ABSTRACT

This article deals with the connection between self-concept, self-care in relation to a adolescents’ risk behaviour. The work describes the connection between self-care and at risk behaviour, which influences the teenager and their behaviour. Thereafter, it focuses on the interconnection of self-concept and risk behaviour as an important element during the formation of the personality at risk behaviour. In the last part, the authors spend time on the meta-analysis of the chosen research. The self-care influences the self-concept, therefore on the basis of the identified interconnections we can speculate to what degree of development of self-care we are able to preventively and intervention affect at risk behaviour. The significant result of the research is, that the development of a self-concept in teenagers is needed in all its dimensions for the retention of some balance in life and for the achievement of the appropriate goals in the life of an individual.

Introduction

Self-care and self-concept are significant parts for optimal functioning in the physical, mental and social aspect of not only working individuals but also adolescents and other individuals. Adolescence is a difficult period in an individual´s life. This is a period in which young people are involved in risky behaviour at a higher rate compared to other stages of development (Reel, Citation2018 in: Tóthová & Žiaková, Citation2019). The important people during this time are parents, teachers, peers, and other closely-related persons. The main social group for teenagers is a family. Naturally, with a number of biological and psychological changes taking place at a given stage of development, at the same time there is a new social inclusion of the individual, which is reflected in the different expectations of society in the context of individual behaviour, changes in social roles and new reflected self-concept (Rovenská & Halachová, Citation2017). The social reliance and support from the parents have a very important influence on the growth of the child, on their comfort, and on the perception of themself. The teenager, in the interaction with their peers, starts to realize their abilities, to sense their needs, and to define themself and their goals. They try to formulate their own plans for future and find their place in society (Szobiová & A Jansová, Citation2005).

Self-concept is a term created by convictions, which are hierarchically organized, it changes over time and is influenced by other people, situations and culture (Pestana, Citation2014). The risk factors enter the person´s life when self-concept is developed inadequately, or more precisely undeveloped, which influences their next direction and action in life. Self-concept represents an important variable, which seems to be the driving force to success at school and in life. The educational system signicantly influences its improvement (H. J. Liu, Citation2009; O’Neill, Citation2015; Shavelson et al., Citation1976; Van Boxtel & A Monks, Citation1992). The concept of self includes a wide spectrum of terms and from these, each deals with a different area of ‘self’. This includes self-concept, self-image, self-esteem, self-worth, and self-efficacy (Konečná et al., Citation2007). It is about one’s own constructs, which are focused on various self-determinants of the individual. All ‘self’- constructs are important in their life and during the development of themselves. Each construct is needed for the optimal functioning of an organism as a whole. ‘Self’-concept as itself involves the past, present, and future. Individual constructs develop and change throughout a lifetime. The period of adolescence is typical for their formation. The concept of ‘I’ is a complex personal structure and its development is very sensitive especially in this period of time. The development requires mainly intense cognitive work (Langmeier & Matějček, Citation2011).

Under at risk behaviour we mean various forms of behaviours that cause negative consequences in the life of an adolescent and also on their mental functioning, which leads to damage of psycho-social health or physical health of the individual or other persons (Macek, Citation2014; Miovský et al., Citation2012).

Today, self-care is a sufficiently widespread concept addressed by many disciplines. Each of the disciplines looks at themselves from their point of view (Lovašová, Citation2016). The term Self-care integrates some of the important psychological units, which include self-knowledge, self-reliance, self-efficiency, self-confidence, individual perception and strong sense of one’s health (Cox & Steiner, Citation2013). In this concept, Self-concept consists of two other elements: self-image (self-belief or self-attitude – the result of the life experiences and feedback from others) and self-esteem (evaluation of one’s own image) (Pestana, Citation2014).

The application of self-care and self-concept as possible predictors positively influencing the risk behaviour of adolescents requires a high level of knowledge of the social workers. Supervision appears to be one of the methods that could help raise knowledge and awareness in a given field, with supervisory meetings and programmes focusing specifically on these concepts (Vaska, Citation2014).

Self-care and at risk behaviour

On the basis of various research studies, (Johnson et al., Citation2009; Pettit et al., Citation2011; Fogle, Citation2012) the systematic care of oneself is one of these processes, which eliminate the presentation of at risk behaviours and other social-pathologic phenomena.

The development of at risk behaviours is influenced not only by the lack of self-care in all its factors but also anti-social behaviours of teenagers, the influence of addictive substances, behavioural issues, risky sexual behaviours, habits and impulse disorders, substsance abuse that does not cause addiction (Čerešník & A Gatial, Citation2014; Kazdin, Citation2000; Labáth et al., Citation2001; Macek, Citation2003). The consequences, connected with the development of at risk behaviour of teenagers, are medical, mental, economical, criminal/legal, and psycho-social (Hamanová, Citation2000).

Under various influences, that range from inappropriate educational guidance all the way to traumatic life events, the individual shifts away from social norms and starts to behave inappropriately for their age, status, role, or the situation. At risk behaviour is developed, which has its origin and a way of a solution as well (Čerešník & A Gatial, Citation2014).

The basis for self-care is a conscious commitment made by the will of the individual in the activities, which allow them to achieve, to hold on to, e.g. to return to a state of physical and mental comfort (Lovaš et al., Citation2014). The natural relational framework of self-care is self-regulation. The practice of self-care can be considered an external display of self-regulation processes (Lovaš et al., Citation2014).

