ABSTRACT

This article presents topological genealogy (TG) as a methodology to research transnational digital governance, and particularly how digital infrastructures are implicated in enacting such forms of governance. Inspired by the field of social topology, TG is centrally interested in investigating the conjoined production of digital infrastructures and present-day education policymaking as governance; as well as how both produce, and are produced by, processes of flows and change. Notably, the TG methodology helps to disentangle digital governance in, through and as change. Through a worked example of the European Commission’s eTwinning platform, the article shows TG in action, and complements the topological analysis with methodological foregroundings. These show how the methodology impacts as much the fabrication of research data and its subsequent analysis as it impacts the doings of the researcher.

Introduction

Policymaking is increasingly stretching beyond, overflowing and flattening the territorial borders of the Westphalian nation-state. Once the exclusive affairs of national governments, policy constellations are now characterized by: relation-forming away from spaces defined by national boundaries; the increasing porosity of such boundaries; and an accelerating transfer and diffusion of transnational policies beyond and across borders (Peck and Theodore Citation2015; Lewis Citation2020a). In education policymaking, two developments particularly reflect this moving away from the nation-state. First, different intergovernmental organizations (IOs), such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the European Commission (EC), have expanded the range and scope of their policy initiatives in recent decades. In the context of the OECD, one of the most salient examples is the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which constructs policy spaces with a global ambition, scope, and reach, thereby homogenizing educational systems and making them commensurable (Gorur Citation2017). Similarly, the EC has actively deployed education as a ‘European flagship initiative’ (European Commission Citation2014). Through sophisticated apparatuses and practices of soft law (e.g., the Open Method of Coordination), and stressing national autonomy and agency (i.e., subsidiarity), we can see the fabrication of a growingly uniform, connected and supranational ‘Europe’. This European space is characterized by downgrading internal (i.e., national) borders and, simultaneously, reinforcing the external boundaries of what Europe is and ought to become (Lawn and Grek Citation2012; Nóvoa Citation2013). Taken together, these examples exemplify how IOs and their associated programs govern via ‘acting at a distance’, actively constructing distinct educational spaces beyond those confined by national borders (Clarke Citation2015).

Second, emerging techniques of digital governance are another key manifestation of the nation-state being actively transgressed by education policies globally. Digital education governance refers to the rise of data-driven styles of governing that infuse education and the education policy sector with a broad digital instrumentation (Williamson Citation2016). Such digital instrumentation (comprising, inter alia, digital platforms, websites, software packages and apps) helps to bypass the nation-state and governmental processes of policymaking by being directly adopted in the classroom, and this without the active promotion, curation or control by governments or bureaucracies. Instead of governing ‘at a distance’, this instrumentation tends to materialize and operationalize ‘up close’ (i.e., directly within educational practices themselves), thereby ‘short-circuiting’ traditional governing logics (ibid.; Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal Citation2018). Growing rapidly in size and scope, this instrumentation – and its associated digital technologies (such as learning analytics, algorithms and code) – is becoming so intertwined with the educational sector that it is increasingly common to conceive of it as an infrastructure, which operates beyond traditional governing infrastructures constituted and/or provided by the nation-state (Gulson and Sellar Citation2019; Easterling Citation2014).

These emerging digital-educational infrastructures – and processes of infrastructuring – are active governing devices with inscribed visions of what good education, teaching and learning ought to be. A crucial insight is therefore that digital infrastructures, as assemblages of multifarious technologies and instrumentations, do not merely represent educational actors (e.g., in the form of digital datasets). Rather, these infrastructures also actively change these actors and help bringing them into being (Hartong and Piattoeva Citation2021; Jarke and Breiter Citation2019; Grommé and Ruppert Citation2019), whereby the act of making something or someone representable, observable and governable, ultimately alters the one being observed (Williamson Citation2016, 124; Jensen and Morita Citation2017; Lawn Citation2013). Far from being static monoliths of neutrally stored information, such infrastructures are profoundly relational and in a state of constant change, flux and (re)creation (e.g., Decuypere Citation2021; Piattoeva and Saari Citation2020; Lewis and Hartong Citation2021; Kornberger, Pflueger, and Mouritsen Citation2017).

Whereas the upsurge of IOs and digital education governance has received considerable separate academic attention, they arguably need to be analyzed conjointly to better understand how education policies are overflowing the boundaries of traditional nation-states. For instance, we note that IOs are increasingly deploying digital infrastructures in the educational field, and that a large share of digital-educational infrastructures operate, or aspire to operate, transnationally, rather than being restricted to the nation-state (e.g., Decuypere Citation2016; Williamson Citation2020). However, the study of digital infrastructures and digital infrastructuring as forms of transnational education governance – and vice versa – remains an inchoate field. Although academic interest is rising, it still lacks coherent methodological approaches that might scrutinize how such governance is produced and the generative effects of this production (for some first attempts, see Decuypere and Landri Citation2021; Lewis Citation2020b). This nascent field of study can presently be characterized as largely consisting of case studies (e.g., of specific website, platform or app interfaces), or delineated instances of digital infrastructures that contribute to the transnationalization of education governance. As such, some argue the field risks becoming overly descriptive and reliant on the (limited) study of what is happening at the digital interface alone, thereby neglecting the situated and profoundly processual-relational nature of these infrastructures (e.g., Bratton Citation2015; Piattoeva and Saari Citation2020).

In response, this paper advances such a processual-relational understanding of digital infrastructures and forms of transnational digital education governance as a distinctively new approach to governing the educational sector (Williamson Citation2016). Our specific aim is to present a methodology that we call topological genealogy (henceforth TG), or genealogies practiced with a topological lens. TG is dedicated to investigating the conjoined production of digital infrastructures and present-day policymaking as governance, as well as how both produce, and are produced by, processes of flows and change. We start this paper with a concise outline of both topological and genealogical thinking, which form the theoretical vantage points of our methodology and allow us to disentangle transnational digital governance in, through and as change. Consistent with the fluid and heterogeneous nature of transnational digital governance and its associated infrastructure-making, we continue this paper by presenting TG through the analysis of a worked example: the EC’s eTwinning platform. We seek not to provide a generic methodological ‘how-to’ guide but instead show the methodology in action; that is, how TG can be concretely deployed (Mol Citation2002, 152–160). Unfolding how the methodology allows us to investigate governance in/through/as change, we complement each analytical section with a methodological foregrounding to show how the methodology impacts as much the fabrication (rather than ‘collection’) of research data and its subsequent analysis, as much as it impacts the researcher.

Outlining a topological genealogy approach

Topological thinking

Topological thinking is centrally interested in change as one of the most central and shared conditions of our times, whereby ‘culture is increasingly organized in terms of its capacities for change: tendencies for innovation, for inclusion and exclusion, for expression, emerge in culture as a field of connectedness, that is, of ordering by means of continuity, and not as a structure based on essential properties, such as archetypes, values or norms, or regional location’ (Lury, Parisi, and Terranova Citation2012, 5). Topology considers relations to be of foremost importance, as these relations allow new kinds of connectivity and order, and limits, to emerge (Allen Citation2016). Moreover, topological understandings of space and time are no longer a priori formed, as in more traditional understandings of chronological time and Euclidean space. Rather than being the objective backdrop against which social life is taking place, topological space and time are relationally constructed, perpetually becoming and a result of relation making (Decuypere and Simons Citation2016; Lewis Citation2020a). As Martin and Secor (Citation2014, 431) stress,

… [t]opology does not merely direct us to the (well worn) idea that space emerges from the relations between things; it directs us to understand the spatial operation of continuity and change, repetition and difference. In other words, topology directs us to consider relationality itself and to question how relations are formed and then endure despite conditions of continual change.

