ABSTRACT

There is growing recognition that young adults of low socioeconomic status are among the loneliest in the United Kingdom. However, there has been a dearth of qualitative research exploring how they cope with their loneliness. Using a novel free association technique, this study sought to explore how young adults (n = 48) in London’s most deprived areas cope with feeling lonely. A thematic analysis, informed by an inductive approach, identified six key themes. Seeking connection, avoidance, seeking support and cognitive strategies were most prevalent. Meaning-focused coping and distraction were also identified, albeit less often. Overall, there were diverse ways of coping within and across respondents and important differences were found between the genders. The findings call for the early identification of those at risk of persistent avoidance behaviours and for interventions that provide meaningful leisure activities, with mutual goals in communities, alongside the strengthening of support and authenticity in relationships.

Introduction

In the United Kingdom, approximately 22% of adults report feeling loneliness always, often or some of the time, reflecting a growing public health concern (Office for National Statistics [ONS], Citation2018). Defined as a distressing state arising from a perceived discrepancy between the quantity or quality of one’s actual and desired social relationships (Perlman & Peplau, Citation1981), loneliness has been associated with depression, anxiety and a range of debilitating physical health outcomes (Cacioppo et al., Citation2015). Although extensively studied in the gerontological literature (Crewdson, Citation2016), it is increasingly evident that the problem of loneliness extends beyond the elderly, with the 16–24-year-old age group most severely affected (ONS, Citation2018). The period of young adulthood is a critical time, during which identity exploration is exercised (Arnett, Citation2000), and vulnerability to mental health disorders is particularly prevalent (Rickwood et al., Citation2015), rendering it paramount to explore how young adults alleviate the distress of loneliness.

It is well-established that loneliness is multidimensional, varying across individuals and situations. The experience of loneliness has been associated with social detachment, rejection, self-alienation, but also growth and self-discovery (Rokach & Brock, Citation1997). Weiss (Citation1973) further elucidated its multifaceted nature by drawing a distinction between emotional loneliness, arising from a perceived absence of intimate relationships, and social loneliness, described as the perceived absence of a social network. Despite burgeoning interest in the qualitative experience of loneliness (Fardghassemi & Joffe, Citation2021), little attention has been devoted to how youth cope with loneliness (Besevegis & Galanaki, Citation2010). In the stress literature, coping is defined as the cognitive and behavioural methods employed to manage aversive internal and external demands, consisting of two higher-order categories: problem-focused coping (strategies that modify the cause of distress) and emotion-focused coping (efforts to allay the emotional effects of stress) (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). These strategies exhibit changes across situational and temporal contexts depending on the perceived level of threat and resource availability (Lazarus, Citation1993). Therefore, qualitative research is particularly well-suited for capturing a nuanced understanding of the ways young individuals cope with loneliness.

Previous research on the management of loneliness has utilized quantitative approaches predominantly. Besse et al. (Citation2021) experimental study revealed how young adults felt more prepared for loneliness after being trained to accept their feelings relative to those who practiced altering their maladaptive cognitions. Additionally, recent surveys in the United Kingdom reveal that severely lonely adolescents report greater self-harm (Yang et al., Citation2020), more compulsive technology use and score higher on ‘negative’ items such as social withdrawal and problem obsession than their less lonely counterparts (Matthews et al., Citation2019). However, both studies’ use of predefined response options limits the breadth of coping strategies that might otherwise be uncovered and fall short of elucidating the feelings and cognitions associated with coping, which can influence future coping intentions (Van Buskirk & Duke, Citation1991). Moreover, the adaptiveness of coping strategies cannot be fully understood when displaced from their contexts; behavioural withdrawal and denial may be helpful in the short-term or in cases when stress is uncontrollable, albeit not in the long-term, as the situation remains unchanged (Ben-Zur, Citation2009). This further emphasizes the necessity for qualitative research to capture the breadth and complexity of coping.

To date, qualitative studies on coping with loneliness in young adults have largely involved the middle-class. Sundqvist and Hemberg (Citation2021) found that positive thinking, social networks and engaging in hobbies were considered important for the alleviation of loneliness among Finnish students. Similarly, Vasileiou et al. (Citation2019) thematic analysis of British undergraduates’ strategies to manage loneliness revealed that distraction, support-seeking and the concealment of loneliness were most commonly described, while escapist strategies such as ‘killing time’ or ‘forgetting’ were uncommon. Nonetheless, the paucity of research on young adults of low socioeconomic status (SES) residing in deprived areas is surprising given that they are one of the loneliest in the United Kingdom (ONS, Citation2018). Disadvantaged individuals not only have fewer financial resources but may have comparatively limited access to social support (Miller & Taylor, Citation2012), which may be particularly problematic as low levels of emotional support are predictive of loneliness (Larose et al., Citation2002). Hence, research on this vulnerable demographic is warranted.

Moreover, researchers have established gender differences in loneliness, although reasons for this have not been clearly identified. Recent studies have reported that women are lonelier than men (ONS, Citation2018), even after controlling for a range of covariates (Luhmann & Hawkley, Citation2016). However, Maes et al.'s (Citation2019) meta-analysis found greater loneliness scores in men than women during young adulthood, although the effect size for this difference was small. While it is possible that such heterogenous results may be due to different loneliness measures and sample demographics employed across studies, it is also plausible that men and women cope differently with their loneliness. For instance, Schultz Jr and Moore (Citation1986) speculated that men are more likely than women to attribute the cause of their loneliness intrinsically to their failures than to external, uncontrollable events. However, this was only inferred from the stronger correlations they found between loneliness, state-anxiety and self-perceived likeability in males relative to their female counterparts. Therefore, qualitative methods may be useful in providing a more nuanced explanation of the ways in which men and women potentially differ in their coping strategies.

The present study thus aims to address the shortcomings of prior research by exploring how disadvantaged young adults cope with loneliness via a thematic analysis of interviews. Distinct from prior qualitative research that explicitly asked about coping strategies (e.g. Vasileiou et al., Citation2019), the current study capitalizes on a novel free association method, ensuring that responses are as naturalistic as possible. The primary research aim was to determine how young adults residing in London’s most deprived boroughs cope with loneliness. The secondary aim was exploratory, seeking to delineate any qualitative differences in the coping process between the genders, if they exist.

Method

Recruitment

Using a professional recruitment agency, 48 British young adults were purposively sampled and received a small monetary compensation for their time. Participants were aged 18 to 24 years, in employment, of low SES and renting in one of London’s most deprived boroughs (Barking and Dagenham, Hackney, Newham, Tower Hamlets), in line with the specific set of characteristics associated with high levels of loneliness at a national level (ONS, Citation2018). Twelve individuals were selected from each borough and an equal number of men and women were recruited in order to achieve gender representativeness in the sample, enabling the coping process to be studied across the genders. Low SES was determined based on the social grade system adopted by the ONS; all participants were in social grades C2DE (see Ipsos, Citation2009). In terms of ethnic composition, 69% identified as Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic, and 31% as White.

