?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The psychological resilience and coping strategies among university students in Ethiopia have not been researched. This study aims to examine it among undergraduate students at Wallaga University, among 398 students. Data was collected using Resilience Resource Scale (RRS) and Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS). The total score on RRS ranges from 16 to 60, with a mean score of 49.12 (SD 7.06), and CISS score ranges from 41 to 105, with a mean score of 76.62 (SD 11.22). Rural resident (β = −2.042; 95% CI; −3.395 to −0.688), first-year (β = −7.0.32; 95% CI; −10.918 to – 3.145), second-year (β = −3.082; 95% CI; −4.971 to – 1.193), task-oriented (β = 1.046, 95 CI; 0.455–1.636), emotion-oriented (β = 1.936; 95% CI: 1.335–2.537) and avoidance (β = 2.881; 95% CI: 2.286–3.477) were contributing factors. Junior and rural students deserved attention on their coping strategies and psychological resilience.

Introduction

Entry into higher education and even just studying in higher education itself can have a range of effects on young adults’ psychological outlooks, which can result in stressful situations and psychological suffering (Bracaglia, Citation2017; Wu et al., Citation2020).

University students face numerous challenges in addition to academic expectations, such as identity development, financial pressures, emotions, new housing, construction of new social networks, and adaptability to new social roles (Gomez et al., Citation2018; Pidgeon, et al.,2017). It is crucial to understand how young individuals navigate this stage while overcoming difficulties (Anasuri et al., Citation2018). Academic performance, as well as a variety of other social and psychological variables, are all significantly influenced by how the students handle these stressful situations (Anasuri et al., Citation2018).

When people leave their familiar network behind and enter an unfamiliar environment, transitions can be stressful. In addition, the academic pressure that university students experience may be detrimental to their mental health (Cooper & Quick, Citation2017; Wu et al., Citation2020). According to literature, psychological suffering rises when university students transition from their first to second year (Gomez et al., Citation2018). Resilience is one factor that research has proven to buffer this adversity (Robbins et al., Citation2018).

Resilience is defined for university students as the ability to recover or bounce back from adversity, conflict, and failure, or even positive occurrences, growth, and more responsibility, despite the lack of a single definition being provided. It explains why some students recover and advance while others give up after encountering difficulties and stressful situations during their studies (Backmann et al., Citation2019; Gomez et al., Citation2018). The educational experience of identifying and developing resilience allows students to reflect on who they are and how their body, mind, and spirit work in relation to transpersonal sources of strength, according to Richardson’s (Citation2002) metatheory of resilience. Being childlike, moral, intuitive, and noble is a simple yet powerful way to experience resilience as a driving force (Richardson, Citation2002).

Coping is thoughts and behaviours that people use to manage the internal and external demands of situations that are appraised as stressful. There is no gold standard for the measurement of coping. The measurement of coping is probably as much art as it is science. The art comes in selecting the approach that is most appropriate and useful to the researcher’s question. Sometimes, the best solution may involve several approaches (Folkman & Moskowitz, Citation2004).

Coping strategies refer to the cognitive and behavioural changes that result from the management of an individual’s specific external/internal stressors (Chen, Citation2016; Wu et al., Citation2020). Researchers have proposed three distinct types of coping strategies: problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping and avoidance coping (Chen, Citation2016; Folkman & Moskowitz, Citation2004; Wu et al., Citation2020). Problem-focused coping is a task-oriented coping strategy that attempts to alter stressful situations with active efforts to solve the problem or reduce its negative impact. Emotion-focused coping aims to diminish stressful events through emotional responses such as self-blaming, anger or self-preoccupation. Avoidance coping involves attempts to avoid stressful situations via social distraction or escape from the situation rather than actively facing and dealing with it. Psychological problems are affected by coping methods.

Although they are related concepts, coping and resilience have differing effects on behavioural changes. Resilience refers to the capacity to adapt to challenging situations in the face of adversity, whereas coping refers to cognitive and behavioural techniques to cope and manage stressful events or negative psychological and physical repercussions (Wu et al., Citation2020). There have been studies on resilience and coping mechanisms among university students in nations other than Ethiopia (Bracaglia, Citation2017; Wu et al., Citation2020). The research’ results showed that psychological distress among undergraduate students decreased as psychological well-being increased.

