ABSTRACT

Amidst a global pandemic, outrage and anger over the death of a Black man at the hands of a White police officer spread globally. The protests exposed generations of institutional racism and socio-economic inequities in many countries. This editorial explores the socio-economic inequities that have left those in racially segregated marginalized communities most at risk from COVID 19. It offers a cyclical view of the relationship between socio-economic inequities and health outcomes, suggesting that once these inequities are addressed, then health outcomes can improve. There is an important role to be played by ICTs in enabling a positive cycle to take place. The papers in this issue reflect the ways in which the socio-economic indicators can be increased to support better health outcomes for people in low SES communities. They uncover the key issues facing communities offering healthcare service to their constituents and move the field forward by showing the ways in which ICTs may support a positive cycle of development and health outcomes.

Introduction

While the world is grappling with the devastating effects of a pandemic, outrage and anger spread. On 25 May 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man suspected of passing a counterfeit $20 bill, died in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Derek Chauvin, a white police officer, is seen in a video pressing his knee on Floyd's neck for almost nine minutes while Floyd was handcuffed face down in the street. In another video, three other police officers are seen pressing their knees on his body at various times assisting Chauvin. Initially, Chauvin was suspended, and then after fury broke out on the streets of Minneapolis, Chauvin was charged with third-degree manslaughter. Protesters, outraged at the manner in which alleged homicides by police officers are handled, continued in anger. The police precinct was burned down and a militarized police force took over to combat protests against police brutality with more police brutality. After the first had exonerated the police officer, a second medical examiner said that Floyd’s death was a homicide, because his heart stopped beating while police restrained Floyd and compressed his neck. Chauvin’s charge was upgraded to second-degree murder and the three other officers charged as well. The protests continued across the United States, and in other parts of the world with people voicing their anger at the treatment of Black people at the hands of police. Countries such as Australia and South Africa, with apartheid in their past, still suffer from systemic racism in their police forces. Systemic racism that has grown out of the segregation of the past in countries formerly at the hands of their European colonialists. Protests continued in Europe, Latin America and Asia against the mistreatment of non-whites in their countries. The death of Floyd became a symbol of years, even generations, of racial injustice.

Large crowds of protesters spread across the United States to the rest of the world, with larger crowds expressing outrage over the mistreatment of Blacks and other marginalized populations. Outrage over generations of social and economic inequality that has left Blacks and Latinos unable to pull themselves out of deepening poverty and ill health. The series of protests across the country and the world demanded justice and an end to the racism that led to the death of Floyd and other Blacks at the hands of White police officers. The protests started as a peaceful declaration of anger and frustration, then became violent. Militarized police used tear gas and force to contain the protests. Journalists and protesters were arrested. Some cities instituted curfews to calm down the riots while others closed down certain areas. This resulted in some changes. Eighteen days after the death of George Floyd, the Minneapolis city council unanimously passed a resolution to replace the police department with a community-led public safety system. This vote began a year-long process in which the city council will engage with community members in Minneapolis to develop a new public safety model that includes staff from city departments such as, the offices of violence prevention and civil rights. They also voted unanimously to end the local emergency order that had been declared due to protests in the wake of Floyd’s death (Beer, Citation2020). There is a sense the moving funds from policing to addressing homelessness by offering safer housing, educational and training programs, and healthcare will make for a safer society. While there is a need to address crime, the majority of current police functions have little to do with law enforcement and crime, and are mostly responding to mental health calls and other social services (Levin, Citation2020).

Institutionalized racism and socio-economic disparities are not unique to the United States. As diminishing economic opportunity, education and healthcare have increased the pain and suffering caused by the pandemic, people all over the world have expressed their outrage to the racism faced in their own communities, as protests and politics play out in the United States. The World Economic Forum reports that racial wealth inequality was an important factor contributing to the riots in many American cities in the 1960s, but a half-century later, the issue remains. Black adults, especially Black men, are far more likely to end up in jail than White adults. In 2018, there were 1501 Black prisoners for every 100,000 Black adults - more than five times the rate among Whites. About three in every five Black men say they have been unfairly stopped by the police because of their race. Also, about eight in every ten Black people, with at least some college education, say they have been discriminated against because of their race. The home ownership gap between Blacks and Whites has widened since 2004 and Black families are less likely than White families to own a home. Today, 41% of Black households own their own homes, compared with nearly 72% for Whites. Black households have only 10 cents in wealth for every dollar held by White households, according to 2016 data. In 2016, the median wealth of non-Hispanic White households was $171,000 – 10 times the wealth of Black households ($17,100) (Desilver et al., Citation2020; Gramlich, Citation2019; Reuters, Citation2020).

In order to survive the pandemic, governments have issued quarantine, stay at home orders, and travel restrictions. People globally are gathering in large protests to express anger despite the risk of infection, people globally are expressing anger and outrage at the killing of Blacks at the hands of an increasingly militarized police force. The COVID-19 pandemic is an increasing incidence of racism around the world. Qasim (Citation2020) reports that the crisis feeds fear which is manifesting itself in xenophobia and discrimination. In the UK people are asking not to be treated by doctors and nurses of Asian ethnicity. Many Black people have faced serious discrimination and racism in Chinese cities. Reports from Guangzhou are saying that immigrants and expats of Black ethnicity have been driven out of their houses and forced to self-quarantine. In India, which has a caste system that institutionalizes racism against darker-skinned people, saw a mass exodus of workers unable to find shelter in the cities migrating to the villages. Hate speech erupted against Muslims, with increased Islamophobia connected to the spread of the virus. As these countries re-open their economies, these disparities add to the risk of a second wave of new infections from mutated strains of the coronavirus.

