Introduction

In the past year and especially more recently, multitudes of people around the world have been in protest. Protest against the will of the people in the United Kingdom for the vote to exit the European Union. Protests against the United States’ election of a President and politicians who propose xenophobic, and isolationist policies. The largest of these were the protests against the denial of women’s rights. Women’s marches on 21 January 2017, took place around the world starting in Washington, DC with over 500,000 peaceful protesters, 750,000 in Los Angeles, 250,000 in Chicago, 200,000 in New York City, and 100,000 in Boston with additional marches in many other cities all over the country. These became known as the largest recorded marches in United States (US) history. Around the world people marched in London, in the United Kingdom, Sydney in Australia, Auckland in New Zealand, Berlin in Germany, Paris in France, Nairobi in Kenya, Cape Town in South Africa, and as far away as Antarctica. USA today reported that more than 2.9 million people across world took part in 673 marches in all 50 states and 32 countries to protest the first full day of the newly elected president (Przybyla & Schouten, Citation2017). In Mexico City, Mexico, the marchers were joined by American citizens and other nationals hoping to show their support for a more inclusive civil society.

Propelled by fear that the new administration will roll back reproductive, civil and human rights, the protesters peacefully called for a revolution. This revolution began as a Facebook post the day after the election and has swelled into a massive movement unifying demonstrators around issues like reproductive rights, immigration and civil rights (Hartocollis, Alcindor, & Chokshi, Citation2017). A revolution that marks an awakening to a reality that has been in the works for some time. My colleague who attended a Women’s march in Omaha, Nebraska, with his teenage daughter, commented on how the posters, hand-crafted by the protesters, were all different and illustrated a unity of motivation, but a lack of centralized orchestration, indicating a genuine spirit and initiative among the participants. With all the uniquely different posters around the world, it appears that the principal sentiment was that of unity. Struck by their originality, a professor at Northeastern University who stopped to admire the discarded signs at Boston common after the Women’s march there, decided that they had to be saved. So, he collected the signs, and they filled a 40-square foot storage unit (Zamudio-Suaréz, Citation2017).

However, there are limits to what such protests can achieve. After attending the protests in Washington, DC, Ioffe (Citation2017) reports:

a vague, unstructured cause; too much diversity of purpose; no real political path forward; and the real potential for the meaning of the day to melt into self-congratulatory complacency. Rallying and making funny signs is easy; winning real power in American politics is not. (Ioffe, Citation2017, p. 3)

She notes that while popular demonstrations can bring change and topple governments, they can also spark retaliation from those in power. Unless those in power are willing to listen and work toward addressing the issues, the protesters “may end up back where they started: on the streets and unheard” (Ioffe, Citation2017, p. 5). Protests may, especially in some countries like Russia and Egypt, bring about greater limits to the freedom to protest, greater limits to the use of social media to express dissent and greater authoritarianism in governments. In Tunisia, the protests became violent and led to the overthrow of an unpopular government which had been sought for by the people. In the United States, say my friends, democracy is bottom up, we fight for our personal freedoms, and do not tolerate authoritarianism.

Eerily prescient of our times, Jane Jacobs writes of a mass amnesia in which a society forgets the very pillars that made it great, such as community, education, science, and the professions that maintain the common welfare. When these pillars become unraveled, a world is created where every new outrage quickly leads to another, where the facts have no meaning (Jacobs, Citation2010). The social issues surrounding such protests are not unique to the United States. Uprisings fueled by popular discontent on social issues have taken place in recent years in Russia, the Middle East, Latin America and Africa.

This Journal has published on the effects of social media in enabling people to come together to have their voices heard and bring about change. Whether these uprisings enable the change that protesters hope for remains to be seen. The marginalized in Brazil have arisen, using social media to bring about improvements in their lives (Antonio Joia, Citation2016; Nemer, Citation2016). Kamel (Citation2013) reports on Egypt’s ongoing uprisings and notes that while the uprisings can topple governments, the role of social media to improve their lives may be minimal. In her ethnographic study of an online development-oriented network project, McLennan (Citation2016) explores a new form of networked “information colonialism,” or “Information Imperialism,” that offers paradoxes in online networking through social media. In view of these findings, Nicholson, Nugroho, and Rangaswamy (Citation2016) offer a compelling discussion of the role of social media in the development discourse. In this regard, the role of public access computing in enabling civic engagement and voices to be heard cannot be underestimated (Baron & Gomez, Citation2013; Qureshi, Citation2013). Given these findings, if social media may be able to effect change, how does this change translate into institutions that effectively implement and manage it?

The essence of the mass discontent on social issues has its roots in economic decline. There has been evidence to suggest that economic discontent and political behavior are connected (Caren, Gaby, & Herrold, Citation2017; Edwards & Foley, Citation1997; Kentor, Citation2001; Kotz, 2002; Nafziger & Auvinen, Citation2002; Williams, Citation2017). The key source of discontent in our time dates back to the 1970s’ economic restructuring and the dismantling of the welfare state, thus bringing about uneven access to social capital and other resources needed for survival (Edwards & Foley, Citation1997; Putnam, Citation1995). Putnam (Citation1995) argues that social capital has been on the decline for a number of reasons, especially the technological transformation of leisure as more people spend time in front of television, their phones and iPads, workers are also putting in longer hours, leaving less time to connect in their communities. The creation of social capital requires civic engagement and for people to be part of civic institutions, such as Parent Teacher Associations and the Red Cross, that lead to the creation of social capital. Democracies rely on civil society to function effectively and social capital to survive. With a decline of middle class around the world, both are in short supply.

Economic decline has been in the making for some time. Globalization marked by free trade agreements, technological advances and cheaper access to resources the world over has led to greater inequalities in wealth and opportunities. The aggregate Gross Domestic Products (GDP) of these countries have risen, and in some cases such as Brazil, China, and India, the growth rates have been dramatic. However, the distribution of wealth has been uneven in most of the countries that are providers as well as those that are the customers of outsourcing. The outsourcing of jobs from the more technologically advanced western countries to the eastern and southern countries has brought about structural unemployment in industries where jobs used to be secure. Now these same skilled employees are forced to work for lower wages and sometimes minimum wages for the same work. Such wages can no longer be considered a living wage in the big cities of North America, the United Kingdom and Europe. Technological advances, especially the creation of the internet protocol in 1972, development of the World Wide Web in the 1980s and its privatization in 1995 to bring about electronic commerce, have brought about a whole new revolution, often referred to as the information revolution. Despite the growth powered by the information revolution, the blue collar and skilled workers of the industries that have moved their businesses overseas are not able to gain employment in the Information Technology (IT) sector. Training programs have not been widely accessible to these workers.