According to the theory of stress and coping coined by Lazarus (Citation1966) and its revisions in 1991, stress is a relational concept, the transition or relationship between the individuals and their environment. This concept pinpointed two processes as central mediators between individuals (students in this study) and their environments (campus life in this study): cognitive appraisal and coping (Cooper & Quick, Citation2017). The concept of appraisal claims that emotional processes (including stress) depends on actual expectancies that persons manifest with regard to the significance and outcome of a specific encounter. This concept is necessary to explain individual differences in quality, intensity, and duration of an elicited emotion in environments that are objectively equal for different individuals. A number of personal and situational factors can influence this concept.

The latter concept (coping) is frequently characterized by the coinciding occurrence of different action sequences and, hence, an interconnection of coping episodes. Coping actions can be distinguished by their focus on different elements of a stressful encounter (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984). They can attempt to change the person–environment realities behind negative emotions or stress (problem-focused coping). They can also relate to internal elements and try to reduce a negative emotional state, or change the appraisal of the demanding situation (emotion-focused coping). When a situation is appraised as a stressful (primary appraisal), and requiring efforts to manage or resolve the event (secondary appraisal), coping action is indorsed. Based on the results of coping efforts, positive coping results in successful adaptation and the individual is able to be resilient, or the negative result (unsuccessful adaptation) initiate further coping strategies, with continued failure resulting in negative affect and psychological disturbance (Cooper & Quick, Citation2017; Edwards, Citation1992).

The ability of the student to manage their college experience is the top concern for higher education institutions, according to evidence (Bryon C. Pickens et al., Citation2019). For example, more than two in five college students experienced at least one mental health issue that was related to their academic performance, but more than 90% of them did not seek out on-campus support. In contrast to other age groups, college-age students employed avoidance and unhealthy coping mechanisms to deal with daily challenges. However, it appears that women are more prone than males to utilize approach methods, particularly those that are emotion-focused, when they are in college (Blanchard-Fields et al., Citation1991). The degree of resilience kids possess determines how well they can adjust and handle pressures in college and university (U & Ali, Citation2018). By directly influencing the secondary appraisal and the maladaptive stress outcome, psychological resilience plays an adaptive function in the stress process (Sivam & Chang, Citation2016). It helps pupils cope better with the demands of academic strain and lessens their psychological suffering.

Studies targeting general population resilience on conditions like illnesses, disabilities, trauma, and other behavioural issues were undertaken in Ethiopia (Birhanu et al., Citation2017; Julian et al., Citation2020; De la Fuente et al., Citation2021; Sewasew, Citation2014). Street children, university teachers, and others were also studied (BN Worku et al., Citation2019; DU Gita et al., Citation2019). (Crivello G, Citation2021; Zewude & Hercz, Citation2021). However, there is no evidence in regards to the university students. The available research revealed that university students had a greater attrition rate and dropout rate due to their inability to adapt to their new environment after beginning their studies, with female students being more susceptible to the threat than male students (Sewasew, Citation2014; Wezira Ali, Citation2019). The move to college and the first semester of college life also left students, especially female students, feeling anxious, terrified, puzzled, and disoriented (, Thuo, M, Citation2017; Birhanu et al., Citation2017). The absence of empirical studies demonstrating the psychological resilience and coping mechanisms among university students in Ethiopia runs counter to these indications. In light of this, the following hypotheses were raised in this study.

Hypothesis 1: Undergraduate students in Wallaga University have low level of psychological resilience

Hypothesis 2: Undergraduate students in Wallaga University have low level of coping strategies

Hypothesis 3: Gender, residence, year of study and field of study affects the level of psychological resilience and coping strategies among undergraduate students.

Hypothesis 4: Psychological resilience among undergraduate students in Wallaga University is affected by some variables like gender, residence, year of study and field of study.

