ABSTRACT

Critiques of international education policy frequently take issue with how it stabilises neoliberal values at the expense of the progressive aims of education. Yet the humanism underpinning these debates can work to exclude environmental concerns from the remit of educational policy. This article offers a posthuman critique of the Australian Strategy for International Education 2021–2030 that does not take for granted that international education policy should be humanistic but considers how it comes to be affirmed as such. Through a discourse analysis of the Strategy and supporting materials, this article identifies three manoeuvres that affirm the policy as humanistic. Firstly, neoliberal values and notions of wellbeing are wedded together in a shared understanding that the Strategy must be student centred. Secondly, the Strategy reinscribes divisions between humans and nature by casting land as a passive backdrop for human activities. And thirdly, the Strategy makes a claim to perpetuity by linking the acquisition of human skills with a sustainable and prosperous future. The conclusion contends that international education policy cannot ignore the impacts of human activity on the world and must nurture the vast range of interdependencies that sustain life.

Introduction

Since the early 1990s, international education has become a key feature of tertiary education in many settings across the globe. Countries such as Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and United States have emerged as key ‘receiving countries’ of international students, especially from nations across the Asian region. This flow of students has been made possible by a raft of policy measures that have incentivised universities to ‘recruit’ international students (Findlay Citation2011). The stated aims of international education policies are frequently articulated in terms of building stronger bilateral ties, enhancing soft power, addressing global challenges, and promoting economic growth (Altbach and Knight Citation2007; Lomer Citation2017; Wilkins and Huisman Citation2012). Yet many critics argue that international education policy is motivated primarily by commercial imperatives and market interests (Blackmore, Gribble, and Rahimi Citation2017; Rizvi and Lingard Citation2010). From this perspective, international education policy has become a vector for advancing and stabilising neoliberal values, often giving more emphasis to producing workers to serve the knowledge economy than to fostering the progressive aims of higher education (Ball Citation1998; Bamberger, Morris, and Yemini Citation2019; Marginson Citation2006; Citation2011; Robertson, Citation2005).

At stake in these debates are normative questions about what values international education policy should encode and what kind of citizens it should cultivate (Stein Citation2017). In recent times, tensions have emerged over how much emphasis should be placed on skills and jobs training, which disciplines funding should be channelled toward, and how closely universities should work with industry (Arkoudis et al. Citation2019; Clarke Citation2018; Conroy and McCarthy Citation2021; Succi and Canovi Citation2020). While there is significant disagreement about these issues, the competing positions of policy makers, researchers and other actors tend to converge in the assessment that international education should be organised to meet the needs and interests of human beings (Bayne Citation2018; Biesta Citation1998; Snaza et al. Citation2015). In the Australian setting, for instance, a diverse set of actors share a conviction that meaningful international education policy must be student centred. As we will see, this has been enshrined as a key pillar within the Australian Government’s most recent international education policy. Therefore, while actors disagree about what humans’ needs are and how they might be realised, this article contends that their positions are anchored in a humanism that can work to exclude climate change and ecological crises from the remit of international education policy.

Posthumanism creates scope for pushing critiques of educational policy in new directions by rejecting the notion of human exceptionalism and locating human beings as continuous with the material and immaterial world (Barad Citation2007; Gourlay Citation2021). Sharing ontological assumptions with indigenous knowledges and cosmologies, human beings are not considered to be observers who are somehow separate from the world but are thoroughly enmeshed within it (Fenwick, Edwards, and Sawchuk Citation2011; Rousell Citation2016; Smith, Tuck and Yang, Citation2019). In contrast to tenets of Western philosophy that take humans to be autonomous, rational, and independent beings, posthumanism emphasises that humans exist in – and are constituted through – relations with other humans, species, resources, objects, technologies, spaces and the environment (Fenwick and Landri Citation2012; Gravett, Taylor, and Fairchild Citation2021). This relational ontology unsettles some of the epistemological premises that have underpinned Western philosophy and modern education systems. For instance, binaries that have been taken to denote relations of negative exclusion – nature/culture, human/animal, mind/body, subject/object, teacher/student – are framed instead as relations of mutual constitution. This ontological position thus considers the lives of human beings and imperatives of international education as necessarily entwined with the wellbeing of the environment.

This article offers a posthuman critique of the Australian Government’s recent Australian Strategy for International Education 2021–2030 (hereafter the Strategy). A discourse analysis of the Strategy and public submissions made during the consultation process revealed some of the ways the Strategy is affirmed as humanistic. Additional textual materials directly related to the Strategy were also analysed, such as government websites and websites of relevant associations, newspaper articles and social media posts. The empirical sections draw out three interrelated manoeuvres that demarcate the remit of international education policy as related strictly to – and as an enabler of – human endeavours. Firstly, neoliberal values and notions of human wellbeing are wedded together in a shared understanding that the Strategy is and must be student centred. Secondly, the Strategy reinscribes divisions between humans and nature by casting land as a passive backdrop for human activities or as markets to be extracted from. And thirdly, the Strategy makes a claim to perpetuity by linking the acquisition of human skills with a sustainable, prosperous, and secure future. After drawing together the main findings and discussing their implications, the conclusion contends that posthumanism has the potential to transform the mandate of international education by unseating its focus on humans and attending to the broader range of interdependencies that sustain life.

Discourse analysis and policy research

The article takes leads from a lineage of critical policy scholarship and policy sociology, particularly as those fields of research relate to education. This scholarship developed throughout the 1980s in part as a response to dominant conceptions of educational policy that apprehended it in technical and instrumental terms (Ball, Citation1990; Ball Citation2017, Citation2021; Ozga Citation2021; Ozga and Lingard Citation2006). Working with theory and insights from across the social sciences, this field of research conceived of educational policy as marked by conflict, politics and power relations, with interventions drawing on concepts such as affect, mobility, materiality, space and scale (Ball Citation2016; Gorur Citation2011; Larsen and Beech Citation2014; CitationLewis, 2021; McKenzie, Citation2017; Peck and Theodore, Citation2015; Savage, Citation2020). A pertinent development in this field has been greater attention to the ontological underpinnings of policy and policy research (Webb and Gulson, Citation2015). This shift in analytical focus couples the enduring and foundational question of ‘what is policy?’ (Ball, Citation1993, Citation2015) with more thinking about how policy ‘assumes and constitutes the world it seeks to change’ (Carusi, Citation2021, p.233). This is an especially pertinent consideration in the present article. As stated above, its premise is that policy texts and some modes of policy critique share ontological underpinnings in humanism which delineate the remit of education policy as strictly humanistic.