Self-care as a multidimensional concept creates an inevitable part of everyday life. Monk (Citation2011) divides self-care into four parts. The physical part deals with the rational way of life. The mental part is about the actions ensuring the rise in professional or private life, the emotional part deals with the relationship of the individual to themself and also to their closest people, friends and to others and the spiritual part that involves the nonmaterial world in which self-reflection is the focus.

The holistic point of view perceives self-care as actions which cover all areas of the individual´s life. Bride (Citation2007) identifies six goals of self-care, which interlock and influence all future behaviours and actions of an individual. These include the emotional, physical, mental, spiritual, professional, and social areas. The well-known model of self-care, according to (ICAA, Citation2010), that connects self-care with its individual dimensions. The given model encompasses the physical, emotional, intellectual, social, professional, spiritual and environmental areas, these influence each other from which its concluded that it is very important to take care of them all.

When a person takes care of themself in an adequate way, it provides the benefit for the individual’s improvement in potential, for social capital in society and in support of the human competency in the most effective way (Department of Health, Citation2007).

At risk behaviour increases during the period of adolescence and the actual development of self-care activities should help to decrease its effects. This kind of behaviour can lead to a negative change in physical, emotional, and mental health. The formation of at risk behaviour in teenagers and also other individuals depends on personal characteristics and environmental factors (Orosová et al., Citation2012; Punová, Citation2012). Also, the meaning of the teenager´s life can play a significant role (Šiňanská & Puškášová, Citation2014).

The model () presented in the following section focuses on at risk behaviour of teenagers. The authors of the model are Irwin and Millstein (Citation1993). They state in the model, that the biological maturing during adolescence has psycho-social consequences. The model presents two parts of the research, which are mostly studied separately. The first part is the relationships between biological development and psycho-social processes during the adolescence and the second part is the relationships of at risk behaviour and psycho-social correlates of behaviour (there belongs: the apperception of risk and the characteristic of the peer group). The impact of biological maturing is described in the four parts of psychosocial functions. It is about the cognitive extent (egocentrism, perspectives into the future), self-perception (self-esteem, tolerance, identity, physical appearance, self-sufficiency), the perception of the social environment (the parental influence, parental control, and parental support and the influence of peer group), the personal values (independence, success, affection) (Irwin & Millstein, Citation1993).

Figure 1. Diagram of the biopsychosocial model of at risk behaviour (Irwin & Millstein, Citation1993, edited by authors).

On the basis of the mentioned model, we point out that the overall self-care influences at risk behaviour of teenagers. When the elements of biological maturation are underdeveloped and the individual cannot deal with the issues in their environment, it predisposes the development of at risk behaviour. On the contrary, when the elements of biological maturation are developed sufficiently, the at risk behaviour will not increase and the biological maturation further develops according to individual elements.

Self-concept and at risk behaviour

The self-concept is more hypothetical construct than the real mental unit (Shavelson et al., Citation1976). Blatný (Citation2010) understands self-concept as a summary of perceptions and evaluating judgements that a person has about himself. Blatný et al. (Citation1993) focus on the self-concept within the framework of cognitively oriented psychology, in which it is considered as a mental representation of self. In the study of the formation of self-concept, it is necessary to focus on the general principles and factors of self-formation, and on the problems of defining the actual ‘I’ – so on the formation of the own identity (Blatný, Citation2010). Kohoutek (Citation2001, p. 173) understands self-concept as ‘the result of complex process of self-appraisal, evaluation of their own qualities in relation to other people and in relation to their own ambitions and goals.’ The initiator in the self-concept area is W. James, who distinguishes three aspects of self. I-self as a subject of spiritual activity, self-as-knower, and Me-self (Blatný & Plháková, Citation2003).

The whole self-concept is closely linked to the individual´s behaviour in the environment. The behaviour is affected to a high degree also by the individual’s perception of himself as part of the system as whole. The strengthening of one’s self-concept during the period of adolescence is an important aspect, because it has an influence on the individual´s future, on results of their education and on their life itself (Marsh & A Craven, Citation1997). Bakadorova and Raufelder (Citation2015) found that the teenagers with the higher self-concept are more motivated by comparison to others, while their peers with the lower level of self-concept are motivated more likely by support and encouragement. The period of adolescence is closely linked with the change in self-concept. ‘Self’ by itself is changing significantly (Sebastian, Citation2008). The crucial role in development of self-concept during adolescence has authority (parents, teachers, tutors, caregivers) (Rogers, Citation1959). Systematic formation of self-concept is a process, which leads to an ideal self. Besides the behaviour, ‘self’ is significantly influenced also by emotions and thoughts (Carver & Scheier, Citation2006).

People that surround an adolescent become important to them because they influence his or her personality, not because they have a specific role or hold a position of power. The conclusions, which are made by the teenager upon how the people in his or her surrounding perceive him, have the important role in how he or she will perceive himself/herself and this is actually a significant part of the self-concept formation (Bakadorova & Raufelder, Citation2015). The teenager endangers not only himself but his surroundings as well with his at risk behaviour (Kopuničová & Salonna, Citation2012).

The four basic factors, which are concerned with the teenager´s self-concept formation are:

occupation of a specific acceptable social role,

identification with this role,

reactions from others,

comparison with others (Argyle, Citation2008).

According to various authors Blatný and Plháková (Citation2003); Fialová (Citation2007); Procházka (Citation2011), self-concept consists of three basic psychological aspects.

Cognitive aspect: consists of the content and the structure of self-concept. It is a summary of all knowledge about himself, i.e. it is the content, which is in a specific way cognitively organized into a structure.

