ABSTRACT

In two studies, we investigated the effects of workplace bullying on objective measures of cognitive functioning. In Study 1, 47 university employees, self-identified as current targets of bullying (n = 24) or non-targets (n = 23), completed objectively scored cognitive tasks assessing general attention and three components of working memory (central executive, visuospatial sketchpad, and phonological loop). T-test analyses showed that self-identified targets performed more poorly on the suite of tests compared to non-bullied counterparts, primarily driven by deficits in central executive functioning. Study 2 recruited 70 retail and hospitality workers who completed the cognitive tasks plus measures of preoccupying cognitions and exposure to negative acts. As hypothesised, we found significant indirect effects demonstrating that preoccupying cognitions explained the negative relationship between bullying and the three aspects of working memory. The magnitude of the cognitive deficits observed here, and their potential significance for job performance, highlights the importance of primary bullying prevention within organisations. Secondary and tertiary prevention efforts should also consider cognitive impairments experienced by targets and look for opportunities to reduce preoccupying cognitions, which compete for limited cognitive resources, to mitigate the erosive effects of bullying.

Workplace bullying is a serious threat to employee health, well-being, and functioning. Evidence from meta-analyses and systematic reviews indicates that bullying is positively associated with mental health problems, post-traumatic stress symptoms, generalised strain, psychosomatic symptoms, burnout, physical health problems, and sleep problems (Boudrias et al., Citation2021; Nielsen et al., Citation2020; Nielsen & Einarsen, Citation2012). Further, there are prospective associations from bullying to sleep problems and poorer psychological health, as well as the reverse from poor psychological health to bullying (Nielsen et al., Citation2020; Nielsen & Einarsen, Citation2012). There is also robust evidence to suggest that bullying has a negative impact on organisational functioning. Bullying exposure is significantly associated with absenteeism and intention to leave, as well as lower job satisfaction and organisational commitment (Boudrias et al., Citation2021; Nielsen & Einarsen, Citation2012). Prospective studies also suggest that bullying is related to increased absenteeism, especially long-term sickness absence, and turnover (Boudrias et al., Citation2021; Nielsen & Einarsen, Citation2012).

Much of the extant research on workplace bullying has been directed toward documenting the negative outcomes. According to Neall and Tuckey’s (Citation2014) systematic review, 45% of studies investigated outcomes and a further 20% investigated both outcomes and consequences, representing nearly two-thirds of the bullying literature. Within this large body of literature, rarely have studies examined the impact of bullying on cognition. In particular, the nature and extent to which being bullied influences cognitive performance remains unknown, as do the mechanisms underlying these effects. This is an important gap to fill because, as implied by the classical theory of learning and performance (e.g. see Hunter, Citation1986), impairments in cognitive functioning are detrimental to work performance (e.g. McIntyre et al., Citation2015; van Dijk et al., Citation2020) and may explain the effects of bullying exposure in this outcome domain.

Evidence for the erosive effects of bullying provides solid grounds to propose that bullying is likely to undermine performance at work. Being exposed to bullying triggers a process whereby energy is depleted, and resources are progressively lost – both personal resources (such as optimism and self-efficacy) and job resources (such as social support and perceived organisational support) (Naseer & Raja, Citation2021; Tuckey & Neall, Citation2014). But empirical data linking bullying to job performance is scarce. Just three studies that measured performance were included in Nielsen and Einarsen’s (Citation2012) meta-analysis, the results of which revealed a statistically non-significant association (r = −.12, p > .05).

Since then, a nascent body of research has addressed this question, with mixed results. Some studies have observed a significant negative direct effect of workplace bullying on performance (Ashraf & Khan, Citation2014; Devonish, Citation2013) while other studies have not (Gardner & Rasmussen, Citation2018; Olsen et al., Citation2017), though mediator and moderator variables likely play a role (Ashraf & Khan, Citation2014; Devonish, Citation2013; Gardner & Rasmussen, Citation2018; Hewett et al., Citation2018; Majeed & Naseer, Citation2021). These studies indicate the potential complexity of the relationship between bullying and job performance. A growing body of evidence in the healthcare context links bullying experienced by nursing staff with adverse patient safety outcomes (Hogh et al., Citation2021). Many of those studies, however, rely on staff perceptions that bullying undermines their performance or reflect the effects of physical violence or threat of violence rather than bullying (see Houck & Colbert, Citation2017).

Though evidence for negative effects on the health of workplace bullying targets is clear, results regarding job performance remain inconclusive. In our research, we approach this issue from a new angle to build a different kind of knowledge relevant to understanding the potential performance deficits associated with bullying at work. Rather than looking at job performance directly, in two studies we examine the relationship between bullying and performance on objective cognitive assessments of working memory and attention. In addition, in our second study we examine a potential mechanism through which bullying exposure may impact working memory and attention by looking at the mediating role of preoccupying cognitions. Together, our studies pursue evidence that workplace bullying can directly undermine cognitive performance capability, with potential implications for performance in the work environment.

Collecting rigorous, objective data on how bullying affects cognitive functioning is important theoretically and practically. Theoretically, demonstrating that bullying is associated with impaired objective cognitive performance would provide foundational information relevant to building up a comprehensive picture to address more complex questions regarding whether or not, how, and when bullying affects job performance in the work environment. Practically, uncovering evidence for objective cognitive performance deficits associated with bullying would send a strong message to organisations about the need for effective bullying prevention and response strategies, and add weight to positioning this form of mistreatment as a serious concern for senior leaders and board directors responsible for the financial and operational objectives of organisations. The structure and content of intervention, treatment, and return-to-work plans could also be optimised to account for the relationship between bullying on cognition.

Background

The nature of workplace bullying

As explained by Einarsen et al. (Citation2003, p. 15)

Bullying at work means harassing, offending, socially excluding someone or negatively affecting someone’s work tasks. In order for the label bullying (or mobbing) to be applied to a particular activity, interaction or process, it has to occur repeatedly and regularly over a period of time (e.g. about six months). Bullying is an escalating process during which the person confronted ends up in an inferior position and becomes the target of systematic negative social acts. A conflict cannot be called bullying if the incident is an isolated event or if two parties of approximately equal ‘strength’ are in conflict.

