?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Since peer influence is a powerful explanation for adolescent behaviour, few studies examine its effect on adolescent’s community sentiment. In this study, we measure Taiwanese adolescents’ attachment levels in their local community and its susceptibility to peer influence. We first identify adolescents’ close friends as network neighbours and then distinguish the effects of these neighbours’ community attachment from adolescents’ subjective experiences in. We then create four explanatory variables to examine their effects on community attachment. These variables are further measured at the individual level and the local respectively since we argue that adolescents would be influenced by their close friends to form their values and behaviours. The data collection is based on a Taiwanese nationwide in-school adolescent survey in 2015 with 1062 cases. The results show that social network analysis helps explain personal community attachment mainly from local level of friendship network structure and support the theory of peer influence.

Introduction

In the field of community studies, the concept of community attachment has been applied broadly to understand the depth of people’s cognitive or affective connections to each other and to their community (c.f. Brehm, Eisenhauer, & Krannich, Citation2006; Crowe, Citation2010; O’Brien & Hassinger, Citation1992; Stinner, Van Loon, Chung, & Byun, Citation1990; Theodori, Citation2004; Theodori & Theodori, Citation2015). Kasarda and Janowitz (Citation1974, p. 328) pointed out that the strong or weak community attachment is modified dynamically depended on the ‘complex system of friendship, kinship, and associational networks’ at local community. Scholars, therefore, are interested in looking for variables which can explain why and how individuals create an awareness of community attachment (e.g. Anton & Lawrence, Citation2014). In this line of research, we are interested in understanding the depth of adolescents’ community attachment and the extent to which their peer group influence their feelings of community. More specifically, we see adolescents’ peer group as tight and direct ties nested in class networks and its importance of influence to adolescent’s community attachment is less known in the literature. To fill the research gap, this research focuses on the study of adolescents’ community attachment and the extent to which friends’ influence on it through the lens of multilevel network structure analysis.

According to the research purpose above, we phrase our research question as ‘Does a subnetwork of friendship provide a pathway that links an adolescent’s community attachment?’ We try to elaborately examine adolescents’ close friendship networks and their influence in the context of social setting. We first construct the conceptualization and operationalization of community attachment as our outcome variable. This index of community attachment consists of how adolescents concern, value, trust, and interact with local community. It presents multiple dimensions of peoples’ linkage with the place based upon the seminal work done by McMillan and Chavis (Citation1986). Following the suggestion in the literature, we create four main explanatory variables to examine their effects on community attachment, including neighbourhood relations, social engagement, social-friendliness, and social anxiety. These variables are further measured at two levels of unit, the individual level and the local level (subgroup of friends) since we argue that adolescents would be influenced by their close group of friends to shape their depth of community attachment. To examine this friendship effect on adolescent’s community attachment, in the following sections, we will discuss the implications of community attachment for adolescents and the influence of social networks on adolescents. We will then provide an empirical study to understand the mechanisms of adolescent’s community attachment formation by hierarchical linear models and present our conclusion in the last section.

The implication of community attachment

Meaning is imbedded in particular spaces, deemed important through day-to-day cultural interaction and socialization. Social scientists use the term of community attachment to better understand people’s daily interactions in their locality and meanings attached on it (e.g. Stephenson, Citation2010; Wise, Citation2015). The concept of community is shaped through a group of people and their social connection (Wilkinson, Citation1972). Community as a place in which individuals live is an important social setting for individuals to create memories, ideas, feelings, attitudes, values, and even their self-identifications. According to the perspective of social identity theory, ‘the process of locating oneself within a system of social categories’ shows the individual need of belonging to certain social groups with emotional attachment and self-identification (Pretty, Citation2002, p. 186). Hence, community attachment is used to capture the community experiences and relationships packaged as place identity to appeal to the local residents (Taylor & Spencer, Citation2004).

Community attachment is also composed by many other factors, like influence, integration and fulfilment of needs, and emotional connection (McMillan & Chavis, Citation1986, p. 9–14). Among these dimensions of community attachment, influence is one of the significant factors emphasized in this study. Influence refers to group cohesiveness and conformity on members, with which collective behaviours and attitudes could be accepted and understood by other members (Byrne & Wong, Citation1962). Therefore, community attachment is synthesized concept to be used as a status of one’s being involved in the community which shapes members’ social linkage.

