ABSTRACT

This study disentangles positive and negative reactions to home-to-work transitions (i.e. transitions from the home role to the work role during non-work hours; HWTs) and examines their consequences for employees’ work engagement and psychological strain. Based on boundary theory and appraisal theories, we expected that positively appraised HWTs would relate to more engagement and less strain whereas negatively appraised HWTs would contribute to less engagement and more strain. We tested our hypotheses using two daily diary datasets from different Belgian companies, one collected before the COVID-19 pandemic during 13 workdays among 81 employees (678 observations; Study 1) and one collected during the pandemic during 9 workdays among 82 employees (516 observations; Study 2). Hypotheses were tested both on the within – and the between-person level using multilevel modelling to account for daily fluctuations in the appraisals of HWTs and between-person differences. As expected, positive appraisals were related to more engagement and less strain at the between-person level in both studies. We did not find this impact on the within-person level, nor did we find any within – or between-effects of negative appraisals. Our study highlights the relevance of positive appraisals for employees’ between-level engagement and strain beyond the impact of HWTs themselves.

The contemporary work landscape has given rise to an increased fusion between the work and home domains. The evolution of information and communication technology (ICT) has enabled employees to conduct their work anywhere at any time, and thus employees can stay continuously connected to their work using ICT (Allen et al., Citation2015). The collision between work and home is even more salient since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with an increasing number of employees working from home (Vaziri et al., Citation2020). Because of the blurring boundaries between home and work, employees are increasingly likely to make home-to-work transitions (HWTs) (Delanoeije et al., Citation2019; Voydanoff, Citation2005), that is, transitions from their home role to the work role during non-work hours (Delanoeije et al., Citation2019). Examples include checking one’s emails on the smartphone during dinner or working on a work-related presentation in the evening.

Research generally assumes HWTs to have negative consequences for employees. For instance, Delanoeije and colleagues (Citation2019) found that employees who made HWTs on a given day experienced more work-to-home conflict that day. Relatedly, Derks and colleagues (Citation2014) found that on days when employees used their smartphones for work-related purposes outside work hours, they had more difficulties psychologically detaching from their work and in turn experienced more emotional exhaustion. Similarly, research on supplemental work (i.e. work outside work hours) has found detrimental well-being outcomes of this behaviour, such as stress and mental illness (Ďuranová & Ohly, Citation2016). Explanations for such negative effects include that HWTs technically prolong people’s working days and enhance role blurring, which may, in turn, hinder recovery from work, facilitate stress-spillover effects, and foster confusion (Ashforth et al., Citation2000; Ďuranová & Ohly, Citation2016).

Nevertheless, some studies also found positive effects of HWTs. For instance, it has been found that for employees with an integration preference (i.e. who prefer blurred boundaries between work and home), more frequent HWTs were associated with lower work-family conflict (Derks et al., Citation2016; Gadeyne et al., Citation2018) and enhanced family performance (Derks et al., Citation2016). These studies argue that HWTs can be useful rather than hindering, for example when they allow people to finish work tasks or when they are essential to people’s work-home management strategy (e.g. interrupting work during the day to take care of some home responsibilities but compensating that by working in the evening).

In line with the latter explanation, it has been recently suggested that it is not perse the boundary-crossing interruption that has implications for employees’ well-being, but rather how that interruption is appraised by the employee (Hunter et al., Citation2019; Reinke & Ohly, Citation2021). This idea is in line with various theoretical perspectives, such as the transactional theory of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), the challenge – hindrance framework (LePine et al., Citation2005) and affective event theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996), which all state that people’s reactions (e.g. stress, affect, attitudes) are not so much triggered by environmental conditions or specific occurrences (e.g. HWTs), but rather by the degree to which these conditions or occurrences are appraised as useful or, conversely, as hindering. In line with this idea, Hunter and colleagues (Citation2019) found that when role transitions on a given day were appraised as obstructing one’s goals, they were associated with negative outcomes like lower satisfaction and more work-home conflict, but when they were appraised as facilitating, they enhanced people’s positive affect. In a similar vein, Reinke and Ohly (Citation2021) found that positively appraised role transitions on a given day were associated with more positive affect that day, whereas negatively appraised role transitions were linked with more negative affect and less detachment. Yet, scholars have only begun to examine the outcomes of appraisal-specific work-home interruptions for employees. It is therefore important to further explore whether positive and negative appraisals of HWTs matter for well-being outcomes.

In addition, the few studies on HWTs that explored the impact of appraisals to date focused on the within-person effects of appraisals. That is, they examined whether an employee experienced, for instance, more work-home conflict on days with more negatively and less positively appraised role transitions compared to days with less negatively and more positively appraised transitions. Yet, it is important to also explore between-person effects – i.e. differences between people depending on their average report of negatively/positively appraised HWTs – since these can capture the more enduring effect of people’s appraisals (Baethge et al., Citation2018). For instance, people may be well able to cope with a hindering HWT when it occurs once, but – since the effort needed to cope with demands cannot be sustained indefinitely (Hockey, Citation1997) – they may get tired and stressed when such transitions occur during several consecutive days. We will therefore examine both within – and between-person effects of positive and negative appraisals of HWTs.

Our ultimate goal is to further our understanding of the within-person and between-person effects of positive and negative appraisals of HWTs for two indicators of psychological well-being, namely psychological strain, and work engagement. In doing so, we aim to contribute to existing research on work-home interruptions in four ways. First, we build on the growing body of research that has emphasized the importance of appraisals when studying boundary-role transitions (Hunter et al., Citation2019; Reinke & Ohly, Citation2021). As the majority of studies on HWTs have investigated the outcomes of these transitions, less effort has been extended to examining the outcomes of appraisal-specific HWTs for employees. By disentangling positive and negative appraisals of HWTs and studying their outcomes for individuals’ psychological well-being, we address this issue. Second, no study, to the best of our knowledge, has investigated the influence of appraisal-specific HWTs on psychological well-being outcomes. Following recent research that focuses on both positive and negative perspectives of well-being in the workplace (Charalampous et al., Citation2019), we explore the effects of HWT appraisals for strain as well as work engagement. Third, we contribute to the literature by exploring both within-person and between-person effects of appraisals of HWTs. In that way, we can shed light on both immediate (i.e. within-effects) and more enduring effects (i.e. between-effects) of appraisals of HWTs. Finally, we test our hypotheses using two daily diary studies, one collected before the COVID-19 pandemic and one during, in that way testing the replicability of our findings in two settings.

