Abstract

This research joins the growing body of literature that advocates for the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in local governance more particularly in public financial management. Using a case study in Bohol, a province in the Philippines, this paper discusses the impact of ICT on local revenue generation by analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data from 15 municipalities which used e-taxation. This paper argues that the use of ICT can make possible more transparent and accountable revenue generation systems to benefit both government and taxpayers. However, these results are differentiated depending on the level of political leadership, the nature of articulation of the demand for ICT use, the ratio of benefit against cost, and the availability of technical skills and resources at the sub-national level. It is within this context that an eco-system analysis is argued to be useful in analyzing how ICT can be adopted, scaled, and used by sub-national governments to achieve better governance.

1. Introduction

Decentralized governance has contributed significantly to democratization processes in the Philippines since the passage of the Local Government Code of 1991 (Fabros, Citation2002; Nierras, Citation2005). While it allowed better and more efficient resource allocation, more responsive programs and projects to address local concerns, and greater citizen participation in government processes, it also challenged local government units (LGUs) to raise more revenues to ensure that it is able to fund basic services (Manasan & Villanueva, Citation2006).

Traditionally, local resource generation through taxation systems consisted of manual assessment, processing, collection, and reporting that made it susceptible to subjectivity, arbitrariness, and corruption, adversely affecting the capacity of local governments to raise funds as well as discouraging local investments. In recent years, however, reforms were instituted by the national government in ensuring better governmental processes of municipalities, especially in the context of business permits processing. Use of technology was also introduced in the last decade. The National Computer Center, tasked mainly to lead the computerization processes in the Philippine government, promoted the use of Real Property Tax Systems, Business Permit and Licensing System, and Treasury Management Operation Systems (Alampay & Tiglao, Citation2008).

More recently, international organizations invested support on local revenue generation. The German Technical Cooperation (GTZ), for example, promoted the use of Integrated Tax Administration System (ITAX) in several provinces and municipalities (Seelman, Lerche, Kiefer, & Lucante, Citation2010). On the other hand, the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) through the Provincial Road Management Facility (PRMF) promoted the use of the Enhanced Tax Revenue Assessment and Collection System (ETRACS) to seven participating LGUs (PRMF, Citation2013).

The impact of these systems in local revenue generation has been assessed in part by the funding agencies themselves. The ITAX assessment report of GTZ, for example, mentioned ten benefits in the use of ITAX not only in the Philippines but also in Tanzania. Among these are simplification of tax management, cost effectiveness of the system itself, efficiency in tax assessment and service delivery, and, finally, increase in local income. PRMF project reports, on the other hand, reported increase in local revenue generation and faster processing of local taxation records and documentation (PRMF, Citation2013).

The missing dimension, however, is how the computerization impacted on civil servants and on business registrants, the ultimate beneficiaries of the system. While the assessments made mention of how it made efficient the processes and improved revenue figures, it failed to take into account how civil servants view the improvement and how tax payers reacted to the process; this, besides the fact that there are only very few studies that focus on the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in local revenue generation processes.

This paper bridges these gaps. By using a case study approach in Bohol, Philippines, it seeks not only to look at how the system has contributed to improvements in revenue generation, but also how it impacted on civil servants engaged in revenue collection and on taxpayers transacting with local governments. Three processes were undertaken – revenue of secondary documents, key informant interviews with local government officers engaged in local revenue generation, and key informant interviews with taxpayers in participating LGUs. In this case, the focus is on the use of ETRACS, another ICT-enabled local tax collection system, than ITAX.

ETRACS was implemented in seven provinces in southern Philippines. With funding from the AusAID, these provinces set up ETRACS within pilot municipalities, trained personnel in the use of the system, and started collection, assessment, and reporting. The paper is based on a case study in the island Province of Bohol, in southern Philippines which is among those that registered the highest increase in local revenue generated from local taxation (i.e. business and property taxes) among the seven provinces. The particular interest in Bohol comes from the fact that the province was the only one among the seven which decided that it shall implement ETRACS in all 47 municipalities, having been convinced of its power to raise revenues as well as make assessment effective, efficient, and transparent.

The paper is structured in five parts. The first part reviews the literature on how ICT use in governance systems are viewed in e-governance studies and presents an alternative framework of assessment – an ecosystems assessment approach and how it can yield valuable insights. This part also presents the methodology used in the paper. The second part provides background to the case of Bohol, with particular emphasis on its practices in public financial management. This part also briefly describes ETRACS used by Bohol. The third part looks into the impact of ETRACS on local revenue generation by answering the research questions. It also presents the factors affecting successful ICT implementation. The fourth part looks into how an eco-system approach can inform the analysis of ICT initiatives in sub-national governance. The fifth and concluding chapter presents recommendations in using the eco-systems approach to assess ICT projects in sub-national contexts.

2. E-Government and eco-systems approach

2.1. E-Government and frameworks of assessment

E-government is widely referred to as “the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in public administration to change structures and processes of government organizations” (Loftsted, Citation2005, p. 40). It has been argued that ICT provides two opportunities for government – (1) increased efficiency by decreasing costs and increasing productivity; and (2) provision of better quality services to citizens (Gil-Garcia & Pardo, Citation2005). In later years, especially within the context of open governance data and in the implementation of smart city initiatives, the purposes of e-government extends to transparency and accountability, promoting economic development, and facilitating an e-society (WB, undated document).

