ABSTRACT

This paper explores how teacher educators in Norway discursively enact a policy framework for teachers’ professional digital competence (PDC) in the context of the digitalisation of education. This study draws on group interviews and focuses on how teacher educators understand and respond to the policy through practical argumentation. The paper identifies different variations and interrelationships in policy enactment and discusses the tension between a qualification-oriented and a critical-reflective perspective on PDC. This paper contributes to the literature on teacher educators and their enactment of education policy by highlighting the influence of beliefs and values and the wider context of teacher education. In particular, it highlights how the multiple professional roles held by teacher educators adds an additional level of complexity to teacher educators’ policy enactment.

Introduction

The promotion of digital technologies to transform education is a common practice globally and has been prominent within the educational policy discourse for decades (Facer and Selwyn Citation2021). In this digital transformation, teachers and teacher educators have been positioned as both the key actors and main obstacles (Bussesund, Engen, and McGarr Citation2023; Lund and Aagaard Citation2020; Nagel, Guðmundsdóttir, and Afdal Citation2023). The policies for the promotion of digitalisation are often based on neo-liberal concerns for enhancing economic competitiveness and data-driven and outcome-oriented educational systems (Høydal and Haldar Citation2022; Ljungqvist and Sonesson Citation2022; McGarr Citation2024; Pangrazio and Sefton-Green Citation2023).

The context of this study, Norway, has a comprehensive policy for the digitalisation of schools (Munthe et al. Citation2022). Norwegian educational authorities have stressed digital competence in a range of policy documents (Engen, Giæver, and Mifsud Citation2015; Erstad, Kjällander, and Järvelä Citation2021; Lisborg et al. Citation2021). In 2017, the Norwegian qualification framework for teachers’ professional digital competence was launched to guide and promote digital competence for in-service teachers (Kelentrić, Helland, and Arstorp Citation2017). In this regard, teacher education (TE) is also seen as important because of its role in qualifying teachers for digital schools. In the qualification framework, professional digital competence (PDC) is conceptualised to encompass a range of knowledge, skills and attitudes.

In the context of TE, student teachers are expected to enter the profession with the competence to teach digital technologies. Previous research has explored teacher educators’ digital competence and whether they can provide student teachers with satisfactory digital competence as part of the initial TE programmes (Nelson, Voithofer, and Cheng Citation2019; Røkenes et al. Citation2022; Starkey Citation2020). A common theme in these studies is the need to strengthen student teachers’ digital competencies.

This study examines the PDC framework as a policy document. Although qualification frameworks are not typically considered policy texts, following Bacchi (Citation2009), viewing them as policy documents can provide a deeper understanding of their content. Firstly, the PDC framework is considered a proscriptive text that outlines the skills, knowledge, and competence of an ideal PDC teacher (Bussesund, Engen, and McGarr Citation2023). Secondly, the framework was published by the Norwegian Directorate of Education and was accompanied by an implementation scheme for teacher education in Norway in 2024. Therefore, the study investigates how teacher educators respond to the PDC framework (Kelentrić, Helland, and Arstorp Citation2017) in relation to the role of TE in the digital transformation agenda for schools. With the analytic focus on how teacher educators as policy actors shape PDC for TE by asking ‘How do teacher educators understand and respond to PDC as a policy in their professional practice?’.

Teachers’ professional digital competence

Digital skills play a central role in the national curriculum in Norway (Engen, Giæver, and Mifsud Citation2015) with several initiatives aimed at digitising schools and promoting digital competence among teachers and pre-service teachers (Munthe et al. Citation2022). These strategies are often linked to broader economic and ideological goals, such as economic competitiveness and 21st century skills (Reeves and Drew Citation2012). A common narrative of these policies is the ‘challenges and opportunities’ associated with the digital society and harnessing its potential, both socially and economically.

Previous research has highlighted that teacher educators need continuous professional development in PDC (Amhag, Hellström, and Stigmar Citation2019; Instefjord and Munthe Citation2016). Nagel (Citation2021) has pointed out that there is no consensus on the required knowledge and skills for teacher educators’ digital competence. Her analysis of the teacher education curriculum showed that there is a greater emphasis on digital tools and managing teacher workload over supporting learning. According to Lund and Aagaard (Citation2020), at the formal local curriculum level, TE needs to gain a deeper understanding of the role of digitalisation in society and the consequences for epistemic practices. In terms of digitalisation of the education system, the focus among teacher educators generally is often on tools, seen in relation to teacher educators’ agentic power (Nagel, Guðmundsdóttir, and Afdal Citation2023).

Globally, there is an agreement amongst policy makers and scholars about the importance of developing teachers’ PDC (Erstad, Kjällander, and Järvelä Citation2021; Facer and Selwyn Citation2021; Ilomäki et al. Citation2016; McGarr Citation2024), yet to date, little attention has been paid to the enactment of PDC in TE.

Policy enactment in teacher education

Building upon Braun et al. (Citation2011) study, we apply their analytic lens towards teacher education by considering teacher educators as policy actors (Ball et al. Citation2011). Although Braun et al. (Citation2011) did not specifically address the context of TE, several studies examined policy enactment in higher education, professional development and TE. The reconfigurations that teacher educators do when deliberating about policy (Chiang et al. Citation2023; Singh, Thomas, and Harris Citation2013), and teacher educators’ enactment of policy (Aydarova, Rigney, and Dana Citation2024; Lambert and Penney Citation2020; Sin Citation2014), are critical in understanding policy work done by teacher educators (Lambert et al. Citation2021; Watson and Michael Citation2016). This research focuses on how teacher educators discuss their professional practice in enacting policy. Specifically, it examines how teacher educators deliberate on PDC framework using practical argumentation theory, treating it as a form of political discourse and policy work (Fairclough and Fairclough Citation2012).

Teacher education as a profession

Fenwick (Citation2016) observed that professionalism is a complex and multifaceted concept that varies across professional groups. Teacher educators are a diverse professional group that blends various epistemic cultures, identities, and roles. They have been seen as teachers teaching teachers, subject experts, or researchers (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2020; MacPhail and O’Sullivan Citation2020; Orland-Barak and Wang Citation2021; White Citation2019). If one is studying policy enactment in this context, it is essential to be sensitive to these aspects and recognize the multiple roles that teacher educators play. Concerning the ongoing debate about digital competence in education (Erstad, Kjällander, and Järvelä Citation2021), this complexity is evident in the diverse perspectives held within the teacher education profession (Johannesen and Øgrim Citation2020; Nagel, Guðmundsdóttir, and Afdal Citation2023; Örtegren Citation2022).

