ABSTRACT

This study focused on individuals who classify themselves as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual and any other non-heterosexual orientations (LGBTQIA+) and their general attitude towards HIV testing. The hypothesis for this study is that LGBTQIA+ individuals with lower levels of predictor variables (lower level of outness and peer openness) have significantly different attitudes towards HIV testing than those with higher levels of predictor variables. A three-part survey was passed out via quota sampling method, and 121 participants answered the survey. The result showed that there is a statistical significance between a LGBTQIA+ individual’s level of outness and their attitude towards HIV testing (p < 0.05), which leads to the conclusion that level of outness may be an indicator that predicts a LGBTQIA+ individual’s attitude towards HIV testing. Findings of this study may help understand the relationship between LGBTQIA+ individuals’ psychological barrier factors and attitudes towards HIV testing, which may inform future research and practices.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Individuals identifying themselves as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and plus/+ which stands for any non-heterosexual orientations (LGBTQIA+) have raised several concerns regarding the prejudice and stigma that they face, even though the concepts of non-heterosexual orientations have become much more accepted in more developed and progressive areas. Critically, such prejudices and stigmas have negative impacts on gay and lesbian individuals in terms of their sense of value and confidence (Brown et al., Citation2016). Studies have also found that an oppressive social environment can create negative health outcomes physically and psychologically for LGBTQ youth, especially if these individuals are minorities (Balsam et al., Citation2011; Kelleher, Citation2009). Kelleher (Citation2009) surveyed 301 LGBTQ Irish residents aged 16–24 years through online questionnaire, specifically focusing on three components of minority stress: sexual identity distress, stigma consciousness, and heterosexist experiences. The results suggest a significant association of each stressor and psychological distress of LGBTQ youth living in Ireland (Kelleher, Citation2009). Also, Balsam et al. (Citation2011) conducted a web survey to assess the distress level generated from racial and LGBT stigma (with a Likert scale of 0 being the least distressed and 5 being the most distressed) of 269 individuals who identified themselves as both LGBT and People of Colour (POC). This study found that there is a significant difference between POC individuals who identify themselves as LGBT in terms of their level of distress, and Asian Americans scored significantly higher than other POC individuals, showing that psychological distress does exist in LGBT individuals (Balsam et al., Citation2011).

In addition to the impacts on psychological wellbeing, these stigmas and biases may have severe health consequences. Specifically, stigma may lead LGBTQIA+ individuals to refuse HIV testing. Dowson et al. (Citation2011) suggested that many men who have sex with other men (MSM) in the United Kingdom get HIV testing much later than their last sexually risky activity due to psychological barriers such as fear, perception of low risk of getting HIV and stigma surrounding HIV testing. Kwan et al. (Citation2016) also found that HIV testing rates remain low for MSM, where less than half of respondents (41.7%) have gotten HIV tested. The HIV testing rate for non-heterosexual women, on the other hand, is unclear due to few studies being conducted in such a group.

What is more concerning than these existing stigmas is that the problem of delaying or/and the refusal of HIV testing is a health dilemma faced by many LGBTQIA+ individuals on a global scale. This has led to the lack of changes in the global rate of HIV/AIDS, despite the fact that the technological use of medicine is meant to help in decreasing HIV/AIDS rate (Beyrer et al., Citation2013). HIV prevention and detection, however, become ineffective and can lead to developments of AIDS if individuals who have engaged in sexually risky behaviours do not get HIV tested within the optimal period, which is about three months after a suspected risk (Mavedzenge, Citation2013). Furthermore, individuals who present late to HIV testing tend to show more additional infectious agents such as syphilis and gonorrhoea as well as symptoms including but not limited to weight loss, lymphadenopathy and peripheral neuropathy (Joore et al., Citation2015).

In addition to assessing HIV testing rates among genders, studies in the past suggest that non-white MSM populations have a higher risk of becoming HIV positive, despite having the access to HIV testing (Matthews et al., Citation2016). Matthews et al. (Citation2013)) also predicted that black MSM have a very high chance (60.73%) of becoming HIV positive by the age of 40, based on the annual incidence rate from past studies. Finally, Celentano (Citation2005) suggested that African-Americans at age 25 have the highest HIV seroprevalence, or level of HIV pathogen presented in a blood serum.

