ABSTRACT

This study investigated the contributory roles of personality traits and social intelligence in the self-regulation abilities among sampled 466 university students. Using a standardized instrument, data was collected from 466 participants and analysed with Structural Equation Modeling. The findings revealed that the self-regulation abilities of university students were moderately low. Agreeableness (β = .367, t = 8.299; p < 0.05), neuroticism (β = .350, t = 9.737; p < 0.05), openness (β = .235, t = 6.221; p < 0.05), and extraversion (β = .130, t = 2.854; p < 0.05) significantly predicted self-regulation, with agreeableness having the strongest influence. Conscientiousness, however, had a negative impact, while social intelligence showed little effect. The findings suggest that developing social intelligence is crucial to improving self-regulation abilities, complementing the positive influence of personality traits like agreeableness, openness, and extraversion. Therefore, enhancing social intelligence among university students is essential for promoting effective self-regulation.

Background

Societal development depends largely on the educational capability of its citizens. A university education is the highest learning pyramid and a platform for administrative, cultural, economic, social and technology empowerment. Basically, society advances through continuous interest and investment in the development of its young people through the instrumentality of quality education. This helps them to become self-directed, self-discovering, independent, meaningful contributors to society, and ready for a professional pathway. Hence, self-regulation of young people is pivotal for the achievement of educational and personal goals. Self-regulation, the ability to identify and correct one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviours logically and deductively, is widely acknowledged as essential for individuals to learn, become better citizens, and participate consciously in the decision-making process in society.

Essentially, self-regulation ability enables an individual to acquire the requisite knowledge, perform highly cognitive tasks including highly academic tasks, make appropriate and timely decisions, and demonstrate social abilities (Hashem, Citation2021). Interestingly, McCabe and Brooks‐Gunn (Citation2007) allude that self-regulation is a process that begins at an early age and develops throughout life. Individuals who possess high self-regulation ability are likely to be self-reliant, self-motivated, and capable of solving problems in an appropriate manner that guarantees quality of life and life-long achievement. Lack of self-regulation may not only hamper the achievement of education but also lead to poor academic performance due to procrastination, low motivation, low quality of life, dissatisfaction with life, as well as underdevelopment of society (Al Rab’a & Mukablah, Citation2019; Rakes & Dunn, Citation2010).

As a psychological resource, self-regulation controls human behaviour and the inner state towards desired goals and operates against a backdrop of conflicting or distracting situations, drives and impulses (Diamond, Citation2013). Self-regulation encapsulates other constructs such as delay of gratification, effortful control, self-motivation, goal-orientation, self-evaluation, emotional-regulation, executive functioning, impulse control, temperament, and willpower (Blair & Raver, Citation2015; Malanchini et al., Citation2019; Nigg, Citation2017). Also, the antecedents of self-regulation positioned it as a vital contributor to one’s psychological wellbeing (Aadland et al., Citation2018; Hofer et al., Citation2011; Wang et al., Citation2022). Self-regulation ability is one of the positive psychological resources that make the achievement of personal goals possible (Balkis & Duru, Citation2016). Evidence has shown that university students who possess self-regulation ability are capable of dealing with difficult situations, eliminate procrastination, have reduced stress, and lower depression (Park et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2022; Zhao et al., Citation2021). However, not all students possess the same level of self-regulation ability, and though they perform various tasks that are both academic and social oriented, various factors influence this ability. Surprisingly, there is a significant omission in the literature on what contributes to the self-regulation of university students. This present study therefore examines the role played by social intelligence and personality traits in the self-regulation ability of university students.

Justification for the present study

The study is motivated by the imperative for university students to develop self-regulation abilities, essential for navigating the academic, personal, and professional challenges prevalent in today’s rapidly evolving world. In addition to fostering deep learning and knowledge retention, it is anticipated that self-regulation skills will instil lifelong learning habits, autonomy, resilience, critical thinking, and holistic development, all of which are vital for personal and professional advancement. Moreover, the transition to university often coincides with significant life adjustments, such as relocating from home, establishing new social connections, and confronting heightened academic demands. Throughout this transitional phase, students are confronted with various stressors that can adversely affect their mental well-being and academic performance. Despite the multitude of choices and temptations confronting many university students, self-regulation and its related factors (personality traits and social intelligence) has not received adequate attention. This is particularly noteworthy in countries like Kazakhstan, where a considerable portion of the youth population grapples with identity and emotional crises (Mambetalina et al., Citation2024), thus underscoring the importance and relevance of the study.

Theoretical framework

To accurately position this study, a theoretical perspective that best relates to the self-regulation of university students was carefully considered. Thus, the social cognitive theory proposed by Bandura (Citation1999) was chosen as the theoretical framework. This theory acknowledges individuals’ capacity to intentionally shape life events and circumstances, as well as select responses to actions (Bandura, Citation2001). It posits that individuals are active agents in their lives and environments, striving to control significant aspects by regulating their thoughts and actions to achieve personal goals (Sandars & Cleary, Citation2011). Social cognitive theory was selected for this study because it provides insight into the reciprocal interactions among different dimensions of self-regulation, integrating various hierarchical levels including cognitive, emotional, and behavioural aspects (Blair & Ku, Citation2022). These interconnected levels collectively contribute to the successful development of self-regulation skills. Consequently, individuals’ abilities to achieve and develop self-regulation vary due to unique characteristics such as personality and social intelligence (Schunk & Greene, Citation2018).

