ABSTRACT

Resilience has been highlighted in educational policies internationally as one of the key elements that may prevent negative developmental trajectories, such as radicalization into violent extremism. To examine the factors that contribute to resilience at adolescence and to understand how resilience relates to wellbeing this study investigates the resilience resources of Finnish youth (n=2837). Furthermore, we examined the relationship between resilience and the youth’s self-reported levels of empathy and beneficence (pro-social orientation), life satisfaction and meaning in life (contentment with life), and their intention for non-violent action (activism), and intention for violent actions (radicalism). The results of the latent profile analysis suggest that high resilience resources are related to higher levels of pro-social orientation and contentment with life, while the opposite is true for low resilience resources. However, the findings do not indicate any significant connection between low resilience resources and an increased intent for activism or radicalism.

Introduction

Resilience refers to the ability to maintain psycho-social functioning and a coherent sense of self in situations of distress (Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005; R. M. Lerner et al., Citation2012; Richardson, Citation2002; Seligman, Citation2011). Resilience has been shown to be related to young people’s psychological well-being in various ways. Recent studies show that resilience supports people’s abilities to maintain their psychological and physical health during times of distress, which helps them manage the situation and experience it as less stressful (Vinayak & Judge, Citation2018). For example, studies indicate that resilience may act as a buffer for the negative impacts that bullying victimization has on adolescent’s well-being (Shemesh & Heiman, Citation2021). Previous findings also suggest that resilience is related to adolescents’ self-efficacy in problem-solving as well as to their efficacy to manage their expressions of positive and negative emotions (Sagone et al., Citation2020).

As resilience is a cognitive capacity that seems to mediate or, to some extent, reduce the impact of experienced adversities in one’s life, previous research has suggested that resilience ‘protects’ the youth from negative developments, such as radicalization into violent-supportive ideologies (Stephens et al., Citation2019; Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005). Studies suggest that radicalization into violent extremism can be associated with grievances, such as unsatisfied needs related to sense of significance (Kruglanski et al. Citation2019), poor relationships with one’s family, peers, or school (Raitanen, Citation2021; Theron & Engelbrecht, Citation2012), feelings of uncertainty (e.g. Hogg & Adelman, Citation2013), attraction for violence and adventure (Crone, Citation2016), and social environments that provide exposure and support for extremist influences (Bouhana, Citation2019), among other things. For example, experiences of social exclusion and injustice increase the sense of uncertainty making people more receptive to the appeal of extremist groups that typically provide clarity, a strong sense of social connectedness, and purpose (e.g. Berger, Citation2018; Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005; Hogg & Adelman, Citation2013; Womick et al., Citation2019; Kruglanski et al., Citation2019). Regarding these, resilience has been portrayed as a ‘shield’ that buffers the negative impact of adversity and reduces the pull of extremist groups and ideologies (e.g. Stephens & Sieckelinck, Citation2019).

Resilience has thus become one of the key focus areas of national action plans aiming to prevent violent extremism among youth both in schools (European Commission, Citation2020; Grossman et al., Citation2017; Taylor, E. et al., Citation2014; UNESCO, Citation2017; Weine et al., Citation2015) and in youth work (Sanders et al., Citation2015) internationally. The Finnish National Action Plan for the Prevention of Violent Extremism, to which some of the authors of this paper also contributed towards constructing, highlights the strengthening of resilience and well-being as central means for educational institutions and social and health services to prevent violent radicalization among young people (Finnish Ministry of the Interior, Citation2020). However, as Stephens and Sieckelinck (Citation2019) bring forward, the portrayal of resilience as a direct counter-force for violent extremism is also problematic, as policy documents do not usually define what type of behaviour or thinking is considered ‘resilient’. Focusing on resilience as a protective element may also neglect the fact that in some cases, adversities strengthen one’s resilience (Rutter, Citation2012). Furthermore, evaluation of the impact of resilience in terms of prevention of negative trajectories is difficult, if not impossible, as radicalization is a process involving several interconnected elements and interpretations at individual, community and societal levels (e.g. Hafez & Mullins, Citation2015).

The planning and implementation of resilience-focused programmes is thus not straightforward, partly due to the various expectations and outcomes that different theoretical approaches have associated with resilience (Christodoulou, Citation2020; Stephens & Sieckelinck, Citation2019). In addition, resilience is often measured only in terms of intensity (high vs low) (see Sagone et al., Citation2020; Shemesh & Heiman, Citation2021) that does not take into account the various factors in young people’s lives that contribute to its formation. In order to develop youths’ resilience in educational and youth work contexts, more information is needed on the resources that contribute to the formation of their resilience. To inform the planning of prevention policies and strategies, we also need more understanding of the outcomes that are associated with resilience. For increasing knowledge on these issues, this paper investigates the resilience resources of the Finnish youth (ages 16–19, n = 2837) through latent profile analysis and the connections that the profiles have with other areas of young people’s well-being, which were here studied through contentment with life, pro-social orientation, and intention for action.

Theoretical framework: resources-based approach to resilience

In this study, we approach resilience through the idea of internal and external resources that refer to those assets that help people cope with adversity and are thus connected to well-being more generally (Olsson et al., Citation2003). The internal resources related to resilience include self-esteem (Kocatürk & Çiçek, Citation2021) and a set of cognitive skills that enable maintaining and restoring well-being when the personal status quo is challenged (Olsson et al., Citation2003). One of them is self-regulation, the ability to adapt one’s thoughts, emotions and behaviour to meet the challenges imposed by a new situation (Gonzaléz-Torres et al., Citation2017; Kay, Citation2016). Self-regulation is related to a sense of autonomy and control (Lee et al., Citation2011; Motti-Stefanidi, Citation2015; NSCDC, National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, Citation2015; Stephens et al., Citation2019; Ungar & Liebenberg, Citation2011), and thus it is seen as central for the individual’s psychological well-being (Gilligan, Citation2000).