Workplace bullying and cognition

Effective cognitive functioning, in particular working memory and attention, is crucial for maintaining adequate work performance (Motowidlo et al., Citation1986). While only a handful of studies to date have documented evidence of cognitive deficits following bullying, such impairments might be widespread amongst bullying targets. In two interview studies, O’Moore and colleagues (Citation1998) found that all 30 Irish participants reported impaired concentration (together with various symptoms of poor psychological health), which they perceived to be directly related to their bullying experience. Likewise, Björkqvist et al. (Citation1994) reported that all 19 Finnish university employees they interviewed had experienced poor concentration following bullying at work, amongst diverse psychological symptoms. Findings also suggest that signs of cognitive impairment may distinguish bullying targets from non-bullied employees. In one of the earliest studies in the field based on a Swedish national cross-sectional study, cognitive impairments including problems with memory and concentration accounted for the greatest differences between bullied and non-bullied employees, together with psychosomatic symptoms (Leymann, 1992, as cited by Hoel et al., Citation2004). Similarly, Agervold and Mikkelsen (Citation2004) found that bullied participants from a sample of Danish blue-collar workers reported significantly higher levels of mental preoccupation and mental fatigue (along with a range of other symptoms) compared with non-bullied participants. There is also evidence that cognitive mechanisms could play a role in fostering other negative outcomes of bullying. Specifically, Nielsen et al.’s (Citation2020) meta-analysis included three studies that reported a significant indirect effect whereby rumination or worry mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and sleep quality. Further, in the healthcare literature, it is possible that altered thinking or concentration could be one of several processes through which bullying undermines patient safety and quality of care (Hogh et al., Citation2021).

In sum, although the issue has not attracted much direct attention, there is a small body of evidence suggesting that bullying targets suffer from self-reported cognitive impairments, such as poor concentration, impaired memory function, mental fatigue, and mental preoccupation. These results (based on self-reports via interviews and survey rating scales) point to, but fall short of, robustly demonstrating the cognitive deficits experienced by targets of workplace bullying. Consequently, in our studies we form hypotheses about the impact of bullying on working memory and attention and use objective measures to investigate the nature of the adverse effects of workplace bullying on these aspects of cognitive performance.

Hypothesis development

The effects of workplace bullying on working memory and attention

According to Baddeley’s theory, working memory is a limited capacity, multi-component system that temporarily stores information, acting as an interface between perception, long-term memory, and action (Baddeley, Citation1996, Citation2003). Baddeley’s framework divides working memory into three components: (1) the visuospatial sketchpad, which holds visual and spatial information; (2) the phonological loop, which is involved in the storage and rehearsal of verbal and auditory information; and (3) the central executive, which switches attention between the two subsidiary components of working memory, focuses attention on specific aspects of a task, retrieves information from long term memory, and is responsible for coordinating multiple simultaneous tasks. For information to enter working memory though, it must first be attended to and perceived. Attention and working memory are thus key cognitive capacities.

Any activity that uses or compromises cognitive capacity is likely to reduce the resources available to perform secondary and concurrent cognitive activities, resulting in impaired cognitive performance. According to the results of three studies conducted by Klein and Boals (Citation2001), cognitive representations of stressful events are a form of unwanted thoughts that compete for cognitive resources, thereby impairing attention and working memory performance. Consistent with this idea, empirical studies have shown that the ability to simultaneously store and manipulate information is compromised by exposure to stressors. For instance, laboratory studies showed that bureaucratic harassment and pay discrimination (related to payment for participating in the experiment) resulted in poorer performance, respectively, on a proofreading task and the Stroop test (Glass & Singer, Citation1972; cited by Cohen, Citation1980). Moreover, highly stressed teachers report greater concentration problems with reading the newspaper when compared to non-stressed teachers (van der Linden et al., Citation2005), and driving instructors facing high workloads perform more poorly on objective measures of memory relative to those with lower workloads (Meijman et al., Citation1992; Parkes, Citation1995). These studies suggest that work-related stressors contribute to impaired attentional and memory capacity, even for simple cognitive activities, as a result of competition for limited cognitive resources.

Workplace bullying is a chronic and extreme source of social stress at work (Zapf, Citation1999). Applying the conclusions drawn by Klein and Boals (Citation2001) to the potential impact of bullying at work, the effort required to adapt to ongoing bullying exposure is likely to leave workers less able to cope with other (cognitive) demands. Specifically, being exposed to workplace bullying is likely to generate complex cognitive representations of multiple bullying episodes over time, occupying attentional resources and undermining the capacity of targets to process information in working memory. We thus expect that bullied workers will perform more poorly on objective cognitive tasks assessing working memory and attention as compared with non-bullied employees.

Hypothesis 1. Workers who have been exposed to workplace bullying will score significantly lower on objective cognitive tests of attention (1a) and working memory (1b) than workers who have not been exposed to bullying.

The mediating role of preoccupying cognitions

The cognitive performance deficits reported by bullied workers may be explained by the presence of unwanted thoughts that compete for limited cognitive resources, compromising working memory and attention (see Klein & Boals, Citation2001). Consistent with this idea, empirical findings indicate that participants who report preoccupying cognitions – persistent worrying or troublesome thoughts about a stressor – also tend to perform more poorly on tests of working memory (e.g. Kemps & Tiggemann, Citation2005; Sliwinski et al., Citation2006; Vondras et al., Citation2005; Vreugdenburg et al., Citation2003).

When exposed to stressors, the appraisal of those stressors is important in understanding their health effects, not only the exposure to the stressors themselves (e.g. Lazarus, Citation1966; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Workplace bullying is a type of threat stressor, associated with perceptions of harm or loss (Tuckey et al., Citation2015). In particular, bullying in the work context represents a threat to self-worth, undermining the belief that the target is a capable and valuable member of the workgroup (Semmer et al., Citation2007), and thwarts the basic psychological needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence (Trépanier et al., Citation2015). Bullying targets are thus likely to become increasingly preoccupied with their experience of bullying as they struggle to process the threat, especially as they become increasingly depleted from their efforts to adapt and the loss of valuable job and personal resources (Tuckey & Neall, Citation2014).

A handful of studies in the bullying literature have examined concepts akin to preoccupying cognitions. Leymann and Gustafsson (Citation1996) found that 81% of 59 bullying targets experienced intrusive thoughts on a weekly to daily basis. In related fields, Aasa et al. (Citation2005) showed that ambulance officers reported worrying about exposure to work-related harassment and intimidation, which predicted their incidence of health complaints such as sleeping problems, headaches, and stomach aches; and Liang et al. (Citation2018) found that intrusive thoughts about abusive supervisory behaviour mediated the lagged association between subordinates’ experiences of abusive supervision and physical health problems. Furthermore, amongst 6,175 Belgium workers recruited from a variety of industries, Notelaers et al. (Citation2006) demonstrated that as exposure to negative acts increased, so did the frequency of work-related worry. Finally, several studies have demonstrated that rumination and worry contribute to sleep problems arising from bullying exposure (Nielsen et al., Citation2020). Overall then, we expect that workplace bullying exposure will be positively associated with mental preoccupation about the bullying being experienced – that is, positively associated with preoccupying cognitions.

Hypothesis 2. There will be a positive relationship between exposure to workplace bullying and preoccupying cognitions.

