ABSTRACT

Age at the onset of menarche is affected by several factors. However, the characterization of such factors in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) remains partly elusive. We investigated the factors influencing the mean menarcheal age in schoolgirls from Sharjah, UAE. We also evaluated the menstrual knowledge and hygiene practices in the study population. We recruited 410 schoolgirls aged 8–17 years in this cross-sectional study. Data were obtained via a self-administered questionnaire. The mean age at menarche was 11.5 years (±1.17 SD) in the study population. A significant correlation was found between lower household income and delayed age at menarche (p = 0.005). Students who were less than 12 years old attained menarche earlier than older students (p = 0.001). Among the participants, 57.7% had good knowledge about menstruation and 54.7% adopted adequate hygiene practices. The mean age at menarche in the UAE is lower than in other Gulf regions. Earlier implementation of menstrual education programmes at schools is recommended.

Introduction

Menarche, the first menstrual period, is considered a critical milestone in a female adolescent’s life. It usually occurs between the ages of 10 and 16 years, with an average age of 12.4 years (Marques et al., Citation2022). Multiple studies were conducted among populations with similar environmental factors, cultural practices, and geographical locations related to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) residents; however, no adequate evidence was found regarding the average age at menarche in the UAE. In other Gulf countries, the average age at menarche ranges between 12.08 and 13.3 years. Among 1273 Kuwaiti students aged 15–19, the mean age at menarche was 12.41 years (Al-Awadhi et al., Citation2013). The average of 683 Omani students aged 11.5–18.5 years was 13.4 + 0.09 years (Musaiger, Citation1991). Additionally, 304 Saudi Arabian Students aged 9-16 had an average age of 12.08 (Shaik et al., Citation2015). It has been noted that the age at menarche decreased over the years. For example, the median age at menarche in the United States decreased from 12.1 years in 1995 to 11.9 years in 2013–2017 (Goldberg et al., Citation2020). Moreover, recently, a declining trend was observed in the menarcheal age among Indian women (Meher & Sahoo, Citation2024). The decline in age at menarche is associated with multiple factors, including place and type of residence, parental educational level and occupation, stress, physical activity, and food consumption patterns. Another important predictor of early onset of menarche is body mass index (BMI); studies showed that childhood obesity is attributed to early onset of menarche (Li et al., Citation2017).

Previous studies have noticed physiological and psychological consequences related to early or late menarche. Early menarche may cause psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, substance use, as well as suicidal behaviour in adolescents (Lee, Citation2021). It may also lead to increased susceptibility to health problems like breast cancer and endometrial cancer, fertility impairment, and type 2 diabetes (Braun et al., Citation2016; Goldberg et al., Citation2020; Lakshman et al., Citation2008). Early menarche is also associated with developing complications in adult life (Bubach et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, early closure of the epiphyseal plate making the young woman’s adult height shorter than her potential genetic height is a known consequence to early menarche (Lee, Citation2021).

It is important for a female to be prepared for her transition into adolescence having proper knowledge about menstruation and menstrual hygiene practices. Unfortunately, the topic of menstruation is considered a taboo and is affected by social, cultural, and religious restrictions leading to inadequate knowledge that is surrounded by misconceptions. Adopting improper menstrual practices can lead to several physical and psychological health issues including reproductive tract infections (Al Mutairi & Jahan, Citation2021; Belayneh & Mekuriaw, Citation2019; Kaur et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, ill preparation and awareness may subject these adolescents to difficulties and challenges at school, home, and social encounters (Kaur et al., Citation2018). Unfortunately, the relevant data from the UAE population is scarce and insufficient.

We aimed to bridge this gap by determining the mean age at menarche among female students in Sharjah, UAE aged 8 to 17 years. We also aimed to evaluate the socio-economic status, obtain anthropometric measurements including height and weight, determine the environmental factors and the level of knowledge the participants have regarding menstruation and related hygiene practices.

Methods

Study design & population

A cross-sectional study was carried out in four private schools across elementary, intermediate, and secondary grade students in Sharjah, the United Arab Emirates, from March to June 2022. The study population included students attending private schools, from the fourth to the twelfth school grades, with ages ranging from 8 to 17 years. Participants who reported diagnosed conditions, such as, endocrine, neurologic, or musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders, and those who were on chronic medications that could potentially influence the natural occurrence of menarche were excluded. Menarche is considered early if it occurs before or at ten years of age and late if it occurs at or later than 15 years of age (De Sanctis et al., Citation2019). Thus, we chose 8 years old as the lower limit for our sample to explore possible early menarche cases. As for choosing 17 as the upper limit, we included the possibility of delayed menarche, to evaluate its significance in investigating the relationship between BMI and age at menarche.

