ABSTRACT

Employees who remain available for work outside regular work hours often experience strain and work–home conflicts. This study clusters employees in distinct availability types based on different aspects of unregulated extended work ability, which are contacting frequency, availability expectations and perceived legitimacy of availability. Moreover, we examined covariates of class membership and relationships with employees’ well-being. We used data from 17,410 employees who took part in a representative survey of the German working population. Latent class analysis with double cross-validation revealed three availability types. Satisfaction with work–life balance was higher and internal work–home interference was lower in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class and the “illegitimate available”-class. Members of the “illegitimate available”-class reported worse subjective health, more psychovegetative health complaints, and higher levels of exhaustion than members of the “legitimate available”-class and the “rarely available”-class. Several socio-demographic variables, job characteristics, and factors associated with boundary management predicted class membership. Overall, the study highlights the risks for employees’ well-being associated with unregulated extended work availability – particularly when it is perceived as illegitimate – and points towards implications on the individual, organisational, and political level that may help reduce and better manage extended work ability.

Modern communication technologies allow employees to be available anytime and anywhere (Berkowsky, Citation2013). Therefore, many employees remain connected with their job even outside working hours, blurring traditional boundaries between work and home domains. While this newly acquired flexibility can offer advantages to both organisations and employees (e.g. O’Driscoll et al., Citation2010), the drawbacks of unregulated extended work availability have also found their way into public and political debates. For instance, Volkswagen made it into the news when agreeing to shut down e-mail delivery to blackberry phones after work hours for parts of the workforce (e.g. BBC News, Citation2012). Moreover, France has introduced a law, entitled by the press as “the right to disconnect” (The Guardian, Citation2016). It obliges organisations with more than 50 employees to negotiate new guidelines for handling after-work e-mails. Just recently, in light of the COVID-19 crisis with many employees facing increased availability demands when working from home, the European Parliament passed a resolution on the right to disconnect (European Parliament, Citation2021). It calls for minimum legal standards concerning availability that ensure employees’ health and work–life balance. In the European Union, working during off-hours can clash with minimum daily rest periods of eleven consecutive hours, as regulated in the Working Time Directive (Directive Citation2003/Citation88/EC). Therefore, unregulated extended work availability also raises labour law-related questions concerning its legality (e.g. Körlings, Citation2019).

Furthermore, a substantial body of literature provides empirical support for extended work availability being a serious stressor in our modern world of work. For instance, studies have revealed associations between extended work availability and a lack of psychological detachment, sleep disturbances, health problems, a higher absence risk, negative affect, perceived stress, exhaustion, burnout, and work–home conflicts (e.g. Arlinghaus & Nachreiner, Citation2013; Day et al., Citation2012; Derks et al., Citation2014; Derks & Bakker, Citation2014; Dettmers, Citation2017; Glavin & Schieman, Citation2012; Lutz et al., Citation2020; Schieman & Young, Citation2010; Voydanoff, Citation2005).

Furthermore, there is some evidence that beyond different personal characteristics and boundary conditions (Pangert et al., Citation2016) the extent to which extended work availability is considered a legitimate or illegitimate task (see also Semmer et al., Citation2015) can play a role for employees’ reactions. For instance, while some employees perceive availability during after-hours mainly as an invasion of spaces and times that are normally reserved for private life and recreation, others consider it a necessary and reasonable part of their job. In support of this, Dettmers and Biemelt (Citation2018) found that extended work availability as well as low perceived necessity of availability were related to increased exhaustion. Although this study employed only a relatively small convenience sample of employees, its findings suggest that employees might differ in their extent to which they perceive availability as legitimate and how they respond to availability demands. Evidence from a qualitative study by Menz et al. (Citation2019) further suggests that employees can be classified according to their appraisal of availability demands and their boundary management, that is the way employees negotiate and structure borders between work and private life (Kreiner et al., Citation2009).

In the present study, we build on this line of research by conducting a latent class analysis among a representative sample of the German work force to identify groups of employees that feature certain aspects of unregulated extended work availability. To this end, we examine availability demands (contacting frequency and availability expectations) and perceived legitimacy of availability (necessity and reasonableness). Furthermore, we search for factors that explain class membership, and we analyse relationships of these availability types with indicators of work–life balance, strain, and health. Thereby, we make several important contributions:

First, linking literature on extended work availability with theorising on illegitimate tasks (Semmer et al., Citation2007, Citation2015) by means of latent class analysis, we develop an intuitive taxonomy of availability types. By shedding light on the interplay of both availability demands and availability legitimacy, this classification adds to a more holistic understanding of unregulated extended work availability. Second, by relating the identified availability types to different outcomes in terms of work–life balance, strain, and health, we contribute to clarifying the link with employees’ well-being. The gained knowledge about risk groups provides guidance for handling availability demands on the individual, organisational, and political level. As a final point, we investigate unregulated extended work availability using a large-scale sample of both blue- and white-collar workers that is representative of most of the German working population, covering all branches and manifold jobs. Thus, the insights gained in this study are highly generalisable and support a consolidated understanding of unregulated extended work availability.

Availability demands and legitimacy

Particularly modern communication technologies have contributed to availability demands by enabling employees to remain connected with work anytime and anywhere, permeating traditional boundaries between work and private life (Berkowsky, Citation2013). In line with Dettmers and Biemelt (Citation2018), we define extended work availability as a “condition in which employees are flexibly accessible to supervisors, coworkers, or customers during off-job time and are either explicitly or implicitly required to respond to work requests.” This comprises both contacting frequency, that is how often employees are contacted for work issues in private life, and perceived availability expectations, that is the extent to which employees feel that their work environments expects them to be available for work-related issues outside regular work hours. In the present study, we focus on unregulated forms of extended work availability (cf., Pangert et al., Citation2016) in contrast to regulated and more formalised forms. Due to the strict regulatory framework for formal “on-call duty” (i.e. emergency service) and “on-call at home” in Germany (Jaehrling & Kalina, Citation2020), these legally and contractually regulated (including implications for work hours, payment, etc.) forms of extended work availability can be viewed as qualitatively distinct from unregulated extended work availability. This might influence perceptions of legitimacy, both among employers and employees.

Like other job tasks (Semmer et al., Citation2007), availability demands may be perceived as illegitimate if employees’ norms of appropriate job requirements are violated. Literature on illegitimate tasks distinguishes between two facets, namely unreasonable and unnecessary tasks (Semmer et al., Citation2015). Despite only focusing on unnecessary availability, Dettmers and Biemelt’s (Citation2018) findings highlight that considering perceived availability illegitimacy can contribute to a better understanding of extended work availability.