Data collection

The study was conducted between May 2019 and August 2019 and comprised two parts, each involving a one-hour interview. A trained interviewer conducted the interviews individually in participants’ homes or an alternative venue of their choice. Prior to study commencement, interviewees were informed that the study’s focus was on their ‘social lives in the city’; the specific topic of loneliness was not revealed to prevent any influence on their responses. Once participants agreed to be audio-recorded and understood their data’s confidentiality, written informed consent was requested. Ethical approval was granted by the UCL Research Ethics Committee (reference number CEHP/2013/500).

A free association task designed to elicit naturalistic cognitions and feelings (Grid Elaboration Method; Joffe & Elsey, Citation2014) formed the basis of each interview. In the first part of the study, participants were instructed to express a word or image they associated with the experience of loneliness in each box of a four-box paper grid (see ). Subsequently, participants were invited to elaborate on the content of their first box (‘can you tell me what you put in box one?’). Follow-up questions (e.g. ‘how does that make you feel’, ‘can you tell me more?’) enabled interviewees to fully expand on their responses. This process was repeated for the rest of the boxes, in chronological order. In the second part of the study, participants expressed a word or image they associated with one location in their neighbourhood where they felt most lonely, and one where they felt most socially connected (see ). This was followed by a detailed elaboration of their grid responses, similar to part one of the study.

On completion of the interviews, participants completed a questionnaire. This included a range of relevant scales including the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, as well as demographic details. This paper draws on the interview data and demographic details only. Participants were then debriefed and provided details of support services, in case further support was necessary. Interviews were subsequently transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Transcribed interviews were imported into Atlas.ti 9, a qualitative data analysis package, which facilitated data management and coding. An inductive approach to thematic analysis, a method of analysing and identifying rich data patterns, was conducted (see Joffe, Citation2012; Braun & Clarke, Citation2020). This was deemed most appropriate for capturing unanticipated facets of coping without being restricted to a priori theory. After an iterative process of transcript reading and note-taking, a preliminary coding frame was developed. Using this coding frame, approximately 10% (n = 5) of the interviews were double coded by the first author and a second coder to compare their primary codes; this technique (see O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020) yielded an inter-rater agreement of 70% and discrepancies were resolved via discussion. Subsequently, interviews were fully coded using a refined coding frame. Finally, codes were grouped into key themes.

Results

Six themes were identified by way of a thematic analysis: 1) Seeking connection; 2) Avoidance; 3) Seeking support; 4) Cognitive strategies; 5) Meaning-focused coping; and 6) Distraction. The themes, along with their respective subthemes are presented in .

Table 1. Themes and subthemes of coping strategies employed by young adults.

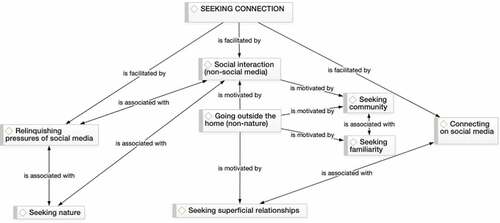

Theme 1: seeking connection

As depicted in , the most prevalent coping strategy among young adults was seeking connection, reported by all interviewees. A distinguishing feature of this theme from the ‘Seeking Support’ theme was the sense of belonging respondents derived from merely interacting with, or placing themselves in the physical presence of others, even in the absence of social, emotional and informational support. The formation of social interactions often involved acquaintances and commonly took place outside the home, driven by a motivation to establish a sense of belonging within communities and seek a sense of familiarity. Similarly, a sense of connectedness was experienced by interacting with a global network of individuals online. However, not all these face-to-face and online interactions were perceived to be fulfiling; participants described how their yearning prompted them to form superficial relationships both online and offline, despite their awareness that these connections were transitory. At times, feelings of alienation in online interactions led individuals to relinquish pressures of social media and seek the physical presence of others in natural environments.

Figure 3. Seeking connection: Thematic map.

Interacting with others in person was perceived as valuable during phases of loneliness, even with those with whom one had no prior social relations. Being able to converse and simply have companionship with those who radiated positive energy was uplifting, promoting a sense of rejuvenation and a ‘boost [of] energy’. This encouraged individuals to become more ‘open’ and ‘genuine’ towards others, as illustrated by one young woman who spoke of how she overcame her loneliness during transitional periods of her life:

You need to make the active effort to get to know people or be a bit more open and friendly … I guess that’s how you would overcome this form of loneliness. (P39: Female, 22, Tower Hamlets)

Often, this process of seeking interaction was motivated by a sense that connecting with others was an integral part of being human; without this, depression, anger and insanity were described as inevitable consequences.

I feel like if you sit indoors all day, you’ll end up driving yourself crazy. (P17: Female, 20, Newham)

These social interactions frequently took place outside the home, driven by a desire to seek a sense of community. For most respondents, youth clubs, religious communities, sports teams and parental groups provided a ‘common goal’ and a feeling that they were all ‘there for the same reason’, fostering a visceral sense of cohesiveness, acceptance and trust amidst diverse cultures and identities. This theme was exemplified by one young man’s experience in the local market:

… I feel connected because I understand that we’ve come from a certain background or a certain part, however, you’ve got here, we’ve all got here at this time, working and experiencing life … (P6: Male, 18, Hackney)

… it’s not like you’re friends … but there’s still something, it makes you feel kind of special, being recognised … it makes you feel like you’re noticed (P12: Female, 22, Hackney)

Apart from local shops, pubs and clubs were frequently mentioned as places sought to alleviate loneliness. One interviewee expressed his satisfaction in knowing that the pub was routinely ‘one place to go so [he] could fill that void of loneliness’ (P43: Male, 23, Tower Hamlets). Described as a place where interactions with strangers were socially acceptable as people were ‘more open’, young adults felt comfortable in gravitating towards strangers who they found relatable in their brokenness.

… there’s a lot of people, people that are in [pubs that] have experienced a lot as in emotional trauma … but when you sit there and speak to them, they are such easy people to get along with … they will sit down and won’t judge you. (P35: Female, 20, Barking and Dagenham)

Likewise, several respondents expressed a sense of connectedness in being able to communicate with a global network of individuals online. Social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat were ‘quick’ and ‘easy’ ways to interact and young adults expressed a sense of power in having the ‘whole world in [their] fingertips’. While some mentioned how social media was a convenient way to keep in touch with geographically distant friends and family, others felt connected when communicating with individuals from all walks of life, reading others’ comments and finding shared interests and perspectives.

