ABSTRACT

Studies investigating the stressor–strain relation using daily diary designs have been interested in within-person deviations that predict well-being outcomes on the same day. These models typically have not accounted for the possibility of short-term accumulation (i.e. previous stressor experiences having a lasting effect and affecting strain on subsequent occasions) and sensitisation (i.e. previous stressor experiences amplifying subsequent reactions to stressors) effects of stressors such as workload across days. In this study, we test immediate, accumulation, and sensitisation effects of workload on fatigue within and across days using four diary studies (mean observations = 1,406; mean N = 166). In all four studies, we observed that workload had positive concurrent effects on fatigue. In addition, we found that workload had positive effects on fatigue within one day. However, there was insufficient support for short-term accumulation or sensitisation effects, implying that higher levels of workload on previous days did not directly affect or amplify the effect of workload on fatigue on that day. We discuss implications for recovery theories and potential future avenues to refine the theoretical propositions that describe intra-individual stress and recovery processes across days.

Employee well-being is an important antecedent of work performance and has significant implications for individual, organisational, and societal functioning (Wright & Cropanzano, Citation2000). An increasing number of studies have used diary designs to investigate the temporal dynamics of stress processes and employee well-being (Podsakoff et al., Citation2019). Typically, such studies have been interested in how within-person fluctuations of stressors predict strain outcomes on the same day, offering explanations as to when and why well-being deviates from its usual level. An underlying assumption of this approach is that repeated experience of these deviations may alter well-being over time; consequently, daily diary studies can provide information on the mechanisms that potentially lead to long-term changes in well-being. Therefore, testing for the possibility of events having a lingering effect and affecting employee well-being across days may provide insights that could be crucial to understanding how daily fluctuations manifest into well-being impairments over time.

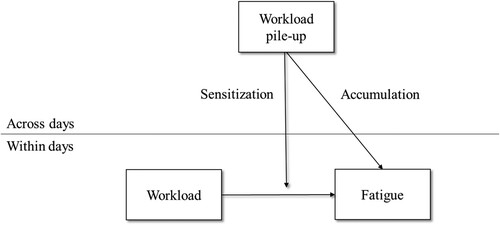

There are two theoretical perspectives on how the stressor–strain relation may evolve over short time periods. Some theories such as the initial impact model (Frese & Zapf, Citation1988) assume that employees immediately react to stressors with heightened levels of strain. As soon as the stressor is removed, strain levels and activation return to their base level (McEwen, Citation1998). These models imply that there are concurrent positive relationships between job stressors and strain, but not necessarily lagged relationships (e.g. from previous day’s job stressors to current strain). Other theoretical positions assume that exposure to stressors may accumulate over time. For example, Meijman and Mulder (Citation1998) assume that exposure to high workload leads to insufficient time to recover which may increase the intensity of subsequent load reactions. This implies that we may observe lagged relationships between job stressors and strain (accumulation), but more importantly, that the exposure to job stressors on previous days may amplify the reaction to job stressors (sensitisation). In this paper, we compare these different temporal models of how the stressor–strain relation may evolve within and across days. To test the relevance of the different theoretical propositions, we use four daily diary studies to assess a prototypical stressor (workload) and strain outcome (fatigue; see ).

Figure 1. Theoretical model on the proposed relations between workload and fatigue within and across days.

Our research makes both theoretical and methodological contributions to the stress and recovery literature. By comparing different perspectives on how job stressors affect employees’ well-being within and across days, we respond to the call to pay more attention to temporal issues in order to extend our knowledge of the temporal dynamic of the stressor–strain relation (Sonnentag, Citation2012; Sonnentag et al., Citation2017). Previous stress research using diary study designs has mainly focused on immediate effects or effects within one day, offering valuable insights into the linkages between daily work experiences and well-being fluctuations (Ilies, Aw, et al., Citation2015). In this study, we test two alternative models – namely, accumulation and sensitisation models (Frese & Zapf, Citation1988; Meijman & Mulder, Citation1998) – that have been developed to explain intra-individual processes within and across days. These models serve to temporally expand the investigation of the dynamic interplay between work experiences and well-being across days in the hopes of offering explanations as to why daily stressors not only affect employees’ health in the short run, but may also trigger a loss spiral leading to health impairments in the long run. To increase the generalizability, reliability, and hence confidence in our conclusions, we have cross-validated our findings using four samples.

Workload and fatigue

Prominent frameworks, such as the effort-recovery model (Meijman & Mulder, Citation1998), the job demands-resources model (Demerouti et al., Citation2001), and the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989), postulate that stressors such as workload require physical and psychological resources because employees need to invest energy and effort to deal with the stressors. These investments leave employees feeling drained and lacking energy. Research has shown support for this assumption across various studies for multiple stressors (for meta-analytic results of between – and within-person effects; see Pindek et al., Citation2019).

