ABSTRACT

This study explored the perceptions of 51 graduates of a distance learning health and social care programme, identifying what factors contributed to students continuing for the duration of their distance learning studies and completing their degree. An appreciative inquiry approach was used to identify the positive aspects of the students’ experience. Support from family, tutors and employers as well as flexibility of studying at The Open University UK, enabled graduates to continue their studies. A key aspect of the graduates’ success was the supportive feedback received from tutors, which they reported enabled them to build their knowledge, skills and confidence as they progressed to completion of their degree. Flexibility came in different forms, from being able to access their learning materials at any time around their busy lives, to tutors being very responsive to students’ needs. The findings are discussed in relation to the students’ development of competence and autonomy, factors that contribute to strengthen students’ intrinsic motivation.

Introduction and literature review

The completion of an undergraduate degree through distance learning poses many challenges for students and the rates of student retention and completion have been recognised as a persistent challenge. There has been a drive for some time to increase the retention and progression of students to enable them to complete their degree. Often the approach for such investigations is to identify a problem, such as a low retention rate, and explore the origins of such a phenomenon. However, it is recognised that open and distance learning poses many challenges (Orsmond & Merry, Citation2011; Russo-Gleicher, Citation2014) such as time management, motivation and persistence through the course (Angelino, Williams, & Natvig, Citation2007; Brown, Citation2011; Jenkins, Citation2011). These issues are somewhat compounded when the period of study is extended, such as at The Open University where the average time of completion of a degree is 5.8 years. Studying at a distance can also feel isolating for some students, as there is little face-to-face tuition and contact with their tutor may be limited to online tutorials. The nature of health and social care (HSC) students are such that many are in part-time employment or must balance study with family caring responsibilities. In a recent small-scale study on resilience of first year Open University students, respondents stated that their biggest challenge was carving out time to study alongside other commitments (Simons, Beaumont, & Holland, Citation2018).

Student retention has been widely investigated (Buglear, Citation2009). Most studies have focussed on the retention of students in face-to-face Higher Education institutions. Less is known about online institutions although it is generally agreed that retaining online and distance students presents specific challenges. Some studies explore attrition (loss of students) rather than retention of students: According to Frankola (Citation2001) and Diaz (Citation2002) attrition rates for online courses are up to 20% higher than in traditional, face-to-face classroom environments and Flood (Citation2002) reported attrition rates in online courses as high as 80%. The reason for such high attrition could be due to several factors, such as a high proportion of distance learning students trying to juggle employment with study. Also, the nature of students who choose to study through distance learning is such that they are often older students who have family, social and employment commitments in addition to their studies. In our health and social care programme most students are in the age group 30–49 years.

The aim of this study was to gain insight from successful students on what helped them succeed so that the information could contribute to enhance the quality of our provision and to enable more students to complete their studies and achieve a qualification.

The Open University UK is a large distance learning institution with about 170,000 students, the majority of whom study part-time, at a distance. Student enrolment on a single module within a programme can exceed 3,000. Entry is generally open to anyone, regardless of their prior educational qualifications, although students are given advice and support to recognise whether they are ready to commence study. Nevertheless, some students still embark on modules despite being unprepared and this inevitably affects retention. Consequently, it has always been a major challenge to maintain acceptable retention rates with open entry, but the university highly values openness and is committed to continuing to do so.

Distance education students have characteristics and needs that differ from traditional learners and the virtual learning environment differs in important ways from an on-campus environment (Rovai, Citation2003). These differences pose module tutors with significant retention and completion challenges. Most Open University students are mature distant learners, a group for whom campus and social issues are largely irrelevant, and family, home, and work contexts, not under the control of the university, are a priority (Strahan & Crede, Citation2015). Many of these are content to study without seeking further academic or social integration. Tait (Citation2003) estimates that around 10% of Open University students ‘do not want interaction with other students’ (Tait, Citation2003, p. 4). This is in clear contrast with face-to-face universities where integration is generally considered a prerequisite for good retention and performance (Tinto, Citation1975, Citation1990, Citation1993) and may explain some of the difference in retention rates between these two types of provision.

The success of these open and distance learning students could be deemed a greater achievement as most have more complex challenges and adversities to overcome than the average student receiving face-to-face tuition on a conventional three-year full-time degree programme. Many HSC students have low previous qualifications with 40% having less than third level qualifications on entry to study, the majority are women undertaking low paid (or unpaid) work. 16.3% of the students are from Black Minority Ethnic backgrounds, 10% have a disability and 20.7% are from a low socio-economic group (SEG). This is a demographic group known to face significant challenges that potentially undermine their chances of successfully completing an undergraduate degree. In recognition of the inherent challenges and concomitant success in graduating, this study was designed to use an appreciative inquiry approach, with a view to learning what works in the delivery of the Health and Social Care degree. The research sought to access knowledge on factors that contribute to the success of this group of students and apply it to improve provision and increase the likelihood of success of subsequent students.