… I can just see comments, I can see people who are watching the same thing as me, and I think that’s an easy way to interact with people … anything could happen from there, you can form a friendship. (P8: Male, 18, Newham)

At times, the comparative ease of forging online social connections was a preferred way of connecting with others; for example, one respondent described how she perceived a greater sense of control online than offline, in that she could ‘just log off’ when she felt ‘too far into a situation’ perceived to be uncomfortable, avoid negative ‘impressions’, and ‘choose how long [she wanted] to exist in the social world’ (P37: Female, 19, Barking and Dagenham). Similarly, a few respondents described how social media was used as a crutch when meaningful relationships could not be maintained in reality, or as a way to validate the sense of connectedness they so desired.

I find it guilty to myself that because I didn’t communicate with them for quite a long time, I just avoided them completely. So, what I’ve been doing now, I’m just adding random people on Facebook just to have a communication. (P30: Male, 23, Tower Hamlets)

However, not all face-to-face and online interactions were appraised as meaningful. Some respondents described how their longing for something they could not quite describe drove them to seek superficial relationships to ‘fill [their] void’. Despite the awareness that these relationships were shallow, there was a sense of wishful thinking in ‘kidding [oneself]’ about their authenticity. For example, one young woman mentioned how she constantly hopped from one romantic partner to another solely because she ‘had no one else to talk to’. Often, this restless search for superficial relationships was aimless, and the happiness it brought was only ‘short-term’.

I’ve gone to this area called ‘Old Street’ … tryna fulfil that hole I was talking about earlier, just going to bars, tryna see if I could find some women, try um battle that feeling of loneliness. (P3: Male, 24, Newham)

In addition, almost half the respondents who connected online held ambivalent feelings towards social media, believing that online communication lacked ‘reciprocation on both ends’, differing from ‘real time conversation’. Some interviewees perceived online interactions to lack sincerity and were dubious about whether they were communicating with a ‘genuine’ person. For example, one respondent expressed dismay after relentless efforts to extend his online interactions into the ‘real’ world, building a suspicion that he was communicating with an inanimate ‘robot’ all along. Therefore, several young adults attempted to exercise ‘discipline’ in their use of technology by imposing a ‘cap’.

I’ve been on Tinder with girls and guys and it’s just so painful like I had to delete it after a while … because all you’re doing is forming relationships with people that you’ve never met … it’s just so much nicer to meet someone organically. (P13: Female, 20, Hackney)

These motivations to relinquish pressures of social media sometimes led respondents to seek natural environments such as parks. Due to the lack of technology in these places, they were able to derive enjoyment in the simple pleasures of their immediate surroundings, often embracing the diversity of individuals around them.

I don’t care if we’re not talking but no phones no distractions just us and nature … it’s like going to the park … just looking at other people like children playing on the swings and laughing, you’re connected to that even if you’re not on that swing yourself. (P46: Female, 18, Barking and Dagenham)

Theme 2: avoidance

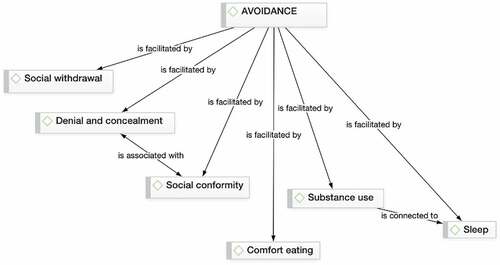

Although seeking connection was frequent, over two-thirds of respondents masked their feelings of alienation and avoided the ‘root cause’ of loneliness. Withdrawing from social situations, denying their loneliness and suppressing their identity-specific values and beliefs helped them manage their emotional distress, albeit leaving the source of the problem unresolved. The use of comfort eating, substances and sleep facilitated their avoidance behaviours. These subthemes and their relationships are illustrated in .

Nearly twice the number of women relative to men described their withdrawal from face-to-face social situations. Withdrawing from social groups was depicted as the ‘easiest’ and ‘comfiest’ way of dealing with loneliness; staying behind ‘the wall’, within their ‘safety barrier’ prevented them from having to worry about others’ negative evaluations, enabling them to be their authentic selves. Around a third of these individuals mentioned their use of technology, including their communications with a ‘virtual friend’, the watching of Netflix, or more generally, being alone ‘on [their] phone’. By entirely avoiding offline social situations, they were able to evade the inconvenience of putting on a ‘certain face’, reducing the salience of their insecurities for the time being.

… you always feel safe and not exposing yourself … at least you’re the only person who can let yourself down … so, just like not exposing yourself and letting other people see your weaknesses. (P12: Female, 22, Hackney)

This was sometimes expressed as a learned response to consistently unmet expectations of support. The feeling of being constantly misunderstood or dismissed led to the idea that there was ‘no point even trying to reach out’ (P7: Female, 18, Newham). Hence, being reserved was a way to prevent the wastage of efforts.

… because they don’t understand why you can be down in front of them and they take it offensively that makes you feel lonely because after a while you’re like, it’s a burden … you don’t want to keep being that. And that sets off more closures within yourself. (P15: Female, 24, Hackney)

Nonetheless, upon reflection, respondents spoke of being ‘trapped’ in a paradoxical situation, where they were ‘comfortable’ being withdrawn, yet at the same time they felt the desire to connect with others, exacerbating their loneliness.

You’re comfortable and you relying on being lonely because you know when you’re on your own, nothing can happen to you but then at the same time it puts you in fear because you feel like you want to be around people. (P37: Female, 19, Barking and Dagenham)

Moreover, there was a sense of resignation to their loneliness; young adults spoke of ‘brush[ing]’ their loneliness ‘under the rug’ and adopting a ‘don’t really care’ mentality until they were ‘ready to explode’. One respondent described how this led to a short-term sense of achievement, although she later resented the ‘things [she] was doing to [herself]’. Common to men, was the perception that loneliness was a sign of vulnerability due to its incongruence with societal expectations of being ‘a man’:

When you feel alone, you’re gonna think ‘I’m not alone’, if you have a strong heart, you ain’t going to cry, you ain’t gonna be sad, but if someone doesn’t have a strong heart … the weak-hearted people … they feel depression, they feel like suicide … (P33: Male, 23, Tower Hamlets)

Closely related to this concealment of emotions was the need to socially conform with others by hiding one’s predicament and identity-specific values and beliefs due to fears of being seen as ‘different’, resulting in a deeper sense of loneliness. One interviewee described how he perceived his suffering to be unwelcome by his friends and was therefore ‘forced to hide it’ due to worries they might ‘stay away’. A sense of belonging was derived from being ‘confirmed’ by others, although this often led to a degradation of self-worth and a questioning of one’s true identity.