Theoretical background

Work-home boundary role transitions and the role of appraisals

According to boundary theory, individuals create and maintain psychological, physical, and/or behavioural boundaries around their roles in different life spheres, such as work or home (Ashforth et al., Citation2000). When individuals make switches between roles in different life spheres, boundaries are crossed, which can either impair or enhance employees’ well-being.

Research on HWTs suggests that there are indeed both harms and benefits to making such boundary transitions. Whereas several studies have related HWTs with detrimental well-being outcomes, such as more psychological strain (Zhang et al., Citation2021), increased work-to-family conflict (Delanoeije et al., Citation2019), and impaired health (Derks et al., Citation2014; Ďuranová & Ohly, Citation2016), a growing number of studies have shown beneficial effects of HWTs for employees, ranging from increased work satisfaction (e.g. Diaz et al., Citation2012) to better work-life boundary management as a result of increased flexibility and control (Golden & Geisler, Citation2007). Relatedly, mentally transitioning from home tasks to work tasks before the workday has been linked with more daily work engagement, explained by increased positive affect, job control, social support, and anticipated work focus (Sonnentag et al., Citation2020). Building on these findings, we propose that the effects of HWTs are either positive or negative depending on how the transitions are appraised by the individual (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; LePine et al., Citation2005; Scherer et al., Citation2001; Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996).

Appraisals are cognitive processes by which employees ascribe meaning to situations (Scherer et al., Citation2001). When individuals interrupt their home activities to deal with work demands (i.e. when they make HWTs), this can be appraised in either a positive way when it was useful or negatively when it was dysfunctional or cognitively demanding. Although there are individual differences in appraisals – with some individuals being more prone to making positive appraisals whereas others are more tending towards negative appraisals (Scherer et al., Citation2001) – individuals' appraisals may also differ across days (Scherer et al., Citation2001). Put differently, while on some days a boundary violation at home from work (e.g. a phone call from a colleague outside work hours about a project) might be perceived as useful for the employee, on another day a similar phone call might be appraised negatively.

Individuals’ appraisals of a situation cause their emotional, affective, and physical reactions to that situation (Scherer et al., Citation2001). So, when a person appraises a situation negatively, it is likely to cause negative affective reactions, emotions, and attitudes whereas the reverse happens when the appraisals are positive. Indeed, results from a recent daily diary study showed that on days when individuals evaluated ICT-use after work hours as positive, they reported more positive affect, while negatively appraised ICT-use on a particular day was related to more negative affect (Reinke & Ohly, Citation2021). In what follows, we build hypotheses for the expected within-person and between-person effects of positively and negatively appraised WHTs for work engagement and psychological strain.

Positive and negative appraisals of role transitions and work engagement

Work engagement is an affective-motivational construct defined as a “positive, fulfilling work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006, p. 702). Work engagement has been shown to fluctuate within individuals and thus over short periods (i.e. state work engagement, see e.g. Sonnentag et al., Citation2020) and to also differ between individuals, which is commonly referred to as trait work engagement (see e.g. Halbesleben & Leiter, Citation2010). Scholars have argued that studying both state and trait work engagement is important if we are to better understand differences in their predictors (Breevaart et al., Citation2012). We therefore investigate the consequences of positively and negatively appraised HWTs for employees’ within-person (i.e. day-level) and between-person work engagement (i.e. mean level over the different days).

We, first of all, expect that work engagement will be higher on days when employees appraise HWTs more positively and lower on days when they appraise HWTs more negatively. Work engagement is highly dependent on affective states and mood (Bledow et al., Citation2011) as it is characterized by the presence of positive work-related feelings and the absence of negative feelings (Rich et al., Citation2010). On days when employees appraise HWTs more positively, this means that the extra time they have invested in their work after hours has been helpful and has facilitated their work goals on that particular day. As such, employees may experience more positive affective reactions (Hunter et al., Citation2019). Conversely, if employees experience HWTs as hindering, they may psychologically attribute blame for the interruption to their work role (Shockley & Singla, Citation2011). As such, employees may become dissatisfied and unhappy with their work (Gabriel et al., Citation2014; Zhao et al., Citation2019). Considering that positive and negative affect are important antecedents of work engagement (Bledow et al., Citation2011), we expect that employees will feel more engaged with work on days they experienced more positively appraised HWTs and less negatively appraised HWTs.

Hypothesis 1a: Daily positive appraisals of HWTs are related to more daily work engagement.

Hypothesis 1b: Daily negative appraisals of HWTs are related to less daily work engagement.

Hypothesis 2a: Between-level differences in daily positive appraisals of HWTs are related to more between-level work engagement.

Hypothesis 2b: Between-level differences in daily negative appraisals of HWTs are related to less between-level work engagement.

Positive and negative appraisals of role transitions and psychological strain

Psychological strain is the negative emotional or physical reactions of workers in response to situations that pose a threat (i.e. stressors; Bentley et al., Citation2016). Psychological strain has long been shown to have considerable consequences for employees’ well-being (e.g. burnout, see Cordes & Dougherty, Citation1993) as well as organizational implications, such as increased absenteeism and turnover (Darr & Johns, Citation2008), and thus has received increasing attention in research on employee well-being. Similar to work engagement, psychological strain shows in-person variations (i.e. day-to-day fluctuation) as well as between-person differences (e.g. Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Citation2020).

