ABSTRACT

Work intensification (WI) is a notable job stressor, which has been hypothesised to result in various negative outcomes for employees. However, earlier empirical studies regarding this stressor hypothesis have not yet been reviewed. Our narrative review focused on the outcomes for employees of WI as a perceived job stressor. Our review was based on selected qualitative and quantitative empirical studies (k = 44) published in peer-reviewed journals between the years 2000 and 2020. Altogether, the findings of these studies showed that WI was related to various negative outcomes for employees, such as impaired well-being and motivation, supporting the stressor hypothesis. Stressful WI manifested as perceived accelerated pace of work and increased effort and demands for effectivity at work. Nevertheless, other manifestations of WI (e.g. increased demands for learning) were not always associated with negative outcomes. The implications of these findings are discussed together with future directions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and aims

Since 2000, researchers have been aware of the phenomenon of work intensification (WI), which has been regarded as a job demand characteristic of modern working life (e.g. Green, Citation2004; Green & McIntosh, Citation2001; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Ulferts et al., Citation2013). Overall job demands fall into two broad categories, that is, quantitative job demands referring to the amount and pace of work (sometimes called workload) and qualitative job demands referring to cognitive/mental and emotional demands and the effort needed at work (see Van Veldhoven, Citation2014; Zapf et al., Citation2014). Qualitative job demands typically concern mental or emotional complexity of work (e.g. information processing demands or demands related to the social aspects of work). In this study, we consider WI as a specific job demand incorporating both quantitative and qualitative load.

Early definitions of WI considered only quantitative WI, which referred to intensified/increased pace of work or amount of work (see Green, Citation2001, Citation2004). More recently, WI is often perceived as a multi-faceted phenomenon, not only encompassing an intensified pace or amount of work but also increased decision-making and learning demands. Thus, besides quantitative WI as defined above, recent definitions also emphasise qualitative aspects of WI (e.g. Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Chowhan et al., Citation2019; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Zeytinoglu et al., Citation2007), referring to intensified cognitive job demands manifested, for example, as increased demands to be self-directive and to take initiatives at work (More specific definitions of qualitative WI are provided in the following section).

Job demands, including WI, have negative effects on employees’ well-being, health, and motivation, meaning that they are stressors resulting in different stress reactions (see e.g. Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007; Bowling et al., Citation2015; Daniels et al., Citation2014; Karasek & Theorell, Citation1990; Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019). In line with these findings, even the earliest studies report that WI has negative stress-related implications (Green, Citation2004; Green & McIntosh, Citation2001). More importantly, studies of WI and its effects have proliferated during the last decade, possibly because technological development in working life has accelerated, which is claimed to lead to WI (Chesley, Citation2014; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Rosa, Citation2003; Rosa & Trejo-Mathys, Citation2013; Ulferts et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, because the Covid-19 pandemic has hastened the adoption of digital technologies, it is possible that this technological acceleration will lead to even greater WI in the future. Despite increasing interest in WI, no review has so far been published on the topic, and the scientific knowledge of WI and its effects is fragmented, presented in empirical studies conducted in various disciplines.

Consequently, our aim was to review and evaluate empirical studies on WI focusing specifically on its effects on employees and organisations. Regarding these effects, we focused on employee- or organisation-related well-being (e.g. job burnout, depression and strain) and motivational outcomes (e.g. job performance, job satisfaction, and work engagement) of WI, which have typically been studied as outcomes in job stress research (e.g. Bowling et al., Citation2015; Bowling & Kirkendall, Citation2012; Karasek & Theorell, Citation1990; LePine et al., Citation2005; Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019). This narrative and integrative review is based on published quantitative and qualitative peer-reviewed studies over the last two decades from 2000 to 2020. We are particularly interested in WI as a job demand/stressor, and concerned particularly with its potential effects on employees’ well-being and motivation.

The present review makes two notable contributions. First, showing the various stress-related effects of WI would have practical value for developing stress interventions and human resource management practices. Indeed, this is the first review to focus on WI as a job stressor, thus producing useful information on which aspects of WI (quantitative or/and qualitative) are most stressful and in relation to which outcomes. Second, our review aims to contribute conceptually and theoretically to the present and future research on WI. We hope that the results obtained and their critical, integrative analysis will advance future studies on WI regarding its assessment, study designs, and correlates.

1.2. Theoretical foundations of definitions of work intensification

One common core element of both quantitative and qualitative WI is that their roots are in global societal and organisational changes towards high-speed-high-performance modes of living, that is, towards intensified efficiency, productivity, and performance in all life domains, not least in working life (see Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Rosa, Citation2003). Viewed against this background, it can be said that research on WI originated in sociology and management sciences. This research was inspired particularly by two theoretical models, namely social acceleration (SA) and high-performance work systems (HPWS) theories. SA theory (Rosa, Citation2003; Rosa & Trejo-Mathys, Citation2013) proposes that three inter-related and mutually reinforcing cycles of acceleration characterise modern societies; technological acceleration, acceleration of social change and accelerated pace of living, manifesting in this hierarchical order. We propose that technological acceleration and accelerated pace of living in particular may have the most obvious and measurable implications for working life. Technological acceleration has been perceived as the primary antecedent of WI because its various forms, such as increasing the adoption of digital technologies, robotisation, machine learning, and artificial intelligence are transforming the content of jobs, occupations and even entire industries (Autor, Citation2015; Menon et al., Citation2020). Rosa (Citation2003) and Rosa and Trejo-Mathys (Citation2013) argue that technological acceleration speeds up work processes and information transfer, thereby creating a need for employees to work more effectively and intensively. Furthermore, as work and non-work domains are closely interconnected in daily life (Kubicek & Tement, Citation2016), the acceleration in the pace of living may be reflected in WI (e.g. in terms of accelerated pace of work) and WI may, in turn, increase the pace of life, possibly maintaining a self-perpetuating cycle of acceleration in different life domains (Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Rosa, Citation2003; Rosa & Trejo-Mathys, Citation2013; Ulferts et al., Citation2013).