In the past several years, there were different applications that were developed to serve both efficiency and service imperatives as well as web-based portals that are intended to enhance government transparency. Applications include online citizen service, integrated tax systems, social insurance online systems, resident registration and passport applications, real estate information management, vehicle administration, e-procurement, integrated accounting, and education management, among others (Lee & Oh, Citation2011). These applications are establishing new sets of relationships between government and citizens (G2C), government and business (G2B), agencies within the same government (G2G) and to address different governance (Jain Palvia & Sharma, Citation2007), and are viewed using an efficiency evaluative lens.

In a review of assessment frameworks for e-governance and e-government initiatives, Fitsilis, Anthopolous, and Gerogiannis (Citation2010) argue that most of the assessment frameworks focus on three dimensions, namely, project results, project processes, and customer satisfaction. These findings echo Muthama's (Citation2012) views that most of the assessments are focused toward individual customer experience and with less regard of changes occurring within government. However, when Fitsilis et al. (Citation2010) propose an alternative framework, it focuses on software projects, because they argued that such are the final products of e-government. In their model, they emphasized that there are two metrics that are needed to be looked into – (1) internal metrics, comprising organizations, processes, and results, and (2) external metrics consisting of social and economic perspectives and citizen satisfaction. These assessments, however, miss the wider context where e-government initiatives operate, that amalgamation of factors that not only relate to internal processes within government or its impact on citizens, but the wider environment involving policies at both national and sub-national contexts, actors within and outside government, the underlying elements that the ICT-enabled governance system would like to touch on.

2.2. Ecosystems approach as an alternative

This paper argues that assessing e-governance initiatives using an eco-systems approach will yield meaningful results. The Berkman Center defines an ICT ecosystem as comprising “the policies, strategies, processes, information, technologies, applications and stakeholders that together make up a technology environment for a country, government or an enterprise” (Berkman, Citation2005, p. 3). It asserts, however, that people are the most important factors in this ecosystem.

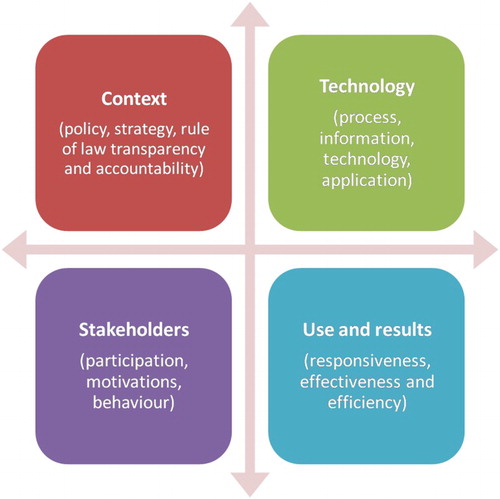

Literature regarding the use of eco-system analysis in ICT focuses on actors and their interactions (see Fransman, Citation2010), or actors and their interaction with a common environment (Arlandis & Ciriani, Citation2010). More recently, an articulation that expands this initial conceptualization was provided by the Open ePolicy Group (Citation2005, p. 3) where they define an ecosystem as that which “encompasses the policies, strategies, processes, information, technologies, applications and stakeholders that together make up a technology environment for a country, government or an enterprise” while at the same time underscoring that stakeholders or people are at the core of this ecosystem. This paper makes use of this definition in defining an alternative approach to assessing ICT initiatives shown in .

This paper takes the view that using an ecosystem as an analytical frame in looking at ICT and its role in local governance is possible by expanding this initial conceptualization to look at context, stakeholders’ motivation and behaviors, technology and its availability and affordability, use and demonstrated results, and how these different interactions feed further into the ecosystem's growth or decline. This needs to be interspersed with looking at governance systems, more particularly the normative principles of governance (Jokinen-Gavidia, Citation2012), in particular, participation, rule of law, transparency and accountability, responsiveness, and effectiveness and efficiency.

Understanding context would mean looking into the domains of governance that the ICT initiative, in this case, e-taxation, operates (Davies, Perini, & Alonso, Citation2013). This may take to mean looking into policies and strategies at the political governance realm (Gil-Garcia & Pardo, Citation2005), or extending to economic and social background that influences policies and strategies (Davies et al., Citation2013). Analyzing a stakeholder requires studying motivations and behaviors of actors within an ICT environment to understand better how ICT innovation affects them and how they affect the innovation in return (Walton, Citation2013). Technology needs to be assessed in order to know processes, applications, and its usability to intended users and compatibility with current context (Carter & Weerakkody, Citation2008) while use and demonstrated results are important to evaluate in order to see whether intended results out of an ICT innovation have yielded its committed or aspired changes (Fitsilis et al., Citation2010). What is important, however, in this case, is to look at how these factors interact with each other in creating an enabling environment for ICT innovation to work.

2.3 Methodology

This paper uses a case study approach by focusing on the Bohol province in the Philippines, using both quantitative and qualitative methods to arrive at answers to the following research questions:

What is the role of taxpayers and civil servants in improving local revenue generation through ETRACS?

How has ETRACS changed the way of enforcement of revenue collection laws in the municipality in terms of impartiality?

How does ETRACS make local revenue generation transparent and accountable?

How does ETRACS improve service delivery in terms of responsiveness?

How does ETRACS improve revenue generation at lesser costs?