Sampling method

The schools were chosen conveniently in terms of feasibility and location. Four private schools (elementary, intermediate, secondary) were selected. Systematic sampling was applied in each of the four schools. Sections from elementary to secondary school were listed in order, and every 3rd section from each grade was selected. Surveys were distributed to either every fifth or third student of an attendance sheet, depending on the number of students in the classroom, following the exclusion criteria of the study.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Sharjah (REC-21-08-31-02-S). Permission from schools’ authorities was obtained. The questionnaire included a consent form that participants and their guardians read and signed before answering any of the questions to ensure both the privacy and confidentiality of the participants. Participants were free to withdraw from participation at any time during data collection, and their information would have been dismissed. Each questionnaire had a numbered code. The measurements were taken in a private space in school to ensure the privacy and comfort of the students.

Sample size

Sample size was calculated using the Raosoft online sample size calculator. The calculation was based on a 50% response distribution, 5% margin of error, and 95% confidence interval. The online software foundation is based on widely used descriptive studies sample size estimation formula proposed in Scott & Smith (Scott & Smith, Citation1969) also cited by Satian et al. (Sathian et al., Citation2010). The required sample size was 377 for the present study. However, initially, we considered 410 samples for assuming a non-response rate. A total of 7 students reporting chronic endocrine and MSK conditions were excluded from the study. Furthermore, a total of 13 students did not report their age at menarche and thus, were also excluded from the study, leaving the total number of responses at 390 ().

Anthropometric measures

A portable stadiometer and digital scale were used to measure the participants’ height and weight, respectively. Researchers were adequately trained to take the participants’ measurements using the techniques already described (Karim & Qaisar, Citation2020). Briefly, participants were wearing standard school uniforms and were asked to take off their shoes during the process. All anthropometric measures were taken either in the school clinic or in private spaces around the school premises. Height and weight were measured to the nearest 1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula, BMI = weight(kg)/height(m)^2. BMI categories were classified based on the WHO criteria (de Onis et al., Citation2007).

Data collection procedure

Data were collected via a self-administered questionnaire that was developed after reviewing relevant literature and modified as seen fit (Belayneh & Mekuriaw, Citation2019; Idris et al., Citation2021; Kpodo et al., Citation2022; Shaik et al., Citation2015). The questionnaire was prepared in both English and Arabic languages and distributed among targeted students by visiting schools. However, in one of the schools, the questionnaire was administered online since the students were studying online at the time of data collection. Each school was visited twice after obtaining permission, first time to distribute and second time to collect filled questionnaires and the informed consents which were signed by the parents to obtain the anthropometric measurements. All data collectors were knowledgeable and able to clearly communicate the purpose of the research to the students and answer all the concerns and questions that were raised.

The questionnaire consisted of 36 questions divided into six sections including, demographics, menarcheal data, socioeconomic status, environmental factors including dietary habits, physical activity and student’s lifestyle, knowledge about menstruation and menstrual hygiene practices. Most of the questions were close ended except for the menarche date and the parents’ occupation. The questionnaire was piloted among a small number of participants to ensure its clarity and to measure the estimated time taken. It took 10 minutes and all recommendations were considered. The data was collected between March and June 2022.

Statistical analysis

The main objective of the study was calculating the mean age at menarche which was determined using the date of birth and the date of menarche. Participants were asked about the onset of menstruation as a yes/no question, described already (Karim et al., Citation2021). Those who answered yes were further asked to report the grade and date of the onset of menstruation as month/year format. The middle of a year (June) was used if participants failed to report the month (Zegeye et al., Citation2009). We calculated the age at menarche by subtracting the date of birth from the date at which menarche has occurred.

The mean age at menarche was tested against certain factors to investigate if they were statistically affecting the onset of menstruation. Parents’ socioeconomic status, participants’ anthropometric measures, dietary habits, physical activity, lifestyle, and stress which was assessed through asking about whether they had problems with friends, family, or studying.

Students’ menstrual knowledge score was calculated out of the six knowledge-specific questions. Each correct response was given one point, whereas any wrong or don’t know response received a zero mark and thus a knowledge score out of six points was calculated. Accordingly, the mean score of menstrual knowledge (4.17) was used to decide the cut-offs of the rank. Good knowledge of menstruation and menstrual hygiene was given to those respondents who scored 5–6 points and poor knowledge of menstruation and menstrual hygiene was given to those respondents who scored 0–4 points. The two groups (good knowledge and poor knowledge) were tested against factors like the source of information, parents’ socioeconomic status, and the current school grade.