Crucially, topological thinking makes a double claim: that we are increasingly living in a topological society where movement (as the ordering of continuity) and change (as shifting patterns of relations) compose the forms of present-day social practices; and that a topological lens is useful to analyze these practices (Lury, Parisi, and Terranova Citation2012, 6). In so doing, topological thinking urges a focus on boundaries, connectivities, what is interior and exterior to a particular shape, and how complex entangled events emerge. Topology is thus attentive to how spatiotemporal scales are not considered as being nested in one another (e.g., past-present-future as linearly and chronologically unfolding; micro-meso-macro as differing in size and scope), but rather in ‘the agential enfolding of different scales through one another' (Barad Citation2007, 245; emphasis added).

Genealogical-methodological thinking

In the specific context of transnational digital governance, TG first requires attention to practices of governance as they are constantly in change. Following Barad (Citation2007, 29), attending to practices in change implies to ‘be respectful of the entanglements of ideas and other materials’ present in these practices. Rather than (reflexively) pointing out similarities and/or differences between one practice (space, event, time) and another, this requires coming to an understanding of how those practices (spaces, events, times) are made through one another. Hence, investigating digital governing practices in change requires analyzing how such practices are produced, as well as how boundaries between such practices are a continuous productive enactment, rather than a pre-given ‘domain’ to which the analysis would be limited. What is needed, Barad (Citation2007, 29–30) states, are methods ‘attuned to the entanglement of the apparatuses of production, [methods] that enable (…) genealogical analyses of how boundaries are produced rather than presuming sets of well-worn binaries in advance’. For Barad, this necessitates entangled genealogies, in which the notion of ‘genealogy’ can be understood as a methodological heuristic to disentangle these entanglements and, more particularly, what these entanglements then delineate and produce precisely. The topological focus of an entangled genealogy, thus, is to start in medias res, and see how governing practices unfold through emerging relations. Taken collectively, such an approach shows the evolving multiplicity of technologies, instruments and infrastructures, and how such multiplicities actively and constitutively include and exclude, thereby figuring the world in distinct ways, assigning it a specific shape or giving it a dedicated form (Suchman Citation2012). Researching transnational digital governance in change, using TG, thus implies inquiring into the various ways in which change – and associated processes of stabilization – are being produced, enacted, facilitated and sustained by these technologies, instruments and infrastructures.

Second, TG understands educational practices through the lens of change to disentangle how these infrastructures seek to give specific educational practices a designated form. Researching education through change is not directed at how practices of governance are themselves constantly (de-)forming and taking place, but instead analyzes the productive effects of these practices in, and on, the field of education. As argued above, one of the prime characteristics of topological thinking is that it constantly scrutinizes how relations are producing specific effects. In the field of education, TG is therefore interested in the specific educational forms that are being created through practices of digital governance, throughout space, throughout time, and through the ongoing development (and sustaining) of digital infrastructures (Decuypere and Simons Citation2020; Gulson and Sellar Citation2019; Ratner Citation2019). For instance, one could think about schools taking up the relationally enacted form of spatially networked learning environments (Lewis Citation2020b), or one could think about educational practices increasingly taking up the form of delineated and temporally demarcated projects (Decuypere and Simons Citation2020; Lewis Citation2018; Vanden Broeck Citation2020). Analyzing governance through change thus implies that one considers the entangled effects of how educational practices are materially and discursively produced (amongst others by digital infrastructures).

Third, TG examines education and education governance as change to scrutinize the alleged ‘becoming topological’ of educational practices constructed in and through transnational education governance practices. Analyzing governance as change implies that one takes the entire educational-infrastructural assemblage as a ‘unit of analysis,’ and investigates whether or not (or to what extent) such policy assemblages are emblematic of broader shifts towards a becoming topological of culture (Lury, Parisi, and Terranova Citation2012), and of the educational field in particular (see also Lewis Citation2020a; Thompson and Cook 2015).

Collectively, TG adopts this tripartite focus (in/through/as change) in its empirical and methodological endeavors. It is important to stress that the purpose of this tripartite focus is analytical, rather than making ontological or epistemological claims: for analytical purposes, we distinguish between in, through, and as change, even though they should be conceived as all being part of the same relational governing plane. Likewise, we would stress that TG enables us to operate within the field of transnational digital governance, rather than ‘observing’ or ‘watching over’ the field (Lury, Tironi, and Bernasconi Citation2020). More particularly, TG as a methodology is developed to ‘better “fit” the nature of the subject studied and to simultaneously acknowledge the conditions within which the research is conducted’ (Piattoeva and Saari Citation2020, 4; equally Decuypere Citation2021). It is dedicated to investigating the conjoined production of digital infrastructures and present-day policymaking as governance, as well as how both produce and are produced by processes of flows, flux and change. As a methodological approach, TG thus deviates from a more historical (archetypically Foucauldian) understanding of ‘genealogy’ as an excavation of the conditions of possibility – a history of the present – that seeks to understand those elements of which we feel they are ‘without history’ (Foucault Citation1980, 139). Instead, and as argued, TG is interested in ‘the middle’, and in how this relational middle is shaped by – and, at the same time, shapes – past, present and future spatiotemporal ideas, rationales and configurations (Barad Citation2007; Lury Citation2012). We will now do exactly this by presenting (parts of) an (as-yet-unfinished) topological genealogy of the EC’s eTwinning platform.

eTwinning: a prototype of transnational digital governance

eTwinning is the largest community for schools in Europe. … Offering a safe online environment for cross-border education projects, eTwinning provides schools with easily accessible tools to enhance their digital learning offer and to support intercultural and cross-border contacts between teachers and pupils. Mainstreaming its use in all schools in Europe can help to boost digital competences and open up classrooms (European Commission Citation2017a, 6).

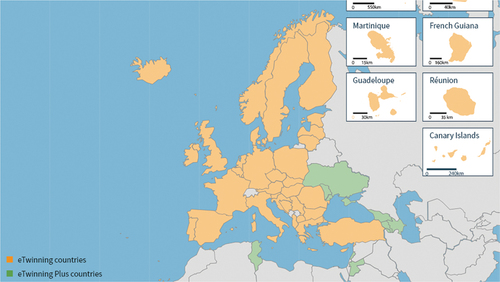

Even though the act of twinning schools has a long lineage and is thus not distinctively new, twinning schools digitally is a relatively new phenomenon. The eTwinning platform was first launched in 2005. It presently receives €13 million a year from the EC to reach over 800,000 teachers and 200,000 schools (eTwinning n.d.), reportedly ‘connect[ing] more than half of the schools in Europe’ as one of the most enduring, successful and continuous educational initiatives the EC has ever undertaken (European Commission Citation2017). eTwinning incorporates a broad range of ‘eTwinning countries’ (which are most, but not all, Member States of the EU – see ) and eight more neighbouring ‘eTwinning-plus countries’ (see ).

Table 1. The borderlands and hinterlands of ‘eTwinning Europe’. Note that the six categories are not our own categorisation but are instead derived from the eTwinning documents.Footnote1

Figure 1. The borderlands and hinterlands of 'eTwinning Europe' as displayed on the homepage of the platform, www.etwinning.net

This concise overview shows that eTwinning is a prototype of transnational digital education governance, whereby schools all over Europe are potentially connected with each other via a digital platform. It is a digital infrastructure initiated by the European Commission, funded by a European program, designed for European schools, and has over time come to include ‘neighboring countries’. eTwinning is explicitly intended to catalyze digital competence development in schools by fostering, sustaining and facilitating intercultural cooperation between participating schools.