Community attachment is important for local residents’ social linkage; community researchers have put their efforts into studying what factors foster community attachment. And, for the socialization of youth, we fully realize that individual experience of community should be understood in social context during adolescence (e.g. Langager & Spencer-Cavaliere, Citation2015). Social context is conceptualized as friendship network and we are interested in how it shapes youths’ community attachment. However, most research focuses on adults and their experience of forming the sense of community attachment at individual level analysis (e.g. Brodsky, O’Campo, & Aronson, Citation1999; Cope, Currit, Flaherty, & Brown, Citation2016; Jason, Stevens, & Daphna, Citation2015; Mahmoudi, Citation2016; Mannarini, Rochira, & Cosimo, Citation2012; Nowell & Boyd, Citation2014; Perkins, Hughey, & Speer, Citation2002; Talò, Mannarini, & Rochira, Citation2014; Theodori, Citation2018). Few of studies of community attachment track back to the experience of adolescence during that period adolescents start to understand their living surroundings (Cheung, Cheung, & Hue, Citation2017; Cicognani, Martinengo, Albanesi, De Piccoli, & Rollero, Citation2014; McLaughlin, Shoff, & Demi, Citation2014; Petrin, Farmer, Meece, & Byun, Citation2011). How did adolescents be involved in their local community which shape their values and attitudes towards their community and social linkage? Here, we see adolescents’ peer group as importance of influence to adolescent’s community attachment. And, in order to capture the extent to which adolescent’s community attachment is susceptive by their peer group, we adopt social network analysis to identify as close friends and examine the effects of these neighbours’ community attachment on adolescents’ depth of the sense of community. The theoretical argument of such peer influence is from social influence theory and introduced below.

Network dynamics and social influence

Social influence occurs when individuals change their ideas and behaviours through the process of internalization to meet the demands of significant others, a social group, or perceived authority (Kelman, Citation1958). It occurs by taking many forms in conformity, socialization, peer pressure, obedience, leadership, persuasion, sales, and marketing. The generation of social influence can be understood through at least three levels of analysis: dyad influence, group pressure, and close group observation. For dyad influence, it is based on direct interaction between two people. Power relationships in which influence occurs when a person (ego) has power (based on either identity, authority, legitimacy, or admiration) over alter to make the other (alter) accepts ego’s views as his/her own (Laumann & Knoke, Citation1987; Sandefur & Laumann, Citation1998). The basic assumption is that ‘the proximity of two actors in social networks is associated with the occurrence of interpersonal influence between the actors’ (Marsden & Friedkin, Citation1993, p. 127).

Face-to-face interaction is a typical form of influence through which information about the attitudes or behaviours of other actors is contagious. Story, Neumark-Sztainer, and French (Citation2002) adapted social cognitive theory and ecological perspective to argue that observational learning in interpersonal relationships has a substantial impact on adolescent’s choice and eating behaviours. Bond et al. (Citation2012) tracked 61 million Facebook users’ social networks and found that users’ messages influenced users’ friends’ and their friends’ political self-expression, information-seeking, and real-world voting behaviours through direct transmission that occurred between close friends with face-to-face relationships. Sandefur and Laumann (Citation1998) also contend that adolescents’ discussions with peers promote better perspective taking and more mature moral judgement. That is, adolescents made decisions more like those that their friends had made beforehand.

On the other hand, the path of social influence is also understood through group pressure. Group pressure emphasizes group cohesiveness to increase the amount of change in opinion until uniformity is achieved (Festinger, Citation1954). Festinger (Citation1954) argued that individuals’ attitudes and opinions are unavoidably engaging in the process of social comparison through informal social communication during which different attitudes and opinions are gradually converging into a shared point of view. His basic theoretical argument for the group’s influence over its members is that individuals belonging to a social entity tend to have a need to confirm their attitudes and opinions by comparing themselves to other group members. It was widely utilized to analyse the complex group dynamics of diffusing information to every individual member. Hence, it answers the question of why interpersonal agreement is essential to group cohesion by implying the existence of a correct or appropriate response among a group and securing a sense of appropriateness within each individual member.

In this study, we synthesize these two approaches of social influence but narrow our focus on close group observation on the extent to which individuals tend to change their behaviours in response to the small but more intensive interacting group. We argue that types of contacts at this meso level would be more complex than one-to-one intimacy (the micro) and direct interaction but not as structurally constrained and cohesive as group pressure (the macro) is. We address issues like network size, structure, and interaction in close group that are crucial to influence people change their opinions. In social network analysis, a person’s close group includes those having direct connection to him or her and connections among themselves, called network neighbours. The neighbourhood forms a tight subgroup of a larger network. An important assumption of neighbourhood network structure is that an actor’s neighbourhood is composed of dense, reciprocal, transitive, and strong ties. Technically speaking, ‘neighbourhood’ in SNA refers to the size of ego’s neighbourhood by including all nodes to whom ego has a connection at a path length of 1 and neighbourhoods of greater path length than 1 (i.e. egos adjacent nodes) are rarely used in social network analysis. When we use the term ‘neighbourhood’ here, we mean the one-step neighbourhood. Our goal in this article is to show that peer influence can be best understood in the context of general theories of social influence and interpersonal relationships. We provide a theoretical framework for describing how peers influence the attitudes and behaviours of adolescents. In general, social psychologists have developed theories about attitude formation and processes of change based upon interpersonal interactions through which shared attitudes and consensus are produced. Since the concept of group influence on individual attitude change is well developed and entrenched, elucidating the mechanisms of the formation and preservation of shared attitudes in groups is vital to the development of the social influence theory.

Based on the discussion above, our concrete research question is:

‘Does a subnetwork of friendship (neighbourhood) provide a pathway that links an adolescent’s community attachment?’