The rise of populist governments offering isolationist policies appears to be a reaction to the era of free trade, income inequality, declining incomes and the demise of the middle class with dwindling social services to help the unemployed. This editorial explores the factors that have awakened multitudes to the social forces leading to discontent and economic demise. Technological process and the opportunities offered by information and communication technologies (ICTs) to bring about improvements in people’s lives are assessed in the light of recent events. A theoretical lens is offered to assist scholars and policy-makers in being more inclusive when investigating the effects of ICTs on Development.

Roots of discontent and technological progress

There is massive discontent on both sides of the political divide. Economic resentment has fueled racial anxiety not just in the United States but also in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, other European countries, and even some countries in South East Asia. It is important to understand that open racism is a symptom of economic demise. Governments have focused on taking care of the poor and in doing so have alienated their dwindling supply of middle-class taxpayers. These are the large populations that have been forgotten by governments in their well-meaning efforts to offer symptomatic relief to rising populations of disenfranchised poor. Scholars investigating poverty in far away places overlook the large segments of the unemployed or underemployed in the manufacturing and mining sectors of their own countries, such as in USA, and the despair of labor in Europe, which is faced with increasing competition from skilled immigrants. Joan Williams, a Distinguished Professor of Law and Founding Director of the Center of Work Life Law at the University of California, helps us to understand the roots of discontent in the United States well:

My father-in-law grew up eating blood soup. He hated it, whether because of the taste or the humiliation, I never knew. His alcoholic father regularly drank up the family wage, and the family was often short on food money. They were evicted from apartment after apartment.

He dropped out of school in eighth grade to help support the family. Eventually he got a good, steady job he truly hated, as an inspector in a factory that made those machines that measure humidity levels in museums. He tried to open several businesses on the side but none worked, so he kept that job for 38 years. He rose from poverty to a middle-class life: the car, the house, two kids in Catholic school, the wife who worked only part-time. He worked incessantly. He had two jobs in addition to his full-time position, one doing yard work for a local magnate and another hauling trash to the dump.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he read The Wall Street Journal and voted Republican. He was a man before his time: a blue-collar white man who thought the union was a bunch of jokers who took your money and never gave you anything in return. Starting in 1970, many blue-collar whites followed his example. This week, their candidate won the presidency.

:

Trump’s blunt talk taps into another blue-collar value: straight talk … Manly dignity is a big deal for most men. For many blue-collar men, all they’re asking for is basic human dignity (male varietal). Trump promises to deliver it.

:

Both parties have supported free-trade deals because of the net positive GDP gains, overlooking the blue-collar workers who lost work as jobs left for Mexico or Vietnam. These are precisely the voters in the crucial swing states of Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania that Democrats have so long ignored. (Williams, Citation2017, p. 3–5)

At the root of this economic discontent is the dichotomy between the working class and the poor. Williams adds that we need to understand that working class means middle class not poor (Williams, Citation2017, p. 4). Government and economic development efforts have focused on the poor by taxing the working middle classes to offer paid sick leave and healthcare to the poor. Meanwhile, with the lack of steady, stable full-time jobs, increasing social benefits does not help the middle-class worker, who is now falling into the working class. There is working-class resentment of the poor, which she illustrates as follows:

So my sister-in-law worked full-time for Head Start, providing free child care for poor women while earning so little that she almost couldn’t pay for her own. She resented this, especially the fact that some of the kids’ moms did not work. One arrived late one day to pick up her child, carrying shopping bags from Macy’s. My sister-in-law was livid. (Williams, Citation2017, p. 4)

Rising inequality, between a few people and corporations that own the majority of factors of production, and the larger numbers of people who are unable to survive on their incomes, has brought about greater political instability. With the decline in the working middle classes and their tax revenues, access to social services such as healthcare and education in countries where these have been a right, not a privilege, continues to decline. The demise of the middle class has been accentuated by more people in the work force struggling to survive. Caren et al. (Citation2017) contend that material adversity is a reoccurring precondition of anti-state mobilization. They tested the effect of economic decline on the count of large-scale, anti-government demonstrations, and riots. Using multiple sources of newspaper reports of contentious events across 145 countries during the period 1960–2006, they found a statistically significant negative relationship between economic growth and the number of contentious events, controlling for a variety of state-governance, demographic, and media characteristics. They found that the effect is strongest under conditions of extreme economic decline and in non-democracies. Economic growth becomes very difficult to achieve where there is a lack of a middle class and there is significant income equality. Kaplan (Citation1994) adds that scarcity, crime, overpopulation, tribalism, and disease are destroying the social fabric of our planet. He adds that crime and war have become almost indistinguishable from national defense. Within countries in which the social fabric is decaying, the role of the internet in facilitating additional perils as scams, viruses, identity theft, child online exploitation, and terrorism become commonplace.

At the same time, increasing productivity due to technological advances in IT has meant that aggregate wealth is increasing in countries around the world. For example, Facebook has 15,724 employees who generated 12.46 billion US dollars in revenue in 2016. That is 792,419.23 US dollars generated per employee. Google has 61,814 employees who generated 20.76 billion US dollars in 2016. That is 335,846.25 US dollars generated per employee. Alphabet, the parent company of Google, reported a revenue of 74.98 billion US dollars in 2015 and about 61,000 employees. That would be about 1,229,180 US dollars per employee. Alibaba a Chinese retail business had a revenue of 15.69 billion US dollars in 2016 over 34,985 employees making 448,477.92 US dollars per employee. Rising productivity per worker in the technology sector has brought about immense prosperity for the shareholders and a few who work in these jobs. Employment in this sector requires high levels of skill and often very specific expertise that is in short supply. This contributes to the widening gap between the rich and poor.

The effects of neoliberal globalization on poverty

While individual government efforts have focused on limited programs for the poor, some argue that it is the neoliberal economic policies enforced from the United States to the rest of the world since the 1980s that have in fact contributed to creating poverty (Economist, Citation2016; Escobar, Citation2011; Fenelon & Hall, Citation2008; George, Citation2007; Kotz, Citation2000; Kentor, Citation2001). The goal of neoliberal economic policies is the removal of barriers to commerce between the nations of the world, privatization of social services and state-owned enterprises, and deregulation. The concept of neoliberalism is about free trade and belief that the invisible hand of the free market will create a more prosperous world. It replaces the concept of public good or community property with individual responsibility.