First, we propose that positive and negative appraisals of HWTs are associated with psychological strain at the within-person level. That is, we expect that on days when individuals experience less positively and more negatively appraised HWTs, they will experience more psychological strain. When individuals experience a HWT negatively, this means that the transition was disturbing and has prevented them from properly participating in their home activities. Such a transition is likely to be perceived as a situation that poses a threat, which may trigger a reaction of psychological strain. As such, on days employees experience more negatively appraised HWTs, they are likely to experience more strain. This expectation is in line with earlier research that has shown that on days employees experience more negative events, they report more psychological strain (Beattie & Griffin, Citation2014; Stawski et al., Citation2008). Positively appraised HWTs, on the other hand, are likely to decrease experiences of psychological strain. On days when employees appraise HWTs more positively, the HWTs have been helpful and have facilitated to achieve their work goals that day. This is likely to induce positive emotions and help to unwind afterward, which may both lower psychological strain (Pressman & Cohen, Citation2005). In line with this expectation, research has found that on days employees were better able to accomplish their work tasks, they experienced more positive affect (Gabriel et al., Citation2011) and felt more relaxed afterward (Hur et al., Citation2020). Building on the above, we formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: Daily positive appraisals of HWTs are related to less daily psychological strain.

Hypothesis 3b: Daily negative appraisals of HWTs are related to more daily psychological strain.

Finally, we expect that employees who experience less negatively and more positively appraised HWTs across several days will report on average less psychological strain across these days compared to employees who experience more negatively and less positively appraised HWTs. We thus assume that also the daily effects of appraisals on psychological strain will accumulate over time and translate into between-person differences in psychological strain. Employees who report negatively appraised HWTs across days experience hindering interruptions for work after hours day after day. Enduring exposure to hindering interruptions may not only result in accumulated strain but also decrease the likelihood that people can recover from the daily stress experiences. Therefore, employees who experience such an accumulation of hindering interruptions are likely to experience on average more psychological strain than employees who lack such experiences. Conversely, when employees report positively appraised HWTs across several consecutive days, they experience helpful HWTs day after day. This accumulation of helpful work experiences may enable individuals to absorb resource loss during stressful encounters (Hobfoll, Citation2002) and, therefore, to experience less psychological strain compared to individuals who experience less positively appraised HWTs across several consecutive days. We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 4a: Between-level differences in daily positive appraisals of HWTs are related to less between-level psychological strain.

Hypothesis 4b: Between-level differences in daily negative appraisals of HWTs are related to more between-level psychological strain.

Methodology

We tested our hypotheses in two different studies. One dataset was collected in the spring of 2017 (March – April) and one dataset was collected after the onset of COVID-19 in the spring of 2021 (May – June). Both datasets were collected with Belgian employees.

Procedure

STUDY 1. Daily diary data were collected using online questionnaires from a convenience sample of 81 Flemish employees with parental responsibility. Respondents first filled out a general survey with background information and three weeks later, they filled out short daily surveys during 14 consecutive workdays. Respondents were instructed to fill out the survey just before going to bed. Of 93 employees who filled out the first survey, 81 respondents filled out at least one of the daily surveys (response rate = 87%). Daily response rates varied from 30 to 79%, and respondents filled out the daily questionnaire between 1 and 14 times in total (M = 8.81, SD = 3.53), resulting in 678 out of 1134 possible observations (60%).

STUDY 2. Daily diary data were collected using online questionnaires from a sample of 82 employees from 11 different large construction and property development firms in Belgium, with four different main firms (14.6% of respondents of firm 1; 24.6% of firm 2; 22.5% of firm 3 and 17.2% of firm 4) and seven other firms (22.1% of respondents). The respondents were all working on the same project, i.e. there was a project-based collaboration between these companies. Employees devoted a certain amount of their time to the project and a certain amount of their time to other tasks within their organization. Respondents first filled out a general survey with background information (baseline survey; last two weeks of April) and around one month later (last week of May and first week of June), they filled out short daily surveys during nine consecutive workdays. Respondents were instructed to fill out the survey just before going to bed. Of 95 employees who were approached by the project-based organization, 82 employees (response rate = 86.3%) filled out the baseline survey, and 79 employees filled out at least one of the daily surveys (response rate = 83.2%). Daily response rates varied from 26 (Friday, June 4) to 69% (Tuesday, May 26), and respondents filled out the daily questionnaire between 1 and 9 times in total (M = 6.53, SD = 2.32), resulting in 516 out of 711 possible observations (72.6%).

Participants

STUDY 1. The majority of the sample was female (65%) and worked full time (76%); respondents were between 24 and 49 years old (M = 36.76, SD = 5.37). Official work hours per week ranged from 18 h to 40 h (M = 35.21, SD = 5.16). The sample consisted of 35% professional workers, 21% clerks, 20% middle managers and 25% had another function. Most respondents (i.e. 65%) telecommuted at least one day per week. Respondents had one to four children (M = 1.94, SD = 0.78) of which the youngest child was maximum 11 years old (M = 4.56, SD = 3.60). All respondents had a partner.

STUDY 2. The majority of the sample was male (89%), worked full-time (83.9%), and worked 75% to full-time on the project (69%). Specifically, respondents worked between 10 and 100% (M = 82.50, SD = 24.40) or between 4 and 80 h per week (M = 38.65, SD = 14.11) on the project. Respondents were between 24 and 63 years old (M = 40.82, SD = 9.73) and had zero to four children up to 21 years living in their household (M = 1.25, SD = 1.21), of which the youngest child was between 0 and 21 years old (M = 8.45, SD = 6.40). The majority of the respondents (86.4%) had a partner (missing data for 6.8% of the respondents). At the time of the data collection, all respondents worked from home most of the time.