Method

The setting and procedure

The research setting is designed for investigating a series of questions about teenagers’ life experience, delinquency, parenting and family relationship, consumption behaviours, community relationship, the NEP measures, and friendship. In this project, Birds of a Feather Flock Together: An Investigation of Homophilies among Friendship and Antipathy in Adolescence (BAFT), we recruited the adolescent participants who were in the first year of junior high school, high school, and college. These students were asked to participate in this project for 3 years in a row for our longitudinal data collection from early adolescence to late adolescence. This project was initiated and implemented by the Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, and funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology (August 2014–July 2017). The grant proposal was reviewed and approved by the IRB on Humanities & Social Science Research, Academia Sinica (AS-IRB-HS07-104009) to protect all participants’ confidentiality.

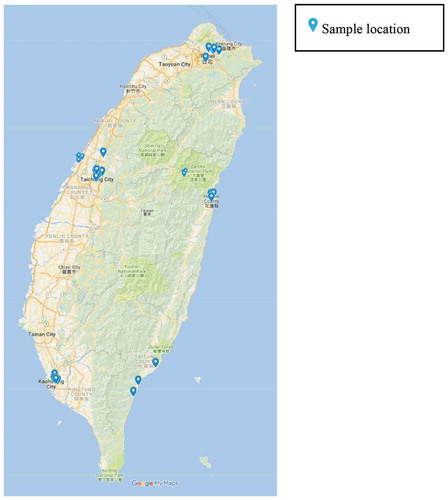

Through stratified systematic random sampling, we selected a valid sample of adolescents by covering four regions of Taiwan (Northern, Southern, Western, and Eastern) to represent the enrolled young population in Taiwan statistically (). As part of a larger longitudinal study of adolescent life experience, we focused especially on youth starting their school life in junior high school and high school. The sampling frame for the youth encompassed nationwide secondary schools in Taiwan. Meanwhile, this project is being implemented at the time of writing this article, but for this study, we only selected the first wave of data to analyse (data collection was in September, 2015). In this dataset, there were 1441 total cases. Among them, 106 cases were faked or testing accounts, and 8 respondents were from 3 classes in which their total peer participants were fewer than 10, and 7 did not answer the questions about friendship, so we did not have their network data for comparison. The data we used are a subsample from the BAFT (1320 cases) in which there were 258 cases excluded from our analysis due to their incomplete responses (the response rate was 80.454%). In the end, we had 1062 adolescent respondents nested within 48 classes and 21 schools: 11 junior high schools and 10 high schools. Sample sizes averaged about 25 students per class ().

Table 1. Frequencies and percentages for demographic characteristics of samples

Figure 1. The locations of sample schools in Taiwan

Measures

Community-related variables. We draw upon a series of community-related questions in our analysis. They include personal experience of living in local community, how respondents interact with their neighbours, and the extent to which they participated in the public affairs in the past year.

General view about community. We ask two questions to determine how respondents view their environment of community using a 5-point Likert-type scale. They are (1) ‘In general, how much do you like the surroundings nearby your home?’ and (2) ‘Is there much crime in your neighbourhood?’

Interaction with neighbours. Here we list six questions to measure the extent to which the respondents interact closely with their neighbours and how. They are (1) neighbours and I greet one another with cheers often; (2) neighbours and I chat casually often when we meet; (3) neighbours and I would talk about family lives to one another; (4) neighbours and I would look after one another whenever we are in need; (5) neighbours and I would share good stuff and information with one another; (6) I would intuitively ask neighbours if they need any help. The measurement of these items is a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from never (1) to always (5).

Views about neighbours and community. Nine items are selected to measure respondents’ views about their neighbours and feelings about the community. (1) The people here are concerned with the health of the community. (2) I value my relationships with my neighbours. (3) I trust the neighbours in the community. (4) I feel relaxed when being with neighbours. (5) I feel like the people in this community have similar values. (6) Neighbours have similar opinions about community issues for the common good. (7) I feel like I belong to this community. (8) I feel this community is like a home. (9) I would like to live in this community as long as I want to. The measurement of items above is a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Our survey purports to measure importance and engagement levels for an adolescent’s community experience. An adolescent’s engagement and experiences are captured for the three subscales by measures of community questions. These community subscales were determined through factor analysis procedures to identity three key factors in our model: community attachment as our dependent variable, neighbourhood relations, and social engagement as predictors.

Social-friendliness. ‘Social friendly’ people mean people who are willing to meet people and appear approachable to friends and acquaintances. A composite of three items to measure social-friendliness are used here: (1) to what extent you would say, ‘I am a very friendly person’; (2) to what extent you would say, ‘I like to hang out with people’; and (3) to what extent you would say, ‘I like to help people’. The response code is a 3-point Likert-type scale from 0 (no), 1 (somewhat yes), and 2 (yes). Average inter-item r = .306; standardized item Cronbach’s α = .57. The composite ranges between 0 and 6, with higher scores indicating greater tendency for acting social-friendliness.