The questions are largely patterned from Jokinen-Gavidia's (Citation2012) normative principles of governance, though each of these also corresponds to a set of analyses of the elements of an ICT ecosystem. Question 1, for example, looks into stakeholders while Questions 3 and 4 looks into strategy, processes, information, and technology. The interrelationships of these variables are further elaborated in .

Research Questions 1–4 are explored using Focus Group Discussions and Key Informant Interviews. A total of 28 civil servants involved in local revenue generation processes were interviewed while 7 focus groups were conducted involving 35 key taxpayers in the construction, hotel and restaurant, trading, agriculture, real estate, finance, and professional service sectors. An analysis of the themes arising from interview and focus group transcripts was done to arrive at a collective answer to these questions. Research Question 5 was explored using quantitative analysis of taxation records to determine changes of tax collection performance over time.

3. Use of ICT in taxation in Bohol, Philippines

Bohol, in the heart of Central Visayas, is the 10th largest island in the Philippines. It comprises 48 municipalities with 15, 14, and 19 municipalities composing the first, second, and third congressional districts, respectively. The productive force of Bohol is almost 58% of the total population, of which around 89% are engaged in farming and fishing. Agriculture remains the biggest sector in the province in terms of working population and land use (PPDO, Citation2010).

Tourism, however, is a primary driver of business and the economy. Its competitive advantage is the presence of the famous Chocolate Hills, white pristine beaches in its islands, diving sites, and world-class cultural attractions (Relampagos, Citation2002). Increased investments and promotional activities in the tourism sector have caused a dramatic rise in tourist arrival in the province since 2001. The increase in arrival has fueled increased economic activity in the capital city of Tagbilaran primarily because of the increased demand for services to cater to the rise in tourist inflow (Acejo, Del Prado, & Remolino, Citation2004). Correspondingly, the increased tourist arrival was positively correlated with increases in the number of manufacturing, service, trading, and agricultural establishments as well as employment (Acejo, Del Prado, & Remolino, Citation2004).

Despite these developments, the province and its municipalities are still dependent on the Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) to fund its public expenses. This is a condition reflective of the situation of other LGUs in the country (Del Castillo & Gayao, Citation2010). The IRA represents a local government's share of the revenues of the Philippine national government which controls the bulk of the Philippine bureaucracy's taxing powers. The province as well as its municipalities fund 80–95% of basic public expenditures from the IRA because of low-level, locally generated taxes and revenues and unrealized income estimates for collections (PPDO, Citation2010).

In 2010, the province of Bohol became a participating province of the PRMF, a local governance program funded by AusAID with roads as an entry point. One of the reform areas introduced and intervened on by the project was public financial management, more particularly on the aspects of planning and budgeting, procurement, and revenue generation. As part of the process, the province was assisted in formulating its Strategic Financial Management Plan, one of the objectives of which is to ensure sustained increase in local revenue generation.

Business income and tax revenues are the main revenue drivers in the PGBh (). Business income constitutes 32–39% of the total local revenues of the province, with hospital fees (treated at gross) contributing more than 70% of the total amount. Tax revenues, on the other hand, contribute between 48% and 49% to total local revenues, with real property taxes cornering more than 75% of the total tax revenues.

Table 1. Revenue profile of Bohol (author's calculations).

Of all provincial revenues mentioned above, RPT is only collected by the municipalities. The municipalities remit to the provincial coffers 35% as its share while it retains 40–65% for its own and 25% for the village where the real property is located. Thus, low collection for RPT, the largest source of local tax revenues for the province, is largely dependent on the efforts of the municipalities in the collection process. It is also susceptible to theft and corruption as tax payments from collectors can be stolen, intentionally or unintentionally, while in transit. Thus, it is to be the best interest of the province to ensure an effective and efficient collection system, not only for its own sake, but also for the municipalities within its geographical coverage.

PRMF provided this opportunity in 2010. It introduced to the province the ETRACS and committed to fund the implementation of five pilot municipalities. In a matter of weeks in 2011, ETRACS was deployed in the pilot municipalities, with the required hardware, training, support, and internet connectivity. The software has three core modules – collection (treasury), business permit and licensing, and real property tax assessment. People were trained from the point of processing to report generation. By and in itself, ETRACS covers the seven main components of tax administration (see Seelman et al., Citation2010), namely, registration, assessment, collection, payment, enforcement, auditing, and reporting. More importantly, in the case of the province, it makes municipal remittance of the provincial share of RPT transparent and demandable.

ETRACS is not free, because it requires certain investments, but is also not expensive. Developed by Rameses Systems Inc., a software company based in Cebu City, the software is freely available to LGUs to computerize tax and revenue assessment and collection. While installation is free, support and maintenance are not. To ensure that the software continues to be upgraded, maintenance is carried on by Rameses at a fixed fee of Php60,000 (app. 1360 USD) a year, regardless of LGU size and irrespective of amount of revenue collected. Payment of the fee entitles the LGU to free version updates, support and bug fixing, training, free hosting, and access to cloud-based services. Initial investment on ETRACS requires at least Php300,000 (app. 6820 USD), to cover the costs of two server-grade computers, a minimum of six computers for the different offices, a local area network connecting computers, two dot matrix printers, and two laser printers to print reports and certificates.

The intention of PRMF in introducing the system to five pilot municipalities was to model how computerization can impact on local revenue generation processes. As a result of the modeling, it was expected that the provincial government will take the challenge of implementing ETRACS in its other remaining municipalities. Expectedly, however, this decision could be made once the province and the five participating municipalities have seen the initial results of the pilot run.