Emotional aspect: it deals with the emotional relationship to himself. For the finality of emotional relationship to self is largely important the empowerment from the surrounding environment, especially from individual’s friends and family.

Conative aspect: expresses that during the development a person becomes the main factor of mental regulation in his behaviour. This aspect is the main factor of mental regulation in behaviour (Blatný & Plháková, Citation2003; Výrost & Slaměník, Citation2008).

The authors Bharathi and Sreedevi (Citation2015) claim that when an adolescent has developed their self-concept sufficiently, he can solve any problem adequately, has a tendency to be spontaneous, creative, original and he has a high level of self-confidence. Self-concept developed in a negative way during the period of adolescence is linked with various maladaptive, behavioural and emotional problems. A low degree of self-concept can also cause problems with a loss of motivation for learning. On the other hand, adolescents with high degree of self-concept are considered to be individuals with high academic results, they tend to achieve great career opportunities, and are accepted by authorities and their peers (Bharathi & Sreedevi, Citation2015). Especially, this degree of self-concept is the subject of our interest. The goal is to point at the self-concept as an important determinant for the regulation of development of a teenager´s negative behaviour and as an important determinant of the formation of the adolescent´s personality.

Through the self-concept, the person himself comes to internal self-knowledge, to increase in stability and the positive emotional relationship to himself. Self-concept can move on the spectrum from low to high (Blatný, Citation2010). Zhan Smith, and Wethington (Citation1996) confirm that self-concept creates an important part of the whole system, which contains the connection between self-appraisal, anxiety, depression, perceived stress, and coping strategies.

From the fore-mentioned theoretical framework of this study is concluded that through function of activities, which belong to the self-care area, we influence the whole self-concept with which we contribute to lowering of adolescent´s at risk behaviour.

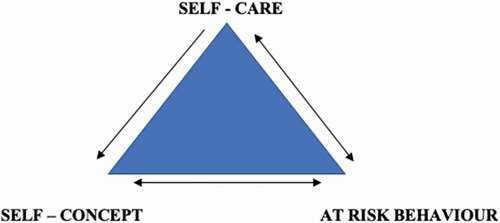

The fore-mentioned model in the , which was created by us, illustrates the relationship among these three variables. It is a mutual relationship. From that, we state that at the top is self-care as an important determinant, which with its activities it influences the whole self-concept. At risk behaviour is determined by a mutual relationship between self-care and self-concept. The conclusion of this is that when the activities of self-care are done efficiently and correctly, it positively affects the self-concept and therefore it predicts the decreasing of at risk behaviour, or more precisely the lack there of. On the contrary, when the self-care activities are done inefficiently, it predicts a higher presence of adolescents at risk behaviour.

Self-concept and the teenager´s risk behaviour – an overview of chosen research findings

The following part of the present paper focuses on the meta-analysis of research findings concerning self-concept in relation to self-care and risky behaviour during adolescence. We focused on Slovak and foreign research results.

Research findings methodology

The basic method for processing and analysing research findings was meta-analysis. The database sources we worked with in the preparation of meta-analysis were research databases SCOPUS, EBSCO, PROQUEST, WEB OF SCIENCE, PubMed, SCIENCE DIRECT, Springer Link, Wiley online Library. Other sources were monographs focused on self-concept and self-care, as well as monographs focusing on adolescent risk behaviour. Other journal sources were the Journal of Adolescent Health, the Journal of Science and Research, the Journal of Social Psychology, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Self-Care Journal. We selected the information obtained in the individual databases on the basis of the predetermined criteria, which we present below. We evaluated the suitability of the use of sources on the basis of the used professional literature, consistency in data collection or evaluation. We also assessed the suitability based on the relevance of the data in the given researched issue.

The predisposing literature from which the individual research studies accrue were focus on the researched issues – self-concept in the context of risk behaviour in adolescents. We worked with authors who focus on the target group – adolescetns with risk behaviour. The predisposing literature was only academic literature, academic journals, papers.

Keywords were searched by authors in English and Slovak languages. The keywords we worked with in the relevant databases were: self-concept, self-care, risk behaviour, adolescents, the relationship between self-care and self- risk-of-adolescents, the relationship between self-care and self-concept.

In the analysis itself, articles from relevant sources were processed within the period 1984–2018. The individual studies used reflect the development of knowledge of the self-concept and related variables over time and focus on defining the self-concept itself as a basal variable; verification of psychometric properties of methodologies identifying self-concept and related variables; as well as identifying potential relationships between self-concept and variables important for further elaboration of the topic (also in relation to risky behaviour and self-care). Totally, we worked with 19 sources. Verification of the psychometric properties of the questionnaires related to the researched issue was analysed by means of the articles and research presented in the following part of the paper. Of the methodology, the oldest source of the self-concept scale from Saraswata in 1984 was used in a meta-analysis to determine the average score in the dimensions of the self-concept. Another was the Self-Concept of School Effectivness Questionnaire from 1992 by Matějček, Vágnerová focused on school self-concept. The research used in the self-concept study of self-care were Jessor, Citation1991; Čerešník & A Gatial, Citation2014; Bharathi & Sreedevi, Citation2015; Balážová & Popelková, Citation2018.

The research studies we selected on the basis of predetermined criteria. The search criteria were: the period of adolescence, self-concept, researches which focussed on the risk behaviour in adolescents, qualitatively and quantitative researches, researches which focussed on differences and correlation in this research problem.