Social anxiety. It is the fear or other negative feelings towards social situations that involve interaction with other people. People with social anxiety would feel worried and panicked in social activities, easily causing social isolation and aloneness. A composite of four items to measure social anxiety are used here: (1) to what extent you would say, ‘I feel loneliness easily’; (2) to what extent you would say, ‘I am hostile to people’; (3) to what extent you would say, ‘I have difficulties being with friends peacefully’; and (4) to what extent you would say, ‘I prefer to stay alone’. The response code is a 3-point Likert-type scale from 0 (no), 1 (somewhat yes), and 2 (yes). Average inter-item r = .261; standardized item Cronbach’s α = .56. The composite ranges between 0 and 8, with higher scores indicating greater tendency for social anxiety.

Friendships. We examine the role of friendship characteristics in moderating the relation between social influence and community attachment. Young respondents were asked to nominate their friends in various circumstances indicating instrumental ties, casual ties, and affective ties to emphasize the content of adolescent’s social interaction with their friends. Instrumental ties refer to connections adolescents make with friends in order to collect necessary information, advice, and resources to accomplish a task. We operationalize instrumental ties as ‘when looking up teamwork for a class assignment, who do you like to be with?’ Casual ties are connections that adolescents make with friends for general social interaction and are operationalized as ‘Who do you chat with during class breaks?’ Lastly, affective ties refer to people who become close friends because they provide emotional support and safety for one another. We measure this concept by asking respondents, ‘Who do you often share your private stories with?’ By measuring adolescent friendship network in these three different circumstances, we profile the youth friendship network structure within a class boundary to emphasize how instrumental, casual, and affective functions work among adolescents.

Urbanization. Theory of urbanism suggested that residents in rural communities would have higher levels of community attachment than their counterparts in urban communities (Wirth, Citation1938), but this hypothesis was not supported by later empirical studies (Theodori & Luloff, Citation2000). To examine the effects of urbanization on community attachment, we identity the different levels of urbanization for each city the sample school locates by using the ‘typology of townships in Taiwan’ of Hou, Su-Hao, Liao, Hung, and Chang (Citation2008). By considering socio-demographic variables (age, education, industrial structure, occupation, and income), six levels of development were identified in this stratification of urbanization. That is, level 1 denotes the highest level of urbanization while level 6 denotes the lowest level of urbanization. The detail descriptive statistics of samples is listed in .

Analysis

Factor analysis. A confirmatory factor analysis with an oblimin rotation of 19 Likert-type scale questions from BAFT survey was conducted on data gathered from 1062 participants under R environment (R Core Team, Citation2015). The results of an oblimin rotation of the solution are shown in . Bartlett’s test of correlation adequacy is statistically significant ( = 24,658.352, d.f. = 171). An examination of the Kaiser–Meyer Olkin measure of sampling adequacy suggested that the sample was factorable (MSA = .96). It means we have strong enough correlations between items to be able to group them together into meaningful factors. When loadings less than .30 were excluded, the analysis yielded a three-factor solution with a simple structure (factor loadings ≥ .30). As to model’s goodness of fit, comparative fix index was up to .954, which indicates strong model fit between original and reproduced correlations of factors.

Table 2. Obliquely rotated component loadings for 19 survey items

As a result, we got three factors related to 19 items. Nine items loaded onto Factor 1. It is clear from that these nine items all highly related to personal point of view about local community. This factor loads onto reported level of concerning community health and belongingness, emphasizing value, trust, and being comfortable with neighbours. Hence, this factor was labelled ‘community attachment’. Six items load onto a second factor related to respondents’ interaction with their neighbours. We labelled this factor as ‘neighbourhood relation’. Four items for Factor 3 identified the personal willingness of serving the community; we, therefore, labelled this factor as ‘community engagement’. After examining the reliability of this model, we got Cronbach’s α .982, .963, and .840 for factors of community attachment, neighbourhood relations, and social engagement, respectively.

In addition, shows the means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations of these factors: community attachment, neighbourhood relation, social engagement, social anxiety, and social-friendliness. Basically, community attachment was all significantly correlated to neighbourhood relation, social engagement, and social-friendliness. Specifically, we found that neighbourhood relation was highly significantly correlated to community attachment (r = .677, p < .001) and one’s social-friendliness was also significantly correlated to social engagement (r = .414, p < .001). On the other hand, social anxiety was negatively correlated to all other factors, indicating that social anxiety would hinder individuals from being involved in social activities, public issues, or even sense of place and belonging. In the following section, we explicitly examine the effects of these social connections on community attachment, especially focusing on the mixed effects of social values and behaviours embedded in multilevel network structure.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations of factors and variables

Multilevel network structure. Social network is the structure of connections among a set of social actors from individuals and groups, to organizations and nations, also from arts to capital, and so on. This structure of connections is seen as linking to opinions, behaviours, and information of the actors within the network. In this study, multilevel of analysis is applicable: individual level, local level, and macro level (). They had been discussed in the previous section. In , we drew the friendship network from one of our class samples to visualize different levels of network structure. The right graph is the complete network at macro level; the left graph highlights one single ego 31 to represent the individual level structure within the complete network. Last, the centre graph presents ego-centred neighbourhood seen as local level network structure. Here, we describe how variables at different levels were measured. At the individual level of analysis, we focus on ego’s friendship degree and network closeness. The former indicates the number of ties an ego linked directly to alters (friends), representing how many friends an ego had in his/her class. The latter measures how many steps an actor needs to access all alters. The purpose of network closeness is to find out the extent to which an actor is close to the centre of the whole network. In other words, when an actor has the shortest path to all alters, it has the greatest control of communication and reduces information loss by multilevel transmission (Bavelas, Citation1950).