TE and teacher educators have come under increased scrutiny by international policy makers and researchers, however, the definition and identification of this occupational group have become more challenging (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2020; White Citation2019). In terms of university-based teacher educators, Griffiths, Thompson, and Hryniewicz (Citation2010) indicated that there are two sub-groups: one entering from a school as a teacher, the other from an academic/research discipline. Thus, these different identities raise questions about whether TE is a profession or an occupational group, creating tension between ‘teacher experience’ and ‘academic qualification’ (White Citation2019).

White (Citation2019), claims that teacher educators lack a sense of ownership over their profession because of the absence of a shared professional identity and clearly defined roles. Consequently, they are at risk of being overlooked by reformist agendas that do not consider the opinions of those who have long been involved in TE and who advocate for a social justice agenda. This leads to debates about their professional status as teacher educators. By investigating the understanding and response of the PDC framework among teacher educators, this paper focuses on the way in which, and the means through which, teacher educators enact policy in their context.

Policy enactment

In contrast to a policy implementation, policy enactment involves various institutions and actors, and policies are often contested concepts that are influenced by state action, institutional circumstances and different argumentative discourses (Braun et al. Citation2011). According to Ball et al. (Citation2011), teachers play a significant part in this process as ‘policy actors’, through different roles, actions and engagements. Policy enactment is a fluid process that requires policy enactment through discursive acts.

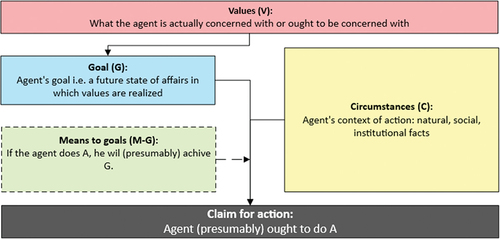

This paper is concerned with policy enactment through discursive acts (i.e. through talk and text) and elaborates on the practical reasoning of teacher educators by using a discourse analytic approach (Fairclough and Fairclough Citation2012). To operationalise this approach, the analysis involves identifying the goals, means to goals, the circumstances and values that emerge when the participants discuss PDC in TE. While explicit teacher values may not be apparent in this conversation, it can be reasonably assumed that the way in which they frame the goal, given the circumstances they describe, is a good indication of their values as educators. By applying practical argumentation, this study investigates how policy actors do discursive policy work by constructing different ‘claims for action’, based on the construction of different policy imperatives. Fairclough and Fairclough (Citation2012) proposed four categories for structuring the analysis of the ‘claims for action’ ().

Figure 1. Proposal for structure of practical argument (Fairclough and Fairclough Citation2012, 45).

This study enhances knowledge of how teacher educators do policy work to shape digitalisation policies through discursive enactments in a deliberative process. It contributes to the body of policy research that seeks a more nuanced understanding of policy context (Ball and Grimaldi Citation2021; Reeves and Drew Citation2012; Singh, Thomas, and Harris Citation2013; Webb and Gulson Citation2012).

Method

This study used group-interviews with teacher educators in four Norwegian universities/university colleges to explore how they justified their practices as teacher educators in the context of the digital transformation agenda. Furthermore, it uncovered the justifications they provided for their positions as teacher educators within the broader discourses surrounding digitalisation and professional identity. The focus was on how teacher educators are situated within the policy context and how policy actors do ‘policy work’, articulating arguments and justifying practices in the preparation of pre-service teachers.

Four universities, in recent receipt of Norwegian Directorate of Education funding to implement the PDC framework in their TE programmes, were invited to participate. Through contact with the project leaders, relevant faculty members were identified and invited to participate in the focus group discussions. A total of 58 teacher educators were invited through this process, and 22 participated. Out of the five eligible TE programs, four of the institutions responded and four group interviews (one per institution) were conducted. The strategy was to recruit a diverse group of participants, considering factors such as subject expertise, career paths and experience. The group that responded appeared to be diverse. The participants (10 men/12 women) were at different career stages with seven having less than 10 years of experience, and six having more than 10 years of experience. See for descriptions of the participants in the study. The participants were anonymised and coded after completion of the interviews. As an example, TE1- PTU refer to one of the participants form The Pine Tree University, all university names are fictitious to maintain anonymity.

Table 1. Overview of participants.

The interviews were centred around the participants’ experiences and work with PDC in TE, allowing them to construct practical arguments based on their conceptions of PDC. The interviews allowed the participants to discuss their conception of PDC and the enactment of the PDC framework in their institutions. By organising group interviews, the study promoted discussion facilitating the construction of different claims about PDC in TE. These discussions were chosen as the unit of analysis since they captured the enactment and negotiation of PDC in teachers’ work. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed using qualitative data analysis software. The recordings were reviewed multiple times, and the data were further coded and organised during the analysis. The interviews were conducted in Norwegian, and the selected excerpts below were translated by the authors. Each interview started with the following question below and follow-up questions, while guided by the semi-structured interview guide, responded uniquely to the development of each individual conversation:

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training’s framework for teachers’ professional digital competence states that ‘The teacher’s professional digital competence is a dynamic and complex competence that is affected by developments in society’. How do you understand professional digital competence, as teacher educator?

The analysis was conducted in three steps. The first step was based on Ball et al.’s (Citation2011) taxonomy of policy actors, with the aim of identifying reoccurring policy work done by teacher educators. Secondly it involved investigating the participants’ discursive enactment of the policy; through applying Fairclough’s and Fairclough (Citation2012) practical argumentation theory, which emphasises discursive acts and how individual experiences are shaped by the larger social and political environment. Finally, the variation and similarity across the interviews were discussed.

The excerpts in the findings represent the recurring claims given by the participants. In the first part, the policy work done across the interviews is described (Ball et al., Citation2011a). The main selection criteria for a closer analysis were instances in which circumstantial and goal premises were re-accrued across the interviews; thereafter, the ‘claims for action’ using practical argumentation theory was explored (Fairclough and Fairclough Citation2012). The excerpts were used as analytic tools to exemplify broader trends across the interviews and were chosen based on their illustrative power and variation. See for a description of the analytical steps for operationalisation of the analytical framework.

Table 2. Analytical framework for exploring policy enactment.

Enactment of PDC

Initially, the interviews were open-coded to identify the topics and concerns raised during the discussion. The categories were constructed through iterative processes in which the initial 65 codes (1587 code elements) were reduced to 29 (1090 by removing duplicates and discussing the meaning of utterances). Next, the different codes were analysed for aspects of policy work. In this process, three policy actors in the data were identified: Narrators of policy, critics of the sociotechnical landscape and the innovators of teacher education (). These categories were used as holistic devices to recognise how teacher educators understand and respond to the policy. These policy actors were not seen as mutually exclusive, but as a discursive construction that teacher educators use when arguing for their understanding of PDC. For clarity, Braun et al. (Citation2011) taxonomy of policy actors was followed.