Methodology and methods

The study took an Appreciative Inquiry (AI) approach. AI originates in the work of David Cooperrider in the 1980s who, as a doctoral student, was studying what did and did not work in a clinic in Cleveland. He then made a shift in his approach away from focussing on deficiencies to more specifically looking for those factors that contributed to the organisation’s health and excellence (Cooperrider & Srivastva, Citation1987). A key underlying assumption of this approach is that the questions we ask influence the answers we get. Research into the social (innovation) potential of organisational life should begin with appreciation. It should be applicable, provocative and collaborative.

There are four guiding principles:

Every system works to some degree.

Knowledge generated by the inquiry should be applicable to improving the system.

Systems are capable of becoming more than they are, and they can learn how to guide their own improvement.

The process and outcome of the inquiry are interrelated and inseparable so should be considered together.

AI is more about learning and understanding something, and thereby valuing it, than it is about expressions of appreciation (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, Citation2008). The relatively low number of students who continued to study to completion of their degree meant their views were of real value to understanding what worked in the undergraduate programme.

We sought to gain greater understanding of what it was that influenced our graduates to persist in their studies, despite the challenges over what was for some students, six years of part-time study, at a distance.

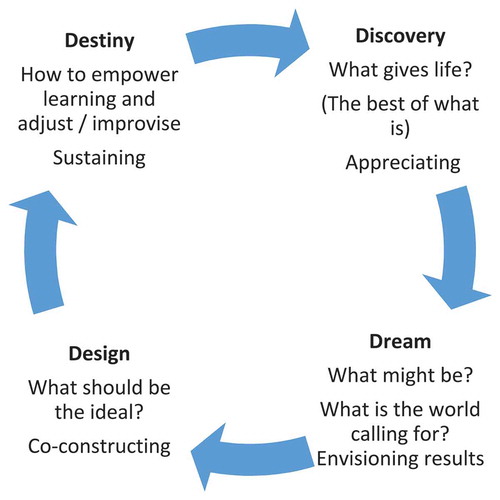

All studies using an AI approach start with a focus of inquiry. In this study the focus was retention and successful completion of a distance learning degree with students identifying positive features from their experience that enabled this. Having agreed a focus, we were able to move forward following the four phases outlined in Cooperrider and Whitney (Citation2005) 4D cycle of Appreciative Inquiry (see ).

Figure 1. The 4D cycle of appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider & Whitney, Citation2005, p. 279) (reproduced with permission)

Firstly, the discovery phase identifies what Cooperrider and Whitney (Citation2005) describe as ‘the best of what is.’ Here the task is accomplished by focussing on peak times or high point experiences of organisational excellence – when people have experienced the organisation at its best and most effective. Part of the process during this phase is to let go of analyses of deficits and systematically seek to isolate and learn from positives, including even the smallest wins. In our study we identified students’ completion of their degree in Health and Social Care as the high point of success for the programme, and therefore designed our study to interview a representative sample of students who had graduated in the past five years to explore the factors that influenced and contributed to their success. It was acknowledged that students would have experienced numerous high points on their journey to completing their degree. However, our selection of this specific high point was driven by the university’s strategy to increase degree completion and qualification rates.

Secondly, the dream phase takes the findings from the study, including the voices and hopes of students, in order to imagine the desired future. Visions of the future emerge out of grounded examples from the organisation’s past strengths. This phase is ongoing, with the findings of the study being disseminated across the faculty and university and used as the basis for further inquiries where appropriate.

Thirdly, the design phase takes the vision of the desired future and helps ask questions about who will be involved and how this will be achieved.

The destiny phase delivers on the new vision of the future and is sustained by nurturing a collective sense of purpose and movement. The destiny phase is ongoing and brings the organisation full circle to the discovery phase.

It is acknowledged that several approaches other than AI could have been taken in this study, however AI was specifically selected and adapted because it takes an affirmative and strengths-based approach. We believe this approach was well suited to investigating and building on what worked for this group of successful students.

Ethical considerations

Full approval was granted by the Open University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) guided by institutional principles, which are consistent with what is currently generally accepted across the spectrum of social sciences. The project was also approved by the Student Research Project Panel (SRPP). Data Protection compliance was assured through liaison with the Open University Data Protection Coordinator, and completion of a Data Protection Questionnaire to assure compliance with the, then, Data Protection Act 1998. Ethical issues that could have arisen were emergence of sensitive issues raised when discussing challenges which the graduates had encountered. Recalling such issues during the interviews could have caused distress. Interviewees were to be asked if they would prefer to stop the interview if this occurred. One graduate discussed sensitive issues, but when asked if they would like to stop the interview was keen to continue to demonstrate how they had overcome the challenges involved.