The external resources related to resilience consist of social relationships (Olsson et al., Citation2003). According to a large body of research, the external factors that strengthen resilience in adolescence are predominantly related to supportive relationships with caregivers, peers, and the school (e.g. Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005; Gilligan, Citation2000; Legault et al., Citation2006; Masten, Citation2014). The connectedness students feel to their school is enabled and fostered by feelings of physical and emotional safety in the school, and the experience of just treatment by others, especially the teachers (e.g. Meeuwisse et al., Citation2010; R. M. Lerner et al., Citation2012; Henderson, Citation2012; Theron & Engelbrecht, Citation2012; Niemi, Citation2017; Benjamin et al., Benjamin, et al., Citation2021b).

The internal and external resources enable the satisfaction of the basic psychological needs that include safety, autonomy, relatedness, and competence (e.g. Ryan & Deci Citation2000. Therefore, they can also be considered as prerequisites for well-being and positive growth (e.g. R. M. Lerner et al., Citation2012; Richardson, Citation2002; Seligman, Citation2011). The dissatisfaction of basic needs, in turn, is closely associated with the risk of negative developmental trajectories. For example, experiences of discrimination, exclusion or bullying reduce the feelings of inclusion and well-being and may increase the probability of negative behaviours (Benner et al., Citation2018; Salmivalli & Peets, Citation2018). What is central in the process is not the accumulation of adversities but the resources that people have in addressing them (Benjamin et al., Citation2021a; Greene, Citation2009; Newman & Blackburn, Citation2002).

Outcomes associated with resilience in adolescence

As resilience and the resources supporting it are closely related to well-being, it can be expected that resilience is also connected to positive psychosocial outcomes. For gaining more insights into these aspects, this study investigates the relationship that resilience has with the youth’s pro-social orientation, contentment with life, and intention for action. Intention for action refers here to the willingness to act on behalf, or to use violence for a meaningful cause (see Moskalenko & McCauley, Citation2009).

Contentment with Life

Previous studies show a positive relation between resilience, life satisfaction, and experiences of meaning in life (e.g. Kocatürk & Çiçek, Citation2021; Aboalshamat et al., Citation2018; Sanders et al., Citation2015; Shi et al., Citation2015). The findings indicate that people who are resilient also find life more meaningful and satisfactory and are more able to act according to their values than people who are not resilient. This is understandable, as the resources that strengthen resilience, such as supportive relationships, are also those that are closely linked to happiness (Delle Fave et al., Citation2011). Life satisfaction refers to the level of satisfaction that people report when they cognitively evaluate their life as a whole (Pavot & Diener, Citation2008). Meaning in life, in turn, refers to ‘the sense made of, and significance felt regarding, the nature of one’s being and existence’ (Steger et al., Citation2006, p. 81). Steger et al. (Citation2006) argue that meaning in life can be observed as two-fold; as the search for meaning (the engagement to the search for meaning) and as the presence of meaning (the perception of one’s life as meaningful). Both meaning in life and life satisfaction are supported by a clear sense of values and the abilities to live and act according to them (see Womick et al., Citation2019). Previous studies also suggest that if a person’s basic needs for safety, autonomy, significance, and connectedness are not satisfied, the individual may be more prone to the appeal of the narratives and identities provided by extremist groups (Kruglanski et al., Citation2019; Vergani et al., Citation2018; Hayes, Citation2017). In this study, the satisfaction with life and meaning in life compose the dimension of well-being entitled as Contentment with life.

Pro-social orientation

As resilience is an important objective in many educational programmes that aim to promote solidarity and prevent negative developments, it is of interest to investigate the way it relates to empathy and care for others. Studies have shown that benevolence, the willingness to contribute to the well-being of others, forms an important dimension of subjective well-being (Martela & Ryan, Citation2015). As Martela and Ryan (Citation2015) bring forward, people have almost needs-like tendencies to do good to others and act in their benefit. A central component of benevolence is the feeling of beneficence that refers to the cognitive evaluation of one’s contribution for the betterment of other people’s lives (Martela & Ryan, Citation2015, see alsoWomick et al., Citation2019). As studies have shown, acting pro-socially increases the experienced meaning in people’s lives, which, again, contributes to their subjective well-being (Martela & Ryan, Citation2015; Van Tongeren et al., Citation2016). It is important to note that this readiness may also be misused by different actors for malicious purposes, for example, by extremist groups who call upon the benevolence of ‘their people’, the members of the ingroup, to join them in the efforts to rectify shared grievances, which the outgroup are typically blamed for (e.g. Womick et al., Citation2019, Kruglanski et al., Citation2019; Berger, Citation2018).

Closely related to benevolence, empathy refers to the ability to relate to and feel for people who are suffering or who are in other ways in an unfortunate situation (e.g. Batson, Citation2009). The ability to feel and show empathy is based on biological tendencies, and it is a central feature in the formation and maintenance of social bonds and groups (Batson Citation2009; Vaes et al., Citation2012). However, the scope of empathy is limited – empathy may be felt exclusively towards people who are perceived as part of one’s ‘in-group’ (e.g. Vaes et al., Citation2012). Empathy is a skill that can be practised (Stanley & Bhuvaneswari, Citation2016), but it can also be intentionally weakened. For example, explicit depreciation and dehumanization of out-groups through, for example, the spreading of propaganda and disinformation are likely to attenuate empathy towards them (Maynard, Citation2014; Berger, Citation2018).

For gaining more insights into the topic, this study investigates the relationships between the young people’s resilience and their feelings of beneficence and empathy that compose the dimension of well-being entitled as Pro-social orientation.

Intention for action

As resilience is depicted in many prevention programmes and action plans (e.g. Finnish Ministry of the Interior, Citation2020; Weine et al., Citation2015; Christodoulou, Citation2020) as the counterforce for negative developments, such as radicalization, it is of interest to examine its relation to the intention for (violent) actions (Moskalenko & McCauley, Citation2009). To this end, this study explores the young people’s views about their willingness to accept the use or use violence themselves as means to promote a meaningful cause. As a concept, intention for action includes activism that refers to endorsement of non-violent forms of influence. In this study, activism is approached as the willingness to participate in legal and non-violent actions for supporting a cause one deems valuable. Examples of such activities are adherence in an organization, participation in demonstrations, and related tasks such as the distribution of flyers (Moskalenko & McCauley, Citation2009). Radicalism, in turn, refers to the endorsement of violent forms of activism. It denotes a willingness to participate in illegal or violent actions or inclination to support the use of violence for a cause deemed valuable (Moskalenko & McCauley, Citation2009). The two types of intentions for action, activism and radicalism, are independent of each other, which makes it important to study them as separate dimensions (see Moskalenko & McCauley, Citation2009).