Table 3. Inductive coding policy enactment.

Narrators of PDC

As policy narrators, the teacher educators focused on selecting and interpreting policy and filtering out what they found useful. A recurring narrative that the participants used when discussing PDC was connecting the themes ‘teachers’ professional competence’ (in a broad sense), ‘pedagogy’ and ‘subjects’. When discussing teachers’ competencies, there was a common response to the need to change the teacher’s role from an ‘arbiter of knowledge’ to a ‘curator of knowledge’. As a teacher educator formulated,

TE5-PTU: The paradigm shift amplified by digital technology is both exciting and challenging. We’re transitioning from knowledge domains to competence domains. In competence-based curricula, the focus is now on what students should be able to do, not just what we convey as teachers. In teacher training, we must prioritise developing competencies in student teachers.

The concept of paradigm shift was used as a narrative tool to emphasise the need for developing student teachers’ skills to qualify as professionals to meet the requirements and expectations in accordance with the competence-based national curriculum introduced for Norwegian schools in 2006. The 2006 curriculum reform also amplified a student-centred learning approach legitimised within a progressive pedagogy framework. Pedagogy was another central theme across the interviews.

TE4-UoN: In a technology-rich society where most things happen online, etc., we are invited to learn by ourselves. At the same time, when we are introducing new learning platforms for teachers, we are often asked which buttons to click to accomplish this or that. So, I believe, the tensions are not the technical, but whether you are trained to be instructed or to figure it out for yourselves.

The narrative about the digital society in constant change is here connected to a need for pedagogical models that train learners to explore and discover learning needs and how to apply their competences in different changing contexts. Progressive pedagogies were something they all related to when describing the situation around teacher training and practices in schools.

A third theme that occupied much time in the discussions was the role of subjects in this progressive pedagogical imperative. While some teacher educators emphasised the need to integrate digital technology into the subjects, others were more concerned with organising digital competence as a cross-curricular theme.

TE-4 UCC: When you speak about how you teach computer science in Germany, which is a subject where students learn programming, while in Norway it represents just something extra in a way – just an additional tool. And that makes the recognition of a subject complex, and it makes the job with digitalising teacher education difficult – because we have other subject areas that are supposed to be digitalised. To what degree one succeeds, making us digital competent teacher educators or preparing digital competent teachers, is also a part of the picture.

Here, the policy narrative is connected to a broader discourse of having computer science either as a cross-curricular theme or introduced as an independent subject.

Looking at the policy narrator’s practical argumentations in connection with ‘circumstance’, ‘goals’, ‘values’ and ‘means to goal’ when discussing, the theme ‘being up to date’ emerges as both crucial and problematic for teacher educators. In the context of policy narration, the circumstance of policy is enacted through reference to both discursive policy, such as the PDC framework and curriculum, and technological infrastructure, such as the 1:1 device scheme and lived policy, experienced through working in TE. The narrator focuses on keeping abreast of the technological development in classrooms. The focus lies in the influence of the devices in school or the everyday applications pupils use, which could be described as the sociotechnical infrastructure of education and social life. This was seen as just as influential as discursive policy, such as the PDC framework and other digitalisation policy documents.

In the context of the digital transformation agenda, digitalisation is presented as a ‘paradigm shift’. An issue that was stated by several participants was that of a ‘rapid pace of change’ in the educational circumstance, exemplified below.

TE4-PTU: We’re not always at the forefront of technology in schools, and it can be difficult to keep up with the rapid pace of change. Sometimes I worry that what I’m teaching my students will be outdated by the time they become teachers. Our expertise is constantly evolving, and it can be challenging to stay current with all the changes.

The idea of staying ‘up to date’ was presented as a premise in the interview.

The policy narrators often saw this as a challenge to select certain aspects of their practice and to legitimise them as part of a wider policy push. As seen in the excerpt above from TE4- UCC and TE4-PTU, there was a tension between equipping students with skills for the present while also preparing them for an unknown future. In summary, the narrators of PDC aim to align their work with the policy goals and legitimise their practices by keeping TE up-to-date.

Critics of the sociotechnical landscape

Turning to policy critics, the analysis focused on the counter-discourses constructed by the participants. A recurring counter-discourse comprised the themes ‘professional judgement’, ‘policy’ and ‘resistance’, which were mostly discussed in relation to schools’ socio-technical environment and teachers’ work conditions. Several participants focused on preparing student teachers to become critically reflective teachers who could assess the claims made by EdTechs or policy makers. They stressed the need for a good foundation for critics, often conceptualised as the sociotechnical landscape. This encompasses the technical infrastructure, social organisational and beliefs about what transformational impact digital technology can have in education. The excerpt below is an example of a critic of the sociotechnical landscape, particularly how ‘no one asks the teacher’.

TE3-PTU: They are given specific tools to work with, but it is not always the best choices for the subjects or didactic design. These decisions are made by someone else without considering their needs. Why should every student have one-to-one coverage with the same device?

TE4-PTU: Exactly. And what kind of device will it be? A PC, Chromebook, or iPad? No one asks the teachers what is appropriate for the classroom. They just buy whatever is the best offer or what the municipal politician decides.

TE3-PTU: Right! Now everyone has an iPad, for example. I’d rather see fewer iPads per class and a variety of tools available.

TE4-PTU: Yes, having both would be ideal. iPads, PCs, and Chromebooks could all be used interchangeably between classes, and of course not at all.

As seen from the conversations, teachers’ professional judgement has no influence on the choice of digital technologies. Teachers’ professional autonomy, particularly in fostering critical reflection, is seen by the teacher educators as crucial to maintaining teachers’ professionalism. The dialogue above can also be seen as a counter-discourse to how such governing strategies, which take place in the municipalities, lead to a de-professionalisation of teacher’s pedagogical work. Consequently, the teachers experience less methodological freedom in choosing the right strategies for supporting teaching and learning. The strict and detailed regime on deciding which digital technologies, framed in progressive pedagogical terminologies, have the opposite effect by hindering teachers’ creativity and pedagogical innovations.

Regarding ‘policy’, the policy critics focused not only on discursive policy but regarded digital infrastructure and apps as part of the governing regime. In relation to this, the ‘resistance’ to this system was not only understandable but, at times, regarded as necessary. An example of this can be seen in the excerpt below, where TE1-UoP and TE5-UoP problematise that teacher educators are ‘locked out of’ the digital system in the school.