Method

A sample of 300 students was drawn from the alumni database of 1,100 who had graduated between 2010 and 2015. This can be a difficult group to access as many individuals fail to update their contact details following graduation. The sample was provided by the faculty statistician and included a representation of the following demographic characteristics: age, gender, disability, socio-economic group, education, motivation for study, occupation and ‘qualification intention’ which indicates what qualification the student had designated as their intended exit qualification.

The 300 graduates received correspondence inviting them to participate in the study which would involve a telephone interview. At this point invitees were told they would receive an online shopping voucher in appreciation of their involvement in the study. We received a 22% initial positive response rate. This consisted of 65 participants which eventually was reduced to 51 because some could not be contacted in follow up communications. A member of the study team contacted each participant and arranged a convenient time for a telephone interview. On completion of the interview the graduate was sent an online shopping voucher in appreciation of their time.

Sample

A total of 51 graduates were interviewed: 3 male and 48 female. The proportion of male respondents was relatively low (6%) compared to the proportion of male students who were part of the overall sample (11%). As the Open University is a UK-wide university, graduates across the four nations of the UK were included in the sample; 37 from England, 8 from Scotland, 4 from Wales and one each from Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. (The Open University considers the island of Ireland as one region). There were no international students on the course.

The semi structured interviews were focussed around 4 main questions with some subsidiary questions.

What were the most influential factors that helped you to continue to study over the period of your degree?

What challenges did you have to overcome in managing to complete your studies?

What benefit has your degree in Health and Social Care been to you in relation to employment?

What could the university do differently to support students in completing their degree?

The first three questions were phrased with an appreciative inquiry approach to enable us to gather information from the graduates that focussed on what worked for them.

Data analysis

The 51 telephone interviews were recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, Citation2017) was used to analyse the transcripts. Thematic analysis is an interpretive process, whereby data is systematically searched to identify patterns within the data in order to provide an illuminating description of the phenomenon. The process results in the development of meaningful themes without explicitly generating theory (Tesch, Citation1990). Clarke and Braun (Citation2013) outline six stages of thematic analysis: familiarisation of the data, coding, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, writing up. This process was done separately by each member of the research team before meeting to discuss and check inter coding reliability. The aim of thematic analysis is not simply to summarise the data content, but to identify and interpret key, but not necessarily all, features of the data guided by the research question. In this study the researchers were guided by the AI approach and the underlying search for the ‘best of what is’. Thematic data analysis within AI research generally emphasises positive storytelling, experiences and interpretations of events (Cooperrider et al., Citation2008).

Each of the 51 transcribed interviews was read and re-read by the project team. Themes were identified and discussed. Initially 14 themes were identified, which were collapsed down to 7 themes and then on further analysis and discussion within the project team, our 4 main themes were agreed, which were:

Support from family, tutors and employers

Sub themes: The influence of tutors

Supportive feedback

(2) Flexibility of study

Sub themes: Flexibility of systems

Flexibility regarding tutorials

(3) Determination and persistence

(4) Employability

Findings

When asked what factors influenced their ability to continue studying to complete their degree, a range of answers were provided. The most frequent answers related to support provided by family, tutors, and for some from their employer. Further answers identified the flexible nature of studying at a distance.

In line with the AI approach the team were focussed on identifying how in the future the university could build on what it was already doing well. For this reason, the findings associated with family and employer support are not examined here in any further detail. Instead we concentrate below on findings related to the influence of tutors and the flexibility of university systems. From an AI perspective each of these provides opportunities to imagine and design student support that enhances and improves retention and student success. The first theme of ’support from family, tutors and employers’ had two sub themes of ’the influence of tutors’ and ’supportive feedback’.

Support from family, tutors and employers: the influence of tutors

One of the issues most graduates reported that they felt made a real difference to their experience of studying for the degree was the support provided by their tutors. Each time they started on a module they were assigned a tutor. A number of skills, qualities and approaches were reported as especially helpful. In the first instance tutors needed to be approachable. For many this was conveyed by the experience that tutors brought with them and by how they engaged and responded to students’ individual circumstances and issues:

He was probably one of the best tutors that I had. He was so easy to talk to, easy to listen to, he was really relaxed, really helpful, and he was really flexible making sure that it was a time that suited us all. It was really helpful. (17:1:8)

Some found it particularly helpful that tutors were grounded in health and social care practice:

