ABSTRACT

The present study aims to determine the effects of an intervention that analyzes the effectiveness of a serious game (video-game with educational objectives) designed to reduce stigma towards people with mental-health problems. This video-game was applied both separately and in combination with other traditional-tools, such as a talk with a professional and face-to-face contact with persons with lived experiences of mental health conditions in a design with three experimental groups, where the different interventions were incorporated consecutively and a control group, where only participants without intervention were assessed. The Questionnaire on Students Attitudes towards Schizophrenia was used to assess stigma. The results obtained reveal the utility of the serious-game, producing a statistically significant reduction of stigma, and also the importance of combining it with other elements, such as contact with persons with lived experiences of mental health conditions. The talk by a professional produced no improvements in the intervention. The relevance of these results is discussed.

Introduction

At present, stigma related to mental health disorders is one of the main obstacles impeding the recovery and social integration of people who suffer from such problems Lin and Tsang (Citation2020); Thornicroft et al. (Citation2022). In efforts to combat this situation, various programmes have been implemented (Na et al., Citation2022). As for the strategies utilized in these interventions, they traditionally feature three components: education, protest and contact, which are most often combined in different ways (Parcesepe & Cabassa, Citation2013; Thornicroft et al., Citation2016).

One of the most common methods is educating and raising awareness through information campaigns, which may include talks given by professionals, aimed at the general public or specific groups, videos, guides, educational materials, activities and comics, workshops and other media (Saporito et al., Citation2011).

The type of information presented is a crucial aspect of this strategy. It is more important to focus on the suffering and adversities faced by this population than on any supposed biological aetiology (Longdon & Read, Citation2017).

As for activities within the realm of protest, such interventions mobilize groups and promote social activism to draw attention to the injustice associated with stigmatizing processes. For example, the activities organized around World Mental Health Day could be included in this category, as well as others that bring the problems of stigma into the spotlight, such as radio and television programmes that support the cause for the rights of those affected (Frías et al., Citation2018; Corrigan et al., Citation2012)

Finally, face-to-face contact with individuals suffering from mental health conditions represents one of the most effective intervention tools. It has been observed that most people who meet members of this alienated group prove less susceptible to the stereotypes associated with the latter. Under specific conditions, face-to-face contact becomes a strong predictive factor in change towards less stigmatizing attitudes, a trend found among adults and young people (Collins et al., Citation2013; Dalky, Citation2012).

The literature features countless studies detailing the various key conditions necessary to optimize the effects of face-to-face contact. For example, Pettigrew & Tropp (Citation2008) highlight that the effects of contact are amplified when carried out with an individual who is slightly removed from the group stereotype, when the session is longer in duration, when conducted within a framework of cooperative activities and when the participants or groups are from similar backgrounds and in a variety of situations. As for another work, Corrigan (Citation2005) cites four factors as guarantees of a positive effect: 1. Contact is focused on target groups; 2. Conduct at a local level; 3. Maintain contact over time; 4. Contact person must have credibility for the target group.

A key target population for stigma reduction is adolescents. This group is chosen both for demonstrating stigmatizing ideas similar to those of the general population and for being more malleable than adults, as their beliefs are not as engrained, thus making them more permeable to change (Ma et al., Citation2023). Programmes to reduce stigma with adolescents include strategies such as social contact; video-based education; conference; text reading; famous movies or role play, among others (Núñez et al., Citation2021) and, more recently, the use of new technologies (Rodríguez et al., Citation2022). For example, the game called Stigma-Stop has been compared with a wait list control group and with other interventions, such as a talk by a professional and face-to-face contact with persons with lived experiences of mental health conditions, and has demonstrated its efficacy in reducing stigma among secondary school and baccalaureate students, and university students, compared also with a control group carrying out a non-mental health task. The changes were statistically significant particularly in the Fear dimension (Cangas et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Mullor et al., Citation2019).

Nonetheless, this serious game has yet to be applied in a combined approach, that is, including different strategies as part of a programme that allows observing the effects of both the combined and isolated interventions. This approach was precisely the objective of the present study – analyse the benefits of Stigma-Stop as applied both separately and in conjunction with traditional interventions, such as a talk by a professional and face-to-face contact with persons with lived experiences of mental health conditions, to determine its potential impact.

Materials and methods

Participants

The sample was selected using intentional non-probability sampling, i.e. convenience sampling, and included a total of 556 participants from 6 randomly chosen schools in the province of Leon and Zamora (Spain). The age of the participants ranged between 14 and 19 (M = 16.69; SD = 3.81). As for distribution by gender, 298 were female and the remaining 256 were male. Experimental Group 1 included 136 participants, Group 2 included 278, Group 3 included 73 and the Control Group included 69. There were no significant differences in terms of gender or age among the groups (p > .05). The participants received no incentives for taking part in the study.