Furthermore, social cognitive theory emphasizes the role of observational learning, suggesting that individuals learn by observing others. This is corroborated by Payan-Carreira et al. (Citation2022), who affirm that self-regulation does not develop spontaneously but is nurtured and trained through the educational system. Similarly, social cognitive theory asserts that individuals’ belief in their ability to perform a particular behaviour, such as developing self-regulation, can be enhanced when students are made aware of their potential to do so, considering their personal traits such as personality and social intelligence. Therefore, university students’ self-regulation abilities could be positively influenced when factors such as personality and social intelligence are taken into account.

Related studies

Personalities traits

Personality traits are the second factor considered in this study to perhaps have a contributory role in the self-regulation ability of university students. Numerous scholars have made various interesting contributions to the understanding of personality, such as the Five-alternatives Model that lists activity, aggression – hostility, neuroticism – anxiety, sociability, and impulsive non-socialized sensation seeking as the manifestations of personality (Zuckerman et al., Citation1993); the Five-factor Model (McCrae & Costa, Citation1987); and recently the Six-factor HEXACO Model (Ashton et al., Citation2014). However, notable researchers including Bidjerano and Dai (Citation2007); Connor-Smith and Flachsbart (Citation2007); and Pollak et al. (Citation2020) allude that operationalization of the Big Five model positions it to be the most universal model of personality dimensions. This is basically because it orders and integrates other dimensions of personality traits including self-regulation propensities which are supported by cross-cultural research. Thus, the Broad/Big Five personality dimensions (agreeability, conscientiousness, extraversion, openness to experience and neuroticism) were adopted for the purpose of this current study.

McCrae and Costa (Citation2003) provide insight into the concept of each personality dimension and others describe the features of each trait. For instance, a person is described as agreeable when such a person is interpersonally oriented, has a good-natured disposition, and is forgiving, courteous, helpful, and altruistic. Highly agreeable individuals tend to be sensitive to others, trust them, and demonstrate willingness to cooperate, while less agreeable individuals may show lack of trust and competitiveness. Studies have demonstrated positive correlations between agreeability and job performance, as well as success in life (Matzler et al., Citation2011; Yesil & Sozbilir, Citation2013). Conscientiousness describes individuals as dependable, perfectionistic, responsible, organized, hardworking, and goal-oriented (Barrick & Mount, Citation1991). And a behaviour is a link with self-regulation, according to Malanchini et al. (Citation2019); and Nigg (Citation2017). It has been argued that highly conscientious individuals tend to perceive events as stressful, but instead of avoiding them, they take direct measures to manage and overcome any challenges that are associated with such events (Pollak et al., Citation2020; Włodarczyk & Obacz, Citation2013). Kumar and Bakhshi (Citation2010) emphasized that conscientious people are dutiful, self-disciplined, persistent, and have a strong sense of purpose and obligation. Matzler et al. (Citation2011) found a positive relationship between high conscientiousness and achievement.

Extraversion is another dimension of the Big Five personality traits proposed by McCrae and Costa (Citation1987; 2003). It encompasses traits such as being energetic, joyful, sociable, and self-confident. These traits indicate a person’s social functioning, level of activity, and ability to experience positive emotions. Deniz and Satici (Citation2017) found a positive association between extraversion and assertive behaviours, self-assurance, and seeking excitement. Openness to experience refers to cognitive curiosity and a person’s inclination to seek life experiences and intellectual growth. Bakker et al. (Citation2002) suggested that individuals high in openness to experience tend to be more flexible, imaginative, and intellectually curious when faced with stressful situations. Previous studies by Patterson et al. (Citation2009); and Yesil and Sozbilir (Citation2013) have shown that openness to experience is the only personality dimension positively correlated with individual creativity and innovative behaviour. Neuroticism is the final dimension of the Big Five personality traits, and this is characterized by traits such as aggression, anger, anxiety, emotional instability, irritability, and moodiness (Yesil & Sozbilir, Citation2013). People high in neuroticism are prone to experiencing negative emotions that persist over time. As a result, they tend to perceive life events as losses or threats and struggle to appreciate their own capabilities, making it difficult for them to cope with stress (Moreira & Canavarro, Citation2015; Pollak et al., Citation2020). Studies have consistently found negative associations between neuroticism, and lack of analytic or cognitive ability, critical thinking skills, and poor conceptual understanding, presumably because it tends to freeze higher-order cognitive functioning (Bidjerano & Dai, Citation2007; Moreira et al., 2015; Yesil & Sozbilir, Citation2013). Lower levels of neuroticism are linked to higher levels of positive well-being.

Numerous empirical studies have provided evidence supporting the predictive role of the five dimensions of personality in relation to self-regulation. These studies include Paauw’s study in (Citation2020) which revealed that conscientiousness and extraversion had positive associations with self-regulation, while neuroticism displayed a negative association. However, no significant associations were found between openness, agreeableness, and self-regulation (Paauw, Citation2020). In research conducted by Smith et al. (Citation2019), it was observed that conscientiousness is connected to self-regulation. Another study conducted by Judge and Ilies (Citation2002), which involved a meta-analysis, revealed a moderate correlation between conscientiousness and various elements of self-regulation, such as motivation. Other previous studies conducted by Briley and Tucker-Drob (Citation2014); Neuenschwander et al. (Citation2013); and Tucker-Drob et al. (Citation2016) have independently demonstrated that conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness consistently exhibit strong associations with various aspects of self-regulation. These aspects include goal achievement, performing well in academic tasks, and effective executive functioning.