Free trade agreements such as the North Atlantic Free Trade Association (NAFTA), the European Economic Market, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations economic community all work toward an integrated global economic community in which there are no barriers to trade, goods, and services move freely and people learn to fend for themselves. International institutions enforce the neoliberal world order through the World Trade Organization, which is tasked with eliminating all barriers to global free trade, and the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), which ensure the liberalization of domestic capital accounts and privatization of the developing economies in the south. Escobar (Citation2011) argues that it is the loans made through the World Bank and IMF on expensive unnecessary infrastructure projects to developing countries that have increased the burden on the poor of those countries. The poor have to pay higher taxes so that their cash-strapped governments can pay back the high interest loans to the World Bank. In so doing, argues Escobar (Citation2011), the World Bank continues to create and re-create the vicious cycle of poverty in which people find themselves with no social safety nets to help them out.

By promoting global free trade agreements enforced through international institutions, neoliberalism has skewed the global economic order in favor of the multi-national corporations. Small businesses which have been the seedbed of industrialization and have also been the only means out of poverty for many people all over the world have died as the mega corporations take over. For example, in Mexico City, the markets in which micro-entrepreneurs and small business would operate have died. Walmart stores replaced them with cheaper process and greater selection of goods. At the same time, the workers in Walmart across the US work longer hours and make less than a living wage. An immediate result of NAFTA is that Latin American farmers have been replaced by Monsanto and similar mega corporations. In desperation, the farmers migrate to the US looking for work. With the decline in healthcare, education and other social services, the US workers feel that their livelihoods are threatened. In fact, it is difficult to compete with the desperate migrant workers who will work for below minimum wage just to feed their families. The Economist weighs in on this by stating:

Liberal and social-democratic political theory both are marked by a peculiar hopeful naivete about the possibility of one day arriving at some sort of ideal self-equilibrating politico-economic system. But it's never going to happen. (Economist, Citation2011, p. 4)

In his study of the long-term Effects of Globalization on Income Inequality, Population Growth, and Economic Development, Kentor (Citation2001) used cross-national comparisons among 88 less developed countries, and constructed a series of structural equation models to estimate the effects of two aspects of globalization, foreign capital dependence and trade openness, on these three domestic concerns between 1980 and 1997. He found that foreign capital dependence increases income inequality, raises fertility rates, accelerates population growth, and retards economic development. This threat of political instability discourages investment, which slows economic growth. He adds that higher levels of inequality are likely to generate political instability, resulting in policies that favor redistribution of income. At the same time, gross domestic investment, Kentor (Citation2001) found, leads to a decrease in inequality. Trade openness, in contrast, has long-term positive effects on economic development. This means that when government invest in their people and infrastructure, more equitable growth can be achieved.

The free movement of debt capital causes global economic instability such as the subprime mortgage crisis that led to the Great Recession, and is one reason why the EU’s most ambitious cross-border initiative, the euro, which has joined 19 of its 28 members in a currency union, is in trouble according to the Economist (Citation2016). In his study of GDP and labor productivity growth rates, Kotz (Citation2000) found that:

the neoliberal model is inferior to the state regulationist model for key dimensions of capitalist economic performance. There is ample evidence that the neoliberal model has shifted income and wealth in the direction of the already wealthy. However, the ability to shift income upward has limits in an economy that is not growing rapidly. Neoliberalism does not appear to be delivering the goods in the ways that matter the most for capitalism’s long-run stability and survival. (Kotz, Citation2000, p. 5)

It appears that the net effect of neoliberal globalization has been to increase poverty in parts of the world. The populism and mass discontent appear to be a reaction to its effects. Fenelon and Hall (Citation2008) frame the struggles for autonomy and cultural survival of the indigenous people of the Lakota and Wampanoag in the United States, the Adivasi in India, the Maori in New Zealand, Zapotecs and Zapatista-led Mayan (e.g. Tzotzil) peoples in Mexico, the Mapuche, the Guarani, and several others in Latin America within a larger context of historical forces of globalization. Even Escobar (Citation2011) notes that indigenous farming methods are being used to combat the effects of climate change. He argues that climate change in some parts of the world has been caused by World Bank-financed dams that diverted water from agricultural areas, which now face droughts as a result of the dams.

Recent analysis by Oxfam of data gathered by Credit Suisse shows that the poor are getting poorer and just eight of the richest people on earth own as much combined wealth as half the human race. This analysis was presented at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland (Mullany, Citation2017). Interestingly enough, this forum is where many of the richest are often among the attendees, along with diplomats, political figures, and business and cultural leaders who come together to discuss ways to alleviate poverty in the world. While having benefitted from free trade, deregulation, and limited government ownership and interventions, the richest people understand that sustained growth and prosperity require investments in infrastructure and services such as healthcare and education by governments.

Role of ICTs and development research

Against this backdrop, the role of scholars in studying the effects of ICTs in development is more important than ever. ICTs have been powering the increased integration of world economies through social media to form connections among people in different parts of the world, mobile phones to run small businesses by accessing resources and customers, and broadband internet accessed through cyber cafes and telecenters to enable people to gain literacy and skill sets they would otherwise have no access to. Steinberg (Citation2003) suggests that ICT is highly versatile and can help support development efforts if employed judiciously. In addition to the usage of ICTs to connect people in order to promote the transformation of small businesses and social development, ICTs may also be harnessed for more strategic purposes. Thompson and Walsham (Citation2010) call for an engagement in a strategic, policy-level debate about the transformative potential of ICT within broader developmental agendas. They see ICT as an institutional infrastructure enabler; ICT as enabler for governance, accountability, and civil society; as an enabler for service production and economic activity; and finally as an enabler for access to global markets and resources.

The term ICT4D denotes a collection of technologies that can be used to stimulate development. Assessing the potential value of ICTs in supporting development efforts requires us to address (1) the extent to which ICTs can enrich people’s lives by bringing ideas and experiences to those in the most isolated villages; (2) the technology’s record with respect to achieving specific development objectives; and (3) its contribution to overall development and sustainability (Steinberg, Citation2003). The challenge here is to understand how ICTs can be used to add value. The current debates on reversing the trends toward the outsourcing of low-value jobs from the US and OECD countries to those where the costs of skilled labor and ICT infrastructures are low, miss the real argument, which is the lack of investment in higher value-added ICT-supported activities in the latter countries. The failure of some countries, such as the US to invest in value-added ICT-supported skills, infrastructure, and technologies suggests that it is a failure of neoliberal focus on economic gains and free trade, rather than public policy within countries to add value using ICT-supported activities within the sectors of the economy.

