ABSTRACT

Transitions can be described as passage/movement from one life phase, condition, or status to another, where people learn to adapt to the change through inner reorientation, adaptation, and/or transformation. The aim was to explore whether educational transitions during adolescence and emerging adulthood relate to loneliness and mental health. A systematic review was conducted. A total of 32 articles were included. Educational transitions were associated with both positive and negative outcomes. Individual variables might impact how a transition is experienced. To alleviate negative outcomes for young people, social support and targeted interventions should be developed, and support made available and accessible. Interventions should focus on preventing disruptions in social networks and increasing connections and collaborations between support networks across each educational stage. Future research should examine how interventions can support individuals who are negatively affected by educational transitions.

Introduction

Adolescence (ages 10–19) (World Health Organization, Citationn.d.) is a period of vulnerability and adjustment (Buchanan et al., Citation1992; Heinrich & Gullone, Citation2006), while emerging adulthood (ages 18–29) (Arnett, Citation2014) is marked by frequent change (Arnett, Citation2000). Studies have shown that young people report more loneliness than the elderly (Barreto et al., Citation2021; Heinrich & Gullone, Citation2006), with elevated levels during adolescence (Heinrich & Gullone, Citation2006; Qualter et al., Citation2015), emerging adulthood (ages 18–30) (Luhmann & Hawkley, Citation2016; Shovestul et al., Citation2020), and across the college transition (Hysing et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the onset of most mental disorders begins in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood (de Girolamo et al., Citation2012; Kessler et al., Citation2007), with about 75% starting before age 24 (Fusar-Poli, Citation2019).

Previous literature notes that changes in the social environment, accompanied by physical or psychological developmental shifts, can heighten loneliness prevalence rates (Qualter et al., Citation2015). During adolescence and emerging adulthood, educational transitions often involve renegotiating relationships with professionals, peers, and family (Jindal-Snape, Citation2016), adjusting to larger classes and new teachers (Evans et al., Citation2018), facing new academic and social demands, developing new behaviours (Mikal et al., Citation2013), concerns about social acceptance (Hanewald, Citation2013), and moving to a larger building (Eccles & Roeser, Citation2011). While these changes can be positive, they might also be stressful and traumatic, having a negative impact on well-being (Jindal-Snape, Citation2016).

Education systems

According to Ritchie et al. (Citation2023), a transition has occurred throughout the world over the past few centuries, with most people having access to some form of education. Access to education is even considered a fundamental right in many countries, which has resulted in increased literacy rates, enrollment, and attendance. Nevertheless, the quality and duration of education varies throughout the globe (Ritchie et al., Citation2023). As such, education systems throughout the world can differ.

Many countries have education systems compromising primary, lower secondary, upper secondary, and higher education. The entry age and duration of each level can vary by country and region. In upper secondary/high school, students can choose between general education or technical and vocational training. After upper secondary, students can choose to attend vocational schools, technical training, colleges, universities, specialized institutions, or short-cycle higher education institutions. The duration of higher education varies by degree and institution (Australian Government Department of Education and Training, Citationn.d.; European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Citation2019; European Commission, Citation2022; European Commission, Citation2023a, Citation2023c, Citation2024; Government of Canada, Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Scholaro Database, Citationn.d.-a, Scholaro Database, Citationn.d.-b; Scholaro Database, Citationn.d.-c; U.S. Department of Education, Citation2005; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; World education news plus reviews, Citation2016).

For a general overview of the worldwide education systems, see .

Table 1. General overview of worldwide education systems.

Educational transitions in relation to loneliness and mental health

Previous studies indicate that students often face difficulties adjusting to middle school, particularly those reporting low self-esteem or ability, who may experience poorer school transitions. Anxiety, unpreparedness, or prior victimization can lead to poorer peer transitions (West et al., Citation2008). The transition to middle school may encompass both positive and negative experiences with peers and teachers. Positives include interacting with a broader group of peers and thus experiencing opportunities to form new friendships, create new friendship groups, change identities, or become friends with older peers (7). Negatives can include leaving old friends behind or losing old friends, struggling to make new friends, or struggling because of interaction with older and taller peers (10) (Jindal-Snape et al., Citation2020). Most students report instability in their friendships over the transition, with only a quarter keeping their best friend. Maintaining friendships across this transition is linked to higher academic attainment and lower levels of conduct problems (Ng-Knight et al., Citation2019).

Transitioning to high school can impact anxiety, loneliness, depression, or self-worth. The new and unpredictable context can strain psychological resources and disrupt social networks or connections with educators and staff. Students may interact with older or newer peers and classmates. Some students report no change or improvement in peer relationships, while others face peer stressors and thereby also increased levels of depression (Benner, Citation2011). This transition is linked to increased depressive symptoms and lower school belonging, with changes in peer and parental support significantly associated with depressive symptoms (Newman et al., Citation2007). Andersen et al. (Citation2021) also identified four mental health groups during this transition: flourishing, moderately mentally healthy, emotionally challenged, or languishing. Those in the latter three groups have an increased risk of dropping out of school, with languishing students experiencing more problems with positive mental health factors and higher probability of negative mental health factors.

The transition to higher education can be exciting, offering new experiences and networks, however, some students may feel inadequately prepared and struggle to adapt to the transition (Jaud et al., Citation2023). The first semester might be the most straining, with distress decreasing during later semesters (Bewick et al., Citation2010). Significant changes in social and psychological well-being occur during the first year, with effects plateauing but not completely resolving over time (Conley et al., Citation2014). Many students feel lonely due to insufficient time to build connections and often experience loneliness from moving residences, being separated from previous networks, or lacking new social networks (Jaud et al., Citation2023; Sundqvist & Hemberg, Citation2021).

In earlier review articles, various aspects of the transition to middle school (Beatson et al., Citation2023; Bharara, Citation2019; Donaldson et al., Citation2023; Evans et al., Citation2018; Hughes et al., Citation2013; Jindal-Snape & Bagnall, Citation2023; Mumford & Birchwood, Citation2021; Nuske et al., Citation2019; Symonds & Galton, Citation2014) and higher education (Carragher & McGaughey, Citation2016; Hurst et al., Citation2013; Kirst et al., Citation2014; Maillet & Grouzet, Citation2023) have been investigated, as well as educational transitions for those aged 8–23 (Metzner et al., Citation2020). However, no reviews have examined whether educational transitions are related to loneliness and mental health among adolescents and emerging adults (ages 10–29).

In brief, while earlier research has shown that educational transitions can be linked to young people’s loneliness and mental health issues, no reviews have been undertaken through which the results from previous studies have been synthesized specific to adolescents and emerging adults. We therefore sought to synthesize the existing knowledge on whether educational transitions are related to loneliness and mental health among adolescents and emerging adults.

Aim

The aim was to explore whether educational transitions during adolescence and emerging adulthood relate to loneliness and mental health.

Method

Design

A systematic review was conducted. Systematic reviews allow for the identification, assessment, and synthesis of findings from relevant health-related studies (Gopalakrishnan & Ganeshkumar, Citation2013). This approach allows for uncovering/revealing international evidence, confirming current practices, investigating variations or conflicting results, and/or identifying topics for future research (Munn, Peters, et al., Citation2018). The review was undertaken as a nine-step process, including articulation of objectives and research questions, determining inclusion and exclusion criteria, conducting a comprehensive search, screening and selecting studies, assessing the quality/validity of included studies, analysing data, presenting and synthesizing results, interpreting findings, and reporting the review methodology (Munn, Stern, et al., Citation2018).