Despite being characterized by traits such as altruism, kindness, empathy, compliance, group-orientation, and warmth, only a limited amount of research has explored the connection between agreeableness and self-regulation or any of its components (de la Fuente et al., Citation2020). In a related study conducted by Shiner and Caspi (Citation2003), it was discovered that agreeableness is positively linked to academic achievement, as kindness promotes cooperation in learning processes. The authors of the aforementioned research anticipate that students who demonstrate the ability to self-regulate should be capable of utilizing problem-focused approaches that involve cooperative studying or cooperative learning. On the other hand, extraversion is associated with individuals’ confidence in situations that require cognitive effort or present social challenges (de la Fuente et al., Citation2020; Matthews et al., Citation2000). Consequently, individuals with high levels of extraversion are more likely to display self-regulated behaviour (de la Fuente et al., Citation2020). However, the contributory role of personality dimensions to the self-regulation of university students has rarely been explored.

Social intelligence

Social intelligence (SI) is a construct that was originally proposed by Thorndike (Citation1920, as cited in Weis & Süß, Citation2007). It was defined as behaving wisely in human relationships. Over time, SI has gained popularity among scholars, and it has been conceptualized differently. For instance, Kihlstrom and Cantor (Citation2000) described it as a process of understanding other people’s behaviours and coping well with them, reflecting a depth of knowledge about the social world. Silvera et al. (Citation2001) and Carrera and Tononi (Citation2014) categorized SI into three dimensions: social awareness, social knowledge, and social skills. According to Hampel et al. (20011), SI interacts with social information through the processes of social memory, social perception, and social flexibility to reveal social behaviours. In the opinion of Goleman (Citation2014), SI enables individuals to organize, find solutions through discussion, establish personal connections, and make social analyses. This includes comprehending people and events, anticipating future occurrences, and steering events in the desired direction. Given these views, SI can be said to involve communication, empathy, and conflict resolution, making it an important factor for successful living, especially for university students. It helps them become more confident in their abilities, more resilient, and they develop a positive self-concept that enables them to pursue and achieve their goals and behave in a socially acceptable way (Abdul-Raouf & Issa, Citation2018; Zbihlejova & Birknerova, Citation2022).

Surprisingly, we noticed a narrow focus on social intelligence and self-regulation ability in the literature. Studies related to social intelligence concentrated exclusively on other factors such as the link between SI and the coping strategies of business managers (Zbihlejova & Birknerova, Citation2022); and the relationship between SI and organizational performance (Ebrahimpoor et al., Citation2013). Sethi and Sharma (Citation2023) investigated the correlation between SI and self-efficacy in information technology organization. Gulliford et al. (Citation2019) investigated the relationship between gratitude, SI and self-monitoring among the general population in the United Kingdom, while the commonalities and differences between SI, emotional intelligence, and practical intelligence were examined by Lievens and Chan (Citation2017). Loflin and Barry (Citation2016) revealed specific links between SI and interpersonal aggression. The outcome of their research indicated that SI was associated with higher levels of self-reported relational aggression in females. The direct impact of social intelligence and collective self-efficacy in hospital service providers in Egypt was examined by Mohamed (Citation2021). The study’s result revealed a positive significant association between SI and the service providers’ performance. It was concluded that SI competences provide the basis for collective self-efficacy and service providers’ performance for the physicians in the Egyptian government hospitals.

To our best knowledge, there is no empirical evidence that establishes the role of SI in the self-regulation of university students, apart from Hashem’s (Citation2021) study which centred on the relationship between self-regulation and SI among female college students in Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University in Egypt. The study revealed a high level of self-regulation and SI, and that SI not only correlated positively and significantly with self-regulation statistically but also predicted self-regulation. Similar research by Alkhutaba (Citation2022) determined the predictive role of SI and general self-efficacy on public speaking skills among 403 university students in Isra University and the University of Jordan. The finding detected a weak positive link between SI and public speaking ability. There is thus a gap in the literature and it is the intention of this study to bridge this gap.

Objective and research questions

The primary focus of this study is to assess the role of personality traits and social intelligence on self-regulation ability of university students. Specifically, the study aimed to address the following research questions:

RQ1:

What was the university students’ level of self-regulation ability?

RQ2:

Were there any significant relationships between the self-regulation ability of university students and its contributory factors (social intelligence and personality traits)?

RQ3:

Which factor contributed to the present level of self-regulation ability in university students?

Method

Participants

In order to accomplish the objective of this research, a quantitative research design of the correlational type was employed using survey approach for data collection. The participants in the study consisted of students from various universities in Astana, Kazakhstan. To assess the current level of self-regulation and its contributing factors, a Google form was utilized to collect data from 466 participants who completed an online survey that spanned one month. Existing instruments for each construct were adapted with some modifications and rephrasing to ensure cultural compatibility. The questionnaire comprised of two parts: the first section gathered information about the respondents’ demographic characteristics, while the second section contained the scale of the constructs.

