1. Introduction

This special issue examines organizational issues with the design, implementation, and use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in relation to development. The concept of development entails progress or growth in parts of the world where people are faced with unique challenges of limited resources and capabilities (Kamal, Good, & Qureshi, Citation2009). The World Bank uses gross national income (GNI) per capita to classify nations as low income, lower middle income, upper middle income, and high income economies (World Bank, Citation2014). All nations except those in the high income bracket are generally referred to as developing nations. Using 2014 data places all nations with less than $44, 272 GNI per capita into the developing nations category (World Bank, Citation2014). Some scholars find this broad distinction between developed and developing nations misleading and propose the use of business environment criteria such as laws and regulations, governmental control, workforce characteristics, management style, customer characteristics, economic conditions to distinguish three different economies within the developing nation category prescribed by the World Bank. These are developing, transition, and emerging economies. A brief description of the three economies is discussed in a later section. (For more comprehensive discussions of these economies see Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2011, Citation2015.) The scholars refer to the three economies as less-developed nations. In this editorial, the term less-developed economies will be used in reference to the three economies.

The less-developed economies generally lack resources and capabilities (Kamal et al., Citation2009). Organizations in these economies can benefit from innovative use of ICT and diffusion of mobile technologies within their customer base. However, research focusing on ICT within an organizational context in these economies is still scarce and the few studies that have studied organizations have ignored microenterprises and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) or discount how they contribute to development (Heeks, Citation2008, Citation2009; Kamal & Qureshi, Citation2009; Qureshi, Citation2011). Moreover, most of the existing studies on microenterprise organizations are atheoretic (e.g., Heeks Citation2010).

Based on extant literature, this editorial presents a framework for researching on information and communications technologies for development (ICT4D) in organizations in less-developed economies marked by limited resources and capabilities toward development. The framework is used to highlight the specific contributions of the articles presented in this special issue toward ICT4D. The papers offer insightful contributions in the context of development by employing theories such as actor-network theory, affordance theory, resource-based view theory, and new institutional theory to study ICT implementation and use within organizations in developing, transition, and emerging economies. The papers present theoretical models on e-commerce, mobile commerce, enterprise systems, electronic government, and self-developed technologies in less-developed nations with particular focus on microenterprises and SMEs.

The framework presented here is useful for several reasons. First, the framework is used to highlight the theoretical contributions that the papers in the special issue made toward ICT4D in less-developed economies. Second, it provides a roadmap for researchers interested in contributing to theory development in ICT4D at the organizational level in less-developed nations in particular and regions of the world where people are characterized as having limited resources and capabilities (Kamal et al., Citation2009). Third, since the framework is more generic, it offers opportunities for extension in specific contexts toward expanding research on ICT4D. For instance there is a call to use existing theories to explain relationships and behaviors in transition economies (Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2015). Finally, the studies in the special issue advance our understanding on existing theoretical models by incorporating contextual variables.

2. ICT research in developing, transition, and emerging economies

Organizations represented in this special issue have some unique characteristics including limited resources and capabilities. These organizations are located in nations with long working hours and low innovation index. In addition, the people within these nations who serve as employees and consumers of the organizations have challenges with education and use of ICT. The nations have low proportion of households with computer and Internet access, high mean years of schooling, and low life expectancy (Kowal & Roztocki, Citation2013). Roztocki and Weistroffer (Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2011) argue that developing nations which cover low income, lower middle income, and upper middle income are too diverse to be grouped as one type because some nations are making progress toward high income whereas others are slow, keeping them at the developing level. Developing economies are characterized by “low gross national income per capita and are generally characterized by low standards of living, a weak industrial and commercial base, and a poor infrastructure” (Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2011). Countries in this class of economies include Ghana, Congo, Swaziland, Kenya, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Angola (Kowal & Roztocki, Citation2013). These economies are also marked by relatively slow and unpredictable changes in laws and regulations, and a management outlook that is adept at the reallocation of resources (Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2011). The unique business environment in these economies influences the nature of design, implementation, and use of ICT.

The characterization of developing countries by low GNI per capita also translates into general unemployment, poverty, low standards of living, modest personal savings, and little capital accumulation. These conditions, coupled with other socioeconomic weaknesses make conducting business in developing countries precarious relative to the developed countries (Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2008). It is also observed that most companies in developing nations are usually managed by their owners, who may not have the requisite expertise to drive operational excellence, while other social, cultural, behavioral, and attitudinal characteristics further debilitate smooth operation of businesses in these nations (Asamoah, Andoh-Baidoo, & Agyei-Owusu, Citation2015). The impact of the business environment as well as the organization’s work culture on ICT implementations have been well documented in the literature (e.g., Huang & Palvia, Citation2001). At the same time, organizations operating in such countries may face unique challenges and opportunities that lead to innovative uses of ICTs, such as mobile payment systems.