A meta-analysis of selected research findings

The research on self-concept in adolescents was done by authors; Bharathi and Sreedevi (Citation2015). The sample consists of 40 respondents – female gender. In the framework of the research, method was used a self-concept scale as created by author Saraswath (Citation1984). This scale helped determine the average score of individual dimensions, which form the self-concept. These dimensions are: physical, social, educational, intellectual, moral and the dimension aimed at temperament. Here the average of self-concept could be high, above-average, below-average. The higher percentage level signals above-average self-concept in individual dimensions.

Above-average level was demonstrated in the dimension of temperament (85%), in the intellectual dimension (77%), and also in the dimension focusing on physical health (60%). Approximately 47% of teenagers had high self-concept in the area of education and 57.5% had above-average of moral self-concept. The similar studies have made Ecklund (Citation2000), Dunton et al. (Citation2003), and Shivani et al. (Citation2013).

The dimension focusing on the physical element is demonstrated in female adolescents above-average because this dimension is very important to them during this life period and it helps in increasing their confidence (Harter, Citation2006). Also more than half of the respondents 52,5% had above-average level of self-concept in the social dimension. According to Kinch (Citation1968), the concept of the social dimension is based on how the individual believes in himself, how he trusts others, and how other people perceive him. As I mentioned before, the dimension focusing on temperament reached the highest score in this sample – 85%. The temperament is an aspect of one’s personality, which unveils in the mood expressions. High quality of one’s temperament is demonstrated in that, as it has a tendency to be permanent and it focuses on emotions, which have a dominant role in the life of an individual.

The growing of one’s self-concept is necessary because it is an important intermediary variable, which has a causal influence on the various desirable results, including academic success, leading a successful life, on increasing quality of their life and on decreasing the manifestation of at risk behaviour, as seen in (Marsh & A Craven, Citation1997).

Table 1. The percentage composition of particular dimensions by respondents (Marsh & A Craven, Citation1997)

From the above-stated results we can claim that the self-concept is developed sufficiently in this research sample, therefore, we conclude that the highest percentage composition demonstrates the above-average self-concept and the high self-concept.

Another study was done by authors Balážová and Popelková (Citation2018). This research had focussed on investigation of relations between individual dimensions of the quality of the relationship with one’s mother and father, with the peers in the classroom and the friends outside of the school, and the dimensions of school self-concept of high-school students. The authors utilize the previous researches (Doyle et al., Citation2015; Holt & LEWIS, 2012; Du Plessis, Citation2005; W.C. Liu, Citation2000; Wu, Citation2009). Up to this day, the school self-concept does not have a clear definition or structure. The Singapore researchers Liu and Wang dealt with the school self-concept. The authors formed a two-part conception of self-concept. One of the conceptions is focused on the school trust and the other is on school efforts. The school self-concept is influenced by various factors. Under the influence of interactions with the surrounding, it changes during lifetime, it becomes more abstract, differentiated and organized, and more dependent on the perception of other people. In the research of the school self-concept, interpersonal relationships are stronger in high school classes in comparison with the previous life stage, the classroom as a group has a more fixed system of positions and values, it gives the opportunity to confrontation during exchange of opinions, to the expression and clarification of their own attitudes in the interaction with the peers (Čapek, Citation2010; Širuček & A Širučkova, Citation2012).

Within the research, the authors speculated that the support and the depth of the relationship with both parents, friends, and classmates correlate significantly positively with school self-concept of an adolescent, and the perceived conflicts in the fore-mentioned relationships correlate negatively with school self-concept.

The importance of social relationships with friends grows, the relationships among classmates deepen, and at the same time, relationships with parents remain important. The research sample consisted of 104 adolescents. The school self-concept of an adolescent was measured by a questionnaire Academic Self-Concept Questionnaire (ASCQ). The questionnaire is consists of two 10-item subscale – the school trust and the school effort.

There were found no statistically significant connections while researching intersexual differences and school self-concept. In the observation of the support and the depth of a relationship with mother and friends, it was noted that girls scored higher than boys. On the other hand, the boys reached a higher score in conflicts with their parents and peers inside and out of school. The submitted study focused on the observation of those elements, which grow in importance significantly during the period of adolescence. If these researched relationships would be neglected, the rate of self-concept would lower and therefore the development of the at risk behaviour in adolescents would grow.

The adolescence represents a period when the importance of the school self-concept as one of the dimensions of the whole self-concept grows, it speaks about an adolescent’s relationship to the school environment and about their perception of his or her own abilities in various subjects. In , we present the intersexual differences in the interpersonal relationships.

Table 2. Intersexual differences of median values in the interpersonal relationships (Balážová, Popelková 2018)

From the previous table, we can point out the different perceptions of relationships between genders. The interpersonal relationships with parents have higher values than the relationships with peers and friends.

The following research by the author Čerešník and A Gatial (Citation2014) is focused on the school self-concept in relation to the adolescent´s at risk behaviour (as seen in ). The sample consisted of respondents ages 10 to 15 years. The number of respondents was 1704 adolescents. The used methods in the study were: Self-concept of School Effectiveness Questionnaire (Matějček & Vágnerová, Citation1992) and Prevalence of Adolescents Risk Behaviour (Dolejš & A Skopal, Citation2014). The questionnaire focusing on the school self-concept contains 48 items with 6 sub-scales (general abilities, mathematics, reading, spelling, writing, self-confidence and the overall score of school self-concept). The second method has 18 items and it is made of 3 sub-scales (abuse, delinquency, bullying and the overall score of the prevalence of at risk behaviour.

