ABSTRACT

Self-directed learning (SDL) is necessary for successful learning in MOOCs. Motivation is one of the critical elements of SDL. This mixed-method study examined the design and delivery of MOOCs to motivate learners for SDL. The data collection methods included semi-structured interviews with 22 MOOC instructors, a document review of 22 MOOCs, and an online survey with 198 participants. The researchers found that MOOC instructors valued motivating learners for SDL. The strategies to motivate learners included entering motivations (i.e. decisions to participate in a course) and task motivations (i.e. learners’ persistence in learning activities). For entering motivation, MOOC instructors used strategies, such as identifying the value and needs of learning, increasing self-efficacy, and using incentives. For task motivation, MOOC instructors adopted engaging instructional strategies, well-designed learning materials, immediate and constructive feedback, and social interaction. Besides, technology played an essential role in motivating learners. Implications for instructors and instructional designers were discussed at the end of the paper.

Self-directed learning (SDL) is pivotal to adult education (Garrison, Citation1997; Merriam, Citation2001); especially successful learning in MOOCs (Bonk et al., Citation2015; Terras & Ramsay, Citation2015). Learners do not naturally have SDL skills and abilities and expect to receive guidance and support when starting courses (Hewitt-Taylor, Citation2001; Lunyk-Child et al., Citation2001). As such, instructors’ facilitation and support are necessary to develop learners’ SDL skills (Kell & Deursen, Citation2002; Lunyk-Child et al., Citation2001).

SDL can be categorised into three interrelated elements: (1) self-management, (2) self-monitoring, and (3) motivation (Garrison, Citation1997). Motivation influences cognitive learning outcomes (Howe, Citation1987). Individual differences in motivation and self-regulation are key learner attributes in the context of MOOC learning (Terras & Ramsay, Citation2015). Thus, it is critical for instructors to motivate learners in MOOCs. Studies on MOOC instructional design and delivery from instructors’ perspectives are scant (Margaryan et al., Citation2015; Watson et al., Citation2016; Zhu et al., Citation2018a); in particular, instructors’ perceptions regarding motivating learners to support SDL are underexamined.

Therefore, the present study examined instructors’ strategies for designing and delivering MOOCs to motivate learners for SDL as well as the technology used to motivate learners. The results will inform MOOC instructors, instructional designers, and MOOC providers about the strategies that can be used to motivate learners and thus further improve SDL skills. The following two research questions guided the study:

How do instructors design and deliver MOOCs to motivate participants to engage in SDL?

How are technologies used to motivate SDL in MOOCs?

Theoretical perspectives

Motivation and self-directed learning (SDL)

SDL is the theoretical framework used in the present study. Garrison (Citation1997) defined SDL with three closely related components: (1) self-monitoring; (2) self-management; and (3) motivation (i.e. both entering motivation and task motivation). Motivation in SDL is the primary focus of this study. Entering motivation initiates the learning effort, and task motivation maintains the effort towards learning and realising cognitive goals (Garrison, Citation1997).

Motivation can be categorised as intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation refers to behaviours that are driven by internal personal interest rather than external reward, while extrinsic motivation indicates that the behaviours are influenced by external cues and rewards (De Charms, Citation2013; Rigby et al., Citation1992). Researchers have explored strategies to increase intrinsic motivation. For example, Herrington et al. (Citation2003) stated that using authentic learning activities within online learning environments can benefit learners.

Moreover, self-efficacy has been shown to be highly correlated with students’ intrinsic motivation (i.e. Zimmerman & Kitsantas, Citation1999). Self-efficacy indicates to what extent an individual is confident about his or her performance on a learning task (Bandura, Citation1997). Students’ self-efficacy impacts their engagement and persistence in learning tasks (Pajares, Citation1996). Thus, Piskurich (Citation1996) stated that SDL tasks should be achievable for students.

Motivation and SDL in MOOCs

Studies have indicated that self-motivation and self-direction are important skills and abilities for successful learning in MOOCs (Kop & Fournier, Citation2011; Rohs & Ganz, Citation2015). As such, researchers’ attention to SDL in MOOCs has increased (Bonk et al., Citation2015). Prior research has examined students’ perceptions of SDL in general (Bonk et al., Citation2015; Loizzo et al., Citation2017) and the relations among the components of SDL in MOOCs (Terras & Ramsay, Citation2015; Zhu et al., Citation2020). For example, Zhu et al. (Citation2020) previously examined how motivation, self-monitoring, and self-management are interrelated.

Moreover, motivation, one of the critical components in SDL, has been studied in MOOC research. Motivation is related to MOOC learners’ completion rates (Brooker et al., Citation2018; Semenova, Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2019), participation, and performance (Barba et al., Citation2016). For example, Semenova (Citation2020) found that learners’ motivation is highly related to learners’ MOOC completion. Similarly, Luik and Lepp (Citation2021) categorised 1,181 MOOC learners, based on their questionnaire results, into four clusters: (1) opportunity motivated, (2) over-motivated, (3) success motivated, and (4) interest motivated. They found that opportunity motivated learners had a higher completion rate compared to the other three clusters. In reality, learners had different motivations for enrolling in a MOOC (Loizzo et al., Citation2017). The primary motives for enrolling in MOOCs include fulfiling current needs, preparing for the future, satisfying curiosity, and building connections with other people (Zheng et al., Citation2015). In addition, Chen et al. (Citation2020) surveyed 646 MOOC learners and identified four types of motivation: (1) interest in knowledge, (2) curiosity, (3) connection and recognition, and (4) professional relevance.