… It’s like your views on sexuality, religion … sometimes you just have to tone it down for them … you don’t want to lose your friend. (P46: Female, 18, Barking and Dagenham)

The avoidance of their distress was facilitated by the use of substances and a few participants mentioned how they ‘found [themselves]’ comfort eating because they felt ‘alone’ or because they could not leave their homes. Falling back on the use of drugs and alcohol was sometimes an attempt to ‘sleep [a problem] off’, although these efforts were futile:

Some people need to drink alcohol so they can sleep. To silence their thoughts … It’s like you have damp on your walls. Rather than dealing with the problem outright, paint over it. But after the coating comes off, the damp’s still there. (P23: Male, 23, Hackney)

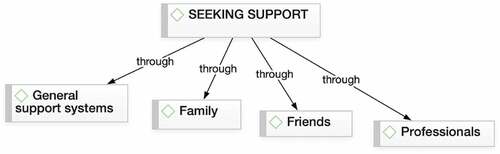

Theme 3: seeking support

Another common theme was seeking support, mentioned by over two-thirds of interviewees. As summarized in , the majority of respondents mentioned how having a general support system or any supportive individual with whom they could ‘offload’ was important. More specifically, informational and emotional support from family, friends and professionals were crucial, although the experiences they had were not always positive.

Interviewees described how having a means wherein thoughts and feelings could be shared made them feel ‘lighter’. Being able to express one’s emotions and thoughts with non-judgemental and understanding individuals helped them realize that their feelings and predicaments were not dysfunctional. This enabled them to be brought ‘back to reality’, recalibrating the severity of their situation.

If a person has someone they are able to relate to, it makes the situation like it has a whole new outlook on a situation … you’re not carrying it a hundred percent by yourself. (P14: Female, 18, Hackney)

The family was often described as the best place to find this support because family members had their ‘best interest’. Beyond informational support, the family provided unconditional care, providing a safe haven with little secrecy and fear of judgment.

Family is the main, it’s a very important thing in life as well … there [sic] will always be there for you no matter how much you done bad or how much you’re good … (P43: Male, 23, Tower Hamlets)

However, the relationship with the family was not always easy, either due to strife within the home, constraints of work, or being limited by money, making it easy for relationships to ‘slip out of [their] hands’. Often, this was expressed with a deep-rooted sense of regret.

… I probably would have continued to go home a little bit more, but because I was so skint, I just kind of got used to not really going back … when that builds up over, you know, almost 10 years, that’s a long time for a relationship to dissolve. (P10: Female, 24, Hackney)

Close friends were perceived as an extension of the family, providing emotional support when the family was not available or when there were familial issues. Nonetheless, several individuals mentioned the need to distinguish between close friends, with whom they could be their authentic selves, and distant friends, where interactions were masked by a pretence that all was well.

… people in the reality, like your family, your actual true friends … they see you at your lows and highs. Whereas the people in your performance only see you in your highs so they think you’re always happy. (P15: Female, 24, Hackney)

Additionally, while some individuals spoke of the importance of support, there were particular problems they were not willing to disclose due to fears of humiliation and perceptions that they might be an unnecessary burden, which only compounded their loneliness.

… there are certain personal things that you can’t go to people … I don’t want to be a burden on someone else … so I just take [my problems] all myself and again that does kind of make me feel lonely. (P7: Female, 18, Newham)

Only a minority spoke of seeking professional support. While three respondents held relatively neutral evaluations of professionals, two respondents’ experiences were diametrically opposed. Although one woman spoke of overcoming a ‘depressed’ period of loneliness with the assistance of a counsellor, another respondent vehemently spoke of how support was desperately lacking in the National Health Service. After being consistently denied the support she needed, she constructed her own way of dealing with distress by adopting traits incongruent with her self-concept:

… if they had given me some help at that point, my situation might not have gone to the point that it did … the way that I kept myself sane [was] by driving myself insane … I’m not built to be an aggressor, I’m definitely not built to be a manipulator … but I had to learn those traits to basically keep myself alive. (P10: Female, 24, Hackney)

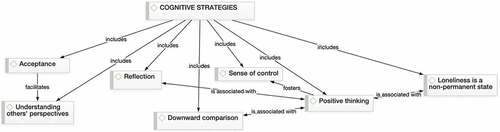

Theme 4: cognitive strategies

Two-thirds of young adults also employed cognitive strategies, including acceptance, understanding others’ perspectives, sense of control and reflection. Reminding themselves of the transient nature of loneliness, replacing negativity with positivity and comparing themselves to those less fortunate also appeared in the data. The nuanced relationships between these subthemes are depicted in .

The majority of respondents accepted their loneliness by reminding themselves of its inevitability in the ‘rat race’ of contemporary society, acknowledging their alienation as a ‘sad circumstance of reality’. Others coped with feelings of loneliness arising from discontentment in relationships by believing that everyone is ‘different in their own little ways’ and reminding themselves of others’ self-sufficiency, prompting them to accept the status of their relationships rather than constructing them based on their unrealistic ideals.

… just kind of accept relationships for what they are, as opposed to trying to develop them too much cause that’s sometimes, well, I found that you can run into problems that way. (P10: Female, 24, Hackney).

The acceptance of loneliness sometimes facilitated their attempts to understand and reframe unhelpful attributions of others’ behaviours. This helped them achieve a sense of resolution, enabling them to become more ‘considerate’ and ‘composed’. For example:

… people have their own things to do and they’ve got places to be and it’s like, you know, it’s not because they personally don’t like you or have a vendetta against you … (P12: Female, 22, Hackney)

Despite the perceived inevitability of loneliness, a sense of control was evident, expressed in over three times the number of men than women. Whilst recognizing the importance of external assistance, many described how the outcome of loneliness was ultimately up to themselves because ‘it’s all about your mindset’, depicting loneliness as a ‘box’ they created for themselves. The need to overcome this barrier was sparked by a realization that ‘life goes on’, that they should ‘carry forward’ and try ‘alternative’ solutions, boosting their optimism. Young adults saw loneliness as residing ‘within oneself’, hence, loneliness could only be dealt with by the individual, and acknowledging this responsibility was essential.

You just gotta get to that point of just being like, ‘okay, you’re lonely’. I’m probably the probable cause of my loneliness and so it’s entirely up to me to stand up. (P16: Male, 24, Hackney)

Albeit effortful and requiring an inner strength, framing loneliness as a challenge was a liberating experience, evoking an image of power: ‘You must get up, lick your wounds, and start all over again.’ (P23: Male, 23, Hackney). However, for a minority this responsibility was driven by the fear of the consequences of inaction and a view that being lonely was ‘pathetic’.