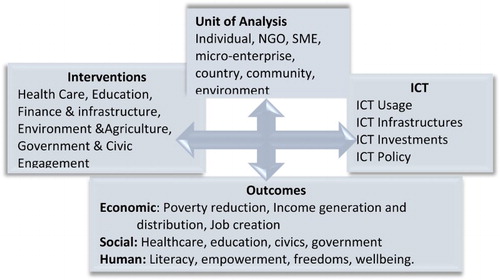

ICTs have enabled people to achieve improvements in their lives. Leong, Pan, Newell, and Cui (Citation2016) explore the recent emergence of e-commerce villages in rural China. The emergence of Alibaba’s Taobao (e-commerce) Villages in remote China has challenged the assumption that rural, underserved communities must always be the recipients of aid to stimulate ICT-enabled development. By taking an inclusive view by studying the ecosystem of rural e-commerce, they show how ICT (e-commerce) can empower a marginalized community, giving rise to a rural e-commerce ecosystem that can aid self-development. Srivardhini, Pinsonneault, & Dube (Citation2016) also found that the evolution of an ICT-supported ecosystem in eKutir India, progressively evolves and reinforces the businesses within it to create a system that is economically sustainable, scalable, and can accelerate transformative change. Information Systems (IS) scholars have offered theoretical, analytic, and methodological tools to better understand the effects of ICTs on achieving improvements in people’s lives (Leong et al. Citation2016; Lin, Kuo, & Myers, Citation2015; Njihia & Merali, Citation2013). However, this stream of research has yet to articulate what development outcomes their research contributes to. offers a theoretical lens or view toward investigating ICTs in ways that offer development outcomes.

This lens offers a view through which interventions often seen as projects in which ICTs are used to support healthcare, education or agriculture are investigated. While the use of ICTs is often the subject of many studies, the success of an ICT project does depend upon the type of ICT infrastructures, level of investments in ICTs and policies. While all too often country studies are offered as a means of generalizing outcomes, it is important to carefully select the unit of analysis which may actually change the way in which a phenomenon is studied. The units of analysis range from Individual, NGO, small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), micro-enterprise, country, community, and environment. Selecting the appropriate development outcome can have a significant impact on the type of contribution a study makes. These are described in the following sub-sections.

Study of economic development outcomes

In the context of neoliberal globalization which aims to power economic growth, economic development is different. Economic development is about equitable distribution of resources in an economy where economic growth is simply the rise in GDP of a nation. The concept of development has its roots in the economics of the firm. Economic Development is defined as “the interruption of the business cycle” according to Schumpeter (Citation1932) and is often used to describe growth in organizations and the regions in which they reside. The outcomes from the adoption of ICT on development can be assessed in a number of ways. The measures of economic development in micro-enterprises most often used are: increase in income, job creation, and clientele (Qureshi, Kamal, & Wolcott, Citation2009).

Some of the most commonly used indicators of economic development at the country level are: the GDP, or a country’s income, which is calculated in millions of US dollars. Given that GDP may not reflect cost of living, the Purchasing Power Parity offers a measure of the real value of output produced by an economy compared to other economies. Perhaps the most important is the Gini coefficient, which measures the disparities in income within a country (World Bank, Citation2015). May, Dutton, and Munyakazi (Citation2014) offer a multi-dimensional view of poverty in which they used monetary metrics, including the Gini coefficient together with human capital indicators to investigate poverty in a set of east African countries. They found that while financial poverty increased in the countries they studied, some countries, such as Kenya, saw an increase in human capital. Kenya has the largest number of users in the world of mobile payment systems, primarily through M-Pesa.

Study of social and human development outcomes

Social Development is a concept of development in social science that explores how reality is constituted in the development process (Arce, Citation2003). The social development perspective enables a broader understanding of development to be achieved through top-down national policy-making processes and bottom-up, “micro level” traditions like the actor-network approaches, which works upward from individual level actions (Arce, Citation2003). Social development activities are designed to raise living standards, increase local participation in development and address the needs of vulnerable and oppressed groups (Midgley, Citation2003).

While social development efforts relate to building and working with institutions of government, healthcare, education, finance, and the environment/agriculture, the concept of Human Development is about enlarging individual people’s choices so that they may have the freedom to pursue the lives they value (Sen, Citation2001). In this, income is seen to be an instrument of this freedom to pursue their well-being. Sen argues that there needs to be a broad set of conditions that include access to food, shelter, health, and education that together constitute well-being (Sen, Citation2001). While well-being may vary considerably between individuals, indicators to measure well-being include the United Nations Human Development Index, the Gender Development Index (GDI), and the Human Poverty Index.

There are a number of different ways in which development outcomes are studied in ITD/ICT4D research. Country studies are prevalent in ICT4D research. Examples of such studies are ICTs measured in terms of penetration of mobile phones, broadband internet, TVs, radio, and landlines, all of which may enable the capabilities of citizens to achieve well-being. There are a number of indicators, based on Sen (Citation2001) and others which are used to assess the ability of a country to provide its people with basic “freedoms.” These are (1) rights of political participation and freedom of speech; (2) economic opportunities to participate in trade; (3) social opportunities of adequate health and education; (4) openness in government; and (5) security in the form of law and order and basic social safety nets for the unemployed.

NGOs, SMEs, and micro-enterprises

The use of ICTs by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), SMEs has been shown to enable growth, particularly through sustained technology and training interventions (Kamal & Qureshi, Citation2009; Qureshi, Kamal, & Wolcott, Citation2010). Micro, small and medium enterprises, as well as Social Enterprises and NGOs, appear to be at the heart of efforts to understand the effects of ICTs on Development. Case studies and vignettes of how these micro-enterprises use technology to grow throw valuable light on the needs of people in their communities. While the definition of these forms of organization varies between countries, it has been argued that they are more efficient at creating quality jobs, are more innovative, or grow faster than larger firms (Gibson & Van der Vaart, Citation2008). Seen as a form of small business, social enterprises and NGOs are also key players in enabling ICT usage to support better livelihoods. Their activities offer non-profit earned income, which in turn provides consistent cash flow to further the mission of the organization (Lyons, Townsend, Sullivan, & Drago, Citation2010).

