ABSTRACT

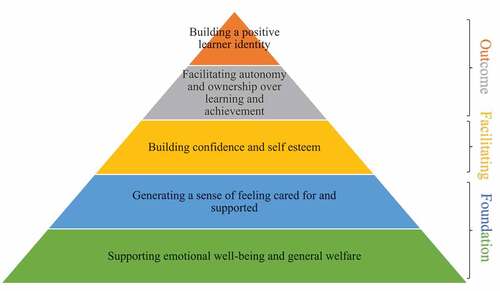

Tackling NEEThood remains a major UK policy focus, with numbers of young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) stubbornly high and the COVID-19 Pandemic exacerbating school disengagement and widening inequalities. Drawing on rich qualitative data from a three-year study evaluating educational interventions tackling NEEThood, this paper explores such interventions were successful from the perspectives of the young people and their educators. We introduce five mechanisms underpinning effective support strategies, arguing that these enable a pathway to change for young people. We distinguish between foundational mechanisms, essential at the outset of work with young people, facilitating mechanisms which build on these foundations, and outcome-generating mechanisms which lead to education and work goals. These findings underscore the importance of tackling the social aspects of educational disengagement, as well as the critical role of advocacy and support from an adult who can unpick the complex barriers to engagement and learning.

Introduction

The ambition to reduce the rates of early school leaving (ESL) remains a key policy focus across Europe. Most developed economies face ongoing challenges around youth transitions from education to the labour market, with growing numbers spending long periods outside education, employment or training and facing economic and social exclusion (Maguire, Citation2021). However, the term is little used in the UK where policy focuses rather on reducing the rates of young people not in employment education or training (NEET; Maguire, Citation2021). This paper draws on the UK findings of a wider study across five European nations (Spain, Germany, Romania, Portugal and UK) which aimed to understand and intervene on ESL by designing, implementing and evaluating intervention strategies tailored to the local region. Educators involved in the UK study were all working to support the educational participation or re-engagement of young people aged 12 to 21. All young people had either not finished, -or were at risk of not finishing, -lower secondary education, or had not made, -or were at risk of not making, -a transition to upper-secondary education. Early School Leaving was not a term recognized by the educators in our study, who attributed to themselves an assigned responsibility for reducing NEEThood. While we acknowledge the contested nature of the term NEET (Holte 2017, Kleif 2020, MacDonald 2011) our use of the concept reflects our engagement with participants’ practice-based responses to educational disengagement and difficult transitions, in order to tackle ESL as one aspect of NEEThood.

At the start of the project, the EU Commissions’ target was for partner nations to reduce ESL rates to below 10% by 2020 (Eurostat, Citation2020). At this time, the UK registered the second lowest rate of the five countries involved at 10.6%, slightly higher than Germany at 10.1% and significantly lower than Portugal, Romania and Spain who ranged between 17.4% and 18.3%. More recently, the European Education Area (EEA) 2030 framework proposes a new ambition: to further reduce early leaving rates to below 9% by 2030 (Eurostat, Citation2020; Psifidou et al., Citation2022). Of the 31 EU countries 19 are already below this threshold (Eurostat, Citation2020), including Portugal, demonstrating the effectiveness of national interventions. Having left the EU, however, the UK figures are no longer reported by the European commission, but national figures show that NEET rates (16–24) have not significantly altered in the period and currently stand at 10.4% (Office for National Statistics, Citation2022 April–June)

While the UK has relatively low NEET rates in comparison with some other European nations, it also has a less cohesive and developed approach to tackling early leaving than the other four other countries involved in the study. This may in part explain why the UK has not achieved the success of other nations in reducing the number of young people who are NEET. Spain, for instance, has more formalized routes to re-engagement in Vocational Education and Training, with a national strategy for tackling ESL (Brown et al., Citation2021). In contrast, England has no stand-alone strategy to tackle NEEThood (Maguire, Citation2021) with each of the four UK nations adopting different policies and approaches. Alternative provision (AP) for vulnerable and excluded learners is unregulated by any statutory framework and lacks stable funding, resulting in ‘poor oversight, inconsistency across local authorities, and complex processes for children and young people and families to navigate’ (Department for Education, Citation2022, p. 63). AP is defined as:

Education arranged by local authorities for pupils who, because of exclusion, illness or other reasons, would not otherwise receive suitable education; education arranged by schools for pupils on a fixed period exclusion; and pupils being directed by schools to off-site provision to improve their behaviour. (Department for Education, Citation2017, p. 11)

It covers a very broad range of institutions including Pupil Referral Units (PRU) for students excluded from school, independent schools, charities, further education colleges, businesses, medical tuition and hospital schools (Department for Education, Citation2017). The support on offer may be therapeutic, targeted at a specific educational need or vocational learning, with students attending full time, part time or for a fixed term. (Department for Education, Citation2017)

Despite the slight reduction in NEET rates reported in the UK (ONS 10.4% Apr to Jun 2022 down from ONS 11.3% January to March 2020), recent research and reports from not-for-profit organizations raise alarm bells about serious long-term problems masked by these statistics (Goulden, Citation2021; Williams et al., Citation2021); the coherence and adequacy of the UK’s policy responses to effectively tackle NEEThood (Maguire, Citation2021); and the negative impacts of pandemic-related school closures on the life-chances and livelihoods of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds and marginalized groups (Education Endowment Foundation, Citation2020; Hagell, Citation2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic widened the existing disadvantage gap (Education Endowment Foundation, Citation2020; Lally & Bermingham, Citation2020) and exacerbated inequalities (Hagell, Citation2021). While there is still little available evidence about actual learning loss from the COVID-19 pandemic (McDaid et al. Citation2021 p. 7), it is clear that impacts on educational disadvantage have been ‘variable and unpredictable’ (ibid), disproportionately impacting those with ‘existing vulnerabilities and cumulative multiple risk factors’ (p29). Experts warn that a decade’s progress in closing the attainment gap is likely to be reversed, with the estimated gap between disadvantaged young people and their peers growing by 36% (Education Endowment Foundation, Citation2020). Lockdowns and school closures during 2020 and 2021 amplified inequalities in attainment and progress (Antoni Citation2021; Blainey & Hannay, Citation2021; Maldonado & De Witte, Citation2020). The rapid move to remote learning during school closures has negatively impacted educational equity with in-person instruction shown to be comparatively more effective at ‘levelling the playing field’ than the. arrangements that education authorities were able to rapidly implement (Reimers et al, Citation2022, p. 64).

It has also accentuated the significance of the social, emotional and wellbeing support schools provide and the ‘interdependency of cognitive and socio-emotional learning’ (Remiers et al, Citation2022 , p. 3). Estimates suggest that between 10% and 20% of students ‘discontinued their school learning during the “remote learning” period in some countries’ (p. 405). Levels of severe absence (students missing more than half of their sessions) have increased 54.7% during that period in the UK (Centre for Social Justice n.d.). With absence levels over 10% during Key Stage 3/4 being a key characteristic of those who experience long-term NEET status (Department for Education, Citation2018; Powell, Citation2021), it is now more important than ever to develop strategies that support young people’s engagement in education/training and the community.