To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, there are no publicly available studies addressing the psychological resilience and coping strategies used by undergraduate students at Wallaga University and throughout Ethiopia in general. The current study’s goal is to better understand the psychological resilience, coping strategy, and associated factors among undergraduate students at Wallaga University in Ethiopia. In this regard, the study made an effort to offer responses to the following four questions.

1. What is the level of psychological resilience of undergraduate students in Wallaga University?

2. What is the level of coping strategies of undergraduate students in Wallaga University?

3. Are the levels of psychological resilience and coping strategies differing in gender, residence, year of study and field of study?

4. What are the factors contributing to psychological resilience among undergraduate students in Wallaga University?

Methods

Study setting

The study was carried out at the main campus of Wallaga University, which is located 331 kilometres far outside Addis Ababa in the western part of Ethiopia. One of Ethiopia’s public applied universities, Wallaga University was founded in 2007 by the country’s ministry of education. Nekemte, Shambu, and Ghimbi campus are its three campuses. It was providing community services, research, and technology transfer in addition to teaching and learning. During the data collection period, more over 24,000 students were enrolled in regular, weekend, summer, and distance learning programs at all academic levels, from bachelor to PhD. There were 6,369 regular undergraduate students (4065 men and 2004 women) pursuing their education on the Nekemte campus. There were 7 colleges, institutions, and schools, offering 119 undergraduate programs in all.

Study design and period

Institution-based quantitative cross-sectional research design was used from April 01–30, 2022. Because it can best be used to address the study’s purpose and contribute to the generation of the hypothesis, a cross-sectional study was appropriate for this particular investigation.

Participants

The source population of the study was all undergraduate students attending their education at Wallaga University. The study population were all regular undergraduate students attending their education at Wallaga University who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. All the randomly selected regular undergraduate students attending their education during data collection and who fulfilled the eligibility criteria were the sample population of the study. The sampling frame was the list of the study unit which was found from registrar and their respective departments.

Delimitations of the Study

The age range for the undergraduate participants in this study is 18 to 25. Age, sex, place of residence, marital status, amount of pocket money, academic year, and field of study were the variables used in the study. Resilience Recourse Scales (RRS) and Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) scales were both utilized. All undergraduate students from five colleges or institutions who were enrolled in a regular program and were randomly chosen as study participants. According to their proportions, men and women from various departments and a batch from five colleges and institutions were both included. Only students in undergraduate regular programs were included in the research’s generalization of its findings.

Sample size determination

Sample size was determined using single population proportion formula by considering 95% confidence interval, 5% precision and proportion of psychologically resilient students as 50% because similar study is not available in Ethiopia. Accordingly, the following formula was used to estimate the sample size.

where n = estimated sample size

= standard normal variate (at 5%) type 1 error (p < 0.05) corresponding to 0.96

P = Expected proportion of population = 50%;

d = The precision of the estimate

Because the total number of regular undergraduate students in Wallaga university (N = 6369) was less than 10,000, we used a correction formula to adjust the sample size and added 10% non-response rate. Accordingly, 398 students were included in the study.

Sampling procedure

The stratified random sampling method was used. The students were first divided into groups according to their respective streams (natural science and social science stream). They were chosen at random from their respective institutions or faculties using simple random sampling. Again, using a simple random selection procedure, the students’ respective departments and years of study were chosen at random. Additionally, depending on the proportionally assigned amount of research samples in the chosen section, the study unit was chosen using simple random selection. There is a graphical depiction (supplementary file 1).

Recruitment

For the data collection, four research assistants with bachelor’s degrees were engaged. They first asked the instructors to give them a few minutes after their lectures or sessions. Before handing out the questionnaire, the students were fully informed of the reason behind the data collection.

Measurement

Psychological resilience of undergraduate students

Psychological resilience was measured by the Resilience Resource Scale (RRS) containing 12-items having a 5-Likert scale of 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. The constructs represented in the scales’ 12 items are self-esteem (2 items), mastery (2 items), dispositional optimism (2 items), familism (1 item), spirituality and religiosity (2 items), purpose in life (1 item), and social support seeking skills (2 items). The total score was calculated by summing the item scores, with a possible range from 12 to 60. Higher scores reflected greater resilience (Julian et al., Citation2020).