Discourse analysis is a productive method of taking up Webb and Gulson (Citation2015, p.161) call to ‘turn our gaze’ on the ontologies of policy, because of its capacity to illuminate how language, meaning, and power work through policy texts (Ball, Citation1990; Levinson, Sutton, and Winstead Citation2009; Taylor, Citation2004). There is no singular definition of discourse and discourse analysis has been conducted in various ways in studies of education policy (Anderson and Holloway, Citation2020). Here, following Foucault (1974), discourses are understood as historically contingent practices that systematically shape what can be thought and said about the world. Conceived as such, discourses might seek to settle and pattern modes of thought and practice, amid that which has and can only ever be ruptured (Rabinow and Rose, Citation2003; St Pierre and Pillow, Citation2000). Analyses of discourse should therefore treat the themes, emphases, utterances and silences within policy as contingent and co-constituted through discursive practices that render some objects knowable and governable and others not (Leipold et al. Citation2019). It might proceed through techniques of thematic and iterative coding of multiple textual materials, recognising that such attempts can only ever be partial (Lester, Lochmiller and Gabriel, Citation2016) – and that there is no place outside of discourse from which to deconstruct it (Derrida Citation2016). Even so, a discourse might be ‘retreated from’ through analysis of how it works and what it does (Snaza et al. Citation2015, 3), and by unpacking how it is constitutive of the broader social, political, cultural, and economic environment (Gee, Citation2014).

The methodological approach therefore necessitates an overview of the process through which the Strategy was formed and the textual material it was productive of. The Strategy was formed through consultation of over 1600 stakeholders over a two-year period, commencing in 2019. The development of the policy was led by the Council for International Education which formed in 2016 to guide the international education sector and specifically to drive the implementation of the policy which preceded the Strategy, the National Strategy for International Education 2025. This previous policy was intended to guide the sector until 2025. However, with the onset of COVID-19, economic uncertainty, shifting geopolitical relations and increased competitiveness in the sector, the Council recommended a new policy be developed. This process began in 2020 with the development of a consultation paper, Connected, Creative, Caring: An Australian Strategy for International Education. Released in March 2021, the consultation paper unpacked the rationale for a new policy and concluded with eight discussion questions that the former Minister for Education and Youth invited stakeholders and members of the public to respond to. Written submissions were invited throughout April 2021, following which a series of webinars were held to clarify the Strategy’s aims and vision. Following this process, the Strategy was officially launched by the then Department of Education, Skills, and Employment in November 2021.

Material that was analysed for this project included the Strategy itself, its predecessor the National Strategy for International Education 2025, written submissions made during the public consultation process, and other publicly available texts that directly mention the Strategy. This latter category of data included recorded webinars, websites, media reportage and social media threads and relevant academic and grey literature. Given the sheer quantity of material related to the Strategy, this latter category of data was analysed and consulted in detail but was not all systematically coded. While themes within this material are referred to in this article, it reports predominately on texts that were coded in full, focusing especially on the policy text itself as well as the public submissions made in response to the questions posed by the consultation paper. A total of 124 submissions were made from educational institutions (N = 52), represented peak bodies (N = 22), student service providers and non-government study bodies (N = 22), State of Federal Government departments or agencies (N = 11), members of the public (N = 9), and overseas education providers, agents, or educators (N = 8). Each of the eight questions were limited by a 500-word limit and contributions varied in length. Some submissions were as short as half a page of written text, however, most made greater use of the space available, with the longest submission in excess of 25 pages. All universities in Australia made written submissions. Of 124 submissions, 114 were publicly available and were thematically coded.

Texts were coded using software to aid the management, organisation, and interpretation of the large quantity of data. An initial phase of thematic coding was conducted by reading each of the texts and identifying substantive codes. The iteration between theory and material (Xu and Zammit Citation2020) revealed how the discursive work performed through the texts affirms its humanism. A second phase of coding gauged whether these codes could be systematically supported with evidence across the texts (Maher et al. Citation2018) as well as to identify tensions, selectivity, and discord between materials (Ozga and Lingard Citation2006). Through the analysis, three discursive manoeuvres emerged that correspond with the subheadings in empirical sections of this article. In brief, these include centring the student, domesticating land, and securing human futurity. The analysis presented in this article attempts to tease out synergies and tensions between the policy text and public submissions by unpacking how they support one another and how they sometimes diverge. Accordingly, the empirical sections at times give attention to the policy text itself, while in other moments the analysis draws on other categories of data. It must be stated at the outset, however, that a humanist ontology largely underpinned the public submissions made to the Council. In this way, the consultation process itself affirmed the remit of international education as related quite strictly to human endeavours.

The methodology of this article and its attempt to ‘get at’ the ontology of the Strategy provides grounds to question the aims and logics of the Strategy, and to push critical policy research in productive directions. The Strategy identifies four key pillars to anchor its ‘strategic priorities’ over the next decade, including ‘Diversification’, ‘Meeting Australia’s skills needs’, ‘Students at the centre’, and ‘Growth and global competitiveness’. These key pillars register persistent concerns about international education in Australia, respectively, the overdependence on Chinese students, the desire to channel more students into STEM disciplines, hardships and experiences of discrimination among international students, and the desire to generate economic growth by expanding the sector. Critical policy analysis might explore tensions that emerge in the text between these key pillars, such as how the stated aim of prioritising students’ interests might come into conflict with attempts to channel them into particular subject areas; or how the prospect of fostering student wellbeing and connection is limited by an economic logic that enshrines individualism (Stein Citation2017; Verlie Citation2022). The analysis developed in this article works with these critiques at times, especially at junctures where the emancipatory politics of humanism and posthumanism overlap. But the main argument moves along a different trajectory. It does not take for granted that international education is or should be a project of humanism but focuses instead on how the Strategy comes to be affirmed as such. The analysis therefore interrogates how it is that the imperatives of international education come to be viewed as entirely separate from the planetary wellbeing, and how it is that the Strategy manages to hold the interests of humans and the environment apart. Developing this line of inquiry calls for an initial engagement with the linkages between education and humanism more generally.

Education, posthumanism and the Anthropocene

From the writings of Plato through to the development of modern education systems and the massification of higher education, formal education has been framed as a human endeavour par excellence (Snaza Citation2015). It has quite explicitly been conceived as a process of forming human subjects and inculcating moral, social and cognitive capacities among them, often tied to Enlightenment thinking, the building of empires and the interests of colonialism (McCoy Citation2014; Nakata Citation2007; Viswanathan Citation1989). Throughout much of the twentieth century, education systems across the globe were ordered around – and worked to affirm – understandings of ‘Man’ as a rational, autonomous, and independent actor. In more recent times, this vision has informed and legitimated the ordering of education systems around neoliberal values (Fenwick Citation2012; Gershon Citation2011). Even as progressive educators developed learning theories that drew attention to the embodied, social, and relational character of learning (Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Noddings Citation1995), they have mainly done so without questioning the centrality of the human subject (Gravett, Taylor, and Fairchild Citation2021). Humans might not be the individuated and rational beings Western philosophy has imagined, but it is human ends that education is oriented towards nonetheless (Biesta Citation1998, Citation2006).