Table 3. The descriptive analysis of at risk behaviour according to the school grade (Čerešník & A Gatial, Citation2014)

On the basis of the stated table we can point out that the various values of the observed variables grow with the age of an adolescent, i.e. with the school grade. The statistical analysis of the variance showed a higher prevalence of an adolescent´s at risk behaviour with the low rate of school self-concept in contrast to adolescents with the higher rate of self-concept which confirms that when the self-concept is higher, the prevalence of at risk behaviour is lower. The author R. Jessor (Citation1991) confirms, that inadequate self-concept is one of the factors, which leads to the formation of at risk behaviour in the period of adolescence.

Within the research on a definition of self-concept exist specific differences depending on the age of an individual. The authors Roberts et al. (Citation2010) in their research aimed to reveal the age differences in the definition of self-concept and associated coping with traps that form at risk behaviour in the specific age periods. The sample did not consist of only adolescents but also other age groups.

The respondents, who belonged to the period of adolescence showed a lower range of definition in self-concept than the respondents in higher development periods. The authors concluded that even according to previous research the adolescent respondents have higher tendency to self-doubt, they are unsure of their own decisions, opinions, their abilities, and skills. Due to uncertainty in themselves and their own judgements, these persons are often dependent on their environment and can be also easily influenced by the external factors, which can explain formation of at risk behaviour in their lives.

The psychologists Smith et al. (Citation1996) indicate a bigger inclination to passive management of at risk behaviour in relation to the lower level of self-concept, and Vice versa a higher level of self-concept predicts more active coping.

The cleared self-concept is also connected with the internal placement of influence and a person that’s set like this is convinced that he can affect, change and even adapt the situation to his needs. In , we present the review of relevant self-concept research studies.

Table 4. Review of self-concept research studies

Discussion

Based on the above research findings, we will focus on the comparison of the results of our meta-analysis with the results of other authors who deal with the research. In the discussion, we focus mainly on the school self-concept, which is studied especially in adolescents.

McCaleb and Edgil (Citation1994) conducted research that focused on self-concept and self-care activities leading to adolescent health. The purpose of this descriptive study was to find out what self-care activities are present in adolescents and to identify any relationship between self-service activities, self-concept and selected factors. The main methodology was Orem’s model of self-care and developmental theory. The sample consisted of 160 adolescents aged 15 to 16 years. The findings of this investigation have shown a match between self-concept and self-care. The research presented in our meta-analysis by Bharathi and Sreedevi in 2015 also confirmed the presence of a self-concept in the sample, with the highest presence being recorded in the adolescent temperament dimension. The research further supported the impact of the socio-cultural characteristics of self-care. The implications of the study include the need to continue the research efforts that describe, explain, and predict factors that influence childcare behaviour in the adolescent population.

In 2001, Stewart conducted self-care research in the United States – an overview of the risks associated with the adolescence period has shown that low self-care causes an increase in risky behaviours for example. substance abuse, truancy, increased negative influence of peers. The research was conducted in adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. The research also took into account the ecological perspective, which was to examine the risks associated with widespread self-care among adolescents in the USA (Stewart, Citation2001). The research carried out investigated: a) the impact of the development of adolescents on the risks of self-care, b) the occurrence of problematic behaviour in the environment of adolescents, c) the results of research concerning risk and protective factors in the care of adolescents. A 2014 survey by Čerešník confirmed an increased presence in adolescents aged 15–16, these were pupils attending the 9th grade, and another risk manifestation of behaviour that appeared to an increased extent was delinquency at that age. It was increasingly present in the 8th and 9th grade pupils.

Another study by Masoumi and Shahhosseini (Citation2017) aims to explore the challenges of self-care in adolescents. The methodology used in this study was content analysis of documents searched through Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Web of Science, Scientific Information Database and Scopus. These databases aimed to obtain documents published between 1994 and 2016. The search criteria were contributions in English from authors who search about self-care about adolescents. The results of the study showed that adolescents confront cultural (beliefs, knowledge), socio-economic (family, health care providers, peers, social support, economic status) and personal challenges in self-care (mental health, gender, ethnicity). The study concludes that self-care behaviour in adolescents is influenced by biological, psychological, economic and social factors. It is a multifactorial process, and then adolescents should have enough knowledge about adolescents ‘health and also learn to perceive the role of culture in adolescents’ self-care behaviours. (Masoumi, Shahhosseini, 2017)

Based on the recommendations of Nevoralová and A Čablová (Citation2012), the following self-cognition abilities contribute to the development of self-concept and self-conception: critical thinking, problem solving, decision-making, goal setting, self-reflection, self-evaluation, planning, control, flexibility, creative thinking. These are certain metacognitive processes that relate to a mature personality which are capable of accepting himself and human creature.

Conclusion

On the basis of the stated theoretical and practical scope of this study, we can point out, that the relations between self-concept, self-care and at risk behaviour does exist. The relation between self-care and self-concept is close as both have a positive effect on the prediction of formation of at risk behaviour. When these two variables are developed insufficiently, it affects the formation of at risk behaviour. The development of these concepts is important not only in the period of adolescence, but it’s also important to pay attention to them throughout the whole lifespan. For further research the focus is needed on the development of self-concept variable in connection to self-care in adolescents as the basis of development of the whole personality and in order to prevent negative phenomena in life.

The variables of self-care and here linked self-concept are related to parenting which adolescent gets in his or her family, therefore it is needed to observe relationships among the family members and also research the family type through the variables in specific parts of self-care. Everything that goes on around an adolescent and everything that has an impact on his or her behaviour and actions are reflected in the whole component of self-care and therefore also in self-concept, from which it’s possible to develop or reduce at risk behaviour.