Measures

All the instruments were standardized by carrying out a pilot test to ensure that the scale is suitable to be used within the Kazakhstan context and in order to establish its current psychometrics properties by the researchers. This was done by non-participant young people in colleges; after which the responses were coded and entered into SPSS version 26.0 and Cronbach Alpha estimate was used to generate the reliability values. The scale was translated from English language into Russian language, given the nature of the participants of the study. This was done for participants to understand the items very well.

Self-regulation

The Short Self-Regulation Questionnaire (SSRQ), originally developed in 1999 by Brown and his colleagues, underwent revisions by Carey et al. (Citation2004) and was utilized in this study. The SSRQ is a scale comprising of 31 items that aim to evaluate an individual’s overall self-regulation ability. It has been widely employed by various researchers (Hashem, Citation2021; Opelt & Schwinger, Citation2020; Šebeňa et al., Citation2018). The scale underwent revalidation in this study to confirm its reliability, resulting in a reported reliability value of 86.

Social intelligence scale (SIS)

Social intelligence was measured using the Tromsø Social Intelligence Scale (TSIS), developed by Silvera et al. (Citation2001). The scale consists of 21 items that cover 3 distinct aspects of social intelligence: social awareness, social skills, and social information processing. Each of the three factors of the scale comprises 7 items which are measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The initial version has good reliability with Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficients for information processing, social skills and social awareness at 0.81, 0.86 and 0.79 respectively.

Personality scale (PS)

The personality dimensions of the Big Five model were assessed in this study by adopting the NEO-PI-R developed by Costa and McCrae (Citation1992). A condensed version of the scale comprising 30 items was used to suit the needs of the study. This version included five direct items for each of the five personality factors: agreeability (Cronbach’s alpha = .69), conscientiousness (Cronbach’s alpha = .78), extraversion (Cronbach’s alpha = .69), openness to experience (Cronbach’s alpha = .40), and neuroticism (Cronbach’s alpha = .73). A condensed version of the scale comprising 30 items was used to suit the needs of the study.

Ethical approval

The authors adhered to international research ethics standards regarding human participants and followed the guidelines set by these standards. They sent an Informed Consent Form to the students in a Google Form format, requesting their consent. Upon agreeing to participate in the study by selecting ‘yes,’ participants were automatically directed to the questionnaire page. The participants were assured that the collected information would be used solely for research purposes and that confidentiality would be maintained. Furthermore, they were informed that there were no right or wrong answers and that their responses would reflect their perceived potential.

Data analysis

The data in the study was analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. A frequency count was conducted to analyse the demographic characteristics of the respondents and to determine their self-regulation levels, while inferential statistic of the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to test the direct predictive influence of the psychosocial-spiritual factors on well-being and to determine the predictive power of the factors on well-being when moderated general health condition. Thus, each factor was regressed onto to estimate the direct effects between different measures. IBM AMOS 26.0 was used as a tool to perform the pattern of correlation.

Result

Demographic data

The demographic information of the participants as follows. The gender results showed that 14.6% were males, and 85.4% were females. The age indicated that the majority of the participants were between 17 and 19 years of age (284, 61%), followed by those within 23–25 years (98, 21%). This was followed by those between 20 and 22 years of age (76, 16.3%), and participants above 25 years numbered 8 (1.7%). The parental socio-economic status (SES) of the participants was as follows: 10.8% perceived their parents as being of a high SES, the majority (87.5) were perceived as moderate, while only 1.7% of the participants adjudged their parents to be of a low SES. The parental marital status showed that 318 (68.2%) were from intact families or families where the parents lived together. This was followed by 114 (24.4%) whose parents were separated or divorced, while 7.4% of the participants had lost their parents. This means that the majority of the participants came from families where the parents lived together.

RQ1:

What was the university students’ level of self-regulation ability?

The findings, shown in , revealed that the university students’ level of self-regulation ability in response to the first research question was moderately low as 13 items rated above the average mean estimate of 3.66, and 18 items scored mean values below the average mean score. Item 13, Usually, I only need to make a mistake once in order to learn from it was ranked as the highest self-regulation ability (M = 4.27). This was followed by item 27, Often, I don’t notice my actions until someone brings them to my attention (M = 4.23). This was followed by item 26, If I make a resolution to change something, I closely monitor my progress (M = 4.09); while items 3, 21 and 22; I tend to procrastinate when it comes to making decisions; I establish goals for myself and track my progress; and Most of the time, I fail to pay attention to what I’m doing had the same score (M = 3.99). Item 11, I don’t seem to learn from my errors (M = 3.88) was next to items 3, 21 and 22, and these were followed by item 25, once I have a goal, I am generally capable of devising a plan to attain it (M = 3.87). Next was item 7; I find it challenging to determine when I’ve reached my limit (with alcohol, food, sweets) (M = 3.84). Item 29, I learn from my mistakes (M = 3.80) followed; and this was then followed by item 19, I face challenges in devising plans to help me achieve my goals (M = 3.70). Items 9 and 17, When it comes to making a change, I feel overwhelmed by the available choices, and I struggle with setting personal goals had the same score of 3.66. However, item 31, I tend to give up quickly had the lowest score (M = 2.77) which is indicative of low self-regulation ability. This was followed by item 10, I encounter difficulties in following through with tasks once I’ve made a decision (M = 3.22. Next were item 3, I easily get sidetracked from my plans (M = 3.24); item 24, When I wish to make a change, I can usually identify multiple options (M = 3.24); item 28, I usually think before taking action (M = 3.32); item 2, I struggle with decision-making (M = 3.39); item 20, I have the ability to resist temptation (M = 3.41); item 17, When attempting to change something, I pay close attention to my progress (M = 2.47); item 5, I possess the ability to achieve the goals I set for myself (M = 3.51); item 17, I possess strong willpower (M = 3.54); Item 4, I fail to recognize the consequences of my actions until it’s too late (M = 3.55); item 14, I have personal standards and strive to meet them (M = 3.56); items 12, 15 and 1, I can adhere to a well-functioning plan, Upon encountering a problem or challenge, I immediately begin searching for all possible solutions and I typically monitor my progress towards my objectives had equal score (M = 3.57). Items 8 and 30, If I desired to change, I have confidence in my ability to do so and I have a clear vision of the person I aspire to be both scored (M = 3.58); as did item 23, I tend to persist with the same approach, even when it’s ineffective.