One of the stressors employees report being exposed to most frequently is workload (Bowling et al., Citation2015), which is described as “having high amounts of work, having to work fast, and working under time pressure” (Ilies, Huth, et al., Citation2015, p. 2). Previous daily diary studies have demonstrated that workload varies substantially across working days and that high workload is negatively related to employee affective (e.g. distress), cognitive (e.g. detachment), and physiological (e.g. blood pressure) reactions (Baethge et al., Citation2018; Ilies et al., Citation2010; Teuchmann et al., Citation1999; Zohar et al., Citation2003). Theoretically and empirically, fatigue is a relevant outcome of workload. Work fatigue refers to the drainage of resources, which leads to tiredness, reduced functional capacity, and the feeling of a need to recover at the end of the workday (Frone & Tidwell, Citation2015; Ilies, Huth, et al., Citation2015; Sonnentag & Zijlstra, Citation2006). It is a central component in models of employee well-being and health (e.g. Demerouti et al., Citation2001) and has shown considerable variation within and across workdays (Cranford et al., Citation2006; Hülsheger, Citation2016; Ilies, Huth, et al., Citation2015). As such, fatigue offers a mechanism between job stressors and well-being.

However, there is a lack of understanding of the temporal pattern of the relationship between workload and fatigue. It has been argued that employees are confronted not only with present stressors, but also with residual stress from past stressors. Hence, the effects of workload may differ depending on frequency and exposure time (McGrath & Beehr, Citation1990). Considering the temporal pattern of workload, in the following sections, we theorise on immediate, accumulation, and sensitisation effects.

Temporal pattern of workload – fatigue within one day

A key assumption is that daily stressors have an immediate effect on employees’ functioning on the day they occur. For example, the initial impact model (Frese & Zapf, Citation1988; Garst et al., Citation2000) proposes that stressors have an immediate effect on strain. According to this model, strain increases with increasing stressors because one must also invest resources to cope with the stressors. This model is especially relevant to diary research in which stressors and strains are measured on the same day. For example, daily diary studies report effects from workload experienced during the workday on strain outcomes such as distress, fatigue, and blood pressure the same day (e.g. Baethge & Rigotti, Citation2013; Ilies et al., Citation2010; Smit & Barber, Citation2016). We, therefore, propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. In line with the initial impact model, workload has a positive effect on fatigue within the same day.

Temporal pattern of workload – fatigue across days

To understand long-term adaptation, the lack thereof, and the consequences for well-being, researchers have investigated daily stressors and strains, hoping to find mechanisms that explain how daily stressors and strain reactions accumulate and turn into chronic stressors and strain reactions (Almeida, Citation2005; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). One assumption is that stressors not only have an effect on the day they were experienced, but also carry forward and have an effect across days. Hence, fatigue on one day may be affected not only by experiences on that day, but also by previous experiences and exposures to workload. This theoretical position is captured in accumulation and sensitisation models (Frese & Zapf, Citation1988; Gump & Matthews, Citation1999; Wickham & Knee, Citation2013). These models propose that previous experiences of stressors may have a direct (accumulation) or moderating (sensitisation) effect on strain.

The effect of exposure to workload on previous days may linger and accumulate across days, capturing the idea that experiences can have immediate effects but that those effects can also carry forward. Accumulation across multiple days may occur due to the lack of recovery after exposure to the stressor; in effect, the resources depleted due to job stressors were not fully restored (Sonnentag & Fritz, Citation2015). Reduced opportunities to recover may occur because employees facing high workload work harder and longer, which in turn impairs their ability to recover outside of work (Baethge et al., Citation2019). Hence, not only single occurrences of stressors may have an impact on employees, their temporal spacing may also play a role if components of the stress process start to overlap (exposure, reaction, recovery; Schilling et al., Citation2022). As a consequence, the impact of a job stressor increases over time, and even after the stressor is reduced or no longer present, strain remains heightened (Dormann & van de Ven, Citation2014); hence the stressor, and reactions to it, start to accumulate and pile up.

Previous research has demonstrated accumulation effects at the between-person level or over long time periods such as five or ten years (e.g. Garst et al., Citation2000; Igic et al., Citation2017). Some daily diary studies have explored the effects of exposure to various life stressors and found accumulation effects over one week and within one day (Schilling & Diehl, Citation2014; Schilling et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, these studies cannot shed light on whether the accumulation is driven by accumulation across different life domains (i.e. work and private stressors) or the temporal spacing of stressors. Within the work domain, we are not aware of any study investigating such effects; however, some studies found that job stressors can reach across days. For example, Nicholson and Griffin (Citation2015) showed negative effects of incivility on end-of-day well-being and next-day recovery levels, and Park and Kim (Citation2019) reported negative effects of customer mistreatment on next-morning recovery.