In particular, the use of mobile phones in micro-enterprises has been shown to increase the well-being of their micro-entrepreneurs by bringing about greater price transparency and elimination of waste (Donner & Escobari, Citation2010; Duncombe & Heeks, Citation2002). It has been argued that mobile devices represent a way for entrepreneurs to overcome the challenges of doing business as they support communication, enable market information to be accessed, reach new customers, sell their products across geographic areas, get paid through mobile payment systems and empower women (Aker & Mbiti, Citation2010; Chew, Ilavarasan, & Levy, Citation2013; Donner & Escobari, Citation2010; Duncombe, Citation2011). While the majority of studies focus on the explosive growth of mobile phone usage in Africa, Asia and Latin America, few if any, consider the effect of this ubiquitous technology on the well-being of people in North America and Europe. In his review of the literature on mobile usage, Donner (Citation2008) categorized these studies into mobile adoption, mobile impact, and mobile interrelationships. He found that ICTD studies consider mobile adoption through digital divide, mobile impact on economic growth and livelihoods, and mobile interrelationships through the evaluation or design of ICTD projects. In particular, mobile phones can be used in multiple ways to bring about improvements in people’s lives while also causing harm.

Donner (Citation2008) categorized Information Systems studies as non-ICTD studies which consider the interactions between people and technology with little contribution to development. Duncombe (Citation2011) adds that while mobile phone technology is increasingly becoming a key tool for development, the effects of “m-development” interventions are difficult to measure and often focus on local outcomes. He suggests that the contributions of mobile phone interventions should move from assessing outputs to outcomes and to assessing their impact. In particular, when studying the development outcomes of micro-entrepreneurs who own and make use of mobile phones, a range of indicators can be used such as sales, volume, profit, and market share. At the same time, such outcomes are relatively difficult to define and identify, and the reliability of data may be open to question due to lack of access to enterprise income and resources.

Broader contributions

Now that the effects of globalization are permeating multiple facets of life, the relevance of ICD4D research for the broader community of scholars in other fields has become more apparent. ICT4D research provides a relevant context with measures, levels of and units of analysis that can inform research in ways that may offer contributions to global information systems which comprise multiple geographic, cultural, and functional contexts. Widely studied in the ICT4D field are cases, vignettes and studies of how entrepreneurs in villages and city slums use mobile phones to achieve better livelihoods, such as fishermen and farmers arriving at better markets through access to information they would not have had without the access to ICTs. Women in remote villages in Africa made money by charging villagers for the use of their mobile phones. Now known as telephone ladies, they made enough money to start up and run successful business from profits made from selling their mobile phone time (Donner, Citation2008; Donner & Escobari, Citation2010; Qureshi et al., Citation2009). In drawing upon these studies, we can move development discourse forward by offering meaningful theoretical and technological contributions for people living in poverty in the US and Europe with little or no access to ICTs, such as mobile payment systems that have helped so many to come out of poverty in Africa and Asia.

Information systems are often relied on to assist in the growth of businesses. However, small and micro businesses often find technology difficult to implement due to resource constraints (Street & Meister, Citation2004). Street and Meister (Citation2004) point out the important role of IS in small businesses development and growth. They find that internal transparency may well be a concept that offers significant potential for IS research. Effective IT interventions may have considerable potential for facilitating IT adoption among micro-enterprises across the United States and the world through the use of a low-cost option such as cloud computing (Qureshi & Kamal, Citation2011; Song & Qureshi, Citation2010). Kamal and Qureshi (Citation2009) explore two trends relating to how ICT adoption in micro-enterprises can bring about development. First, micro-enterprises contribute to both economic and social development. Second, ICT can facilitate achievement of an underserved region’s development strategies. Research from both these trends, and their intersection, can offer contributions to the IS researcher. Such contributions entail the discovery of factors that can enable information systems outcomes to be assessed in terms of their success in enabling micro-enterprises to grow and offer strategies for improving the lives of people, in particular the micro-entrepreneur, through IS.

ICT4D contributions that bring about improvements in people’s lives

The papers in this issue take the field forward by offering contributions to the outcomes for ICT4D research and discovering new ways in which the innovative uses of ICTs may bring about development.

Geoff Walsham is the author of the first paper in this issue entitled “ICT4D research: reflections on history and future agenda.” It offers a synthesis of ICT4D in terms of both its history and future prospects. He offers a history of research on the use of ICTs for international development, or information and communication technology for development (ICT4D) research, going back some 30 years. The purpose of his paper is to take stock of the ICT4D research field at this important juncture in time, when ICTs are increasingly pervasive and when many different disciplines are involved in researching the area. The paper first provides some reflections on the history of the field broken down into three phases from the early beginnings in the mid-1980s, expanding horizons in the mid-1990s to mid-2000s and proliferation in the mid-2000s to the present day. This is followed by a detailed discussion of future research agenda, including topic selection, the role of theory, methodological issues and multidisciplinarity, and research impact. While ICT4D research started largely in the academic field of information systems, Walsham concludes that its future lies in a multidisciplinary interaction between researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers.

The second paper, entitled “Examining the ICT access effect on socioeconomic development: the moderating role of ICT use and skills” is authored by María Verónica Alderete. She argues that despite the considerable contributions of existing research in this domain, there is a lack of substantive research that examines the relationship at the country level between ICT access and ICT use, on the one hand, and ICT access and socioeconomic development, on the other. The paper is an attempt to fill this gap by using a methodology that captures these processes. This paper examines the role that ICT play in the socioeconomic development of countries. The proposed model analyzes the relationship between ICT access (available ICT infrastructure and individual’s access to ICT), ICT use (ICT intensity and usage, and ICT skills), and socioeconomic development. By means of a Structural Equation Model, the impact of ICT access on the socioeconomic development is moderated by the ICT use and skills. ICT skills refers to ICT learning, knowledge, and abilities. The higher the ICT skills, the better the ICT use is. Those countries with access to ICT but which are not capable of using them properly due to lack of adequate broadband bandwidth or knowledge resources would be unable to ensure all the effects of ICT on socioeconomic development. Country-level data across 163 countries for the year 2013 are used from developing to developed countries. Results obtained indicate the moderating role of ICT use and skills in the relationship between ICT access and the socioeconomic development. The ICT usage and ICT skills enhance the effect of ICT access on the socioeconomic development. The model is robust with respect to the development level.