Measuring coping strategies of undergraduate university students

Coping strategies was measured by the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations: short-form CISS-21 which is categorized under three theoretical infrastructures namely task-oriented coping, emotion-oriented coping and avoidance (Boysan, Citation2012; Richard S. Lazarus, Citation1984). Each item has a five-scale Likert type question with 3 sub-scales consisting of 7 items each. The scale was measured on 5-point Likert scale, with possible range from 21 to 105. In this study, CISS above mean indicate those who positively cope with their situation. The instruments used is attached as supplementary file 2.

Reliability of the instruments

The reliability of the instruments was checked by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Accordingly, the RRS and CISS showed acceptable internal consistency reliability: 0.798 for RRS and 0.813 for the CISS. The Cronbach alpha for task-oriented coping, emotion-oriented coping and avoidance coping was 0.835, 0.835 and 0.839, respectively.

Validity of the instruments

The instruments were validated before the actual data collection. The face validity was reviewed by the two subject matter experts from department of psychology. They were selected based on their subject area expertise and their experiences on the area. The order and appearance of the questionnaires were amended based on the experts’ feedback.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data was checked for its completeness, and coded manually. Data entry was done by Epi-data software version 3.1 and exported to statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 26 for cleaning and analysis. Mean scores of the psychological resilience and coping strategy scales were calculated, summarized and presented in tables along with the demographic characteristics of the students. Three components of CISS were generated by principal component analysis (PCA). Eigen value of greater than 1.6 was considered on fixing the extracted factors to three (see supplementary file 3).

For analysis purpose, dummy variables (for k categories, k-1 dummy variables) were created for categorical variables which had more than two categories (Alkharusi, Citation2012; in this study, residence and year of study). Rural was taken as reference variable and coded as (1 = rural,0 = non-rural; 1 = urban, 0 = non-urban and 1 = semi-urban, 0 = non-semi urban). For the year of study, fifth year was taken as reference variable and coded as (1 = first year, 0 = others; 1 = second year, 0 = others; 1 = third year, 0 = others; 1 = fourth year, 0 = others and 1 = fifth year, 0 = others).

Descriptive statistics was used to display the sociodemographic variables of the undergraduate students using frequency and percentage and explained using texts, graphs and charts for categorical variables. Mean and standard deviation was used to present self-reported resilience and coping strategy scores by the socio-demographic variables. The reliability of resilience resource scales and Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations: short-form CISS-21 was checked for its internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. To compare differences in resilience and coping between groups by the students’ socio-demography, independent sample t-test and one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used. For those variables having more than two groups, post hoc test using Tukey HSD test was checked to detect the difference across the groups.

Assumptions were checked including the presence of multi collinearity, homoscedasticity and linearity, all acceptable and showing the model was fit. Unstandardized beta (β-coefficient) was used to interpret the strength of predictors of psychological resilience. The degree of association between pairs of the variables was measured by Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). In the multiple linear regression analysis psychological resilience was considered as an outcome variable and the others factors were treated as predictor variables with P < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

The analysis included 381 study participants in total, with a response rate of 95.73%. The study participants’ average age was 21.87, with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.62 years. Male participants made almost nearly twice as many participants (66.1%) as female participants. The study included students from five colleges/institutions’ first-year 11 (2.9%) through fifth-year 64 (16.8%) batches, with a ratio of 1:2.5 between the social science and natural scientific streams. About half (49.6%), 138 (36.2%), and 54 (14.2%) of the students’ previous residences were rural, urban, and semi-urban, respectively. The majority of research participants (91.1%) were single. The details were shown in .

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristic of Undergraduate Wallaga University students, 2022.