A prelude to foregrounding the methodological gaze

And now, in a methodological and stylistic departure, we consider the broader methodological implications of TG. In this effort, we situate ourselves alongside similar recent attempts to emphasize methodological thinking as a central concern for critical policy research (for instance, see Savage Citation2013; Piattoeva and Saari Citation2020; Gorur, Sellar, and Steiner-Khamsi Citation2019). We do this foregrounding – represented here by the use of italicized and right-aligned text – after each respective analytical section (i.e., in, through and as change) to demonstrate how TG is not merely a framework for extracting meaning from data or presenting analyses after the fact. Rather, if methods and analyses are mutually derived from one another, adopting a TG approach will necessarily inform post hoc analyses and the dispositions and practices of the researcher, even before such data are even collected.

At the heart of TG is a two-fold methodological concern: i) determining what adopting a topological approach means for the research being conducted and, relatedly, ii) what this means for the researcher conducting this research. Just as we have outlined a different analytical gaze for each of the analytical dimensions of TG (i.e., in, through and as change), so too are different methodological gazes required by the researcher. To this end, we foreground a series of methodological vignettes on how we actually deployed the methodology, providing an exegesis for what we, with policy documents and websites, associated with eTwinning, as well as noting the effects of ‘what we did’ on ourselves as researchers. We hope to provide methodological insights into what is going on ‘off the page’ – the messy, contingent and contextually driven manner by which we have practiced TG.

Instead of suggesting a prescriptive quality, our methodological foregroundings show that topological analyses do not just happen by themselves but result from researchers making specific and theoretically informed, if not always entirely conscious, decisions at specific times and places. As we have noted elsewhere, concepts such as topology or mobility should always extend well beyond a useful, albeit tokenistic, set of dynamic metaphors (flowing, transferring, moving, mutating) of space and time (see Lewis Citation2020c; Decuypere Citation2021). We should not see TG as a set of tropes to superimpose upon our analyses, but rather as the means of (re)thinking what is research-able in the first place, as well as directly informing how, and to what end, we might conduct these analyses. Put differently, we wish to clearly show that TG is no conceptual sophistry but instead does something, existing methodologically via a series of explicit research(er) actions and dispositions.

Governance in change: constituting Europe(s)

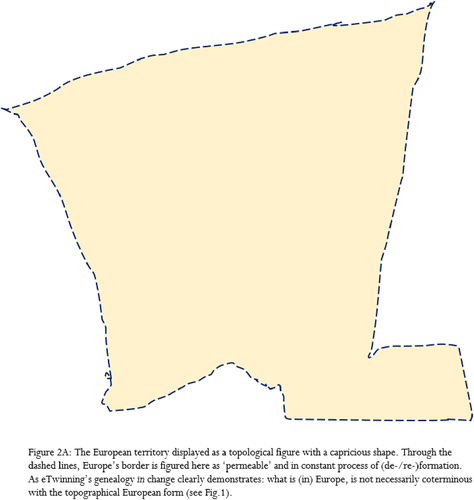

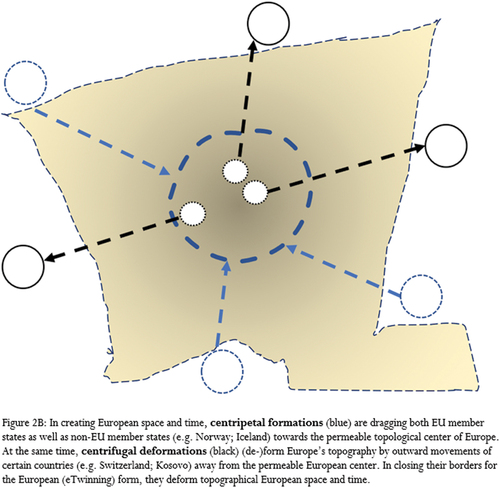

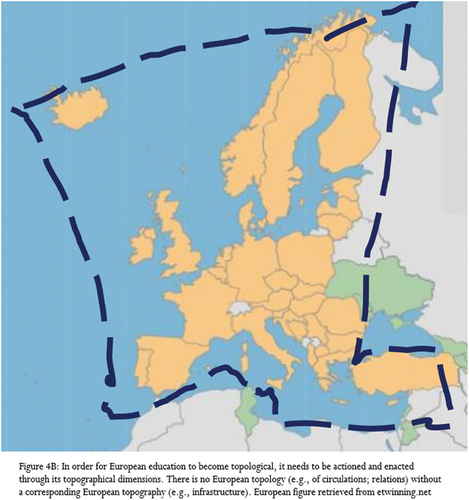

As the first part of our tripartite TG approach to understanding digital governance, governance in change explores how given digital infrastructures are productive of Europe(an space). After Suchman (Citation2012), we see these processes as ‘figuring’ the world in a dynamic and unfolding manner, with ‘Europe’ emerging through a constantly evolving process of topological assemblage (see ). Put differently, our concern with this first element of TG is processual: how the features and practices of eTwinning help shape what is understood as Europe via a multiplicity of technologies, instruments and infrastructures, and how such multiplicities actively include and exclude. We understand infrastructure here as both a connective tissue and as a means of constituting (political) space and time (Opitz and Tellmann Citation2015). Technological connectivity (i.e., the connectivity afforded by the digital infrastructure) is hereby linked to a notion of political space to create and sustain, and perhaps even extend, a ‘common’ political collective such as Europe. Such collectives are no organic, a priori, communities but are synthetic, constructed in and through a specific time and enabled through the connecting infrastructure. The processual nature of technical infrastructuring through eTwinning is thus an ongoing process of (re)assembling and (re)defining the collective spatially – what we would describe as the unfolding of Europe within the political spaces enabled by eTwinning.

When considering Europe as an ‘infrastructural collectivity’ (Opitz and Tellmann Citation2015, 172), what emerges is a European space and time constantly (re)formed and (re)bordered, where borderland becomes hinterland (and, potentially, vice versa – e.g., Brexit). Thus, eTwinning is not just a connective infrastructure to operate within Europe, but rather the means to define and delineate where, what and whom is Europe(an). In other words, the constitutive role of eTwinning is as much outward bound (i.e., centrifugal, expansionary, including new spaces) as it is inward bound (i.e., centripetal, consolidatory, reinforcing existing spaces) (). Because Europe is ‘always becoming’ as part of an unresolved project, eTwinning provides a highly specific means for Europe to ‘unfold’ as envisioned by the EC. We readily acknowledge the historical role of connectivity as an enabler of a sense of national and European community and belonging, forged discursively and materially through monuments, highways, linguistics, standardised units and measures, etc. (Anderson (Citation1991). Yet, as Galli (Citation2010, 62; emphasis added) notes, technology such as eTwinning has become the ‘indispensable condition for the creation, formation and inhabitability of modern political space’, whereby a space of technological connectivity helps to cohere and sustain specific forms of European space(s) and time(s).

Importantly, through eTwinning, the EC can build infrastructural connectivity without there being a clearly prescribed or pre-existing geographical ‘European’ space. Next to the topographical inclusion of European countries that belong to the EU and the centripetal inclusion of countries that are not part of the EU (Lacey 2017 – equally, and ), and emblematic of the processes associated with governance in change, we can also see the spatial embedding of certain territories/countries beyond the eTwinning community. This is especially the case with eTwinning-plus countries, as well as the extra-European outermost regions that are non-contiguous with other eTwinning countries. Arguably, we can see the ‘splintering effects’ (Opitz and Tellmann Citation2015, 184) of the eTwinning platform infrastructure, whereby topographical/territorial contiguity is overcome by topological connectivity and osmosis (). Such infrastructures and infrastructuring are critical to European ontology; that is, where, what and whom are at once considered and constructed as Europe and European (Opitz and Tellmann Citation2015). These processes – centrifugalism; centripetalism; osmosis – all occur through eTwinning: the notion that Europe needs to constantly expand and ‘Europeanize’ to prevent itself from becoming ‘spatially saturated’ (ibid.:183), and the use of education as a flagship initiative to do so (see above). Expansion is thus necessary to demonstrate the vitality and vibrancy of the project, both to other prospective countries and current member countries.