According to accumulation models, effects of previous experiences of workload may persist across days even if workload on that day is lower (Dormann & van de Ven, Citation2014; Frese & Zapf, Citation1988). To test these effects, we create a pile-up index variable of workload, capturing workload experiences prior in the work week, to predict fatigue over and above workload experienced on the same day.

Hypothesis 2. In line with accumulation models, pile-up of workload has a positive effect on fatigue over and above workload on that day.

To the best of our knowledge, research on the sensitisation effects of job stressors has been scarce. In a study with accountants, Teuchmann et al. (Citation1999) compared the effect of a two-week period of high workload against regular workweeks. The authors compared the amount of explained variance in affect and exhaustion across two path models and concluded that job characteristics explained employee well-being better during the period with sustained high workload. This finding lends indirect support for the proposition that employees may become sensitised during a period of sustained high workload.

Parallel to accumulation effects, we will test sensitisation effects using the workload pile-up index.

Hypothesis 3. In line with sensitisation models, workload pile-up moderates the positive relationship between workload and fatigue within one day such that the relationship is stronger at higher levels of workload pile-up.

Method

We investigated the hypotheses using four daily diary samples that followed the same procedure. We first administered a baseline questionnaire, which was followed by daily assessments for two weeks (10 workdays). All four samples included participants with various occupational backgrounds (e.g. variety of industries, professions, and hierarchy levels). For Sample 2, ethical approval was obtained from the local institution (Ethics Committee Psychology, University of Groningen, 17161-O) prior to data collection. For Sample 1, 3, and 4 no institutional ethics committee was available at the time, however, the studies were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Sample 1. Participants were recruited by students as a part of their Master’s thesis research project (for a critical discussion on advantages and disadvantages of this procedure see Demerouti & Rispens, Citation2014). To be eligible for the study, participants were required to work at least 21 h per week (50% of full-time employment). The baseline questionnaire was completed by 127 participants, who all also completed daily questionnaires. Participants were asked to fill in questionnaires three times a day: one in the morning (not used for this study), one in the afternoon approximately 1.5 h before the end of work, and one at the end of the workday. On average, the participants completed 8.80 (SD = 1.64) afternoon questionnaires, and 9.67 (SD = 0.83) end-of-workday questionnaires. Participants were 35.6 years old (SD = 11.46), 45% were female, and worked 38.6 h per week (SD = 5.84).

Sample 2. Participants were recruited using a research panel company. To be eligible for the study, participants were required to be fully employed. The baseline questionnaire was completed by 312 participants, 272 of whom also completed daily questionnaires. Participants were asked to fill in questionnaires twice a day: one in the early afternoon and one at the end of the workday. On average, the participants completed 6.2 (SD = 3.65) afternoon questionnaires and 7.6 (SD = 3.05) end-of-workday questionnaires. Participants were 46.5 years old (SD = 10.53), 47% were female, and worked 39.7 h per week (SD = 4.21).

Sample 3. As in Sample 1, students recruited participants working at least 21 h per week (50% of full-time employment). The baseline questionnaire was completed by 131 participants, who all completed daily questionnaires. Participants were asked to fill in questionnaires three times a day: one in the morning (not used in this study), at the end of the workday, and at bedtime (not used in this study). On average, the participants completed 7.5 (SD = 2.28) end-of-workday questionnaires. Participants were 33.4 years old (SD = 12.6), 64% were female, and worked 36.1 h per week (SD = 7.05).

Sample 4. Participants were recruited through online newsletters and social media. In addition, members of a study participant pool were contacted, and students recruited eligible participants from their personal networks. To be eligible for the study, participants were required to work at least 33 h per week (80% of full-time employment). The baseline questionnaire was completed by 150 participants, 146 of whom also completed daily questionnaires. Participants were asked to fill in one questionnaire in the morning (not used in this study), at the end of the workday, and at bedtime (not used in this study). Participants were asked to continue taking the daily survey until they completed the study (defined as having 10 days of data with at least two surveys filled in). On average, the participants completed 9.3 (SD = 1.53) end-of-workday questionnaires. Participants were 34 years old (SD = 9.7), 53% were female, and worked 40.4 h per week (SD = 5.3).

Measures

gives an overview of the measures used across the four studies, including reliability estimates. As recommended, we report omegas for the daily measures (Geldhof et al., Citation2014).

Table 1. Measures for the four studies.

