ABSTRACT

This research aimed to investigate the relationship between stressful life events, trauma, and psychiatric symptoms with psychological resilience as mediator and self-esteem as moderator effects in Syrian adolescents. A total of 1045 Syrian adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years completed the Stressful Life Events Questionnaire, Child and Youth Resilience Measure, Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale, Traumatic Stress Response Scale for Adolescents, and Hopkins Symptom Checklist-37A for Adolescents Scale. The study showed that resilience and self-esteem mediated the relationships between the stressful life events and traumatic stress and anxiety, depression, and externalization. Resilience also had a moderator effect on the relationships between stressful life events – traumatic stress response, and stressful life events-depression. The author suggests that resilience and self-esteem play an important role to understand the relationship between stressful life events, trauma, and psychiatric symptoms in Syrian adolescents.

Introduction

Syrian civil war starting in 2011 forced more than half (approximately 23 million people) of the Syrians to flee their country. Statistics published by the General Directorate of Migration Management (Citation2020) in Turkey showed that there are 3,579,008 Syrian refugees in Turkey in 2020. Since Syrian civil war, Turkey has been the host country for the Syrian migrants (UNHCR, Citation2018), and more than half of this population are children and adolescents exposed to mass trauma. A recent research (Görmez et al., Citation2017) showed that Syrian refugee children and adolescents aged 9–15 years attending a temporary education centre in Turkey reported that 56.2% of them lost a loved relative, 70.4% of them witnessed dead or injured people, 70.4% of them experienced explosions and wars, 42.5% of them witnessed the torture, 25.6% of them experienced torture and bullying. Also, the prevalence of (post-traumatic stress disorder) PTSD was found to be 18.3% and the rate of anxiety-related disorders was found 69% (Görmez et al., Citation2017).

American Psychological Association (APA, Citation2022) defines trauma as ‘an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, rape or natural disaster.’ Denial and shock are common symptoms following a traumatic event. Individuals, who experience traumatic events, may have difficulties to function properly in their day-to-day lives (APA, Citation2022). Studies on Syrian refugee adolescents suffering from the distressing event and their related mental problems are relatively limited. Available evidence on Syrian children living in refugee camps in Turkey found a significant association of physical and psychosocial problems of refugee children living in refugee camps with PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorder (Yayan et al., Citation2020). Similarly, more than 44% of children and adolescents living in Syrian refugee camps in Turkey showed signs of depressive symptoms, with girls being more depressive than boys (Sirin & Rogers-Sirin, Citation2015). These results highlight the importance of understanding the link between traumatic events and mental health problems of adolescents.

Adolescents with traumatic experience tend to face with lifelong challenges (McGrath & Kovacs, Citation2019). Psychological resilience, also known as resilience, may help adolescents to cope with challenges. Psychological resilience refers to an individual ability to cope with adversity or challenges in ways that may contribute to quality of life and well-being. Resilience is found to be associated with better psychological and physical outcomes, and resilient people tend to report more positive feelings and have better physical and psychological functioning (McGrath & Kovacs, Citation2019). Mediating and moderating roles of resilience have been primarily studied in the context of Western countries. For example, a 5-year longitudinal study conducted on adolescents with depressive symptoms found that psychological resilience moderated the relationship between violent life events and suicide attempts (Nrugham et al., Citation2010). Researchers also found that psychological resilience had a moderator effect in the relationship between perceived stress and symptoms of binge eating (Thurston et al., Citation2018). Mediating role of resilience in the association between posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth has also been established (Lee et al., Citation2020). However, most studies in this regard have been reported from western countries. Only a few studies have focused on the mediator and moderator effects of resilience in the relationships between stressful life events and traumatic stress response, anxiety disorder, and depression in non-western cultures. Evidence from non-western countries (e.g. Anyan & Hjemdal, Citation2016) showed that resilience partially mediated the stress–anxiety disorder relationship and stress–depression relationship. Also, resilience moderated the effect between stress and depression, but not the effect between stress and anxiety. This result suggests the importance of psychological resources like resilience or psychological resilience in mitigating the impact of distressing events on mental health outcomes. Therefore, understanding the relationships between stressful life events-traumatic stress response, stressful life events-depression, stressful life events-anxiety and stressful life events-externalization in Syrian adolescents’ refugees in Turkey and determining mediating and moderating roles of resilience and self-esteem on these relationships will provide further insights into this topic and substantially contributes to relevant literature from a non-western society.