One issue with conceiving of education in this way is that its own project of human realisation is flawed by the divisions among humans that it predicates. For if education is a process of becoming human, then those who are educated must necessarily be more human than those who are not (Biesta Citation2013; Ingold Citation2018; Pederson Citation2010). A second issue is how a focus on the human subject renders invisible the materiality and situatedness of educational processes (Fenwick and Landri Citation2012). With a focus squarely on human cognition and agency, land and the environment are considered irrelevant to humanistic conceptions of education and learning (Simpson, Citation2014). Scholars writing from Indigenous perspectives and ontologies have exposed the violence of this position (Smith, Tuck and Yang, Citation2019; Wildcat et al., Citation2014). Not only did the imagined separation of humans from nature authenticate dominion over land, but the designation of Indigenous populations as less than human meant that they could be dispossessed of it with impunity (Tuck, McKenzie, McCoy Citation2014). The erasure of and from land that education systems helped create, is especially significant in maintaining relations of domination in contexts of settler colonialism, such as Australia (Fletcher et al. Citation2021; Gerrard, Sriprakash, and Rudolph Citation2022; McCoy Citation2014; Stein Citation2019).

The limits of humanism as they relate to the impacts on the environment have also been articulated by scholars writing from the field of what Bayne (Citation2018) terms ‘ecological posthumanism’. Critics writing from this position have highlighted how humanism worked to recast Earth – once understood as a life-giving force – as a repository of resources to be plundered (Calderon Citation2014; Ingold Citation2011). This interdisciplinary field of research has thus illuminated how humanism is bound up with forms of pillage and extraction that have precipitated ecological crises, the extinction of species and endangering others, discredited indigenous knowledges, and legitimated the industrialised abuse of non-human animals (Bayne Citation2018; Pederson Citation2010; Simpson, Citation2014). Scholars writing from this perspective typically refer to posthumanism not to name an emerging epoch, but rather to emphasise how centring human cognition and agency has always been problematic (Fenwick and Edwards, Citation2010). In this usage, the term posthumanism does not invoke a future without humans but rather one in which they are ontologically decentred. The epochal shift referred to among some of these writers is the Anthropocene, which suggests human activities have impacted the earth and environment such that they constitute a distinct geological age (Castree Citation2014; Rousell Citation2016). Having had profound impacts on the biophysical world, the Anthropocene suggests human dominion over Earth is entering a phase where all planetary life is under threat. To persist in framing education systems as strictly humanist projects is thus to court the prospect of our own extinction.

To write from the Anthropocene with a posthuman ontology is to decentre humans and place the environment at the centre of the critique. Thus where the Strategy’s highlights concerns about market disruption, student welfare and economic growth as the main issues it must address, posthumanism surfaces a range of additional and more urgent concerns. In summer of 2019–2020 – the same year that the Council for International Education recommended that a new international education strategy be developed – Australia endured the worst bushfires in its recorded history. Over 30 million hectares of vegetation were burned and up to three billion vertebrates and 240 trillion invertebrates were affected (Dickman Citation2021). The following year, when the consultation process for the Strategy began, floods wrought havoc in northern New South Wales, with floodwaters affecting some areas which were burned in bushfires the year previously. And at the time of writing, floodwaters have engulfed parts of central New South Wales, with waters in some parts yet to recede. All of this comes amid record levels of greenhouse gas emissions across the globe and as land clearing, livestock pressures, resource extraction, pest species and climate change threaten Australia’s living systems (Dickman and Lindenmayer Citation2022; IPCC Citation2022).

It is striking that Australia’s international education policy has remained silent on these issues. Indeed, the words ‘climate change’ do not appear in the policy text. One reason for this omission is that these events did not disrupt the international education sector in the same manner as the COVID-19 pandemic. Save for a small number of isolated and short-term campus closures, the business of international education was able to carry on unabated. But a more profound reason is that the humanist anchoring of international education policy is unable to confront the fraught and untenable position of human dominance over the world. While acknowledging that humanism has delivered significant benefits to vast numbers of people throughout history, posthumanism posits that the future of life on earth hinges on the capacity to move beyond it (Bayne Citation2018; Verlie Citation2022). Without abandoning the social progress that has been made through humanist critique, there is a pressing need for policy scholarship to trace the ways humanism is upheld and how human dominion over the natural environment is authenticated. In short, analyses must apprehend the limits of humanism. It is to such an analysis this article now turns.

The Australian strategy for international education 2021–2030: a posthuman critique

Centring students

At first glance, placing ‘Students at the centre’ as a key priority of the Strategy appears a welcome manoeuvre. It responds to a lineage of educational research that has highlighted the pressing need address the hardships international students endure, and to think about them as human beings rather than as economic units or ‘cash cows’ (Deuchar Citation2022a; Citation2023; Robertson, Citation2013). In a recorded excerpt from the International Education Association of Australia’s 2022 Annual Conference, one of the co-convenors of the International Education Council, stresses the importance of fostering student wellbeing, especially given the impacts of COVID-19. And this is a theme that is threaded through parts of the Strategy itself. Notably, the terms ‘wellbeing’ and ‘belonging’ did not appear in the Strategy’s predecessor the National Strategy for International Education 2025. Launched just five years earlier, the previous strategy embedded initiatives regarding students’ experiences under the key pillar of ‘Strengthening the fundamentals’ and did so mainly through the more tenuous notion of ‘support’. In this initial reading, therefore, the Strategy regards the interests of international students in more robust terms and surfaces them in a way that earlier policy did not (Deuchar and Gorur Citation2023).

The case to promote students’ interests in the Strategy is also made through the use of strategic and persuasive language. In the most immediate sense, the phrase ‘students at the centre’ has powerful resonances in educational contexts, invoking tenets of educational theory that situate students as active participants in pedagogic practices. ‘Student-centred learning’ foregrounds students’ capacities, values their perspectives and backgrounds, and reworks the power relations that characterised the ‘traditional’ classroom (Tangey Citation2014). The Strategy invokes this theory when it states the ‘right classroom mix can enhance the learning experience … when there are different cultures and perspectives in classrooms and campuses’. Part of the discursive allure of the Strategy, then, is that it gestures toward the strengths of international students and references the democratic possibilities of public education. A second reason that the phrasing ‘students at the centre’ appeals is that it implies that students’ wishes, desires, needs and interests will take precedence over those of other actors, such as educational institutions, policymakers, and employers. This is significant in a context where many commentators have suggested students’ interests continue to be marginalised (Forbes-Mewett and Sawyer Citation2016). To this end, the Strategy commits to maintaining ‘student representation on the Council for International Education to ensure the voices and experiences of international students continue to inform relevant policies’. To place students at the centre is thus ostensibly to commit to ensuring they have a productive, meaningful, and fulfilling time studying in Australia.