Daily workload. The studies used items originally developed by Semmer et al. (Citation1995), but adapted to the daily context. An example item is: “Today, a fast pace of work was required.”

Daily fatigue. The four studies used three different measures to assess daily fatigue. A sample item is: “This evening, to what extent do you feel mentally exhausted?” adjusted from Frone and Tidwell (Citation2015).

Analytical procedure

To test the within-person effects, we applied hierarchical linear modelling using Mplus 8 to account for the nested data structure (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2017). Daily workload was modelled as a predictor of fatigue at Level 1. To test the accumulation and sensitisation effects of previous workload experiences, we created a workload pile-up index variable. First, we person-mean centred workload to remove between-person effects from the index variable. Next, we created a weighted pile-up variable per workday (Schilling et al., Citation2022). For that, we added up an employee’s workload from previous days until the current day and weighted the previous workload measures according to their temporal distance that has passed. Hence, the workload that was experienced earlier in the week contributes less to the pileup index than workload experienced later in the week. The pile-up variable was calculated for week 1 and 2 separately to account for the prolonged recovery time over the weekend. Overall, the workload pile-up variable represents the individual workload pile-up from what an employee is used to experience across the two work weeks we observed in our studies. illustrates the calculation of the pile-up variable for a fictitious example of an individual participant.

Table 2. Fictitious example of workload pile-up index across study observation period (2 weeks).

Daily workload was person-mean centred. We ran a series of models to test for within – and across-day effects of workload, modelling random slopes for the effects of workload on fatigue. First, we estimated the effect of workload on fatigue within one day (model 1). Second, we added the workload pile-up variable (model 2) to test for the accumulation effect. Then, we added the interaction term between workload and workload pile-up (model 3) to test for the sensitisation effect. We also ran a series of alternative models (e.g. latent growth curve models). None of these alternatives led to different conclusions regarding accumulation and sensitisation effects. The results of these analyses are available from the authors upon request.

It is recommended to control for cyclical patterns in diary studies to avoid reporting spurious relationships or failing to detect relationships (Beal & Ghandour, Citation2011; Gabriel et al., Citation2019; Liu & West, Citation2016). To control for a variety of weekly cycles, we included study day, sine, and cosine in all our models, modelled as fixed slopes (Liu & West, Citation2016).

Results

shows the means and standard deviations of the study variables across the four studies. We first estimated the amount of within-person variance for the Level 1 variables by calculating ICC1s. Across all four studies, we found considerable within-person variance for workload (ranging from .40 to .66, see ) and fatigue (ranging from .34 to .68, see ) at the day level, thus justifying the use of multilevel modelling (Raudenbush & Bryk, Citation2002). Across the four studies, there was no consistent weekly cycle identified (see ), implying that the weekly cycles in diary studies vary greatly between studies.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and correlations for study variables.

provides the effects of workload on fatigue for the four studies. In all four studies, workload was positively related to fatigue concurrently (S3 and 4) and later in the day (S1 and 2). These results support the initial impact model as stated in Hypothesis 1.

Table 4. Unstandardised regression coefficients and standard errors predicting daily fatigue (samples 1–4).

Considering the effects across days, we found no significant effect in any of the four studies (model 2 in for Samples 1–4). These findings do not support the accumulation hypothesis over the workweek.

Finally, we tested sensitisation effects by adding the interaction term of workload pile-up and current workload. Across the four studies, none of the interaction terms were significant (model 3 in ).

Discussion

With this study, we compared effects of workload within one day and across days to understand how daily work experiences may have lasting effects on employees’ well-being. Our results supported the initial impact model (Frese & Zapf, Citation1988), as we consistently found concurrent positive relationships between workload and fatigue. Conversely, the four samples did not support the assumption that workload has an effect across days, at least not over the time periods we were able to test. In terms of accumulation, we found no evidence that workload experienced on previous days had a direct effect on fatigue. Similarly, we found no support for sensitisation effects, as workload pile-up did not moderate the relationship between workload and fatigue within one day.

These results showcase that employees are able to recover overnight and are resilient to short-term accumulation and sensitisation effects. Accordingly, sleep may play an even more important role in the stressor–strain relation than assumed thus far, as the lagged effect of workload on strain seems to vanish overnight. That being said, it is possible that employees can withstand short-term accumulation and sensitisation effects related to workload, but they may suffer from these effects if other factors are present as well. For example, workload experienced on one day may alter the reaction to subsequent workload if autonomy and social support are low. Although most studies have investigated the effects of single job characteristics on employee well-being, considering the concert of different stressors and resources may be particularly useful for investigating how short-term fluctuations relate to well-being impairments over time.