Further, a limited number of HIV-related studies show that lower rates of HIV testing in the MSM population may have a strong correlation with different psychological barriers, which seems to be consistent when comparing MSM populations in different countries. For example, Holtzman et al. (Citation2016) found that a quarter of the MSM participants living in Canada have never gotten HIV tested, and such a finding may be linked to internalized homophobia. Cai et al. (Citation2015) found that MSM living in Shenzhen, China, have low HIV testing rate (48%) due to lack of knowledge about HIV and HIV testing. In addition, Song et al. (Citation2011) conducted a survey study in Beijing, China, suggesting that 28% of MSM participants who have never been HIV tested reported that ‘psychological barriers were as follows: perceived low risk of infection and fears of being stigmatized’ (p. 7, 2011). Finally, Safren et al. (Citation2006) surveyed 62 MSM outreach workers in Chennai, India. The results showed that while half of the participants have never gotten HIV tested, more than half of the participants reported that they would rather not know they had HIV until they were sick, indicating a possible showing of denial and lack of awareness of potential severity of delayed HIV diagnosis.

Although previous findings may suggest that there is a link between MSM’s reluctance in getting HIV tested and psychological barriers, it is unclear whether non-MSM individuals who identify themselves as LGBTQIA+ would have similar psychological barriers when getting HIV tested. Furthermore, the amount of research completed in this area is more focused on a specific group based on race, geographical area or people who classify as some sexual orientation(s). For example, Boone et al. (Citation2016) focused mainly on internalized stigma and related concerns among black gay and bisexual men, where 227 young black gay and bisexual men aged from 18 to 34 were asked to complete a cross-sectional survey. The results show that the relationship between psychological distress and HIV/AIDS stigma were significant for participants who were HIV positive (34% of total participants) while insignificant for the rest of participants who were HIV negative. Choi et al. (Citation1995) discussed some concerns regarding HIV risks, but the targeting group was limited to Asian men who live in San Francisco. Finally, recent cases have addressed some of the key factors that may contribute to increasing HIV detection in many individuals presenting late to HIV testing, but the group only focused on the MSM (Beyrer et al., Citation2012, Citation2013).

On the other hand, non-MSM studies relevant to HIV/AIDS infection and testing are very minimal. For example, Herbst et al. (Citation2007) found that male-to-female (MTF) transgender individuals have high HIV infection rates due to sexually risky behaviours, but the reasons behind their reluctance in getting HIV testing remain unclear. It is clear that most of the HIV-testing related studies done in the past exclusively focused on one or two groups that meet those studies’ criteria (Example: race, sexual orientation, age group, etc.) rather than being inclusive of all LGBTQIA+ populations.

Given the almost exclusive focus of prior work on MSM, much more research needs to be done. The purpose of this research is to survey a large group that is inclusive of all LGBTQIA+ individuals to address the following research questions: 1) What is the general attitude of LGBTQIA+ individuals towards HIV testing? 2) What is the relationship between participants’ level of outness/peer openness and their general attitude towards HIV testing? 3) Are there any other factors that may be contributing to the attitude of LGBTQIA+ individuals towards HIV testing? Outness is defined as the degree to which individuals are open about their same sex attraction (Wilkerson et al., Citation2016). Similarly, peer openness refers to the degree to which individuals are open about their same sex attraction to their non-family friends or peers.

This research hypothesizes that LGBTQIA+ individuals who have a lower level of outness and peer openness have a significantly different attitude towards HIV testing than the ones who have a higher level of outness and peer openness. This hypothesis is based on an analysis of recent studies which suggest that factors such as social stigma and discrimination play a crucial role in the choices of MSM in many countries, especially in less developed countries (Liao et al., Citation2015; Nel et al., Citation2012). For example, Nel et al. (Citation2012) conducted a study surveying 280 HIV-untested South African men and found that more than half of participants reported that their reasons for not getting HIV tested were their perceptions of not being at risk and fear of being tested. Furthermore, Liao et al. (Citation2015) identified that HIV/AIDS-related stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes were independently associated with several factors such as bisexual behaviours, low HIV testing rate, lower HIV-related knowledge and risk behaviours.

Additional studies found that there are more psychological factors involved in the reluctance of MSM getting HIV tested (Flowers et al., Citation2012; Schwartz et al., Citation2015). For example, Flowers et al. (Citation2012)) conducted a study in the UK suggesting that fear and other psychological barriers may also play an important factor in MSM’s decision in getting HIV tested. In addition, Schwartz et al. (Citation2015) surveyed 707 MSM living in Nigeria and found that reported fear of seeking health care such as HIV testing and treatment was significantly higher in the period of post-Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act than in the period of pre-Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act. Overall, previous studies completed in other groups of individuals classifying as a specific sexual orientation (Example: MSM) indicate that psychological barriers can be the contributing factor in terms of getting HIV tested, which leads to the proposed hypothesis for this research.