Previous qualitative (Menz et al., Citation2019) and quantitative (Kossek et al., Citation2012) studies showed that employees can be clustered into distinct boundary management types. Such classification approaches may augment our knowledge by revealing patterns undetected by linear and interaction models. In the present study, we aim to classify employees based on their availability demands and perceived availability legitimacy and quantify the prevalence of these availability types in the working population in Germany.

Thus, we take an exploratory approach by asking Research Question 1: Can employees be clustered into distinct and meaningful availability types (latent classes) based on their availability demands and perceived availability legitimacy?

Covariates of availability types

To gain further insights about characteristics of the different classes and potential confounders in the relationships with well-being, we examine covariates of availability types. In terms of demographic variables, we focus on gender, age, and educational level to describe the composition of the availability types. In Germany, the male breadwinner model with women engaging less in full-time employment is still very common (Trappe et al., 2015), suggesting that the significance of and time investment for paid work is higher among men than women. In line with this, previous research has shown that men are more often confronted with availability expectations (Hobler et al., Citation2020) and contacted outside regular work hours than women (Arlinghaus & Nachreiner, Citation2013). Moreover, it can be assumed that younger employees – often referred to as “digital natives” – are accustomed to being constantly online and available (Strobel, Citation2013) because they have grown up with modern information and communication technology (ICT). Because knowledge and skills of highly qualified employees might be required more often also during nonwork times, a higher educational level could be associated with higher availability demands as well. In support of this, a higher socio-economic status has been shown to be related to higher contacting frequency (Arlinghaus & Nachreiner, Citation2014). With regard to job characteristics, we consider whether employees have an office job because this could facilitate use of ICT from home. Similarly, in a study by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs in Germany (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, Citation2015) white-collar workers reported more often than blue-collar workers that modern ICT turned their leisure time into work time. Moreover, we examine employees’ income because this could not only entail higher availability expectations but it could – in correspondence with the effort-reward imbalance model (Siegrist, Citation1996) – also serve as a reward and increase perceived availability legitimacy. Similarly, employees in a leading position and self-employed persons (as compared to employees in dependent employment) might face more availability demands. In support of this, higher levels of managerial responsibility have been found to be related to more intrusions of nonwork time by modern ICT (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, Citation2015). Moreover, high responsibility for employees and business outcomes might also come along with a higher perceived availability legitimacy. Furthermore, we include weekly working hours as a covariate because this could reflect a general extension of work into leisure time and a higher workload. In line with this, Arlinghaus and Nachreiner (Citation2013) reported that employees with longer working hours were more frequently contacted during nonwork time. With regard to boundary management, we examine whether employees are frequently contacted during working hours for private matters because this could suggest a generally higher permeability of the work–home boundary as well as a higher perceived availability legitimacy since intrusions also occur within the work domain. Finally, we include segmentation preference – the extent to which employees favour a separation (vs. integration) of work and private life – because boundary management styles may affect the way employees perceive and handle availability demands (Menz et al., Citation2019). Supporting this notion, a higher segmentation preference has been associated with less ICT use during nonwork time (Schlachter et al., Citation2018).

Thus, searching for factors relevant to the composition of latent classes, we formulate Research Question 2: Which covariates are related to different availability types?

Relationships with employees’ well-being

To enhance our understanding of the effects of unregulated extended work availability on employees’ well-being, we examine aspects related to employees’ work–life balance (satisfaction with work–life balance, internal work–home interference) and indicators pertaining to employees’ physical and mental health (subjective health, psychovegetative health complaints), and strain (exhaustion).

According to boundary and border theory (Ashforth et al., Citation2000; Clark, Citation2000), work and private life are separated through temporal, physical and psychological boundaries that can be more or less flexible and permeable. Work–life balance can be achieved in case of “satisfaction and good functioning at work and at home, with a minimum of role conflict” (Clark, Citation2000, p. 751). Extended work availability, however, can blur the boundaries between the work and home domains. Such intrusions of private life can manifest themselves in internal work–home interference, that is mental or behavioural preoccupation with work outside work hours (Carlson & Frone, Citation2003). This can be psychologically demanding and lead to role conflicts (e.g. Hecht & Allen, Citation2009). In line with this, studies have linked extended work availability with increased work–home conflicts and lower satisfaction with work–life balance (Glavin & Schieman, Citation2012).

Furthermore, effort-recovery theory (Meijman & Mulder, Citation1998) suggests that recovery processes may remain incomplete in case of extended work availability. According to this theory, psycho-physiological systems that are activated during work can only return to their normal baseline level in the absence of work demands. In addition to the job demands encountered during regular working hours, work-related e-mails or phone calls after hours may confront employees with additional work demands such as workload or time pressure. Extended work availability hence prolongs the time employees are exposed to work demands, drawing on the same functional systems that are activated during the working day. Furthermore, the sole anticipation of availability may keep functional systems activated: Studies on on-call work (e.g. Bamberg et al., Citation2012) found that the mere possibility of being called was associated with impaired well-being regardless of whether employees were actually contacted. In the long run, the sustained activation can then result in exhaustion (Demerouti et al., Citation2010) and chronic or even irreversible impairments of health (Geurts & Sonnentag, Citation2006). In line with this, several studies found that extended work availability hampered central recovery experiences such as mental detachment and associated extended work availability with increased levels of exhaustion (e.g. Derks et al., Citation2014; Derks & Bakker, Citation2014; Dettmers, Citation2017).

In addition to availability demands, perceived availability legitimacy can have effects on employees’ well-being. If employees perceive availability as unnecessary, they doubt whether there is a justifiable need to be available or question whether a better work organisation could have solved this problem (Dettmers & Biemelt, Citation2018). Similarly, if employees perceive availability as unreasonable, they feel that they are required to remain available although this goes beyond what can be expected from them. Both facets of perceived availability illegitimacy can pose a potential threat to employees’ well-being. According to the stress-as-offense-to-self approach (Semmer et al., Citation2007), illegitimate tasks convey subtle signs of disrespect that assault the self and elicit stress responses (Semmer et al., Citation2015). Employees who perceive availability as illegitimate might view it as an invasion of their private life, paired with the implicit message that their private time is not considered important and worth respecting, which may cause strain reactions (Dettmers & Biemelt, Citation2018). Overall, this suggests that perceived availability legitimacy is likely to play a role for different aspects of employees’ well-being.