Psychological resilience and coping strategies of the study participants

shows the difference in the mean score of psychological difference and positive coping strategies among subgroups of the students by their gender, residence, field of study and year of study. The total score on the Resilience Resource Scale ranged from 16 to 60 with the mean score of 49.12 (95% CI: 48.41–49.83), (SD ± 7.06) and the total score on the Coping Inventory for Successful Situations (CISS) ranged from 41 to 105 with the mean score of 76.62 (95% CI: 75.44–77.81), (SD ± 11.22).

Table 2. Mean scores of Resilience Resource Scale and Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations by the undergraduate students’ characteristics.

No significant difference in the resilience level between male and female students (P = 0.061) were observed, but in the coping scales (p = 0.047). Social science students scored significantly lower than the natural science stream students on RRS (mean score: 49.48 for natural sciences and 47.46 for social science stream students’ (p = 0.001). There was no significant difference in coping strategies among residence and field of study (p = 0.077 and 0.233, respectively). There is a significant difference in resilience (p = 0.001) and coping (p = 0.001) among 1st, 2nd,3rd, 4th and 5th year students. As their year of study increases, their resilience and coping strategies also increased.

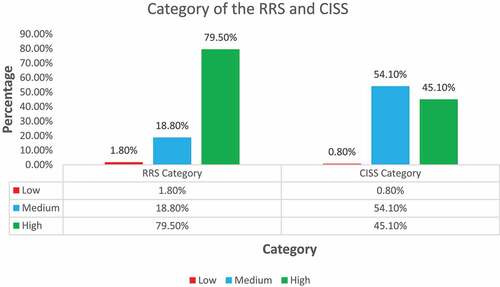

Only seven (1.8%) and 3(0.8%) students scored lower, 71 (18.6%) and 206 (54.1%) scored medium and 303 (79.5%) and 172 (45.1%) scored higher in RRS and CISS, respectively. More than half (55.1%) of the students were resilient and 192 (50.4%) had good coping strategy in the stressful situations. Explained in .

Correlation between the psychological resilience, coping strategies and the students’ demographic characteristics

The correlations between the psychological resilience of the students and other factors were presented in . The correlation analysis showed that, there is a highly significant positive association between the students’ psychological resilience and the total coping strategies, the three positive coping components and their demographic characteristics including age, residence, field of study and year of study.

Table 3. Correlation between psychological resilience of the students and other factors.

There is no significant correlation between sex and the coping strategies and the three components of the coping of the students. Task-oriented coping had no association with the students’ demographic characteristics, while total coping score was poorly associated with field of study and strongly associated with year of study of the students.

Multiple linear regression analysis of psychological resilience, coping strategies, and demographic characteristics of the students

Overall, the model showed significant association between the independent variables and psychological resilience (R squared = 0.379, F = 17.231, P < 0.05). A higher level of resilience was related to higher coping strategy scores and its components.

Multivariate linear regression analysis showed that, there is a statistically significant positive correlation between the psychological resilience of the students and their previous residence and the three components of coping (task-oriented coping, emotion-oriented coping and avoidance coping) while significant negative association with the year of the study (first and second year).

In this study, students whose residence was rural were about two units less psychologically resilient when compared to those who came from urban areas (β = −2.042, 95% CI, −3.39 to −0.68; p = 0.003).

As the students’ year of study (seniority) increased, their psychological resilience level improved. For instance, first year students and second year students had about seven units and three units less psychologically resilient when compared to the fifth year students (β = −7.032, 95% CI, −10.918to −3.145, p < 0.001 and β = −3.082, 95% CI, −4.971 to −1.193, p = 0.001), respectively.

The three coping components were positively correlated with the psychological resilience of the undergraduate students. Psychological resilience of the students increases by 1.046, 1.936 and 2.881 units in a unit increase in task-oriented coping (β = 1.046, 95% CI, 0.455–1.636, P = 0.001), emotion-oriented coping (β = 1.936, 95% CI,1.335–2.537, P < 0.001) and avoidance coping (β = 2.881, 95% CI, 2.286–3.477, p < 0.001), respectively.

Age, sex, field of study and pocket money were not statistically significant with the psychological resilience of the undergraduate students. illustrates the multivariate linear regression analysis findings.