Measures

Psychological strain. Psychological strain was measured with five items of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) of Goldberg and Hillier (Citation1979) that were adapted to the daily-level. A sample item is: “To which extent have you been nervous today?” (1: Totally not; – 7: Totally). Multilevel reliability, expressed in the generalizability coefficient of average time points across all items (Revelle & Wilt, Citation2019) was .89 in Study 1 and .92 in Study 2, with the daily Cronbach’s α ranging from .72 to .85 in Study 1 and from .79 to .88 in Study 2. Multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) showed that all factor loadings were between .61 and .79 (Study 1) and between .57 and .82 (Study 2), i.e. the latent factor explained between 37 and 62% (Study 1) and between 32 and 67% (Study 2) of the variance in the items (Brown, Citation2015).

Work engagement. Work engagement was measured with the three-item vigour scale of Schaufeli et al. (Citation2006), in which the items were adapted to the daily level. A sample item is: “Today at work, I felt bursting with energy” (1: Totally disagree; – 7: Totally agree). Generalizability coefficient of average time points across all items was .92 in Study 1 and .89 in Study 2, with daily Cronbach’s α ranging from .83 to .95. in Study 1 and from .74 to .87 in Study 2. MCFA showed that factor loadings were between .76 and .96 in Study 1 and between .60 and .86 in Study 2, i.e. the latent factor explained between 58 and 92% of the variance in the items in Study 1 and between 36 and 74% of the variance in the items in Study 2.

HWTs. To assess daily HWTs, we adapted four items from Matthews and colleagues’ (Citation2010) measure to the daily level. Respondents were asked to assess the following four items on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = Not applicable at all to 7 = Fully applicable): “Today, I answered to work-related calls or e-mails outside work hours’; “Today, I stopped what I was doing after work hours to call work or to send a work-related mail”; “Today, I changed plans at home to meet work-related responsibilities’; and “Today, I have gone in to work to meet work responsibilities outside work hours’. This measure of the daily HWTs is an index, as the four statements may not equally apply every day and, thus, do not necessarily correlate with each other on a daily basis (Bollen & Bauldry, Citation2011).

Positive appraisals. We measured positive appraisals using a self-developed three-item scale asking respondents to indicate the extent to which the experienced HWTs “were desirable”, “helped them to deal with certain issues or problems at work immediately” and “meant that [they] did not have to worry about these work matters afterwards’. Questions about positive appraisals were asked after individuals responded to the HWT items. Individuals were requested to skip the appraisal questions in cases when no daily transitions had occurred. The response scale ranged from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Completely). Multilevel reliability, expressed in the generalizability coefficient of average time points across all items was .79 in Study 1 and .79 in Study 2, with the daily Cronbach’s α ranging from .71 to .95 in Study 1 and from .58 to .90 in Study 2. Moreover, MCFA showed that all factor loadings were between .57 and .89 in Study 1 and between .58 and .87 in Study 2, i.e. the latent factor explained between 32 and 79% of the variance in the items in Study 1 and between 34 and 76% in Study 2.

Negative appraisals. Similarly, we measured negative appraisals using a self-developed scale asking respondents to indicate the extent to which the HWTs were experienced as “disturbing or inconvenient”, “prevented [them] from properly completing what [they] were doing at home” and “occurred unexpectedly”. Again, these questions were asked after individuals responded to the HWT items and individuals were requested to skip the appraisal questions in cases when no daily transitions had occurred. The response scale ranged from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Completely). Generalizability coefficient of average time points across all items was .76 in Study 1 and .85 in Study 2, with the daily Cronbach’s α ranging from .63 to .92 in Study 1 and from .58 to .87 in Study 2, with in Study 1 an exception of the 10th day of measurement, i.e. the second Friday of the data collection (Cronbach’s α = 0.56), and in Study 2 an exception of the 4th day of measurement, i.e. the first Friday of the data collection (Cronbach’s α = .51). Moreover, MCFA showed that all factor loadings were between .54 and .90 in Study 1 and between .53 and .87 in Study 2, i.e. the latent factor explained between 29 and 81% of the variance in the items in Study 1 and between 28 and 67% of the variance in the items in Study 2.

Within-person control variables. We controlled for two within-person variables, i.e. whether the respondent had worked from home that day (1: yes; 0: no) and the hours worked that day. We accounted for the impact of a teleworking day since it has been found an important predictor of HWTs (Delanoeije et al., Citation2019) and psychological strain and work engagement (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Citation2020). Likewise, the number of hours worked that day may impact the number of HWTs as well as their appraisals, and daily psychological strain and work engagement.

Between-person control variables. We controlled for five between-person differences likely to affect both our predictors and outcomes, i.e. whether or not the respondent could telework (1: yes, 0: no), job autonomy, home protection preference, gender (1: female, 0: male) and age. We included the trait-level variable of telework to make sure that the effect of the state-level variable of a teleworking day was not impacted by being a teleworker or not. Job autonomy (measured by the four-item scale of Kossek and colleagues (Citation2006); e.g. “My job permits me to decide on my own about when the work is done”) was included since WHTs are more likely in autonomous jobs (Kossek et al., Citation2006). The scale showed modest reliability (Study 1: Cronbach’s α = 0.63; Study 2: Cronbach’s α = .66). Home protection preference (measured with the four-item segmentation preference scale of Kreiner (Citation2006); e.g. “I prefer to keep work-life at work”) was included since we wanted to assess the impact of appraisals beyond this trait variable that is paramount when assessing the impact of HWTs on employee wellbeing (Kreiner, Citation2006). Cronbach’s α was 0.86 in both studies.

Analysis

We have a two-level model with repeated measurements (daily variables) at the first level and individuals at the second level (Study 1: N = 81 respondents and 678 occasions; Study 2: N = 82 respondents and 516 occasions). Since we have nested observations (i.e. days nested within employees), we used linear mixed coefficient modelling (MCM). We employed restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation, as REML does not expect all fixed effects to be known without errors and maximizes only the portion of the likelihood that does not depend on the fixed effects, which makes this method suitable for complex models including multiple fixed effects (Gilmour et al., Citation1995), like ours. We person-mean-centred our level 1 variables. This allowed us to assess respondents’ deviations from their individual mean (i.e. purely within-person effects). We also included the person-average of our three key variables on level 1, i.e. HWTs, positive appraisals, and negative appraisals, which we grand-mean-centered. This allowed us to assess respondents’ deviations from the general mean (i.e. between-person effects). We grand-mean-centred all level 2 variables.