Well I don’t think I would have got everything if we didn’t have support of tutors … .they allowed me to see through some of the study material in terms of a practical point of view, because they had experience from the field. (42:6:13)

… .(my tutor was) an educational psychologist … Instead of it just being text they could actually bring experience to the tutorials. Now that for me really helped. (12:1:3)

It was also considered important that tutors could empathise with a student’s situation and the particular pressures of managing study with other aspects of their lives:

… . At that particular time I was going through a particularly difficult spot, maybe in court for divorce or whatever, and it was particularly emotional, and then come back to it at a later date. And I was able to go over it in a bit more detail then. But again, the tutors were able to guide me because they were all understanding. They did understand … (5:5:5)

Support was also provided where a tutor would invest in the student not merely as a learner on a module but as a whole person:

… .if I’d got an assignment coming up, that is all I could focus on. I’d become a bit obsessed. The tutors kind of made me realise that it was good to take a step back and have a break and do something else even though it was difficult to do sometimes. (1:5:1)

And your tutors really want you to pass. So, I always feel … my tutors always … . want you to do well, like they’ve invested in you. (2:5:2)

In addition to empathy the graduates indicated the importance of tutors responding to student questions and concerns without being patronising. This gave students the confidence to approach their tutor;

… when I didn’t understand something and not feel that, you know, just ring and, and they’re quite happy to talk to you, talk things through with you over the phone. Even if it’s something really simple that you just get your head round, … they never put me down or anything, they just were really encouraging to make sure that I understood what I was supposed to be doing. (48:6:7)

Support from family, tutors and employers: supportive feedback

Most 60 academic credit modules (equivalent to half a year of undergraduate study) included 6 staged points of assessment. A key role played by tutors involved marking module assignments and providing the students with written feedback that could then be used to progressively develop and improve the students’ knowledge and academic writing skills. Some students indicated that they received helpful advice from written feedback given by their tutors who marked their assessment. Written feedback gave many students direction and something to build on ahead of their next assessment. There was a sense in some responses that helpful feedback could be motivational and possibly offset a poor or disappointing mark. Students also found feed forward information beneficial:

I thought the tutor feedback was excellent in almost every course that I did, I found that really useful. And it was very, it was helpful, it was positive, so even if you didn’t necessarily get the marks that you were hoping for or whatever, the fact that they would find something good to say about something you’d done was helpful. And you were always pointed in the right direction about what you needed to do to improve, which I found really helpful. (10:1:1)

even when I got a low mark I still received constructive feedback on where I was going wrong, so that I could build on that. (40:6:11)

An effective tutor provided feedback that was prompt, positive and encouraging. There was a suggestion in some comments that written feedback on assessments was a key element of teaching and learning:

Yes, the feedback was really good. Yes, the comments were always good and the feedback was always pretty prompt as well. Which was always a massive benefit because you never want to carry on any further until you’ve got feedback from your last assignments to make sure you’re on track. (7:2:2)

… .I really felt like they’d taken the time with my essays and gone into a lot of detail in the feedback. I love reading them so, yeah, it’s been very good … . (21:3:1)

I had some tutors that gave great feedback. I had one that really managed to get me to understand what was meant by critical reflection. Because I’d really, it is quite a hard concept to grasp … . And she managed to break it down really simply, so I went oh right, I’m with you. (19:1:10)

Many students referred to how they used the written feedback from tutors on one assignment to help them write the subsequent assignment. This appeared to give them confidence as they progressed through each module:

… . I’d print out the feedback, and then I’d have it by the side, so I could keep relaying back to it thinking oh well she’s told me not to write in that kind of way because it’s not very academic kind of thing. I can always relate back to it, I’d always have it there at the side of my desk thinking oh I could do that because she’s told me to maybe add these points in or whatever. It was always there when I was doing a TMA (Tutor Marked Assignment). (17:1:8)

I felt the feedback was really helpful … . most of my assignment scores generally went up a bit each time based on working on the things that they’d said on the one before, which was helpful. (28:3:8)

The feedback was reported to be balanced and skilfully written (which is a closely monitored quality measure at the Open University) so that students accepted both positive and negative comments. Written feedback could also form the basis of further tutorial discussions:

Well I liked the feedback on the essays, because you were able to build on … It allowed you to build and improve on what you were doing the next time. So, I have to say I found the tutorial, the feedback on the essays excellent … (6:2:1)

Extra support for some students made it possible for them to continue to study:

… .I was diagnosed with MS halfway through., it’s affected my cognitive faculties really badly, but I spoke to the Open University and, you know, the disability department, whatever it’s called, were fantastic. They actually sent out my tutor to my house to give me a tutorial, which is a good thing, and I got extra time for my assignments. … I was very, very, very close to giving up the degree and I spoke to a few people … .and they considered, you know, with this extra support in place that it was possible. And I ended up with a 2:1, which was great. (30:6:1)