Concepts

Emanating from the World Health Organization’s (Citationn.d..) definition of adolescents as well as Arnett’s (Citation2014) definition of emerging adulthood, young people aged 10–29 were included in this review.

Loneliness, defined as a negative feeling arising from deficient social relationships, whether qualitatively or quantitatively lacking (Perlman & Peplau, Citation1981), encompasses two types: emotional and social. Social loneliness results from deficiencies in one’s social network, while emotional loneliness arises from a lack of deep, close emotional relationships (Weiss, Citation1973).

Galderisi et al. (Citation2015) defines mental health as more than the absence of mental illness; it is a dynamic state of internal balance where individuals can utilize their abilities in harmony with societal values. It encompasses basic social and cognitive skills, emotional expression and regulation, empathy, coping flexibility, social functioning, and a harmonious mind-body relationship. These components can contribute to varying extents to a state of internal equilibrium.

Transitions as a concept

Transitions encompass passages from one phase to another (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994), involving inner reorientation and adaptation (Kralik et al., Citation2006). They arise from changes in one’s environment. Transitions can be gradual or sudden, anticipated or unexpected, pleasant or unpleasant (Chick & Meleis, Citation1986). These shifts can have lasting effects on a person’s health and well-being (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994).

Multiple and multidimensional transitions theory view transitions as ongoing processes that occur across various domains and can influence others’ experiences (Jindal-Snape & Rienties, Citation2016). These transitions are dynamic and interconnected, reflecting the constantly changing environment (Jindal-Snape, Citation2023).

Data collection

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews were followed (Page et al., Citation2021). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to screen and select articles. Inclusion criteria involved empirical papers and reports published between 2011–2021, focusing on individuals aged 10–29. The timeframe was chosen to provide an up-to-date synthesis of recent evidence. Articles examining school transitions relevant to lower secondary/middle school, upper secondary/high school, or higher education (college/university) were included. A broader sample age was used due to the longitudinal approaches employed in many studies.

We included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies on loneliness and mental health across educational transitions. Exclusions were made concerning studies with inaccessible DOI’s, under review, or lacking peer-review, as well as those unrelated to educational transitions or not published in English.

To identify relevant studies, searches of various databases (ERIC, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycInfo) were undertaken. Keywords and Boolean operators (AND, OR) were combined to identify articles and ensure the inclusion of multidisciplinary studies. The keywords used were; Adolescents”, ‘Teenagers’, Young adults”, ‘Teen’, ‘Youth’, ‘Educational transitions’, ‘School Transitions’, ‘Transition of schools’, Transitional programs”, ‘Transition to adulthood’, ‘Transition to emerging adulthood’, ‘Life experience’, ‘Transitioning’, ‘Life transition’, ‘Life changes’, ‘Lifestyle changes’, ‘Loneliness’, ‘Social isolation’, ‘Social exclusion’, ‘Lonely’, ‘Mental health’, ‘Mental illness’, ‘Mental disorder’, ‘Psychiatric illness’, ‘Wellbeing’, ‘Well-being’, ‘Psychological well-being’. The search for grey literature was limited.

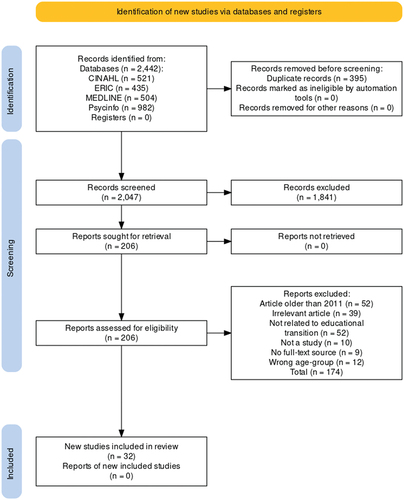

Out of 2442 articles initially found, 395 duplicates were removed using Zotero reference management software, leaving 2047 articles for screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria. The first author screened and assessed the articles’ titles, abstracts, conclusions, and results. The second author reviewed screened articles to ensure reliability and assess risk for bias. The second, third, and fourth authors independently reviewed the initial analysis and results. A total of 32 articles were included: six qualitative (18.75%), 25 quantitative (78.13%), and one (3.13%) mixed methods study. Two studies (8%) encompassed a broader age range than what was delineated in the inclusion criteria: Kingery et al. (Citation2011) (9–11-year-olds), and Thomas et al. (Citation2020) (18–35-year-olds). These were included due to their meaningful contribution relevant to pre- or post-transition experiences. For an overview of the screening process, see .

The first and fourth author separately performed the quality appraisal, with the aim of describing the quality of the included studies. Due to the challenging nature of evaluating mixed studies reviews, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Version 2018) (Hong et al., Citation2018), developed for the assessment of mixed studies reviews, was used.

Data analysis and synthesis

The analysis was inspired by Braun and Clarke’s qualitative thematic analysis framework, aiming to identify, analyse, and report themes within the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). It compromised six phases: data familiarization through repeated readings, coding the data to identify features relevant to the research questions, generating themes and subthemes by comparing similarities, differences, and overlaps between the codes and clustering together codes sharing unifying features. The codes and themes were then reviewed in relation to the entire data set. Themes were named and defined. Lastly, the analysis was reported. The first author conducted initial coding and theme generation, with the second and third authors providing feedback. Disagreements were resolved through discussion to reach consensus.

The NVivo transcription programme (released in March 2020) was used for analysis (Lumivero, Citation2020). The findings are presented below and discussed in relation to Transitions Theory (Meleis, Citation2010) and Multiple and Multidimensional Transitions Theory (Jindal-Snape, Citation2016; Jindal-Snape & Rienties, Citation2016).

Ethical considerations

To ensure ethical conduct, the ethical principles outlined by TENK (Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics TENK, Citation2023) were followed throughout the entire research process.

Results

The characteristics of the included studies, including authors, publication year, country, aim, design, sample, gender distribution, age, setting, findings, and quality are presented in . Studies were published between 2011 and 2021. Most (9) were conducted in the United States (28.13%). Eight (25%) were conducted in Australia, six (18.75%) in the United Kingdom and two in Canada (6.25%). The remaining studies were conducted in Switzerland/Germany (3.13%), Finland (3.13%), Germany (3.13%), Italy (3.13%), United States/Canada (3.13%), Israel (3.13%), or China (3.13%).

Table 2. Characteristics of the included studies.

Participant sample sizes ranged from 9 in a qualitative study (Volstad et al., Citation2020) to 3459 in a quantitative study (Lester et al., Citation2013). Participants’ ages ranged from 9–35 years. Participant gender distribution varied, with male participants ranging from 11.11% in a qualitative study (Volstad et al., Citation2020) to 58% in a quantitative study (Carr et al., Citation2013). Ten studies (31.25%) examined the transition from primary to lower secondary/middle school, four studies (12.50%) focused on the transition to upper secondary/high school, and 18 studies (56.25%) explored the transition to higher education (college/university). Fifteen studies (46.88%) utilized a longitudinal approach, with six studies (40%) collecting data at two time points, five studies (33.33%) at three time points, three studies (20%) at four time points, and one study (6.67%) at six time points.