The present study obtained the approval of the Bioethics Committee of the University of XXX (REF 03/2020).

Instruments

Students Attitudes towards Schizophrenia

The Spanish version of the Questionnaire on Students Attitudes towards Schizophrenia (QSAS; Schulze et al., Citation2003) was used (Navarro et al., Citation2017). It consists of 19 items, with three response alternatives: I agree, I disagree and I am not sure. The questionnaire is composed of two factors: stereotypes and fear/aggressiveness. In the present study, the questionnaire obtained an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 and a McDonald’s Omega of 0.80.

Since the study involved children under 16 years of age, a Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) was performed to analyse the factor structure of the scale. For the CFA, the postulates of Hu & Bentler (see, Citation1999) and the fit indices of Hair Jr, Howard, & Nitzl (see, Citation2020) were considered. The scale fit indices were satisfactory: χ2 = 276.49 p < .001; df = 118; CFI = .96; NFI = .96; RMSEA = .059 (90% CI = .051–.064); SRMR = .041.

Stigma-Stop

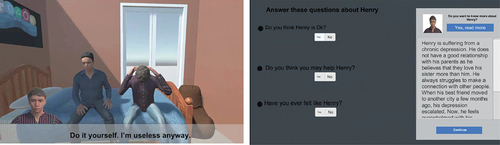

It is a Serious Game in which the player must interact with four characters related to mental disorders (depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and agoraphobia). The dynamics of the game is that the player is presented with a series of tasks, being necessary to interact with each of the characters in the game that manifest symptoms related to their respective disorder. In addition, the game offers feedback to players, providing information about emotional states or asking them if they have felt the same way as the characters, and even if they think they could help them. The video game provides information about the different characters and asks questions to the player (a screenshot is shown in ). Once interaction with each character has concluded mini-game is presented (i.e. memory, trivia, race, and shooting) whose content revolves around the topic of mental health. The game was projected on a multimedia screen and students voluntarily came forward to play, whereas the remaining students observed from their seats how the action evolved. The decision to play as a group in a classroom, as opposed to individually in a computer room, was made so that the three interventions featured a similar group format, thereby impeding the application format from creating an additional variable that could affect the results. For more information on this programme see Cangas et al. (Citation2017).

Design

To study the effect of the video game and the result of adding new elements, such as a talk by a professional and contact with a person with lived experiences of mental health conditions, three experimental groups were formed and a control group. The first group received only Stigma-Stop; in the second group a talk by a professional was added and in the third group all three elements were introduced. After the intervention, follow-up was carried out, with one or several sessions depending on the intervention received. The control group was only evaluated but without any intervention ( shows the intervention design).

Table 1. Session in the experimental groups and the control group.

Procedure

Firstly, authorization to conduct the study was obtained from the Department of Education Innovation and Equality of the Ministry of Education of Castile and Leon. Next, eight schools in the region were randomly contacted, six of them were public and two private; six of them were in cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants and two were in towns with less than 5,000 inhabitants. Of these, six agreed to participate in the project, five were public schools and one private; five were in towns with more than 100,000 inhabitants and one with less than 5,000 inhabitants.

An appointment was then made with the administration or counsellor of each school to personally explain the project, its purpose and objectives, as well as to discuss the number of sessions, the professionals participating and the possible benefits for the students. Once collaboration had been agreed upon, the school administration planned the dates and times of the sessions according to the availability of the students, the research group itself, and the personnel involved in conducting the project. Before carrying out the study, informed consent was requested from the students, or from their guardians if they were minors. Students were excluded from the sample if they refused to give their informed consent to participate.

During the intervention with Stigma-Stop, four volunteers came forward to play the game and interact with the characters in the serious game while the rest of the students followed the progress on a large screen connected to the computer. This same procedure was used in previous studies (Cangas et al., Citation2017; Mullor et al., Citation2019).

The intervention consisting of a talk given by a professional featured the participation of an individual with more than five years’ experience. This speaker discussed the need to normalize mental disorders and provide support to people with these pathologies, as well as how different substances can increase the probability of developing a mental illness. The talk focused mainly on schizophrenia as the most characteristic serious disorder of this period. The talk encouraged student participation and included with a Q&A period.