Flexibility of study: flexibility of systems

After support the second most frequently reported factor that enabled the students to complete their degree was flexibility of study. Within this theme there were two sub themes: ‘flexibility of systems’ and ‘flexibility regarding tutorials’. In some instances, students outlined how they appreciated the flexible nature of distance learning that could be fitted in around their lives:

It was a lot more flexible than a normal university. I think it’s more flexible than normal university if you’ve got family and a job. (20:1:11)

Because there are times I can’t even get out of bed or leave the house … I think so many people have so many restrictions, but with the Open University it’s so flexible in so many ways that it gives everybody an opportunity to do it. (42:4:1)

Some students found the flexibility of learning materials in different formats and on different technological and portable platforms enhanced their learning:

Whereas my son would be at a swimming lesson, so I’d go and sit by the side of the pool and read one of my unit books. Where I didn’t have that option. I managed to get a lot of stuff put on my Kindle, so I had it a bit more transportable. (18:1:9)

For some students flexibility of studying at a time of the day that best suited them and their commitments was especially important:

… .being able to do things in my own time, so I could come in from work and do it or I could do it before work … .that meant I could still work, I could still earn a living, you know, be relatively independent. (45:4:3)

Because I work shift work and I’m a farmer. So, when I did it, it was like middle of the night and early mornings. (35:6:6)

Flexibility was particularly important with assessment deadlines and exams:

there was times when I was struggling and being able to get extensions on my TMA and, um, also feeling that I could approach my, my tutor … ., in the past … . I did study a bit at a normal university and I felt that there was far too many students, it wasn’t very personal, you know, um, and I, I just feel that the Open University is so accessible. If you are having problems, you know, there’s people you can speak to and the, the tutors are really good. (44:4:2)

Flexibility of study: flexibility regarding tutorials

Face-to-face tutorials run by their tutor at specified points in each module, were optional for students. To increase attendance the university introduced flexibility that proved helpful to many of the students that we interviewed. In particular multiple options of contact with their tutor and peers, including face-to-face tutorials and alternatives such as synchronous and asynchronous online forums were reported to be helpful. Alternatives were especially helpful for students who faced specific barriers to attending face-to-face tutorials due to their location or a lack of time due to other work and childcare commitments:

Whereas once we went to the blackboard system they were great, because I could do those even if I was having a really bad day. (19:1:10)

I never attended one tutorial. Not even an online one, I used to read them after or listen to them after. Tutor support was really good online though, you know, if you needed them or if you phoned them up, or whatever, you’d always get a reply within 24 hours, which was good. (1:5:1)

So again, being able to do it from home was a lot easier for me. Some people do prefer to go to modules, so they can be face-to-face, which I understand. It just depends on a person’s circumstances. (15:1:6)

A further dimension of flexibility appreciated by students who were unable to attend tutorials, was when a tutor made summary notes and key information available afterwards:

… .the commitments I have at home made it quite difficult to get to tutorials. But I do think, I mean I think they were very good at making the information from the tutorials accessible if you couldn’t attend. So, I never felt like I was really missing out on a huge amount.

And also, I think the tutors were very good at being accessible, so I always felt if I had a question or weren’t sure about something that I knew I could ask them, and they would be helpful. So yeah, that was very supportive definitely. (10:1:1)

The findings suggest that tutors play a key role in retention of students who may otherwise stop studying as a result of skill deficiencies and initial poor results. Flexible tutors who were supported by flexible university systems and resources were an important component of success for many graduates. The tutors used tools and options designed to ensure that learning was individualised and accessible and responsive to individual student needs.

Discussion

This study set out to identify, from successful students, what factors contributed to them persisting in their distance learning studies over a prolonged period of time to complete their degree. Two key findings in our study were that, for the students, support from family as well as tutors, and flexibility of both the time when they could access learning materials, and the availability of the tutorials, were what helped them to continue with their studies to complete the degree. Davidson and Wilson (Citation2014), who explored factors that influence student retention on a course, found that family, employers and employment were a key factor. In our findings, students stated it was a combination of family, tutors and employers who provided the support that enabled them to complete their studies. Also, in line with our findings is the work of Gilmore and Lyons (Citation2012) who found that good student support in online courses helps retention.

This study took an appreciative inquiry approach which may be distilled into two key questions:

What, within the context of open and distant learning, have we been doing well to ensure students stay and succeed?

How can we organise and develop in the future and build on what we have learnt about the positive experiences of successful students?