Results

Descriptives and model comparison

The descriptive statistics of the variables in Study 1 and Study 2 can be found in the supplemental material (see Tables 3 and 4, respectively). and show the results of the multilevel analyses to predict work engagement (Model 1), and psychological strain (Model 2) for each study. In Study 1, as can be seen in , 46% of the variance in work engagement and 51% of the variance in psychological strain is due to daily (within-person) variation. In Study 2, as can be seen in , 44% of the variance in work engagement and 35% of the variance in psychological strain is due to daily (within-person) variation.

Table 1 . Random coefficient modelling results to predict daily work engagement (Model 1) and daily psychological strain (Model 2) in Study 1.

Table 2 . Random coefficient modelling results to predict daily work engagement (Model 1) and daily psychological strain (Model 2) in Study 2.

Furthermore, when predicting strain, in both studies, our full model including appraisals showed a better fit compared to the model without appraisals (Study 1: Δχ²(1) = 2.29; p < .01; Study 2: Δχ²(1) = 17.60; p < .01). This validates the importance of appraisals when predicting strain. However, when predicting engagement, model comparison only showed a better fit for our full model as compared to the model without appraisals in our second study (Δχ²(1) = 19.06; p < .01) and not in our first study (Δχ²(1) = 19.51; p = .10). This finding indicates that, aside from appraisals of HWTs, also other factors – which we did not test in our models – may be relevant when predicting daily work engagement.

Hypotheses testing

Hypothesis 1a predicted that daily positive appraisals would be related to more daily work engagement. Neither in Study 1 (γ = – 0.03, p = .37; , Model 1) nor in Study 2 (γ = 0.05, p = .12; , Model 1), the estimate of within-person positive appraisals was significant, thus this hypothesis was not supported. Hypothesis 1b predicted that daily negative appraisals would be related to less daily work engagement. Again, neither in Study 1 (γ = – 0.01, p = .68; , Model 1), nor in Study 2 (γ = 0.00, p = .85; , Model 1), the estimate of within-person negative appraisals on daily engagement was significant, hence hypothesis 1b was not supported.

Hypothesis 2a predicted that between-person positive appraisals, i.e. an individual’s accumulation of positive appraisals over all measurement occasions, would be related to more between-level work engagement. Both in Study 1 (γ = 0.32, p < .01; , Model 1) and in Study 2 (γ = 0.24, p < .01; , Model 1), the estimate of positive appraisals on work engagement on the between-person level was significant, supporting this hypothesis. Hypothesis 2b predicted that between-level negative appraisals would be related with less work engagement. However, neither in Study 1 (γ = 0.14, p = .09; , Model 1) nor in Study 2 (γ = – 0.07, p = .09; , Model 1), the estimate of negative appraisals on work engagement was significant at the between level, thus hypothesis 2b was not supported.

Hypothesis 3a predicted that daily positive appraisals would be related to less daily psychological strain. However, unlike hypothesized, we found no significant within-person effect of positive appraisals on strain on the within-person effect, neither in Study 1 (γ = 0.04, p = .23; , Model 2) nor in Study 2 (γ = 0.06, p = .07; , Model 2). Hypothesis 3b predicted that daily negative appraisals would be related to more daily strain. Again, neither in Study 1 (γ = 0.06, p = .08; , Model 2) nor in Study 2 (γ = 0.05, p = .10; , Model 2), the estimate of within-person negative appraisals on strain was significant, hence also hypothesis 3b was not supported.

Hypothesis 4a predicted that between-level positive appraisals would be related to less psychological strain. In both Study 1 (γ = – 0.30, p < .01; , Model 2) and Study 2 (γ = – 0.22, p < .05; , Model 2), we found a significant negative relationship between between-person positive appraisals and psychological strain, thus supporting hypothesis 4a. Hypothesis 4b predicted that between-level negative appraisals would be related to more between-level psychological strain. Neither in Study 1 (γ = 0.14, p = .09; , Model 2) nor in Study 2 (γ = 0.14, p = .13; , Model 2), the effect of between-level negative appraisals on strain was significant, thus hypothesis 4b was not supported.

Post-hoc analyses

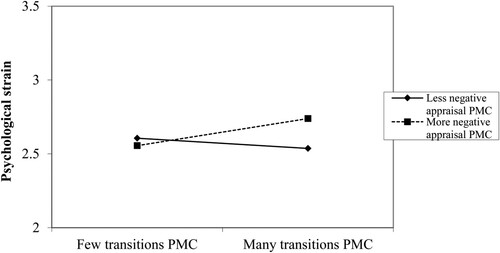

Since it could be argued that appraisals may matter most when employees made more HWTs on a given day, we performed additional analyses to explore whether appraisals moderated the relationship between HWTs and employees’ psychological strain and work engagement. We, therefore, performed multilevel moderation analyses in which we included the interaction of HWTs and both positive and negative appraisal, and this both on the within-person level and on the between-person level. The results can be found in the supplemental material published together with the current article. We only found one significant moderation effect (see ). In particular, in Study 1, we found that the relationship between daily HWTs and daily psychological strain depended on the degree of negative appraisal on that day (γHWT*negative appraisal = 0.06, p = .03;), in the sense that the relationship between daily HWTs and daily psychological strain was more positive on days when employees reported more negative appraisals than on days when they reported less negative appraisals. We could not replicate this interaction effect in Study 2. In addition, none of the other interaction terms were significant, neither on the within-person or on the between-person level (see Tables 5 and 6 in the supplemental material).