Yet the need to place ‘Students at the centre’ is interpreted in divergent ways throughout the text. The first sentence under the relevant key priority in the Strategy reads ‘Australia’s global reputation as a study destination of choice rests on our ability to provide a world-class experience for domestic and international students’. In this framing, supporting students and delivering a positive experience is important because Australia’s reputation is at stake. Similarly, in the subsequent section, the Strategy states ‘There is a need to better target international enrolments towards Australia’s future skills needs to grow businesses, create more jobs and aid our economic recovery’. This line of reasoning was supported through many public submissions, particularly those associated with industry. Contributors highlighted the need to foster ‘job ready graduates’, ‘employability skills’, ‘work integrated learning’ and to better align courses with economic demands. Potential tensions therefore emerge in the text between its stated commitment to students and economic demands. In some moments, the Strategy highlights the importance of supporting ‘international students to make meaningful connections with domestic students … beyond their campuses into their local communities’. But such sentiments are siloed in one pillar of the Strategy and are largely buried in a text and logic which is overwhelmingly economistic.

The problem with this framing from a humanist perspective is that student wellbeing and belonging are not attended to as holistically or seriously as they might be (Hong, Lingard, and Hardy Citation2022). Posthumanism shares the commitment to fostering a more inclusive, ethical, and caring international educational sector (Deuchar and Gorur Citation2023; Gravett, Taylor, and Fairchild Citation2021). But an additional problem with placing ‘students at the centre’ from a posthuman ontology is that the relational entanglements within which they are embedded fall away. This enables the text to couple references to belonging and ‘communities’ with an economic discourse that casts students as individual actors who are largely bracketed off from relations with others. Understood as discrete individuals, the Strategy sees no contradiction in claiming to centre the student for their own benefit at the same time as casting the student as an economic unit that might be manoeuvred for Australia’s gain. For instance, the Strategy states that ‘there is an opportunity to grow our international student market by expanding our high-quality education offerings to offshore and online markets’ and that this could be realised by ‘different delivery models and different price points’. The student inferred here is not a relational being in need of connection and care, but an independent and rational actor who might be leveraged to service the knowledge economy (Deuchar Citation2022b). Unsullied by interdependencies with other people and the environment, with nothing outside itself to attend to or nurture (Gershon Citation2011), the student centred in the Strategy is an unhindered one.

Centring an individual economic student in the text also works to shut down the possibility of understanding human concerns as entangled with the wellbeing of the planet (Bayne Citation2018). Indeed, humanism works by assuming human interests are paramount and apprehending those as distinct from the interests of non-human species and the environment (Pederson Citation2010; Taylor Citation2018). Notably, the policy formation processes were conducted to ensure the Strategy was human centric. The second question stakeholders were invited to respond to during public consultation sought ideas about how education ‘providers’ could deliver ‘the best possible student experience’. But the question was prefaced with the statement ‘Students should be at the centre of the new Strategy.’ This is a premise that all contributors in the consultation process accepted and that was especially well received in public commentary and media reportage. Even submissions which were critical the international education sector shared the assumption that ‘Man’ naturally stands at the centre of things (Bayne Citation2018). For instance, one submission stated that ‘other priorities’ including ‘driving enrolment growth and revenue streams’ have historically motivated the sector, before concluding that ‘International students must be at the centre of Australia’s International Education strategy’. Similarly, critical public commentary of the Strategy took issue with technical aspects of the policy in such a way that leaves its humanist anchoring intact, such as how it does not adequately integrate with migration policy.

The argument here is not that students’ interests are unimportant, but rather that the humanist ontology underpinning the text – revealed in part through the move to centre students – works to situate planetary wellbeing outside of the Strategy’s remit. In other words, to centre the student is to decentre the environment. This argument can be further developed by returning to the notion of ‘student centred learning’ and reading it as a spatial metaphor. Student-centred learning works in educational theory in part because it invokes a spatial setting within which pedagogic practices unfold (Tangey Citation2014). In summoning an imagery of the classroom, the notion of student-centred learning invites an ordering of classrooms that foster dialogue and collaboration among peers (Hickey and Riddle Citation2022). In practice, centring the student might amount to decentring the teacher by organising desks and chairs such that students face one another. Here, students are thoroughly enmeshed in relations with others whose practices enact the spatiality of the classroom (Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015). But the notion of centring the student in policy does not quite work in the same way. It is intended to mean the Strategy will give precedence to students’ needs, interests, and values. But as a spatial metaphor it encounters difficulties: for if the student is the centre of the Strategy, what constitutes the broader space within which they are positioned? Or more simply, where might the student be centred? The trouble one has grappling with this question owes in part to the way the Strategy conceives of space and apprehends land.

A nation without an environment and a surface that is not land

The sixth question stakeholders were invited to respond to during the consultation process was to consider how to ‘create a uniquely Australian education experience’. Most submissions offered a predictable line regarding the quality of education and labour market opportunities. But one submission from the Asia Education Foundation stated that ‘a uniquely Australian education experience starts with greater knowledge and understanding of Australia’s First Nations [peoples], and our connections to land, water, and sky’. The response went on to articulate the potential of First Nations’ knowledge and storytelling, linking them with other initiatives that have been developed to foster cultural competency in educational settings.

Strikingly, the only mention of Indigenous Australians in the Strategy lies in the Acknowledgement to Country prior to the policy itself. Save for this formality, Indigenous peoples are rendered invisible. One reading of the Strategy might be that it thus performs the same function as did the legal doctrine of terra nullius during the early phases of colonial settlement. Cast as a virgin territory free of human life, the entire continent was primed for takeover (Banner Citation2005; Fletcher et al. Citation2021). But if land for the colonialist was a bounty of minerals and resources ripe for appropriation, a source of wealth to be realised through agriculture, violence, and extraction, it is appropriated in an altogether different way in the Strategy. For in the Strategy, land – not mentioned at all in the text – is invoked only in the form of decorative geometric designs at various intervals throughout. With Australia rendered quite literally as a passive backdrop to the text, relevant only for the purposes of visual appeal, it as if the activities that constitute international education can and will unfold on a surface without form. And it is precisely this which makes it difficult to grapple with the Strategy’s attempts at centring the student as a spatial metaphor.

Precedent for denying land in this way is threaded through an education system that has long sought to liberate humankind from the trappings of nature. To be educated, to become civilised, was to be freed from the soil and sheltered from the vicissitudes of the environment (Viswanathan Citation1989). And for human dominion over the world to be maintained and for colonial projects to be executed, land too needed to be tamed (Calderon Citation2014). Taming land is part of the critical work the Strategy performs. In response to questions regarding Australia’s uniqueness and the ‘value proposition’ that might set it apart from its competitors, for instance, several submissions in the consultation process named ‘beaches’, ‘wild landscapes’, ‘the outback’ and ‘natural beauty’ as part of the nation’s distinct offering. These are dangerous terms for humanism: they animate the world and convey a sense of human surrender; they differentiate the land and return life to it. It is unsurprising, therefore, that none of these terms appear in the Strategy. Many of the spatial references the Strategy does invoke – campuses, classrooms, workplaces – speak of environments created by humans that exclude nature. What is more, these terms reference the discursive repertoire of formal education and industry much more so than they specify anything particular about the materiality or biota of land itself. In other words, the Strategy employs spatial references to the extent that they abstract from rather than situate within.