TE1-UoP: There are many digital systems in the school that we are locked out of. Before digitalisation, you could sit and analyse textbooks, but now they’re behind ‘paywalls’. There’s a lot of licences and digital textbooks and other services which are unavailable to us in teacher education, and that’s problematic, because ‘silos’ are developing out there in schools that aren’t easy to access, and it limits our work as a teacher educator.

TE5-UoP: Yes, exactly how much policy and how much ideology are put into the term PDC or market for that matter. I’m not sure how much knowledge-based or research-based thinking is behind it and how much in a way are societal changes and market forces is behind it. I think maybe that, we’re still in that kind of policy implementation phase, which is being exploited by a discourse of change, without necessarily being critical of what change. And it affects the whole sector, how those perspectives are pushed. How these EdTechs and publishers imagine their products. At least when they push their products on these, I was about to say, ICT trade fairs … As I see it, it is quite sad. In relation to the view of learning behind it. Contrary to this, as you say TE 2, how do we realise opportunities for much more dynamic, engaging, and creative learning? But what we end up in is a more controllable learning, more individualised learning, as a result.

The concerns of TE1 reflect a discourse of digital enclosure, and TE5 follows up and questions the scientific bases and the solutions they provide. The concern of market forces and the ‘pushing’ of the digital imaginary by EdTechs and publishers is seen as something to be resisted. Rather than promoting engaging and creative learning, one often regards this ‘digital change agenda’ as promoting more individualised and controllable learning. Policy critics are critical of the positive and optimistic claims made by EdTech’s, publishers and policymakers. On the contrary, given their experience of the introduction of digital technologies in schools, they do not share the optimism that is present in advertisements and policy. They see their roles as TEs to promote a counter-discourse to the prevailing ‘digital change agenda’ prevalent among municipalities and commercial actors.

Looking at the policy critics through practical argumentations, the social imperative is often mobilised, i.e. addressing the need for student teachers to be able to critique the influence that ‘bigtech’ have on the development of schools. An example of this is the need to critique technical solutions, and they see their role as providing this critique. The structure of the TE programme can also be a barrier to the development of critical reflection, as there is ‘no time’ for it, resulting in digital technology being instrumental. The excerpt below illustrates that the concern about ‘market-driven’ logics influences how technologies are understood and used.

TE4-PTU: One challenge we face is that technology is often market-driven. Companies push their products, touting the enormous opportunities for collaboration and co-creation. While this can be exciting, it can also be problematic when we have 30 students in a classroom; each focused on their own screen instead of interacting with each other. Yes, it is concerning that we are so reliant on screens for collaboration, even when we are physically in the same room and able to interact directly. There is something sick about that.

TE3-PTU: Why do we always talk about one-to-one screen usage? It doesn’t have to be. When I use digital tools with my student teachers, we rarely work one-to-one. We usually sit together and talk using a shared screen. This allows us to do things we might not have done otherwise and adds value to our collaboration. Screens can facilitate group work and collaboration, not just individual work.

The circumstances described by teacher educators are ones in which, first, they must work within shared understandings of what teaching with digital technology is and, second, they must obtain the relevant resources such that they feel it is their job to critique through paywalls and IT security systems. The context in which this assertion is made relates educators to the perception that TE should ‘respond’ to how digital technology is being introduced into schools and that it requires institutional change to meet the challenge. At times, the digital tools that are socially constructed function as a prerequisite for preparing student teachers for the future. This position is well summarised in the excerpt below;

TE4-UCC: The digital society sets the stage for development. We have created this society, and it has given us new ways of working and collaborating with tools like algorithms and AI. These tools affect how we work and learn, so it’s important to understand their impact. Teachers have two tasks in this regard. One is to prepare learners for the digital society by expanding their digital literacy. The other is to understand how learning processes work in a digital society so that we can use digital tools meaningfully in our teaching.

The policy critics reflected on the use of the PDC policy to address concerns about the undue influence that competency has had in shaping how digital technologies are used and understood, in contrast to what they experience when analysing or interacting in the context. The circumstantial premise was often that of societal pressure that schools, teachers and teacher educators alike must deal with. The goal, even of policy critics in this case, is providing an education that is responsive but not blindly accepting changes happening in education due to the digitalisation of society.

Concerning the values that are brought up in this context, the participants prioritised the preservation of teachers’ autonomy, especially when it comes to their work methods. The excessive influence of digital technology is seen as an encroachment of teachers’ work, particularly their democratic duty. As such, by providing ‘legitimate’ criticism, these policy actors use ideas of the ‘teacher as a guardian’ to situate digital technologies as a problematic entity that teacher educators need to address.

Innovators of teacher education

The final group of actors that emerged were the innovators of teacher education, identified as policy entrepreneurs in the inductive coding. They initiated institutional change and focused on enhancing the credibility and authority of digital practice in their programmes, often campaigning for PDC to focus on their work and experiences teaching in digital reality. In analysing the data, the themes connected to ‘innovation’, ‘institutional change’ and ‘toolbox’ were most prominent. These themes argumentatively presented in a sequential manner that innovation should be the basis for institutional change, thereby creating a toolbox for a mindset change among fellow teacher educators. To promote innovation, the policy entrepreneurs indicated that the policy enabled them to engage student teachers and make their teaching more relevant to digital classrooms. The mindset should be changed from an instrumental tool-based focus to emphasising the need for a professional pedagogical approach, as exemplified below.

TE2-UCC: When we received funding for our project and presented it to our colleagues, their first question was ‘Great, we have almost 30 million. What can we buy?’ Our response was ‘Nothing, the project buys your time’. From the beginning, we set the premise that our focus wouldn’t be on buying tools and software, but on developing expertise, teaching competence, and reflection. We aimed for a more nuanced approach to using digital resources in teaching and in general. Whether or not we succeeded is another matter.

When considering PDC in TE, the focus was on developing teacher educators’ attitudes and not on buying new technology. The ‘nuanced’ approach involves developing a ‘digital’ teacher educator that has the expertise required for the 21st century. The participants commonly downplayed the importance of technology; focusing instead on institutional change by creating a space in which teacher educators could engage with new technology in creative and engaging ways.

When discussing innovation in TE, the theme of developing a ‘toolbox’ of digital technologies was often highlighted. The toolbox was not only conceived of as particular hardware or software but as an intellectual toolbox of experiences that teacher educators should provide to their student teachers. The conceptual shift was not aimed at working with specific technologies but at focusing on the principles for digital technologies in teaching.