We anticipate that preoccupying cognitions about bullying will impair attention and memory performance in the manner predicted by the theory of resource competition. For example, evidence shows that preoccupying cognitions concerning food, weight, and body shape play a role in the working memory deficits associated with anorexia nervosa (Kemps et al., Citation2006) and dieting (Kemps & Tiggemann, Citation2005). Similarly, in a sample of participating adults, those who reported high levels of another type of intrusive cognition (global stress thoughts) tended to perform poorly on tests of episodic memory (Vondras et al., Citation2005). Further, in a closely aligned area, results from a longitudinal study in the customer service domain showed that cognitive rumination mediates the negative effect of customer mistreatment on supervisor-rated job performance and the positive effect on self-reported customer sabotage (Baranik et al., Citation2017). Similarly, self-reported anger rumination mediated the effects of weekly bullying exposure on social undermining of one’s partner, as reported by the partner (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., Citation2022). The resource competition framework suggests that preoccupying cognitions will interfere with attention and memory performance by competing for already limited cognitive resources. The effect on episodic memory observed in Vondras et al.’s study, for instance, might be even more pronounced on working memory and attention given the finite nature of these two cognitive systems.

Hypothesis 3. Preoccupying cognitions will mediate the relationship between exposure to workplace bullying and performance on objective cognitive tests of attention (3a) and working memory (3b).

Study 1

In Study 1 we tested Hypothesis 1. Self-identified targets of workplace bullying and non-targets completed measures of bullying exposure and objective cognitive tests of working memory and attention. As the first test of our propositions, a sample of university staff members was recruited, chosen as a large and relatively accessible pool of employees whose work is primarily cognitively demanding (as opposed to predominantly physically or emotionally demanding).

Method

Participants and procedure

Human research ethics approval was gained prior to commencing the research. University staff were recruited using posters displayed at three university campuses located in Adelaide, Australia, via an online bulletin distributed by the National Tertiary Education Union at each university and through an all-staff email sent to staff at one of the universities. Staff who believed that they were currently being bullied at work, or those who felt they had never been bullied at work, were invited to participate in the study. Interested participants were sent an information sheet and, if they wished to take part, booked into a timeslot for completing the study.

Testing took approximately 50 min and was completed at the university campus. The testing procedure followed one of two versions, counter-balanced across participants. Version A presented the questionnaire followed by the cognitive assessments, and Version B the cognitive assessments followed by the questionnaire. A small reimbursement was given to participants for their involvement in the study. Every participant was provided with referral information for counselling and crisis services and with work-related information and support services.

The final sample consisted of 47 participants (n = 15 male, n = 32 female; n = 24 academic staff, n = 23 professional staff). Their ages ranged from 24 to 67 years (M = 44.21, SD = 11.83). Descriptive statistics for the two groups of participants, self-identified as bullied or non-bullied, are shown in . Of note, exposure to bullying behaviours was significantly higher for self-identified bullied employees than non-bullied employees, F (1, 45) = 39.85, p < .001. The mean age was not significantly different between the two groups, F (1, 45) = 3.20, p = .08.

Table 1. Study 1: Background and demographic information for bullied and non-bullied participants.

Measures

Workplace bullying. Exposure to workplace bullying was assessed in two ways. First, participants were asked to respond by selecting either “yes” or “no” to a single item asking if they had been bullied at work in the last six months, in relation to the definition presented in the Introduction. If participants answered yes, frequency of exposure was measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1“Almost Never” to 5 “Daily” along with the duration of the bullying (measured in years and months), and the job role of the perpetrator (manager/supervisor, colleague, subordinate, or other). This format follows one of the common ways of measuring bullying exposure (see Neall & Tuckey, Citation2014).

In addition, as a way of checking the validity of the self-selected groups (bullied and non-bullied), all participants completed the Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ) (Einarsen & Raknes, Citation1997), recording how frequently during the last six-month period they had been subjected to 22 negative behaviours in the workplace (e.g. “hints or signals from others that you should quit your job” or “repeated offensive remarks about you or your private life”). Responses were indicated on a five-point scale (1 = almost never, 2 = now and then, 3 = monthly, 4 = weekly, 5 = daily). The mean score was calculated across the 22 items. The NAQ scores for each group (bullied and not bullied) are shown in . In addition, 10.6% of the sample had a NAQ mean score greater than 2.5, which exceeds the threshold proposed by Notelaers and van der Heijden (Citation2021) for systematic repeated negative exposure.

Attention. The Letter Cancellation Task (Talland, Citation1965) was used to measure general attention. Participants were asked to search an A4-sized matrix of random capital letters sequentially from left to right and top to bottom, marking the letters “F” and “L” as quickly and as accurately as possible. Participants were given three minutes to complete the task. Scores were calculated as the number of correct responses minus the number of letters missed, up to the last letter marked.

Working memory. Working memory was assessed using the Double Span Memory Task (Kemps & Tiggemann, Citation2005), a computerised test that assesses the three components of working memory (central executive, phonological loop, and visuospatial sketchpad). In this task, simple line drawings of everyday objects were randomly presented on a blank 4 × 4 grid on a computer screen. Following the presentation of the images, participants were cued by the computer to verbally name the objects (object recall, assessing the phonological loop); to locate the objects on the 4 × 4 grid using the computer mouse (location recall; assessing the visuospatial sketchpad); or to simultaneously locate and name the objects (combined recall; assessing the central executive). Participants completed six trials at sequence lengths ranging from two to six pictures (two trials of each recall type for each sequence length), equating to a total of 30 trials. Verbal responses were recorded by a member of the research team, and location responses were recorded by the computer. Performance was scored by calculating the number of correct trials (out of 10) for each recall type.

Analyses

To test Hypothesis 1, that self-identified targets of bullying would perform more poorly on objective cognitive tests of attention and working memory than non-targets, a series of t-test analyses were conducted with bullying status as the independent variable (coded as 0 for “not bullied” and 1 for “bullied”), and the four cognitive performance outcomes of interest as the dependent variables. For multiple comparisons in the analysis of the four outcomes, p values were adjusted using FDR correction to reduce the risk of Type I error by adopting the two-stage step-up procedure (Benjamini et al., Citation2006).