Based on these considerations, we examine Research Question 3: How do availability types relate to employees’ satisfaction with work–life balance, internal work–home interference, subjective health, psychovegetative health complaints, and exhaustion?

Method

Sample and procedures

Data from the BAuA-working time survey 2015 (Brauner et al., Citation2019; Wöhrmann et al., Citation2020), a nationally representative survey of the German working population was the basis of the present study. About 20,000 employees took part in computer-assisted telephone interviews carried out by professional interviewers of a social science research institute (Häring et al., Citation2016). A random sample was generated through landline and mobile phone numbers. Participants were considered eligible if they were aged 15 years and older and worked at least ten hours per week in a paid job. Thus, employees of all age and educational groups across various economic branches and manifold jobs took part in the survey. The interviews lasted 35 min on average and covered a broad range of topics related to work and well-being with a focus on aspects related to working time.

For the present study, we used data from 17,410 employees aged 15 years and older. To avoid possible confounding effects with unregulated extended work availability we excluded employees who indicated that their job involved on-call duty or emergency services. Men and women were equally represented in the sample and the mean age was 46 years. According to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 2011: UNESCO, Citation2012), 2% had a low and 49% had a medium educational level, while 48% had received higher education. Twenty-eight per cent of the participants worked in the public sector, 31% in the service sector, 21% in industry, 9% in the craft sector, and 7% in another sector. Thirteen per cent described themselves as blue-collar workers, 69% indicated they were white-collar workers, 8% were civil servants, 7% were self-employed, and 3% were freelancers or family workers.

Measurement

Some categories of the included indicators of availability demands and perceived availability legitimacy were only endorsed by few individuals resulting in multiple occurrences of sparse response patterns and potentially increasing the number of boundary parameter estimates, meaning probabilities set to 0 or 1 (Galindo-Garre & Vermunt, Citation2006; Wurpts & Geiser, Citation2014). As the cumulation of boundary parameter estimates can result in numerical problems in the latent class estimation algorithm (Vermunt & Magidson, Citation2004), we dichotomised indicator variables. This also allowed for a more parsimonious and comprehensible latent class model (see also Quirk et al., Citation2013; Stapinski et al., Citation2016).

Availability expectations were measured with the self-constructed item “My work environment expects me to be available for work-related matters in my private life” and a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 5 (applies completely). Employees choosing categories 4 and 5 were considered to face high availability expectations. Contacting frequency was assessed with the item “How often are you contacted by colleagues, supervisors or customers in your private life?” Perceived necessity of unregulated extended work availability was measured with the item “How often do you think it is necessary to be available for work-related matters in your free time?” Perceived reasonableness of unregulated extended work availability was assessed with the item “How often do you personally think it is reasonable to be available for work-related matters in your free time?” For these three items response options were frequently, sometimes, seldom and never, with participants choosing frequently being considered to experience a high contacting frequency, high necessity and high reasonableness, respectively.

Internal work–home interference was measured with a 3-item scale by Carlson and Frone (Citation2003). A sample item is “When I am at home, I often think about things I need to accomplish at work.” The participants responded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (does not apply at all) to 5 (applies completely). In the current study, the scale showed a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .81). Satisfaction with work–life balance was measured with the item “How satisfied are you with the fit between your work and private life?” (Valcour, Citation2007). Participants could answer on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (not satisfied) to 4 (very satisfied). Moreover, we measured subjective health with the item “How would you describe your general health status?” Participants could respond on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very bad) to 5 (very good). In line with Lohmann-Haislah (Citation2012), we built an index to measure psychovegetative complaints. Participants indicated whether insomnia, fatigue, irritability, and dejection occurred frequently during the last twelve months at work or on workdays and their positive answers were summed up. Exhaustion was assessed with four items from the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti et al., Citation2010), for example, “There are days when I feel tired before I arrive at work.” The participants responded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (does not apply at all) to 5 (applies completely). In the current study, the scale showed an acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .74).

Covariates. As covariates, we considered demographic characteristics, namely age (in years), gender (0 = male, 1 = female), and education (0 = low, 1 = medium, 2 = high, according to ISCED, 2011). Moreover, we examined whether employees had a high monthly gross income (0 = below 5000 €, 1 = above 5000 €), an office job (no = 0, yes = 1), a leading position (no = 0, yes = 1), whether they were engaged in dependent employment as opposed to self-employment (self-employed = 0, dependently employed = 1) and employees’ weekly working hours (continuous; number of hours actually worked per week). Frequent contacting during working hours for private matters (never, seldom, sometimes = 0, frequently = 1) was measured with the item “How often are you contacted by family, friends or other persons for nonwork-related reasons at work?” Furthermore, we assessed employees’ segmentation preference, with three items, for instance, “It is important for me to not have to think about work while I am at home.” Employees could respond on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 5 (applies completely). The scale showed a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .84).

Analyses

We used Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2015) for the statistical analyses. To identify unobserved types of employees regarding extended work availability (RQ1) we conducted latent class analyses. As part of finite mixture models, they allow identifying homogeneous unobserved subgroups among a heterogeneous population (Masyn, Citation2013). Members of one latent class share a distinctive profile on a number of manifest indicator variables. For parameter estimation, we used maximum likelihood estimators with robust standard errors. The number of latent classes is determined by comparing solutions with an increasing number of latent classes. Besides interpretability of the class solutions, we considered several information-based fit indices, namely Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz, Citation1978) and sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SSBIC; Sclove, Citation1987), as well as relative fit indices, namely adjusted Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (aLMR; Lo et al., Citation2001), and bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT; McLachlan & Peel, Citation2000). Moreover, in terms of classification diagnostics, we also examined relative entropy (Ramaswamy et al., Citation1993) and average posterior class probability (AvePP) to evaluate class separation and classification precision. We refrained from assessing absolute model fit with the likelihood ratio chi-squared statistic because this test is extremely sensitive in large samples such as ours, revealing even negligible misfit (Masyn, Citation2013). To detect violations of the local independence assumption, we inspected bivariate residuals using bivariate Pearson testing (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2015a).

