ABSTRACT

The first study aims to examine cyberbullying roles and their relation to personal and normative beliefs. For this purpose, a total of 404 7th to 9th grade students answered the Inventory of Observed Cyberbullying Incidents. For the second study, semi-structured interviews to 34 9th grade students were analysed based on the Social Cognitive Theory of Moral Agency, to understand which moral disengagement mechanisms were more frequent regarding cyberbullying scenarios. Results revealed that bystanders were the most common role. Regarding beliefs, the All type of involvement group considered cyberbullying to be less severe than Bystanders, Bystanders-Victims and No Involvement group. Moreover, they perceived that their peer group believed cyberbullying was less unfair than Bystanders and No Involvement group. The most used moral disengagement mechanisms were blaming the victim and euphemistic labelling regarding seriousness. Personal, normative beliefs, as well as moral disengagement mechanisms operating in cyberbullying should be considered when designing interventions.

Introduction

Interpersonal interactions in virtual contexts can be negative when aggression is involved. Online aggression can take the form of cyberbullying, as repeated acts of aggression that are perpetrated by an individual or group with the intent to cause harm to others through the use of technology (Tokunaga, Citation2010). Other authors consider cyberbullying to be an act of aggressiveness that is intentional and repeated over time, which is carried out by a group or an individual, using electronic forms of contact, against someone who cannot easily defend themselves (Smith et al., Citation2008). Cyberbullying can take the form of heated arguments, offensive messages, spreading rumours and personal information, posting material as if it was the victim, excluding someone from online groups (Willard, Citation2007). More recent studies distinguishes several types of cyberbullying by specifying the different behaviour: threatening someone, harassing with sexual content, spreading rumours about one’s life, making fun of someone, insulting someone, demonstrating to have information about someone’s life that may affect their psychological well-being, revealing data about someone’s private life, pretending to be someone, using someone’s image without authorization (Francisco et al., Citation2015); ridiculing or demeaning another person, embarrassing someone by posting intimate photos or videos, and excluding someone from social networking sites or gaming sites (Myers & Cowie, Citation2019). Moreover, other authors included better known terms in the category of cyberbullying, such as cyberharassment and cyberstalking (Kremling & Parker, Citation2018).

These types of behaviour might occur on any social media apps and social networking sites (e.g. Whatsapp, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, blogs, etc.), Youtube and through alternative digital communication media such as email, telephone, and text messaging service (Chan et al., Citation2021; Francisco et al., Citation2015; Whittaker & Kowalski, Citation2015). Moreover, they occur within peer group interactions, specifically in young individuals’ social groups and relationships (Dennehy et al., Citation2020), hence its social nature (Allison & Bussey, Citation2017), and it is known that social influence (e.g. normative beliefs, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, bystander behaviour) (e.g. Allison & Bussey, Citation2017; Dang & Liu, Citation2020; Veiga Simão et al., Citation2018) plays an important role in intentions to engage in cyberbullying (Lazuras et al., Citation2013). Additionally, motivation to cyberbully (for different reasons, for example, ‘to impress others,’ or ‘to defend themselves’) has been positively related to involvement in cyberbullying, both as an aggressor and victim (Shapka et al., Citation2018). This may be related to personal moral beliefs, as they also play a crucial role in cyberbullying (Allison & Bussey, Citation2017), in the sense that cyberbullying can be considered fair depending on the motives, as well as on the level of moral disengagement, since those involved are justifying their reprehensible conduct. However, the anonymity that sometimes characterizes cyberbullying may free those involved from normative and social constraints on their own behaviour (Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2006), and also because of the potential to shift blame for another person (Betts & Spenser, Citation2017). Therefore, we intend to better understand how personal and normative beliefs vary according to different types of involvement in cyberbullying situations (study 1).

Cyberbullying is considered immoral behaviour (Arsenio & Lemerise, Citation2004; Romera et al., Citation2021) as it has a negative impact on victims’ welfare and rights (Bussey et al., Citation2015). Therefore, it is necessary to understand what motivates cyberbullying behaviour in order to develop effective interventions to reduce its incidence (Abbasi et al., Citation2018; Ang et al., Citation2011). That is, in addition to personal beliefs, cyberbullying can be motivated by other idiosyncratic characteristics, such as moral disengagement (e.g. Bussey et al., Citation2015). In fact, moral disengagement allows individuals to lessen their responsibility (Bandura, Citation2002) in cyberbullying and decrease their guilt for engaging in this type of behaviour, despite their motivations. Therefore, we intend to explore the role of moral disengagement in cyberbullying situations (Study 2), since it is a major psychological foundation of this type of behaviour (Bussey et al., Citation2015; Zhao & Yu, Citation2021).

Literature review

Personal and normative beliefs about cyberbullying situations

This investigation is grounded in the Social Cognitive Theory of Moral Agency that considers a reciprocal causality between internal personal factors (such as cognitive, affective and biological events), behaviour patterns and environmental events. All of these interact and influence each other (Bandura, Citation1991). In view of this, we can postulate that cyberbullying behaviour (i.e. aggressors’ and bystanders’ behaviour) are influenced by both individual and environmental factors.

The moral acceptability of different types of bullying (including cyberbullying), is a possible predictor of perpetration in adolescence (Dang & Liu, Citation2020; Williams & Guerra, Citation2007). Moreover, considering that cyberbullying episodes are influenced by prior interactions, attitudes and peer group norms regarding these situations (Allison & Bussey, Citation2017), it is paramount to understand how personal beliefs and normative beliefs are related to different patterns of behaviour within these episodes. Complementarily, individual characteristics have been known to influence cyberbullying perpetration (Veiga Simão et al., Citation2018). For example, a lack of moral values seems to lead to cyberbullying behaviour (Perren & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, Citation2012), and particularly, self-enhancement values (i.e. attention to the self, power, social status and dominance) predicted cyberbullying (Menesini et al., Citation2013). Also, collective norms serve as codes of conduct that guide individuals’ behaviour within a group, however, at the individual and psychological level, there is an interpretation made by each individual of these collective norms that constitute their perceived norms (Lapinski & Rimal, Citation2005).

It is also known that beliefs related to bullying and negative bystander behaviour have been associated with perpetration regarding different types of bullying (i.e. verbal, physical, and cyberbullying), although this association seems to be smaller with regards to cyberbullying. For example, Bastiaensens et al. (Citation2016) found that bystanders who perceived that their peers had been involved in cyberbullying situations, and that they approved cyberbullying (normative moral beliefs), tended to join the aggressor through social pressure. In fact, adolescents’ normative moral beliefs seem to mediate the relationship between their personal moral beliefs about cyberbullying and using the content from the verbal aggressions they witnessed in cyberbullying incidents (Veiga Simão et al., Citation2018). This may occur when adolescents are confronted with an ambiguous social situation in which their normative beliefs about aggression may be activated (Ang et al., Citation2011).

In view of this, this study focuses on personal beliefs, since individual factors are fundamental to interpret and understand events and how to act accordingly. This study also highlights participants’ beliefs regarding the fairness (personal moral beliefs) and the severity (personal beliefs of perceived severity) of cyberbullying situations. Additionally, in terms of environmental factors, we will investigate participants’ perceived normative beliefs because evidence has shown the relevance of peer group normative beliefs in predicting attitudes towards bullying (Almeida et al., Citation2009). Two distinct types of normative beliefs will be analysed, considering that they can have different effects on different behaviour (Macháčková & Pfetsch, Citation2016). Particularly, at the group level, we are going to examine individuals’ perceived friends’ approval of cyberbullying behaviour (normative moral beliefs), and their perceptions of their friends’ beliefs about the severity of cyberbullying situations (normative beliefs of perceived severity).