Results and discussion

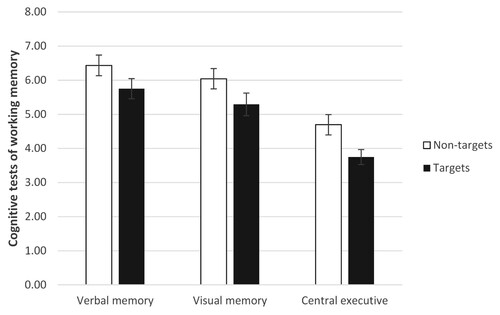

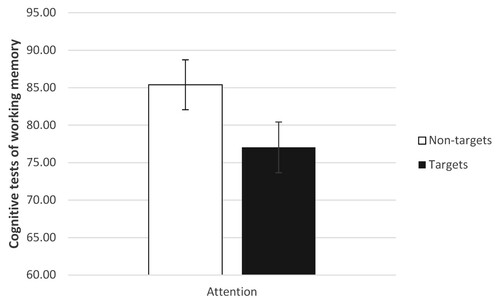

shows the descriptive and t-test statistics comparing scores on the four objective measures of cognitive performance for the bullied and non-bullied employees who participated in the study. A bar graph of these findings is presented in and for the tests of working memory and attention, respectively. Four t-tests, one for each cognitive outcome, revealed that there was a significant effect of bullying status on functioning of the central executive, t (45) = 8.86, FDR adjusted p = .02, with a large effect size (Cohen's d = .87), but not on the sub-systems of working memory. This result suggests that bullied workers have poorer capacity for directing, prioritising, and coordinating working memory compared to non-bullied workers, providing partial support for Hypothesis 1b. The effect of bullying status on attention did not reach statistical significance, t(45) = 1.76, FDR adjusted p = .09, despite having a medium effect size (Cohen's d = .51), meaning that Hypothesis 1a was not supported. Of note, the means and standard deviations shown in for the nonsignificant effects reflect meaningful differences of around half a standard deviation in the expected direction (i.e. medium effect sizes; Cohen, Citation1992), implying that our sample size was underpowered to detect statistically significant effects (see also D’Amico et al., Citation2001). Consistent with this conclusion, post hoc power analysis using G*Power indicated that our analysis was powered only for relatively high effect sizes (i.e. 85.4% of power to detect a large effect of Cohen's d = .80).

Figure 1. Study 1: Scores on the objective cognitive tests of working memory for bulled and non-bullied participants. Notes: The X-axis shows levels of verbal memory, visual memory, and central executive functioning. Error bars represent standard errors.

Figure 2. Study 1: Scores on the objective cognitive test of attention for bulled and non-bullied participants. Notes: The X-axis shows levels of attention. Error bars represent standard errors.

Table 2. Study 1: T-test results exploring the relationship between bullying status and the four measures of objective cognitive performance.

In sum, in Study 1 we found world-first concrete evidence for objective cognitive impairments associated with workplace bullying exposure. We specifically observed a statistically significant deficit in functioning of the central executive, which is responsible for controlled processing in working memory, for university employees who self-identified as having been bullied relative to those who did not consider themselves to be a target of bullying. Though not statistically significant, a meaningful (medium) effect size was also observed between these groups on the visual and verbal aspects of working memory and in terms of general attention, suggestive of more global deficits in cognitive functioning associated with bullying. A key conclusion from Study 1 is that workplace bullying is associated with consequential impairments in foundational cognitive functions. Given the low sample size and corresponding low power, however, it is not appropriate to draw conclusions about the precise nature of those cognitive performance deficits based on this study.

Study 2

Study 1 established initial evidence for objective cognitive deficits associated with workplace bullying exposure. In Study 2 the mediating role of preoccupying cognitions was examined as a possible cognitive mechanism through which workplace bullying may impact cognitive performance, as proposed in Hypotheses 2 and 3. We recruited a sample of hospitality and retail workers who tend to face a high risk of exposure to a variety of negative workplace behaviours, including bullying, due to the nature of their occupations (Blosi & Hoel, Citation2007; Einarsen & Skogstad, Citation1996; Mathisen et al., Citation2008; Niedhammer et al., Citation2007) and whose work differs meaningfully from the sample in Study 1. In addition, in recognition that exposure to bullying can vary across and within employees, we utilised a continuous measure of bullying (in contrast to the between-groups approach in Study 1). This kind of measure is useful for shedding light on whether bullying exposure is significantly associated with cognitive impairment in a sample not specifically recruited in relation to their history of bullying exposure or self-identification as targets.

Method

Participants and procedure

Human research ethics approval was obtained before commencing the study. Hospitality and retail workers who had worked in their respective industries for a minimum of six months were recruited using posters displayed at university campuses located in Adelaide, Australia, and via an email distributed amongst the researchers’ professional and personal networks. Interested volunteers contacted a member of the research team via email, upon which an information sheet was provided. Eligible participants who had agreed to take part were then posted a questionnaire assessing bullying exposure, preoccupying cognitions, and demographic factors, and asked to complete it at home the night before their testing session. Cognitive testing was conducted at the university campus, lasting approximately 45 min. Informed consent was indicated on a consent form prior to the cognitive testing session. Participants who completed both the questionnaire and cognitive testing were reimbursed with a small honorarium. As in Study 1, participants were provided with referral information for information and support services.

The final sample consisted of 70 hospitality (67.1%) and retail (32.9%) workers (n = 46 female, n = 24 male) employed in hotels, restaurants, and retail outlets across Adelaide, Australia. Their ages ranged from 18 to 62 years (M = 28 years, SD = 9.37). Most were employed casually (61.4%), some on a permanent part-time (17.1%) or full-time (21.4%) basis. The mean years of completed education were 13.59 years (SD = 1.79), indicating that on average most participants in our sample had completed secondary school.

Measures

Workplace Bullying was measured via the NAQ, as described in Study 1. The mean score was calculated, with lower values representing a lower frequency of bullying exposure. Cronbach’s alpha was α = .92, indicating a high level of internal consistency. In addition, 12.9% of the sample had a mean score on the NAQ greater than 2.5, again exceeding the threshold for systematic repeated negative exposure proposed by Notelaers and van der Heijden (Citation2021).

Preoccupying cognitions. A scale was developed to measure preoccupying cognitions associated with bullying at work, without also tapping bullying exposure. In the pursuit of content validity, and following the recommendations of Hinkin (Citation1998), we identified existing preoccupying cognition scales (Kemps et al., Citation2006; Kemps & Tiggemann, Citation2005) and used these to guide the creation of a pool of 34 potential items. To enhance construct validity, we reviewed the list of items and removed those that described preoccupied thinking about particular bullying behaviours from the item pool. Though items relating to specific bullying behaviours were generated to mirror the approach used in the other scales, the potential for overlap with the measurement of bullying was too high. This process enabled us to narrow the pool to five items.

Exploratory factor analysis among the five items was performed in the sample of 70 hospitality and retail workers. Participants responded to 5 items on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1“Never” to 5 “Always” to indicate whether in the previous six months they had thoughts about “problems at work while lying awake at night,” “not answering the telephone/mobile because the call might be work-related,” “not wanting to come to work due to feeling intimidated”, “relationship difficulties at work,” and “not feeling comfortable at work.” Exploratory factor analysis revealed a one-factor structure that explained a total of 57.50% of the variance, establishing support for construct validity.