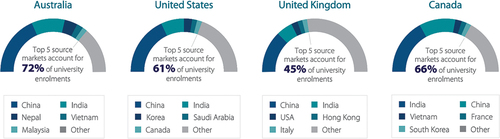

The Strategy’s attempts to domestic land are extended by how it designates and defines other geographical territories and regions. Neatly casting countries as either ‘competitors’ or ‘markets’, the Strategy presents a series of visual depictions that invite the reader to apprehend territories in these terms. One such visual depiction entitled () ‘International onshore enrolments in tertiary education by student source market, 2020’, for instance, consists of four infographics set horizontally across the page, with Australia and its competitor nations named respectively above them – United States, United Kingdom, and Canada. Beneath each of these countries is a semicircle with portions of it shaded different colours to indicate the percentage of students from a given ‘market’ studying in each host country. Shades of colour are said to represent students from China, India, and a series of other countries, mainly from across the Asian region. Set against concerns about Australia needing to diversify the ‘source markets’ from which it ‘recruits’ students, we learn that 72 percent of university enrolments in Australia come from just five countries. This is a larger percentage than that of Australia’s competitors, which exposes it to greater risk in the case of a market downturn among any of the sending countries.

Figure 1. International onshore enrolments in tertiary education by student source market, 2020.

Beyond this detail the infographics tell us very little, and in certain senses they are quite misleading. Rendering each infographic the same size, for example, conceals the fact that the size of the student cohort in these nations varies greatly. Some of the colours representing each ‘source market’ are scarcely distinguishable, and the same colours are used to represent different nations in separate infographics. It is not only that the infographics become difficult to read but they are also conceptually problematic: international students of an entire country are rendered homogenous when shaded a single colour, and students from one country differ only in shade of colour from the next. Significantly, however, these issues are not a concern from the point of the view of the Strategy. Because what these images are trying to convey is a way of apprehending the world (cf. Ingold Citation2011). In the same way that early cartographers’ rudimentary mappings of land were less about accuracy and more about demonstrating that land could be mapped, these infographics are inviting the reader to believe that entire nations with diverse geographies, environments, histories, and peoples can be rendered as two-dimensional shapes on a page. In these otherwise insignificant images, in the shaded portions of a semicircle, lies a mode of divorcing nations from nature, freeing territories of land (Ingold Citation2011), and casting entire countries as competitors or markets.

The corollary of casting nations as markets is framing their populations as consumers. Understood as an economic unit who carries and discharges capital, the international student is the primary consumer that ‘competitor nations’ are seeking to extract and attract. The Strategy is thus at pains to emphasise what it might offer customers as well as the benefits that customers offer Australia in turn. These latter benefits are predominately cast in economic terms, with the Minister’s Foreword stating that international education generated 40.3 billion dollars and supported 250 000 jobs in 2019. There are also attempts to illuminate the broader social and cultural benefits of international education to Australia, although these are never conveyed in particularly convincing terms (‘people-to-people links’) – this is not to say international students do not make rich contributions, but rather that the logic of consumerism lacks the vocabulary to articulate them. But the most pertinent point here is how the Strategy locates human activity as strictly beneficial for the country. With land cast as a mere platform for human endeavours, the Strategy works to invert the very premise of the Anthropocene. In the Anthropocene, the impact and scale of human activity on the world has compromised its capacity for renewal (Castree Citation2014). Yet in the Strategy, human activity is precisely what is set to deliver lasting benefits for the country. This makes sense from the viewpoint of the Strategy precisely because it does not register the environment, there is no life-giving land.

An uncertain future secured with human skills

In rendering land a lifeless surface and casting the environment aside, the Strategy finds in the economy the principal challenges it must navigate in the future. Identifying COVID-19 as the main setback the sector has endured as well as ‘changing bilateral relationships with key partner countries’, the Strategy articulates losses to the sector in almost exclusively economic terms. This reveals in fine clarity the dominant logic threaded through the text. It is economic growth that has borne the cost of the pandemic and which the Strategy seeks to recover through initiatives developed to retain ‘market share’. The second key priority – ‘Meeting Australia’s skills needs’ – also explicitly locates international education as a mode of fostering economic growth, with an emphasis on aligning student enrolments with sectors that will ‘drive our growth in the future’. The Strategy’s stated aim of placing students at the centre seems lost in assertions like this. Instead, the student appears as a pawn on a chessboard that might be manoeuvred for ‘industry needs’. However, the trajectory of critique here is concerned with tracing how the Strategy affirms its humanist anchoring even as its attempt at centring the student seem rather inadequate.

In identifying the challenges to – and potential of – the international education sector in economic terms, the human subject is located as both asset and antidote. Understood as an autonomous and rational actor, the human subject is primed to be skilled in ways that benefit Australia’s economy in the future. As the Strategy states, ‘Skills development and lifelong learning will be key as some jobs change, new jobs emerge, and technological progress continues’. One of the ‘key challenges’ the Strategy identifies in this regard is how to ‘incentivise international students to study in areas of skills needs’. This focus on skilling students was supported by a number of contributors in the consultation process, with many emphasising the importance of work integrated learning and the promise of STEM disciplines for driving economic growth. A critical reading of what the Strategy is attempting here might be that it simply justifying its own existence: it is only by representing uncertainty in partial and comprehensible terms, that it is able to proffer solutions. But a posthuman critique points to how a focus on skills locates humans themselves as the antidote to uncertainty. In emphasising the importance of equipping students with skills, the Strategy renders a future that is uncertain principally because humans do not yet have the competencies a changing economy might demand. From a humanist standpoint, it follows that uncertainty will be managed when students acquire them.

In forecasting a future that will be managed through the acquisition of skills, the Strategy works to perform an affirmation of the human future itself. The Strategy sometimes bolsters its claims by referencing the work of other government agencies, stating that ‘The Australian Government’s Services Exports Action Plan underlines that Australia’s international competitiveness is contingent on the skills and qualifications of the Australian workforce’. Notwithstanding the Strategy’s attention to the impacts of COVID-19 and changing geopolitical relations, there is a strong note of optimism throughout much of the text. But in its entire neglect of climate change and ecological collapse, it reads somewhat ahistorical. There is no mention of the greatest threat to human and non-human life on earth. Notwithstanding its emphasis on growth and progress, this ahistoricism robs the Strategy of a sense of temporal unfolding. In some instances, this ahistoricism is even more stark, such as when the Strategy states, ‘International students have always been an important source of labour for Australia’. In other instances, the Strategy is explicitly seeking a return to the past, indicated by its emphasis on ‘recovery’. By attempting to secure the future with human skills and in seeking to recover what the sector has always done, time does not unfold in the text but becomes circular. The temporal logic underpinning the Strategy’s claims to perpetuity is this: the past is the future, and the future is the past.