Moral disengagement and Cyberbullying

Several factors influence moral conduct, such as moral standards, which are built during socialization and serve to regulate individuals’ action (Bandura et al., Citation1996). Moreover, moral conduct is motivated and regulated by the influence of self-reactive mechanisms (i.e. moral disengagement mechanisms) exercised during action (Bandura, Citation1991). Moral disengagement is established within the social cognitive theory, and represents a self-regulatory process that enables individuals to disengage from their aggressive conduct by altering their beliefs regarding their immoral conduct (Bandura, Citation1999; Bandura et al., Citation1996). Thus, moral conduct is the product of the selective activation of moral disengagement mechanisms (Bandura, Citation2002).

Moral disengagement mechanisms are organized in four loci. Firstly, locus of behaviour, where immoral conduct is transformed into fair or justifiable conduct through Moral Justification, which allows harmful conduct to be reconstructed as serving social or moral intentions; Euphemistic Labelling, which decreases the severity of a behaviour by naming it as less severe behaviour, and through Advantageous Comparison, by contrasting with other behaviour, and therefore, harmful acts are considered morally correct. Secondly, there is locus of agency, where the perpetrator’s agentic role is minimized in detrimental conduct through the Displacement of Responsibility, in which individuals view their actions as resulting from others’ orders, and the Diffusion of Responsibility, which enables individuals to divide the responsibility for an action among a group. The third loci is based on the outcome of the behaviour, where moral control is faded, depending on the outcome of one’s actions, through the Distortion of consequences, which inhibits the activation of self-censure, because one’s’ conduct is overlooked, minimized, distorted or disregarded. Lastly, the locus of the recipient, which implies self-exonerating one’s own actions by Dehumanizing the victims, that is, depriving them of their human qualities and by Attributing them the Blame and allowing the aggressor to justify their actions, and considering the victims responsible for their suffering (Bandura, Citation2002; Bandura et al., Citation1996).

Thus, considering this theoretical framework, moral disengagement has an uninhibited effect, leading bullies to behave more easily in a negative way towards others (Hymel et al., Citation2005), and although it is not possible to observe cyberbullying effects immediately, the use of moral disengagement mechanisms are still necessary to prevent self-censure related to this behaviour (Wang et al., Citation2016). Moreover, as moral disengagement increases over the years in high school (Smith & Slonje, Citation2010) and severe cyberbullying incidents peak during middle adolescence (Festl et al., Citation2017), it is important to investigate the dynamics of these psychological processes during adolescence.

Despite these findings, little is known about the role of these mechanisms since they can operate as motivators for cyberbullying behaviour. For example, self-serving cognitive distortions, such as blaming others and minimizing/mislabelling can occur before or after the transgressions (Barriga et al., 2001, as cited in Bacchini et al., Citation2016), whereas self-centred distortions (i.e. expectations, for example) are prior to anti-social behaviour. Thus, we believe that moral disengagement mechanisms play a similar role in explaining cyberbullying (Parlangeli et al., Citation2020). To uncover this issue, qualitative research is needed because investigations have only focused on motivations for cyberbullying, role of participants and notions of cyberbullying (e.g. Bakar, Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2019). Therefore, we believe that there is a gap in the literature concerning the role of each moral disengagement mechanism. Additionally, we assume that to understand the complexity of cyberbullying phenomenon, these mechanisms need to be qualitatively studied, in order to comprehend which function these mechanisms may play in cyberbullying. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the antecedents (A), the behaviour itself (B) and its consequents (C), or what we propose as the ABC structure for understanding the phenomena.

Based on the literature review, we are convinced that personal and normative beliefs and moral disengagement mechanisms should be considered altogether to understand the dynamics of cyberbullying, since all are associated with cyberbullying behaviours (Bastiaensens et al., Citation2016; Kowalski et al., Citation2014; Parlangeli et al., Citation2020). For example, in a meta-analysis cyberbullying perpetration was found to be associated with normative beliefs about aggression and moral disengagement (Kowalski et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, higher moral disengagement combined with more positive normative beliefs regarding the bully role have been associated with more positive attitudes regarding the same role (Almeida et al., Citation2009). Additionally, gender and age are important when examining cyberbullying. Since girls were more prone to being cyberbullying victims during early to mid‐adolescence, whereas boys showed higher levels of victimization during later adolescence. Moreover, boys were more prone to being aggressors than girls; however, age moderated this effect (Barlett & Coyne, Citation2014). Moreover, with respect to age, research has found that cyberbullying rates tended to gradually increase, with the growth of age (e.g. Zhao & Yu, Citation2021).

Considering morality issues, some authors (Perren & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, Citation2012) did not find significant interaction effects when age and gender were consider as moderators in the relationship between moral variables (i.e. moral disengagement, moral emotions and moral values) and both bullying and cyberbullying. However, in recent studies, gender differences were found for normative beliefs about cyberbullying, with boys scoring higher than girls, however grade level was found to have the strongest influence on beliefs, since they tended to increase with age (Peled et al., Citation2019). Nonetheless, the same authors found that cyberbullying was more likely, when normative beliefs were higher.

In view of this, the purpose of study 1 is to answer the following research questions:

Which are the most frequent types of involvement in cyberbullying?

Is there a relation between adolescents’ Personal Beliefs of Perceived Severity and Personal Moral Beliefs, and their type of involvement in cyberbullying, school grade and gender?

Is there a relation between adolescents’ Normative Beliefs of Perceived Severity and Normative Moral Beliefs, and their type of involvement in cyberbullying, school grade and gender?

Moreover, based on the Social Cognitive Theory of Moral Agency, we intended to gain a deeper understanding of the role of moral disengagement mechanisms in the justifications underlying cyberbullying perpetration and bystander behaviour, therefore, study 2 proposes to answer the following questions:

(4) Do students use Moral Disengagement mechanisms to describe cyberbullying situations, and justify the aggressors’ and bystanders’ behaviour? If so, which mechanisms are used?

(5) Is there a relation between the moral disengagement mechanisms used to justify aggressors’ behaviour, and personal and normative beliefs?

Method

Participants

The sample for study 1 consisted of a convenience sample of 404 students from 7th to 9th grade (Mage = 13.57, SD = 1.11, 53% female). Students were distributed by grade as follows: 7th grade (25.5%), 8th grade (33.2%) and 9th grade (41.3%). Data was collected in Portugal, from two schools from the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon, one school from the central-southern region and one school from Algarve, which is further south. Most students were Portuguese (95.5%), other students were mainly from other European countries (e.g. Romania, Spain, Poland, Sweden, Ukraine, Moldavia), from African countries (e.g. Angola), and from South America (e.g. Brazil, Chile). All students master the Portuguese language. All schools were public educational establishments.

We opted to collect a sample from these grade levels because the prevalence rates of cyberbullying peak at the ages of 12 to 15 (Tokunaga, Citation2010). Participants completed the Inventory of Observed Cyberbullying Incidents (IOCI), and the 9th grade students were asked to voluntarily participate in an in-depth semi-structured interview with scenarios. We asked 9th graders because they report engaging, witnessing and intervening more in cyberbullying (Bussey et al., Citation2015), as well as having more flexible moral standards and higher levels of moral disengagement associated with cyberbullying, than younger students (Gini et al., Citation2014). Thus, thirty four 9th grade students who volunteered composed the sample of the study 2 (Mage = 14.29, SD = 0.72, 53% female).

Instruments

Quantitative approach instruments for beliefs, involvement and demographic data

We used the Inventory of Observed Incidents of Cyberbullying (IOIC; Veiga Simão et al., Citation2018), which includes three questionnaires that were adapted based on the Cyberbullying Inventory for College Students (Francisco et al., Citation2015), that are the Aggressor scale, the Victim scale and the Bystander scale. These scales allow us to understand the type and degree of involvement of participants (on a 5-point Likert scale of 1 = never to 5 = several times per day). The Bystander scale is also designated by Noticing the Event Scale, in the IOIC, since this inventory is grounded in the Bystander Intervention Model (Ferreira et al., Citation2020). Moreover, from the IOIC other 4 questionnaires regarding personal and normative beliefs were used in study 1.

