ABSTRACT

Education governance networks are increasingly common and very diverse. In a strategic case study, we apply a new social network analysis method to evaluate the sustainability of a public-private education governance network. We examine the balance of satisfaction across public and private sectors and the network’s fairness in terms of whether actor groups’ investments in the network are proportional to their influence. We find that this established, long-term network is not entirely balanced but is fair, and argue that the fairness contributes to its sustainability. This fairness might arise due to the existing intermediaries in the network. Intermediaries play important roles in many networks, operating between other actors to build capacity and facilitate cooperation. We investigate how intermediaries operate, especially in networks that connect the public and private sectors. We find that intermediaries’ roles differ according to sector. Public-sector intermediaries perform a direction function, complementing the effort and interconnectedness of individual actors. In contrast, private-sector intermediaries play a representing role, substituting for individual actors’ effort and interconnectedness. These different roles of the public- and private-sector intermediaries contribute to the sustainability of the network.

Introduction

Education governance brings together a wide variety of actors at multiple governance levels, in various roles, and across the public and private sectors. Intermediaries are an increasingly important part of these networks, facilitating policy implementation (Honig Citation2004), providing technical assistance or resources (Reckhow and Snyder Citation2014), and promoting dialogue (Williamson Citation2014).

As education networks become more complex, intermediaries also play an important role in increasingly common public-private partnerships (Piopiunik and Ryan Citation2012; Hoeckel and Schwartz Citation2010). Empirical evidence shows the increasing presence of intermediaries in education governance networks (Ball and Junemann Citation2012; Ball Citation2008) and initial theory articulates how intermediaries operate for specific purposes like policy implementation (Honig Citation2004).

This article addresses two research questions. First, we consider the sustainability of education governance networks – specifically those with public-private partnership. We focus on the balance of satisfaction across sectors and a novel metric for whether actors’ investments in the network are proportional to their importance therein. We find that the network in this case is not completely balanced across the public and private sectors – private-public relations are less satisfied – but fair across actor groups such that actor groups’ investments in the network are proportional to their importance in the network. This network is a well-established and highly functional governance network, and this kind of analysis could be a useful approach to building sustainability for other governance networks, especially those linking the public and private sectors.

Second, we examine how public- and private-sector intermediaries operate in a large and well-established governance network that connects the public and private sectors. We examine intermediaries’ connections to other actors and consider two possible types of intermediary activity, direction, and representation. We find that public-sector intermediaries are directors – their strong out-relations and weaker in-relations complementing public-sector micro-level actors’ participation and within-group cooperation – while private-sector intermediaries are representatives – their reciprocal in- and out-relations substituting for more intense participation or cooperation from private-sector micro-level actors. This indicates that intermediaries in public-private partnerships or other public-private governance networks need to play different roles to successfully support the engagement of actors from each sector. The model used in this case – separate intermediaries for the public and private sectors – is a strategy that enables intermediaries to serve each group’s needs.

In the following, we provide a brief literature review about public-private partnerships and potentials solutions to the principle-agent problematic within such partnerships. A theory section follows, in which we derive our hypotheses. Then, we present our results followed by a discussion and conclusion.

Literature review

Governance networks are an application of network science that draws upon social network analysis and systems theory as well as complexity theory (Koliba et al. Citation2017). Governance networks are leadership processes that solve complex problems through the combination of multiple actors from different sectors and backgrounds (Ulibarri and Scott Citation2017; Ball and Junemann Citation2012). Governance by multiple partners including public- and private-sector actors is an increasingly common approach to both providing and monitoring governance and services – especially in the education sector (Tao and Liu Citation2022; Blackmore Citation2011).

In the education sector, network governance contrasts against a traditional hierarchical model of education governance that focuses on schools and school-related public-sector actors (Simkins Citation1994). A heterarchy (Ball and Junemann Citation2012) is a dynamic that falls between a hierarchy and a fully diffused network, in which policy processes proceed along horizontal and vertical links. Heterarchies include institutions from the public and private sectors and operate through institutionalized negotiations that lead to coordinated action (Jessop Citation1998). Governments become facilitators and co-creators in heterarchies, working alongside other actors (Hogan Citation2021). Taking a network approach to studying governance highlights the many non-state actors involved in education governance – including civil society, donors, corporations, private providers, and others – who may work together or at least alongside one another to achieve education-related goals (Menashy Citation2016).

The presence of both public- and private-sector actors in education governance networks is the subject of both praise and criticism. Public-private partnership covers a wide array of activities in and outside of education governance, including ‘arrangements between public and private actors for the delivery of goods, services, and/or facilities’ (Verger and Moschetti Citation2017) p.2). Public-private partnership can be an important resource and engagement tool in education governance (Lingard and Sellar Citation2013; Ball Citation2016). In education systems, these partnerships should expand resources, flexibility, and effectiveness (Robertson, Mundy, and Verger Citation2012).

However, public-private partnership is also widely criticized for a variety of reasons. The collaborative view of public-private partnership where both sides are equals working towards a common goal they could not achieve alone is characteristic of the New Public Governance approach to partnership (Velotti, Botti, and Vesci Citation2012). However, collaboration may be more accurately characterized as a working method, not a goal or primary function of public-private partnership (Wang et al. Citation2018). In contrast, the New Public Management approach frames partnership as a form of privatization organized through contracts between public and private actors, which are subject to principal-agent problems (Velotti, Botti, and Vesci Citation2012; Wang et al. Citation2018).

Empirical evidence highlights the consequences of this principal-agent problem in the imbalances and asymmetries that appear alongside the benefits of public-private partnership. For example (de Koning Citation2018), finds equity and accountability concerns when legal frameworks are inadequate to govern a more complex set of actors. In addition, the primary beneficiary of public-private partnership may be businesses rather than students or schools (Steiner-Khamsi and Draxler Citation2018).

Multiple solutions are proposed in the literature to solve the principal-agent problems that arise from public-private partnership in education governance networks. In general, the goal is to increase accountability and transparency across actors (Onyoin and Bovis Citation2022; Willems Citation2014). One strategy is increasing brokerage in the network. Brokerage is the process of facilitating knowledge transfer and resource access (Obstfeld, Borgatti, and Davis Citation2014). Alternatively, effective intermediaries may be able to bring about effective change and innovation (Datnow and Honig Citation2008).

Although seemingly similar, brokerage is different from intermediation. Previous research aligned brokerage with intermediation through the structural holes model in which a broker connects otherwise completely unconnected actors (Burt Citation1992, Citation2005). In contrast (Galey-Horn et al. Citation2020), propose a chain model of brokerage that connects actors around an idea even if they are already connected by other ideas, making brokers different from intermediaries. They find that brokers are very often not intermediary actors, rather brokerage is a process carried out by individual actors regardless of network position.