Government policy responses to mitigate the negative impacts of the pandemic on the educational outcomes of vulnerable and marginalized groups include educational recovery funding through boosting pupil premiums and catch-up tuition via schemes such as the National Tutoring Programme and the Academic Mentors Programme (Department for Education, Citation2021a and, Citation2021b). However, concerns have been voiced about the adequacy and effectiveness of these responses, particularly the availability of qualified staff to mentor students (Fazackerly, Citation2022; Mason, Citation2022; Yeoman, Citation2022) and how setting-based tutoring responses can benefit students who are regularly absent from school (Centre for Social Justice n.d.).

It is particularly concerning that the key policy responses to post-pandemic educational recovery fail to effectively target many of the young people most at risk of NEEThood, given recent critiques of the weaknesses and contradictions in the government’s existing approaches to addressing these issues. Maguire (Citation2021, p. 831) highlights the UK’s ‘scattergun approach to policymaking’ across its four nations, and the postcode lottery governing the nature, quality and amount of support that young people receive. In England in particular, the lack of government ownership and growing dependence on charities and not-for-profits for the delivery of interventions for young people who are NEET, mean that support can often be precarious and unsustainable due to its reliance on time-limited and EU-funding (Maguire, Citation2021).

Given the lack of consistency in the availability and form of support across the UK, accelerating work to effectively tackle the risks to NEEThood is an urgent priority. This paper reports on the findings from one such European-funded study propping up England’s policy response. We draw on the UK findings of a three-year international study, which aimed to understand and intervene on NEEThood by designing, implementing and evaluating an intervention strategy tailored to the local region. In drawing on interview, focus group and questionnaire data carried out with 28 educators and 82 young people, we explore the mechanisms that underpin effective support strategies to tackle the risk of becoming or remaining NEET and present an evidence-based ‘pathway to change’ that can support the strategies of a diverse set of educators.

Interlinked arenas of risk: unpicking the complexity of NEEThood

The complexity and multiplicity of the challenges facing those at risk of NEET is well documented (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019; Haugan et al., Citation2019; Olmos & Guerin, Citation2021; Soggiu et al., Citation2019) and best understood from a life-course perspective (Alexander et al., Citation2001) as a response to cumulative negative schooling experiences over time (Casillas et al., Citation2012; Lamb et al., Citation2010; Nelson & O’Donnel, Citation2012). Understanding and tackling NEEThood requires an ecological approach (Lörinc et al. Citation2020) and a conceptual model which can account for multiple nested and interrelated areas of risk (personal, social, institutional, familial, structural) while acknowledging the agency of young people in navigating and responding to these ‘binds’ (Brown, Citation2014; Brown et al., Citation2021). Such an approach tempers the potential hazard of misrecognizing risk factors that could lead to inappropriate and ineffective interventions. For instance, mental health problems can ‘camouflage’ social problems among NEET young people (Ose & Jensen, Citation2017, p. 155).

Experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic shed further light on possible factors impacting NEEThood by compounding the multiple challenges young people face. This amplified the chances of misrecognizing risks, leading to increased isolation and disengagement from society. For instance, the pandemic highlighted the digital divide facing disadvantaged and at-risk learners (Bawyer et al., Citation2021; Bonal & González, Citation2020). While facilitating access to digital devices and internet connection to ‘at risk’ youngsters was a widespread approach in the UK and across the world (OECD, Citation2020) those unable to receive timely support faced months unable to connect with friends, schools or support services. Furthermore, recent studies highlight that access to resources and services may not be sufficient to guarantee engagement and participation for those experiencing social exclusion (Cedefop, Citation2020, p. 4). The impact of social isolation and loneliness has been shown to be cumulative and reciprocal, with Sabato et al. (Citation2021) revealing that during lockdown and school closures, chronically lonely youngsters were less willing to help another young person experiencing loneliness. When a lack of social connection compromises wellbeing, the young person affected may lack the confidence to take up opportunities to connect with others. This underscores the need for further exploration of the social component to mental health challenges and how this may impact educational engagement.

In addition, the turbulence experienced by at-risk youngsters during the pandemic, coupled with pre-existing complexities in their daily lives, resulted in individual challenges being marginalized further while school staff focused on adapting provision for the general school population (Antoni Citation2021). This reaffirms the importance of educators having the capacity and capability to unpack and address the multiple factors that impact these young people’s trajectories (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019). Together, these examples illustrate how meaningful change depends upon support from a professional who can understand the ways that external factors can impact individual behaviours and emotional responses, make a critical evaluation of the effectiveness of the interventions on offer for a particular individual, and act as a catalyst for change. The following sections examine potential mechanisms to address these complexities, focusing particularly on the impact of individual guidance and support for young people at risk of NEEThood.

Indicative mechanisms for tackling NEEThood: mentoring and guidance

So far, we have argued that while there may be multiple factors that contribute to NEEThood, the closely interlinking nature of risk factors points to the importance of flexibility, understanding, knowledge and trust as key factors in the educator role to support young people (Montero-Sieburth & Turcatti, Citation2022; Nelson & O’Donnel, Citation2012; Nouwen & Clycq, Citation2019; Olmos & Guerin, Citation2021). Individual support, mentoring and guidance have been identified as essential strategies to support young people to avoid NEEThood (Olmos & Guerin, Citation2021), while teacher support has been found to be one of the most important strategies in addressing risks to NEEThood and fostering school engagement (Nouwen & Clycq, Citation2019). In order to accelerate efforts to support young people, it is important to develop an understanding of the processes underlying these strategies to address NEEThood.

Recent work has started to unpack the mechanisms for effectively tackling NEEThood. The ‘Breaking Cycles’ approach is a process for effecting changes in repeated, harmful behaviour (Centre for Social Justice n.d.), which is ‘built on a foundation of trust with a skilled practitioner investing time in building a relationship and overcoming the mistrust often associated with ‘officialdom’ (p. 9). Research into factors leading to successful progression at alternative provision settings posits that ‘experiencing a combining sense of autonomy, competence and relatedness’ results in an ‘aha moment’ for young people, enabling successful progression (Hamilton & Morgan, Citation2018, p. 80). Here, as with findings from Nouwen and Clycq (Citation2019, p. 1230) taking ownership is directly linked to feelings of ‘relatedness’.

This is echoed by Santos et al. who identify ‘turning points’ in young adults’ narratives of their educational experiences (Citation2020, p. 463). Among the support mechanisms, they recommend are socio-emotional support, relationships of care and aligning learning content with ‘students’ motivations and needs’ (ibid). These insights suggest that the young person’s sense of ownership and autonomy is facilitated through relationships and experiences where their interests and motivations are treated as a central and significant concern. As Pruano et al. (Citation2022) explain, ‘willingness and motivation are conditional on a sense of well-being,’ (p12). Improved understanding of how and why supportive relationships facilitate increased autonomy and motivation, contributing to educational re/engagement, is urgently needed to guide educators’ support more systematically.