Transition economies are countries that “previously had communist style, centrally planned economies, and have recently moved or are in the process of moving to free market systems” (Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2008). According to Roztocki and Weistroffer (Citation2015), the transition process can occur in a broader transformational context in three different ways: territorial, political, and economic. Thus, a nation can be classified as single, double, or triple transition. Single transition is characterized by incremental abolishment of a centrally planned economic system to progressive increase in private sector business activity creating a new class of entrepreneurs. Examples of nations with single transition are China and Vietnam. Double transitional nations are marked by sudden replacement of centrally planned economic system and one-party political system with a new class of entrepreneurs and political elites. Examples of nations classified as double transition are Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and Mongolia. Finally, triple transition bears the characteristics of double transition. In addition, it is marked by surprising changes in political entities and redefinition of borders. Russia, Slovakia, Croatia, and Georgia are examples of such an economy. In general, new young class of entrepreneur-minded managers in transition economies have recognized the need for new ICT management to support new strategic business models (Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2015).

An emerging economy “consists of countries or regions with low absolute but fast growing per capita income, and with administrations that are sincerely dedicated to economic liberalization” (Arnold and Quelch Citation1998). In theory, open economies tend to foster organizational growth as opportunities such as access to new markets, skills, and expertise, as well as administrative efficiencies may potentially increase operational and employees’ productivity. Nations classified as emerging economies include United Arab Emirates, Cyprus, Malta, Qatar, Bahrain, Chile, and Argentina (Kowal & Roztocki, Citation2013).

Roztocki and Weistroffer (Citation2011) assert that majority of the limited work on information systems (IS) research in less-developed countries is conducted with the assumption that best practices emerging from developed countries exhibit universality and can, with some little modifications, be successfully adopted in the different business environments of the less-developed economies. Furthermore, IS researchers use theories and models that presume a predictable business environment, stressing on long-term strategic planning based on hard data. This notion is the direct opposite of the situation in less-developed economies, especially the developing economies (Roztocki & Weistroffer, Citation2011). These scholars believe that such broad presumptions are made only because of lack of theory to explain the research outcomes in less-developed countries, making most of these works unreliable. Generalizations of theoretical models for firms in less-developed economies based on the environmental conditions of developed countries can be inaccurate and can paint a wrong and misleading picture of ICT design, implementation, and use. This situation can be detrimental to the organizations in particular and to the economic development of the nations in these economies in general.

Muriithi and Crawford (Citation2003) argue that prescriptions are made without consideration of how cultural and economic factors may influence the validity of the orthodox approaches in developing economies. Further, organizational theorists contend that Western-oriented management techniques may not be valid in non-Western contexts due to socio-cultural factors. These factors have been shown to play a potent role in determining the shared norms, values, attitudes, and beliefs about work organizations, among both managers and employees. Thus, what works in one context may not necessarily work in another (Asamoah et al., Citation2015; Muriithi & Crawford, Citation2003).

3. Conceptualization of ICT4D

Prominent ICT4D scholars lament the challenge in demonstrating the contribution of ICT to development despite the enormous investments made in ICT especially in less-developed nations toward development (e.g., Brown & Grant, Citation2010; Heeks, Citation2010; Kleine, Citation2010). For instance, Heeks (Citation2010) recalls huge ICT investment in less-developed nations. First, developing and transitional economies spent over $800 billion on ICT investment with Africa’s contribution exceeding $60 billion and private sector portion on mobile telephony exceeding $10 billion per year (Heeks Citation2009). Second, the less affluent outside the top quartile spend between 11% and 27% of their monthly income on telephone usage (Gillwald & Stork, Citation2008). Third, about 50% of individuals in rural Tanzania spend over 20% of total income on mobile telephone usage such that some sacrifice basic necessities such as education, food, and cloth (Mpogole, Usanga, & Tedre, Citation2008).