In education policy networks (Honig Citation2004), defines intermediaries as actors that ‘occupy the space in between at least two other parties’ (p. 67). Intermediaries play a variety of roles in education policy networks. Often, they manage information, enhance schools’ and districts’ resources, facilitate dialogue, and disseminate information and change throughout systems (Honig and Hatch Citation2004). (Kolleck Citation2016) finds that NGOs and government actors have relatively more influence and have more diverse connections in a German education governance network than school-level actors (Kabir Citation2021). Finds that networked governance in Bangladesh is both enabled and constrained by structural factors, and that intermediary organizations can play a very large role in the introduction and dissemination of policy ideas.

The empirical literature on education policy intermediaries is dominated by theory-building case studies (i.e (Honig Citation2004). of intermediaries – often nonprofits (Smylie and Corcoran Citation2009), NGOs (Kolleck Citation2016), or philanthropies (Reckhow and Snyder Citation2014). These actors are observed playing connecting, coordinating, facilitating, and leadership roles (Scott and Jabbar Citation2014). Propose a dual hub-and-spoke model for intermediaries’ activity in education reforms, arguing that philanthropic organizations act as both a funding hub and an implementing spoke along with other intermediaries (DeBray et al. Citation2019). apply the model to Atlanta school reform, finding intermediaries serving connection and cooperation-facilitation roles (Rowe Citation2021). also examines philanthropic intermediaries, finding that the government is the central hub while intermediaries act as spokes to connect other network actors to the hub.

Methodologically, much of the empirical literature on education policy networks is engaged with describing the shift toward networks and portraying the networks themselves (i.e (Ball Citation2008; Goodwin Citation2009; Lingard and Sellar Citation2013; Junemann, Ball, and Santori Citation2016). Much – though far from all – education governance network research has historically taken a network ethnography approach (Ball Citation2016; Rowe Citation2021), making it difficult to analyze the nature, strength, and quality of network bonds when the main work is to identify and link the actors in the first place. Some studies have exploited innovative observational methods (Galey-Horn et al. Citation2020), social media (Schuster, Jörgens, and Kolleck Citation2021), and known networks (Ferrare, Carter-Stone, and Galey-Horn Citation2021) to shorten or skip the time-consuming process of identifying members and focus on relations rather than structure. These studies are able to focus on power and relations.

The literature identifies a need for new approaches and methods that enable deeper analysis of networks and theory testing (Junemann, Ball, and Santori Citation2016). The presence of a network is not the same as network governance, with power to set direction and influence behavior the key differentiating factor (Parker Citation2007; Christopoulos Citation2008). Therefore, describing governance networks is probably not sufficient for understanding them: analyzing and understanding the power within networks may be necessary to understand them (Goodwin Citation2009). Goodwin further argues that such analysis might uncover asymmetries in the power held by different actors and actor groups.

Theory

Power and network sustainability

If power is unbalanced across actors from the public and private sectors in the same network, there is a risk that this creates a sector-based imbalance in actors’ experiences of network participation. This could put the sustainability of the network at risk.

Our conceptualization of power in education governance networks aligns with the research tradition on policy networks (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2012). This tradition, originating from political science, is focused on ‘decision making and effects, closure and power relations on issue and agenda setting’ (ibid, p.3). This concept of power is about the actors involved in making decisions and the nature of their power relations (Kapucu and Hu Citation2020). This kind of within-network power originates from the ability to coerce or reward, from formal responsibilities, from acceptance, from expertise, or from control over information (French, Raven, and Cartwright Citation1959).

(Tao and Liu Citation2022) summarize two theorized power structures in network governance: symmetric and asymmetric. In the symmetric model, actors share power relatively equally, while governments tend to dominate in the asymmetric model. However, their findings indicate that actors may have symmetric relations with some partners and dominate other members of the same group. Therefore, it may be more complex than simply asymmetric or symmetric.

It is not obvious how power is distributed in a governance network. For example (Capano, Howlett, and Ramesh Citation2015), highlight the ‘shadow of hierarchy’ that enables governments to exert power over other network actors regardless of position or relations in the network. Contrarily, the government in network governance may have less power than a hierarchical government if it has been ‘hollowed out’ (Tao Citation2022) and outsources key functions to non-government actors (Bach and Ruffing Citation2012). Network governance by itself does not imply a certain balance of power, and power relations within the network define its character.

Assessing symmetry is challenging. We do not propose to find a solution or answer the question once and for all, but we are willing to make an effort in that direction. Therefore, we take on the issue of attempting to assess power symmetry in the network.

RQ1:

How could we approach evaluating the sustainability of education governance networks?

We can observe power asymmetry or symmetry in two ways. First, we observe actors’ perceptions of the network across the public and private sectors. If the one sector dominates the other, then we would expect to see that imbalance in actors’ perceptions of the network.

Second (Elliott and Golub Citation2019), develop a method for defining and assessing the ‘fairness’ in a network that produces a public good. Their definition of fairness is that actors’ investments in the network is proportional to their influence in the network (e.g. when employers are asked to contribute resources, they also have power). If the network is either unbalanced in terms of participants’ experiences or unfair in terms of participants’ investment and influence, the sustainability of the network is at risk. We expect that a stable and established network will be both balanced and fair.

H1A:

A successful and sustainable public-private governance network is balanced across sectors: the public and private sectors are similarly satisfied with the network.

H1B:

A successful and sustainable governance network is fair: actor groups’ investments are proportional to their influence in the network.

The role of intermediaries

Intermediaries are a diverse group of organizations and actors primarily defined by their in-betweenness (i.e (Moss Citation2009), inter-organizational networks, and inter-discursive connections (Williamson Citation2014). We examine how intermediaries mediate public-private partnership from positions in the public or private sectors.

RQ2:

How do public- and private-sector intermediaries operate in education governance networks?

There is already evidence of differentiated intermediary functions in the literature. For example (Tao Citation2022), and (Tao and Liu Citation2022) look at education policy networks with two intermediary types: local governments and ‘third-party actors’ from outside government. They find that local governments behave in three ways – dominator, accommodator, and facilitator. ‘third-party actors’ also behave in three ways, but they are different. These intermediaries can be representatives of the government, leaders, or partners. Each intermediary has multiple behavior patterns, and these patterns vary across the public and private sectors.