Among the options, which could help the growth of both components of self-care and self-concept would belong intervention programs, consequently, also the support of young people to deal with the self-development, preventative programs for the prevention of formation of at risk behaviour.

The starting point for the field of social work in the presented issue is based on the possibility to focus on the sphere of interconnection of self-concept with self-care in adolescents. An appropriate and effective method would be a programme aimed at intervention and prevention of risky behaviour through the use of self-care activities. According to Halachová (Citation2016), self-care is an inevitable basis of good practice in the whole sphere of social work in both theoretical and empirical terms. In the application of social work in the examined issue, it is important to focus on school social work as one of the possibilities of working with risky young people, where self-care would play an important role here (Šiňanská, Citation2015).

The social worker through his positive influence on the personality of the individual ensures such mechanisms that replace his original inadequate behavioural patterns to those that are adequate and recognized by society (Brnula, Citation2012).

Availability of data and material

Not applicable

Disclosure statement

We have no confict of interest

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Vladimír Lichner

Mgr. Vladimír Lichner, PhD. - is an assistant professor and works at the Department of Social Work at Faculty of Arts, Pavol Jozef Šafarik University in Košice. He is researching self-care, risk-behaviour. Pedagogically focuses on theoretical, methodological and statistical aspect of social work science and also socio-pathological phenomena of different target group of social work.

Františka Petriková

Mgr. Františka Petriková - works as an internal doctoral student at the Department of Social Work at Faculty of Arts, Pavol Jozef Šafarik University in Košice. In his publication activities are devoted to self-care with a focus on reducing risk behaviour in various target group of social work.

Eva Žiaková

Prof. PhDr. Eva Žiaková, CSc. - works as a head of the Department of Social Work the the Faculty of Arts, Pavol Jozef Safarik University in Košice since 2008. In pedagogical activities focuses on psychological aspects of social work; in scietific research activities at the issue of loneliness in connection with oncological diseases, addictions and causes behavioral disorders of high-risk clients. She is a member of the committee of the Association of Social Educators work in Slovakia; member of the group within the Vega grant agency. She is also a member scientific councils as well as a member of the commission for the award of PhD. degrees in the field Social Work at Slovak universities.

References

- Argyle, M. (2008) Spoločenské stretnutia: Príspevky k sociálnej interakcii. Aldine Transaction.

- Bakadorova, O., & Raufelder, D. (2015). Perception of teachers and peers during adolescence: Does school self-concept matter? Results of a qualitative study. Learning and Individual Differences, 43(2), 218–225.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.035

- Balážová, M., & Popelková, M. (2018). Školské sebapoňatie a kvalita interpersonálnych vzťahov adolescenta. Psychologie a její kontexty, 9(1), 29–40. ISSN 1805 - 9023.

- Bharathi, T. A., & Sreedevi, P. (2015). A study on the self-concept of adolescence. International Journal of Science and Research, 5(10), 3219–7064. ISSN 3219 - 7064.

- Blatný, M. (2001). Sebepojetí v osobnostním kontextu. Masarykova univerzita v Brně. ISBN 80-2102-747–9

- Blatný, M., Dosedlová, J., Kebza, V. & Šolcová, I. (2005). Psychosociální souvislosti osobní pohody. Brno: Masarykova univerzita a Nakladatelství MSD. ISBN 80-86633-35–7.

- Blatný, M. (2010). Psychologie osobnosti. Grada. ISBN 978-80-2473-434–7.

- Blatný, M., Osecká, L., & Macek, P. (1993). Sebepojetí v současné kognitivní a sociální psychologii. Československá Psychologie, 36(6), 444–454. ISSN 009 - 062X.0009-062–X

- Blatný, M., & Plháková, A. (2003). Temperament, inteligence, sebepojetí. Sdružení SCAN Tišňov. ISBN 80-8662-00-5–0

- Bride, B. E. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 52(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/52.1.63

- Brnula, P. (2012). Sociálna práca. Dejiny, teórie a metódy. Bratislava: IRIS. ISBN 978-80-555-0952–5.

- Čapek, R. (2010). Třídní klíma a školní klíma. Grada. ISBN 978-80-2472-74-2–4

- Carver, C. H. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2006). Psychológia osobnosti. Osiris.

- Čerešník, M., & A Gatial, V. (2014). Rizikové správanie a vybrané osobnostné premenné dospievajúcich v systéme nižšieho sekundárneho vzdelávanie. UKF. ISBN 978-80-558-0658–7

- Cox, K., & Steiner, S. (2013). Self-care in social work. a guide for practitioners,supervisors, and administrators. NASW Press. ISBN 978-0-87101-444–3

- Department of Health. (2007). Research evidence on the effectiveness of self care support.

- Dolejš, M., & A Skopal, O. (2014). Analýza psychodiagnostických nástrojů identifikujících osobnostní rysy související s rizikovým chováním adolescentů. Unpublished raw data.

- Doyle, A. B., Markiewicz, D., Brendgen, M., Lieberman, M., & Voss, K. (2015). Child attachment security and self-concept: Associations with mother and father attachment style and marital quality. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46(3), 514–539. ISSN 0272 - 930X

- Du Plessis, A. B. (2005). The academic self-concept of learners with hearing impairment in two south african public school contexts: Special and full-service inclusion schools. University of Pretoria.