Avgerou (Citation2010) reminiscences how “ICT and development studies are based on the premise that ICT can contribute to the improvement of socioeconomic conditions in developing countries” (p. 1). Offering an explanation for the failure of extant ICT4 research to build cumulative tradition toward development, Brown and Grant (Citation2010) echo (Walsham & Sahay, Citation2006) that there are two main research domains for ICT in less-developed nations: (1) technology for development and (2) understanding technology in developing economies. Brown and Grant (Citation2010) argue that majority of studies fall into the second category. They further suggest that researchers need to appreciate the differences between the two disparate research streams so that they can make contributions toward building cumulative tradition in ICT and development research agenda. According to Walsham and Sahay (Citation2006), ICT in developing countries type of studies emphasize cultural implications and local adaptation of ICT design, implementation, and use. ICT for development studies on the other hand focus on the link between ICTs and development as well as how ICT empowers marginalized populations. Using this framework, Brown and Grant (Citation2010) reviewed research on ICT in developing nations and found that about two-thirds of such studies focused on technology in developing nations with one-third on ICT and development.

While the classification of ICT into these streams can help build cumulative research for each stream, others believe that the “strict” definition of “development” may limit the number of studies that are geared toward development (Heeks Citation2010; Prakash and De Citation2007). Further, Heeks (Citation2010) believes that the value chain framework is useful in understanding how ICT research in general may represent different stages or levels of development. This perspective contends that ICT for development can be envisioned beyond infrastructure development through the ICT4D value chain. In particular, in an effort to understand ICT contribution, infrastructure and access should be considered as the starting point and the goal should be on the outputs from ICT investments (Heeks, Citation2010). Heeks and Molla (Citation2009) therefore offer the value chain device consisting of four domains: readiness, availability, uptake, and impact as a means to link infrastructure to ICT impact.

Others argue that ICT4D “has focused on studying the use of ICTs for various development objectives – income growth, health, education, government service delivery, micro-finance, etc. in many countries, primarily the low-income countries, in the world” (Prakash and De, Citation2007, p. 263). The authors see development as “fundamental or structure change … and also as an action/or intervention aimed at effecting such a change” (p. 263) citing economic growth and capacity building as two of the ways by which an economy can be measured with respect to growth. Raiti (Citation2006) claims that ICT research focused on investigation in areas such as “telecenters, technological infrastructure, telephone incumbents, VoIP, mobile telephony, digital education, and digital divide.” Such research fits the readiness and availability domains of Heeks’ (Citation2010) value chain framework.

Heeks (Citation2010) contends that the question whether the huge investments in ICT by individuals, organizations, and nations contribute to development can be answered in the affirmative if infrastructural development is seen as key component of the broader development, and ICT as a major part of infrastructure. The study points out that using a design and implementation model based on developed nations in less-developed nations may contribute to failure of ICT4D initiatives in these nations and that the challenges with the earlier stages of the ICT4D value chain, that is, readiness, availability, and uptake may have hindered the need for assessing the impact of ICT4D. However, donor organizations have called for more theory-driven impact assessment (DFID, Citation2009, cited in Heeks Citation2010).

Another stream of research on ICT4D argues that the impact of ICT on development should not be prescribed solely by the economic development aspect and rather this stream proposes the choice framework as a means to view ICT4D as a systematic process for development (Kleine, Citation2010). More specifically, this stream views failure of ICT4D scholars to demonstrate development in ICT usage as a paradox and offers two plausible reasons for the failure. First is the notion that ICT4D conceptualization is too focused on economic growth, arguing that such a view is too narrow for capturing the impact of ICT. Second is the restrictive nature by which ICT has been measured whereby intended development outcomes are prescribed a priori in a top-down manner. This is considered uncongenial because ICT presents a multi-purpose application in the contexts where it can allow individuals to select their own developmental outcomes. Using Sen’s capability theory, this stream of research advocates the freedom of choice approach of development, whereby an actor such as an individual, organization, or institution’s development is measured by a wellbeing facilitated by capabilities.

In a broader sense, the right combination of investments in ICT, healthcare, and education is critical for development (Ngwenyama, Andoh-Baidoo, Bollou, & Morawczynski, Citation2006), or ICT is only one part of a broader picture of development (Duncombe, Citation2006).

Obviously the discussions presented in this section while useful are more applicable to individuals and society at large but less focused on ICT4D in organizations. The next section presents a framework toward the ICT4D research agenda in organizations.