As for the intervention with a person with lived experiences of mental health conditions, the participant was of a 28-year-old woman, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia 17 years earlier. This person discussed their personal experience and limitations in their life and how, through therapy, they were able to lead a more conventional life and also obtain a job.

Data analysis

To analyse the existence of statistically significant differences between the different measures between the three experimental groups and the control group, a MANOVA was performed, complemented by the effect size, with its corresponding statistic, e-squared, and by Bonferroni’s Post Hoc tests. We used multivariate MANOVA analysis because we wanted to compare the different dependent variables (fear, stereotypes and QSAS total score) together with the independent variables (the different sessions) as a whole. Finally, a MANOVA was performed to evaluate the influence of gender on the results of the intervention (all analyses were performed with SPSS V.26.0).

Results

As can be seen in , the test of mean differences between the pre-test or baseline measurements of the experimental groups and the control group revealed no statistically significant differences between them in relation to the baseline variables analysed. However, statistically significant differences were found between the groups for all variables assessed at follow-up 1, 3 and 4. At follow-up 2, differences were only found in the fear factor and in the total score. Using Eta squared (η2), it was confirmed that the differences between the groups after the different interventions were moderate or even large in fear/danger and total score, and low in stereotypes. Through the post hoc tests, the differences between the different groups can be seen in .

Table 2. Manova for differences between experimental groups 1, 2 and 3 and the control group.

All the analyses were carried out using SPSS V.26.0. The statistical differences obtained for each group are presented in the following table. It can be observed in Experimental Group 1 that, following the pre-test (baseline) measurement, there were significant changes in the Fear factor when the serious game was introduced, which continued in the three follow-up sessions and even decreased further. The Stereotypes factor decreased but not significantly. The post hoc tests revealed the differences between the various interventions, as displayed in .

Table 3. Manova experimental group 1 - differences between the various sessions.

The interventions in Experimental Group 2 included the baseline session and serious game, as in Group 1, but also featured a talk by a professional and two follow-up sessions. It is observed that the same results were repeated as for Group 1 (the serious game achieved a statistically significant decrease in the Fear factor) and a slight reduction was achieved with the talk, albeit not statistically significant. The results for Stereotypes somewhat worsened, above all following the talk by a professional. The post hoc tests revealed the differences between the various interventions, as displayed in .

Table 4. Manova experimental group 2 - differences between the various sessions.

The same interventions were conducted with Experimental Group 3 as with the previous two, but with the addition of face-to-face contact with an individual diagnosed with schizophrenia. The results of the serious game and talk by a professional obtained similar results to the other groups, but when the talk by a person with lived experiences of mental health conditions was introduced, stigma dropped significantly for both the Fear and Stereotypes dimensions. This difference is considerable bearing in the mind the size of the effect. The post hoc tests revealed the differences between the various interventions, as can be seen in .

Table 5. Manova experimental group 3 – differences between various sessions.

Finally, no statistically significant differences were observed in the Control Group with regard to any variables, nor between any of the sessions, as can be seen in .

Table 6. Manova control group – differences between the various sessions.

In addition, a multivariant analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of gender on the benefits of the intervention. The MANOVA and inferential statistics analysis led to the conclusion that there were no statistically significant differences due to sex [p = .086, F(2,000) = 2.466, Lambda de Wilks = .991; η2 = .009]. It could thus be inferred that the effect of the programme was the same for all participants, independently of student gender.

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to verify the benefits of the serious game Stigma-Stop – designed to raise awareness and reduce stigma in mental health – both separately and in conjunction with other traditional strategies, such as a talk given by a professional and face-to-face contact with a person with lived experiences of mental health conditions.

On one hand, it is important to highlight that Stigma-Stop consistently proved effective in reducing the Fear/Dangerousness factor. These results were repeated in the three experimental groups and would be in line with previous studies (Cangas et al., Citation2017; Mullor et al., Citation2019). The Fear dimension has been found to be the most strongly associated with schizophrenia (Quiles et al., Citation2008). Stigma-Stop specifically dispels this notion by showing a standardized image of these individuals, for whom the disorder is simply a response to multiple hardships and adversities that can occur in life. The video game emphasizes the contextual aspects of each person that lead to the development of these pathological manifestations, thereby favouring empathy.

On the other hand, albeit the Stereotypes factor was reduced following the application of the video game, the effect was not statistically significant. This variable only changed significantly when face-to-face contact was added to the video game and talk by a professional. This fact indicates that to change this variable probably requires more intervention time or the inclusion of variables that the literature continues to show to be the most effective measure, such as face-to-face contact (Collins et al., Citation2013; Dalky, Citation2012). Incorporating first-hand life experiences provokes a radical shift in perception, as the illness ceases to be viewed as an abstract entity that is difficult to understand and becomes a specific story about a person in the present, positively influencing standardization. Also, in order to maximize the effects of these interactions, it is best they transpire as naturally as possible (Rusch et al., Citation2008).