In the US, which is currently reporting the largest number of cases, the coronavirus has disproportionately affected Black men and women measured by deaths from the disease and unemployment rates during the pandemic. By the end of May, the COVID-19 mortality rate for Black Americans (1 in 1850) was 2.4 times as high as the rate for white Americans (1 in 4400). In April, the Black unemployment rate was nearly 17%, compared with a white unemployment rate of 14%. The disparities continue to limit the ability of people who have been marginalized to stay healthy or recover from the virus. Most African Americans, Native Americans, and Latinos cannot afford to stay at home and lose their jobs nonetheless, and thus their ability to survive is diminished. Much of the world has been on a stay-at-home lockdown with most businesses deemed non-essential closed. When African American businesses close, their owners and employees sometimes fall into poverty.

Over the past two decades, the wage gap between Black and White workers has grown significantly in the United States. In 2018, the median weekly earnings for full-time workers were $694 for Black Americans, compared with $916 for white Americans. In 2017, Black women earned less than white women, with the median annual earnings for full-time Black women workers at just over $36,000 – 21% lower than that of white women. Black women in the United States are more than three times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. Black students are less likely to graduate from high school than White students. In 2018, 79% of Black students graduated from high school in comparison with 89% among white students (CDC, Citation2020, Department of Labor, Citation2020; Reuters, Citation2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic

At the heart of these societal changes is a coronavirus called COVID-19 which is short for Corona (CO) Virus (VI) Disease (D) from the year 2019 when it first erupted in Wuhan, China. At the time of writing this editorial, there are 9 billion cases confirmed with 470,665 deaths globally from COVID 19. The countries reporting the highest number of deaths are: the US is at 2,275,645 cases and 119,923 deaths, United Kingdom 42,731, deaths, Brazil 51,228, Italy 34,657, France 29,666, Spain 28,324, Mexico 21,825 and India 13,699 deaths (Centers for Disease Control, Citation2020; Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Information Center, Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2020).

Less than three months before the earliest reported case of humans infected with COVID-19, Nuzzo et al. (Citation2019) published a WHO/World Bank-commissioned report about a high-impact respiratory pathogen that would have significant public health, economic, social, and political consequences. The report found that the potential for an epidemic or pandemic caused by a high impact respiratory pathogen is increasing due to spillovers from animals into humans living in close contact with animals. Changing patterns of animal management and land use, international travel, mass displacement, migration and urbanization, pathogens are able to spread in new, susceptible populations. The report explains that these novel high impact respiratory pathogens are very unique in that they attack many people in different countries all at once. The report explains why:

“Respiratory pathogens can be particularly difficult to contain. Their tendency to have short incubation periods and their potential for asymptomatic spread can mean very small windows are available for interrupting transmission. Individuals infected with respiratory viruses may infect many more people at a time as compared to pathogens spread by other means. These factors increase both the pandemic potential of respiratory pathogens and the likelihood that there will be serious public health, economic, and social impacts with their spread.” (Nuzzo et al., Citation2019, p. 18)

The report predicted that widespread transmission of a high-impact respiratory pathogen would cause a surge of patients seeking care that would challenge the most well-prepared health care systems. While contact tracing has been effective in containing epidemics in that past, Nuzzo et al. (Citation2019) found that this would not be feasible for a high-impact pathogen because it is very difficult to identify contacts when all who may have been in the general vicinity of a case may be at risk. Their prediction turned out to be very real. In hospitals, first responders and medical professionals struggle to offer care with limited resources. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is hard to find as doctors, nurses and first responders put their own lives at risk trying to save lives. Lives are increasingly difficult to save as the virus mutates offering newer and more aggressive symptoms.

The COVID-19 virus spreads primarily through droplets of saliva or discharge from the nose when an infected person coughs or sneezes. The symptoms start with a dry cough, a spike in fever, with some aches and pains, nasal congestion, runny nose and sore throat. Then diarrhea and in some cases blindness follows. At subsequent stages, the lungs get attacked causing fluid to build up. Putting patents on respirators can save some but aggravates the breathing issues in others. Causes of death from COVID-19 include blood clots leading to a stroke and heart failure as well as brain damage. As this high impact pathogen continues to evolve, new symptoms emerge such as swelling and inflammation in different parts of the body leading to death (CDC, Citation2020; Nuzzo et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2020).

To fight the spread of this pandemic, countries have been closing their borders, restricting travel, instituting quarantine and social distancing. While these measures appear to have limited the rates of increase in the pandemic, it is the socially disadvantaged who have borne the brunt of its devastation. They are the first to lose their jobs, or see their businesses flounder. Centuries of segregation and discrimination in countries such as the US have disproportionately placed people of color in communities without access to health care, with degraded and crowded living conditions and a lack of basic opportunities for health and wellness. For example, the health status of North Omaha residents is very low due to a lack of viable housing, food supply and healthcare which is partly the result of redlined districting. This segregation has affected generations of residents by keeping them in poverty and unable to access basic resources needed to thrive. Poverty in the U.S. is very much tied to race and ethnicity. In 2018, 11% of Whites had a household income below the federal poverty level compared to 23% of Blacks and 19% of Hispanics. People of color are also more likely to live in low-income communities with a lack of access to basic resources for health and wellness. Low-income neighborhoods with reduced access to healthy food and fewer opportunities for physical activity have higher rates of high blood pressure, obesity and diabetes. Such chronic conditions often result in compromised immunity, making individuals more vulnerable to infectious diseases (Noppert, Citation2020; Science News, Citation2020).

This virus continues to hurt those in the poorest communities. Noppert (Citation2020) finds that the death rate from COVID-19 appears to be staggeringly high among Blacks compared to Whites. The Washington Post reports, for example, that while only 14% of the Michigan population is Black, 40% of COVID-19 deaths are among Blacks. In Omaha, Nebraska, Hispanics and Asian Americans are hit hardest by coronavirus. Even though only 11% of the state’s population is Latino, they account for half of the coronavirus cases for which ethnic information was collected, as well as 40% of the hospitalizations and one in every five deaths. Latinos and Asian Americans represent a large proportion of the workforce in meatpacking plants, which have been major sources of coronavirus outbreaks in Nebraska. Meatpacking workers accounted for 2988 of the state’s 13,261 cases (Stoddard, Citation2020). In New York City, one of the hardest hit in the nation, the three counties with mostly Black populations rank the highest in the number of deaths in the US: Queens (5276 deaths), Kings (5328 deaths) and the Bronx (3714). Hispanics make up more than a third of deaths and Black people more than one fourth, notably above their representation in the general population (Johns Hopkins, Citation2020).