Returning to the definition of power as relations and position in the network (Kapucu and Hu Citation2020), we argue that relations between intermediaries and micro-level actors take on different patterns depending on whether the intermediary is based in the public or private sector. Like (Honig Citation2004,) we differentiate intermediaries according to their funding sources in either the public or private sector. The private and public sectors have different norms and needs. Intermediaries in the public sector can rely on coercive, reward, and legitimate power, while those with private-sector funding must rely on the referent, expert, and informational sources of power (French, Raven, and Cartwright Citation1959).

The public sector is typically structured by regulations and other formal power structures. The actors are given, as are hierarchies. As part of this structure, we expect public-sector intermediaries to act as directing intermediaries. As shown in , directing intermediaries primarily relate down to micro-level actors, facilitating coordinated action based on the outcome of institutionalized negotiations. Directing intermediaries have strong out-relations to micro-level actors and relatively weaker (if any) in-relations from micro-level actors. The macro-level also relates down to the directing intermediary, so we expect a strong in-relation from that level and a weaker (if any) out-relation from the intermediary to the macro-level.

Figure 1. Directing and representing intermediaries.

H2A:

Public-sector intermediaries are directing intermediaries. This is characterized by strong out-relations and weaker in-relations to micro-level actors, and strong in-relations but weaker out-relations to macro-level actors.

The private sector is typically more competitive, and intermediaries with private-sector funding need to add value to justify their existence. They may be more like service providers, and their existence is threatened if they do not satisfy the micro-level actors they work with. As a concrete example, evidence shows that private-sector actors are cost-sensitive when participating in education governance (Muehlemann and Wolter Citation2020). Therefore, private sector intermediaries working with firms need to lower participation costs or the firms will either work with a different intermediary or opt out entirely. To do this, private-sector intermediaries need to understand the needs of micro-level actors and transmit those to the macro-level.

Thus, we expect private-sector intermediaries to act as representing intermediaries. Representing intermediaries have reciprocal relations with micro-level and macro-level actors (see ) because they are transmitters of for example information. shows the difference in a highly simplified network where A is the macro-level actor, B is the intermediary, and C represents the individual actors.

H2B:

Private-sector intermediaries are representing intermediaries. This is characterized by reciprocal relations with micro-level actors and macro-level actors.

Data

Testing our hypotheses requires an education governance network with a large array of individual actors that can be simplified into actor types or groups. We also require a stable network that includes public-private partnership. For this study, we chose a context where the public-private partnership is not only well established but is formalized in the education program’s legal framework, making the partnership explicit. This creates a large but still relatively simple network with clearly defined roles, making it a somewhat clearer empirical setting.

Specifically, we employ a strategic case study of the largest upper-secondary education program in Switzerland, dual vocational education and training (VET). The program enrolled 60% of the 15–19-year-old cohort in 2017.Footnote1 This case has the advantage of a clearly defined set of actors in the law (VPET Act Citation2002) that includes formalized public-private partnership. Governance-network actors in that system fall into five main groups: the federal government, regional governments (Cantons in the Swiss context), employers’ associations, apprentice training firms, and schools. Although there are 250 different occupational curricula within the dual VET program, a representative from each of those actor groups is involved in the governance and delivery of every student’s education.

Context in Switzerland

We use the Swiss VET case because it allows us to look at a predefined network where actors’ roles, power, and responsibilities are all well defined by law and well established over time. This gives us clear intermediaries with defined tasks of working between actor groups and facilitating coordination and cooperation. It also means that the private-sector intermediaries are required and authorized to be part of collaborative decision-making, just like their public-sector counterparts in the regional governments are. This mandate of the private-sector intermediary and the private-sector micro-level actors is not always the case in education governance networks, and reduces the possibility that differences between intermediary types are driven by different levels of security in their place within the network. In addition, the intermediaries here do not provide education and training directly, so the dual role of providing schooling and acting in governance is not present.

There are five main actor groups involved in the governance of VET in Switzerland: the federal government, employers’ associations, cantonal governments, schools, and firms. The federal government is responsible for the overall steering of the system via the (VPET Act Citation2002,) which sets out the basic principles, rules, and responsibilities of all actors. Each occupational curriculum is set at the federal level in a process facilitated by the federal government but led by employers’ associations.

Employers’ associations represent their members – usually firms in a given industry or with employees in a given occupation – during the definition of curriculum content and standards and argue for their interests in the design, delivery, and updating of VET. These associations also participate in other advocacy activities and seek to lighten the load for firms through a variety of activities including creating training plans from the competencies defined in the curriculum, developing educational materials, advertising the occupation or industry to young people interested in apprenticeships, and even providing materials or information to the schools attended by their employers’ apprentices.

Cantonal or regional governments are responsible for implementing VET as defined by the federal government and each occupation’s curriculum. These regional governments oversee schools and ensure the quality of training provided by firms. Regional governments are also responsible for support services like career guidance and counseling.

Schools in the Swiss VET program provide education covering the academic and general competencies in each occupational curriculum. These include languages, math, social subjects, and theory (e.g. economics for bankers, physics for electricians) as defined by the occupational curriculum. Schools do not offer occupation-specific practical training.

Training firms hire students as apprentices and commit to providing the occupation-specific and practical competencies outlined in the curriculum. Students are in the firm three or four days each week and work productively alongside experienced workers according to the training plan devised by the firm or – more often – provided by the employers’ association. Throughout the three- or four-year program and in the final exam, firms are held responsible for their apprentices’ practical competencies. The regional government has the power to revoke a firm’s training license if apprentices’ learning is insufficient or if poor conditions are reported.

We consider firms and employers’ associations private-sector actors. Although some firms are in the public sector – our university, for example, trains apprentices in a number of occupations as a fully public institution – their training-related behavior is motivated by a need for skilled workers and the returns they earn on their training investments (Muehlemann and Wolter Citation2020). Employers’ associations, though they work with the government and are charged with leading the curriculum development process, are private organizations and not part of the government in any way. We categorize the federal government, regional governments, and schools in the public sector.

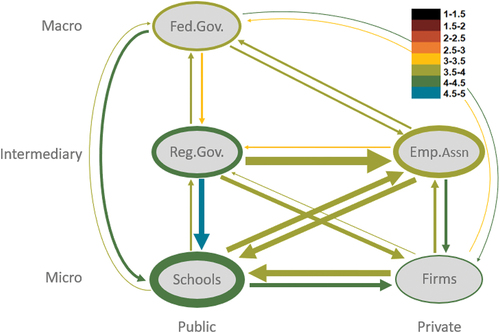

Two actors are intermediaries: employers’ associations and regional governments. Employers’ associations mainly operate between the federal government and individual firms, aggregating firms’ labor and skills demand up to the curriculum development process, developing materials to support their constituent firms in training apprentices, and facilitating communication between firms and the government. Because of their position between firms and the government, employers’ associations intermediate a public-private partnership. In contrast, regional governments operate mainly within the public sector, operating primarily between the federal government and schools. Regional governments facilitate communication between governance levels, represent their regional schools, and interpret federal directives (Hamann and Lane Citation2004). summarizes the roles and levels of actor groups in the network.