The continuous modification of the LGBTQIA+ acronym is also an indication that careful design of a relevant survey is needed. The survey used in this study was designed in a manner that is inclusive of all LGBTQIA+ individuals. For example, the demographic section of this survey includes a question asking for the participant’s sexual orientation and gender, and it offers the participants more than a single option. This is one of the key issues identified in the current community, where individuals classified as more than one of the LGBTQIA+ acronym found themselves being questioned about their sexual orientation(s), which can be explained by the wide and diverse range of gender and sexual identification in the LGBTQIA+ community (Warner & Shields, Citation2013). In addition, the question includes an ‘other’ option where it allows the participant to manually type their classified sexual orientation(s) and gender. This was added because there are more terminologies indicated in the acronym where individuals may identify themselves as Pansexual, Demisexual and other sexual orientations that are used less frequently (Galupo et al., Citation2016), which means it is inevitably crucial to include additional terms that may not be used commonly by LGBTQIA+ individuals. Finally, an ‘other’ option was also included in the question where it evaluates the participant in terms of their reasons for not getting HIV tested often. This was added because the experiences of all LGBTQIA+ individuals are not uniform, which means that there could be multiple reasons that contributed to a person’s choice in getting HIV tested (Smit et al., Citation2011).

The limited research in this area leaves many questions unanswered. For example, most of the existing literature measured outness or being out as a dichotomous variable, that is, either out to anyone or not being out at all (Kosciw et al., Citation2015). The effects of degree of openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity on observed outcomes were not examined. Consequently, little is known about the relationship between outness and LGBTQIA+ individuals’ experiences of victimization, misunderstanding, or rejection. The purpose of the current study is to fill in the literature gap and determine whether there is a significant relationship between predictor variable(s) with the general attitude of LGBTQIA+ individuals, which may help inform future research leading to positive outcomes.

Methods

Measures

A three-part survey was passed out via quota sampling method. The survey used for this study evaluates whether the two predictor variables, the level of outness and peer openness, individually and together predict the response variable, the general attitude of HIV testing of participants. To begin, the level of outness section evaluates whether the participants have come out to their family and non-family peers. On the other hand, the peer openness section evaluates the participants’ perspectives towards on openness their family and non-family peers feel towards their sexual orientation, if applicable. Finally, the general attitude towards HIV testing section asks the participants regarding their knowledge of HIV, HIV testing, the frequency of getting HIV tested and reasons of not getting HIV tested often (if applicable). There is also a demographic section and a supplemental section where the information collected is used for supplemental purposes in the discussion section of this project.

The first author developed this survey using three steps to pilot test it prior to implementation. The first author initially generated a pool of 45 items from literature related to outness, peer openness, and the general attitude towards HIV. Then, three experts, including a researcher in survey studies and two health professionals who were considered themselves as LGBTQIA+ individuals, reviewed the items for face validity and clarity. Finally, LGBTQIA+ individuals completed the survey and gave feedback on appropriateness and relevance of the survey questions. The final number of items were reduced and revised based on experts’ reviews and feedback from the pilot test. shows the Cronbach’s Alphas and examples for outness, peer openness, and attitude towards HIV.

Table 1. Outness, peer openness, Cronbach’s Alphas, and examples.

Procedure

The survey was distributed electronically through sequential sampling. Five batches of survey were sent out: 1) on July 13 through various LGBTQIA±Friendly and Safe Space groups on Facebook; 2) on July 20 through various LGBTQIA±Friendly and Safe Space groups on Facebook; 3) on July 27 through various LGBTQIA±Friendly and Safe Space groups on Facebook; 4) on August 5 at LGBT Center in the capital city of a southeast state in the United States; and 5) on August 24 at LGBT Center in the capital city of a southeast state in the United States. The first three batches of survey answers were collected online, while the last two batches of participants were recruited in person, but the survey answers were submitted online. With the statistical test being approved by Institutional Review Board at the university located in a medium-sized city of the southeast state, each survey answer was then scored and analysed statically with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, where four separate multiple regression tests were performed. A p-value <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Results