Students’ practice of menstrual hygiene score was calculated following the WHO and UNICEF definition of menstrual hygiene management practice (MHM) (Lyu et al., Citation2020). The practice score was determined using six questions, 1 point was assigned for each of the following: the use of disposable sanitary pad or material, adequate frequency of changing (three or more times in 24 hours), washing the body and genitals twice daily with soap and water or just water, and properly disposing the sanitary material in the toilet or burning it. All the other answers including unanswered questions received no points and a score was calculated out of six. A 6 was considered as having adequate or safe MHM practice, while any other score was considered inadequate or unsafe practice. The two groups (those with adequate practices and those with inadequate practices) were tested against variables like the source of information, parent socioeconomic status, and the current school grade.

All data were coded, entered, and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 22. For univariate analyses, descriptive statistics including measures of central tendency and measures of variability were used. Bivariate analysis was conducted to study the relationship between variables. Inferential statistics tests, including Chi-square, t-test, ANOVA, Kruskal – Wallis and Mann Whitney as appropriate to the type of variables involved were used. The level of significance was set at 5%.

Results

A total of 410 responses were collected, 20 responses were excluded, of which 13 returned incomplete questionnaires, and 7 reported diagnosed conditions of diabetes (n = 4), PCOS (n = 1), thyroid disease (n = 1), and scoliosis (n = 1). Out of the 390 remaining responses, 310 (79.5%) already attained menarche, while 80 (20.5%) did not. Among the menarcheal group, the mean age at menarche was estimated at 11.50 (SD ± 1.17). The mean grade at menarche was estimated at 6.32 (SD ± 1.22).

The biggest percentage of our participants were from ages 12–15 years (53.5%) and from school grades 7–9 (43.1%). More than half of the participants (67.9%) were non-Arab, while 32.1% were Arab. Around half of the participants’ mothers had a bachelor’s degree (54.4%). The most reported jobs for the participants’ mothers were housewives (46.7%). The monthly household income of 26.4% of the participants was between 10,000 and 19999 AED and was between 20,000 and 29000 AED in 26.8% of them ().

Table 1. Distribution of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics among female school students in UAE, Sharjah.

Factors influencing age at menarche

The mean BMI among all the study participants, both menstruating and non-menstruating, was 21.70 (SD ± 4.52). The prevalence of overweight and obesity was 20.4% (n = 79) and 11.9% (n = 46), respectively. More than half of the participants (60.3%, n = 234) had a BMI within the normal range, and only 7.5% (n = 29) were underweight.

Majority of the participants (82.9%, n = 320) performed some form of physical activity. One hundred and twenty-two participants (31.5%) consumed fast food 2 or more times a week, 145 (37.5%) consumed it once a week, 72 (18.6%) consumed it once every 2 weeks, and 48 (12.4%) consumed it once a month or not at all.

Most students (93.3%, 88.2%, 80.3%) stated that they did not experience any problems with their family, friends, and studying, respectively. A total of 172 (44.3%) of the participants spent 3–5 hours on electronic devices, and 36.6% spent more than 5 hours. Around half of the participants (54.6%) spent 3–5 hours studying, and 32.2% spent less than 2 hours.

The median age at menarche was significantly correlated with the current age; younger age groups were attaining their menarche at an earlier age. The relationship was significant between the age groups ‘Less than 12 years’ and ‘12–15 years’, as well as ‘Less than 12 years’ and ‘More than 15 years’ (p = 0.000). There was no significant difference between the mean age at menarche between Arabs and Non-Arabs (p = 0.44). The mean age at menarche showed a trend of being higher in those with low BMI compared to overweight/obese participants; however, the relationship was not statistically significant (p = 0.24). The mean age of menarche was found to be significantly correlated with the monthly household income; participants with lower income were found to attain menarche at an older age. The relationship was significant between the monthly income group ‘Less than 4999 AED’ and ‘Between 5000 AED and 9999 AED’ (p = 0.005). Other factors including consumption of fast food, physical activity, stress, and hours spent studying and on electronics were not significantly correlated with the mean age at menarche ().

Table 2. Comparison of age at menarche in relation to study variables.