Aim of this study

The aim of this study is to contribute to the existing research on resilience in youth and to the use of this knowledge in the prevention of negative developmental trajectories. To this end, this study explores the dimensions and outcomes related to resilience among Finnish youth. This objective is approached through the following two research questions:

1) how are the resources supporting resilience displayed in the resilience profiles of Finnish adolescents (16 to 19 year olds)?

2) how are the identified resilience profiles related to three dimensions of well-being, namely, contentment with life, pro-social orientation, and intention for action?

Method

Data and participants

The data were collected from Finnish adolescents through an online survey during autumn 2019 as part of a larger mixed methods study design (Cohen et al., Citation2018). The data collection were done as part of the research project ”Growing up Radical? The role of educational institutions in guiding young people's worldview construction”. The survey was carried out at upper secondary level schools and vocational institutions located in eight municipalities across Finland. Ethical approvals for the study were applied from and granted by the University of Helsinki, University of Oxford, and by all the municipalities in which the educational institutions are located. The purpose of the study was explained at the beginning of the online questionnaire where it was also explained that no personal data of the respondents were collected, that answering the survey was voluntary, and that the respondents could withdraw from answering at any point.

Of all the respondents (n = 2837), 54.6% identified as female, 41.6% identified as male, and 3.8% either identified as other or did not want to specify their gender. Out of all the responses, 84% were from upper secondary school students and 16% from youth attending vocational institutions.Footnote1 Most of the respondents (app. 90%) were between 16 and 18 years old (Mage = 17.2). Around 5% were 19 years old, three percent were 20 years old or older and less than half a percent (0.3%) were 15 years old. Geographically, the largest respondent group (45.6%) was from those residing in the Helsinki capital area. The majority of the total respondents (91%) reported Finnish as their first language. Although the remaining 9% have another mother tongue, it must be noted that all respondents studied in Finnish speaking upper-secondary level educational institutions and responded to the survey in Finnish, indicating proficiency in Finnish language. Students’ ethnic affiliation was inquired in the survey, but as the responses indicated such a variety of different interpretations of the meaning of ethnicity, the item was omitted from the analysis.

Measures

The questionnaire consisted of both previously established and psychometrically validated scales and measures tailored by the authors for the purposes of this study. Reliability scores for all scales were calculated by using Cronbach’s alpha. Descriptive statistics of the used scales can be reviewed from . Correlations between the used measures are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Table 2. Correlations

Demographic information included gender (m/f/other), educational institution (upper secondary school/vocational institution), geographical location (Helsinki capital area/other areas). Another background factor examined was experiences of discrimination, which were measured with a three-point scale (for having experienced these ‘often’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘never’) developed for the purposes of this study. The questions asked the respondents to mark if they had experienced discrimination based on their personal characteristics (e.g. sexual orientation, sexual identity, or native language), physical features (e.g. appearance or style), or ideologies (e.g. religious, political or other stances). A count score representing total exposure to discrimination was created and used as a predictor variable to see if experiences of discrimination would have an impact on the respondent’s profile of resilience resources.

Profile indicators of resilience resources

We measured resilience through three dimensions, which previous studies have found to be central in contributing to the development of resilience in young people (Ungar & Liebenberg, Citation2011). These are the internal resources measured by (1) self-regulation, and the external resources measured by (2) peer relations, and (3) caregiver support (Ungar, Citation2016; Ungar & Liebenberg, Citation2011). As a fourth dimension, we added (4) school safety and connectedness to external resources, as educational institutions represent significant and longstanding growing up contexts in the lives of young people. All four dimensions were measured with items answered on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = does not fit/describe me at all and 5 = fits/describes me perfectly). Most of the used measures were originally in English, and they were translated into Finnish by the researchers.

Self-regulation skills were measured with four items that we adopted and modified from the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) (Ungar, Citation2016). Example items include ‘I try to finish activities that I start’ and ‘I know how to behave in different social situations’ (α = .70).

Peer relations were measured with four items adopted from the Revised Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-R) (Jefferies & McGarrigle, Citation2018). Example items include ‘I feel supported by my friends’ and ‘People think I am fun to be with’ (α = .86).

Caregiver support was measured with four items we adopted from CYRM (Ungar, Citation2016). Example items include ‘I can talk with at least one family member about how I feel’ and ‘My family cares about me when times are hard’. In addition to these, we included an additional item to measure the financial security of the family. Sum scores were formed for the five items (α = .80) to represent the students’ caregiver support.

School Safety and Connectedness was measured with five items, which we adopted from the California School Climate, Health and Learning survey measure (Hanson & Voight, Citation2014). The here-included items focused on covering particularly the dimension of school safety and connectedness. Example items include ‘I feel close to people at this school’ and ‘Teachers at school treat students fairly’ (α = .81).

Resilience’s relation to the dimensions of well-being

Contentment with life

Meaning in life

Meaning in life was measured with three items adopted and modified from the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (Steger et al., Citation2006). The items were answered with a score from 1 to 4 (1 = I disagree completely to 4 = I agree fully). Sum scores and Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the scale showed, however, that only two of the items contributed to the scale. Therefore, sum scores for students’ meaning of life were measured only with items ‘I know what makes my life meaningful’ and ‘I am trying to do things that I consider valuable’ (α = .60).

Satisfaction with life

Satisfaction with life was measured with five items adopted from the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., Citation1985) and answered with a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = does not fit/describe me at all and 5 = fits/describes me perfectly). Example items include ”The conditions of my life are excellent” and ‘I am satisfied with my life’ (α = .89).

Pro-social orientation

Empathy

Empathy was measured with four items we adopted and modified from the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, Citation1983) focusing on empathic concern. The items were measured with a scale from 1 to 4. Example items include ”I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me” and ‘When I see someone being taken advantage of, I feel kind of protective towards them’ (α = .80).

