ABSTRACT

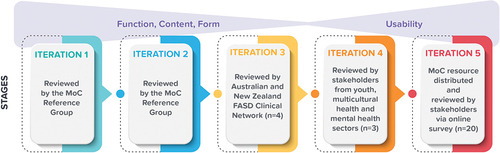

This article describes the development of a Model of Care (MoC) resource to support youth involved with the justice system where a neurodevelopmental disability such as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is suspected. Service staff within the Youth Justice sector were engaged in an iterative process of resource development over a 9-month period. A reference group was established for feedback at each stage, expert advice was sought from the Australian and New Zealand FASD Clinical Network. Five phases of iterative resource development occurred; the first three covered function, form and content of the resource while iterations 4 and 5 mainly pertained to usability. Referral pathway schematics, poster style resources and a user manual were developed and distributed to Youth Justice affiliated organizations. The aim is for the resource to assist in early and appropriate intervention and support for youth with suspected neurodevelopmental disabilities involved in the justice system.

Background

Youth involved with the justice system are an exceptionally vulnerable group, with significant and complex health needs. Histories of trauma, neglect, poor physical and mental health, behavioural problems, and substance use are recurrent among youth entering custody (Perry & Newbigin, Citation2017). The overrepresentation of neurodevelopmental disabilities among youth offenders is also widely acknowledged (Appleby et al., Citation2019; Bower et al., Citation2018; Jonson-Reid et al., Citation2018; McLachlan et al., Citation2019; Shaw, Citation2016). Recent Australian research has documented high rates of neurodevelopmental disabilities (48%) among justice-involved youth, with greater cumulative maltreatment and adversity, earlier offending onset and a greater volume of charges, compared to youth without neurodevelopmental disabilities (Baidawi & Piquero, Citation2021). Another Australian study demonstrated that almost half of all youths in custody in New South Wales Custodial Centres had ‘borderline’ or lower intellectual functioning (measured by IQ assessment), indicating significant impairment (Haysom et al., Citation2014). The research by Haysom et al. (Citation2014) determined that the cognitive functioning of young people in detention is lower than for those in the general community, particularly for receptive verbal skills (the ability to understand what someone is saying). The importance of addressing such significant health issues – many of which contribute to juvenile offending – to reduce recidivism and offset the trajectory towards adult offending is recognized (AIHW, Citation2018; Amnesty, Citation2015; Haight et al., Citation2016).

Of recent concern in Australia is the issue of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) in the youth justice system. FASD is a neurodevelopmental disability resulting from prenatal alcohol exposure, which can lead to lifelong physical, mental, behavioural and learning disabilities (Bower et al., Citation2017). Epidemiological data from Canadian research suggest that as many as 60% of the adolescents with FASD assessed through clinical settings have contact with the criminal justice system, a rate 30 times higher than the general population (McLachlan et al., Citation2019). An Australian FASD prevalence study conducted within a representative sample of young people in detention in Western Australia found that nearly all (89%) had severe neurodevelopmental impairment and over a third had FASD (36%). Most of these young people were undiagnosed prior to the study (Bower et al., Citation2018).

Young people living with FASD typically face several systemic and social disadvantages that can increase the likelihood of involvement with the justice system. For example, individuals with FASD may not be able to make informed choices or understand the consequences of their actions and can be easily manipulated by their peers (Kippin et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the ability to understand and navigate formal criminal justice procedures is substantially poorer amongst young offenders diagnosed with FASD compared to other young offenders (Hand et al., Citation2015). Research also demonstrates that children diagnosed with FASD struggle with depression and anxiety severely impacting their day-to-day life experiences (McLachlan, Citation2017; Stade et al., Citation2006).

Barriers to the provision of adequate support for youth with FASD who have contact with the justice system are complex, occur across multiple levels, and require diverse, integrated, and evidence-based solutions. For example, recent studies of the custodial workforce in Australia have found a lack of specific FASD knowledge and insufficient training to recognize and manage youth with neurodevelopmental disabilities generally (Passmore et al., Citation2018; Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021; Reid et al., Citation2020). Research has also demonstrated that coordination between juvenile justice agencies and treatment providers is often hindered by inadequate cross-system communication, collaboration, and service delivery (Appleby et al., Citation2019; Hamilton et al., Citation2019; Passmore et al., Citation2018; Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021; Reid et al., Citation2020; Scott et al., Citation2019). Insufficient resources for staff and youth have also been reported, significantly impacting upon best practice care (Hamilton et al., Citation2019; Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021). To provide appropriate services and support for youth, neurodevelopmental disabilities such as FASD must first be recognized (Bower et al., Citation2018; McLachlan et al., Citation2020) and the role of support services clarified (Appleby et al., Citation2019).