We also controlled for weekly cycles in all four studies by using sine and cosine functions, an approach that is considered useful for detecting and modelling a variety of different weekly cycles (Gabriel et al., Citation2019; Liu & West, Citation2016). It is notable that across the four studies, we found no consistent weekly pattern for daily measurement of fatigue. This lack of consistency may imply that fatigue over the workweek fluctuates considerably, possibly depending on other factors such as season or characteristics of the sample.

Theoretical and methodological implications

While the lack of support for short-term accumulation and sensitisation effects is good news for employees, speaking to their resilience, the findings also have implications for theorising and study designs aimed at understanding the linkage between daily fluctuations and long-term effects on well-being.

The findings of this study generally support the core assumptions of recovery models and highlight once more the relevance of recovery processes in the stressor–strain relation (Meijman & Mulder, Citation1998; Sonnentag et al., Citation2017). Although some research has examined recovery activities and experiences, our findings may serve as a starting point to inform the less considered question of the temporal dynamics of stressors and recovery (Sonnentag et al., Citation2017), specifically in terms of the duration of the strain effects of workload. Our findings consistently showed that workload has within-day effects. Moving forward, it will be insightful to learn whether and how recovery processes can make a difference in the onset, speed, and duration of these effects. Some researchers have proposed that exposure to repeated stressors such as high workload could also have positive effects on employees, for example, through learning, mastery experiences, and development of self-efficacy (Gump & Matthews, Citation1999; Ilies, Aw, et al., Citation2015; Meurs & Perrewé, Citation2011). Perhaps, employees who have established successful recovery activities and routines may experience such positive learning and habituation effects. Such a habituation effect would be indicated through an interaction term opposite to the sensitisation effect (i.e. the experience of previous workload attenuates the relationship between workload and fatigue within one day), which we did not observe across the four studies.

For this study, we used an observation period of two work weeks, which allowed us to consider pile-up up to four previous days for the within-person effects. However, this timeframe may not have been sufficient to uncover previous experiences of workload carrying forward to the present day. Previous research has reported the effects of stressors on next-day strain (e.g. Zhang et al., Citation2016), whereas others have failed to find such effects (e.g. Demerouti & Cropanzano, Citation2017). These studies typically used previous-day or next-morning assessments to test for lingering effects; however, effects on next morning’s strain are still short-term and are only of limited use to explain the build-up of strain that can eventually lead to well-being impairment. In conclusion, our findings imply that the daily diary designs that many researchers have adopted are optimally suited to investigate research questions focusing on short-term processes within one day. However, to understand how these short-term experiences and mechanisms build up and develop over time, researchers need to adopt more extensive research designs that go beyond the usual one or two work weeks.

We believe that accumulation and sensitisation mechanisms should be further investigated, expanding the knowledge to other stressors and well-being. The lack of empirical support for these mechanisms also necessitates the refinement and alternative explanations of how intra – and inter-individual processes may be linked. Greater clarity on these linkages would be important for understanding positive human development and would enable researchers to investigate predictors of fluctuations relevant to such positive development (versus short-term fluctuations that do not hold any meaning or relevance for long-term well-being). One potential avenue for refinement may relate to the interplay between previous experiences and the anticipation of upcoming experiences. Some researchers have argued that current strain experiences are affected not only by past experiences, but also by the anticipation of future stressors (Kecklund & Akerstedt, Citation2004; Rook & Zijlstra, Citation2006; van Eck et al., Citation1998). For example, Hülsheger et al. (Citation2014) investigated mean-level changes in recovery-related variables over the work week, showing improvements in detachment and sleep over the course of the week. These results indicated that employees may worry about job stressors at the beginning of the week but become more relaxed as the week goes on. Neubauer et al. (Citation2018) proposed a more nuanced pattern by considering the interplay of stressor presence, anticipation, and emotional reactions. In their study, stressor experience and anticipation of a stressor had a negative effect on emotions; however, the anticipation effect was stronger if participants had experienced a previous stressor. Similarly, Casper and Sonnentag (Citation2020) showed that anticipation of workload during time outside of work was related to next-morning vigour and exhaustion over and above experienced workload. These findings imply that the stressor–strain relationship may be more complex, influenced by both past and future-oriented cognition and processes.

Limitations and future research directions

This study used four samples using daily diary methodology to offer a systematic investigation of the relation between workload and fatigue within and across days. All four studies exceeded the currently recommended number of observations needed to be able to detect effects (Gabriel et al., Citation2019). However, the study also has some shortcomings.