We used double cross-validation to evaluate the replicability of the retrieved class structure. For this purpose, we randomly split the sample in two halves, calculated exploratory latent class analyses in each half and validated the best fitting models in the other half of the sample, respectively. To compare the fit of the exploratory model with the constrained model with fixed parameters (item thresholds and latent class means), we conducted likelihood ratio chi-square difference tests.

We had to decide against analysing associations between confounders and distal outcome variables after encountering convergence issues using the manual ML three-step and manual BCH approach as implemented in Mplus (Nylund-Gibson et al., Citation2019). Instead, we examined associations between the latent classes and covariates and distal outcomes separately:

To determine potential antecedents of class membership (RQ2), we included covariates in the model with the automated ML three-step approach as recommended by Asparouhov and Muthén (Citation2015b). We calculated multinomial logistic regressions of employees’ most likely class memberships on gender, age, educational level, income, office job, leading position, weekly working hours, dependent employment, contacting during working hours for private matters, and segmentation preference by controlling for measurement error in modal assignment (Vermunt, Citation2010). Then, we translated the obtained logit parameters into odds ratios.

For relating class membership with distal outcome variables (RQ3), we employed Lanza’s method (Lanza et al., Citation2013) as implemented in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2015) in both sample halves. Within this stepwise approach, the latent class model is estimated only based on the latent class indicators in the first step. Then the conditional distribution of outcome variables (binary, continuous or count variables) given the latent class variable is estimated by applying Bayes’ Theorem. An advantage of this method is that the distal outcome cannot drastically influence individual’s class membership and meaning of the latent class solution, making it more robust for practical applications than three-step methods (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014). However, it does not allow for the inclusion of latent class predictors. Mplus provides an overall Wald’s test of the association between the latent class and distal outcome variables along with pairwise class comparisons.

Results

A correlation matrix can be obtained from the authors upon request. In the following, we will attend to the three research questions outlined above.

Availability types (RQ1)

Model selection criteria (see ) pointed towards a three-class model in both halves, which also convinced by a high interpretation clarity. The four-class solution was not identified in neither half. BIC and SSBIC decreased from the one- to the three-class solution, with lower values indicating better model fit. In both halves, the aLMR test and the BLRT were significant for the two- and three-class models, pointing towards a better model fit of the model with one additional class as compared to the neighbouring class model (Masyn, Citation2013). Class separation was good for the two- and three-class model, with relative entropies for all classes >0.6 (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014), but was slightly higher for the three-class solution. Classification precision was satisfactory for the two-class model in Half 1 and the two- and three-class model in Half 2, with AvePP ≥ .70 (Nagin, Citation2005), but slightly below the rule of thumb introduced by Nagin (Citation2005) for the three-class model in Half 1 (AvePP ≥ .69). In terms of interpretability, the two-class solution only distinguished between a class with relatively high availability demands and a class with low availability demands. The three-class solution, however, in both halves revealed one class with relatively high availability demands and low perceived legitimacy, one class with relatively high availability demands and relatively high perceived legitimacy and one class with low availability demands and low perceived legitimacy. Therefore, we rated meaningfulness higher for the three-class model. Because most model selection criteria also pointed towards the three-class solution, we decided in favour of the three-class solution.

Table 1. Model fit information for exploratory latent class analyses and double cross-validation in split-half samples.

provides the bivariate residuals from the initial and three-class model. Non-significant Pearson tests for the three-class model gave no indication of bivariate misfit, suggesting that the assumption of local independence holds in both halves.

Table 2. Bivariate Pearson Chi-square standardised residuals.

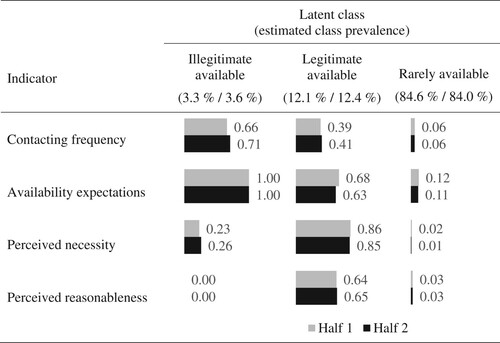

With regard to the double cross-validation, chi-square likelihood ratio difference tests showed that constraining parameters to equality in both halves decreased model fit. However, because these tests are highly sensitive to sample size, they tend to overestimate misfit in large samples. The similar conditional probabilities for the indicators of availability demands and perceived legitimacy in both halves, however, are indicative of the robustness of the identified three-class solution (see ).

Figure 1. Conditional probabilities for item endorsement and class prevalence (Half 1/Half 2) of the three-class model.

We labelled the three classes based on the respective response patterns. Class 1 (“illegitimate available”) is the smallest cluster (3–4% of sample halves). Its members can be characterised by a relatively high probability of frequent contacting and they all report high availability expectations. On the other hand, they have a relatively low probability of perceiving availability as necessary and they do not perceive availability as reasonable.

Class 2 (“legitimate available”) is the second-largest cluster (12% of sample halves). This class features a moderate probability of frequent contacting and a relatively high probability of experiencing high availability expectations. Furthermore, members of this class have a relatively high probability of perceiving availability as necessary and reasonable.

Class 3 (“rarely available”) is the largest cluster with the majority of employees (84–85% of sample halves). Members of this class have low probabilities of scoring on any of the four indicator variables related to availability demands and perceived availability legitimacy.

Covariates of class membership (RQ2)

shows the results of the multinomial regression analysis with covariates as predictors of class membership. The following significant associations between class membership and covariates were found: Women had higher odds than men, and older employees had lower odds than younger employees of being in the “illegitimate available”-class than in the “legitimate available” – or “rarely available”-class. Employees with a higher educational level had higher odds of being in the “illegitimate available”-class than in the “rarely available”-class in Half 1 and lower odds of being in the “rarely available” class than in the “legitimate available”-class in Half 2. Employees with an income above 5000 € per month had lower odds of being in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class. Employees with an office job had lower odds of being in the “illegitimate available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class in Half 2. Moreover, they had lower odds of being in the “illegitimate available” class than in the “rarely available”-class and higher odds of being in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class in both halves. Employees in a leading position had lower odds of being in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class or “illegitimate available”-class. Employees with longer weekly working hours had higher odds of being in the “illegitimate available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class or “rarely available”-class and lower odds of being in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class. Dependent employees had higher odds of being in the “illegitimate available”-class and in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class and lower odds of being in the “illegitimate available”-class than in the “rarely available”-class. Those who are frequently contacted during working hours for private matters had lower odds of being in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class. Moreover, in Half 1 but not in Half 2 they had lower odds of being in “rarely available”-class than in the “illegitimate available”-class. Employees with a higher segmentation preference had higher odds of being in the “illegitimate available”-class and in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class.