4. Contributing to research on ICT4D in organizations

While the International Federation for Information Processing’s Working Group 9.4 has been credited for pioneering the foundation for ICT4D studies, those studies “focused largely on understanding issues of technology innovation, transfer and implementation” (Heeks, Citation2010, p. 630). In addition, the majority of the studies employed frameworks that are outside the information systems discipline. Among these are theoretical models such as the actor-network theory, new institutionalism, and structuration with no concern for socioeconomic development. Concerning studies at organizational level, Heeks (Citation2010) claims that

If we turn to organizations/management studies, for example, we can find a set of work that has taken the enterprise as the unit of analysis, and sought to understand the contribution of ICT to development through its impact on micro-, small and medium-sized enterprises. (p. 631)

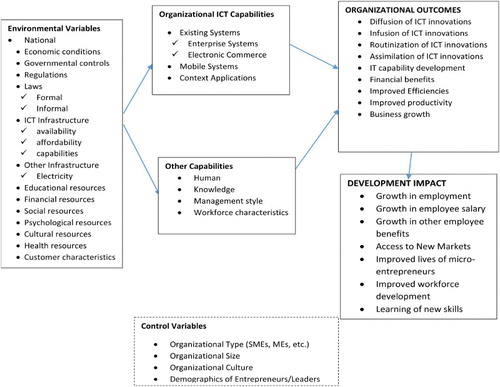

We employ the value chain framework and the choice framework as a new broader framework for examining ICT4D studies in less-developed nations especially among microenterprises and SMEs. presents the framework.

Figure 1. Framework for ICT4D studies for organizations faced with limited capabilities and resources.

From the value chain framework perspective, ICT4D could contribute to a specific stage of ICT4D. At the readiness stage, research could investigate background national variables that influence specific ICT innovations such as ERP and e-commerce. Such studies will focus on the left hand side or antecedents of organizational level capabilities or even look at the organizational level capabilities. Research focused on the availability stage may examine whether users or consumers have necessary ICT tools to interact with the organization’s infrastructure. For instance mobile technologies are most widely used in these less-developed nations; hence organizations need to develop mobile technology infrastructure to support these customers. Awareness of technologies for both organizations and consumers will precede or will be performed in combination with such studies. Demand, usage, and diverse groups in the user base will be core issues for the uptake stage studies. Finally, social development and economic development goals will be central to studies at the impact stage. Where organizational studies may not directly focus on such issues, the use of research methodologies such as action research and qualitative studies can help learn about these issues.

Kleine’s (Citation2010) choice framework proposes that ICT4D studies that seek understanding of the benefits or impact of ICTs on development have to consider issues related to how agency-based capabilities and structure-based capabilities influence degree of empowerment and subsequent developmental outcomes. These capabilities, resources, and outcomes are captured in the framework. Some of the important issues to consider from the choice framework perspective are how ICT is helping SMEs financially. Directly to this point, how is ICT creating livelihoods? (For instance one of the papers in the special issue demonstrates how ICT enabled people in the informal sector to earn higher income than their counterparts in formal sectors.) Providing evidence of this concept, Fichman (Citation2000) presents some specific organizational outcomes with respect to diffusion innovations that are relevant to ICT4D and are included in the framework.

In this special issue we echo those scholars who believe that ICT can help microenterprises and SMEs in both formal and informal sectors (e.g., Ducombe, Citation2006; Heeks, Citation2010; Kamal & Qureshi, Citation2009). These organizations provide livelihood to the poor through employment (e.g., Kamal et al., Citation2009). This is the focus of the special issue. In particular, this special issue is looking at ICT and development issues among microenterprises and SMEs in developing, transitional, and emerging economies. It also looks at ICT innovations in terms of both existing and new technologies, highlighting diverse issues including capabilities, outcome, impact, diffusion, adoption, adaptation, constraints, and enablers. For instance, Heeks (Citation2010) presents policy arena related to organizational level studies that focus on mobile technologies. Here, we expand the discussion to include different ICT implementations such as ERPs, e-commerce, mobile applications, and electronic kiosks.

Thus, ICT4D studies at the organizational level toward theory building will seek to explain how microenterprises and SMEs are employing existing technologies and novel innovation such as ICT kiosks and self-service technologies (SSTs) to improve productivity and expansion of business. These productivity improvement and expansion of businesses are linked to increase in income and hiring of employees, which are critical for development in less-developed economies (e.g., Kamal & Qureshi, Citation2009).

