Introduction

Healthcare as we know it is increasingly unaffordable and incapable of dealing with emerging population dynamics in virtually every country in the world. The global reform agenda of Universal Health Coverage seeks to address this challenge by urging countries to provide “financial risk protection to all in accessing quality and cost-effective health care services.” Improvements in care have resulted in life expectancy increasing dramatically and consequently resulting in higher demands for healthcare services accompanied by a dearth of medical professionals in parts of the world with the highest need. Rapid increases in chronic diseases, e.g. type-2 diabetes and hypertension, further exacerbate the impending crisis. The need for new healthcare thinking is paramount. However, the healthcare ecosystem has a multitude of stakeholders with many (and varied) interests. No single stakeholder, organization or government can unilaterally solve the complex nature of the problem at hand.

With the explosive growth of information technology (IT), emerging infrastructures and devices, the provision of healthcare is increasingly taking place supported through the use of these technologies. Healthcare services can now potentially be provided to anyone, anywhere and anytime through these innovations. These services and technologies provide patients, doctors and healthcare organizations immediate access to healthcare information for efficient decision-making as well as better treatment. Since health is development, societal impact is enabled through effective implementation of new innovations aimed at improving healthcare delivery. Unfortunately, little exists in the literature to illustrate how all of this might occur.

By nature, healthcare services require behavioral change of both the providers and consumers of care services, and this cannot be mandated. No single stakeholder, organization or government can unilaterally and directly change an individual’s behavior. Motivation can be both intrinsic and extrinsic (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, Citation1992; Deci & Ryan, Citation1980) and have multiple paths and influences, e.g. as explicated in the Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). Complications can easily occur as a result of behavioral complexity manifested by the many influences (and tensions) among healthcare stakeholders (Satish, Citation1997). To make matters worse, sustained behavior change is required for long-term benefit and positive impact of healthcare systems and services with societal value in mind (Goh, Gao, & Agarwal, Citation2016).

This special issue aims to report research on recent advances in various aspects of healthcare IT for Development with specific attention to research and experience from low- and middle-income countries. We focus on covering innovative approaches to achieving health IT and Development impact where the concept of Development can be assessed through improvements in healthcare outcomes, provision and services.

Framework and motivation

To frame the papers in our special issue, we start with a view of the healthcare ecosystem, with a sensitivity to sustained behavioral change and service creation and implementation considerations.

Healthcare ecosystem

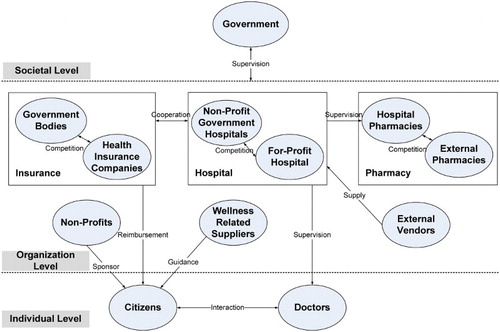

The healthcare ecosystem illustrated in embraces multiple levels of consideration and relationships between key stakeholders.

The interactions among the multiple stakeholders are varied and complex. For instance, when a citizen goes for a medical suggestion from a doctor, it is not simply one patient and one doctor, but may also relate to the citizen’s friends and families, other doctors (group consultation), hospital suppliers, pharmacies and insurance. Furthermore, the citizen may also search on the Internet and talk with other citizens and doctors in online healthcare communities. As such, individual-level interactions can quickly involve organizational-level considerations.

Moreover, the relationships between government (at a societal level) and hospitals can be multi-dimensional and multi-directional in that governments can affect hospitals directly and indirectly through funding, regulatory requirements, reporting requirements, opening the healthcare market to global competition, etc. A change, say government opening up the healthcare market to competition, may lead to rippling behavioral changes in citizens, doctors, hospitals, insurance companies, etc. that will eventually affect the entire ecosystem. Similarly, hospitals’ use of health information systems may allow doctors to develop in-depth insights into patients or efficacy of drugs for different target patient groups through large-scale data analytics, which may then lead to procedural changes or adjusted decision-making at hospitals and insurance companies.