Stressful life events have usually been associated with mental health problems. Individual difference factors like self-esteem are found to reduce the impact of stressful life events on psychological problems (De Moor et al., Citation2019). Self-esteem is defined as subjective evaluation of individuals’ negative and positive attitudes towards the self under a wide range of circumstances (Rosenberg, Citation1965). A person with poor self-esteem may excessively concentrate on losses, and failures rather than success and achievement (Baumeister et al., Citation1989). Earlier research highlighted the importance of self-esteem in the association between stressful life events and mental health problems (De Moor et al., Citation2019). Self-esteem was related to internalizing and externalizing problems (Luk et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, self-esteem was found to be linked with poor symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and affect disorders (Nima et al., Citation2013) and traumatic stress disorders (Zhou et al., Citation2018). Therefore, this study took mediating and moderating role of self-esteem into account to examine the relationship between stressful life events and psychological health problems.

Research aims

As described earlier, although there is evidence on moderating role of resilience in the relationship between the aforementioned variables, it is not yet known whether resilience will be a mediator in some situations. According to Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), moderator variables are likely to act as mediator variables. In existing literature, evidence is also limited regarding the simultaneous roles of resilience and self-esteem acting as buffering effects between stressful life events and psychological symptoms. Therefore, the present study sought to examine mediating and moderating roles of resilience and self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events and traumatic stress response, depression, anxiety, and externalization in Syrian adolescent refugees. To the best of our knowledge, this topic has not yet been studied in the relevant literature. Based on the research aim, we therefore hypothesized that resilience and self-esteem would mediate and moderate the relationship between stressful life events and traumatic stress response, depression, anxiety, and externalization.

Method

Design and procedure

An exploratory quantitative research design guided the cross-sectional sampling method to recruit adolescents from a diverse group of schools in Turkey. The selection of the research design was based on the strengths of established quantitative methods, allowing a flexible adoption of method. As a part of dissertation research project, cross-sectional data was collected between May 2020 and June 2021. Before data collection held in the school settings, ethical approval was received from an university ethics committee and the regional school authority board. Relying upon convenience sampling, public schools in Turkey were approached and invited to take part in the research. The schools that had voluntarily agreed to take part in the research were requested to send a letter with a link to parents regarding participating in the study. The letter included an informed consent form for parents and adolescents, and involvement in the study was completely voluntarily. Participants were assured about the anonymity and confidentiality of responses following obtaining written and verbal consent from parents and adolescents who wanted to participate. Bilingual translators, who were trained to explain the constructs of this study, were utilized to explain the items to Syrian adolescents in case that they did not clearly understand the questions. The completion of the questionnaires took approximately 30 minutes.

Participants

Participants included 1,045 Syrian adolescents whose ages ranged between 12 and 18 years with a mean age of 15 years (SD = 1.34). . Approximately 51% of participants were females, and 49% were males. Of the sample, 59.2% of participants attended school and 40.8% (n = 435) of them did not attend school. They reported that 16.4% of them could speak Turkish at a low level, 44.3% of them could speak Turkish at a moderate level, and 39.3% of them could speak Turkish at a good level. Approximately 27% of participants were employed, and 72.9% were unemployed. Additionally, 22% of participants lost their fathers, and 2% of them lost their mothers. The average time of arrival of adolescents in Turkey was 4.42 years before conducting the study in 2020.

Measures

Stressful Life Events (SLE)

Stressful Life Events (Bean et al., Citation2006, Citation2004) were developed to measure traumatic experiences such as war, natural disaster, separation from family, and physical or sexual violence. The SLE consists of 12 items with yes/no dichotomous format and is divided into five sub-dimensions: i) stressful life events related to the family, ii) natural disaster, accident, and illness, iii) war, iv) physical or sexual violence, and v) other traumatic experiences

Psychological resilience (CYRM-12)

The short form study of the Psychological Resilience Scale (CYRM-12; Liebenberg et al., Citation2013) is a 12-item self-reported measure developed to assess psychological resilience. Each item on the scale is rated on a 5-point Likert-style ranging between 1 = Does not describe me at all and 5 = Describes me completely. A high score indicates a high level of psychological resilience. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.83.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSS)

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is a 10-item Likert-style self-report scale developed to measure overall self-esteem (Rosenberg, Citation1965) Each item is rated using a 4-point Likert type ranging between 3 = very true and 0 = very wrong. A high score indicates a high level of self-esteem. The scale has been translated both in Turkish (Çuhadaroğlu, Citation1986) and Arabic (Abdel-Khalek, Citation2012; Kazarian, Citation2009; Zaidi et al., Citation2015) and showed good evidence of reliability and validity. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.85.