4. ETRACS and local revenue generation

4.1. On increase in revenue collection

The PRMF provincial implementation team tracked the results of ETRACS implementation by monitoring the effect of the program on revenue generation. Undoubtedly, the initial and most visible impact of ETRACS was on local revenue generation. The table below summarizes the impact of ETRACS comparing the year prior to implementation and the year after implementation, for all five pilot municipalities ().

Table 2. Revenue comparison. Pre- and post-ETRACS implementation, pilot municipalities (author's calculations).

As shown in the table, business taxes of all municipalities increased significantly after ETRACS implementation. The average percentage of increase was 71%. Stark increases were noted in municipalities where business activities, more particularly manufacturing, trading, and services, are high like in the case of the municipalities of Talibon and Loon. In the case of real property taxes, only the municipality of Balilihan posted a negative result as real property tax collection decreased by 19%. For those municipalities registering an increase, the average increase was still large at 60%. The nature of the economy has an effect on real property tax collection. For example, most of the real property units in Balillihan according to the offices of the Municipal Assessor and Municipal Treasurer are agricultural land, and are sensitive to the quality of harvest in a cropping cycle because it affects a farmer's capacity to pay real property taxes. Tax revenues are recognized using cash basis than accrual basis of accounting, meaning that regardless of whether the government already has the right to collect tax revenue, as long as this is not collected, this is not recorded as tax revenue in the books of accounts.

Another effect of ETRACS is on processing time, reducing to a maximum of one day the processing and issuance of business permits which used to last for five days to one week. This means that significant amount of staff time is saved by the process, making civil servants available for other tasks and better customer satisfaction on the part of taxpayers. The quantification on savings brought about by automation will still need to be computed.

Even comparing 2010 and 2011, the year that ETRACS was implemented, significant increases were also noted more particularly for business taxes. The table below shows the increase in business taxes comparing the year the ETRACS was implemented and the immediately preceding year ().

Table 3. Comparison of business tax collection – ETRACS year versus preceding year in pilot municipalities (author's calculations).

The Local Finance Committee of the Province of Bohol analyzed the records. In the case of Talibon, all its investments in ETRACS were already recovered at the first implementation. In the case of the other municipalities, ETRACS investment will be recovered in five years' time, assuming the first year increase remains constant throughout. This made the province decide to fully implement ETRACS in all municipalities of the province, completing all deployment at the end of 2013.

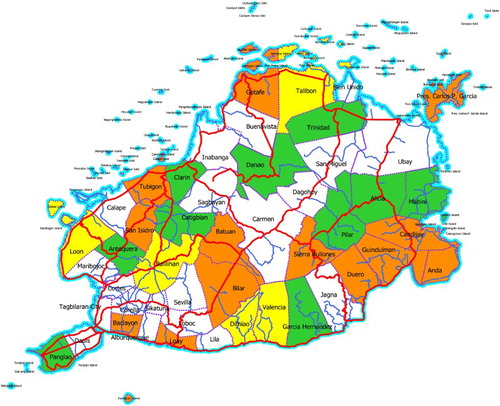

shows the five pilot municipalities (in yellow), the 10 municipalities (in green) belonging to the second batch of implementation in 2011, and the 10 additional municipalities (in orange) when ETRACS deployment was completed in 2012. The remaining municipalities (in white) are expected to be completed at the end of 2013. The second and third batches also experienced the same experience during ETRACS implementation.

The increase in revenues experienced by the pilot municipalities also occurred in the additional municipalities that implemented ETRACS after the pilot implementation (see ). The real property tax result was mixed. Though most municipalities’ tax revenues increased with an average of 94%, there were those whose revenues decreased between 1% and 8%. The stability of the revenue behavior will be tested further in succeeding years. For most of the batch 2 sites (only with the exception of two municipalities), however, the extent of increase in revenue is already sufficient to recover the ETRACS investment.

Table 4. Revenue comparison, before and after ETRACS year (author's calculations).

4.2. Revenue generation and governance dimensions

But revenue generation is a transaction and thus does not only bring about numerical results but also experiences on both the governing, or the duty bearers, and the governed, the claim holders. In this case, the automation process which is the subject of this paper does not only impact on the nature of the transactions (the tax collection process) but also on the collectors (civil servants) and the taxpayers (the citizens).

Secondly, this paper argues that the process of automating the revenue collection system is an improvement in governance infrastructure, and thus is intended not only for the sake of automation, but to achieve “good governance” in the context of public financial management. Thus, to view the results of automation only with respect to its immediate effect on revenue collection is insufficient. This is the reason why the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit assessment of ITAX was considered incomplete, because the reasons it identified for the use of the software was more about making transaction processing more effective and efficient. This paper argues that in order to assess the value of ETRACS in Bohol, it is important to view it with good governance lens. Using the normative principles of governance (Jokinen-Gavidia, Citation2012), this paper takes on five important questions as indicated in .

Two of the main questions in above are already answered in the previous section. These are the questions on effectiveness and efficiency (Question 5) and responsiveness (Question 4). However, the answers to these questions are explored only within the context of results in revenue collection and processing time. What this section would like to do is to answer these questions within the perspective of civil servants and citizens. The table below summarizes the thematic answers of respondents on each of the questions posed above ().

Table 5. Normative principles of governance and ETRACS.