In addition to the non-linearity and the unpredictability of effects that arise due to the interactions, the complexity in the healthcare ecosystem () is further exacerbated by the mix of different agents, different skill sets and contextual situations with different resources, constraints, motivations and incentives (or disincentives). Knowledge sharing among the broader group of stakeholders has historically been very limited. The dynamic coevolution of one stakeholder (e.g. citizens becoming more health literate over time) may alter the nature and complexity of interactions among the stakeholders (e.g. shifting the entire ecosystem patterns of behavior from one of the disease management to disease prevention). Hence, it is not viable to examine healthcare challenges from the perspective of a sole stakeholder or a single dyadic relationship.

Sustained behavioral change

Sustained behavior change is an umbrella under which numerous studies can be conducted, especially given the availability of a platform, e.g. a service focused on healthcare. Sustained use of technology in healthcare requires behavioral change that cannot be mandated, with no single stakeholder, organization or government able to change an individual’s behavior. Behavioral change under these circumstances requires persuasion, incentives and coercion of one form or another (Ajzen & Timko, Citation1986). The general literature on persuasion is lengthy going back to the Greeks and can have multiple paths of influence. Systematic persuasion is the process through which attitudes or beliefs are leveraged by appeals to logic and reason whereby heuristic persuasion, on the other hand, is the process through which attitudes or beliefs are leveraged by appeals to habit or emotion (Schacter, Gilbert, & Wegner, Citation2011).

Sustained behavior change goes beyond persuasion to gauge lasting impact. Motivation can be both intrinsic and extrinsic (Davis et al., Citation1992; Deci & Ryan, Citation1980). Complications can easily occur as a result of behavioral complexity manifested by the many influences (and tensions) among healthcare stakeholders (Satish, Citation1997) illustrated in . To make matters worse, sustained behavior change is required for long-term benefit and positive impact of healthcare systems and services with societal value in mind (Goh et al., Citation2016). Cultural heritage is an additional consideration in the context of sustained behavioral change.

The elaboration likelihood model (ELM) examines routes to persuasion, i.e. central or peripheral, as well as the moderating influence of motivation and ability of the target individual (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). This is a potent combination that enables examination of the position of the persuader as well as the response to the message of the target individual(s) being influenced regarding the use of technology in healthcare. Central route induced changes are generally considered more stable (and, thus, more predictive of sustained behavioral change) since they demand more deliberate and reasoned consideration (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). The ELM has been previously used in related research (e.g. Angst & Agarwal, Citation2009; Bhattacherjee & Sanford, Citation2006).

Aspects of cultural tightness in terms of sense of identity are important in consideration of healthcare service impact and sustained behavioral change (Gelfand, Nishii, & Raver, Citation2006, Citation2011). As such, consideration at individual levels cannot be entirely divorced from influences by others engaged in service utilization. Social media and general sense (and need) of belonging may be influential in service use and adoption including consideration of wearable device impact and other IT innovations. Cultural tightness is both an antecedent and a potential outcome associated with service adoption. Population segments prone to cultural tightness may be more inclined to try services and, after experience with technologies that share information with friends, may be more inclined to sustain use.

Service creation and implementation

Recognizing the importance of systems is necessary, but not sufficient, for sustained healthcare behavioral change. Another level of attention in the form of services engaging healthcare professionals (and other stakeholders) is paramount. By nature, services exist to assist citizens in achieving a desired state of health through a combination of data, processes and technology. People can be unpredictable and processes need to be contextually independent. Unforeseen consequences and unintended behaviors can easily occur. There are lots of “unknown unknowns” and chaotic dynamics. Furthermore, to be sustainable, services need to provide feasible and desirable value for multiple stakeholders with effectiveness efficiency in mind. As such, services go substantially beyond systems in terms of complexity and relevant considerations.

The vast majority of existing literature is systems (rather than service) focused. Systems are more easily defined and, when in organizational contexts, can be mandated in terms of use. Services, on the other hand, are people centric and often exist in environments where use cannot be mandated, e.g. healthcare. As such, service creation and implementation requirements are considerably more difficult to generate and implementation must be more flexible in adapting to changing conditions and emerging “red flags” that might curtail effective utilization. By nature, then, service development is iterative with conscious efforts focused on continuous evaluation and environmental scanning to assure a decent probability of service success in sustaining behavior change.