Sample characteristics

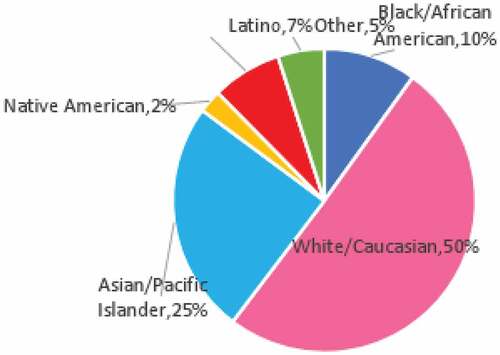

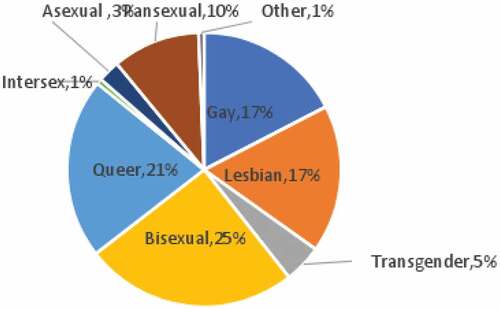

A total of 121 participants were surveyed. The participants’ age ranged from 18 to 56 years old, and the mean age of participants was 24.4 years old. Overall, the participant group was racially diverse: 50.41% White/Caucasian, 24.8% Asian, 10.0% Black/African American, 7.44% Latino, 2.48% Native American and 4.96% Other. Participants choosing ‘Other’ as an option in the race question were Middle Eastern or mixed. A majority of the participants were females (65.3%), followed by males (27.3%). The rest of the participants (7.44%) choosing ‘Other’ in the gender question either identified themselves as genderqueer, genderfluid, non-binary or transgender. In terms of sexual orientation, the participant group was relatively diverse: 22.3% Gay, 22.3% Lesbian, 5.79% Transgender, 32.2% Bisexual, 27.3% Queer, 0.83% Intersex, 3.31% Asexual and 14.05% Other. Participants choosing ‘Other’ option identified themselves as Pansexual or Homoflexible. Among all participants, 21.5% identified themselves as two or more types of sexual orientation. A visual representation of participants by race and participants by sexual orientation is shown in , respectively.

Descriptive results

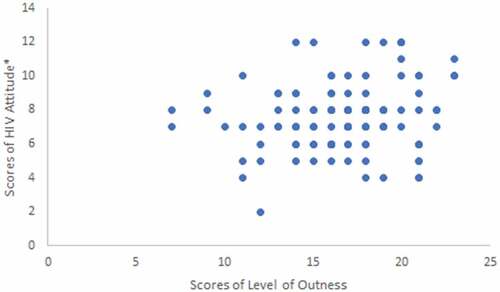

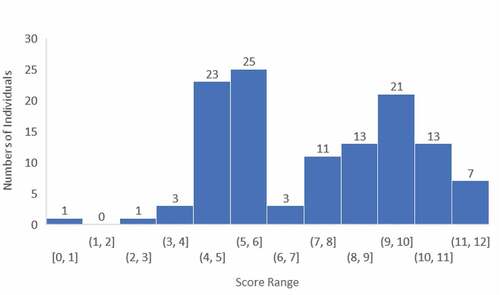

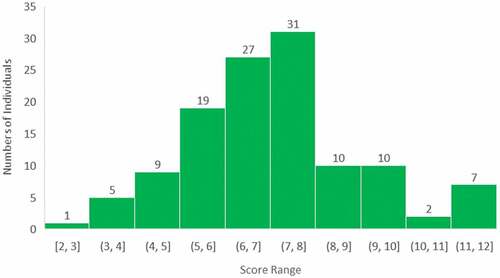

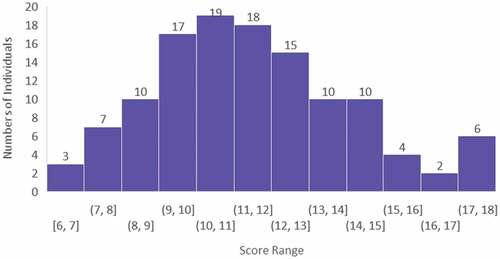

The statistical test for this study includes a multiple regression model, which evaluates the statistical significance of participants’ scores obtained from the survey. Some of the questions were used for scoring their corresponding categories, while other questions were used for supplemental purposes. Questions 6 and 7 were used for scoring a participant’s peer openness. Questions 5, 8, 9 and 12 were used for scoring a participant’s level of outness. Questions 12, 13, and 14 were used for scoring a participant’s attitude towards HIV testing. Two different types of total scores were used for the Attitude Towards HIV Testing section, with one of the total scores only combined scores from Questions 12 and 13 while the other total score combined scores from Questions 12, 13 and 14. A high Peer Openness score indicates a higher acceptability of a participant’s peers (family and friends) towards such participant’s sexual orientation(s), while a low Peer Openness score indicates a lower acceptability of a participant’s peers (family and friends) towards such participant’s sexual orientation(s). A high Level of Outness score indicates that a participant is more comfortable with his or her sexual orientation to the surrounding while a low Level of Outness score indicates that a participant is less comfortable with his or her sexual orientation to the surrounding. A high HIV attitude score indicates that a participant feels generally positive about HIV testing while a low HIV attitude score indicates that a participant feels generally negative about HIV testing. Histogram representations of scores for each category are shown in . Scatterplot representations of Level of Outness scores versus HIV attitude scores are shown in .