Traumatic stress response scale for adolescents (RATS)

The RATS is developed based on 17 symptoms in the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorders (Bean et al., Citation2004a) and was used to assess adolescents’ traumatic experiences. The RATS consists of 22 items, which are grouped into three sub-scales: intrusive thinking (6 items), avoidance (9 items), and hyperarousal (7 items). The RATS is formed Each item is rated based on a 4-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 = not a lot to 4 = too much. Sample items are ‘I have bad dreams or nightmares about events’, ‘I do not feel close to the people around me’. The items in the scale were written in both English and another language (e.g. Arabic). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.89.

Hopkins Symptom Checklist-37A (HSCL-37A)

Hopkins Symptom Checklist-37A (Bean et al., Citation2006) was used to assess the psychiatric symptoms. There were 25 items for internalizing symptoms (15 depression, 10 anxiety) and 12 items for externalizing symptoms in HSCL-37A. The checklist consists of 37 items rated on a Likert type scale ranging from 1 = none to 4 = a lot, with a higher score indicating greater psychiatric symptoms. Sample items include ‘I am afraid’, ‘I cry easily’, ‘I argue often’, and ‘I have a low appetite.’ In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.91 for the overall scale, 0.88 for anxiety, 0.89 for depression, 0.90 for internalization, and 0.65 for externalization.

Data analysis

Generalized Linear Model mediation analysis was used to conduct the mediation analysis. For this analysis, the confidence interval (CI) was estimated using 1,000 resampling with the bootstrap method. Hayes’s (Citation2018) Model 1 and 2 were used in the moderator analyses by controlling for age and gender. The R and Jamovi were used for other analyses and visualizations. The PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 24) was used for moderator by controlling for age and gender.

Research model

Generalized Linear Model mediation analysis was used to examine the proposed model in which stressful life events were considered as an independent variable, resilience and self-esteem were considered as mediator variables, and traumatic stress response, depression, anxiety, and externalization were considered as dependent variables. The direct effects of self-esteem and psychological resilience on traumatic stress response, anxiety, depression, and externalization were examined separately in the model. Also, the mediator effects of resilience and self-esteem in the relationships between stressful life events-traumatic stress response, stressful life events-depression, stressful life events-anxiety, and stressful life events-externalization were examined (see, ).

Figure 1. Model examines the mediator role of psychological resilience and self-esteem in the effect of stressful life events on traumatic stress response, anxiety, depression, and externalization.

The moderator effects of resilience and self-esteem in the relationships between stressful life events-traumatic stress response, stressful life events-anxiety, stressful life events-depression, stressful life events-externalization were examined by controlling gender and age in the second step of the analysis. Continuous variables in all moderator analyses were centralized before the analysis (see, )

Results

Mediator analysis

Multiple parallel mediation analysis was firstly conducted to examine the mediating effects of psychological resilience and self-esteem in the relationship between the effect of stressful life events and traumatic stress response. Stressful life events significantly predicted resilience (β = −0.25, p < 0.001), self-esteem (β = −0 .27, p < 0.001), and traumatic stress response (β = 0.33, p < 0.001). Resilience (β = −0.25, p < 0.001) was also associated with self-esteem (β = −0.25, −1.49, p < 0.001) also significantly predicted the traumatic stress response. The impact of stressful life events on traumatic stress response through resilience (β = 0.06, p < 0.001) and on self-esteem (β = 0, 07, p < 0.001) was statistically significant.

Multiple parallel mediation analysis was secondly conducted to examine the mediator effects of psychological resilience and self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events and anxiety. The direct effect of stressful life events on anxiety was significant (β = 0.28, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of stressful life events on anxiety through resilience (β = 0.04, p < 0.001) and self-esteem (β = 0.06, p < 0.001) was statistically significant.

Multiple parallel mediation analysis was thirdly conducted to examine the mediator effects of psychological resilience and self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events on depression. The direct effect of stressful life events on depression was significant (β = 0.27, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of stressful life events on depression through resilience (β = 0.05, p < 0.001) and self-esteem (β = 0.09, p < 0.001) was significantly significant.

Finally, multiple parallel mediation analysis was carried out to investigate the mediator effects of resilience and self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events and externalization. The direct effect of stressful life events on externalization was significant (β = 0.24, p < 0.001).The indirect impact of stressful life events on externalization through resilience (β = 0.05, p < 0.001) and self-esteem (β = 0.04, p < 0.001) was statistically significant. The results of mediation analyses are presented in and .