Arguably, neighboring countries are then encouraged to be ‘more like Europe’ via eTwinning-plus, but yet will never be entirely like the core of Europe (in a double process of un- and enfolding – see ). The participating countries and teachers in eTwinning-plus are thus, on the one hand, figured as ‘exceptional’ actors, distinguished from the broader community of peripheral countries that border Europe. On the other hand, they are clearly distinguished from the core ‘European’ countries and teachers who participate in eTwinning (rather than eTwinning-plus) (). Moreover, even while connections between European hinterlands and borderlands might well be understood as a means of inclusion, we would also argue that the presence of such borderlands can also reify the importance of traditional borders. As Billé (Citation2018) tellingly notes, ‘[t]he more we focus on cross-linkages, the more we foreground hybridity, the more we reify that [pre-existing] line’. In this sense, eTwinning-plus countries are governed as being from the European neighborhood but not being of this neighborhood (see Arendt Citation2017). While eTwinning-plus countries might well emulate some core European tendencies and practices, eTwinning positions them as facing an insurmountable divide, demonstrated by the fact that they can only ever (to the best of our knowledge) participate in eTwinning-plus as neighboring countries. They cannot ever cease to be from these European borderlands, and the ongoing presence of these borders (political, spatial, social) remains entrenched by the continuing presence of two eTwinnings: one for those within, and one for those without.

Methodological foregroundings: part I

As noted earlier, these foregroundings demonstrate the inseparable link between analysis and methodology, as well as highlighting the ‘mundane’ practices through which we translate theory into research. After presenting our analyses on governance in change, what precisely does a researcher do to research governance in change? In this first foregrounding, we explicate the practices and methodological sensibilities adopted to actively construct and analyze governance in change. First, a concern for governance in change is not about eTwinning per se, but it is more about the where(s), when(s) and whom(s) of Europe that have been made operational via eTwinning (i.e., governance practices). This methodological approach presents something of an inverted analytical gaze: rather than being concerned with how the European Commission constructs a platform such as eTwinning, we have sought to do the opposite, using eTwinning as a lens through which to observe the construction of Europe(s). This is a significant methodological departure from how one might usually attempt to apprehend what Europe(an space) is, with the digital platform being the means to view the construction and infrastructuralisation of Europe, instead of vice versa. If our analytical purpose is delineating the coming into being of various ‘Europes’ and how these change in space and time, then our methodological purpose is concerned with the processes that give shape to these figures. In other words, operationalizing governance in change requires an attention to the varied and varying borders of Europe (e.g., geographic, political, cultural …) and especially the processes of (re-)bordering that seek to include and exclude notions of Europe and European-ness (Romito, Gonçalves, and Antonietta Citation2020; Aradau, Huysmans, and Squire Citation2010; van de Oudeweetering and Decuypere Citationforthcoming; Salajan Citation2019).

While it is expressly not concerned with educational forms (this will be the substantive focus of the next section, governance through change), what we are seeking, in effect, are the ecological conditions that will subsequently give rise to different educational forms. To employ a metaphor adapted from Lury’s (Citation2012) notion of amphibious sociology, our interest at this stage is the broader ecological relations that will help to shape – or give dedicated form to – the sorts and types of educational actors that will inhabit these spaces. Importantly, this is not to suggest a deterministic or straight-forward causal relationship, in which certain ‘ecological’ conditions (i.e., spatio-temporal and bordering processes) need to give rise to particular educational forms. However, it does suggest a methodological sensibility that is concerned with first understanding the spatial-temporal ecologies and relational processes in which Europe, and European-ness, are constantly being (re)formed, and foregrounding these when it comes to understanding the potential educational forms that might emerge therein.

Specifically, we first collected all available documents associated with the eTwinning platform, using the search function embedded in the ‘Publications’ page of the EC (https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications_en). These documents were saved into a OneNote database to create a ‘research infrastructure’ out of this data infrastructure, which was then tabulated and annotated through reference to particular EC policies, nation-state responses to these policies, and notions of (re-)bordering of Europe. We especially paid attention to spatial constructions of Europe over time, how this translated into an ongoing (re-)bordering of Europe and how, in turn, this produced new understandings of who and what are included and excluded from such spaces. Afterwards, we made tables and figures, concurrently with our own making sense of ‘what was going on in the data’, and this is what we used to ‘analyze’ the governance spaces emerging in change. This making sense was partly done by means of ‘writing accounts’, as much as it was with keeping the relationality and connectivity of database one (i.e., the European Commission online archive) and database two (i.e., our research database, or ‘database of the database’) firmly in mind. An analytical focus on borders and (re-)bordering processes therefore first requires, in a way, a methodological focus on the borders of one’s own database(s).

Governance through change: new educational relations and forms

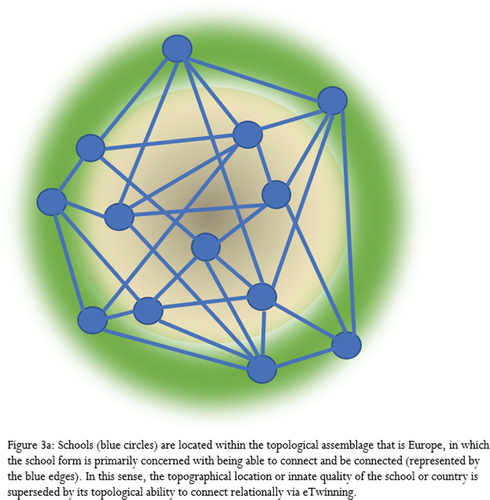

The second facet of our TG approach is concerned with governance through change; that is, the new educational forms made possible via eTwinning, as well as the relations that are constitutive of and constituted by the emergence of these forms. The focus of researching through change is not directed at how practices of governance are themselves constantly (re)forming and taking place, but is instead concerned with analyzing the productive effects of these practices in and on the field of education via the constitution of new specific educational forms. Within the broader infrastructural space of Europe, schools linked by eTwinning are arguably situated in ways that are both topographical and topological. On the one hand, these schools exist within defined borders and state-centric territories (i.e., in countries and subnational polities; at defined spatial coordinates). On the other, they are present within topological spaces that are forged by the very relations that eTwinning makes possible, irrespective of their more territorially oriented locations. It is this second spatial quality, derived from schools being situated relationally within a topological Europe, that is our primary consideration here, at least regarding the new educational forms made possible by the emergent topological European space(s).

As part of the eTwinning community, participating schools are electronically linked with other schools from all over a Europe that is constantly unfolding itself and enfolding other spaces (see ). Such eTwinning schools are from what we have described as the hinterlands and borderlands of eTwinning Europe (see ), including both EU members and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) states – what might be considered the political and geographical ‘core’ of Europe – alongside current and future EU candidate countries and European Neighbourhood Policy countries, which exist more peripherally. However, what matters most is not precisely where a school may be (topographically) located. Rather, the primary concern of the school as an educational form is relational: that it can topologically connect and be connected via eTwinning to other schools, irrespective of location (see ). The geographic coordinates of a school are thus superseded by the availability, intensity and extensity of its connections to other schools and, importantly, the EC as the administering body of eTwinning. Indeed, the only geographic characteristic that arguably retains saliency is whether a school is located in the European hinterland or borderland, and thus whether a school is eligible for eTwinning or eTwinning-plus, respectively. Beyond these distinctions, all participating schools exist within the diffuse and liquid infrastructural space afforded by eTwinning, thereby eliding the innate qualities of the schools (and, for that matter, countries) within this space. In this respect, we see extremely useful resonances with the notion of topological governance (see Allen Citation2016; Prince Citation2017), whereby governing relations serve to constitute the very spaces within which governance can be exercised and, in turn, generate effects for those being governed and governing.