Moreover, researchers have explored specific strategies to motivate learners in MOOCs. For example, Hew and Cheung (Citation2014) found that approximately two-thirds of the MOOCs in their review offered certificates to motivate students. Some students like to obtain as many course certificates as possible (Young, Citation2013). Other studies have present contrasting findings regarding the use of certificates in MOOCs, suggesting that (1) MOOC certificates are not valued by society (Parr, Citation2013) and (2) such certificates are not a sufficient incentive for completing a MOOC (Fini, Citation2009). In addition to certificates, badges are another method MOOC instructors use to demonstrate students’ completion of an entire MOOC or part of a MOOC (Conole, Citation2016). However, Abramovich et al. (Citation2013) discovered that badges were not appropriate for all learners. They found that alternative types of badges might affect learners differently according to their varying initial motivations and prior knowledge.

In addition, Deshpande and Chukhlomin (Citation2017) surveyed 77 MOOC learners on the influences of content, visual design, navigation, accessibility, interactivity, and self-assessment on learners’ motivation. They found that MOOC content, accessibility, and interactivity significantly influenced learners’ motivation in MOOCs. In a larger study, Cohen and Magen-Nagar (Citation2016) examined learners’ self-regulation, motivation orientations, and sense of achievement in MOOCs by surveying 163 learners and found that collaborative learning can strongly predict students’ sense of achievement, which could further enhance motivation.

However, studies regarding how to motivate learners to engage in SDL in MOOCs from the instructor perspective are scant. In response, this study investigated instructors’ perceptions and practices regarding how to motivate learners to engage in SDL in MOOCs.

Research methods

This study used a sequential mixed methods design (Creswell & Plano-Clark, Citation2017), in which the researcher collected and analysed first quantitative data and then qualitative data. Three data sources were used: (1) semi-structured interviews (the primary data source), (2) an online survey, and (3) document reviews. The online survey was created through SurveyMonkey and sent to 1,891 MOOC instructors. Only 1,083 email requests were opened, and 198 valid responses were received. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 22 instructors, and their MOOCs were reviewed. The diverse data sources served the purpose of data triangulation (Patton, Citation2002) and provided a comprehensive understanding of instructors’ perceptions of motivating MOOC learners to support SDL.

Data collection

Online survey

The researcher developed the online survey by adapting the instrument used by Fisher and King (Citation2010) and Williamson (Citation2007), which in turn was developed following Garrison’s (Citation1997) SDL framework. To develop the instrument, the researcher of the present study interviewed four MOOC instructors and surveyed 48 MOOC instructors (Zhu & Bonk, Citation2019). Based on the pilot data analysis results, the researcher finalised the survey with a total of 29 questions. Among these, 20 questions were five-point Likert-scale questions, three questions were closed-ended questions on the instructors’ perceptions of SDL, including motivation, and six questions were related to the demographic information of the participants. Seven Likert-scale questions (Q16-Q22) concerned the strategies used to motivate learners, such as helping students embrace a learning challenge and evaluate new ideas. The demographic information was related to the MOOC instructors’ online design and teaching experiences, MOOC delivery formats, etc.

Cronbach’s alpha was conducted in SPSS 25 to test the internal reliability of the instrument using the 198 survey response data. Cronbach’s alphas for the entire survey, self-management, motivation and self-monitoring were respectively, 0.888, 0.742, 0.811, and 0.806, which were higher than 0.70; thus, the reliabilities of all latent variables were found to be acceptable. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with principal axis factoring (PAF) extraction methods and Promax rotation were conducted in SPSS 25. The factor correlation between factor one and three was 0.607; and between factor two and three was 0.515, both of which were larger than 0.5. Thus, the factors were sufficiently correlated to use Promax rotation. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy was 0.864, which was larger than 0.5. Such results indicated that the sample size was sufficient. In addition, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant, which indicated that at least a correlation exists among survey items. The results showed that the survey questions measured each construct well. shows the loading of the motivation factor.

Table 1. The loading of the motivation factor (n = 198, with PAF extraction and promax rotation)

MOOC instructor interviews

The semi-structured interview instrument with 12 questions was developed based on a literature review, consultation with an expert, and the survey results. The interviewees were a subset of the survey participants. The researcher selected the voluntary participants based on their survey answers. Several criteria were used to select the voluntary interviewees, as indicated in the author’s prior study (Zhu, Citation2021). First, the interviewees indicated that they considered students’ SDL skills when designing and delivering MOOCs. Second, the mean scores for the five-point Likert-scale questions were above 2.5. The researcher selected 22 interviewees to represent as many countries, subject areas, prior MOOC teaching experiences, delivery formats, and MOOC providers as possible. The 22 interviewees were from the following countries: the U.S. (n = 9), the UK (n = 6), Australia (n = 3), France (n = 1), Belgium (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), and Israel (n = 1). The subjects of their MOOCs included education, medicine and health, business, etc. The MOOCs of these 22 interviewees were provided by Coursera (n = 8), FutureLearn (n = 7), edX (n = 4), Blackboard (n = 2), and Udacity (n = 1). Among the 22 interviewees, their online or blended teaching experiences varied. Six interviewees had prior experience of teaching five or more online or blended courses, and seven had no previous online or blended teaching experience. Their MOOC design or teaching experiences were limited, as most interviewees (n = 13) had only designed or taught one MOOC.

The interviews were conducted via Zoom, an online conference tool. Each interview lasted approximately 30–60 minutes and was video recorded. The data reached saturation with 22 interviews, given that limited new information was found in the last few interviews (Creswell & Plano-Clark, Citation2017; Merriam, Citation2009); therefore, the researcher stopped interviewing more instructors.