Three main themes and 8 subthemes were generated ().

Table 3. Overview of main themes and subthemes.

Positive and negative transition outcomes

Positive health, improved relationships, and more school activities

A positive transition to middle school can lead to better social and emotional health, decreased loneliness, improved peer support, safety at school, and reduced anxiety and victimization (Waters et al., Citation2012). Students may look forward to sports, clubs, school events, new friendships, more school activities, and classes (Waters et al., Citation2014). Similarly, students transitioning to university report that new friends, social activities, and academic recognition positively affect their well-being (qualitative study; Wrench et al., Citation2013). The transition to college/university is also seen as an opportunity to enhance personal strengths, gain new insights, and learn to better cope with challenges (qualitative study; Volstad et al., Citation2020).

Difficulty and concerns about the transition, increased loneliness, stress, anxiety, and depression

Difficulty with the elementary to middle school transition might be associated with depressive symptoms and schoolwork difficulty, with 29% of students finding it somewhat difficult and 6% very difficult (Fite et al., Citation2019). Around 25% experience the transition as being difficult (25%), expressing concerns about academic, social, and structural changes or fitting in (Waters et al., Citation2014). Young people’s mental health could be negatively affected by concerns of not fitting in or being judged as well as academic pressures (qualitative study; Spencer et al., Citation2020). The transition was also associated with increased anxiety, depression, emotional problems, conduct problems, and overall difficulties (Lester & Cross, Citation2015). Some students report social and emotional health challenges (anxiety, depression) and feeling less safe at school up to nine months after the transition (Waters et al., Citation2012). While one-third of students maintain high well-being, about 10% of students report low levels of well-being after the transition (Virtanen et al., Citation2019).

Across the high school transition, students’ express concerns about competence (maintaining good grades, managing workload, adjustment to new school), social belongingness (concerns about friendships, acceptance, liking teachers), and control (freedom, rules, transportation) (Wentzel et al., Citation2019). This transition is also associated with a significant increase in feelings of loneliness (Benner et al., Citation2017).

During the transition to higher education, 57% of students may experience increased loneliness, 37% less loneliness, and 6% no change (Drake et al., Citation2016). High levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms can correlate with increased life stress, while those with higher depressive symptoms might experience difficulties adapting to the transition (Morton et al., Citation2014). Even after six months at college/university, about 40% report higher levels of negative affect and stress, decreased sleep quality and quantity (hours of sleep), and reduced capability to deal with stressors (Lev Ari & Shulman, Citation2012). Increased loneliness can be associated with steeper cortisol levels (Drake et al., Citation2016), and increased daily stress can increase daily loneliness and depression while decreasing daily happiness (Burke et al., Citation2016).

Emotional and social loneliness are linked to anxiety and depression across the transition to higher education (Diehl et al., Citation2018). Living away from home for the first time and in student accommodation can lead to loneliness, homesickness, and stress, while part-time work alongside studies might increase stress (qualitative study; Worsley et al., Citation2021). Students who feel unprepared for the transition might experience confusion, frustration, stress, anxiety, or fear failure in their new environment. Students also report loneliness, isolation, alienation, and feeling depressed (qualitative study; Wrench et al., Citation2013).

Individual variables across transitions

Coping strategies and personal resources

Most college/university students cope more efficiently with daily stressors during their second semester compared to their first (Lev Ari & Shulman, Citation2012). There seems to be a link between loneliness, cortisol, and coping efficacy; coping efficacy may act as a protective factor and help with stress regulation for those struggling with loneliness across this transition (Drake et al., Citation2016). High or low disengagement coping among those experiencing the transition to college/university might impact self-esteem and depressive symptomology; high levels of disengagement coping, and low self-esteem can be associated with an increase in depressive symptoms (Lee et al., Citation2014).

First year college/university students who perceive low social belonging tend to have higher self-esteem, increased relatedness to others, and decreased loneliness if they have the capacity to seek solitude for autonomous reasons (Nguyen et al., Citation2019). Having higher self-compassion is associated with less homesickness and depression, greater satisfaction with attending college/university, and the capacity to deal with difficulties more successfully (Terry et al., Citation2013). Across the transition to higher education, students with higher optimism seem to experience less stress than those with low optimism, meanwhile those with higher self-reported self-efficacy (belief in own ability) adapt better to college/university than those with low self-efficacy (Morton et al., Citation2014). Willingness to adapt to the environment, flexibility, openness to opportunities, and willingness to step outside of one’s comfort zone promote flourishing, new social connections and a sense of belonging (qualitative study; Volstad et al., Citation2020).

Sociodemographic characteristics

While females may be more concerned about the transition to middle school, they are also more likely to look forward to changes in social dynamics and participate in events and activities (Waters et al., Citation2014). Across the middle school transition, at grade 7, boys are more likely to have low well-being. Females also report higher friendship quality across the transition to middle school or might be more likely to be involved in high school activities (Kingery et al., Citation2011). Also, having higher socio-economic status seems to protect students from lower well-being across the transition to middle school (Virtanen et al., Citation2019).

In 8th grade, females experience higher levels of depressive symptoms that decline across the transition to high school, while males experience lower levels in 8th grade that increase across this transition. For females, continuity in academic activities across the transition (grades 8–9) might be linked to more loneliness, while continuity in sports might be linked to less loneliness (Bohnert et al., Citation2013). In the U.S., foreign-born students might experience decreased loneliness and school engagement compared to native-born students, who tend to experience increased loneliness across the high school transition (Benner et al., Citation2017). In Germany, having an immigrant background is associated with increased social loneliness across the transition to higher education (Diehl et al., Citation2018).

Personality traits and attachment

Status-related personality traits such as intrasexual competitiveness (competitiveness with those of the same gender), entitlement (heightened sense of deservingness or self-import for deferential treatment), and dominance (trait and facial dominance) might impact students’ loneliness across the transition to college/university (Rahal et al., Citation2021). More intrasexually competitive students report lower loneliness due to increased subjective dorm status. Entitled students experience less initial loneliness with no change over the first year, while less entitled students (low or average) experience more initial loneliness but a decrease over the year.

Those who demonstrate strong social approach motivation report stable or low levels of loneliness, while those who demonstrate strong social avoidance motivation report high levels of loneliness. Although social avoidance motives may initially be associated with loneliness, over time, feelings of loneliness lessen (Nikitin & Freund, Citation2017). Even attachment style is associated with loneliness and perceived institutional integration across the transition to higher education; attachment insecurity might predict increased loneliness and poorer integration (Carr et al., Citation2013).

Alleviating negative transition experiences

Social support as a positive resource across transitions

Peer acceptance, friendship quality, and number of friends can predict loneliness, while peer relationships can provide support across the transition to middle school. Peer acceptance is also linked to academic achievement and school involvement (Kingery et al., Citation2011). Initially, parents, followed by friends, teachers, peer mentors, school counsellors, and older students, play crucial roles in assisting with this transition (Fite et al., Citation2019).