Table 4. Multivariate linear regression analysis result for the association between psychological resilience, demographic characteristics and coping strategy among undergraduate students in Wallaga University, 2022.

Discussion

In the current study, a sample of undergraduate students at Wallaga University were analysed to determine the association between psychological resilience, demographic characteristics, and coping strategies. The relationship has not before been documented in Ethiopia, and it also provides evidence for a possible linear relationship between psychological resilience, coping mechanisms, and other characteristics of university students.

The present study indicated that undergraduate students scored moderate level psychological resilience (49.12 ± 7.06) and substantial level of coping strategies (76.62 ± 11.22) in stressful conditions in their campus life. The finding was substantially lower than the findings reported from China (70.41% for resilience; Wu et al., Citation2020), university of Free State (84.6% for resilience; Van der Merwe et al., Citation2020), colleges in USA (Anasuri et al., Citation2018), but slight higher than the findings reported from other study in America (43.2%; Julian et al., Citation2020). The possible explanation for the differences could be due to the differences in sample population, the sample size, and the difference in scale of resilience measurement used. For instance, the study from China used Asian Resilience score (ARS) which contained 19 items and that of Free State university used the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale which contains 25 items. The study participants were also limited to single college (health sciences). However, in the present study, different students (all batches) from different colleges were included which might contribute for the lower score of the resilience scale.

Additionally, the Chinese government’s education policy supports and upholds sound mental health college education, offers free psychological counselling services, and mandates and offers elective mental health courses (Wu et al., Citation2020). The higher resilience scores may have resulted from this. Despite a promising policy for inclusion in the educational system, psychological counselling services are neither practical nor comprehensive nor are they included in the courses in Ethiopia, unless for curricular purposes.

The study revealed that undergraduate students with a higher total resilience score experienced more coping strategies. Strong correlations were observed between the students’ psychological resilience and task-oriented, emotion-oriented and avoidance coping. The finding of the study was supported by previous studies in China (Wu et al., Citation2020), Free Syate University (Van der Merwe et al., Citation2020; De la Fuente et al., Citation2021). This is because, resilient students are more likely to be competent, self-controlled, tolerant of negative affect, and tends to accept changes with attitude when compared to non-resilient students. Therefore, when encountering difficulties and adversities, they are more likely to alter the situations and/or take actions to solve the problem (i.e. task-oriented coping strategy), rather than to blame themselves for being too emotional, become tense or daydream (i.e. emotion-oriented coping strategy) and tend to avoid the stressful conditions through social diversion or off-putting themselves with other situations or tasks (Chen, Citation2016).

In this study, junior students (first year and second year) were less psychologically resilient compared to their senior students (third and fourth year). There is an inverse association between the resilience resource scale and first and second year studies and the association was highly significant. Though not statistically significant, the third and fourth year students were also less resilient (marginal) when compared to the fifth year students. This indicates that as the duration of the students in the campus lengthened, their level of psychological resilience also escalates or improved and the reverse also holds true. This is supported by other findings (Van der Merwe et al., Citation2020). This might be due to the improvement of personal development as the students progressed in their studies. Again, the more they stay in campus, the more they adapt to the challenges aroused from academic stress and complex social relationships. However, in one of the university in China, year of study was not statistically associated with the resilience score. This might be due to the supportive guidelines and policy of the education system of the country in which all the students had equal chance to be included in the policy-supported free psychological counselling services and the inclusion of the psychological resilience courses to their education system. According to the interventional study in China, the mental health education has a potential to link the content of education as the purpose and essence of education to help college students improve the health psychological basis and spiritual concepts including the scientific and objective ideological understanding, moral cultivation, ideal and belief (Li et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, there is a statistically significant association between the psychological resilience and the students’ previous residency. In comparison to urban resident students, those who came to the university from rural area were less psychologically resilient. Other study findings supported the evidence. This is because of the fact that rural resident students are less likely to seek positive psychological help seeking attitude and feels higher sense of well-being. On the other hand, the rural residents underutilize or fear to utilize the psychological help seeking due to social norms, stigma and absence of anonymity. According to the findings, transition for rural area to the urban university, per se universally endorsed as stressor and induce perceived cultural gaps (Bitz, Citation2011).