Beneficence

Beneficience was measured with four items we adopted from the Beneficence Scale to Assess Sense of Pro-Social Impact (Martela & Ryan, Citation2015) and measured with a scale from 1 to 5. Example items include ”I feel that my actions have a positive impact on the people around me” and ‘The things I do contribute to the betterment of society’ (α = .86).

Activism

Activism was measured with two items we adopted from the Activism and Radicalism Intention Scale (Moskalenko & McCauley, Citation2009). The original scale included four items for activism but two of the items were omitted as they were not well suited for studying youth in the Finnish context. The items were measured with a scale from 1 to 4 (1 = completely disagree and 4 = completely agree). The two included items were ‘I would be willing to join an organization that supports issues that are important to me’ and ‘I would volunteer my time working for issues that are important to me’ (α = .75).

Radicalism

Radicalism was measured with two items adopted from the Activism and Radicalism Intention Scale (Moskalenko & McCauley, Citation2009). The original scale included four items for radicalism but two of them were not well suited for studying youth in the Finnish context, so they were omitted. The items were measured with a scale from 1 to 4 (1 = completely disagree and 4 = completely agree). The two included items were ”I would be willing to participate in activities in which some people use violence to promote a cause/community” and ‘I would be willing to support a cause/community by using violence myself’ (α = .86).

Analysis procedures

First, we screened the data for possible outliers and missing values in SPSS 25. Based on the initial screening of the respondents, we did not identify outliers but removed 23 responses based on their open answers that were considered frivolous. For the rest of the respondents (n = 2837), the missing data analysis showed that there were 0.8% of the values missing, and the non-parametric test of homoscedasticity (Jamshidian & Jalal, Citation2010) indicated that the data was missing completely at random (p = 0.68).

Second, following a person-oriented approach (see Bergman et al., Citation2003), we subjected the resilience resources to latent class modelling. Students with similar patterns of resources were identified through latent profile analysis (LPA), a model-based clustering method that assigns profile membership probabilities for each participant across each profile. For determining statistically the most correct number of profiles, we relied on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin (VLMR) nested model comparison. VLMR tests the fit between model k and k-1. A lower BIC value suggests a better fit and a p-value of VLMR less than .05 indicates that k-1 should be rejected in favour of the estimated model k (see Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2021). We also considered classification quality (i.e. entropy value), the interpretableness of the latent profiles, and the reasonableness of the solutions with respect to theory. The analyses were conducted using Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2018) in conjunction with R and RStudio (R Core Team, 2020) with the package MplusAutomation (Hallquist & Wiley, Citation2021). Maximum likelihood with standard errors robust for non-normality (MLR) was used as the estimator and missing data was handled with full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML).

After deciding on the optimal number of latent profiles, we ran the analyses with the auxiliary variables utilizing the Mplus three-step approaches (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014, Citation2021), which take into account the classification uncertainty. The relation of profile membership on covariates was estimated as logistic regression with the profile memberships as the dependent variable, using the R3STEP-method. Then, mean differences across profiles in the pro- and anti-social orientations and intentions to action were estimated with the BCH-method. (Data and code to reproduce the analyses can be found here: https://osf.io/5wn6y/files/.)

Results

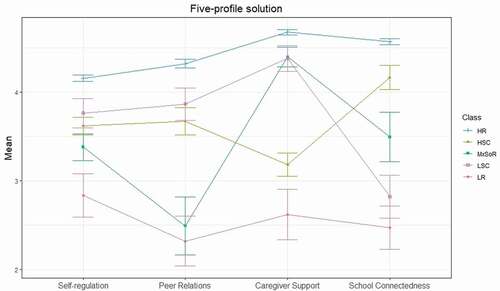

To answer the first research question, how are the resources supporting resilience displayed in the resilience profiles of Finnish adolescents? the series of latent profile analyses (see ) indicated that the BIC decreased when additional latent classes were added, but the VLMR test provided support for the five-class solution, but not six. According to the fit indices, decrease in BIC was rather small, we ended up with the five-class solution. Most importantly, the classes in the chosen solution were useful and interpretable. These indicated that the five-class model provided a useful classification.

Table 3. The five-class model of classification

The groups were labelled based on the score mean profiles (see and ) as follows: Low Resilience (~5%), High School Connectedness (~14%), Mixed Social Resources (~11%), High Resilience (~63%), and Low School Connectedness (~8%). The average probabilities for being assigned to a specific class were, in respective order, .88, .84, .79, .94, and .78.

Table 4. Profile groups

The biggest group was the High Resilience group (63% of the respondents) that was characterized by the highest mean scores in all of the measured dimensions of self-regulation, peer relations, caregiver support, and school safety and connectedness. The smallest identified group was the Low Resilience group (5%) that is characterized by low scores in all of the studied dimensions. In addition to these expected two resilience groups, three other groups are identified that differ both from the High and Low Resilience groups. The second largest group, High School Connectedness (14%), is characterized by high School safety and connectedness scores, but reports a low caregiver support. Contrary to this, the Low School Connectedness group (8%) was characterized by high caregiver support, but low School safety and connectedness. Set in between the other profiles was Mixed Social Resources group (11%) that was characterized by low peer relations and high caregiver support. The identified groups thus show that the resilience resources differ particularly in terms of experienced caregiver support and school safety and connectedness.

We then proceeded to estimate the relations of covariates: gender, educational status, geographical location (Helsinki capital area vs. other areas) and experiences of discrimination on the profile memberships. The results indicated that compared to the High Resilience group, participants who identified as boys were less likely to belong to High School Connectedness (OR = 0.61, [0.45, 0.83]) or Low School Connectedness groups (OR = 0.61, [0.41, 0.90]). Studying in vocational school instead of high school (i.e. academic track) was related to a higher probability of being in Low Resilience group (OR = 2.52, [1.37, 4.62]). Having experienced discrimination increased the probability of being assigned to any other group than High Resilience: Low Resilience (OR = 1.37, [1.29, 1.45]), High School Connectedness (OR = 1.28, [1.22, 1.35]), Mixed social resources (OR = 1.12, [1.04, 1.20]), or Low School Connectedness (OR = 1.22, [1.14, 1.30])

Finally, to answer the second research question (what are the ways in which the identified resilience profiles are related to three dimensions of well-being, namely, orientation towards others, contentment with life, and intention for action), we estimated the profile mean differences across the auxiliary variables of pro-social orientation, contentment with life, and intentions for action. As can be seen from , the profiles differed across all auxiliary variables.