Socio-economic determinants of health

There is evidence to suggest that socio-economic status (SES) affects a variety of health outcomes (Adler et al., Citation1994 Duncan et al., Citation2002; Lantz & Pritchard, Citation2010;). Socio-economic status is linked to the ability to be and stay healthy. Socio-economic status is determined by one’s income, educational attainment, and occupation (Adler & Newman, Citation2002). It is accepted among sociological, epidemiological and even economic researchers that socioeconomic status is the most prominent predictor of health (Marmot, Citation2007, Citation2003; Pampel et al., Citation2010; Pamuk et al., Citation1998; Phelan, Citation2004; Singh-Manoux et al., Citation2003; Stansfeld et al., Citation1998). For example, trends in life expectancies are directly related to educational attainment and annual income rates (Marmot, Citation2007). The association between socio-economic affluence and health is also recognized and accepted as people with higher incomes can afford better healthcare. This widespread recognition, however, oversimplifies how strong the association between SES status and health truly is.

Nicholas Christakis, a medical sociologist from Yale University, and epidemiologist Sir Michael Marmot, use the imagery of a ladder to explain the association between socioeconomic status and health. Christakis explains that most people can quite readily appreciate the fact that if they have more money they will be healthier. But it also turns out that that observation holds not just at the extremes. So, for example, let’s say that there’s a ladder. It’s not just that the rich differ in some way from the poor in some kind of Black-White or yes-no or zero-one kind of way. There’s a fine gradation all the way up this ladder, both in wealth and in health (Adelman, Citation2008).

Social determinants of health are understood to be the social, political, and economic factors that contribute to one’s state of health (Marmot, Citation2007; Castaneda, Citation2015). While the distribution of resources within a society that contributes to health varies along the social gradient, this unequal distribution does not necessarily indicate a health inequity (Sen, Citation2002, Marmot, Citation2007, Braveman and Guskin, Citation2003, Citation2011). Health equity, on the other hand, occurs when all persons along the social gradient share in the ‘equal opportunity to be healthy’ (Braveman and Guskin, Citation2003). The opportunity to be healthy, as a concept, does not concern itself with factors such as pre-existing conditions or personal exercise and dietary habits. It is the opportunity to attain the highest possible level of physical and mental wellbeing that an individual’s personal biological limitations will permit (Braveman and Guskin, Citation2003). As such, the person who has the opportunity to attain health improvements, but chooses not to either in their habits or in their failure to seek health services, is not a victim of health inequity. On the other hand, the person who is unable to develop healthy habits or seek medical services due to social, political, or economic conditions, and thus has not been afforded the opportunity to attain their highest possible level of physical and mental wellbeing, is a subject of health inequity.

Health inequality exists when there are substantially different health outcomes between two or more populations, i.e. female and male health expectancies. Health inequity, however, also occurs when the opportunity to live a prosperous and healthy life varies substantially between two or more populations, i.e. the prevalence of fair or poor health among poverty-stricken populations. As spokesperson for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Michael Marmot states:

“Not all inequalities are unjust or inequitable, [however], where inequalities in health are avoidable, yet are not avoided, they are inequitable,”. (2007, p. 1154)

Marmot goes on to explain how employment status affects health in that the lower the grade of employment, the higher the risk of heart disease and every major cause of death. So, if you were second from the top, you had worse health than if you were at the top. If you were third from the top, you had worse health than if you were second from the top all the way from top to bottom (Marmot, Citation2007).

Even though the association between SES status and health is rarely disputed, why the association is so strong continues to be uncertain. To tackle this mystery, Nancy Adler and Katherine Newman analyzed numerous studies that explored SES and health outcomes. Through this analysis, Adler and Newman discovered three major determinants of health associated with SES in the United States: healthcare, environmental exposures, and lifestyle and health behaviors (Adler & Newman, Citation2002). There is connection between socio-economic status, education and health. Lahelma et al. (Citation2004), found that gender is a potential moderator of the pathways between socio-economic determinants of health. Compared to men, inequalities by income among women could be better explained by their education and occupational class. Household income is likely to equalize health inequalities between men and women as compared with individual income. Household based socioeconomic indicators that may be more powerful determinants of health among women than men.

The demographic, geographic, and socioeconomic conditions that influence a population’s health outcomes have come to be known as the social determinants of health or ‘the causes [of health inequity]’. The role of social aspects, such as one’s race, rural/urban lifestyle, or level of educational attainment in determining the health outcomes of a given population, has left many with the idea that health inequity is solely a social justice issue. While the social justice aspect of health inequity is cause for concern on its own, health inequity also hinders socioeconomic development as ill and injured populations are limited in their ability to participates in the workforce. As such, neither one’s quality of life, nor their socioeconomic opportunity, can be separated from their health (Marmot, Citation2007).

Lantz and Pritchard (Citation2010) suggest that the degree of inequality in the income distribution of a geographic area is associated with mortality. They found several studies to have shown an association between the degree of racial segregation in a geographic area and mortality as well as other health outcomes. Many aspects of the neighborhood socioeconomic environment, including poverty and discrimination, can be considered stressors. Chronic exposure to social stressors can elevate the body’s stress response (via neural, euro endocrine, and immune systems) and produce ‘allostasis,’ a physiologic state that in the long run causes changes in the immune system and brain that can lead to disease through a variety of biological mechanisms. While discrimination is difficult to observe or measure, they suggest that it is typically measured as ‘perceived discrimination’ via self-reported survey data. Self-reports of perceived discrimination or unfair treatment because of race or ethnicity have also been associated with some negative health outcomes in studies by Krieger (Citation2000) and Karlsen and Nazroo (Citation2006). The discriminatory health mechanisms are both direct (denial of needed services/resources related to health) and indirect (increased psychosocial stress, increased health risk behavior as a coping mechanism).