The Australian National FASD Strategic Action Plan 2018–2028 has prioritized activities that can equip youth justice system staff with knowledge, skills and resources to ‘divert offenders identified with neurodevelopmental or cognitive impairments, including FASD, away from prisons and into programs and services’ (Commonwealth, Citation2018). Our prior research (Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021) which aimed to understand the support needs of the justice sector workforce in a regional Australian setting, found a workforce eager to develop FASD informed work practices. Staff reported that they needed access to better information and training, particularly where and how to direct youth and their families to diagnosis and support services for FASD – and for neurodevelopmental disabilities generally.

Working with local stakeholders, a localized Model of Care resource was developed to:

build capacity and understanding among staff working in the Justice sector of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure and how FASD may present in youth clients,

illustrate the journey for justice-involved youth with possible undiagnosed neurodevelopmental disabilities (including FASD), and

maximize the potential of local services to ensure that youth clients receive ‘the right care, at the right time, by the right team and in the right place’ (Agency for Clinical Innovation, Citation2013).

The MoC should be understood as one element in a broader push to divert young people with neurodevelopmental disabilities away from prisons and into programmes and services. This brief report describes the process undertaken to consolidate the function, form, and content of the resource and reports on initial perceptions of resource usability.

Methods

Community engagement

Project and research officers engaged service staff within the Youth Justice sector in an iterative process of resource development over a 9-month period. A reference group was established in late 2019 (Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021) who provided feedback at each stage of the development process. Reference group members (n = 7) worked across the Youth Justice setting and collectively had community, medical, education and legal expertise. For example, the group included a legal representative, psychologist, Children’s Court coordinator and caseworker. Consultation with reference group members occurred using face-to-face meetings, teleconferences, and email correspondence as required. In addition to these ongoing consultations, expert advice was sought from members of the Australian and New Zealand FASD Clinical Network to ensure comprehensive coverage and accuracy of information. Ethics approval for this project was obtained from the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/ET000078).

Process

Prior to the resource development process, the project and research officers presented the results of the formative work (literature review, local service mapping and interviews; see Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021) to the reference group. The development of a referral pathway resource, with supports and diagnostic services for young people in contact with the juvenile justice system suspected of having cognitive impairment (including FASD), was unanimously supported. The reference group was committed to enhancing the local justice sector’s (police, courts, youth justice agencies and affiliated welfare services) knowledge and understanding of FASD, and their capacity to provide coordinated care across appropriate community-based services for youth clients.

Five phases of iterative resource development occurred between November 2019 and July 2020. The first three iterations covered the function, form, and content of the resource while iterations 4 and 5 mainly pertained to resource usability (see ). For Iterations 1 through 4, meeting notes were made and all feedback was recorded in Excel. The recorded data detailed each phase by its Purpose (e.g. function), Questions, Feedback received, and How feedback was obtained (e.g. in person or via email). Examples of specific questions asked to stakeholders at each phase are described in .

Table 1. Examples of questions asked to stakeholder specified per iteration.

For Iteration 5, the final MoC resource was distributed to 133 people from workforce organizations involved with Youth Justice, including the following sectors; Education (n = 13), Health (n = 36), Justice (n = 21), Youth (n = 21), Family Services (n = 6), Aboriginal Services (n = 4), Out of Home Care (n = 14), Alcohol and Other Drugs (n = 15) and Other (n = 3). All contacts were invited to participate in an online survey to provide feedback on the usability of the resource. The survey presented a case scenario to workforce participants, which described a young boy ‘Mitchell’ and his involvement with Youth Justice. Respondents were asked to comment on the case scenario survey questions using the MoC resource and ultimately describe the supports they would use to assist Mitchell. Survey items aimed to assess respondents’ perceptions of (a) the relevance of the resource, (b) the ability of the resource to assist the workforce with best practice provision of support to youth clients with suspected neurodevelopmental disabilities, and (c) intentions to use the resource in the future (see , Iteration 5).