At the meso level of analysis, we detected all direct connection of neighbours with every single ego as an ego’s neighbourhood. In social network analysis, the ‘neighbourhood’ is almost always one step, but it also includes all of the ties among all of alters to whom ego has a direct connection as shown in centre graph of . It shows in one of our class samples ego 31 had 12 friends and some of them were also friends while others were not. To examine the extent of the influence of neighbours’ attitudes and behaviours on egos, we first grouped every single ego’s neighbours as a subgroup and then calculated the average scores of their community attachment, neighbourhood relations, social engagement, social-friendliness, and social anxiety as the group mean which would be aggregated as the grand mean for each class sample. In addition, egos would have different neighbours and size of neighbourhood at instrumental, casual, and affective friendship networks; we calculated these group means, respectively, to be our predictive variables. At the macro level of analysis, we considered the level of urbanization of the city where class samples were located, the size of class samples, and the friendship network density as control variables. In short, we examined these individual, local, and macro level of variables simultaneously in hierarchical linear models to figure out their net effects on adolescents’ community attachment.

Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) analysis for community attachment. provides the results of hierarchical linear modelling of explanatory variables towards adolescent community attachment based on four models. The statistical operation and analysis are programmed and processed under the R environment with basic, igraph, lme4, and other standard R packages provided by the comprehensive R archive network (R Core Team, Citation2015). Since we consider multiple level variables and their effects on individual-level community attachment, the Model Null () presents the most basic hierarchical linear model, which is the same as a one-way ANOVA with random effects (Snijders & Bosker, Citation1999). The equation is as follows:

Table 4. Effects of network features on individual’s community attachment

where denotes adolescent community attachment

in class sample

and

represents the grand mean of community attachment across all class samples. As to

and

, the front is the random effect of the class samples while the latter is the random effect from level 1 variables. Both are assumed to have the normal distribution of variance

, but mutually independent (Pituch & Stevens, Citation2015, p. 65). This model predicts community attachment within each adolescent sample (level 1) with the intercept at level 2, the class. This model has a grand mean effect and a person effect, also known as the fully unconditional model (i.e. no level 1 or level 2 predictors are specified) or the intercept-only model. It provides several essential pieces of information that guide further applications of HLM. Specifically, the null model produces an estimate for the grand mean for community attachment across classes. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the null model was about .016, indicating that there was no significant regional effect in our research model (Hox, Moerbeek, & Rens, Citation2017). This result turns our attention to the effects of individual-level and network features within class boundary (i.e. one-way ANCOVA with random effects) more than that of the variance between classes on adolescent community attachment. Besides, we also expected that there are not individual-level variables having significantly different effects across countries (no interaction effect). It then makes sense not to consider a slopes-as-outcomes model that includes individual-level variables, local-level, and class-level variables.

After checking the results from Model Null as the basic model for further comparison with the mixed effect models, we then examine regression with mean-as-outcomes in Model 1, which means we add class level variables into the model (). First of all, as to the goodness-of-fit test, we found that the Akaike information criterion (AIC) was about 7398.1 and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was 7452.8 in Model 1, and both AIC and BIC were slightly smaller than that in Model Null. Compared with these results of goodness-of-fit test, Model 1 was better to fit our set of data. However, among the grand mean of level 2 variables, we found that only the mean level of community attachment () at class was statistically significant contributing to increase the odds of adolescent’s community attachment while the constant (

) was still significant. That is, we did not find evidence to argue that group-level attributes contribute to explaining the variance of individuals’ community attachment: the level of urbanization would not affect individuals’ community attachment, nor would the size of class or the friendship density in the class. In Theodori and Luloff (Citation2000) study, they found no evidence to support Wirth’s (Citation1938) theory of urbanism, saying residents of the more rural communities would have higher levels of community attachment than the residents of the most urban community; instead, they argued that people in the rural areas showed significantly lower level of community attachment than the urban counterparts in the case of Pennsylvania, United States of America. However, Anton and Lawrence (Citation2014) found that in Western Australia, rural residents had higher level of place identity than urban residents. In our study, the results did not support the significant association between individual community attachment and the level of urbanization for our adolescent respondents. Besides, the grand mean of variables, such as neighbourhood relations, social engagement, social-friendliness, and social anxiety, was not statistically significant to explain the variance of individual community attachment. In other words, we found group-level variables barely exhibited significant contribution on individual community attachment. According to this finding, we turned to seek measures at individual and local levels to examine what individual attributes and network features could influence adolescents’ community attachment.