As indicated above, the computerization of the local revenue generation process had positive effects on all dimensions except on participation. The results are explained in detail below:

On participation – ETRACS is a pre-developed software and thus comes as a package. ETRACS is not a law, but rather an enabling system to implement the law. Had ETRACS been a law (which is not at all necessary), it could have been subjected to consultations. However, because the application has been tested for several years since 2000 and is currently being implemented in 86 LGUs across the country, ETRACS seamlessly fits into governance processes as experienced by both civil servants and taxpayers without necessarily undertaking a survey of user needs or a consultation on what the taxpayer desires. In this case, participation of civil servants and taxpayers are at the lower level, what Arnstein (Citation1969) as the informing level.

On Rule of Law – The business community initially expressed objection to the system, because they no longer have the leeway to negotiate taxes, but later on appreciated how governments no longer treat taxpayers arbitrarily and minimized rent-seeking. In the case of Panglao, for example, there was a significant media war that involved the threatened filing of lawsuits between taxpayers and governments because of the presumptive income computation that ETRACS introduced. Panglao is a municipality where major hotels and tourist-related services are located. As business permits are dependent on self-reporting by taxpayers, business owners declare the amount of sales that they wished. However, when ETRACS was implemented, it made use of presumptive income computations, where, for example, the sales figure is correlated with number of rooms and average season occupancy rate for hotels, and number of tables and average season service-takers for restaurants. It was found out that the businesses were grossly under-declaring sales and much of the process involved negotiation with the chief executive. Thus, civil servants appreciated how the system removed the influence of local politicians to favor particular businesses and have made local collection reflective of local economic activity. If the system has already computed the rates, it is the amount that taxpayers should pay. What political leaders have to say no longer matters, unless there is a legal basis to support it (like in the case of national or local laws granting tax amnesty to certain types of investments). This is the reason why, in the case of Panglao, business tax collection increased by almost 100% on the year that ETRACS was implemented.

On Transparency and Accountability – Both civil servants and taxpayers appreciated the fact that tax assessment and collection has become transparent and predictable. The tax rates are supported by an ordinance and these are published in conspicuous places. The taxation forms are computer-generated and show how taxes are computed. The process determines at which stage the tax processing got stalled and can predict when a tax clearance or a business permit can be issued. As the only bottleneck would be the absence of signatories, it will become apparent who or what office is responsible for delaying the process.

On Responsiveness – Shorter processing time gave civil servants the feeling of efficiency and they become satisfied with their work. The very great improvement in terms of processing time makes taxpayers appreciate the service. For example, for taxpayers located kilometers away from the town center, being able to transact tax payments in one day, without having to go back for follow-up visits, is something that they had not experienced in many years. They were so accustomed to slow, delayed, and unpredictable processing times that ETRACS became a huge improvement in their experience with government transactions.

Tax Payers have long been clamoring for more predictable taxation systems as this would assist them in their budgeting processes. ETRACS became an answer to this need.

On Effectiveness and Efficiency – The views of civil servants and taxpayers differed significantly as they belong to different camps in the taxation process. Civil servants are concerned with revenue targets at lesser costs while taxpayers are concerned with getting their receipts and permits in lesser time. Civil servants are satisfied because ETRACS made possible the achievement of their revenue targets and even more. Taxpayers on the other hand are satisfied because they saved time, and presumably costs, because of the efficient process in handling tax assessments and collection.

The above elaboration suggests that computerization does not only increase revenue collection as other studies have highlighted (Chatama, Citation2013; Seelman et al., Citation2010) but also has a corresponding effect, as perceived by stakeholders, in strengthening the rule of law, enhancing transparency and accountability, improving government responsiveness, and making the impression that government is more effective and efficient in its services.

However, because computerization, by the nature of its intervention, oftentimes comes as a top-down approach, it inhibits participation of people in its conceptualization and may diminish a sense of ownership of stakeholders. This is particularly true for computerized systems that are off-the-shelf and pre-developed, where stakeholders’ role are limited to being trainees, users, and beneficiaries. As opposed to newly developed systems where users are part of the systems design process, ETRACS delimited the use of stakeholders to merely users.

What is lacking, in this case, is an effective and engaging communication process during deployment. Taxpayers and civil servants, for example, could have been involved in communication dissemination processes where they are asked about what are their common concerns during tax assessment and payment and how ETRACS will be able to address this. In this case, use of ICT in local governance, despite the fact that a system introduced is pre-developed, can still be within what Fabros (Citation2002), in her typology, and would describe as consultative.

5. Why an eco-system approach is useful

5.1. Looking at the enabling environment

The case in Bohol suggests that improvements in local revenue generation are dependent on several sets of factors that would create an enabling environment for more transparent and better-resourced local governments.

Firstly, it is important that there is political will on the part of local leadership to initiate reforms. This confirms what Sagun (Citation2009) has highlighted – that political will and institutional maturity are necessary in ensuring successful computerization reforms in revenue generation – in deciding to implement the system; in committing resources for equipment, training, and software; in ensuring that initial reforms are sustained. In contexts where local political leaders derive their power through tax negotiation with the business sector who also support them during elections, it is necessary that political will is exercised outside the LGU. In Bohol, the municipalities reacted on an external invitation at the pilot stage and a provincial campaign at the expansion stage. These external factors significantly influenced adoption and employment at the local level.