Results

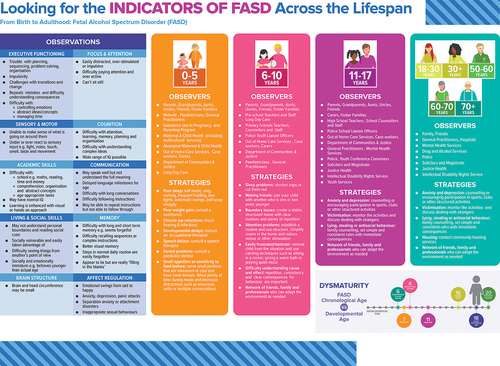

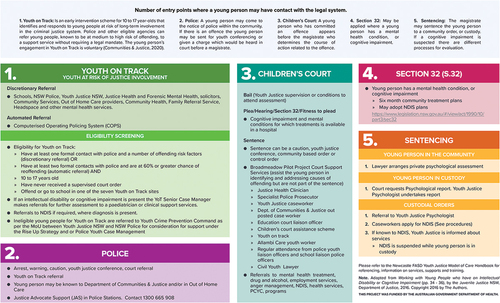

The first draft of the resource (Iteration 1) consisted of mapping out referral pathway schematics, which were identified as a mechanism to assist the workforce in providing youth and families with the most appropriate support available in the region (Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021). The reference group reviewed these materials and advised the team to simplify the visual design of the referral pathway schematic. In addition, the reference group highlighted a need for a support service directory and information about how FASD might present in terms of behaviour. In response to this feedback, additional poster style resources were included. The first described signs of FASD across the lifespan, including strategies that key observers could use to address FASD at each life stage (Additional file 1 - ePoster – Indicators of FASD). The second outlined the developmental domains where unique difficulties may be experienced and common indicative assessments (see p.12 (Dudley et al., Citation2015). Key diagnosis points from the Australian Guide to the diagnosis of FASD (Bower et al., Citation2017) were also included.

During Iteration 2, materials were again reviewed by the reference group who commented positively on the content but noted that a user manual was needed to guide users through the resource. Once the user manual was developed and the entire resource simplified to reflect this addition, it was sent for review to the Australian and New Zealand FASD Clinical Network. This network includes clinicians and researchers across both countries who are interested in improving outcomes for individuals with FASD. The group has extensive expertise and experience in FASD referral, assessment, diagnosis, and intervention. A review by this network was carried out to ensure the information was accurate and conformed to Australian guidelines and standards. Following review by four Australian members of the network (Iteration 3), minor changes were made to content, mostly regarding the language used, and the design was simplified again. All materials were then sent to nine additional Youth Justice stakeholders in the region (Iteration 4). At this stage, three of the nine stakeholders provided specific feedback regarding visual appeal and perceived ease of use. Their feedback allowed the team to reduce the amount of materials by integrating some of the content into the user manual. Minor grammatical changes were also made and the final version of the resource was sent to a graphic designer for completion. The final referral pathway schematic is presented in . The full Model of Care resource can be accessed via Additional File 1.

A survey was developed by the project and research officers with the aim of assessing resource usability in the local service area. One hundred thirty-three people from workforce organizations involved with Youth Justice were sent the resource and invited to participate in the survey. All participants who responded to the survey (n = 20) identified supports for the case scenario that was consistent with those recommended by the Model of Care resource, indicating relevance of information. Almost all respondents (90%) indicated that the Model of Care resource assisted their decision making in support of Mitchell, and that the resource was useful. The majority also intended to use the resource in the future (see ). Additional comments were provided, including that the resource should be more widely dispersed to assist health professionals and other workforce involved with the justice system. Additional comments included that the referral pathway schematic was helpful to prompt action for support, and that it would increase the skills of case workers and create better outcomes for clients. Two participants indicated the Model of Care resource did not help them with the case scenario because they did not perceive it as relevant to their role.

Table 2. Usability of model of care resource, n (%).

Respondents were also asked to provide comments on potential changes to the MoC resource. Fourteen participants (70%) said they would not make any changes. Six participants provided feedback regarding the visual presentation (e.g. ‘A decision tree model would be more helpful and easy to use,’ ‘perhaps make the resource less wordy’), and general comments on their ability to refer (e.g. ‘Would it be possible to include clear info on how a non-government health organization can facilitate/advocate for a referral to Youth on Track’).

Summary

The Model of Care resource was developed to respond to the capacity building needs of a regional workforce supporting justice-involved youth (Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021). Similar activities have been developed and implemented elsewhere (Bisgard et al., Citation2010; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2020). The referral pathway schematics are visual aids that assist staff to understand the pathways and options for a young person, who may have FASD or another neurodevelopmental disability, navigating the justice system. The pathway specifies several entry points where a young person may have contact with the legal system. The resource provides information and resources to: (a) help services and staff understand FASD across the lifespan and how it may present; (b) raise awareness in service providers (people who can act as observers) and alert clients and their families to the possibility of FASD; (c) provide strategies for working with people with FASD across the lifespan; and (d) incorporate the most appropriate information on FASD diagnosis processes. Furthermore, the resource could be used as a common tool to improve inter-agency communication in the region – a consistent issue highlighted in prior research (Pedruzzi et al., Citation2021). The information provided in the user manual on services, support and training available in the area could help close the gap in cross-system communication and service delivery, aiming to help provide more seamless support.