Figure 3. Peer openness score of participants. The range of the score was 0–12, with the exception of 2 points, where no participant scored such a score. The mean of the score was 7.79.

Figure 4. Level of outness score of participants. The range of the score was 7–23. The mean of the score was 16.69.

Figure 5. Total scores from familiarity with HIV + familiarity with HIV testing of all participants. The range of score was 2–12. The mean of the score was 7.55.

Figure 6. Total scores from familiarity with HIV + familiarity with HIV testing + importance with HIV testing. The range of the score was 6–18. The mean of the score was 12.0.

Statistics: multiple linear regression

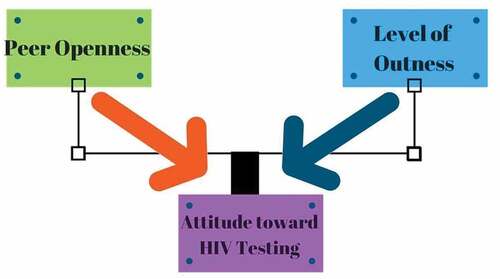

Together, the participants’ obtained scores from Peer Openness and Level of Outness section were used for evaluating the attitude towards HIV Testing together and individually. A schematic representation of multiple linear regression model for this study is shown in .

The two predictor variables are peer openness and level of outness and the response variable is the attitude towards HIV testing. Each colour arrow represents the relationship between each predictor variable and response variable individually. The boxed lines represent the relationship between two predictor variables and response variable together.

Four types of multiple linear regression tests were performed on SPSS. Scores used for the predictor variables (Peer openness and Level of Outness) were the same for all four tests. On the other hand, the scores used in dependent variable (Attitude towards HIV testing) for the first two statistical tests used total score obtained from Questions 12 and 13 (Familiarity with HIV + Familiarity with HIV Testing), while the scores used in dependent variable for the last two statistical tests used total score obtained from Questions 12, 13 and 14 (Familiarity with HIV + Familiarity with HIV Testing + Importance of HIV Testing). The first and third test involves a regression test using standard selecting method, while the second and fourth tests involve a regression test using stepwise selection method. The p-value of each test is presented in . All p-values appear to be lower than 0.05, except for the second test, which is slightly above 0.05 (p = 0.055), suggesting that Level of Outness, comfortability of a participant regarding his or her sexual orientation, is a significant factor of LGBTQIA+ individuals’ attitudes towards HIV testing.

Table 2. P-values for multiple regression tests.

Discussion

Statistical analyses of this study strongly suggest that Level of Outness, comfortability of a participant regarding his or her sexual orientation, is a significant factor of LGBTQIA+ individuals’ attitudes towards HIV testing. This can be explained by Rosario’s study in 2006, where the coming-out process of young gay and bisexual men may be associated with better mental health, better knowledge of HIV prevention and fewer sexually risky behaviours. Although not directly related to the attitude towards HIV testing, the significance between this and level of outness of LGBTQIA+ individuals may still have some relevance to such finding.

Peer openness, on the other hand, may not play a significant role in LGBTQIA+ individuals’ attitudes towards HIV testing (P > .05, see ). This may be explained by the nature of the survey, in which participants may have self-reported answers based on their own social desirability (Knox et al., Citation2011). Such discrepancy was also found in Knox et al.’s MSM study, where the results were contradictory, such that the action of having HIV tested multiple times was positively correlated with lack of social support (Knox et al., Citation2011). Although the survey for this study was designed in a manner that accommodates a participant’s privacy and is anonymous, the possibility of participants answering questions based on their own social desirability is still possible and should not be ruled out.

Other than the discrepancies discussed above, there could also be other factors that contribute to the potentially inaccurate data obtained from this study. For example, the age group that participated in the current study was most in the 18- to 30-year-old age range, with few participants (<5%) who were over the age of 30. This can be explained by Mackellar’s study in 2005, which raised the concern that many HIV-related studies have fewer responses from MSM who are over 30 years old (MacKellar et al., Citation2005). MacKellar suggested that this limitation can be explained by the possibilities that older MSMs are less likely to be engaged in the following items: 1) Attending MSM venues; 2) Being open about their sexual orientations; 3) Disclosing their private information, including HIV-status and whether he is sexually active (MacKellar et al., Citation2005).

Other than the very small number of participants in the age group of 30 or older, the participants were also majority female Caucasians, and this could contribute to the possible inaccuracy and bias of data. This could be explained by the nature of quota sampling, where individual participants were selected non-randomly and were therefore less likely to be representative of the whole LGBTQIA+ populations. Such concern can also be further addressed in future research, which may apply random sampling techniques such as stratified sampling. Having a stratified sampling can allow a selected participant group to be more representative due to the randomness of its nature (Institute of Medicine, Citation2011).