Secondly, demand for computerization, or for more efficient systems, needs to be articulated by stakeholders. In the case of Bohol, business establishments, landowners, and ordinary citizens have been clamoring for more transparent systems in how taxes are assessed, collected, and reported; thus, their strong appreciation when ETRACS was implemented, though initially they reacted negatively to the system. At the same time, career civil servants engaged in public financial management desired streamlined processes and more straightforward assessments that will make revenue budget projections more realistic. They also got tired of how political leaders intervene in tax collection processes, depriving revenues of more revenues, and destroying the rule of law. Thus, when they realized the potential of computerization to reduce discretion, they wholeheartedly supported the program. This confirms earlier research results that argue that for computerization processes to be successfully implemented, there should be strong public sector demand (Iglesias, Citation2010). This paper argues that while top-down approaches can possibly hasten the use of e-taxation systems, it is the demand for better services and better governance from both duty bearers and claimholders that will make the process more sustainable and foster stronger ownership among local actors.

Thirdly, for the system to be successful, and for political leaders to have increased support, the system should present itself as a revenue than as a cost measure. For example, if the experience of pilot municipalities in the initial year of implementation showed a depressing result – where the revenue decreased or the increase in revenue was not able to recover costs of investments – political buy-in at the provincial level and even at the municipal level would be drastically low. It must be noted that the provincial government spent for expenditures in deployment while municipalities invested on hardware and training costs. System sustainability relies in part on financial sustainability, especially when donor support weans (ADB, Citation2010; Bachelor et al., Citation2003). There is strong interest in the use of ETRACS in Bohol because the increase in revenue generated as a consequence of the implementation of the system, in some cases, is 10 times more than their initial investment. This is in contrast to the use of the Poverty Database Monitoring System, which was piloted in Bohol in the early 2000s to capture the state of local economic development. The cost of running the system was around Php200,000 (app. 4550 USD), lower than ETRACS, but after its initial run, only very few of the municipalities updated their databases. This was because they viewed the system as very costly without any tangible or financial effect, though it could have provided them a better basis for planning and a good starting point for developing projects for donor or national government assistance.

Fourthly, the technology platform should be available for the system to effectively operate. It includes not only the hardware, software, but also peopleware. The degree of adoption is largely dependent on the readiness of municipalities to provide these essential preconditions. For example, selection of the pilot municipalities in Bohol is dependent on the technological readiness of the municipalities. In some provinces where PRMF also presented the opportunity to use ETRACS, the take-up was minimal and the cascading from the initial pilot sites was very slow because internet connectivity which is necessary to connect municipal and provincial databases was unreliable, if not absent. Within Bohol, the enthusiasm of municipal treasury offices was lukewarm in municipalities where officials are technologically challenged.

However, the dimension that is critical but is yet too early to be tested in this paper is whether the increase in local revenue generation resulted in better services to taxpayers – to businessmen and to property owners – the ones bearing the burden of taxation. An increase in revenue generation is not only important in itself; the end result is for LGUs to have more resources to finance basic services. It is critical then whether increase in revenue generation resulted in improvements to the socio-economic condition (Darison, Citation2011) and this involves better planning and budgeting, more transparent procurement, and greater transparency in government spending. Thus, the challenge remains in improving not only revenue generation but the whole gamut of public financial management. This will be a future agenda for research in the Bohol case.

5.2. An eco-system analysis of the e-taxation case

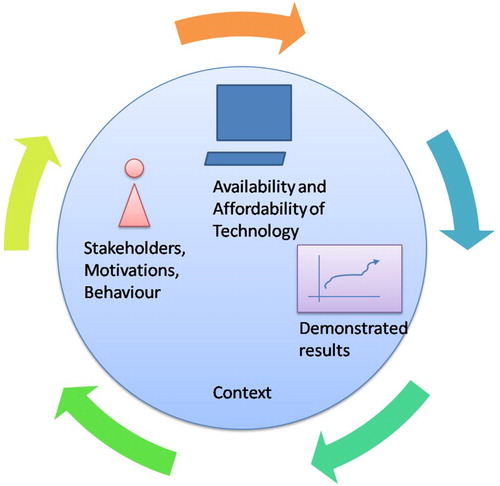

The case study in Bohol, Philippines, articulates how an ICT eco-system can be described within governance initiatives in sub-national contexts and how this ICT eco-system can be created and conditioned in such a way that it does not only ensure success but also sustainability of governance interventions. As indicated earlier, the success of the e-taxation initiative in Bohol, Philippines, depended on five general areas – political leadership, the articulated demand for better systems, demonstrated results, technology or infrastructure, and the long-term impact of such initiatives. However, this analysis can be extended further, to include other areas as policies, human resource capacity, innovation, among others ().

An analysis of context would include looking at two layers. The first layer is about the overall general context of country and its sub-national areas – including the political, economic, and social context and its interactions with legal, technical, and organizational requirement of ICT. For example, in the context of sub-national governance discussed in this paper, the global movement toward more transparency and accountability in governance coupled with the drive of the Philippine government toward “matuwid na daan” (Aquino government's slogan which means “straight path”) conditions the e-taxation initiative. It is also influenced by a growing economic base of the area where the increasing property prices and the sale between original owners and new investors, as well as the influx of investments in tourism activities, needed a better and efficient system of tax administration. It also helped that technology is already available that can be used to advance the initiative and that the legal environment allows the development of systems that can be used by LGUs in its drive for better governance. The second layer in this case is about the context specific to the issue itself – which in the context of the case is e-taxation. It includes looking at the availability of relevant laws, regulations, and systems governing the process; the availability of data and data flows; the stakeholders involved; the organizational capacity of the local government, and how these interact with technology platforms. The e-taxation initiative of this paper would not have been successful if taxation regulations were not in place, if data and data flows were not yet explicitly defined in the manual system, if stakeholder's responsibilities were not clear, and if local government does not have the capacity – human, financial, and institutional – to undertake the reform in taxation systems.