To enhance the trustworthiness of the study, the researcher adopted several strategies: (1) each interview was video-recorded and transcribed verbatim immediately; (2) member checking was conducted with each interviewee to verify the accuracy of the transcripts; and (3) a research log was kept to track the interview process and thoughts.

Document analysis

The researcher conducted document analysis by reviewing 22 MOOCs designed or taught by the interviewees before and after the interview. The researcher analysed the MOOCs from different perspectives, such as learning resources, activities, and assessments. The document review was used as supplementary data for data triangulation to increase the validity of the study.

Data analysis

The survey on motivating MOOC learners used a five-point Likert scale. Thus, descriptive statistics were conducted in SPSS and Excel. To analyse the qualitative data, the researcher conducted a classical content analysis in NVivo 12. The researcher abductively analysed the data (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2007) and conducted open coding following the methods recommended by Haney et al. (Citation1998). To perform abductive content analysis, guided by the motivation concept and research questions, the researcher read through the entire set of data, chunked the data into smaller meaningful units, labelled each small chunk with a code, and compared each new chunk of data with prior codes. For similar chunks, the researcher labelled them with the same code. Finally, the codes were categorised by similarity to form themes. The final themes included motivation and technology use. The motivation category consists of entering motivations and task motivations, while the technology use category consists of synchronous communication technologies, asynchronous communication technologies, and interactive media.

Findings

Survey participant background

The survey participants were from more than 20 different disciplinary areas, such as medicine and health, computer science, education, and business and management. A majority of the participants (51.5%) did not have any online or blended course design or teaching experience before designing or teaching their first MOOCs.

Regarding MOOC design and teaching experience, a majority of the participants (n = 118) had designed or taught one MOOC, followed by two MOOCs (n = 32), and three MOOCs (n = 21), whilst 19 had taught five or more MOOCs and four MOOCs: (n = 8).

Regarding the delivery modes of the survey participants’ MOOCs, the top mode was self-paced (n = 85). Sixty-six MOOCs (33.3%) were led by instructors with additional support, such as teaching assistants, which aligns with our prior study (Zhu et al., Citation2018b), indicating that between 35% and 43% of MOOCs were instructor-led with additional support. Twenty-nine survey participants’ MOOCs were instructor-led without additional support.

Research question 1: How do instructors design and deliver MOOCs to motivate learners to engage in SDL?

Findings from the survey

The survey measured the extent to which instructors helped students develop SDL skills in diverse components on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The majority of MOOC instructor participants motivated students to learn new information and helped students embrace a learning challenge and critically evaluate new ideas (see, ).

Table 2. Mean score and standard deviation of the specific motivation strategies that the participants’ MOOC facilitated

Findings of strategies to motivate students from the interviews and document analysis

The strategies used to motivate learners regarded entering motivations and task motivations (see, ). The following paragraphs describe the motivation-related strategies the MOOC instructors utilised.

Table 3. MOOCs’ instructors’ strategies to motivate learners

Entering motivation

MOOC learners’ decision to enrol in a MOOC included both intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. The instructors in this study indicated that they had little control over students’ intrinsic motivation; however, they perceived that intrinsic motivation could be strengthened.

To strengthen students’ intrinsic motivation, some MOOC instructors revealed that they helped students identify the value of and need for learning in the MOOCs. Some instructors attempted to increase students’ self-efficacy in the MOOCs. For example, Ashley from the U.S. mentioned that she strengthened students’ intrinsic motivation by helping them identify the learning needs and value of the content. She noted, ‘We help students figure out why they should even care about some of these topics to start with.’

In addition, MOOC instructors provided a variety of resources and strategies, such as short videos and concrete examples, to increase students’ self-efficacy in achieving their learning goals. Nine out of the 22 MOOC instructors interviewed reported that they made learning materials, such as videos, short to motivate students. The brief learning units made students feel that they could quickly finish specific learning content, which further increased their self-efficacy.

According to document analysis, the 22 MOOCs all included these types of brief videos (see, ). Most videos ranged from three minutes to ten minutes, except one MOOC that had videos of approximately 30 minutes. With short videos, students can easily finish one independent concept and obtain a sense of accomplishment, which motivates their learning in a MOOC.

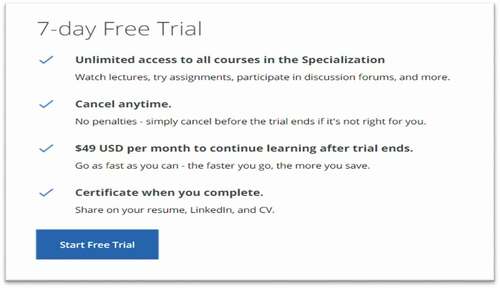

The MOOC instructors also provided extrinsic motivators at the beginning of the course. The instructors stated that they provided incentives such as certificates, badges, and credits. Five MOOC instructors stated that providing certificates can motivate students to learn and stay in MOOCs. For example, Joshua, a language instructor from the UK, mentioned, ‘I think some people were motivated by the certificate because it goes to their promotion and things like that.’ This finding was supported by the document analysis results. For example, one specialisation course allows students to obtain certificates if they finish the course; however, students have to pay a small fee of $49, as noted in .

Task motivation

Task motivation is related to students’ volition (Garrison, Citation1997). The MOOC instructors utilised different strategies to motivate students in the learning process. The motivation strategies reported by MOOC instructors fell into the following four categories: (1) instruction, (2) learning materials, (3) feedback, and (4) social interaction.