The IOIC begins with an introduction regarding the use of technology by youth, its advantages and how its misuse may lead to several types of cyberbullying behaviour. Moreover, the introduction of each scale positions students in the online context as an observer (e.g. … have you observed the behaviour mentioned above in written messages and/or photos/videos, email, Chat, Messenger, Skype, Facebook, Youtube, Blogs, WhatsApp, online games, etc.).

All questionnaires used are described below and the following fit statistics are presented: comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), incremental fit index (IFI), root mean square error approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR).

Aggressor Scale (α = .79) is a 9-item measure that asks participants to remember if they have cyberbullied someone, referring to specific behaviours (e.g. ‘I spread rumors about someone’s life.’). CFA presented good fit (Hooper et al., Citation2008), namely [χ2 (25) = 27.17, p = .35, χ2/df = .00, CFI = .99, GFI = .99, IFI = 0.93, RMSEA = .03, LO = .00, HI = .09 and SRMR = .05].

Victim Scale (α = .83) is a 9-item measure that asks participants to remember if they have been cyberbullied, referring to specific behaviour (e.g. ‘They threatened me’). CFA presented good fit (Hooper et al., Citation2008), namely [χ2 (25) = 44.52, p < 0.05, χ2/df = 1.78, CFI = .94, GFI = .98, IFI = .90, RMSEA = .09, LO = .04, HI = .13 and SRMR = .06].

Bystander Scale or Noticing the Event Scale (α = .90) is a 9-item measure that asks participants to remember if they observed some kind of cyberbullying behaviour (e.g. ‘I saw someone threatening someone else.’). CFA presented good fit values (Hooper et al., Citation2008), namely, [χ2 (25) = 54.88, p < 0.01, χ2/df = 2.20, CFI = .97, GFI = .97, IFI = .96, RMSEA = .08, LO = .04, HI = .10, and SRMR = .04].

Personal moral beliefs about cyberbullying behaviour (α = .90) is a 9-item measure that asks participants (on a 6-point Likert scale of 1 = fair to 6 = unfair) whether they think specific cyberbullying behaviour is fair or unfair (e.g. ‘I think that someone being threatened online is fair/unfair’). CFA values presented a good fit, namely, χ2(22) = 26.55, p = .23, χ2/df = 1.21, CFI = .98, GFI = .93, IFI = .98, RMSEA = .02, LO = .00, HI = .04, and SRMR = .04 (Veiga Simão et al., Citation2018).

Normative moral beliefs about cyberbullying behaviour (α = .94) is a 9-item measure that asks participants (on a 6-point Likert scale of 1 = fair to 6 = unfair) what they think their peers would think if they engaged in specific cyberbullying behaviour (e.g. ‘My friends think that if I threatened someone online that it’s fair/ unfair.’). CFA presented good fit (Hooper et al., Citation2008), namely, χ2(18) = 34.91, p < .05, χ2/df = 1.94, CFI = .92, GFI = .92, IFI = .92, RMSEA = .04, LO = .02, HI = .06, and SRMR = .05 (Veiga Simão et al., Citation2018). More information regarding the type of response of these two scales can be found in Appendix A.

Personal beliefs of perceived severity about cyberbullying behaviour (α = .84) is a 9-item measure that asks participants (on a 6-point Likert scale of 1 = joke to 6 = serious) whether they think specific cyberbullying behaviour is a joke or serious (e.g. I think that someone being threatened online is a joke/serious.”). CFA presented good fit values (Hooper et al., Citation2008), namely, χ2(22) = 40.63, p < .05, χ2/df = 1.85, CFI = .91, GFI = .92, RMSEA = .04, LO = .02, HI = .06, and SRMR = .11.

Normative beliefs of perceived severity about cyberbullying behaviour (α = .92) is a 9-item measure that asks participants (on a 6-point Likert scale of 1 = joke to 6 = serious) what they think their peers would think if they engaged in specific cyberbullying behaviour (e.g. ‘My friends think that if I threatened someone online that it’s a joke/serious.’). CFA presented good fit values (Hooper et al., Citation2008), namely, χ2(22) = 65.23, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.96, CFI = .90, GFI = .93, IFI = .91, RMSEA = .05, LO = .04, HI = .07, and SRMR = .05.

Qualitative approach to investigate moral disengagement mechanisms – Semi-structured interview with scenarios

Semi structured interviews with scenarios (see Appendix B) were conducted to collect information about the role of moral disengagement in cyberbullying situations, regarding the aggressor’s and bystanders’ behaviour. Hence, the scenarios used in the interviews depicted three hypothetical cyberbullying situations. Considering that contextual factors may influence the activation of moral disengagement in different cyberbullying scenarios (Luo & Bussey, Citation2019), different social media was considered in the scenarios, as well as boys and girls for each participant role (i.e. victim, aggressor and bystanders). Participants were asked to talk about what they thought about the aggressor: (i.e. ‘What do you think is happening in this scenario?’, ‘What do you think about this post?’, ‘What do you think led XXX to post this message?’) and about bystander behaviour (i.e. ‘What do you think about these comments?’). Furthermore, with the objective of placing students in a bystander perspective of those situations, participants were asked: ‘If you saw a situation like this, would you try to understand if it was a joke or something serious? Why?’ and ’Would you react to these posts? How?’. Each interview was audio-recorded, and the average length was 48 minutes. Interviews were conducted in a room away from the classrooms, allowing students’ privacy and confidentiality.

Procedure

We asked for authorization to conduct this study from several entities: The Ministry of Education of Portugal, the Portuguese National Commission of Data Protection, the Deontology Committee of the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Lisbon, the schools’ boards of directors and the teachers. For parents, we asked for written permission and we also asked for informed consent from the adolescents themselves. All granted their authorization. The questionnaires were administered online in the classroom context. Both questionnaires and interviews were conducted by two research members, who are Educational Psychologists. All students were informed that psychological assistance was available if they felt the need to talk about this subject, and that they could quit their participation any time they wanted to. Also, participation in the interview depended on students’ volunteerism.

Data analysis

Study 1 – Statistical Analysis

We examined possible differences of the variables in study considering the participants’ role regarding their cyberbullying involvement. The gender variable was coded as 0 = girls and 1 = boys. In order to answer the first research question, descriptive statistics were conducted. Moreover, with respect the second and third research questions, hierarchical regressions were conducted using SPSS, followed by Post Hoc Tukey test using the Agricolae package for R (Mendinburu, Citation2021). All assumptions (see Appendix C) were met (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007).

Study 2 – Content analysis

Semi-structured interviews were transcribed verbatim. We performed content analysis (with QSR International’s NVivo 11 software) with a mixed approach (deductive/inductive). The categorization process went beyond Social Cognitive Theory of Moral Agency (Bandura, Citation2002), and other categories emerged. The coding units we established were adolescent’s written verbalizations with meaning (Amado et al., Citation2014), summing a total of 396 verbalizations analysed. We performed an initial phase, where categories were created, and a re-checking phase where a set of verbalizations were analysed by two other researchers and adjustments were made to the operational definition of the categories. Finally, two independent coders rated the data. Inter-rater reliability was excellent, as mentioned in the literature (McGraw & Wong, Citation1996), with an ICC = .99, with 95% confident interval = 0.99–0.99.