- Dunton, G., Schneider, J. M., & Cooper, D. M. (2003). Physical self-concept in adolescent females: Behavioral and physiological correlates. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 7(3), 360–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2003.10609104

- Ecklund, T. (2000). Social physique anxiety and physical activity among adolescents. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 9(3), 139–142. ISSN 1089 - 5701

- Fialová, L. (2007). Kvalita života, sport a tělesné „já“. In Václav, H., Tilinger, P. Sborník materiálu z výzkumného záměru: Psychosociální funkce pohybových aktivit jako součást kvality života dospělých. FTVS UK. ISBN 80-85931-79–6.

- Fogle, G. E., & Pettijohn, T. F. (2012). Stress and health habits in college students. Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 2(2), 61–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4236/ojmp.2013.22010

- Halachová, M. (2016). Self-Care v sociálnej práci. Grant Journal, 5(2), 13–15. ISSN 1805-0638.

- Halachová, M., & Rovenská, D. (2017). Virtuálne a reálne prostredie dospievajúceho. UPJŠ v Košiciach. ISBN 978-80-8152-532–2.

- Hamanová, J. (2000). Rizikové chování v dospívaní. FreeTeens Press. ISBN 978-80-7387-793–4

- Harter, S. (2006). The development of self-esteem. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. ISBN 978-1-53610-294–9.

- International Council of Active Aging. (2010). Seven dimensions of active aging [online]. ICAA. www.icaa.cc

- Irwin, C. H. E., & Millstein, S. G. (1993). Correlates and predictors of risk-taking behavior during adolescence. In L. W. Lipsitt & L. Mitnick (Eds.), Self-regulatory behavior and risk taking: Causes and conseguences (pp. 3–21). Ablex Publishing Corporation. ISBN: 0–89391–818–0

- Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12(8), 597–605. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(91)90007-K

- Johnson, J. L., Lauck, S., & Ratner, P. A. (2009). Self-care behaviors and factors associated with patient outcomes following same - Day discharge percutaneous coronary intervention. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 8(3),190–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.12.002

- Kazdin, A. E. (2000). Treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. The Dorsey Press. ISBN 054-798–5541

- Kinch, J. W. (1968). Experiments on factors related to Self-concept. Journal of Social Psychology, 74(2), 251–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1968.9924852

- Kohoutek, R. (2001). Poznávaní a utváření osobnosti. CERM s.r.o. ISBN 80-7204-200–9

- Konečná, V. & Tyrlík, M., (2007). Sebepojetí rozumově nadaných dětí. In Československá Psychologie, 51(2), 105–116. ISSN 0009 - 062X 0009-062–X

- Kopuničová, V., & Salonna, F. (2012). Reziliencia a rizikové správanie pubescentov. In Orosová, O., Janovská, A., Kopuničová, V. a M. Vaňová. Základy prevencie užívania drog a problematického používania internetu v školskej praxi. Košice: Filozofická fakulta UPJŠ v Košiciach. ISBN 978-80-7097-964-8.

- Labáth, V., & Ambrózová, A., (2001). Riziková mládež. Slon. ISBN 80-85850-66–4.

- Langmeier, J., & Matějček, Z. (2011). Psychická deprivace v dětství. Karolínum. ISBN 978-80-2461-98-3–5

- Liu, H. J. (2009). Exploring changes in academic self-concept in ability-grouped english classes. Chang Gung. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(2), 411–432. ISSN 2321 - 2799.

- Liu, W. C. (2000). A longitudinal study of academic self-concept in a streamed setting: home environment and classroom climate factors. University of Nottingham. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X42239

- Liu, W. C., & Wang, C. K. J. (2005). Academic self-concept: A cross-sectional study of grade and gender differences in a Singapore secondary school. Asia Pacific Education Review, 6(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03024964

- Lovaš, L., Ráczová, B., Hricová, M.,Mesárošová, M., & Holevová, B.(2014). Psychologické kontexty starostlivosti o seba. Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach, Filozofická fakulta. ISBN 978-8081-521-96–6.

- Lovašová, S. (2016). Sociálna práca: Formy, postupy a metódy. UPJŠ v Košiciach. ISBN 978-80-8152-386–1.

- Macek, P. (2003). Adolescence. Portál. ISBN 80-717-874–77

- Macek, P. (2014). Rizikové a antisociálne správanie v adolescencii. Grada. ISBN 978-80-247-4042–3

- Marsh, H. W., & A Craven, R. (1997). Academic self-concept: Beyond the dustbowl. G. Phye (Ed.), Contemporary Educational Psychology, 29(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-476X(03)00034-1

- Masoumi, M., & Shahhosseini, Z. (2017). Self-care challenges in adolescents: A comprehensive literature review. PubMed, 31(2), 2–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2016-0152

- Matějček, Z., & Vágnerová, M. (1992). Dotazník sebepojetí školní úspěšnosti -SPAS. Bratislava: Psychodiagnostika. ISBN 80-7169-195–X.

- McCaleb, A., & Edgil, A. (1994). Self-concept and self-care practices of healthy adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Nursing of Children and Families, 9(4), 233–238. ISSN 0882-5963.

- Miovský, M., Adámková, T., Čablová, L., Čech, T., Doležalová, P., Endrodiová, L., Gabrhelík, R., Charvát, M., Jurystová, L., Macková, L., Martanová V., Nevoralová, M., Novák, P., Orosová, O., Skácelová, L., Šťastná L., Siručková, M., Štefunková, M., Vacek, J. & Zapletalová, J. (2012). Výkladový slovník základních pojmů školské prevence rizikového chování. Univerzita Karlova v Praze, 1. lékařská fakulta, Klinika adiktologie 1. LF a VFN v Praze. ISBN 978-80-87258-89–7.