Model 2 in shows the effects of individual level variables after controlling the effects of variables in Model 1. These additional variables include personal attributes and individual (ego) level network features. First, the results show the similar effects of group-level variables on adolescent community attachment even adding individual variables into the model. Then, among individual level variables, we found that the effects of personal relations with her or his neighbours (), social engagement (

), and social friendliness (

) were all positively significantly associated with individual’s level of community attachment. Besides, the level of personal social anxiety (

) was negatively significantly associated with one’s level of community attachment. In addition, there were no significant ego-network effects on community attachment. That is, the number of friends (popularity) and closeness to classmates did not significantly influence one’s feeling about community attachment. As to the goodness-of-fit test, according to the AIC and BIC results for Model 2, we found Model 2 fit the set of our data much better than prior model did.

After reviewing the effects of personal social engagement on community attachment, we further examined the influence effects from one’s subgroup of friends. We argue that such ego-centred neighbourhood in friendship network significantly contributes to one’s imagination of community attachment. The results show in the final model, Model 3 in . The explanation of Model 3 is divided by four parts. First of all, the effects of individual level variables were consistently significant to explain the variance of adolescent community attachment in the Model 2. That is, neighbourhood relations () and social engagement (

) were still statistically significant factors to influence one’s community attachment. Yet, the variable of social friendliness (

) dropped its statistical power to explain the variance of our dependent variable after controlling other explanatory factors. As to social anxiety at the individual level, it was still negatively associated with one’s community attachment.

The other three parts of explanation from the results of Model 3 are about considering ego-centred neighbours’ level of neighbourhood relations, social engagement, social friendliness, and social anxiety. And each ego’s neighbours were identified based on instrumental friendship network, casual friendship network, and affective friendship network, respectively; as a result, the size and members of ego-centred neighbourhood in these three friendship networks vary. For example, ego i in class j had alters A, B, and C as instrumental friends and maybe she had alters C, D, E, and F as casual friends, and then, she made direct connection with alters G, H, K, L, and M as affective friends. In this case, we say that the size of ego i’s neighbours in instrumental, casual, and affective friendship network were 3, 4, and 5, respectively. Then, average scores of ego-centred instrumental, casual, and affective neighbours’ neighbourhood relations, social engagement, social friendliness, and social anxiety were calculated through those identical friends from instrumental, casual, and affective friendship networks, respectively. Therefore, when we checked the influence of friends on adolescent community attachment, we found that in instrumental network influence friends’ effects of community attachment (), neighbourhood relations (

), and social-friendliness (

) significantly exist. In addition, in casual friendship network, adolescent’s community attachment was also significantly influenced by close subgroup of friends’ community attachment (

) and neighbourhood relations (

). Last, the affective friendship network exhibited its influence effect on adolescent’s community attachment through close friends’ community attachment (

) and neighbourhood relations (

) and their effects were the significantly stronger than that in instrumental and casual network influences. Is the final model best to fit the set of our data? Compared with the values of AIC and BIC from all testing models in , we found the Model 3 values are the best model examining the effects of our explanatory variables on the variance of adolescent community attachment.

Discussion

We use hierarchical linear modelling to distinguish the partial effects at individual- and meso-level, especially focusing on friends’ influence through network features. In this way, we expect to be able to answer the research question and demonstrate the extent to which friends contribute to adolescent’s community attachment. Our research models show that there was no significant effect of community urbanization on predicting the different level of adolescents’ attachment to their community. It implies that the level of adolescent’s community attachment would not be different by the level of urbanization. This finding provides an alternative opportunity for understanding the effect of social relations among residents on their sense of community, especially for youth. Although Putnam’s (Citation2000) and Theodori and Luloff (Citation2000) studies found the strength of community solidarity is different between urban and rural areas, we found there was no significant difference across the rural–urban continuum in Taiwan. We further examine the level of community-related variables at class level and find that none of them ( ~

) were statistically significant to predict individuals’ community attachment in the final model (). In other words, when we look at the grand mean of community attachment, neighbourhood relations, social engagement, social-friendliness, and social anxiety, they weakly help us to explain the variance of adolescents’ community attachment at the individual level. This finding pushes us to rethink the mechanism of social setting’s influence on shaping individual’s values and behaviours (Festinger, Citation1954; Friedkin, Citation2001). Since Festinger emphasized that group cohesion is the key factor in reaching a group’s equilibrium through social comparison, Friedkin (Citation2010) took this approach and modellized interpersonal influence by measuring the dyad relationship through every possible third party in the same network boundary to deliberate the dynamic process of social influence. Following this line of social influence approach, our model shows that the overall tendency of a larger social group’s value or attitude would not directly determine individuals’ values and we should consider the effect from the smaller group instead to test the hypothesis of social cohesion (Festinger & Thibaut, Citation1951).