Discussion

The current paper set out to investigate differences in the consequences of positive and negative reactions to HWTs for employees’ psychological strain and work engagement. Drawing on boundary theory (Ashforth et al., Citation2000) and appraisal theories (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; LePine et al., Citation2005; Scherer et al., Citation2001; Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996), we argued that transitions from home tasks to work tasks are not harmful perse, but rather that their effect on well-being depends on how the transition is appraised. Specifically, we expected that positively appraised HWTs would increase experiences of work engagement and decrease psychological strain and that negatively appraised HWTs would negatively affect employees’ work engagement and increase psychological strain at both the within level (i.e. day level) and the between level. Our results partially supported our hypotheses.

First, in line with our theoretical reasoning and appraisal theories, our findings suggest that the appraisals of HWTs matter more than the role transitions themselves. HWTs were neither related to engagement nor strain in our first study (i.e. conducted across companies before the pandemic) and only related to psychological strain at the between-person level in our second study (i.e. conducted across a limited number of companies during the pandemic), whereas positive appraisals were related with both work engagement and psychological strain on the between-person level in both studies. These findings thus support the importance of appraisals, but at the same time show that transitions can have an impact over and above the impact of appraisals – as was the case in our second study.

Despite this general support for the importance of appraisals, our analyses also suggest that the role of appraisals depends on the specific outcome under study and on the sample characteristics. Specifically, when predicting strain, in both studies, our full model including appraisals showed a better fit compared to the model without appraisals. This finding emphasizes the importance of appraisals when predicting strain. Yet, the findings were slightly different for work engagement. That is, when predicting engagement, model comparison only showed a better fit for our full model as compared to the model without appraisals in our second study and not in our first study. This suggests that when studying HWTs and their appraisals across a larger number of organizations and during a pandemic situation, other factors aside from appraisals of HWTs may be relevant when predicting daily work engagement.

Second, across the two studies, appraisals of HWTs appeared not to influence employees’ engagement and strain on the day level (although some effects were marginally significant), but only on the between level. That is, respondents were found to differ in strain and work engagement depending on their average appraisals of HWTs across multiple days. These findings challenge theoretical assumptions from appraisal theories (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; LePine et al., Citation2005; Scherer et al., Citation2001; Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996) and recent studies that have shown how daily evaluations (i.e. either positive or negative) of role transitions impact well-being on a day-to-day basis (Hunter et al., Citation2019; Reinke & Ohly, Citation2021). One possible explanation could be the temporal distance in the experience of the transitions and our outcomes variables in comparison to those used in previous research. Reinke and Ohly (Citation2021) for instance, found immediate effects (i.e. within-person) of positive and negative appraisals of role transitions when linking them to affective states and psychological detachment, the latter of which could be identified as momentary variables (Tadić et al., Citation2015; Zhou et al., Citation2015). Although both work engagement (Bakker, Citation2014) and psychological strain (Beattie & Griffin, Citation2014) have been shown to fluctuate daily and thus over short periods, it could be that they are less affected by single events occurring on a specific day, but are only affected when these events (positive or negative) occur repeatedly across several days. It could also be that work engagement and psychological strain are more prone to stable work-related or private-related variables differing between employees, or being impacted through other work-related or private-related variables throughout the day. Since our results indicate 60% of variance that is due to between-person differences, other between-person factors not included in our study may account for this. In addition, since 40% of the variance of work engagement is due to within-person factors, but none of our within-person HWTs or appraisals were significant, this could indicate other daily variables accounting for other effects in this study.

Third, our findings only showed an impact of positive – and not of negative – appraisals and only at the between-level. This indicates that individuals are only affected when they have positive HWT-related experiences across several days, but not when these experiences are negative. This is in line with a resource-gain, work-home enrichment perspective, which emphasizes that enrichment occurs when addressing demands in one domain (e.g. work) positively impacts the experiences in the other domain (e.g. home) (Greenhaus & Powell, Citation2006). Research has shown beneficial effects of combining work and home demands on employees’ work engagement (e.g. Siu et al., Citation2010) and psychological strain (e.g. Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Citation2020). In line with these work-home enrichment perspectives, our results show that the positive appraisals of HWTs may function as an engagement-increasing and strain-decreasing resource.

Interestingly, we did not find evidence for the contrary, i.e. we do not find impacts of negative appraisals. Negative appraised interruptions of leisure time to address work therefore may not deplete resources and hence, our findings on negative appraisals of HWTs do not seem to fit within a work-home conflict perspective (e.g. Carlson & Kacmar, Citation2000). However, results in our second study did show a strain-increasing impact of the mere occurrence of HWTS – irrespective of their appraisals – which further nuances the role of HWTs as resource-depleting transitions. This finding may indicate the problem of such transitions during a pandemic situation where employees are obliged to work from home, which may not offer the optimal context to combine work and home roles. Indeed, earlier studies have shown the importance of employees’ preferences concerning the place of work (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Citation2020) and the adverse impacts of prolonged teleworking (Golden et al., Citation2008). The lack of effects of negative appraisals may also indicate that HWTs in themselves may imply some negative effects (e.g. reduced time for leisure activities), without an additional impact of the negative appraisals beyond the interruptions. This reasoning may explain why our results did show marginal significant effects in line with our expectations for within-level negative appraisals on strain in our two studies, as well as for between-level negative appraisals on strain in our first study and engagement in our second study.

Finally, another possible explanation for the non-findings of appraisals of HWTs on the outcome variables at the day level might be that our model primarily focused on the main effect of appraisals on psychological strain and engagement, beyond the frequency of HWTs. That is, it could be that the effects of appraisals are dependent on how many daily transitions individuals make from home to work, such that the relationship between appraisals and the outcome variables is less strong when HWTs are few and stronger when HWTs occur frequently. Our supplementary analyses found support for one significant interaction effect. Specifically, the moderation results from Study 1 showed that negative appraisals have an impact on psychological strain only when individuals make many transitions from home to work. That is, when HWTs are few, the negative appraisals of HTWs are less problematic. While this finding points us to the importance of considering the interaction between frequency and appraisals of daily HWTs, our non-significant findings for the other interaction open up avenues for research to explore other factors that may moderate the relationship between appraisals and well-being outcomes, such as daily work or home demands.