Beyond foregrounding the connectivity of and between schools, the topological policy spaces made possible through eTwinning also facilitate the virtual mobility of the European educational form itself. Mobility is arguably a central motivation of the eTwinning initiative, aligning with long-standing desires to fostering a shared sense of ‘European-ness’ amongst students and citizens, regardless of where they originate or to where they travel (Banjac and Pušnik Citation2015; Savvides Citation2006; Tahirsylaj Citation2020). While this mobility was traditionally more inclined to be physical in nature (i.e., in-person travel or student exchanges), the technological connections enabled by eTwinning have more recently allowed for a decidedly more virtual experience. More than a decade ago, the European Commission (Citation2009b, 18) noted that ‘virtual mobility … is often a catalyst for embarking on a period of physical mobility’, and that ‘electronic twinning [eTwinning] can enhance the quality of mobility initiatives’. Earlier iterations of eTwinning thus positioned the virtual as subsidiary to the physical, which undoubtedly reflected the relative availability and capacity of technology - the mobility in question was arguably limited to that of the student.

However, this mobility is now no longer only embodied in students (physical or virtual) but is instead captured in the virtual mobility of the European educational form itself. Put differently, while students and citizens are still entirely capable of both physical and virtual movement, we see the idealized European educational form – where connection is the definitional quality – as the most indicative element that moves via the eTwinning infrastructure (see ). This very much reflects an inversion of what moves: it is not the pupils and schools who move, but the ideas and ideals of European education that most freely and influentially travel throughout the topological space of Europe. Beyond the unfolding of Europe as described previously (see ) and an expansion to the geographic space of Europe, we would also emphasize the virtual mobility of an idealized European educational form that suffuses throughout the spaces enabled by the eTwinning infrastructure. Rather than requiring the movement of students throughout Europe, virtual mobility brings this European notion of education directly to schools and classrooms, regardless of where they might be located in ‘Europe’.

It is interesting to note that eTwinning was originally considered as being part of the ‘mobility leg’ of the educational programs developed by the EC. More recently, the aspirational horizon became fully situated in the ambition to foster virtual mobility, which seeks to ‘equip Europe with the skills needed for the future’, as well as ‘make youth mobility the rule, rather than the exception (European Commission 2009, 21). Spatially, this emphasizes different sorts of educational forms and associated mobilities, both virtual and physical. As such, it inaugurates different versions of Europe, as well as different versions of what it means to be embedded and travel within these European spaces, drastically reforming the ontology of what and how one can ‘be European’. Whereas there was previously a stronger distinction between virtual and physical forms of presence and mobility, more recent documents have elided these differences and now more generally reference ‘mobility’, with both forms becoming indistinguishable in the documents. It therefore does not matter how you move anymore; rather, the only thing that matters is that you move (see also Decuypere and Simons Citation2020).

Methodological foregroundings: part II

After the (re-)bordering processes that have given rise to certain European spaces, the next focus of TG was governance through change. This entailed attending to the effects of the preceding figuring of European space, including the educational forms that are embedded in these emergent spaces and, in turn, how these educational forms themselves are constantly undergoing topological processes of deformation in response to their context. Returning to the previously introduced ecological imagery of Lury (Citation2012), these educational forms are considered here as the ‘organisms’ that emerge from the prevailing ‘ecological’ (or contextual) conditions.

In a methodological sense, the focus of researching governance through change is then not so much directed at how governing spaces are themselves constantly (re-)forming and taking place, but is instead concerned with analyzing the productive effects of these practices in and on the field of education. This stage of topological genealogy is specifically practiced by looking for new educational forms within the spaces forged by the (re-)bordering of educational forms, as well as how these forms are contextually situated in the changing European spaces.

For us, researching governance through change again required working with our database of databases; that is, our own actively constructed OneNote database of the EC online archive of relevant eTwinning documents. However, our attention this time was directed towards the specific examples of education practices represented in the EC policy documents, and especially how these educational forms can be directly linked to certain spatial renderings of Europe. We repeated many of the concrete (one might say mundane) steps undertaken in stage one; for instance, annotating the database to highlight particular educational forms, writing accounts, relating educational practices to certain spatializing policies, etc. These educational forms ranged from specific accounts of policies and programs intended to support the development and maintenance of the eTwinning infrastructure (e.g., Erasmus+); to retrospective evaluations reported to the EC or member states; to discussions concerning the role of education to broader EC goals for European education. Importantly, we sought to distinguish between the educational forms made possible by the respatialization of Europe wrought through eTwinning (i.e., the effects of governance in change) that were our primary focus, and the educational forms preceding eTwinning, which were not. The linearity of the methodological gaze required in governance in change to governance through change is not to reify an artificial sense of causality or order. Nevertheless, it does force us - as researchers using TG - to concede that an understanding of the ecological conditions is necessary before one can begin to consider the effects of those conditions, especially as these are undergoing constant deformation and change.

In addition, we note that a focus on form, as suggested here, also implies some sort of ‘interpretive act’ on the part of the qualitative researcher (see Peshkin Citation2000). Such interpretive acts – what Barad (Citation2007) would designate as ‘agential cuts’ – should not be read as an open license or ‘anything goes’. It is rather about creating concrete anchor points, and thereby acknowledging that interpretation is a constant act of both imagination and logic (Peshkin Citation2000, 9). This allows one to see something other than the mere reaffirming of one's own framework, while retaining the conceptual and analytical utility of (in our case) TG. In so doing, we help disentangling the problematics of our research and recognize our own role in making concrete decisions, even if we may not know in advance where those decisions will lead.

Governance as change: the becoming topological of Europe

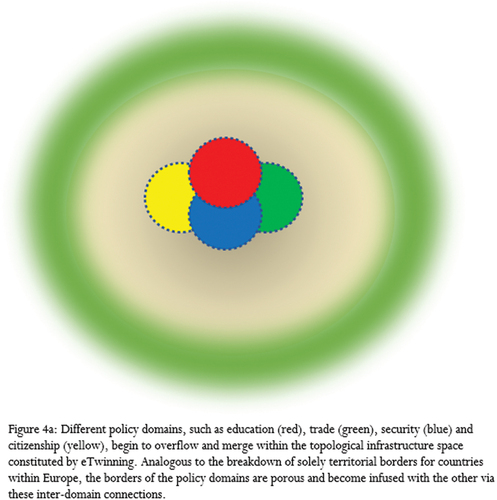

The final dimension of our analysis concerns the combined effects of emergent Europe(an spaces) (i.e., governance in change) and educational forms (governance through change) on Europe itself, in order to gauge if and how eTwinning helps constituting the becoming topological of Europe. These topological relations constitute policy spaces and, in turn, new educational forms that are virtually mobile throughout the topological eTwinning infrastructure, and it is the enduring connectedness of education via eTwinning that makes this present iteration unique from earlier European educational forms (e.g., Grundtvig, Comenius, Da Vinci). However, these connections do not only exist and function between participating schools within an education policy space. We can instead see instances where the infrastructural space enabled by eTwinning has begun to merge multiple policy domains other than education, with these topological connections then overflowing across previously firm boundaries, such as security, citizenship and trade (see ).