To establish discriminant validity of the scale measuring preoccupying cognitions from that measuring workplace bullying, we collected data from a separate sample of 200 retail and hospitality workers working in the United Kingdom or Australia, via Prolific. Those participants were asked to rate the five-item preoccupying cognitions scale and complete the Short NAQ (Notelaers et al., Citation2019). Confirmatory factor analysis revealed adequate fit for the two-factor model (χ2 (76) = 220.37, CFI = .93, TLI = .92, SRMR = .05, and RMSEA = .09), in line with suggested cut-offs (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The only exception was the RMSEA value of .09, which was higher than the proposed benchmark of .06, which could be due to the small df and small sample size (Kenny et al., Citation2015). In contrast, the single-factor model showed much poorer model fit indices (Δχ2 (1) = 150.24, CFI = .86, TLI = .83, SRMR = .06, and RMSEA = .14). Overall, these results support the conclusion that the constructs of preoccupying cognitions and workplace bullying are distinct.

Having established evidence for different forms of validity, we used the five-item scale to measure preoccupying cognitions in Study 2. The mean score was calculated across the items, with lower scores representing lower frequencies of preoccupying cognitions. The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was α = .81, indicating a high level of reliability.

Cognitive Performance. The objective measures of attention and working memory were the same as those used in Study 1 and scored in the same way.

Analyses

In Study 1 we observed medium to large effects of bullying on the cognitive performance outcomes, though only one effect was statistically significant. In Study 2, according to the guidance of Sim et al. (Citation2022), a minimum sample size of 60 is required to detect large effects and a sample size of 90 is required to detect medium effects. Our sample size of 70 was in the middle of this range; sufficient to test the hypotheses though underpowered.

The mediation analysis was performed using Mplus 8.7 using the maximum likelihood estimator. The indirect effect was tested using a bootstrapping estimation. We followed Preacher and Hayes’s (Citation2008) bootstrapping procedure to generate 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples. Following Preacher and Kelley (Citation2011), we also computed ĸ2 to ascertain the effect sizes of indirect effects.

Results and discussion

The descriptive statistics and correlations among variables are presented in , which reveals significant negative associations between preoccupying cognitions and the four types of cognitive performance as well as a significant positive association between exposure to bullying behaviours and preoccupying cognitions. presents the standardised coefficient estimates for the mediation model. Bullying exposure was positively related to the frequency of preoccupying cognitions (B = .62, p < .001), confirming Hypothesis 2. Preoccupying cognitions were negatively related to verbal memory (B = −.34, p = .02), visual memory (B = −.31, p = .02), and central executive functioning (B = −.31, p = .02). However, preoccupying cognitions were not significantly related to attention (B = −.20, p = .16).

Table 3. Study 2: Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations of study variables.

Table 4. Study 2: Regression results exploring the relationship between exposure to bullying behaviours and the four measures of objective cognitive performance via preoccupying cognitions.

We further tested the hypothesised indirect effects in the mediation model by using a bootstrapping approach. The indirect effect on verbal memory through preoccupying cognitions of −.22 was also significant, with 95% CIs [−.40, −.03]. The indirect effect of bullying exposure on visual attention through preoccupying cognitions was −.19, significantly different from zero with 95% CIs [−.38, −.03]. We also found a significant indirect effect of −.19 for bullying exposure on performance of the central executive through preoccupying cognitions, with 95% CIs [−.37, −.02]. The indirect effect of bullying exposure on attention through preoccupying cognitions was not significant (B = −.12, bias-corrected CI [−.32, .05]). Together, these indirect effects support Hypothesis 3b not 3a. Using Preacher and Kelley’s (Citation2011) approach, effect sizes (ĸ2) were calculated, which represents the ratio of the observed indirect effect to the maximum possible indirect effect that could have been observed. The ĸ2 estimates ranged from .10 to .17 across the four cognitive performance measures, which can be classified in the medium range of effect size (Preacher & Kelley, Citation2011).

General discussion

Across two studies we demonstrated that being exposed to workplace bullying is associated with important impairments in objective cognitive performance, using different study designs, samples, and ways of measuring bullying. In addition, we found that mental preoccupation is a potential mechanism underlying these effects. Overall, though underpowered, our studies provide the first rigorous evidence that being exposed to workplace bullying is likely to impair cognitive functioning, thereby opening a new lens through which to consider the connection between bullying and job performance and highlighting the value of further inquiry in this area.

Theoretical implications

Our research provides the first direct empirical evidence connecting workplace bullying exposure to objectively measurable impairments in cognitive functioning. Using four different tests of cognitive performance, we found broad spectrum impacts of bullying exposure on working memory (central executive functioning, visuospatial sketchpad, and phonological loop) and attention. In a note of caution, however, though the observed relationships were meaningful in terms of their effect size, our studies were underpowered to detect statistically significant effects. In particular, the only significant direction relationship we observed was the effect of bullying status (target versus non-target) on functioning of the central executive component of working memory.

The cognitive deficits associated with bullying exposure have been hinted at in earlier studies, which have documented self-reported symptoms such as difficulties with memory, concentration, mental fatigue, and preoccupation (e.g. Agervold & Mikkelsen, Citation2004; Björkqvist et al., Citation1994; O’Moore et al., Citation1998). Our research, which directly examined this issue using objective cognitive performance tests, supports the conclusion that the effects of bullying are manifest in foundational aspects of cognition. While our research indicates that bullying may be associated with cognitive deficits in the capacity to work with complex information (recall common objects and their locations – drawing on the central executive), unfamiliar information (recall object locations – drawing on the visuospatial sketchpad), familiar information (recall common object names – drawing on the phonological loop), and attend to stimuli (search and locate letters in a matrix), the low power of our studies highlights the need for more research on this important issue to clarify the precise nature of the cognitive deficits.

Our findings provide important foundational information for building a comprehensive understanding of the complex effects of workplace bullying on job performance. Few studies have considered this relationship, with mixed findings (e.g. Nielsen & Einarsen, Citation2012). By drilling down to the level of core cognitive functions – working memory and attention – our results lay a foundation from which to systematically investigate the bullying—job performance relationship. The effect sizes observed across our studies (i.e. medium to large effects; Cohen, Citation1992) suggest that the magnitude of the cognitive impairments is practically meaningful, highlighting the value of considering cognition as part of the picture regarding how bullying affects performance at work. Further research can draw on our findings and build on the methods used here to examine how these core cognitive deficits manifest in more complex performance tasks and, ultimately, overall performance on the job.