Peer support is the strongest protective predictor for well-being during the last year of primary school and the strongest protective factor for mental well-being (against depression and anxiety) during the second year of middle school (Lester & Cross, Citation2015). Friendships play a crucial role in student connectedness, safety, happiness, stress, loneliness, and boredom across this transition (qualitative study; Heinsch et al., Citation2020). Changes in support from peers, teachers, and family can impact well-being (Virtanen et al., Citation2019), while feeling connected to teachers predicts emotional well-being (predictive of pro-social behaviour and protecting against peer problems, hyperactivity, overall difficulties) across this transition (Lester & Cross, Citation2015). Greater peer support is linked to a decreased chance of victimization at the start of middle school (Lester et al., Citation2013). Bullying and discrimination might be key trigger for mental ill health across this transition (qualitative study; Spencer et al., Citation2020).

Stable or increased support from friends is associated with greater school engagement and decreased socioemotional disruptions across the transition to high school (Benner et al., Citation2017). Closeness with teachers is linked to academic achievement, while perceived conflict with teachers is associated with increased conduct problems or hyperactive behaviour (Longobardi et al., Citation2016). Perceived competence in the eighth grade significantly predict emotional well-being in the ninth grade, as does a sense of belonging with peers (Wentzel et al., Citation2019).

Perceived social support may mediate the link between self-esteem and depressive symptoms across the transition to higher education (Lee et al., Citation2014), while living in shared accommodation with roommates can provide crucial emotional and instrumental support (qualitative study; Worsley et al., Citation2021). Perceiving a sense of community, high social capital, and satisfaction with the welcome received are associated with less loneliness across this transition (Thomas et al., Citation2020). Forming more friendships in the first semesters is positively related to self-reported health and healthy eating, as well as better general health due to perceived social support (Klaiber et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, increased parental support is linked to fewer transition disruptions (depressive symptoms, loneliness) but increased grade disruptions.

Even being in a committed relationship or married protects against emotional loneliness across the transition to higher education (Diehl et al., Citation2018). Parental and family support is crucial, contributing to students’ ability to flourish (qualitative study; Volstad et al., Citation2020). For those experiencing high levels of loneliness, daily social connections are associated with both more time asleep, longer time spent in bed, and next-day increased cortisol awakening response across the transition. Even daily communication of openness and assurances with a parent might moderate the association between daily stress and loneliness (Burke et al., Citation2016). Family cohesion (family emotional bonding and interdependence) could also influence social adjustment and thereby sense of security across the transition to college/university (Ye et al., Citation2019).

Interventions and targeted supports

Whole-school interventions, including classroom curriculum, school policy, environment and school-home-community efforts, and increasing student/teacher/staff/parent knowledge and skills regarding transitions can positively impact victimization, depression, anxiety, bullying, stress, loneliness, and feelings of school safety across the first year of the transition to middle school (Cross et al., Citation2018). Support needs better advertising and tailoring, while improved mental health education for students and teachers, along with safe spaces in schools, could enhance mental health (qualitative study; Spencer et al., Citation2020). Excursions and camp activities that increase peer interaction are also important across this transition (Heinsch et al., Citation2020).

Across the transition to high school, continuous involvement in sports or academic activities benefits students’ social adjustment and increases friendships, while continuous involvement in academic activities is also associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Bohnert et al., Citation2013).

Workshops on independent living, operational teams, residential advisers, and mental health support services can foster a supportive environment and a sense of belonging across the transition to higher education. Increased opportunities for connection, such as a course induction week, are crucial for forming friendships (qualitative study; Worsley et al., Citation2021), while pre-arrival social media groups, despite some issues, can help students make contacts, create networks, and find roommates (qualitative study; Thomas et al., Citation2017). Informal and formal programmes, like peer learning programmes, can enhance campus involvement and provide a environment for receiving support (qualitative study; Volstad et al., Citation2020).

Feeling safe at school and school belonging/connectedness

Feeling safe and connected to school is a protective factor for well-being across the transition to middle school (Lester & Cross, Citation2015), while feeling less safe and less connected is linked to bullying victimization (Lester et al., Citation2013). Stable or increasing school belonging decreases emotional disruptions and increases school engagement, whereas decreasing school belonging is linked to increased depressive symptoms and loneliness across the transition to high school (Benner et al., Citation2017). A sense of social belonging and autonomous motivation for solitude predict lower levels of depression and loneliness, and higher self-esteem and relatedness to others across the transition to higher education (Nguyen et al., Citation2019). Small class sizes contribute to a sense of belonging and social networks across the transition to college/university (qualitative study; Volstad et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

Positive and negative transition outcomes

Transitions to middle school are associated with anticipation of new activities, events, and meeting new people (Waters et al., Citation2014; Wrench et al., Citation2013), and a positive transition can lead to future social and emotional health benefits (Waters et al., Citation2012). Higher education can help students enhance personal strengths and address challenges, contributing to their overall well-being (Volstad et al., Citation2020).

Previous research has seen that transitions in general can lead to new opportunities (Chick & Meleis, Citation1986). Middle school transitions have been associated with increased opportunities to form new friendships or friendship groups, new peer relationships, or friendships with older peers (Jindal-Snape et al., Citation2020), while high school transitions have been associated with anticipating new school events, appreciating new friendships, and choosing more classes (Uvaas & McKevitt, Citation2013).

Our review found that for 25–40% of students, the move to middle school can be difficult (Fite et al., Citation2019; Spencer et al., Citation2020; Waters et al., Citation2014). Students may face anxiety, depression, and feel less safe at school (Waters et al., Citation2012). About 10% report low well-being during this transition (Virtanen et al., Citation2019). Transitions to high school can bring concerns about competence, social belonging, control, and loneliness (Benner et al., Citation2017; Wentzel et al., Citation2019), while students in higher education may face increased loneliness, homesickness, stress, confusion, frustration, fear of failure, negative affect, stress, and impaired sleep (Drake et al., Citation2016; Lev Ari & Shulman, Citation2012; Worsley et al., Citation2021; Wrench et al., Citation2013).

Previous studies show that educational transitions often bring new and unpredictable contexts (Benner, Citation2011), disrupting social networks and introducing new academic and social demands (Mikal et al., Citation2013), increasing concerns about social acceptance (Hanewald, Citation2013), which can strain psychological resources and elevate loneliness (Benner, Citation2011; Mikal et al., Citation2013). As educational transitions often include renegotiation of relationships (Jindal-Snape, Citation2016), while adolescence and emerging adulthood constitute a period when peer groups and intimate relationships become more important (Qualter et al., Citation2015), these periods can be challenging to adolescents and emerging adults’ loneliness and mental health. When individuals go through changes in the social environment paired with physical or psychological developmental shifts, loneliness prevalence rates can increase (Qualter et al., Citation2015). Transitions are usually linked to increased loneliness and vulnerability to negative health outcomes (Chick & Meleis, Citation1986), including stress, depression, anxiety (Chick & Meleis, Citation1986; Mikal et al., Citation2013), low self-esteem, and loneliness (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994). Concerns about middle school transitions have previously been associated with loneliness (Rice et al., Citation2021), while high school transitions may increase the risk of negative mental health factors and dropout rates (Andersen et al., Citation2021). College students often face deteriorating self-esteem, depression, anxiety, stress, and decreased social support (Conley et al., Citation2018). While many navigate transitions successfully, some find them traumatic or stressful, negatively impacting well-being due to the loss of connections and new settings (Jindal-Snape, Citation2016).