Instruction

The instructional strategies to motivate students included using debate, making learning fun, and using authentic tasks. A couple of MOOC instructors considered using debates to motivate their students in MOOCs. For instance, Aiden, a social science instructor from the UK, mentioned how he used debate to engage students. As he noted, ‘We were thinking about engagement and how you stop people from getting bored or drifting away. Because these were controversial things that students wanted to argue with each other, debate with each other, and bring their own knowledge.’

Branden, a computer science instructor from the U.S., stated that he attempted to make learning fun by using games to motivate students. He mentioned, ‘one part of that is that we try to just make the problems fun. We used Pokemon as an example.’

Seven out of the 22 MOOC instructors used authentic tasks in their MOOCs. Jackson, a medicine and health instructor from the U.S., combined his course with students’ real life experiences and jobs to motivate them.

Learning materials

In addition to instruction, MOOC instructors indicated that they motivated learners through learning materials, such as offering optional learning materials, using interactive materials, keeping learning units short and simple, and using multimedia. The optional learning materials made students feel that their learning was more personalised (Bonk et al., Citation2018), which further motivated students. For instance, a science instructor, Jason, stated, ‘All I try to do is to give them a range of possibilities that they could do.’

Interactive learning materials are another strategy that MOOC instructors used. Ben, a social science instructor from Australia, explained the use of opinion maps to motivate students. More specifically, he stated, ‘I have opinion maps. I have a lot of interactive tools that I hope will engage students to spend more time and think more about the issues raised.’

In addition, MOOC instructors used multimedia to motivate learners. According to dual-channel theory, using both visuals and audio to transmit information can reduce learners’ cognitive load (Mayer, Citation2002). This might further motivate and engage students. For instance, Paul emphasised the importance of multimedia to motivate students in the quote below: ‘It was really a multimedia experience. There were movies. There were graphs … This is something that created a lot of satisfaction and kept up the motivation.’

Feedback

Feedback is another means the MOOC instructors used to motivate students. High-quality and timely feedback has been identified as highly important for students in online learning (Tricker et al., Citation2001). The MOOC instructors revealed that they provided feedback through a variety of means, such as discussion comments, short video recordings, live videos to address questions, and progress indicators. For example, a medicine and health instructor, Joseph, claimed that providing feedback in discussion forums can motivate students. In addition, some instructors mentioned that they recorded videos to discuss various questions raised by students. For instance, Branden recorded ten minutes of video to discuss questions that students posed.

Hannah, an education instructor, provided optional weekly live video opportunities to address students’ questions. As she described, ‘Every Tuesday night, I have a live video broadcast … That is optional … I usually get around thirty to fifty people who actually tune in live and watch it. To me, it is a good motivation tool.’

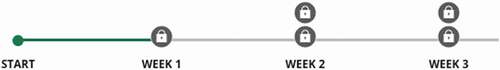

In addition, automatic feedback, such as using progress indicators, was adopted by MOOC instructors to motivate students. A medicine and health instructor from the UK, Emily, indicated exactly that in the following quote: ‘I think features like that, along with the weekly structure, the progress bar, taking off each item say “I’ve completed it.” They are all these little rewards, as tiny as they are, that help motivate you.’ This finding was supported by the document analysis results. The progress bar shows students’ learning process in a MOOC (see, ). It usually indicates the progress on certain assignments and the grades received so far. Students can easily use a progress bar to see what they have achieved, which helps boost their self-efficacy.

Most of the MOOCs analysed in the document analysis included diverse ways of assessing students’ learning and providing feedback, such as quizzes, peer assessment (see, ), and discussion participation. Through quizzes, students can immediately recognise their learning gains. Peer assessments were another method commonly used for motivating students. If students know their assignments will be assessed by others, they become more motivated.

Social interaction

The MOOC instructors in this study revealed that they encouraged social interaction to motivate students. The strategies the instructors adopted included asynchronous discussion forums, ‘like’ buttons, use of blogs, conversations through synchronous tools, use of individual student’s names, eye contact, and friendly relationships with students. A majority of MOOC instructors mentioned that they provided an online discussion forum for students’ interaction. For example, Henry mentioned that he encouraged discussion in an asynchronous forum: ‘We try to create a course in such a way there’s a thread that runs. We encourage discussion all the time.’

In addition to using asynchronous tools, some MOOC instructors reported that they used synchronous tools to promote social interaction between instructors and students to motivate learners. A medicine and health instructor from the UK, Joseph, relied on Google Hangouts to create live connections and used individual students’ names to personalise the instruction. Per Joseph, ‘we did Google Hangouts. In the Google Hangout session, students posted questions, and we responded to them. If you participate in the discussion, you posted the question. When we were talking, we would name people.’

Research question 2: How are technologies used to motivate SDL in MOOCs?

Technologies are important in MOOCs. The instructors reported that a variety of technologies were used, such as synchronous communication technologies, asynchronous communication technologies, and interactive media, to motivate learners in MOOCs.

The participants of this study shared their experiences of using synchronous technologies (e.g. Google Hangouts and YouTube Live) to meet with MOOC learners. The synchronous meetings increased the interaction among students, instructors, and teaching assistants, which further engaged learners in the course. For instance, Hannah, one MOOC instructor, leveraged Google Hangouts to make connections with learners and increase learners’ engagement. She shared that ‘making connections through live sessions made the learning more personalized. This can motivate MOOC learners.’