Figure 3. Summary of the proposed model of all analyses testing the mediator role of psychological resilience and self-esteem on the effect of stressful life events on traumatic stress response, anxiety, depression, and externalization.

Table 1. Mediator analyses

Regulatory and covariance regulatory analysis

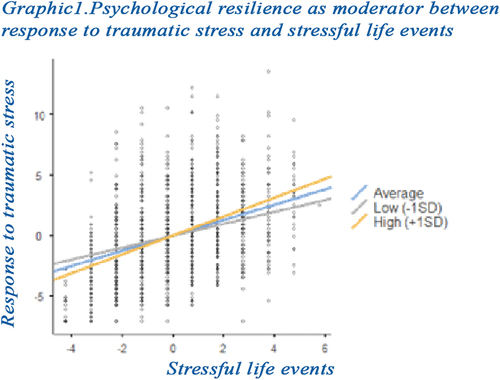

The impacts of stressful life events (B = 0.63, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (B = −2.29, p < 0.001), on the traumatic stress response were significant. Resilience moderated the effect of stressful life events on traumatic stress response (B = 0.23, p = 0.036). The moderator effect was observed at high (+1 SD) (B = 0.49, p < 0.001) moderate (0 SD) (B = 0.63, p < 0.001), and low (−1 SD) (B = 0.77, p < .000) levels of psychological resilience. These results suggest that the relationship between stressful life events and traumatic stress response is weaker at higher levels of psychological resilience. Furthermore, gender (0 = female, 1 = male) and age were included in the model as covariates. Gender showed a significant effect on traumatic stress response (B = −0.98, p < 0.001), while age did not indicate a significant effect. The effects of age and gender did not change for stressful life events (B = 0.67, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (B = −2.30, p < 0.001) which showed significant main effect.

The moderator effect of resilience was observed in the relationship between stressful life events and traumatic stress response (B = 0.19, p = 0.004). The moderation effect was observed at all levels of resilience: high (+1 SD) (B = 0.54, p < 0.001), moderate (0 SD) (B = 0.67, p < 0.001), and low (−1 SD) (B = 0.79, p < 0.001) and this was similar to the model in which the confounding variables were not controlled for (see, ).

There was no moderator effect of self-esteem on the effect of stressful life events on traumatic stress response (B = 0.10, p = 0.091). Age and gender were controlled for. The pattern did not change in this model even when confounding variables (i.e. age and gender) were controlled for. Also, there was no moderator effect of self-esteem on the effect of stressful life events on the traumatic stress response in the model without confounding variables (B = 0.08, p = 0.09).

Moderation analysis was conducted to examine the moderator effects of psychological resilience and self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events and anxiety. The main effects of stressful life events (B = 0.67, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (B = −2.30, p < 0.001) on anxiety were significant. However, there was no moderator effect of resilience in the relationship between stressful life events and anxiety (B = 0.21, p = 0.077). The analysis was repeated for confounding variables (i.e. age and gender) which produced significant effect on anxiety: gender (B = −1.96, p < 0.001) and age (B = −0.21, p = 0.028). The pattern of results did not change when confounding variables were controlled for. The main effects of stressful life events (B = 0.75, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (B = −2.32, p < 0.001) on anxiety were significant. However, psychological resilience did not have a moderator effect in the relationship between stressful life events and anxiety (B = 0.15, p = 0.097) without confounding variables.

There was no moderator effect of self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events and anxiety with (B = 0.17, p = 0.092) and without (B = 0.14, p = 0.764) confounding variables of age and gender.