In addition to the scores obtained from the multiple choices section, further observations were noted in the supplemental answers. Interestingly, multiple participants reported that they do not get HIV tested due to the fact that they are in a secure and monogamous relationship. Although this may or may not have impacted their perspectives and attitudes towards HIV testing, this factor could be used as a potential predictor in follow-up research. In addition, more than one individual who classified themselves as transgender made comments regarding not enough questions made for exclusively transgender individuals. This could indicate a potential need in modifying survey questions for follow-up studies, especially if these follow-up studies are designed for a rather narrower participant pool. Another interesting remark made by some of the participants suggested that the problem of low HIV testing rate pertains to the way HIV testing is perceived in different public health settings, where it is often portrayed negatively and could lead to the reluctance of some LGBTQIA+ individuals in getting HIV tested. Nevertheless, this question could be incorporated in future study where such concern is addressed.

In addition to employing random sampling methods, additional factors could also be used in future research to compare with LGBTQIA+ individuals’ attitude towards HIV testing. For example, numbers of HIV studies in the past have used different socioeconomic predictors such as financial status to evaluate participants and their frequency in HIV testing (Rizza et al., Citation2012). In addition, studies such as Dowson’s also use predictors such as knowledge towards HIV testing to predict a participant’s reasons in presenting to HIV testing later than the optimal period (Dowson et al., Citation2011). Although the predictors used in the studies mentioned above did not measure a LGBTQIA+ individual’s attitude towards HIV testing, these factors may still be useful for future research, since research done in this area again is very limited. More robust research with valid data is needed to make further inference about any other potential predictors that may link to a LGBTQIA+ individual’s attitude towards HIV testing.

Other than the possible modifications of current research methods, further improvements could be made regarding sampling locations. To begin, sampling locations could be conducted to multiple LGBT centres instead of just one. It may also be essential to make survey methods consistent such that it is conducted either virtually or in-person, but not both. This could be explained by the lack of supplemental responses provided by the participants who completed the survey in-person. Although lack of supplemental responses does not directly skew the result in the current study, future studies that include mandatory-free response sections may need to consider the different natures between virtually- or in-person-conducted surveys. Nevertheless, this observation could be helpful in future studies, especially if the modified survey includes a free response section that is no longer supplemental.

Since this survey was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also likely that there may be additional factors that may hinder or encourage community members to get HIV tested. For example, ‘opt-out’ HIV testing program has been implemented in emergency room of Florida hospitals, where this establishment has ‘successfully identified patients with undiagnosed HIV infection and improved their engagement in HIV care’ (Eckardt et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, Stanford et al. (Citation2021) has found that COVID-19 pandemic has negative consequence on HIV care and prevention programmes such as routine HIV screening. For example, there was a 49% reduction in University of Chicago of Medicine (UCM) reporting from 1 January to 30 April, 2020 (Stanford et al., Citation2021). Overall, COVID-19 pandemic appeared to add some extra layers of barriers against HIV screening which should be identified and addressed by researchers of relevant areas as well as public health administrations.

Limitations

The small sample size of this survey study is a limitation. Cautions need to be taken for generalization of the findings. Another limitation of the study is the limited measure items for each variable. Future research needs to be conducted to further verify the variables with additional measures to examine similar constructs. Another limitation exists in the design of this survey study attempting to explore a complicated phenomenon. Future researchers may consider mixed-methods approach to examining multi-level and multi-faceted factors about the wellbeing of this very diverse population.

Conclusion

Despite all the existing limitations found in this study, the result does show a rather promising start of the topic of interest for future research. With the improvement of sampling methods and modifications of survey design, future research in similar studies could potentially produce data that is less error-prone. Also, data found in this study could also be used for comparison in future research with similar or identical similar topic of interest. More promising data obtained in future research can also lead to a better understanding of non-heterosexual individuals’ attitudes towards HIV testing or/and reasons for the reluctance of getting HIV tested. Such progress may also lead to a more reliable identification of psychological factors that contribute to an LGBTQIA+ individual’s reluctance in getting HIV tested. Ultimately, this would potentially allow the medical providers and public health workers in the relevant area to come up with an intervention plan that is most effective and inclusive of all non-heterosexual individuals.

Overall, the study showed that level of outness may be a significant variable in predicting a LGBTQIA+ individual’s attitude towards HIV testing, while peer openness showed no statistical significance. Further tests may be needed to validate the relationship among these variables. The long-term impact of COVID-19 on LGBTQIA+ individuals may affect how they perceive HIV testing and follow-up treatment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chang X. Xu

Chang X. Xu is a 4th year medical student concentrating on combined internal medicine and pediatrics. Chang is particularly passionate about serving children and adults from under-resourced backgrounds.