The interviewees reported that using asynchronous communication technologies, such as discussion forums, blogs, and social media, can motivate learners. Building a social learning community is a crucial way to motivate learners. Social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Flickr, were widely used by MOOC instructors to build a learning community. Ben used both Facebook and Twitter to engage students. According to Ben, ‘Facebook and Twitter, I used that mostly just to engage people and let people know about things.’

In addition, MOOC instructors used multimedia to motivate students, such as interactive maps, interactive timelines, videos with subtitles, cartoons, and audio recordings. For example, one MOOC instructor from Australia used Google Maps to visualise students’ locations and conversations (see, ). The map showed where the students were from and the number of students from each country or region.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations. First, the survey participants’ contact information was gathered from primary MOOC provider websites, such as Coursera and edX; therefore, MOOCs from non-English websites were excluded. Future research could focus on MOOCs whose vendors are from non-English-speaking countries. Second, this study primarily used self-reported data sources, such as surveys and interviews. To increase the trustworthiness of the data, future researchers could include data sources such as learning outcomes and log data to verify whether the motivation strategies reported by MOOC instructors are actually effective.

Discussion and significance of this study

This study examined instructors’ strategies of designing and delivering MOOCs to motivate learners for SDL as well as the technologies used to motivate learners in order to inform other instructors, instructional designers, and administrators about effective strategies for motivating learners in MOOCs. The findings of this study indicated that MOOC instructors considered motivation to be a highly important element in the initiation and continuance of learning in MOOCs; such results support Barba et al.’s (Citation2016) finding that a positive relationship exists between learner motivation, participation, and performance in MOOCs. The MOOC instructors surveyed in this study used diverse strategies for entering motivation and task motivation.

Entering motivation

First, the MOOC instructors inspired students’ intrinsic motivation by helping students find the value of and need for learning in MOOCs. This finding supports Bonk et al.’s (Citation2015) finding that the internal need for self-improvement is one of the key motivational factors of more open forms of education. Thus, it is vital for instructors to help learners identify their personal learning needs.

Second, the entering extrinsic motivations provided by the MOOC instructors included certificates, badges, and credits as possible rewards at the end of the course. The finding regarding the use of certificates to motivate learners aligns with the findings of Hew and Cheung (Citation2014) but differs from those of Parr (Citation2013), Fini (Citation2009), and Hew and Cheung (Citation2014) found that approximately two-thirds of the MOOCs in their review offered certificates to motivate students. In contrast, other researchers have argued that certificates are not a sufficient incentive for completing a MOOC (Fini, Citation2009) nor are they valued by society (Parr, Citation2013). Therefore, instructors and instructional designers may consider using both internal motivation and external motivation in MOOCs.

The finding regarding the use of badges to motivate learners aligns with the finding of a prior study (e.g. Conole, Citation2016). However, Abramovich et al. (Citation2013) stated that badges were not appropriate for all learners, and alternative types of badges might affect learners with varying initial motivations and prior knowledge. Thus, instructional designers should be cautious when utilising badges in education.

Several of the MOOC instructors in the present study worked at institutions that offered credits for students who completed or passed a MOOC. In such situations, students could transfer the credits obtained from the MOOCs to a residential or online degree program at a reputable university. Importantly, Chamberlin and Parish (Citation2011) stated that students who enrolled in a MOOC aiming to obtain credit were more engaged in learning and completing the course. In response, higher education administrators and institutions might consider offering credits to motivate learners.

Task motivation

To promote students’ task motivation, the instructional strategies the instructors used included debate, making learning fun, and authentic learning activities. The findings of this study regarding the use of fun instruction methods to motivate students in MOOCs confirm the finding of Bonk et al. (Citation2015) that making learning fun is key to success for students’ learning in open education. For example, instructors might use badges or humour in MOOCs to motivate learning.

In addition, the MOOC instructors granted ownership of learning to students to motivate learning. Stefanou et al. (Citation2004) proposed three different ways to grant students ownership of their learning in classrooms, which included offering students decision-making roles, providing choices, and giving students self-evaluation opportunities. These strategies could be used in both MOOCs and traditional classrooms.

Moreover, the present study found that MOOC instructors motivated learners through learning materials, such as offering optional learning materials and providing learning materials with appropriate difficulty levels. Moore’s (Citation1989) interaction model categorised online interaction into three aspects: (1) learner-content, (2) learner-instructor, and (3) learner-learner interaction. MOOC learning environments often lack student and instructor interactions (Chen, Citation2014; Khalil & Ebner, Citation2015). Thus, the interaction between learners and learning materials (content) is vital in students’ learning process. Most of the learners might be lurkers in MOOCs and mainly interact with the provided learning materials. Therefore, the quality of learning materials is important to motivate students. Optional learning materials give students a sense of control over their learning and grant students ownership of their learning (Stefanou et al., Citation2004), which further motivates students.

In addition, the current study found that the MOOC instructors considered it important to provide learning materials with an appropriate level of difficulty while increasing the difficulty level gradually, thereby potentially fostering learners’ self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997; Bandura & Schunk, Citation1981) and elevating their motivation to succeed (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, Citation1999). Therefore, instructors have to consider the difficulty level of the MOOC based on the target learners’ needs.

In addition, the MOOC instructors reported that short learning units could encourage students to focus on proximal goals, which, if achieved, could give the students a sense of achievement and boost their self-efficacy. As Bandura and Schunk (Citation1981) stated, having proximal goals can help demonstrate students’ growing capability. Thus, MOOC instructors could help learners increase their self-efficacy by setting brief learning goals and providing short learning units. Such a finding also supports Piskurich’s (Citation1996) statement regarding the importance of making sure that SDL tasks are achievable for students. Small chunks of learning materials enable learners to finish small learning units fast and gain a sense of achievement, which leads to higher self-efficacy.