Knowledge about menstruation

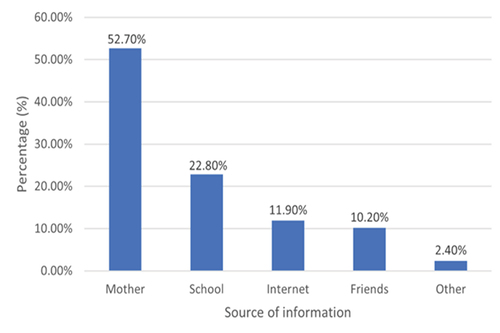

A total of 222 (57.7%) participants had good knowledge about menstruation. However, around half of the participants (48.8%) had adequate knowledge about menstruation before attaining menarche. The majority (84.6%) knew that menstruation is a normal physiological process. Around half of the participants (52.7%) knew that menstruation was caused by hormones, while 26.8% believed it was due to filtering dirty blood. More than half of the participants (60%) knew that the source of menstrual blood was the uterus, while 15.6% believed that it comes from the vagina. Majority of the participants (84.4%) knew that normal menstrual periods last between 3 and 7 days. Most of the participants (87.3%) knew that normal menstrual periods occur once per month (). Furthermore, 52.7% of the participants took information about menstruation from their mothers, followed by school, the internet, and friends ().

Table 3. Participant’s knowledge about menstruation.

Chi-square test was done to evaluate the predictors of knowledge about menstruation. Girls who attained menarche were more knowledgeable about menstruation (66.5%) compared to girls who did not [X2 (1, N = 385) = 50.36, p = 0.000]. Students from grades 7–9 and 10–12 were more likely to have good knowledge about menstruation than those attending grades 4–6 [X2 (2, N = 385) = 76.11, p = 0.000]. Girls whose monthly household income was higher, were more likely to have good knowledge about menstruation than their counterparts [X2 (4, N = 312) = 13.90, p = 0.008]. Girls who obtained information from their mothers and school were more likely to have good knowledge about menstruation compared to girls who did not [Mother info: X2 (1, N = 385) = 4.69, p = 0.030] [School info: X2 (1, N = 385) = 15.99, p = 0.000] ().

Table 4. Chi-square analysis of predictors of knowledge about menstruation among schoolgirls in Sharjah, UAE.

Hygienic practices during menstruation

According to the data obtained, 169 (54.7%) of the participants had adequate and safe menstrual hygiene practices. Most participants (97.1%) used disposable sanitary material during their menstruation. More than half of the participants (74.3%) were able to change their sanitary material 3 times or more per day, while 25.4% were able to change it 1–2 times per day. The majority of participants (97.4%) were able to dispose of their menstrual material properly. Most of the participants washed their body using soap and water (81.8%) and washed their genitalia twice or more per day (92.4%). Around half of the participants (55.8%) used both soap and water to wash their genitalia, while 44.2% used only water ().

Table 5. Participants’ menstrual hygiene practices during menstruation.

Chi-square test was done to evaluate predictors of adequate/safe menstrual hygiene practices. Girls whose mothers work in business and management (69.4%) and healthcare (64.7%) were more likely to have adequate menstrual hygiene practice compared to their counterparts [X2 (5, N = 288) = 13.81, p = 0.017]. Girls who obtained information about menstruation from school were more likely to practice safer menstrual hygiene [X2 (1, N = 309) = 3.90, p = 0.048]. Overall, girls who had good knowledge about menstruation (59.7%) were more likely to have adequate menstrual hygiene practices [X2 (1, N = 309) = 6.28, p = 0.012] ().

Table 6. Chi-square analysis of predictors of adequate menstrual hygiene practices among schoolgirls in Sharjah, UAE.

Discussion

The mean age at menarche among females in UAE is 11.50 years. We found no correlation between BMI and age at menarche. However, we found that a higher income and a better socio-economic status were linked with earlier onset of menstruation. Those who had already reached menarche, were in higher grades, had higher household income, and those who received information regarding menstruation from their mothers, had a greater overall knowledge about menses. Less than half of the girls had good knowledge about menses before having their first period. Moreover, mothers were the primary source of information for female students, while the school played a minimum role in providing knowledge about menstruation. Mother’s level of education, occupation, and knowledge, had a great impact on safe and hygienic practices among girls during menstruation.