TE5-UoC: It strikes me that, in all those years it has been here, digital competence went from being imposed on both teachers and students in Norwegian schools. It was like creating a learning goal for students to learn how to be good at jigsaws, but jigsaws are just a tool to be able to make some. Now we have concluded that we would rather the students have a repertoire of digital tools that makes it easier for them to choose the best tool for the job. My goal is to build that toolbox and give students the ability to switch to whatever tool they need for the job.

TE1-UoC: I believe that the concept of the enthusiast, like [TE2] mentioned earlier, is still very much present here. Some of us are more willing to try new things, organize and manage, while others are less enthusiastic. However, it is structurally more challenging to achieve what you (TE5) aim for and build that toolbox if the main body of faculty staff is not involved.

In this excerpt, the toolbox represents the symbol for the institutional transformation that TE should pursue. By using the metaphor ‘toolbox’, the entrepreneurs focus on the teacher as the one who chooses appropriate tools. The toolbox is not an individual concept but a shared understanding of the use of digital tools in teaching. Entrepreneurs focus on systemic changes to adapt and innovate when confronted with what they often describe as conservative teacher educators. They see it as their task to convince their colleagues to embrace digital work methods.

To achieve this change, the development of a ‘learning lab’ was conceived as a space in which such institutional work could start. By creating a space for digital technology, the policy entrepreneur can ‘invite’ student teachers and teacher educators to experience the potential in digital development. A dissemination model through student experience is used to build acceptance among colleagues. This is exemplified below, where the teachers were designing their own learning lab.

TE1-UCC: The idea is that you can explore, with pedagogy or subject didactics as a starting point. The interaction between subject didactic, ethical, and attitudinal and technical dimensions, and the goal, of course, is that you reflect on all that at once, but at the same time. I don’t know what you can do with a micro:bit, unless I know what micro:bit is.

The learning lab will be centred around the student-teacher practicum, so that there will be teacher-students who will then work in practicum with teachers who have this practice with technology and pedagogy and can exchange knowledge and experiences. And there-after the students-teacher share their experience and maybe start pushing teacher educators who may be more inclined to be curious about the learning lab.

When discussing learning labs, the emphasis was on how experience with digital technologies can promote institutional change and practice. In the excerpt above, the experience with digital technology and a focus on the student teachers’ practicum are considered to have the potential to make institutional change. Their strategy was to use practicum as a catalyst for changing their colleagues’ attitudes towards digital technologies in teaching, hence disrupting the habitus of the teacher educators.

When analysing the practical arguments of policy entrepreneurs, the need for innovation is imperative to transform how TE is associated with digital technologies. The most frequently cited circumstance was changes to in-service teachers’ working conditions, thus making innovation crucial for TE with the intention of maintaining relevance. The driving force behind innovating with digital technologies in TE was the inability to keep pace with the developments occurring in schools. While schools have been progressive and able to adapt to technological changes, TE has remained self-centred and conservative. Therefore, the participants’ goal is linked to the experience and expertise of in-service teachers to guide their work in TE. In this context, the focus is on foregrounding values that disrupt stagnated mindsets in the hope of changing the teacher educators to become pro-active creators of digital content.

Policy entrepreneurs are not uncritical of PDC in TE, even though they advocate for its adoption. They acknowledge the challenges posed by the growing ‘platformisation’ of education, as indicated by some policy critics in this study. In the excerpt below, concern is expressed when discussing the possibilities for teacher innovation and what technologies are available to in-service teachers.

TE2-UoP: I find it important to reflect about what technology is in schools. Even though we have that PDC framework, the publishers and other big players have also provided us with what they consider good technology for education. This is something I focus on in my teaching. I think that in-service teachers today, even if you have the framework, are put in a split between established, safe, credible digital tools from publishers instead of being able to focus on new technology and other ways of using technology. And quite often it boils down to costs. In terms of the framework’s focus on leading learning processes, creativity in relation to core elements. It all is a bit vague, and it is hard to find the balance between the creative, exploratory versus the safe route that publishers provide.

This excerpt compares the creative and exploratory approach with the safe and traditional approach in the context of the PDC framework. The entrepreneurs argue that the framework does not put enough emphasis on these aspects of teachers’ work. Therefore, it is the teacher educators’ responsibility to foster these innovative practices based on the professional exploration of digital technology for the student teachers. The goal is to maintain the professional teachers as the innovators of pedagogical practice and resist the ‘pre-packed’ educational material.

The innovation imperative has two purposes. It highlights the need for TE to remain relevant to in-service teachers by offering innovative practices to strengthen teacher autonomy and it seeks to gain legitimacy in TE by focusing on in-service practice. The means to achieve these goals involves exposing teacher educators to digital technologies and in-service teachers’ digital practises. Furthermore, it encompasses building an institutional space for exploring digital technologies.

Discussion

While analysing the cases, positions were adopted. Among the policy narrators, there was an imperative to use digital technology to promote progressive and student-active learning. Among the policy critics, professional judgement was seen as the ability to critically scrutinise technological development and adaptation in schools. Finally, the policy entrepreneur understood that TE could provide student teachers with a toolbox.

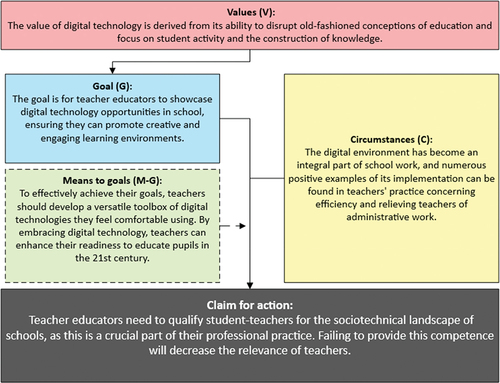

The first identified claim for action among the policy entrepreneurs was related to the goal of qualifying digitally competent teachers, which was situated in the context of policy imperatives and school imperatives ().

The task of teacher educators is to showcase the potential that digital technology can offer in the classroom and promote active methodologies to prompt creativity and facilitate engaging learning environments. The teacher’s expertise lies in assessing the pedagogical value of the different technologies used in the classroom. The position emphasised the centrality of the teacher’s judgement as to which technologies were pedagogically appropriate to use in school.

The teacher is seen as a curator who uses technology to enable pedagogically reasonable actions, either as an artefact used by students and teachers to mediate learning activities and foster learning communities or legitimised by a social materialist approach that emphasises how the interaction between human and material aspects of the learning environment constructs a new reality in which the teacher’s role is to curate and evaluate learning experiences. Teacher educators become facilitators who can qualify teachers for a given reality that they need to prepare for.