The four datasets were limited to the stressor–strain relation between workload and fatigue. We chose workload as an indicator of a typical stressor many employees are exposed to, but other stressors may be more likely to trigger accumulation and sensitisation processes over these short periods of time. The few previous studies investigating accumulation effects across days reported the effects of social stressors on fatigue and recovery-related indicators the next day (Nicholson & Griffin, Citation2015; Park & Kim, Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2016). Although social stressors tend to occur less often, they have strong effects on employees’ well-being (Bowling & Beehr, Citation2006). Furthermore, social stressors are particularly likely to trigger ruminative thoughts that hinder the recovery process and can have lingering effects on mood across days (Wang et al., Citation2013). It is possible that stressors that elicit more intense strain reactions could lead to accumulation and sensitisation effects. We therefore encourage future research to investigate whether these short-term developments depend on the type and intensity of the stressor.

Related, we focused our investigation of the effects of workload pile-up, however, future research may also focus on strain reactions. Theoretically, accumulation and sensitisation effects may occur when components of the stress process start to overlap. Hence, the accumulation of strain (e.g. fatigue) might amplify future reactions to stressor exposure (i.e. sensitise). In addition, systematic research is needed to investigate the potential moderating effects of chronic stressors. In additional analyses (available upon request), we did not find a sensitisation effect of chronic workload (measured in the baseline survey), but previous research has found support for this assumption. For example, in a diary study, employees with high chronic organisational constraints – but not workload – reacted more strongly to daily fluctuations in incivility than employees with low chronic constraints (Zhou et al., Citation2015).

All four studies ran for ten working days only, and it is possible that the accumulation and sensitisation effects of workload require more time. We therefore recommend that researchers design studies to cover an extended time span (e.g. two months), which would allow them to test for these effects over longer time periods. More recently, scholars have started to collect daily data over a three-week period (e.g. Lennard et al., Citation2019). However, due to the high burden for participants, we believe that daily measures over an even longer time period are not always feasible. Therefore, to examine longer time periods, scholars could opt for repeated weekly (instead of daily) measures of stressors and strain (e.g. Totterdell et al., Citation2006). In addition, so-called measurement burst designs could be promising for future studies on the accumulation and sensitisation effects of work stress. These study designs have been employed in the area of developmental psychology, but to the best of our knowledge, have yet to be implemented in applied research (Nesselroade, Citation1991; Sliwinski, Citation2008; Stawski et al., Citation2016). A measurement burst study consists of repeated bursts of intensive assessments over a longer time period (e.g. two-week period of daily assessments three times, separated by a time lag of six months), which enables researchers to study both short-term fluctuations and long-term changes. More specifically, such a study design would allow researchers to examine both work stress-related changes in well-being (accumulation effects) and changes in reactivity to daily stressors (sensitisation) across bursts.

Conclusion

Using four diary studies, we tested the theoretical assumptions of immediate impact, accumulation, and sensitisation effects to investigate the temporal dynamics of workload and fatigue. This study is the first to rigorously test if and how stressors reach across days. We found support for the initial impact model, but not for the accumulation and sensitisation processes. Therefore, our results imply that employees manage to recover from demanding work overnight. The study calls for a methodological extension of daily diary designs to allow researchers to test longer time frames for potential accumulation and sensitisation effects.

Acknowledgement

We thank Daniel R. Ilgen and Antje Schmitt for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almeida, D. M. (2005). Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(2), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x

- Baethge, A., Deci, N., Dettmers, J., & Rigotti, T. (2019). “Some days won’t end ever”: Working faster and longer as a boundary condition for challenge versus hindrance effects of time pressure. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(3), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000121

- Baethge, A., & Rigotti, T. (2013). Interruptions to workflow: Their relationship with irritation and satisfaction with performance, and the mediating roles of time pressure and mental demands. Work & Stress, 27(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2013.761783

- Baethge, A., Vahle-Hinz, T., Schulte-Braucks, J., & van Dick, R. (2018). A matter of time? Challenging and hindering effects of time pressure on work engagement. Work & Stress, 32(3), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1415998

- Beal, D. J., & Ghandour, L. (2011). Stability, change, and the stability of change in daily workplace affect. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(4), 526–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.713

- Bowling, N. A., Alarcon, G. M., Bragg, C. B., & Hartman, M. J. (2015). A meta-analytic examination of the potential correlates and consequences of workload. Work & Stress, 29(2), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1033037

- Bowling, N. A., & Beehr, T. A. (2006). Workplace harassment from the victim's perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 998. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.998

- Casper, A., & Sonnentag, S. (2020). Feeling exhausted or vigorous in anticipation of high workload? The role of worry and planning during the evening. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(1), 215–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12290

- Cranford, J. A., Shrout, P. E., Iida, M., Rafaeli, E., Yip, T., & Bolger, N. (2006). A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: Can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(7), 917–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206287721

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The Job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Demerouti, E., & Cropanzano, R. (2017). The buffering role of sportsmanship on the effects of daily negative events. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(2), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1257610

- Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2014). Improving the image of student-recruited samples: A commentary. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12048

- Dormann, C., & van de Ven, B. (2014). Timing in methods for studying psychosocial factors at work. In M. F. Dollard, A. Shimazu, R. B. Nordin, P. Brough, & M. R. Tuckey (Eds.), Psychosocial factors at work in the Asia pacific (pp. 89–116). Springer.