We seek to further develop understanding of the mechanisms underpinning effective personalized support. This could help to ensure more consistent, coherent and effective support across all educational settings and give educators confidence that their efforts are informed by an evidence-based theoretical approach that is within their powers to address in their day-to-day interactions with young people.

Indicative mechanisms for tackling NEEThood: supportive educator-young person relationships

While positive student–teacher relationships within mainstream classrooms can act as a protective pull-factor (Krane et al., Citation2017), reintegration measures for young people who are already outside of education and training are likely to require more intensive relationship-building work. To design effective support strategies, the conditions required to enable positive relationships to develop need to first be understood. In these instances, caseload size is seen to be critical. One-to-one support is considered to be a vital feature of successful youth employment support to build ‘trust, continuity and more co-ordinated provision’ (Williams et al., Citation2021, p. 34). The Centre for Social Justice recommends the establishment of ‘keyworkers’ to work ‘intensively and consistently with young people in a pastoral context’ (n.d. p. 14). Previous evaluations of the approach highlight the ‘relatively low caseload (approximately 12 for a typical keyworker),’ as an important condition for success (ibid).

The sustainability of this support is also important (Maguire, Citation2021, p. 835). Being a ‘constant presence’ and ‘offering a stable point of focus’ are fundamental for keyworker roles (Centre for Social Justice Citationn.d. p9). Likewise, the ‘continuity of adviser’ is critical for young people who are long term unemployed, as are ‘physical spaces to access support’ (Centre for Social Justice Citationn.d. p35). These factors point to the importance of one-to-one or small group support conducted on an ongoing, longer-term basis in supporting the objective to resume education ‘under a different set of conditions from those that exiled young people from mainstream schools’ (Pruano et al., Citation2022, p. 11).

With multiple, interrelated issues and barriers to be unpicked and addressed, ongoing support from well-trained, familiar individuals with oversight and close communication with the various professionals involved in the young person’s life, is a vital ‘pre-requisite for change’ (Centre for Social Justice Citationn.d. p9). Effective interventions may depend on the skills and qualities of the practitioners who deliver them, so identifying the qualities found to be most effective in supporting young people at risk of becoming or remaining NEET is important. These include ‘highly skilled, supportive, motivated, understanding and available staff’ (Hamilton & Morgan, Citation2018, p. 89) who are ‘compassionate, empathetic, caring, non-judgemental, passionate, [and] understanding.’ Critically, they should show an ‘authentic interest’ in the young adults’ wellbeing and success’ (Centre for Social Justice Citationn.d. p9) and not be ‘another person with a clip-board’ added onto the existing raft of professionals already involved (p83). Young people identify a kind of disposition as critically important (Krane et al., Citation2017; Whitehead et al., Citation2022) with the following qualities encompassed: ‘caring, empathy, compassion, friendliness/warmth and helpfulness, generosity, trustworthiness, equal treatment and respect’ (Whitehead et al., Citation2022, p. 16).

While a strong pupil–educator relationship underpinned by the expression of such ‘qualities’ of the educator is well established in existing research, we seek to further probe how these qualities might be best employed within a systematic approach to addressing the risks to NEEThood. This paper examines the role of a skilled practitioner within a comprehensive theoretical model by introducing five mechanisms that lead to a ‘pathway to change’ by which educators can best support young people.

Methodology

This paper draws on data collected during a three-year research project funded by the European Commission (Orienta4YELFootnote1) between 2019 and 2022 to understand and intervene on NEEThood across five European nations. The project aimed to better understand the risks to Early Leaving (understood in the UK in the context of NEEThood) and to train and support educators in delivering and evaluating a range of intervention strategies to address these risks. The findings presented here come from the UK sample of the projects’ final phase which focused on evaluating the impact of interventions trialled within the local region. The aim of this phase of the study was to evaluate a range of interventions, rather than to test a specific conceptual framework.

Contexts and settings

The research was carried out in the context of two local authorities in South-West England that we have named Windy county and Sunny county. According to the most recent statistical data at the time of the data collection, both counties were in the lower quartile in terms of population density, with White British comprising a particularly high proportion of the population. Both are rural counties, with higher than national average levels of employment (see, ), and relatively poor transport links, making access to VET and alternative provisions difficult. While the proportion of 16–17 years olds who are NEET or unknown was higher than the national average in both counties, Windy county had no university and a greater proportion of young people whose activity is not known, while Sunny County had a higher proportion of young people known to be NEET (see ).

Table 1. Education participation and NEET figures for Windy and Sunny County (2021).

Table 2. Employment figures for Windy and Sunny CountyFootnote2.

A total of 110 participants across 11 settings took part in the intervention trialling and evaluation phases of the research: 2 Specialist Schools; 3 Alternative Education Providers; 2 Virtual Schools (providing educational support for children in care); 2 charity NEET provisions; 1 Local Authority NEET provision and 1 Vocational Education and Training Setting. These settings were involved with the project for a minimum of 18 months, with seven of them having been involved for three years, from the outset of the project. The settings were originally recruited via their respective local authority who provided guidance to the research team to approach individuals within settings with a reputation for productive work with young people who were at risk of disengagement or had disengaged from education. Disruption and additional pressures during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the withdrawal of four settings from Phase 1, whereby four new settings were recruited via direct approaches to both senior leaders and educators to participate in the intervention and evaluation phases. Mainstream secondary schools were particularly affected by this. All settings of this type withdrew, and the new settings recruited were each alternative provisions, either commissioned or independent providers meeting educational needs which are not met within the mainstream setting. The smaller providers who sustained their involvement or became involved in the later phases, worked in small groups or on a one-to-one basis with young people and had the flexibility to be able to adapt their work to continue to meet need during the pandemic. In contrast, educators from the mainstream secondaries who decided not to participate in the intervention and evaluation phase communicated that they no longer had the capacity and time necessary to do justice to the study.

Ethical Processes

As well as gaining university ethics approval, we worked closely with educators, settings and young people in aiming to make processes and participation as respectful and valuable for all parties as possible. The educators in each setting identified potential participants among the young people they worked with and made the initial approach. Their established rapport facilitated clarification of informed consent, enabled explanation of the research processes in more depth, and enabled communication with families/carers where further explanation was beneficial. The sample, therefore, includes only those young people who responded and assented to participate. Educators’ deep understanding of the young people shaped the data collection tools and processes to best fit young people’s needs and requirements, including appointing a translator or teaching assistant to support communication or substituting telephone calls for zoom calls for those who preferred visual anonymity or simply the medium. Participants were reminded at the start of each interaction that there was no obligation to contribute, that they would be assigned a pseudonym in all textual outputs and data files, and that all identifying detail would be omitted to protect their identities.

With the intervention and evaluation phase of the research taking place during the COVID-19 pandemic, the educators themselves were under unprecedented pressure. We were mindful to minimize both the additional workload associated with participation and the risk of drop-out. Offering the educators regular online drop-in meetings during which they could access support, advice and inspiration from each other and from the research team was universally acknowledged to have offered valuable connection, community and professional inspiration.