Moreover, the findings of this study indicated that the use of interactive materials and multimedia simultaneously provided different information channels to help students become motivated, which supports multichannel communication theory (Dwyer, Citation1978; Moore et al., Citation1996). Thus, MOOC instructors and instructional designers can work with the media design and development team to produce high-quality multimedia resources.

As research has indicated, feedback on students’ performance can promote their learning (Collis & Margaryan, Citation2005), and it is vital to provide feedback to students. Since it is impossible for instructors to provide direct or immediate feedback on thousands of submitted assignments, MOOC learners are often demotivated (Watson et al., Citation2016). The most common way used to provide feedback was peer assessment (Suen, Citation2014; Zhu et al., Citation2018b). The peer assessments reported by the MOOC instructors were generally provided through online discussion forums, in which students posted their assignments and provided feedback to each other. Given the diverse background and knowledge levels of MOOC students, peer feedback may face some challenges, such as peers’ sense of responsibility and the accuracy and quality of peer feedback (Zhu et al., Citation2018b), the logistics of assigning review tasks (Balfour, Citation2013), and the effectiveness of peer feedback (Meek et al., Citation2017). Similarly, in Kolowich’s (Citation2013) study, the author found that 34% of the instructors adopted peer assessment in their MOOCs; however, only 26% of the respondents trusted the reliability of peer feedback. Worse still, research has indicated that using peer assessments in MOOCs might lead to low course completion rates (Jordan, Citation2014). In contrast, some studies argue that peer feedback is as effective as instructor feedback (Cho & Schunn, Citation2007), especially when provided with proper guidance (Ashton & Davies, Citation2015). Thus, providing clear and practical rubrics to support peer feedback is vital.

In addition to peer feedback, instructor feedback was highlighted in the present study, which aligns with the findings of Margaryan et al. (Citation2015). In this study, MOOC instructors revealed several ways to provide feedback to students, such as through discussion comments, live videos with questions and answers, short video recordings, and personalised consultation. Given that participants’ satisfaction is influenced by instructor feedback (Finaly-Neumann, Citation1994), instructors can use live or recorded videos to help students experience a sense of being cared for.

The MOOC instructors in this study utilised social interaction to motivate students. This aligns with Johnson and Aragon’s (Citation2003) online learning design principles, which are related to encouraging social interaction. In the present study, the instructional strategies included the use of blogging, conversations through synchronous tools, discussion in the asynchronous forum, interaction between instructor and students, friendly relationships with students, encouraging words, etc. Such strategies help create a socially supportive learning environment. Garrison (Citation1997) viewed SDL as an integration of cognitive, motivational, and social components. Through social connections, instructors can foster a community of practice (CoP; Wenger, Citation1998).

A CoP can be formed due to the common interest in an area or can be created intentionally for learning purposes (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). In a CoP, participants share information and experiences for professional improvement (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). In a MOOC, a CoP might be formed either through official organisation by MOOC instructors or teaching assistants or through students’ automatic formation of groups, especially in xMOOCs, where students’ contributions to the course are highly valued. For instance, MOOC instructors in this study included emotional elements to motivate learners to develop a sense of a learning community. They used strategies to improve students’ self-efficacy by praising and encouraging students through emails and encouraging them to share ideas in the discussion forum. Therefore, this study found that MOOC instructors valued the learning community in MOOCs. Such findings correspond with the finding of Baxter and Haycock (Citation2014) that the community, including the surrounding forms of peer support, was highly valuable.

Based on the findings and discussion of this study, eight practical strategies which may help MOOC instructors’ design and teaching are summarised below:

1. Helping students identify learning needs and goals;

2. Designing brief learning units;

3. Providing extrinsic motivations;

4. Providing engaging instructions;

5. Making available optional, multimedia learning materials;

6. Offering immediate, constructive feedback;

7. Embedding quizzes for self-assessment;

8. Building a learning community.

Conclusion and future directions

The findings of this study provide insights into MOOC design and delivery to motivate learners and support SDL, as well as various technologies employed to motivate learners. The findings offer implications for instructors or instructional designers regarding the design and delivery of MOOCs to motivate learners to engage in SDL. Self-reported data and document reviews were used in the initial phase in the process of investigating motivation strategies. Further research on verifying whether these strategies are effective from learners’ perspectives should be conducted in future research.

The number of MOOC learners has increased dramatically, especially at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when 35 million new learners enrolled in Coursera from March to July 2020 (Lohr, Citation2020). Thus, it is vital to examine strategies to motivate learners in MOOCs to engage in SDL from the perspectives of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. As such, future studies should examine strategies to enhance self-efficacy and the ownership of learning. Other studies might explore how to appropriately use badges, credits, peer feedback, diverse learning materials, and social interaction to motivate learners to engage in SDL.

Ethical compliance

This research is in compliance with Ethical Standards.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express gratitude to Dr. Bonk, a Professor of Instructional Systems Technology (IST) department of Indiana University (IU) for his feedback and editorial suggestions related to the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Meina Zhu

Meina Zhu is an Assistant Professor in the Learning Design and Technology program in the College of Education at Wayne State University. Her research interests include online education, self-directed learning, self-regulated learning, STEM education, and emerging learning technologies. She can be reached at [email protected].