Salah Kabanda and Irwin Brown co-author the third paper in this issue, entitled “Interrogating the effect of environmental factors on e-commerce institutionalization in Tanzania: a test and validation of small and medium enterprise claims.” The purpose of this study is to interrogate the claims made by SMEs in Tanzania regarding the environmental factors that negatively affect their institutionalization of e-commerce. SMEs made claims that there was a lack of institutional readiness for e-commerce in Tanzania, as well as inadequate market forces readiness, supporting industry readiness, and sociocultural readiness. A content analysis approach was used to interrogate institutional policy documents to determine the frequency of use of specific arguments that either support or negate the SMEs’ claims. The theory of communicative action was used as a framework to analyze the truthfulness, sincerity, clarity, and legitimacy of the claims made. The findings from the content analysis show that the Tanzanian ICT policy and SME policy pay scant attention to e-commerce readiness factors. The validity claim analysis did not reveal distorted communications by SMEs, but rather corroborated their claims that indeed environmental factors were not conducive to the institutionalization of e-commerce in Tanzania. The study illustrates a means by which qualitative findings about the environment gathered from respondents may be corroborated. Specifically, this study proposes to validate Tanzanian SME claims that their low level of e-commerce adoption and institutionalization is as a result of the lack of government readiness, market forces readiness, supporting industry readiness, and sociocultural readiness.

The fourth paper, entitled “The evolution of Ghanaian Internet cafés, 2003–2014” by Matthew LeBlanc and Wesley Shrum explores two main perspectives that characterize current research on Internet cafés in the developing world. The “inclusionary” perspective represents these public digital spaces as the most important source of connectivity and inclusion for the global population. The “transitional” perspective represents Internet cafés as a dying business whose obituary is long overdue. This study describes a search for two dozen Internet cafés in Ghana, based on establishments first identified in 2003, accompanied by interviews with patrons and café attendants. Although other sources address the impact Mobile ICTs have had on various populations, none has systematically addressed the impact new communication technologies have had on the institution of the Internet cafe. In studying this gap, the authors investigate this issue in Accra, the capital of Ghana, using data collected in 2003 and 2014. The authors use a semiotic approach through extensive qualitative description focusing on the “sociology of associations”. They examine the narratives of both Internet cafe patrons and the staff. These narratives depict the flow of action among the associations present in the Internet cafes of this study.

Their initial exploration supported the transitional prediction that cafés would be shuttered or replaced by traditional businesses. However, an expanded search led them to the conclusion that “walking distance” replacements for all cafés remained available, supporting the inclusionary view. Smart phones, laptops, tablets, USB modems, and wireless routers have become less expensive and more accessible globally. It has been the increase in connectedness, in this view, that has resulted in the demise of the cyber café. With the average citizen gaining access to the global online community from their home or mobile, it has been speculated that Internet cafés are soon to become obsolete. Qualitative interviews revealed the shift of cyber cafés to business services and their continued importance as online spaces for disadvantaged populations. They conclude that although the introduction of smart phones and other affordable ICTs offers competition as alternatives to Internet Cafes, the business itself is by no means obsolete.

Frederick Riggins and David Weber co-author the fifth paper in this issue, entitled “Information asymmetries and identification bias in P2P social microlending.” The Internet has created new opportunities for peer-to-peer (P2P) social lending platforms, which have the potential to transform the way microfinance institutions raise and allocate funds used for poverty reduction. These P2P social lending networks are a subset of the growing phenomenon of web-based crowdfunding where these networks have a philanthropic goal of reducing poverty in developing regions of the world. Working in partnership with MFIs, P2P social lending networks provide ICT-enabled platforms that allow loan seekers to be connected with individual philanthropic lenders. Today, a couple in San Francisco can lend money to an entrepreneur tailor in Vietnam at low transaction costs through a P2P social lending platform and a loan-administering MFI. A well-known example of a P2P social lending network is Kiva (www.kiva.org) where individual philanthropic lenders can view a number of loan requests from entrepreneurs from around the globe and can quickly make microloans in increments of $25 using their PayPal accounts. As the world’s population becomes more connected through modern ICTs, the authors expect microfinance’s use of P2P lending networks to grow.

Riggins and Weber contend that while the growth of P2P lending platforms is an exciting development in the microfinance industry, there are certain problems that may occur with this new type of intermediary. In particular, information asymmetries may exist if the lender, often an individual in the West, does not have adequate information about the loan borrower, typically a small entrepreneur in a developing region of the world. They analyze individual Kiva loan transactions to measure whether the lending decision is influenced by identification bias. They test whether the amount of information describing the loan on the Kiva website influences the information asymmetry problem. If the amount of information about the loan helps to lessen information asymmetry, they would expect high-information project listings to show a positive correlation between time to fund and loan default, where quickly funded loans have a low default rate. On the other hand, if more information simply reinforces identification bias, they would expect high-information projects to exhibit more bias in lending and even less ability to predict loan success. Their analysis of this Kiva dataset shows that loans that get funded faster have a higher default rate, suggesting that distant lenders are not able to adequately predict the potential success of a loan project. Furthermore, they show that identification bias exists whereby the lender’s gender and occupation both influence lending decisions. Finally, for high-information loans, a negative and significant relationship exists whereby loans that have shorter time to fund actually have a higher default rate, suggesting that more information makes the lending community worse at predicting loan success, perhaps by increasing identification bias.

The sixth paper in this issue entitled “An exploratory study on mobile banking adoption in Indian metropolitan and urban areas: a scenario-based experiment” is co authored by Sumeet Gupta, Haejung Yun, Heng Xu and Hee-Woong Kim. As security concerns have thwarted the widespread adoption of mobile banking in India, in order to respond to the concerns of Indian banks and their customers, the authors present exploratory attempts to understand how the levels of security affect perceived risk and control and ultimately, adoption of mobile banking by Indian customers. This study also examines the moderating influence of the type of city on the relationship between security levels and risk/control perceptions associated with mobile banking. Because the pace of development and adoption of new technologies varies between metropolitan and other areas, the type of city is likely to influence the extent of mobile banking adoption. The authors examined the moderating influence of the type of city on the relationship between the level of security and the risk/control perceptions of adoption of mobile banking. Using a scenario-based experiment, they classified security-enhancing approaches into three categories and examined their effectiveness in decreasing Indian customers’ perceived risk, increasing their perceived control, and then in turn, facilitating mobile banking adoption. Their findings reveal the important role of perceived risk and control in influencing customers’ intention to adopt mobile banking. Moreover, perceived risk and control significantly influenced mobile banking adoption by customers in urban areas, but only perceived control significantly influenced mobile banking adoption by metropolitan customers. Additional analyses show that customers’ risk and control perceptions differ according to the level of security; however, these perceptions do not have a significant influence on risk and control. It appears that while security may be a concern with mobile banking, the increasing importance of virtual currencies could be used to improve security and reduce transaction costs associated with financial transactions.