In order to examine the extent to which a close group of friends influences individuals’ values or behaviours, we measured the average scores of the five community-related variables from an ego’s subgroup of friends, the neighbours in the social network structure. Furthermore, we distinguished friends with instrumental interaction from friends with affective and casual interactions based upon the content of adolescents’ social interaction with their friends. We argue that the content of friends’ interaction will have different effects on influencing their values according to social influence theory. Interestingly, in our final model, we found that friendship influence was consistently significant from different contents of interaction. That is, subgroup of friends’ community attachment and neighbourhood relations played an important role in shaping youth’s community attachment across all three types of interaction content. Although the empirical data did not support our argument that types of interaction content have different effects on influencing adolescents’ values, we found that ‘instrumental’ friends’ social engagement was significant to influence adolescents’ community attachment. This implies that friends providing necessary information, advice, and resources positively and actively function to make their peers realize the significance of a community where they reside during their adolescence so that they are able to establish and propagate the community identity (Dholakia, Bagozzi, & Pearo, Citation2004).

Last, the most powerful explanatory effects were still those variables at the individual level. Personal experiences of neighbourhood relations and social engagement were statistically significant to positively explain the level of adolescents’ community attachment. Social engagement reflected adolescents’ caring and engaging in public issues, such as helping the community, solving community problems, and synthesizing others’ needs and feelings. With social engagement, adolescents are able to do for others, an attitude of serving the community. Besides, neighbourhood relations were the daily interaction with neighbours from greeting, talking to looking after and sharing. These social activities facilitate people’s interaction and then shape the understanding of being part of this community, the basic concept of community attachment. In addition, social anxiety is the negative feelings about interaction with others; therefore, it had the negative effect on influencing adolescents’ getting involved in community activities, causing social isolation and aloneness and lack of community attachment.

In adolescence, youth have been gradually reorganizing their attachment system from focusing on the family to associating with peers. We examine the influence effect from social network structure and argue that friendship networks can inform and enrich community attachment. Specifically, we explore a framework of social network theory as a conceptual tool for detecting the path of influencing others through the network structure in which one is embedded. The results from hierarchical linear modelling show that social network analysis helps explain personal community attachment mainly from local level of friendship network structure. That is, the effect of adolescents’ subgroup of friends was statistically significant in facilitating youth’s community attachment. Our concern with the potential contribution of friendship network for understanding the formation of community attachment stems from an acknowledgement for complexity beyond the individual level of analysis. Our findings support that community attachment can be strengthened by focusing on friends’ interaction in a way that has genuine potential for influencing youth’s motivation to becoming involved in community issues in civil society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chih-Yao Chang

Chih-Yao Chang is an assistant professor at Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts in Taiwan. His research focus primarily on dynamic social network analysis and community studies. He is also interested in adolescents’ friendship network and how it shapes adolescents' patterns of behaviors. He has published his research findings on several journals, like International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, Survey Research - Method and Application, Journal of Information Society, Journal of the Community Development Society, and so on. For more information, please refer to his personal website at https://sites.google.com/site/cycusu/curriculum-vitae

Chyi-In Wu

Chyi-In Wu, a sociologist graduated from Iowa State University, he currently serve as research fellow and deputy director at Institute of sociology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. His main research interests are social network analysis, sociological methodology, information and society, and life course study.

References

- Anton, C. E., & Lawrence, C. (2014). Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 451–461.

- Bavelas, A. (1950). Communication patterns in task‐oriented groups. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 22(6), 725–730.

- Bond, R. M., Fariss, C. J., Jones, J. J., Adam, D. I., Kramer, C. M., Settle, J. E., & Fowler, J. H. (2012). A 61-Million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature, 489(7415), 295.

- Brehm, J. M., Eisenhauer, B. W., & Krannich, R. S. (2006). Community attachments as predictors of local environmental concern: The case for multiple dimensions of attachment. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(2), 142–165.

- Brodsky, A. E., O’Campo, P. J., & Aronson, R. E. (1999). PSOC in community context: Multi-level correlates of a measure of psychological sense of community in low-income, urban neighborhoods. Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 659–679.

- Byrne, D., & Wong, T. J. (1962). Racial prejudice, interpersonal attraction, and assumed dissimilarity of attitudes. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 65(4), 246–253.

- Cheung, C.-K., Cheung, H. Y., & Hue, M.-T. (2017). Educational contributions to students’ belongingness to the society, neighborhood, school and family. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(2), 226–237.

- Cicognani, E., Martinengo, L., Albanesi, C., De Piccoli, N., & Rollero, C. (2014). Sense of community in adolescents from two different territorial contexts: The moderating role of gender and age. Social Indicators Research, 119(3), 1663–1678.

- Cope, M. R., Currit, A., Flaherty, J., & Brown, R. B. (2016). Making sense of community action and voluntary participation—a multilevel test of multilevel hypotheses: Do communities act? Rural Sociology, 81(1), 3–34.

- Crowe, J. A. (2010). Community attachment and satisfaction: The role of A Community’s social network. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(5), 622–644.