In linking a sustainable, productive, and secure future with the acquisition of human skills, the Strategy advances an especially problematic stance in relation to climate change. This is not a form of climate change denial that refutes the weight of evidence presented before it, but a stance that conceals the very existence of the problem in the first place (Peterson, Stuart, and Gunderson Citation2019). We see linkages between human skills and an affirmative future littered throughout the text: ‘Access to globally in-demand skills such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing and digitisation is essential to Australia’s economic prosperity’, and

Research collaboration, micro-credentials and other short courses will be increasingly relevant into the future and provide opportunities for government to work with the sector to expand into new markets and meet evolving skills needs.

In an effort to perpetuate the current social order, the Strategy is imploring us to believe humanism will solve the problems of its own making. Stamped with the authority of a government department, produced through rigorous consultation, the Strategy arrives at the very premise from where it began: humans are the means and humans are the ends. Maintaining human dominion over the world is not only possible but promising, and in securing that dominion lies a prosperous future.

Conclusions

Most radical critiques of international education policy tend to take issue with how it encodes neoliberal values, entrenches colonial hierarchies and reproduces a range of social injustices along axes of race, gender, class, language and Indigeneity (Altbach Citation2004; Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo Citation2009; Tikly Citation2004). These have been especially productive for illuminating the power relations threaded through international education as well as for critiquing how the boundaries humanism are drawn. On this latter point, some critiques have shown how particular visions of ‘Man’ were crucial for Othering processes that worked to delineate who counts as human and the violence this engenders. Posthumanism shares political affinities with these strands of critique insofar as it seeks to dissolve hierarchies and ameliorate injustices (Gravett, Taylor, and Fairchild Citation2021; Taylor Citation2018). But in decentring humans, rather than strictly challenging dominant understandings of who counts as human, posthumanism moves the analysis in a different direction. This is a critique not concerned with redefining the boundaries of humanism, but with apprehending its limits. Accordingly, this article has considered how international education policy is affirmed as humanistic and how this works to exclude planetary wellbeing from its remit. It has argued that the Strategy attempts to do this by centring the student, casting land as a platform for human endeavours, and by imagining that the future can be secured with the acquisition human skills.

The Strategy thus apprehends international education as a human activity understood as distinct from the environment. Yet framing education strictly as a humanist project has been devastating for the planet (Bayne Citation2018). The most recent report from the IPCC states that from 2021–2040, the projected impacts of global warming are likely to ‘cause unavoidable increases in multiple climate hazards and present multiple risks to ecosystems and humans’ (IPCC Citation2022, 13). The Australian government cannot afford to have an international education policy that completely ignores the environment throughout the first decade of the same period. To do so does not just accept and conceal ecological collapse; it legitimates it. In the strongest possible terms, the Strategy must be revoked and redrawn. One argument in defence of the Strategy as it stands is that while environmental issues are clearly important, they will most adequately be dealt with through other policies designed for that express purpose. This argument rest on an ontology of separateness. Instead of viewing the wellbeing of the planet as a very condition of possibility for the international education sector, it imagines that it is possible to apprehend the imperatives of international education and the needs of the environment separately. But the two must necessarily be entangled. An attempt to mark them as separate is an attempt to secure humanism and maintain human dominion over the world.

The Strategy’s entire neglect of climate change and ecological crises is mirrored in the recent international education policies of its main ‘competitor nations’, including United Kingdom, Canada and United States. Yet precedent for the kind of environmental emphasis needed in educational policy is beginning to emerge among multilateral organisations. UNESCOs 2021 report, Reimagining our futures together: a new social contract for education, for instance, insists that the mandate of education must be transformed beyond a focus on the economy toward caring for each other, other species, and for the planet. The report (UNESCO, Citation2021, p.8) states that ‘Climate change and environmental degradation threaten the survival of humanity and of other species on planet Earth’, and that ‘environmental disasters are accelerated by economic models depending on unsustainable levels of resource use’. These concerns are echoed by the OECDs most recent position paper related to its Learning Framework 2030, titled The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. Published in 2018 (OECD, Citation2018), the report states that the first challenge a new framework must address is ‘Climate change and the depletion of natural resources [that] require[s] urgent action and adaptation’. These reports offer promising starting points for reconsidering the possibilities and imperatives of international education. Yet they must also be subjected to rigorous scrutiny and analysis. Such critique might productively proceed from the premise that the extent and kind of the transformation needed will not be realised within a humanist framework.

In decentring human beings, posthumanism offers ontological and epistemological grounds for the radical transformation of international education policy (Deuchar and Gorur Citation2023). It situates the imperatives of international education as necessarily entwined with profound challenges such as climate change and planetary destruction. A posthuman critique therefore makes it untenable for international education policy to remain silent on these issues. Yet posthumanism demands more than simply recognising the context in which international education unfolds. Instead, it compels international education policy to consider how it might nurture a broader range of connections and interdependencies that sustain the world. Fostering planetary wellbeing becomes one of the central aims of international education (Deuchar and Gorur Citation2023). With this aim in mind, further research might attempt to rearticulate, reimagine, and redesign international education policy by centring land and the environment. It might consider the ways disciplinary boundaries are conceived and drawn how they relate to planetary wellbeing (Decuypere, Hoet, and Vandenabeele Citation2019; Rousell Citation2016; Taylor Citation2018). It might explore how policy and practitioners might foster practices of relationality among students and nonhuman actors in spaces of education (Gravett and Ajjawi Citation2022; Gravett, Taylor, and Fairchild Citation2021). And it might centre – rather than incorporate – indigenous knowledges and cosmologies that begin with land, water and sky and human relations to them (Simpson, Citation2014; Wildcat et al., Citation2014). All of this will be necessary if humans, non-humans, and other matter are to be drawn together in ways that make it possible to dwell in the Anthropocene.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Andrew Wilkins for handling this manuscript and the three anonymous reviewers who provided valuable feedback. Much of the intellectual labour for this article occurred while I sat in a park opposite where I lived at the time. It feels to me as if this article was authored as much by myself as by that place, or better, through our entanglement and mutual becoming. The article also benefited greatly from conversations with Radhika Gorur and Jason Beech. Any faults that remain throughout are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrew Deuchar

Andrew Deuchar conducts education focused geographical research. He has conducted ethnographic research in India and research regarding international education policy and practice in Australia

References

- Altbach, P. 2004. “Globalisation and the University: Myths and Realities in an Unequal World.” Tertiary Education and Management 10 (1): 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2004.9967114.

- Altbach, G., and J. Knight. 2007. “The Internationalization of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities.” Journal of Studies in International Education 11 (3–4): 290–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303542.

- Anderson, K. T., and J. Holloway. 2020. “Discourse Analysis as Theory, Method, and Epistemology in Studies of Education Policy.” Journal of Education Policy 35 (2): 188–221.

- Arkoudis, S., M. Dollinger, C. Baik, and A. Patience. 2019. “International students’ Experience in Australian Higher Education: Can We Do Better?” Higher Education 77 (5): 799–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0302-x.

- Ball, S. 1990. Politics and Policymaking in Education: Explorations in Policy Sociology. London: Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. 1998. “Big Policies/Small World: An Introduction to International Perspectives in Education Policy.” Comparative Education 34 (2): 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050069828225.