Figure 2. Blank network showing actor groups by level and sector.

(Honig Citation2004) describes five dimensions on which intermediaries vary: level of government, composition, location, scope, and funding sources. We use these dimensions to provide general descriptions of each intermediary. Regional governments operate at the regional level, while employers’ associations work at both the regional and national levels. Regional governments are composed of dedicated staff, with employers’ associations having some staff that also works at member companies. Both are located as external intermediaries. The scope of a regional government is one canton, including regional governance, oversight of all schools, and training firms’ quality assurance and certification to train. Employers’ associations work with the companies in a particular industry either nationally or in a specific region. Both regional governments and employers’ associations work with the federal government to define occupational curriculum content and standards. While regional governments are publicly funded, employers’ associations are mainly privately funded by member firms.

Sample and survey

We use data from a 2019 survey of key actors in the Swiss VET system (Renold, Caves, and Oswald-Egg Citation2019). The survey went out in two waves. The first wave sampled 678 individuals in the federal government, regional governments, employers’ associations, and schools, of whom 536 responded (79.1% response rate). The second wave went out to 28,819 firmsFootnote2 that train apprentices, of whom 1,593 responded (5.5% response rate). Our response rate for four out of the five actor groups is very high, but the firm sample has a much lower rate. Still, the absolute number of 1,593 respondents is high and, when tested, representative of Swiss regions.Footnote3 All economic sectors are represented, with the greatest responses from the construction, health and social work, and manufacturing sectors. shows the total respondents by actor group in the dataset.

Table 1. Respondents by actor group.

We asked each respondent three questions related to the network. Questions were asked originally in German or French, with English translations provided here.

Which actor group does your institution belong to? (Respondents selected all that apply from the list of five groups provided above)

How much do you work directly with [each actor group]? (Five-point Likert scale from 1-never to 5-very often for each actor group)

In your opinion, how well does the cooperation work with [each actor group]? (Five-point Likert scale from 1-very negative to 5-very positive)

Therefore, our data is collected at the actor-group level – we do not ask about individual actors and aggregate the network from there. Actors in this network tend to have relations with multiple actor groups including their own group. In addition, a small number of respondents represent two groups – for example a business owner who is also active in the employer’s association in her industry. In total, the data captures 4,985 relations.

Method

Because we are interested in actor-group-level interactions and our data is collected in terms of actor groups not individual actors, all analyses reflect actor groups (e.g. schools or firms) not individuals (e.g. one school). We summarize the network by averaging observables within every actor group adjacency pair (e.g. schools to firms) for each of the 25 possible actor-group-level combinations.

This is a directed network, so relations from A to B are different from the relations from B to A. To prevent certain respondents from being over-represented, we calculate the incidence of each combination as the percentage of unique originating actors who have a relation to the receiving actor. We multiply relations’ incidence and reported intensity to generate each pair’s relation load, which falls on a 0-to-5 scale.

In our network, we observe variation in the number of members in each actor group, so the theoretical maximum number of connections also varies by actor group. Therefore, we weight network to one node per actor group, and use the adjacency among pairs – how often they are connected relative to the possible connections – to assess centrality (Opsahl, Agneessens, and Skvoretz Citation2010). We use this approach to node centrality because it combines the strength of the tie and the number of ties. Given our actor-group-level approach, this lets us maximize the potential of our data.

H1A and H1B take steps toward understanding the balance and fairness of public-private partnership and the network in general. One way to investigate the balance of a network across groups is to block the adjacency matrix into groups – the public and private sectors in this case – and compare key indicators across blocks. To do this, we take the public-sector actors (federal government, regional governments, schools) and the private-sector actors (employers’ associations, firms) and treat them as actor groups. We construct a two-by-two adjacency matrix that shows satisfaction for each sector as the originating and receiving actor. For H1A, a balanced network, we expect that satisfaction is not significantly different across public- and private-sector blocks.

For H1B, one measure of fair cooperation is a Lindahl outcome, or an economic equilibrium representing fair cooperation in a game (Buchholz and Peters Citation2007). Education governance networks produce a public good (Allouch and King Citation2018; Talamàs and Tamuz Citation2017), and (Elliott and Golub Citation2019) provide a method for identifying Lindahl outcomes in public-goods networks. The approach uses eigenvalue centrality, which assesses not just actors’ connectedness but also the connectedness of their connections (Hanneman and Riddle Citation2005). Following (Elliott and Golub Citation2019) we regress actors’ levels of investment on their eigenvalue centralities. For a fair network, we expect that no actor’s investment will be significantly different from its eigenvalue centrality.

H2A and H2B assert that intermediaries can take a directing or representing role. We compare relation loads of inward and outward relations for these hypotheses. Relation loads are the product of the relation’s intensity as rated by actors who report the relationship multiplied by the share of actors in the originating actor group who report having the specific relation. Directing intermediaries – which we expect to find in the public sector’s regional governments – should have high out-degree relation loads and low in-degree relation loads with micro-level actors. Representing intermediaries – which we expect to find in the private sector’s employers’ associations – should have reciprocal relations with relatively equivalent out- and in-degree relation loads. Both intermediary types should have equivalent out- and in-degree relation loads with the macro-level federal government.

summarizes our data and analytical approach for each research question and hypothesis. We use the igraph package in R for all analyses (Csardi and Nepusz Citation2006).

Table 2. Data and method for each research question and hypothesis.

Results

is an adjacency matrix showing the frequency with which unique members of each originating actor group partner with members of each receiving actor group. The table displays percentages for each pair – including within-group loops – ranging from 17% (firms to federal government) to 84% (firms to schools). Row means display actors’ adjacency as a receiving actor, and column means show adjacency as an originating actor. The overall mean shown in the bottom row of is each actor’s centrality. Both intermediaries have high centrality, which makes sense given their roles. Schools also have very high centrality.