Yaoying Xu

Dr. Yaoying Xu is a Professor in Counseling and Special Education Department and Director of the International Educational Studies Center at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Education. Dr. Xu is devoted to promoting Education Beyond Borders for the quality of life of everyone from everywhere through strong mental health.

References

- Balsam, K. F., Molina, Y., Beadnell, B., Simoni, J., & Walters, K. (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT people of color microaggressions scale. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023244

- Beyrer, C., Baral, S., Griensven, F., Goodreau, S. M., Chariyalertsak, S., Wirtz, A., & Brookmeyer, R. (2012). Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. The Lancet, 380(9839), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6

- Beyrer, C., Sullivan, P., Sanchez, J., Baral, S., Collins, C., Wirtz, A., Altman, D., Trapence, G., & Mayer, K. (2013). The increase in global HIV epidemics in MSM. AIDS, 27, 2665–2678. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000432449.30239.fe

- Boone, M. R., Cook, S. H., & Wilson, P. A. (2016). Sexual identity and HIV status influence the relationship between internalized stigma and psychological distress in black gay and bisexual men. AIDS Care, 28, 764–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1164801

- Brown, G., Leonard, W., Lyons, A., Power, J., Sander, D., Mccoll, W., Johnson, R., James, C., Hodson, M., & Carman, M. (2016). Stigma, gay men and biomedical prevention: The challenges and opportunities of a rapidly changing HIV prevention landscape. Sexual Health, 14(1), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH16052

- Cai, R., Cai, W., Zhao, J., Chen, L., Yang, Z., Tan, W., Zhang, C., Gan, Y., Zhang, Y., & Tan, J. (2015). Determinants of recent HIV testing among male sex workers and other men who have sex with men in Shenzhen, China: A cross-sectional study. Sexual Health, 12(6), 565. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH15109

- Celentano, D. D. (2005). Race/Ethnic differences in HIV prevalence and risks among adolescent and young adult men who have sex with men. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 82(4), 610–621. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti124

- Choi, K. H., Coates, T. J., Lew, S., & Chow, P. (1995). High HIV risk among gay Asian and Pacific Islander men in San Francisco. AIDS, 9(3), 306–308. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-199509030-00019

- Dowson, L., Kober, C., Perry, N., Fisher, M., & Richardson, D. (2011). Why some MSM present late for HIV testing: A qualitative analysis. AIDS Care, 21(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.597711

- Eckardt, P., Niu, J., & Montalvo, S. (2021). Emergency room “Opt-Out” HIV testing pre- and during COVID-19 pandemic in a large community health system. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, 20, 23259582211041260. PMID: 34488480; PMCID: PMC8427921. https://doi.org/10.1177/23259582211041260

- Flowers, P., Knussen, C., Li, J., & Mcdaid, L. (2012). Has testing been normalized? An analysis of changes in barriers to HIV testing among men who have sex with men between 2000 and 2010 in Scotland, UK. HIV medicine, 14(2), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.01041.x

- Galupo, M. P., Ramirez, J. L., & Pulice-Farrow, L. (2016). “Regardless of their gender”: Descriptions of sexual identity among bisexual, pansexual, and queer identified individuals. Journal of Bisexuality, 17(1), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2016.1228491

- Herbst, J. H., Jacobs, E. D., Finlayson, T. J., Mckleroy, V. S., Neumann, M. S., & Crepaz, N. (2007). Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 12(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3

- Holtzman, S., Landis, L., Walsh, Z., Puterman, E., Roberts, D., & Saya-Moore, K. (2016). Predictors of HIV testing among men who have sex with men: A focus on men living outside major urban centres in Canada. AIDS Care, 28(6), 705–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1164288

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. National Academic Press.

- Joore, I. K., Arts, D. L., Kruijer, M. J., Charante, E. P., Geerlings, S. E., Prins, J. M., & Bergen, J. E. V. (2015). HIV indicator condition-guided testing to reduce the number of undiagnosed patients and prevent late presentation in a high-prevalence area: A case–control study in primary care. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 91(7), 467–472. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052073

- Kelleher, C. (2009). Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 22, 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070903334995

- Knox, J., Sandfort, T., Yi, H., Reddy, V., & Maimane, S. (2011). Social vulnerability and HIV testing among South African men who have sex with men. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 22, 709–713. https://doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2011.010350

- Kosciw, J. G., Palmer, N. A., & Kull, R. M. (2015). Reflecting resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6

- Kwan, C. K., Rose, C. E., Brooks, J. T., Marks, G., & Sionean, C. (2016). HIV testing among men at risk for acquiring HIV infection before and after the 2006 CDC recommendations. Public Health Reports, 131(2), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491613100215