Table 3. Multinomial regression results of class membership on covariates.

Associations with well-being (RQ3)

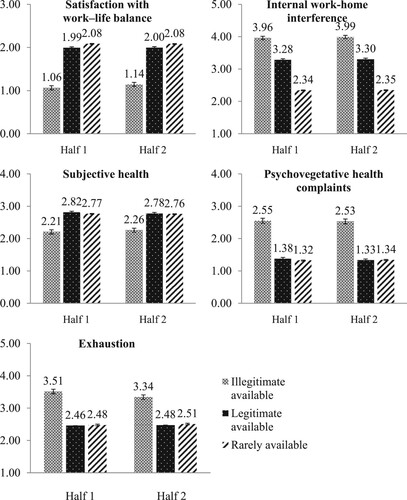

displays the class-specific means and approximate standard errors estimated using the Lanza-method in Halves 1 and 2.

Figure 2. Estimated class-specific means and standard errors on outcome variables. Error bars represent standard errors.

With regard to satisfaction with work–life balance, analyses revealed significant differences between latent classes (Half 1: χ² (2) = 427.10, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (2) = 389.11, p < .001). The “rarely available”-class had a significantly higher satisfaction with work–life balance than the “legitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 12.99, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 11.13, p = .001) and the “illegitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 421.55, p < .001; Half 1: χ² (1) = 384.11, p < .001). Moreover, the “legitimate available”-class had a significantly higher satisfaction with work–life balance than the “illegitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 287.90, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 260.05, p < .001).

In terms of internal work–home interference, we also found significant class differences (Half 1: χ² (2) = 1471.15, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (2) = 1616.76, p < .001). The “rarely available”-class reported a significantly lower internal work–home interference than the “legitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 649.84, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 680.21, p < .001) and the “illegitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 929.268, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 1064.62, p < .001). Furthermore, the “legitimate available”-class experienced significantly lower internal work–home interference than the “illegitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 117.69, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 132.84, p < .001).

Latent classes also differed significantly in their subjective health (Half 1: χ² (2) = 76.52, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (2) = 66.60, p < .001). Members of the “illegitimate available”-class had a significantly lower health score than members of the “legitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 72.50, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 59.43, p < .001) and members of the “rarely available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 72.38, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 64.67 p < .001). However, the “legitimate available”-class and the “rarely available”-class did not differ significantly from each other (Half 1: χ² (1) = 2.25, p = .13; Half 2: χ² (1) = 0.54, p = .46).

Analyses also showed significant class differences in terms of psychovegetative health complaints (Half 1: χ² (2) = 247.09, p < .001 Half 2: χ² (2) = 250.57, p < .001). Members of the “illegitimate available”-class reported significantly more psychovegetative health complaints than members of the “legitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 181.34, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 202.65, p < .001) and members of the “rarely available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 247.07, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 248.52, p < .001). The “legitimate available”-class and the “rarely available”-class did not differ significantly in their number of psychovegetative health complaints (Half 1: χ² (1) = 1.50, p = .22; Half 2: χ² (1) = 0.07, p = .80).

A similar result pattern was found for exhaustion (Half 1: χ² (2) = 492.66, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (2) = 291.51, p < .001). Members of the “illegitimate available”-class experienced significantly more exhaustion than members of the “legitimate available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 385.37, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 241.47, p < .001) and members of the “rarely available”-class (Half 1: χ² (1) = 486.31, p < .001; Half 2: χ² (1) = 285.78, p < .001). The “legitimate available”-class and the “rarely available”-class scored comparably high on exhaustion (Half 1: χ² (1) = 0.48, p = .49; Half 2: χ² (1) = 1.14, p = .29).

Discussion

Against the backdrop of an intensified blurring of work–home boundaries, this study aimed at identifying and describing availability types and linking these with different aspects of employees’ well-being. Our findings advance the literature on extended work availability in several ways:

First, integrating literature on extended work availability and illegitimate tasks, latent class analysis revealed a meaningful and tangible taxonomy consisting of three availability types: The “illegitimate available”-class, consisting of only three to four per cent of employees, is characterised by high availability demands in terms of contacting and availability expectations but low perceived availability legitimacy. Twelve per cent of employees belong to the “legitimate available”-class, which features moderate contacting frequency, high availability expectations, and high perceived necessity and reasonableness of availability. The majority of employees (84–85%) are members of the “rarely available”-class and neither have high availability demands nor high perceived availability legitimacy. The current study, therefore, provides a glimpse of the nature of unregulated extended work availability in Germany before the COVID-19 crisis with one-sixth of a nationally representative sample of employees belonging to a group with high availability demands and a relatively low share perceiving these demands as illegitimate. Most employees, however, only reported low-intensity or no availability demands at all. Overall, this quantification objectivises the discussion concerning accelerating unregulated extended work availability. Other representative studies in the EU and Germany before the COVID-19 crisis provide slightly differing estimates of availability demands, mostly based on single indicators. Twenty-two per cent of employees throughout Europe reported being contacted outside regular work hours at least a couple of times a month (Arlinghaus & Nachreiner, Citation2013). In Germany, 17% of employees endorsed the statement that modern ICT often turn their leisure time into work time (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, Citation2015). Extended work availability is particularly pronounced among white-collar workers in Germany, with four out of ten white-collar workers reporting work-related ICT use outside regular work hours at least a couple of times a month (Arnold et al., Citation2015). However, it remains to be seen how sustainably the COVID-19 crisis and the associated telework boom (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Citation2020) will alter our world of work and the nature of extended work availability. The present study represents a useful starting point for future classification and taxonomical approaches by depicting a pre-pandemic status quo.