Table 5. Profile group difference

By inspection of pairwise comparisons, we can deduct that High Resilience and Low Resilience groups differ significantly from each other in all of the measured dimensions. The most notable difference between the groups is indicated by life satisfaction that is highest in the High Resilience group (M = 3.96) and lowest in the Low Resilience group (M = 1.85). The difference between High Resilience and Low Resilience groups is particularly recognizable in the dimensions of empathy and feeling of beneficence. However, while the reported feelings of empathy and beneficence are highest in the High Resilience group, the difference between High Resilience and High School Connectedness is not significant. Regarding the intention for action, the groups most in favour of activism is High School Connectedness group and High Resilience group. The group most in favour of radicalism as intention for action is Low Resilience, but the difference is not significant when compared to the groups of High School Connectedness or Low School Connectedness.

Discussion

To contribute to the existing research on resilience in youth and investigate how this knowledge could be utilized in the prevention of negative developmental trajectories, this study explored the the resilience resources of Finnish youth (n = 2837) and the dimensions of well-being related to it. The analysis yielded five distinct resilience profiles, in which the strongest differences can be detected between the High Resilience and Low Resilience profiles. The results show that the majority of the youth belonged to the High Resilience group and that even the Low Resilience group has access to some resilience-supporting resources. These findings support previous studies that have shown that Finnish youth have predominantly high levels of well-being (THL, Citation2018). In comparison to these two profiles, the three other profiles, which are located in between the high and low ends, all display relatively high levels of resilience in general, but the contributive resources differ between these.

The main indicators of the resilience profiles

The results indicate that the most pronounced differences between the profiles concern the external, context-related resources (relationships with peers, caregivers, and school). These findings suggest that having supportive social resources in one context of life does not necessarily indicate having similar support in other contexts of life. Especially, the levels of experienced school safety and connectedness differed between the profiles. For example, in the Mixed Social Resources profile, the reported peer support is low, but both the caregiver support and the experienced school safety and connectedness were strong. Furthermore, this was illustrated in the High School Connectedness profile, in which the experienced school safety and connectedness was the highest in all the measured dimensions. Thus, even though the overall resilience can be high, there can be dimensions in the youths’ social resources that are not equally strong.

The results show that the role of demographic factors as profile predictors is small in the Finnish context. However, prior experiences of discrimination do influence the level of youths’ resilience in this sample. The youth who reported experiences of discrimination had an increased probability of belonging to some other groups than the High Resilience group. This finding may be explained by the fact that experiences of discrimination are negative forms of social encounter and thus they are likely to reduce the perceived social support, a central factor of resilience. Nevertheless, as resilience can be developed by successfully overcoming hardships, such as discrimination (R.M. Lerner et al., Citation2005; Reivich & Shatté, Citation2002; Richardson, Citation2002), the relationship between experiences of discrimination and lower resilience is not as straightforward as our findings could suggest and necessitates further investigation.

Resilience, contentment with life, pro-social orientation, and intention for action

Regarding the second objective, which was to understand the relationships between resilience and the dimensions of well-being and intention for action, the results show that higher levels of resilience resources indicate higher scores in the dimensions measuring pro-social orientation than low resilience resources. The feelings of beneficence were notably low in the Low Resilience profile, indicating that the people in this group do not feel that they contribute to the well-being of others, even though they reported empathetic feelings for others. Similar tendency concerns the Mixed Social Resources profile group. Likewise, the experienced Life satisfaction differs remarkably between the High Resilience and Low Resilience profiles. The results thus suggest that those young people who experience strong social support from their peers, caregivers, and feel that they are connected to their school and contribute positively around them are more content with their life than the those who do not. These findings support the evidence gained from previous studies that acting for the good of the others increases people’s life satisfaction and the sense of meaning in their lives (Martela & Ryan, Citation2015; Van Tongeren et al., Citation2016). These findings thus imply that activities aiming to foster youths’ resilience should not only focus on their individual resources, but also include interpersonal, pro-social elements that enable benevolence and the feeling of beneficence (see also Henderson, Citation2012; Martela & Ryan, Citation2015).

Regarding the intention for action, the findings showed similar tendencies than previous studies in the way that activism was more supported among the youth than radicalism (see Costabile et al., Citation2020; Pfundmair et al., Citation2021). It is noteworthy that the results do not indicate any resilience profile to have an increased tendency to endorse violence as a means to advance a cause. This finding is important, as the accumulation of negative insights (indicated by low scores in life satisfaction, feeling of beneficence, and the diminished presence of resilience resources) typical for the Low Resilience profile, is what previous studies have associated with radicalization into violent extremism (e.g. Womick et al., Citation2019; Kruglanski et al., Citation2019). This finding questions the efficacy (and ethicality) of resilience-focused prevention programmes that are targeted for ‘at-risk’ students only, and as per our findings, they are not significantly more willing to accept the use of violence or use violence themselves than their peers with high resilience resources.

Limitations and further research

The findings of this study need to be interpreted with certain caution. We acknowledge that all survey studies may be influenced by social desirability bias (e.g. Caputo, Citation2017) as well as by careless responding (Kam et al., Citation2015). To minimize skewness, careful examination of the data was done before conducting the analysis. However, regarding the limitations of the study, it needs to be noted that even though the data includes representation from different geographical areas in Finland, including cities, towns, and rural areas, and from varied groups of youth, the data are not fully representative of all Finnish upper-secondary level students. Furthermore, the background factors of native language, ethnicity, or religion were not utilized in this study as they could not be applied in a way that would have allowed meaningful statistical comparisons between different groups. These background factors might, however, be relevant in some other national contexts.