For instance, eTwinning is positioned as central to countering the radicalization of students via a so called ‘additional action’, in which ‘the potential of eTwinning will be fully exploited with a greater focus on themes linked to citizenship with the objective of empowering teachers to become active agents for a more inclusive and democratic education’ (European Commission Citation2017b, 8–9). Similarly, we can see the infrastructural space and relations of eTwinning expanding beyond education to also include trade via the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership. This initiative seeks to extend ‘further eTwinning-plus networks to selected countries of the EU’s neighborhood. The eTwinning-plus tool … will be further extended to other countries of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership’ (European Commission Citation2017b, 13). While the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership is ostensibly a trade agreement, it is significant to note the use of eTwinning to achieve complementary policy purposes. Rather than suggest eTwinning is being employed in distinct policy domains that retain their own identity and purpose, we would argue instead that these developments reflect the topological blending of policy domains through the connections afforded by eTwinning. As education osmoses into other cognate policy domains (e.g., security, trade, citizenship), these domains are no longer distinct, instead existing and made possible as idealized European forms – that is, as connected and able to connect within a topological European space. Such a ‘becoming topological’ of education necessarily implies that education infuses, and becomes infused with, other policy domains until their distinctions become more indistinct. In other words, governing European education cannot be done anymore as an independent activity without also, at the same time, governing other overlapping policy domains whose definitional quality is being inseparably connected.

While there is a collapsing of policy domains into a more fluid grouping of overlapping policies and practices, it is important not to generalise that all such topographical territories or demarcations entirely cease to exist in a topological rendering of Europe and European education (Allen, Citation2016; Lewis Citation2020c). One such instance of this persistence is related to the issue of subsidiarity within the EU. Here, certain responsibilities (including education) remain under the authority of the individual Member States and the EC cannot centrally compel compliance (European Commission Citation2017a, 3–4), creating a situation whereby the Member States and the EU are mutually dependent (see also Decuypere and Landri Citation2021).

Despite being a European initiative that is directed by the EC, eTwinning remains heavily reliant on the support services of the various participating states for both eTwinning and eTwinning-plus. Although this aligns with the principle of subsidiarity, it is nonetheless remarkable how the coordination of eTwinning is, to a certain extent, in the hands of Europe (via the Central Support Service and support of the EC), but the practical ‘roll-out’ is entirely dependent on how individual countries engage with the program. One could thus argue that there is no Europe without its specific countries, and vice versa: there are no specific countries without a Europe that reinstates (and reifies) the differences between them (see ). Even further, this displays the (topographical) infrastructure that needs to be put in place in order to make the (topological) circulation of students, projects, and ideas on the platform itself, possible. This suggests, we would argue, that the topological needs to be actioned and enacted through the topographical, insofar as Europe can only exist through the cooperation and even co-option of the nation-state and EU Member Nations. And, although the EC cannot compel adherence to voluntary measures like eTwinning, it can encourage adherence via discursive and material (e.g., financial) incentives. As such, we would emphasise that the becoming topological of Europe can only occur by the retention, to a greater or lesser degree, of the topographical (see also Hartong and Piattoeva Citation2021; Lewis Citation2020a).

Methodological foregroundings: Part III

Finally, after attending to governance in and through change, the last focus of our methodological gaze has been governance as change. We should re-emphasise that the three moments of TG (in/through/as change) are not positioned on different hierarchies or relational planes, but rather exist as multiple (and non-linear) temporalities (see Lingard Citation2021). Extending from the processes that gave rise to certain spatializations and (re-)borderings of Europe (‘the ecology’) and the resulting educational forms (‘organisms’) that are shaped by these changing contexts, our purpose here is addressing what might be described as the ‘second-order’ cascade of effects. To return once more to our ecological metaphor, these second-order effects might be considered as something akin to anthropogenic global warming, insofar as these educational forms are first shaped by their ecology but then, in turn, (re)shape their environment themselves. One then needs to consider how these educational forms might change European spatiality, and then – finally – how these new spaces and their educational forms can inform subsequently emergent educational forms. For instance, while the spatial figurings of Europe have arguably made certain educational forms possible, the effects of these educational forms will also help to deform Europe(s), not to mention the educational forms that are subsequently possible.

To specifically address governance as change, or the ‘effects’ of effects, we yet again turned to our database of databases. As previously, the concrete steps taken were based on earlier annotations and written accounts of EC policy documents that suggested both the factors that brought forth certain constructions of Europe(an space) and, in turn, the types of educational forms that these spaces enabled. However, we then also considered how these processes were themselves instrumental in reshaping what emerged. For instance, did certain eTwinning relationships and practices associated with education make other practices possible in putatively unrelated policy domains (e.g., education and security)? Or, how did the (re-)bordering made possible by eTwinning, with certain new countries and regions included or excluded from ‘Europe’, enable subsequent regional groupings or collectives? These examples are by no means exhaustive, but they do demonstrate our underlying methodological logic regarding the effects of ‘effects’. We would thus argue that TG urges researchers to apprehend the case (in this instance, eTwinning) via such a double movement: i) the educational form and the ecology in which it is embedded and from which it emerged, and ii) the likely and unlikely spatial and temporal effects of this form.

This methodological sensibility then engages with topology not only as a relational understanding of space but also, critically, as a relational understanding of time (see also Decuypere and Vanden Broeck Citation2020; Lingard Citation2021). If we situate TG with the broader becoming topological of culture (Lury, Parisi, and Terranova Citation2012), ‘becoming’ is then very much our foregrounded matter of concern. No longer are we solely looking to linear conceptions of past to explain the present, but rather we are now equally concerned with how past and present (re-)bordering processes and forms will likely shape what might subsequently emerge (see also Lewis Citation2018; Decuypere and Simons Citation2020). This is an explicit shift in researcher sensibility and disposition, and a reorienting of what researchers of digital infrastructures might be attuned to research. The inclusion of multiple temporalities and a related researcher disposition very much aligns with the topological thinking of TG: if things are constantly in change and in states of deformation, and these processes will themselves yield further change, then we can only ever be in the middle of things (and times). Or, perhaps more accurately, the methodological repercussions are that we are now always in the middle(s), somewhere (or sometime) between observable educational forms, and yet looking beyond to new subsequent effects that these current educational forms might well yield. And it is towards embracing this very sense of being ‘in the middle’, via our TG methodology, that we finally turn our attention.

Concluding thoughts

The implication (…) is that (…) live methods must be satisfied with an engagement with relations and with parts, with differentiation, and be involved in making middles, in dividing without end(s), in mingling, bundling and coming together. The objects of such methods – being live – are without unity, un-whole-some; put another way, they are partial un-divisible, distributed and distributing. (Lury Citation2012, 191)

The argument presented in this quote is one of the perennial considerations that develops from employing topologically informed analytics: how to develop methods that begin, and which require the researcher to be, in medias res; that is, ‘in the middle of things’ (cf. Piattoeva and Saari Citation2020)? We reiterate that the benefits of TG, and its unique contribution, are directly responding to the limitations of addressing the education work of IOs and digital education governance separately, rather than (with TG) seeing these processes conjointly. Applying this approach to our investigation of eTwinning and our development of TG, this article was centrally concerned with how different spaces and times are a posteriori constituted through being enfolded within the infrastructure, rather than the infrastructure emerging from the a priori (trans)national space. If we consider eTwinning, via TG, in terms of (re)creating Europe, we would argue, after Lury (Citation2012, 186), that ‘it coordinates an active surface of coordinatization. [It is] endowed with capacities to act, to see, in a space that is not given, but is brought into existence continuously and simultaneously with the objects it “sees” or produces. Indeed, it is the continual re-making of relations in a surface of coordinatization’.