Sustainability criteria for services are based on successful implementation in term of being used and useful for those intended. To become truly embedded requires passing “the toothbrush test” in that users much routinely use the services in some form as part of daily habit. This may be as simple as routinely checking the number of steps taken as recorded on a wearable device or more sophisticated as a function of IT accessibility and use. Ultimately, however, services need to be economically viable in terms of value added and robust in terms of stakeholder rewards. Ability to evolve to meet changing needs is an additional sustainability criterion as is scalability within defined contexts to assure more widespread use and recognition with a portfolio of value propositions.

Healthcare professionals are a key stakeholder in sustained behavior change motivation, in part, through technology use in conjunction with service creation and implementation. Without healthcare professional involvement, any data from technology should only be seen as part of the ultimate information leading to holistic behavioral change advice. Service creation needs to take into consideration needs and expectations of healthcare professionals (which might ultimately involve nutritionists and exercise coaches as well as doctors) to appropriately include (and reward) their expertise. Properly implemented, services become agents for sustained behavioral change and repository of accumulated information over time that can lead to the advancement of knowledge.

Author contributions

The papers in this special issue look at a variety of relevant issues found in various segments of the healthcare ecosystem illustrated in starting at individual levels advancing to organizational levels and culminating in societal level impact.

In “The role of perceived e-health literacy in users’ continuance intention to use mobile healthcare applications: an exploratory empirical study in China,” Xi Zhang, Xiangda Yan, Xiongfei Cao, Yongqiang Sun, Hui Chen and Jinghuai recognize that in recent years, mobile healthcare applications (MHAs) have boomed, providing several new kinds of health services and methods of information transmission. However, MHA vendors face a significant challenge in attracting users to adopt software continuously. Some recent studies have recognized users’ perceived ehealth literacy (PEHL) as a critical factor in sustaining use, but its influence is still unclear. In this paper, based on the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), the authors investigated how the users’ PEHL affects their continuance intention when adopting MHAs. They distributed convenience sample questionnaires via Wechat (similar to WhatsApp) in China, where hundreds of MHAs can be downloaded, and 273 valid samples were collected. The results show that ELM works well in this model, with six of the eight hypotheses supported. The moderating effect of PEHL is largely significant for the peripheral route but not significant for the central route. The most interesting finding is that, with regard to continuance adoption, PEHL has a positive relationship with users’ satisfaction. Possible reasons are discussed, e.g. there could be a moderator on this relationship. Limitations, future studies and implications for theory, practice and policy are also given.

In “An assessment of learning gains from educational animated videos versus traditional extension presentations among farmers in Benin,” Julia Bello-Bravo, Manuele Tamò, Elie Ayitondji Dannon and Barry Robert Pittendrigh compare the efficacy of linguistically and dialectically localized animated educational videos (LAV) against traditional learning extension presentations for learning gains around agricultural- and healthcare-related topics within a rural population in Benin. While both approaches demonstrated learning gains, LAV resulted in significantly higher test scores and more detailed knowledge retention. A key contribution of this research, moreover, involves the use of mobile phone technologies to further disseminate educational information. That is, a majority of participants expressed both a preference for the LAV teaching approach and a heightened interest in digitally sharing the information from the educational animations with others. Because the animations are, by design, readily accessible to mobile phones via Africa’s explosively expanding digital infrastructure, this heightened interest in sharing the animated videos also transforms each study participant into a potential learning node and point of dissemination for the educational video’s material as well.

In “mHealth outcomes for pregnant mothers in Malawi: A capability perspective,” Mphatso Nyemba-Mudenda and Wallace Chigona note that reducing maternal mortality rate (MMR) by 75% by the year 2015 was the primary target for Millennium Development Goal 5. However, between 1990 and 2015, the MMR only fell by 50%. Sustainable Development Goal 3 aims to reduce the global MMR to 0.1% by the year 2030. Mobile technology for healthcare service delivery (mHealth) is being implemented in many developing countries to address challenges faced in maternal health in trying to achieve this goal. Existing literature on mHealth tends to focus mainly on design and implementation of mHealth projects but a few studies have evaluated mHealth interventions to assess health outcomes. Their study evaluates the effectiveness of mHealth based on consumers’ capabilities, and their contribution towards social change and human development using the capability approach theoretical framework. The findings show that the use of mobile phones to access health information and healthcare services can generate a number of opportunities for women in maternal health, not only for health purposes but also for their informational, economic and psychological well-being. However, the generation of the opportunities and realization of the outcomes is mediated by a myriad of personal, social and environmental factors that are either enabling or restrictive.