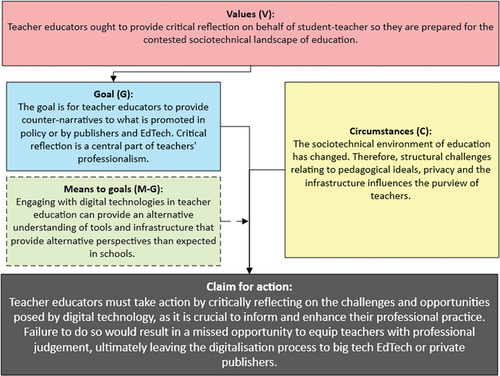

The second claim for action identified concerned the development of critically reflective professionals situated within the context of societal and school imperatives ().

Within this context of an increasingly digitised society and school, the participants identified the role of teacher educators in promoting values that were seen as intrinsic to the teacher as an advocate for the rights of their students or as an activist defending the role of the teacher in the face of political pressures for increasing digitalisation. As highlighted in the policy critics, the participants maintained counter-discourses to the perceived pressures of digitalisation by selecting aspects of the PDC framework that emphasised advocacy for either pupils or student teachers.

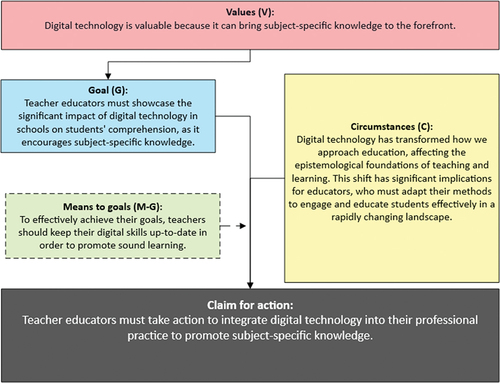

The third claim for action was identified among the policy narrators, who were concerned with aligning subject-specific knowledge with the epistemic changes that have occurred with the digitalisation of society ().

As such, the goal is to develop future teachers that primarily focus on subjects that are empowered by digital technology. The claim for action is understood in positive terms as supporting teachers in delivering subject-specific knowledge. The task of the teacher is to stay up-to-date so that they can provide the best possible education for their pupils. As such, the task of teacher educators is to promote their subjects. A PDC teacher is the one who can utilise digital technology to promote deeper understanding of the subject and enhance their subjects in school.

The three identified ‘claims for action’ highlight some of the contradictions that teacher educators need to deal with when educating student teachers. On one hand, it is to qualify and promote certain practices, either seen in pedagogical or subject-specific terms, where the duty of teacher educators is to fulfil policy and to promote best practice. On the other hand, it is to examine the assumptions underpinning the digital change agenda and critically engage as a professional with changes to the sociotechnical work conditions of teachers.

During the policy deliberation, the participants put forth different circumstantial and goal premises. These positions were not fixed but changed during the discussion, reflecting the multiple roles, identities, and contexts that teacher educators inhabit. When considering the policy work done by teacher educators, competing goals and circumstantial premises reflect different value judgments and the composite character of teacher education.

Among the participants, several positions were taken when enacting the policy, but a common concern was how to grapple with the changing sociotechnical landscape of education. When considering the qualification claim, the participants emphasised building professional knowledge and experience that expand their professional agency, which is in line with the findings concerning the extent to which PDC is addressed in TE (Nagel, Guðmundsdóttir, and Afdal Citation2023; Novella-García and Cloquell-Lozano Citation2021; Örtegren Citation2022). The scholarship often fails to highlight the critical reflective attitude towards digitisation as a part of PDC.

What is argued for by teacher educators may be understood from two perspectives. First, it can be discussed from an individual and attitudinal perspective, where PDC development is seen as disrupting ‘traditionalist’ educational practices in TE. From this perspective, it is often seen as convincing colleagues about the merits of digital tools and the impact that digitalisation has on society, often discrediting resistance as being ‘conservative’. Second, PDC can be discussed from a systemic and critical perspective, not discrediting the potential of digital technology or their impact but focusing on providing student teachers with relevant criticism that is important to maintain professional autonomy. The tension between this position and the participants’ movement between the discursive enactments highlights how both positions have residence among the participants, and as such, are part of the deliberation among the participants. This assertion avoids competence concerns and instead emphasises teacher educators as protectors of the profession, while addressing the influence of publishers’ and EdTechs’ view of educational digital technology. This provides a rich understanding of how PDC is understood by different stakeholders.

This dual focus on ‘qualification for’ and ‘critical reflection of’ the digitalisation of schools highlights the complexities teacher educators deal with when enacting PDC. On one hand, they are often placed in a position of becoming technology promoters, where they engage with discourses of progressive pedagogic and student-active learning. On the other hand, they problematise this position, as they do not want to be seen as being subservient to one view of digital technology for education. By considering teacher educators as policy actors, this study has shown how the PDC concept is a contested term even among the teacher educators who have worked on implementing it. It is important to note however that the tensions between the focus on equipping student teachers with relevant skills to capitalise on the affordances of technology and the focus on developing student teachers’ abilities to critically reflect on digital technology does not suggest that teacher educators align with one position or the other. Throughout the discussion, several issues were brought up, but a recurring theme across the cases was the concern for ‘dealing’ with a sociotechnical landscape that influences how teachers work.

In this study, the participants’ speech acts in group discussions were analysed. Though this cannot tell anything about what the participants do in practice, it can indicate their reasoning and how they understand and respond to the policy. As different claims for action are proposed, teacher educators in these cases develop a movement between roles to problematise different aspects of the policy context. This highlights that teacher educators are not naïve actors; they are creative and sophisticated when discussing teacher professionalism and the influence of digitalisation policy on education. When considering the enactment of such a policy, the active role of teacher educators should be considered. Apparent resistance to the effects of digitisation has often been conceived as ‘conservative’ or as a lack of knowledge on behalf of teacher educators, but this study shows that this perspective cannot be so easily discounted when considering teacher educators as policy actors. Rather than focusing on knowledge, skills and competences, this study suggests that the question of values is just as important.

Implications and conclusion

The teacher educators expressed different understandings of what it means to educate a PDC teacher by constructing different claims for action. These different discursive enactments are tied to the complex institutional context of TE because they point to the different characteristics of being a teacher educator. Like school teachers, teacher educators are used to dealing with shifting political winds and countless policies being implemented in their institution (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2020). This study of policy enactment in teacher education sheds light on how qualification frameworks act as policy in higher education.