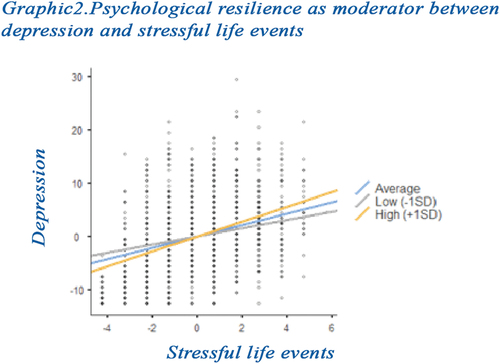

The moderation analysis was repeated to examine the effect of psychological resilience and self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events and depression. The results produced significant results for the main effects of stressful life events (B = 1.07, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (B = −4.66, p < 0.001) on depression. Resilience had a moderator effect in the relationship between stressful life events and depression (B = 0.49, p = 0.019). The moderator effect was significant at high (+1 SD), moderate (0 SD), and low (−1 SD) levels of psychological resilience in the relationship between stressful life events and depression. However, the relationship between stressful life events and depression become stronger from high level of psychological resilience (+1 SD) (B = 0.76, p < 0.001), moderate (0 SD) (B = 1 .07, SD. = 0.10, p < 0.001) to low (−1 SD) (B = 1.38, p < 0.001). In other words, the relationship between stressful life events and depression weakened when psychological resilience level was increasing. A significant confounding effect of gender on depression was found (B = −4.37, p < 0.001), with no significant effect of age. The main effects of stressful life events (B = 1.20, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (B = −4.57, p < 0.001) on depression were still significant when controlling for confounding variables. The moderator effect of psychological resilience was observed in the relationship between stressful life events and depression (B = 0.38, p = 0.005) at high (+1 SD) (B = 0.96, p < 0.001) moderate (0 SD) (B = 1.20), p < 0.001), and low (−1 SD) (B = 1.44, p < 0.001) without confounding variables (see, ).

There was not a moderator effect of self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events and depression (B = 0.08, p = 0.10) even when controlling for age and gender.

Moreover, moderation analysis was conducted to examine the moderator effect of resilience and self-esteem in the relationship stressful life events externalization. The main effects of stressful life events (B = 0.34, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (B = −1.37, p < 0.001) on externalization were statistically significant. The analysis failed to produce evidence regarding the moderator effect of psychological resilience in the relationship between stressful life events and externalization (B = −0.007, p = 0.918). In this model, gender yielded a significant effect on the externalization (B = 0.60, p < 0.001), while age failed to indicate significant evidence. The main effects of stressful life events (B = 0.32, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (B = −1.37, p < 0.001) on externalization were still statistically significant after controlling for age and gender. However, resilience did not have a moderating effect in the relationship between stressful life events and externalization (B = 0.006, p = 0.908) in the model without confounding variables.

Self-esteem was not a moderator in the relationship between stressful life events and externalization (B = 0.05, p = 0.91) even after controlling for age and gender as confounding variables. There was no moderator effect of self-esteem in the association between stressful life events and externalization in the model without confounding variables (B = 0.06, p = 0.907). The findings regarding moderation analysis are presented in , and .

Figure 4. Summary of the proposed model of all analyses testing the regulatory role of resilience in the effect of stressful life events on traumatic stress response, anxiety, depression, and externalization.

Figure 5. Psychological resilience as moderator between response to stressful life events and traumatic stress response.

Table 2. Regulatory analysis for resilience

Table 3. Regulatory analysis for self-esteem

Discussion

This aimed to examine mediating and moderating roles of resilience and self-esteem in the relationship between stressful life events and traumatic stress response, depression, anxiety, and externalization in Syrian adolescent refugees. The research questions were considered in succession, and the findings were related to the literature on the associations between stressful life events and mental health problems. The findings are discussed in detail below.

The results of this study firstly showed that stressful life events negatively predicted resilience and self-esteem. These results are consistent with those of previous studies (Julian et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2020). Accumulating evidence indicated that traumatic experiences in children and adolescents affected by war increase the probability of experiencing psychological problems (Werner, Citation2012), and negative consequences of traumatic experiences increase in the dose-effect of cumulative trauma (Braun-Lewensohn et al., Citation2009). Adolescents’ reactions to stressors have an impact on their level of self-esteem (Kliewer & Sandler, Citation1992). Young people who have higher levels of self-esteem can effectively use problem-focused strategies in coping with chronic or unpredictable stressors (Connor-Smith et al., Citation2000). Of the levels of stressful life events experienced by children and adolescents, increases are associated with the likelihood of negative consequences.

Stressful life events and mental health

The results of the current study showed that stressful life events positively predicted traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety. These results are in accordance with previous findings. A large-scale study indicated that personal and social stressful life events had significant positive impacts on psychological distress, depression, and anxiety (Dumont & Provost, Citation1999; Hammen, Citation2005; Harkness et al., Citation2006; Hassanzadeh et al., Citation2017; Plancherel et al., Citation1992). Stressful life events were also found to be associated with child and adolescent psychiatric disorders including conduct problems, major depressive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, dysthymia, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, social phobia, and agoraphobia (Tiet et al., Citation2001). Also, the findings of this study indicated that stressful life events positively predict externalization. This study confirms the existing findings about the positive link between stressful life events and externalization (Bean et al., Citation2007; Nielsen et al., Citation2008). However, it is important to note that there is a reciprocal relationship between stressful life events and externalization, meaning that engagement in externalization behaviours can also lead to stressful life events (Kim et al., Citation2003).