Our data support the role of preoccupying cognitions as a mediating mechanism in the negative relationship between exposure to bullying behaviour and cognitive performance in a naturalistic exposure setting. As observed in Study 2, there is a detrimental impact of bullying on cognitive functioning through preoccupation with intrusive, unwanted thoughts, at naturalistic levels of bullying exposure. Such thoughts are believed to compete for cognitive resources, resulting in the type of deficits observed here. Preoccupying cognitions may also play a role in fostering some of the other detrimental effects of bullying. Evidence from the clinical domain, for instance, shows that preoccupying cognitions are associated with greater levels of depression for sufferers of eating disorders (Lydecker et al., Citation2022), and play a role in the relationship between restrained eating and elevations in cortisol excretion (Putterman & Linden, Citation2006). Experiencing ongoing preoccupying thoughts over time is likely to foster negative affective responses that not only are directly involved in the manifestation of psychological health problems, but also impact physiological arousal and influence physiological stress processes determinantal to health (see Frijda, Citation1986). Preoccupying cognitions might therefore be an important factor in explaining the well-documented effects of bullying on mental and physical health, consistent with nascent research regarding the mediating role of worry and rumination in health outcomes (e.g. Nielsen et al., Citation2020).

Practical implications

Board directors, senior organisational leaders, and managers should be aware that bullying can undermine the financial and operational objectives of an organisation through its myriad negative effects, including impairing the effective cognitive functioning of workers exposed to bullying behaviours. Using reliable and valid objective measures of cognitive performance, our findings underscore the importance of sustainable and effective primary prevention efforts to mitigate bullying before the erosive effects emerge.

Our findings are also relevant for responding to bullying through secondary and tertiary prevention, which are even more salient in view of recent data showing the elevated risk of disability retirement associated with workplace bullying (Nielsen et al., Citation2017). Treatment and recovery approaches for workers suffering from the impacts of bullying should take into account the nature of the cognitive deficits they are likely to be experiencing as a result of their bullying experience, for example by aiding targets to reduce preoccupying cognitions that compete for finite cognitive resources. The potential for significant cognitive impairments may also present a barrier to implementing effective secondary prevention strategies, particularly if targets are experiencing ongoing preoccupying cognitions. Understanding the nature and role of preoccupying cognitions in the process and outcomes of bullying at work may ultimately provide new opportunities for interventions to reduce the harmful effects of bullying and enable workers to continue to function effectively at work.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

A major strength of our research was the use of objective measures of cognitive performance, which go beyond the self-reported nature of the cognitive impacts documented in previous research to provide reliable and valid measures of core aspects of cognitive functioning. Likewise, observing an overarching pattern of converging findings across two studies with different samples and methods lends strength to the conclusion that workplace bullying is associated with impairments in objective cognitive performance. Unfortunately, both studies were underpowered to detect smaller but meaningful effects (i.e. medium effect size). A valuable next step would be to collect measures of job performance alongside objective cognitive assessments in larger samples of workers to clarify the nature of these foundational deficits and identify how they show up in the work context. Moreover, we measured exposure to workplace bullying within a timeframe covering the last six months. Without accurate knowledge of how soon exposure to bullying may start to take effect in influencing cognitive performance and how long such effects last, a longitudinal study would assist in identifying the nature of the impact of bullying on cognition.

In Study 1 we found a statistically significant impairment in central executive functioning when contrasting self-identified bullying targets with non-targets, and nonsignificant medium-sized effects on the other aspects of cognitive performance. This pattern may reflect the complexity of the cognitive demands associated with recalling both object names and their locations relative to doing only one of these tasks. Said another way, complex tasks may be more vulnerable to cognitive performance deficits, as seems to be the case for burnout (Deligkaris et al., Citation2014). In Study 2, which used a continuous measure of exposure to bullying behaviours, we found significant indirect effects linking bullying to all three aspects of working memory performance, mediated by preoccupying cognitions. In terms of direct associations though, only the correlation between NAQ scores and attention was significant. We did not, however, find a significant indirect effect for this cognitive outcome, perhaps due to multicollinearity between bullying and preoccupying cognitions. Overall, the value of Study 2 comes from demonstrating that the impact on performance may arise from off-task cognitions rather than from exposure alone.

When considering the two studies together, recruiting workers who self-identify as bullying targets, whose mean level of exposure to negative acts is greater (as per the mean scores in our studies), may be more likely to reveal insights into the direct effects. The impact of lower levels of bullying exposure may only be apparent through the effects of other cognitive processes, such as intrusive and unwanted thinking. It is also possible that the Study 1 findings point to the potential for self-labeling to play a role in the cognitive impacts of bullying (e.g. Hewett et al., Citation2018).

Future research should consider the role of self-labelling and continue to explore different ways of measuring bullying exposure to build up a picture of the associated cognitive deficits. As already noted, recruiting larger samples will be important, though this is also more difficult when objective cognitive tests are used as part of the suite of measures. Indeed, in our studies we had to balance the trade-off between power and data quality in electing to use objective cognitive assessments. Now that our research has established the potential value of this line of inquiry, insights into effect size and suitability of different methods arising from our studies can be used to guide research design, power, sample size, and measurement decisions in future work. Overall, we hope that our findings pave the way for studies that are resourced to explore cognitive deficits and associated mechanisms in larger and more diverse samples, along with other types of workplace mistreatment. While our research considered bullying from organisational insiders, some of the same erosive processes likely apply following exposure to aggressive treatment from organisational outsiders (such as customers) as well (e.g. Baranik et al., Citation2017).

We also need to consider the possibility that the relationships we observed may operate in the reverse direction as well. That is, rather than bullying only undermining cognitive performance, workers who perform more poorly on tests of cognitive functioning may be more likely to be exposed to bullying behaviours at work or to identify as a target of bullying. Though there is little data on this reverse hypothesis, Kim and Glomb’s (Citation2010) findings suggest the opposite: they observed that greater (rather than poorer) cognitive ability, as measured during the selection process, is positively associated with subsequent levels of victimisation at work – this result lowers the plausibility of the reverse explanation for our findings. It is also possible that third variables may play a role by fostering preoccupying cognitions and increasing exposure to bullying. For instance, evidence strongly suggests that bullying is more likely to occur in stressful work environments (Skogstad et al., Citation2011), and in such environments employees may also be more likely to ruminate about a broader array of work-related stressors (Kompier et al., Citation2012). In terms of personal characteristics, neuroticism has been linked to higher rates of bullying exposure (though findings are not straightforward; Nielsen & Knardahl, Citation2015), and neuroticism may also increase the likelihood that employees are preoccupied with worrying thoughts more generally (Munoz et al., Citation2013). To address these threats to internal validity, in future research it would be useful to gather repeated measurements of the work environment, personality traits, bullying exposure, and cognitive performance, and/or collect measures of bullying and relevant third variables well in advance of those assessing cognitive performance, to provide stronger evidence for the causal direction of the relationships.