In “Doctor–patient relationship strength’s impact in an online healthcare community,” Shanshan Guo, Xitong Guo, Xiaofei Zhang and Doug Vogel note that doctor–patient (D–P) interaction currently faces a set of challenges owing to a dearth in medical resources and related communication reasons. Healthcare information technology and associated systems, such as those supporting online healthcare communities (OHCs) that provide new platforms for information exchange and online communication, are expected to alter traditional D–P relationship models. Despite significant results from extant research indicating patient benefits, empirical research on OHC returns for physicians is lacking. This exploratory study examines the strength of the D–P relationship and its impacts on physicians’ individual outcomes in an OHC. Guided by social capital and social ties theories, and using a structural equation modeling approach to study 339,010 instances of D–P communication from 1430 physicians at The Good Doctor (www.Haodf.com) which is one of the largest Chinese OHCs, the authors found that weak ties can result in economic and social returns for doctors. However, further analysis has indicated that strong ties mediate the effect of weak ties, thus encouraging doctors to convert weak ties into strong ties by mobilizing their website settings to strengthen their relationships and, subsequently, to be better rewarded. Implications for research and practice on the development of healthcare information technology and associated services are discussed.

In “Proposing a decision support system for automated mobile asthma monitoring in remote areas,” Chinazunwa Uwaoma and Gunjan Mansingh note that advances in mobile computing have paved the way for the development of several health applications using Smartphones as a platform for data acquisition, analysis and presentation. Areas where m-health systems have been extensively deployed include monitoring of long-term health conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and pulmonary disorders, as well as detection of changes from baseline measurements of such conditions. Asthma is one of the respiratory conditions with growing concern across the globe due to the economic, social and emotional burden associated with the ailment. The management and control of asthma can be improved by consistent monitoring of the condition in real-time since attacks could occur anytime and anywhere. This paper proposes the use of smartphone equipped with built-in sensors, to capture and analyze early symptoms of asthma triggered by exercise. The system design is based on decision support system techniques for measuring and analyzing the level and type of patient’s physical activity as well as weather conditions that predispose asthma attack. Preliminary results show that smartphones can be used to monitor and detect asthma symptoms without other networked devices. This would enhance the usability of the health system while ensuring user’s data privacy and reducing the overall cost of system deployment. Furthermore, the proposed system can serve as a handy tool for a quick medical response for asthmatics in low-income countries where there is limited access to specialized medical devices and shortages of health professionals. Development of such monitoring systems signals a positive response to lessen the global burden of asthma.

In “Mind the Gap: Assessing Alignment between Hospital Quality and its Information Systems,”João Barata, Paulo Rupino da Cunha and Ana Paula Melo Santos present a method to assess how aligned hospital information systems (HIS) are with quality standards adopted by the organization. Canonical action research is their mode of inquiry, in a district hospital implementing multiple certification standards. The authors build on the “ground-truth” provided by healthcare professionals to identify risks and opportunities for HIS developments while contributing to their awareness of its implications. They address different categories of design-reality gaps, namely the organizational, service, process and individual. The findings suggest that HIS compliance should address five interrelated dimensions of context, people, processes, IT and information/data. The proposed method allows self-evaluation through gap analysis and a comprehensive assessment of hospital quality, integrating HIS and healthcare processes. Moreover, it supports multiple quality models in hospitals and the development of heterogeneous HIS solutions in different maturity stages. HIS developments should be a priority for hospital quality worldwide; especially in the emerging economies that require methods accessible to their resources, standards compliance and demographic demands for healthcare.

In “Countering the ‘dam effect’: the case for architecture and governance in developing country health information systems,” Mikael Gebre-Mariam and Elisabeth Fruijtier present a case for enterprise architecture (EA) and IT governance for driving techno-organizational change and coordination of health information systems (HISs) in developing countries. They support their claim with analyses of a large-scale electronic HIS in Ethiopia by tracing the logic of actors’ decisions and conduct within and beyond the organizational boundaries of the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health to understand how the information system innovation process is designed, legitimized and imposed by internal and external organizational forces. In the absence of formalized institutional arrangements throughout the HIS development and implementation, an international development agency fills a key gap forming an obligatory passage point which the authors conceptualize as “the dam effect.” Drawing on actor–network theory, they identify three important implications of EA and IT governance: (1) to help achieve an alignment of interests within the enterprise; (2) to serve as a tool for protecting the interests of the enterprise in external negotiations and (3) to serve as a pragmatic approach to carrying out techno-organizational change.