Second, our analyses revealed important insights into the composition of the three availability types. For instance, women compared to men and younger compared to older employees were more likely to be in the “illegitimate available”-class than in the other classes. Explanations could be that female employees in Germany often have a dual burden including more unpaid work in the household or taking care of children or elder relatives (Adema et al., Citation2017), and younger generations might be more watchful to threats to their work–life balance (e.g. Kasch et al., Citation2015). Results concerning educational level differed across sample halves, not allowing for a straightforward conclusion. However, a high income increased the likelihood of being in the “legitimate available”-class compared to the “rarely available”-class. The health-protecting influence of an associated high socio-economic status (e.g. Adler et al., Citation1993; Sekine et al., Citation2009), might have concealed health and strain differences between these two groups. Furthermore, employees in a leading position were less likely to be in the “rarely available”-class, probably because their jobs involve a high responsibility and a high accessibility for their team members. Employees in office jobs had a higher probability of being in the “rarely available”-class than the other classes. This implies that the extensive study of knowledge workers within the field of extended work availability (Ticona, Citation2015) might not be sufficient to gain a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon and its consequences. Moreover, long working hours were associated with both the “illegitimate available”-class and the “legitimate available”-class, which suggests that extended work availability often prolongs regular working hours. Not surprisingly, self-employed persons as compared to dependent employees had a higher likelihood of being in the “legitimate available”-class than in the “illegitimate available”-class or the “rarely available”-class, probably because they are responsible for their own business success and many of them also for the people they employ. Furthermore, frequent contacting during working hours for private matters was related to a lower probability of being in the “rarely available”-class than in the “legitimate available”-class which suggests a higher boundary permeability among these employees. Nevertheless, contacting during working hours for private matters did not increase the likelihood of being in the “legitimate available”-class as compared to the “illegitimate available”-class, which indicates that contacting for private matters at work might neither compensate for unregulated extended work availability nor increase its perceived legitimacy. A lower segmentation preference, on the other hand, made it more likely to be in the “legitimate available”-class than in other classes. In summary, these results reveal that extended work availability should be viewed in concert with socio-demographic factors, job characteristics, and other aspects of boundary management to arrive at a more holistic picture of this phenomenon.

Third, linking the extracted availability types with indicators of well-being highlighted that the “illegitimate available”-class is a risk group that showed alarming relationships with regard to satisfaction with work–life balance, internal work–home interference, psychovegetative health complaints, subjective health, and exhaustion. Although the “legitimate available”-class also had problems in terms of satisfaction with work–life balance and internal work–home interference, they reported health and strain values comparable to those of the “rarely available”-class. The higher availability demands among the “illegitimate available”-class compared to the “legitimate available”-class could also indicate that these availability demands were too high or unpredictable and thus overtaxed employees resulting in health impairments and strain. Overall, these findings suggest that extended work availability can pose a risk not only to employees’ work–home interface but also to strain and long-term health outcomes, particularly among employees who perceive it as illegitimate.

Most importantly, the use of a nationally representative large-scale sample covering a broad range of industries and occupations provides highly generalisable results that may inform organisational and political decision making. Thereby, we overcome limitations of previous studies that often focus on white-collar workers in selected professions or economic branches.

Study limitations and avenues for future research

Several limitations of the present study have to be acknowledged. In our analyses, we could not control for the influence of confounding covariates on distal well-being outcome variables, as the manual ML three-step or BCH approach would allow (e.g. Nylund-Gibson et al., Citation2019). This might have led to biased results. For example, the higher share of females in the “illegitimate available”-class might have deflated well-being scores. On the other hand, the higher proportion of younger workers in the “illegitimate available”-class and the lower proportion of employees with a high income among the “rarely available”-class might have inflated well-being scores. This might have concealed effects of unregulated extended work availability among the “legitimate available”-class. Thus, future research could examine whether there are health and strain differences between legitimately and illegitimately available employees when controlling for socio-demographic and job characteristics.

Due to the dichotomisation of the examined indicators of availability demands and perceived availability legitimacy not all available information was used for model building. We nonetheless adopted this approach to allow for a computable solution that can be easily and intuitively interpreted. Notwithstanding, the inclusion of binary indicators still allowed us to focus on pronounced and frequent availability demands and their relations with employees’ well-being.

A further limitation is that we relied completely on self-report measures, which may raise concerns about common-method variance (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). However, as many of our constructs are inner states, we believe that in these cases self-report is the means of choice. Nevertheless, it could be a promising approach to complement self-report measures with objective data on health, strain, and availability.

Since our analyses were based on cross-sectional data, we cannot draw causal conclusions. To explore the direction of relationships, diary studies are essential. However, thanks to the large and representative sample of blue- and white-collar workers of a wide range of industries and occupations, the results of our field study can be generalised to a large part of the German working population.

Implications for practice

From a practical point of view, this study shows that unregulated extended work availability may pose risk to employees’ well-being. Employees belonging to availability types with high availability demands showed impairments of work–life balance that were strongest among employees who perceived availability as illegitimate. In terms of health and strain, the results do not warrant the assumption of the harmlessness of extended work availability if it is perceived as legitimate because the comparable health and strain scores of the “legitimate available”-class and the “rarely available”-class could partially be attributed to pre-existing group differences. To be on the safe side, extended work availability should be reduced, regulated, and limited to necessary and reasonable emergency cases. This may include approaches on the individual, organisational, and political level.

Based on interviews with experts, Strobel (Citation2013) proposed some measures suitable for individual employees, for instance, a conscious management of one’s leisure time, creating times and spaces of “unavailability,” not offering availability of one’s own record, or calling for collective regulations on the company level. In line with these suggestions, many researchers (e.g. Kreiner et al., Citation2009; Michel et al., Citation2014) have also stressed the role of individual boundary management strategies. These may help employees who face availability demands and who therefore search for ways to recover from work and to maintain a good work–life balance. Furthermore, supervisors may address the issue of unregulated extended work availability and should become aware of their function as role models.

In terms of organisational interventions, Strobel (Citation2013) proposed that organisations should develop transparent guidelines and rules on the company and team level and sensitise employees and supervisors. However, as Pangert et al. (Citation2016) pointed out, organisational policies and even technical barriers can easily and “voluntarily” be bypassed by employees. Reasons for this can be manifold, ranging from too ambitious organisational targets to employees’ fears of career disadvantages. Hence, potentially contradictory organisational and individual goals have to be considered in a comprehensive organisational and team culture for handling availability. Compensating times of availability (e.g. through compensatory time off, monetary compensations) could increase perceived availability legitimacy. Moreover, substitution in case of vacation or illness should be arranged. Furthermore, our results indicate that if availability outside working hours cannot be avoided there should be regular revisions in place to check if this practice is still necessary and reasonable.