Conclusion

Our study presents the first direct empirical evidence for objective cognitive deficits associated with workplace bullying exposure. We observed detrimental effects in fundamental cognitive processes – attending to stimuli, controlling and directing working memory, visual recall, and verbal recall – associated with exposure to bullying at work. Given the significance of cognitive functioning for effective job performance, these findings send a serious message about the importance of bullying prevention for healthy individual and organisational functioning. In addition, our results highlighting preoccupying cognitions as one explanatory mechanism for the cognitive impacts of bullying open new lines of research regarding the process of erosion experienced by bullying targets and have substantive implications for secondary and tertiary prevention efforts to mitigate the effects of this serious occupational hazard. More research is needed to clarify the nature of the cognitive deficits connected to bullying exposure, particularly studies with larger and more diverse samples that mitigate concerns arising from the lack of power in our studies to detect smaller but meaningful effects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data associated with these two studies are stored in a publicly accessible repository hosted by the University of South Australia https://data.unisa.edu.au/dap/.

References

- Aasa, U., Brulin, C., Angquist, K., & Barnekow-Bergkvist, M. (2005). Work-related psychosocial factors, worry about work conditions and health complaints among female and male ambulance personnel. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 19(3), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00333.x

- Agervold, M., & Mikkelsen, E. G. (2004). Relationships between bullying, psychosocial work environment and individual stress reactions. Work & Stress, 18(4), 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370412331319794

- Ashraf, F., & Khan, M. A. (2014). Does emotional intelligence moderate the relationship between workplace bullying and job performance? Asian Business & Management, 13(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1057/abm.2013.5

- Baddeley, A. (1996). Exploring the central executive. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A: Human Experimental Psychology, 49(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/713755608

- Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(10), 829–839. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1201

- Baranik, L. E., Wang, M., Gong, Y., & Shi, J. (2017). Customer mistreatment, employee health, and job performance: Cognitive rumination and social sharing as mediating mechanisms. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1261–1282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314550995

- Benjamini, Y., Krieger, A. M., & Yekutieli, D. (2006). Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika, 93(3), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/93.3.491

- Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Hjelt-Bäck, M. (1994). Aggression among university employees. Aggressive Behavior, 20(3), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1994)20:3<173::AID-AB2480200304>3.0.CO;2-D

- Blosi, W., & Hoel, H. (2007). Abusive work practices and bullying among chefs: A review of the literature. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(4), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2007.09.001

- Boudrias, V., Trépanier, S., & Salin, D. (2021). A systematic review of research on the longitudinal consequences of workplace bullying and the mechanisms involved. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 56(1), 101508–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101508

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Cohen, S. (1980). Aftereffects of stress on human performance and social behavior: A review of research and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 88(1), 82–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.1.82

- D’Amico, E. J., Neilands, T. B., & Zambarano, R. (2001). Power analysis for multivariate and repeated measures designs: A flexible approach using the SPSS MANOVA procedure. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 33(4), 479–484. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195405

- Deligkaris, D., Panagopoulou, E., Montgomery, A. J., & Masoura, E. (2014). Job burnout and cognitive functioning: A systematic review. Work & Stress, 28(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2014.909545

- Devonish, D. (2013). Workplace bullying, employee performance and behaviors: The mediating role of psychological well-being. Employee Relations, 35(6), 630–647. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-01-2013-0004

- Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2003). The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research and practice (pp. 3–40). CRC Press.

- Einarsen, S., & Raknes, B. (1997). Harassment in the workplace and the victimization of men. Violence and Victims, 12(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.12.3.247

- Einarsen, S., & Skogstad, A. (1996). Bullying at work: Epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414854

- Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge University Press.

- Gardner, d. H., & Rasmussen, W. (2018). Workplace bullying and relationships with health and performance among a sample of New Zealand veterinarians. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 66(2), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2017.1395715

- Glass, D. C., & Singer, J. E. (1972). Urban stress: Experiments on noise and social stressors. Academic Press.

- Hewett, R., Liefooghe, A., Visockaite, G., & Roongrerngsuke, S. (2018). Bullying at work: Cognitive appraisal of negative acts, coping, wellbeing, and performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000064

- Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1), 104–121.

- Hoel, H., Faragher, B., & Cooper, C. L. (2004). Bullying is detrimental to health, but all bullying behaviours are not necessarily equally damaging. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 32(3), 367–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880410001723594

- Hogh, A., Clausen, T., Bickmann, L., Hansen, Å-M, Conway, P. M., & Baernholdt, M. (2021). Consequences of workplace bullying for individuals, organizations and society. In P. D’Cruz, E. Noronha, E. Baillien, B. Catley, K. Harlos, A. Høgh, & E. G. Mikkelsen (Eds.), Pathways of job-related negative behaviour: Handbooks of workplace bullying, emotional abuse and harassment volume 2 (pp. 177–200). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0935-9_8

- Houck, N. M., & Colbert, A. M. (2017). Patient safety and workplace bullying: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 32(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000209

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hunter, J. E. (1986). Cognitive ability, cognitive aptitudes, job knowledge, and job performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 29(3), 340–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(86)90013-8

- Kemps, E., & Tiggemann, M. (2005). Working memory performance and preoccupying thoughts in female dieters: Evidence for a selective central executive impairment. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(3), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X35272

- Kemps, E., Tiggemann, M., Wade, T., Ben-Tovim, D., & Breyer, R. (2006). Selective working memory deficits in anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 14(2), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.685

- Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543236

- Kim, E., & Glomb, T. M. (2010). Get smarty pants: Cognitive ability, personality, and victimization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019985

- Klein, K., & Boals, A. (2001). The relationship of life event stress and working memory capacity. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15(5), 565–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.727

- Kompier, M. A., Taris, T. W., & van Veldhoven, M. (2012). Tossing and turning - insomnia in relation to occupational stress, rumination, fatigue, and well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 38(3), 238–246. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41508889

- Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. McGraw-Hill.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Leymann, H., & Gustafsson, A. (1996). Mobbing at work and the development of post-traumatic stress disorders. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414858

- Liang, L. H., Hanig, S., Evans, R., Brown, D. J., & Lian, H. (2018). Why is your boss making you sick? A longitudinal investigation modeling time-lagged relations between abusive supervision and employee physical health. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(9), 1050–1065. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2248

- Lydecker, J. A., Simpson, L., Smith, S. R., White, M. A., & Grilo, C. M. (2022). Preoccupation in bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, anorexia nervosa, and higher weight. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23630

- Majeed, M., & Naseer, S. (2021). Is workplace bullying always perceived harmful? The cognitive appraisal theory of stress perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 59(4), 618–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12244

- Mathisen, G. E., Einarsen, S., & Mykletun, R. (2008). The occurrences and correlates of bullying and harassment in the restaurant sector. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00602.x

- McIntyre, R. S., Soczynska, J. Z., Woldeyohannes, H. O., Alsuwaidan, M. T., Cha, D. S., Carvalho, A. F., Jerrell, J. M., Dale, R. M., Gallaugher, L. A., Muzina, D. J., & Kennedy, S. H. (2015). The impact of cognitive impairment on perceived workforce performance: Results from the International Mood Disorders Collaborative Project. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 56, 279–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.08.051

- Meijman, T., Mulder, G., van Dormolen, M., & Cremer, R. (1992). Workload of driving examiners: A psychophysiological field study. In H. Kragt (Ed.), Enhancing industrial performance: Experiences of integrating the human factor (pp. 245–258). Taylor & Francis.