Beyond this, there is a need to look more explicitly at stakeholders and the analysis of their motivations and behaviors. In this case, eco-system analysis will benefit from stakeholder analysis, where each stakeholder within the ecosystem is identified, their motivations regarding the use of ICT as well as the issue on taxation are articulated, their behavior toward technology and the issue is analyzed, and their relationships with other stakeholders is mapped to look at how their interactions with each other and the environment they are in with reference to the specific issue of taxation influence the emergence and sustainability of technology use. In this case study, we observed that the political will of the local chief executive, the desire of middle managers to be more efficient, and the demand for taxpayers for more transparent and accountable was the impetus for technology use. However, its sustainability is conditioned also by other stakeholders, like civil society organizations who monitored the initiative, the local media who reported on it, and funding agencies keen on seeing results. Stakeholders behave distinctively from each other depending on their motivations and interests – some behave like champions (the forerunners), monitors (the checkers), claimants (rightholders), among others. This process of analysis is more than the layered model analysis used by Fransman (Citation2007) in looking at actors and their relationships.

The availability and affordability of technology is critical to ensure execution and operational feasibility. In the context of the case study, the local government need not devote time to the development of the software, or have to invest largely on hardware, systems, and processes. The phasing in of technology use was more efficient because technology is not only available, but also affordable. Had the process of e-taxation required larger investment or if it had been not accessible, then the wide use of it, from a pilot of 5 municipalities to a total coverage of 47 municipalities, would not have been possible. It also helps that internet connection is relatively strong because of the need for interconnectedness between the province and the municipal governments and that people are relatively skilled in the use of ICT systems. Without these facilitating factors, the use and scaling up of ETRACS would not have been possible within a short time frame.

The decision to scale up the ETRACS intervention would not have been possible if the pilot implementation in the five municipalities did not show that the use led to immediate demonstrated results. As noted, the pilot implementation drastically changed not only the process (e.g. faster processing times) but also the outcomes (e.g. increase in taxation). These benefitted not only governments (e.g. efficiency) but also taxpayers (e.g. cost-saving). The demonstrated results were immediate; they did not require a long gestation period. So continued adoption and use, as well as scaling up, was better facilitated. It did not require significant effort of convincing leaders and local government bureaucrats. It did not even require the development of communication materials or the conduct of information sessions to taxpayers so that they too would demand the use of the system.

Finally, the interactions of these four elements mentioned above are critical to sustained use and adoption of ICT in governance. For example, the changing economic context which makes possible increased investments in the local and thus more taxes available for collection influenced the stakeholders’ view of technology as well as their motivation to invest in more computers or more training for staff. Over the course of implementation, prices of hardware also decreased and broadband connection became more affordable, conditioning the decision to invest and apply technology. On a related note, the Philippine national government institutionalized an incentive mechanism where better-performing local governments in the area of public finance are awarded, thus encouraging elected leaders and technical bureaucrats to perform better and learn from others. In this case, for example, Bohol has become a learning site for LGUs wanting to improve local taxation mechanisms. Faster, efficient, and more transparent taxation systems encouraged government employees and make taxpayers satisfied. The interactions among these factors over time make adoption of e-taxation not only feasible, but also sustainable.

5. Conclusion

This paper has shown that a wider analysis of ICT initiatives in governance can be made possible through using an ecosystem approach by looking at context, stakeholders, use of technology, and intervention results, and how each of these factors affect each other in the process of bringing about the desired goals of the ICT intervention. It has also shown that delimiting assessments to looking only at project results, processes, and customer satisfaction would leave out in the analysis the many challenges and opportunities that affect ICT use, adoption, and impact in governance structures.

The case in Bohol suggests that elements in an ecosystem of e-taxation are not static but are evolving concepts and relationships constantly changing over time. In which case, the initial condition of these factors builds up as time evolves and the interactions among these factors influences continuance or discontinuance of ICT use. For example, had the impact on revenue been only immediate without any lasting or sustainable effects, or had revenue failed to increase over time after initial implementation, it would not have encouraged scaling up. Or hypothetically, had technology been more expensive, the decision to invest could have been severely affected. Likewise, if performance of governments was not rewarded or if both civil servants and taxpayers did not feel the benefit, then it could have prompted local governments to back track and go back to their old ways. Thus, the longer challenge of sustainability can only be addressed by ensuring that these factors move progressively toward a positive or better condition from the baseline. Doing so would need a clear understanding of the eco-system, and a recognition that each of the elements within it is evolving while this paper is written and read.

Acknowledgments

This research was conceptualized by the author while working for the AusAID funded Provincial Road Management Facility. Methodologically, the sessions with experts and peers in the IDRC that supported Emerging Impacts of Open Data in Developing Countries were also very helpful. Special thanks to Vera Villocido-Gesite who provided research assistance. The paper was presented in a conference on ICT and Development in Cape Town, South Africa, in December 2013.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributors

Michael Canares is Strategy Advisor at Step Up Consulting, a social enterprise that offers services on three core areas – development research, capacity building, and financial management. He is also the Open Data Regional Research Manager for Asia of the World Wide Web Foundation.