Limitations and future research

Our study has a number of limitations. First, all measures were self-reported which may increase chances of common-method bias (Siemsen et al., Citation2010). However, considering that appraisals are based on cognitive processes by individuals themselves, it would not be feasible to collect multisource data for this particular construct. Yet, future research looking into the consequences of appraisals could include both self-and spouse reports of employees’ work-related well-being in their model.

Second, although we have used a longitudinal approach in measuring our variables by adopting a diary study, we are unable to infer causality from our findings because of the way our data were collected and analyzed (Taris et al., Citation2021). That is, appraisals of HWTs, psychological strain, and work engagement were all measured at the same moment, i.e. at the end of the day. We recommend future research to address this limitation by setting up a cross-day design to infer directionality and shed light on the potential enduring effects of role transition appraisals. Researchers could, for instance, measure appraisals of HWTs in the evening and capture employees’ experiences of work-related well-being the next morning. In this way, researchers can model across-time changes and increase the ability to establish causality (Taris et al., Citation2021).

Third, we acknowledge that there are limitations to the generalizability of our findings. In particular, our non-finding of the impact of negative appraisals on employees’ work-related well-being might be influenced by the context of our samples. Across both datasets (i.e. one before the COVID-19 pandemic and one during), employees worked from home on a regular basis and thus were likely used to the boundary permeability of their home and work domains. One could argue that these employees are therefore also familiar with interruptions of work at home and thus are less impacted when they appraise these interruptions as negative. It would be interesting to investigate the proposed relationships in our model among employees working in traditional workplaces, where working from home is not promoted, as their work-home boundary is less likely to be permeable.

Fourth, our understanding of the consequences of home-to-work appraisals for employees’ work-related well-being is limited as we did not explore mechanisms that could explain these relationships. In line with previous research on the effects of appraisals of role transitions (see Hunter et al., Citation2019; Reinke & Ohly, Citation2021), we argued in our theoretical reasoning that appraisals give rise to affective emotions (i.e. positive versus negative) which eventually impact employees’ experiences of work-related well-being. It would be a fruitful avenue for future research to empirically investigate these pathways.

Finally, in our model, we only shed light on the impact of appraisals on employees’ work-related well-being. Yet, we know from previous research that work-home boundary transitions also have important implications for the family domain (e.g. work-family conflict, see Delanoeije et al., Citation2019). It would be valuable to extend our model and explore outcomes related to family behaviours at home (e.g. marital withdrawal behaviour). This is particularly important in light of recent research that calls for more studies that consider the intersection of work and non-work and thereby take a whole-life perspective (e.g. Hirschi et al., Citation2020)

Practical implications

The findings of our study have practical implications for both employees and employers. Most of the research on transitions from home to work has highlighted the detrimental effects on employees’ well-being, such as reduced psychological detachment (e.g. Derks et al., Citation2014), increased work-family conflict (Delanoeije et al., Citation2019), and stress (e.g. Ďuranová & Ohly, Citation2016). Consequently, some employers have started implementing company-wide policies aimed at limiting or even prohibiting ICT use after hours (Reinke & Ohly, Citation2021). Yet, our results suggest that when HWTs are appraised positively, they can foster employees’ work engagement. Hence, we recommend organizations to think of strategies that can promote employees’ positive experience of HWTs instead of banning after-work communications altogether. For instance, employers could offer trainings in which they inform employees about the consequences of HWTs and encourage their employees to prioritize interruptions from work at home that are beneficial for them.

Funding details

This work was supported by the Internal Funds KU Leuven under Grant 3H200323; and Research Foundation Flanders under Grants 12B0522N and G075419N.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, T., Golden, T., & Shockley, K. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(2), 40–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100615593273

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day's work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. The Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. https://doi.org/10.2307/259305

- Baethge, A., Vahle-Hinz, T., Schulte-Braucks, J., & van Dick, R. (2018). A matter of time? Challenging and hindering effects of time pressure on work engagement. Work & Stress, 32(3), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1415998

- Bakker, A. B. (2014). Daily fluctuations in work engagement. European Psychologist, 19(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000160

- Beattie, L., & Griffin, B. (2014). Day-level fluctuations in stress and engagement in response to workplace incivility: A diary study. Work & Stress, 28, 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2014.898712

- Bentley, T. A., Teo, S. T., McLeod, L., Tan, F., Bosua, R., & Gloet, M. (2016). The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach. Applied Ergonomics, 52, 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2015.07.019

- Bledow, R., Schmitt, A., Frese, M., & Kühnel, J. (2011). The affective shift model of work engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1246–1257. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024532

- Bollen, K. A., & Bauldry, S. (2011). Three Cs in measurement models: Causal indicators, composite indicators, and covariates. Psychological Methods, 16(3), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024448

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Hetland, J. (2012). The measurement of state work engagement. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000111

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford publications.

- Carlson, D. S., & Kacmar, K. M. (2000). Work–family conflict in the organization: Do life role values make a difference? Journal of Management, 26(5), 1031–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600502

- Charalampous, M., Grant, C. A., Tramontano, C., & Michailidis, E. (2019). Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1541886

- Cordes, C. L., & Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and an integration of research on job burnout. The Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 621–656. https://doi.org/10.2307/258593

- Darr, W., & Johns, G. (2008). Work strain, health, and absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(4), 293. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012639

- Delanoeije, J., & Verbruggen, M. (2020). Between-person and within-person effects of telework: A quasi-field experiment. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(6), 795–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1774557

- Delanoeije, J., Verbruggen, M., & Germeys, L. (2019). Boundary role transitions: A day-to-day approach to explain the effects of home-based telework on work-to-home conflict and home-to-work conflict. Human Relations, 72(12), 1843–1868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718823071

- Derks, D., Bakker, A. B., Peters, P., & van Wingerden, P. (2016). Work-related smartphone use, work–family conflict and family role performance: The role of segmentation preference. Human Relations, 69(5), 1045–1068. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715601890

- Derks, D., Van Mierlo, H., & Schmitz, E. B. (2014). A diary study on work-related smartphone use, psychological detachment and exhaustion: Examining the role of the perceived segmentation norm. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035076

- Diaz, I., Chiaburu, D. S., Zimmerman, R. D., & Boswell, W. R. (2012). Communication technology: Pros and cons of constant connection to work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 500–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.08.007

- Ďuranová, L., & Ohly, S. (2016). Persistent work-related technology use, recovery and well-being processes: Focus on supplemental work after hours. In Persistent work-related technology use, recovery and well-being processes (pp. 61–92). Springer.