In this study, there was not statistically significant association between psychological resilience and age, sex, pocket money, field of study, among others.

Limitations

When using the findings as the basis for additional research, it is important to keep the limits in mind. First, the study cannot prove a causal link between psychological resilience, effective coping strategies, and other predictors because of the cross-sectional nature of its methodology. To establish the causal link, a prospective longitudinal and experimental study design is required. Second, because the data was drawn from a single university where a disproportionate number of students belonged to the same ethnic group, it is problematic to extrapolate the findings to the remainder of the undergraduate students at other universities across the country. Third, even though good measuring scale reliability and validity were noted, it was not possible to draw the conclusion that the results excluded recall bias because of the self-reported questionnaires.

Despite these drawbacks, the current study contributes to our understanding of the relationship between psychological resilience and coping strategies among Ethiopian undergraduate students.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

Data will be available on the reasonable request from the principal investigator

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (81.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2022.2151370

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bikila Regassa Feyisa

Bikila Regassa Feyisa, MPH, MA, Ph.D. student in Epidemiology at Jimma University, Ethiopia. He is an epidemiologist and developmental psychologist at Wallaga University, Ethiopia. His research focuses on non-communicable diseases and positive psychology.

Adugna Bersissa Merdassa

Adugna Bersissa Merdassa, Ph.D., is a developmental psychologist at Wallaga University, Ethiopia. He is the directorate director of the testing and assessment at the university.

Bayise Biru

Bayise Biru, MSc, Ph.D. student at Jimma University, Ethiopia. She is a nutritionist at Wallaga University. Her research focuses on malnutrition and its effects on the psychological makeup of children and adolescents.

References

- Ali, W. (2019). Assessment on Factors causing female students attrition at haramaya university, Ethiopia. Scientific Research Journal (SCIRJ), 7(11), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.31364/SCIRJ/v7.i11.2019.P1119719

- Alkharusi, H. (2012). Categorical variables in regression analysis: A comparison of dummy and effect coding. International Journal of Education, 4(2), 202–210. https://doi.org/10.5296/ije.v4i2.1962. https://www.macrothink.org/journal/index.php/ije/article/view/1962

- Anasuri, S., Ph, D., & Anthony, K. (2018). Resilience levels among college students : A comparative study from two southern states in the USA. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 23(1), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2301035273

- Backmann, J., Weiss, M., Schippers, M. C., & Hoegl, M. (2019). Personality factors, student resiliency, and the moderating role of achievement values in study progress. Learning and Individual Differences, 72( April 2018), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.04.004

- Birhanu, Z., Ambelu, A., Berhanu, N., Tesfaye, A., & Woldemichael, K. (2017). Understanding resilience dimensions and adaptive strategies to the impact of recurrent droughts in Borana zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia: A grounded theory approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020118

- Bitz, A. L. (2011). Does being rural matter?: The roles of rurality, social support, and social self-efficacy in first-year college student adjustment. In ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280148777

- Blanchard-Fields, F., Sulsky, L., & Robinson-Whelen, S. (1991). Moderating effects of age and context on the relationship between gender, sex role differences, and coping. Sex Roles, 25(11–12), 645–660.

- Boysan, M. (2012). Validity of the coping inventory for stressful situations - Short form (CISS-21) in a non-clinical Turkish sample. Dusunen Adam, 25(2), 101–107. https://dx.doi.org/10.5350/DAJPN2012250201

- Bracaglia. (2017). Psychopathological symptoms and psychological wellbeing in Mexican Undergraduate Students. Physiology & Behavior, 176(3), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v5i6.2287.Psychopathological

- Chen, C. (2016). The Role of Resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among Chinese University Students. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25(3), 377–387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40299-016-0274-5

- Cooper, C. L., & Quick, J. C. (2017). The handbook of stress and health (a guide to research and practice). Lazarus and Folkman’s Psychological Stress and Coping Theory, 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118993811.ch21

- Crivello, G., Tiumelissan, A., Heissler, K. (2021). “The challenges made me stronger”: what contributes to young people’s resilience in Ethiopia?. Issue April.