ORCID

Michael P. Canares http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9768-2631

References

- Acejo, I., Del Prado, F., & Remolino, D. (2004). Tourism fuels an emerging city: The case of Tagbilaran City, Bohol. (Discussion Paper Series 2004–53). Manila: Philippine Institute of Development Studies.

- Alampay, E., & Tiglao, N. (2008). Mapping ICT4D projects in the Philippines. Philippine Journal of Public Administration, 52(1), 1–23.

- Arlandis, A., & Ciriani, S. (2010). How firms interact and perform in an ICT ecosystem. Communication and Strategies, 79, 121–141.

- Arnstein, S. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. AIP Journal, 35(4), 216–224.

- Asian Development Bank. (2010). Information and communication technology for development: ADB experiences. Manila: ADB.

- Bachelor, S., Evangelista, S., Hearn, S., Peirce, M., Sugden, S., & Webb, M. (2003). ICT for development; contributing to the millennium development goals. Washington: The World Bank.

- Berkman Center for Internet and Society. (2005). Roadmap for open ICT Ecosystems. Retrieved October 12, 2015 from, http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/epolicy/roadmap/pdf

- Carter, L., & Weerakkody, V. (2008). E-Government adoption: A cultural comparison. Information Systems Frontiers, 10(4), 473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10796-008-9103-6

- Chatama, Y. J. (2013). The impact of ICT on taxation: The case of large taxpayer department of Tanzania revenue authority. Developing Country Studies, 3(2), 91–100.

- Darison, A. (2011). Enhancing local government revenue mobilization through the use of information communication technology: A case study of Accra Metropolitan Assembly. Graduate thesis submitted to Kwameh Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

- Davies T, Perini F, & Alonso J. (2013). Researching the emerging impacts of open data: ODDC Conceptual Framework. Retrieved November 12, 2014 from, http://www.opendataresearch.org/sites/default/files/posts/Researching%20the%20emerging%20impacts%20of%20open%20data.pdf

- Del Castillo, M. C., & Gayao, R. D. (2010). A municipality's experience on revenue generation and public economic enterprise development. JPAIR Multidisciplinary Journal, 4(Jan 2010), 29–47.

- Fabros, A. (2002). Civil engagements in local governance: The case of the Philippines. In Joel Rocamora (Ed.), Citizen participation in local governance: Experiences from Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines (pp. 173–197). Brighton: Logolink.

- Fitsilis, P., Anthopolous, L., & Gerogiannis, V. (2010). An evaluation framework of e-government projects. In C. Reddick (Ed.), Citizens and e-government: Evaluating policy and management (pp. 60–90). New York: Information Science Reference.

- Fransman, M. (2007). Innovation in the New ICT Ecosystem. International Journal of Digital Economics, 68(4th Quarter), 89–110.

- Fransman, M. (2010). The new ICT ecosystem: Implications for policy and regulation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gil-Garcia, R., & Pardo, T. (2005). E-government success factors: Mapping practical tools to theoretical foundations. Government Information Quarterly, 22, 187–216. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2005.02.001

- Iglesias, G. (2010). E-Government initiatives of four Philippine cities. (Discussion Paper 2010–22). Manila: PIDS.

- Jain Palvia, S., & Sharma, S. (2007). E-government and e-governance: Definitions/domain framework and status around the world. In Proceeding of the 5th international conference on e-governance, Hyderabad, India, 28–30 December 2007.

- Jokinen-Gavidia, J. (2012). Anticorruption framework for development co-operation. In Anti-corruption handbook for development practitioners (pp. 10–57). Finland: Department for Development Policy.

- Lee, N., & Oh, K. (2011). E-government applications. Incheon, Korea: UNAPC-ICT.

- Loftsted, U. (2005). E-government: Assessment of current research and some proposals for future directions. International Journal of Public Information Systems, 1, 39–52.

- Manasan, R., & Villanueva, E. (2006). Gems in LGU fiscal management: A compilation of good practices. Manila: PIDS.

- Muthama, C. M. (2012). Framework for quality assessment of e-government services delivery in Kenya. (Masters Thesis). Kenya: Strathmore University.

- Nierras, R. (2005). Citizen participation in financing local development: The case of Bohol water utilities, Inc. Brighton: Logolink.

- Open e-Policy Group. (2005). Roadmap for open ICT ecosystems. Cambridge, MA: Berkman Center for Internet and Society. Retrieved from http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/publications/2005/The_Roadmap_for_Open_ICT_Ecosystems

- Provincial Planning and Development Office. (2010). Provincial development and physical framework plan. Bohol: PPDO.

- Provincial Road Management Facility. (2013). Six monthly report. Unpublished document.

- Relampagos, R. (2002). Eco-tourism in the Bohol province: The Philippines. In T. Hundloe (Ed.), Linking green productivity to eco-tourism: Experiences in the Asia Pacific region (pp. 191–198). Tokyo: Asian Productivity Organization.

- Sagun, R. (2009). eGovernance for municipal development in the Philippines. Case note. Unpublished document.

- Seelman, J., Lerche, D., Kiefer, A., & Lucante, P. (2010). Benefits of a computerized integrated system for taxation: iTAX Case Study. Eschborn: GTZ.

- Walton, R. (2013). Stakeholder flux: Participation in technology-based international development projects. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 27(4), 409–435.