The microenterprises and SMEs are foundations to growth in the less-developed economies (Kamal & Qureshi, Citation2009). These organizations offer employment opportunities for citizens in these economies. Hence understanding how microenterprises and SMEs are implementing and using ICTs is crucial in ensuring SMEs contribute to development. However, only few studies in these economies, especially the least-developed nations, have studied ICT issues at the organizational level. The few that have studied these economies are atheoretical, hindering the relevance and impact at both the theoretical and practical levels (e.g., Heeks Citation2010). In addition, studies typically focus on medium to large organizations with microenterprises in particular left out (Kamal et al., Citation2009).

At the organizational level, understanding how entrepreneurs are building ICT capabilities to remain competitive and thereby grow their businesses will enhance the contributions to understanding the impact of ICT which fits the impact dimension on the ICT4D value chain. Additional development outcomes such as access to new outcomes, improvement in working conditions, increased productivity, and effect on learning and improvement in micro-entrepreneurs’ lives are relevant in this framework (Qureshi, Citation2015).

Some question whether the use of traditional social science research methods such as survey, ethnography, and face-to-face interviews methods are the best methods for research in developing nations. One argument supporting this view is that there are redundancies, monotony, and disinterest in reading articles that employ similar epistemological perspective on ICT4D research (Raiti, Citation2006). We contend that the benefits of using traditional research method is to enhance theoretical models through replication and extensions to build cumulative research in the ICT4D in both developed and less-developed nations while helping practitioners understand how contextual factors influence ICT4D in different regions. Replication and extension studies have been recognized as critical for growth of a discipline (Berthon, Pitt, Ewing, & Carr, Citation2002; Tsang & Kwan, Citation1999).

5. Articles in the special issue

Papers presented in this special issue address lack of research with respect to theoretical development in the ICT4D literature. These papers advance our understanding and extend existing theoretical models by including new contextual variables that help provide a more robust explanation on how some existing and novel ICTs are developed and used outside the developed nations’ context.

The papers in this special issue cover different ways organizations, especially microenterprises and SMEs, utilize ICT and the various forms of development that such ICT use in developing, transition, and emerging economies affords. Scholars have expressed concern that research in the less-developed economies are carried out by researchers living in the developed economies (e.g., Joia, Davison, Diaz Andrade, Urquhart, & Kah, Citation2011, cited by Qureshi Citation2015). In this special issue, six of the eight articles were authored solely by scholars in the studied region. Only one article had authors stationed in developed nations and another paper by authors from both developed and less-developed regions.

The papers presented in this issue explore issues related to the innovative design, implementation, and use of ICT in organizations in less-developed economies, focusing on how these may differ from experiences in developed economies. They describe the contextual variables that influence the design, implementation, and use of existing and novel technologies including enterprise systems, e-banking, e-government, e-commerce, and mobile commerce in less-developed economies.

User involvement is a key critical success factor (CSF) of ICT projects in both developed and less-developed nations. However, there is the tendency that ICT projects in less-developed nations may originate from donor organizations. Thus, it is not clear the extent to which users are involved in such projects and the results of user participation in the success or failure of organizations. More importantly, understanding the involvement of microenterprise owners in the development of ICT solutions is crucial (Qureshi Citation2015). One of the papers in the special issue addresses grassroots participation issues.

The first paper in this issue is authored by John Effah and is entitled “Institutional effects on e-payment entrepreneurship in a developing country: Enablers and constraints.” The author investigates how regulative, normative, and cognitive institutions affect e-payment entrepreneurship in developing countries. The author uses interpretive case study methodology and the new institutional theory to trace an e-payment entrepreneurship attempt in the developing-country context of Ghana. The study found that international and national institutions encouraged the e-payment entrepreneurship initiative. However, both governmental and entrepreneur challenges including unclear regulations and bureaucratic processes of the Central Bank as well as the entrepreneur’s own cognitive failure to consider contextual differences between the developed and the developing world constrained the initiative.

The second paper is co-authored by Gabriel Marcuzzo do Canto Cavalheiro and Luiz Antonio Joia and is entitled “Examining the implementation of a European patent management system in Brazil from an actor-network theory perspective.” The authors examine some of the key issues associated with e-government technical cooperation programs designed to enhance the service provision of Patent Offices in developing countries. They adopt the actor-network theory as a framework for understanding the processes of transferring e-government technologies from the European Patent Office (EPO) to the Brazilian Patent Office, which is locally called Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial (INPI). Through a longitudinal study the authors contribute to the limited empirical evidence surrounding technical cooperation involving Patent Office organizations. The findings suggest that gaps and conflicts among the existing national laws and policies, duration and type of historical interactions among EPO and INPI, as well as differences in the Information Technology infrastructure (ITI) and capabilities of the participating organizations are the key issues in e-government technology transfer between EPO and INPI.