Finally, working time acts that regulate rest periods and discussions concerning a “right to disconnect” (European Parliament, Citation2021) make extended work availability also a relevant political issue. The current study, along with a growing body of literature (e.g. Pangert et al., Citation2016), indicates that extended work availability might pose a threat to employees’ well-being. While representative longitudinal studies are still rare, the existing empirical evidence does not support the notion of the innocuousness of extended work availability. Thus, regulations should take into account employees’ health, strain, and work–life balance. Demands for abandoning or shortening rest periods should be treated with caution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adema, W., Clarke, C., Frey, V., Greulich, A., Kim, H., Rattenhuber, P., & Thévenon, O. (2017). Work/life balance policy in Germany: Promoting equal partnership in families. International Social Security Review, 70(2), 31–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/issr.12134

- Adler, N. E., Boyce, T. W., Chesney, M. A., Folkman, S., & Syme, S. L. (1993). Socioeconomic inequalities in health - no easy solution. Journal of the American Medical Association, 269(24), 3140–3145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1993.0350024008403

- Arlinghaus, A., & Nachreiner, F. (2013). When work calls – associations between being contacted outside of regular working hours for work-related matters and health. Chronobiology International, 30(9), 1197–1202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2013.800089

- Arlinghaus, A., & Nachreiner, F. (2014). Health effects of supplemental work from home in the European Union. Chronobiology International, 30(9), 1197–1202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2013.800089

- Arnold, D., Steffes, S., & Wolter, S. (2015). Monitor – mobiles und entgrenztes Arbeiten: Aktuelle Ergebnisse einer Betriebs- und Beschäftigtenbefragung [Monitor – mobile and boundaryless work: Latest results of a company and employee survey]. Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/148158/1/87261722X.pdf

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3363315

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2015a). Residual associations in latent class and latent transition analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.935844

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2015b, May 14). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Note: No. 21. http://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote21.pdf

- Bamberg, E., Dettmers, J., Funck, H., Krähe, B., & Vahle-Hinz, T. (2012). Effects of on-call work on well-being: Results of a daily survey. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 4(3), 299–320. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2012.01075.x

- BBC News. (2012, March 8). Volkswagen turns off blackberry email after work hours. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-16314901

- Berkowsky, R. W. (2013). When you just cannot get away: Exploring the use of information and communication technologies in facilitating negative work/home spillover. Information, Communication & Society, 16(4), 519–541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.772650

- Brauner, C., Vieten, L., Tornowski, M., Michel, A., & Wöhrmann, A. M. (2019). Datendokumentation des Scientific use Files der BAuA-Arbeitszeitbefragung 2015 [Data documentation of the scientific use file of the BAuA-working time survey 2015]. Dortmund: Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21934/baua:doku20190531

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales. (2015). Gewünschte und erlebte Arbeitsqualität: Abschlussbericht der repräsentativen Befragung [Preferred and experienced quality of work: Final report of the representative survey]. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/47122/ssoar-2015-Gewunschte_und_erlebte_Arbeitsqualitat_.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&lnkname=ssoar-2015-Gewunschte_und_erlebte_Arbeitsqualitat_pdf

- Carlson, D. S., & Frone, M. R. (2003). Relation of behavioral and psychological involvement to a new four-factor conceptualization of work–family interference. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(4), 515–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023404302295

- Clark, S. C. (2000). Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53(6), 747–770. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001

- Day, A., Paquet, S., Scott, N., & Hambley, L. (2012). Perceived information and communication technology (ICT) demands on employee outcomes: The moderating effect of organizational ICT support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17(4), 473–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029837

- Demerouti, E., Mostert, K., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Burnout and work engagement: A thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019408

- Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Smartphone use, work–home interference, and burnout: A diary study on the role of recovery. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 63(3), 411–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00530.x

- Derks, D., van Mierlo, H., & Schmitz, E. B. (2014). A diary study on work-related smartphone use, psychological detachment and exhaustion: Examining the role of the perceived segmentation norm. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035076

- Dettmers, J. (2017). How extended work availability affects well-being: The mediating roles of psychological detachment and work-family-conflict. Work & Stress, 31(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1298164

- Dettmers, J., & Biemelt, J. (2018). Always available – the role of perceived advantages and legitimacy. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(7/8), 497–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-02-2018-0095

- Directive 2003/88/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 November 2003 concerning certain aspects of the organisation of working time.

- European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. (2020). Living, working and COVID-19. First findings – April 2020. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef20058en.pdf

- European Parliament. (2021, January 21). European Parliament resolution of 21 January 2021 with recommendations to the Commission on the right to disconnect (2019/2181(INL)). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0021_EN.html#title1

- Galindo-Garre, F., & Vermunt, J. K. (2006). Avoiding boundary estimates in latent class analysis by Bayesian posterior mode estimation. Behaviormetrika, 33(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2333/bhmk.33.43

- Geurts, S. A. E., & Sonnentag, S. (2006). Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 32(6), 482–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1053

- Glavin, P., & Schieman, S. (2012). Work–family role blurring and work–family conflict: The moderating influence of job resources and job demands. Work and Occupations, 39(1), 71–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888411406295

- The Guardian. (2016, December 31). French workers win legal right to avoid checking work email out-of-hours. https://www.theguardian.com

- Häring, A., Schütz, H., Gilberg, R., Kleudgen, M., Wöhrmann, A.M., & Brenscheidt, F. (2016). Methodenbericht und Fragebogen zur BAuA-Arbeitszeitbefragung 2015 [Methodological report and questionnaire for the BAuA working time survey 2015]. Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21934/baua:bericht20160812

- Hecht, T. D., & Allen, N. J. (2009). A longitudinal examination of the work–nonwork boundary strength construct. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(7), 839–862. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job

- Hobler, D., Lott, Y., Phahl, S., & Schulze Buschoff, K. (2020). Stand der Gleichstellung von Frauen und Männern in Deutschland [Status quo in terms of gender mainstreaming in Germany]. Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut. https://www.boeckler.de/pdf/p_wsi_report_56_2020.pdf

- Jaehrling, K., & Kalina, T. (2020). “Grey zones” within dependent employment: Formal and informal forms of on-call work in Germany. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 26(4)), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258920937960

- Kasch, R., Engelhardt, M., Förch, M., Merk, H., Walcher, F., & Fröhlich, S. (2015). Ärztemangel: Was tun, bevor Generation Y ausbleibt? Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Befragung [Physician shortage: How to prevent generation Y from staying away - results of a nationwide survey]. Fachblatt für Chirurgie, 141(2), 190–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1557857

- Kossek, E. E., Ruderman, M. N., Braddy, P. W., & Hannum, K. M. (2012). Work–nonwork boundary management profiles: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(1), 112–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.04.003

- Körlings, P. (2019). Mobile Erreichbarkeit von Arbeitnehmern: Eine arbeitszeitrechtliche Bewertung [Mobile availability of employees: An evaluation in terms of working time law]. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3726/b15670

- Kreiner, G. E., Hollensbe, E. C., & Sheep, M. L. (2009). Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work–home interface via boundary work tactics. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 704–730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2009.43669916

- Lanza, S. T., Tan, X., & Bray, B. C. (2013). Latent class analysis with distal outcomes: A flexible model-based approach. Structural Equation Modeling, 20(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2013.742377

- Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/88.3.767

- Lohmann-Haislah, A. (2012). Stressreport Deutschland 2012. Psychische Anforderungen, Ressourcen und Befinden [Stress report Germany 2012]. Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin.