Although preliminary results from this study act as a pilot test supporting the relevance and suitability of the resource, the sample was small and may have been biased in favour of workers who had a greater interest in supporting youth with neurodevelopmental conditions. More research is needed to determine the broader use and impact of the resource. As more youth with neurodevelopmental disabilities, including FASD, enter the juvenile justice system, it is imperative that screening for these disorders is incorporated in juvenile justice systems (Allely, Citation2016; Bisgard et al., Citation2010). The MoC resource presents information on how neurodevelopmental disabilities, including FASD, can be better recognized, alongside information regarding the diagnostic and support services available in the region. The MoC resource, therefore, can assist staff to identify indicators of FASD and, at the same time, prompt them to seek out supports and programmes that will better support the needs of young people involved with the justice system. Especially, in the early stages of justice involvement, the challenges to prevention and diversion include misalignment between available programmes and misinformation on where to divert to, the MoC referral pathway schematics aim to facilitate early and appropriate intervention and support.

Limitations and future research

This project coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic which had significant implications for the methods employed in this work. The research team initially envisioned a series of face-to-face workshops with workforce professionals to assist in broader implementation and evaluation of the resource. The qualitative data from such workshops would have provided a richer context to determine next steps. However, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic including lockdowns at the time rendered these activities impossible.

Also, respondent numbers were small and must be interpreted with caution. Confounding factors such as general interest in the resource, most benefit from the resource, and time on hand may have affected the results. Further generalizability to other parts of Australia is not possible without additional work and more robust evaluation. To understand the effectiveness of the resource, future work must support implementation more broadly and consider the extent to which the resource: 1) assists the workforce in better recognition of FASD and other neurodevelopmental disabilities; 2) assists the workforce in each sector to provide appropriate referrals; 3) assists youth, families and carers in their therapeutic management journey; and 4) facilitates early intervention and support for individuals with FASD and other neurodevelopmental disabilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the seven reference group members, the members of the Australian and New Zealand FASD Clinical Network and the nine additional Youth Justice stakeholders in the region for their continued feedback and recommendations throughout this project. We would also like to acknowledge the graphic designer for the work on Model of Care materials.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, FVD, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agency for Clinical Innovation. (2013). A practical guide on how to develop a Model of Care at the Agency for Clinical Innovation.

- AIHW. (2018). National data on the health of justice-involved young people: A feasibility Study. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/4d24014b-dc78-4948-a9c4-6a80a91a3134/aihw-juv-125.pdf.aspx?inline=true.

- Allely, C. (2016). Studies investigating fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in the criminal justice system: A systematic PRISMA review. SOJ Psychology, 2(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.15226/2374-6874/3/1/00123

- Amnesty. (2015). A brighter tomorrow: Keeping Indigenous kids in the community and out of detention in Australia. Amnesty International Australia. https://www.amnesty.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/A_brighter_future_National_report.pdf

- Appleby, J., Shepherd, D., & Staniforth, D. (2019). Speaking the same language: Navigating information-sharing in the youth justice sphere. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 31(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol31iss1id537

- Baidawi, S., & Piquero, A. (2021). Neurodisability among children at the nexus of the child welfare and youth justice system. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(4), 803–819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01234-w

- Bisgard, E., Fisher, S., Adubato, S., & Louis, M. (2010). Screening, diagnosis, and intervention with juvenile offenders. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 38(4), 475–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/009318531003800406

- Bower, C., Elliott, E. J., Zimmet, M., Doorey, J., Wilkins, A., Russell, V., Shelton, D., Fitzpatrick, J., & Watkins, R. (2017). Australian guide to the diagnosis of foetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A summary. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 53(10), 1021–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13625

- Bower, C., Watkins, R. E., Mutch, R. C., Marriott, R., Freeman, J., Kippin, N. R., Safe, B., Pestell, C., Cheung, C. S. C., Shield, H., Tarratt, L., Springall, A., Taylor, J., Walker, N., Argiro, E., Leitao, S., Hamilton, S., Condon, C., Passmore, H. M., & Giglia, R. (2018). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: A prevalence study among young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia. British Medical Journal Open, 8(2), e019605. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019605