Moreover, SA contributes to WI by pushing organisations to speed up processes and implement more flexible organisational structures, both, again, increasing WI (see Cascio & Montealegre, Citation2016 Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010). Such organisational ramifications of SA are also apparent in HPWS theory, which is a specific combination of HR practices, work structures and processes that enhances employee skill, knowledge, commitment, involvement, and adaptability (e.g. Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Boxall & Purchell, Citation2011). More specifically, HPWS theory (Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Oppenauer & Van De Voorde, Citation2018) perceives employees’ empowerment as the main route to high performance and productive organisations. According to HPWS theory, empowerment is seen to be best achieved by fostering employees’ involvement, autonomy, and responsibility, encouraging them to apply their skills and abilities at work to the fullest extent possible. Although this emphasis on empowering employees can be beneficial for job performance and productivity, it may also entail hidden costs as it may intensify employees’ work effort and so impair their well-being through stress processes (Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Oppenauer & Van De Voorde, Citation2018).

Because both SA and HPWS theories are broad and content-rich approaches, this has also made it feasible to interpret WI as a broader phenomenon than just accelerated pace or greater amount of work, which was the dominant view in early quantitative-focused definitions of WI (Green, Citation2004; Green & McIntosh, Citation2001). In response to broad societal and organisational changes that have occurred after the concept of WI was initially introduced, contemporary scholars suggest that WI is a multi-faceted phenomenon consisting of different sub-dimensions that capture quantitative and qualitative aspects of WI. One example of such “hybrid” definitions is the recently launched intensified job demands model (IJD model, see Korunka et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno et al., Citation2019; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Paškvan et al., Citation2016), which describes the intensification of different qualitative job demands related to the overall acceleration in working life. Specifically, the IJD model (Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Paškvan et al., Citation2016) proposes that the intensification of working life occurs in five areas, where job demands are becoming qualitatively more intense (i.e. employees are expected to put greater mental effort into their work) and/or quantitatively more demanding (i.e. employees are expected to work faster or otherwise more effectively).

The first dimension of the IJD model, quantitative work intensification (henceforth a sub-dimension of WI), corresponds with the traditional view of WI as increased pace of work (Franke, Citation2015; Green, Citation2004; Green & McIntosh, Citation2001). According to Kubicek et al. (Citation2015), this facet includes a need to work faster, reduce downtime and perform different work tasks simultaneously. This dimension has its roots in the key premises presented in the models of SA (e.g. accelerated pace of living in different domains) and HPWS (e.g. organisations’ emphasis on performance and effectivity).

Other dimensions of the IJD model concern more the qualitative aspects of WI (see e.g. Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021). The second dimension is intensified job-related planning and decision-making demands, which refers to increases in decision-making authority, putting more pressure on employees to decide which tasks they need to perform (planning) and how to perform them (doing). The third dimension, intensified career-related planning and decision-making demands, means that employees are increasingly required to maintain their employability with their current employer, but simultaneously to be increasingly aware of and receptive to other (external) career opportunities (e.g. Pongratz & Voss, Citation2003). Thus, both job- and career-related planning and decision-making demands highlight that employees need to display increasing initiative and be proactive not only in their current work but also throughout their career span. These dimensions have their foundations in HPWS theory (see Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Boxall & Purchell, Citation2011). Accordingly, in achieving optimal performance, employees should be empowered and motivated by being allowed autonomy, opportunities for continuous professional and career development and skill-discretion.

Finally, the dimension of intensified learning demands means that the demands to improve work-related knowledge, skills and competencies have intensified (Kubicek et al., Citation2015). Employees are increasingly required to constantly update their job-relevant knowledge and competencies and adjust their skills in order to be able to accomplish their work (see Glaser et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno, Kubicek, et al., Citation2019; Mauno, Minkkinen et al., Citation2019; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021 Mauno & Minkkinen, Citation2020). This dimension is consistent with certain key assumptions of HPWS theory, which emphasise employees’ continuous knowledge-development and training (see Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Oppenauer & Van De Voorde, Citation2018). Likewise, processes of social acceleration, and particularly the technological acceleration and the acceleration of social change outlined in SA theory (Rosa, Citation2003; Rosa & Trejo-Mathys, Citation2013), can intensify learning demands in working life, as employees have to adapt their knowledge and skills to changing work practices and regulations.

1.3. Work intensification in the context of job stress models

The stress perspective has been widely applied as one explicit theoretical framework to explain the negative effects of WI on employees (e.g. Chesley, Citation2014; Franke, Citation2015; Korunka et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno et al., Citation2019; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Mauno & Minkkinen, Citation2020). The reasoning has generally been that as a job demand, WI entails costs for employees’ well-being and motivation because WI requires energy and effort on the part of employees, which will deplete their resources, resulting in strain and other negative stress-related outcomes (e.g. Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Meijman & Mulder, Citation1998). This proposition is again consistent with many job stress models arguing that job demands tend to result in various negative outcomes (e.g. burnout, job dissatisfaction, mental strain) (e.g. Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007; Daniels et al., Citation2014; Karasek & Theorell, Citation1990; Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019).

Consistent with the stress perspective and the definitions of WI proposed above, we approach WI as a multi-faceted job demand/stressor encompassing intensifying quantitative and qualitative load that can be expected to be associated with negative outcomes, and particularly with impaired work-related and overall well-being. Noteworthy is that earlier reviews of the effects of other job demands (e.g. workload, see Bowling et al., Citation2015; Bowling & Kirkendall, Citation2012) have indicated that the relationships between job demands and work-related outcomes (e.g. job performance, organisational commitment) were not always robust or sometimes even non-significant. Thus, not all job demands may produce consistent effects for employees, but the effects are conditional upon the type of demand and the type of outcome(s). Here, we suggest that this inconsistency may apply equally to WI as a job demand, given that WI may have divergent (quantitative and qualitative) manifestations, as presented above. For these reasons, we propose no specific hypotheses on the direction of the relationships between WI and the outcomes studied but rather seek to analyse whether and how these associations have emerged in earlier studies.