“Understanding e-government failure in the developing country context: a process-oriented study” by Panom Gunawong and Ping Gao is the seventh paper in this issue. The authors suggest that e-government projects are complex and involve multiple tasks, including constructing a large-scale ICT infrastructure, restructuring public activities, and offering a broad range of public services. Because of their complexity, e-government projects generally risk undesirable outcomes, for example, budget overspending, falling behind schedule, fewer functions, and failure to achieve the original objectives of the project. Their research aims to investigate the underlying process-based causes of e-government failure. They conduct a case study of Thailand’s Smart ID Card project to enhance our understanding of the underlying process-based causes of e-government failure in the context of a developing country. Through the lens of actor-network theory, they present a process-oriented study of the failure of Thailand’s Smart ID Card project. Adding to the extant knowledge on e-government failures that attributes this phenomenon to internal and external factors, they argue that the reason the project failed was a cumulative process of failure to create and maintain the actor-network. Policy implications for developing countries to efficiently manage their e-government initiatives are given, such as adopting an open principle in setting e-government project objectives and initiating the actor-network; implementing the e-government target in stages based on prepared environment; allowing an e-government system to evolve according to the degree of readiness in the ICT system design, implementation and local adoption; and including large, nationwide projects as part of a national informatization strategy.

The final paper in this issue is in this Journal’s View from Practice section, entitled “The role of information and communication technology for development in Brazil.” It is co-authored by Rodrigo Fernandes Malaquias, Fernanda Francielle de Oliveira Malaquias and Yujong Hwang. As social, human and economic dimensions of development demand relevant attention in developing and developed countries, the authors explore the role of IT for development in an emerging economy: Brazil. The authors state that Brazil is one of the five major national emerging economies and it is the largest and most populous country in South America. It is a very diverse country and has unique challenges regarding public access to ICT. Brazilian territory is divided into five big regions. The more prominent differences in socioeconomic indexes among these regions are in the South and Southeast areas, which are the richest in Brazil, in comparison with the North and Northeast regions. Through their analysis and discussion, the authors highlight relevant issues to be considered by IS literature. For example, they observed IT advances in the health area, and these advances include telemedicine, applications focused on cancer, applications for prescription process, electrocardiogram in the clouds, and remote tele-monitoring of chronic patients. They found two initiatives in Brazil that help in the fight against cancer and HIV with IT use. These (and other) measures have a direct effect on social and human development. They suggest that special attention should be given to the importance of government actions and of the internet to leverage the relationship between IT investments and development in emerging economies.

Conclusion

This editorial has explored the factors that have awakened multitudes to the social forces that that led to discontent and economic demise. When working families, struggling to survive, are unable to access basic social services such as childcare, healthcare and education, it is argued that populism and mass discontent appear. For better or for worse, social media have a profound effect on mobilizing mass discontent. While ICTs have in fact increased productivity and wealth in many countries of the world, they have also been the cause of income inequality. The demise of the middle class, which is now the working class in most countries, is associated with the decline in civil society and social capital. These are essential for democracies to function. Free trade, deregulation and a limited social safety net have meant that the role of ICTs in bringing about improvements in peoples’ lives is more important than ever. The theoretical lens offers a means of investigating development outcomes from the ways in which ICTs permeate our lives. The papers in this issue offer ways in which such contributions may be used to bring about improvements in people’s lives.

Acknowledgements

I am extremely appreciative of Chris Mangen, a former editor at the San Diego Union Tribune and the Omaha World Herald, for his countless discussions of the issues and multiple reviews of earlier versions of this editorial. To Information Technology for Development editors, Shirin Madon, B.J. Reed, Peter Wolcott and Anthony Ming, I am most grateful for their insightful comments and keen acumen that ensure that I address the essential factors surrounding the topic of this editorial. It is because of editors and reviewers like them that we are able to continue to produce high-quality publications.

References

- Aker, J., & Mbiti, I. (2010). Mobile phones and economic development in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(3), 207–232. doi: 10.1257/jep.24.3.207

- Antonio Joia, L. (2016). Social media and the “20 cents movement” in Brazil: What lessons can be learnt from this? Information Technology For Development, 22(3), 2016. doi:10.1080/02681102.2015

- Arce, A. (2003). Re-approaching social development: A field of action between social life and policy process. Journal of International Development, 15(7), 845–861. doi: 10.1002/jid.1039

- Baron, L. F., & Gomez, R. (2013). Relationships and connectedness: Weak ties that help social inclusion through public access computing. Information Technology For Development, 19(4), 271–295. doi:10.1080/02681102.2012.755896

- Caren, N., Gaby, S., & Herrold, C. (2017, February). Economic breakdown and collective action. Social Problems, 64(1), 133–155. doi:10.1093/socpro/spw030

- Chew, H. E., Ilavarasan, V. P., & Levy, M. R. (2013). Mattering matters: Agency, empowerment, and mobile phone use by female microentrepreneurs. Information Technology for Development. doi:10.1080/02681102.2013.839437

- Donner, J. (2008). Research approaches to mobile use in the developing world: A review of the literature. The Information Society, 24(3), 140–159. doi: 10.1080/01972240802019970

- Donner, J., & Escobari, M. X. (2010). A review of evidence on mobile use by micro and small enterprises in developing countries. Journal of International Development, 22(5), 641–658. doi: 10.1002/jid.1717

- Duncombe, R. (2011). Researching impact of mobile phones for development: concepts, methods and lessons for practice. Information Technology for Development, 17(4), 268–288. doi:10.1080/02681102.2011.561279

- Duncombe, R., & Heeks, R. (2002). Enterprise across the digital divide: Information systems and rural microenterprise in Botswana. Journal of International Development, 14(1), 61–74. doi: 10.1002/jid.869

- Economist. (2011, July 18). Neoliberalism everything falls apart. The Economist. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2011/07/neoliberalism

- Economist. (2016, October 1). An open and shut case [Special Report]. The World Economy.

- Edwards, B., & Foley, M. W. (1997). Social capital and the political economy of our discontent. American Behavioral Scientist, 40(5), 669–678. doi: 10.1177/0002764297040005012

- Escobar, A. (2011). Encountering development: The making and unmaking of the third world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Fenelon, J. V., & Hall, T. D. (2008). Revitalization and indigenous resistance to globalization and neoliberalism. American Behavioral Scientist, 51(12), 1867–1901. doi:10.1177/0002764208318938

- George, S. (2007, June). Down the great financial drain: How debt and the Washington consensus destroy development and create poverty. Development, 50(2), 4–11. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.development.1100356

- Gibson, T., and Van der Vaart, H. J. (2008, September). Defining SMEs: A less imperfect way of defining small and medium enterprises in developing countries. Brookings Global Economy and Development. Brooking Global Economy and Development Institution Working papers Series.