The third paper is authored by Richard Boateng and is entitled “Resources, electronic-commerce capabilities and electronic-commerce benefits: Conceptualizing the links.” The author seeks to address the lack of theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence to understand how firms in developing economies orient resources to create e-commerce capabilities and achieve e-commerce benefits amidst their national constraints. The author employs the resource-based theory and the capability life cycle to investigate how a used-car retail firm in Ghana oriented resources to create e-commerce capabilities and achieve e-commerce benefits. The author presents two major findings. First, in developing economies, due to the weak institutional foundations and many obstacles, managerial capabilities and global information systems resources enable firms to withstand or circumvent the national constraints and create e-commerce capabilities and benefits. Second, the value of resources to a firm is relatively time and path dependent; changes in the environment can either initiate their renewal or decline in the firm. Having a focus on the strategic orientation of the firm is therefore of more value than focusing on information systems resources. The paper proposes a cyclic resource-based model of e-commerce capability evolution which offers new insights into the way in which e-commerce capabilities evolve to create e-commerce benefits.

The fourth paper is co-authored by Berhanu Borenaa and Solomon Negash and is entitled “IT infrastructure role in the success of a banking system: The case of limited broadband access.” The authors argue that while the IS success model has been validated in high-income countries, research in low-income countries is still lacking. The authors bridge this gap by identifying ITI as a contributing construct when evaluating the IS success model in the context of low-income countries. The authors investigate the research question: when considering low-income countries, what is the role of ITI in information systems success? The primary motivation for this research is the limited ITI and limited Internet access in low-income countries that hinder the success of information systems. Using a survey of 102 bank employees in a low-income country – Ethiopia and SEM-PLS analysis, the study showed strong impact of ITI on user, user satisfaction, and net benefit. The authors recommend inclusion of the ITI construct when evaluating the success of information systems and the policies that govern it.

The fifth paper is authored by Piotr Soja and is entitled “Reexamining critical success factors for enterprise system adoption in transition economies: Learning from Polish adopters.” The author seeks to investigate and better understand CSFs for enterprise system adoption in transition economies. The research was conducted using data from 144 enterprise systems adopters in Poland, a transition economy from Central and Eastern Europe. An analysis based on grounded theory revealed 20 CSFs grouped into four categories. Next, a stakeholder analysis of the discovered CSFs was performed. The achieved results were compared with the findings of prior research conducted in developed and developing economies. The main results imply that the most important CSFs for enterprise systems adoption in Poland are connected with people playing varied roles in the implementation project. The findings also suggest that people-related considerations will replace finance- and IT-related issues in the future. Other hypothesized trends include a growing importance of tangible benefits and organizational changes in transition economies.

The sixth paper is authored by Amit Prakash and is entitled “E-Governance and public service delivery at the grassroots: A study of ICT use in health and nutrition programs in India.” The author argues that although e-Governance projects continue to witness sustained policy focus in low- and lower middle income countries such as India, not many e-Governance projects are associated with improved performance, leading to an enhanced public value, especially in the grassroots delivery units of government organizations engaged in provision of development services to people. Using a case study of ICT use in public health and nutrition programs in the Indian province of Karnataka, the author argues for a need to shift the design focus of e-Governance projects due to the fact that while the grassroots functionaries in such organizations have a critical role in meeting performance goals, e-Governance designs have been largely oblivious to the need of improving their overall work content and environment. The findings suggest that it is time e-Governance projects in government organizations engaged in public service delivery acknowledge and rectify this contradiction to be more effective in achieving a broad set of governance outcomes and justify huge investments being made on them in relatively resource-constrained regions of the world.