Table 1. Simple percentages showing the responses of the participants to the self-regulation statements in descending order.

RQ 2:

The second question sought to determine if there were significant relationships between the self-regulation abilities of university students and the contributory factors of social intelligence and personality.

The results presented in show the Chi-square values for the proposed factors predicting self-regulation. The results reveal that the Chi-square value (X2 = 163.835) is greater than 0.05, indicating that the proposed factors are adequate and within the acceptable norm, thus sufficient to predict self-regulation in the study participants. Since the model fit is accepted, we further explored the relative fit indices to determine the robustness of the proposed factors: GFI = 0.955, NFI = 0.930, TLI = 0.927, and CFI = 0.933. However, the RMSEA value of 0.185 indicates a less-than-perfect model fit. Overall, the results suggest that social intelligence and personality traits are good predictors of self-regulation in university students. Based on the SEM criteria, most measurement models in this study demonstrate satisfactory fit indices for self-regulation.

Table 2. Structural equation modelling (SEM).

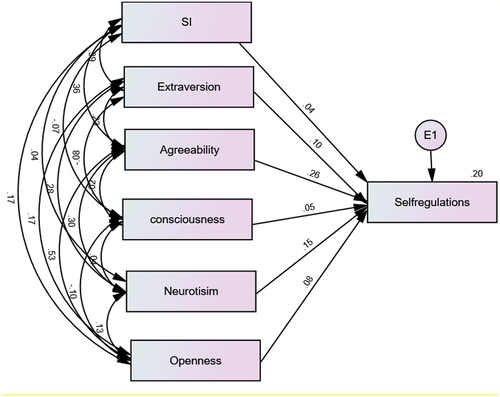

To determine the significance of the relationships, the path diagram and Maximum Likelihood estimation were performed to evaluate the SEM using AMOS 26.0 after the measurement model’s specification and this is presented in .

shows the significant relationships between university students’ self-regulation abilities and the contributing factors of social intelligence and personality traits. The path analysis revealed that social intelligence and personality traits correlated with self-regulation abilities, with the strongest association being with agreeableness (r = 0.26), followed by neuroticism (r = 0.15), extraversion (r = 0.10), conscientiousness (r = 0.05), and social intelligence (r = 0.04), in that order.

RQ 3:

Which factor played a contributory role to the present levels of self-regulation ability of the university students?

The findings presented in indicated that all of the factors considered in the study collectively contributed to the prediction of self-regulation abilities (R2 = .533, Adjusted R2 = .523; p < .01). This suggested that social intelligence and the Big Five personalities accounted for 52.3% of the observed changes in self-regulation abilities reported by the participants. The remaining 47.7% of the changes could be attributed to other factors that were not considered in this study. Furthermore, reveals that an agreeable personality had the highest positive contribution of 36.7% (β = .367, t = 8.299; p < 0.05) to the prediction of self-regulation abilities. Neuroticism followed closely with a contribution of 35% (β = .350, t = 9.737; p < 0.05); openness to experience contributed 23.5% (β = .235, t = 6.221; p < 0.05); and extraversion contributed 13.0% (β = .130, t = 2.854; p < 0.05). However, conscientiousness had a negative and significant contribution of −8.2% (β = −.082, t = −2.250; p < 0.05). On the other hand, social intelligence (SI) had a minimal contribution of 2.1% (β = .021, t = .638; p > 0.05) and did not significantly contribute to the self-regulation abilities of the university students.

Table 3. Regression and standardized weights model.

Discussion and conclusion

The findings of this study revealed that the participants exhibited a relatively low level of self-regulation ability. This suggests that there is a need to enhance the self-regulation skills of university students in Kazakhstan in order for them to achieve the educational objectives of becoming independent, self-directed, and self-aware individuals who contribute meaningfully to socio-economic development and are prepared for their future professional careers. The observed lack of self-motivation, self-reliance, and confidence in problem-solving abilities among a significant number of participants may contribute to this finding. Furthermore, it is possible that they engage in academic procrastination, which serves as an indication of limited or insufficient self-regulation abilities. These findings align with previous studies conducted by Al Rab’a and Mukablah (Citation2019), Wang et al. (Citation2022), and Zhao et al. (Citation2021), which also highlighted the negative impact of inadequate self-regulation on academic achievement, poor academic performance, procrastination, low motivation, diminished quality of life, dissatisfaction, and underdevelopment of society. In contrast, the findings contradict the claims made by Al-Youssef (Citation2020) and Hashem (Citation2021), who argued that university students possess a high level of self-regulation due to the requirements of university admission, which involve completing tasks within specified deadlines and unintentionally practicing self-regulation.