Considering different conceptualisations of WI, it is also plausible that there will be heterogeneity in the associations between WI and its outcomes. Searching for such heterogeneity in published studies may be accomplished by means of a narrative review approach allowing us also to analyse qualitative studies (Popay et al., Citation2006). The idea that job demands may result in negative or positive outcomes is theoretically explicable via a challenge-hindrance model of job stress (Crawford et al., Citation2010; LePine et al., Citation2005; Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019), which argues that job demands can generally be divided into challenge and hindrance stressors. Challenges boost personal growth and development, implying positive motivational consequences, whereas hindrances include organisational obstacles hampering the accomplishment of work, resulting in negative well-being outcomes. However, the proposition on the distinct effects of challenge-hindrance stressors has not received strong empirical support (for a meta-analysis, see Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019). We therefore deemed it premature to pose hypotheses on the distinct outcomes of WI, given that different conceptualisations of WI (viewed either as a challenge or a hindrance stressor) are predominant in the research literature. Not posing pre-defined hypotheses also fits the narrative review approach, making it possible to find meaningful interpretations of data even if there is disparity in theory and methodology (Borenstein et al., Citation2009; Popay et al., Citation2006).

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search and selection of studies

Our review is predominantly a narrative and integrative conceptual synthesis including qualitative and quantitative studies on WI. Narrative review adopts a narrative synthesis approach aiming to create a coherent narrative that summarises and describes the evidence found regarding some phenomenon (Popay et al., Citation2006). Specifically, narrative synthesis enables an integration of disparate studies conducted using different disciplinary approaches and different methodologies. During the review process, we soon recognised that research on WI was characterised by marked conceptual and methodological disparity, supporting the applicability of a narrative approach. Narrative review was also appropriate in analysing differences in the content and facets of WI, taking into account that no such conceptual synthesis has been published. On these grounds, we rejected a meta-analytic approach, which might have yielded biased results in case of a strong conceptual or methodological disparity in the phenomena analysed, for example, major differences in operationalising the concepts, study designs or variations in conceptual hypotheses (see Borenstein et al., Citation2009). Reviewing the literature showed that such methodological disparity concerned not only the concept of WI but also the outcomes studied. Methodological disparity together with a small number of quantitative primary studies, might result in unreliable conclusions in meta-analysis and in such situations, qualitative, in-depth reviews may yield more meaningful interpretations and conclusions (Borenstein et al., Citation2009).

Although our review is mostly narrative, we benefitted from a systematic approach in searching and selecting the studies. We began to search the primary studies from the Web of Science database using the phrase “work intensification.” WI is a concept that has long been acknowledged in working life research (Green, Citation2001; Green & McIntosh, Citation2001) and thus we limited our search to the phrase “work intensification.” Moreover, we did not want to include studies focusing on other job demands/stressors, for example, workload, of which two reviews have been published (Bowling et al., Citation2015; Bowling & Kirkendall, Citation2012). However, these two reviews did not reveal anything about WI because they focused on workload as a composite demand without distinguishing different types of job demands (e.g. WI).

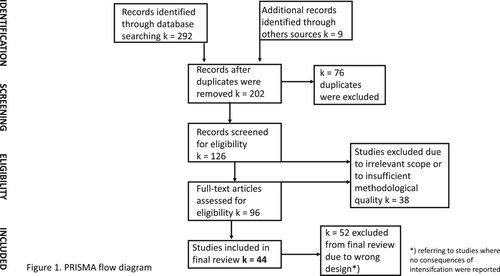

A PRISMA diagram describing the process of selecting the primary studies is presented in . We limited the search to scientific articles (to ensure a minimal quality standard) between the years 2000 and 2020 because the first descriptions of WI appeared at the beginning of the new millennium. This search resulted in a total of 85 records in the Web of Science database. We also conducted an additional literature search in the Google Scholar database using the same search and selection criteria, which resulted in 207 records from which we again selected only relevant empirical studies based on the abstracts (based on both databases, in total k = 292, see ). After carefully co-reviewing 292 records (by five senior researchers with expertise in WI and job stress research), we selected 10 qualitative and 34 quantitative studies for this review (k = 44). In screening and selecting the studies, we applied the following two inclusion criteria. First, the study reported results on the employee- or organisation-related outcomes of WI. That is, in quantitative studies, statistical relationships between WI and outcome(s) and in qualitative studies some interpretations of the implications of WI on employees/organisations need to be provided. Second, the study reported adequate descriptions of the scientific methodology, most importantly, an adequate description of the concept and assessment of WI. Exclusion criteria included scientific articles not written in English, theoretical papers, review articles, opinion papers, commentaries, notes, dissertations, conference papers, posters, books, news, and studies with non-working populations.

3. Results

3.1. Results of qualitative studies

The results of the 10 qualitative studies included in this review are presented in . Here, we provide only a brief summary of the key findings. First, we focus on the conceptualisation of WI and then on its implications for employees. It was relatively common for the qualitative studies not to start with a focus on WI, but for the topic to emerge in the data. When employees were asked about other topics, they spontaneously mentioned WI. This suggests that, from an employee's perspective, WI is a relevant and identifiable phenomenon. However, somewhat different conceptualisations of WI were found in qualitative studies, for example, high performance/productivity demands, experiences of intensity at work, long working hours, accelerated pace of work, organisational pressures and extensive mental/emotional/physical input at work. Nevertheless, many of these definitions correspond to the theoretical foundations of WI established in the SA and HPWS models, for example. Thus, the conceptualisations used in these qualitative studies supported the theoretical models underlying WI.

Table 1. Qualitative studies on the implications of work intensification (WI).

With regard to the outcomes of WI (see ), some qualitative studies reported that WI had impaired employees’ capabilities to do their work in an ethical/sustainable manner by creating moral distress and guilt (Beck, Citation2017; Granter et al., Citation2019; Ogbonna & Harris, Citation2004), by imposing major flexibility demands on employees (Bergman & Gillberg, Citation2015), by compromising their professional standards (e.g. regarding quality of care in nursing; Harvey et al., Citation2020; Henderson et al., Citation2016; Willis et al., Citation2015), and by causing interaction problems in the workplace (Ogbonna & Harris, Citation2004). More conventional stress-related consequences of WI were also reported in some studies. These included health and recovery problems, job dissatisfaction, various negative emotions (Bergman & Gillberg, Citation2015; Ogbonna & Harris, Citation2004; Wankhade et al., Citation2020), exhaustion/mental fatigue (Granter et al., Citation2019) and anxiety (Harvey et al., Citation2020). Two studies focused on inability to work. Seing et al. (Citation2015) reported that WI was related to (less) sustainable return to work of sick-listed employees, who also showed less attachment to work and resistance to job changes, both related to WI. Wankhade et al. (Citation2020) found increased sickness absenteeism in relation to WI. Furthermore, only one study found that WI (among white-collar employees with flexible work arrangements) was associated with positive implications, namely higher job satisfaction and organisational commitment (Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010). To summarise, the qualitative studies reported that WI was predominantly associated with negative implications for employees.