References

- Abramovich, S., Schunn, C., & Higashi, R. M. (2013). Are badges useful in education?: It depends upon the type of badge and expertise of learner. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-013-9289-2

- Ashton, S., & Davies, R. S. (2015). Using scaffolded rubrics to improve peer assessment in a MOOC writing course. Distance Education, 36(3), 312–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.1081733

- Balfour, S. P. (2013). Assessing writing in MOOCs: Automated essay scoring and calibrated peer review™. Research & Practice in Assessment, 8, 40–48. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1062843

- Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. H. (1981). Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41 (3) , 586–598 doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.41.3.586.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

- Barba, P. D., Kennedy, G. E., & Ainley, M. D. (2016). The role of students’ motivation and participation in predicting performance in a MOOC. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32(3), 218–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12130

- Baxter, J. A., & Haycock, J. (2014). Roles and student identities in online large course forums: Implications for practice. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(1), 20–40. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1593

- Bonk, C. J., Lee, M. M., Reeves, T. C., & Reynolds, T. H. (Eds.). (2015). MOOCs and open education around the world. Routledge.

- Bonk, C. J., Zhu, M., Kim, M., Xu, S., Sabir, N., & Sari, A. (2018). Pushing toward a more personalized MOOC: Exploring instructor selected activities, resources, and technologies for MOOC design and implementation. The International Review of Research on Open and Distributed Learning (IRRODL), 19(4), 92–115. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/3439/4765

- Brooker, A., Corrin, L., De Barba, P., Lodge, J., & Kennedy, G. (2018). A tale of two MOOCs: How student motivation and participation predict learning outcomes in different MOOCs. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3237

- Chamberlin, L., & Parish, T. (2011). MOOCs: Massive open online courses or massive and often obtuse courses? eLearn Magazine, 8(1). http://elearnmag.acm.org/featured.cfm?aid=2016017

- Chen, Y., Gao, Q., Yuan, Q., & Tang, Y. (2020). Discovering MOOC learner motivation and its moderating role. Behaviour & Information Technology, 39(12), 1257–1275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1661520

- Chen, Y. (2014). Investigating MOOCs through blog mining. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2), 85–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i2.1695

- Cho, K., & Schunn, C. D. (2007). Scaffolded writing and rewriting in the discipline: A web-based reciprocal peer review system. Computers & Education, 48(3), 409–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.02.004

- Cohen, L., & Magen-Nagar, N. (2016). Self-regulated learning and a sense of achievement in MOOCs among high school science and technology students. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(2), 68–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1155905

- Collis, B., & Margaryan, A. (2005). Design criteria for work‐based learning: Merrill’s First Principles of Instruction expanded. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(5), 725–738. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00507.x

- Conole, G. (2016). MOOCs as disruptive technologies: Strategies for enhancing the learner experience and quality of MOOCs. RED: Revista de Educacion a Distancia, 50, 1–18. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/red/50/2

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano-Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage.

- De Charms, R. (2013). Personal causation: The internal affective determinants of behavior. Routledge.

- Deshpande, A., & Chukhlomin, V. (2017). What makes a good MOOC: A field study of factors impacting student motivation to learn. American Journal of Distance Education, 31(4), 275–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2017.1377513

- Dwyer, F. M. (1978). Strategies for improving visual learning. Learning Services.

- Finaly-Neumann, E. (1994). Course work characteristics and students’ satisfaction with instructions. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 21(2), 14–19. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-39255-001

- Fini, A. (2009). The technological dimension of a massive open online course: The case of the CCK08 course tools. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(5), 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i5.643

- Fisher, M. J., & King, J. (2010). The self-directed learning readiness scale for nursing education revisited: A confirmatory factor analysis. Nurse Education Today, 30(1), 44–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.05.020

- Garrison, D. R. (1997). Self-directed learning: Toward a comprehensive model. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/074171369704800103

- Haney, W., Russell, M., Gulek, C., & Fierros, E. (1998). Drawing on education: Using student drawings to promote middle school improvement. Schools in the Middle, 7(3), 38–43. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ561666

- Herrington, J. A., Oliver, R. G., & Reeves, T. (2003). Patterns of engagement in authentic online learning environments. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 19(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1701

- Hew, K. F., & Cheung, W. S. (2014). Students’ and instructors’ use of massive open online courses (MOOCs): Motivations and challenges. Educational Research Review, 12, 45–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.05.001

- Hewitt-Taylor, J. (2001). Self-directed learning: Views of teachers and students. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36(4), 496–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.02001.x

- Howe, M. J. A. (1987). Motivation, cognition, and individual achievements. In E. de Corte, H. Lodewijks, R. Parmentier, & P. Span (Eds.), Learning and instruction: Volume 1 (pp. 133–146). Pergamon.

- Johnson, S. D., & Aragon, S. R. (2003). An instructional strategy framework for online learning environments. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2003(100)), 31–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.117

- Jordan, K. (2014). Initial trends in enrolment and completion of massive open online courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(1), 133–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i1.1651

- Kell, C., & Deursen, R. V. (2002). Student learning preferences reflect curricular change. Medical Teacher, 24(1), 32–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00034980120103450

- Khalil, H., & Ebner, M. (2015). “How satisfied are you with your mooc?”- A research study about interaction in huge online courses. Journalism and Mass Communication, 5(12), 629–639. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17265/2160-6579/2015.12.003

- Kolowich, S. (2013, July 8). A university’s offer of credit for a MOOC gets no takers. The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/article/a-universitys-offer-of-credit/140131/

- Kop, R., & Fournier, H. (2011). New dimensions to self-directed learning in an open networked learning environment. International Journal for Self-Directed Learning, 7(2), 1–19. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dfdeaf_b1740fab6ad144a980da1703639aeeb4.pdf