Individual variables across transitions

Various individual variables impact students’ experience of loneliness and mental health, including coping strategies (Drake et al., Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2014), personal resources (Morton et al., Citation2014; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Terry et al., Citation2013; Volstad et al., Citation2020), sociodemographic characteristics (Benner et al., Citation2017; Bohnert et al., Citation2013; Diehl et al., Citation2018; Kingery et al., Citation2011; Virtanen et al., Citation2019), personality traits (Rahal et al., Citation2021; Nikitin & Freund), and attachment style (Carr et al., Citation2013).

Other researchers have also seen that higher self-esteem and resilience have been associated with improved adjustment and coping strategies among adolescents (Dumont & Provost, Citation1999). Adolescents with lower self-esteem may experience more negative transitions, leading to increased depression or lower attainment (van Rens et al., Citation2017). According to Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions Theory, individual dispositions such as problem-solving skills, adaptability, resourcefulness, and psychological adaptation can influence transition success (Jindal-Snape, Citation2023). Similarly, variables like expectations, knowledge/skills, environmental resources, and planning level can impact transition experiences (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994). Insufficient knowledge relevant to meeting transition demands can negatively affect health outcomes, emphasizing the importance of realistic expectations during transitions. Thus, preparing individuals with realistic expectations can decrease the level of stress experienced (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994). Preparing students for educational transitions can alleviate their concerns. Effective planning involves identifying potential needs and problems and establishing support networks (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994). Transition programmes should address various stakeholders’ needs by introducing school procedures, support new routines, familiarize parents with the environment. A transition training team of teachers, parents, students, administrators, and counsellors can be useful to evaluate, plan, and revise the programme (Cauley & Jovanovich, Citation2006), as well as aligning curricula with receiving schools’ expectations (Bangser, Citation2008).

In this review we saw that sociodemographic characteristics can impact middle school transitions, for example gender (Kingery et al., Citation2011; Virtanen et al., Citation2019; Waters et al., Citation2014) and socio-economic status (Virtanen et al., Citation2019). We also discerned that gender (Benner et al., Citation2017; Bohnert et al., Citation2013) and place of origin might influence high school transitions (Benner et al., Citation2017), while immigrant background is related to increased social loneliness across the transition to higher education (Diehl et al., Citation2018).

A previous systematic review found that females may experience decreased school and friend support and difficulties forming new peer friendships, while males may encounter increased school functioning problems during the transition to middle school (van Rens et al., Citation2017). Students with lower socio-economic status face higher victimization, lower social support, poorer adjustment, and reduced academic growth. Females also report higher rates of school concern, anxiety, and depression, while males report more concerns related to rules and teachers and exhibit more behavioural problems (Evans et al., Citation2018). Females also tend to experience more psychological distress, while males see a decrease in academic achievement during this transition (Chung et al., Citation1998). Children from minority cultures can experience the transition as being difficult (van Rens et al., Citation2017), while those with lower socio-economic status face increased loneliness if peers have a better socio-economic status (Schnepf et al., Citation2023). As individuals with lower socioeconomic status, gender, or minority students can be faced with difficulties across educational transitions, activities and support should target high-risk groups, addressing issues related to socioeconomic status, gender, and minority groups. This can include peer support groups, identifying students with behavioural problems, providing social support, involving parents, reducing course loads for struggling students, and inviting parents to meet with counselors and administrators to discuss policies and school curriculum (Cauley & Jovanovich, Citation2006).

Alleviating negative transition experiences

Our review underscores the importance of social support as a positive resource across middle school (Fite et al., Citation2019; Heinsch et al., Citation2020; Kingery et al., Citation2011; Lester & Cross, Citation2015; Lester et al., Citation2013; Virtanen et al., Citation2019), high school (Benner et al., Citation2017; Longobardi et al., Citation2016; Wentzel et al., Citation2019), and higher education transitions (Burke et al., Citation2016; Diehl et al., Citation2018; Klaiber et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2014; Thomas et al., Citation2020; Volstad et al., Citation2020; Worsley et al., Citation2021; Ye et al., Citation2021).

Research shows that social support from family, friends, partners, mentors, role models, and professional staff is crucial during transitions (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994) as well as strong social connections to others (Kralik et al., Citation2006), or external support networks (Jindal-Snape, Citation2016). Educational transitions often disrupt existing social networks with educators, staff (Benner, Citation2011), friends (Ng-Knight et al., Citation2019), and family (Sundqvist & Hemberg, Citation2021), as individuals move to new settings (Eccles & Roeser, Citation2011). The quality of peer relationships significantly predicts the severity of adolescents’ depressive symptoms (Adedeji et al., Citation2022), and relocation for educational opportunities can lead to loneliness due to adapting to new social circles (Rönkä et al., Citation2018; Sundqvist & Hemberg, Citation2021).

Instability in friendships during transitions underscores the need to maintain friendships for mental health and academic performance (Ng-Knight et al., Citation2019). Some students might experience negative middle school transitions due to difficulties in leaving friends or making new ones (Jindal-Snape et al., Citation2020). Moreover, peer stressors during the transition to high school have been linked to increased depression (Benner, Citation2011), while supportive friendships enhance resilience by influencing coping styles and encouraging effort (Graber et al., Citation2016). Friends also provide crucial support during this transition (Uvaas & McKevitt, Citation2013), while social integration, teacher bonding, extracurricular participation, and popularity impact academic achievement (Langenkamp, Citation2009). In Europe, 15-year-olds receiving support from teachers and parents report less loneliness (Schnepf et al., Citation2023). Those who transition to higher education also usually experience disruptions in social networks, leading to increased loneliness (Sundqvist & Hemberg, Citation2021). Given the importance of relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood (Qualter et al., Citation2015), interventions should prioritize peer integration and healthy relationships with parents, peers, and teachers (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994). Activities fostering strong peer connections, such as pen pal programmes, freshman awareness groups, learning subcommunities, and first-year support groups, should be implemented (Cauley & Jovanovich, Citation2006). Strategies to minimize disruptions should also be developed.

Our review found that whole-school interventions (Cross et al., Citation2018), tailored support, better mental health education (Spencer et al., Citation2020), and activities promoting peer interaction (Heinsch et al., Citation2020) are important for middle school transitions. Feeling safe and connected to school protects well-being and reduces bullying during this transition (Lester & Cross, Citation2015; Lester et al., Citation2013). For high school, continuous involvement in sports and academic activities aids social adjustment (Bohnert et al., Citation2013), and school belonging decreases emotional disruptions and increases engagement (Benner et al., Citation2017). In higher education, increasing well-being support services, fostering belonging, and enhancing connection opportunities are crucial (Worsley et al., Citation2021). A sense of belonging and autonomous motivation for solitude reduces depression and loneliness (Nguyen et al., Citation2019). Pre-arrival social media groups can help make new contacts (Thomas et al., Citation2017), and informal/formal programmes enhance campus involvement. Smaller class sizes might contribute to a sense of belonging and social networks (Volstad et al., Citation2020).