Table 3. Adjacency matrix showing the percent of adjacency among pairs.

gives a graphical overview of the overall network. Colored lines represent a relation flowing in the direction shown by the arrows. Within-group relations are shown by the outlines around each actor group. Line thickness shows relation load – the product of average intensity and incidence for relations between the given actor groups – and colors show satisfaction on the one-to-five-point scale shown in the legend. Actors on the left side belong to the public sector and those on the right belong to the private sector. Vertical placement shows levels, with the macro level (federal government) at the top, the intermediaries in the middle, and micro-level actors at the bottom. in the Appendix shows the full numeric summary.

Figure 3. Actor-level network with relation strength and satisfaction.

The network is generally satisfied. The most satisfied relation – in blue – is from regional governments to schools. All the yellow-colored least-satisfied relations connect to the federal and regional governments, and those relations are all very weak. All relations are above the three-point midpoint of the five-point Likert scale. Firms are the most well-liked actor (satisfaction in relations to firms averages 4.07 out of 5 points), followed closely by schools (3.99) and employer associations (3.84), then regional and federal governments (3.56 and 3.52, respectively).

Network sustainability

We expect from H1A that this long-term stable network should be balanced. Specifically, we expect to find similar relation load and satisfaction across the public and private sectors. shows a blocked adjacency matrix for the public and private sectors. The top-left and bottom-right quadrants represent within-public- and within-private-sector partnerships, respectively. The bottom-left and top-right quadrants represent public-private partnership.

Table 4. Blocked matrix of satisfaction and relation load by sector.

We find that the range of variation in satisfaction is small – even in the public-private and private-public quadrants. However, private-public relations are significantly less satisfied than all other relations based on Welch’s t-test (p < 0.01). No other relation’s satisfaction is significantly different from another’s. Although public- and private-sector actors seem to have consistent and generally positive experiences, we do find one difference across sectors. Therefore, it is not clear that this network is balanced and we do not find full support for H1A.

According to H1B, a sustainable network like this one should be fair. Specifically, we expect to find that actors’ eigenvector centralities are not significantly different from their investments. shows eigenvector centrality and investment for each actor, where investment is the average of relation load across all pairs involving each. We regress investment on eigenvalues using simple linear regression and show residuals in the bottom row of the table.

Table 5. Table of actors’ eigenvalues, investment in the network, and residuals.

We find that no actor’s residual is significant, meaning investment correlates strongly to eigenvalues. This is one indication that actors’ investment is proportional to their eigenvector centrality. This result is robust when we drop loops (within-actor relations) from the adjacency matrix and run the regression again, and when we include all relations – not just out-directed relations – in the investment value. Actors’ investments in the network are proportional to their eigenvalues, so the network appears to be fair by this metric and we find evidence supporting H1B.

Role of intermediaries

H2A asserts that regional governments should be directing intermediaries, with high out-directed relation load and lower in-directed relation load connecting them to schools and firms. They should have equivalent relation loads with the federal government. Because the regional governments play a directing role, we also expect to see high within-group relation load on the part of schools – the intermediary is not bringing the schools together, so we expect them to interact on their own. Finally, we expect weak relations between schools and the federal government.

Based on (and in the Appendix) we find strong support for H2A. Relation loads from regional governments to schools and firms are approximately double the relation loads from schools and firms back to regional governments (RegGov to School is 2.50, School to RegGov is 1.54; RegGov to Firm is 2.10, Firm to RegGov is 0.97). We also see much higher satisfaction in the relations from the regional governments to schools and firms (4.56 and 4, respectively) than we do from schools and firms back to the regional governments (2.75 and 2.42, respectively). The relations between the regional and federal governments are very balanced, both in terms of relation load (RegGov to FedGov is 1.59, FedGov to RegGov is 1.44) and satisfaction (2.79 and 2.6, respectively).

As a secondary element of the hypothesis, we expected to see that schools maintain strong within-group relations because the intermediary is not facilitating that contact. Indeed, schools have very high and happy within-group relations, with a relationship load of 3.17 (the highest we observe in the entire network and closest to the theoretical maximum of 5.00) and a satisfaction rating of 4.47 on average. The one area where H2A is not completely supported is our final expectation – that we would find weak relations between schools and the federal government. Schools’ relation to the federal government is indeed weak and somewhat satisfied (relation load 1.06, satisfaction 3.51), but the relation from the federal government to the schools is stronger than expected (1.71) and satisfied (4.14).

H2B argues that employers’ associations – though intermediaries in the same network – play a different role and act as representing intermediaries. We expect them to have reciprocal relations with both the schools and firms and with the federal government. We also do not expect the firms to have high relation loads connecting them to the federal government or within-group because the employer association substitutes for these relations as a representative. When firms choose to have within-group relations, we would expect them to be satisfied.

Again referring to and , we find strong support for H1B. Employers’ associations generally have reciprocal and collegial relations with micro-level actors and with the federal government. Employers’ associations have very similar relation loads to and from firms (EmpAssn to Firm is 1.78, Firm to EmpAssn is 1.73), to and from schools (EmpAssn to School is 2.46, School to EmpAssn is 2.56), and to and from the federal government (EmpAssn to FedGov is 1.43, FedGov to EmpAssn is 1.50). Given the wide range of possible relation loads, it is striking how closely these all mirror each other. Relations are also reciprocal in moderate satisfaction: employers’ associations relations to the federal government are slightly satisfied (EmpAssn to FedGov is 3.58, FedGov to EmpAssn is 3.67), to firms are slightly more satisfied (EmpAssn to Firm is 4.21, Firm to EmpAssn is 3.82), and to schools are similar (EmpAssn to School is 3.98, School to EmpAssn is 3.88).

Our secondary expectations for private-sector representing intermediaries is that firms do not have strong within-group relations but they are satisfied when they exist. Evidence supports this, with a within-group relation load of 1.22 and satisfaction of 3.95. We also expect weak relations between the firms and federal government, which we find in the data (FedGov to Firms 0.93 load, 4.36 satisfaction; Firms to FedGov 0.33 load, 3.45 satisfaction).

Discussion

In a public-private policy network like this one, we might expect to find issues like asymmetric power structures (Tao and Liu Citation2022), shadow hierarchies (Capano, Howlett, and Ramesh Citation2015), or a powerless government that has outsourced its key functions (Bach and Ruffing Citation2012). Any of these could undermine the sustainability of the network. We find that the network is relatively balanced in terms of actors’ satisfaction. The exception is slightly lower satisfaction in private-public relations, but very similar within-sector satisfaction levels and adequate satisfaction in public-private relations. However, satisfaction is a subjective measure and these differences may be due to different norms and expectations across sectors.