The results of the second research question revealed that all of the factors examined were related to a moderate level of self-regulation ability among the participants. This suggests that social intelligence and the Big Five personality dimensions are significantly associated with a moderately low level of self-regulation ability. It is interesting to note that even for personality traits such as neuroticism, which involve characteristics like anger, aggression, emotional instability, anxiety, irritability, perceived threats, and difficulties in coping with stress, there was a positive correlation. This finding further supports the idea of a moderate low level of self-regulation among the students. These findings align with previous research that has established a link between self-regulation and the Big Five personality dimensions. While there may be variations in the relationships between social intelligence, personality, and self-regulation abilities, as mentioned by Vedel and Poropat (Citation2017), our results correspond closely with established associations found in the literature and in previous studies involving university students.

The concern of the last research question was to determine the relative contribution of social intelligence (SI) and personality traits on the participants’ current level of self-regulation abilities. The results revealed that agreeable personality traits had the strongest impact on the students’ self-regulation abilities. This was closely followed by neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion. However, conscientiousness had a negative but significant contribution, while the contribution of social intelligence was not statistically significant. In other words, individuals who were agreeable, open to experience, and extraverted, with possibly lower levels of neuroticism, tended to have higher self-regulation abilities. This indicates that highly agreeable individuals are socially oriented, possess a kind and forgiving disposition, and demonstrate helpfulness, altruism, emotional sensitivity towards others, trust in others, and a willingness to cooperate (Matzler et al., Citation2011; Yesil & Sozbilir, Citation2013). Although the self-regulation abilities of the students in this study were found to be moderately low, a plausible explanation for this could be that most of the participants also had slightly low agreeableness. This finding contradicts a portion of Paauw’s (Citation2020) research. He established a negative association between neuroticism and self-regulation and found no significant associations between openness, agreeableness, and self-regulation.

Similarly, openness to experience and extraversion played significant roles in contributing to the moderately low levels of self-regulation. Individuals who are open to experience and high in extraversion are energetic, joyful, sociable, self-confident, socially competent, and capable of experiencing positive emotions (Deniz & Satici, Citation2017). They also display cognitive curiosity and a tendency to seek life experiences and intellectual growth, which plays an important role in self-regulation abilities (Bakker et al., Citation2002; de la Fuente et al., Citation2020; Paauw, Citation2020; Patterson et al., Citation2009; Yesil & Sozbilir, Citation2013).

Furthermore, the significant contribution of neuroticism to moderately low self-regulation ability may be attributed to the participants’ anxiety, emotional instability, and moodiness. Individuals high in neuroticism are prone to experiencing negative emotions, perceiving life events as losses or threats, and struggling to appreciate their own capabilities. Consequently, they may probably be finding it challenging to cope with stress (Moreira et al., 2015; Pollak et al., Citation2020). This finding aligns with previous studies indicating that a disposition towards neuroticism is associated with a lack of cognitive ability, critical thinking skills, and poor conceptual understanding, potentially due to its impact on higher-order cognitive functioning (Bidjerano & Dai, Citation2007; Moreira et al., 2015; Yesil & Sozbilir, Citation2013).

On the other hand, the contribution of social intelligence (SI) was not statistically significant in the present study. This outcome might be attributed to the participants’ low social intelligence, coupled with their moderately low self-regulation abilities. Although there is a significant gap in the literature regarding the predictive role of SI in self-regulation abilities, the non-significant predictive power of SI in this study supports the findings of a similar study by Alkhutaba (Citation2022), who observed a weak positive correlation between SI and self-efficacy. However, this finding does not agree with Hashem (Citation2021), whose study not only revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between SI and self-regulation but also demonstrated the predictive nature of SI for self-regulation.

The current study extends previous knowledge about self-regulation and its personalized contributors among university students. Specifically, the moderately low levels of self-regulation observed in university students in Kazakhstan can be attributed to low levels of agreeableness, openness, extraversion, and slightly higher levels of neuroticism. Additionally, the study highlighted the significant role of conscientiousness in the reverse direction, and the low social intelligence of the students was identified as another contributing factor to their self-regulation difficulties. The major shortcoming of this study includes relying only on the quantitative study of correlation type, while a combined method of qualitative and quantitative research may present more robust findings. Also, a multivariate analysis that includes dichotomizing self-regulation into its major components might also provide deeper insights into the actual abilities of self-regulation that might be deficient in the students. We also did not examine the three dimensions of social intelligence such as social awareness, social knowledge, and social skills (Carrera & Tononi, Citation2014; Silvera et al., Citation2001). This also could have informed us which dimensions needed to be enhanced in the university students. Notwithstanding, these limitations do not in any way compromise the strength of this study which covers the omission in literature of social intelligence, personalities and self-regulation of university students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aadland, K. N., Aadland, E., Andersen, J. R., Lervåg, A., Moe, V. F., Resaland, G. K., & Ommundsen, Y. (2018). Executive function, behavioral self-regulation, and school related well-being did not mediate the effect of school-based physical activity on academic performance in numeracy in 10-year-old children. The active smarter kids (ASK) study. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 245. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00245

- Abdul-Raouf, T., & Issa, I. (2018). Emotional intelligence and social intelligence. Arab Group for Training and Publishing. In Arabic.