On the other hand, the study also revealed, upon application of the strategy involving a talk by a professional, that stigma is not significantly improved, and it even increases (albeit not significantly) in the Stereotypes dimension. These results were repeated in Experimental Groups 2 and 3 and would have to be understood in relation to other studies that highlight the information provided as the key aspect. In this regard, it appears that a biomedical model, in which ‘the mental illness is an illness like any other’, generates ‘pessimism’ towards the possibility of recovery, revealing the various idiographic and contextual characteristics and, ultimately, increasing social distance (Longdon & Read, Citation2017). This essentially generates the impression that these individuals belong to a categorically different group, accentuating the intergroupal difference of ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ (Read et al., Citation2006). Attaching a biological aetiology to the disorder may reinforce beliefs about the chronic nature of these problems and attitudes of paternalism, which would ultimately lead to low motivation and adherence to treatment, relegating the person to merely a passive role (Pescosolido et al., Citation2010). In contrast, providing explanations based more on biographical variables, related to suffering and life problems which, to a greater or lesser extent, affect us all, can decrease the perception of differences while also fostering empathy and understanding, simultaneously facilitating the work of therapy providers. In our case, the professional that gave the talk from a biologistic approach, emphasizing the role of biological and cerebral alternations on the genesis and aetiology of these disorders, which might explain the results.

Among the limitations of the study, it is worth noting that the order of the interventions was not counterbalanced, which may have affected the results. Similarly, Stigma-Stop includes four disorders, while the talk and face-to-face contact focused on the case of schizophrenia. Thus, although there may be a continuity in the development of psychological disorders (Loranger et al., Citation2020) it would be important to delimit future studies to see how this fact may influence the results. Similarly, the questionnaire used is focused on stigma towards people with schizophrenia, it would be useful to apply in future studies other instruments that incorporate measures of stigma towards more psychological disorders. Also, it would be important to collect more characteristics of the sample that may also influence (e.g. socioeconomic status, presence or not in their family of people with mental health problems, etc).

Conclusions

The present study has demonstrated the utility of Stigma-Stop as an independent tool, as observed in previous studies (Cangas et al., Citation2017; Mullor et al., Citation2019), and as applied in conjunction with face-to-face contact with persons with lived experiences of mental health conditions. Thus, the serious game could be useful given its novelty and appeal to young people for the purpose introducing the topic, and to subsequently apply additional tools such as contact with persons with lived experiences of mental health conditions. In this sense, it can be a motivating strategy for young people, due to the relevance that video games have in the lives of young people, in this case with an educational purpose (Zayeni et al., Citation2020) and that can also be combined with other elements, such as contact with persons with lived experiences of mental health conditions, which has been shown to be the best strategy to reduce stigma (Thornicroft et al., Citation2022).

In fact, it has also been observed that when face-to-face contact is added, the results are maximal, not only fear towards mental disorders decreases, but also stereotypes. In this sense, the video game can be useful to implement massively in a quick, attractive and inexpensive way for young people, but then it is also important to anchor the changes through direct contact with people suffering from severe mental disorders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Cangas, A. J., Navarro, N., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Trigueros, R., Gallego, J., Zárate, R., & Gregg, M. (2019). Analysis of the usefulness of a serious game to raise awareness about mental health problems in a sample of high school and university students: Relationship with familiarity and time spent playing video games. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(10), 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101504

- Cangas, A. J., Navarro, N., Parra, J., Ojeda, J. J., Cangas, D., Piedra, J. A., & Gallego, J. (2017). Stigma-stop: A serious game against the stigma toward mental health in educational settings. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1385. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01385

- Collins, R. L., Wong, E. C., Cerully, J. L., Schultz, D., & Eberhart, N. K. (2013). Interventions to reduce mental health stigma and discrimination: A literature review to guide evaluation of California’s mental health prevention and early intervention initiative. Rand Health Quarterly, 2(4), 541–10.

- Corrigan, P. W. (Ed.). (2005). On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change. American Psychological Association.