The access to, use of, and quality of health care varies by socioeconomic status in the U.S. (Adler & Newman, Citation2002). There are fewer primary care doctors per capita in less affluent areas (Shi & Starfield, Citation2000, Blumenthal & Kagen, Citation2002 and residents of those areas are less likely to receive preventative screenings or specialty care (Dunlop et al., Citation2000, Blumenthal & Kagen, Citation2002,). Low SES populations are more likely to be uninsured (Monheit & Vistness, Citation2000) and are more likely to receive poorer quality of care when they do seek medical care (Hafner-Eaton, Citation1993). Furthermore, more health resources go towards the treatment of diseases with relatively few funds attempting to modify predisposing factors, such as environmental and behavioral risks; all of which disproportionately disadvantage less affluent areas (Adler & Newman, Citation2002).

Adler et al. (Citation1994) contend that individuals living in better socio-economic conditions enjoy better health than those living in lower socio-economic conditions. They reported on a model that illustrates a directly inverse correlation between morbidity rates and socio-economic status. Whereby, the lower the socio-economic status of individuals the higher the percentage of people who were diagnosed with osteoarthritis, chronic diseases, hypertension and cervical cancer. They found that education, income, and life expectancies are the key factors that lead to different socio-economic conditions (Adler et al., Citation1994). This suggests that the health of a population depends upon the level of its socio-economic development. Roztocki and Weistroffer (Citation2016) define socio-economic development to be ‘a process of change or improvements in social and economic conditions as they relate to an individual, an organization, or a whole country’ (p. 542). In order words, development outcomes can be seen to be achieved through better socio-economic conditions which lead to better health outcomes.

Flipping the script on healthcare: ICTs for health equity

The most important lesson learned from the COVID 19 pandemic is that the health of the poorest affects the rest of the population. The health of a population is connected to its socio-economic status. Flipping the script on healthcare means addressing the socio-economic disparities that lead to health inequities. There appears to be an upward cycle in which high SES leads to better health and wellbeing which leads to elevated education, income and combined wealth of a community. The opposite occurs in communities with low SES whereby low employment, income, and education make it difficult to stay healthy. A downward spiral takes place in low-income communities that cannot afford the care they need. The ability to earn a living is compromised by declining health and ability to access the resources needed to stay healthy. SES disparities in communities facing downward spirals lead people to find other means of survival that can bring them in contact with police brutality.

The pandemic described above has disproportionately affects people in low income neighborhoods who do not have access to fresh food, water and housing – people with low socio-economic status (SES). At the same time, the largest number of confirmed cases are in the Americas (mostly in the United States and Brazil) with 3 million cases, and in Europe with 2.2 million cases (mostly in the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy) according to the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2020). The coronavirus pandemic has exposed some very serious problems in the healthcare systems globally. Italy, thanks to its publically funded universal health system, was able to shut the country down with strict stay at home orders for its population. Yet, its health system was not able to cope with the high death rates with many of its medical professionals infected and dead in the process. The United Kingdom now has the highest number of cases and deaths in Europe and a public health system struggling to cope. Western Pacific has 188,393 cases with New Zealand reporting none at this time (WHO, Citation2020). New Zealand successfully fought the pandemic through tracking, tracing and quarantine of their populations and is opening up its economy without serious risk of a second wave of infections.

Utilization of medical services and access to care explain only a relatively small part of the association between SES and health (Adler et al., Citation1994). Working environment and lifestyle factors such as smoking, drinking and exercise are important indicators. Low SES individuals more often perform risky, manual labor than high SES individuals and their health deteriorates faster as a consequence. Education appears to be a key dimension of SES in increasing wages and increases wages, thereby enabling purchases of health investment goods and services. (Marmot, Citation2007, Galama and van Kippersluis (Citation2018).

In addition to the SES indicators, ICTs play a role in enabling communities to grow their wealth. When thoughtfully implemented, information technologies can bridge the financial, social, and distance gaps between patients and health professionals in underrepresented populations (Deitenbeck et al., Citation2018; Negash et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, when the behaviors, perceptions, desires, and needs of underrepresented populations are considered, these information technology interventions prove to be sustainable (Deitenbeck et al., Citation2018; Negash et al., Citation2018). Recent studies have found a significant correlation between the social determinants of health and on health equity in relation to mHealth use at a global level (Qureshi et al., Citation2019; Qureshi & Xiong, Citation2019). At the aggregate global level, there is a strong positive correlation between mHealth, social inequalities in life expectancy, and Human Development education (Qureshi & Xiong, Citation2020). There is also a significant relationship between mHealth, social inequalities in the provision of healthcare, and human development outcomes.

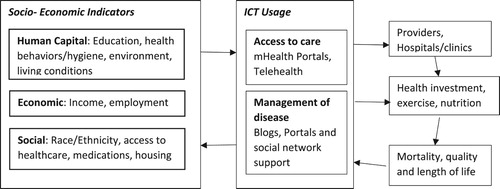

The following diagram illustrates this cyclical relationship between SES and health.

As illustrated in , addressing disparities in SES indicators can potentially spur a positive cycle which leads to better health of a population. Africa offers an instructive case of increased SES. Africa has the lowest rate of infection with only 121,104 confirmed cases (WHO, Citation2020). Having learned from the Ebola outbreak (2014–2016), most African countries implemented lockdowns far earlier than the United States and Western Europe. Despite the undercounting of official data in African countries, the spread in Africa is contained by its socio-economic context such as limited travel due to sparse road networks and containment measures easier to implement in isolated villages. Early containment has been key to the low infection rates. By the end of April, at least 42 African countries had undertaken early containment; 38 of these were in place for at least 21 days (Economist, Citation2020).