Dataset

Social distancing requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic required the majority of fieldwork to be conducted remotely, although face-to-face focus groups with young people were possible in two settings. The dataset comprises the following:

2 focus groups and 10 interviews with 18 young people aged 12–16 at risk of EL (9 boys; 9 girls)

127 questionnaires/surveys carried out with 64 young people at risk of EL

25 focus groups/interviews with 19 educators, tutors and support workers

8 focus groups/interviews with 9 Senior Leaders

Analysis

Interviews and focus group recordings were professionally transcribed and entered into the qualitative data organization software NVivo 12. Four researchers took a qualitative exploratory design (Nieuwenhuis, Citation2015, p. 420) to analyse the data, guided by the theoretical framework developed in the first phase of the research project, which identified five distinct categories of risk which can lead or contribute to EL: personal challenges, family circumstances, social relationships, institutional features of school and work and structural factors, such as economic disadvantage, policy and systemic educational approaches (Brown et al. Citation2021). We undertook directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005); before analysing any data from this phase, in creating 169 codes, drawn from prior analysis of risk factors in Phase 1. As the analysis proceeded, further codes and sub-codes were developed. These increased to 316 codes which were distributed across the parent codes and 6 child codes as exemplified in .

Table 3. Examples of the development of child codes within ‘Support Strategies’.

With so many support factors emerging from the discussion of diverse interventions applied within varied settings, we looked for putative generative mechanisms (Haig 1987) that were relevant across the dataset that could explain why the strategies were effective. We then returned to our educators and young people to corroborate these findings and discuss and theorize their inter-relation in leading to a ‘pathway to change’.

Data and findings

This section outlines the strategies and factors that were most discussed by educators and young people as effective in supporting young people who are/at risk of becoming NEET (see, ). Following this, we present the five mechanisms that emerged from our analysis of the discussion of these strategies (see ) using illustrative examples from across the dataset.

Table 4. Most discussed support strategies for effective interventions with young people who are NEET or at risk of NEET.

The most commonly discussed strategies all addressed these three risk categories: personal challenges, social relationships and institutional factors. Only one of the 11 settings selected a focus specifically targeting family circumstances. During the first phase of the research, the risk category most discussed by educators was that of ‘structural factors,’ such as policy, resourcing and funding (Brown et al. Citation2022). As we agreed with our educators that it was not within their power to address these wider forces in the course of their work with young people, however, the interventions reported here address only risk factors associated with personal challenges, social relationships, institutional features and family circumstances. These strategies will be discussed in more detail in the context of the five underpinning mechanisms that emerge from the analysis.

Five mechanisms for tackling NEEThood: considering the support strategies in context

This section outlines the five theoretical mechanisms we identified and corroborated, which explained how and why the various strategies were effective. As can be seen in the following model () each of the mechanisms represents a component of support giving which leads to the overall objective of re/engagement in education/training and work. Taken together, these five mechanisms represent incremental steps towards a ‘pathway for change’Footnote3 by which the young person can re/engage with society.

Mechanism 1: Supporting emotional wellbeing and general welfare

Wellbeing or welfare challenges were the most reported issue raised by young people: ‘we’re all here because we’ve got some sort of anxiety or problem’. In questionnaires, young people frequently attributed the success of the intervention to ‘improved mental health and motivation.’ When discussing this, the ‘qualities of the educator’ (see ) were pivotal for young people who identified the advocacy of a persistent, supportive adult to be a fundamental starting place: ‘they didn’t give up on me, even when I was hard to get hold of, they … found a way to keep me on track.’

Educators also foregrounded the importance of supporting any well-being/welfare concerns addressing young people’s welfare-specific needs (see ): ‘you’ve got to put it into the context of their life and if there’s other issues arise, or other needs that need to be met, maths will be secondary.’ Supporting wellbeing was seen to be important because it demonstrated care to the young people, many of whom had become accustomed to not having their needs met and required help to unpick and address their issues: ‘to be able to go, “actually I struggle with this” and “what I was struggling with in school was the crowds … ” and then I could pass that on to her CAMHS worker and pass that onto the school.’ Supporting wellbeing here was not understood purely in a clinical sense, but very often through small mechanisms to support young people’s social involvement or coping with social challenges. Small-scale interventions such as accompanying them on the journey to school, discussing friendship issues or ensuring interactions were on a forum that felt manageable for the young person (online, text chat or face-to-face), were understood to have a cumulative impact.

The impact of the social distancing restrictions and school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic had a mixed impact on the ways in which wellbeing was supported. For some young people, the accelerated shift to online support through platforms such as Microsoft Teams and Zoom facilitated relationship building by removing both the emotional toll and physical risks of face-to-face contact,

‘it’s been a lifeline, the tutoring and actually, the lockdown was helpful because it safeguarded me from him and it actually enabled us to talk online or on the phone and it took away that anxiety of being next to somebody in a room, which he finds really difficult.’ (educator reporting experiences with an autistic young person)

For other young people however, specialist health or education needs, or family caring obligations compromised young people’s access to education, as well as educator support, increasing the challenge to meet wellbeing and welfare needs. Notwithstanding the disparity in young people’s experiences of the pandemic, educators were unanimous in the belief that finding low engagement ways to maintain contact, such as online quizzes, offered a lifeline to counter a reported surge in mental health challenges, a sentiment that was endorsed by young people themselves; ‘it [weekly online quiz] gave me a purpose in a time where I just would not get out of bed.’

Mechanism 2: Generating a sense of feeling cared for and supported

Familiarity with an educator who would help them with the wider aspects of their lives was highlighted by young people as integral. One-to-one and small group work helped them feel ‘safe and secure’. Facilitating a trusting relationship with an educator who ‘proper gets me’ and will ‘have a chat when I’m having a bad day,’ led to young people feeling supported (see, ) and cared for.

Educators explained that showing an interest and involvement in their day-to-day lives was seen to be a foundational process: ‘building that rapport and chatting about what they’re having for dinner … is just as important as the actual education-based session because it was all part of that building trust before the learning could take place.’ They argued that young people needed to feel that an educator was on their side to trust that the supporting adult (see ) cared enough to value their participation. Not being noticed, recognized and attended to was seen to have a cumulative negative effect during large group teaching: ‘you can really see how, if they don’t have any one-to-one support, she would just be going under the radar.’

Some educators had played a key role in mobilizing funds for ICT equipment, as part of the national government’s COVID-19 response to facilitate learning and communication during the stay-at-home order. For those young people who lacked sufficient ICT expertise however, the value was limited;

‘we organised laptops for them from the Department of Education, the free laptops, but … you couldn’t put Microsoft Office on them … so they just chucked them in the corner of the room, they’re useless’.