- Commonwealth. (2018). The National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) strategic action plan 2018–2028. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/national-fasd-strategic-action-plan-2018-2028.pdf

- Dudley, A., Reibel, T., Bower, C., & Fitzpatrick, J. (2015). Critical review of the literature: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Telethon Kids Institute. https://www.fasdhub.org.au/siteassets/pdfs/critical-review-of-the-literature-fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorders-14jun2016.pdf

- Fitzpatrick, J., Dudley, A., Pedruzzi, R. A., Councillor, J., Bruce, K., & Walker, R. (2020). Development of a referral pathway framework for foetal alcohol spectrum disorder in the Pilbara. Rural and Remote Health, 20(2), 5503. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5503

- Haight, W., Bidwell, L., Seok Choi, W., & Minhae, C. (2016). An evaluation of the Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM): Recidivism outcomes for maltreated youth involved in the juvenile justice system. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.025

- Hamilton, S., Reibel, T., Watkins, R., Mutch, R., Kippin, N., Freeman, J., Passmore, H., Safe, B., O’Donnell, M., & Bower, C. (2019). ‘He has problems; He is not the problem.’ A qualitative study of non-custodial staff providing services for young offenders assessed for foetal alcohol spectrum disorder in an Australian youth detention centre. Youth Justice, 19(2), 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225419869839

- Hand, L., Pickering, M., Kedge, S., & McCann, C. (2015). Oral language and communication factors to consider when supporting people with FASD involved with the legal system. In M. Nelson & M. Trussler (Eds.), Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in adults: Ethical and legal perspectives (pp. 139–147). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20866-4_9

- Haysom, L., Indig, D., Moore, E., & Gaskin, C. (2014). Intellectual disability in young people in custody in New South Wales, Australia - prevalence and markers. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 58(11), 1004–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12109

- Jonson-Reid, M., Dunnigan, A., & Ryan, J. (2018). Foster care and juvenile justice systems. In E. Trejos-Castillo & N. Trevino-Schafer (Eds.), Handbook of foster youth (1st ed. pp. 523–541). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351168243

- Kippin, N. R., Leitao, S., Watkins, R., Finlay-Jones, A., Condon, C., Marriott, R., Mutch, R. C., & Bower, C. (2018). Language diversity, language disorder, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder among youth sentenced to detention in Western Australia. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 61, 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.09.004

- McLachlan, K. (2017). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in Yukon Corrections. Yukon Department of Justice, Justice Canada.

- McLachlan, K., McNeil, A., Pei, J., Brain, U., Andrew, G., & Oberlander, T. F. (2019). Prevalence and characteristics of adults with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in corrections: A Canadian case ascertainment study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6292-x

- McLachlan, K., Mullally, K., Ritter, C., Mela, M., & Pei, J. (2020). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and neurodevelopmental disorders: An international practice survey of forensic mental health clinicians. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 20(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2020.1852342

- Passmore, H. M., Mutch, R. C., Burns, S., Watkins, R., Carapetis, J., Hall, G., & Bower, C. (2018). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD): Knowledge, attitudes, experiences and practices of the Western Australian youth custodial workforce. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 59, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.05.008

- Pedruzzi, R. A., Hamilton, O., Hodgson, H. H. A., Connor, E., Johnson, E., & Fitzpatrick, J. (2021). Navigating complexity to support justice-involved youth with FASD and other neurodevelopmental disabilities: Needs and challenges of a regional workforce. Health & Justice, 9(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-021-00132-y

- Perry, V., & Newbigin, C. (2017). 2015 Young people in custody health survey: Full report. https://www.justicehealth.nsw.gov.au/publications/2015YPICHSReportwebreadyversion.PDF

- Reid, N., Kippin, N., Passmore, H., & Finlay-Jones, A. (2020). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: The importance of assessment, diagnosis and support in the Australian justice context. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 27(2), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1719375

- Scott, C. K., Dennis, M. L., Grella, C. E., Funk, R. R., & Lurigio, A. J. (2019). Juvenile justice systems of care: Results of a national survey of community supervision agencies and behavioral health providers on services provision and cross-system interactions. Health & Justice, 7(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-019-0093-x

- Shaw, J. (2016). Policy, practice and perceptions: Exploring the criminalisation of children’s home residents in England. Youth Justice, 16(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225415617858

- Stade, B. C., Stevens, B., Ungar, W. J., Beyene, J., & Koren, G. (2006). Health-related quality of life of Canadian children and youth prenatally exposed to alcohol. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-81