- Alkhutaba, M. (2022). Social intelligence and general self-efficacy as predictors of public speaking skills among university students. World Journal of English Language, 12(8), 189–15. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v12n8p189

- Al Rab’a, Y. A., & Mukablah, N. Y. (2019). The predictive ability of self-regulation, time management, and metacognitive beliefs of academic procrastination among high school students in Madaba governorate. Journal of the Islamic University for Educational and Psychological Studies in Gaza, 27(2), 430–461.

- AlYoussef, I. (2020). An empirical investigation on students’ acceptance of (SM) use for teaching and learning. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(4), 158–178. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i04.11660

- Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & De Vries, R. E. (2014). The HEXACO honesty-humility, agreeableness, and emotionality factors: A review of research and theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314523838

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2002). Which job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout? Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Balkis, M., & Duru, E. (2016). Procrastination, self-regulation failure, academic life satisfaction, and affective well-being: Underregulation or misregulation form. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(3), 439–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0266-5

- Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00024

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

- Bidjerano, T., & Dai, D. Y. (2007). The relationship between the big-five model of personality and self-regulated learning strategies. Learning & Individual Differences, 17(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2007.02.001

- Blair, C., & Ku, S. (2022). A hierarchical integrated model of self-regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 725828. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.725828

- Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 711–731. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221

- Briley, D. A., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2014). Genetic and environmental continuity in personality development: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(5), 1303–1331. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037091

- Carey, K. B., Neal, D. J., & Collins, S. E. (2004). A psychometric analysis of the self-regulation questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors, 29(2), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.001

- Carrera, E., & Tononi, G. (2014). Diaschisis: Past, present, future. Brain A Journal of Neurology, 137(9), 2408–2422. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu101

- Connor-Smith, J. K., & Flachsbart, C. (2007). Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 93(6), 1080–1107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO personality inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5

- de la Fuente, J., Paoloni, P., Kauffman, D., Yilmaz Soylu, M., Sander, P., & Zapata, L. (2020). Big five, self-regulation, and coping strategies as predictors of achievement emotions in undergraduate students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103602

- Deniz, M. E., & Satici, S. A. (2017). The relationships between big five personality traits and subjective vitality. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 33(2), 218–224. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.261911

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

- Ebrahimpoor, H., Zahed, A., & Elyasi, A. (2013). The study of relationship between social intelligence and organizational performance (Case study: Ardabil regional water company’s managers). International Journal of Organizational Leadership, 2(1), 1–10. https://ijol.cikd.ca/article_60352_0b1296173adcd7ede114d6f42c02f2af.pdf

- Goleman, D. (2014). Leading for the long future. 2014(72), 34–39. Leader to Leader.

- Gulliford, L., Morgan, B., Hemming, E., & Abbott, J. (2019). Gratitude, self-monitoring and social intelligence: A prosocial relationship? Current Psychology, 38(4), 1021–1032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00330-w

- Hashem, E. S. A. (2021). Self-regulation and its relationship to social intelligence among college of education female students at Prince Sattam University. European Journal of Educational Research, 10(2), 865–879. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.10.2.865

- Hofer, J., Busch, H., & Kartner, J. (2011). Self–regulation and well–being: The influence of identity and motives. European Journal of Personality, 25(3), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.789

- Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2002). Relationship of personality to performance motivation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 797–807. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.797

- Kihlstrom, J. F., & Cantor, N. (2000). Social intelligence. Handbook of intelligence, 2, 359–379.

- Kumar, K., & Bakhshi, A. (2010). The five factor model of personality: Is there any relationship? Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(1), 25–34. SID. https://sid.ir/paper/630258/en

- Lievens, F. R., & Chan, D. (2017). Practical intelligence, emotional intelligence, and social intelligence. Handbook of employee selection, 342–364. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/550

- Loflin, D. C., & Barry, C. T. (2016). ‘You can’t sit with us’: Gender and the differential roles of social intelligence and peer status in adolescent relational aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 91, 22–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.048

- Malanchini, M., Engelhardt, L. E., Grotzinger, A. D., Harden, K. P., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2019). “Same but different”: Associations between multiple aspects of self-regulation, cognition, and academic abilities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(6), 1164–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000224

- Mambetalina, A., Lawrence, K., Amangossov, A., Mukhambetkalieva, K., & Demissenova, S. (2024). Giftedness characteristic identification among Kazakhstani school children. Psychology in the schools, 61(6), 2589–2599. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.23173

- Matthews, G., Schwean, V. L., Campbell, S. E., Saklofske, D. H., & Mohamed, A. A. (2000). Personality, self-regulation, and adaptation: A cognitive-social framework. In B. Monique, R. P. Paul, & Z. Moshe (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 171–207). Academic Press.

- Matzler, K., Renzl, B., Mooradian, T., von Krogh, G., & Mueller, J. (2011). Personality traits, affective commitment, documentation of knowledge, and knowledge sharing. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(2), 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.540156

- McCabe, L. A., & Brooks‐Gunn, J. (2007). With a little help from my friends?: Self‐regulation in groups of young children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28(6), 584–605.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of personality & social psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. Guilford Press.