Research shows that active involvement in organized activities can improve social adjustment outcomes for at-risk youth, enhancing friendship quality and reducing loneliness (Bohnert et al., Citation2007). A study of 23 European countries found that a bullying climate among 15-year-olds doubles loneliness, while a supportive climate significantly reduces it (Schnepf et al., Citation2023). In higher education, a sense of belonging enhances self-perception and reduces problem behaviours (Pittman & Richmond, Citation2008). Environmental resources, such as organizational attributes and family/community culture, are crucial during transitions (Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994). Promoting positive transitions requires collaboration among organizations, professionals, families, communities, and media (Jindal-Snape, Citation2023). Future interventions should focus on creating a positive school climate, organized activities, and partnerships among support networks. Education policies should aim to prevent bullying and foster a cooperative climate among students, peers, and teachers (Schnepf et al., Citation2023).

Strengths and limitations

The review fills an important gap by examining how educational transitions relate to loneliness and mental health among adolescents and emerging adults across various educational transitions. The review sheds light on differences and similarities in how educational transitions relate to loneliness and mental health at different transitions. The review also has several limitations. There is a possibility that not all relatable papers have been included in the review. The search strategy encompassed a limited number of databases, and only included articles published in the English language, and was limited by date. The first author performed the screening independently, while the second author verified/discussed a proportion of the articles, which could lead to a higher risk of bias and the omission of relevant articles. The aim was to conduct a systematic review with a global perspective; however, most articles were conducted in the United States (9) and Australia (8). Ten articles were conducted in Europe, while two were conducted in Canada, and two in Asia (west and east Asia). No articles from low-income countries were included, which could have impacted the generalizability of the findings. Most studies also examined the transition to higher education (18), followed by the transition to lower secondary/middle school (10); however, only four studies examined the transition to upper secondary/high school. It would have been optimal to include equally as many articles at each educational transition. Moreover, the ages when students transition to each educational stage can also differ by country and county, while school policies, the social and political context, and preparation for educational transitions might differ by country, which could mean that transitions are likely to be experienced differently at these ages.

Conclusions

We saw that transitions were associated with both positive and negative outcomes for young people. Educational transitions might provide new opportunities but might even increase negative health outcomes. Various individual variables might impact how a transition is experienced, for example coping strategies, personal resources, sociodemographic characteristics, personality trait, or even attachment style. Social support might constitute a positive resource across transitions. To alleviate negative outcomes for young people, targeted interventions should be developed and support made available and accessible, especially for vulnerable young people. Interventions should be developed whereby students can be prepared for and supported during transitions. Additionally, academic activities should be introduced through which school belonging and the formation of peer relationships and quality-based friendships can be promoted. Lastly, a focus on the development of specific interventions appropriate for specific age groups and/or educational level should be included in future research. More qualitative research examining young people’s experiences of transitions in relation to loneliness and mental health should be undertaken.

Author contributions

Amanda Sundqvist contributed to the study conception, data collection, design, data analysis, discussion, and drafting of the manuscript. Jessica Hemberg contributed to the data collection, design, data analysis, discussion, and provided critical reflections. Ottar Ness contributed to the data analysis, discussion, and provided critical appraisal and reflections. Pia Nyman-Kurkiala contributed to the data analysis, discussion, and provided critical reflections.

Ethical considerations

To ensure ethical conduct, the ethical principles outlined by the Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity TENK (TENK, 2023) were followed throughout the entire research process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adedeji, A., Otto, C., Kaman, A., Reiss, F., Devine, J., & Ravens-Sieber, U. (2022). Peer relationships and depressive symptoms among adolescents: Results from the German BELLA study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.767922

- Andersen, S., Davidsen, M., Nielsen, L., & Tolstrup, J. S. (2021). Mental health groups in high school students and later school dropout: A latent class and register-based follow-up analysis of the Danish national youth study. BMC Psychology, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00621-7

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. The American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

- Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199929382.001.0001

- Australian Government Department of Education and Training. (n.d.). Country education profiles: Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-3071019804

- Bangser, M. (2008). Preparing high school students for successful transitions to postsecondary education and employment. National high school center. https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/PreparingHSStudentsforTransition_073108.pdf

- Barreto, M., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2021). Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personality & Individual Differences, 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110066

- Beatson, R., Quach, J., Canterford, L., Farrow, P., Bagnall, C., Hockey, P., Phillips, E., Patton, G. C., Olsson, C. A., Ride, J., McKay Brown, L., Roy, A., & Mundy, L. K. (2023). Improving primary to secondary school transitions: A systematic review of school-based interventions to prepare and support student social-emotional and educational outcomes. Educational Research Review, 40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100553

- Benner, A. D. (2011). The transition to high school: Current knowledge, future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 23(3), 299–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9152-0

- Benner, A. D., Boyle, A. E., & Bakhtiari, F. (2017). Understanding students’ transition to high school: Demographic variation and the role of supportive relationships. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 46(10), 2129–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0716-2

- Bewick, B., Koutsopoulou, G., Miles, J., Slaa, E., & Barkham, M. (2010). Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well‐being as they progress through university. Studies in Higher Education, 35(6), 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216643

- Bharara, G. (2019). Factors facilitating a positive transition to secondary school: A systematic literature review. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 8(sup1), 104–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2019.1572552

- Bohnert, A. M., Aikins, J. W., & Arola, N. T. (2013). Regrouping: Organized activity involvement and social adjustment across the transition to high school. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2013(14), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20037

- Bohnert, A. M., Aikins, J. W., & Edidin, J. (2007). The role of organized activities in facilitating social adaptation across the transition to college. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558406297940

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buchanan, C. M., Eccles, J. S., & Becker, J. B. (1992). Are adolescents the victims of raging hormones: Evidence for activational effects of hormones on moods and behavior at adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 111(1), 62–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.62

- Burke, T. J., Ruppel, E. K., & Dinsmore, D. R. (2016). Moving away and reaching out: Young adults’ relational maintenance and psychosocial well-being during the transition to college. The Journal of Family Communication, 16(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2016.1146724

- Carr, S., Colthurst, K., Coyle, M., & Elliott, D. (2013). Attachment dimensions as predictors of mental health and psychosocial well-being in the transition to university. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0106-9

- Carragher, J., & McGaughey, J. (2016). The effectiveness of peer mentoring in promoting a positive transition to higher education for first-year undergraduate students: A mixed methods systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0245-1

- Cauley, K. M., & Jovanovich, D. (2006). Developing an effective transition program for students entering middle school or high school. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues & Ideas, 80(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.80.1.15-25

- Chick, N., & Meleis, A. I. (1986). Transitions: A Nursing Concern. In A. I. Meleis (Ed.), Transitions theory: middle-range and situation-specific theories in nursing research and practice (pp. 237–257). Springer publishing company.