Policy is not blindly rejected or accepted by teacher educators but instead serves a specific imperative they construct. This leaves teacher educators, at times, dealing with a conflict. Firstly, teacher educators embrace PDC to disrupt outdated pedagogical practices and strengthen subject-specific knowledge. Secondly, they maintain a professional critical reflective distance from such policy-driven agendas coming from the outside of TE. Thirdly, they work aligning PDC with other goals in teacher education such as curriculum alignment and meeting the pressure of teachers’ work life reflecting the multiple roles and identities that teacher educators inhabit. Lambert and Penney (Citation2020) highlighted how teacher educators, as policy actors, work ‘amidst policy’ to do purposeful work as teacher educators. Likewise, in this research, the participants’ movement between different practical arguments can be seen as the policy work in a complex institutional context, when enacting a policy in a collegial space incorporating multiple professional roles.

The deliberation and critical questioning introduced by the different views on how teacher educators engage with the policy is evident. The implications of the ‘digitalisation of education’ as it is represented in the Norwegian PDC framework are not something that is tacitly rejected or embraced by teacher educators. This highlights the ‘policy work’ (Ball et al. Citation2011) that teacher educators do when they understand and respond to the policy. Experts in teacher education often create various ‘claims for action’ while implementing policies. Moving between different enactments can be viewed as critical questioning and deliberation. As such, the tension between enactments can be better understood in political terms rather than incoherence, as it raises important questions about the purpose of teacher education. Specifically, it prompts consideration of whether teacher education is solely focused on technical competence or encompasses values instilled in future teachers.

Considering the reconfiguration that the teacher educators do when deliberating policy (Chiang et al. Citation2023), practical argumentation theory contributes to the understating of the policy work done by teacher educators, particularly in highlighting how goals and values are continually shifting in the context of the circumstances evoked. As such, the ‘call for action’ that teacher educators employ not only relies on the circumstances and values of the teacher educators, but also the multiple professional roles that are in play in teacher education.

When considering qualifications frameworks, it opens up seemingly neutral improvement projects as a point of deliberation. That is, when teacher educators respond to such policy, they recontextualize the policy to fit their context.

TE has been the site of contention for diverging political and professional agendas (Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2020; Ellis, Souto-Manning, and Turvey Citation2019; Fenwick Citation2016), from dealing with ecology questions, psychosocial, diversity and, in this case, digitalisation. The diversion between policy and practice and differing political and professional agendas is often seen as a problem with TE. In an institutional context, with multiple professional roles, policies like the PDC framework go through several rounds of interpretation, which can lead to conflicting claims for action. Rather than considering this as a weakness of policy or the lack of teacher educators’ skills, knowledge, or attitudes, it reflects the messy context of TE.

We need to question whether an individualised policy places the sole responsibility of dealing with complex institutional change issues on teacher educators.

This study illustrates the policy work done by teacher educators, in a landscape where ill-defined professional groups such as teacher educators may hold multiple professional roles (i.e. teacher, researcher, subject expert, etc.). The policy work is not only influenced by the unique beliefs and values of the professional, but also by the distinct contextual factors at play. When these professionals hold multiple roles, a further layer of complexity in the emerges, necessitating deeper exploration of teacher educators’ policy work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Erik Straume Bussesund

Erik Struame Bussesund is a PhD candidate at the at OsloMet, Oslo Metropolitan University. His research interests include education technology, professional education and education governance.

Oliver McGarr

Oliver McGarr is a professor in the School of Education at the University of Limerick, Ireland. He works primarily in the area of teacher education. His research interests are in the areas of educational technology, teacher education and school education.

Bård Ketil Engen

Bård Ketil Engen is a full professor at the Faculty of Education, Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway. His research interests include several areas of technology enhanced learning, such as: Cyber ethics, digital citizenship, educational policy, curriculum, digital literacy, and technology adaptation.

References

- Amhag, L., L. Hellström, and M. Stigmar. 2019. “Teacher Educators’ Use of Digital Tools and Needs for Digital Competence in Higher Education.” Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 35 (4): 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2019.1646169.

- Aydarova, E., J. Rigney, and N. F. Dana. 2024. “Claiming and Reclaiming the Voice of the Profession: Teacher Educator Policy Advocacy Through the Lens of Bakhtin’s Theory of Dialogism.” Teaching & Teacher Education 140:104479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104479.

- Bacchi, C. 2009. Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be? Australia: Pearson.

- Ball, S. J., and E. Grimaldi. 2021. “Neoliberal Education and the Neoliberal Digital Classroom.” Learning, Media and Technology 47 (2): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1963980.

- Ball, S. J., M. Maguire, A. Braun, and K. Hoskins. 2011. “Policy Actors: Doing Policy Work in Schools.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (4): 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2011.601565.

- Braun, A., S. J. Ball, M. Maguire, and K. Hoskins. 2011. “Taking Context Seriously: Towards Explaining Policy Enactments in the Secondary School.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (4): 585–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2011.601555.

- Bussesund, E. S., B. K. Engen, and O. McGarr. 2023. “Digital Compliance or Professional Competence? Representations of Teachers and Digital Futures in the Norwegian Qualification Framework.” https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2285831.

- Chiang, T. H., D. Trezise, Y. Z. Wang, and A. Thurston. 2023. “Policy Reconfiguration as Enactment in the Strategy of Recontextualized Neoliberalism: Paradigmatic Shift in Teacher Education Policy Reform.” International Journal of Educational Research 117:N.PAG–N.PAG. asn. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.102098.

- Cochran-Smith, M., L. Grudnoff, L. Orland-Barak, and K. Smith. 2020. “Educating Teacher Educators: International Perspectives.” The New Educator 16 (1): 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1547688X.2019.1670309.

- Ellis, V., M. Souto-Manning, and K. Turvey. 2019. “Innovation in Teacher Education: Towards a Critical Re-Examination.” Journal of Education for Teaching 45 (1): 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2019.1550602.

- Engen, B. K., T. H. Giæver, and L. Mifsud. 2015. “Guidelines and Regulations for Teaching Digital Competence in Schools and Teacher Education: A Weak Link?” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 10 (Jubileumsnummer): 172–186. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2015-Jubileumsnummer-12.

- Erstad, O., S. Kjällander, and S. Järvelä. 2021. “Facing the Challenges of ‘Digital competence’ a Nordic Agenda for Curriculum Development for the 21st Century.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 16 (2): 77–87. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-943x-2021-02-04.

- Facer, K., and N. Selwyn. 2021. “Digital Technology and the Futures of Education—Towards ‘Non-stupid’ Optimism.” UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377071.