Furthermore, as the survey responses were collected through educational institutions, the data lack those youth that are likely to have the most limited resources for resilience. Thus, further investigation is needed especially on the resilience resources of those young people who are not working or studying. Also, more in-depth research is needed on the impacts of negative social experiences, such as discrimination, on youths’ resilience, which this study does not provide. The qualitative interview data gathered from some of the youth participating in this study (N = 45) will contribute towards filling this gap. However, more knowledge is needed on these aspects in order to be able to further inform and update the research, policy, and practice in this area. Finally, it needs to be noted that this study measures resilience through the resources that the youth reported having access to. However, how their resilience manifests in challenging situations cannot be predicted based on these findings. Regardless of these limitations, we believe that this study provides novel knowledge about the resilience resources among Finnish youth and the ways these are related to the youth’s pro-social orientation, contentment with life, and their intention for (non-violent and violent) action.

Conclusions and suggestions

The findings of our study show that most Finnish students have good access to the internal and external resources that previous studies have associated with resilience. In line with previous research (Sanders et al., Citation2015; Aboalshamat et al., Citation2018,; Shi et al., Citation2015), the findings of this study also consolidate the congruence between resilience and well-being. The youth with the highest resources for resilience showed high levels of contentment with life, pro-social orientation towards others, and low acceptance of violence. Whereas our findings did not indicate an increased risk for the willingness to use or accept the use of violence among the youth with the lowest resources for resilience, the overall well-being of these young people raises some concerns.

As the youth with the lowest resilience resources also displayed the lowest contentment with life, lowest pro-social orientation and low levels of school connectedness and caregiver support, they have an increased risk of dropping out of school and experiencing further social and societal marginalization. However, the findings of this study also indicate that having limited access to some of the resources can be compensated with access to resources in another area of life, as shown by the profiles of Mixed Social Resources, High School Connectedness, and Low School Connectedness. This is an important aspect to consider in educational institutions.

Based on the findings of this study, we suggest that focusing on developing resources that are associated with youths’ resilience is an important objective for educational institutions. However, recognizing the multiple contexts in which these resources develop, the development of seamless multi-professional collaboration between the schools, social and health services, and youth work becomes central. Key objectives here include the fostering of the youths’ self-regulation skills and supporting them in creating and maintaining positive relationships with peers, caregivers, and the school. While these are essential also in the prevention of radicalization into violent extremism, the findings of this study suggest that resilience should be fostered first and foremost for its positive connection with general well-being and prosociality in youth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pia Koirikivi

Pia Koirikivi, PhD, is a post-doctoral researcher and university lecturer at the Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland. Pia is interested in the ways in which educational systems and institutions can respond to the social, emotional, and academic needs of young people. Pia is a post-doctoral researcher in the ”Growing up radical? The role of educational institutions in guiding young people's worldview construction” research project funded by the Academy of Finland (Grant 315860) 2018-2022.

Saija Benjamin

Saija Benjamin is a post-doctoral researcher in the ‘Growing up radical? The role of educational institutions in guiding young people’s worldview construction’ research project2018-2022 (funded by the Academy of Finland Grant 315860)at the Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland. Saija is interested in the elements influencing identity & ingroup/outgroup & worldview construction at adolescence. Related to this, she is looking at the possibilities of formal education to foster the development of metacognition that is central in the prevention of harmful developments, such as radicalization.

Lauri Hietajärvi

Lauri Hietajärvi is a researcher and university lecturer in educational psychology at Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki. Lauri has been working with various cross-sectional and longitudinal datasets utilizing several statistical methods, including between and within-person variable- and person-oriented approaches. Substance-wise Lauri studies academic well-being across all levels (principals, teachers, students) as well as adolescence from multiple perspectives (e.g., identity formation, digital engagement).

Arniika Kuusisto

Arniika Kuusisto is a Professor in Child and Youth Studies, especially Early Childhood Education and Care, at the Department of Child and Youth Studies, Stockholm University. Arniika is especially interested in children and young people’s value learning trajectories and in the interplay between agency and socialization in children’s growing up contexts. Her research interests also include worldview education in different levels, and educator professionalism and sensitivity to diversities. Arniika is the leader of the ‘Growing up radical? The role of educational institutions in guiding young people’s worldview construction’ research project funded by the Academy of Finland (Grant 315860) 2018-2022.

Liam Gearon

Liam Gearon is Associate Professor in Religious Education in the Department of Education, Senior Research Fellow at Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford, UK. A philosopher and theorist of education, Liam is a specialist in critical, historical and contemporary analyses of education in multi-disciplinary contexts. He is interested in the historical determinants of counter-extremism in education and in the youth’s value learning and life history research in political and security contexts. Liam is a supervisor and co-investigator in the ‘Growing up radical? The role of educational institutions in guiding young people’s worldview construction’ research project funded by the Academy of Finland (Grant 315860) 2018-2022.

Notes

1. As regards the distribution of the respondents in the academic vs vocational tracks in education, the sample is not statistically representative as the national distribution of secondary school affiliation was 54% for upper secondary schools and 40% for vocational institutions in 2019. Three percent continued in other preparatory education and 2,4% did not continue in any formal education. (Stat.fi/2020) Regarding this, continuing education until the age of 18 has become compulsory in Finland from 2021 onwards.

References

- Aboalshamat, K. T., Alsiyud, A. O., Al-Sayed, R. A., Alreddadi, R. S., Faqiehi, S. S., & Almehmadi, S. A. (2018). The relationship between resilience, happiness, and life satisfaction in dental and medical students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 21(8), 1038–1043.

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using M plus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2021). Using Mplus TECH11 and TECH14 to test the number of latent classes. Mplus Web Notes, 14, 22 https://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote14.pdf

- Batson, C. D. (2009). “These things called empathy: eight related but distinct phenomena. In J. Decety & W. Ickes (Eds.), The Social Neuroscience of Empathy (pp. 3–15). The MIT Press.

- Benjamin, S., Gearon, L., Kuusisto, A., & Koirikivi, P. (2021a). Threshold of adversity: resilience and the prevention of extremism through education. Nordic Studies in Education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23865/nse.v41.2593

- Benjamin, S., Salonen, V., Gearon, L., Koirikivi, P., & Kuusisto, A. (2021b). Safe space, dangerous territory: Young people’s views on preventing radicalization through education – Perspectives for pre-service teacher education. Education Sciences, 11(5), 1–18.