TG is informed by broader strands of thinking in contemporary social theory that stress the importance of meticulously disentangling relations, networks, (dis)continuities, time and space to better understand the dynamic, and constantly unfolding, character of transnational digital governance (e.g., Allen Citation2016; Bratton Citation2015; Prince Citation2017). However, these theoretical lenses have not, admittedly, always been accompanied by correspondingly appropriate research methods. While the so-called ‘deluge’ of digital data has been the topic of fervent theoretical discussion for decades (e.g., Castells Citation1996; Ruppert, Law, and Savage Citation2013; Thrift Citation2005; M. Savage and Burrows Citation2007), the methodological response of social science research has been somewhat limited (see Ruppert, Law, and Savage Citation2013). It has been argued that digital research methods often neglect to proffer avenues beyond description alone (Marres Citation2012; Lury Citation2012; Piattoeva and Saari Citation2020; Michael Citation2012); or, that the prevalence of digital data is too readily equated with their potential relevance (Uprichard Citation2012). Ultimately, this risks research becoming overly reliant on a-historical and piecemeal descriptions of the myriad platforms and infrastructures that generate, collate and calculate our digital transactions, while neglecting the situated, contingent, processual and topological nature of these infrastructures (Decuypere, Grimaldi, and Landri Citation2021).

It is important to acknowledge in this respect that TG is a methodology situated in the broad field of relational thinking, and we have developed it to directly counter some of these critiques. In trying to counter those critiques, as a methodology TG allows to meticulously research the increasingly intersecting processes of transnational and digital education governance. Like any methodology that opens up avenues to see particular things well and clearer than before, this equally implies a firm understanding of what the methodology developed here does not allow to see clearly, such as an exclusive focus on individual perceptions, experiences, and subjectivities induced. By designating TG as methodology, we furthermore explicitly refrain from calling it method. Whereas ‘method’ suggests a more proceduralized way of knowing, ‘methodologies’ highlight the importance of theory in determining what counts as problems, as well as what ‘proper’ solutions might be to these problems. As such, we consider methodologies as practices that are co-constitutive of the settings of which they inquire (Decuypere Citation2021; Lewis Citation2020c; Lury, Tironi, and Bernasconi Citation2020; Law Citation2004). The experimental nature of this paper, which incorporates a constant oscillating between analytical parts and methodological foregroundings, in that sense tries to make clear how methodology and analysis are co-implicating one another and how methodologies are not to be thought of as something to (only) engage with before the actual analysis takes the start.

In sum, applying TG requires our constant attention to the shifting matter at hand, of the middle(s) that constantly emerge and re-emerge. Put differently, we see the necessity of explicitly acknowledging how data infrastructures and infrastructuring processes come to not only typify contemporary governing spaces, but how they are indeed the means by which these spaces (and times) are given form and function. As Lury (Citation2012, 193) notes, when researching from and through the middle, ontology and epistemology are ‘collapsed in an approach that enables categories and scales to be mutually adjusted to a problem that itself only emerges through the continuous application of method, process and feedback’ (see also Decuypere Citation2021). This is, arguably, less the case of a prefigured space – in our instance, the European Union and Europe – being the means by which an infrastructure (eTwinning) unfolds; rather, we see that Europe (or, at least, a particular version of Europe) is instead being enfolded within and given shape through these infrastructures. In this respect, the ‘middle’ of the Europe(s) created via eTwinning is indiscernible from any vantage point outside the infrastructure. From our perspective, any attempt to understand a data infrastructure or platform as a means of (transnational) education governance thus requires one to begin ‘in the middle’. This article has introduced TG as one way of doing so.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mathias Decuypere

Dr. Mathias Decuypere is assistant professor at the Methodology of Educational Sciences Research Group (KU Leuven, Belgium). His main interests are situated at the digitization, datafication and platformization of education; and how these evolutions shape distinct forms of educational spaces and times.

Steven Lewis

Dr. Steven Lewis is a Senior Research Fellow and ARC DECRA Fellow at the Institute for Learning Sciences and Teacher Education (ILSTE) at Australian Catholic University. His research investigates how education policymaking and governance, and topological timespace-making, are being reshaped by new forms of digital data, infrastructures and platforms. His most recent monograph is PISA, Policy and the OECD: Respatialising Global Educational Governance Through PISA for Schools, which was published by Springer in 2020.

Notes

1. These countries, as well as their respective EU and eTwinning status, are current as of January 2021.

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Aradau, Claudia, Jef Huysmans and Vicki Squire. 2010. “Acts of European Citizenship: A Political Sociology of Mobility.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 48 (4): 945–965. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02081.x.

- Allen, J. 2016. Topologies of power: Beyond territory and networks. Routledge.

- Arendt, Hannah. 2017. The Origins of Totalitarianism. London: Penguin Classics.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Billé, Franck. 2018. “Skinworlds: Borders, Haptics, Topologies.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (1): 60–77. doi:10.1177/0263775817735106.

- Banjac, Marinko, and Tomaž Pušnik. 2015. “Making citizens, being European? European symbolism in Slovenian citizenship education textbooks.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 45 (5): 748–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2014.916972.

- Bratton, B. 2015. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. MIT Press.

- Castells, Manuel. 1996. The Rise of the Network Society (The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, Volume 1). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Clarke, J. 2015. “Inspections: Governing at a Distance.” In Governing by Inspection, edited by S. Grek and J. Lindgren, 11–27. London: Routledge.

- Courtois, A. 2020. “Study Abroad as Governmentality: The Construction of Hypermobile Subjectivities in Higher Education.” Journal of Education Policy 35 (2): 237–257. doi:10.1080/02680939.2018.1543809.

- Decuypere, M. 2016. “Diagrams of Europeanization : European Education Governance in the Digital Age.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (6): 851–872. doi:10.1080/02680939.2016.1212099.

- Decuypere, M. 2021. “The Topologies of Data Practices: A Methodological Introduction.” Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 10 (1): 67–84. doi:10.7821/naer.2021.1.650.

- Decuypere, M., E. Grimaldi and P. Landri. 2021. “Introduction: Critical Studies of Digital Education Platforms.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1866050.

- Decuypere, M., and P. Landri. 2021. “Governing by Visual Shapes: University Rankings, Digital Education Platforms and Cosmologies of Higher Education Education Platforms and Cosmologies of Higher Education.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1720760.

- Decuypere, M. and M. Simons. 2016. “Relational Thinking in Education: Topology, Sociomaterial Approaches and Figures.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 24 (3): 371–386. doi:10.1080/14681366.2016.1166150.

- Decuypere, M. and M. Simons. 2020. “Pasts and Futures that Keep the Possible Alive: Reflections on Time, Space, Education and Governing.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 52 (6): 640–652. doi:10.1080/00131857.2019.1708327.

- Easterling, K. (2014). “Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space.” London: Verso. eTwinning - Homepage. (n.d.). https://www.etwinning.net/en/pub/index.htm

- European Commission. 2009b. GREEN PAPER: Promoting the Learning Mobility of Young People. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2014. 2015 Annual Work Programme for the Implementation of ‘Erasmus+’: The Union Programme for Education, Training, Youth and Sport. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. (2017). “ERASMUS+ the EU Programme for Education, Training, Youth and Sport (2014-2020).” Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/greece/sites/greece/files/20170228_erasmus-plus-factsheet_en_1.pdf

- European Commission. 2017a. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: School Development and Excellent Teaching for a Great Start in Life. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2017b. Letter from the European Commission to the President of the Bundesrat of Germany, 20. 12.2017. Brussels: European Commission.

- Foucault, Michel. 1980. Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Galli, Carlo. 2010. “Political Spaces and Global War.” Translated by Elisabeth Fay. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gorur, R. 2017. “Towards Productive Critique of Large-scale Comparisons in Education.” Critical Studies in Education 58 (3): 1–15. doi:10.1080/17508487.2017.1327876.

- Gorur, Radhika, Sam Sellar and Gita Steiner-Khamsi, eds. 2019. World Yearbook of Education 2019: Comparative Methodology in the Era of Big Data and Global Networks. Oxon: Routledge.

- Grommé, F. and E. Ruppert. 2019. “Population Geometries of Europe: The Topologies of Data Cubes and Grids.” Science Technology and Human Values 1–27. doi:10.1177/0162243919835302.