- Corrigan, P. W., Morris, S. B., Michaels, P. J., Rafacz, J. D., & Rüsch, N. (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services, 63(10), 963–973. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100529

- Dalky, H. F. (2012). Mental illness stigma reduction interventions: Review of intervention trials. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 34(4), 520–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945911400638

- FríFríAs, V. M., Fortuny, J. R., Guzmán, S., Santamaría, P., Martínez, M., & Pérez, V. (2018). Stigma: The relevance of social contact in mental disorder. Enfermería Clínica (English Edition), 28(2), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcle.2017.05.004

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Lin, C. Y., & Tsang, H. W. (2020). Stigma, health and well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207615

- Longdon, E., & Read, J. (2017). ‘People with problems, not patients with illnesses’: Using psychosocial frameworks to reduce the stigma of psychosis. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 54(1), 24–30.

- Loranger, C., Bamvita, J. M., & Fleury, M. J. (2020). Typology of patients with mental health disorders and perceived continuity of care. Journal of Mental Health, 29(3), 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1581329

- Ma, K. K. Y., Anderson, J. K., & Burn, A. M. (2023). School‐based interventions to improve mental health literacy and reduce mental health stigma–A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 28(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12543

- Mullor, D., Sayans-Jiménez, P., Cangas, A. J., & Navarro, N. (2019). Effect of a serious game (stigma-stop) on reducing stigma among psychology students: A controlled study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(3), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0172

- Na, J. J., Park, J. L., LKhagva, T., & Mikami, A. Y. (2022). The efficacy of interventions on cognitive, behavioral, and affective public stigma around mental illness: A systematic meta-analytic review. Stigma and Health, 7(2), 127. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000372

- Navarro, N., Cangas, A. J., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Gallego, J., Moreno-San Pedro, E., Carrasco-Rodríguez, Y., & Fuentes-Méndez, C. (2017). Propiedades psicométricas de la versión en castellano del Cuestionario de las Actitudes de los Estudiantes hacia la Esquizofrenia. Psychology, Society, & Education, 9(2), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.25115/psye.v9i2.865

- Núñez, D., Martínez, P., Borghero, F., Campos, S., & Martínez, V. (2021). Interventions to reduce stigma towards mental disorders in young people: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal Open, 11(11), e045726. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045726

- Parcesepe, A. M., & Cabassa, L. J. (2013). Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: A systematic literature review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(5), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0430-z

- Pescosolido, B. A., Martin, J. K., Long, J. S., Medina, T. R., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2010). “A disease like any other”? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(11), 1321–1330. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121743

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta‐analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(6), 922–934.

- Quiles, M. N., & Morera, M. D. (2008). El estigma social: la diferencia que nos hace inferiores. In J. F. Morales, C. Huici, E. Gaviria, & A. Gómez (Coords.) (Eds.), En Método, teoría e investigación en psicología social. Dykinson.

- Read, J., Mosher, L. R., & Bentall, R. P. (2006). La “esquizofrenia” no es una es una enfermedad. In J. Read, L. R. Mosher, & R. P. Bentall (Eds.), Modelos de locura (pp. 3–9). Herder.

- Rodríguez, M. E., Cangas, A. J., Cariola, L. A., Varela, J., & Valdebenito, S. (2022). Innovative technology-based interventions to reduce stigma toward people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Serious Games, 10(2), e35099. https://doi.org/10.2196/35099

- Rusch, L. C., Kanter, J. W., Angelone, A. F., & Ridley, R. C. (2008). The impact of in our own voice on stigma. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 11(4), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487760802397660

- Saporito, J. M., Ryan, C., & Teachman, B. A. (2011). Reducing stigma toward seeking mental health treatment among adolescents. Stigma Research and Action, 1(2), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.5463/sra.v1i2.26

- Schulze, B., Richter‐Werling, M., Matschinger, H., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2003). Crazy? So what! Effects of a school project on students’ attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 107(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02444.x

- Thornicroft, G., Mehta, N., Clement, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Doherty, M., Rose, D., & Henderson, C. (2016). Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. The Lancet, 387(10023), 1123–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00298-6

- Thornicroft, G., Sunkel, C., Aliev, A. A., Baker, S., Brohan, E., El Chammay, R., Davies, K., Demissie, M., Duncan, J., Fekadu, W., Gronholm, P. C., Guerrero, Z., Gurung, D., Habtamu, K., Hanlon, C., Heim, E., Henderson, C., Hijazi, Z., Hoffman, C., Votruba, N., & Winkler, P. (2022). The lancet commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. The Lancet, 400(10361), 1438–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01470-2

- Zayeni, D., Raynaud, J. P., & Revet, A. (2020). Therapeutic and preventive use of video games in child and adolescent psychiatry: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 36. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00036