- de la Fuente, J., Santos, F. H., Garzón-Umerenkova, A., Fadda, S., Solinas, G., & Pignata, S. 2021. Cross-Sectional study of resilience, positivity and coping strategies as predictors of engagement-burnout in undergraduate students: implications for prevention and treatment in mental well-being. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, February, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.596453

- Edwards, J. R. (1992). A cybernetic theory of stress, coping, and well-being in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 238–274. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1992.4279536

- Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 745–774. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456

- Gita, D. U., Disassa, G. A., & Worku, B. W. (2019). Street children’s drug abuse and their psychosocial actualities synchronized with intervention strategies in South West Ethiopia. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 6(5), 682–693. http://dx.doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v6i5.1170

- Gomez, M. R., Zayas, A., Ruiz, G. P., & Guil, R. (2018). Optimism and Resilience Among University Students. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1). https://www.redalyc.org/journal/3498/349855553017/html/

- Julian, M., Cheadle, A. C. D., Knudsen, K. S., Bilder, R. M., & Dunkel Schetter, C. (2020). Resilience Resources Scale: A brief resilience measure validated with undergraduate students. Journal of American College Health, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1802283

- Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological Stress and the Coping Process. McGraw-Hill.

- Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (1st ed.). Springer Publishing Company. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1447857/stress-appraisal-and-coping-pdf

- Li, X., Gao, Y., & Jia, Y. (2021). Positive guidance effect of ideological and political education integrated with mental health education on the negative emotions of college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(January), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/2Ffpsyg.2021.742129

- Pickens, B. C., McKinney, R., & Bell, S. C. (2019). A hierarchical model of coping in the college student population. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 7(2), 1–19. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1267016.pdf

- Resilience in the ecological transactional model. European Scientific Journal 12, (14) 63–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v12n14p63

- Richardson, G. E. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10020

- Robbins, A., Kaye, E., & Catling, J. (2018). Predictors of Student Resilience in Higher Education. Psychology Teaching Review, 24(1), 44–52. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1180345

- Sewasew, D. T. (2014). ATTRITION CAUSES AMONG UNIVERSITY STUDENTS: THE CASE OF GONDAR UNIVERSITY, GONDAR, NORTH WEST ETHIOPIA. Innovare Journal of Social Sciences, 2(2), 27–34. https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijss/article/view/892

- Sivam, R.-W., & Chang, W. C. (2016). Occupational Stress: The Role of Psychological Resilience in the Ecological Transactional Model. European Scientific Journal, ESJ, 12(14), 63. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v12n14p63

- Thuo, M. W. (2017). Transition to university life: insights from high school and university female students in wolaita zone, Ethiopia. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(4), 45–54. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1132933.pdf

- U, H., & Ali, A. 2018 Resilience, psychological distress, and self-esteem among UndergraduateStudents in Kollam District, Kerala A. Paul Ed. Journal of Social Work Education and Practice Vol. III: 4 27–36. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332318986

- Van der Merwe, L. J., Botha, A., & Joubert, G. (2020). Resilience and coping strategies of undergraduate medical students at the university of the free state. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 26, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4102/2Fsajpsychiatry.v26i0.1471

- Worku, B. N., Urgessa, D., & Abeshu, G.; BN Worku, Dinaol Urgessa, Getachew Abeshu. (2019). Psychosocial Conditions and Resilience Status of Street Children in Jimma Town. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 29(2), 361. https://doi.org/10.4314/2Fejhs.v29i3.8

- Wu, Y., Yu, W., Wu, X., Wan, H., Wang, Y., & Lu, G. (2020). Psychological resilience and positive coping styles among Chinese undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00444-y

- Zewude, G. T., & Hercz, M. (2021). Psychological capital and teacher well-being: The mediation role of coping with stress. European Journal of Educational Research, 10(3), 1227–1245. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.10.3.1227