Results

Study 1 – The types of involvement in cyberbullying and adolescents’ personal and normative beliefs

We took a conventional variable-based classification approach, such as mean-based cut-off values (from the Aggressor, Victim and Bystander scales) to determine which types of involvement were present in our sample, and to later assign cyberbullying roles (). Means of these scales were used and dummy variables were created according to the means (0 = mean below 1, and 1 = mean above 1). For example, a participant who scored a mean above 1 in the Bystander Scale, and below 1 in the Aggressor and Victim scales will be labelled as bystander and dummy coded as 1 for the new dummy variable for bystander scale. This means that for coding 0 in the dummy variables, participants need to answer ‘Never’ to all items of each scale. For both personal and normative beliefs, higher scores in these scales indicate greater beliefs about the seriousness and unfairness of cyberbullying behaviours.

Table 1. Distribution of the different types of involvement.

Answering to the first research question, as shown in , most participants were bystanders only (33.9%), followed by a group with all types of involvement (23.8%) and a group with no involvement (21%). Thus, an overlap of roles was present, with very few victim/aggressors. Therefore, from now on; we will refer to cyberbullying profiles because this concept encompasses the complexity of the cyberbullying phenomenon more.

We opted to exclude three roles because they were composed of very few participants and statistical analysis could not be performed to compare these groups (i.e. Aggressors only, Victims only and Aggressor-Victims). Therefore, the sample of study 1 decreased from 404 to 396 students.

We performed descriptive statistics and correlations (), all of which presented results that revealed a positive significant correlation between the group with all types of involvement and all four types of beliefs, whereas the group with no involvement was significantly and negatively correlated to all four types of beliefs. Moreover, results also showed a positive significant correlation between all beliefs.

Table 2. Means, standard deviation, and correlations (overall sample).

To answer the second and third research questions, hierarchical linear regression was conducted, with gender and grade as covariates (Model 1) and the type of involvement as the independent variable to predict beliefs and norms (i.e. four dependent variables). All results can be found in .

Table 3. Hierarchical linear regression model for personal beliefs of perceived severity and personal moral beliefs.

Considering personal beliefs of perceived severity (), Model 1 explains 2.8% of variance in this dependent variable (F(2.4) = 6.724, p = .001), however only gender was a significant predictor (B = −.319, SE = .087, p = .00). By introducing the variable type of involvement in Model 2, there was a significant change in the model adjustment contributing to an increase of 14.4% in explaining the dependent variable (F(2,4) = 14.262, p = .000). Gender was still a significant predictor (B = −.300, SE = .083, p = .00), which means that girls (coded 1) tended to consider cyberbullying more severe than boys (coded 2). Post hoc comparisons indicated that the group with all types of involvement was significantly different from the group with no involvement (p = 0.00), bystanders (p = 0.00) and bystander-victims (p = 0.00). Participants from the group with all types of involvement had on average .81 less points regarding personal beliefs of perceived severity than those who had no involvement, that is, .61 less points than bystanders and .79 less than bystander-victims. These results revealed that bystanders, bystanders-victims and the group with no involvement considered cyberbullying to be more severe/serious than the group with all types of involvement.

As for personal moral beliefs (), in Model 1 neither gender (B = −.111, SE = .067, p = .100) nor school grade (B = −.005, SE = .042, p = .896) contributed to explain the dependent variable (F(2,4) = 1.358, p = .258). However, Model 2 had a significant change in model adjustment contributing to 5.9% in explaining the dependent variable (F(2,4) = 7.016, p = .000). Post hoc comparisons showed that the group with all types of involvement was significantly different from the group with no involvement (p = 0.00), and bystanders (p = 0.00). Participants who had all types of involvement had on average .81 less points regarding personal beliefs of perceived severity than those from the group with no involvement and .37 less than bystanders. These results suggest that bystanders and the group with no involvement tended to perceive cyberbullying behaviour as more unfair than participants from the group with all types of involvement.

With respect to normative beliefs of perceived severity (), Model 1 explained 1.2% of the variance in the dependent variable (F(2.4) = 3.314, p = .037), however only school grade was a significant predictor (B = −.186, SE = .080, p = .020). With respect to the school grade, this means that participants from the lower academic levels tended to consider that their peers believed cyberbullying was more severe than students from higher academic levels. However, school grade ceases to be significant when the type of involvement in cyberbullying is added to the model. In Model 2 there was a significant change in the model adjustment contributing to an increase of 9.3% in explaining the dependent variable (F(2,4) = 9.788, p = .000). Post hoc comparisons indicated that the group with all types of involvement was significantly different from the group with no involvement (p = 0.00), bystanders (p = 0.00) and bystander-victims (p = 0.00). Participants with all types of involvement had on average 1.10 less points on normative beliefs of perceived severity than those from the group with no involvement, .80 less points than bystanders and .96 less than bystander-victims. These results follow the same pattern as those for the personal beliefs of perceived severity, suggesting that bystanders, bystanders-victims and those who were not involved, perceived that their peer group believed cyberbullying was more severe/serious than those engaged in all types of involvement.

Table 4. Hierarchical linear regression model for normative beliefs of perceived severity and normative moral beliefs.

Considering normative moral beliefs (), Model 1 did not contribute to explain the dependent variable (F(2,4) = 2.756, p = .065), however school grade was a significant predictor (B = −.144, SE = .067, p = .032). This means that participants from the lower academic levels tended to consider that their peers believed cyberbullying is more unfair than students from higher academic levels. However, this difference does not exist when we account for students’ involvement in cyberbullying. Model 2 had a significant change in model adjustment contributing to 6.1% in explaining the dependent variable (F(2,4) = 6.407, p = .000). Post hoc comparisons showed that the group engaged in all types of involvement was significantly different from the those who were not involved (p = 0.00), and bystanders (p = 0.00). Participants in all types of involvement had on average .73 less points regarding normative moral beliefs than those from who were not involved and .60 less than bystanders. These results revealed a similar pattern of personal moral beliefs, and suggest that the group engaging in all types of involvement perceived that their peer group believed cyberbullying was fairer than those who were only bystanders and those who had no involvement.

Study 2 – Adolescents’ moral disengagement in cyberbullying situations

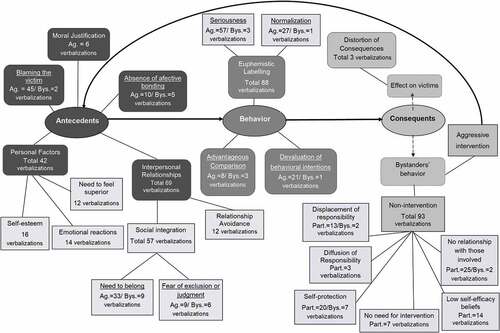

To explore the role of moral disengagement in cyberbullying, we specifically examined whether adolescents engaged in moral disengagement when talking about cyberbullying situations. Firstly, from the interview data, we organized categories considering the timeline of events. We proposed that an event, need or characteristic motivated (i.e. antecedents – A) the aggressor’s cyberbullying behaviour; the cyberbullying behaviour occurred (i.e. behaviour – B); and finally, this behaviour generated consequences, for both victims and bystanders (i.e. consequents – C). This organization (ABC) enabled us to understand the data from the participants’ bystander perspective, how they interpreted antecedents, described cyberbullying situations, and perceived cyberbullying consequents (). Afterwards, through deductive reasoning, several moral disengagement mechanisms emerged regarding antecedents, behaviour and consequents, along with other attributions that emerged (see Appendix D and E).