These two questions align with the first two stages of Cooperrider and Whitney (Citation2005) 4D cycle of Appreciative Inquiry; ‘Discovery – what gives life?’ and ‘Dream – what might be?’ In response to the first question, we discovered that the two key factors that had a positive influence in enabling students to persist in their studies were support from family, tutors and employers and flexibility of when to study as well as where to study. The support provided fostered the students’ learning and the flexibility enhanced students’ sense of autonomy.

In response to the second question, and looking at what might be, in recognition that our sample represented the minority of students who started studying for a degree, there is the possibility of increasing our support in a more focussed and proactive way to ensure that all students at the beginning of their studies are made aware of what support is available as well as the nature and extent of flexibility that underpins the programme. By doing so, when students are faced with challenges they are more likely to approach a tutor for advice, rather than deciding to withdraw from the programme without speaking to a tutor. Such support could increase our student retention and enable higher numbers of students to complete their degree.

Dimensions of support

In our study one aspect of tutor support was the feedback they received from their tutors on their assessed work, which students seemed to value highly, describing it as motivational and forward looking. Students described receiving feedback that was positive and encouraging, and was written in such a way that students could identify how to build on their work in subsequent assignments. Tait (Citation2014) suggests that in distance learning, student support should be understood as integrated with teaching and assessment, not separately organised, structurally and professionally. Cameron, Roxburgh, Taylor, and Lauder (Citation2011) in reviewing why students stay on nursing and midwifery programmes, found that two features respondents had in common were personal commitment and good support. The motivational nature of the feedback is likely to have reinforced the students’ commitment to completing their degree. Farajollahi and Moenikia (Citation2010) in their findings of an evaluation of online and print based courses, stated that the relationship between student support and academic achievement was statistically significant, suggesting that when support was effective student outcomes were positive. The students we interviewed not only found the feedback from tutors supportive, they used it proactively in their next assessed piece of work.

The positive impact of support in this study was also evident when students experienced stressful situations in their life. Rather than these challenges leading to them ceasing their studies, they sought help and support from their tutors by extensions and deferrals so that they could still achieve their goal of completing their degree. This level of perseverance was striking and suggests that students had managed to develop resilience, which may have been due in some part to the confidence they placed in their tutors and the support they received. This finding of student support having a positive influence is supported by a number of research studies: Grillo and Leist (Citation2014) reviewed six years of data on student academic support and retention to graduation, finding that more time engaged in academic support meant that students were more likely to continue to graduation. This finding is reinforced by Baxter (Citation2012) who conducted a small-scale qualitative study of distance learning students and found that expectations, identities and support of students were influential in the resilience of students and their motivation to remain on a course.

Flexibility

The second influential factor which contributed to their success, reported by students, was the flexibility offered by the Open University and their tutors. Cole, Shelley, and Swartz (Citation2014) found that ‘convenience’ was the most cited reason for satisfaction. Some of our students described the convenience of having resources and delivery platforms enabling them to study anytime or anywhere. This meant that it could be in the middle of the night, or before or after work, but also in a car, or by the side of a swimming pool. Flexible provision has also been found to have the potential to enhance student learning, widen opportunities for participation in higher education, and develop graduates who are well equipped to contribute to a fast-changing world (Barnett, Citation2013). It was clear from the responses of some of our students that they had deliberately chosen to study at the Open University as the flexibility it offered meant they could make study fit around their other commitments of work and family, rather than having to do the opposite, which would perhaps have made study inaccessible to them. Huang, Hsiao, Tang, and Lien (Citation2014) explored the perceived advantages of flexibility in relation to mobile learning and found that for some students it meant being able to manage work, learning and personal activities more conveniently as well as self-management of learning.

Butcher and Rose-Adams (Citation2015) suggest that in distance learning, flexibility is critically important, with the need for institutions to maintain the highest levels of responsiveness in order to adequately support their students. Flexibility can mean course access which is anywhere, anytime, or it might mean flexibility in the curriculum (Burge, Campbell Gibson, & Gibson, Citation2011). In this study students reported being able to access their learning materials by the side of a swimming pool, as well as before or after work, or in the case of a farmer, in the middle of the night.

Intrinsic motivation

Although the findings, as reported here, clearly indicate that support and flexibility were important factors that motivated these students to persist in their part-time distance study over a prolonged period of time, what is not obvious is what internal factors helped the students to persist.

There were clearly many external motivating factors, such as the desire to gain a qualification and, within the degree programme, the desire to complete each module, but it is worth considering the likely influence of intrinsic motivation and the part it may have played in their persistence and success.