In meeting such challenges, educators reported the need for flexibility and creativity in retaining contact. Using multi-media platforms with which young people were familiar with (e.g. Skype), rather than platforms proposed by the local education authority (e.g. Microsoft Teams), phone calls, and instant messaging platforms, as well as contriving fun and light-hearted engagement opportunities such as online karaoke nights, or film club were examples of way that they prioritized ‘opportunities to engage’ at all costs to counter the isolation young people experienced through the pandemic. Explaining their successful ongoing contact with their young people, one service leader explained, ‘it’s not a reflection of the activities, it’s a reflection of the relationship with staff and the other young people, that’s why they’re engaging’.

Mechanism 3: Building confidence and self esteem

For both young people and educators, improving confidence and self-esteem was frequently attributed to be an outcome of the first two mechanisms. This suggested a process whereby supporting wellbeing (see ) and generating a sense of feeling cared for were seen to be foundational mechanisms;

“when you increase their emotional wellbeing and welfare, everything starts to flow. So it improves their self-esteem.”

“if they doubt themselves and they don’t feel confident, they won’t engage as much in lessons.”

One-to-one support (see ) was viewed to be important in allowing the flexibility (ibid) necessary to build confidence. This was understood to work in a range of ways, from helping young people feel ‘a little bit more that they’re worth something,’ to being able to progress at a comfortable pace for the young person: ‘it’s got to be led by them and you just can’t force that.’ Exploring personalized pathways for education and work (see ) was pinpointed as central to confidence building, whether that was from developing ‘familiarity with what a college setting might look like,’ or flexibly adapting (see ) the way that young people could engage with the educational provision: ‘[one] young person still doesn’t feel confident enough to come onto camera or even voice chat. It’s all type chat.’

Young people highlighted the social dimension of self-confidence, explaining that the support had helped them ‘socialise a bit more and be more confident,’ ‘meet new friends and see them,’ ‘be more social’, ‘meet new people my own age and have fun outside home,’ and in ‘getting out of the house’ and ‘being around new people.’

Mechanism 4: Facilitating autonomy and ownership over learning and achievement

The efforts that educators made to maintain relationships with the young people during stay-at-home orders could be seen to bear fruit following the easing of social distancing measures. Enabling young people to develop a sense of ownership over their future pathways (see ) was a frequently mentioned outcome of successful interventions and a consequence of increasing confidence and trust in themselves and their supporting adults. Young peoples’ comments highlighted the increased educational aspirations that led on from an acquired self-belief in the ability to envisage educational and work pathways (see, ) for themselves:

“at first I was like, oh my god … I am going to fail … but now I have support and I understand all of the things I’ve got to do.”

‘I know I can do it’

‘I changed my mind about going to college,’

The reasons that young people attributed to raised aspirations were invariably linked to the realization that non-linear and alternative trajectories existed and were possible: ‘talking through it made the plan clearer and set it in stone,’ and ‘my way of learning isn’t wrong, it’s just different.’ Meeting their needs and the educator’s flexibility to personalize support (see, ) enabled young people to conceptualize pathways that were relevant for them.

Educators flagged the importance of a flexible (see ) personalized approach in supporting autonomy and ownership: ‘for some young people it’s the first time that [educational] relationships [are] built on trust and individual ownership and individual target setting, and are not driven by a statutory outcome.’ They also highlighted the careful path that needed to be trodden between raising aspirations and keeping hopes realistic, describing a ‘balance between wanting to empower young people to have these aspirations about the future, but actually if they were unrealistic, they could almost be negative, so that was a key role, trying to mediate this ground.’ In summary, they acknowledged that, ‘they’ve got to be able to feel some autonomy to choose rather than [seeing] education as just something that is done to them.’

Mechanism 5: Building a positive learner identity

Finally, educators commented on the important identity work facilitated in their settings and interventions. Building a sense of belonging and fitting in for the young person was viewed to be the ultimate mechanism for generating participation or re-engagement with educational and work goals: ‘it’s really important for them to see students a little bit like them, even though they might speak a different language or be from a different culture, I think they recognise when they see themselves and they’re in the right place.’

Having the confidence to explore a different identity or make education and work goals part of their current sense-of-self were discussed to be important processes in leading to change for these young people. One educator explained, ‘we end up pigeon-holing ourselves through our actions and the way that we are within work or school environments. An [intervention] like this allows young people to perhaps learn to portray themselves in a different way … and quite often the young people we’re working with struggle in school because their identity is already set.’

A pathway to change: the interaction between the five mechanisms

In this section, we discuss how the five mechanisms identified by the research interacted to generate a pathway to change, drawing upon and developing existing knowledge about tackling NEEThood. In so doing, we discuss the model () in terms of the three core functions performed in generating a pathway to change, named, respectively, foundation, facilitating, and outcome generating mechanisms.

Foundation mechanisms: meeting needs and generating a sense of being cared for

The first two mechanisms can be characterized as foundation processes, which educators understood to be essential to address at the outset of working with the young person (see ). Given the complexity of the young people’s needs, educators were adamant that addressing an individual’s emotional and physical wellbeing needs was a first step, as until these core needs had been met, young people were unable to contemplate education or work goals. Echoing the literature, wellbeing needs were frequently the most highly reported personal challenge (Banks & Smyth, Citation2021; Brown et al., Citation2021) and those most urgent to meet in a post-pandemic context (Braziene 2021).

To a certain extent, the pandemic may have foregrounded and exacerbated this aspect of educators’ work, with young people further isolated through stay-at-home orders, needing comparatively more input. Nevertheless, in terms of addressing these needs, there was a strong sense that Alternative Providers and educators from Specialist schools catering to those with SEND, prioritized and stepped-up to meet these needs where educators in mainstream schools were busy dealing with large cohorts and maintaining academic rigour, losing sight of the particular needs of more disadvantaged learners around different forms and styles of contact.

Identifying and ameliorating wellbeing needs were seen to lead on to the second mechanism, generating a sense of feeling cared for, as two foundational steps towards developing trusting relationships between the young person and educator. Positive adult-child interpersonal relationships have been identified as a critical factor for promoting school re-engagement for at-risk young people (Banks & Smyth, Citation2021; Nelson & O’Donnel, Citation2012) and as a motivator for staying in school for those with mental health problems (Krane et al., Citation2017). Research with at-risk young people has highlighted the contingency of emotional support upon students’ sense of feeling valued and respected (Hoy & Weinstein, Citation2006; Studsrød & Bru, Citation2011 in Krane et al., Citation2017, p. 378) thereby demonstrating that young people may not divulge their needs unless they perceive a genuine sense of concern from the educator. Our findings build upon recent research highlighting that ‘subtle, daily contact and connections’ were instrumental in enabling students to feel valued (Banks & Smyth, Citation2021). Research shows that many well-being, welfare, and educational needs can be recognized as a response to institutional rigidity, therefore highlighting the importance of an individualized and tailored response (Hodgson, Citation2007; Santos et al., Citation2020) such as regular calls or messages and online social activities to maintain a connection.