Figure 1. Procedural model of cyberbullying in the perspective of participants, as bystanders of the scenarios.

shows that at the antecedents’ level (34% verbalizations), participants referred to some moral disengagement mechanisms (blaming the victim and moral justification), and other attributions for aggressors’ cyberbullying behaviour (Appendix D and E). At the behaviour level (32% and 2% verbalizations regarding aggressors’ and bystanders’ behaviour, respectively), participants mentioned two moral disengagement mechanisms to describe cyberbullying situations, namely, advantage comparison and euphemistic labelling. The latter, was portioned in two, seriousness and normalization, because when describing the cyberbullying scenarios, participants used expressions like ‘joke’ or ‘normal’, that guided the classifications. Moreover, the devaluation of behavioural intentions emerged, when participants assessed the cyberbullying incident as being something that was not going to occur, and we considered this to be a new moral disengagement mechanism because of its purpose, to decrease self-sanctions.

Table 5. Frequencies of categories and subcategories regarding aggressors’ cyberbullying behaviour.

Finally, at the consequent level (1% verbalizations), in the victims’ section (effects on the victim), participants mentioned the distortion of consequences mechanism. Furthermore, the bystanders’ section (bystanders’ behaviour) was divided into two categories: aggressive intervention (5% verbalizations) and non-intervention (26% verbalizations). Bystanders may continue the aggression (Ferreira et al., Citation2020) and in this case, blaming the victim was the only moral disengagement mechanism used. Regarding those who had no intervention, the displacement of responsibility and the diffusion of responsibility were both used regarding the bystanders of the scenarios and the former, was also used to exonerate participants as bystanders. shows all the above categories and subcategories and examples.

To answer the last research question, correlations were performed between the moral disengagement mechanisms which were spontaneously mentioned and the 4 different beliefs (). Results showed that euphemistic labelling regarding seriousness had a negative significant correlation with personal moral beliefs of perceived severity and normative beliefs of perceived severity. Also, euphemistic labelling regarding normalization had a negative significant correlation with normative beliefs of perceived severity.

Table 6. Correlations between moral disengagement mechanism with respect to aggressors’ behaviours and personal and normative beliefs.

Discussion

Types of involvement

Our findings translate the complexity of cyberbullying, since most types of involvement are associated with overlapping of roles and not singular roles (e.g. bystander-victim and victim, respectively). For example, Festl et al. (Citation2017) did not find participant cyberbullies or cybervictims only, which is similar to our low frequency of these roles. However, we had a high frequency of boys in a bystander-aggressor group, which corroborate the findings of Barlett and Coyne (Citation2014), since they found that boys were generally more likely to engage in cyberbullying behaviour. Likewise, Tokunaga (Citation2010) concluded that girls were at high risk of suffering from victimization, which is in line with our findings with respect to the high frequency of girls in the bystander-victim group. Regarding those who engaged in all types of involvement, the high percentage may be due to the fact that cyberbullies tended to be cybervictims as well (Kowalski et al., Citation2014), thus the strongest predictor of engaging in cyberbullying as an aggressor is having been a cybervictim first (Hood & Duffy, Citation2018; Lozano-Blasco et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the higher frequency of girls in all types of involvement corroborates the findings from Schultze-Krumbholz et al. (Citation2015), since they found that girls were more likely to be in the cyberbullying aggressor-victim group.

Personal and normative beliefs about cyberbullying

As a contribution, this study allowed us to better understand how personal and normative beliefs may be associated with the different patterns of cyberbullying involvement. Our results showed that those who engaged in all types of involvement presented the lowest values regarding all four types of beliefs. These results seem to be in line with those found by Burton et al. (Citation2012), who found that cyberbullies and cyberbully-victims had higher normative beliefs about aggression than cybervictims and who were uninvolved. However, in this study higher scores indicate higher support for aggression. This may occur for several reasons. For example, with respect to personal beliefs of perceived severity, it can be related to the fact that this group included the aggressors, and this role has a great impact as they tend to minimize the effect of their actions on others (Hinduja & Patchin, Citation2015), and thus, they may believe that cyberbullying is not that serious. Moreover, cyberbullies tended to be less severe in their evaluations of cyberbullying vignettes (Talwar et al., Citation2014). Thus, if they do not consider cyberbullying that serious, they will most likely believe that their peer group feels the same way about it, and this can explain the lowest scores on normative beliefs of perceived severity. Moreover, by including the aggressors in this group, it would explain the scores in personal moral beliefs because it is known that cyberbullying is more likely to occur when scores of normative beliefs to cyberbully are higher (Peled et al., Citation2019), and the normative beliefs may predict the attitudes of participants regarding their role in cyberbullying (Almeida et al., Citation2009).

Considering that the perception about the normative beliefs of the peer group regarding bullying roles have predicted the attitudes of participants concerning their respective role (Almeida et al., Citation2009), the same could occur regarding cyberbullying. Moreover, perceiving that friends approved cyberbullying behaviour was associated with a higher level of social pressure to also engage in cyberbullying (Veiga Simão et al., Citation2018). This can explain the lowest scores of those engaged in all types of involvement in terms of normative moral beliefs and personal moral beliefs. It is plausible that the more participants were involved in cyberbullying situations, the more they tended to perceive that their peers believed that cyberbullying is less serious and less unfair. Despite the school grade being significant in Model 1 for predicting normative beliefs of perceived severity and normative moral beliefs, which was in line with previous studies that considered that normative beliefs were lower in lower school grades (Peled et al., Citation2019), this changes when we take the type of involvement into the equation, probably because the type of involvement in its own, changes the normative beliefs, in spite of school grade. With respect to personal beliefs of perceived severity, and the fact that in Model 1, gender was a significant predictor, it can be related to the fact that gender had a significant moderating effect between moral disengagement and cyberbullying (Zhao & Yu, Citation2021), and the perceived severity may be linked to euphemistic labelling. However, after accounting for the type of involvement, gender was not significant anymore, perhaps because aggressors could share the same values independently of whether they are boys or girls (Menesini et al., Citation2013).

According to our results, we may hypothesized that those engaged in all types of involvement are those that had the most maladaptive beliefs with respect to cyberbullying, both personal and normative beliefs, which puts them at risk of escalating cyberbullying incidents, and also of being a negative influence on their peers’ beliefs and consequently, their peers’ behaviour.

With respect to the bystander-victim group, it was the only group that did not differ from those who were engaged in all types of involvement in terms of personal moral beliefs and normative moral beliefs. We believe this may occur because sometimes victims may blame themselves for what they are suffering, and moral justification can be used in order to justify their aggressor’s behaviour (Schacter et al., Citation2015). Also, other studies (e.g. Runions et al., Citation2019) found that victims reported greater moral justification and victim blaming than uninvolved participants. Moreover, Parlangeli et al. (Citation2020) found that the use of moral disengagement in victims was significantly associated with positive emotions. That is, they may use these mechanisms to protect themselves, because thinking that someone will cyberbully them for no reason, could be even more painful. Therefore, the consequence of using these mechanisms may be that their personal and normative beliefs about cyberbullying become more morally flexible, which would make it easier to bypass their moral standards.

Process moral disengagement in cyberbullying

The content analysis allowed us to better understand the dynamics of cyberbullying and how moral disengagement occurred as a process within this specific immoral behaviour. For instance, Bakar (Citation2015) in his qualitative study found that adolescents considered antecedents when talking about cyberbullying, similarly to our process model of cyberbullying. Specifically, they found that adolescents attributed 4 types of antecedents, which were victim’s, aggressor’s, bystander’s and supporter’s online behaviour. Also, other authors (Ranney et al., Citation2020) investigated how students described their role in cyberbullying situations, and found that when describing online actions of aggressor-victims, participants tended to blame others for starting cyberbullying episodes. Thus, this supports the idea that blaming the victim is an antecedent, as we have classified it.