3.2. Results of the quantitative studies: One-dimensional approach

One-dimensional conceptualisation and measurement of WI was used in 26 studies (see ). As in the qualitative studies, the definitions and measurements of WI varied significantly across studies, indicating strong conceptual and methodological disparity. The definitions and measurements of WI included, for example high level of involvement/effort/input at work, the rising level of work demands, long/excessive working hours, fast pace of work, “doing more,” “being busy,” increased multitasking demands and WI related to digital technologies. The content of these one-dimensional indicators shows that they originate in the SA and HWPS models described earlier and principally characterise the quantitative aspects of WI. Typically, these studies examined employee outcomes related to mental health, including various mental health indicators, such as, stress symptoms, anxiety, overall stress, work ability, depression, and psychosomatic symptoms which were investigated in 12 studies. Job satisfaction (10 studies) and work-family (im)balance (6 studies) were also frequently studied outcomes. Other typical outcomes included job burnout (4 studies), work-related performance, pay level and/or organisational commitment (4 studies), and work engagement (2 studies).

Table 2. One-dimensional approach to work intensification (WI): quantitative studies.

Overall, the results show that WI, as one-dimensional construct, is related to several negative outcomes. Thirteen studies (Borle et al., Citation2021; Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Chesley, Citation2014; Chillakuri & Vanka, Citation2022; Chowhan et al., Citation2019; Engelbrecht et al., Citation2020; Fiksenbaum et al., Citation2010; Green, Citation2001; Krause et al., Citation2005; Ogbonnaya et al., Citation2017; Ogbonnaya & Valizade, Citation2015; Xia et al., Citation2020; Zeytinoglu et al., Citation2007) reported an association between WI and some indicator of impaired mental or physical (self-rated) health. Nine studies reported a negative association between WI and job satisfaction (Brown, Citation2012; Chang et al., Citation2018; Le Fevre et al., Citation2015; Ogbonnaya et al., Citation2017; Ogbonnaya & Valizade, Citation2015; Paškvan et al., Citation2016; Sayin et al., Citation2021; Xia et al., Citation2020; Zeytinoglu et al., Citation2007). Six studies showed that WI related to work-family imbalance (e.g. work-family conflict; Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Brown, Citation2012; Fiksenbaum et al., Citation2010; Kubicek & Tement, Citation2016; Le Fevre et al., Citation2015; Yu, Citation2014), and four reported a link between WI and job burnout (Engelbrecht et al., Citation2020; Fiksenbaum et al., Citation2010; Huo et al., Citation2022; Paškvan et al., Citation2016). A negative relationship between WI and work engagement was found in four studies (Engelbrecht et al., Citation2020; Fiksenbaum et al., Citation2010; Huo et al., Citation2022; Paškvan et al., Citation2016) as was the association between WI and lower work-related performance/commitment/trust in management (Bunner et al., Citation2018; Neirotti, Citation2020; Ogbonnaya et al., Citation2017; Sayin et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, a majority of these quantitative studies (k = 19/26, 73%) explored mediator and/or moderator relationships in addition to direct associations between WI and employee outcomes. These results were often complex and based on different theoretical models and we make no attempt to summarise them here. More details on these studies can be found in . Overall, several mediators were explored: work-family balance (Brown, Citation2012), safety behaviours (Bunner et al., Citation2018), negative affect (Chang et al., Citation2018), WI (Chesley, Citation2014; Xia et al., Citation2020), HPWS (Chillakuri & Vanka, Citation2022), stress symptoms (Chowhan et al., Citation2019; Sayin et al., Citation2021; Zeytinoglu et al., Citation2007), workaholism (Engelbrecht et al., Citation2020), exhaustion (Huo et al., Citation2022), job satisfaction (Sayin et al., Citation2021), job crafting (Li et al., Citation2020), participative decision-making (Ogbonnaya & Valizade, Citation2015), and stress appraisal (Paškvan et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, WI also functioned as a mediator in certain studies (e.g. Ogbonnaya et al., Citation2017; Ogbonnaya et al., Citation2017).

Moderator relationships were studied less often but moderators included gender (Le Fevre et al., Citation2015; Yu, Citation2014), workplace well-being (Chillakuri & Vanka, Citation2022); managerial support (Huo et al., Citation2022), work-home segmentation (Kubicek & Tement, Citation2016), work-home boundary management (Kubicek & Tement, Citation2016), perceived organisational support (Lawrence et al., Citation2019), work addiction (Li et al., Citation2020), participative climate (Paškvan et al., Citation2016) and a specific lean management strategy (Neirotti, Citation2020).

To summarise, all the quantitative studies (k = 26) that used a one-dimensional conceptualisation and operationalisation of WI reported that WI is a stressor associated with various negative consequences for employees. Furthermore, many different factors were tested either as mediators or moderators between WI and employee outcomes. Although all individual relationships (e.g. concerning multiple outcomes or moderator effects) were not consistently confirmed, the majority of these findings still provide support for one-dimensional quantitative WI as a job stressor with adverse effects for employees.

3.3. Results of the quantitative studies: Multi-dimensional approach

Multi-dimensional conceptualisation, measurement and dimension-based analyses of WI were used in eight studies, which are summarised in . Most of these studies applied the IJD model (see Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno et al., Citation2020; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021) in the multi-dimensional assessment of WI, aiming to capture the essence of qualitative WI. Employee outcomes used in these studies included job burnout (Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno et al., Citation2019), job satisfaction (Korunka et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015, p. 2 studies; Macky & Boxall, Citation2008), health/stress indicators (Bamberger et al., Citation2015; Burke et al., Citation2010; Franke, Citation2015; Macky & Boxall, Citation2008), work engagement (Mauno et al., Citation2019), job performance (Mauno et al., Citation2020), and work-life imbalance (Macky & Boxall, Citation2008).

