 132–140.

- Rahayu, F. S. (2012). Cyberbullying sebagai dampak negatif penggunaan teknologi informasi. Journal of Information System Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta, 8(1), 22–30.

- Ramdhani, N. (2016). Emosi moral dan empati pada pelaku perundungan-siber. Jurnal Psikologi, 43(1), 66–80.

- Redekopp, R., & Kalanda, K. (2014). Internet use: A study of preservice education students in Lesotho and Canada. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 182, 529–534.

- Reginasari, A. (2017). Peran harga diri pada hubungan antara persepsi terhadap mediasi orangtua dan perundungan-siber. (Tesis Magister Psikologi). Tidak dipublikasikan. Universitas Gadjah Mada.

- Ryckman, R. M. (2008). Theories of Personality (9nd ed.). USA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Sabatier, C., Carvantes, D. R., Torres, M. M., Rios, O. H. D., & Sanudo, J. P. (2017). Emotion regulation in children and adolescents: Concepts, processes and influences. Psicologia Desde El Caribe, 34(1), 76–90.

- Safaria, T. (2015). Are daily spiritual experiences, self-esteem, and family harmony predictors of cyberbullying among high school student? International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology, 4(3), 23–33.

- Safaria, T. (2016). Prevalence and impact of cyberbullying in a sample of Indonesian junior high school students. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 15(1), 82–91.

- Safaria, T., Tentama, F., & Suyono, H. (2016). Cyberbully, cybervictim, and forgiveness among indonesian high school students. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 15(3), 40–48.

- Santrock, J. W. (2012). Perkembangan Masa Hidup Edisi ketigabelas Jilid 1 [Life-span Development Fourteenth Edition]. Translated by B. Widyasinta. New York: McGraw-Hill International Edition.

- Sartana, & Afriyeni, N. (2017). Perundungan maya (cyber bullying) pada remaja awal. Jurnal Psikologi Insight, 1(1), 25–39.

- Slonje, R., & Smith, P. K. (2008). Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49(2), 147–154.

- Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatri, 49(4), 376–385.

- Steffgen, G., König, A., Pfetsch, J., & Melzer, A. (2011). Are cyberbullies less empathic? Adolescents’ cyberbullying behavior and empathic responsiveness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 4(11), 643–648.

- Steinberg, L. (2011). Adolescence (6th ed.). New York: Mc Graw-Hill.

- Sticca, F., & Perren, S. (2012). Is cyberbullying worse than traditional bullying? examining the differential roles of medium, publicity, and anonimity for the perceived severity of bullying. Journal of Youth Adolescence. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9867-3

- Sticca, F., & Perren, S. (2013). Is cyberbullying worse than traditional bullying? Examining the differential roles of medium, publicity, and anonymity for the perceived severity of bullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(5), 739–750.

- Suseno, F. M. (1997). Javanese ethics and world view. In The Javanese idea of the good life. Jakarta, Indonesia: Penerbit Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

- Uba, I., Yaacoob, S. N., Juhari, R., & Talib, M. A. (2010). Effect of self-esteem on the relationship between depresion and bullying among teenagers in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 6(12), 77–85.

- Vandebosch, H., & Cleemput, K. V. (2008). Defining cyberbullying: A qualitative research into the perceptions of youngsters. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 11(4), 449–503.

- Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2012). Predicting adolescent perpetration in cyberbullying: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Psicothema, 24(4), 614–620.

- William, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 516–521.

- Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2004). Online aggressor/targets, aggressors, and targets: A comparison of associated youth characteristics. Journal of Child Psychollogy and Psychiatry, 45(7), 1308–1316.