Most of the participants had reached menarche at a mean age of 11.5 years (SD ± 1.17) and at a school grade of 6, which is lower than other studies conducted in the Gulf region, for example in Saudi Arabia with a mean age of 12.08 years, and Kuwait with a mean age of 12.41, respectively (Al-Awadhi et al., Citation2013; Shaik et al., Citation2015). Similarly, when looking at other countries and regions such as India, Africa, and the United States, the ages of menarche were found to be 12.4, 13.8, and 12.6, respectively, the age of menarche in the UAE was found to be earlier (Idris et al., Citation2021; Karim et al., Citation2021). Many factors can explain these observed differences, including the variability in data collection methods, geographic, cultural, climatic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, dietary, and genetic differences. Pertaining to our findings, specifically our sample size was relatively small, limited to a single geographical area, and the schools selected had students of almost comparable socioeconomic status. Furthermore, the age of the participants was skewed towards older ages.

In our study, the age at menarche was earlier among girls in younger age groups compared to older ones, which goes in line with the global decline in the age at menarche (Goldberg et al., Citation2020). Several studies have suggested that being overweight, obese, or underweight might alter menarcheal age. Previous studies showed a negative correlation between menarcheal age and obesity (Al-Awadhi et al., Citation2013; Malitha et al., Citation2020; Marques et al., Citation2022). The findings of our study were not statistically significant (p = 0.240); however, participants with lower BMI had a greater mean age of menarche (12-year-old) than those who were overweight or obese (11.3-year-old), in line with a previous study (Shaik et al., Citation2015), which likewise found no correlation between age at menarche and BMI. The insignificant findings may have been attributed to the late collection of anthropometric measurements, done years after attaining menarche as their weight and height may have changed since puberty and is no longer an accurate factor. A better approach would have been to ask the participants about their measurements at the time of menarche; however, that would have been heavily influenced by recall bias. In addition, the low percentage of participants in our study as compared to the previous studies may be another contributing factor to these findings.

We further attempted to find an association between fast food intake and the mean age at menarche; however, the findings were non-significant (p = 0.451). In contrast, previous research found a significant association between eating fast or junk food and early menarche (p = 0.021) (Anita & Simanjuntak, Citation2018; Ramraj et al., Citation2021).

We found a significant correlation between participants’ monthly household income and the age at menarche. Girls having a household monthly income less than 4999 AED experienced a delayed menarche as compared to those with a household monthly income between 5000 AED and 9999 AED. These results are consistent with previous studies conducted in Saudi Arabia Shaik et al. (Citation2015), and Bangladesh (Malitha et al., Citation2020). In addition, a study conducted in India also showed negative association of age at menarche can be attributed to the fact that girls from higher socio-economic backgrounds tend to have better access to nutritious foods and healthcare, which may contribute to an earlier onset of puberty (Meher & Sahoo, Citation2024; Tarannum et al., Citation2017). They may also experience more stress due to academic pressure, extracurricular activities, and social expectations, which can trigger the release of hormones that contribute to early puberty (Mishra et al., Citation2009). Additionally, girls from lower socio-economic backgrounds may be exposed to environmental toxins, such as chemicals, which can interfere with the body’s hormonal systems and delay the onset of puberty (Al-Awadhi et al., Citation2013; Mishra et al., Citation2009).

It is crucial to understand and evaluate the knowledge and practices of schoolgirls towards menstruation, as the level of knowledge largely impacts the behaviour towards menstruation, which in turn would reflect on the incidence of reproductive disorders, future health outcomes, and academic performance (Belayneh & Mekuriaw, Citation2019). Our study showed that 57.7% of the schoolgirls had good knowledge about menstruation, while 42.3% of the participants had poor knowledge. Similar study results from Saudi Arabia reported 36.3% of the students had poor knowledge about menstruation in contrast to other studies done in Southern Ethiopia and India, which showed that 68.3% and 71.3% of the participants had poor knowledge regarding menstruation, respectively (Al Mutairi & Jahan, Citation2021; Belayneh & Mekuriaw, Citation2019; Shanbhag et al., Citation2015). This difference can be explained by the fact that Gulf countries are considered high income with more resources that can be catered to proper health education programmes. Menstruation, especially in developing countries, is considered a social taboo, making women uncomfortable and embarrassed to discuss and gain accurate knowledge (Panda et al., Citation2024). Around half (48.8%) of our participants had adequate knowledge about menstruation before attaining menarche, while a similar study conducted in India showed that only 28.24% of the schoolgirls knew about menstruation before menarche, this further supports the differences in healthcare and education (Shanbhag et al., Citation2015). Despite the superior educational and healthcare systems, half of our participants still lack knowledge before attaining menarche, which can be attributed to the declining age of menarche and failure of the schools to educate the students regarding menstruation physiology and proper hygiene practices at the appropriate age.