- Frese, M., & Zapf, D. (1988). Methodological issues in the study of work stress: Objective vs subjective measurements of work stress and the question of longitudinal studies. In C. L. Cooper, & R. Payne (Eds.), Causes, coping, and consequences of stress at work (pp. 375–411). John Wiley & Sons.

- Frone, M. R., & Tidwell, M. (2015). The meaning and measurement of work fatigue: Development and evaluation of the three-dimensional work fatigue inventory (3D-WFI). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038700

- Gabriel, A. S., Podsakoff, N. P., Beal, D. J., Scott, B. A., Sonnentag, S., Trougakos, J. P., & Butts, M. M. (2019). Experience sampling methods: A discussion of critical trends and considerations for scholarly advancement. Organizational Research Methods, 22(4), 969–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118802626

- Garst, H., Frese, M., & Molenaar, P. C. M. (2000). The temporal factor of change in stressor-strain relationships: A growth curve model on a longitudinal study in East Germany. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 417–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.417

- Geldhof, G. J., Preacher, K. J., & Zyphur, M. J. (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032138

- Gump, B. B., & Matthews, K. A. (1999). Do background stressors influence reactivity to and recovery from acute stressors? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(3), 469–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb01397.x

- Harkness, K. L., Hayden, E. P., & Lopez-Duran, N. L. (2015). Stress sensitivity and stress sensitization in psychopathology: An introduction to the special section. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000041

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

- Hülsheger, U. R. (2016). From Dawn till dusk: Shedding light on the recovery process by investigating daily change patterns in fatigue. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(6), 905–914. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000104

- Hülsheger, U. R., Lang, J. W., Depenbrock, F., Fehrmann, C., Zijlstra, F. R., & Alberts, H. J. (2014). The power of presence: The role of mindfulness at work for daily levels and change trajectories of psychological detachment and sleep quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1113–1128. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037702

- Igic, I., Keller, A. C., Semmer, N. K., Kälin, W., Elfering, A., & Tschan, F. (2017). Ten-year trajectories of stressors and resources at work: Cumulative and chronic effects on health and well-being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(9), 1317–1343. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000225

- Ilies, R., Aw, S. S. Y., & Pluut, H. (2015). Intraindividual models of employee well-being: What have we learned and where do we go from here? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 827–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1071422

- Ilies, R., Dimotakis, N., & de Pater, I. E. (2010). Psychological and physiological reactions to high workloads: Implications for well-being. Personnel Psychology, 63(2), 407–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01175.x

- Ilies, R., Huth, M., Ryan, A. M., & Dimotakis, N. (2015). Explaining the links between workload, distress, and work–family conflict among school employees: Physical, cognitive, and emotional fatigue. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(4), 1136–1149. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000029

- Kecklund, G., & Akerstedt, T. (2004). Apprehension of the subsequent working day is associated with a low amount of slow wave sleep. Biological Psychology, 66(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.004

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Lennard, A. C., Scott, B. A., & Johnson, R. E. (2019). Turning frowns (and smiles) upside down: A multilevel examination of surface acting positive and negative emotions on well-being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(9), 1164–1180. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000400

- Liu, Y., & West, S. G. (2016). Weekly cycles in daily report data: An overlooked issue. Journal of Personality, 84(5), 560–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12182

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(3), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199801153380307

- McGrath, J. E., & Beehr, T. A. (1990). Time and the stress process: Some temporal issues in the conceptualization and measurement of stress. Stress Medicine, 6(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2460060205

- Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. D. Drenth, H. Thierry, & C. J. de Wolff (Eds.), Work psychology (pp. 5–33). Psychology Press.

- Meurs, J. A., & Perrewé, P. L. (2011). Cognitive activation theory of stress: An integrative theoretical approach to work stress. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1043–1068. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310387303

- Monroe, S. M., & Harkness, K. L. (2005). Life stress, the “kindling” hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: Considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychological Review, 112(2), 417–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.417

- Mroczek, D. K., & Almeida, D. M. (2004). The effect of daily stress, personality, and age on daily negative affect. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 355–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00265.x

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Nesselroade, J. R. (1991). The warp and the woof of the developmental fabric. In R. Downs, L. Liben, & D. Palermo (Eds.), Visions of aesthetics, the environment, and development: The legacy of Joachim F. Wohlwill (pp. 213–240). Erlbaum.