Mediating and moderating roles of resilience and self-esteem

Stressful life events significantly predicted externalization through psychological resilience and on self-esteem. In other words, psychological resilience and self-esteem had mediator effects in the relationships between stressful life events and externalization. There is only limited research that examines the simultaneous effects of psychological resilience and self-esteem in the stressful life events – externalization relationships. Gomez and McLaren (Citation2007) found that self-esteem had a mediator effect in the relationship between father attachment-aggression and mother attachment-aggression. Although this finding was not directly related to the mediator effects of resilience and self-esteem in the stressful life events-externalization relationship, it relatively provided support for the findings of this study. Also, the findings of this study supported the moderator effect of psychological resilience in the relationships between stressful life events-traumatic stress response and stressful life events-depression, there was no significant moderator effect of resilience on stressful life events-anxiety and stressful life events-externalization relationship. Besides, moderator effects of self-esteem on stressful life events-traumatic stress response, stressful life events-depression, stressful life events-anxiety, and stressful life events-externalization relationships were not found to be significant.

The current findings demonstrated a moderator effect of psychological resilience in the relationship between stressful life events and traumatic stress response. The moderator effect of psychological resilience in the relationships between stressful life events and traumatic stress response has not been tested in the literature. A positive significant relationship was found between stressful life events and the traumatic stress response at high, average, and low levels of psychological resilience. However, the relationship between stressful life events and traumatic stress response has weakened as the level of psychological resilience increased. Therefore, these findings suggest that when the levels of psychological resilience increase, the probability of developing post-traumatic stress disorder may decrease following exposure to stressful life events. These results are consistent with the findings of previous research regarding the moderating roles of resilience in relation to various variables (Nrugham et al., Citation2010; Thurston et al., Citation2018).

Symptoms of anxiety disorder occur in adolescents who experience life events such as war and natural disasters. The rate of anxiety disorder in children and adolescents affected by the war was found to be 27% (Attanayake et al., Citation2009). The findings of our study are consistent with the extant literature. The present findings showed that the relationships between stressful life events-anxiety and resilience-anxiety were strong in Syrian adolescents, even after controlling for age and gender. However, in this study, there was no moderator effect of self-esteem in the effect of stressful life events between anxiety. Self-esteem mediated the relationship between stressful life events and anxiety. Several studies have focused on the mediator and moderator effects of self-esteem in different contexts. For example, Haine et al. (Citation2003) reported that self-esteem mediated the relationship between negative life events and internalization symptoms in children who lost one of his/her parents. Our findings are in line with this previous finding.

Moreover, in this study, the analysis was repeated by setting gender and age as confounding variables in the model. The results indicated that self-esteem did not show a moderator effect in the relationships between stressful life events and depression as in the model without confounding variables. The main effects of both stressful life events and psychological resilience on externalization were significant. Researchers have reported that externalization symptoms are more common in males and increase with age in immigrant children and adolescents (Bean et al., Citation2007; Nielsen et al., Citation2008). Dumont and Provost (Citation1999) also state that externalizing behaviours are more common in vulnerable adolescents (high stress and depressive symptoms) compared to resilient adolescents (high stress and low depressive symptoms). The possible link between psychological resilience and externalization symptoms has been documented in the relevant literature. The current findings regarding the main effect of stressful life events on externalizing symptoms are in accordance with earlier research. The first direct finding on this issue in immigrant adolescents was obtained in this study. This finding held true after controlling for age and gender. Only gender had a confounding effect on externalization.

Limitations

The present findings should be interpreted with the several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of this research restricts the causal conclusion among the variables. Therefore, a great attention should be paid when interpreting the results of mediation and moderation analyses, which solely rely on cross-sectional design. Longitudinal research design should be conducted to partly address this limitation. Second, this study exclusively relied on participants’ self-reports, which may lead to inflation of the correlations among the analysed study variables. For instance, participants could have answered questions with a tendency to overreport or underreport socially desirable attitudes. Future research is encouraged to verify our results utilizing multi-informant or multi-method assessment.