In “Mobile IT in Health – The Case of short messaging service in an HIV Awareness Program”, Tridib Bandyopadhyay, Peter Meso and Solomon Negash aim to augment our understanding of user intention to use mobile IT in health. Experiential dispositions and technology perceptions around a mobile service that is currently in use to access other value-seeking services are integrated to present an enriched characterization of intention to use m-health. Primary data from a pressing health context in a developing economy is collected to validate the model. The results demonstrate that previous experience from value services received on a mobile service enhances user attention, which in turn positively impacts the perceived usefulness of an incoming m-health program, which then influences user intention to adopt m-health services delivered on that mobile service. Overall, the findings provide a comprehensive understanding of user intention to accept m-health. Additionally, their results provide insights towards the choice of mobile technology and indicate aspects of message framing that may ensure practicable deployment and successful implementation of m-health programs.

In “Innovation in the Fringes of Software Ecosystems: The role of Socio-Technical Generativity,” Brown Msiska and Petter Nielsen note that understanding the way information systems grow and change over time and the role of different contributors in these processes is central to current research on software development and innovation. In relation to this, there is an ongoing discourse on how the attributes of software platforms influence who can innovate on top of them and the kind of innovations possible within the larger ecosystem of technologies and people these platforms are part of. This discourse has paid limited attention to innovation unfolding in the fringes of the ecosystem peripheral to and disconnected from where the central software components are developed and where the resources necessary for digital innovation are scarce. Drawing upon Zittrain’s characteristics of generativity and Lane’s concept of generative relationships, the key contribution of this paper is a socio-technical perspective on innovation and generativity in this setting. They build this perspective of socio-technical generativity based on a case study of software innovation activities in Malawi on top of the health information system software platform DHIS2 developed in Norway. This case illustrates how the technical attributes of the platform played a key role in concert with human relationships in shaping innovation activities in Malawi.

Conclusion

In a world of ever-more powerful (and more globally available) technology, a wide variety of services become possible with ever-expanding value propositions. As McAfee and Brynjolfsson (Citation2017) have noted, “rather than being locked into any one future, we have a greater ability to shape the future.” The question of how to choose what technology for what kind of service, with recognized cultural connotations, is something we can conclude from informed choice based on sound research in global contexts. We hope you enjoy this collection of papers and look forward to future contributions in the spirit of continued scholarship.

Acknowledgment

The editor would like to thank the many reviewers for their contributions in helping the authors fine-tune their contribution.

References

- Ajzen, I., & Timko, C. (1986). Correspondence between health attitudes and behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 7(4), 259–276. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp0704_2

- Angst, C., & Agarwal, R. (2009). Adoption of electronic health records in the presence of privacy concerns: The elaboration likelihood model and individual persuasion. MIS Quarterly, 33(2), 339–370. doi: 10.2307/20650295

- Bhattacherjee, A., & Sanford, C. (2006). Influence processes for information technology acceptance: An elaboration likelihood model. MIS Quarterly, 30(4), 805–825. doi: 10.2307/25148755

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1992). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(14), 1111–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00945.x

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1980). The empirical exploration of intrinsic motivational processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 13(2), 39–80. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60130-6

- Gelfand, M. J., Nishii, L. H., & Raver, J. L. (2006). On the nature and importance of cultural tightness-looseness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1225–1244. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1225

- Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., … Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332(6033), 1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1197754

- Goh, J. M., Gao, G., & Agarwal, R. (2016). The creation of social value: Can an Online Health Community reduce rural-urban health disparities? MIS Quarterly, 40(1), 247–263. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.1.11

- McAfee, A., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2017). Machine, platform, crowd: Harnessing our digital future. New York, NY: Norton and Company.

- Petty, R., & Cacioppo, J. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Satish, U. (1997). Behavioral complexity: A review. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27(23), 2047–2067. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01640.x

- Schacter, D., Gilbert, D., & Wegner, D. (2011). The accuracy motive: Right is better than wrong-persuasion. In Psychology (2nd ed, pp. 105–119). New York, NY: Worth, Incorporated.