Our findings advance those of recent studies concerning the importance of understanding the affective experiences of NEET youth (Ryan et al., Citation2019) and the positive impact of interpersonal relationships on their educational re-engagement (Banks & Smyth, Citation2021). Ryan et al. (Citation2019) delineate between ‘providing support’ and ‘feeling supported’ whereby the young people in their study did not seek to take-up re-engagement opportunities provided for them if they did not perceive themselves to be supported. Young people in our study frequently attributed the success of the intervention to the fact that the educator ‘proper gets me’ and ‘didn’t give up on me,’ foregrounding their feeling of being supported as of central importance. This finding may be elucidated through the work of Nell Nodding (2003) who argued that caregiving and relationship building must be seen both as an educational goal and as a fundamental aspect of education. If support is offered in the absence of a caring relationship, it may not lead to the trust required for the resources offered by the intervention to be mobilized.

Facilitating mechanisms: self-confidence and self esteem

Once the two foundation mechanisms were established, educators believed that this led on to increased self-confidence and self-esteem in the young person. This may be explained by findings highlighting how positive relationships with educators can raise students’ self-concept, as they believe they are valued by others (Colarossi & Eccles, Citation2003; LaRusso, Romer, & Selman, Citation2008; Wang et al., 2013 in Krane et al. Citation2017) We identify mechanism three as a facilitating mechanism (see, ) because it leads from foundation needs to outcome generating mechanisms. This finding draws on the work of Nouwen and Clycq (Citation2019) who explored the impact of teacher support on student engagement for those at risk of becoming NEET. Key to their findings was the interrelationship between cognitive, emotional and behavioural factors, for example, self-esteem (cognitive) is both shaped by met emotional needs (i.e. addressing wellbeing concerns) and leads on to increased school engagement and higher educational achievements (behavioural outcomes). Further evidence in support of the inter-relationship between wellbeing needs, self-confidence, and social outcomes is provided by the study by Sabato et al. (Citation2021) who found that adolescents with fewer social connections were less likely to help a lonely peer, in lacking confidence both in their own skills and reciprocity.

Outcome generating mechanisms: autonomy in learning and sense of belonging

Mechanisms four and five are ‘outcome generating’ as educators saw these to be higher-level mechanisms, which lead more directly to pro-education and work-related attitudes and behaviours. The importance of a secure sense of self-esteem and confidence in generating a strengthened sense of agency over learning and achievement may be explained through the role of hope as a by-product of a more positive worldview generated when young people feel good about themselves (Simões et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, Santos et al.’s (Citation2020) work has demonstrated how a sense of ownership over educational and work pathways is contingent upon educators personalizing options to young people’s circumstances. There is good reason to think, therefore, that a sense of agency is increased when young people believe that positive but realistic education goals are a possibility for them. Self-esteem and agency over learning may also be self-reinforcing mechanisms; such are the implications of Pruano et al.’s (Citation2022) finding that agency over learning leads to motivation, which reinforced young people’s sense of self-confidence in achieving work or education goals.

The final component to the pathway to change, building a positive learner identity, was seen to be pivotal in generating work and education goals, in cementing young people’s belief in their work aspirations through facilitating the capacity to see themselves as valued learners within the education and work settings they aspire to. This claim is strongly supported in research that has identified that the probability of re-engagement after drop-out is contingent upon generating a sense of ‘fitting in’ and ‘belonging’ (Boylan & Renzulli, Citation2014). It is this sense of identity development which has been pinpointed as an important mechanism for stimulating educational engagement, in explaining how perceived educator support can lead to a fundamental shift in the way the young person sees themselves in relation to their peers (Ryan et al., Citation2019). This involves the reframing of support interventions as ‘a series of social interactions that generate interpretations and meaning by which [social actors] develop a new understanding of their social reality and identity’ (Ng and Sorensen 2008, 247 in Ryan et al., Citation2019). This conceptual shift is significant because as opposed to the young person believing they need to change themselves to fit the learning setting (one of the most common reasons for disengagement) they instead believe themselves to be worthwhile learners in their own right, whereby their educational setting has adapted to fit them.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have argued for the importance of a concerted and holistic approach to understanding and tackling the risks to NEEThood. In reviewing the effectiveness of intervention strategies carried out within 11 settings in the South West of England, we consulted with 28 educators and with 82 young people in order to understand what factors were seen to be the most important in enabling young people to re/engage with education and training. Our findings highlighted the multiplicity of needs affecting young people and the diversity in responses identified as effective. Following Haig (1987), we sought to excavate the underpinning mechanisms by which diverse strategies were seen to be effective, as well as to further understand how such mechanisms may interconnect in leading to a pathway to change. In building upon other literature that sought to theorize a strategic response to addressing NEEThood, we have identified five mechanisms that fulfil foundational, facilitating and outcome generating functions in orientating young people towards the educational and work trajectories that they aspired to.

There are a number of further implications from this study that can guide future policy and practice. Firstly, and in deference to ‘the short-termism of much existing provision’ (Centre for Social Justice Citationn.d.), we argue that support needs to start early, be sustained and personalized due to the complexity of issues facing those at risk of NEEThood (see NFER Citation2012). While the issue of NEEThood is complex and multifaceted, many of the strategies found to be effective involved multiple small or subtle adjustments that cumulatively could be seen to lead to re-engagement or development of motivation to allow educational and work goals to be addressed. Secondly, the findings point to the critical difference for young people in securing the advocacy and support of an individual adult who can unpick complexities around the barriers to engagement and learning. Above all this could be attributed to educators giving the time and attention to develop trusting relationships with the young people. Thirdly, it is essential to consider that the effectiveness of interventions was in part due to the small caseloads involving regular and ongoing one-to-one and small group support, much of which was carried out in a setting that operated alongside or outside of formal education and work settings.

These findings apply to a diverse set of cohorts and settings within two largely rural and geographically proximal regions in South West England. It is important to note, however, that some aspects of the Pathways to Change presented further challenges for educators supporting particular cohorts, particularly those deviating from the largely homogenous White British demographic profile of the region. For instance, in addressing the foundational mechanism of ensuring young people feel cared for and supported, educators supporting asylum-seeking and Gypsy, Roma and Travelling young people needed to make comparatively greater efforts in terms of linguistic and cultural understanding. Further contextual factors conferred to the rural context of the study, for example, much of educators’ effort in addressing welfare involved transport issues. An urban setting in contrast may present very different welfare responses. Consideration should also be given to the temporal context, with the intervention and evaluation phase of this study taking place during the COVID-19 pandemic, it may be that the foundational mechanisms, supporting emotional wellbeing, welfare and feeling cared for supported, took on greater prominence and weight due to the isolation and disruption resulting from lockdowns and school closures. Further research is therefore needed to explore whether different contexts and cohorts require adjustments or alternative responses to the mechanisms identified within the proposed model.

It is our hope that the implications of these findings may inform the development of an educator position such as the ‘case worker’ role (Centre for Social Justice Citationn.d.) that can play an auxiliary but fundamental role within or alongside formal education settings such as school, where many of the challenges young people face are experienced. While the focus of this paper has been to develop a pathway to change to inform educators working with young people, it would be remiss to overlook the broader structural context which both shapes and enables intervention work. Many of the educators involved in this study contended with highly precarious working conditions, blighted by short-term funding and low-paid contracts. We therefore argue that these findings call for a sustained political will and resourcing and a shift to a co-ordinated and long-term NEET policy agenda that would ensure the resources and conditions by which educators can continue and expand their vital work with young people.