We found that 52.7% of the participants received information about menstruation from their mothers, and 22.80% of the participants received it from schools; therefore, schools played a lesser role. These findings are supported by a previous study, which showed that the mother is the primary source of information regarding menstruation for their daughters (Al Mutairi & Jahan, Citation2021). Moreover, it was illustrated that the main source of information regarding menstrual health among girls in low- and middle-income countries are their mothers (Chandra-Mouli & Patel, Citation2017). The reason why mothers are potentially the main source of providing knowledge about menstruation can possibly be the sensitive nature of the topic.

We found that girls who attained menarche, were in higher school grades, and had a higher monthly household income have significantly better level of knowledge about menstruation. These findings are in line with previous studies which demonstrated a significant relationship between the level of knowledge and family monthly income (Al Mutairi & Jahan, Citation2021; Sommer et al., Citation2015). This can be explained by the effect of socioeconomic status on education, which in turn increases the awareness and level of knowledge of schoolgirls.

We found that more than half of the participants (54.7%) had adequate and safe menstrual hygiene practices. This finding is higher than a study conducted in central Ethiopia that demonstrated that only one-third (34.7%) of schoolgirls had adequate and safe menstrual hygiene practices (Bulto, Citation2021). Studies done in Western Ethiopia, Nigeria, and India have also revealed that less than half of the schoolgirls had safe hygiene practice (39.9%, 44.3%, and 36.0% respectively) (Adinma & Adinma, Citation2008; Shanbhag et al., Citation2015; Upashe et al., Citation2015). The discrepancy is most likely due to the difference in socioeconomic status and cultural variations, especially due to the misconceptions and myths related to menstruation as well as lack of access to sanitary materials and ways to dispose of them, which are common in developing countries (Belayneh & Mekuriaw, Citation2019; Kaur et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, occupation of the mothers was investigated to determine their association with menstrual hygiene practices of their daughters. Girls whose mothers worked in business and management (69.4%) and healthcare (64.7%) were more likely to have adequate menstrual hygiene practice compared to their counterparts. Mostly, since mothers working in the health sector have accurate medical knowledge and experience, they can provide this to their daughters. Girls who took their information about menstruation from school were more likely to practice safer menstrual hygiene. This can possibly be attributed to accurate information provided by schools and teachers playing a huge role in equipping the students with the necessary skills to maintain safe and adequate menstrual hygiene practices. This finding is in line with the study conducted in central Ethiopia (Bulto, Citation2021). Overall, girls whose knowledge about menstruation (59.7%) was higher were more likely to have adequate menstrual hygiene, a finding that is supported by studies done in Ethiopia and Bangladesh (Bulto, Citation2021; Haque et al., Citation2014). A good overall knowledge in school students improves their hygiene skills and ensures safe menstrual practices.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study; therefore, the temporal sequence of events could not be determined. Secondly, it was conducted in only one city;therefore, findings could not be generalized to the entire UAE population. Thirdly, as data was collected from participants who have already attained menarche, they may have not been able to accurately report their date of menarche, resulting in recall bias. In addition, their BMI measurements at the time of data collection may not reflect their BMI at the time of menarche. Fourthly, due to the sensitivity of the topic, a limited number of schools especially governmental schools, as they are more conservative in nature, were not explored; this resulted in a lower number of participants and less variation in the socioeconomic status of our respondents. Lastly, more factors could have been investigated in the menstrual knowledge and hygiene practice sections, and conducting a multivariate regression analysis would offer more complete examination of the relationship between variables. Despite these limitations, this study was able to successfully provide preliminary data regarding the mean age at menarche in the United Arab Emirates.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the mean age at menarche among females in UAE was 11.50 years, which is earlier than the age of menarche established in other studies made in the Gulf region and internationally. No previous studies were done in the UAE that could help us relate to the trend in the decline in the age of onset of menarche that has been observed worldwide. Our study does not support a correlation between BMI and age of menarche. However, a higher income and a better socio-economic status were linked with earlier onset of menstruation. More than half of the girls had good knowledge and hygiene practices. On the other hand, less than half of the girls had good knowledge about menses before having their first period. Moreover, mothers were the primary source of information for female students. Mother’s level of education, occupation and general knowledge regarding menstruation, had a great impact on safe and hygienic practices during menstruation.