The innovative ways in which mobile apps are being developed and in Africa is also playing a part in combatting the spread of COVID 19. The SES challenges in Africa are unique and there is fear that the respiratory disease could have a catastrophic impact on a continent with shaky healthcare systems and where soap and clean water for hand washing are out of reach for many. Local expertise is being used to develop applications to address these challenges. In Nigeria, a COVID-19 Triage Tool, is a free online tool to help users self-assess their coronavirus risk category based on their symptoms and their exposure history. Depending on their answers, users are offered remote medical advice or redirecting to a nearby healthcare facility. The South African government is using the popular WhatsApp chat service to run an interactive chatbot which can answer common queries about COVID-19 myths, symptoms, and treatment. It has reached over 3.5 million users in five different languages since it was launched in March 2020 and is being rolled out globally. Women market sellers in Uganda are using the Market Garden app to help people avoid spreading it. This app lets vendors safely sell and deliver fruits and vegetables to customers as restrictions to promote social distancing come into play. It reduces bustling crowds in market areas by allowing women to sell their goods from their homes through the app, and then motorcycle taxis deliver the goods to customers. The women are paid through the platform to limit the risk of the virus transmitting through the exchange of cash. In Kenya, the mobile money platform M-Pesa, which is run by telecoms giant Safaricom, has more than 20 million active users in a population of 47 million. People are being encouraged to use M-Pesa to avoid spreading the virus when paying for goods (Harrisberg, Citation2020).

Galama and van Kippersluis (Citation2018) suggest that recent significant contributions to the understanding of socio-economic disparities in health have concentrated on the identification of causal effects, but have stopped short of uncovering the underlying mechanisms that produce the causal relationships. They offer insight into these underlying mechanisms by taking a human capital perspective. Education, a key component of human capital, is found to have a causal protective effect on mortality as education potentially increases the efficiency of medical and preventive care usage. The higher educated are also better able at managing their diseases, and benefit more from new knowledge and new technology. It is the combination of factors that enable an upward cycle of health and socio-economic status to be achieved. They offer a human capital model in which they show that a higher marginal value of health, in turn, increases the marginal benefits of healthy consumption, and the marginal costs of unhealthy working (and living) environments, and unhealthy consumption. This leads to healthier behavior and gradually to greater health advantage with age. The more rapidly worsening health of low SES individuals may lead to early withdrawal from the labour force and associated lost earnings, further widening the gradient in early and mid-age.

Addressing the socio-economic disparities is not an easy task. The socio-economic disparities, particularly in race, highlighted by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people in marginalized communities are uncovering the socio-economic disparities in their communities. The causes of segregation and institutionalized racism need to be unraveled and opportunities created through access to education and economic opportunity. ICTs can be part of the solution when implemented appropriately for addressing local conditions. The opportunity for users to remotely monitor their own health is particularly useful for low income and rural populations who may be unable to visit a healthcare profession due to monetary or travel limitations as well as those who may have hesitations in seeking medical services (Deitenbeck et al., Citation2018). To be sustainable, developers of mHealth tools must observe how their tool is being used, monitor user behavior, and collect feedback from its users to ensure quality and relevancy (Negash et al., Citation2018).

While cellphone usage is growing rapidly in Africa, not everyone can afford cellphone connectivity. Parts of the Americas and Eastern Europe have little connectivity especially in rural areas. Addressing the discrepancies in connectivity is key to enabling people in marginalized communities to partake in economic opportunity. The pandemic has changed the way people work. Traveling to work is no longer necessary for some people and working from home is becoming the norm in our society. An issue affecting socio-economic disparities has been the inability of people in poverty to get to jobs because of limited transportation opportunities. Now, because of the pandemic, they need internet connectivity to be able to carry out jobs that have moved online. The research published in this issue offers ways of addressing the SES inequities through appropriate ICT implementations to achieve better health outcomes. The following section offers a summary of the papers in this issue.

Papers in this issue

The papers in this issue reflect ways in which the socio-economic indicators can be increased to support better health outcomes for people in low SES communities. They uncover the key issues facing communities offering healthcare service to their constituents and move the field forward by showing the ways in which ICTs may support a positive cycle of development and health outcomes.

The first paper in this issue is authored by Yan Li, Manoj Thomas, Debra Stoner and Sarbartha Rana. It is titled ‘Citizen-Centric Capacity Development for ICT4D: The Case of Continuing Medical Education on a Stick’. The authors contend that the imbalance of the health workforce between rural and urban has the most severe impact in low-income countries (LICs). Lack of professional development opportunities, such as Continuing Medical Education (CME), is one of the key elements in this disparity. Their research first presents a revised Citizen-centric Capacity Development (CCD) framework that focuses on goal driven ICT solution design and impact assessment. It then investigates how the CCD framework guides the design, development, and assessment of CMES (CME on a Stick), a low-cost, integrative platform for the delivery of CME content to rural health workers in LICs. The success of the CMES project highlights the significance of the CCD framework in creating design artifacts that are contextually relevant, broadly scalable, and technologically sustainable. The research contributes not only to the theoretical knowledge of linking ICT interventions and development goals, but also the practical knowledge of ICT-based human capacity building in LICs.

Isaac Holeman and Dianna Kane co-author the second paper in this issue titled ‘Human-Centered Design for Global Health Equity’ They state that as digital technologies play a growing role in healthcare, human-centered design is gaining traction in global health. Amid concern that this trend offers little more than buzzwords, their paper clarifies how human-centered design matters for global health equity. First, they contextualize how the design discipline differs from conventional approaches to research and innovation in global health, by emphasizing craft skills and iterative methods that reframe the relationship between design and implementation. Second, while there is no definitive agreement about what the ‘human’ part means, it often implies stakeholder participation, augmenting human skills, and attention to human values. Finally, they consider the practical relevance of human-centered design by reflecting on their experiences accompanying health workers through over seventy digital health initiatives. In light of this material, we describe human-centered design as a flexible yet disciplined approach to innovation that prioritizes people's needs and concrete experiences in the design of complex systems.