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557–584. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

- Lohr, S. (2020, May 26). Remember the MOOCs? After near-death, they’re booming. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/26/technology/moocs-online-learning.html

- Loizzo, J., Ertmer, P. A., Watson, W. R., & Watson, S. L. (2017). Adult MOOC learners as self-directed: Perceptions of motivation, success, and completion. Online Learning, 21(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i2.889

- Luik, P., & Lepp, M. (2021). Are highly motivated learners more likely to complete a computer programming MOOC? International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 22(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v22i1.4978

- Lunyk-Child, O. I., Crooks, D., Ellis, P. J., Ofosu, C., & Rideout, E. (2001). Self-directed learning: Faculty and student perceptions. Journal of Nursing Education, 40(3), 116–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-20010301-06

- Margaryan, A., Bianco, M., & Littlejohn, A. (2015). Instructional quality of massive open online courses (MOOCs). Computers & Education, 80, 77–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.005

- Mayer, R. E. (2002). Multimedia learning. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 41, 85–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(02)80005-6

- Meek, S. E., Blakemore, L., & Marks, L. (2017). Is peer review an appropriate form of assessment in a MOOC? Student participation and performance in formative peer review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(6), 1000–1013. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1221052

- Merriam, S. B. (2001). Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2001(89), 3–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.3

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

- Moore, D. M., Burton, J. K., & Myers, R. J. (1996). Multiple-channel communication: The theoretical and research foundations of multimedia. In H. D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology (pp. 851–875). Macmillan Library Reference.

- Moore, M. G. (1989). Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

- Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 543–578. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066004543

- Parr, C. (2013). Coursera founder: MOOC credits aren’t the real deal. Times Higher Education, 2085, 12. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/coursera-founder-mooc-credits-arent-the-real-deal/2001085.article

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325002001003636

- Piskurich, G. (1996). Self-directed learning. In R. Craig (Ed.), The ASTD training & development handbook (4th ed., pp. 453–472). McGraw Hill.

- Rigby, C. S., Deci, E. L., Patrick, B. C., & Ryan, R. M. (1992). Beyond the intrinsic-extrinsic dichotomy: Self-determination in motivation and learning. Motivation and Emotion, 16(3), 165–185. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991650.pdf

- Rohs, M., & Ganz, M. (2015). MOOCs and the claim of education for all: A disillusion by empirical data. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(6), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i6.2033

- Semenova, T. (2020). The role of learners’ motivation in MOOC completion. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2020.1766434

- Stefanou, C. R., Perencevich, K. C., DiCintio, M., & Turner, J. C. (2004). Supporting autonomy in the classroom: Ways teachers encourage student decision making and ownership. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_2

- Suen, H. K. (2014). Peer assessment for massive open online courses (MOOCs). The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i3.1680

- Terras, M. M., & Ramsay, J. (2015). Massive open online courses (MOOCs): Insights and challenges from a psychological perspective. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 472–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12274

- Tricker, T., Rangecroft, M., Long, P., & Gilroy, P. (2001). Evaluating distance education courses: The student perception. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 26(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930020022002

- Watson, S. L., Loizzo, J., Watson, W. R., Mueller, C., Lim, J., & Ertmer, P. A. (2016). Instructional design, facilitation, and perceived learning outcomes: An exploratory case study of a human trafficking MOOC for attitudinal change. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(6), 1273–1300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9457-2

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning as a social system. Systems Thinker, 9(5), 2–3. https://moo27pilot.eduhk.hk/pluginfile.php/415222/mod_resource/content/3/Learningasasocialsystem.pdf

- Williamson, S. N. (2007). Development of a self-rating scale of self-directed learning. Nurse Researcher, 14(2), 66–83. https://search.proquest.com/openview/c7980aea8ee20b570c57e9102cf5b9ea/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=33100

- Young, J. R. (2013, May 20). What professors can learn from ‘hard core’ MOOC students. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/What-Professors-Can-Learn-From/139367

- Zhang, Q., Bonafini, F. C., Lockee, B. B., Jablokow, K. W., & Hu, X. (2019). Exploring demographics and students’ motivation as predictors of completion of a massive open online course. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(2). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i2.3730

- Zheng, S., Rosson, M. B., Shih, P. C., & Carroll, J. M. (2015). Understanding student motivation, behaviors and perceptions in MOOCs. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 1882–1895). ACM. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2675217

- Zhu, M., Bonk, C. J., & Doo, M.-Y. (2020). Self-directed learning in MOOCs: Exploring the relationships among motivation, self-monitoring, and self-management. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(5), 2073–2093. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09747-8

- Zhu, M., Bonk, C. J., & Sari, A. R. (2018b). Instructor experiences designing MOOCs in higher education: Pedagogical, resource, and logistical considerations and challenges. Online Learning, 22(4), 203–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i4.1495

- Zhu, M., & Bonk, C. J. (2019). Designing MOOCs to facilitate participant self-directed learning: An analysis of instructor perspectives and practices. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 16(2), 39–60. http://publicationshare.com/pdfs/Designing-MOOCs-for-SDL.pdf

- Zhu, M., Sari, A., & Lee, M. M. (2018a). A systematic review of research methods and topics of the empirical MOOC literature (2014–2016). The Internet and Higher Education, 37, 31–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2018.01.002

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (1999). Acquiring writing revision skill: Shifting from process to outcome self-regulatory goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91 (2) , 1–10. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/1999-03660-006.html

- Zhu, M. (2021). Enhancing MOOC learners’ skills for self-directed learning. Distance Education, 42(3), 441–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1956302