Implications

Despite these limitations, the current results have the following implications for future research and interventions. Firstly, researchers, mental health practitioners, and policymakers need to focus on prevention of mental disorders by paying a particular attention to psychological resources such as resilience and self-esteem. Secondly, resilience and self-esteem could facilitate to mitigate the impacts of stressful life events on the mental health problems of adolescents. Thirdly, based on evidence-based psychological therapeutic approaches, strategic intervention and effective planning for psychological first aid in the face of stressful life events should be taken into account by stakeholders. Such intervention programmes can be delivered both face-to-face and online using social media sites, which are convenient, fast, and cost-effective methods in disseminating the interventions to adolescents. Finally, it would be useful to teach adolescents ways of developing psychological strengths that buffer the stressful life events on their psychological health.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this research advance the extant literature by presenting showing that positive psychological resources, strengths, and capabilities such as resilience and self-esteem are primary ingredients in promoting positive psychological health in the face of adverse life events in Syrian refugee adolescents. The present results can be used to develop and apply effective and efficient interventions to deal with difficulties of stressful life events.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Onat Yetim

Onat Yetim is a child and adolescent mental health psychiatrist, department of child and adolescence mental health at Dr. Ersin Arslan research and educational hospital in Gaziantep, Turkey. He graduted at Hacettepe University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in 2021. His research interests include children, adolescent, and youth mental health.

References

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2012). Associations between religiosity, mental health, and subjective well-being among Arabic samples from Egypt and Kuwait. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 15(8), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2011.624502

- American Psychological Association. (2022). Trauma. https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma#:~:text=Trauma%20is%20an%20emotional%20response,symptoms%20like%20headaches%20or%20nausea

- Anyan, F., & Hjemdal, O. (2016). Adolescent stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression: Resilience explains and differentiates the relationships. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 213–220. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.031

- Attanayake, V., McKay, R., Jeffres, M., Singh, S., Burkle, F., Jr., & Mills, E. (2009). Prevalence of mental disorders among children exposed to war: A systematic review of 7,920 children. Medicine, Conflict, and Survival, 25(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623690802568913

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Baumeister, R. F., Tice, D. M., & Hutton, D. G. (1989). Self -presentation motivations and personality differences in self -esteem. Journal of Personality, 57(3), 547–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb02384.x

- Bean, T., Derluyn, I., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., Broekaert, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2006). Validation of multiple language versions of the reactions of adolescents to traumatic stress questionnaire. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(2), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20093

- Bean, T., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E. H. M., Derluyn, I., & Spinhoven, P. (2004). SLE manual oegstgeest. http:/www.centrum45.nl

- Bean, T., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E. H. M., Derluyn, I., & Spinhoven, P. (2004a). RATS Manual Oegstgeest. http:/www.centrum45.nl

- Bean, T., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2007). Course and predictors of mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in the Netherlands: One year follow-up. Social Science & Medicine, 64(6), 1204–1215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.010

- Braun-Lewensohn, O., Celestin-Westreich, S., Celestin, L. P., Verte, D., & Ponjaert-Kristoffersen, I. (2009). Adolescents’ mental health outcomes according to different types of exposure to ongoing terror attacks. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(6), 850–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9305-8

- Connor-Smith, J. K., Compas, B. E., Wadsworth, M. E., Thomsen, A. H., & Ve Saltzman, H. (2000). Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 976–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.976

- Çuhadaroğlu, F. (1986). Adölesanlarda Benlik Saygısı ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Hacettepe University.

- De Moor, E. L., Hutteman, R., Korrelboom, K., & Laceulle, O. M. (2019). Linking stressful experiences and psychological problems: The role of self-esteem. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(7), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550618795167

- Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(3), 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021637011732

- General Directorate of Migration Management. (2020). Current data. T.C. İçişleri Bakanlığı, Göç İdaresi Genel Müdürlüğü.

- Gomez, R., & McLaren, S. (2007). The inter-relations of mother and father attachment, self-esteem and aggression during late adolescence. Aggressive Behavior, 33(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20181

- Görmez, V., Kılıç, H. N., Örengül, A. C., Demir, M. N., Mert, E. B., Makhlouta, B., Kınık, K., & Semerci, B. (2017). Evaluation of a school-based, teacher-delivered psychological intervention group program for trauma-affected Syrian refugee children in Istanbul, Turkey. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychopharmacology, 27(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2017.1304748

- Haine, R. A., Ayers, T. S., Sandler, I. N., Wolchik, S. A., & Weyer, J. L. (2003). Locus of control and self-esteem as stress-moderators or stress-mediators in parentally bereaved children. Death Studies, 27(7), 619–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180302894

- Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938

- Harkness, K. L., Bruce, A. E., & Lumley, M. N. (2006). The role of childhood abuse and neglect in the sensitization to stressful life events in adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(4), 730–741. http;//doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.730

- Hassanzadeh, A., Heidari, Z., Feizi, A., Hassanzadeh Keshteli, A., Roohafza, H., Afshar, H., & Adibi, P. (2017). Association of stressful life events with psychological problems: A large-scale community-based study using grouped outcomes latent factor regression with latent predictors. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2017. http://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3457103

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Guilford publications. A regression-based approach

- Julian, M., Le, H. N., Coussons-Read, M., Hobel, C. J., & Schetter, C. D. (2021). The moderating role of resilience resources in the association between stressful life events and symptoms of postpartum depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.082

- Kazarian, S. S. (2009). Arabic contingencies of self worth: Arabic translation and validation of the contingencies of self-worth scale in Lebanese youth. Arab Journal of Psychiatry, 20(2), 123–134.