The seventh paper is co-authored by Susan Wyche and Charles Steinfield and is entitled “Why don’t farmers use cell phones to access market prices? Technology affordances and barriers to market information services adoption in rural Kenya.” The authors contend that providing smallholder farmers with agricultural information could improve economic development, by helping them to grow more crops, which they could then sell for more money. They further state that widespread mobile phone ownership in Africa creates a realistic opportunity to deliver pertinent information to remote farmers throughout the continent. They note that efforts have been made to harness the potential of mobile phones including the development of agricultural market information services (MIS) – applications that send farmers crop pricing information via short message service (SMS). These services promote economic development among some farmers in the developing world, but not yet in rural Kenya. To understand what factors impede the adoption of these services, the authors use the qualitative research method to study Kenyan farmers’ mobile phone usage patterns and their interactions with MFarm, a commercially available MIS. Using affordance theory to guide their analysis, the authors discovered a mismatch between the design of MIS and smallholder farmers’ perceptions of their mobile phones’ communication capabilities. The authors use these findings to motivate a design agenda that encourages software developers and development practitioners to adopt an ecological perspective when creating mobile applications for sub-Saharan Africa’s rural farmers. Strategies for implementing this approach include reconsidering the design of mobile phones, and developing innovative educational interventions.

The eighth paper is co-authored by Arun Kumar Kaushik and Zillur Rahman and is entitled “Are street vendors really innovative toward self-service technology?” The authors argue that street vending has acquired great importance in present times. This study attempts to link consumer innovativeness (CI) to street vending – an ancient occupation now emerging as a new market form using technology and innovation. Specifically, the authors investigate the behavior of street vendors (a group hypothesized to enjoy more innovativeness than those with similar socioeconomic backgrounds) regarding adoption of SSTs in the retail banking industry. Using survey and in-depth interviews, data from representatives of the two groups (street vendors and formal wage workers) were used to determine the awareness levels, usage, primary sources of information, and reasons behind the adoption of the three SSTs considered along with their dependence on opinion leaders for making adoption decisions. The findings reveal that street vendors exhibit lower levels of innovativeness toward SSTs, and consumers are driven by three prime correlates of age, gender, and income. Further, it was found that informal groups of street vendors earn higher income despite being less qualified technically or otherwise than the formal sector wage earners within their social class. One of the major implications is that practitioners revisit their existing marketing strategies and policies to increase the reach of SST among urban lower middle class in India.

6. Conclusion

The special issue presents theoretical models on ICT4D in less-developed nations. Obviously although ICT has been touted as key driver for democracy and social and economic development of nations and individuals, it has also ancillary benefits for organizations. In particular, both citizens and businesses can benefit from use of e-commerce and mobile commerce. However, there is scant literature on organizational issues of ICT4D. It appears the focus on economic benefits may contribute to this scarcity. We have presented a framework that considers a broader view of the stages of impact and different levels of outcomes to investigate ICT4D in less-developed economies with microenterprises and SMEs as core organizations. Some scholars question whether ICT4D literature benefits Western scholars. This is important because while developing, transition, and emerging economies can benefit from literature from the developed nations, the reverse can be useful. Thus in general while the research studies presented in this special issue were focused on the developing, transition and emerging economies, they have useful implications for the developed nations especially for regions with limited resources and capabilities. A concern of Western research infiltrating or authoring most of the ICT4D research in less-developed nations is also addressed in that most of the studies presented in the special were performed by scholars living and working in less-developed economies. All together articles in this special issue covered theoretical and conceptual issues with ICT4D in each type of less-developed nations. In addition, most of the studies investigated SMEs and microenterprises that are foundation for development in these economies but generally neglected from ICT research in general.

Acknowledgements

The guest editor of this special issue would like to thank Sajda Qureshi, Narcyz Roztocki, Roland Weistroffer, and Joseph Nwankpa for their comments on earlier versions of this editorial.

References

- Asamoah, D., Andoh-Baidoo, F. K., & Agyei-Owusu, B. (2015). Impact of ERP implementation on business process outcomes: A replication of a United States study in a Sub-Saharan African Nation. AIS Transactions on Replication Research, 1(1), 4, 1–19.

- Arnold, D. J., & Quelch, J. A. (1998). New strategies in emerging markets. MIT Sloan Management Review, 40 (1), 7–20.

- Avgerou, C. (2010). Discourses on ICT and development. Information Technologies & International Development, 6 (3), 1–18.

- Berthon, P., Pitt, L., Ewing, M., & Carr, C. L. (2002). Potential research space in MIS: A framework for envisioning and evaluating research replication, extension, and generation. Information Systems Research, 13(4), 416–427.

- Brown, A. E., & Grant, G. G. (2010). Highlighting the duality of the ICT and development research agenda. Information Technology for Development, 16(2), 96–111.

- DFID. (2009). Building the evidence to reduce poverty. London: Department for International Development. Retrieved from https://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications/evaluation/evaluation-policy.pdf

- Duncombe, R. (2006). Using the livelihoods framework to analyze ICT applications for poverty reduction through microenterprise. Information Technologies & International Development, 3(3), 81–100.