The third paper in this issue is co-authored by Rezwanul Rana, Khorshed Alam and Jeff Gow. It is titled: ‘Health outcome and expenditure in low-income countries: Does increasing diffusion of information and communication technology matter?’ Their paper examines whether increasing diffusion of ICTs has the potential to improve healthcare use and access to better health outcome and higher spending on health in 38 low-income countries with a panel data for the period of 1995 to 2015. The panel corrected standard error, and fixed effect Driscoll-Kraay methods were used to account for unobserved heterogeneity and cross-section dependence in the panel data. A healthoutcome index was developed using partial least square based on a structural equation model with SmartPLS (version 2) software package. The estimated results indicate that increasing diffusion of ICT impacts both the health outcome and expenditure, positively and significantly. The association is stronger when the diffusion of ICT takes place in rural areas. In conclusion, ICT is not only a means for providing better healthcare services but also an essential instrument for popularizing healthcare access and use for all.

Frank Nyame-Asiamah authors the fourth paper titled ‘Improving the ‘manager-clinician’ collaboration for effective healthcare ICT and telemedicine adoption processes – A cohered emergent perspective’. The author states that existing research shows that the adoption of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for healthcare development in developing countries is largely dominated by donor and international agencies, but the actual organizational-level decisions are often driven by corporate healthcare managers. The consequences of the strategic-driven healthcare ICT adoption practices are that they fail to match clinician users’ requirements and cause them to disuse ICTs for clinical practices and healthcare development. Prior attempts to bring local and globally distributed actors together to implement ICTs innovatively for healthcare development have emphasized less on synthesizing the diverse information system approaches that inform our understanding of how to narrow the ‘manager-clinician’ tensions in ICT adoption for development in emergent situations. To fill this gap, this article explains the process of shifting healthcare ICT adoption from top-down planning to collective user involvement to enhance clinicians’ acceptance of ICTs for clinical practices and development in a Ghanaian teaching hospital, using the cohered emergent transformation model. Action research was used to engage the hospital’s corporate managers, clinician managers and clinicians, and elicit their views and experiences of the hospital’s ICT adoption for healthcare delivery improvement. Together with observations and document analysis, the data were analyzed to understand the hospital’s information and communication technologies for development (ICT4D) adoption issues and identify ways of managing them. The outcomes provide alternative theoretical and practical ways of adopting healthcare technology systems that shift the excessive use of managers’ powers in ICT adoption towards clinicians’ involvement, to enable technology acceptance for clinical practices and healthcare development.

Judy Van Biljon is the author of the fifth paper in this issue titled ‘Knowledge Mobilisation of Human-Computer Interaction for Development Research: Core Issues and Domain Questions.’ She states that Human-computer interaction for development (HCI4D) operates at the intersection of Human-computer interaction (HCI) and information and communication technology for development (ICT4D). The interdisciplinary nature complicates knowledge transfer and articulation between the disciplines contributing to the HCI4D domain. This paper proposes a conceptual framework to highlight the core issues and domain questions in HCI4D towards supporting knowledge mobilization between researchers in HCI4D and the related fields. The author presents an overview of the HCI4D literature (2007–2017) which investigated the domain questions, including the core issues, focus areas, the phenomena of interest, target users and the research methods. The findings are presented as a conceptual framework which comprises the core issues and salient elements for each of the domain questions. This framework is evaluated and checked against 2017–2019 literature to propose a final HCI4D knowledge mobilization framework (HCI4D_KMF). The contribution of this research lies in knowledge transfer and articulation towards enriching discussions on HCI4D research

The sixth paper in this issue in titled ‘An 89% solution adoption rate at a two-year follow-up: evaluating the effectiveness of an animated agricultural video approach.’ It is co-authored by Julia Bello-Bravo, Eric Abbott, Sostino Mocumbe, Ricardo Maria, Robert Mazur and Barry Pittendrigh. The authors contend that securing the adoption of scalable agro-educational information and communication technology (ICT) solutions by farmers remains one of the international development community’s most elusive goals. This is in part due to two key gaps in the data: (1) limited comparisons of competing knowledge-delivery methods, and (2) few to no follow-ups on long-term knowledge retention and solution adoption. Addressing both of these gaps, their study measures farmer knowledge retention and solution adoption two years after being trained on an improved postharvest bean storage method in northern Mozambique. The results found animated-video knowledge delivery at least as effective as a traditional extension approach for knowledge retention (97.9%) and solution adoption (89%). As animated video can more cost-effectively reach the widest, geographically isolated populations, it readily complements extension services and international development community efforts to secure knowledge transfer and recipient buy-in for innovations. Implications and future research for adult learning are also discussed.

‘ICT for agriculture extension: actor network theory for understanding the establishment of agricultural knowledge centers in South Wollo, Ethiopia’ is the seventh paper in this issue and co-authored by Fanos Mekonnen Birke and Andrea Knierim. Their study aims at understanding how various actors interact in establishing and managing an Information Communication Technology (ICT) based initiative called Agricultural Knowledge Centers (AKCs) in Ethiopia. It also explores the diverging and shared interests of the actors in the benefits of the AKCs. The authors gathered and analyzed data from in-depth interviews in five extension offices in the South Wollo zone, Ethiopia, and supplemented it with project documents and observations. They used Actor Network Theory (ANT), particularly the four moments of translation, to analyze the results. Their findings show how people and technology came together to establish the AKCs and to provide extension experts access to digital knowledge. Factors that contributed to creating and stabilizing the AKC actor network included the presence of an actor to facilitate the process, alignment of interests among actors in the network, building the capacities and motivation of the various actors to execute their roles, and availability of computers with strong internet connections. These findings contribute to practical and policy debates on harnessing ICT’s potential for facilitating socioeconomic development in the Global South; and to the theoretical discussions on the merits of the ANT perspective in analyzing the adoption of technological innovations.