- Gulson, K. N., and S. Sellar. 2019. “Emerging Data Infrastructures and the New Topologies of Education Policy.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (2): 350–366. doi:10.1177/0263775818813144.

- Hartong, S., and N. Piattoeva. 2021. “Contextualizing the Datafication of Schooling–a Comparative Discussion of Germany and Russia.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1080/17508487.2019.1618887.

- Jarke, J., and A. Breiter. 2019. “Editorial: The Datafication of Education.” Learning, Media and Technology 44 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/17439884.2019.1573833.

- Jensen, C. B., and A. Morita. 2017. “Introduction: Infrastructures as Ontological Experiments.” Ethnos 82 (4): 615–626. doi:10.1080/00141844.2015.1107607.

- Kornberger, M., D. Pflueger and J. Mouritsen. 2017. “Evaluative Infrastructures: Accounting for Platform Organization.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 60: 79–95. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2017.05.002.

- Law, J. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. New York: Psychology Press.

- Lawn, M. 2013. “The rise of data in education systems: collection, visualization and use.” https://books.google.com/books?hl=nl&id=fCVwCQAAQBAJ&pgis=1

- Lawn, M. and S. Grek 2012. “Europeanizing education: Governing a new policy space.” https://books.google.com/books?hl=nl&id=IixwCQAAQBAJ&pgis=1

- Lewis, S. 2018. “PISA ‘Yet to Come’: Governing Schooling through Time, Difference and Potential.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (5): 683–697. doi:10.1080/01425692.2017.1406338.

- Lewis, S. (2020a). “PISA, Policy and the OECD: Respatialising Global Educational Governance through PISA for Schools.” Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8285-1

- Lewis, S. 2020b. “Providing a Platform for “What Works”: Platform-based Governance and the Reshaping of Teacher Learning through the OECD’s PISA4U.” Comparative Education 56 (4): 484–502. doi:10.4324/9780203802243.

- Lewis, S. 2020c. “The Turn Towards Policy Mobilities and the Theoretical-methodological Implications for Policy Sociology.” Critical Studies in Education 1–16. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1808499.

- Lewis, S. and S. Hartong. 2021. “New Shadow Professionals and Infrastructures around the Datafied School: Topological Thinking as an Analytical Device.” European Educational Research Journal 147490412110074. doi:10.1177/14749041211007496.

- Lingard, B. 2021. “Multiple Temporalities in Critical Policy Sociology in Education.” Critical Studies in Education 1–16. doi:10.1080/17508487.2021.1895856.

- Lury, C., L. Parisi, and T. Terranova. 2012. “Introduction : The Becoming Topological of Culture.” Theory, Culture & Society 29 (4/5): 3–35. doi:10.1177/0263276412454552.

- Lury, C., M. Tironi and R. Bernasconi. 2020. “The Social Life of Methods as Epistemic Objects: Interview with Celia Lury.” Revista Diseña 16: 32–55. doi:10.7764/disena.16.32-55.

- Lury, Celia. 2012. “Going Live: Towards an Amphibious Sociology.” The Sociological Review 60 (1_suppl): 184–197. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02123.x.

- Marres, Noortje. 2012. “The Redistribution of Methods: On Intervention in Digital Social Research, Broadly Conceived.” The Sociological Review 60 (1_suppl): 139–165. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02121.x.

- Martin, L., and A. J. Secor. 2014. “Towards a Post-mathematical Topology.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (3): 420–438. doi:10.1177/0309132513508209.

- Michael, Mike. 2012. “De-signing the Object of Sociology: Toward an ‘Idiotic’ Methodology.” The Sociological Review 60 (1_suppl): 166–183. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02122.x.

- Mol, A. 2002. The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice.

- Nóvoa, A. 2013. “The Blindness of Europe: New Fabrications in the European Educational Space.” Sisyphus - Journal of Education 1: 104–123. http://revistas.rcaap.pt/sisyphus/article/view/2832

- Opitz, Sven, and Ute Tellmann. 2015. “Europe as Infrastructure: Networking the Operative Community.” South Atlantic Quarterly 114 (1): 171–190. doi:10.1215/00382876-2831356.

- Peck, J., and N. Theodore. 2015. Fast Policy: Experimental Statecraft at the Thresholds of Neoliberalism. University of Minnesota Press.

- Peshkin, Alan. 2000. “The Nature of Interpretation in Qualitative Research.” Educational Researcher 29 (9): 5–9. doi:10.3102/0013189X029009005.

- Prince, R. 2017. Local or global policy? Thinking about policy mobility with assemblage and topology. Area, 49 (3): 335–341

- Piattoeva, Nelli, and Antti Saari. 2020. “Rubbing against Data Infrastructure(s): Methodological Explorations on Working With(in) the Impossibility of Exteriority.” Journal of Education Policy 1–21. doi:10.1080/02680939.2020.1753814.

- Ratner, H. 2019. “Topologies of Organization: Space in Continuous Deformation.” Organization Studies 1–18. doi:10.1177/0170840619874464.

- Romito, Marco, Catarina Gonçalves and De Feo Antonietta. 2020. “Digital Devices in the Governing of the European Education Space: The Case of SORPRENDO Software for Career Guidance.” European Educational Research Journal 19 (3): 204–224. doi:10.1177/1474904118822944.

- Ruppert, Evelyn, Martin Law, and Mike Savage. 2013. “Reassembling Social Science Methods: The Challenge of Digitial Devices.” Theory, Culture & Society 30 (4): 22–46. doi:10.1177/0263276413484941.

- Savvides, Nicola. 2006. “Developing a European identity: A case study of the European School at Culham.” Comparative Education 42 (1): 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060500515801.

- Salajan, Florin D. 2019. “Building a Policy Space via Mainstreaming ICT in European Education: The European Digital Education Area (Re)visited.” European Journal of Education 54 (4): 591–604. doi:10.1111/ejed.12362.

- Savage, Mike. 2013. “The ‘Social Life of Methods’: A Critical Introduction.” Theory, Culture & Society 30 (4): 3–21. doi:10.1177/0263276413486160.

- Savage, Mike, and Roger Burrows. 2007. “The Coming Crisis of Empirical Sociology.” Sociology 41 (5): 885–899. doi:10.1177/0038038507080443.

- Suchman, L. 2012. “Configuration”. In Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social, edited by C. Lury and N. Wakeford, 48–60.doi:10.3139/9783446437845.016.

- Thrift, Nigel. 2005. Knowing Capitalism. London: Sage.

- Tahirsylaj, Armend. 2021. “What kind of citizens? Constructing ‘Young Europeans’ through loud borrowing in curriculum policy-making in Kosovo.“ Comparative Education. 57 (1): 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1845066.

- Uprichard, Emma. 2012. “Being Stuck in (Live) Time: The Sticky Sociological Imagination.” The Sociological Review 60 (1_suppl): 124–138. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02120.x.

- van de Oudeweetering, Karmijn, and Mathias Decuypere. In Press. “Navigating European education in times of crisis? An analysis of socio-technical architectures and user interfaces of online learning initiatives.” European Educational Research Journal.

- Van Dijck, J., T. Poell, and M. De Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford University Press.

- Vanden Broeck, P. 2020. “The Problem of the Present: On Simultaneity, Synchronisation and Transnational Education Projects.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 52 (6): 664–675. doi:10.1080/00131857.2019.1707662.

- Williamson, B. 2016. “Digital Education Governance: Data Visualization, Predictive Analytics, and ‘Real-time’ Policy Instruments.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (2): 123–141. doi:10.1080/02680939.2015.1035758.

- Williamson, B. 2020. “Making Markets through Digital Platforms: Pearson, Edu-business, and the (E)valuation of Higher Education.” Critical Studies in Education 1–17. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1737556.