Recommendations

A national longitudinal study should be done, to monitor females and accurately report their data on menarche and visualize any changes or decline in the age at menarche, as observed in other studies. Although this study did not envision a relationship between BMI and age at menarche, childhood obesity rates and its effect on sexual development should still be evaluated. Furthermore, schools should dedicate more resources to provide better campaigns and lectures regarding menstruation and its hygienic practices, starting at young ages to female students and their mothers. This would help increase awareness regarding the normal physiological changes and consequences of unhygienic practices in a female’s life (Meher & Sahoo, Citation2023).

Acknowledgments

We thank the schoolgirls who gave their valuable response in this study voluntarily. The authors would also like to thank the participating schools for their cooperation and giving permission to contact students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adinma, E. D., & Adinma, J. I. (2008). Perceptions and practices on menstruation amongst Nigerian secondary school girls. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 12(1), 74–14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20695158

- Al-Awadhi, N., Al-Kandari, N., Al-Hasan, T., Almurjan, D., Ali, S., & Al-Taiar, A. (2013). Age at menarche and its relationship to body mass index among adolescent girls in Kuwait. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-29

- Al Mutairi, H., & Jahan, S. (2021). Knowledge and practice of self-hygiene during menstruation among female adolescent students in Buraidah city. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 10(4), 1569–1575. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2321_20

- Anita, S., & Simanjuntak, Y. T. (2018). The correlation between junk food consumption and age of menarche of elementary school student in Gedung Johor Medan. Unnes Journal of Public Health, 7(1), 21–24. https://doi.org/10.15294/ujph.v7i1.17093

- Belayneh, Z., & Mekuriaw, B. (2019). Knowledge and menstrual hygiene practice among adolescent school girls in southern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1595. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7973-9

- Braun, M. M., Overbeek-Wager, E. A., & Grumbo, R. J. (2016). Diagnosis and management of endometrial cancer. American Family Physician, 93(6), 468–474. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26977831

- Bubach, S., Horta, B. L., Goncalves, H., & Assuncao, M. C. F. (2021). Early age at menarche and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors: Mediation by body composition in adulthood. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80496-7

- Bulto, G. A. (2021). Knowledge on menstruation and practice of menstrual hygiene management among school adolescent girls in central Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 14, 911–923. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S296670

- Chandra-Mouli, V., & Patel, S. V. (2017). Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0293-6

- de Onis, M., Onyango, A. W., Borghi, E., Siyam, A., Nishida, C., & Siekmann, J. (2007). Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85(9), 660–667. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.07.043497

- De Sanctis, V., Rigon, F., Bernasconi, S., Bianchin, L., Bona, G., Bozzola, M., Buzi, F., De Sanctis, C., Tonini, G., Radetti, G., & Perissinotto, E. (2019). Age at menarche and menstrual abnormalities in adolescence: Does it matter? The evidence from a large survey among Italian secondary schoolgirls. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 86(Suppl 1), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-018-2822-x

- Goldberg, M., D’Aloisio, A. A., O’Brien, K. M., Zhao, S., & Sandler, D. P. (2020). Pubertal timing and breast cancer risk in the sister study cohort. Breast Cancer Research: BCR, 22(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-020-01326-2

- Haque, S. E., Rahman, M., Itsuko, K., Mutahara, M., & Sakisaka, K. (2014). The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: An intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. British Medical Journal Open, 4(7), e004607. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004607

- Idris, I. M., Wolday, S. J., Habteselassie, F., Ghebremichael, L., Andemariam, M., Azmera, R., & Ghebrewoldi, F. H. (2021). Factors associated with early age at menarche among female secondary school students in Asmara: A cross-sectional study. Global Reproductive Health, 6(2), e51. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRH.0000000000000051

- Karim, A., & Qaisar, R. (2020). Anthropometric measurements of school-going-girls of the Punjab, Pakistan. BMC Pediatrics, 20(1), 223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02135-4

- Karim, A., Qaisar, R., & Hussain, M. A. (2021). Growth and socio-economic status, influence on the age at menarche in school going girls. Journal of Adolescence, 86(1), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.12.001

- Kaur, R., Kaur, K., & Kaur, R. (2018). Menstrual hygiene, management, and waste disposal: Practices and challenges faced by girls/women of developing countries. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2018, 1730964. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1730964

- Kpodo, L., Aberese-Ako, M., Axame, W. K., Adjuik, M., Gyapong, M., & Rosier, P. F. W. M. (2022). Socio-cultural factors associated with knowledge, attitudes and menstrual hygiene practices among junior high school adolescent girls in the Kpando district of Ghana: A mixed method study. Public Library of Science ONE, 17(10), e0275583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275583