- Dholakia, U. M., Bagozzi, R. P., & Pearo, L. K. (2004). A social influence model of consumer participation in network- and small-group-based virtual communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21(3), 241–263.

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140.

- Festinger, L., & Thibaut, J. (1951). Interpersonal communication in small groups. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 46(1), 92–99.

- Friedkin, N. E. (2001). Norm Formation in Social Influence Networks. Social Networks, 23(3), 167–189.

- Friedkin, N. E. (2010). The attitude-behavior linkage in behavioral cascades. Social Psychology Quarterly, 73(2), 196–213.

- Hou, P.-C., Su-Hao, T., Liao, P.-S., Hung, Y.-T., & Chang, Y.-H. (2008). The typology of townships in Taiwan: The analysis of sampling stratification of the 2005-2006 “Taiwan social change survey”. Survey Research — Method and Application, 23(1), 7–32. In Chinese.

- Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & Rens, V. D. S. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jason, L. A., Stevens, E., & Daphna, R. (2015). Development of a three‐factor psychological sense of community scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(8), 973–985.

- Kasarda, J. D., & Janowitz, M. (1974). Community attachment in mass society. American Sociological Review, 39(3), 328–339.

- Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1), 51–60.

- Langager, M. L., & Spencer-Cavaliere, N. (2015). ‘I Feel Like This is a Good Place to Be’: Children’s experiences at a community recreation centre for children living with low socioeconomic status. Children’s Geographies, 13(6), 656–676.

- Laumann, E. O., & Knoke, D. (1987). The organizational state: Social choice in national policy domains. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Mahmoudi, F. L. (2016). The value of the sense of community and neighboring. Housing, Theory and Society, 33(3), 357–376.

- Mannarini, T., Rochira, A., & Cosimo, T. (2012). How identification processes and inter‐community relationships affect sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(8), 951–967.

- Marsden, P. V., & Friedkin, N. E. (1993). Network studies of social influence. Sociological Methods & Research, 22(1), 127–151.

- McLaughlin, D. K., Shoff, C. M., & Demi, M. A. (2014). Influence of perceptions of current and future community on residential aspirations of rural youth. Rural Sociology, 79(4), 453–477.

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6–23.

- Nowell, B., & Boyd, N. M. (2014). Sense of community responsibility in community collaboratives: Advancing a theory of community as resource and responsibility. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(3–4), 229–242.

- O’Brien, D. J., & Hassinger, E. W. (1992). Community attachment among leaders in five rural communities. Rural Sociology, 57(4), 521–534.

- Perkins, D. D., Hughey, J., & Speer, P. W. (2002). Community psychology perspectives on soical capital theory and community development practice. Journal of Community Development Society, 33(1), 33–52.

- Petrin, R. A., Farmer, T. W., Meece, J. L., & Byun, S.-Y. (2011). Interpersonal competence configurations, attachment to community, and residential aspirations of rural adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(9), 1091–1105.

- Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. (2015). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences: Analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Pretty, G. M. H. (2002). Young people’s development of the community-minded self: Considering community identity, community attachment and sense of community. In A. T. Fisher, C. C. Sonn, & B. J. Bishop (Eds.), Psychological sense of community: Research, applications, and implications (pp. 183–193). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media, LLC.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and revival of american community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- R Core Team. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Sandefur, R. L., & Laumann, E. O. (1998). A paradigm for social capital. Rationality and Society, 10(4), 481–501.

- Snijders, T., & Bosker, R. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. California: Sage Publications.

- Stephenson, J. (2010). People and Place. Planning Theory & Practice, 11(1), 9–21.

- Stinner, W. F., Van Loon, M., Chung, S.-W., & Byun, Y. (1990). Community size, individual social position, and community attachment. Rural Sociology, 55(4), 494–521.

- Story, M., Neumark-Sztainer, D., & French, S. (2002). Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 102(3), S40–S51.

- Talò, C., Mannarini, T., & Rochira, A. (2014). Sense of community and community participation: A meta-analytic review. Social Indicators Research, 117(1), 1–28.

- Taylor, G., & Spencer, S. (Eds.). (2004). Social identities: A multi-disciplinary approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Theodori, A. E., & Theodori, G. L. (2015). The influences of community attachment, sense of community, and educational aspirations upon the migration intentions of rural youth in Texas. Community Development, 46(4), 380–391.

- Theodori, G. L. (2004). Community attachment, satisfaction, and action. Community Development, 35(2), 73–86.

- Theodori, G. L. (2018). Reexamining the associations among community attachment, community-oriented actions, and individual-level constraints to involvement. Community Development, 49(1), 101–115.

- Theodori, G. L., & Luloff, A. E. (2000). Urbanization and community attachment in rural areas. Society & Natural Resources, 13(5), 399–420.

- Wilkinson, K. P. (1972). A field-theory perspective for community development research. Rural Sociology, 37(1), 43–52.

- Wirth, L. (1938). Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology, 44(1), 1–24.

- Wise, N. (2015). Placing sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(7), 920–929.