Respondents also engaged in a process of reflection, the majority did so alone, but on rare occasions with trusted others. They emphasized the importance of having a ‘reality check’ in order to understand their emotions and the source of their loneliness. For example, one young man described how he related with the visceral emotions of artists through the ‘lyrics’ or ‘the tone’ of songs to make sense of his complex feelings. This reflective process enabled individuals to ‘see the bigger spectrum of things’, generating plans towards a better trajectory.

… loneliness brings pressure to the mind … but I feel like once you understand, grasp the concept and understand why it is you feel a way you do or why you feel lonely, I feel like it releases this kind of pressure. (P6: Male, 18, Hackney)

In order to reach inner peace and positivity, ruminative thoughts were actively replaced with more hopeful ones that focused on a better future, enabling individuals to believe there was ‘nothing wrong’ with themselves or their situation. This was associated with reminding oneself that loneliness was a natural occurrence in everyday life. By drawing a parallel between loneliness and the ‘way seasons come around’, there was a belief that loneliness, even at its worst, is temporary:

It’s like the waves, the tide, and the ocean … it’s just a natural process of life. (P3: Male, 24, Newham)

Similarly, a few individuals achieved a positive mindset by downplaying the importance of their lonely feelings, believing that dwelling on their loneliness was ‘selfish’ against the backdrop of severe global crises.

It’s not that much of a big deal and there are bigger things in life that people are worried about. (P39: Female, 22, Tower Hamlets)

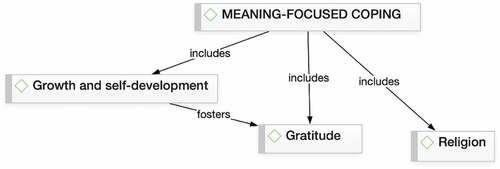

Theme 5: meaning-focused coping

Over half the respondents described the importance of searching for meaning in their lives. This included actively searching for ways to develop the self, grow a deeper sense of gratitude, as well as drawing on religious and existential purpose (see ).

Feelings of emptiness propelled respondents to grow, learn and seek ‘the last bit of freedom’, which was prevalent in over twice the number of men than women, and was associated with a sense of control in approximately a third of the sample. Believing that loneliness happened ‘for a reason’ enabled individuals to conceptualize loneliness as a ‘path’ in a learning curve. Interviewees expressed how focusing on the benefits of loneliness to one’s upbringing, particularly traits of ‘perseverance’, ‘ambition’ and ‘grit’ fostered a deeper sense of self-appreciation, rendering it an integral part of their present-day character.

I don’t see [loneliness] as a bad thing because … whatever I go through by myself, it’s just shaping me and making me into the person that I am today, I feel like I’m a good person, I’m a strong person. (P7: Female, 18, Newham)

Moreover, there was a desire to learn how to deal with loneliness through developing the self and finding one’s ‘role in [the] world’, instilling a sense of existential value. Some individuals achieved this by going the ‘extra mile’, deliberately exposing themselves to divergent ‘morals’, ‘beliefs’ and ‘values’. A few respondents focused on developing skills beneficial to their long-term goals through ‘self-improvement books’ and ‘motivational videos’.

A sense of meaning was also achieved through fostering gratitude for the simple ‘little things that people take for granted’. Focusing on the ‘blessings’ helped them appreciate their own existence, the lives of those around them and provided a sense of satisfaction in reaching certain milestones.

… I try to look at … what positive relationships have I got? … what good things have I got? (P7: Female, 18, Newham)

A minority also commented on how faith helped them through their loneliness. Some conceptualized their loneliness as a ‘trial’ in a ‘temporary world’, externally attributing its cause to ‘the devil’, yet knowing that there was an omnipresent and personal God ‘always with you’ created a sense of security. Loneliness drove respondents to ‘return to God’, ‘do good to one another’ and live their ‘best and most productive lives’. By being reminded of their existential calling, individuals felt a deeper sense of purpose.

… I believe there is a creator and that things have an order … and that we were created for a purpose. (P23: Male, 23, Hackney)

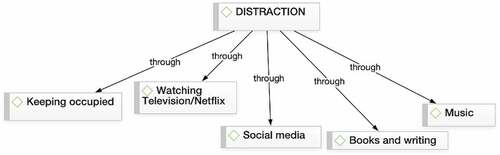

Theme 6: distraction

Fewer than half of the interviewees commented on their use of distraction. Of these individuals, many described how they deliberately kept occupied to redirect their attention away from their feelings. Characteristic of this theme was striving to not only divert one’s attention away from loneliness, as in the ‘Avoidance’ theme, but to redirect it to another activity that they believed would be gratifying or constructive. Watching television, using social media, reading and listening to music were some of the ways this was achieved. These subthemes are summarized in .

Simply keeping the brain occupied by jogging, trying something new and practicing altruism eased them ‘out of [their] head’, shifting their narrow focus of attention away from their selves and their feelings towards their environmental interactions.

I could turn to either a hobby or find something to do, you know, that could have kind of filled my time rather than sit here and feel depressed … (P44: Male, 24, Tower Hamlets)

Respondents also derived a sense of pleasure in being able to vicariously experience others’ lives by deliberately ‘going into the mind’ of characters in films and television shows, similar to the amusement garnered from watching clips and scrolling through ‘inspiring’ posts on social media.

… if I’m lonely, I’ll probably watch other people’s lives and just kind of be happy for them, so it’s like, I substitute my, I don’t even think about myself … (P8: Male, 18, Newham)

Nonetheless, the watching of television and Netflix was often described as a temporary solution, at times creating a sense of guilt from a perception that they had ‘wasted [their] time’ and ‘[had] not achieved anything’. In contrast, reading books, positive quotes and writing enabled young adults to occupy themselves in an activity they considered meaningful.

Every time I feel lonely, I start learning something new. Basically, I’ve got books, self-improvement books … to learn something new, new about people, new about technology, new about everything … (P33: Male, 23, Tower Hamlets)

Likewise, listening to upbeat music, commonly endorsed in women, was perceived as a ‘powerful’ and ‘creative’ way to reverse their downcast feelings, propelling young adults to ‘progress’ through their day in a more positive light.

… I just turn to music … you could feel more happy and look at the world and think, ‘why is it a bit brighter?’ (P6: Male, 18, Hackney)

Discussion

This study is the first to explore the coping strategies young adults of low SES in the United Kingdom deploy to manage their feelings of loneliness using a free association technique. The qualitative data allowed the exploration of nuanced motivations and perspectives richly portraying the coping process. Overall, there was a heterogeneity of coping strategies within and across respondents, consistent with Lazarus and Folkman’s (Citation1984) assertion that multiple coping strategies (both problem-focused and emotion-focused) are often employed to manage stress. Seeking connection and support were commonly endorsed, although many of these individuals also adopted avoidance behaviours and reappraised their situations through acceptance and reflection. The secondary exploratory aim of the study also revealed some important gender differences in the coping process. For many, coping was a complex process, closely tied to the perceived availability of resources, and the appraised meaningfulness and efficacy of their behaviours.