- Neubauer, A. B., Smyth, J. M., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2018). When you see it coming: Stressor anticipation modulates stress effects on negative affect. Emotion, 18(3), 342–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000381

- Nicholson, T., & Griffin, B. (2015). Here today but not gone tomorrow: Incivility affects after-work and next-day recovery. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(2), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038376

- Park, Y., & Kim, S. (2019). Customer mistreatment harms nightly sleep and next-morning recovery: Job control and recovery self-efficacy as cross-level moderators. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(2), 256–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000128

- Pindek, S., Arvan, M. L., & Spector, P. E. (2019). The stressor–strain relationship in diary studies: A meta-analysis of the within and between levels. Work & Stress, 33(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1445672

- Podsakoff, N., Spoelma, T., Chawla, N., & Gabriel, A. (2019). What predicts within-person variance in applied psychology constructs? An empirical examination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(6), 727–754. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000374

- Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Application and data anlysis methods (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Rook, J. W., & Zijlstra, F. R. H. (2006). The contribution of various types of activities to recovery. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(2), 218–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500513962

- Schilling, O. K., & Diehl, M. (2014). Reactivity to stressor pile-up in adulthood: Effects on daily negative and positive affect. Psychology and Aging, 29(1), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035500

- Schilling, O. K., Gerstorf, D., Lücke, A. J., Katzorreck, M., Wahl, H.-W., Diehl, M., & Kunzmann, U. (2022). Emotional reactivity to daily stressors: Does stressor pile-up within a day matter for young-old and very old adults? Psychology and Aging, 37(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000667

- Semmer, N. K., Zapf, D., & Dunckel, H. (1995). Assessing stress at work: A framework and an instrument. In O. Svane, & C. Johansen (Eds.), Work and health - scientific basis of progress in the working environment (pp. 105–113). Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Sliwinski, M. J. (2008). Measurement-Burst designs for social health research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00043.x

- Smit, B. W., & Barber, L. K. (2016). Psychologically detaching despite high workloads: The role of attentional processes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(4), 432–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000019

- Sonnentag, S. (2012). Psychological detachment from work during leisure time. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(2), 114–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411434979

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S72–S103. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1924

- Sonnentag, S., Venz, L., & Casper, A. (2017). Advances in recovery research: What have we learned? What should be done next? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000079

- Sonnentag, S., & Zijlstra, F. R. H. (2006). Job characteristics and off-job activities as predictors of need for recovery, well-being, and fatigue. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 330–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.330

- Stawski, R. S., MacDonald, S. W., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2016). Measurement burst design. The Encyclopedia of Adulthood and Aging, 2, 854–859.

- Teuchmann, K., Totterdell, P., & Parker, S. K. (1999). Rushed, unhappy, and drained: An experience sampling study of relations between time pressure, perceived control, mood, and emotional exhaustion in a group of accountants. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.4.1.37

- Totterdell, P., Wood, S., & Wall, T. (2006). An intra-individual test of the demands-control model: A weekly diary study of psychological strain in portfolio workers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X52616

- van Eck, M., Nicolson, N. A., & Berkhof, J. (1998). Effects of stressful daily events on mood states: Relationship to global perceived stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(6), 1572–1585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1572

- van Hooff, M. L., Geurts, S. A., Kompier, M. A., & Taris, T. W. (2007). “How fatigued do you currently feel?” convergent and discriminant validity of a single-item fatigue measure. Journal of Occupational Health, 49(3), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.49.224

- Wang, M., Liu, S., Liao, H., Gong, Y., Kammeyer-Mueller, J., & Shi, J. (2013). Can’t get it out of my mind: Employee rumination after customer mistreatment and negative mood in the next morning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 989–1004. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033656

- Wickham, R. E., & Knee, C. R. (2013). Examining temporal processes in diary studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(9), 1184–1198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213490962

- Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (2000). Psychological well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.84

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Lei, H., Yue, Y., & Zhu, J. (2016). Lagged effect of daily surface acting on subsequent day’s fatigue. The Service Industries Journal, 36(15–16), 809–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2016.1272593

- Zhou, Z. E., Yan, Y., Che, X. X., & Meier, L. L. (2015). Effect of workplace incivility on end-of-work negative affect: Examining individual and organizational moderators in a daily diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(1), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038167

- Zohar, D., Tzischinski, O., & Epstein, R. (2003). Effects of energy availability on immediate and delayed emotional reactions to work events. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 1082–1093. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1082