- Monk, L. (2011). Self-care for social workers. Perspectives, 33(1), 4–7. ISSN 2059 - 5816.

- Nevoralová, M., & A Čablová, L. (2012). Dovednosti sebeovlivnění 25-33. In Miovský, M., Adámková, T., Čablová, L., Čech, T., Doležalová, P., Endrodiová, L., Gabrhelík, R., Charvát, M., Jurystová, L., Macková, L., Martanová V., Nevoralová, M., Novák, P., Orosová, O., Skácelová, L., Šťastná L., Siručková, M., Štefunková, M., Vacek, J., Zapletalová, J Výkladový slovník základních pojmů školské prevence rizikového chování. 1. lékařská fakulta, Klinika adiktologie 1. LF a VFN. ISBN 978-80-87258-89-7.

- O’Neill, T. L. (2015). Academic motivation and student self-concept. the Keys to Positively Impacting Student Success.

- Orosová, O., Janovská, A., Kopuničová, V., Vaňová, M., (2012). Základy prevencie užívania drog a problematického užívania internetu v školskej praxi. Filozofická fakulta UPJŠ v Košiciach. ISBN 978-80-7097-946–8.

- Pestana, C. (2014). Exploring the self-concept of adults with mild learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 46(1), 16–23. ISSN 1468 - 3156. 1468–3156

- Pettit, J. W., Rey, Y., Bechor, M., Melendez, R., Vaclavik, D., Buitron, V., Bar-Haim, Y., Pine, D. S., & Silverman, W. K. 2011. Can less be more? Open trial of a stepped care approach for child and adolescent anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 51(9), 7–13. ISSN 0887-6185.

- Procházka, M. (2011). Sociálni pedagogika. Grada. ISBN 978-80-2473-470–5.

- Punová, M. (2012). Resilience v sociální práci s rizikovou mládeží. Sociální práce/Sociálna Práca. Brno: ASVSP, 4(2), 12–13. ISSN 1213 - 6204.

- Reel, J. J. (2018). Eating disorders: Understanding causes, controversies, and treatment. Santa Barbara, California, Greenwood. ISBN 978-1-4408-5301–2.

- Roberts, B. W., Wood, D., & Smith, J. L. (2010). Evaluating five-factor theory and social investment perspectives on personality trait development. Journal of Research in Personality, 39(1), 166–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2004.08.002

- Rogers, C. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-03-954-8357–2.

- Saraswath, R. K. (1984). Manual for self concept questionnaire. Published by National Psychological Corporation.

- Sebastian, C. (2008). Development of the self-concept during adolescent. Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

- Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Review of Educational Research, 26(3), 407–441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543046003407

- Shivani, A., Bhalla, P., Kaur, S. & Babbar, R. (2013). Effect of body mass index on physical self concept, cognition & academic performance of first year medical students. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 138(4), 515–522. ISSN 0250 - 6807.

- Šiňanská, K. (2015). Starostlivosť o seba v sociálnej práci ako inšpirácia pre vznikajúcu oblasť onkologickej sociálnej práce. Sociálna práca/Sociální práce, 5(17), 52–69. ISSN 1805-885X.

- Šiňanská, K., & Puškášová, A. (2014). Zmysel života jedinca s Huntingtonovou chorobou. In Ako nájsť zmysel života v sociálnej práci s rizikovými skupinami : 2. ročník Košických dní sociálnej práce : zborník príspevkov z vedeckej konferencie s medzinárodnou účasťou konanej dňa 22. 11. 2013 v Košiciach. Košice : Katedra sociálnej práce Filozofickej fakulty UPJŠ Košice. ISBN 978-80-8152-140–9.

- Širuček, J., & A Širučkova, M. (2012). Vývoj a zkoumání vrstevníckých vztahů. In P. Macek & L. A Lacinová (Eds.), Vztahy v dospíván (pp. 41–53). Barrister & Principal.

- Smith, M., Wethington, E., & Zhan, G. (1996). Self-concept clarity and preffered coping styles. Journal of Personality [Online], 64(2), 407–434. [cit 2019 10 25] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8656323 1467–6494

- Stewart, R. (2001). Adolescent self-care: Reviewing the isks. 82(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.213

- Szobiová, E., & A Jansová, D. (2005). Interpersonálne vzťahy a tvorivosť v adolescencii. Slovenská psychologická spoločnosť. ISBN 80-8068-377–8

- Tóthová, L., & Žiaková, T. (2019). Novodobé formy porúch príjmu potravy u adolescentov v kontexte preventívnej sociálnej práce. s. 118–127. In Tóthová, L., Šiňanská, K. (Eds.), Sociálne riziká v spoločnosti XXI. storočia. 7- ročník Košických dní sociálnej práce. ISBN 978-80-8152-722–7.

- Van Boxtel, H. W., & A Monks, F. J. (1992). General, social, and academic self-concepts of gifted adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21(2), 169–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537335

- Vaska, L. (2014). Teoretické aspekty supervízie začínajúcich sociálnych pracovníkov. IRIS. ISBN 978-80-8972-623–3.

- Výrost, J., & Slaměník, I. (2008). Sociální psychologie. Grada. ISBN 978-80-247-1428–8

- Wu, C. H. (2009). The relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity: The mediation effect of self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(1), 42–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.043