- Motowidlo, S. J., Manning, M. R., & Packard, J. S. (1986). Occupational stress: Its causes and consequences for job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(4), 618–629. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.4.618

- Munoz, E., Sliwinski, M. J., Smyth, J. M., Almeida, D. M., & King, H. A. (2013). Intrusive thoughts mediate the association between neuroticism and cognitive function. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(8), 898–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.019

- Naseer, S., & Raja, U. (2021). Why does workplace bullying affect victims’ job strain? Perceived organization support and emotional dissonance as resource depletion mechanisms. Current Psychology, 40(9), 4311–4323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00375-x

- Neall, A. M., & Tuckey, M. R. (2014). A methodological review of research on the antecedents and consequences of workplace harassment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(2), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12059

- Niedhammer, I., David, S., Degioanni, S., (2007). Economic activities and occupations at high risk for workplace bullying: Results from a large-scale cross-sectional survey in the general working population in France. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 80(1), 346–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-006-0139-y

- Nielsen, M. B., & Einarsen, S. (2012). Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress, 26(4), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2012.734709

- Nielsen, M. B., Emberland, J. S., & Knardahl, S. (2017). Workplace bullying as a predictor of disability retirement: A prospective registry study of Norwegian employees. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 59(7), 609–614. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001026

- Nielsen, M. B., Harris, A., Pallesen, S., & Einarsen, S. V. (2020). Workplace bullying and sleep – A systematic review and meta-analysis of the research literature. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 51(3), 101289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101289

- Nielsen, M. B., & Knardahl, S. (2015). Is workplace bullying related to the personality traits of victims? A two-year prospective study. Work & Stress, 29(2), 128–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1032383

- Notelaers, G., Einarsen, S., De Witte, H., & Vermunt, J. K. (2006). Measuring exposure to bullying at work: The validity and advantages of the latent class cluster approach. Work & Stress, 20(4), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370601071594

- Notelaers, G., & van der Heijden, B. (2021). Construct validity in workplace bullying and harassment research. In P. D’Cruz, E. Noronha, G. Notelaers, & C. Rayner (Eds.), Concepts, approaches and methods: Handbooks of workplace bullying, emotional abuse and harassment 1 (pp. 369–424). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0134-6_11

- Notelaers, G., Van der Heijden, B., Hoel, H., & Einarsen, S. (2019). Short Negative Acts Questionnaire (SNAQ) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t80313-000

- Olsen, E., Bjaalid, G., & Mikkelsen, A. (2017). Work climate and the mediating role of workplace bullying related to job performance, job satisfaction, and work ability: A study among hospital nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(2), 2709–2719. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13337

- O’Moore, M., Seigne, E., McGuire, L., & Smith, M. (1998). Victims of workplace bullying in Ireland. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 19(2–3), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/03033910.1998.10558195

- Parkes, K. R. (1995). The effects of objective workload on cognitive performance in a field setting: A two-period cross-over trial. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 9(7), S153–S171. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2350090710

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16(2), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022658

- Putterman, E., & Linden, W. (2006). Cognitive dietary restraint and cortisol: Importance of pervasive concerns with appearance. Appetite, 47(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.003

- Rayner, C., & Hoel, H. (1997). A summary review of literature relating to workplace bullying. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 7(3), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1298(199706)7:3<181::AID-CASP416>3.0.CO;2-Y

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., Antino, M., León-Pérez, J. M., & Ruiz-Zorrilla, P. (2022). Workplace bullying, emotional exhaustion, and partner social undermining: A weekly diary study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5–6), NP3650–NP3666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520933031

- Semmer, N. K., Jacobshagen, N., Meier, L. L., & Elfering, A. (2007). Occupational stress research: The “stress-as-offense-to-self” perspective. In J. Houdmont & S. McIntyre (Eds.), Occupational health psychology: European perspectives on research, education and practice (2nd ed., pp. 43–60). ISMAI Publishers.

- Sim, M., Kim, S.-Y., & Suh, Y. (2022). Sample size requirements for simple and complex mediation models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 82(1), 76–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131644211003261

- Skogstad, A., Torsheim, T., Einarsen, S., & Hauge, L. J. (2011). Testing the work environment hypothesis of bullying on a group level of analysis: Psychosocial factors as precursors of observed workplace bullying. Applied Psychology, 60(3), 475–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00444.x

- Sliwinski, M. J., Smyth, J. M., Hofer, S. M., & Stawski, R. S. (2006). Intraindividual coupling of daily stress and cognition. Psychology and Aging, 21(3), 545–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.545

- Talland, G. A. (1965). Deranged memory. Academic Press.

- Trépanier, S.-G., Fernet, C., & Austin, S. (2015). A longitudinal investigation of workplace bullying, basic need satisfaction, and employee functioning. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037726

- Tuckey, M. R., & Neall, A. M. (2014). Workplace bullying erodes job and personal resources: Between- and within-person perspectives. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(4), 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037728

- Tuckey, M. R., Searle, B. J., Boyd, C. M., Winefield, A. H., & Winefield, H. R. (2015). Hindrances are not threats: Advancing the multi-dimensionality of work stress. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(2), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038280

- van der Linden, D., Keijsers, G. P. J., Eling, P., & van Schaijk, R. (2005). Work stress and attentional difficulties: An initial study on burnout and cognitive failures. Work & Stress, 19(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500065275

- van Dijk, D. M., van Rhenen, W., Murre, J. M. J., & Verwijk, E. (2020). Cognitive functioning, sleep quality, and work performance in non-clinical burnout: The role of working memory. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231906. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231906

- Vondras, D. D., Powels, M. R., Olson, A. K., Wheeler, D., & Snudden, A. L. (2005). Differential effects of everyday stress on the episodic memory test performances of young, mid-life, and older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 9(1), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860412331323782

- Vreugdenburg, L., Bryan, J., & Kemps, E. (2003). The effect of self-initiated weight-loss dieting on working memory: The role of preoccupying cognitions. Appetite, 41(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00107-7

- Zapf, D. (1999). Organisational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1/2), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437729910268669

- Zapf, D., Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Vartia, M. (2003). Empirical findings on bullying in the workplace. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace: International perspectives in research and practice (pp. 103–126). Taylor & Francis.

- Zapf, D., Knorz, C., & Kulla, M. (1996). On the relationship between mobbing factors, and job content, social work environment, and health outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414856