- Mohamed, E. S. A. (2021). The impact of social intelligence and employees’ collective self-efficacy on service provider’s performance in the Egyptian governmental hospitals. International Journal of Disruptive Innovation in Government, 1(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDIG-07-2020-0003

- Moreira, H., & Canavarro, M. C. (2015). Individual and gender differences in mindful parenting: The role of attachment and caregiving representations. Personality & Individual Differences, 87, 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.021

- Neuenschwander, R., Cimeli, P., Röthlisberger, M., & Roebers, C. M. (2013). Personality factors in elementary school children: Contributions to academic performance over and above executive functions?. Learning & Individual Differences, 25, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.12.006

- Nigg, J. T. (2017). Annual research review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 58(4), 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12675

- Opelt, F., & Schwinger, M. (2020). Relationships between narrow personality traits and self-regulated learning strategies: Exploring the role of mindfulness, contingent self-esteem, and self-control. American Educational Research Association Open, 6(3), 2332858420949499. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858420949499

- Paauw, M. T. (2020). A study examining the relationship between personality traits and self-regulation [ Master’s thesis]. Utrecht University. https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/38780

- Park, C. L., Edmondson, D., & Lee, J. (2012). Development of self-regulation abilities as predictors of psychological adjustment across the first year of college. Journal of Adult Development, 19(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-011-9133-z

- Patterson, C. C., Dahlquist, G. G., Gyürüs, E., Green, A., & Soltész, G. (2009). Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: A multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet, 373(9680), 2027–2033. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7

- Patterson, F., Kerrin, M., & Gatto-Roissard, G. (2009). Characteristics and behaviours of innovative people in organisations. Literature review prepared for the NESTA Policy & Research Unit, 1-63. https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/characteristics_behaviours_of_innovative_people.pdf

- Payan-Carreira, R., Sebastião, L., Cristóvão, A. M., & Rebelo, H. (2022). How to enhance students’ self-regulation. http://hdl.handle.net/10174/35303

- Pollak, A., Dobrowolska, M., Timofiejczuk, A., & Paliga, M. (2020). The effects of the big five personality traits on stress among robot programming students. Sustainability, 12(12), 5196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125196

- Rakes, G. C., & Dunn, K. E. (2010). The impact of online graduate students’ motivation and self-regulation on academic procrastination. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 9(1). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=34818473e8d5c1fd85d473bfa50794b947fe380f

- Sandars, J., & Cleary, T. (2011). Self-regulation theory: Applications to medical education: AMEE guide No. 58. Medical Teacher, 33(11), 875–886. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.595434

- Schunk, D. H., & Greene, J. A. (2018). Historical, contemporary, and future perspectives on self-regulated learning and performance. In D. H. Schunk & J. A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 1–15). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Šebeňa, R., Orosová, O., Helmer, S., Petkeviciene, J., Salonna, F., Lukacs, A., & Mikolajczyk, R. (2018). Psychometric evaluation of the short self-regulation questionnaire across three European countries. Studia psychologica, 60(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2018.01.748

- Sethi, U. J., & Sharma, M. S. (2023). An empirical study on social intelligence and self-efficacy in information technology organizations. Resmilitaris, 13(2), 4145–4155.

- Shiner, R., & Caspi, A. (2003). Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(1), 2–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00101

- Silvera, D., Martinussen, M., & Dahl, T. I. (2001). The Tromsø social intelligence scale, a self‐report measure of social intelligence. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42(4), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00242

- Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Vidovic, V., Saklofske, D. H., Stoeber, J., & Benoit, A. (2019). Perfectionism and the five-factor model of personality: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(4), 367–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318814973

- Thorndike, E. L. (1920). Intelligence examinations for college entrance. Journal of Educational Research, 1(5), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1920.10879060

- Tucker-Drob, E. M., Briley, D. A., Engelhardt, L. E., Mann, F. D., & Harden, K. P. (2016). Genetically-mediated associations between measures of childhood character and academic achievement. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 111(5), 790–815. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000098

- Vedel, A., & Poropat, A. E. (2017). Personality and academic performance. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, 1–9.

- Wang, H., Yang, J., & Li, P. (2022). How and when goal-oriented self-regulation improves college students’ well-being: A weekly diary study. Current Psychology, 41, 7532–7543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01288-w

- Weis, S., & Süß, H. M. (2007). Reviving the search for social intelligence–A multitrait-multimethod study of its structure and construct validity. Personality & Individual Differences, 42(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.027

- Włodarczyk, D., & Obacz, W. (2013). Perfectionism, selected demographic and job characteristics as predictors of burnout in operating suite nurses. Medycyna pracy, 64(6), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.13075/mp.5893.2013.0071

- Yesil, S., & Sozbilir, F. (2013). An empirical investigation into the impact of personality on individual innovation behaviour in the workplace. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 81, 540–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.474

- Zbihlejova, L., & Birknerova, Z. (2022). Analysis of the links between social intelligence and coping strategies of business managers in terms of development of their potential. Societies, 12(6), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060177

- Zhao, J., Meng, G., Sun, Y., Xu, Y., Geng, J., & Han, L. (2021). The relationship between self-control and procrastination based on the self-regulation theory perspective: The moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 40(10), 5076–5086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00442-3

- Zuckerman, M., Kuhlman, D. M., Joireman, J., Teta, P., & Kraft, M. (1993). A comparison of three structural models for personality: The Big Three, the Big Five, and the Alternative Five. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 65(4), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.757