Young adults in the study revealed their efforts to seek connection with diverse individuals in online and offline communities to cope with their loneliness. Similar to lonely undergraduates, social media was sometimes adopted to enhance pre-existing relationships (Thomas et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, distinct from the more middle-class undergraduates, who largely turned to ‘significant others’ (Vasileiou et al., Citation2019), the present sample predominantly established a sense of belonging by seeking familiar yet distant acquaintances in local amenities such as pubs where spontaneous interaction was deemed socially acceptable. This concurs with the results of Child and Lawton’s (Citation2019) quantitative survey purporting an association between young adults’ self-reported social connection and community participation. The findings of this study further extend their results by revealing how it was elements of a common goal, openness and feelings of recognition that young adults found conducive to their sense of interconnectedness. Hence, deriving a sense of belonging with relatable individuals – not only with close ties but also distant others – was valuable.

Nonetheless, contrary to studies positing that the quantity of social relationships is more important than their quality during young adulthood (e.g. Victor & Yang, Citation2012), the present sample highly valued relational intimacy and authenticity. Young adults reported how seeking superficial relationships offline temporarily provided a sense of satisfaction, but ultimately did not quell their loneliness, at times even exacerbating their alienation. Similarly, some online relationships were felt to lack reciprocity, engendering scepticism regarding the existence of their ‘virtual friend’. Although it has been proposed that active social media use (e.g. chatting) is more beneficial for mental health than its passive use (e.g. browsing) (Thorisdottir et al., Citation2019), this study contends that active forms of interaction may at times compound feelings of loneliness when relationships are perceived to lack authenticity.

In addition, while the majority valued emotional and instrumental support from friends and family, many mentioned how they desired more support or believed that their loneliness was irremediable. Gratifying interactions were predominantly discussed, in this study, as providing mutuality, understanding and self-expression, although this was often framed as an ideal. This implies that while their social loneliness was alleviated by seeking communities, there was still a need for emotional intimacy, corroborating Weiss (Citation1973) distinction between social and emotional loneliness. The fact that young adults gravitated towards distant ties to establish a sense of connectedness further reinforces this possibility and is consistent with Watson and Nesdale's (Citation2012) suggestion that those of low SES are inordinately deprived of emotional support. This may pose a problem as it is meaningful contact that is associated with positive wellbeing (Gross et al., Citation2002). Future studies on higher SES groups would be necessary to confirm that the absence of an intimate confidant is unique to those of low SES. In addition, given that cultural influences on relational values and social embeddedness may impact loneliness (Heu et al., Citation2021), cross-cultural replications should examine the influence of the cultural milieu.

The present study also offered novel insights into the adoption of avoidance behaviours. In accordance with prior studies on youth, social withdrawal was highly prevalent (Matthews et al., Citation2019) and the use of substances was identified (Segrin et al., Citation2018). However, extending these findings, a broader range of strategies were uncovered, including denial, social conformity and comfort eating. Importantly, complex motivations behind their choice of coping were uncovered; in terms of social conformity, young adults attempted to maintain a sense of belonging by suppressing their loneliness and identity-specific values, although this was perceived to be antithetical to their desire to be their authentic selves, amplifying their self-estrangement. On the other hand, social withdrawal offered individuals the chance to be genuine by evading their worries about their self-presentation. However, paradoxically, some individuals tacitly weighed the decision to seek out the connection they desired against the ‘safe place’ they had become accustomed to, augmenting the risk of a cyclical process wherein the longer they withdrew, the more likely they were to become ‘trapped’ in their withdrawn state. The use of technology sometimes facilitated their social withdrawal, consistent with the Social Compensation Hypothesis, which posits that lonelier individuals compensate for deficits in offline interactions by growing online networks instead (Bonetti et al., Citation2010). Such compensatory behaviours are concerning as they may increase the risk of chronic loneliness (Nowland et al., Citation2018). This suggests that the entrenched reliance on avoidance strategies may be detrimental to the alleviation of loneliness.

The narratives of young adults also revealed a breadth of cognitive and meaning-focused strategies. Distinct from undergraduates where the acceptance of loneliness was uncommon (Vasileiou et al., Citation2019), a substantial number of young adults perceived loneliness as inevitable due to the rapid pace of contemporary life, similar to the strategies adopted in the elderly (Pettigrew & Roberts, Citation2008). Unique to the literature, symbols in nature depicting the ebb and flow of loneliness, such as the rotation of seasons and tides, enabled individuals to believe that their feelings were transient and commonplace. This inevitability of loneliness was bolstered by the belief that their predicament was ‘a trial’ in a ‘temporary’ life, creating a sense of resolution. While theories of coping with loneliness have been restricted to the ways in which actual and desired levels of social contact can be altered (Peplau & Perlman, Citation1979), it is interesting how young adults in the study also sought out meaning-focused activities and felt lonelier when strategies did not allow self-expression. Notably, young adults used their feelings of longing to develop their self and seek their existential purpose, which was strongly related to a sense of control. These findings are encouraging given that perceptions of control are associated with positive wellbeing (Liu et al., Citation2018) and the discovery of meaning has facilitated psychological adjustment in patients (Park et al., Citation2008). Hence, leveraging meaning-focused loneliness interventions may be a promising area for investigation.

In contrast to the undergraduate population (Vasileiou et al., Citation2019), distraction techniques that served to re-orient attention away from loneliness were less prevalent, which may be due to restricted access to leisure activities among low SES groups (Crawford et al., Citation2008). Considerable evidence has advocated that distraction through leisure boosts positive emotions towards stressful experiences, promoting wellbeing (Carras et al., Citation2018; Patry et al., Citation2007). Nonetheless, the current study illuminated how some pleasurable activities, such as the watching of television, were later appraised to have been unproductive. This highlights the necessity for activities that are appraised as meaningful to facilitate attentional re-shifting, particularly when resources are scarce.

Interestingly, there were differences in coping preferences between men and women, which may explain the reported gender differences in loneliness. Notably, social withdrawal was particularly prevalent in women, perhaps placing them at a heightened risk of chronic loneliness. By contrast, more men than women spoke of having a sense of control, growth and self-development, although it is also plausible that this ascription of control was motivated by pressures to portray an image congruent with gender stereotypes, such as the view that men are more agentic than women (Eagly & Steffen, Citation1984). Indeed, the denial of loneliness in men was motivated by a desire to evade the stigma of being ‘weak’, which was believed to be incompatible with their male identity. Future research would therefore benefit from examining these gender differences more closely.