- Lutz, S., Schneider, F. M., & Vorderer, P. (2020). On the downside of mobile communication: An experimental study about the influence of setting-inconsistent pressure on employees’ emotional well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 105, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106216

- Masyn, K. E. (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In T. D. Little (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantiative methods in psychology. Statistical analysis, vol. 2 (pp. 551–611). Oxford University Press.

- McLachlan, G. J., & Peel, D. A. (2000). Finite mixture models. John Wiley and Sons.

- Meijman, T. E., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. D. Drenth & H. Thierry (Eds.), Handbook of work and organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 5–33). Psychology Press.

- Menz, W., Klußmann, C., & Novak, I. (2019). Arbeitsbezogene erweiterte Erreichbarkeit – Ausprägungen, Belastungen, Handlungsstrategien [Extended work availability availability – characteristics, strain, and action strategies] (2nd ed.). Universität Hamburg.

- Michel, A., Bosch, C., & Rexroth, M. (2014). Mindfulness as a cognitive-emotional segmentation strategy: An intervention promoting work–life balance. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(4), 733–754. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12072

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press.

- Nylund-Gibson, K., Grimm, R. P., & Masyn, K. E. (2019). Prediction from latent classes: A demonstration of different approaches to include distal outcomes in mixture models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 26(6), 967–985. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10.1080/10705511.2019.1590146

- O’Driscoll, M. P., Brough, P., Timms, C., & Sawang, S. (2010). Engagement with information and communication technology and psychological well-being. In P. L. Perrewé & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and well-being: Vol. 8. New developments in theoretical and conceptual approaches to job stress (pp. 269–316). Emerald. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3555(2010)0000008010

- Pangert, B., Pauls, N., & Schüpbach, H. (2016). Die Auswirkungen arbeitsbezogener erweiterter Erreichbarkeit auf Life-Domain-Balance und Gesundheit [Consequences of permanent availability on life-domain-balance and health]. (2nd ed.). Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Quirk, M., Nylund-Gibson, K., & Furlong, M. (2013). Exploring patterns of Latino/a children’s school readiness at kindergarten entry and their relations with Grade 2 achievement. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(2), 437–449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.11.002

- Ramaswamy, V., Desarbo, W. S., Reibstein, D. J., & Robinson, W. T. (1993). An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science, 12(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.12.1.103

- Schieman, S., & Young, M. (2010). The demands of creative work: Implications for stress in the work-family interface. Social Science Research, 39(2), 246–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.05.008

- Schlachter, S., McDowall, A., Cropley, M., & Inceoglu, I. (2018). Voluntary work-related technology use during non-work time: A narrative synthesis of empirical research and research Agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(4), 825–846. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12165

- Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136

- Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02294360

- Sekine, M., Chandola, T., Martikainen, P., Marmot, M., & Kagamimori, S. (2009). Socioeconomic inequalities in physical and mental functioning of British, Finnish, and Japanese civil servants: role of job demand, control, and work hours. Social Science & Medicine, 69(10), 1417–1425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.022

- Semmer, N. K., Jacobshagen, N., Meier, L. L., & Elfering, A. (2007). Occupational stress research: The stress-as-offense-to-self perspective. In J. Houdmont & S. McIntyre (Eds.), Occupational health psychology: European perspectives on research, education and practice (Vol. 2, pp. 43–60). ISMAI.

- Semmer, N. K., Jacobshagen, N., Meier, L. L., Elfering, A., Beehr, T. A., Kälin, W., & Tschan, F. (2015). Illegitimate tasks as a source of work stress. Work & Stress, 29(1), 32–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2014.1003996

- Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27

- Stapinski, L. A., Edwards, A. C., Hickman, M., Araya, R., Teesson, M., Newton, N. C., Kendler, K. S., & Heron, J. (2016). Drinking to cope: A latent class analysis of coping motives for alcohol use in a large cohort of adolescents. Prevention Science, 17(5), 584–594. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0652-5

- Strobel, H. (2013). Auswirkungen von ständiger Erreichbarkeit und Präventionsmöglichkeiten, Teil 1: Überblick über den Stand der Wissenschaft und Empfehlungen für einen guten Umgang in der Praxis [Effects of permanent availability and possibilities for prevention, part 1: An overview of the current state of scientific knowledge and recommendations for good practice]. Initiative Gesundheit und Arbeit.

- Ticona, J. (2015). Strategies of control: Workers’s use of ICTs to shape knowledge and service work. Information, Communication & Society, 18(5), 509–523. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2015.1012531

- UNESCO. (2012). International Standard Classification of Education: ISCED 2011. UNESCO Institute for Statistics Montreal. https://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced

- Valcour, M. (2007). Work-based resources as moderators of the relationship between work hours and satisfaction with work–family balance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1512–1523. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1512

- Vermunt, J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpq025

- Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2004). Latent class analysis. In M. S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, & T. F. Liao (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods (Vol. 2, pp. 549–553). SAGE.

- Voydanoff, P. (2005). Consequences of boundary-spanning demands and resources for work-to-family conflict and perceived stress. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.491

- Wöhrmann, A.M., Brauner, C., & Michel, A. (2020). BAuA-working time survey (BAuA-WTS; BAuA-Arbeitszeitbefragung). Journal of Economics and Statistics, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2020-0035

- Wurpts, I. C., & Geiser, C. (2014). Is adding more indicators to a latent class analysis beneficial or detrimental? Results of a monte-carlo study. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 920. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00920