When we apply (Elliott and Golub Citation2019) approach to fairness in a public-private network, we find that each actor’s investment in the network is proportional to its influence therein. Each actor group has a different level of influence in the network, but we do not take that as evidence of asymmetry, hollowing out the government, or outsourcing key government functions to private-sector actors. Instead, actors’ influence in the network is correlated with the effort they put into it. We interpret this as the public-sector actors retaining formal power while private-sector actors’ power stems from their expertise and control over information (French, Raven, and Cartwright Citation1959). In other words, each actor group is performing the duties for which it has a comparative advantage.

The role of intermediaries in the network seem to be essential to the fairness and balance that make it sustainable. Like others in the literature (e.g (Tao Citation2022; Tao and Liu Citation2022), we find differentiated intermediary roles between the public and private sectors. In contrast to the existing literature, we focus on roles in the structure of the network rather than intermediaries’ behavior. Nevertheless, our findings align with a distinction between public- and private-sector intermediaries.

compares our hypothesized intermediary roles with the ones we observed in our analysis of the Swiss VET policy network. Generally speaking, these patterns match our hypotheses. In the public sector, regional governments act as directing intermediaries. Their relations to micro-level actors are generally outward-focused, with weaker inward relations from the micro-level actors. We find this pattern for both public-sector and private-sector micro-level actors, in this case both schools and firms. Unlike our hypothesis, the relation between these intermediaries and the macro-level actor is reciprocal.

Figure 4. Hypothesized (above) vs. observed (below) intermediary behavior.

In the private sector, employers’ associations act as representing intermediaries. Their relations to both the micro- and macro-levels are both reciprocal. Again, this pattern holds for both schools and firms, or both public- and private-sector micro-level actors. This also aligns with our hypothesis. We do not find a representing intermediary where all of the relations flow upward (micro-level inward to the intermediary, then from the intermediary outward to the macro-level). However, this type of representation may exist in practice and it is not clear if a network like this would also be sustainable in terms of fairness and balance.

In our analysis of the network, we observed that schools have a very high level of within-group relations, while firms have hardly any at all. This observation aligns with our theory that the roles differ across sectors based on the different norms and expectations in each sector. Private-sector actors are cost sensitive, so they need to reduce their participation costs as much as possible. If costs are too high, participating in education policy networks becomes unsustainable. Therefore, the representing intermediary substitutes for within-group cooperation by playing an aggregation and dissemination role.

In the public sector, regional governments do not substitute for relations among schools – which are strong and reciprocal – and may instead play a more complimentary role. This pattern of substitution in the private sector and complimenting in the public sector may contribute to the sustainability of the network.

Conclusions

We exploit a relatively clear-cut case of education governance with public-private partnership and intermediaries to begin developing some metrics of network sustainability and investigate the role of intermediaries.

We contribute to the literature through our application of metrics evaluating the network’s overall balance and fairness, which we argue are important for a sustainable public-private governance network. Because we have a clear-cut set of actors, we are able to go beyond network mapping. The examination of balance and fairness is an initial test of a new methodological approach from the theoretical literature and presents a potential means of assessing network sustainability.

We further contribute to the understanding of intermediaries’ roles by demonstrating that depending on the sector they serve different roles. In the public sector, we find directing intermediaries, i.e. having strong out-relations to micro-level actors and weaker in-relations. They complement within-group coordination and communication among micro-actors, who have relatively weak relations to and from the macro-level government.

In contrast, in the private sector, we find representing intermediaries, i.e. having reciprocal out- and in-relations to micro-level actors and to the macro-level actor. They act as substitutes for within-group coordination among micro-level actors and between private-sector micro-actors and the macro-level government. The key implication is that the different roles of the intermediaries depending on the sector stabilizes the network and thus contributes to the networks sustainability.

The implication of this finding is that efforts to engage employers or foster public-private partnerships should not simply use existing public-sector intermediary options to facilitate new public-private networks. An intermediary that directs actors and expects individual actors to invest complimentary effort will not be the right fit to promote sustainable private-sector engagement. Similarly, a single intermediary may not adequately meet the needs of both sides. Therefore, setting up private-sector intermediaries that complement public-sector intermediaries might stabilize public-private partnerships.

Although the evidence presented here relates to a single education program, we argue that the theoretical findings are applicable in any context with networked education governance and public-private partnership. Despite the many forms and purposes of public-private partnership, we argue that intermediaries’ role as representatives and cost-reducing substitutes for private-sector actors and directors and complementary partners for public-sector actors is a useful insight. In addition, our approaches to balance and fairness can be applied in any context and offer very interesting potential for further development. In the most complex networks, these simplifying theoretical ideas can be even more useful.

However, the metric for network fairness is the more interesting of the two for future applications. It considers each actor group individually, plotting investment against importance. We identify two areas where refinement or at least methodological care are required. First, the use of the word ‘fair’ is heavily loaded and, while this metric captures something that falls within the definition, might be too normative for contexts like this. Second, the analysis is sensitive to the operationalization of ‘investment.’ In our case, we used actors’ out-degree relation load, but other variables could be substituted in.

More sophisticated measurements of time, money, and other resources might be better suited for capturing different dimensions of ‘fairness,’ and might uncover interesting patterns in what actors value and what they consider adequate compensation for various forms of investment. This is an interesting area for future research and a very interesting way to address the questions of symmetric and asymmetric governance networks. It may be that symmetry or ‘fairness’ in terms of multiple types of investment and return – power, time, money, etc.—show different patterns related to network sustainability. It may be that all metrics need to be ‘fair’ before sustainability is possible.

The data is a cross-sectional case study. The Swiss context is useful because it is very clear-cut and our study is able to observe a very large number of actors, but further research that applies this analysis to a dynamic network may be able to observe changes over time and make causal inference.Footnote4 Our analyses focused on the relations between intermediaries and the micro- and macro-level actors. We did not explore relations between intermediaries, between micro-level actors, or within non-micro-level actor groups. Further research can also explore these as related to intermediary behavior or as applied to another question. Similarly, an analysis that can compare networks’ fair cooperation and public-private partnership with and without intermediaries will add a great deal to our descriptive analyses in those areas.

Finally, the observation and interview data provided by its authors and interviewees were self-reported, and thus cannot be guaranteed to reflect the actual collaboration process. The satisfaction data is quantitative and does not include any qualitative information about what participants find satisfactory or not, precluding additional analysis or further insight on network satisfaction. Indeed, this is the one hypothesis that is not validated in our analysis.