Intrinsic motivation refers to doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable and is deemed an important construct, reflecting the natural human propensity to learn and assimilate (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000a). Lemos and Veríssimo (Citation2014) found that intrinsic motivation leads to better achievement in school. These findings were supported by Vatankhah and Tanbakooei (Citation2014) who found that support from teachers (among others) significantly influenced intrinsic motivation and students were more motivated to learn. Certain factors are deemed to ‘catalyse’ intrinsic motivation, (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000b, p. 70) such as feedback that promotes feelings of competence. However, feeling competent alone is not enough to enhance intrinsic motivation, unless it is accompanied by a sense of autonomy. Therefore, Ryan and Deci (Citation2000b) contend, people need to experience satisfaction of both the need for competence as well as that of autonomy.

In this study the achievement of learning, through the six 60 credit modules of an undergraduate degree, built up the students’ confidence and competence and subsequently their resilience over time (Grant & Kinman, Citation2012), which therefore enabled them to overcome challenges and persist in their studies. Also, the very detailed and supportive feedback that students reported, provided the knowledge they needed to improve in their written assessments as they progressed through each module, and therefore increased their competence. The supportive feedback could also have contributed to the enhancement of feelings of autonomy as assessment feedback plays a central role in supporting the development of self-regulated independent learners (Black & McCormick, Citation2010).

The other main theme reported in this study was flexibility, and students rated this highly in contributing to their ability to persist and succeed in their study. Flexibility can be aligned with the concept of autonomy, whereby students made decisions about when they studied and where they studied, giving them scope to make choices in relation to their study, that would not be available in a face-to-face delivery institution.

Therefore, the two aspects of support and flexibility were acting as catalysts to enhancing these students’ intrinsic motivation, by developing feelings of competence and autonomy, which drove them to continue studying for a prolonged period of time and achieve their degree qualification.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to the study. We chose to contact graduates by post as it was deemed more effective than an email, however, by the nature of our sample we were contacting graduates who had completed their studies up to 5 years previously. This meant that some people were not at the same address. A more recent sample of graduates such as those who completed one year ago could have yielded a higher sample. Also, the relevance of some of the participants experienced could be limited as it could have been up to 10 years since they started their studies and the responses to the interview questions were based on their memory of their experience. The self-selecting nature of the respondents may have resulted in students who were satisfied with their OU study experience. The findings of this study may not be applicable to students in subject areas outside of Health and Social Care, where the gender balance is not so stark.

Conclusion

Of the two factors that students reported were key to their success, support and flexibility, the university has control over the issue of flexibility, but has only partial influence over the support that students receive, as support outside the university is also key to students being successful. Nevertheless, this doesn’t preclude us from exploring if and how we might support students to be aware of and even initiate effective family and workplace support systems.

There is the possibility that tutors could be guided to focus their initial one-to-one contact with their students on ensuring that they are aware of all the support that is available to them on their module as well as discussing what other support the student has put in place in order to be successful in meeting the demands of distance learning study. Tutors could emphasise the benefits of support and flexibility to enable students to be resilient over the period of what could be up to 6 years of study, by enabling them to develop their competence and autonomy, thereby enhancing their intrinsic motivation.

By using the findings of this study to strengthen the likelihood of more students qualifying, the appreciative inquiry will have strengthened the ‘best of what is’ across the health and social care degree programme.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students who partook of the interviews along with the Open University for funding the project. We would also like to thank Sally Ogut, Lesley Holland and Helen Evans for their support in data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joan Simons

Joan Simons, EdD, PFHEA, is an Associate Dean for Teaching Excellence in the Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies at The Open University. Her teaching areas include Leadership and Management in Health and Social Care and her research interests include exploring ways to enhance the experience of students studying through distance learning.

Stephen Leverett

Stephen Leverett, EdD, is a Lecturer (Children & Young People) in the Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies at The Open University. He has a Professional Doctorate (Education) and is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Kythe Beaumont

Kythe Beaumont is a retired Senior Lecturer in the School of Health Wellbeing and Social Care in the Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies at The Open University. Her main teaching interests are Health and Social Care and her research interests focus largely on teaching and learning at a distance.

References

- Angelino, L. M., Williams, F. K., & Natvig, D. (2007). Strategies to engage online students and reduce attrition rates. Journal of Educators Online, 4(2). Retrieved from http://www.thejeo.com/Volume4Number2/Angelino%20Final.pdf

- Barnett, R. (2013). Conditions of flexibility: Securing a more responsive higher education system. Higher Education Academy. Retrieved from http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/detail/flexiblelearning/flexiblepedagogies/conditions_of_flexibility/mainreport

- Baxter, J. (2012). Who am I and what keeps me going? Profiling the distance learning student in Higher Education. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 107–129.

- Black, P., & McCormick, R. (2010). Reflections and new directions. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(5), 493–499.