Table 3. Multi-dimensional approach to work intensification (WI): Quantitative studies.

The results show that three out of four studies relying on the IJD model found a positive relationship between the sub-dimension of WI (including accelerated working pace, less idle time and increasing multi-tasking demands; describing quantitative WI) and job burnout, for example, exhaustion and cynicism (Korunka et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno et al., Citation2019). Two studies (Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno et al., Citation2019) showed a positive relationship between the sub-dimensions of intensified planning and decision-making demands (concerning job and career) and job burnout. These two studies also reported that intensified learning demands (concerning skills and knowledge) were positively related to job burnout.

Two studies (Korunka et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015) revealed that the sub-dimensions of quantitative WI and intensified career-related planning and decision-making demands (the latter is one indicator of qualitative WI) were associated with job dissatisfaction. However, a longitudinal study by Korunka et al. (Citation2015) found that increases in intensified learning demands were related to subsequent increases in job satisfaction (as well as decreases in job burnout). Furthermore, Mauno et al. (Citation2019) found that intensified learning demands related positively to work engagement, as did intensified job-related planning and decision-making demands. Job performance (self-rated) was studied in one study (Mauno et al., Citation2020) which indicated that the sub-dimension of quantitative WI was negatively associated with task performance, whereas intensified learning demands and job-related planning and decision-making demands (indicators of qualitative WI) were positively associated with organisational citizenship behaviour.

Finally, four studies (Bamberger et al., Citation2015; Burke et al., Citation2010; Franke, Citation2015; Macky & Boxall, Citation2008) measured multi-dimensionality of intensification using other multi-dimensional scales than the IJD model. Macky and Boxall (Citation2008) found that weekly working hours, perceived overload, and time demands as indicators of intensification were related to more stress, fatigue, work-life imbalance, and job dissatisfaction. Bamberger et al. (Citation2015) found that employees’ distress was associated with three dimensions of intensification: increases in technical/professional demands, autonomy paired with high responsibility demands and demands for labour productivity. Franke (Citation2015) found that both WI and work intensity were associated with psychosomatic and musculoskeletal complaints (signalling stress) and most symptoms were reported when both of these demands were high (interaction effect). Burke et al. (Citation2010) showed that emotional and job-related intensification was associated with job-related stress. None of the multi-dimensional studies reviewed included mediators in their designs. Moderators between multi-dimensional intensification and employee outcomes were investigated in only two studies: age was studied as a moderator in one study (Mauno et al., Citation2019) and self-regulation strategies in one study (Mauno et al., Citation2020).

To summarise, these studies show that when WI was assessed multi-dimensionally, for example, via the IJD model, the findings were less consistent compared to the findings of studies which applied one-dimensional assessment of WI. While some sub-dimensions of WI were associated with negative effects, some other sub-dimensions (e.g. intensified learning demands) actually showed positive or both positive and negative effects. Hence, the stressfulness of WI was not consistently supported in multi-dimensional studies, in which qualitative aspects of WI (e.g. increased cognitive complexity of work) were also typically evaluated. However, the multi-dimensional studies typically also included a traditional indicator of quantitative WI (e.g. doing more, working faster/harder) and this particular sub-dimension was found to be a harmful stressor in each study. This result is well in line with the key findings of the one-dimensional and qualitative studies reported above. Altogether, these findings provide relatively compelling evidence that at least one sub-dimension of WI, namely, experiencing increased working pace, constant efficiency requirements or just “having too much to do,” that is, experiencing quantitative WI, is stressful and relates to various negative consequences for employees.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical and methodological conclusions

In this narrative review, we explored whether WI, in its various forms, is associated with employee- and organisation-related outcomes. Overall, job stress models inspired our review and thus the results will be discussed mostly from this perspective. The results showed overall that one kind of quantitative WI, employees’ appraisals of increased pace of work, effectivity, and multi-tasking demands, may constitute a hindrance demand (see Crawford et al., Citation2010; LePine et al., Citation2005; Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019) with adverse effects on well-being. We argue that this sub-type of WI may include aspects of quantitative job demands, which have been shown in various studies to be harmful job stressors resulting in impaired employee well-being (for reviews, see Bowling et al., Citation2015; Bowling & Kirkendall, Citation2012; Van Veldhoven, Citation2014). In this sense, our finding is in line with job stress models and the related empirical findings (e.g. Daniels et al., Citation2014; Karasek & Theorell, Citation1990; LePine et al., Citation2005). Furthermore, viewed from the HPWS framework (Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Boxall & Purchell, Citation2011; Macky & Boxall, Citation2008), constant performance and productivity demands posed by the organisation might be appraised as stressful WI by employees, which again may relate to negative well-being outcomes. Also, the acceleration of social change and in technology introduced in the SA model (Rosa, Citation2003; Rosa & Trejo-Mathys, Citation2013) may cause further acceleration in working life, manifesting as employees’ experiences of WI. This, in turn, may result in harmful stress-related ramifications (e.g. Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021).

Nevertheless, our review also indicated that other, more recently identified qualitative aspects of WI, for example, intensified work-related learning demands (Korunka et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno et al., Citation2019; Mauno et al., Citation2020), did not have consistently negative effects across studies. This, in turn, would suggest that certain qualitative aspects of WI may be perceived as a challenge rather than as a hindrance demand, consequently resulting in positive rather than negative outcomes (Crawford et al., Citation2010; LePine et al., Citation2005; Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019). However, it should be noted that there is so far no firm theoretical argument regarding how and why different aspects of WI should be categorised as challenge or hindrance demands. Moreover, the empirical evidence on the hypothesised positive effects of challenge demands is so far relatively weak (for a meta-analysis, see Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019). Thus, until more empirical evidence is gathered, we must be cautious when considering certain qualitative aspects of WI as positively perceived challenge demands associated with positive rather than negative outcomes.