Despite all these limitations, this study is still a valid first step into analyzing public-private partnership with intermediaries, on which future studies may build upon.1

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Dr, Ursula Renold for her role in data collection and to Dr. Thomas Bolli for his insights and feedback. We also thank our referees and editor for their very helpful comments and suggestions, and Prof. Dr. Ulrik Brandes for his support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katherine Caves

Dr. Katherine Caves is the director of CEMETS, the international education system reform laboratory at the Chair of Education Systems at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich. Her research interests center around the policies, institutions, and infrastructure that supports strong education systems and education system improvements. She is particularly interested in systems-level reforms that make education and training more equitable, effective, and efficient. In addition, Katie studies the implementation of reforms and the success factors and barriers to that implementation. She studied at the University of California at Berkeley, and earned her PhD at the University of Zurich where her research focused on the economics of education.

Maria Esther Oswald-Egg

Dr. Maria Esther Oswald-Egg is currently a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Chair of Education Systems at ETH Zurich, Switzerland. She holds BA and MA degrees in Economics from the University of St. Gall respectively from the University of Zurich and a PhD degree from ETH Zurich. Her research interests are in economics of education and labor economics including how education systems are steered, the transition of young people into the labor market and topics around (dual) vocational education and training.

Notes

2. Some respondents in the second wave put themselves in the ‘other’ category, and while we mostly re-coded these as firms (i.e. hospitals can be training firms, but often do not consider themselves as such), some were not clear and are not included in the analysis.

3. Two regions – Geneva and Ticino – are slightly underrepresented, and Obwalden is slightly overrepresented.

4. One of the reviewers suggested the use of exponential random graph models (see for example (Lusher, Koskinen, and Robins 2013). Unfortunately, we are not able to implement the model due to our data structure. For future research we recommend to collect the data on individual to individual level and not as ours is on individual to group level.

References

- Allouch, N., & M. King 2018. Constrained public goods in networks (No. 1806). School of Economics Discussion Papers.

- Bach, T., and E. Ruffing. 2012. “Networking for Autonomy? National Agencies in European Networks.” Public Administration 91 (3): 712–726. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02093.x.

- Ball, S. J. 2008. “New Philanthropy, New Networks and New Governance in Education.” Political Studies 56 (4): 747–765. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00722.x.

- Ball, S. J. 2016. “Following Policy: Networks, Network Ethnography and Education Policy Mobilities.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (5): 549–566. doi:10.1080/02680939.2015.1122232.

- Ball, S. J., and C. Junemann. 2012. Networks, New Governance and Education. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press.

- Blackmore, J. 2011. “Bureaucratic, Corporate/Market and Network Governance: Shifting Spaces for Gender Equity in Education.” Gender, Work & Organization 18 (5): 443–466. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00505.x.

- Buchholz, W., and W. Peters. 2007. “Justifying the Lindahl Solution as an Outcome of Fair Cooperation.” Public Choice 133 (1–2): 157–169. doi:10.1007/s11127-007-9184-7.

- Burt, R. S. 1992. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Burt, R. S. 2005. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Capano, G., M. Howlett, and M. Ramesh. 2015. “Bringing Governments Back In: Governance and Governing in Comparative Policy Analysis.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 17 (4): 311–321. doi:10.1080/13876988.2015.1031977.

- Christopoulos, D. C. 2008. “The Governance of Networks: Heuristic or Formal Analysis? A Reply to Rachel Parker.” Political Studies 56 (2): 475–481. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00733.x.

- Csardi, G., and T. Nepusz. 2006. “The Igraph Software Package for Complex Network Research.” InterJournal ( Complex Systems). http://igraph.sf.net

- Datnow, A., and M. I. Honig. 2008. “Introduction to the Special Issue on Scaling Up Teaching and Learning Improvement in Urban Districts: The Promises and Pitfalls of External Assistance Providers.” Peabody Journal of Education 83 (3): 323–327. doi:10.1080/01619560802222301.

- DeBray, E., J. Hanley, J. Scott, and C. Lubienski. 2019. “Money and Influence: Philanthropies, Intermediary Organisations, and Atlanta’s 2017 School Board Election.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 52 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/00220620.2019.1689103.

- de Koning, M. 2018. “Public–Private Partnerships in Education Assessed Through the Lens of Human Rights.” In The State, Business and Education, edited by G. Steiner-Khamsi, and A. Draxler, 169–188. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Elliott, M., and B. Golub. 2019. “A Network Approach to Public Goods.” The Journal of Political Economy 127 (2): 730–776. doi:10.1086/701032.

- Ferrare, J., L. Carter-Stone, and S. Galey-Horn. 2021. “Ideological Tensions in Education Policy Networks: An Analysis of the Policy Innovators in Education Network in the United States.” Foro de Educacion 19 (1): 11–28. doi:10.14516/fde.819.

- French, J. R., B. Raven, and D. Cartwright. 1959. “The Bases of Social Power.” Classics of Organization Theory 7 (311–320): 1.

- Galey-Horn, S., S. Reckhow, J. J. Ferrare, and L. Jasny. 2020. “Building Consensus: Idea Brokerage in Teacher Policy Networks.” American Educational Research Journal 57 (2): 872–905. doi:10.3102/0002831219872738.

- Goodwin, M. 2009. “Which Networks Matter in Education Governance? A Reply to Ball’s ‘New Philanthropy, New Networks and New Governance in Education’.” Political Studies 57 (3): 680–687. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00804.x.

- Hamann, E. T., and B. Lane. 2004. “The Roles of State Departments of Education as Policy Intermediaries: Two Cases.” Educational Policy 18 (3): 426–455. doi:10.1177/0895904804265021.

- Hanneman, R. A., and M. Riddle. 2005. Introduction to Social Networks Methods. Riverside, CA: University of Carolina.

- Hoeckel, K., and R. Schwartz. 2010. Learning for jobs OECD reviews of vocational education and training: Austria. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD).

- Hogan, A. 2021. “Network ethnography and the cyberflaneur: evolving policy sociology in education.“ In Globalisation and Education, edited by B. Lingard, 284–301. New York: Routledge.

- Honig, M. I. 2004. “The New Middle Management: The Role of Intermediary Organizations in Complex Education Policy Implementation.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 26 (1): 65–87. doi:10.3102/01623737026001065.

- Honig, M. I., and T. C. Hatch. 2004. “Crafting Coherence: How Schools Strategically Manage Multiple, External Demands.” Educational Researcher 33 (8): 16–30. doi:10.3102/0013189X033008016.

- Jessop, B. 1998. “The Rise of Governance and the Risks of Failure: The Case of Economic Development.” International Social Science Journal 50 (155): 29–45. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00107.