- Brown, R. (2011). Community college students perform worse online than face to face. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.com/article/Community-College-Students/128281

- Buglear, J. (2009). Logging in and dropping out: Exploring student non‐completion in higher education using electronic footprint analysis. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 33(4), 381–393.

- Burge, E., Campbell Gibson, C., & Gibson, T. (Eds). (2011). Flexible pedagogy, flexible practice: Notes from the trenches of distance education. Edmonton, Canada: Athabasca University Press.

- Butcher, J., & Rose-Adams, J. (2015). Part-time learners in open and distance learning: Revisiting the critical importance of choice, flexibility and employability. Open Learning: the Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 30(2), 127–137.

- Cameron, J., Roxburgh, M., Taylor, J., & Lauder, W. (2011). An integrative review of student retention in programmes of nursing and midwifery education: Why do students stay? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(9/10), 1372–1382.

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Over-coming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120–123.

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298.

- Cole, M. T., Shelley, D. J., & Swartz, L. B. (2014). Online instruction, e-learning, and student satisfaction: A three year study. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 15(6), p. 1.

- Cooperrider, D., & Whitney, D. (2005). Appreciative inquiry: A positive revolution in change. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Cooperrider, D., Whitney, D., & Stavros, J. M. (2008). Appreciative inquiry handbook: For leaders of change. (2nd ed.). Brunswick, OH: Crown Custom Publishing Inc.

- Cooperrider, D. L., & Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In R. Woodman & W. Pasmore (Eds.), Research in organizational change and development (Vol. 1, pp. 129–169). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Davidson, C., & Wilson, K. (2014). Reassessing Tinto’s concepts of social and academic integration in student retention. Journal of College Student Retention, 15(3), 329–346.

- Diaz, D. (2002). As distance education comes of age, the challenge is keeping the students. Chronicle of Higher Education, A39, 2002(1).

- Farajollahi, M., & Moenikia, M. (2010). The study of retention between students support services and distance students’ academic achievement. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 4451–4456.

- Flood, J. (2002). Read all about it: Online learning facing 80% attrition rates. Turkish Journal of Open and Distance Education, 3(3), 1–4. Retrieved from file://userdata/documents4/jms984/Downloads/5000103020-5000146758-1-PB.pdf

- Frankola, K. (2001). Why online learners drop out. Workforce, 80(10), 53–59.

- Gilmore, M., & Lyons, E. (2012). An orientation program to improve retention of RN-BSN Students. Nursing Education Perspectives, 33(1), 45–47.

- Grant, L., & Kinman, G. (2012). Enhancing well-being in social work students: Building resilience for the next generation. Social Work Education, 31(5), 605–621.

- Grillo, M. C., & Leist, C. W. (2014). Academic support as a predictor of retention to graduation: New insights on the role of tutoring, learning assistance and supplemental instruction. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 15(3), 387–408.

- Huang, R. T., Hsiao, C. H., Tang, T. W., & Lien, T. C. (2014). Exploring the moderating role of perceived flexibility advantages in mobile learning continuance intention (MLCI). The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(3), 140–157.

- Jenkins, R. (2011). Why are so many students still failing online? The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from: http://www.chronicle.com/article/Why-Are-So-Many-Students-Still/127584

- Lemos, M. S., & Veríssimo, L. (2014). The relationships between intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and achievement, along elementary school. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 930–938.

- Orsmond, P., & Merry, S. (2011). Feedback alignment: Effective and ineffective links between tutors’ and students’ understanding of coursework feedback. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(2), 125–136.

- Rovai, A. P. (2003). In search of higher persistence rates in distance education online programs. Internet and Higher Education, 6(6), 1–16.

- Russo-Gleicher, R. J. (2014). Improving student retention in online college classes: Qualitative insights from faculty. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 16(2), 239–260.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000a). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000b). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

- Simons, J., Beaumont, K., & Holland, L. (2018). What factors promote student resilience on a level 1 distance learning module? Open Learning: the Journal of Open, Distance and E-learning, 33(1), 4–17.

- Strahan, S., & Crede, M. (2015). Satisfaction with college: Re-examining its structures and its relationships with the intent to remain in college and academic performance. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 16(4), 537–561.

- Tait, A. (2003). Reflections on student support in open and distance learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 4(1), p.4.

- Tait, A. W. (2014). From place to virtual space: Reconfiguring student support for distance and e-learning in the digital age. Open Praxis, 6(1), 5–16.

- Tesch, R. (1990). Qualitative research: Analysis types and software tools. London: Falmer Press.

- Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125.

- Tinto, V. (1990). Principles of effective retention. Journal of the Freshman Year Experience, 2, 35–48.

- Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Vatankhah, M., & Tanbakooei, N. (2014). The role of social support on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation among Iranian EFL learners. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 1912–1918.