- Ball, S. J. 2016. “Following Policy: Networks, Network Ethnography and Education Policy Mobilities.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (5): 549–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2015.1122232.

- Ball, S. J. 2017. “Laboring to Relate: Neoliberalism, Embodied Policy, and Network Dynamics.” Peabody Journal of Education 92 (1): 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1264802.

- Ball, S. J. 2021. “Response: Policy? Policy Research? How Absurd?” Critical Studies in Education 62 (3): 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2021.1924214.

- Bamberger, A., P. Morris, and M. Yemini. 2019. “Neoliberalism, Internationalisation and Higher Education: Connections, Contradictions and Alternatives.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 40 (2): 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1569879.

- Banner, S. 2005. “Why Terra Nullius? Anthropology and Property Law in Early Australia.” Law and History Review 23 (1): 95–131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248000000067.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv12101zq.

- Bayne, S. 2018. “Posthumanism: A Navigation Guide for Educators.” Journal for Research and Debate 1 (2): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.17899/on_ed.2018.2.1.

- Biesta, G. J. J. 1998. “Pedagogy without Humanism: Foucault and the Subject of Education.” Interchange 29 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007472819086.

- Biesta, G. J. J. 2006. Beyond Learning: Democratic Education for a Human Future. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

- Biesta, G. J. J. 2013. The Beautiful Risk of Education. New York: Routledge.

- Blackmore, J., C. Gribble, and M. Rahimi. 2017. “International Education, the Formation of Capital and Graduate Employment: Chinese Accounting graduates’ Experiences of the Australian Labour Market.” Critical Studies in Education 58 (1): 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2015.1117505.

- Calderon, D. 2014. “Speaking Back to Manifest Destinies: A Land Education-Based Approach to Critical Curriculum Inquiry.” Environmental Education Research 20 (1): 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.865114.

- Castree, N. 2014. “The Anthropocene and the Environmental Humanities: Extending the Conversation.” Environmental Humanities 5 (1): 233–260. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615496.

- Clarke, M. 2018. “Rethinking Graduate Employability: The Role of Capital, Individual Attributes and Context.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (11): 1923–1937. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152.

- Conroy, K. M., and L. McCarthy. 2021. “Abroad but Not Abandoned: Supporting Student Adjustment in the International Placement Journey.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (6): 1175–1189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1673718.

- Decuypere, M., H. Hoet, and J. Vandenabeele. 2019. “Learning to Navigate (In) the Anthropocene.” Sustainability 11 (2): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020547.

- Derrida, J. 2016. Of Grammatology. Fortieth anniversary ed. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Deuchar, A. 2022a. “The Problem with International students’ ‘Experiences’ and the Promise of Their Practices: Reanimating Research About International Students in Higher Education.” British Educational Research Journal 48 (3): 504–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3779.

- Deuchar, A. 2022b. “The Social Practice of International Education: Analysing the Caring Practices of Indian International Students at Australian Universities.” Globalisation, Societies & Education 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2022.2070130.

- Deuchar, A. 2023. “International Students and the Politics of Vulnerability.” Journal of International Students 13 (2): 206–211. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v13i2.4815.

- Deuchar, A., and R. Gorur. 2023. “A Caring Transformation of International Education: Possibilities, Challenges and Change.” Higher Education Research and Development 42 (5): 1197–1211. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2023.2193726.

- Dickman, C. R. 2021. “Ecological Consequences of Australia’s “Black Summer” Bushfires: Managing for Recovery.” Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 17 (6): 1162–1167. https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.4496.

- Dickman, C. R., and D. B. Lindenmayer. 2022. “Australia’s Natural Environment: A Warning for the World.” In Sustainability and the New Economics, edited by S. J. Williams and R. Taylor, 33–49. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78795-0_3.

- Fenwick, T. 2012. “Matterings of Knowing and Doing: Sociomaterial Approaches to Understanding Practice.” In Practice, Learning and Change: Practice-Theory Perspectives on Professional Learning, edited by P. Hager, Al. Lee, and A. Reich, 67–84. London: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4774-6_5.

- Fenwick, T., and R. Edwards. 2010. Actor-Network Theory in Education. London: Routledge.

- Fenwick, T., R. Edwards, and P. Sawchuk. 2011. Emerging Approaches to Educational Research: Tracing the Socio-Material. London: Routledge.

- Fenwick, T., and P. Landri. 2012. “Materialities, Textures and Pedagogies: Socio-Material Assemblages in Education.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 20 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2012.649421.

- Findlay, A. M. 2011. “An Assessment of Supply and Demand-Side Theorisations of International Student Mobility.” International Migration 49 (2): 162–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00643.x.

- Fletcher, M., R. Hamilton, W. Dressler, and L. Palmer. 2021. “Indigenous Knowledge and the Shackles of Wilderness.” Environmental Sciences 118 (40): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022218118.

- Forbes-Mewett, H., and A. M. Sawyer. 2016. “International Students and Mental Health.” Journal of International Students 6 (3): 661–677. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v6i3.348.

- Gee, J. P. 2004. An introduction to discourse analysis: theory and method. Fourth ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gerrard, J., A. Sriprakash, and S. Rudolph. 2022. “Education and Racial Capitalism.” Race, Ethnicity & Education 25 (3): 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2021.2001449.

- Gershon, I. 2011. “Neoliberal Agency.” Current Anthropology 52 (4): 487–618. https://doi.org/10.1086/660866.

- Gorur, R. 2011. “Policy as Assemblage.” European Educational Research Journal 10 (4): 611–622. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2011.10.4.611.

- Gourlay, L. 2021. Posthumanism and the Digital University. London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350038202.

- Gravett, K., and R. Ajjawi. 2022. “Belonging as Situated Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (7): 1386–1396. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1894118.

- Gravett, K., C. A. Taylor, and N. Fairchild. 2021. “Pedagogies of Mattering: Re-Conceptualising Relational Pedagogies in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education, Online First 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1989580.

- Hickey, A., and S. Riddle. 2022. “Relational Pedagogy and the Role of Informality in Renegotiating Learning and Teaching Encounters.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 30 (5): 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1875261.

- Hong, M., B. Lingard, and I. Hardy. 2022. “Australian Policy on International Students: Pivoting Towards Discourses of Diversity?” The Australian Educational Researcher 50 (3): 881–902. Online First. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00532-5.

- Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London, UK and New York, US: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2018. Anthropology And/As Education. London, UK and New York, US: Routledge.

- IPCC 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Summary for Policymakers. Accessed December 11,https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/.

- Larsen, M. A., and J. Beech. 2014. “Spatial Theorizing in Comparative and International Education Research.” Comparative Education Review 58 (2): 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1086/675499.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Leipold, S., P. H. Feindt, G. Winkel, and R. Keller. 2019. “Discourse Analysis of Environmental Policy Revisited: Traditions, Trends, Perspectives.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462.