With respect to aggressors’ behaviour (Bakar, Citation2015), students mentioned ‘hatred’ and ‘getting even’ for something the victim might have done, which can be related to our category of moral justification, once again supporting our findings. Moreover, Ranney et al. (Citation2020) found that for describing the aggressor-victims actions, participants tended to morally justify their actions (e.g. ‘fighting back’ or ‘defending themselves or their friends’). In a different study (Wang et al., Citation2019), participants referred two motives for cyberbullying perpetration that could be related to moral justification, such as punishment (from something students did wrong at school) and revenge (from bullying episodes). Also, we complement Francisco and colleagues’ (Citation2015) findings, since ‘revenge regarding past episodes’ and ‘if someone abuses me, I can also abuse them’ was frequently referred to as motives for cyberbullying perpetration. Thus, these studies support moral justification as an antecedent of cyberbullying perpetration.

At the behaviour level, and considering the euphemistic labelling regarding seriousness, we complement Wang and colleagues’s (Citation2019) findings since they found that despite the offensiveness of the behaviour, it would be considered a joke or ‘just for fun’ if those who were involved were close, because the intentionality of harming was not present. Nonetheless, Francisco et al. (Citation2015) found the same motive ‘just for fun’ as being the most frequently mentioned by more than 50% of cyberbullies. Also, Bakar (Citation2015) discovered that ‘for fun’ was a theme that emerged when participants described cyberbullying. Considering the euphemistic labelling regarding normalization, to date no studies have focused on this subcategory. However, in our sample it was evident that seriousness and normalization were important in describing cyberbullying incidents. Nonetheless, the former appeared to be more important. With respect to advantageous comparison, it did not seem very frequent for students to use this moral disengagement mechanism, perhaps because they used euphemistic labelling with so much frequency, that they not feel the need to justify cyberbullying behaviour with other mechanisms.

Considering the consequents, we found that to justify the inaction of bystanders, participants resorted to the diffusion and displacement of responsibility, along with other attributions. These results add to the ones’ found in the meta-analysis from Lo Cricchio et al. (Citation2020), where passive bystanding was justified through the same mechanisms, but also by blaming the victim and dehumanization. However, blaming the victim was found to be related to aggressive bystander behaviour, as an antecedent. Furthermore, in our study, none of the participants mentioned dehumanization, and this can reveal that adolescents did not need to see the victim as a non-human ‘creature’ or a ‘monster’ in order to exonerate their conduct, and to allow them not to feel bad about their actions. However, it seems that when adolescents did not like someone, they perceived to have a valid excuse for hurting that individual, and this is why the category absence of affective bonding emerged from the content analysis, and may be considered a contribution to the literature on moral disengagement.

Personal and normative beliefs and moral disengagement mechanisms

In view of the significant and negative correlations between personal and normative beliefs assessed in study 1 and euphemistic labelling regarding seriousness and normalization, we consider that these are two of the most important mechanisms to work on in interventions, as they seem to have the most impact on participants’ perspectives. Our quantitative results highlighted that participants who tended to assess cyberbullying as less serious and less unfair, along with the corresponding normative beliefs, also used more euphemistic labelling to describe this phenomenon, as presented in our qualitative results.

Theoretical Contribution and Implications for Practice

The theoretical relevance of this study lies mainly in the deeper understanding of the role of moral disengagement in cyberbullying, particularly considering the perspective of participants as bystanders of the scenarios. This is imperative because our investigation enabled adolescents to have a voice (Dennehy et al., Citation2020), about a phenomenon where they are the persons of interest, and in which they have the deeper knowledge considering they are the ones involved in such situations. Moreover, this investigation allowed us to examine how adolescents used moral disengagement mechanisms, to justify both aggressors’ and bystanders’ behaviour in cyberbullying. Furthermore, it enabled us to view moral disengagement as a process in cyberbullying, considering that not all the mechanisms are activated at the same point in the cyberbullying cycle (Tillman et al., Citation2018). Particularly, we were able to identify specific mechanisms that were used to justify aggressors’ behaviour and bystanders’ aggressive intervention and non-intervention, and when they occurred in this cycle of cyber aggression. This is crucial in terms of practical implications, because by identifying the mechanisms that are most frequently activated for aggressors’ and bystanders’ behaviour, it is possible to design specific interventions for each different type of roles in cyberbullying.

Nonetheless, our results showed that those who engaged in all types of involvement had the most maladaptive beliefs about cyberbullying, thus it is the group that may need more intervention in this area. However, interventions with respect to cyberbullying should have a whole-school approach, since actions in schools can be more effective, as well as more systemic, and it is possible to create an ethos that does not support cyber (bullying), which is decisive in order to reduce these types of behaviour (Pearce et al., Citation2011). Moreover, whole-school approaches are important because of the gains from the intervention, which include all participants, but also for ethical reasons, participants should not be labelled as aggressors, victims or bystanders, when it comes to intervention.

Our results also showed that cyberbullying was not considered as serious as it actually is, by analysing the personal and normative beliefs of perceived severity, and also the frequency of verbalizations referring to euphemistic labelling regarding the seriousness of the situation. This highlights the importance of moral disengagement mechanisms, since change in moral disengagement and in the insidious conduct occur in a gradual and reciprocal way, over time (Bandura, Citation1999).

Furthermore, there is a need to create specific cyberbullying intervention programmes in Portugal considering that these programmes are more effective in reducing cyberbullying than prevention programmes related to general violence, and also anti-bullying programmes cannot serve as anti-cyberbullying programmes (Polanin et al., Citation2022). Moreover, this work provided us specific content of verbalizations that can be used for interventions with respect to moral disengagement, with the aim of reducing it, which has been suggested in the literature (Hood & Duffy, Citation2018). Our results underscore the importance of the self-regulatory process of moral disengagement, thus this points out to the possibility of developing wise interventions, since ‘they are wise to specific underlying psychological processes that contribute to social problems or prevent people from flourishing’ (Walton, Citation2014, p. 73), because it is essential to understand the psychological process that is being targeted and the effects of these interventions point to the fact that psychological processes act as the foundations of social problems (Walton, Citation2014).

In addition, with respect to both normative and personal beliefs our findings suggest that they can be included as other types of strategy for intervention in cyberbullying (Dang & Liu, Citation2020), or even a starting point in interventions (Peled et al., Citation2019). However, it is important to highlight that all prevention and intervention strategies need to be continuously evolving, along with the evolution of technology (Whittaker & Kowalski, Citation2015), in order to help youth engage in such programmes. Nonethless, a recent systematic review brought support for the effectiveness of cyberbullying prevention programmes (Polanin et al., Citation2022).

Finally, our investigation provided new insights on how moral disengagement can be assessed in adolescence, by specifying which moral disengagement mechanisms are more frequently used. This is a key issue considering that moral disengagement should be assessed according to the specificities of the subject (Bandura, Citation2015). This can be used for needs assessment, in terms of understanding which mechanisms should be counteracted. It can also be used for the evaluation of intervention programmes focused on decreasing the use of moral disengagement mechanisms in cyberbullying, with the aim of decreasing both aggressors’ and bystanders’ aggressive behaviour, and increasing bystanders’ prosocial behaviour.

Limitations and future research directions

Our study has some limitations. The inventory used was a self-report measure and the content from the interviews could be influenced by social desirability. The cross-sectional design did not allow us to understand how the several variables evolve in time, thus a longitudinal design would be needed. Furthermore, our classification of involvement patterns was based on mean cut-off values, however person-centred approaches are generally less vulnerable to distortion and misclassification, therefore cyberbullying involvement and patterns can be better understood if intensity and forms of aggression are taken into account (Festl et al., Citation2017).

With respect to future directions, considering that moral variables should be specific for cyberbullying behaviour (Allison & Bussey, Citation2017), thus becoming relevant to the phenomenon, a specific moral disengagement scale for cyberbullying situations should be developed. That is, it should account for the new insights from the qualitative study, including all moral disengagement mechanisms along with the devaluation of behavioural intentions and attributions. This allows us to capture the reality and perspective of adolescents regarding this phenomenon.