- Hartocollis, A., Alcindor, Y., & Chokshi, N. (2017). “ ‘We’re not going away’: Huge crowds for women’s marches against trump.” New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/21/us/womens-march.html?_r = 0

- Ioffe, J. (2017, January 21). “ When protest fails.” The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/01/womens-march-protest-trump-russia/514064/

- Jacobs, J. (2010). Dark age ahead. Toronto: Vintage Canada.

- Kamel, S. (2013). Egypt's ongoing uprising and the role of social media: Is there development? Information Technology For Development, 20(1), 2013. doi:10.1080/02681102.2013.840948

- Kamal, M., & Qureshi, S. (2009). An approach to IT adoption in micro-enterprises: Insights into development. MWAIS fourth annual conference, Madison, South Dakota. Kamal, M.

- Kaplan, R. D. (1994). The coming anarchy. Globalization and the Challenges of a New Century: A Reader (pp. 34–60). (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000).

- Kentor, J. (2001, November). The long term effects of globalization on income inequality, population growth, and economic development. Social Problems, 48(4), 435–455. doi:10.1525/sp.2001.48.4.435

- Kotz, D. M. (2000). Globalization and neoliberalism. Rethinking Marxism, 12(2), 64–79.

- Leong, C. M. L., Pan, S. L., Newell, S., & Cui, L. (2016). The emergence of self-organizing E-Commerce ecosystems in remote villages of China: A tale of digital empowerment for rural development. Mis Quarterly, 40(2), 475–484.

- Lin, C. I., Kuo, F. Y., & Myers, M. D. (2015). Extending ICT4D studies: The value of critical research. Mis Quarterly, 39(3), 697–712.

- Lyons, T. S., Townsend, J., Sullivan, A. M., & Drago, T. (2010). Social enterprise's expanding position in the nonprofit landscape. New York, NY: National Executive Service Corps.

- May, J., Dutton, V., & Munyakazi, L. (2014). Information and communication technologies as a pathway from poverty: evidence from East Africa. In E. O. Adera, T. M. Waema, & J. May (Eds.), ICT pathways to poverty reduction: Empirical evidence from East and Southern Africa (p. 33–52). Rugby: Practical Action. doi:10.3362/9781780448152

- McLennan, S. J. (2016). Techno-optimism or information imperialism: Paradoxes in online networking, social media and development. Information Technology For Development, 22(3), 380–399. doi:10.1080/02681102.2015.1044490

- Midgley, J. (2003). Social development: The intellectual heritage. Journal of International Development, 15(7), 831–844. doi: 10.1002/jid.1038

- Mullany, G. (2017, January 16). World’s 8 Richest have as much wealth as bottom half, oxfam says. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/16/world/eight-richest-wealth-oxfam.html

- Nafziger, E. W., & Auvinen, J. (2002). Economic development, inequality, war, and state violence. World development, 30(2), 153–163. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00108-5

- Nemer, D. (2016) Online Favela: The use of social media by the marginalized in Brazil. Information Technology For Development, 22(3), 364–379. doi:10.1080/02681102.2015.1011598

- Nicholson, B., Nugroho, Y. & Rangaswamy, N. (2016). Social media for development: Outlining debates, theory and praxis. Information Technology For Development, 22(3), 357–363. doi:10.1080/02681102.2016.1192906

- Njihia, J. M., & Merali, Y. (2013). The broader context for ICT4D projects: A morphogenetic analysis. Mis Quarterly, 37(3), 881–905.

- Przybyla, H. M., & Schouten, F. (2017, January 21). USA TODAY Published 5:04 a.m. ET. Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/01/21/womens-march-aims-start-movement-trump-inauguration/96864158/

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of democracy, 6(1), 65–78. doi: 10.1353/jod.1995.0002

- Qureshi, S. (2013). In the age of popular uprisings, what is the role of public access computing and social media on development? Information Technology for Development, 19(4), 267–270. doi:10.1080/02681102.2013.840947

- Qureshi, S., & Kamal, M. (2011). Role of cloud computing interventions for micro-enterprise growth: Implications for global development. Proceedings of the Fourth Annual SIG GlobDev Workshop, Shanghai, China.

- Qureshi, S., Kamal, M., & Wolcott, P. (2010). Information technology interventions for growth and competitiveness in micro-enterprises. In P. Bharati, I. Lee, & A. Chaudhury (Eds.), Global perspectives on small and medium enterprises and strategic information systems: International approaches (pp. 306–329). Hershey, PA: IGI Global. doi:10.4018/978-1-61520-627-8.ch015.

- Qureshi, S., Kamal, M., & Wolcott, P. (2009). Information technology therapy for competitiveness in micro-enterprises. International Journal of E-Business Research, 5(1), 117–140. doi: 10.4018/jebr.2009010106

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1932). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. New Brunswick: Transaction.

- Sen, A. (2001). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 384.

- Song, C., & Qureshi, S. (2010). The Role of an Effective IT Intervention for Micro-enterprises in the 16th Americas Conference on Information Systems Proceedings, Lima, Peru, August 2010.

- Srivardhini, J. K., Pinsonneault, A., & Dube, L. (2016). The evolution of an ICT platform-enabled ecosystem for poverty alleviation: The case of eKutir. MIS Quarterly, 40(2), 431–445.

- Steinberg, J. (2003). Information technology and development beyond either/or. The Brookings Review, 21(2), 45–48. doi: 10.2307/20081104

- Street, C. T., & Meister, D. B. (2004). Small business growth and internal transparency: The role of information systems. MIS Quarterly, 28(3), 473–506.

- Thompson, M., & Walsham, G. (2010). ICT research in Africa: Need for a strategic developmental focus. Information Technology for Development, 16(2), 112–127. doi: 10.1080/02681101003737390

- Williams, J. C. (2017). What so many people don’t get about the U.S. working class. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2016/11/what-so-many-people-dont-get-about-the-u-s-working-class

- Zamudio-Suaréz, F. (2017, January 24). In discarded women’s march signs, professors saw a chance to save history. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.com/article/In-Discarded-Women-s-March/238987

- World Bank. (2015). Data catalog. Retrieved from http://datacatalog.worldbank.org/