- Benner, A. D., Wang, Y., Shen, Y., Boyle, A. E., Polk, R., & Cheng, Y.-P. (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. American Psychologist, 73(7), 855–883. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000204

- Berger, J. M. (2018). Extremism. Kindle ed. MIT Press

- Bergman, L. R., Magnusson, D., & El-Khouri, B. M. (2003). Studying individual development in an interindividual context: A person-oriented approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bouhana, N. (2019). The Moral Ecology of Extremism: A Systemic Perspective. Department of security and crime science.

- Caputo, A. (2017). Social Desirability Bias in self-reported well-being Measures: Evidence from an online survey. Universitas Psychologica, 16(2), 2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana

- Christodoulou, E. (2020). ”Boosting resilience” and “safeguarding youngsters at risk”: Critically examining the European Commission’s educational responses to radicalization and violent extremism. London Review of Education, 18(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.18.1.02

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Costabile, A., Iannello, N., Servidio, R., Bartolo, M., Palermiti, A., Musso, P., & Scardigno, R. (2020). Adolescent psychological well-being, radicalism, and activism: the mediating role of social disconnectedness and the illegitimacy of the authorities. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12590

- Crone, M. (2016). Radicalization revisited: violence, politics and the skills of the body. International Affairs, 92(3), 587–604.

- Davis, M. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

- Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Freire, T., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Wissing, M. (2011). The eudaimonic and hedonic components of happiness. Qualitative and Quantitative Findings. Soc Indic Res, 100(2), 185–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9632-5

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- European Commission. (2020). Radicalisation Awareness Network. Education Working group. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/. (Accessed 17 August 2021.)

- Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M.-A. (2005). Adolescent Resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26(1), 399–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357.

- Finnish Ministry of the Interior. (2020). Kansallinen väkivaltaisen radikalisoitumisen ja ekstremismin ennalta ehkäisyn toimenpideohjelma [The national action plan for the prevention of violent radicalisation and extremism].

- Gilligan, R. (2000). Adversity, resilience and young people: the protective value of positive school and spare time experiences. 14(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2000.tb00149.x

- Gonzaléz-Torres, A. R., De La Fuente, J, M. C., & Lopez-Garcia, M. (2017). Relationship between resilience and self-regulation: A study of Spanish youth at risk of Social Exclusion. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(616), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00612

- Greene, R. (2009). Lost at school. New York: Scribner.

- Grossman, M., Ungar, M., Brisson, J., Gerrand, V., Hadfield, K., & Jefferies, P. (2017). Understanding youth resilience to violent extremism: A standardised research measure final research report. Available at: http://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1374679/Understanding-Youth-Resilience-to-Violent-Extremism-the-BRAVE-14-Standardised-Measure.pdf (accessed 10 May 2019)

- Hafez, M., & Mullins, C. (2015). The radicalization puzzle: A theoretical synthesis of empirical approaches to homegrown extremism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 38(11), 958–975. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2015.1051375

- Hallquist, M. N., & Wiley, J. F. (2021). MplusAutomation: An R Package for Facilitating Large-Scale Latent Variable Analyses in Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling, 25(4) , 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1402334

- Hanson, T., & Voight, A. (2014). The appropriateness of a California student and staff survey for measuring middle school climate.The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. E-publication. Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Deparment of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/west/pdf/REL_2014039.pdf. (Accessed 21 February 2020)

- Hayes, S. W. (2017). Changing Radicalization to Resilience by Understanding Marginalization. Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice, 29(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2017.1308190

- Henderson, N. (2012). Resilience in Schools and Curriculum Design. In M. Ungar (Ed.), The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice (pp. 297–306). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0586-3_23

- Hogg, M. A., & Adelman, J. (2013). Uncertainty–Identity Theory: Extreme Groups, Radical Behavior, and Authoritarian Leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 436–454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12023

- Jamshidian, M., & Jalal, S. (2010). Tests of Homoscedasticity, Normality, and Missing Completely at Random for Incomplete Multivariate Data. Psychometrika, 75(4), 649–674. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-010-9175-3

- Jefferies, P., & McGarrigle, L. (2018). The CYRM-R:A Rasch-Validated Revision of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 15(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2018.1548403

- Kam, C. C. S., & Meyer, J. P., & Kam, & Meyer, J. P. (2015). How Careless Responding and Acquiescence Response Bias Can Influence Construct Dimensionality: The Case of Job Satisfaction. Organizational Research Methods, 18(3), 512–541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115571894

- Kay, S. (2016). Emotion Regulation and Resilience: Overlooked Connections. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9(2), 411–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2016.31

- Kocatürk, M., & Çiçek, I. (2021). Relationship Between Positive Childhood Experiences and Psychological Resilience in University Students: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2021.16.

- Kruglanski, A., Bélanger, J., & Gunaratna, R. (2019). The Three Pillars of Radicalisation: Needs, Narratives, and Networks. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lee, T., Cheung, C., & Kwong, W. (2011). Resilience as a Positive Youth Development Construct: A Conceptual Review. The Scientific World Journal, 3, 390450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/390450.

- Legault, L., Anawati, M., & Flynn, R. (2006). Factors favoring psychological resilience among fostered young people. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(9), 1024–1038. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.10.006

- Lerner, R. M., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., & Lerner, J. V. (2005). Positive Youth Development. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 10–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431604273211

- Lerner, R. M., Bowers, E. P., Geldhof, G. J., Gestsdottir, S., & DeSouza, L. (2012). Promoting Positive Youth Development in the face of contextual changes and challenges: The roles of individual strengths and ecological assets. New Directions for Youth Development, 135(135), 119–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20034

- Martela, F., & Ryan, M. F. (2015). The Benefits of Benevolence: Basic Psychological Needs, Beneficence, and the Enhancement of Well-Being. Journal of Personality, 84(6), 750–764. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12215

- Masten, A. (2014). Invited Commentary: Resilience and Positive Youth Development Frameworks in Developmental Science. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 1018–1024. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0118-7

- Maynard, J. (2014). Rethinking the Role of Ideology in Mass Atrocities. Terrorism and Political Violence, 26(5), 821–841. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2013.796934

- Meeuwisse, M., Severiens, S., & Born, M. (2010). Learning environment, interaction, sense of belonging and study success in ethnically diverse student groups. Research in Higher Education, 51(6), 528–545. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9168-1

- Moskalenko, S., & McCauley, C. (2009). Measuring Political Mobilization: The Distinction Between Activism and Radicalism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 21(2), 239–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09546550902765508

- Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2015). Identity Development in the Context of the Risk and Resilience Framework. In K. McLean, and M. Syed Eds., The Oxford Handbook of Identity Development. 472–489. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199936564.013.014

- Muthén, L. & Muthén, B. (2021). Mplus. Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. User’s Guide. https://www.statmodel.com/html_ug.shtml

- Newman, T., & Blackburn, S. (2002). Transition in the lives of children and young people: Resilience Factors. Interchange 78. Scottish Executive Education Department.