Implications for practice

The heterogeneity of coping strategies caution against a one-size-fits all approach to loneliness interventions. Interventions have predominantly focused on enhancing social skills and social interaction, yielding small effect sizes (Cacioppo et al., Citation2015). However, while some found social connection to be beneficial, others found it isolating when they perceived their relationships to be shallow. A potential avenue for social interventions would be to focus on promoting mutual support and goals within the community, encouraging the opportunity for open interaction in the neighbourhood and promoting a sense of value and recognition.

There is also a necessity to address emotional loneliness in young adults. Social interventions have often enlisted unknown volunteers to deliver support, with regimented regulations regarding the duration of relationships (Holding et al., Citation2020). Yet, respondents in the present study desired unconditional support from close ties and sought authentic relationships with relatable individuals. Hence, social interventions should allow greater flexibility in the duration of befriending relationships and cultivate friendships based on shared personal histories. Additionally, given that financial limitations were a barrier to the maintenance of relationships, efforts to strengthen familial support should be prioritized by targeting structural factors (e.g. income and educational levels; Hawkley et al., Citation2008).

Moreover, although online resources have increasingly been endorsed to address loneliness (Crewdson, Citation2016), the present findings shed light on the potential danger of using technology in a manner that prolongs social withdrawal, perhaps reducing social skills and heightening interpersonal anxiety in the long-term. However, technological interventions should not be wholly discouraged as social media was capable of fostering a sense of global connectedness and sometimes facilitated relational maintenance. Instead, increasing attention should be placed on helping young adults develop meaningful interactions in online and offline situations. In addition, given that individual differences in one’s sensitivity to rejection has been associated with Facebook usage frequency (Farahani et al., Citation2011) and social withdrawal (Watson & Nesdale, Citation2012), the early identification of those at a greater risk of using social media in a way that perpetuates the avoidance of face-to-face social situations is paramount.

Beyond interpersonal strategies, cognitive methods promoting a sense of control, a belief that loneliness is ‘natural’, and reflection were crucial in helping young adults reach a state of composure. Meaning-focused coping, including faith in God and the belief that loneliness instilled virtues of strength were important in helping individuals derive a sense of purpose. Hence, the watching of motivational videos, reading and writing may be encouraged to facilitate a shift in attentional focus away from the stressor, while fostering a sense of existential purpose.

Reflexive practice

The interviewer was not British born whereas the participants were. This meant that participants, who were from deprived areas, could not place the interviewer in terms of his socio-economic status. This may have allowed them to freely express their experiences. In addition, the free association technique used allowed participants to focus on their own train of thoughts and feelings, which may have meant that they were not fully aware of the interviewer in terms of any demographic, such as gender. Finally, some participants made the assumption that since the interviewer was affiliated to a university, he was highly educated. They mentioned this as a distinguishing feature between the interviewer and themselves. Taken together, these factors may have influenced the content of their interviews.

Limitations

The findings must be considered in light of some limitations. Due to the interviewer-interviewee interaction, it is possible that participants’ loneliness may have been less salient at the time of the interview, perhaps affecting their memory of their coping strategies. For example, one participant mentioned: ‘ … I’m with you, I’m talking, I’m not lonely’. Hence, future research that longitudinally tracks participants’ coping process would be beneficial in determining the types of coping and appraisals that protect against loneliness in the long-term.

It is also worth reiterating that this study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The adoption of avoidance behaviours could be amplified in light of the crisis; with the rise of physical distancing and closures of community facilities, access to support and connection is a challenge (Campbell, Citation2020). Future studies should examine how the coping process evolved during the progression of the pandemic.

Conclusion

The present study painted a rich and nuanced portrait of coping in a sample of disadvantaged young adults residing in deprived areas of London. Coping with loneliness is a complex process, encompassing a range of cognitions, motivations, emotions and behaviours, with the meaningfulness and efficacy of coping strategies exerting a large impact on feelings of loneliness. Young adults utilized a vast coping repertoire and were either tacitly or acutely aware of the extent to which these strategies were helpful for them. Not only did young adults desire a place in their communities, but they also highly valued the quality of relationships and support from close emotional ties. Reminding oneself of the ebb and flow of loneliness, reflecting on one’s emotions and believing that loneliness has a purpose had powerful impacts on young adults’ abilities to display resilience and come to terms with their feelings. The study lends credence to the importance of fostering the view that loneliness is commonplace and at times beneficial, the need for relationships to be strengthened and calls for the identification of individuals at risk of long-term avoidance. Addressing loneliness with tailored interventions that account for individuals’ coping styles is crucial in alleviating loneliness and its impacts on physical and mental health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank UCL’s Human Wellbeing Grand Challenge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hosana Tagomori

Hosana Tagomori holds a BSc in Psychology from the Faculty of Brain Sciences, University College London (UCL) and has worked as a research assistant in the Department of Experimental Psychology, UCL. Her research interests include mental health, loneliness and developmental psychopathology.

Sam Fardghassemi

Sam Fardghassemi is a PhD student in social psychology and a Teaching Fellow at University College London (UCL) in London, UK. His research is on loneliness particularly among young adults in contemporary times. He is interested in how young adults experience loneliness and what causal, or risk factors are associated with their loneliness. Sam is also interested in the role of virtual and physical spaces such as social media and neighbourhood characteristics on loneliness.

Helene Joffe

Helene Joffe is a Professor of Psychology at the University College London (UCL) with research interests in human wellbeing in cities, how people conceptualize various risks and the liveability of cities. She devised the Grid Elaboration Method to elicit people’s conceptualizations and developed a form of systematic thematic analysis to analyse this free associative data. As well as international prize-winning work on risk and wellbeing. She has led a wide range of research projects funded by research councils, including a current large grant funded by the Economic and Social Research Council on resilient recovery from disasters.