- Fairclough, I., and N. Fairclough. 2012. Political Discourse Analysis: A Method for Advanced Students. London: Routledge.

- Fenwick, T. 2016. Professional Responsibility and Professionalism: A Sociomaterial Examination. London: Routledge.

- Griffiths, V., S. Thompson, and L. Hryniewicz. 2010. “Developing a Research Profile: Mentoring and Support for Teacher Educators.” Professional Development in Education 36 (1–2): 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415250903457166.

- Høydal, Ø. S., and M. Haldar. 2022. “A Tale of the Digital Future: Analyzing the Digitalization of the Norwegian Education System.” Critical Policy Studies 16 (4): 460–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2021.1982397.

- Ilomäki, L., S. Paavola, M. Lakkala, and A. Kantosalo. 2016. “Digital Competence – an Emergent Boundary Concept for Policy and Educational Research.” Education and Information Technologies 21 (3): 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-014-9346-4.

- Instefjord, E., and E. Munthe. 2016. “Preparing Pre-Service Teachers to Integrate Technology: An Analysis of the Emphasis on Digital Competence in Teacher Education Curricula.” European Journal of Teacher Education 39 (1): 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2015.1100602.

- Johannesen, M., and L. Øgrim. 2020. “The Role of Multidisciplinarity in Developing teachers’ Professional Digital Competence.” Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) 4 (3–4): 72–89. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3735.

- Kelentrić, M., K. Helland, and A.-T. Arstorp. 2017. Professional Digital Competence Framework for Teachers. The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/in-english/pfdk_framework_en_low2.pdf.

- Lambert, K., L. Alfrey, J. O’Connor, and D. Penney. 2021. “Artefacts and Influence in Curriculum Policy Enactment: Processes, Products and Policy Work in Curriculum Reform.” European Physical Education Review 27 (2): 258–277. asn.https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X20941224.

- Lambert, K., and D. Penney. 2020. “Curriculum Interpretation and Policy Enactment in Health and Physical Education: Researching Teacher Educators as Policy Actors.” Sport, Education & Society 25 (4): 378–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1613636.

- Lisborg, S., V. Daphne Händel, V. Schrøder, and M. Middelboe Rehder. 2021. “Digital Competences in Nordic Teacher Education: An Expanding Agenda.” Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) 5 (4): 53–69. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.4295.

- Ljungqvist, M., and A. Sonesson. 2022. “Selling Out Education in the Name of Digitalization: A Critical Analysis of Swedish Policy.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 8 (2): 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2021.2004665.

- Lund, A., and T. Aagaard. 2020. “Digitalization of Teacher Education: Are We Prepared for Epistemic Change?” openarchive.usn.no. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) 4 (3–4): 56–71. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3751.

- MacPhail, A., and M. O’Sullivan. 2020. “Challenges for Irish Teacher Educators in Being Active Users and Producers of Research.” In Teacher Educators as Teachers and as Researchers, edited by K. Smith and M. Assunção Flores, 64–78. Routledge.

- McGarr, O. 2024. “Exploring and Reflecting on the Influences That Shape Teacher Professional Digital Competence Frameworks.” Teachers & Teaching: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2024.2313641.

- Munthe, E., O. Erstad, M. B. Njå, S. Forsström, Ø. Gilje, S. Amdam, S. Moltudal, and S. B. Hagen. 2022. Digitalisering i grunnopplæring; kunnskap, trender og framtidig kunnskapsbehov, 1–136. https://www.uis.no/sites/default/files/2022-12/13767200%20Rapport%20GrunDig_0.pdf.

- Nagel, I. 2021. “Digital Competence in Teacher Education Curricula: What Should Teacher Educators Know, Be Aware of and Prepare Students For?.” Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) 5 (4): 104–122. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.4228.

- Nagel, I., G. B. Guðmundsdóttir, and H. W. Afdal. 2023. “Teacher educators’ Professional Agency in Facilitating Professional Digital Competence.” Teaching & Teacher Education 132:104238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104238.

- Nelson, M. J., R. Voithofer, and S.-L. Cheng. 2019. “Mediating Factors That Influence the Technology Integration Practices of Teacher Educators.” Computers & Education 128:330–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.023.

- Novella-García, C., and A. Cloquell-Lozano. 2021. “The Ethical Dimension of Digital Competence in Teacher Training.” Education and Information Technologies 26 (3): 3529–3541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10436-z.

- Orland-Barak, L., and J. Wang. 2021. “Teacher Mentoring in Service of Preservice teachers’ Learning to Teach: Conceptual Bases, Characteristics, and Challenges for Teacher Education Reform.” Journal of Teacher Education 72 (1): 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119894230.

- Örtegren, A. 2022. “Digital Citizenship and Professional Digital Competence—Swedish Subject Teacher Education in a Postdigital Era.” Postdigital Science & Education 4 (2): 467–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00291-7.

- Pangrazio, L., and J. Sefton-Green. 2023. “Digital literacies as a ‘soft power’of educational governance.” In World Yearbook of Education 2024, 196–211. Routledge.

- Reeves, J., and V. Drew. 2012. “Relays and Relations: Tracking a Policy Initiative for Improving Teacher Professionalism.” Journal of Education Policy 27 (6): 711–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2011.652194.

- Røkenes, F. M., R. Grüters, C. Skaalvik, T. G. Lie, O. Østerlie, A. Järnerot, K. Humphrey, Ø. Gjøvik, and M.-A. Letnes. 2022. “Teacher Educators’ Professional Digital Competence in Primary and Lower Secondary School Teacher Education.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 17 (1): 46–60. https://doi.org/10.18261/njdl.17.1.4.

- Sin, C. 2014. “The Policy Object: A Different Perspective on Policy Enactment in Higher Education.” Higher Education 68 (3): 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9721-5.

- Singh, P., S. Thomas, and J. Harris. 2013. “Recontextualising Policy Discourses: A Bernsteinian Perspective on Policy Interpretation, Translation, Enactment.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (4): 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.770554.

- Starkey, L. 2020. “A Review of Research Exploring Teacher Preparation for the Digital Age.” Cambridge Journal of Education 50 (1): 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1625867.

- Watson, C., and M. K. Michael. 2016. “Translations of Policy and Shifting Demands of Teacher Professionalism: From CPD to Professional Learning.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (3): 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2015.1092053.

- Webb, P. T., and K. N. Gulson. 2012. “Policy Prolepsis in Education: Encounters, Becomings, and Phantasms.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 33 (1): 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2012.632169.

- White, S. 2019. “Teacher Educators for New Times? Redefining an Important Occupational Group.” Journal of Education for Teaching 45 (2): 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1548174.