- Niemi, P.-M. (2017). Students’ experiences of social integration in schoolwide activities—an investigation in the Finnish context. Education Inquiry, 8(1), 68–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2016.1275184

- NSCDC, National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2015). Supportive Relationships and Active Skill-Building Strengthen the Foundations of Resilience: Working Paper 13. http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu. Accessed 1 June 2019

- Olsson, C., Bond, L., Burns, J., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Sawyer, S. (2003). Adolescent resilience: A concept analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00118-5

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946

- Pfundmair, M., Paulus, M., & Wagner, E. (2021). Activism and radicalism in adolescence: An empirical test on age-related differences. Psychology, Crime & Law, 27(8), 815–830. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2020.1850725

- Raitanen, J. (2021). Deep interest in school shootings online. Academic dissertation. Tampere University Dissertations 361. Tampere: Tampere University. https://trepo.tuni.fi/handle/10024/124428

- Reivich, K., & Shatté, A. (2002). The resilience factor. Broadway Books.

- Richardson, G. E. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 307–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10020

- Rutter, M. (2012). Social Ecologies and Their Contribution to Resilience. In M. Ungar (Ed.), The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice (pp. 13–32). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0586-3_23

- Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

- Sagone, E., De Caroli, M., Falanga, R., & Indiana, M. (2020). Resilience and perceived self-efficacy in life skills from early to late adolescence. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 882–890. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2020.1771599

- Salmivalli, C., & Peets, K. (2018). Bullying and victimization. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 302–321). The Guilford Press.

- Sanders, J., Munford, R., Thimasarn-Anwar, T., Liebenberg, L., & Ungar, M. (2015). The role of positive youth development practices in building resilience and enhancing wellbeing for at-risk youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 42, 40–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.006

- Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. Free Press.

- Shemesh, D., & Heiman, T. (2021). Resilience and self-concept as mediating factors in the relationship between bullying victimization and sense of well-being among adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 26(1), 158–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2021.1899946

- Shi, M., Wang, X., Bian, Y., & Wang, L. (2015). The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between stress and life satisfaction among Chinese medical students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 15(1), 16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0297-2

- Stanley, S., & Bhuvaneswari, G. (2016). Reflective ability, empathy, and emotional intelligence in undergraduate social work students: A cross-sectional study from India. Social Work Education, 35(5), 560–575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2016.1172563

- Steger, M., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

- Stephens, W., Sieckelinck, S., & Boutellier, H. (2019). Preventing Violent Extremism: A Review of the Literature. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 44(4) . https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1543144

- Stephens, W., & Sieckelinck, S. (2019). Being resilient to radicalisation in PVE policy: A critical examination. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 13(1), 142–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2019.1658415

- Taylor, E., A. A., Karnovsky, S., & Karnovsky, S. (2014). Moral Disengagement and Building Resilience to Violent Extremism: An Education Intervention. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 37(4), 369–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.879379

- Theron, L., & Engelbrecht, P. (2012). Caring Teachers: Teacher–Youth Transactions to Promote Resilience. In M. Ungar (Ed.), The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice (pp. 265–280). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0586-3_23

- THL. (2018) National Institute for Health and Welfare. National school wellbeing survey. Available at: https://thl.fi/fi/web/lapset-nuoret-ja-perheet/tutkimustuloksia (accessed 14 April 2020)

- UNESCO. (2017). Preventing violent extremism through education: A guide for policy-makers. E-publication. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247764. Accessed 2 April 2020

- Ungar, M. (2016). The Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM). Child Version. User’s manual. Resilience Resource Centre. https://cyrm.resilienceresearch.org/. (Accessed 15 March 2020)

- Ungar, M., & Liebenberg, L. (2011). Assessing Resilience Across Cultures Using Mixed Methods: Construction of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 5(2), 126–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689811400607

- Vaes, J., Leyens, J.-P., Paladino, M., & Pires Miranda, M. (2012). We are human, they are not: Driving forces behind outgroup dehumanisation and the humanisation of the ingroup. European Review of Social Psychology, 23(1), 64–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2012.665250

- Van Tongeren, D. R., Green, J. D., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., & Hulsey, T. (2016). Prosociality enhances meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1048814

- Vergani, M., Iqbal, M., Ilbahar, E., and Barton, G. (2018). The 3 Ps of radicalisation: push, pull and personal. A systematic scoping review of the scientific evidence about radicalisation into violent extremism. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 43(10), 854–854

- Vinayak, S., & Judge, J. (2018). Resilience and Empathy as Predictor of Psychological Wellbeing among Adolescents. International Journal of Health Sciences & Research, 8(4) , 192–200.

- Weine, S., Ellis, H., Haddad, R., Miller, A., Lowenhaupt, R., & Polutnik, C. (2015). Lessons Learned from Mental Health and Education: Identifying Best Practices for Addressing Violent Extremism. Final report to the Office of University Programs, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Available at: https://www.start.umd.edu/publication/lessons-learned-mental-health-and-education-identifying-best-practices-addressing (Accessed 15 September 2020)

- Womick, J.,Ward, S., Heintzelman, S., Woody, B., S., & King, L. (2019). The existential function of right‐wing authoritarianism. Journal of Personality, 87(5) , 1056–1073. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12457