References

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

- Ben-Zur,H. (2009). Coping styles and affect. International Journal of Stress Management, 16(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015731

- Besevegis,E., & Galanaki,E.P. (2010). Coping with loneliness in childhood. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 7(6), 653–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620903113306

- Besse,R., Whitaker,W.K., & Brannon,L.A. (2021). Reducing loneliness: The impact of mindfulness, social cognitions, and coping. Psychological Reports, 0033294121997779.https://doi.org/10.117/0033294121997779

- Bonetti,L., Campbell,M.A., & Gilmore,L. (2010). The relationship of loneliness and social anxiety with children’s and adolescents’ online communication. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(3), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0215

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

- Campbell, A. M. (2020). An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports, 2, 100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089

- Carras, M. C., Kalbarczyk, A., Wells, K., Banks, J., Kowert, R., Gillespie, C., & Latkin, C. (2018). Connection, meaning, and distraction: A qualitative study of video game play and mental health recovery in veterans treated for mental and/or behavioral health problems. Social Science & Medicine, 216, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.044

- Child, S. T., & Lawton, L. (2019). Loneliness and social isolation among young and late middle-age adults: Associations with personal networks and social participation. Aging & Mental Health, 23(2), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1399345

- Crawford, D., Timperio, A., Giles-Corti, B., Ball, K., Hume, C., Roberts, R., Andrianopoulos, N., & Salmon, J. (2008). Do features of public open spaces vary according to neighbourhood socio-economic status? Health & Place, 14(4), 889–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.11.002

- Crewdson, J. A. (2016). The effect of loneliness in the elderly population: A review. Healthy Aging & Clinical Care in the Elderly, 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4137/HACCE.S35890

- Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (1984). Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 735. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.735

- Farahani, H. A., Aghamohamadi, S., Kazemi, Z., Bakhtiarvand, F., & Ansari, M. (2011). Examining the relationship between sensitivity to rejection and using Facebook in university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 28, 807–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.147

- Fardghassemi, S., & Joffe, H. (2021). Young adults’ experience of loneliness in London’s most deprived areas. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660791

- Gross, E. F., Juvonen, J., & Gable, S. L. (2002). Internet use and well‐being in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00249

- Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), S375–S384. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.6.S375

- Heu, L. C., Hansen, N., Van Zomeren, M., Levy, A., Ivanova, T. T., Gangadhar, A., & Radwan, M. (2021). Loneliness across cultures with different levels of social embeddedness: A qualitative study. Personal Relationships, 28(2), 379–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12367

- Holding, E., Thompson, J., Foster, A., & Haywood, A. (2020). Connecting communities: A qualitative investigation of the challenges in delivering a national social prescribing service to reduce loneliness. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(5), 1535–1543. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12976

- Ipsos. (2009). Social grade: A classification tool. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/publication/6800-03/MediaCT_thoughtpiece_Social_Grade_July09_V3_WEB.pdf

- Joffe, H., & Elsey, J. W. (2014). Free association in psychology and the grid elaboration method. Review of General Psychology, 18(3), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000014

- Joffe, H. (2012). Thematic Analysis. In Qualitative Research Methods. Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners, (pp. 210–223). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781119973249.ch15

- Larose, S., Guay, F., & Boivin, M. (2002). Attachment, social support, and loneliness in young adulthood: A test of two models. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(5), 684–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202288012

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1993). From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology, 44(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245

- Liu, M., McGonagle, A. K., & Fisher, G. G. (2018). Sense of control, job stressors, and well-being: Inter-relations and reciprocal effects among older US workers. Work, Aging and Retirement, 4(1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw035

- Luhmann, M., & Hawkley, L. C. (2016). Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Developmental Psychology, 52(6), 943. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000117

- Maes, M., Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Goossens, L. (2019). Gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan: A meta–analysis. European Journal of Personality, 33(6), 642–654. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2220

- Matthews, T., Danese, A., Caspi, A., Fisher, H. L., Goldman-Mellor, S., Kepa, A., Moffitt, T. E., Odgers, C. L., & Arseneault, L. (2019). Lonely young adults in modern Britain: Findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 49(2), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718000788

- Miller, B., & Taylor, J. (2012). Racial and socioeconomic status differences in depressive symptoms among black and white youth: An examination of the mediating effects of family structure, stress and support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(4), 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9672-4

- Nowland, R., Necka, E. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2018). Loneliness and social internet use: Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617713052

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Office for National Statistics. (2018). Loneliness - what characteristics and circumstances are associated with feeling lonely? Analysis of characteristics and circumstances associated with loneliness in England using the Community Life Survey, 2016 to 2017.

- Park, C. L., Edmondson, D., Fenster, J. R., & Blank, T. O. (2008). Meaning making and psychological adjustment following cancer: The mediating roles of growth, life meaning, and restored just-world beliefs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 863. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013348

- Patry, D. A., Blanchard, C. M., & Mask, L. (2007). Measuring university students’ regulatory leisure coping styles: Planned breathers or avoidance? Leisure Sciences, 29(3), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400701257963

- Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (1979, June). Blueprint for a social psychological theory of loneliness. Love and attraction: An interpersonal conference (pp. 101–110). Pergamon Press.

- Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Personal Relationships (pp.31–56). London: Academic Press.

- Pettigrew, S., & Roberts, M. (2008). Addressing loneliness in later life. Aging and Mental Health, 12(3), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802121084

- Rickwood, D. J., Mazzer, K. R., & Telford, N. R. (2015). Social influences on seeking help from mental health services, in-person and online, during adolescence and young adulthood. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0429-6

- Rokach, A., & Brock, H. (1997). Loneliness and the effects of life changes. The Journal of Psychology, 131(3), 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223989709603515

- Schultz Jr, N. R., & Moore, D. (1986). The loneliness experience of college students: Sex differences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12(1), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167286121011

- Segrin, C., McNelis, M., & Pavlich, C. A. (2018). Indirect effects of loneliness on substance use through stress. Health Communication, 33(5), 513–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1278507

- Sundqvist, A., & Hemberg, J. (2021). Adolescents’ and young adults’ experiences of loneliness and their thoughts about its alleviation. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 26(1), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2021.1908903

- Thomas, L., Orme, E., & Kerrigan, F. (2020). Student loneliness: The role of social media through life transitions. Computers & Education, 146, 103754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103754

- Thorisdottir, I. E., Sigurvinsdottir, R., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2019). Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(8), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0079

- Van Buskirk, A. M., & Duke, M. P. (1991). The relationship between coping style and loneliness in adolescents: Can “sad passivity” be adaptive? The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 152(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1991.9914662

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Barreto, M., Vines, J., Atkinson, M., Long, K., Bakewell, L., Lawson, S., & Wilson, M. (2019). Coping with loneliness at University: A qualitative interview study with students in the UK. Mental Health & Prevention, 13, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2018.11.002

- Victor, C. R., & Yang, K. (2012). The prevalence of loneliness among adults: A case study of the United Kingdom. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.613875

- Watson, J., & Nesdale, D. (2012). Rejection sensitivity, social withdrawal, and loneliness in young adults. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(8), 1984–2005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00927.x

- Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation.

- Yang, K., Petersen, K. J., & Qualter, P. (2020). Undesirable social relations as risk factors for loneliness among 14-year-olds in the UK: Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 0165025420965737. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025420965737