- Kim, K. J., Conger, R. D., Elder, G. H., Jr, & Lorenz, F. O. (2003). Reciprocal influences between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development, 74(1), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00525

- Kliewer, W., & Sandler, I. N. (1992). Locus of control and self-esteem as moderators of stressor-symptom relations in children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 20(4), 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00918984

- Lee, D., Yu, E. S., & Kim, N. H. (2020). Resilience as a mediator in the relationship between posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth among adult accident or crime victims: The moderated mediating effect of childhood trauma. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1704563. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1704563

- Li, J., Chen, Y. P., Zhang, J., Lv, M. M., Välimäki, M., Li, Y. F., Zhang, J., Tao, Y.-X., Ye, B.-Y., Tan, C.-X., & Zhang, J.-P. (2020). The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem between life events and coping styles among rural left-behind adolescents in China: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.560556

- Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M., & LeBlanc, J. C. (2013). The CYRM-12: A brief measure of resilience. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405676

- Luk, J. W., Patock-Peckham, J. A., Medina, M., Terrell, N., Belton, D., & King, K. M. (2016). Bullying perpetration and victimization as externalizing and internalizing pathways: A retrospective study linking parenting styles and self-esteem to depression, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.1090453

- McGrath, L. B., & Kovacs, A. H. (2019). Psychological resilience: Significance for pediatric and adult congenital cardiology. Progress in Pediatric Cardiology, 54, 101129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppedcard.2019.101129

- Nielsen, S. S., Norredam, M., Christiansen, K. L., Obel, C., Hilden, J., & Krasnik, A. (2008). Mental health among children seeking asylum in Denmark–the effect of length of stay and number of relocations: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 293. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-293

- Nima, A. A., Rosenberg, P., Archer, T., & Garcia, D. (2013). Anxiety, affect, self-esteem, and stress: Mediation and moderation effects on depression. PloS one, 8(9), e73265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265

- Nrugham, L., Holen, A., & Sund, A. M. (2010). Associations between attempted suicide, violent life events, depressive symptoms, and resilience in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(2), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43a2

- Plancherel, B., Nuñez, R., Bolognini, M., Leidi, C., & Bettschart, W. (1992). L’évaluation des événements existentiels comme prédicteurs de la santé psychique à la préadolescence. European Review of Applied Psychology, 42(3), 229–239.

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

- Sirin, S. R., & Rogers-Sirin, L. R. (2015). The educational and mental health needs of Syrian. Migration Policy Institute. refugee children.

- Thurston, I. B., Hardin, R., Kamody, R. C., Herbozo, S., & Kaufman, C. (2018). The moderating role of resilience on the relationship between perceived stress and binge eating symptoms among young adult women. Eating Behaviors, 29, 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.03.009

- Tiet, Q. Q., Bird, H. R., Hoven, C. W., Moore, R., Wu, P., Wicks, J., Cohen, P., Goodman, S., & Cohen, P. (2001). Relationship between specific adverse life events and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005288130494

- UNHCR (2018). Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2018. Field Information and Coordination Support: Section Division of Programme Support and Management. Case Postale 2500 1211. [email protected]

- Werner, E. E. (2012). Children and war: Risk, resilience, and recovery. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 553–558. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000156

- Yayan, E. H., Düken, M. E., Özdemir, A. A., & Çelebioğlu, A. (2020). Mental health problems of Syrian refugee children: post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 51, 27–32.

- Zaidi, U., Awad, S., Mortada, E. N. V. Q., D, H., & Kayal, G. F. (2015). Psychometric evaluation of Arabic version of self-esteem, psychological well-being and Impact of Weight on Quality of Life Questionnaire (IWQOL-LITE) in female student sample of PNU. European Medical, Health and Pharmaceutical Journal, 8(2), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.12955/emhpj.v8i2.703

- Zhou, X., Wu, X., & Zhen, R. (2018). Self-esteem and hope mediate the relations between social support and post-traumatic stress disorder and growth in adolescents following the Ya’an earthquake. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 31(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1374376