- Fichman, R. G. (2000). The diffusion and assimilation of information technology innovations. Framing the domains of IT management: Projecting the future through the past, 1–42.

- Gillwald, A., & Stork, C. (2008). ICT access and usage in Africa.

- Heeks, R. (2008). ICT4D 2.0: The next phase of applying ICT for international development. Computer, 41(6), 26–33.

- Heeks, R. (2009). Worldwide expenditure on ICT4D. ICTs for development talking about information and communication technologies and socio-economic development. Retrieved from https://ict4dblog.wordpress.com/2009/04/06/worldwide-expenditure-on-ict4d/

- Heeks, R. (2010). Do information and communication technologies (ICTs) contribute to development?. Journal of International Development, 22 (5), 625–640.

- Heeks, R., & Molla, A. (2009). Impact assessment of ICT-for-development projects: A compendium of approaches. Development Informatics Group, Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester.

- Huang, Z., & Palvia, P. (2001). ERP implementation issues in advanced and developing countries. Business Process Management Journal, 7, 276–284.

- Joia, L. A., Davison, R., Diaz Andrade, A., Urquhart, C., & Kah, M. (2011). Self-marginalized or uninvited? The absence of indigenous researchers in the arena of globalized ICT4D research. (December 6, 2011). ICIS 2011 Proceedings. Paper 8.Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2011/proceedings/panels/8

- Kamal, M., Good, T., & Qureshi, S. (2009, January). Development outcomes from IT adoption in micro-enterprises. In System Sciences, 2009. HICSS’09. 42nd Hawaii International Conference on (pp. 1–10). IEEE.

- Kamal, M., & Qureshi, S. (2009). How can information and communication technology bring about development? An information architecture for guiding interventions in developing regions. AMCIS 2009 Proceedings, 188.

- Kleine, D., 2010. ICT4WHAT? – Using the choice framework to operationalize the capability approach to development. Journal of International Development, 22(5), 674–692.

- Kowal, J., & Roztocki, N. (2013). Information and communication technology management for global competitiveness and economic growth in emerging economies. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 57, 1–12.

- Mpogole, H., Usanga, H., & Tedre, M. (2008). Mobile phones and poverty alleviation: A survey study in rural Tanzania. In Proceedings of 1st International Conference on M4D Mobile Communication Technology for Development.

- Muriithi, N., & Crawford, L. (2003). Approaches to project management in Africa: implications for international development projects. International Journal of Project Management, 21(5), 309–319.

- Ngwenyama, O., Andoh-Baidoo, F. K., Bollou, F., & Morawczynski, O. (2006). Is there a relationship between ICT, health, education and development? An empirical analysis of five West African countries from 1997–2003. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 23, 1–11.

- Prakash, A., & De', R. (2007). Importance of development context in ICT4D projects: A study of computerization of land records in India. Information Technology & People, 20(3), 262–281.

- Qureshi, S. (2011). Information technology for development in expanding capabilities. Information Technology for Development, 17(2), 91–94.

- Qureshi, S. (2015). Are we making a better world with information and communication technology for development (ICT4D) research? Findings from the field and theory building. Information Technology for Development, 21(4), 511–522.

- Raiti, G. C. (2006). The lost sheep of ICT4D literature. Information Technologies & International Development, 3(4), 1–7.

- Roztocki, N., & Weistroffer, H. R. (2008). Information technology investments in emerging economies. Information Technology for Development, 14, 1–10.

- Roztocki, N., & Weistroffer, H. R. (2009). Research trends in information and communications technology in developing, emerging and transition economies. Collegium of Economic Analysis, 20, 113–127.

- Roztocki, N., & Weistroffer, H. R. (2011). Information technology success factors and models in developing and emerging economies. Information Technology for Development, 17, 163–167.

- Roztocki, N., & Weistroffer, H. R. (2015). Information and communication technology in transition economies: An assessment of research trends. Information Technology for Development, 21(3), 330–364.

- Tsang, E. W., & Kwan, K. M. (1999). Replication and theory development in organizational science: A critical realist perspective. Academy of Management review, 24(4), 759–780.

- Walsham, G., & Sahay, S. (2006). Research on information systems in developing countries: Current landscape and future prospects. Information Technology for Development, 12(1), 7–24.

- World Bank. (2014). World Development Indicators. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/wdi-2014-book.pdf