D.isclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ceri Brown

Ceri Brown is an Associate Professor in the Department of Education at the University of Bath, UK. She is interested in the impacts of education policy on children’s schooling experiences particularly for those who experience educational binds such as living on a low income, irregular school transitions, mental health challenges, and those at risk of early school leaving.

Alison Douthwaite

Alison Douthwaite is a Research Associate in the Department of Education at the University of Bath with an interest in inclusive and multimodal pedagogy.

Nicola Savvides

Nicola Savvides is Associate Professor in the Department of Education at the University of Bath, UK. Her research lies within the field of Comparative and International Education, including how national, European and international education policies, curricula and pedagogical practices impact on students’ learning experiences, identities and sense of citizenship. Nicola is an Ordinary Member of the British Association for International and Comparative Education (BAICE) Executive Committee (second term) and was former Convenor of the British Educational Research Association’s (BERA’s) Comparative and International Education SIG for 10 years (2010-2020). She holds an ESRC-funded doctorate in Comparative and International Education from the University of Oxford.

Ioannis Costas Batlle

Ioannis Costas Batlle is a Lecturer in the Department of Education at the University of Bath. He is interested in the role of non-formal and informal education in young people’s lives, primarily focusing on charities, youth groups, youth sport, and young people not in education, employment or training. As a qualitative researcher who comes from an interdisciplinary background, Ioannis’s research draws on critical pedagogy, sociology and psychology.

Notes

1. See project website: www.orienta4yel.eu

2. Data from Nomis [Jan–Dec 2020]

3. Short video introducing these 5 mechanisms available at: https://vimeo.com/734272477

References

- Alexander, K., Entwisle, D., & Kabbani, N. (2001). The dropout process in life course perspective: Early risk factors at home and school. Teachers College Record, 103(5), 760–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00134

- Antoni, J. (2021). Disengaged and nearing departure: Students at risk for dropping out in the age of Covid-19. Planning and Changing, 50(4), 117–137.

- Banks, J., & Smyth, E. (2021). “We respect them, and they respect us”: The value of interpersonal relationships in enhancing student engagement. Education Sciences, 11(10), 634–635. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100634

- Bawyer, G., Grant, A., Neilsen, A., Dilworth, N., & White, D. (2021). Closing the digital divide for good: An end to the digital exclusión of children and young people in the UK. Carnegie UK Trust. https://www.carnegieuktrust.org.uk/publications/closing-the-digital-divide/

- Blainey, K., & Hannay, T. (2021). The impact of school closures on spring 2021 attainment. RS Assessment. https://www.risingstars-uk.com/whitepaper21

- Bonal, X., & González, S. (2020). The impact of lockdown on the learning gap: Family and school divisions in times of crisis. International Review of Education, 66(5–6), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09860-z

- Boylan, R., & Renzulli, L. (2014). Routes and reasons out, paths back: The influence of push and pull reasons for leaving school on students’ school reengagement. Youth & Society, 49(1), 46–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X14522078

- Brown, C. (2014). Educational binds of poverty: The lives of school children. Routledge.

- Brown, C., Costas-Batlle, I., Diaz-Vicario, A., & Moreno, J. (2021). Comparing early leaving across Spain and England: Variation and commonality across two nations of high and low relative early leaving rates. Journal of Education and Work, 34(7–8), 740–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.1983526

- Brown, C., Douthwaite, A., Savvides, N., & Costas Batlle, I. (2022). A multi-stakeholder analysis of the risks to early school leaving: Comparing young peoples’ and educators’ perspectives on five categories of risk. Journal of Youth Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.21321392

- Brown C, Rueda P Olmos, Batlle I Costas and Sallán J Gairín. (2021). Introduction to the special issue: a conceptual framework for researching the risks to early leaving. Journal of Education and Work, 34(7–8), 723–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.2003007

- Casillas, A., Robbins, S., Allen, J., Kuo, Y.-L., Hanson, M. A., & Scheiser, C. (2012). Predicting early academic failure in high school from prior academic achievement, psychosocial characteristics, and behaviour. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027180

- Cedefop., (2020) Digital gap during Covid-19 for VET learners at risk in Europe. Synthesis report on seven countries based on preliminary information provided by Cedefop’s Network of Ambassadors tackling early leaving from VET. Digital gap during COVID-19 for VET learners at risk in Europe | CEDEFOP (europa.eu)

- The Centre for Social Justice. (n.d.). Kids can’t catch up if they don’t show up. Driving school attendance through the National Tutoring Programme. https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/library/kids-cant-catch-up-if-they-dont-show-up. Accessed on 21 June 2022

- Colarossi, L.G., & Eccles, J.S. (2003). Differential effects of support providers on adolescents' mental health. Social Work Reserach, 27,19–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/27.1.196

- Department for Education. (2022) SEND Review: Right support, right place, right time: Government consultation on the SEND and alternative provision system in England. SEND Review - right support, right place, right time (publishing.service.gov.uk) Accessed on 12 September 2022

- Department for Education. (2017) Alternative Provision: Effective Practice and Post 16 Transition. Alternative Provision: Effective Practice and Post 16 Transition (publishing.service.gov.uk) Accessed on 12 September 2022

- Department for Education. (2018). Characteristics of young people who are long-term NEET. Characteristics of young people who are long-term NEET (publishing.service.gov.uk) Accessed on 12 September 2022

- Department for Education. (2021a, September 8) Guidance: Academic Mentors. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/academic-mentors Accessed on 21 June 2021a

- Department for Education. (2021b, September 6) Recovery premium funding: Additional funding in the 2021 to 2022 academic year to support schools with education recovery following Covid-19. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/recovery-premium-funding. Accessed on 21 June 2021b

- Education Endowment Foundation. (2020, June). Impact of school closures on the attainment gap: rapid evidence assessment. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/EEF_(2020)_-_Impact_of_School_Closures_on_the_Attainment_Gap.pdf Accessed on 21 June 2022

- Eurostat. (2020). Early leavers from education and training: Luxembourg: Statistical Office of the European Union. Statistics explained. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Early_leavers_from_education_and_training Accessed on 12 September 2022

- Fazackerly, A. (2022, February 13). ‘I’ve got one word for the tutoring programme – Disastrous’: England’s catch-up scheme mired in problems. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/feb/13/ive-got-one-word-for-the-tutoring-programme-disastrous#

- González-Rodríguez, D., Vieira, M. J., & Vidal, J. (2019). Factors that influence early school leaving: A comprehensive model. Educational Research, 61(2), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1596034

- Goulden, C. (2021, May 27) Youth Futures Foundation. https://youthfuturesfoundation.org/news/neet-stats-mask-long-term-problems/

- Hagell, A. (2021). Summarising what we know so far about the impact of Covid-19 on young people. Association for Young People’s Health.