- Liao, M., Wang, M., Shen, X., Huang, P., Yang, X., Hao, L., Tao, P., Wu, X., Jia, D., Kang, Y., & Jia, Y. (2015). Bisexual Behaviors, HIV knowledge, and stigmatizing/discriminatory attitudes among men who have sex with men. Plos One, 10(6), e0130866. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130866

- MacKellar, D., Valleroy, L., Secura, G., Behel, S., Bingham, T., Celetano, D., Koblin, B., LaLota, M., McFarland, W., Shehan, D., Thiede, H., Torian, L. V., & Janssen, R. S. (2005). Unrecognized HIV infection, risk behaviors, and perceptions of risk among young men who have sex with men: Opportunities for advancing HIV prevention in the third decade of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 38(5), 603–614. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qai.0000141481.48348.7e

- Matthews, D. D., Herrick, A. L., Coulter, R. W. S., Friedman, M. R., Mills, T. C., Eaton, L. A., Mavedzenge, S. N., Baggaley, R., & Corbett, E. L. (2013). A review of self-testing for HIV: Research and policy priorities in a new era of HIV prevention. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 57(1), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit156

- Matthews, D. D., Herrick, A. L., Coulter, R. W., Friedman, M. R., Mills, T. C., Eaton, L. A., Wilson, P. A., & Stall, R. D. (2016). Running backwards: Consequences of current HIV incidence rates for the next generation of Black MSM in the United States. AIDS Behavior, 20(1), 7–16.

- Mavedzenge, S. N., Baggeley, R., & Corbett, E. L. (2013). A review of self-testing for HIV: Research and policy priorities in a new era of HIV prevention. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 57(1), 126–138.

- Nel, J. A., Yi, H., Sandfort, T. G. M., & Rich, E. (2012). HIV-untested men who have sex with men in South Africa: The perception of not being at risk and fear of being tested. AIDS and Behavior, 17(S1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0329-4

- Rizza, S. A., Macgowan, R. J., Purcell, D. W., Branson, B. M., & Temesgen, Z. (2012). HIV screening in the health care setting: Status, barriers, and potential solutions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 87(9), 915–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.06.021

- Rosario, M., Schrimshaw, E. W., & Hunter, J. (2006). A model of sexual risk behaviors among young gay and bisexual men: Longitudinal associations of mental health, substance abuse, sexual abuse, and the coming-out process. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(5), 444–460. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.444

- Safren, S. A., Martin, C., Menon, S., Creer, J., Solomon, S., Mimiaga, M. J., & Mayer, K. H. (2006). A survey of MSM HIV prevention outreach workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18 (4). https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2006.18.4.323

- Schwartz, S. R., Nowak, R. G., Orazulike, I., Keshinro, B., Ake, J., Kennedy, S., Njoku, O., Blattner, W. A., Charurat, M. E., & Baral, S. D. (2015). The immediate effect of the same-sex marriage prohibition act on stigma, discrimination, and engagement on HIV prevention and treatment services in men who have sex with men in Nigeria: Analysis of prospective data from the TRUST cohort. The Lancet HIV, 2, 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00078-8

- Smit, P. J., Brady, M., Carter, M., Fernandes, R., Lamore, L., Meulbroek, M., Ohayon, M., Platteau, T., Rehberg, P., Rockstroh, J. K., & Thompson, M. (2011). HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: A literature review. AIDS Care, 24(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.613910

- Song, Y., Li, X., Zhang, L., Fang, X., Lin, X., Liu, Y., & Stanton, B. (2011). HIV-testing behavior among young migrant men who have sex with men (MSM) in Beijing, China. AIDS Care, 23(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.487088

- Stanford, K. A., McNulty, M. C., Schmitt, J. R., Eller, D. S., Ridgway, J. P., Beavis, K. V., & Pitrak, D. L. (2021). Incorporating HIV screening with COVID-19 testing in an urban emergency department during the pandemic. JAMA internal medicine, 181(7), 1001–1003. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0839

- Warner, L. R., & Shields, S. A. (2013). The intersections of sexuality, gender, and race: Identity research at the crossroads. Sex Roles, 68, 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0281-4

- Wilkerson, J. M., Noor, S. W., Galos, D. I., & Rosser, B. R. S. (2016). Correlates of a single-item indicator versus multi-item scale of outness about same-sex attraction. Archives of Sex Behavior, 45(5), 1269–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0605-2

- Wilson, P. A., Stall, R. D., Coulter, R. W. S., Friedman, M. R., Mills, T. C., Eaton, L. A., Wilson, P. A., & Stall, R. D. (2015). Running backwards: Consequences of current HIV incidence rates for the next generation of black MSM in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 20(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1158-z