Amrita Chatterjee authors the eight paper in this issue titled ‘Financial Inclusion, Information and Communication Technology Diffusion and Economic Growth: A Panel Data Analysis.’ She states that earlier studies accept that both Financial Inclusion (FI) and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) individually play positive role in economic growth. Moreover, ICT applications like mobile phone and internet penetration are being increasingly utilized in banking sector. The present study has shown that ICT development can be an important determinant of Financial Inclusion by using a fixed-effect panel data model of 41 countries. The paper further contributes by highlighting the role of FI, powered by a better ICT penetration, in fostering the growth of the countries in a Dynamic Panel Data Model. The results suggest that both FI individually and once coupled with mobile and internet can improve the per capita growth. However, in developing countries, the role of ICT indicators in fostering financial inclusion and therefore growth is not very promising. From the policy perspective, it suggests that more investment in educating people about the usage of ICT in formal banking sector is required.

Conclusion

Amidst a global pandemic, outrage and anger over the death of a Black man at the hands of a White police officer spread globally. The protests exposed generations of institutional racism and socio-economic inequities in societies globally. This editorial explores the socio-economic inequities that have left those in racially segregated marginalized communities most at risk from COVID 19. It offers a cyclical view of the relationship between socio-economic inequities and health outcomes, suggesting that once these inequities are addressed, then health outcomes can improve. There is an important role to be played by ICTs in enabling a positive cycle to take place. The papers in this issue reflect the ways in which the socio-economic indicators can be increased to support better health outcomes for people in low SES communities. They uncover the key issues facing communities offering healthcare services to their constituents. They move the field forward by showing the ways in which ICTs may support a positive cycle of development and health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Given the speed and severity at which events have unraveled while writing this piece, reviewer feedback has been essential in bringing out its key contributions. I am very grateful to Peter Wolcott, Doug Vogel, Timi Barone and Chris Mangen for their detailed, insightful and very valuable feedback on earlier versions. It is because of editors and reviewers like them, that this Journal continues to publish quality work.

References

- Adelman, L. (2008). Unnatural causes: In sickness and in wealth. Kanopy, commentary by Nicholas Christakis and Sir Michael Marmot. www.kanopy.com/video/sickness-and-wealth.

- Adler, N. E., Boyce, T., Chesney, M. A., Cohen, S., Folkman, S., Kahn, R. L., & Syme, S. L. (1994). Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American psychologist, 49(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/1010.1037/0003-066X.49.1.15

- Adler, N. E., & Newman, K. (2002). Socioeconomic disparities in health: Pathways and policies inequality in education, income, and occupation exacerbates he gaps between the health ‘Haves’ and ‘Have-nots’. Health Aff (Millwood), 21(2). https://doi.org/1010.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60

- Beer, T. (2020). Minneapolis City Council Unanimously votes to replace police with community-led model forbes. Retrieved June 12, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/tommybeer/2020/06/12/minneapolis-city-council-unanimously-votes-to-replace-police-with-community-led-model/#5a41098271a5

- Blumenthal, S. J., & Kagen, J. (2002). The effects of socioeconomic status on health in rural and urban America. Jama, 287(1), 109. https://doi.org/1010.1001/jama.287.1.109-JMS0102-3-1

- Braveman, P., & Gruskin, S. (2003). Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 57, 254–258. Retrieved from https://jech.bmj.com/content/57/4/254 doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.254

- Braveman, P. A., Kumanyika, S., Fielding, J., LaVeist, T., Borrell, L. N., Manderscheid, R., & Troutman, A. (2011). Health disparities and health equity: The issue is justice. American Journal of Public Health, 101(S1), 149–155. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062

- Castañeda, H., Holmes, S. M., Madrigal, D. S., Young, M. E., Beyeler, N., & Quesada, J. (2015). Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36(1), 375–392. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419

- CDC. (2020). CDC COVID data tracker centers for disease control. Retrieved June 6, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/index.html

- Deitenbeck, B., Qureshi, S., & Xiong, J. (2018). The Role of mHealth for equitable access to healthcare for rural residents. Association for Information Systems. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2018/Health/Presentations/12/

- Department of Labor. (2020). Unemployment rate by sex, race and Hispanic ethnicity. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/data/latest-annual-data/employment-rates

- Desilver, D., Lipka, M., & Fahmy, D. (2020). 10 things we know about race and policing in the U.S. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 30, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/03/10-things-we-know-about-race-and-policing-in-the-u-s/

- Duncan, G. J., Daly, M. C., McDonough, P., & Williams, D. R. (2002). Optimal indicators of socioeconomic status for health research. American journal of public health, 92(7), 1151–1157. https://doi.org/1010.2105/AJPH.92.7.1151

- Dunlop, S., Coyte, P. C., & Mcisaac, W. (2000). Socio-economic status and the utilisation of physicians' services: Results from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. Social Science & Medicine, 51(1), 123–133 doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00424-4

- Economist. (2020). Why Covid-19 seems to spread more slowly in Africa. Retrieved May 16, 2020, from https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2020/05/16/why-covid-19-seems-to-spread-more-slowly-in-africa

- Galama, T. J., & van Kippersluis, H. (2018). A theory of socio-economic disparities in health over the life cycle. The Economic Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12577

- Gramlich, J. (2019). 19 striking findings from 2019 Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 13, 2019, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/12/13/19-striking-findings-from-2019/

- Hafner-Eaton, C. (1993). Physician utilization disparities between the uninsured and insured: Comparisons of the chronically ill, acutely ill, and well nonelderly populations. JAMA, 269(6), 787–792. https://doi.org/1010.1001/jama.1993.03500060087037.