- Junemann, C., S. Ball, and D. Santori. 2016. “Joined‐up policy: Network connectivity and global education governance.“ Handbook of Global Policy and Policy-Making in Education, edited by K. Mundy, A. Green, R. Lingard, and A. Verger, 535–553. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kabir, A. H. 2021. “Network governance’ and the Formation of the Strategic Plan in the Higher Education Sector in Bangladesh.” Journal of Education Policy 36 (4): 455–479. doi:10.1080/02680939.2020.1717637.

- Kapucu, N., and Q. Hu. 2020. Network Governance: Concepts, Theories, and Applications. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Klijn, E. H., and J. Koppenjan. 2012. “Governance Network Theory: Past, Present and Future.” Policy & Politics 40 (4): 587–606. doi:10.1332/030557312X655431.

- Koliba, C. J., J. W. Meek, A. Zia, and R. W. Mills. 2017. Governance Networks in Public Administration and Public Policy. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kolleck, N. 2016. “Uncovering Influence Through Social Network Analysis: The Role of Schools in Education for Sustainable Development.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (3): 308–329. doi:10.1080/02680939.2015.1119315.

- Lingard, B., and S. Sellar. 2013. “Globalization, Edu-Business and Network Governance: The Policy Sociology of Stephen J. Ball and Rethinking Education Policy Analysis.” London Review of Education 11 (3): 265–280.

- Lusher, D., J. Koskinen, and G. Robins, edited by. 2013. Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Methods, and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Menashy, F. 2016. “Understanding the Roles of Non-State Actors in Global Governance: Evidence from the Global Partnership for Education.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (1): 98–118.

- Moss, T. 2009. “Intermediaries and the Governance of Sociotechnical Networks in Transition.” Environment & Planning A 41 (6): 1480–1495.

- Muehlemann, S., and S. C. Wolter. 2020. “The Economics of Vocational Training.” In The Economics of Education (Second Edition): A Comprehensive Overview, edited by S. Bradley and C. Green, 543–554, London: Academic Press.

- Obstfeld, D., S. P. Borgatti, and J. Davis. 2014. “Brokerage as a Process: Decoupling Third Party Action from Social Network Structure.” In Contemporary Perspectives on Organizational Social Networks, edited by D. J. Brass, G. Labianca A. Mehra, D. S. Halgin, and S.P. Borgatti, Vol. 40, 135–159. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Onyoin, M., and C. H. Bovis. 2022. “Sustaining Public–Private Partnerships for Public Service Provision Through Democratically Accountable Practices.” Administration & Society 54 (3): 395–423.

- Opsahl, T., F. Agneessens, and J. Skvoretz. 2010. “Node Centrality in Weighted Networks: Generalizing Degree and Shortest Paths.” Social Networks 32 (3): 245–251.

- Parker, R. 2007. “Networked Governance or Just Networks? Local Governance of the Knowledge Economy in Limerick (Ireland) and Karlskrona (Sweden).” Political Studies 55 (1): 113–132.

- Piopiunik, M., and P. Ryan. 2012. “Improving the transition between education/training and the labour market: What can we learn from various national approaches?“ EENEE Analytical Report 13.

- Reckhow, S., and J. W. Snyder. 2014. “The Expanding Role of Philanthropy in Education Politics.” Educational Researcher 43 (4): 186–195.

- Renold, U., K. Caves, and M. E. Oswald-Egg. 2019. “Governance im Berufsbildungssystem Schweiz: Systemische Steuerung des schweizerischen Berufsbildungssystems.” (No. 127). KOF Studien

- Robertson, S., K. Mundy, and A. Verger, edited by. 2012. Public Private Partnerships in Education: New Actors and Modes of Governance in a Globalizing World. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Rowe, E. E. 2021. “Venture Philanthropy in Public Schools in Australia: Tracing Policy Mobility and Policy Networks.” Journal of Education Policy. doi:10.1080/02680939.2021.1973569.

- Schuster, J., H. Jörgens, and N. Kolleck. 2021. “The Rise of Global Policy Networks in Education: Analyzing Twitter Debates on Inclusive Education Using Social Network Analysis.” Journal of Education Policy 36 (2): 211–231.

- Scott, J., and H. Jabbar. 2014. “The Hub and the Spokes: Foundations, Intermediary Organizations, Incentivist Reforms, and the Politics of Research Evidence.” Educational Policy 28 (2): 233–257.

- Simkins, T. 1994. “Efficiency, Effectiveness and the Local Management of Schools.” Journal of Education Policy 9 (1): 15–33.

- Smylie, M. A., and T. B. Corcoran. 2009. “Nonprofit Organizations and the Promotion of Evidence-Based Practice in Education.” In The Role of Research in Educational Improvement, edited by J. D. Bransford, D. J. Stipek, N. J. Vye, L. M. Gomez, and D. Lam, 111–136. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard Education Press.

- Steiner-Khamsi, G., and A. Draxler, edited by. 2018. The State, Business and Education: Public-Private Partnerships Revisited. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Talamàs, E., and O. Tamuz 2017. Network Cycles and Welfare. Available at SSRN 3059604.

- Tao, Y. 2022. “Understanding the Interactions Between Multiple Actors in Network Governance: Evidence from School Turnaround in China.” International Journal of Educational Development 91: 102590.

- Tao, Y., and S. Liu. 2022. “Network Governance in Education: The Experiences and Struggles of Local Governments in Chinese School Turnaround.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 42 (2): 305–319.

- Ulibarri, N., and T. A. Scott. 2017. “Linking Network Structure to Collaborative Governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 27 (1): 163–181.

- Velotti, L., A. Botti, and M. Vesci. 2012. “Public-Private Partnerships and Network Governance: What are the Challenges?” Public Performance & Management Review 36 (2): 340–365.

- Verger, A., & M. Moschetti 2017. Public-Private Partnerships as an Education Policy Approach: Multiple Meanings, Risks and Challenges. Education Research and Foresight Working Papers, UN.

- VPET Act. 2002. Federal Act on Vocational and Professional Education and Training. Switzerland. https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/20001860/201901010000/412.10.pdf

- Wang, H., W. Xiong, G. Wu, and D. Zhu. 2018. “Public–Private Partnership in Public Administration Discipline: A Literature Review.” Public Management Review 20 (2): 293–316.

- Willems, T. 2014. “Democratic Accountability in Public–Private Partnerships: The Curious Case of Flemish School Infrastructure.” Public Administration 92 (2): 340–358.

- Williamson, B. 2014. “Mediating Education Policy: Making Up the ‘Anti-politics’ of Third-Sector Participation in Public Education.” British Journal of Educational Studies 62 (1): 37–55.

Appendix

Table A1. Network summary.