- Lakshman, R., Forouhi, N., Luben, R., Bingham, S., Khaw, K., Wareham, N., & Ong, K. K. (2008). Association between age at menarche and risk of diabetes in adults: Results from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort study. Diabetologia, 51(5), 781–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-0948-5

- Lee, H. S. (2021). Why should we be concerned about early menarche? Clin Exp Pediatr, 64(1), 26–27. https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2020.00521

- Li, W., Liu, Q., Deng, X., Chen, Y., Liu, S., & Story, M. (2017). Association between obesity and puberty timing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 14(10), 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101266

- Lyu, J. L., Wang, T. M., Chen, Y. H., Chang, S. T., Wu, M. S., Lin, Y. H., Lin, Y. H., & Kuan, C. M. (2020). Oral intake of streptococcus thermophil us improves knee osteoarthritis degeneration: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Heliyon, 6(4), e03757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03757

- Malitha, J. M., Islam, M. A., Islam, S., Al Mamun, A. S. M., Chakrabarty, S., & Hossain, M. G. (2020). Early age at menarche and its associated factors in school girls (age, 10 to 12 years) in Bangladesh: A cross-section survey in Rajshahi District, Bangladesh. Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 39(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-020-00218-w

- Marques, P., Madeira, T., & Gama, A. (2022). Menstrual cycle among adolescents: Girls’ awareness and influence of age at menarche and overweight. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, 40, e2020494. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0462/2022/40/2020494

- Meher, T., & Sahoo, H. (2023). Dynamics of usage of menstrual hygiene and unhygienic methods among young women in India: A spatial analysis. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1), 573. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02710-8

- Meher, T., & Sahoo, H. (2024). Secular trend in age at menarche among Indian women. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 5398. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55657-7

- Mishra, G. D., Cooper, R., Tom, S. E., & Kuh, D. (2009). Early life circumstances and their impact on menarche and menopause. Womens Health (Lond), 5(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.2217/17455057.5.2.175

- Musaiger, A. O. (1991). Height, weight and menarcheal age of adolescent girls in Oman. Annals of Human Biology, 18(1), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014469100001412

- Panda, N., Desaraju, S., Panigrahy, R. P., Ghosh, U., Saxena, S., Singh, P., & Panda, B. (2024). Menstrual health and hygiene amongst adolescent girls and women of reproductive age: A study of practices and predictors, Odisha, India. BMC Women’s Health, 24(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-02894-7

- Ramraj, B., Subramanian, V. M., & Vijayakrishnan, G. (2021). Study on age of menarche between generations and the factors associated with it. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 11, 100758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100758

- Sathian, B., Sreedharan, J., Baboo, S. N., Sharan, K., Abhilash, E. S., & Rajesh, E. (2010). Relevance of sample size determination in medical research. Nepal Journal of Epidemiology, 1(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.3126/nje.v1i1.4100

- Scott, A., & Smith, T. M. (1969). Estimation in multi-stage surveys. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 64(327), 830–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1969.10501015

- Shaik, S. A., Hashim, R. T., Alsukait, S. F., Abdulkader, G. M., AlSudairy, H. F., AlShaman, L. M., Farhoud, S. S., & Neel, M. A. F. (2015). Assessment of age at menarche and its relation with body mass index in school girls of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences, 7(2), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.3126/ajms.v7i2.13439

- Shanbhag, D., Shilpa, R., D’Souza, N., Josephine, P., Singh, J., & Goud, B. R. (2015). Perceptions regarding menstruation and practices during menstrual cycles among high school going adolescent girls in resource limited settings around Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. International Journal of Collaborative Res Intern Med Public Health, 4(7), 1353–1362.

- Sommer, M., Ackatia-Armah, N., Connolly, S., & Smiles, D. (2015). A comparison of the menstruation and education experiences of girls in Tanzania, Ghana, Cambodia and Ethiopia. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(4), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.871399

- Tarannum, F., Khalique, N., & Eram, U. (2017). A community based study on age of menarche among adolescent girls in Aligarh. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20175820

- Upashe, S. P., Tekelab, T., & Mekonnen, J. (2015). Assessment of knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among high school girls in Western Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health, 15(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0245-7

- Zegeye, D. T., Megabiaw, B., & Mulu, A. (2009). Age at menarche and the menstrual pattern of secondary school adolescents in northwest Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health, 9(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-9-29