- Harrisberg, K. (2020). Here's how Africans are using tech to combat the coronavirus pandemic. World Economic Forum. Retrieved April 5, 2020, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/africa-technology-coronavirus-covid19-innovation-mobile-tech-pandemic

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. (2020). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/us-state-data-availability

- Karlsen, S., & Nazroo, J. Y. (2006). Measuring and analyzing ‘race,’ racism, and racial discrimination. In J. M. Oakes, & J. S. Kaufman (Eds.), Methods in social epidemiology (pp. 86–111). Jossey Bass

- Krieger, N. (2000). Discrimination and health. In L. F. Berkman & I. Kawachi (Eds.), Social epidemiology (pp. 36–75). Oxford University Press

- Lahelma, E., Martikainen, P., Laaksonen, M., & Aittomäki, A. (2004). Pathways between socioeconomic determinants of health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 58(4), 327–332. http://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.011148

- Lantz, P. M., & Pritchard, A. (2010). Socioeconomic indicators that matter for population health. Preventing Chronic Disease, 7(4), 1–7. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jul/09_0246.htm.

- Levin, S. (2020). Movement to defund police gains ‘unprecedented’ support across US. The Guardian. Retrieved June 4, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jun/04/defund-the-police-us-george-floyd-budgets

- Marmot, M. (2007). Achieving health equity: From root causes to fair outcomes. The Lancet, 370(9593), 1153–1163. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3

- Marmot, M. G. (2003). Understanding social inequalities in health. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3), S9–S23. https://doi.org/1010.1353/pbm.2003.0056

- Monheit, A. C., & Vistness, J. P. (2000). Race/Ethnicity and Health Insurance Status: 1987 and 1996. Medical Care Research and Review, 57(1), 11–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558700057001S02.

- Negash, S., Musa, P., Vogel, D., & Sahay, S. (2018). Healthcare information technology for development: Improvements in people’s lives through innovations in the uses of technologies. Information Technology for Development, 24(2), 189–197. https://doi.org/1010.1080/02681102.2018.1422477.

- Noppert, G. A. (2020). COVID-19 is hitting black and poor communities the hardest the viral pandemic is underscoring fault lines in access to care for those on margins. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://daily.jstor.org/covid-10-hitting-black-poor-communities-hardest/

- Nuzzo, J. B., Mullen, L., Snyder, M., Cicero, A., & Inlesby, T. V. (2019). Preparedness for a high-impact respiratory pathogen pandemic, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Retrieved September 2019, from http://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/our-work/pubs_archive/pubs-pdfs/2019/190918-GMPBreport-respiratorypathogen.pdf

- Pampel, F. C., Krueger, P. M., & Denney, J. T. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annual Review of Sociology, 36(1), 349–370. https://doi.org/1010.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529

- Pamuk, E., Makuc, D., Heck, K., Reuben, C., & Lochner, K. (1998). Socioeconomic status and health chartbook. health, United States. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus98cht.pdf

- Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., Diez-Roux, A., Kawachi, I., & Levin, B. (2004). "Fundamental causes” of social inequalities in mortality: A test of the theory. Journal of health and social behavior, 45(3), 265–285 doi: 10.1177/002214650404500303

- Qasim, S. (2020). How racism spread around the world alongside COVID-19. World Economic Forum. 5 June 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/just-like-covid-19-racism-is-spreading-around-the-world/

- Qureshi, S., & Xiong, J. (2019, August 15–17). Social determinants of health equity: Does mHealth matter for human development? 25th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2019, Cancún, Mexico. Association for Information Systems.

- Qureshi, S., & Xiong, J. (2020). Equitable healthcare provision: uncovering the impact of the mobility effect on human development. Information Systems Management, https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2020.1732531

- Qureshi, S., Xiong, J., & Deitenbeck, B. (2019, January 8–11). The effect of mobile health and social inequalities on human development and health outcomes: mHealth for health equity. 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS 2019, Grand Wailea, Maui, Hawaii, USA.

- Reuters. (2020). George Floyd: America's racial inequality in numbers World Economic Forum. Retrieved June 2, 2020, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/george-floyd-america-racial-inequality/

- Roztocki, N., & Weistroffer, H. R. (2016). Conceptualizing and researching the adoption of ICT and the impact on socioeconomic development. Information Technology for Development, 22(4), 541–549. http://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2016.1196097

- Science News. (2020). The United States leads in coronavirus cases, but not pandemic response. Retrieved from https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/united-states-leads-coronavirus-cases-not-pandemic-response#

- Sen, A. (2002). Why health equity? Health Economics, 11(8), 659–666. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/hec.762

- Shi, L., & Starfield, B. (2000). Primary care, income inequality, and self-rated health in the United States: A mixed-level analysis. International Journal of Health Services, 30(3), 541–555 doi: 10.2190/N4M8-303M-72UA-P1K1

- Singh-Manoux, A., Adler, N. E., & Marmot, M. G. (2003). Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science & Medicine, 56(6), 1321–1333. https://doi.org/1010.1016/S0277-9536(02)00131-4

- Stansfeld, S. A., Head, J., & Marmot, M. G. (1998). Explaining social class differences in depression and well-being. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 33(3), 136–139. https://doi.org/1010.1007/s001270050034

- Stoddard, M. (2020). Hispanics and Asian Americans hit hardest by coronavirus in Nebraska, new data show. World-Herald Bureau. Retrieved May 29, 2020, from https://www.omaha.com/livewellnebraska/hispanics-and-asian-americans-hit-hardest-by-coronavirus-in-nebraska-new-data-show/article_d8dad8f2-237c-526d-939b-ded73d8ddc0c.html

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. WHO (COVID-19) Homepage. Retrieved June 5, 2020, from https://covid19.who.int/