- Chung, H., Elias, M., & Schneider, K. (1998). Patterns of individual adjustment changes during middle school transition. Journal of School Psychology, 36(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(97)00051-4

- Conley, C. S., Kirsch, A. C., Dickson, D. A., & Bryant, F. B. (2014). Negotiating the transition to college: Developmental trajectories and gender differences in psychological functioning, cognitive-affective strategies, and social well-being. Emerging Adulthood, 2(3), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814521808

- Conley, C. S., Shapiro, J. B., Huguenel, B. M., & Kirsch, A. C. (2018). Navigating the college years: Developmental trajectories and gender differences in psychological functioning, cognitive-affective strategies, and social well-being. Emerging Adulthood, 8(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818791603

- Cross, D., Shaw, T., Epstein, M., Pearce, N., Barnes, A., Burns, S., Waters, S., Lester, L., & Runions, K. (2018). Impact of the friendly schools whole-school intervention on transition to secondary school and adolescent bullying behaviour. European Journal of Education, 53(4), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12307

- de Girolamo, G., Dagani, J., Purcell, R., Cocchi, A., & McGorry, P. D. (2012). Age onset of mental disorders and use of mental health services: Needs, opportunities and obstacles. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 21(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796011000746

- Diehl, K., Jansen, C., Ishchanova, K., & Hilger-Kolb, J. (2018). Loneliness at universities: Determinants of emotional and social loneliness among students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091865

- Donaldson, C., Moore, G., & Hawkins, J. (2023). A systematic review of school transition interventions to improve mental health and wellbeing outcomes in children and young people. School Mental Health, 15(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09539-w

- Drake, E. C., Sladek, M. R., & Doane, L. D. (2016). Daily cortisol activity, loneliness, and coping efficacy in late adolescence: A longitudinal study of the transition to college. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(4), 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415581914

- Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 28(3), 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021637011732

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. (2019). Vocational education and training in Europe: United Kingdom. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/vet-in-europe/systems/united-kingdom

- European Commission. (2022, September). The structure of the European education systems 2022/2023: Schematic diagrams. European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/21002

- European Commission. (2023a, December 14). Finland: Key features of the education system. https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/finland/overview

- European Commission. (2023b, December 14). Italy: Key features of the education system. https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/italy/overview

- European Commission. (2023c, December 14). Switzerland: Key features of the education system. https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/switzerland/overview

- European Commission. (2024, February 1). Germany: National specificities of the education system. https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/germany/overview

- Evans, D., Borriello, G. A., & Field, A. P. (2018). A review of the academic and psychological impact of the transition to secondary education. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01482

- Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics TENK. (2023). God vetenskaplig praxis och handläggning av misstankar om avvikelse från den i Finland. Forskningsetiska delegationens anvisningar 2023 [Responsible conduct of research and procedures for handling allegations of misconduct in Finland. Guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK 2023]. https://tenk.fi/sites/default/files/2023-04/Forskningsetiska_delegationens_GVP-anvisning_2023.pdf.

- Fite, P., Frazer, A., DiPierro, M., & Abel, M. (2019). Youth perceptions of what is helpful during the middle school transition and correlates of transition difficulty. Children & Schools, 41(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdy029

- Fusar-Poli, P. (2019). Integrated mental health services for the developmental period (0 to 25 years): A critical review of the evidence. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00355

- Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., & Sartorius, N. (2015). Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association, 14(2), 231–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20231

- Gopalakrishnan, S., & Ganeshkumar, P. (2013). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 2(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.109934

- Government of Canada. (2022a, January 11). Education in canada: Post-secondary. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/new-immigrants/new-life-canada/education/types-school/post-secondary.html

- Government of Canada. (2022b, January 11). Education in canada: Types of schooling. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/new-immigrants/new-life-canada/education/types-school.html

- Graber, R., Turner, R., & Madill, A. (2016). Best friends and better coping: Facilitating psychological resilience through boys’ and girls’ closest friendships. British Journal of Psychology, 107(2), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12135

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1230

- Hanewald, R. (2013). Transition between primary and secondary school: Why it is important and how it can be supported. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n1.7

- Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

- Heinsch, M., Agllias, K., Sampson, D., Howard, A., Blakemore, T., & Cootes, H. (2020). Peer connectedness during the transition to secondary school: A collaborative opportunity for education and social work. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47(2), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00335-1

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool MMAT (Version 2018). mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpubliclicensedfornon-commercialuseonlyDownloadtheMMAT

- Hughes, L. A., Banks, P., & Terras, M. M. (2013). Secondary school transition for children with special educational needs: A literature review. Support for Learning, 28(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12012

- Hurst, C. S., Baranik, L. E., & Daniel, F. (2013). College student stressors: A review of the qualitative research. Stress & Health, 29(4), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2465

- Hysing, M., Petrie, K. J., Bøe, T., Lønning, K. J., & Sivertsen, B. (2020). Only the lonely: A study of loneliness among university students in Norway. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 2(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.32872/cpe.v2i1.2781

- Jaud, J., Görig, T., Konkel, T., & Diehl, K. (2023). Loneliness in University students during two transitions: A mixed methods approach including biographical mapping. International Journal Of, 20(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043334

- Jindal-Snape, D. (2016). A-Z of transitions. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Jindal-Snape, D. (2023). Multiple and multi-dimensional educational and life transitions: conceptualization, theorization and XII pillars of transitions. International Encyclopedia of Education, 4(6), 530–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818630-5.14060-6

- Jindal-Snape, D., & Bagnall, C. (2023). A systematic literature review of child self-report measures of emotional wellbeing during primary to secondary school transitions. Assessment and Development Matters, 15(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsadm.2023.15.1.17

- Jindal-Snape, D., Hannah, E. F. S., Cantali, D., Barlow, W., & MacGillivray, S. (2020). Systematic literature review of primary-secondary transitions: International research. Review of Education, 8(2), 526–566. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3197

- Jindal-Snape, D., & Rienties, B. (2016). Multi-dimensional transitions of international students to higher education (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315680200

- Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., DE Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., DE Girolamo, G., Gluzman, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Kawakami, N., Karam, A., Levinson, D., Medina Mora, M. E., Oakley Browne, M. A., Posada-Villa, J., Stein, D. J., Adley Tsang, C. H. … Ustün, T. B. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the world health organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 6(3), 168–176. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2174588/

- Kingery, J. N., Erdley, C. A., & Marshall, K. C. (2011). Peer acceptance and friendship as predictors of early adolescents’ adjustment across the middle school transition. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 57(3), 215–243. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2011.0012

- Kirst, M., Mecredy, G., Borland, T., & Chaiton, M. (2014). Predictors of substance use among young adults transitioning away from high school: A narrative review. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(13), 1795–1807. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.933240

- Klaiber, P., Whillans, A. V., & Chen, F. S. (2018). Long-term health implications of students’ friendship formation during the transition to university. Applied Psychology Health and Well-Being, 10(2), 290–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12131

- Kralik, D., Visentin, K., & van Loon, A. (2006). Transition: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55(3), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03899.x

- Langenkamp, A. G. (2009). Following different pathways: Social integration, achievement, and the transition to high school. American Journal of Education, 116(1), 69–97. https://doi.org/10.1086/605101

- Lee, C., Dickson, D. A., Conley, C. S., & Holmbeck, G. N. (2014). A closer look at self-esteem, perceived social support, and coping strategy: A prospective study of depressive symptomatology across the transition to college. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 33(6), 560–585. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2014.33.6.560

- Lester, L., & Cross, D. (2015). The relationship between school climate and mental and emotional wellbeing over the transition from primary to secondary School. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences Elsevier BV, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13612-015-0037-8

- Lester, L., Cross, D., Dooley, J., & Shaw, T. (2013). Bullying victimisation and adolescents: Implications for school-based intervention programs. Australian Journal of Education, 57(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944113485835

- Lev Ari, L., & Shulman, S. (2012). Pathways of sleep, affect, and stress constellations during the first year of college: Transition difficulties of emerging adults. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2011.635196

- Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Marengo, D., & Settanni, M. (2016). Student-teacher relationships as a protective factor for school adjustment during the transition from middle to high School. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01988

- Luhmann, M., & Hawkley, L. C. (2016). Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest age. Developmental Psychology, 52(6), 943–959. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000117

- Lumivero. (2020). QSR International Pty Ltd. https://community.lumivero.com/s/nvivo-knowledge-base?language=en_US

- Maillet, M. A., & Grouzet, F. M. E. (2023). Understanding changes in eating behavior during the transition to university from a self-determination theory perspective: A systematic review. Journal of American College Health, 71(2), 422–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1891922

- Meleis, A. I. (2010). Transitions theory – middle range and situation specific theories in nursing research and practice. Springer Publishing Company. https://books.google.fi/books?id=TdLhXm5fpx8C&pg=PA78&lpg=PA78&dq=Loon+and+Kralik+2005+transition&source=bl&ots=7kMhwPSOK4&sig=ACfU3U2Abg5v-ga_z8unzC3MoylKkxQv-w&hl=fi&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj95OKgofn0AhUvQ_EDHTQPCCIQ6AF6BAgbEAM#v=onepage&q=Loon%20and%20Kralik%202005%20transition&f=false

- Metzner, F., Lok-Yan Wichmann, M., & Mays, D. (2020). Educational transition outcomes of children and adolescents with clinically relevant emotional or behavioural disorders: Results of a systematic review. British Journal of Special Education, 47(2), 230–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12310

- Mikal, J. P., Rice, R. E., Abeyta, A., & DeVilbiss, J. (2013). Transition, stress and computer-mediated social support. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), A40–A53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.012

- Morton, S., Mergler, A., & Boman, P. (2014). Managing the transition: The role of optimism and self-efficacy for first-year Australian university students. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 24(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2013.29

- Mumford, J., & Birchwood, J. (2021). Transition: A systematic review of literature exploring the experiences of pupils moving from primary to secondary school in the UK. International Journal of Personal, Social and Emotional Development, 39(4), 377–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2020.1855670

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., & Jordan, Z. (2018). What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

- Newman, B. M., Newman, O. R., Griffen, S., O’Connor, K., & Spas, J. (2007). The relationship of social support to depressive symptoms during the transition to high school. Adolescence, 42(167), 441–459. https://www.proquest.com/docview/195944573?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

- Ng-Knight, T., Shelton, K. H., Riglin, L., Frederickson, N., McManus, I. C., & Rice, F. (2019). ‘Best friends forever’? Friendship stability across school transition and associations with mental health and educational attainment. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12246

- Nguyen, T. V. T., Werner, K. M., & Soenens, B. (2019). Embracing me-time: Motivation for solitude during transition to college. Motivation and Emotion, 43(4), 571–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09759-9

- Nikitin, J., & Freund, A. M. (2017). Social motives predict loneliness during a developmental transition. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 76(4), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000201

- Nuske, H. J., McGhee Hassrick, E., Bronstein, B., Hauptman, L., Aponte, C., Levato, L., Stahmer, A., Mandell, D. S., Mundy, P., Kasari, C., & Smith, T. (2019). Broken bridges—new school transitions for students with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review on difficulties and strategies for success. Autism, 23(2), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318754529

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E. … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PloS Medicine, 18(3), e1003583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

- Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In S. Duck & R. Gilmour (Eds.), Personal relationships in disorder (pp. 31–56). Academic Press. https://peplau.psych.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/141/2017/07/Perlman-Peplau-81.pdf

- Pittman, L. D., & Richmond, A. (2008). University belonging, friendship quality, and psychological adjustment during the transition to college. The Journal of Experimental Education, 76(4), 343–362. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.76.4.343-362

- Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., Maes, M., & Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615568999

- Rahal, D., Fales, M. R., Haselton, M. G., Slavich, G. M., & Robles, T. F. (2021). Achieving status and reducing loneliness during the transition to college: The role of entitlement, intrasexual competitiveness, and dominance. Social Development, 31(3), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12569

- Rice, F., Ng-Knight, T., Riglin, L., Powell, V., Moore, G. F., McManus, I. C., Shelton, K. H., & Frederickson, N. (2021). Pupil mental health, concerns and expectations about secondary school as predictors of adjustment across the transition to secondary school: A longitudinal multi-informant study. School Mental Health, 13(2), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09415-z

- Ritchie, H., Samborska, V., Ahuja, N., Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2023). Global education. our world in data. https://ourworldindata.org/global-education?insight=the-gender-gap-in-school-attendance-has-closed-across-most-of-the-world#article-citation.

- Rönkä, A. R., Taanila, A., Rautio, A., & Sunnari, V. (2018). Multidimensional and fluctuating experiences of loneliness from childhood to young adulthood in Northern Finland. Advances in Life Course Research, 35, 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.01.003

- Schnepf, S. V., Boldrini, M., & Blaskó, Z. (2023). Adolescents’ loneliness in European schools: A multilevel exploration of school environment and individual factors. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16797-z

- Scholaro Database. (n.d.-a). Education system in Canada. https://www.scholaro.com/db/Countries/Canada/Education-System

- Scholaro Database. (n.d.-b). Education system in China. https://www.scholaro.com/db/countries/china/education-system

- Scholaro Database. (n.d.-c). Education system in Israel. https://www.scholaro.com/db/Countries/Israel/Education-System

- Schumacher, K. L., & Meleis, A. L. (1994). Transitions: A central concept in nursing. In A. I. Meleis (Ed.), Transitions theory: Middle-range and situation-specific theories in nursing research and practice (pp. 38–51). Springer publishing company.

- Shovestul, B., Han, J., Germine, L., Dodell-Feder, D., & Santana, G. L. (2020). Risk factors for loneliness: The high relative importance of age versus other factors. Public Library of Science One, 15(2), e0229087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229087

- Spencer, L., McGovern, R., & Kaner, E. (2020). A qualitative exploration of 14 to 17-year old adolescents’ views of early and preventative mental health support in schools. Journal of Public Health, 44(2), 363–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa214

- Sundqvist, A., & Hemberg, J. (2021). Adolescents’ and young adults’ experiences of loneliness and their thoughts about its alleviation. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 26(1), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2021.1908903

- Symonds, J. E., & Galton, M. (2014). Moving to the next school at age 10–14 years: An international review of psychological development at school transition. Review of Education, 2(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3021

- Terry, M. L., Leary, M. R., & Mehta, S. (2013). Self-compassion as a buffer against homesickness, depression, and dissatisfaction in the transition to college. Self and Identity, 12(3), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2012.667913

- Thomas, L., Briggs, P., Hart, A., & Kerrigan, F. (2017). Understanding social media and identity work in young people transitioning to university. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.021

- Thomas, L., Orme, E., & Kerrigan, F. (2020). Student loneliness: The role of social media through life transitions. Computers & Education, 146, 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103754

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO. (2014a). Education policy research series discussion document No. 5: Education systems in ASEAN+6 countries: A comparative analysis of selected educational issues (Report No. 6). https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/UNESCO_Education_Systems_in_Asia_Comparative_Analysis_2014.pdf

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO. (2014b). Higher Education in Asia: Expanding Out, Expanding Up: The Rise of Graduate Education and University Research. https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/higher-education-in-asia-expanding-out-expanding-up-2014-en.pdf