This review also revealed that research on WI has mostly been conducted via different theoretical models, for example, the SA model, the HPWS model, and stress model(s), and these models have typically been applied separately. As these previous theories have typically been developed within one scientific field (sociology/management/psychology), they have not fully considered that in order to understand the phenomenon of intensification and its variable outcomes, a multi-disciplinary approach is indispensable (see Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021). Thus, more integrated theoretical model(s) should be developed. Consequently, multi-disciplinary models integrating present (and future) social and economic factors into well-being/job stress theories, from the standpoint of WI, would be fruitful. Upcoming megatrends, for example, accelerated digitalisation, increasing remote work, and unpredictability in the labour market and careers, should be considered in these models because such megatrends may intensify work differently than what has been suggested in previous theories and studies. Indeed, the quality of work (e.g. cognitive and emotional demands) may intensify more than the quantity of work (e.g. working pace), as mentally and emotionally complicated tasks continue to require human effort. Such major changes require multi-disciplinary approaches which might also encourage researchers to develop and test new relevant hypotheses concerning WI and its implications.

This review also revealed that both conceptual and methodological development are needed concerning the concept of WI. A synopsis of the definitions of WI (detailed conceptual analysis is available from the authors upon request) showed that there is no uniform definition of WI but rather an umbrella of partly overlapping definitions and assessments. However, quantitative elements of WI (e.g. intensified working pace, increased workload) was included in most definitions and measurements of WI, although their specific operationalisation varied across studies. The conceptualisations and assessments of qualitative WI varied more across studies. Admittedly, it may not even be possible to achieve any uniform definition of WI as the phenomenon itself has so many quantitative and qualitative facets today and may have even more in the future. However, it is good to recall that conceptualisations and subsequent measurements always determine what can be found in empirical studies. For example, the multi-dimensional IJD model (Korunka et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno et al., Citation2019; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021) developed to evaluate the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the intensification of complicated and information-filled working life is represents an attempt to capture the different elements of cognitively intensified working life. However, there are some drawbacks in the IJD model; it focuses on employees’ experiences of intensification and acceleration by comparing present to past concerning employees’ work experiences. This methodological approach is not appropriate for the assessment of WI among newcomers who have just entered the labour market. Moreover, job changes over the career span may affect WI. When employees change jobs, their job content may also change and assessing intensification by comparing one's current and previous work experiences may in such cases produce misleading information.

Furthermore, the concept of WI itself is elusive as it is implicitly dynamic (rooted in a multi-faceted acceleration), and this viewpoint includes some methodological challenges. Our review reveals that the dynamic nature of WI has not been fully considered in earlier studies. Sometimes WI was measured as a sub-type of (quantitative) workload, the assessment of which does not take into account its unique, dynamic nature as a job stressor referring to increases or acceleration of certain job demands (Korunka et al., Citation2015; Kubicek et al., Citation2015; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021). However, this is not to suggest that WI would be an irrelevant concept or purely overlapping with quantitative workload. Rather, we propose that researchers should always carefully consider how to measure, evaluate, and interpret WI. At least, the characteristics of the sample (e.g. respondents’ career histories) and the time-frame (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) of the study design should be taken into account.

The dynamic nature of WI also means that the concept may have different temporal manifestations. For example, WI may occur as a part of long-term societal processes (consistent with SA theory) but it may equally manifest in short-lived experiences among employees concerning working pace or the mental effort needed at work on a daily basis. Temporally different dynamics of WI would naturally require different research instruments and methodologies depending on the research targets. A related aspect is that longitudinal studies on the effects of WI were almost non-existent in our review. This shortcoming should be addressed in future by also paying attention to the different temporal dynamics of WI in data collection and analyses. Furthermore, other than self-report indicators in studying the consequences of WI, such as organisations’ sickness absence registers or performance measures, should be included as outcome indicators in future studies. Finally, qualitative studies on the implications of WI were rare in our review (k = 10/44). Consequently, qualitative and mixed-methods studies focusing on employees’ subjective experiences of the implications of WI might produce valuable new information that could also be utilised by quantitative researchers.

4.2. Limitations and final remarks

Three notable limitations need to be addressed in interpreting the conclusions of this review. First, our review is not exhaustive, meaning that some relevant studies may have been excluded. Second, none of the studies reviewed tested the health selection hypothesis, that is, whether employees’ well-being/health determines their perceptions of intensification rather than intensification as a cause of ill-being, as suggested by the job stressor hypothesis. Thus, the question of causality remains unresolved. Third, this review was narrative, and therefore, in contrast to meta-analytical reviews, its methodology does not produce exact statistical parameter values. However, the studies reviewed were characterised by theoretical, conceptual and methodological disparity, which led us to choose the narrative review approach (see Popay et al., Citation2006).

Regarding practical implications, we propose that employers should pay more attention to the harmful effects of WI and realise that organisations’ constant high-performance and effectivity expectations, representing the core manifestation of quantitative WI, may constitute a risk to employees’ health and well-being. Therefore, organisations and managers should be sensitive to employees’ experiences of WI and willing to screen when, how, and which aspects of work have intensified. It is also noteworthy that WI may manifest differently than suggested by its traditional definitions, depending, for example, on the nature of work and the era people are living in. At a societal level, WI might be reduced by legislation. One such recent attempt is the new directive proposal of the European Union that would restrict employers’ rights to contact personnel during their free time, aiming to alleviate WI and work extension and their negative implications for employees. Certainly, various actions are needed at different levels (societal, organisational, and individual) towards a more sustainable working life. This would require striking a balance between human potential and capabilities (the individual perspective) and productivity demands (the organisational and economic perspective). Living in a high-speed-high-performance society may challenge human potential in working life (see Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Mauno & Kinnunen, Citation2021; Rosa, Citation2003). Finding a balance between human potential and productivity demands might begin by acknowledging employees’ experiences of various types of WI. This review showed that WI has indeed different manifestations and that some of these are more harmful than others for employees’ well-being and motivation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Studies included in the review marked *

- Autor, D. H. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.3.3

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- *Bamberger, S. G., Larsen, A., Vinding, A. L., Nielsen, P., Fonager, K., Nielsen, R. N., Ryom, P., & Omland, Ø. (2015). Assessment of work intensification by managers and psychological distressed and non-distressed employees: A multilevel comparison. Industrial Health, 53(4), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2014-0176

- *Beck, J. L. (2017). The weight of a heavy hour: Understanding teacher experiences of work intensification. McGill Journal of Education, 52(3), 563–807. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050906ar