- Lester, J. N., C. R. Lochmiller, and R. Gabriel. 2016. “Locating and Applying Critical Discourse Analysis within Education Policy.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 24 (102): 1–15.

- Levinson, B. A. U., M. Sutton, and T. Winstead. 2009. “Education Policy as a Practice of Power: Theoretical Tools, Ethnographic Methods, Democratic Options.” Educational Policy 23 (6): 767–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904808320676.

- Lewis, S. 2021. “The Turn Towards Policy Mobilities and the Theoretical-Methodological Implications for Policy Sociology.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (3): 322–337.

- Lomer, S. 2017. “Soft Power as a Policy Rationale for International Education in the UK: A Critical Analysis.” Higher Education 74 (4): 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0060-6.

- Madge, C., P. Raghuram, and P. Noxolo. 2009. “Engaged Pedagogy and Responsibility: A Postcolonial Analysis of International Students.” Geoforum 40 (1): 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.01.008.

- Maher, C., M. Hadfield, M. Hutchings, and A. de Eyto. 2018. “Ensuring Rigor in Qualitative Data Analysis: A Design Research Approach to Coding Combining NVivo with Traditional Material Methods.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918786362.

- Marginson, S. 2006. “Dynamics of National and Global Competition in Higher Education.” Higher Education 52 (1): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-7649-x.

- Marginson, S. 2011. “Higher Education and Public Good.” Higher Education Quarterly 65 (4): 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2011.00496.x.

- McCoy, K. 2014. “Manifesting Destiny: A Land Education Analysis of Settler Colonialism in Jamestown, Virginia, USA.” Environmental Education Research 20 (1): 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.865116.

- McKenzie, M. 2017. “Affect Theory and Policy Mobility: Challenges and Possibilities for Critical Policy Research.” Critical Studies in Education 58 (2): 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2017.1308875.

- Mulcahy, D., B. Cleveland, and H. Aberton. 2015. “Learning Spaces and Pedagogic Change: Envisioned, Enacted and Experienced.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 23 (4): 575–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2015.1055128.

- Nakata, M. 2007. Disciplining the Savages, Savaging the Disciplines. Canberra, ACT: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Noddings, N. 1995. The Challenge to Care in Schools: An Alternative Approach to Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

- OECD. 2018. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. Accessed July 16, 2022 from https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf.

- Ozga, J. 2021. “Problematising Policy: The Development of (Critical) Policy Sociology.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (3): 290–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1697718.

- Ozga, J., and B. Lingard. Eds. 2006. Globalisation, Education Policy and Politics. London: Routledge.

- Peck, J., and N. Theodore. 2015. Fast Policy. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Pederson, H. 2010. “Is ‘The posthuman’ Educable? On the Convergence of Educational Philosophy, Animal Studies, and Posthumanist Theory.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 2 (2): 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596301003679750.

- Peterson, B., D. Stuart, and R. Gunderson. 2019. “Reconceptualizing Climate Change Denial.” Human Ecology Review 25 (2): 117–142. https://doi.org/10.22459/HER.25.02.2019.08.

- Rabinow, P., and N. Rose. 2003. The Essential Foucault: Selections from the Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984. New York: New Press.

- Rizvi, F., and B. Lingard. 2010. Globalizing Education Policy. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203867396.

- Robertson, S. L. 2005. “Re-Imagining and Rescripting the Future of Education: Global Knowledge Economy Discourses and the Challenge to Education Systems.” Comparative Education 41 (2): 151–170.

- Rousell, D. 2016. “Dwelling in the Anthropocene: Reimagining University Learning Environments in Response to Social and Ecological Change.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 32 (2): 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2015.50.

- Savage, G. C. 2020. “What is Policy Assemblage?” Territory, Politics, Governance 8 (3): 319–335.

- Simpson, L. B. 2014. “Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3 (3): 1–25.

- Smith, L. T., E. Tuck, and W. Yang. 2019. Eds. Indigenous and Docolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View. London, UK and New York, US: Routledge.

- Snaza, N. 2015. “Toward and Genealogy of Educational Humanism.” In Posthumanism and Educational Research, edited by N. Snaza and J. A. Weaver, 17–29. 2015. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315769165.

- Snaza, N., J. A. Weaver, N. Snaza, and J. Weaver. Eds. 2015. Posthumanism and Educational Research. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315769165

- Stein, S. 2017. “Internationalization for an Uncertain Future: Tensions, Paradoxes and Possibilities.” The Review of Higher Education 41 (1): 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2017.0031.

- Stein, S. 2019. “The Ethical and Ecological Limits of Sustainability: A Decolonial Approach to Climate Change in Higher Education.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 35 (3): 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2019.17.

- St Pierre, E., and W. Pillow. 2000. Eds. Working the Ruins: Feminist Postructural Theory and Methods in Education. London: Routledge.

- Succi, C., and M. Canovi. 2020. “Soft Skills to Enhance Graduate Employability: Comparing Students and employers’ Perceptions.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (9): 1834–1847. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420.

- Tangey, S. 2014. “Student-Centred Learning: A Humanist Perspective.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (3): 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.860099.

- Taylor, C. A. 2018. “Each Intra-Action Matters: Towards a Posthuman Ethics for Enlarging Response-Ability in Higher Education Pedagogic Practice-Ings.” In Socially Just Pedagogies: Posthumanist, Feminist and Materialist Perspectives in Higher Education, edited by V. Bozalek, R. Braidotti, T. Shefer, M. Zembylas, R. Braidotti, M. Hlavajova, and R. Braidotti, 81–96. London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350032910.ch-005.

- Taylor, S. 2004. “Researching Educational Policy and Change in ‘New times’: Using Critical Discourse Analysis.” Journal of Education Policy 19 (4): 433–451.

- Tikly, L. P. 2004. “Education and the New Imperialism.” Comparative Education 40 (2): 173–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006042000231347.

- Tony Carusi, F. 2021. “The Ontological Rhetorics of Education Policy: A Non-Instrumental Theory.” Journal of Education Policy 36 (2): 232–252.

- UNESCO. 2021. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education. Accessed October 11, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379707.

- Verlie, B. 2022. “Climate Justice in More-Than- Human Worlds.” Environmental Politics 31 (2): 297–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1981081.

- Viswanathan, G. 1989. Masks of Conquest: Literary Study and British Rule in India. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Webb, P. T., and K. Gulson. 2015. “Policy Scientificity 3.0: Theory and Policy Analysis In-And-For This World and Other-Worlds.” Critical Studies in Education 56 (1): 161–174.

- Wildcat, M., M. McDonald, S. Irlbacher-Fox, and G. Coulthard. 2014. “Learning from the land: Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3 (3): i–xv.

- Wilkins, S., and J. Huisman. 2012. “The International Branch Campus as Transnational Strategy in Higher Education.” Higher Education 64 (5): 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9516-5.

- Xu, W., and K. Zammit. 2020. “Applying Thematic Analysis to Education: A Hybrid Approach to Interpreting Data in Practitioner Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920918810.