- Hamilton, P., & Morgan, G. (2018). An exploration of the factors that lead to the successful progression of students in alternative provision. Educational & Child Psychology, 35(1), 80–95.

- Haugan, J. A., Frostad, P., & Mjaavatn, P. (2019). A longitudinal study of factors predicting students’ intentions to leave upper secondary school in Norway. Social Psychology of Education, 22(5), 1259–1279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09527-0

- Hodgson, D. (2007). Towards a more telling way of understanding early school leaving. Issues in Educational Research, 17(1), 40–61.

- Hoy, A.W., & Weinstein, C.S. (2006). Student and teacher perspectives on classroom management. In C.M.Evertson & C.S.Weinstein (Eds) Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice and contemporary issues, (pp.181–222). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates./

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10/1177/1049732305276687

- Krane, V., Ness, O., Holter-Sorensen, N., Karlsson, B., & Binder, P. (2017). ‘You notice that there is something positive about going to school’: How teachers’ kindness can promote positive teacher-student relationships in upper-secondary school. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(5), 377–389.

- Lally, C., & Bermingham, R. (2020,) Covid-19 and the disadvantage gap (Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology). https://post.parliament.uk/covid-19-and-the-disadvantage-gap/

- Lamb, S., Markussen, E., Teese, R., Polesel, J., & Sandberg, N. (2010). School Dropout and Completion: International Comparative Studies in Theory and Policy. Springer.

- LaRusso, M.D., Romer, D, & Selman, R.L. (2008) Teachers as builders of respectful school climates: Implications for adolescent drug use norms and depressive symptoms in high school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-0007-92`2-4

- Lörinc, M., Ryan, L., D’Angelo, A., & Kaye, N. (2020). De-individualising the ‘NEET problem’: An ecological systems analysis. European Educational Research Journal, 19(5), 412–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904119880402

- Maguire, S. (2021). Early leaving and the NEET agenda across the UK. Journal of Education and Work, 34(7–8), 7–8, 826–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.1983525

- Maldonado, J., & De Witte, K. (2020). The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes. British Educational Research Journal, 48(1), 49–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3754

- Mason, C. (2022, January 25). 5 Problems with the NTP, according to school leaders. Times Educational Supplement Magazine. https://www.tes.com/magazine/news/general/5-problems-ntp-according-school-leaders

- McDaid, L., Cleary, A., Robinson, M., Johnstone, M., Curry, M. R., T., & Western, M. (2021) What can be done to maximise educational outcomes for children and young people experiencing disadvantage? (Pillar Report No.3) Institute for Social Science Research, University of Queensland.

- Montero-Sieburth, M., & Turcatti, D. (2022). Preventing disengagement leading to early school leaving: Pro-active practices for schools, teachers and families. Intercultural Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2021.2018404

- Nelson, J., & O’Donnel, L. (2012). Approaches to supporting young people not in education, employment or training: A review (NFER Research Programme: From Education to Employment) Slough: NFER.

- Nieuwenhuis, F. J. (2015). Martini qualitative research: Shaken not stirred. Bulgarian Comparative Education Society.

- Nomisweb.co.uk. (2021) Labour Market Profile – Nomis – Official Labour Market Statistics.[online] https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/reports/lmp/la/1946157357/report.aspx#tabempunemp [Accessed 5 March 2022]

- Nouwen, W., & Clycq, N. (2019). The role of social support in fostering school engagement in urban schools characterised by high risk of early leaving from education and training. Social Psychology of Education, 22(5), 1215–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-99521-6

- OECD. (2020, November 19) The impact of Covid-19 on student equity and inclusion: Supporting vulnerable students during school closures and school re-openings. https://doi.org/10.1787/5b0fd8cd-en

- Office for National Statistics. (2022, May 26) Young people not in education or training (NEET). https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/datasets/youngpeoplenotineducationemploymentortrainingneettable1

- Olmos, P., & Guerin, J. (2021). Understanding and intervening in the personal challenges and social relationships risk category to early leaving. Journal of Education and Work, 34(7–8), 855–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.1997016

- Ose, S., & Jensen, C. (2017). Youth outside the labour force – Perceived barriers by service providers and service users: A mixed method approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 148–156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.002

- Powell, A. (2021, July 7) NEET: Young people not in education employment of training. House of Commons Library. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06705/SN06705.pdf

- Pruano, A., Entrena, M., Soto, A., & Cano, J. (2022). Why vulnerable early school leavers return to and re-engage with education: Push and pull reasons underlying their decision. Intercultural Education https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2021.2018209

- Psifidou, I., Mouratoglou, N., Farazouli, A., & Harrison, C. (2022) Minimising Early Levin from Vocational Education and Training in Europe: Career guidance and counselling as auxiliary levers. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Cedefop working paper, No 11. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/75320

- Reimers, F., Amaechi, U., Banerji, A., & Wang, M. (2022). Education to Build Back Better: What Can We Learn from Education Reform for a Post-pandemic World. Springer.

- Remiers, F. (Ed.). (2022). Primary and secondary education during Covid-19:Disruptions to educational opportunity during a pandemic. Springer.

- Ryan, L., D’Angelo, A., Kaye, N., & Lorinc, M. (2019). Young people, school engagement and perceptions of support: A mixed methods analysis. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(9), 1272–1288. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1571178

- Sabato, H., Abraham, Y., & Kogut, T. (2021). Too lonely to help: Early adolescents’ social connections and willingness to help during Covid-19 lockdown. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 764–779. https://doi.org/10.111/jora.12655

- Santos, S., Nada, C., Macedo, E., & Araujo, H. (2020). What do young adults’ educational experiences tell us about Early School Leaving processes? European Educational Research Journal, 19(5), 463–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904120946885

- Simões, F., Marta, E., Marzana, Alfieri, S., Pozzi, M., & Marzana, D. (2021). An Analysis of Social Relationships’ Quality Associations with Hope Among Young Italians: The Role of NEET Status. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 4(2), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-021-00034-8

- Soggiu, A. L., Klevan, T., Davidson, L., & Karlsson, B. (2019). School’s out with fever: Service provider perspectives of youth with mental health struggles. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 343–354.

- Studsrød, I., & Bru, E. (2011). Perceptions of peers as socialization agents and adjustments in upper secondary school. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 16, 159–172. http://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/handle/11250/184980

- Whitehead, J., Schonert-Reichl, K., Oberle, E., & Boyd, L. (2022). What do teachers do to show they care? Learning from the voices of early adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 074355842210760. https://doi.org/10.1177/07435584221076055

- Williams, J., Alexander, K., Wilson, T., Newton, B., McNeil, C., & Jung, C. (2021, October 20). A Better Future: Transforming jobs and skills for young people post-pandemic. Institute for Employment Studies, Report 568, https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/resource/better-future-transforming-jobs-and-skills-young-people-post-pandemic

- Yeoman, E. (2022, February 21). National Tutoring Programme ‘risks failing pupils who need it most,’ says Lee Elliot Major. The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/national-tutoring-programme-risks-failing-pupils-who-need-it-most-says-lee-elliot-major-lcs3933cc