- Gabriel, A. S., Diefendorff, J. M., Chandler, M. M., Moran, C. M., & Greguras, G. J. (2014). The dynamic relationships of work affect and job satisfaction with perceptions of fit. Personnel Psychology, 67(2), 389–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12042

- Gabriel, A. S., Diefendorff, J. M., & Erickson, R. J. (2011). The relations of daily task accomplishment satisfaction with changes in affect: A multilevel study in nurses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 1095. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023937

- Gadeyne, N., Verbruggen, M., Delanoeije, J., & De Cooman, R. (2018). All wired, all tired? Work-related ICT-use outside work hours and work-to-home conflict: The role of integration preference, integration norms and work demands. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 107, 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.03.008

- Gilmour, A. R., Thompson, R., & Cullis, B. R. (1995). Average information REML: An efficient algorithm for variance parameter estimation in linear mixed models. Biometrics, 1440–1450.

- Goldberg, D. P., & Hillier, V. F. (1979). A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 9(1), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700021644

- Golden, A. G., & Geisler, C. (2007). Work–life boundary management and the personal digital assistant. Human Relations, 60(3), 519–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707076698

- Golden, T., Veiga, J., & Dino, R. (2008). The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: Does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication-enhancing technology matter?. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1412–1421. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012722

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379625

- Halbesleben, J. R., & Leiter, M. P. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker (Ed.), Work engagement (pp. 102–117). Psychology Press.

- Hirschi, A., Steiner, R., Burmeister, A., & Johnston, C. S. (2020). A whole-life perspective of sustainable careers: The nature and consequences of nonwork orientations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103319

- Hobföll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307

- Hockey, G. (1997). Compensatory control in the regulation of human performance under stress and high workload: A cognitive-energetical framework. Biological Psychology, 45, 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-0511(96)05223-4

- Hunter, E. M., Clark, M. A., & Carlson, D. S. (2019). Violating work-family boundaries: Reactions to interruptions at work and home. Journal of Management, 45(3), 1284–1308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317702221

- Hur, W.-M., Shin, Y., & Moon, T. W. (2020). How does daily performance affect next-day emotional labor? The mediating roles of evening relaxation and next-morning positive affect. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 25(6), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000260

- Kossek, E. E., Lautsch, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work–family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.07.002

- Kreiner, G. E. (2006). Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(4), 485–507. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.386

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- LePine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & LePine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 764–775. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.18803921

- Matthews, R., Barnes-Farrell, J., & Bulger, C. (2010). Advancing measurement of work and family domain boundary characteristics. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.05.008

- Pressman, S. D., & Cohen, S. (2005). Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 925–971. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925

- Reinke, K., & Ohly, S. (2021). Double-edged effects of work-related technology use after hours on employee well-being and recovery: The role of appraisal and its determinants. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, 35(2), 224–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002221995797

- Revelle, W., & Wilt, J. (2019). Analyzing dynamic data: A tutorial. Personality and Individual Differences, 136, 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.020

- Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.51468988

- Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Bakker, A. B. (2006). Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde: On the differences between work engagement and workaholism. Research Companion to Working Time and Work Addiction, 193–217.

- Scherer, K. R., Schorr, A., & Johnstone, T. (2001). Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. Oxford University Press.

- Shockley, K. M., & Singla, N. (2011). Reconsidering work—family interactions and satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 37(3), 861–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310394864

- Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 456–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109351241

- Siu, O. L., Lu, J. F., Brough, P., Lu, C. Q., Bakker, A. B., Kalliath, T., … Shi, K. (2010). Role resources and work–family enrichment: The role of work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.06.007

- Sonnentag, S., Eck, K., Fritz, C., & Kühnel, J. (2020). Morning reattachment to work and work engagement during the Day: A look at Day-level mediators. Journal of Management, 46(8), 1408–1435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319829823

- Stawski, R. S., Sliwinski, M. J., Almeida, D. M., & Smyth, J. M. (2008). Reported exposure and emotional reactivity to daily stressors: The roles of adult age and global perceived stress. Psychology and Aging, 23(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.52

- Tadić, M., Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. (2015). Challenge versus hindrance job demands and well-being: A diary study on the moderating role of job resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(4), 702–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12094

- Taris, T. W., Kessler, S. R., & Kelloway, E. K. (2021). Strategies addressing the limitations of cross-sectional designs in occupational health psychology: What they are good for (and what not). Work & Stress, 35(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2021.1888561

- Vaziri, H., Casper, W. J., Wayne, J., & Matthews, R. (2020). Changes to the work–family interface during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining predictors and implications using latent transition analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(10), 1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000819

- Voydanoff, P. (2005). Consequences of boundary-spanning demands and resources for work-to-family conflict and perceived stress. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.491

- Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1–74.

- Zhang, N., Shi, Y., Tang, H., Ma, H., Zhang, L., & Zhang, J. (2021). Does work-related ICT use after hours (WICT) exhaust both you and your spouse? The spillover-crossover mechanism from WICT to emotional exhaustion. Current Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01584-z

- Zhao, J. L., Li, X. H., & Shields, J. (2019). Managing job burnout: The effects of emotion-regulation ability, emotional labor, and positive and negative affect at work. International Journal of Stress Management, 26(3), 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000101

- Zhou, Z. E., Yan, Y., Che, X. X., & Meier, L. L. (2015). Effect of workplace incivility on end-of-work negative affect: Examining individual and organizational moderators in a daily diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(1), 117–130.