- *Bergman, A., & Gillberg, G. (2015). The cabin crew blues. Middle-aged cabin attendants and their working conditions. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 5(4), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.19154/njwls.v5i4.4842

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). When does it make sense to perform a meta-analysis? In M. Borenstein, L. V. Hedges, J. P. Higgins, & H. R. Rothstein (Eds.), Introduction to meta-analysis (pp. 357–364). John Wiley & Sons. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470743386

- *Borle, P., Boerner-Zobel, F., Voelter-Mahlknecht, S., Hasselhorn, H. M., & Ebener, M. (2021). The social and health implications of digital work intensification. Associations between exposure to information and communication technologies, health and work ability in different socio-economic strata. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 94(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-020-01588-5

- Bowling, N. A., Alarcon, G. M., Bragg, C. B., & Hartman, M. J. (2015). A meta-analytic examination of the potential correlates and consequences of workload. Work & Stress, 29(2), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1033037

- Bowling, N. A., & Kirkendall, C. (2012). Workload: A review of potential causes, consequences and interventions. In J. Houdmont, S. Leka, & R. Sinclair (Eds.), Contemporary occupational health psychology: Global Perspectives on research and practice (Vol. 2, pp. 221–238). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119942849.ch13.

- *Boxall, P., & Macky, K. (2014). High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being. Work, Employment, and Society, 28(6), 963–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017013512714

- Boxall, P., & Purchell, J. (2011). Strategy and human resource management (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- *Brown, M. (2012). Responses to work intensification: Does generation matter? International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(17), 3578–3595. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.654348

- *Bunner, J., Prem, R., & Korunka, C. (2018). How work intensification relates to organisation-level safety performance: The mediating roles of safety climate, safety motivation, and safety knowledge. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02575

- *Burke, R. J., Singh, P., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2010). Work intensity: Potential antecedents and consequences. Personnel Review, 39(3), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481011030539

- Cascio, W. F., & Montealegre, R. (2016). How technology is changing work and organizations? Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 349–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062352

- *Chang, P.-C., Wu, T., & Liu, C.-L. (2018). Do high-performance work systems really satisfy employees? Evidence from China. Sustainability, 10(10), 3360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103360

- *Chesley, N. (2014). Information and communication technology use, work intensification and employee strain and stress. Work, Employment and Society, 28(4), 589–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017013500112

- *Chillakuri, B., & Vanka, S. (2022). Understanding the effects of perceived organizational support and high-performance work systems on health harm through sustainable HRM lens: A moderated mediated examination. Employee Relations, 44(3), 629–649. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-01-2019-0046

- *Chowhan, J., Denton, M., Brookman, C., Davis, S., Sayin, F., & Zeytinoglu, I. (2019). Work intensification and health outcomes of health sector workers. Personnel Review, 48(2), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2017-0287

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364

- Daniels, K., Le Blanc, P., & Davis, M. (2014). The models that made job design. In M. Peeters, J. de Jonge, & T. W. Taris (Eds.), An introduction to contemporary work psychology (pp. 63–89). Wiley Blackwell.

- *Engelbrecht, G. J., de Beer, L. T., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2020). The relationships between work intensity, workaholism, burnout, and self-reported musculoskeletal complaints. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries, 30(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20821

- *Fiksenbaum, L., Jeng, W., Koyuncy, M., & Burke, R. J. (2010). Work hours, work intensity, satisfactions and psychological well-being among hotel managers in China. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 17(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527601011016925

- *Franke, F. (2015). Is work intensification extra stress? Journal of Personnel Psychology, 14(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000120

- Glaser, J., Seubert, C., Hornung, S., & Herbig, B. (2015). The impact of learning demands, work-related resources, and job stressors on creative performance and health. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 14(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000127

- *Granter, E., Wankhade, P., McCann, L., Hassard, J., & Hyde, P. (2019). Multiple dimensions of work intensity: Ambulance work as edgework. Work, Employment & Society, 33(2), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018759207

- *Green, F. (2001). It’s been a hard day’s night: The concentration and intensification of work in late twentieth-century Britain. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 39(1), 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8543.00189

- Green, F. (2004). Why has work effort become more intense? Industrial Relations, 43(4), 709–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0019-8676.2004.00359.x

- Green, F., & McIntosh, S. (2001). The intensification of work in Europe. Labour Economics, 8(2), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(01)00027-6

- *Harvey, C., Thompson, S., Otis, E., & Willis, E. (2020). Nurses’ views on workload, care rationing and work environments. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(4), 912–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13019

- *Henderson, J., Willis, E., Blackman, I., Toffoli, L., & Verrall, C. (2016). Causes of missed nursing care: Qualitative responses to a survey of Australian nurses. Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work, 26(4), 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2016.1257755

- *Huo, M.-L., Boxall, P., & Cheung, G. W. (2022). Lean production, work intensification and employee wellbeing: Can line-manager support make a difference? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 43(1), 198–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X19890678

- Karasek, R., & Theorell, T. (1990). Health work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books.

- *Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63(1), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709349199

- *Korunka, C., Kubicek, B., Paškvan, M., & Ulferts, H. (2015). Changes in work intensification and intensified learning: Challenge or hindrance demands? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(7), 786–800. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-02-2013-0065

- *Krause, N., Scherzer, T., & Rugulies, R. (2005). Physical workload, work intensification, and prevalence of pain in low wage workers: Results from a participatory research project with hotel room cleaners in Las Vegas. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 48(5), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20221

- *Kubicek, B., Paškvan, M., & Korunka, C. (2015). Development and validation of an instrument for assessing job demands arising from accelerated change: The intensification of Job Demands Scale (IDS). European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 24(6), 898–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.979160

- *Kubicek, B., & Tement, S. (2016). Work intensification and the work-home interface. The moderating effect of individual work-home segmentation strategies and organisational segmentation supplies. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 15(2), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000158

- *Lawrence, D. F., Loi, N. M., & Gudex, B. W. (2019). Understanding the relationship between work intensification and burnout in secondary teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 25(2), 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1544551

- *Le Fevre, M., Boxall, P., & Macky, K. (2015). Which workers are more vulnerable to work intensification? An analysis of two national surveys. International Journal of Manpower, 36(6), 966–983. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-01-2014-0035

- LePine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & LePine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor-hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 764–775. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2005.18803921

- *Li, Y., Xie, W., & Huo, L. (2020). How can work addiction buffer the influence of work intensification on workplace well-being? The mediating role of job crafting. International Journal of Environmental Research on Public Health, 17(13), 4658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134658

- *Macky, K., & Boxall, P. (2008). High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being: A study of New Zealand worker experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 46(1), 38–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038411107086542

- Mauno, S., & Kinnunen, U. (2021). The importance of recovery from work in intensified working life. In C. Korunka (Ed.), Flexible working practices and approaches: Psychological and social implications of a multifaceted phenomenon (pp. 59–79). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74128-0_4

- *Mauno, S., Kubicek, B., Feldt, T., & Minkkinen, J. (2020). Intensified job demands and job performance: Does SOC strategy use make a difference? Industrial Health, 58(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2019-0067

- Mauno, S., Kubicek, B., Minkkinen, J., & Korunka, C. (2019). Antecedents of intensified job demands: Evidence from Austria. Employee Relations, 41(4), 694–707. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2018-0094

- Mauno, S., & Minkkinen, J. (2020). Profiling a spectrum of mental job demands and their linkages to employee outcomes. Journal of Person-Oriented Research, 6(1), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.17505/jpor.2020.22046

- *Mauno, S., Minkkinen, J., Tsupari, H., Huhtala, M., & Feldt, T. (2019). Do older employees suffer more from work intensification and other intensified job demands? Evidence from upper white-collar workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.16993/sjwop.60

- Mazzola, J. J., & Disselhorst, R. (2019). Should we be “challenging” employees? A critical review and meta-analysis of the challenge-hindrance model of stress. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(8), 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2412

- Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. D. Drenth, & H. Thierry (Eds.), Handbook of work and organisational psychology (Vol. 2, Work psychology, pp. 5–33). Psychology Press.

- Menon, S., Salvatori, A., & Zwysen, W. (2020). The effect of computer use on work discretion and work intensity: Evidence from Europe. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 58(4), 1004–1038. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12504

- *Neirotti, P. (2020). Work intensification and employee involvement in lean production: New light on a classic dilemma. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(15), 1958–1983. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1424016

- *Ogbonna, E., & Harris, L. C. (2004). Work intensification and emotional labour among UK university lecturers: An exploratory study. Organisation Studies, 25(7), 1185–1203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604046315

- *Ogbonnaya, C., Daniels, K., Connolly, S., & van Veldhoven, M. (2017). Integrated and isolated impact of high-performance work practices on employee health and well-being: A comparative study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(1), 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000027

- *Ogbonnaya, C., Daniels, K., & Nielsen, K. (2017). Does contingent pay encourage positive employee attitudes and intensify work? Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 94–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12130

- *Ogbonnaya, C. N., & Valizade, D. (2015). Participatory workplace activities, employee-level outcomes and the mediating role of work intensification. Management Research Review, 38(5), 540–558. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-01-2014-0007

- Oppenauer, V., & Van De Voorde, K. (2018). Exploring the relationships between high involvement work system practices, work demands, and emotional exhaustion: A multilevel study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(2), 311–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1146321

- *Paškvan, M., Kubicek, B., Prem, R., & Korunka, C. (2016). Cognitive appraisal of work intensification. International Journal of Stress Management, 23(2), 124–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039689

- Pongratz, H. J., & Voss, G. G. (2003). From employee to ‘entreployee’: Towards a ‘self-entrepreneurial’ work force? Concepts and Transformation, 8(3), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1075/cat.8.3.04pon

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., & Britten, N. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Version 1. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1018.4643

- Rosa, H. (2003). Social acceleration: Ethical and political consequences of a desynchronized high-speed society. Constellations (oxford, England), 10(1), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.00309/

- Rosa, H., & Trejo-Mathys, J. (2013). What is social acceleration? In H. Rosa (Ed.), Social acceleration: A new theory of modernity (pp. 63–94). Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/rosa14834

- *Sayin, F. K., Denton, M., Brookman, C., Davies, S., Chowhan, J., & Zeytinoglu, I. U. (2021). The role of work intensification in intention to stay: A study of personal support workers in home and community care in Ontario, Canada. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 42(4), 917–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X18818325

- *Seing, I., MacEachen, E., Ståhl, C., & Ekberg, K. (2015). Early-return-to-work in the context of an intensification of working life and changing employment relationships. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 25(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9526-5

- Ulferts, H., Korunka, C., & Kubicek, B. (2013). Acceleration in working life: An empirical test of a sociological framework. Time & Society, 22(2), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X12471006

- Van Veldhoven, M. (2014). Quantitative job demands. In M. Peeters, J. De Jonge, & T. Taris (Eds.), An introduction to contemporary work psychology (pp. 117–143). Wiley Blackwell.

- *Wankhade, P., Stokes, P., Tarba, S., & Rodgers, P. (2020). Work intensification and ambidexterity - the notions of extreme and ‘everyday’ experiences in emergency contexts: Surfacing dynamics in the ambulance service. Public Management Review, 22(1), 48–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1642377

- *Willis, E., Toffoli, L., Henderson, J., Couzner, L., Hamilton, P., Verrall, C., & Blackman, I. (2015). Rounding, work intensification and new public management. Nursing Inquiry, 23(2), 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12116

- *Xia, J., Zhang, M. M., Zhu, J. C., Fan, D., & Samaratunge, R. (2020). HRM reforms and job-related well-being of academics. Personnel Review, 49(2), 597–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2018-0188

- *Yu, S. (2014). Work–life balance – work intensification and job insecurity as job stressors. Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work, 24(3), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2014.961683

- Zapf, D., Semmer, N., & Johnson, S. (2014). Qualitative demands at work. In M. Peeters, J. De Jonge, & T. Taris (Eds.), An introduction to contemporary work psychology (pp. 144–169). Wiley Blackwell.

- *Zeytinoglu, I. U., Denton, M., Davies, S., Baumann, A., Blythe, J., & Boos, L. (2007). Associations between work intensification, stress and job satisfaction: The case of nurses in Ontario. Industrial Relations, 62(2), 201–225. https://doi.org/10.7202/016086ar