Furthermore, it would be interesting to analyse how personal and normative beliefs of all groups would evolve with a change in their involvement in these situations (Ang et al., Citation2011; Bastiaensens et al., Citation2016), and how moral disengagement mechanisms would change across time and different types of scenarios. This would allow us to design interventions focused on specific moral disengagement mechanisms, and accounting for their change across time, that could lead to higher adherence to intervention, as well as higher efficacy, due to similarity between intervention and daily challenges youth face.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that not all students involved in cyberbullying situations have the same needs regarding intervention strategies, because differences were found with respect to personal and normative beliefs. Thus, it is important to consider adolescents’ profiles in order to design effective intervention. For instance, those engaged in all types of involvement, presented the lowest values in all the beliefs that were analysed. That is, students from this group may need more training, specifically targeting maladaptative normative beliefs, since these type of beliefs are more related to cyberbullying intentionality (Lazuras et al., Citation2013), and cyberbullying perpetration (Peled et al., Citation2019).

With respect to the moral disengagement mechanisms that come to play in cyberbullying, our data showed that the diffusion of responsibility and the displacement of responsibility do not seem relevant for participants when talking about aggressors’ behaviour, as it was originally stated by Bandura (Citation2002) regarding anti-social conduct. Moreover, dehumanization was not present in adolescents’ discourse regarding the cyberbullying scenarios. These differences should be further analysed in order to understand why this occurred related to a different phenomenon. Therefore, our study has provided new insights regarding how moral disengagement mechanisms are present in the cyberbullying cycle, highlighting that it is important to adapt interventions to this process, considering the specificities of moral disengagement and its focus (i.e. aggressors’ and bystanders’ behaviour).

Despite the pioneering importance of the Social Cognitive Theory of Moral Agency, and specifically the concept of moral disengagement, our findings seem to demonstrate that this theoretical background is important but other findings can contribute to this theory. For example, Tillman et al. (Citation2018) put forth that moral disengagement mechanisms may be put into practice before and after committing an unethical act. Accordingly, the participants in our study spontaneously talked about the cyberbullying scenarios, which seems to corroborate our propositions, since some moral disengagement mechanisms tend to occur at the antecedents level, at the behaviour level, and finally at the consequent level. Thus, investigation on moral disengagement in cyberbullying should take into account these specificities, and consider moral disengagement as a process within the cyberbullying cycle.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sofia M. Francisco

Sofia M. Francisco, MSc, is an educational psychologist, has a MSc in Educational Psychology (Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon; FPUL). She is currently a PhD student in Educational Psychology, and member of the Pro-Adapt group of the Research Center for Psychological Science (CICPSI, FPUL). Her main research interests include Peer violence/promoting coexistence and student well-being, Bullying and Cyberbullying; Cross-cultural studies in the field of school violence in different educational levels; Promotion of essential socio-emotional skills to deal with bullying situations/cyberbullying.

Paula C. Ferreira

Paula C. Ferreira, PhD, is a researcher in Educational Psychology at the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Lisbon (FPUL). She has a PhD in Educational Psychology. She is a member of the group Pro-Adapt of the Research Center for Psychological Science (CICPSI, FPUL) in the area of Educational Psychology. She is also responsible for the Cyberbullying Study Programme. Her main research interests are self-regulated learning, violence in educational contexts, bullying and cyberbullying, teacher training, serious games and artificial intelligence.

Ana M. Veiga Simão

Ana M. Veiga Simão, PhD, is a Full Professor at the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Lisbon (FPUL). She is also the coordinator of the Interuniversity Doctoral Program (Coimbra-Lisboa) in Educational Psychology, and member of the Pro-Adapt group of the Research Center for Psychological Science (CICPSI, FPUL). Her main research interests are the processes of self-regulated learning, professional development of teachers, teaching in Higher Education, violence in educational contexts, bullying and cyberbullying.

References

- Abbasi, S., Naseem, A., Shamim, A., & Qureshi, M. A. (2018). An empirical Investigation of Motives, Nature and online Sources of Cyberbullying. 14th International Conference on Emerging Technologies (ICET), 1–6.

- Allison, K. R., & Bussey, K. (2017). Individual and collective moral influences on intervention in cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 74, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.019

- Almeida, A., Correia, I., & Marinho, S. (2009). Moral disengagement, normative beliefs of peer group, and attitudes regarding roles in bullying. Journal of School Violence, 9(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220903185639

- Amado, J., Costa, A. P., & Crusoé, N. (2014). A técnica de análise de conteúdo [the content analysis technique. In J. Amado (Ed.), Manual de investigação qualitativa em educação (2nd ed., pp. 301–348). Coimbra University Press.

- Ang, R. P., Tan, K., & Mansor, A. T. (2011). Normative beliefs about aggression as a mediator of narcissistic exploitativeness and cyberbullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(13), 2619–2634. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510388286

- Arsenio, W. F., & Lemerise, E. A. (2004). Aggression and moral development: Integrating social information processing and moral domain models. Child Development, 75(4), 987–1002. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00720.x

- Bacchini, D., De Angelis, G., Affuso, G., & Brugman, D. (2016). The structure of self-serving cognitive distortions. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 49(2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175615596779

- Bakar, H. S. A. (2015). The emergence themes of cyberbullying among adolescences. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 20(4), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2014.992027

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In M. K. William & L. G. Jacob (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development (Vol. 1, pp. 45–103). Erlbaum.

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

- Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724022014322

- Bandura, A. (2015). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth.

- Barlett, C., & Coyne, S. M. (2014). A meta-analysis of sex differences in cyber-bullying behavior: The moderating role of age. Aggressive Behavior, 40(5), 474–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21555

- Bastiaensens, S., Pabian, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2016). From normative influence to social pressure: How relevant others affect whether bystanders join in cyberbullying. Social Development, 25(1), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12134

- Betts, L. R., & Spenser, K. A. (2017). People think it’s a harmless joke”: Young people’s understanding of the impact of technology, digital vulnerability and cyberbullying in the United Kingdom. Journal of Children and Media, 11(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2016.1233893

- Burton, K. A., Florell, D., & Wygant, D. B. (2012). The role of peer attachment and normative beliefs about aggression on traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Psychology in the Schools, 50(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21663

- Bussey, K., Fitzpatrick, S., & Raman, A. (2015). The role of moral disengagement and self-efficacy in cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 14(1), 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.954045

- Chan, T. K. H., Cheung, C. M. K., & Lee, Z. W. Y. (2021). Cyberbullying on social networking sites: A literature review and future research directions. Information & Management, 58(2), 103411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2020.103411

- Dang, J., & Liu, L. (2020). When peer norms work? Coherent groups facilitate normative influences on cyber aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 46(6), 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21920

- Dennehy, R., Meaney, S., Walsh, K. A., Sinnott, C., Cronin, M., & Arensman, E. (2020). Young people’s conceptualizations of the nature of cyberbullying: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 51, 101379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101379

- Ellemers, E., Toorn, N., Paunov, Y., & Leeuwen, T. (2019). The Psychology of Morality: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Studies Published from 1940 Through 2017. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(4), 332–366.

- Ferreira, P. C., Simão, A. M. V., Paiva, A., & Ferreira, A. (2020). Responsive bystander behaviour in cyberbullying: A path through self-efficacy. Behaviour & Information Technology, 39(5):511–524.

- Festl, R., Vogelgesang, J., Scharkow, M., & Quandt, T. (2017). Longitudinal patterns of involvement in cyberbullying: Results from a Latent Transition Analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.027

- Francisco, S. M., Veiga Simão, A. M., Ferreira, P. C., & Martins, M. J. D. D. (2015). Cyberbullying: The hidden side of college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.045

- Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21502

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2015). Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Hood, M., & Duffy, A. L. (2018). Understanding the relationship between cyber-victimisation and cyber-bullying on Social Network Sites: The role of moderating factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.004

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Hymel, S., Rocke-Henderson, N., & Bonanno, R. A. (2005). Moral Disengagement : A framework for understanding bullying among adolescents. Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 33–43.

- Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073–1137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618

- Kremling, J., & Parker, A. M. S. (2018). Cyberspace, cybersecurity, and cybercrime. Sage.

- Lapinski, M. K., & Rimal, R. N. (2005). An explication of social norms. Communication Theory, 15(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00329.x

- Lazuras, L., Barkoukis, V., Ourda, D., & Tsorbatzoudis, H. (2013). A process model of cyberbullying in adolescence. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 881–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.015

- Lo Cricchio, M. G., García-Poole, C., Te Brinke, L. W., Bianchi, D., & Menesini, E. (2020). Moral disengagement and cyberbullying involvement: A systematic review. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(2), 271–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1782186

- Lozano-Blasco, R., Cortés-Pascual, A., & Latorre-Martínez, M. P. (2020). Being a cybervictim and a cyberbully – The duality of cyberbullying: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106444

- Luo, A., & Bussey, K. (2019). The selectivity of moral disengagement in defenders of cyberbullying: Contextual moral disengagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.038

- Macháčková, H., & Pfetsch, J. (2016). Bystanders’ responses to offline bullying and cyberbullying: The role of empathy and normative beliefs about aggression. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12277

- McGraw, K. O., & Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30

- Mendinburu, F. (2021). Agricolae: Statistical procedures for agricultural research [Computer software manual]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/agricolae/index.html(Rpackage version1.3-5). R package version

- Menesini, E., Nocentini, A., & Camodeca, M. (2013). Morality, values, traditional bullying, and cyberbullying in adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02066.x

- Myers, C.-A., & Cowie, H. (2019). Cyberbullying across the lifespan of education: issues and interventions from school to university. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071217

- Parlangeli, O., Marchgiani, E., Guidi, S., Bracci, M., Andreadis, A., & Zambon, R. (2020). I do it because I feel that … Moral disengagement and emotions in cyberbullying and cybervictimisation. In: G. Meiselwitz (eds.) Proceedings, Part I: 12th International Conference on Social Computing and Social Media, pp. 289–304. Springer, Cham.

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2006). Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 4, 148–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204006286288

- Pearce, N., Cross, D., Monks, H., Waters, S., & Falconer, S. (2011). Current evidence of best practice in whole-school bullying intervention and its potential to inform cyberbullying interventions. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 21(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.21.1.1

- Peled, Y., Medvin, M. B., Pieterse, E., & Domanski, L. (2019). Normative beliefs about cyberbullying: Comparisons of Israeli and U.S. youth. Helyon, 5, 1–8.

- Perren, S., & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2012). Cyberbullying and traditional bullying in adolescence: Differential roles of moral disengagement, moral emotions, and moral values. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(2), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2011.643168

- Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., Grotpeter, J. K., Ingram, K., Michaelson, L., Spinney, E., Valido, A., Sheikh, A. E., Torgal, C., & Robinson, L. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to decrease cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Prevention Science, 23, 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01259-y

- Ranney, M. L., Pittman, S. K., Riese, A., Koehler, C., Ybarra, M. L., Cunningham, R. M., Spirito, A., & Rosen, R. K. (2020). What counts?: A qualitative study of adolescents’ lived experience with online victimization and cyberbullying. Academic Pediatrics, 20(4), 485–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.11.001

- Romera, E. M., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Runions, K., & Falla, D. (2021). Moral disengagement strategies in online and offline bullying. Psychosocial Intervention, 30(2), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a21

- Runions, K. C., Shaw, T., Bussey, K., Thornberg, R., Salmivalli, C., & Cross, D. S. (2019). Moral disengagement of pure bullies and bully/victims: shared and distinct mechanisms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1835–1848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01067-2

- Schacter, H. L., White, S. J., Chang, V. Y., & Juvonen, J. (2015). “Why me?”: Characterological self-blame and continued victimization in the first year of middle school. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(3), 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.865194

- Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Göbel, K., Scheithauer, H., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Tsorbatzoudis, H., Barkoukis, V., Pyżalski, J., Plichta, P., Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Thompson, F., & Smith, P. K. (2015). A comparison of classification approaches for cyberbullying and traditional bullying using data from six European countries. Journal of School Violence, 14(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.961067

- Shapka, J. D., Onditi, H. Z., Collie, R. J., & Lapidot-Lefler, N. (2018). Cyberbullying and cybervictimization within a cross-cultural context: a study of canadian and tanzanian adolescents. Child Development, 89(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12829

- Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

- Smith, P. K., & Slonje, R. (2010). Cyberbullying: The nature and extent of a new kind of bullying, in and out of school. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective. Routledge.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

- Talwar, V., Gomez-Garibello, C., & Shariff, S. (2014). Adolescents’ moral evaluations and ratings of cyberbullying: The effect of veracity and intentionality behind the event. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.046

- Tillman, C. J., Gonzalez, K., Whitman, M. V., Crawford, W. S., & Hood, A. C. (2018). A multi-functional view of moral disengagement: Exploring the effects of learning the consequences. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(2286). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02286

- Tokunaga, R. S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

- Veiga Simão, A. M., Ferreira, P., Francisco, S. M., Paulino, P., & de Souza, S. B. (2018). Cyberbullying: Shaping the use of verbal aggression through normative moral beliefs and self-efficacy. New Media & Society, 20,(12),4787–4806.

- Walton, G. M. (2014). The new science of wise psychological interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413512856

- Wang, X., Lei, L., Liu, D., & Hu, H. (2016). Moderating effects of moral reasoning and gender on the relation between moral disengagement and cyberbullying in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 244–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.056

- Wang, C.-W., Musumari, P. M., Techasrivichien, T., Suguimoto, S. P., Chan, -C.-C., OnoKihara, M., Kihara, M., & Nakayama, T. (2019). “I felt angry, but I couldn’t do anything about it”: A qualitative study of cyberbullying among Taiwanese high school students. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 654. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7005-9

- Whittaker, E., & Kowalski, R. M. (2015). Cyberbullying via social media. Journal of School Violence, 14, 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.949377

- Willard, N. E. (2007). Cyberbullying and cyberthreats: Responding to the challenge of online social aggression, threats, and distress. Research Press.

- Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.018

- Zhao, L., & Yu, J. (2021). A meta-analytic review of moral disengagement and cyberbullying. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 681299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.681299

Appendix A

Type of responses in Personal moral beliefs about cyberbullying behaviour and Normative moral beliefs about cyberbullying behaviour

Regarding the type of response of these scales, despite the possibility of social desirable responses, we chose fair or unfair because current knowledge on moral reasoning is mostly related to abstract principles, such as fairness by which people adhere (Ellemers et al., Citation2019).

Type of responses in Personal beliefs of perceived severity about cyberbullying behaviour and Normative beliefs of perceived severity about cyberbullying behaviour

As for the option between a joke or serious in these scales, several studies have indicated that one of the main motives to engage in cyberbullying behaviour is ‘just for fun’ (Francisco et al., Citation2015) and students also use content from cyberbullying incidents they observe (i.e. example item ‘I used the content to play around with my friends’; Veiga Simão et al., Citation2018), which demonstrates that they frequently tend to consider cyberbullying behaviour amusing.

Appendix B

Cyberbullying Scenario 1 (in Portuguese)

Cyberbullying Scenario 2 (in Portuguese)

Cyberbullying scenario 3 (in Portuguese)

Appendix C

Assumptions for Hierarchical linear regression

For All Personal and normative beliefs scales: